Alan Paul's Blog, page 25

September 29, 2015

Nicki Bluhm & the Gramblers: Into the ‘Wild’

I wrote this article for Relix magazine. I like Nicki Bluhm and the Gramblers quite a bit and Loved Wild Lost is a terrific album.

“Ultimately, I’m doing this for myself,” Nicki Bluhm explains shortly before the release of her second album with The Gramblers, Loved Wild Lost, “because I love what I’m doing. I’m grateful that we have an audience and being liked is important, but you have to like yourself, and playing the music you like is essential, even if it’s not hitting people over the head.”

This quiet confidence took Bluhm a while to achieve. She was a closet singer for many years before she took center stage with Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers, a collective that also features her husband Tim Bluhm, childhood friend Deren Ney, ALO bassist Steve Adams, guitarist Dave Mulligan and drummer Mike Curry. Growing up, Nicki often belted out songs in the shower, doing her best to emulate the likes of Whitney Houston. In high school, in the East Bay’s Lafayette, Calif., she would occasionally call her old friend Ney, whom she’d known since first grade, and ask him to play some guitar for her to sing over.

“She nudged me to play a few times, but it was always a secretive thing,” Ney reclls. “She was shy about it because she loved singing but didn’t have that thing to perform. She wanted to know what it was like to sit and sing over an acoustic, and I thought she was fantastic from the start.”

Ney was already well known in Lafayette as the hippie kid with a guitar and a deep well of songs.

“Deren was like a jukebox,” says Nicki, who is tall, thin, and has a retro, ‘70s aura that feels in line with The Gramblers’ music. “He could play anything I got in my head and I would get drunk and want to sing with him.”

After college, Nicki became a teacher and worked for a while on a ranch in Southern California taking care of eight horses. She moved back to the Bay Area and got a job as a naturalist for the City of San Francisco School District, teaching outdoor education. “We worked with a lot of underprivileged schools throughout the district and taught kids about nature and the watershed and native plants,” she says. “I was always outside and I loved it.”

By then, she had become friends with her now-husband Tim. (She jokes that every boyfriend she’s ever had was a fan of his band, The Mother Hips.) At a record release after-party, she jumped up and sang harmony with him on songs she knew intimately well, and had already worked out her parts by singing along to recordings countless times. Tim was amazed.

“I heard something really pleasing and unique right away,” he says. “I wasn’t necessarily thinking that she would want to pursue it as a career, and I didn’t know if she had the other skills necessary to do so, but I knew her voice had this really cool, unique thing that people would want to hear. I was certain about that immediately. There’s just something that comes out of Nicki when she sings. It’s her personality and just a physical quality in her voice that’s really nice to hear and that pulls people in.”

Tim’s immediate encouragement was huge for Nicki. It was, in fact, perhaps the first time that she began to accept that maybe she had something special; maybe her singing was destined to be heard by people other than friends, housemates and lucky late-night partygoers.

“His encouragement was a powerful moment for me,” she says. “It was finally someone I respected and trusted telling me I was good. It’s not your mom saying, ‘Oh, honey, you have a great voice.’ Tim is, 100 percent, the reason I’m doing this.”

Still, her transition from private to public singing wasn’t simple. It was, she says in a word, “awkward.”

“I showed up at my first open mic night. My guitar didn’t have a pickup, and I didn’t even know what one was when the guy handed me a cord to plug in,” she recalls. “I was really intimidated and forgot every word to every song I’ve ever known.” Soon after, Tim took her to buy a guitar with a pickup and as she began to gain confidence, he invited her to open some shows he was doing with Jackie Greene in 2006. She found the experience excruciating.

“I didn’t like my guitar playing, and I wanted more texture,” she recalls. “I wanted a lead instrument and thought about the guitar players I knew, and Deren was the obvious guy to call.”

At the time, her old friend Ney was living in Los Angeles, working temp jobs and trying to be a screenwriter.

“After seeing some of my favorite bands struggle to survive— including The Mother Hips—I decided I loved music too much to ruin it by trying to make it a career, so I was chasing screen- writing, another fool’s errand,” Ney recalls with a laugh. “I had not been playing and actually had to borrow an amp for those first shows.” Ney has been by her side ever since, developing into a secret weapon of sorts, playing snappy, pungent guitar lines that accentuate and drive the music without overwhelming the songs. He’s also developed into the band’s third songwriter, after Tim and Nicki.

Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers’ career took a serious turn for the better when they stumbled into making a series of viral YouTube videos. Dubbed the “Van Sessions,” the clips simply featured the group playing and singing some of their favorite covers while driving from gig to gig. They captured them on an iPhone. It began when bassist Adams brought a ukulele on tour. Their version of Hall and Oates’ “I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)” was the video that took off, logging over a million views and essentially launching their career.

The Van Sessions, “I Can’t Go For That”

“As stoked as I am about the ‘Van Sessions’ and all they’ve done for us, I definitely hope it’s a chapter in our career and I don’t have to talk about it for the rest of our lives,” says Nicki. “It was a really cool thing that happened. I’m grateful and they’re very fun, and I think people chose to watch and share them because they’re nostalgic. We chose songs that meant a lot to us and that our parents played when we were kids, and it’s reached a lot of age groups and brought families together, which is really cool. And I think people responded because they thought it was real—real instruments, real people singing, captured in lo-fi. But we’ve always been forward-thinking and want to promote our original music, which really is what’s keeping us going.”

Nicki Bluhm & the Gramblers logged thousands of miles between the recording and release of their self-titled 2013 album and their new Loved Wild Lost. “We toured for pretty much two years solid,” says Nicki. “All those hours together traveling and on- stage definitely had a big impact on the music we wrote and on our relationships. As a band, you go through stages and you learn. You just grow. You become more confident and smarter when you have a few hundred shows under your belt.”

That deeper sense of self and confidence is evident throughout Loved Wild Lost. It is the first album that the group recorded from a position of some strength, and the first that is really a full-band album, with all six members contributing to the writing and arrangements.

“We are more methodical and much more organized in the execution of this album than we have been in the past,” she adds. “We spent 10 days doing pre-production at our friend’s little ranch in Atascadero, Calif.—just playing music together and working stuff out in a very relaxed, mellow atmosphere with horses, cats and dogs, and a great friend cooking us homemade Mexican meals.”

One major impact of this pre-production time was that everyone in the band had an opportunity to craft their parts, rather than listening to basic tracks and ironing things out in the studio as on past efforts.

“We all had to kind of look each other in the eye and present our parts, and that tends to lead to being more exacting and thoughtful,” Ney recalls. “And when we entered the studio, we knew what we were gonna do. It had never been like that before. We always cobbled it together. This was a lot more intentional.”

Loved Wild Lost is actually Bluhm’s fifth recording; the first two were issued under her name only and she also released a duet record with her husband. “We’re all together all the time and it just felt right to call it Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers,” she says. “It was such an organic process to get there.”

Still, while this is the second album billed collectively to Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers, Ney says it felt a lot like The Gramblers’ first real band recording: “We’ve all been some- what involved in all of her records, but this time, we were all coming in as equals, as members of the band.”

A large part of that process was working with an outside producer for the first time. Nicki’s husband, guitarist, keyboardist and musical director Tim produced her first three efforts. This time, they brought in Brian Deck (Iron & Wine, Modest Mouse, Josh Ritter).

“It was hard for me to give up control at first,” Tim admits. “But I relaxed and began loving it as soon as I saw how Brian operated and what he brought us. I didn’t ever have to be the bad guy and it was really nice for me to just be a member of the band. It’s hard to be both bandmate and producer.”

He pauses to reflect for a moment before adding, “There are actually parallels to being in a band with someone you’re married to, which presents similar challenges.”

“Tim got to just be a musician and that led to things opening up and all of us contributing more,” Ney says. “As we put the songs together, it was our job to throw out what we thought would be good. We were sort of creating it together. We had to play our parts in front of everybody and take ownership. Everybody had the freedom to create what they wanted, but we had to do it in a way that fit together and made the songs better. There was freedom, but there wasn’t unchecked freedom.”

Everyone agrees that by the time the band entered Panoramic House Studios in Stinson Beach, Calif., they had the songs down and could execute the recording with great efficiency. The result is an album that’s laid-back but urgent, and probably a little more subtle and country/roots-tinged than previous efforts, which had a bit more R&B swagger. Nicki says that the more under- stated approach was especially intentional and was an almost-contrary reaction to all of the live performances, where there can be a push to go big.

