Catherine Sevenau's Blog: Writings~Rambles~Rhymes, page 62

October 25, 2015

Cookies and Love

Char Girl~

I had my four-year-old grandkidlet on Saturday. We’re making cookies and she begs to take over mixing the flour.

“I do it, I do it. Let me, let me.”

Cleaning up, as there was now batter everywhere, we put a load of towels in the washing machine.

She stops me again with, “I do it. I do it! Let me, let me!”

Then I pull out the vacuum to clean the floor dusted in flour.

Again, “I do it, I do! Let me, let me!”

While the cookies are cooling, Theda Bara looks up at me with her baby blues, puts the back of her hand on her sweet forehead and moans, “Work, work work! All I did today was work! I had to cook, I had to do laundry, I had to vacuum. I had to do everything! I’m exhausted!”

“Poor little char girl,” I say in sympathy. “Here, have a cookie, it’ll revive you.”

2012

Food Fans~ Temple and I cook together, then we eat, and while we eat, we list all the ingredients in the dish.

Temple and I cook together, then we eat, and while we eat, we list all the ingredients in the dish.

During dinner she inquires, “What are you a fan of?”

Having no idea what she means, I say, “What?”

She says, “You know, food, what foods are you a fan of.”

I say, “Oh, well, I’m a fan of shrimp, asparagus, sushi, and dark chocolate.”

She then asks, “What are you not a fan of?”

I answer, “Black licorice, coffee, and wine.”

So of course I ask her, “What are you a fan of?”

She says, “Broccoli and kale.”

I say, “You are the oddest five-year-old I have ever met.”

2013

I Like Kids, Mainly Fried~

While fixing breakfast together, Temple says, “Oma, we should open a restaurant.”

I tell her, “Sure, I’ll be the prep cook because I’m the one who knows how to measure, and you can be the one who pours and stirs and flips.”

“I can only work two days a week during the summer,” she says, “because I have swim lessons.”

December 2014

Talk to the Hand~

It’s Saturday morning. As Temple unloads the silverware from the dishwasher she announces that the drawer is a bit of a mess. I offer to let her straighten it. She wants to know why I have five pairs of reading glasses in there. I tell her that’s where they hide, which is why I have to buy new ones. (I wondered where they were!) She rolls her eyes. When she’s done, I offer to have her straighten two more. She’s appalled that they, too, are such a jumble; after ten minutes she has them in great order. I had things in there that not only had I never used, I wasn’t even sure what they were for. She proudly shows me both drawers, faces me and spreads her arms like guardian angel wings to protect them, admonishing me that I’m no longer allowed to go in either one, and if I do, they’d better look like this next time she’s here. I tell her to talk to the hand. Sheesh.

May 2015

Flip of a Switch~ Temple and I are making a mango smoothie. With the blender nearly full, I say, “You have to remember not to flip this switch up unless the lid is on.”

Temple and I are making a mango smoothie. With the blender nearly full, I say, “You have to remember not to flip this switch up unless the lid is on.”

She reaches over and flips it. In shock, we look at the walls and each other, now dripping in mango and yogurt.

“Like that?” she says.

“Like that,” I say.

“Sorry,” she says.

“I know,” I say.

June 2015

October 9, 2015

A Batch of Broken China

my mother, Noreen Clemens

Over the past years my mother has been following me around, showing up in my stomach, my bones, and my dreams. She used to be a dull ache inside me, but not so much anymore. She wasn’t cruel or abusive—there was no sliver to take out, no bullet to remove, no thorn to pluck. In the five years I lived with her, I wasn’t raised by co-mission, I was raised by omission, by neglect, but neglect doesn’t leave a scar, it leaves a hole. Some say holes are harder to heal.

