Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 64

June 1, 2015

Murderers and Fortune Cookies

As I have no sense of direction, which appears to be contagious, traveling anywhere with me is tricky. Thinking it would be fun, Satchel and I took a day trip to San Francisco’s Chinatown, Ghirardelli Square, and Pier 39, and made it there and back, though barely.

Satchel, Aug 5, 2013, Larkspur Ferry

Going, we missed the Larkspur Ferry by ten minutes, so waited for the next one. Finally boarding, we sat on the windy upper outside deck so we could see the view. San Quentin and Alcatraz are fascinating to a ten-year-old boy who wants to know if you know anyone who got murdered and how it happened, and whether you actually know any real murderers, and who had they killed. Luckily my Italian brother-in-law’s brother was at one time in San Quentin for murder. We also have an ancestor, Valentine Hoy, who in 1898 was killed by Harry Tracy, the most infamous criminal of that day. My grandson was thrilled to hear the stories.

We made it to the City and were dropped of at the Ferry building. So far, so good. Then we found our way to Chinatown after asking a number of random strangers where to find the cable car. We grabbed an outside seat and hung on tight, hugging our legs close to prevent amputation from the passing cars, and actually got off on the right corner. I knew it because all the signs were in Chinese and the cable car driver winked at me, promising he’d tell us where to disembark.

we found our way to Chinatown after asking a number of random strangers where to find the cable car. We grabbed an outside seat and hung on tight, hugging our legs close to prevent amputation from the passing cars, and actually got off on the right corner. I knew it because all the signs were in Chinese and the cable car driver winked at me, promising he’d tell us where to disembark.

The two of us wandered around Chinatown poking our heads in all the stores, ate dim sum at the Great Eastern Restaurant on Jackson, then bought a sack of dried mushrooms, some wonderfully weird fruit, and a bag of fortune cookies. Gary Ruiz suggested that while we were there, I see his Chinese doctor about my not-quite-healed kidney stone pain. We found the pharmacy as it was just up the street. In the back room, the doctor tested my pulse, looked at my tongue, and wrote a prescription in Chinese characters for five bags of tea to the tune of $37. It was only $12 for the tongue and pulse advice; the translator told me the doctor said my back still hurts because there’s sand in there from the stone,  and the tea would cure me. Our arms loaded with weird fruit, dried mushrooms, fortune cookies and five bags of tea–we’re talking five lunch bags, not tea bags–we head to Ghirardelli Square where the day starts to head downhill. We caught the bus going the opposite direction. We got off twenty minutes later when we finally figured it out, then waited a half hour for the right bus to come along. As we boarded, we realized it was the same damn bus we’d gotten off a half hour earlier, with the same driver that I now wanted to seriously whack upside the head. We asked him the first time around if his bus would take us to the Square and he said yes, but failed to tell us not until he’d completed the route in the opposite direction. I put Satchel in charge of making the bus driver tell us exactly when and where to disembark. The driver does, but by this time I don’t trust him. He knew that’s where we wanted to go in the first place and didn’t bother to point out to us that we couldn’t get there from here.

and the tea would cure me. Our arms loaded with weird fruit, dried mushrooms, fortune cookies and five bags of tea–we’re talking five lunch bags, not tea bags–we head to Ghirardelli Square where the day starts to head downhill. We caught the bus going the opposite direction. We got off twenty minutes later when we finally figured it out, then waited a half hour for the right bus to come along. As we boarded, we realized it was the same damn bus we’d gotten off a half hour earlier, with the same driver that I now wanted to seriously whack upside the head. We asked him the first time around if his bus would take us to the Square and he said yes, but failed to tell us not until he’d completed the route in the opposite direction. I put Satchel in charge of making the bus driver tell us exactly when and where to disembark. The driver does, but by this time I don’t trust him. He knew that’s where we wanted to go in the first place and didn’t bother to point out to us that we couldn’t get there from here.

He tells us where to get off, which is so what I wanted to do to him; we thought we were lost again as we’re looking for a large brick building that is the entrance to Ghirardelli Square, which we happened to be standing right in front of. By this time, we are fading, so to sustain us, we head for the Western cures of a lemon sorbet and a chocolate sundae. As I wasn’t about to get on another wrong bus, we walked to Pier 39 where we finally found the magic store, then we walked back to the Ferry Building, hauling our substantial evidence of a Chinatown visit. We made the ferry by the hair of our chinny-chin chins. We found places to sit on the lower inside deck: not only was it packed, it was now freezing out, so I sat with my head down and eyes closed for the half-hour ride. (I get seasick.) Then we walked the mile to the car. The lot was full in the morning when we got there, which is why we missed the ferry in the first place. In case you’re not clear, Satchel and I are not what you’d refer to as “walkers.”

Spent, we made it home to Sonoma at 7:30 to have dinner at Brooke’s sister’s house, which of course I couldn’t find. I called my son, Matt, confirmed we were in front of the right house, laid my phone on the trunk of a car in the driveway to put on my coat, then joined the party. Matt left the party at 9:00, got home, and called Brooke to tell her my phone is stuck on the trunk of his car. I got this this sticky rectangle thing at a real estate conference; you peel off one side and attach to the back of your phone, and the other side is also sticky so when you leave it on the trunk of someone’s car like some special kind of stupid, it holds it there and doesn’t fall off and get run over by fifty cars while traveling a couple miles away at 40 mph.

By ten I dropped into my bed, happy. I got my phone back. The dim sum was everything we hoped it would be. Chinatown was exotic, the fortune cookie factory was fascinating though not terribly sanitary looking, and Satchel was fine that we never made it to the arcade. I’m not sure about the Chinese doctor; if in five days I’m still alive and the pain in my back is gone, I’ll be overjoyed.

Temple and Satchel, Aug 2, 2013

It will be a while before we take another trip. I have to tell you, five-year-old girls and the local park are much easier on me; I can find my way around the park, and it’s not that far.

May 25, 2015

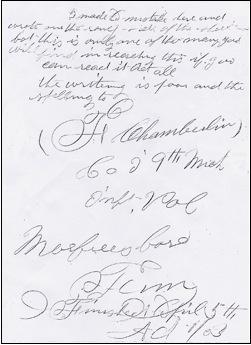

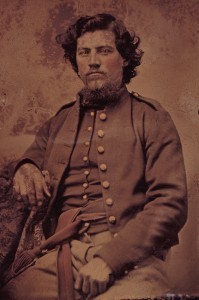

Civil War Journal of Finley Chamberlin

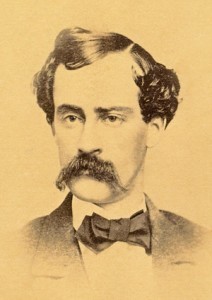

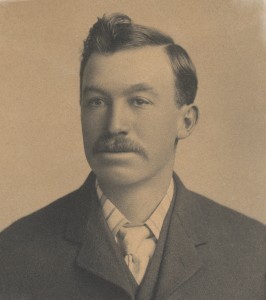

Finley Chamberlin, 1872

Finley McLaren Chamberlin was my great-grandfather, the father of Nellie (Chamberlin) Chatfield, my grandmother who was my mother’s mother.

Finley Chamberlin’s Civil War Letter or Journal is composed in several “chapters,” begun on February 27, 1863, while in service at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. It provides a picturesque account of his military experiences as a Private, beginning with his enlistment for three years on August 15, 1861, at Brighton in Livingston County, Michigan (his relatives lived nearby), rather than in Detroit, as he implied in his letter. It covered the period of time until he finished his narrative letter, on April 5, 1863, while still in service in Tennessee. Finley re-enlisted later in 1863, serving until the close of the war in 1865, when he was discharged in Jackson, Michigan, with the rank of Sergeant.

Feb 27, 1863: Letter from Finley Chamberlin (age 17 years, 5 months) to his family living in Middlebury, Wyoming Co., New York (transcription of 20 handwritten pages):

Headquarters 9th Michigan I Vol.

Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Feb. 27th, A.D. 1863

Dear Father, Mother and Sister, one and all, I address you all who are connected with the circle at home. I seat my selfe this beautiful afternoon to draw an outline of what I have seen and felt since I have been connected with this Regt., here it begins:

The 9th Regt. from Michigan was organised the 15th of August 1861 in the neat City of Detroit bordering on the Detroit River. A beautiful stream of a half mile in width, on the other side is the small town Winsor on the canadian shore, here the Regt. was organised under the command of W.W. Duffield. A noble hearted man, tall and strait, with strait black hair, rather course black beard, black eyes and rather light complection. Here in fort wane some half mile below the city we took up our quarters, and stayed on till the 25th of October, during our stay here the time passed off pleasantly though all looked eagerly forward to the time when we were to depart, the time came at last. It was a cool, beautiful morning the 25th of October.

Our Regt. was drawn to wait the arrival of the Queen of the west that was to take us to the city, here we waited some two hours, the boat came at last and we embarked and soon we were landed in the city but not to stay. We marched to the depot and were soon comfortably seated, such of us as chose to sit. A half hour perhapse elapsed when two beautiful engines were hitched to the train, the Washington and Greyhound. They were fleet runners, and were beautiful with evergreens on the banners of our union but a few moments ere long such as had friends waved them a silent adieu, and we were soon on our way to the far off south, to battle for our country, our freedom and our rights. Eleven oclock found us out of sight of the city and many hearts sent up the three loud long cheers for our country and our success. We had made the day a beautiful one and all passed merrily on. We were met on every hand with cheers and joy, and from almost every house top floated the old flag of our union free in the breeze.

Two oclock found us entering the city of Jackson, this is a small neat city and if I recollect to write, about 60 miles from Detroit, this city can bee seen for some distance with its bright steeples glittering in the sun, this is the city of industry and enterprise, here is the prison in which are confined men of low characters of every kind from low to meane, from meane to meanest, in this are confined meanest of men, the most corrupt of our nation – but I must proseed, we enter the city and were met here with cheers from old and young of both sects. The young ladies of the city presented us with boxes of cake and fruit of all kinds, with baskets of every hue. Here we got some coffee and felt ourselves refreshed by it. The most of us left the car here and shook hands with every body back in the city or at least everyone in the crowd then we jumped aboard of the cars, gave three cheers for the Jackson girls and bade them adieu the compliment was returned of course. But in the meantime of shaking hands with a young lady—she gave me her pocket handkerchief, on we go, all was joy and mirth when the shades of night began slowly to close around. All became more calm, the soldiers were left to reflection on the homes they had left for 3 years, perhaps forever, and some died, yes many left their wives and children brothers and sisters to meet no more for ever on earth. At about 8 oclock we entered the city of michigan, this city is just across the line in indianna, but when we entered this city night was farely set in and as I could see nothing I shal not attempt to describe the place all I will say is here we changed engines and sped on, the next thing that we noticed was the large white sand hills which often cover the track this we saw only by the light of the moon and have but a feint idea of them not enough to describe any thing, we rested but little that night and the next morning found us far from our home and the friends we loved.

About ten oclock on the 26th we reached the capitol of indianna known as the city of Indianapolis. This city is situated on a bluff though not high, this city has not the appearance of neatness that the one we left far behind, it has a smoky, dingy appearance, its streets, or those through which I passed, presented a dirty, filthy appearance. The people of the city did not seem to have the keen enterprise and industry that is to bee seen in the wolverine, here in this city we partook of some food though not as palitable as that we received in Jackson it consisted of hard bread and coffee alone, the hard bread was the first I had ever tasted and I asshure you it was not very sweet and it was very old and as I have found out since by experience a very poor article. We left this place making only a short stay inroute for Jeffersonville, ind. Nothing of any note occurred on the road, we arrived there the night of the 27th, here we partook of another soldiers meal and slept all night in the cars, the next morning we took some more hard bread and coffee, and a piece of bacon that my dog would not eat in any common time, then breakfast over we were ordered to sling our knapsacks for a march we were drawn up in line and took up our line of march for the four mild springs so called by as these springs were near the bank of the Ohio opposite Louisville, Ky., here we remained the 28 which was Sunday, here we got our arms, which were of an inferior kind–known as the belgium musket. When I woke the morning of the 29th sun was shining brightly in the east. I hastily arose, folded my blankets placed them in their straps for I learned we had orders to the river to Ky. I then hastened to my breakfast which was the same I have described to you before. While drinking a cup of coffee I learned I had been fortunate in getting a nights sleep for most of the men had been engaged all night in digging a road to the river. After breakfast which was soon over, I went to the river where lay two large stern wheelers waiting for us, in the course of two hours everything was on board and the whistle blew and off we went and bade a farewell to ind.

We crossed the River to Louisville, Ky., this city I can say but little of it for we did not get off the boat. It has a beautiful appearance from the other side of the river, we touched at the lower end of the city as nearly there, for this reason I saw but a few back streets, the levy had as clean an appearance as any of our city docks have, in consequence of high water they have no docks, the levy was back for a considerable distance. When we came along side the levy here we saw females of every color that human beings possess, each had something to sell, apples, pies, cakes, peaches, pares, plums, grapes, figs, oranges, lemons, and everything one could wish to eat. The females began to throw apples on board for us, the officers soon stopped it and forbid any soldier eating any thing they threw on board for fear of being poisoned as they said it had been done before, and as we were young soldiers and green ones so we thought it must be so for the officers said it was and we ate no more of the proffered apples.

CHAPTER II

Our first camp in the enemys country. Sickness, Death and hardship, after leaving Louisville we rode the river some 25 miles, when our little flet consisting of four boats turned and shaped their course up Salt river opposite to west point, a small town on the junction of the Salt and Ohio, here we stayed for two weeks. Here the Regt. lay on the wet ground, many of the men caught cold and were taken sick and many died. I was among the sick. I slipped into the river while crossing it on a log for the purpose of getting some straw for a bed, caught cold, and slept with my wet clothes on and in three days I was so bad I was unable to get out of the tent without help. I was then taken to the hospitle acros the river, here I spent two long weary month with the fever, here I suffered much, when I recovered I found a fort on moldrough hill, the same that you will see in the picture of west point, this fort is on the hill, some three quarters of a mile from the town. The fort is about 350’ above the Ohio. The Regt. suffered much from sickness. We had at one time 100 men on the sick roll. We lost 50 men here in the four months, while I was in the hospitle I have seen five dead bodys in the hospitle at one time, they were buried in various places but are all removed to the top of the hill about 60 rds. from the fort and are buried together in one place and have a large plank with all their names on it and it is the design of the state to have a monument erected on the mound. Many of the men were made sick by these long and hard days work on the fort now called fort Blair. After I left the hospitle after two months, six of the cos went to Elisebath town some 25 miles, nothing more passed the winter of any importance so I will pass to the time of embarkation for Nashville, Tenn.

We left west point the 20 of March, ’62 on board the Jacob Strader, a large splendid steamer and after five days arrived in Nashville without anything worthy of mentioning, nothing was here transacted. We arrived in Murfreesboro, Tenn, the first day of April at 9 A.M. in this fine town in the middle part of Tenn., we spent the greater part of the summer, with having now and then to scout, and taking a few prisoners. Among them was John Morgan’s brothers, here we passed the summer very pleasantly till the 25th of May.

CHAPTER III

The March, The Accident. The Battle. The Return

The morning of the 25th of May 1862, we took the cars and went to Shelbyville, Tenn. Here we took up our line of march. Went 4 miles that night and camped on a small nole where we slept on the ground till morning, we marched hard and long for several days without anything transpiring worth mentioning, until one night just after we crossed battle creek and had got to camp, the driver of the ammunition wagon got into a dispute with one of general Scribners body guards which resulted in the body guard shooting Decker through the bowels. This was the drivers name, they were both intoxicated, they had some words before and they threatened each others lives. The generals bodyguard was a kentuckyan, and they wont stand much, I think he was never shot for it, Decker was a mean scamp, dishonest and quarrelsome, he lived till the next morning about ten oclock.