“You want to get a reaction from the crowd, so you play these big songs to get people stoked and keep the energy up,” she says. “It’s pretty common to overplay in that excitement and I think what we’ve tried to do with this record is really be selective with the parts. We kind of approached the recording musically that way, too: ‘Let’s be as sparse as possible. There’s no need for all of us to play all the time.’ We were more discerning and thoughtful about what we’re playing. Let’s trim the fat. Don’t play the notes you don’t need.’ And I’m really excited for that to carry over to our live show.”

Nicki Bluhm & the Gramblers: Into the âWildâ

I wrote this article for Relix magazine.  I like Nicki Bluhm and the Gramblers quite a bit  and Loved Wild Lost is a terrific album.

âUltimately, Iâm doing this for myself,â Nicki Bluhm explains shortly before the release of her second album with The Gramblers, Loved Wild Lost, âbecause I love what Iâm doing. Iâm grateful that we have an audience and being liked is important, but you have to like yourself, and playing the music you like is essential, even if itâs not hitting people over the head.â

This quiet confidence took Bluhm a while to achieve. She was a closet singer for many years before she took center stage with Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers, a collective that also features her husband Tim Bluhm, childhood friend Deren Ney, ALO bassist Steve Adams, guitarist Dave Mulligan and drummer Mike Curry. Growing up, Nicki often belted out songs in the shower, doing her best to emulate the likes of Whitney Houston. In high school, in the East Bayâs Lafayette, Calif., she would occasionally call her old friend Ney, whom sheâd known since first grade, and ask him to play some guitar for her to sing over.

âShe nudged me to play a few times, but it was always a secretive thing,â Ney reclls. âShe was shy about it because she loved singing but didnât have that thing to perform. She wanted to know what it was like to sit and sing over an acoustic, and I thought she was fantastic from the start.â

Ney was already well known in Lafayette as the hippie kid with a guitar and a deep well of songs.

âDeren was like a jukebox,â says Nicki, who is tall, thin, and has a retro, â70s aura that feels in line with The Gramblersâ music. âHe could play anything I got in my head and I would get drunk and want to sing with him.â

After college, Nicki became a teacher and worked for a while on a ranch in Southern California taking care of eight horses. She moved back to the Bay Area and got a job as a naturalist for the City of San Francisco School District, teaching outdoor education. âWe worked with a lot of underprivileged schools throughout the district and taught kids about nature and the watershed and native plants,â she says. âI was always outside and I loved it.â

By then, she had become friends with her now-husband Tim. (She jokes that every boyfriend sheâs ever had was a fan of his band, The Mother Hips.) At a record release after-party, she jumped up and sang harmony with him on songs she knew intimately well, and had already worked out her parts by singing along to recordings countless times. Tim was amazed.

âI heard something really pleasing and unique right away,â he says. âI wasnât necessarily thinking that she would want to pursue it as a career, and I didnât know if she had the other skills necessary to do so, but I knew her voice had this really cool, unique thing that people would want to hear. I was certain about that immediately. Thereâs just something that comes out of Nicki when she sings. Itâs her personality and just a physical quality in her voice thatâs really nice to hear and that pulls people in.â

Timâs immediate encouragement was huge for Nicki. It was, in fact, perhaps the first time that she began to accept that maybe she had something special; maybe her singing was destined to be heard by people other than friends, housemates and lucky late-night partygoers.

âHis encouragement was a powerful moment for me,â she says. âIt was finally someone I respected and trusted telling me I was good. Itâs not your mom saying, âOh, honey, you have a great voice.â Tim is, 100 percent, the reason Iâm doing this.â

Still, her transition from private to public singing wasnât simple. It was, she says in a word, âawkward.â

âI showed up at my first open mic night. My guitar didnât have a pickup, and I didnât even know what one was when the guy handed me a cord to plug in,â she recalls. âI was really intimidated and forgot every word to every song Iâve ever known.â Soon after, Tim took her to buy a guitar with a pickup and as she began to gain confidence, he invited her to open some shows he was doing with Jackie Greene in 2006. She found the experience excruciating.

âI didnât like my guitar playing, and I wanted more texture,â she recalls. âI wanted a lead instrument and thought about the guitar players I knew, and Deren was the obvious guy to call.â

At the time, her old friend Ney was living in Los Angeles, working temp jobs and trying to be a screenwriter.

âAfter seeing some of my favorite bands struggle to surviveâ including The Mother HipsâI decided I loved music too much to ruin it by trying to make it a career, so I was chasing screen- writing, another foolâs errand,â Ney recalls with a laugh. âI had not been playing and actually had to borrow an amp for those first shows.â Ney has been by her side ever since, developing into a secret weapon of sorts, playing snappy, pungent guitar lines that accentuate and drive the music without overwhelming the songs. Heâs also developed into the bandâs third songwriter, after Tim and Nicki.

Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblersâ career took a serious turn for the better when they stumbled into making a series of viral YouTube videos. Dubbed the âVan Sessions,â the clips simply featured the group playing and singing some of their favorite covers while driving from gig to gig. They captured them on an iPhone. It began when bassist Adams brought a ukulele on tour. Their version of Hall and Oatesâ âI Canât Go for That (No Can Do)â was the video that took off, logging over a million views and essentially launching their career.

The Van Sessions, “I Can’t Go For That”

âAs stoked as I am about the âVan Sessionsâ and all theyâve done for us, I definitely hope itâs a chapter in our career and I donât have to talk about it for the rest of our lives,â says Nicki. âIt was a really cool thing that happened. Iâm grateful and theyâre very fun, and I think people chose to watch and share them because theyâre nostalgic. We chose songs that meant a lot to us and that our parents played when we were kids, and itâs reached a lot of age groups and brought families together, which is really cool. And I think people responded because they thought it was realâreal instruments, real people singing, captured in lo-fi. But weâve always been forward-thinking and want to promote our original music, which really is whatâs keeping us going.â

Nicki Bluhm & the Gramblers logged thousands of miles between the recording and release of their self-titled 2013 album and their new Loved Wild Lost. âWe toured for pretty much two years solid,â says Nicki. âAll those hours together traveling and on- stage definitely had a big impact on the music we wrote and on our relationships. As a band, you go through stages and you learn. You just grow. You become more confident and smarter when you have a few hundred shows under your belt.â

That deeper sense of self and confidence is evident throughout Loved Wild Lost. It is the first album that the group recorded from a position of some strength, and the first that is really a full-band album, with all six members contributing to the writing and arrangements.

âWe are more methodical and much more organized in the execution of this album than we have been in the past,â she adds. âWe spent 10 days doing pre-production at our friendâs little ranch in Atascadero, Calif.âjust playing music together and working stuff out in a very relaxed, mellow atmosphere with horses, cats and dogs, and a great friend cooking us homemade Mexican meals.â

One major impact of this pre-production time was that everyone in the band had an opportunity to craft their parts, rather than listening to basic tracks and ironing things out in the studio as on past efforts.

âWe all had to kind of look each other in the eye and present our parts, and that tends to lead to being more exacting and thoughtful,â Ney recalls. âAnd when we entered the studio, we knew what we were gonna do. It had never been like that before. We always cobbled it together. This was a lot more intentional.â

Loved Wild Lost is actually Bluhm’s fifth recording; the first two were issued under her name only and she also released a duet record with her husband. âWeâre all together all the time and it just felt right to call it Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers,â she says. âIt was such an organic process to get there.â

Still, while this is the second album billed collectively to Nicki Bluhm & The Gramblers, Ney says it felt a lot like The Gramblersâ first real band recording: âWeâve all been some- what involved in all of her records, but this time, we were all coming in as equals, as members of the band.â

A large part of that process was working with an outside producer for the first time. Nickiâs husband, guitarist, keyboardist and musical director Tim produced her first three efforts. This time, they brought in Brian Deck (Iron & Wine, Modest Mouse, Josh Ritter).