I’ve spent the last thirty years trying to fill this hole: with sex and recreational drugs (God bless the 70s!), with work, and now with writing. Much like my mother, I’ve been looking for answers. She went the conventional way of the 1950s, going to doctors up and down the state trying to find out what was wrong with her, getting prescriptions for depression, weight, sleep, and for whatever else possessed her. I’ve gone from A to Z in search of understanding, attempting to heal the ache in my stomach, release the pain in my shoulders and jaw, and let go of the resentment I hold in my body. Time and understanding have reshaped me, transforming this hole into a kind of wholeness, and out of this wholeness, a kind of holiness has emerged.

So after all my seeking and searching, hoping for some comprehension, I’ve come full circle back to my mother. “Why?” doesn’t matter nearly as much as I thought it did. Mom didn’t think about the ripples caused by the rocks she cast in the waters. She wasn’t out to purposely make my life unhappy or irritating, didn’t have me in mind when she made her choices. It wasn’t about me. Somehow I knew that even as a kid.

I imagine my mother would have preferred it to turn out some other way, to not have stumbled and tripped through her life leaving a batch of chipped and broken china in her path, waltzing a mindless waltz in endless circles. Don’t you think she would have liked to have held the hemmed edge of her billowing skirt and elegantly danced? I do. Like her, I too can be a little clumsy, but unlike her, I learned to dance: to twirl and tango and two-step. I love when I float across a shiny wood floor, gliding and swirling and turning like a warm breeze on tiptoe; I never dreamed I could be a dancer.

Many of mother’s belongings have found their way back to me. Her heavy pinking shears are now in my sewing box. Her black cast-iron griddle cooks my grilled cheese sandwiches. Her delicate gold watch with the narrow black cloth wristband, her Liberty half-dollar necklace from the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair, and her silver charm bracelet crowded with mementos from her life all keep my jewelry company. Her pictures are on my wall and in my photo albums. Her mother Nellie’s round English deco mirror hangs in my bedroom, reflecting all three of our images in my face. I also have her metal meat grinder (the one she ran my right index finger through when I was not yet two), stored in an old workman’s aluminum lunch pail, way up high on a shelf in my garage where it can’t get me. My sisters and brother must have thought these things important to me, that I should have them. They are. I’m pleased when I use or look at or wear them. They remind me of Mother, remind me of some good parts of her. And they remind me of what I missed.

For years I didn’t think about her at all. For a while I thought about her more than I needed to. Now, when I think of her, it’s easier, and it feels like we can dance.

A Batch of Chipped and Broken China

my mother, Noreen Clemens

Over the past years my mother has been following me around, showing up in my stomach, my bones, and my dreams. She used to be a dull ache inside me, but not so much anymore. She wasn’t cruel or abusive—there was no sliver to take out, no bullet to remove, no thorn to pluck. In the five years I lived with her, I wasn’t raised by co-mission, I was raised by omission, by neglect, but neglect doesn’t leave a scar, it leaves a hole. Some say holes are harder to heal.

I’ve spent the last thirty years trying to fill this hole: with sex and recreational drugs (God bless the 70s!), with work, and now with writing. Much like my mother, I’ve been looking for answers. She went the conventional way of the 1950s, going to doctors up and down the state trying to find out what was wrong with her, getting prescriptions for depression, weight, sleep, and for whatever else possessed her. I’ve gone from A to Z in search of understanding, attempting to heal the ache in my stomach, release the pain in my shoulders and jaw, and let go of the resentment I hold in my body. Time and understanding have reshaped me, transforming this hole into a kind of wholeness, and out of this wholeness, a kind of holiness has emerged.

So after all my seeking and searching, hoping for some comprehension, I’ve come full circle back to my mother. “Why?” doesn’t matter nearly as much as I thought it did. Mom didn’t think about the ripples caused by the rocks she cast in the waters. She wasn’t out to purposely make my life unhappy or irritating, didn’t have me in mind when she made her choices. It wasn’t about me. Somehow I knew that even as a kid.