When we left this camp we began to climb the cumberland Mts. Here we had hard work, up, up over rough and rocky road, the worst I ever saw, we made but slow progress, here we suffered much of the time for water. Here we saw great natural currositys, caves and rocks, here I saw for the first time the cucumber tree, it has a large broad leaf and a cucumber when full grown about three or four inches in length. But I must hurry, we passed on through various seens, through muck, mud, and mire, went double quick for miles in the mud and rain, lay night after night upon the ground without a blanket and besides all this stole every horse and mule, hen, chicken, turkey, goose and duck that we could and took all the milk and butter, and honey and bread that we could find besides butchering all the hogs… now I will go on with my story, one fine morning we passed through secorchee valley where the advance of the troops had a fight with some of the rebel cavalry, here we found a very large nice spring, the water was as blue as the water of Erie, here we stayed some two hours and looked over the battlefield and went to graves of our men that were killed but we made the rebells skeedaddle, nothing more took place or the worth mentioning, we arrived near the bank of the Tenn. river on the night of the 4th of June, it was late and we did not get our blankets until two oclock in the morning, the next morning we were in line of battle and marched down to a clump of brush near the river, here we threw out one co. for skirmishes, the rest of the regts. were concealed but nothing very serious took place from the fire of the skirmishers, then the whole was ordered to forward march. We marched out some five or ten rods, threw down one fence and came out in plane sight of their battery and gave them the best we had in the wheel house and they did not return the fire, then we then marched back to camp, then we commensed our retreat and that night we slept on the top of what is called baldwins peak, here I had the best bed of any place on the march and as we did not start till late the next morning, we had a fine chance to over look the country, we were far, far above the river, we could see for miles, here we could see into Georgia and Allabama and could see Chattenoga and could see across the river a rebel camp, this was a lovely sight, the eye can see over as splendid a tract of land as you ever saw, but the assembly call has sounded and we must leave the spot, we resumed our march for two days and found ourselves at the foot of the first range of cumberland, but a long dreaded journey is before us yet, the third day we began again to climb the mountain again, long and wearysome was the journey, and it was long after noon before we reached the top but the top was finally reached, here we stopped and fed our horses and partook of some hard bread ourselves and then went on our way rejoicing, but our team was more fortunate than many for the rest in the train of many of them had nothing to eat or drink and before we encamped for the night general scribner lost from his train over thirty horses and mules for the want of food and drink and many of the men gave out. In the morning we resumed our march and on the fifth day we parted with our brigade and was left alone with our colonel and marched at our leisure but that was not very slow for all were anxious to bee at the old camp, that night we stayed in a beech grove 18 ms. from Murfreesboro and the old camp, we reached the old camp on the afternoon of the next day and loud and long was the cheers of the men when they once more came in sight of the old camp, we heard a few words from our colonel, he thanked us for our conduct on the march and gave us two days rest before we were to begin our dutys again, but they were at last begun and evrything went smoothly along.

CHAPTER IV.

Another march, another fight, Our Retreat & on & on.

On the last day of June, 1862, we left the pleasant camp at Murfreesboro, Tenn, for Tullahoma, Tenn., about forty miles farther south we went on board of the cars in the afternoon and reached Tullahoma about sundown and camped for the night without tents, slept well, but here we did not feel so safe as we did at the old camp, we had but a small body of men only four cos., the other 6 cos. remained at the old camp at Murfreesboro, we had to be up at 3 oclock every morning and stand in a line of battle untill daylight for bush whackers were reported to bee in the vicinity but in this way we kept well prepaired for them but we soon found out we were safer there than they were at the old camp. One morning as the sun rose clear and bright, 25 of our band were detailed to go to Manchester 12 ms., we went on board of the cars with harts and the expectation of a fine ride, it was a beautiful sabath day on the 13th of July, we started on our short and plasant jorney, the train ran verry slow for it was the first time the train had been over the road for months, the train stopped several times, once for wood and water and as the tender had to bee filled with pails from the spring we had nearly an hour to pick berrys and they were clost to the track, the finest and largest I ever saw, we picked as we wished and then we went on, when we started we heard cannon adding in the direction of Murfreesboro, but little did we think of hearing that all of the Regt. that was left at the old camp were taken prisoners, but it was indeed so, for when we returned at night we learned that the six cos. had been attacked by 1,500 of the enemys cavalry so estimated by some and by others 3,000. They were under command of brigadier general Forrest, they surprised the camp in the morning before daylight, they said they intended to kill every one of us in our beds before we had time to get our guns, but they ran their horses against the picket rope of the 7th Pensylvaina Calvary and that gave our men a chance to get out of their tents but not a chance to get into a line of battle, it was a bloody struggle and our men fought bravely, we lost 12 men killed on the spot, one lieut, one sargeant, one corporal, and 9 privates. We were momentarily expecting relief from the 3rd Minissota, which was in camp about a mile from us but the two colonels were not on verry good terms and the colonel of the third was a coward and so they did not come to there relief nor to the relief of the company at the courthouse and they had to surrender, the colonel of the 3rd Minnisota would not let his men fight–even when they were attacked, the right wing of his Regt. fired one volley only, and then surrendered, after the fight we spent many pleasant days at Tulahoma. We had some hard marches, we soon went to Manchester, again there we had our pickets driven in by the rebells, they wounded several men and took 15 prisoners but dared not attack us, soon after this we went back to Tulahoma on a train and co. I went to Stevenson, Allabama, we passed through a verry rough country on our road, the roughest railroad I ever saw, Stevenson is a small town situated at the foot of a mountain about 15 ms over the line between Tenn. and Allabama, this town has been a town of considerable business in its time, but like all other towns through which the army has passed, it is greatly damaged and does no business, only what is done by the government, there are several railroads that meet the Huntsville road, mets with the Chattenoga road, the Louisville and Nashville road comes in here and in times of piece it was quite a Southern town, we stayed here only one night and had but little time to judge of its inhabitance, but I think they are like all other Southerners, but little ingenuity, and less than the Kentuckyans, they are less intelligent.

Well we turned to Tulahoma on the following day and nothing happened worth mentioning. After arriving at Tulahoma, we went to Manchester, stayed there a few days and came to Tulahoma where we spent the rest of the time pleasantly until the 3rd of August, wile we stayed there we had evrything that we wished for although we were much of the time quarter rations, there was plenty of fruit in the country, peaches of the best kind and apples to, and we had the privilege of getting them whenever we wished, but it did not meet the approval of the inhabitance, but we could not help that, we had all the potatoes we had a mind to dig and all the fresh pork we were a mind to butcher and in this way we lived as well as we could wish to.

The night of the 2nd of August we had orders to march and early in the morning we were off on our retreat from the state of Tenn, we marched all day through the dust and with but little water, after dark we came into a small town called Wartrace, here we stopped for supper, went a half mile for our coffee water, we ate some hard bread and bacon for supper and then started, we made but slow progress during the night as it was quite dark and we had a large drove of cattle with us and five or six hundred contrabands of all kinds, men, women and children. During the night, one of the boys of the 15th Ohio shot himself through the arm and died the next night, he was lying on the ground and his gun lay between him and the fire, when he got up he took the gun up to keep it from going off but the cap was so hot it went off and the ball passed through his arm and shattered it to pieces, it bled terribly, the blood ran clear across the road like a brook. The next day we marched hard through the dust all day and without much water but as night came on we found the old city of murfreesboro, we stayed about two miles from the city till morning, then we took up our line of march again for Nashville, we arrived there after some days and nights hard marching without food or water. We stayed in Nashville from Sunday morning two oclock till Wednesday evening at 6, during our stay there we refreshed ourselves on sweet potatoes and other vegitables, we faired pretty well in comparrison with our march, we left Nashville for bowling green, Ky, on the evening of the 7th of Sept. and went out 10 miles on the cars, camped for the night, the next morning we set off again, we went 4 miles then we got orders to turn off and take the springfield road, here we left the rest of the troops and went on our way rejoicing, alone we marched 10 miles and stoped for further orders, here we remained all night, we captured two prisoners and all of the apple brandy that we could drink and carry off. The next morning we got orders to forward march to Springfield, we had marched for two or three hours when the order was countermanded, and we was ordered to go to bowling green, we marched back to the valley about 7 miles from Tyree Springs, Tenn, and camped for the night.

CHAPTER V.