âIt was hard for me to give up control at first,â Tim admits. âBut I relaxed and began loving it as soon as I saw how Brian operated and what he brought us. I didnât ever have to be the bad guy and it was really nice for me to just be a member of the band. Itâs hard to be both bandmate and producer.â

He pauses to reflect for a moment before adding, âThere are actually parallels to being in a band with someone youâre married to, which presents similar challenges.â

âTim got to just be a musician and that led to things opening up and all of us contributing more,â Ney says. âAs we put the songs together, it was our job to throw out what we thought would be good. We were sort of creating it together. We had to play our parts in front of everybody and take ownership. Everybody had the freedom to create what they wanted, but we had to do it in a way that fit together and made the songs better. There was freedom, but there wasnât unchecked freedom.â

Everyone agrees that by the time the band entered Panoramic House Studios in Stinson Beach, Calif., they had the songs down and could execute the recording with great efficiency. The result is an album thatâs laid-back but urgent, and probably a little more subtle and country/roots-tinged than previous efforts, which had a bit more R&B swagger. Nicki says that the more under- stated approach was especially intentional and was an almost-contrary reaction to all of the live performances, where there can be a push to go big.

âYou want to get a reaction from the crowd, so you play these big songs to get people stoked and keep the energy up,â she says. âItâs pretty common to overplay in that excitement and I think what weâve tried to do with this record is really be selective with the parts. We kind of approached the recording musically that way, too: âLetâs be as sparse as possible. Thereâs no need for all of us to play all the time.â We were more discerning and thoughtful about what weâre playing. Letâs trim the fat. Donât play the notes you donât need.â And Iâm really excited for that to carry over to our live show.â

September 28, 2015

Rebecca’s speech at The Michigan Daily 125th Anniversary gala

While waiting to receive a copy of the video, I’ve posted a written copy of Rebecca’s speech from the Michigan Daily’s 125th Anniversary dinner. I will post the video as soon as I have it. It was an honor to help Becky craft this speech.

While waiting to receive a copy of the video, I’ve posted a written copy of Rebecca’s speech from the Michigan Daily’s 125th Anniversary dinner. I will post the video as soon as I have it. It was an honor to help Becky craft this speech.

The night before the dinner we attended the book launch for In the Name of Editorial Freedom: 125 Years at the Michigan Daily and enjoyed meeting other contributors from different Daily periods. One of them was John Papanek. He somehow communicated to Becky that his friend and Daily colleague Bill Alterman had been planning to attend but was too sick with cancer. He was Skyping with him at that very moment and she had a brief but impactful chat with him. It was enough to make her determined to share a great story from him in the speech. You will see it below.

John, as a loyal friend, was streaming the whole evening to a bed-ridden Bill in Washington DC and thought that he would be pleased to be mentioned. Everyone in the room cheered and sent him best wishes. He heard it all. And, rather unbelievably, he died the next day. I don’t what else to say except all of us Daily alumni are a family and it was kismet for Becky to meet John and talk to Bill and include his story. And that we send deepest condolences and most sincere wishes for healing and peace to all of his loved ones – blood-related and otherwise.

The speech:

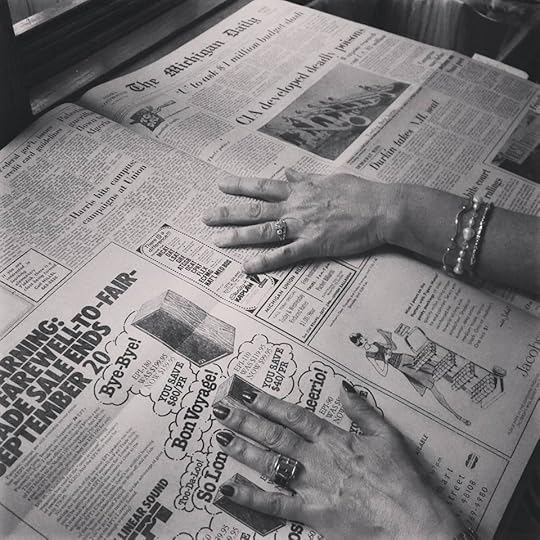

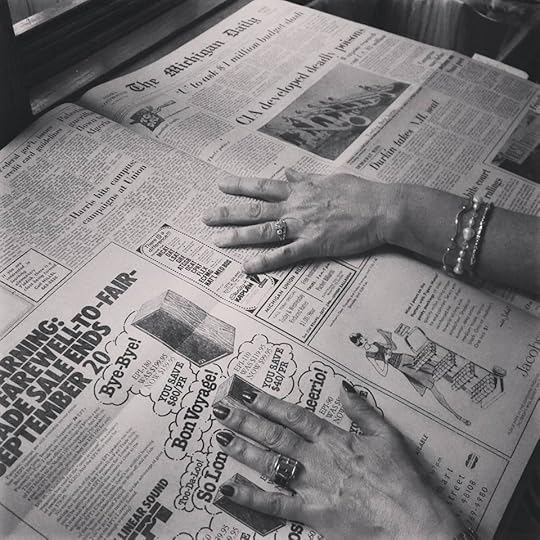

Last minute run through at 420 Maynard.

Thanks very much, Neal – and thank you to everyone who made tonight possible.

I’m very honored to be here.

I worked at the Daily from 1985-89 and was Editor in Chief my final year. It’s hard for me to believe that it was 26 years ago because so much from my time there remains so vivid and relevant to my life.

I’m now the deputy editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal. In my role, I meet a wide range of people, and they often ask about my journalism education. When I say that I’ve never taken a single journalism class in my life, most people are shocked. They can’t understand how I trained for a career in journalism without ever studying the topic. It comes down to three words: The. Michigan, Daily.

Each of us walked into 420 Maynard as one person and walked out as another. Each of us had our 3 or 4-year window at the Daily, which felt completely unique and special. And each of us was probably too young to fully appreciate that we were in fact part of a long, proud and rather remarkable history of editorial freedom. It was 100 years when I was here. Maybe it was 60, 80, or 120 for you. We are all part of this unique and indispensible continuum.

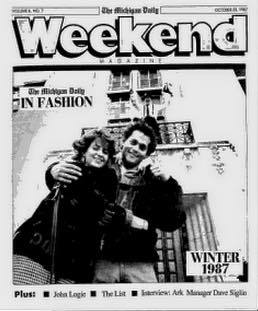

Photo by Molly Stevens

Every year new student journalists walk in and old ones walk out. No one is continuously there and yet the traditions, the pride, the lore and legends pass down from class to class, with each group adding their own twists and turns – but never losing the thread.

Of course I knew all of this and I understood it intellectually but just last night so much of it became more emotionally resonant when I picked up this book that I was proud to contribute to: In the Name of Editorial Freedom: 125 Years at the Michigan Daily. Reading through this inspiring book, I am struck not only by the great writing and how unique and personal each person’s stories are – but by the threads that tie them all together.

The sense of mission. The jump-in-the-deep-end-then-learn-to-swim attitude. The passion. The tradition. The audacity. The earnestness. The rascally iconoclasm. Over and over, we see these things repeated as one group gives way to another, for generation after generation.

As Tom Hayden notes in the book’s Foreword, from covering a Frederick Douglass speech in 1893 to uncovering a football player’s covered-up sexual assault just a few years ago, the Daily has been playing an essential news gathering role on this campus for 125 years. Students who were not playing at being adults, but actually doing very real, very important things – whether they quite knew what they were doing or not.

I can’t think of a bigger influence on the journalist – and the person – I became than the Daily, and the University of Michigan more broadly. The Daily taught me life’s most important lessons. I left 420 Maynard with most of what I needed to succeed in journalism and in life– including my husband. And I’m eternally grateful for all of it.

As I prepared to speak with you tonight, I thought long and hard about why the Daily such a valuable, enduring part of my education. I arrived at five lessons that the Daily taught me that remain central to my being.

Together, they add up to why we need to fight for the right for generations of students after us to maintain this marvelous continuum and to have the same privilege we all had: a strong, vibrant independent college paper.

Photo by Molly Stevens

1. The value of Editorial Independence and Freedom – of course!

I came to the Daily during my first week of school. Eric Mattson, Jerry Markon, Amy Mindell and Neil Chase started teaching me how to write headlines – I remember fjilt, were the counts of the letters… Georgea Kovanis assigned me my first story –about the return of paisley. I was hooked. Before I knew it, I was covering the administrative beat.

It’s impossible to imagine what the experience would have been like had there been a professor sitting at the center of the newsroom, or if the Daily had been run as part of a class. Working there gave us so much more than a textbook, a lecture and a grade. It gave us on-the-job training.

We took great pride in being independent from the University, and being a critical check on its power. And in continuing a proud tradition we were all profoundly aware of – which included not only a deep commitment to practicing great journalism but to teaching those coming behind us how to do so as well.

The editors’ commitment to and enthusiasm for stories was infectious – but they were tough on copy and didn’t mince words. And neither did anyone else on staff – as anyone who remembers the Crit Board will attest. It could be brutal to watch your work be subjected to peer review.