I imagine my mother would have preferred it to turn out some other way, to not have stumbled and tripped through her life leaving a batch of chipped and broken china in her path, waltzing a mindless waltz in endless circles. Don’t you think she would have liked to have held the hemmed edge of her billowing skirt and elegantly danced? I do. Like her, I too can be a little clumsy, but unlike her, I learned to dance: to twirl and tango and two-step. I love when I float across a shiny wood floor, gliding and swirling and turning like a warm breeze on tiptoe; I never dreamed I could be a dancer.

Many of mother’s belongings have found their way back to me. Her heavy pinking shears are now in my sewing box. Her black cast-iron griddle cooks my grilled cheese sandwiches. Her delicate gold watch with the narrow black cloth wristband, her Liberty half-dollar necklace from the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair, and her silver charm bracelet crowded with mementos from her life all keep my jewelry company. Her pictures are on my wall and in my photo albums. Her mother Nellie’s round English deco mirror hangs in my bedroom, reflecting all three of our images in my face. I also have her metal meat grinder (the one she ran my right index finger through when I was not yet two), stored in an old workman’s aluminum lunch pail, way up high on a shelf in my garage where it can’t get me. My sisters and brother must have thought these things important to me, that I should have them. They are. I’m pleased when I use or look at or wear them. They remind me of Mother, remind me of some good parts of her. And they remind me of what I missed.

For years I didn’t think about her at all. For a while I thought about her more than I needed to. Now, when I think of her, it’s easier, and it feels like we can dance.

October 3, 2015

Half a Tuna on Toast

Sprouse Reitz, 1644 Haight Street

1954 • San Francisco, California

“Sprouse as in house, Reitz as in right” was the slogan used by my father’s employer. Nobody said “Reitz” right; they rhymed it with “Pete’s” so I corrected them.

Taking the Greyhound to spend an occasional weekend with Daddy, he’d take me to work with him; while he manned the register at the front, I stayed in his office in the back. Sitting in his big oak swivel chair, I played with his ten-key adding machine and made houses from the rolls of white adding machine tape. He checked on me during his break and then at noon we ate our lunches at his desk. Every day he sipped a half-sized can of room temperature beer with his sandwich. It settled his stomach, balancing the rolls of Tums he chewed to counteract the Empirin Compound he took for headaches. On the days we didn’t pack bologna or salami sandwiches, we ate at the Glen Ellen Diner across the street. I loved going there. We slipped into a booth and Daddy ordered from the menu while I flipped through the built-in tabletop jukebox, reading off the latest hits. I requested my favorites, Hernando’s Hideaway and Mr. Sandman, and Daddy ordered the special for us, half a tuna on toast with a cup of clam chowder.

I loved visiting my father. We played Old Maid and gin rummy. He sang Three Little Fishies or German songs he remembered from his childhood, told me corny riddles, recited limericks, and magically pulled quarters from behind my ear. I liked playing Five Little Piggies, even though I was six and a little old for baby stuff. He gave me butterfly kisses by fluttering his eyelashes on my cheeks. And he did this thing with his lip: just as I turned my head to look away, he’d touch his lower lip to the tip of his nose, which is impossible unless you have an under-slung jaw and a nose like my dad. Or he’d click his bottom dentures out of his mouth and catch them with his tongue the split second before they flew away. Laughing, clapping my hands, I’d beg him to do it again because I’d just barely catch him out of the corner of my eye the first time.

After Sunday mass we walked hand-in-hand through the big glass Arboretum and the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park. We roamed Fishermen’s Wharf and had a Shrimp Louie and a hunk of sourdough. We strolled by store windows filled with souvenir tee shirts, Japanese tea sets, and lacquered Chinese boxes; he bought me a red one for Christmas one year. Sometimes we went to Fleishhacker Zoo and watched the monkeys on Monkey Island and fed the seals three smelly pieces of mackerel from a little white wax paper bag that cost a quarter. We ate pink popcorn and hot dogs with mustard and got vanilla ice cream cups with a quarter-moon of raspberry sherbet. I saved my wooden ice cream paddle; I liked to chew on it. Then we rode the carousel; as the lights flashed, bells chimed, and music blared, we sprinted for our seats. I preferred the ostriches: their backs weren’t so high off the ground. When I grew more confident, I rode the horses. I was too small for the ring grab, with its high iron rings the size of half dollars, just beyond my reach. If you snagged a brass one, you got a free ride, but your horse had to be at the top of its ride so you could reach it. Daddy stretched me sideways over the horse and hooked his finger over mine. We stretched out as far as we could and snatched it together as our horse flew by. Even though I was supposed to turn it back in, I kept one as a souvenir. I still have it.