The Flight, The Cave

The morning of the 11th of Sept. we began to climb the mountain, the name of it, I never learned it, it was a long steep winding road some five miles long, we took our way slowly up the mt. for it was a hot sultry morning and we were in no hurry, we stopped several times to get water and picked some grapes, when we got to the top of the mt. we rested nearly half an hour, then we marched on, we had gone about a mile and a half when we heard the word, forward double quick, all of our danger was unlooked for and we did not know the meaning of it but we soon saw in the road on top of a small nole some 30 rds in advance of us 3 or 4 horsemen, then the mounted men, some five or six in number set off in persuit of them at the best of their speed, we kept the double quick pace and soon came at the top of the hill, we saw the mounted men coming back, the Q.R. was wounded and our first lieut was shot through the left lung, our co. was ordered to deploy as skirmishers, which we did double quick, we had to pass through a large field, skirted on one side by woods, on the other by a cornfield, and a thick growth of underbrush, the enemy had a great advantage over us in two respects, first, they were in the woods and in the second place they had a much larger force than we had, we were in rather a weak position, we might have all been killed or taken prisoners for we contending against four times our number, but it so happened that forest would not have the rest of the 9th, we killed and wounded several of their men and drove the enemy, 4,000 strong, with about 200 men and two pieces of artillery under command of capt. swallow 7th Ind. battery, the fight lasted about an hour, the fight commensed about 10 in the morning and we stayed on the field till near night and were reinforced by a brigade, then we resumed our march and encamped 11 miles from the battlefield about 11 oclock, the next night we camped three miles from bowling green, Ky., the next day we went to Bowling Green and we explored the cave to a considerable extent. I went into the cave nearly a mile and went into all of the side rooms, as far as we explored there are some beautiful sights, there are rooms in this cave with their cavity hardly large enough to admit the body of a man and when you are in them they are hundreds of feet in length, some of them have beautiful springs of water in them, I broke a thin shell of stone in one room and found a nice spring concealed under it, the water was cool and nice, here are tracks of a different plain to bee seen in the solid rock, also many splendid specimens of stelagtites to be found here, some of them have the dripping from them looks of an icicle with water dripping from it, the main cave has a large stream of water running through it, this stream is formed by a large spring that rises out of the ground about 20 rods above the mouth of the cave, the cave in some places, and in fact the most of the way, five or six rds wide, and the wall over-head is from fifty to sixty feet high, in some places the water is deep and in some places the water runs under the rocks for rds, and then breaks out into rapid stream, the cave is said to be penetrable for three or four miles and it is certainly one of the grand works of nature, it is grand and beautiful and yet it makes one shudder to look into the gloomy darkness. I said the wall overhead was 50 or 60 ft. high, but there is one place that it is over 100 and in passing over here great caution must be taken or you would be dashed on the rocks below, this is all I have to say of the cave, we stayed in bowling green in fort bockner situated on colledge hill, about three months we were doing provost duty the most of the time, and passed the three months very pleasantly. The 3rd of Dec we were ordered to Nashville, Tenn, here we stayed two weeks and were appointed provost guards for the 14th army corps. which we have been ever since.

CHAPTER VI

The Stone River Fight and what happened till the present, I Co.

We left Nashville for Murfreesboro as provost guards for the 14th army corps, as I said before this was a hard march, we came within 11 miles of Murfreesboro, when we came here we were within sight of the rebell lines and the boom of cannon was occasionally heard but the darkness soon came on and the cannon was no longer, but when the day broke the battle was resumed again and we marched nearer the field, we marched some five miles and camped for the day and night but we had little idea what was to bee done the next hour, but we stayed that night and the next morning we were ordered to prepair for an inspection. I had my gun lock off and was just then detailed to pitch a hospitle tent for two or three wounded men had come into camp, just as we had got the tent up and I was driving a corner stake, I saw wagons, horses, negrows, and cavelry and at that moment the cry of turnout, turnout, was heard and the bugle was sounded, and here I dropped my ax and sprang for my gun, but where was it and in what condition, the lock off and not a moment to put it on, but I snatched a gun from a wounded man and in a moment more was in the ranks, and with a load in my gun, and in less than five minutes we were in a line of battle, and marched into the road and ordered to fix bayonets, we supposed the Rebells were right on to us for the road and fields were filled with cavelry coming toards us but which turned out to be a stampeed of our cavalry, they were running in every direction, they were like a flock of scared sheep, some of them threw their sabers, carbines and evry other arm they had about them, even officers threw their soards, and fairly begged to pass our lines but of no avail. We stopped the fright of the cavelry, we stood in line of battle all day and saw our men make a charge on the enemy after they had driven us back for some half a mile or so, and the enemy was soon driven back, and we continued to drive the enemy all day, and that night we camped about two miles nearer the town, the first day of 63 we marched to Nashville and that dawned the next morning, it was a long march and all were very tired before we reached the city, and that day we had another stampeed caused by the darkeys on account of the skirmish that took place at Levirn, half way between Nashville and Murfreesboro, the rebells attacked the first Mich. Enginers and Macanics for the purpose of burning a train but they got flaxed, they had 25 men killed and our men lost one man, the rebs burned some wagons.

We arrived at Nashville about 8 oclock in the evening, stayed there the next day, and the next day about an hour before daylight we took up our line of march again for Murfreesboro, we arrived there between nine and ten in the evening, that night we slept in the mud and the next day there was no fighting and had a day of rest for during the night the rebs had skeedadled and in the after noon I went over the battle-field and there I saw such sights as I never saw before, and hope I shall never see again, it was a sight–horrible to think of and more horrible to behold. There were men and beasts side by side. There were horses and their riders side by side. I have seen sights there that would make anybody but a soldier sick at heart. I saw there on that bloody field men with their arms and legs shot off, men with their heads shot off, and torn to pieces in every conceivable manner, many a man fell there who never knew what caused his death, and many more that suffered terribly. I saw lying side by side 100 of our men, they were buried in one grave upon that field long to be remembered by all who saw it, and those that will visit it in years to come, that place shall bee remembered for generations to come. I saw in one place all of the horses belonging to one gun killed by the explosion of one shell, there was six, and when I passed over the field it was in the afternoon of the next day after the fight, they had been engaged all day in burying the dead, and I saw hundreds yet lying upon the field yet untouched, many a poor fellow fell victim to this treasonable rebelion, many were the widows and orphans that were made in that bloody fight of six days. That is all I have to say of the fight now, perhaps I may tell you more when I come home, if I ever do. The next morning we came into the town and camped upon the old ground where we were taken prisoners, when we entered the town we found the dead rebs upon allmost every corner of the street, and for two or three weeks it was in the same way, they died faster than they could bury them, the first night that we stayed in the town and till the next day at noon, there was 150 buried in one place near our camp, but the most of them are parolled or sent north now there are but few left. The place is strongly fortified now, and quite a nice little town inside of the fortification is made out of old buildings that have been torn down. There is plenty of buildings for hospitils and barox for a large army and I guess I will call r osyville for it was built by his orders, all more that I have to say is that we are still in the old camp yet, and have the nicest I believe, in the whole corps.

I have been a long time writing this and the paper is rather dirty, but you need not let evrybody read it, perhaps it may be interesting to you, but it isn’t anything smart, if I never get home you may know something of what I have seen.

I made a mistake here and wrote on the rong side of the sheet but this is only one of the many you will find in reading this if you can read it at all, the writing is poor and the spelling to.

(F. Chamberlin)

Co. I, 9th Mich

Inft. – Vol

Murfreesboro

Tenn

I Finished April 5th

Ad 1863

Transcribed by Gordon Clemens and Barbara (McElhiney) Clauson; submitted to The Chamberlain Key by Catherine Sevenau, sister and cousin, respectively, of the transcribers, through James B. Parker, Chamberlain/Chamberlin historian

Notes from James Parker, 2008:

From time to time, one comes across a precious historical document of especial human interest that begs to be shared with other persons, primarily because of its poignant, moving narrative during a time of earth-shaking historical events. Such was the case with a Civil War letter passed along to me by Catherine Frances (Clemens) Sevenau, of Sonoma, California, who has been sharing her Chamberlin lineage with me. I’ve been helping her polish it up just a bit in recent weeks, prior the publication of her genealogy. Her great grandfather Finley Chamberlin’s longhand-written letter or journal, composed while serving in the Union Army, during February – April, 1863, covered his military experiences since joining a Michigan Regiment as Private, August 15, 1861. A transcription of this letter is concurrently being published for the first time in Catherine’s family history book (publication date pending). The book addresses the history of her Chamberlin, Hoy and Chatfield lines, along with several other family surnames, co-authored with her brother, Gordon Clemens, and entitled, “A Chamberlin Family History, subtitled, Bits & Pieces, Odds & Ends” Catherine has graciously given permission to reprint the Civil War letter at this time in the Chamberlain Key, for the benefit and pleasure of the members of the World Chamberlain Genealogical Society. This also provides me with an opportunity to write about Catherine’s own Chamberlin heritage, and other associated or allied Chamberlain/lin families, as documented in my Chamberlain research records. Of particular interest to me is our common pioneer heritage here in the State of Michigan. My special hobby is studying and documenting the genealogy of all Michigan Chamberlains (the first of whom were French Canadian trappers and farmers and English soldiers, during the 18th century at the military forts and settlements in Detroit and Mackinaw, long before Michigan became a U. S. Territory), but that is another story for another time.