The examples of gutsy journalism – and editorial independence- at the Daily abound. John Papanek, one of the contributors to the Daily book, told me one yesterday that I found just incredible about his friend and former Daily Alum, Bill Alterman. In John’s words:

The game was November 6, 1971, at The Stadium in Ann Arbor. Michigan was on its way to what would have been its best years ever — a perfect 11-0 in the regular season — to be marred only by a 1-point loss to Stanford in the ’72 Rose Bowl.

Michigan was killing everybody.On Nov. 6 it was Iowa’s turn. The final score was a blistering 63-7. An absolute debacle for Iowa. Bill Alterman’s assignment was to cover the losing team, so he dutifully took his place among the 30 or so other reporters assembled for the postgame press conference with the Iowa coach, Frank Lauterbur.

The room was deathly quiet when Lauterbur stormed in and took his seat at the podium. Smoke might as well have been pouring from his ears. Not one reporter dared ask a question and a long, awkward silence ensued. Lauterbur let the discomfort build, and finally broke the ice by barking, “WELL, WE GOT THE FUCKING SHIT KICKED OUT OF US TODAY.”

The room was shocked into another, even deeper, longer hush. Lauterbur milked it, and then did it again: “In case you didn’t hear me the first time, WE … GOT … THE … FUCKING … SHIT … KICKED … OUT … OF … US … TODAY!

That pretty much ended the press conference.

Every single paper in Iowa and Michigan, and the national feeds of AP and UPI ran stories mentioning Lauterbur’s “unprintable” outburst, and of course no paper dared to print — or even euphemize — his exact words.

Every single paper except ONE.

Bill Alterman led his story with every one of Lauterbur’s words, as well as the emphatic reprise, and the Michigan Daily printed them. The Daily’s Editor-in-Chief, Bob Kraftowitz, had to sign the proof copy to indemnify the typesetters against potential liability. And that was that. No University authority was involved or informed.

Alterman’s lede became a national sensation — ending up circled in red on newsroom bulletin boards across America. John says the clip — with the lede circled – was STILL on the central bulletin board at Sports Illustrated on his first day of work there , Dec. 1973. Is that editorial freedom or what?

Our thoughts go out to Bill, who really wanted to be here tonight but is battling cancer. We wish him all the best.

Photo by Molly Stevens

2. You have to love what you do to do it well.

The Daily was a calling. We published five days a week and we governed ourselves – one person, one vote. It could be incredibly intense, but we knew we had to take it seriously because a 100 years of prideful editorial freedom was in our hands. That feeling of responsibility was weighty and made for some brutal debates and arguments. But it cemented the Daily and journalism in our hearts and minds as causes that were worth fighting for.

We sometimes took the obligation to extremes. We had perhaps an irrational view that the world might end – or we would lose our independence –if we blew a deadline or had a production problem and the Daily somehow didn’t make it out one night.

This could be a particular challenge during the summer, when a small group of us stayed to put out a weekly edition. When we were told that there was no budget for distribution so the summer paper just couldn’t get done, we scoffed and came up with a solution: we would distribute the paper ourselves. We took the finished boards up to a printer in Plymouth, watched it roll off the presses – what a thrill ! – and drove back to campus. Armed with a huge janitors’ ring of keys to every building that mattered, we dropped bundles all over campus in the wee hours. Waiting until 8 am was never considered for some reason. What could go wrong? Campus police were generally understanding when they found us stumbling around at 2 am lugging heavy loads. Their brethren on rural roads were less kind.

One early morning, we were returning to Ann Arbor with the latest edition secured in the back of Steve Gregory’s family station wagon when we saw blue lights flashing in the rearview mirror. As the police approached the car, Steve turned to us and said, “I may have a little problem with a suspended license. No matter what happens to me, make sure the Daily gets delivered.”

Everyone who cares enough to be in this room can probably relate. And yes we got the paper out that night.

Photo by Molly Stevens ( I think).

3. If you want to get to your destination, you have to know how to navigate.

Reporting and then editing stories while juggling my classes was extremely demanding. It led to many very late nights and some serious battles with my parents, who wondered not only why they kept getting notices about unpaid parking tickets from the U lot behind the paper – but why exactly I was spending so much time at that damned paper. (I’ll just say that my grades reflected some distractions).

They couldn’t have known that what they thought was the distraction was actually the real course of study. Or that learning how to juggle so much was actually teaching me an incredible amount about managing a career, a newsroom and life – lessons that resonate profoundly to this day.

I arrived at the Daily in 1984, the last year before computers arrived. I remember the typewriters, the thin, off-white paper of our first drafts – the rubber glue and scraps of paper everywhere as stories were edited – literally by stripping off one offending word or paragraph and gluing down a replacement line. Often, a finished story looked like a two year old’s art work – and that was before it was sent to a production team downstairs, with two ladies sitting at linotype machines spitting out copy to hand to the man we all initially feared: the intimidating, inimitable Lucius Doyle.

Lucius took the finished copy, ran it through a hot wax machine and attached it to the page. He worked with great precision and an Exacto knife that he clicked incessantly (blade toward you) as he peered over his bifocals and listened with impatience to the pleas of desperate editors to change a word, spelling or sentence…. Sometimes, he lost his patience, as we blew deadline and kept him late. Lucius was the adult in the room, and his authority was unquestioned. He had seen it all.

I was terrified when I first met Lucius and stayed as far away from him as long as possible. I remember my voice trembling one of the first times I had to ask for a change on the page. But I learned to talk to him – and started going out of my way just to chat with him. I made sure the changes I asked for were really necessary. And as time passed, we delighted in getting him to tell us stories about past editors, which he did with relish. Toward graduation, he allowed us to take him for a beer, which was such an honor. He loved the Daily completely, and I only wish that he could have been here tonight, as he taught me and many others so much.

Reading through the Daily book, I was inspired by so many stories. One that stands out is that of Sara Krulwich, who courageously challenged the University’s rule in 1969 that no women were allowed on the football field… “This was no joke, “ she writes.. “no women in the marching band, no women cheerleaders, no women security guards.. “

On the first day of the season, she approached the head of sports information with another Daily photographer to challenge the edict. When he told her that she wasn’t allowed, she calmly told him that she had the right to be there.. he replied that she would be escorted out.. but then the game began, she stayed, and her fellow photographer told her to start shooting.. nothing happened and she eventually received an apology.

“Ten years later, I returned to Michigan to cover a game as a staff photographer for the NYT,” she writes. “There were women cheerleaders, in the band, everyone… My first act of civil disobedience remains one of the most important days of my life. It was the moment that convinced me to make photojournalism my career.”

4. Dealing with dissent – and intensity

We governed ourselves: one person, one vote, a tradition that we were determined to uphold.

Editors were selected after hours of debate. Anyone in the masthead could ask a question and there was no early voting allowed. We ran the paper like a democracy, which had its difficult moments, especially given our diverse staff – the Maoists on the opinion page, the sports writers who were busy covering Jim Harbaugh and Bo, and those of us on the news side trying to figure out who the next University president would be.

Things grew particularly tense when the administration proposed a code of campus conduct that effectively split the paper into two camps. The University proposal was intended to address racist speech in the midst of a series of disturbing incidents. In a flash, the paper was divided between those of us who adamantly wanted to protect free speech, as was the long tradition of the Daily, dating back to Tom Hayden and company in the early 60s, and others who supported taking action to punish those responsible.

Without realizing it, we were in the middle of a maelstrom that would launch an extended national battle over political correctness. There were state hearings on campus, CNN came, many debates about how to cover this, and at times the paper seemed completely divided. Many other universities went on to propose similar codes of speech and conduct.

I was suddenly being interviewed on CNN and seeing my picture of the Detroit Free Press confronting anti-racist protestors. I’m certain I made mistakes in my handling of all this – I was just trying to hold it together, and somehow we did so, all the while covering the story we were at the center of.

It would be many years before I worked as hard as I did that year.

5. No one is watching out for you but yourself.

One of the biggest favors the Daily and the University of Michigan did for me was teach me to fend for myself. It ended up being a serious advantage in life.

Applying for my first newspaper internship as a junior, I sent resumes and clips to 100 papers on my own. There was no one in career services to help, or an advisor to smooth the way. I ended up at the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, and the summer after graduating at New York Newsday. I’m from Bay City, Michigan but fell in love with New York and being sent to all corners of Queens, which was a challenge in the days before Google maps – one number or dash wrong, and you were toast.