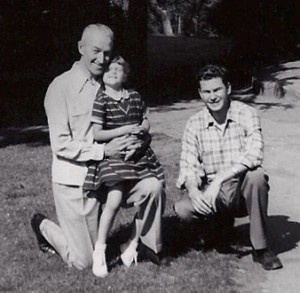

Dad, Cathy, Larry, 1954 San Jose State

A couple of times we drove to San Jose to visit Larry where he was going to college and have picnics on the campus, with Daddy lying on the grass next to me and letting me wear his hat, telling me stories, tickling me and making me laugh. We went to the movies and saw the Song of the South, Snow White, and Bambi. I always cried in the movies, and don’t know that I ever recovered when Bambi’s mother died.

September 28, 2015

False Hope

November 1968 • La Habra, California

Mom and her Hillman, circa 1962

When my mother died, her life was packed in a small 1954 two-door, light blue white-topped convertible Hillman Minx, now parked in my sister’s driveway. The front seat held her clothes, small feather pillow, and jewelry; the back seat, her black and gold Singer, button collection, and sewing box. In the trunk were her pots and pans and meat grinder, her mother’s round deco mirror, and her family pictures. On top was her blue Samsonite overnight case, filled with bottles of pills that through the years kept watch over her like toy plastic soldiers with white caps, standing sentry on her dresser top. She carried with her a pharmacy: diet, pain, and sleeping pills; pills for her stomach, her anxiety and depression, and pills for everything else in the world that ailed her. Over the years Mom lived on green tea, rare steak, and pills: Benzedrine and Dexedrine. Nembutal, Tuinal and Seconal. Librium and Valium. Darvon. Thorazine and Stelazine. There were over-the-counters: aspirin, Excedrin, and a large, cobalt blue bottle of Bromo-Seltzer. My mother the cosmic omnivore and pharmaceutical zombie.

My mother, Noreen Clemens

The five of us spread Mom’s possessions on Carleen’s living room rug. Larry chose her silver charm bracelet and costume jewelry. Carleen took her sewing scissors and white half-slip. Betty picked the sewing machine, the round mirror, the Dutch oven, the cast iron pans, and the meat grinder. Claudia ended up with her full-length white evening coat and a handful of jewelry. I wanted her Liberty head necklace and her delicate Gruen wristwatch. We split up Mom’s family pictures, and then we flushed thousands of white pills and colored capsules down the toilet and unceremoniously tossed the stack of receipts that accompanied them. Her button collection and clothes we gave to the Salvation Army. Nobody remembers what we did with her small blue Hillman, though for months it sat in the driveway in La Habra along with the long abandoned Mercury, keeping it company.

Memory Garden Cemetery, Brea

There was no funeral, no flowers or friends; only her children came to witness her ashes being ensconced in a small cemetery in Brea, and that was only because our brother made us. Mother is now secured behind a small bronze door at the top of a mausoleum wall, high enough where she could no longer get me. Standing there, the five of us were filled with a mixture of relief, regret, remorse, and resentment; we said good-by and left—and except for my brother Larry—never went back. It didn’t matter any more. I thought none of it mattered any more.

If you’d asked me, I’d have said I’d given up years ago of her ever wanting me, of listening to or seeing me. But secretly I’d always harbored hope that my mother loved me, my false hope better than no hope at all.