Catherine Sevenau’s grandmother was Nellie Belle Chamberlin, born March 7, 1873, Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri, died January 2, 1956, Chico, Butte County, California, who married Charles Henry Chatfield, on December 26, 1894 in Grand Junction, Mesa County, Colorado. Ten children are listed for them including Catherine’s mother Noreen Ellen “Babe” Chatfield, born 1915, who married Carl John Clemens. Nellie Belle was one of six children of the Civil War soldier, Finley McLaren “Frank” Chamberlin, born Sept. 22, 1845, Middlebury Township, Wyoming County, New York, who lived with his parents on the family farm there through 1860. He evidently went by himself early in 1861 to Michigan where close relatives resided. His parents were Harrison Chamberlin and Caroline Surdam, who were married on November 21, 1841, in Wyoming County, New York, by Reverend Jesse Elliott.

Emily Hoy and Finley Chamberlin

To return to the subject of Finley “Frank” Chamberlin and his immediate family, he moved west after the Civil War, and was employed as a brakeman on the railroad in 1870 in Kansas City, Missouri. He was married in Anderson County, Kansas, on August 23, 1871, by Rev. Father Gunther, to Emily S. Hoy, born July 24, 1850, Howard, Centre County, Pennsylvania, who died February 18, 1940, in Los Angeles, California. Emily’s first marriage, in 1868, at the age of 17, to Frank Davis, was annulled, September 16, 1870. A daughter by this marriage, Winifred M. Davis, born August 22, 1869, probably in Iola, Allen County, Kansas, and was raised (perhaps adopted) by Finley after his marriage to Emily Hoy, so Winifred took the Chamberlin name.

Chamberlin siblings 1896, Denver, Colorado

Nellie Belle was the first of six known children born after Finley’s marriage, followed by Frederick Laurence “Fred” (1875) in Kansas, then four more children were born in Tarrant, Gregg and Johnson Counties, Texas: Ada Agnes (1877), Roy Valentine (1881), Mary Agnes “Mamie” (1887), and Willard Joseph “Jo” (1889). Evidently the marriage failed after almost 30 years – because they were Roman Catholic, rather than becoming divorced, they separated, in December 1898. The 1900 census lists Emily as a widow (she wasn’t), living with her three youngest children in Eldora Town, Boulder County, Colorado, supporting herself as a “restaurant keeper.” Emily continued to operate a restaurant and hotels in Cripple Creek, Colorado and in Fruita (located near Grand Junction, Mesa County), for many years. Her own family, the Hoys, were quite a colorful bunch, memorialized in Catherine Sevenau’s humorous poem about her ancestors which can be seen and enjoyed in her book.

Finley Chamberlin continued to work as a conductor for the railroads, affiliated with the Order of Railway Conductors, Division 338. He died of stomach cancer while staying with his daughter Nellie, in Rifle, Garfield County, Colorado, August 9, 1905, and was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery there.

Finley Chamberlin continued to work as a conductor for the railroads, affiliated with the Order of Railway Conductors, Division 338. He died of stomach cancer while staying with his daughter Nellie, in Rifle, Garfield County, Colorado, August 9, 1905, and was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery there.

by James Parker, Chamberlain/Chamberlin historian

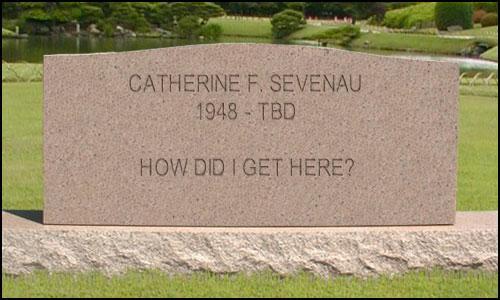

May 15, 2015

A Contemporary Mid-Century Classic

On my last marker birthday (sixty-fifth) I muddled over penning my obituary,

my epitaph, or a newspaper ad. My own obituary was too weird to write.

My epitaph was a no-brainer…

Since I’ve been in real estate forever, the ad copy was also easy:

Celebrate a Contemporary Mid-Century Classic

This small-town charmer shines with character and a colorful history. Endowed with good bones and on a solid concrete foundation, she is structurally sound in conjunction with notable internal integrity. Built in 1948, this gem is a prime example of definitive California architecture, and other than the well-maintained roof, is in original condition. Despite an outstanding location with gracious curb appeal, her interior is somewhat dated and shows a bit of wear and tear. No major complaint or disclosure issues, no plumbing leaks or wiring problems,  no illegal permit or zoning headaches, but does bear some slight quirks: two partially fogged windows, various rusted hinges, a few loose screws, and several stiff, creaking doors. There are minor holes in the ceiling (allowing hot air to escape), along with dinky wall dents here and there. No termites or beetles, but possibly squirrels in the attic. Well tended and generally low maintenance, though can be temperamental depending on the weather. Recently smudged for ghosts. For a quick turn-a-round, an authentic plastic St. Joseph statue is buried upside down in the front yard. Comes fully insured with newly minted historical designation. Well-documented archival background information on request.

no illegal permit or zoning headaches, but does bear some slight quirks: two partially fogged windows, various rusted hinges, a few loose screws, and several stiff, creaking doors. There are minor holes in the ceiling (allowing hot air to escape), along with dinky wall dents here and there. No termites or beetles, but possibly squirrels in the attic. Well tended and generally low maintenance, though can be temperamental depending on the weather. Recently smudged for ghosts. For a quick turn-a-round, an authentic plastic St. Joseph statue is buried upside down in the front yard. Comes fully insured with newly minted historical designation. Well-documented archival background information on request.

May 9, 2015

A Defining Moment

Audio: A Defining Moment * December 1953, San Jose (click arrow to listen)

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/9.-A-Defining-Moment-•-1953-San-Jose.mp3

I don’t remember how I got there or who dropped me off, perhaps Daddy waited in a car across the street, or maybe the family I’d been living with brought me. Who knows? It didn’t really matter; I was coming to live with my mother! I bunny-hopped on her doorstep, the butterflies in my stomach on the wing. Not tall enough to reach the knocker, I rapped twice on the door. She would be so happy to see me!

The front door opened. Standing there, she glanced over my head. She stepped back and let me pass, then closed the door and turned. Picking up my small yellow and white, brown-striped suitcase, I trailed after her.

The front door opened. Standing there, she glanced over my head. She stepped back and let me pass, then closed the door and turned. Picking up my small yellow and white, brown-striped suitcase, I trailed after her.

Working as a cook and housekeeper for two Irish Catholic priests, my mother lived in a small room off the church’s rectory. She led me to the dining room and pointed to a place at the end of the pew against a wall, then disappeared into the kitchen through the white Dutch-door.

Her voice tight, she ordered: “Be quiet and behave,” followed by, “sit there and don’t touch anything.”

With my Naugahyde case deposited on the floor under the pew, I dangled my feet, sitting very still on the hard bench, obediently folding my five-year-old hands in my lap. I studied the red-flocked wallpaper, the tatted doilies, the long rectangular dining table set for two: the wine goblets, silver spoons, the scatter of white plates, linen, crystal, and pewter… all waiting in silence, like me. Wondering how I got there and pretty sure I hadn’t done anything wrong, I’d wait most of my life for her to come back to me. She never did.

May 1, 2015

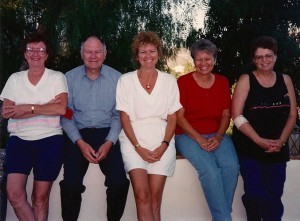

A Billet-Doux to My Siblings, 2004

Audio: Billet-Doux (condensed version) click arrow to listen

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/19-Billet-Doux-to-My-Siblings-•-2004.mp3

Dear Gordon (Larry) and Marian, Carleen, Liz (Betty), and Claudia,

My writing began with “Queen Bee.” When I shared it with each of you, it gave us a connection we hadn’t had. I also read it to our cousin Marceline whom I’d met at a Chatfield reunion a few years back, where she told me stories about Mom, how warm, friendly, and funny Mother was. It startled me to hear anyone say anything good about Mom, to hear her spoken of in such a friendly fashion. Carleen and Liz, your anger with Mother had been so intractable, and my own experience of her difficult, that I thought perhaps Marceline was mixing her up with someone else.