But I was more surprised by the other interns. At that point, I had four years of experience at the Daily and a summer in Pittsburgh. I was the only intern who was not from an ivy league school or, graduate school of journalism. And I remember at the end of summer, being shocked when one of my fellow interns asked me how to do a resume and clips. Clearly, they hadn’t done one to get the internship. It also underlined my advantages over the others. The Daily made us scrappy, and it’s something that has served me well.

I would say the same is true of the U, which offers training for a life where you are the one who is going to make things happen . No one else is going to do things for you.

It can seem quaint almost to the point of embarrassment to tell people that Alan Paul and I met at the Daily. He was the arts guy and I was a news person – it seemed like a big difference at the time… But the fact that our relationship began in a place that was so influential in shaping who both of us have become has been a blessing and a bedrock anchor. Alan has now written two books and is one of the best writers I know – some of you may remember him as the Fat Al columnist.

It can seem quaint almost to the point of embarrassment to tell people that Alan Paul and I met at the Daily. He was the arts guy and I was a news person – it seemed like a big difference at the time… But the fact that our relationship began in a place that was so influential in shaping who both of us have become has been a blessing and a bedrock anchor. Alan has now written two books and is one of the best writers I know – some of you may remember him as the Fat Al columnist.

The Daily inspired so many of us – and prepared us to take risks in life. I think of all the times I have been given a challenging assignment or asked to move to a new place – and somehow, it all seems doable because I have the foundation of the Daily, a place that practically begged us every day to take on ridiculous assignments and crazy challenges – and to take on the world.

I’m optimistic about journalism and the value of independent thinking that the Daily teaches. I could do a better job, quite honestly, in helping my fellow Daily alums navigate an uncertain job market. Let this occasion be a catalyst for those of us who are alums to work more closely with the Daily students. I would also like to congratulate Stephanie Steinberg for her book on the Daily.

And I know you join me in hoping that we are here to toast many years to come of the Michigan Daily – and to gather here again at its 150th.

Thank you.

Rebeccaâs speech at The Michigan Daily 125th Anniversary gala

While waiting to receive a copy of the video, I’ve posted a written copy of Rebecca’s speech from the Michigan Daily’s 125th Anniversary dinner. I will post the video as soon as I have it. It was an honor to help Becky craft this speech.

While waiting to receive a copy of the video, I’ve posted a written copy of Rebecca’s speech from the Michigan Daily’s 125th Anniversary dinner. I will post the video as soon as I have it. It was an honor to help Becky craft this speech.

The night before the dinner we attended the book launch for In the Name of Editorial Freedom: 125 Years at the Michigan Daily and enjoyed meeting other contributors from different Daily periods. One of them was John Papanek. He somehow communicated to Becky that his friend and Daily colleague Bill Alterman had been planning to attend but was too sick with cancer. He was Skyping with him at that very moment and she had a brief but impactful chat with him. It was enough to make her determined to share a great story from him in the speech. You will see it below.

John, as a loyal friend, was streaming the whole evening to a bed-ridden Bill in Washington DC and thought that he would be pleased to be mentioned. Everyone in the room cheered and sent him best wishes. He heard it all. And, rather unbelievably, he died the next day. I don’t what else to say except all of us Daily alumni are a family and it was kismet for Becky to meet John and talk to Bill and include his story. And that we send deepest condolences and most sincere wishes for healing and peace to all of his loved ones – blood-related and otherwise.

The speech:

Last minute run through at 420 Maynard.

Thanks very much, Neal – and thank you to everyone who made tonight possible.

Iâm very honored to be here.

I worked at the Daily from 1985-89 and was Editor in Chief my final year. Itâs hard for me to believe that it was 26 years ago because so much from my time there remains so vivid and relevant to my life.

Iâm now the deputy editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal. In my role, I meet a wide range of people, and they often ask about my journalism education. When I say that Iâve never taken a single journalism class in my life, most people are shocked. They canât understand how I trained for a career in journalism without ever studying the topic. It comes down to three words: The. Michigan, Daily.

Each of us walked into 420 Maynard as one person and walked out as another. Each of us had our 3 or 4-year window at the Daily, which felt completely unique and special. And each of us was probably too young to fully appreciate that we were in fact part of a long, proud and rather remarkable history of editorial freedom. It was 100 years when I was here. Maybe it was 60, 80, or 120 for you. We are all part of this unique and indispensible continuum.

Every year new student journalists walk in and old ones walk out. No one is continuously there and yet the traditions, the pride, the lore and legends pass down from class to class, with each group adding their own twists and turns â but never losing the thread.

Of course I knew all of this and I understood it intellectually but just last night so much of it became more emotionally resonant when I picked up this book that I was proud to contribute to:Â In the Name of Editorial Freedom: 125 Years at the Michigan Daily. Reading through this inspiring book, I am struck not only by the great writing and how unique and personal each personâs stories are â but by the threads that tie them all together.

The sense of mission. The jump-in-the-deep-end-then-learn-to-swim attitude. The passion. The tradition. The audacity. The earnestness. The rascally iconoclasm. Over and over, we see these things repeated as one group gives way to another, for generation after generation.

As Tom Hayden notes in the bookâs Foreword, from covering a Frederick Douglass speech in 1893 to uncovering a football playerâs covered-up sexual assault just a few years ago, the Daily has been playing an essential news gathering role on this campus for 125 years. Students who were not playing at being adults, but actually doing very real, very important things â whether they quite knew what they were doing or not.

I canât think of a bigger influence on the journalist â and the person â I became than the Daily, and the University of Michigan more broadly. The Daily taught me lifeâs most important lessons. I left 420 Maynard with most of what I needed to succeed in journalism and in lifeâ including my husband. And Iâm eternally grateful for all of it.

As I prepared to speak with you tonight, I thought long and hard about why the Daily such a valuable, enduring part of my education. I arrived at five lessons that the Daily taught me that remain central to my being.

Together, they add up to why we need to fight for the right for generations of students after us to maintain this marvelous continuum and to have the same privilege we all had: a strong, vibrant independent college paper.

1. The value of Editorial Independence and Freedom – of course!

1. The value of Editorial Independence and Freedom – of course!

I came to the Daily during my first week of school. Eric Mattson, Jerry Markon, Amy Mindell and Neil Chase started teaching me how to write headlines â I remember fjilt, were the counts of the letters… Georgea Kovanis assigned me my first story âabout the return of paisley. I was hooked. Before I knew it, I was covering the administrative beat.

Itâs impossible to imagine what the experience would have been like had there been a professor sitting at the center of the newsroom, or if the Daily had been run as part of a class. Working there gave us so much more than a textbook, a lecture and a grade. It gave us on-the-job training.

We took great pride in being independent from the University, and being a critical check on its power. And in continuing a proud tradition we were all profoundly aware of â which included not only a deep commitment to practicing great journalism but to teaching those coming behind us how to do so as well.

The editorsâ commitment to and enthusiasm for stories was infectious â but they were tough on copy and didnât mince words. And neither did anyone else on staff â as anyone who remembers the Crit Board will attest. It could be brutal to watch your work be subjected to peer review.

The examples of gutsy journalism â and editorial independence- at the Daily abound. John Papanek, one of the contributors to the Daily book, told me one yesterday that I found just incredible about his friend and former Daily Alum, Bill Alterman. In John’s words:

The game was November 6, 1971, at The Stadium in Ann Arbor. Michigan was on its way to what would have been its best years ever â a perfect 11-0 in the regular season â to be marred only by a 1-point loss to Stanford in the â72 Rose Bowl.

Michigan was killing everybody.On Nov. 6 it was Iowaâs turn. The final score was a blistering 63-7. An absolute debacle for Iowa. Bill Altermanâs assignment was to cover the losing team, so he dutifully took his place among the 30 or so other reporters assembled for the postgame press conference with the Iowa coach, Frank Lauterbur.

The room was deathly quiet when Lauterbur stormed in and took his seat at the podium. Smoke might as well have been pouring from his ears. Not one reporter dared ask a question and a long, awkward silence ensued. Lauterbur let the discomfort build, and finally broke the ice by barking, âWELL, WE GOT THE FUCKING SHIT KICKED OUT OF US TODAY.â

The room was shocked into another, even deeper, longer hush. Lauterbur milked it, and then did it again: âIn case you didnât hear me the first time, WE ⦠GOT ⦠THE ⦠FUCKING ⦠SHIT ⦠KICKED ⦠OUT ⦠OF ⦠US ⦠TODAY!