September 25, 2015

Catholics, Cows, and a Clunker

Carl Clemens

When the wheels needed to be changed or the axles greased, Dad—not yet a man—lifted the more than 200-pound hay wagon with his back, raised it higher with his arms and held it steady while his older brother Aloysius, or Louie as the family called him, slipped the new wheel on the axle. That’s how strong my father was.

Born into a Minnesota farming family in 1905, Carl, my father, was the middle child of thirteen, all born between 1898 and 1914. A set of twins died at three days, a sister at four months. All were born in the same two-story stone house on the family farm. Four generations of Clemens grew up in those stone walls, surrounded by cows, company, and Catholicism. You weren’t considered a good Catholic unless you had a child at least every other year.

Clemens family farm, three generations, fall of 1912

Working in the fields one burning afternoon alongside his mother, he observed her intently. Stooped and worn, gray strands of hair straggled from her bun, dampened by sweat escaping her forehead, he saw how tired and weathered she looked. Her back bent shocking wheat, she took the sheaves of grain, tied them, then carefully stood the bundles upright in the field for drying. He decided right then and there that wasn’t going to happen to him, knowing if he stayed he’d sink into her footprints forever, tied to endless seasons of planting corn, milking cows, and disking hay.

When he was fifteen, Carl pooled his money with three friends, Paul Adamson, Johnny Mohlke, and Tone Conway (Michael Anthony Conway was his given name; later in life he became One-Eyed Mike). They bought an early 1920s touring car, an open-topped green Chevrolet with isinglass curtains. It was clunker that cost them $10 apiece; it was all they could afford. When they first got it, Johnny, a fiery redhead who didn’t weigh more than 150 pounds and never sat still for more than ten seconds, was the only one who could drive, and he drove like a maniac. He was the drinker of the group, sometimes pouring it down for a week. Tone and Paul drank heavily too, but not like Johnny. Carl, the oldest of the four, was the only one who didn’t partake; alcohol made him sick as a poisoned pup.

They often rolled the car on the country dirt and gravel roads, got out, and tipped it up on its wheels to take off again. It didn’t go over 60 miles per hour, but Johnny put the pedal to the metal, in town or out. Carl soon took over the driving. He was reputed to be a hot-rodder, accelerating with the cutout wide open. He drove fast, but he drove sober. Every time Ma heard their phone ring, one short and one long, she would shake, sure her son was in another accident and someone was hurt, or worse, dead. Nobody ever was—not seriously anyway—although Carl did come home once with his arm torn open. A scar ran the whole length of his forearm. It wasn’t something he bragged about.

St. Mary’s Farmstead (recent photo)

Ma was of the opinion boys should stay home and work on the family farm. Carl was of a different opinion. Trying to please his mother was about as easy as jumping over his own knees, and one morning he disappeared and didn’t come back. Ma was hurt; she worried about him constantly and prayed he’d call or write. No matter to Carl; he was tired of being told what to do. He didn’t go far, just off to his uncle Frank Nigon’s place east of Rochester to work, then in 1923, he and Tone got a job at St. Mary’s Hospital Dairy Farmstead, milking cows to supply pasteurized milk to St. Mary’s Hospital.

When he was eighteen, he and Tone decided to head west for work and adventure. They called up Johnny and Paul, and the four friends each packed a suitcase. They hopped into their Chevy and drank their way to Seattle while Carl drove. They dropped Carl off, turned around, and drove back. They knew they were farmers, and that their ties were in Minnesota. Carl remained in Seattle, first getting a job in the lumber mills, and then for a dairy delivering milk. He ended up in California where there was better work and better weather. He gained employment with Frederickson & Watson Construction Company, traveling from job to job; in those days, to find work, unless you were a farmer, you had to go were the jobs were. My father, the only man in the family to leave the farming life, was considered the smart one.

September 17, 2015

It’s All About Me

Life… it’s all about me—me, and what I want. No one wants to admit that. Why? Because we don’t want anyone to think we’re self-centered.