Reconnecting with Marceline a year ago, I invited her and the five of you to my home. I wanted to know more about our mother. Thirty other relatives got wind of the get-together and showed up on my doorstep, arms loaded with food and soft drinks; it turned into a wonderful weeklong party.

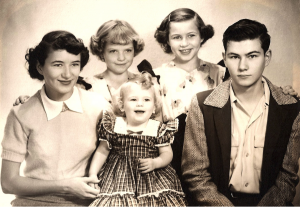

Clemens siblings: Carleen, Gordon (Larry), Catherine (Cathy), Liz (Betty), Claudia, 1993

Four generations—brothers, sisters, cousins, nieces, nephews, children, and grandchildren—sat in a double circle in my living room. I asked everyone in turn to say how they were related to Mom, along with a memory or story of her. That night I wrote the tales told and read them aloud in the morning. Everyone thought my writings were funny, except you, Gordon—you weren’t so sure—but you had a different family life than we did. Those few tales triggered others, and then others, and when they’d all been written down, I had a book. Chronicled throughout are diaries, letters, and clippings stashed for years in your garages, attics, and closets. My own memories and assumptions are cluttered in between.

Clemens siblings, Sonora, California, 1950

Carleen, Claudia, Cathy (Catherine) in middle, Betty (Liz), Larry (Gordon)

Relieved when I got your first responses to my draft, Carleen, Liz, Claudia, and Marian, you all said, “I laughed, then I cried, then I laughed some more.” I worried what you would say, Gordon. Until you’d read my first draft, you’d only heard what I’d read to you on the phone. I often felt your pursed lips and folded arms over the line. The day I received your edited copy, I was afraid to unseal the manila envelope. I circled it for an hour, tapping it with my fingers each time I walked by the kitchen table, waiting for courage to open it. I didn’t want to risk our relationship, you’re the only brother I have.

I cried when your note said my writing impressed you, and that you hadn’t known what had happened to all of us after you’d left home. You also didn’t ask me to take anything out, except where I wrote that you had hunted for frogs, informing me that you had NEVER hunted for frogs. I also laughed when I saw you crossed out all the swear words. And I want to thank you for your generosity in allowing me to print something so personal as your diary; it tied the story together. I love you, I love that you are my brother, and I appreciate your support in writing our stories.

Marian, you’ve been a huge buttress, reading drafts and running interference. You loved my writing and asked me if I was ever going to write fiction. My brother––your husband––responded with, “She is writing fiction.” What I love the most about you is your kindness and patience. You soften my edges, reminding me by your example of another way to be. I love you dearly.

Carleen, thank you for being our mother when Mom was unable, to not only take us in and provide food and shelter, but to give us love, laughter, attention, and family. Your home and heart were always open, and I might not be here today if not for you. Thank you. I am grateful for the woman you are, and I love you with all my being.

Liz, thanks for putting up with me on the phone, sometimes two and three times a day, patiently listening, correcting, and making me take out what I made up. “Riddled with errors, as usual,” you’d quip. Your memory, knowledge, and stand for the truth make a difference. I’m also grateful you’re still speaking to me after I decided, against your request, to include some painful things that happened to you when you were young. I can only trust it was the right decision. I love you. Fiercely.

Claudia, your stories have been the best. You had the closest connection with Mom (actually, you were the only one with the fortitude to listen to her), so you have memories the rest of us lack. I laugh each time we talk, and feel your arm around me. I hope I’m not still “nothin’ but trouble” for you with what I’ve written. I love you (and your chocolate chip cookies).

What I thought would be a few vignettes has turned into this memoir, reaching back through our generations and growing into a body of work. I wrote it for you, and I wrote it for me. It gave me a place to say what I wanted to say, it brought me clarity and tenderness as I witnessed my childhood, and it brought me back to myself. It also united our family in more ways than just these pages. I’ve always said, “If it had been up to me, I’d have kept the family together.” Well, I’ve done that, and then some.

Catherine “Cathy” Frances (Clemens) Sevenau,

Carl & Babe’s youngest child

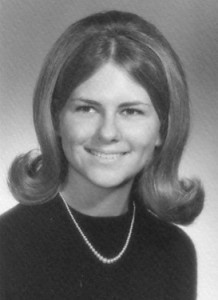

Stephanie Moore

P.S. Writing a book is not a solitary event, and this one would never have emerged without my friend and teacher, Stephanie Moore. Years ago she taught me to dance, today she is teaching me to write. Thanks to my Monday night writing class who gives me their attention and feedback a page and a half at a time. And thank you to my brother, sisters, and a few friends who so generously read my drafts, helped me arrange and rearrange this book so it’s not so confusing, editing my commentary, encouraging me, and nudging me to get to the point.

I also thank my other mentors in their general order of appearance in my life:

My ex-husband, who allows me to wrestle with my resentment on a regular basis and who affords me his ankle to chew on so my sons’ ankles get a rest; and my sons who offer me the constant opportunity to keep my mouth shut, which I seldom take.

Jerry Silver, my group therapist, who told me I had choices and I told him if I made those choices people would get mad at me, to which he replied, “So?”

My friends, Charlie Price and PJ Tyler, who believe in me and see me bigger than I ever see myself.

My broker, Art Fichtenberg, who taught me about real estate and cautioned me about throwing kerosene on a small campfire.

Peter Fairfield, who asserted that we choose our parents and I fell off his acupuncture table, laughing.

Rita George, the first person who told me there might be something happening on another level and I might want to pay attention and listen and I said, “Huh?”

Justin Sterling, who clarified in The Women’s Weekend why I was not in a long-term, committed relationship with a man, and who made me seriously question if it was worth all the effort.

Michael Naumer, my teacher, who had me turn my pointed index finger gently around to myself, without breaking it, to see my part; who had me see that things aren’t happening to me, but that they are happening for me; and reminded me that people are miraculous surprises.

Kris Saks, who brought home three lessons: the distinction of inner resources vs the resources of others, the fallout when entitlement trumps integrity, and the Fourth Law of Karma.

Gary Ruiz, who shiatsus me back into my body, listens to me, and who thinks I’m funny.

Shauna Wilson, who counseled me that my anger was so deep I wasn’t even able to tap into it. Now if she’d asked me about my resentment…

Dennis Mead-Shikaley who, in his radical coaching workshop, helped me leave my father’s house.

Ulrika Engman, my yoga teacher, who quieted my mind and loosened my body and cheered me on until I could touch my toes.

Connie Kaplan, who said I incarnated in the field of resistance and I said like that is supposed to be news that isn’t obvious to the whole planet? She said, not that kind of resistance. That I am like a resistor in electricity: when people meet me, their lives take a different direction.

Charlie Bloom, who informed me that I make a difference by being simply who I am and I still find it difficult that it is that easy.

My grandson, who reminds me to have FUUUN and say SUUURE; who shows me how I could have done a few things differently with my sons, but that as his Oma, I do just fine.

And last, Karla McLaren, who in her course Emotional Genius showed up as my mother, opening wounds and emotions in me that were buried and scarred over long ago. Due to her course, I wrote “Queen Bee,” and (my tongue is bleeding here) I thank her.

April 24, 2015

Positively Haight Street * 1968

Audio: Positively Haight Street (click arrow to listen)

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/18.-Positively-Haight-Street-•-1968.mp3 1968 was the year Eldridge Cleaver published Soul on Ice. He and his wife Kathleen, who had the most immense head of hair I’d ever laid eyes on, banked at my teller window. It was the year of the Yippies, Black Panthers, and the SDS, the year Martin Luther King was shot in Memphis—sparking riots across the nation. The day after his murder, hundreds of black kids from Poly High rolled down Haight in a tidal wave, smashing storefront windows and overturning cars.

1968 was the year Eldridge Cleaver published Soul on Ice. He and his wife Kathleen, who had the most immense head of hair I’d ever laid eyes on, banked at my teller window. It was the year of the Yippies, Black Panthers, and the SDS, the year Martin Luther King was shot in Memphis—sparking riots across the nation. The day after his murder, hundreds of black kids from Poly High rolled down Haight in a tidal wave, smashing storefront windows and overturning cars.