That pretty much ended the press conference.

Every single paper in Iowa and Michigan, and the national feeds of AP and UPI ran stories mentioning Lauterburâs “unprintableâ outburst, and of course no paper dared to print â or even euphemize â his exact words.

Every single paper except ONE.

Bill Alterman led his story with every one of Lauterbur’s words, as well as the emphatic reprise, and the Michigan Daily printed them. The Dailyâs Editor-in-Chief, Bob Kraftowitz, had to sign the proof copy to indemnify the typesetters against potential liability. And that was that. No University authority was involved or informed.

Altermanâs lede became a national sensation â ending up circled in red on newsroom bulletin boards across America. John says the clip — with the lede circled â was STILL on the central bulletin board at Sports Illustrated on his first day of work there , Dec. 1973. Is that editorial freedom or what?

Our thoughts go out to Bill, who really wanted to be here tonight but is battling cancer. We wish him all the best.

2. You have to love what you do to do it well.

2. You have to love what you do to do it well.

The Daily was a calling. We published five days a week and we governed ourselves â one person, one vote. It could be incredibly intense, but we knew we had to take it seriously because a 100 years of prideful editorial freedom was in our hands. That feeling of responsibility was weighty and made for some brutal debates and arguments. But it cemented the Daily and journalism in our hearts and minds as causes that were worth fighting for.

We sometimes took the obligation to extremes. We had perhaps an irrational view that the world might end â or we would lose our independence âif we blew a deadline or had a production problem and the Daily somehow didnât make it out one night.

This could be a particular challenge during the summer, when a small group of us stayed to put out a weekly edition. When we were told that there was no budget for distribution so the summer paper just couldnât get done, we scoffed and came up with a solution: we would distribute the paper ourselves. We took the finished boards up to a printer in Plymouth, watched it roll off the presses â what a thrill ! â and drove back to campus. Armed with a huge janitorsâ ring of keys to every building that mattered, we dropped bundles all over campus in the wee hours. Waiting until 8 am was never considered for some reason. What could go wrong? Campus police were generally understanding when they found us stumbling around at 2 am lugging heavy loads. Their brethren on rural roads were less kind.

One early morning, we were returning to Ann Arbor with the latest edition secured in the back of Steve Gregoryâs family station wagon when we saw blue lights flashing in the rearview mirror. As the police approached the car, Steve turned to us and said, âI may have a little problem with a suspended license. No matter what happens to me, make sure the Daily gets delivered.â

Everyone who cares enough to be in this room can probably relate. And yes we got the paper out that night.

3. If you want to get to your destination, you have to know how to navigate.

3. If you want to get to your destination, you have to know how to navigate.

Reporting and then editing stories while juggling my classes was extremely demanding. It led to many very late nights and some serious battles with my parents, who wondered not only why they kept getting notices about unpaid parking tickets from the U lot behind the paper â but why exactly I was spending so much time at that damned paper. (Iâll just say that my grades reflected some distractions).

They couldnât have known that what they thought was the distraction was actually the real course of study. Or that learning how to juggle so much was actually teaching me an incredible amount about managing a career, a newsroom and life â lessons that resonate profoundly to this day.

I arrived at the Daily in 1984, the last year before computers arrived. I remember the typewriters, the thin, off-white paper of our first drafts â the rubber glue and scraps of paper everywhere as stories were edited â literally by stripping off one offending word or paragraph and gluing down a replacement line. Often, a finished story looked like a two year oldâs art work â and that was before it was sent to a production team downstairs, with two ladies sitting at linotype machines spitting out copy to hand to the man we all initially feared: the intimidating, inimitable Lucius Doyle.

Lucius took the finished copy, ran it through a hot wax machine and attached it to the page. He worked with great precision and an Exacto knife that he clicked incessantly (blade toward you) as he peered over his bifocals and listened with impatience to the pleas of desperate editors to change a word, spelling or sentenceâ¦. Sometimes, he lost his patience, as we blew deadline and kept him late. Lucius was the adult in the room, and his authority was unquestioned. He had seen it all.

I was terrified when I first met Lucius and stayed as far away from him as long as possible. I remember my voice trembling one of the first times I had to ask for a change on the page. But I learned to talk to him â and started going out of my way just to chat with him. I made sure the changes I asked for were really necessary. And as time passed, we delighted in getting him to tell us stories about past editors, which he did with relish. Toward graduation, he allowed us to take him for a beer, which was such an honor. He loved the Daily completely, and I only wish that he could have been here tonight, as he taught me and many others so much.

Reading through the Daily book, I was inspired by so many stories. One that stands out is that of Sara Krulwich, who courageously challenged the Universityâs rule in 1969 that no women were allowed on the football field⦠âThis was no joke, â she writes.. âno women in the marching band, no women cheerleaders, no women security guards.. â

On the first day of the season, she approached the head of sports information with another Daily photographer to challenge the edict. When he told her that she wasnât allowed, she calmly told him that she had the right to be there.. he replied that she would be escorted out.. but then the game began, she stayed, and her fellow photographer told her to start shooting.. nothing happened and she eventually received an apology.

âTen years later, I returned to Michigan to cover a game as a staff photographer for the NYT,” she writes. “There were women cheerleaders, in the band, everyone… My first act of civil disobedience remains one of the most important days of my life. It was the moment that convinced me to make photojournalism my career.â

4. Dealing with dissent â and intensity

We governed ourselves: one person, one vote, a tradition that we were determined to uphold.

Editors were selected after hours of debate. Anyone in the masthead could ask a question and there was no early voting allowed. We ran the paper like a democracy, which had its difficult moments, especially given our diverse staff â the Maoists on the opinion page, the sports writers who were busy covering Jim Harbaugh and Bo, and those of us on the news side trying to figure out who the next University president would be.

Things grew particularly tense when the administration proposed a code of campus conduct that effectively split the paper into two camps. The University proposal was intended to address racist speech in the midst of a series of disturbing incidents. In a flash, the paper was divided between those of us who adamantly wanted to protect free speech, as was the long tradition of the Daily, dating back to Tom Hayden and company in the early 60s, and others who supported taking action to punish those responsible.

Without realizing it, we were in the middle of a maelstrom that would launch an extended national battle over political correctness. There were state hearings on campus, CNN came, many debates about how to cover this, and at times the paper seemed completely divided. Many other universities went on to propose similar codes of speech and conduct.

I was suddenly being interviewed on CNN and seeing my picture of the Detroit Free Press confronting anti-racist protestors. Iâm certain I made mistakes in my handling of all this â I was just trying to hold it together, and somehow we did so, all the while covering the story we were at the center of.

It would be many years before I worked as hard as I did that year.

5. No one is watching out for you but yourself.

One of the biggest favors the Daily and the University of Michigan did for me was teach me to fend for myself. It ended up being a serious advantage in life.

Applying for my first newspaper internship as a junior, I sent resumes and clips to 100 papers on my own. There was no one in career services to help, or an advisor to smooth the way. I ended up at the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, and the summer after graduating at New York Newsday. Iâm from Bay City, Michigan but fell in love with New York and being sent to all corners of Queens, which was a challenge in the days before Google maps â one number or dash wrong, and you were toast.

But I was more surprised by the other interns. At that point, I had four years of experience at the Daily and a summer in Pittsburgh. I was the only intern who was not from an ivy league school or, graduate school of journalism. And I remember at the end of summer, being shocked when one of my fellow interns asked me how to do a resume and clips. Clearly, they hadnât done one to get the internship. It also underlined my advantages over the others. The Daily made us scrappy, and itâs something that has served me well.

I would say the same is true of the U, which offers training for a life where you are the one who is going to make things happen . No one else is going to do things for you.

It can seem quaint almost to the point of embarrassment to tell people that Alan Paul and I met at the Daily. He was the arts guy and I was a news person â it seemed like a big difference at the time⦠But the fact that our relationship began in a place that was so influential in shaping who both of us have become has been a blessing and a bedrock anchor. Alan has now written two books and is one of the best writers I know â some of you may remember him as the Fat Al columnist.

It can seem quaint almost to the point of embarrassment to tell people that Alan Paul and I met at the Daily. He was the arts guy and I was a news person â it seemed like a big difference at the time⦠But the fact that our relationship began in a place that was so influential in shaping who both of us have become has been a blessing and a bedrock anchor. Alan has now written two books and is one of the best writers I know â some of you may remember him as the Fat Al columnist.