Google synonyms for self-centered. It has four pages of like words for those of us who are all about ourselves. Yet, we abhor others who are like that, you know, egocentric, pompous, highfalutin, inconsiderate, conceited, selfish, thankless, vainglorious, ungrateful, egotistical, self-serving. But if I spot those things in others, the things I don’t like about other people, the behaviors that irritate me, the ways I don’t want to show up, I realized I’ve got those things in me. Not only do I have them in me, I have them outside my circle because I don’t want to be seen that way. People might not like me. Acting like that won’t make me look good. Being that way is not nice. It’s a slippery slope. It’s slightly less slippery if you recognize your disowned parts, your shadows, at least then you can dance with them a bit.

Some go: “I’m not all about me, I’m all about you,” or “I’m all about this,” or “I’m all about that.” Yeah, right. The rock stars in the news these days who are not all about themselves are Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, but they’re a tad more evolved than most, in my opinion anyway, and goodness knows I’ve plenty of opinions.

I could write a book about me, or maybe blog about me. Actually, I already have. I’m perfectly clear I’m all about me. A little tweaked about it actually, probably because my mother wasn’t all about me. She was all about her. The irony of it though was that her narcissism and self-centeredness had nothing to do with me; her relationship with me wasn’t about me at all, not me, or my value. My timing was bad and she was simply done having children by the time I came along, though as far as I can tell, my siblings didn’t fare well with her either. She was struggling to keep her own life together and I played a minor role in her movie, more like a walk-on part actually. Peter, my acupuncturist, once told me that I chose my mother; I about fell off the table, laughing, “Oh no, no, no, no, no. No, I was in the wrong line; I’m certain I picked the wrong one!”

But enough about me. The stories I write are about all of us; we are bound by our humanity and we all have “stuff.” People like my writing (some have even told me, so it must be true) because they get another slant on this crazy thing called life, or they see something about themselves, about their own upbringing and families. My reflections are not so much about ME, but about WE. However, as all roads lead to home, maybe they are all about me.

It’s All About ME

Life… it’s all about me—me, and what I want. No one wants to admit that. Why? Because we don’t want anyone to think we’re self-centered.

Google www.thesaurus.com/browse/self-centered. It has FOUR PAGES of synonyms for those of us who are all about themselves. Yet, we abhor others who are like that—you know—egocentric, pompous, highfalutin, inconsiderate, conceited, selfish, thankless, vainglorious, ungrateful, egotistical, self-serving. But if I spot those things in others—the things I don’t like about other people, the behaviors that irritate me, the ways I don’t want to show up—I’ve got those things IN ME, and not only do I have them in me, I have them outside my circle because I don’t want to be seen that way. People might not like me. Acting like that won’t make me look good. Being that way is not nice. It’s a slippery slope. It’s slightly less slippery if you recognize your shadows; then you can dance with them a bit.

Some go: “I’m not all about me, I’m all about you,” or “I’m all about this,” or “I’m all about that.” Yeah, right. The stars in the news these days who are not all about themselves are Pope Francis and the Dalai Lama, but they’re a tad more evolved than most, in my opinion anyway, and goodness knows I’ve plenty of opinions.

I could write a book about me, or maybe blog about me. Actually, I already did. I’m perfectly clear I’m all about me. A little tweaked about it actually, probably because my mother wasn’t all about me. She was all about her. The irony of it though was that her narcissism and self-centeredness had nothing to do with me; her relationship with me wasn’t about me at all, not me, or my value. My timing was bad and she was simply done having children by the time I came along, though as far as I can tell, my siblings didn’t fare well with her either. She was struggling to keep her own life together and I played a minor role in her movie, more like a walk-on part actually. My acupuncturist once told me that I chose my mother; I about fell off the table, laughing, “Oh no, no, no, no, no. No, I was in the wrong line; I’m certain I picked the wrong one!”

But enough about me. The stories I write are about all of us; we are bound by our humanity and we all have “stuff.” People like my writing (some have even told me so, so it must be true) because they get another slant on this crazy thing called life, or they see something about themselves, their own upbringing and families in the stories. The reflections are not so much about ME, but about WE. However, as all roads lead to home, maybe they are all about me.