1968 was the year of sweeping anti-war protests, the Tet Offensive and the My Lai massacre, the year the Viet Nam war ripped our country inside out. It was the year of the Democratic National Convention and the Chicago riots. Sirhan Sirhan assassinated Bobby Kennedy at the Los Angeles Ambassador Hotel, women were branded as bra-burning feminists, and 32 African nations boycotted the Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Richard Nixon was elected president, and Apollo 7 and 8 were launched.

I existed in the eye of this turbidity—not oblivious—but not overly concerned or connected to the world’s chaos. Dressed in my starched white button-down blouse, navy A-line skirt, pantyhose, white flats, Coral Sea lipstick and a helmet-head Summer Blonde flip, I watched with detached interest the swirl of humanity through the plate glass windows of my dad’s five-and-dime and the corner bank across the street.

I existed in the eye of this turbidity—not oblivious—but not overly concerned or connected to the world’s chaos. Dressed in my starched white button-down blouse, navy A-line skirt, pantyhose, white flats, Coral Sea lipstick and a helmet-head Summer Blonde flip, I watched with detached interest the swirl of humanity through the plate glass windows of my dad’s five-and-dime and the corner bank across the street.

In my world, 1968 was the year the neighborhood stores closed, leaving empty shells with boarded windows. The customers were fed up with grungy panhandlers constantly asking for spare change to feed their mangy bandana-necked dogs, tired of stepping over stoned fourteen-year-old runaways who looked like five miles of blank road, and had it with being hustled by dreadlocked junkies, spaced-out punks, and blissed-out barefoot bums. The regulars hailed streetcars to Irving or took the bus over to Market, then eventually moved out of the Haight altogether.

1968 was the year Daddy’s store closed. The Summer of Love, the riots, and the changing times did my father’s business in. I find it worthwhile to note that his history echoed the same song from fifteen years earlier, the times again cracking my Dad’s foundation and walls. Once again, he sold his stock, boarded his windows, and locked his front glass door, and—once again—left town.

1968 was also the final straw for my mother. That was the year she ended her life in a small hotel on Whittier Boulevard, closing a chapter on mine.

1968 was also the final straw for my mother. That was the year she ended her life in a small hotel on Whittier Boulevard, closing a chapter on mine.

April 17, 2015

Sweeney’s Penny Candy

On Haight and Belvedere, tightly wedged between my Dad’s dime store and Superba Market, was Sweeney’s. The Sweeneys were a sweet, white-haired old couple who lived in the flat above their penny candy shop. Actually, now that I think about it, Mr. Sweeney was on the crusty side, a big

On Haight and Belvedere, tightly wedged between my Dad’s dime store and Superba Market, was Sweeney’s. The Sweeneys were a sweet, white-haired old couple who lived in the flat above their penny candy shop. Actually, now that I think about it, Mr. Sweeney was on the crusty side, a big  man, balding on top, with muttonchops and a bushy mustache. They sold ice cream too, and when it was hot, which was seldom during the summer in San Francisco, Daddy and I would pop in after lunch for a single chocolate cone or a soda pop.

man, balding on top, with muttonchops and a bushy mustache. They sold ice cream too, and when it was hot, which was seldom during the summer in San Francisco, Daddy and I would pop in after lunch for a single chocolate cone or a soda pop.

Sweeney’s was a dingy, narrow establishment with rows of begrimed glass cases filled with penny candy. As you stepped through the front door, a swirl of stale vanilla, banana taffy, musty cocoa, and a hint of mice wafted up; you were greeted by gumballs and gumdrops in tumbled mounds, by lollipops standing quietly waiting to be adopted, by elbowing jumbles of jelly-beans and jujubes hoping to be chosen instead. The chewy Abba Zabas and Sugar Daddys begged for attention while shy Tootsie Pops stood with their scarves wrapped tightly around long skinny necks. The caramels kidded with the strawberry taffys and the bubble-gum teased the jawbreakers. The red wax lips flirted shamelessly with the candy cigarettes every time Mr. Sweeney turned his back.

Aloof at the end of the counter were the bins of stale cherry, raspberry, and coconut bonbons, thinking they were somethin’ else, having no idea that they could never compete with See’s. The pedestrian Mallos jealously jousted with Peppermint Patties dressed in their elegant silver jackets, while the candy buttons stood in polite lines on paper strips, glad not to be part of the fray. The worldly licorice whips slumped side-by-side, naked and bored by the whole thing.

The black licorice never called to me, nor did the Fireballs, but the Pixy Stix did, doing the Hokey Pokey in their tall glass jar, frantically waving their folded ends, aflame with hope shouting, PICK ME! PICK ME!” They leapt into my pocket as I flipped my nickel heads or tails, then clinked it on the glass counter top.

In the 1950s, a nickel bought you a pocketful of everything from a penny candy store.

April 11, 2015

A Civil War Story

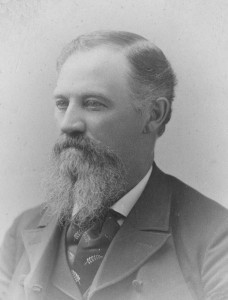

Isaac Willard Chatfield: 1836 – 1921 Ohio to California

1836: Middlefield, Ohio Isaac Willard Chatfield was born in 1836, the first of four children of Levi Tomlinson Chatfield and Lovina Mastick. Isaac married the elegant Eliza Ann Harrington May 20, 1858, and over the next five decades he and Eliza pioneered across the country, settling parts of Kansas, Colorado and Wyoming.

Isaac Chatfield

Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, and the day after his twenty-fifth birthday, Isaac traveled to Havana, Illinois, where on August 3, 1861, he enlisted in the Union Army as a private in Company “E” of the 27th Regiment, Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Because he was educated, he was immediately commissioned to second lieutenant.

In the winter of 1862 in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Isaac fought in the Battle of Stones River. Fighting in that same engagement was sixteen-year-old Finley McLaren Chamberlin, a private in the 9th Michigan Volunteer Infantry, a young man whose daughter would marry Isaac’s son 32 years later.

Eliza Harrington, 1865

With more than 250,000 Illinois men serving as volunteer soldiers, virtually every Illinois woman was the mother, sister, daughter, cousin, aunt, or wife of a soldier. Duty also called Eliza, and although she was a young mother of a three-year-old daughter and had lost a second child at birth just five months before, she joined the Civil War as one of the 5,000 Union Army nurses. In February of 1862 she served at the Battle of Fort Donelson in Tennessee. This was General Ulysses S. Grant’s first important victory, at the cost to the nation of 507 Union and 327 Confederate fatalities, and more than 2,500 Union and almost 14,000 Confederate casualties. Two months later Eliza, one of five thousand female nurses serving in the war, was at the Battle of Shiloh where General Grant’s troops encountered the Confederate troops of Generals Stonewall Jackson and P.T.G. Beauregard. Overwhelmed by sickness during battle along with the weariness of war, the memory of thousands of men dying, and the horror of crimson staining the land, Eliza was taken to St. Louis, Missouri, to recover. The carnage on both sides was overwhelming: the Union lost 1,754 men, 8,408 were wounded, and 2,885 were captured or missing. The Confederacy had 1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 captured or missing.

Isaac “I.W.” Chatfield

In 1863 Isaac was medically discharged from service for a severe kidney and bladder affliction. He spent the rest of his life farming and cattle ranching, making large profits from the sales of his Colorado holdings. He served as a Republican (anti-slave party) City Alderman, and went on to be elected to the Colorado State House of Representatives. He owned silver mines and was also a railroad contractor, hiring 500 rock-men to work on the grade for the Denver and Rio Grande short-line to Leadville. He had a love for horses and horse racing; the amount of his losses often significant enough to be mentioned in local newspapers. Having become one of the wealthiest men in Colorado, he could afford to lose.

In 1864 Isaac and Eliza crossed the plains driving an ox-team, homesteading near Florence, Colorado. They then moved to Leadville, Aspen, and Denver, finally settling in the Bighorns near the town of Basin, Wyoming. The family travelled in clans, brothers and cousins and uncles homesteading near one another. The Chatfield men were farmers, cattle ranchers, horse traders, railroad builders, mercantile owners, hoteliers, politicians, and mine stockholders. The women were opera singers, musicians, teachers, seamstresses, shopkeepers, and landowners. Devotion to God, family, hard work, and common sense ruled the order of the day.