The Daily inspired so many of us â and prepared us to take risks in life. I think of all the times I have been given a challenging assignment or asked to move to a new place â and somehow, it all seems doable because I have the foundation of the Daily, a place that practically begged us every day to take on ridiculous assignments and crazy challenges â and to take on the world.

Iâm optimistic about journalism and the value of independent thinking that the Daily teaches. I could do a better job, quite honestly, in helping my fellow Daily alums navigate an uncertain job market. Let this occasion be a catalyst for those of us who are alums to work more closely with the Daily students. I would also like to congratulate Stephanie Steinberg for her book on the Daily.

And I know you join me in hoping that we are here to toast many years to come of the Michigan Daily â and to gather here again at its 150th.

Thank you.

September 14, 2015

Full Set Video â Tedeschi Trucks Band and Friends, Mad Dogs and Englishmen

Photo by Ian Rawn

Tedeschi Trucks Band & Friends, Tribute To Joe Cocker and Mad Dogs & Englishmen, Lockn’ Festival, Arrington, VA – 9/11/15

Introduction, The Letter, Darling Be Home Soon, Cry Me A River, Girl From The North Country, Dixie Lullabye, Bird On A Wire*, The Weight, Superstar*, Delta Lady#, Let’s Go Get Stoned @, Something^, Band Intros, She Came In Through The Bathroom Window , Feelin’ Alright %, Sticks And Stones $, Space Captain $

Encore: Ballad Of Mad Dogs And Englishmen (Leon Russell Solo), With A Little Help From My Friends

* With Rita Coolidge On Vocals

# With John Bell On Vocals

@ With Alicia Shakour On Vocals

^ With Doyle Bramhall On Vocals

With Warren Haynes On Guitar And Vocals

% With Dave Mason On Vocals

$ With Chris Robinson On Vocals

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

September 13, 2015

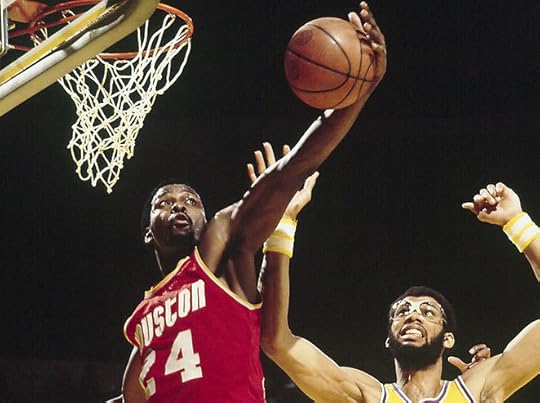

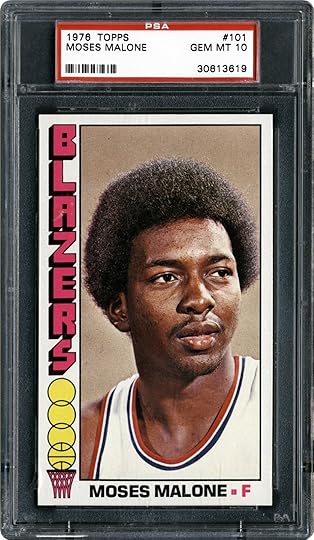

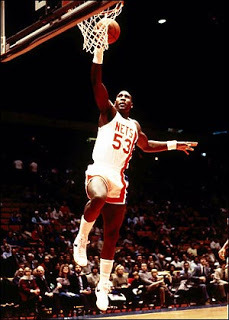

RIP Moses Malone

I was really sad to hear that Moses Malone passed away in his sleep last night. He was just 60 years old. It’s really odd and extra discomfiting that he died so shortly after Darryl Dawkins.

I was really sad to hear that Moses Malone passed away in his sleep last night. He was just 60 years old. It’s really odd and extra discomfiting that he died so shortly after Darryl Dawkins.

I interviewed him for Slam, circa 2004. He was kind, funny and quite easy to talk to. Here is that story, unedited.

•

As the first guy to go directly from high school to professional basketball, way back in ’74, Moses Malone would be a legendary, landmark figure even if he had been a failure. Fact is, though, he was one of the four greatest centers ever to play, and he remains the greatest straight-to-pros player ever, at least until Kobe or KG proves otherwise.

Malone was a three-time MVP, a 12-time All Star, one of the 50 greatest Players in NBA History (as selected by the league in 96) and a shoo-in Hall of Famer. In the heart of his career, he amassed an amazing 11 straight seasons averaging better than 20-10. Counting his two years in the ABA, Moses scored 29,580 points in 21 seasons, sixth on the all-time list behind Kareem, Karl, Wilt, MJ and Doc. He also grabbed 17,834 boards, less than only Wilt and Bill Russell. He’s also second in free throws made and attempted, fourth in minutes played and fifth in games.

Still, he’s been somewhat overlooked, perhaps because he wasn’t a larger than life figure like Wilt or Shaq, an iconic cultural figure like Kareem or the core of a dynasty like Bill Russell. He also spent little time currying the favor of reporters, seemingly happy to let his game speak for itself, content in his blue collar image.

“I came up in a small town ghetto and I never did think I’d be a celebrity or famous athlete,” says Malone, who now lives in Houston. ”I was just loving to play the game of basketball. And I worked hard at everything I did.”

Malone’s Petersburg High won 50 straight games and two state titles. He was probably the most highly recruited basketball player ever. A New Mexico assistant supposedly lived at a Petersburg Howard Johnsons for two months hoping to land Mo, who eventually signed with Maryland only to jump right to the ABA’s Utah Stars. The NBA prohibited high school students from entering, but the struggling ABA had no such issues. The 6-10, 210-pound manchild averaged 17.2 rpg and 13 rpg and shot 55 percent in two years in the league, before passing through the Buffalo Braves and landing in Houston. He elevated from great to superstar in his fifth season, 78-79, when he put up 24.8 ppg and 17.6 rpg and won his first MVP. By then, he had put on at least 20 pounds and eventually he would top 250 pounds, though almost until the end he maintained the quickness and agility that allowed him to be such a dominant rebounder.

Big Mo secured his place in history in 83 when was traded to Philly and finally led Dr. J to the promised land of a title, to which he had come tantalizing close in previous years. That team demolished the league, going 65-17 and only losing one playoff game and Malone was the MVP of the both the regular season and the Finals.

Malone hung on until 95 but his last three years as a journeyman center did nothing to diminish a great career, one that he says included inventing the alley oop with John Lucas.

SLAM: You hold the record for offensive rebounds in a season. What was the key to your success there?

MALONE: To be a great offensive rebounder, you have to think like a defensive rebounder and battle for position while also being in the flow of your offense. And then it’s just being determined. You got to work hard whatever you’re doing and try to be number one and take pride in what you’re doing. You want to be at the best at your spot then you got to work hard, man. A lot of guys don’t work as hard as it gonna take.

SLAM: When did you first start realizing you had the potential to become a great basketball player?

MALONE: Pretty fast. I had God given talent. No one taught me this game. I taught myself and I did it because I loved the game. I wasn’t playing for no big money. I was playing for orange juice. I started playing ball when I was 13 and a half. Before that, I just wanted to play football and baseball but I kept growing so I figured it was time for basketball. Then I was on the playground all night. I ain’t never go to parties or nothing. I’d get out of school at 3 and be out there playing until one in the morning with one streetlight. For real.

SLAM: Is it true that kids on the playground wouldn’t let you play unless you agreed to not enter the lane?

MALONE: Oh yeah. When I was 15, they changed the playground rules because I was dominating everything and blocking everything that came my way. I had a lot of skills and I played strong, which goes to my friend Babyhead. He was about four years older and he was always picking me for his team and he was always on me to be hard at all times. Every time I went to the hole, he wanted me to dunk. He’d go, “Young fella, I picked you because you’re the best. I know you’re just 15 but you come to play. And you have to bring it every game.”

MALONE: Oh yeah. When I was 15, they changed the playground rules because I was dominating everything and blocking everything that came my way. I had a lot of skills and I played strong, which goes to my friend Babyhead. He was about four years older and he was always picking me for his team and he was always on me to be hard at all times. Every time I went to the hole, he wanted me to dunk. He’d go, “Young fella, I picked you because you’re the best. I know you’re just 15 but you come to play. And you have to bring it every game.”

In high school, my coach had this philosophy too. There were always two guys checking me at least – sometimes three out of five. I would get real frustrated but he always told me it would make me better in the long run and it really did. II had to get around two guys to score or get a rebound every game my last two years in high school. It made me stronger and tougher.

SLAM: You were the first player to go directly from high school to professional ball. Did you ever think it would become so commonplace?

MALONE: No. They might as well just shut down college ball now. [laughs] Now guys become first round picks and make all the millions without really proving themselves. Are they gonna go all the way down to elementary school looking for kids who can jump high? The real question is this: do you have it in your head or heart to be great? To work hard enough to be what you can be? That’s hard to see, but I think the problem is these so called scouts don’t know what they’re looking at.

When I came out of high school I was getting 38 points, 16 rebounds and 10 or 12 blocks a game. If they put my numbers up there next to Lebron James, I was doing more damage. Maybe I could have gotten a billion-dollar shoe contract. [laughs] But I don’t fault none of these kids. They got to say yes. If you don’t take it, I’ll put these size-16 shoes in your butt my own self. [laughs]

SLAM: What is the hardest adjustment in going pro at such a young age?

MALONE: I always was confident, but I had guys looking out for me and that’s real important. Got to have that, not just people looking for a gravy train. Then you’re in trouble, because you’re not man enough to understand what’s going on. I had my agent up in Washington DC, who’s still with me, and my teammates took me under their wings, especially Ron Boone, Gerald Govan, Wali Jones and Roger Brown. They brought me up just like I was their son and they really taught me how to grow to be a man in life and how to prepare yourself for every game.

Ron Boone was like a father to me. He saw that I needed guidance and he gave it to me, helped me mature as a person. He took me home and his wife cooked me many meals, made me feel comfortable, and I could talk to them about everything in life.

One thing for anyone coming in but especially the kids: you can’t be afraid. You got to be determined that you want to be the best, but you don’t have to talk about it. You see someone talking about how great they are, they ain’t great. When I played, I never talked about what I was gonna do. I just did it.

SLAM: Maybe that’s why you’ve been underrated.

MALONE: Well, someone’s been misrepresenting me I guess. Because I’m the only high school player who ever got three MVPs, 21 years and the Hall of Fame. I’m everything they thought I shouldn’t have been and wouldn’t be.

SLAM: Who guarded you the toughest?

MALONE: Artis Gilmore. But then there was Kareem Abdul Jabbar, Bill Walton, Robert Parish, Dave Cowens and even Swen Nater, who no one remembers. Every center in the league played me tough. There was never an easy night so you had to prepare every game, figure out their strong points and weak points and try to take advantage of whatever you could. And you knew they were doing the same thing for you.

SLAM: Almost every team had a good to great center. Where have all they gone?

MALONE: They all retired now [laughs] They really only got two or three real centers in the league now: Shaq, Mourning, who’s been sick, and now Yao Ming. You can’t be a real center unless you want play around the basket and bang. Now you got 7-foot guys who want to finesse. Hmmph. They don’t want to put on no hardhats and go to work. I don’t care what people say: it takes a big man to know how to post up and it takes you a good guard to open it up for them. Look how the Spurs won. They had Duncan and Robinson and then one little guy every game: Kerr, Parker, someone. Without that little guy, everyone’s gonna collapse on the big man, but without the big man that little guy ain’t getting clean looks. Only team I saw win with two small guys was the Bulls with Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen.

SLAM: You set a record by playing 1.046 games without fouling out, yet you were a very physical player. How did you do that?

MALONE: I was good to the referees. [laughs] I knew them all. They got to call the game and you have to respect them. They make some bad calls, but never embarrass the referee. They got to do the work so once they make a call, let it be.

SLAM: You came to Philly and Doctor J finally got his ring.

SLAM: You came to Philly and Doctor J finally got his ring.

MALONE: That was Dr. J’s team. I was just a piece of the puzzle. It was a great, great team before I got there. They had Doc, Andrew Toney, one of the best shooters ever, Maurice Cheeks, a great point guard, Bobby Jones coming off the bench as one of the best defenders in the League. And lots of role players like Clint Richardson and Marc Iavaroni.

SLAM: Right., But they were a great team who couldn’t quite win a title.

MALONE: Yeah, yeah. They needed me – but I needed them, too. Doc was one of the greatest players ever, no doubt, and I always thank him for giving me the opportunity to win a championship.

SLAM: At the start of the playoffs, you said you’d win it in “Fo, Fo, Fo.” Doc said you didn’t mean that would sweep every series, that you were just saying that’s how many games you needed to win it all.

MALONE: No, no. I wanted a sweep. Three sweeps, actually, and we almost got them. We did Fo, Five, Fo. I wanted to start summer early and Fo, Fo, Fo sounded good to me. I knew with the players we had that we were going to win and I didn’t see no reason to play extra games.

SLAM: You also had some great teams in Houston, going to the Finals once and playing with some great, underrated players. Let’s talk about them, beginning with Calvin Murphy.

MALONE: Murphy was probably the best pro shooter that I played with. Toney’s the only other one in his league. That gave me room to operate and also Murphy was a tough little guy. Oh yeah!

SLAM: Rick Barry

MALONE: Rick Barry could shoot the three and keep you open, too and also make some great passes. He was determined to win, always came with the focus on victory.

SLAM: John Lucas.

MALONE: John was a good penetrating guard who always go the action going.. He’ll make you play. Luke wanted to win and he was a very exciting guy. And I’ll tell you something, him and me were the first guys to come up with the alley oop. We invented that. See, everyone played me real hard up top to keep me from getting the ball, so Luke started tossing it over them so I could leap up and grab it and just put it through. When we first did it, the other teams would scream that it was goal tending, because they thought Luke was shooting. Now it’s become a regular play, but no one knew what it was when we started.

SLAM: You were traded to the Sixers after winning your second MVP. How could anyone trade a guy who just averaged 31.1 ppg and 14.7 rpg?

MALONE: Simple. I was a restricted free agent and they didn’t want to pay the money. Now they’re paying everybody but it came down to dollars and cents. Hey, I got traded from the Sixers eventually, too. Everybody can get traded, man.

September 11, 2015

9-11 14 Years Later: Still Raw

Reposted as I will every year on this date. I don’t think the words will ever be any less true. The following summer I visited the Flight 93 crash sight in Shanksville, PA and paid my respects. All the same feelings…

Fourteen years later, 9-11 is still very, very raw to me.

In 2011, on the tenth anniversary, my whole family visited the Statue of Liberty and we went up in the crown. The security was tight. There were helicopters flying overhead. And when we got back on the ferry to leave, I looked back at the Statue of Liberty and felt as patriotic as I ever have and I thought, “She’s still here and you’re not.”

We took a family picture and we smiled because it felt good to be alive and to be together, and to feel like our way of life had not been destroyed. But we smiled with heavy hearts, because, of course, we thought about everyone who wasn’t there, everyone we all should remember on this day every year.

We came back from the Statue and walked through the very beautiful memorial in Jersey City, in Liberty State Park. I walked through it silently, looking at the names etched on the side: husbands, wives, daughters, sons, lovers, friends who never came home. And I wept to myself.

It’s still so real.

Part of me wants 9-11 to be a National holiday but I can’t bear the thought of it becoming like Memorial or Labor Day; another excuse for sales and a cooler full of beer.

I know this was a national tragedy, but I just don’t think people outside of the NYC area felt it or understood it in quite the same way as those of us who were here in the metro area. We saw the cars sitting unclaimed in the train stations. The missing posters lovingly hand written and pasted all over the city, the candles burning in front of every fire station.

At noon on 9-11, I was at the South Mountain YMCA picking up Jacob, who was 3, and helping the director go through the files looking for kids who had two parents working in Manhattan, flagging two kids whose parents both worked in the Towers. It took hours until everything sorted itself out. One little baby girl lost her mother. A father around the corner never came home.

The next day I went up to the South Mountain Reservation, walked over to the edge of the wall on the bluff overlooking downtown New York and where the towers used to be was a big grey cloud swirling around and filling the air – even here, 25 miles away – with an acrid smell.

I want to make sure my kids understand, really understand, how real this was. How real it still is to me. So I will take them up there in a few minutes to lay some flowers at the memorial. It sprouted immediately, spontaneously, and is now official, honoring our friends and neighbors who got up and went to work and never came home.

“Never forget” means a lot of things to a lot of people. I’m thinking of them.

September 3, 2015

My Backstory Interview with Warren Haynes