September 11, 2015

If It’s Not One Thing… It’s Your Mother

Audio: click arrow to play ~

http://sevenau.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/4-If-Its-Not-One-Thing-Its-Your-Mother.mp3

We think our life is someone else’s fault. As victims of circumstance, blown by fate and buffeted by winds, we need somebody to pin it on. Our father often takes the heat, but usually it’s our mother. We also blame the schools, the government, and the past. If it has anything to do with missing homework, we blame the dog. If we’re dyslexic, we blame God—unless of course you were raised in a happy-clappy church. I wasn’t. I was raised Roman Catholic, the religion of rules and reservations, especially about sex.

Cathy Clemens, 1949

Once we find someone to take the fall, we squander our life living in if only. We waste our energy wandering along the yellow brick road and wailing: the sky is falling, the sky is falling! Bonding with doom and gloom, grist and gossip, bad news, bad skin, and bad hair, we become skeptical and cynical, residing in complacency and complaint. This all started when we were small children and separated from the soul with which we were born, when our spirit was quashed. Oh to be able to reconnect with that sweet soul we left behind; if we could, perhaps the world, our small piece of it anyway, would make more sense. We could be ourselves again.

It only takes a slight course adjustment to reach a different destination, and I’m two-stepping on a repaved path. I can’t change my history, genetic blueprint, or my family, but I can change how I choose to live my life. So I practice breathing, and living inside my body. I practice gratitude and generosity. I practice patience. The rest of the time I just try not to holler at everyone.

Catherine (Clemens) Sevenau, 2013

In the journeys of my life—from wondering how I got here to knowing where I am, from falling down the rabbit hole to dancing with the stars, from having my mother show up in my stomach, bones, and dreams to writing a book about her so as to meet her, and meeting myself instead—I find I’m not about the pearl, but about the sand that made me. Mine was not the childhood I wished for, but who am I to question grace?

September 4, 2015

Gold Country, Sonora

1943: Sonora, Tuolumne County, California ~

Emerging into view from the crown of Highway 49 and a mile from end to end, the town of Sonora is tucked into the foothills and ravines of the Sierra Nevada—the gateway to California’s gold mining region. In the mid 1800s it was a whirlwind of change, a booming and often lawless community, a geographical crossroads where people from all over the world converged. In its frenetic gold rush heyday, the sounds of miners blasting the hillsides and dynamiting the treasure-filled rivers and creeks echoed throughout the area, changing Sonora’s natural landscape and waterways forever.

During World War II, most of the men not fighting for our country had left for wartime jobs in the bigger cities. My father was exempt from the draft, being almost forty and with four children, so he was one of the few men still in town. Throughout the war years Sonora shifted into idle. Most of the stores were vacant, and because of gas rationing there were no tourists.

When the ice companies closed, due to the advent of electric refrigerators, my father got a job managing a Sprouse Reitz. Given the choice of running a store in Sonoma (a sleepy hamlet forty-some miles north of San Francisco) or in the town of Sonora, he chose the latter, hoping there would be more business opportunity.

When our family moved there in 1943, Sonora had no stoplights, one taxi, two theaters, a three-lane bowling alley, four newspapers, five cemeteries, a six-block-long main street, seven churches, and eight taverns. Cigar stores, barbershops, ice cream parlors, and clothing shops lined Washington Street, the hub of this small town. The dry hot summers went on for years, a silver quarter was a lot of money, and people did what was expected. Sonora had passed its rough and tumble heyday, settling into a cocoon of open windows and unlocked doors.

Our family lived at 104 Green Street in the old LePape house owned by the Segerstrom family, who also owned the historic Sonora Inn and Kelley’s Central Motors and Garage. It was an old white, two-story residence in the center of town that rented for $35 a month, and it’s where I would be born five years hence.

Writings~Rambles~Rhymes

- Catherine Sevenau's profile

- 6 followers