Eliza (Harrington) Chatfield

On June 12, 1911, after fifty-three years of marriage and nine children (four of whom she buried), Eliza died from uterine cancer, her burial services under the auspices of the Christian Scientists.

Shortly after Eliza’s death, Isaac moved to Princeton, California, a rural rice-farming community in the sun-heated Sacramento Valley. Two years later, in late August of 1913, Isaac married a second time to the widowed Sarah Jane Wisenor—much to the great displeasure of the family who did not think he should be marrying again, much less so soon, and particularly at the age of seventy-seven. He too may have been dubious, as he lied on his marriage certificate, claiming he was sixty-seven.

Charles Henry Chatfield

Six of Eliza and Isaac’s children attended the Brinker Collegiate Institute in Colorado, a co-educational finishing school. However, Isaac’s fourth son and sixth child—my grandfather Charles Henry Chatfield—preferred the skating rink. Charles, the designated black sheep of the family, was born on his father’s 280-acre cattle ranch in 1870 in the Colorado Territory. Charles was a champion ice-skater at sixteen, an experienced ranch hand at eighteen, and a married man at twenty-four. The afternoon he married Nellie Belle Chamberlin, the fun was over.

Isaac Willard Chatfield: Find A Grave

Eliza Ann (Harrington) Chatfield: Find A Grave

Charles Henry Chatfield: Find A Grave

April 4, 2015

A Confused Heart and a White Train

October 7, 1967 • San Francisco

On a crisp October day, my father escorted me down the carpeted aisle of Holy Name of Jesus, our church in the Sunset.

I looked like a fairy princess, dressed in the white wedding dress my stepsister wore when she married. It fit like a dream: white lace, cap sleeves, darted at the waist… not a dress I would’ve chosen, but beautiful, the train following me, my knees shaking, my lips twitching, my mouth so dry my lips were stuck to my teeth like a fool’s tongue on a frozen flagpole. Six-foot-six Father O’Shaughnessy, in his black robes, smiled his handsome crooked tan smile. Our four bridesmaids (my three high school friends and my niece Debbie, fourteen and stoned) wore matching, full-length, empire-waist coral bridesmaid dresses, holding bouquets of dyed carnations and baby roses. The four ushers (Bob’s two school friends and two brothers) dressed in black tails, and Bob, looking baby-faced and nervous, waited for us expectantly at the altar.

I looked like a fairy princess, dressed in the white wedding dress my stepsister wore when she married. It fit like a dream: white lace, cap sleeves, darted at the waist… not a dress I would’ve chosen, but beautiful, the train following me, my knees shaking, my lips twitching, my mouth so dry my lips were stuck to my teeth like a fool’s tongue on a frozen flagpole. Six-foot-six Father O’Shaughnessy, in his black robes, smiled his handsome crooked tan smile. Our four bridesmaids (my three high school friends and my niece Debbie, fourteen and stoned) wore matching, full-length, empire-waist coral bridesmaid dresses, holding bouquets of dyed carnations and baby roses. The four ushers (Bob’s two school friends and two brothers) dressed in black tails, and Bob, looking baby-faced and nervous, waited for us expectantly at the altar.

It’s better that I didn’t invite Mom. It would be too hard on Daddy and she would’ve wrecked this, and besides, I haven’t seen her in years and she wouldn’t care anyway.

I thought about how hard Marie worked to make this a beautiful wedding, about what it cost and how Daddy used his inheritance money, about how far everyone traveled. I wanted to run—but I didn’t make promises lightly; I also didn’t want to disappoint everyone. As I peered out from under my veil at 150 people, our families and friends, our parents’ friends, Bob’s mother… oh my god, she looks like a leprechaun! She’s got on a green, knee-length, lace-covered dress and matching pantyhose, a green flowered hat and veil, green eye-shadow, holding a green handbag, with her feet stuffed into three-inch, dyed-to-match podesua heels barely making her five-foot tall. I was bobbling on the edge of hysteria. I glanced sideways at my father, looking so handsome in his tuxedo; I could smell his lapel flower and his splash of Old Spice. I forgot about Velma (who wasn’t particularly thrilled about her little Bobby marrying me) and moved into a silent rant with him.

I thought about how hard Marie worked to make this a beautiful wedding, about what it cost and how Daddy used his inheritance money, about how far everyone traveled. I wanted to run—but I didn’t make promises lightly; I also didn’t want to disappoint everyone. As I peered out from under my veil at 150 people, our families and friends, our parents’ friends, Bob’s mother… oh my god, she looks like a leprechaun! She’s got on a green, knee-length, lace-covered dress and matching pantyhose, a green flowered hat and veil, green eye-shadow, holding a green handbag, with her feet stuffed into three-inch, dyed-to-match podesua heels barely making her five-foot tall. I was bobbling on the edge of hysteria. I glanced sideways at my father, looking so handsome in his tuxedo; I could smell his lapel flower and his splash of Old Spice. I forgot about Velma (who wasn’t particularly thrilled about her little Bobby marrying me) and moved into a silent rant with him.

“How did I get here? How could this be happening? This is your fault! If you hadn’t jumped up and nearly knocked your chair over at Bob’s birthday dinner party when he announced we were getting married with your “oh no…”

And so, with my family and friends as witnesses—against all my better judgment—with a confused heart, a bowed head, a white train, and a full Mass, I married a boy who shared the same thimble-full of common sense as me.

March 27, 2015

Bee Sting and a Dead Roly-Poly

1955, San Jose, California

I read whatever was in front of me. I read all four sides of the milk carton and the Cheerios box and the C&H container. I read the editor’s notes and publication dates and fine print in the front of True Detective and Reader’s Digest and Cornet or whatever Mom left on the table. If I’d finished my last stack of Nancy Drew mysteries from the library, I read our new four-inch-thick 1955 Webster’s Combined Dictionary and Encyclopedia that Larry gave us for Christmas. I studied the colored pictures of the plants and animals until I knew them by heart.

I read whatever was in front of me. I read all four sides of the milk carton and the Cheerios box and the C&H container. I read the editor’s notes and publication dates and fine print in the front of True Detective and Reader’s Digest and Cornet or whatever Mom left on the table. If I’d finished my last stack of Nancy Drew mysteries from the library, I read our new four-inch-thick 1955 Webster’s Combined Dictionary and Encyclopedia that Larry gave us for Christmas. I studied the colored pictures of the plants and animals until I knew them by heart.

When I got bored reading indoors, I went outside and read, or lay in the yard in the afternoon sun, warming my face and body, feeling the heat on my cheeks, keeping my eyes closed (no way was I going to go blind looking directly into the sun). The long fair baby hair on my arms stirred in the breeze; my hair was the grass and I was the earth. Listening to grasshoppers rasping in my ears, feeling a small brown butterfly kissing my arm with its tiny eyelash feet, I breathed in the loamy odor of dirt and chewed on a long stem of sour grass. I talked to myself and to God, and kept an eye out for the mangy dog next door and the honeybees hovering over the white clover and alyssum making sure no bees buzzed under me before I settled down. I‘d been stung before, when I was four, when we lived in our white two-story house in Sonora. It was my first memory. Running to the store screaming for Daddy, he caught me, told me to calm down, pulled the stinger out of my back, and said it was only a bee sting and that I’d survive. I wasn’t so sure.

I flipped over and dug my elbows and knees and wiggled my toes into the dark cool dirt, scratching my bare legs where the rocks and stickers poked through the razored Bermuda grass. Beneath my nose I studied an army of black ants scurrying with their top-heavy loads, building cities with tunnels and pyramids. One procession transported a dead roly-poly, another dragged an earwig to feed their industrious six-legged troops. I was most careful not to squash them or breathe too hard and wreck their work. I did however put a twig in their way to make their lives more interesting. I was pretty sure that wasn’t a sin.

I flipped over and dug my elbows and knees and wiggled my toes into the dark cool dirt, scratching my bare legs where the rocks and stickers poked through the razored Bermuda grass. Beneath my nose I studied an army of black ants scurrying with their top-heavy loads, building cities with tunnels and pyramids. One procession transported a dead roly-poly, another dragged an earwig to feed their industrious six-legged troops. I was most careful not to squash them or breathe too hard and wreck their work. I did however put a twig in their way to make their lives more interesting. I was pretty sure that wasn’t a sin.

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers