Alan Paul's Blog, page 24

December 2, 2015

The Allman Brothers Band Memorabilia â an Interview

I’ve been really enjoying a new book, The Allman Brothers Band Classic Memorabilia, 1969-76. The topic is pretty much right in the title.

The book highlights individual collectibles, including band instruments and equipment, t-shirts, apparel and merchandise, autographs, bookkeeping documents, passes, posters, tickets, programs, promotional items, vintage photographs, and more. Duane’s Galadrielle Allman wrote the introduction.

The authors are Willie Perkins, the Allman Brothers road manager from 1970-76 and Jack Weston, an avid ABB collector who hipped me to the awesome W. David Powell coloration of David and Flournoy Holmes that graces the front and back inside covers of  One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. Willie is also the author of No Saints, No Saviors: My Years with the Allman Brothers Band.

I caught up with Willie and Jack for the following interview.

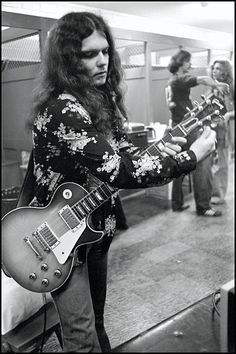

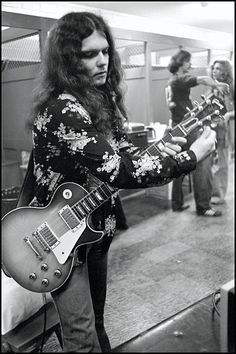

Duane 1970 – Twiggs Lyndon photo.

Willie â you were in the middle of a hurricane and at the center of what many consider the best rock band ever. How aware were you of all that at the time, and how much were you just hanging in on for dear life every day?

PERKINS: A lot of hanging on! Linda Oakley told me recently that the band guys had me so flipped out my eyes were spinning around in their sockets like a cartoon character. We were so busy getting it done that there was little time for reflection as I note in the book. I remember early on saying: “This is the best band in America, only America doesn’t know it yet.â That was somewhat prophetic.

You kept a lot of documents and files, so you must have had some sense that this stuff would have historical significance. Do you remember when it started to occur to you that things like tour ledgers and guitar cases would be of interest to people?

PERKINS: Probably around the time of Duane’s passing. We certainly knew those guitars had to be secured that weekend before they “wandered” off. I don’t think anyone began collecting for monetary gain. I know that I wanted to preserve from a historical perspective any important documents I had possession of. By the late 1990’s I realized business checks signed by Duane definitely had collector appeal and monetary value. I receive almost weekly social media inquiries regarding dates and sequences of shows performed and am so glad I held on to copies of the monthly personal appearance financial reports. That info is priceless to me and I have the most comprehensive records for 1971 – 1976.

Jack, when did you start collecting ABB memorabilia?

WESTON: I first started to collect Allman Brothers Band memorabilia in the late 1980âs. It was driven by my love of the bandâs music which first began in 1971 soon after I heard the bandâs At Fillmore East. I began to trade tapes with other tape traders that placed ads in the back section of Relix magazine. Most of the traders at this time were trading Grateful Dead cassette concert tapes but some were also trading Allman Brothers Band shows. In addition to concert tapes some of the Allman Brothers Band traders were trading posters, handbills, tickets, photos , and other ephemera from the bandâs early days. When the Allman Brothers Bandâs magazine Hittinâ The Note was first published in the early 1990âs I became a subscriber and it had a traders section in it as well which of course fueled the fire.

Is there one section or even item in the book that you would like to call special attention to? What are you most proud about?

PERKINS: I am so glad we led off the book with “instruments and musical equipment” because the band was certainly all about the music. I am pleased with the high definition and clarity of the images. Also, Jack and I gave the book design concept to the team Burt & Burt and they delivered exactly what I had in mind and our publishers Mercer University Press gave us virtually everything we asked for and didn’t edit a single word or image. The colors and concept just pops right off the page.

WESTON: It would have to be Dickey Bettsâ 1968 Fender Bassman amplifier, one of the first two purchased by the band in early 1969. It was at first used by Duane Allman, Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley. Then it became Dickey Bettsâ stage amp. The bandâs first road manager Twiggs Lyndon wrote â Allman Brosâ and âDickâ on the back panel of the amp in white marker pen. The Lipham Music Co invoice for this ampâs purchase is also pictured in this chapter showing the ampâs serial number. I learned a great deal after having this amplifier restored to working condition. When I first acquired the amp the two output tubes in it were modern Groove Tubes. These were replaced with a set of original matched 1960âs Fender brand 6L6âs. My friend Skip Simmons of Sacramento, California did a historical restoration of the ampâs electronics. Only the power supply capacitors needed replacement. All the other active electronics in the amp are vintage original.

There are a lot of great and beloved bands but none have their own museum like The Big House. What do you attribute this to?

PERKINS: I give 100% credit to the idea of restoring and conserving the Big House to Kirk and Kirsten West. There have been many financial and creative contributions made by countless others, but they had the foresight and love to get the ball rolling. The band inspired a lot of love from a lot of people with the soul, passion and originality of their music. The museum is manned by a great staff and volunteers as well. Nothing like it for any band before or since!

WESTON: The history of The Allman Brothers Band spans over 50 years. As a result The Allman Brothers Band has a very large and loyal fan base, which encompasses virtually all age groups. From the time the band played free concerts at Piedmont Park in Atlanta until its final concert at The Beacon Theater in 2014 it has always been regarded as âThe Peopleâs Band. I canât recall many other bandâs having this unique type of fan base other than The Grateful Dead. As you know, The Big House Museum was once the home of the band in the early years. It is not just a museum. It is a home. This unique combination is why The Big House has so many fans coming back year after year to share in the music, culture, and legacy of their favorite band.

What about the Allman Brothers inspires so much passion? Â

WESTON: To me the passion stems from âThe Brotherhood,â which was established early on between the founding band members, their families, and the bandâs original road crew. In the beginning it was a strong cohesive brotherhood that still exists today amongst the bandâs contingent of loyal fans. This passion was inspired early on by founding member Duane Allman making the musical journey revolutionary as well as evolutionary.

Willie, a lot of your tour documents are now in the Big House Archives and were incredibly helpful for me in researching One Way Out. So thanks for that.

PERKINS: I am glad so many of my financial records and other items of interest made it to the Big House Museum and they will be preserved for current and future fans and historians. I am glad Jack’s and my book will do the same in the printed word and image medium as well.

November 18, 2015

New Tedeschi Trucks Band Album – January 29

This is a press release – not my words or thoughts! I just thought my people would want the info.

This is a press release – not my words or thoughts! I just thought my people would want the info.

On January 29th, 2016 Tedeschi Trucks Band, led by the husband-and-wife team of singer-guitarist Susan Tedeschi and guitar virtuoso Derek Trucks, will cap an extraordinary and transformative year with the release of Let Me Get By, their third full-length LP and debut for Fantasy Records. Listen to the lead album track “Anyhow” on the bands website:

http://tedeschitrucksband.com/

In addition, the special, 2-Disc deluxe version of Let Me Get By includes an 8-track bonus disc featuring live recordings from the legendary Beacon Theatre in New York, alternate mixes, early song takes and additional studio material, along with an expanded booklet containing exclusive studio and live photos, all housed in a custom-designed vintage amp box. The 10-track standard version and 18-track deluxe version are both available for pre-order beginning today on the TTB website and via iTunes and Amazon beginning Friday.

In addition, the special, 2-Disc deluxe version of Let Me Get By includes an 8-track bonus disc featuring live recordings from the legendary Beacon Theatre in New York, alternate mixes, early song takes and additional studio material, along with an expanded booklet containing exclusive studio and live photos, all housed in a custom-designed vintage amp box. The 10-track standard version and 18-track deluxe version are both available for pre-order beginning today on the TTB website and via iTunes and Amazon beginning Friday.

Recorded at Swamp Raga Studios, the band’s home studio in Jacksonville, Florida, Let Me Get By is an absorbing, self-assured, artistic leap forward. Playing with an economy of power and uncommon grace, the 12-piece outfitone of the most deeply skilled and admired musical ensembles in the worldexplores themes of independence, love and release.

Let Me Get By is an album of firsts in addition to being the first TTB record Trucks produced on his own, and the first on which he and Tedeschi wrote all the songs within the TTB family, it’s Trucks’ first album since his 15-year run as a member of the Allman Brothers concluded when the group disbanded last year. In Trucks’ own words, “That’s what I hear in the music on this new album – this feeling that we’re now putting 100% of what we have into this band, not going back to anything else, everyone giving it their all.”

The songs are distinct for their communal nature, with each band member contributing to the album’s varied and diverse sonic textures. Opener “Anyhow” perfectly embodies the group’s newfound liberation; with Tedeschi’s voice levitating above a symphony of towering horns and Trucks’ inventive soaring slide guitar tones. Elsewhere, “Dont Know What It Means” serves up a funky church sermon, and “Crying Over You” delivers a classic 70’s Philly soul throwback.

Combining inspired Memphis soul, electric rhythm & blues, country, rock and classic song craft; TTB has captured the admiration of both concert audiences and critics worldwide. Since their inception in 2010, TTB have seen both of their previous albums debut in the top 15 of the Billboard Top 200 album chart, and won a GRAMMY for their debut album Revelator, which was hailed by Rolling Stone as a “masterpiece.” They tour over 200 days a year, with such highlights as headlining their first Wheels of Soul amphitheater tour this past summer, four consecutive sold-out shows at the Beacon Theatre in NYC this fall, and a surprise appearance on the debut episode of the Late Show with Stephen Colbert. In studio and on stage, TTB continue to flourish and surprise, and the release of Let Me Get By marks the beginning of another exciting chapter in the bands storied tale.

Let Me Get By track list:

1. Anyhow

2. Laugh About It

3. Don’t Know What It Means

4. Right On Time

5. Let Me Get By

6. Just As Strange*

7. Crying’ Over You/Swamp Raga for Holzapfel, Lefebvre, Flute and Harmonium

8. Hear Me*

9. I Want More*

10. In Every Heart

Produced by Derek Trucks

Recorded and Mixed by Bobby Tis

*Co-produced by Derek Trucks and Doyle Bramhall II

Mastered by Bob Ludwig

TOUR DATES:

Dec 3 – Port Chester, NY – The Capitol Theatre

Dec 4 – New Haven, CT – College Street Music Hall

Dec 5 – Providence, RI – Providence PAC

Dec 8 – Albany, NY – Hart Theatre at The Egg

Dec 10 – Roanoke, VA – Jefferson Center

Dec 11 – Virginia Beach, VA – Sandler Center

Dec 12 – Asheville, NC – U.S. Cellular Center

Dec 143 – Austin, TX – Austin City Limits

Jan 16 – St. Petersburg, FL – Sunshine Music Festival

Jan 17 – Boca Raton, FL – Sunshine Music Festival

Jan 19 – Augusta, GA – Bell Auditorium

Jan 20 – Jackson, MS – Thalia Mara Hall

Jan 22 – Chicago, IL – Chicago Theatre

Jan 23 – Chicago, IL – Chicago Theatre

Feb 18 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 19 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 20 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 25 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Feb 26 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Feb 27 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Mar 3 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 4 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 5 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 19 – Melbourne, AUS – Forum Melbourne

Mar 20 – Canberra, AUS – Canberra Theatre Centre

Mar 22 – Newtown, AUS – Enmore Theatre

Mar 24 – Byron Bay, AUS – Byron Bay Bluesfest

Mar 30 – Nagoya, JPN – Nagoya City Auditorium

Mar 31 – Osaka, JPN – Orix Theater

Apr 1 – Toyko, JPN – Nippon Budokan

http://www.tedeschitrucksband.com

https://www.facebook.com/DerekAndSusan

https://twitter.com/derekandsusan

www.concordmusicgroup.com

New Tedeschi Trucks Band Album â January 29

This is a press release – not my words or thoughts! I just thought my people would want the info.

This is a press release – not my words or thoughts! I just thought my people would want the info.

On January 29th, 2016 Tedeschi Trucks Band, led by the husband-and-wife team of singer-guitarist Susan Tedeschi and guitar virtuoso Derek Trucks, will cap an extraordinary and transformative year with the release of Let Me Get By, their third full-length LP and debut for Fantasy Records. Listen to the lead album track “Anyhow” on the bandÂs website:

http://tedeschitrucksband.com/

In addition, the special, 2-Disc deluxe version of Let Me Get By includes an 8-track bonus disc featuring live recordings from the legendary Beacon Theatre in New York, alternate mixes, early song takes and additional studio material, along with an expanded booklet containing exclusive studio and live photos, all housed in a custom-designed vintage amp box. The 10-track standard version and 18-track deluxe version are both available for pre-order beginning today on the TTB website and via iTunes and Amazon beginning Friday.

In addition, the special, 2-Disc deluxe version of Let Me Get By includes an 8-track bonus disc featuring live recordings from the legendary Beacon Theatre in New York, alternate mixes, early song takes and additional studio material, along with an expanded booklet containing exclusive studio and live photos, all housed in a custom-designed vintage amp box. The 10-track standard version and 18-track deluxe version are both available for pre-order beginning today on the TTB website and via iTunes and Amazon beginning Friday.

Recorded at Swamp Raga Studios, the band’s home studio in Jacksonville, Florida, Let Me Get By is an absorbing, self-assured, artistic leap forward. Playing with an economy of power and uncommon grace, the 12-piece outfitÂone of the most deeply skilled and admired musical ensembles in the worldÂexplores themes of independence, love and release.

Let Me Get By is an album of firsts  in addition to being the first TTB record Trucks produced on his own, and the first on which he and Tedeschi wrote all the songs within the TTB family, it’s Trucks’ first album since his 15-year run as a member of the Allman Brothers concluded when the group disbanded last year. In Trucks’ own words, “That’s what I hear in the music on this new album – this feeling that we’re now putting 100% of what we have into this band, not going back to anything else, everyone giving it their all.”

The songs are distinct for their communal nature, with each band member contributing to the album’s varied and diverse sonic textures. Opener “Anyhow” perfectly embodies the group’s newfound liberation; with Tedeschi’s voice levitating above a symphony of towering horns and Trucks’ inventive soaring slide guitar tones. Elsewhere, “DonÂt Know What It Means” serves up a funky church sermon, and “Crying Over You” delivers a classic 70’s Philly soul throwback.

Combining inspired Memphis soul, electric rhythm & blues, country, rock and classic song craft; TTB has captured the admiration of both concert audiences and critics worldwide. Since their inception in 2010, TTB have seen both of their previous albums debut in the top 15 of the Billboard Top 200 album chart, and won a GRAMMY for their debut album Revelator, which was hailed by Rolling Stone as a “masterpiece.” They tour over 200 days a year, with such highlights as headlining their first Wheels of Soul amphitheater tour this past summer, four consecutive sold-out shows at the Beacon Theatre in NYC this fall, and a surprise appearance on the debut episode of the Late Show with Stephen Colbert. In studio and on stage, TTB continue to flourish and surprise, and the release of Let Me Get By marks the beginning of another exciting chapter in the bandÂs storied tale.

Let Me Get By track list:

1. Anyhow

2. Laugh About It

3. Don’t Know What It Means

4. Right On Time

5. Let Me Get By

6. Just As Strange*

7. Crying’ Over You/Swamp Raga for Holzapfel, Lefebvre, Flute and Harmonium

8. Hear Me*

9. I Want More*

10. In Every Heart

Produced by Derek Trucks

Recorded and Mixed by Bobby Tis

*Co-produced by Derek Trucks and Doyle Bramhall II

Mastered by Bob Ludwig

TOUR DATES:

Dec 3 – Port Chester, NY – The Capitol Theatre

Dec 4 – New Haven, CT – College Street Music Hall

Dec 5 – Providence, RI – Providence PAC

Dec 8 – Albany, NY – Hart Theatre at The Egg

Dec 10 – Roanoke, VA – Jefferson Center

Dec 11 – Virginia Beach, VA – Sandler Center

Dec 12 – Asheville, NC – U.S. Cellular Center

Dec 143 – Austin, TX – Austin City Limits

Jan 16 – St. Petersburg, FL – Sunshine Music Festival

Jan 17 – Boca Raton, FL – Sunshine Music Festival

Jan 19 – Augusta, GA – Bell Auditorium

Jan 20 – Jackson, MS – Thalia Mara Hall

Jan 22 – Chicago, IL – Chicago Theatre

Jan 23 – Chicago, IL – Chicago Theatre

Feb 18 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 19 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 20 – Philadelphia, PA – Keswick Theatre

Feb 25 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Feb 26 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Feb 27 – Washington, D.C. – Warner Theatre

Mar 3 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 4 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 5 – Nashville, TN, – Ryman Auditorium

Mar 19 – Melbourne, AUS – Forum Melbourne

Mar 20 – Canberra, AUS – Canberra Theatre Centre

Mar 22 – Newtown, AUS – Enmore Theatre

Mar 24 – Byron Bay, AUS – Byron Bay Bluesfest

Mar 30 – Nagoya, JPN – Nagoya City Auditorium

Mar 31 – Osaka, JPN – Orix Theater

Apr 1 – Toyko, JPN – Nippon Budokan

http://www.tedeschitrucksband.com

https://www.facebook.com/DerekAndSusan

https://twitter.com/derekandsusan

www.concordmusicgroup.com

November 16, 2015

The Wolf’s Man – An Interview with Hubert Sumlin On His Birthday

Today would have been Hubert Sumlin’s 84th birthday. The great guitarist passed away on December 4, 2011 at age 80. He was one of my favorite guitarists- and also one of the all time great guys, as I learned when I interviewed him for Guitar World in 1994.

Today would have been Hubert Sumlin’s 84th birthday. The great guitarist passed away on December 4, 2011 at age 80. He was one of my favorite guitarists- and also one of the all time great guys, as I learned when I interviewed him for Guitar World in 1994.

Before I ventured uptown to a Manhattan club to interview him, there was no way I could have grasped the warmth, humor and deeply entrenched good-time vibe given off by the guitarist whose pithy, perfectly placed lines put much of the sting into the great Howlin’ Wolf’s most famous sides with Chess Records –easily some of the greatest blues ever recorded.

Walking into the “dressing room” at Manny’s Car Wash, the Manhattan club where Sumlin was performing, and where we were supposed to do an interview, I was immediately surrounded by a dozen or so bodies crammed tight into the tiny room. Most of the occupants were white and in their 20’s, like me, which is to say a different race and some four decades younger than their host, who was holding court with a crooked grin pasted across his face.

I introduced myself, but rather than commencing an official interview, I was swept up into his orbit, and became another party guest. A beer was placed in my hand and we started talking, with my tape recorder rolling. But the tiny room was directly behind the stage, where an opening band was making it hard to hear one another, and was surely obscuring our conversation on the tape. The situation wasn’t helped by the party going on all around us. We chatted until Hubert performed a strong if sloppy first set, then resumed on his break. It was then, I believe, that he invited me back to his room after the show to finish the interview, an offer I accepted. I drank beers and watched Hubert perform until he had wrung the last bit of vibrato out of his purple ESP guitar for the night, which was, of course, actually early the next morning.

At that point, I had had a great night, but was still far from accomplishing my mission. I had filled a 90-minute tape with our rambling, noisy conversations, but I had no idea what was actually on there. As I waited for him to load up so we could go back to his room and finish the interview, I noticed that most of his partying dressing room guests were still hanging around. I started to get a little nervous as I realized that they may well be accompanying us back to Hubert’s room, where I had hoped to have a quiet, one-on-one conversation.

As we headed back to his room, in a relatively cheap and seedy west side Manhattan hotel, we were indeed accompanied by a couple of young blueshounds, including one hippie kid I recognized as a busboy from the Lone Star Roadhouse, at the time still New York’s best roots music venue. This was Rob, Hubert’s “adopted son,” and constant protector.

Back at the room, Hubert had cans of Spam and sardines sitting around. Sitting on the couch was a beat-up hat box held together by duct tape, in which he transported his crisp, beautiful stage Fedora. Once we started talking, Rob and the others sat on the floor, rapt with Hubert’s still sharp memories about his days helping make the music of one of America’s greatest performers even greater. It was a role he relished. Throughout the long, early morning conversation, Hubert never lost his good nature or his mischievous, impish grin. He really was just as nice as his guitar lines were nasty.

We talked the night away and by the time I climbed into a cab to head home, dawn was approaching. I barely had time to get a few hours’ sleep and a shower before grabbing a cup of coffee and heading into work. Everything was a little fuzzy that day, and I wasn’t sure the whole night had really even happened as I had remembered it; it was one of those experiences that is extremely vivid while it’s occurring, but as soon as it’s over, it feels like a dream or hallucination. But a day or two later, I started transcribing my tapes, and they were even better than I had hoped. Here is the entire story:

Hubert with Wolf

Hubert Sumlin: The Wolf’s Man

Hubert Sumlin is one of the greatest and most influential of the Chicago blues guitarists. From the time he joined the legendary Howlin’ Wolf’s band in 1954 until the singer’s death in 1976, Sumlin played a central role in crafting some of the most memorable electric blues ever recorded. His economical, stinging fills, unusual rhythmic approach and perfectly placed bent notes are integral to classics like “Spoonful,” “Smokestack Lightnin’,” “Killing Floor” and “The Red Rooster.” The recently released Howlin’ Wolf Chess Box, a 71-song collection, is as much a tribute to Sumlin as it is to his immortal boss.

Sumlin’s playing had a particular impact on those rock guitarists who cut and bloodied their teeth on Howlin’ Wolf tunes: Jimi Hendrix, who often covered “Killing Floor”; Keith Richards and The Rolling Stones, who continue to play “The Red Rooster”; Robby Krieger, who helped The Doors remake “Back Door Man”; Stevie Ray Vaughan, who took Sumlin’s signature glissandos and made them a staple of his own bag of tricks, and who paid the blues man explicit tribute on “May I Have A Talk With You,” [The Sky Is Crying]; and Page, Clapton and Beck, all of whom flattered Sumlin by imitating him on “Spoonful” and “Smokestack Lightnin.’”

Sumlin backed Howlin’ Wolf for 23 years, a stretch broken only by six months in 1956 when he worked for Wolf’s arch-rival, Muddy Waters. After Wolf’s death, Sumlin launched his long-delayed solo career, becoming a Chicago blues club fixture and making occasional festival appearances. Over the past five years, however, he has picked up steam, touring often and recording three albums: 1986’s Blues Party (Black Top), 1988’s Heart And Soul (Blind Pig) and 1990’s excellent Healing Feeling (Black Top). Sumlin seems to truly enjoy performing, grinning broadly as he roams a small New York stage, his purple ESP Strat – a gift from Buddy Guy – held in place by a red and white music-note strap – a gift from Stevie Ray Vaughan.

ALAN PAUL: Did Howlin’ Wolf explicitly tell you what to play?

HUBERT SUMLIN: Not really. When I first got with him, he told me that I wasn’t ready to play his music, so I should go home and think about it for a day, a week, a month or a year, whatever it took. “Come back when you’re ready,” he said. “When you figure out how to play my stuff, then you’re hired.” I went home and prayed and slept with my guitar under my pillow trying to figure something out, because I knew that this man was serious – Wolf did not bullshit.

I had played with a pick for eight or nine years, and I couldn’t put it down. Then I woke up one morning and started playing without a pick, and the first thing I thought of was “Smokestack Lightnin.’” I played it better than I ever had and realized, “I don’t need no pick. I don’t need anything but my fingers.” And that was it.

AP: Everything fell into place when you got rid of the pick.

SUMLIN: Exactly. I started playing with a lot more soul. I never used a pick again – that was my secret to unlocking everything. My tone, my sound, everything happened right then. People can’t understand how I play – the average guitar player don’t know what I’m doing. But it’s my thing. It’s what God gave me; I don’t need a pick, because I got five fingers – how can one pick compete?

AP: One unusual aspect of your style is that you don’t play a lot of chords.

SUMLIN: No, I don’t, but I play a lot of tricks. Like Muddy Waters once said, I’ve got a lot of gimmicks up my sleeves. I know when to get in and when to get out. Lots of guitarists just miss out on that aspect of playing. I know how and where to put it, which is what it’s all about.

AP: Did many of your personal playing trademarks develop as a result of playing with Howlin’ Wolf for so long?

SUMLIN: Yes and no. I also played with Muddy Waters for six months and, Lord, I learned a lot from Jimmy Rogers [Water’s lead guitarist]. I picked up from every guitarist I ever worked with. I’d take a note from here and a note from here, a lick from him and a lick from him, and put it all together – that’s the Hubert Sumlin style. And that’s what I would recommend any guitarist do – listen to players you like and pick things up from everyone and everywhere.

You have to learn how to use your instrument to its fullest. You got five different E’s, you got five different A’s, and you got to use them all. If you’re all over the neck, you’re better. That’s why I never used a clamp [capo] like Muddy or Albert Collins or Jimmy Rogers: Why limit yourself? You’ll notice that kids coming up today play great, and they don’t use a clamp. Because they’ve got better knowledge of the instrument. AP: There’s one element of your background that’s almost unique among bluesmen: you studied guitar at The Chicago Conservatory Of Music. What was the extent of your formal training?

AP: There’s one element of your background that’s almost unique among bluesmen: you studied guitar at The Chicago Conservatory Of Music. What was the extent of your formal training?

SUMLIN: I studied for six months with this old guy who was with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was the first time I ever saw a dude who played both opera and blues on his guitar. It had a huge impact on me, because I didn’t know the piano keyboard and I didn’t know how to read – I didn’t know an F from an A, an A from a B or a B from a C. That guy showed me so much in just six months.

AP: Even though you always played electric guitar with Wolf, your sound often had a bit of a country blues vibe. Is that where you come from, musically?

SUMLIN: Actually, when I was a kid I wanted to be a jazz player like Charlie Christian more than anything. But I also loved and heard the blues. They were all around me, and at a certain point, I realized how great all these dudes I listened to were: Charley Patton, Lonnie Johnson, Robert Johnson, all those guys. Peetie Wheatstraw, the “devil’s son-in-law”: Jesus, man, he was something. Then when I got with Wolf and Muddy I realized that they actually played with these guys, and that blew my mind. I’ll never forget my old 78 of Charlie Patton. He was a wizard, man, a genius. I tried to ask Wolf about him and he said , “Aw, you young punk, you’re too young to understand.” It always hurt me that I missed out on seeing and playing with those old guys, because they wrote the book that Wolf and Muddy electrified and expanded. If Wolf and Muddy were the fathers of rock and roll, then those acoustic guys were the granddaddies.

AP: It sounds like Wolf was very conscious of the age difference between you two.

SUMLIN: Yeah. He told me one time, a couple of years before he died, that he was “40 years too early.” He said, “I plowed mules barefoot in December, with snow on the ground, the dirt frozen as a rock.” I said, “Don’t lie, man.” And he said, “I’m not lying. I’m 40 years too early. Things are getting better all the time.” The next year he got sick and went on a kidney dialysis machine.

AP: It can be said that you are the link between the Delta bluesmen and rock and roll. On the one hand, you played with Wolf, who was a contemporary of Robert Johnson and the other guys you mentioned. At the same time, you also exerted a huge influence on the next generation – rock guitarists who weren’t really all that much younger than you.

SUMLIN: I’m very proud of that, and I got to meet those guys. I met Eric Clapton in 1970 when I played on Wolf’s London Sessions [Chess]. I wasn’t supposed to be there, but Clapton said, “If Hubert’s not there, I don’t record.” Then Wolf said he couldn’t record without me, so they had to bring me. Wolf was on a dialysis machine right in the studio, with doctors tending him night and day. He was so sick that on a couple of nights, we didn’t even record. We just sat in the studio and got high. Mick Jagger and Bill Wyman came in and we partied all night long, man. The cleaning lady came in the next morning and everyone was laying there on the floor. Mick Jagger had his head up inside the bass drum. [laughs] It was wild. We had a ball.

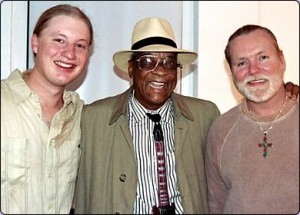

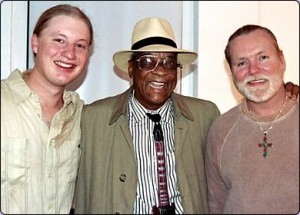

Hubert with Derek Trucks and Gregg Allman

AP: Did you spend much time with Clapton?

SUMLIN: Yes. One day, Eric sent a limousine for me, and we drove for 30 or 40 miles outside of London to his big old mansion in the country. A gorgeous place, like a castle. We had a beautiful dinner, then he took me down to the basement, where he had all these guitars. It looked like a factory – three-and-a-half walls of a room lined with every kind of guitar you can imagine.

He said, “Pick out a couple of those guitars, Hubert. I’m giving you two of them.” I walked all the way around the room, looking at every one of them. Then I saw this case sitting in the middle of the room. I sat down on the floor and said , “What’s in there?” He said, “It ain’t nothing, man.” I asked if I could take a look. He said. “You don’t want that.” I opened the case and took out this beautiful Fender Stratocaster and started playing it there, sitting on the floor.

He said, “Hey, man, I told you to pick any two you want from those that are up against the wall.” I said, “I know, but this Fender sure sounds good. Is it your regular?” He said, “It sure is.” I said, “I knew it, because that’s the one.” He said, “You mean to say you’re going to take it from me, man?” I said, “No, I can’t do it. I don’t want none of these.” He said, “Take it, man. At least I know it’s got a good home. Just promise me that if I ever want it back you’ll give it to me.”

I kept it for two years and hardly ever played it. Then we were both at the Montreaux Jazz Festival, and I brought it over to him. He asked me how much money I wanted, if there was anything I needed. I said, “Nothing man, it’s your guitar. Don’t embarrass me.” He just gave me a hug. He’s a nice guy, a beautiful guy.

AP: Did you have any sense that you were making history when you recorded those classic tracks with Wolf?

SUMLIN: No, and I really didn’t care. But I knew that he was going to be one of the greats. And I was so devoted that I wanted to push him to the top. When you’re recording for people the caliber of Howlin’ Wolf, you’re going to do your best. And in those days, there wasn’t even a question, man: you were going to play your guts out. There had been some days in the past when my stomach ached from not having anything to eat. When I recorded, I would remember those days, and remember how I never wanted to go back to them – and I would play!

AP: What kind of personal relationship did you have with Wolf?

SUMLIN: We were like father and son, although we had some tremendous fights. he knocked my teeth out, and I knocked his out. None of it mattered; we always got right back together.

AP: You fought with Wolf? He was a huge man.

SUMLIN: Oh man, he was big – he could wrap one of his fingers around my guitar neck three times. One time after a gig, we were loading up the truck and I wasn’t there, because I’d run off with this cute girl who’d been sitting on my amplifier, smiling at me all night long. When I got back they were just finishing loading, and Wolf was standing on top of the stage. He started yelling at me, calling me every name you ever heard – and some you couldn’t imagine – because he had to load my gear. I was embarrassed, man, because this was right in front of the whole band.

So I thought, “He can’t do this to me. He can’t humiliate me.” So I waited until he was looking the other way, and I hit him in the face as hard as I could. He didn’t move. He just turned back real slow and slapped me with the back of his hand. I fell and rolled down the ramp that was pushed up to the stage to load the amps. I got up and walked back, screaming at him. When I got to the top he did the same thing again, and I rolled right back down, spitting out teeth.

AP: Is that why you left to play with Muddy Waters?

SUMLIN: No. Me and Wolf patched it up right away. In fact, the next morning, my wife woke me up and said that Wolf had been sitting in his car in front of my house all night long. I went out there and he apologized, and gave me money to fix my mouth.

I left to play with Muddy because he tripled my salary. They were rivals, and Muddy wanted to take me away from Wolf.

AP: Was the rivalry between Wolf and Muddy apparent to everybody?

SUMLIN: Sure. They were jealous of one another; they were enemies: “You stole my shit.” “You did this.” “You did that.” It was endless because they were the two biggest dudes in Chicago, and they were always arguing and competing about who was number one. [laughs] I’ll never forget the day we played the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, and Wolf and Muddy sat down and talked and made friends. They shook hands and said, “No more enemies.” That thrilled me so much, I went and got a beer. This is a business which we do every day and love to death, and I never understood that jealousy. It’s music. Who cares who’s the best?

AP: What are your memories of Jimi Hendrix?

SUMLIN: He was just a little ol’ dude living in England. It was before his band, the Experience, hit it big. We played in Liverpool, the Beatles’ home, and in walked Jimi Hendrix, a little ol’ hip guy wearing earings and a bandanna. Wolf said, “What the fuck is this guy? I ain’t saying nothing to that motherfucker.” He came right up to Wolf and asked if he could play his guitar. Wolf nodded and Hendrix picked it up, turned it over and played it with his teeth. [laughs] He played the hell out of it. Wolf looked at him, big-eyed, and said, “You hired, man, you hired!” He said, “No, thank you Mr. Wolf. But I admire you and the blues. You guys are 100 percent. Beautiful, man.”

I never played with him after that, but I saw him do his thing in New York, after he hit, and I fell in love. The guy was great! Just a little ol’ skinny youngster. He was in his twenties, but he looked 16 or 17, and he was good, man. I mean, really good.

AP: Hendrix often called you a big influence. Your playing on several tracks from the Fifties represents some of the earliest instances of guitarist using distortion. How did you do that?

SUMLIN: I was just using my Gibson and my Wabash amp, which I used for a long time. It was one of the first amps to have 15-inch speakers. I also got an Echoplex right when they came out, and combined with those 15-inch speakers, that made “distortion.”

AP: What sort of Gibson did you play?

SUMLIN: A Les Paul – I believe it was a ‘56. I often played them. I also had a Kay guitar. For four years, Wolf didn’t have a piano or even a bass – just two guitars and drums, so Jody Williams [Wolf’s second guitarist] and I coordinated our parts closely and decided that we would both play Kays. I didn’t like that Les Paul all that much, but I sure do wish that I had it now. [laughs]

The Wolfâs Man â An Interview with Hubert Sumlin On His Birthday

Today would have been Hubert Sumlin’s 84th birthday. The great guitarist passed away on December 4, 2011 at age 80. He was one of my favorite guitarists- and also one of the all time great guys, as I learned when I interviewed him for Guitar World in 1994.

Today would have been Hubert Sumlin’s 84th birthday. The great guitarist passed away on December 4, 2011 at age 80. He was one of my favorite guitarists- and also one of the all time great guys, as I learned when I interviewed him for Guitar World in 1994.

Before I ventured uptown to a Manhattan club to interview him, there was no way I could have grasped the warmth, humor and deeply entrenched good-time vibe given off by the guitarist whose pithy, perfectly placed lines put much of the sting into the great Howlinâ Wolfâs most famous sides with Chess Records –easily some of the greatest blues ever recorded.

Walking into the âdressing roomâ at Mannyâs Car Wash, the Manhattan club where Sumlin was performing, and where we were supposed to do an interview, I was immediately surrounded by a dozen or so bodies crammed tight into the tiny room. Most of the occupants were white and in their 20âs, like me, which is to say a different race and some four decades younger than their host, who was holding court with a crooked grin pasted across his face.

I introduced myself, but rather than commencing an official interview, I was swept up into his orbit, and became another party guest. A beer was placed in my hand and we started talking, with my tape recorder rolling. But the tiny room was directly behind the stage, where an opening band was making it hard to hear one another, and was surely obscuring our conversation on the tape. The situation wasnât helped by the party going on all around us. We chatted until Hubert performed a strong if sloppy first set, then resumed on his break. It was then, I believe, that he invited me back to his room after the show to finish the interview, an offer I accepted. I drank beers and watched Hubert perform until he had wrung the last bit of vibrato out of his purple ESP guitar for the night, which was, of course, actually early the next morning.

At that point, I had had a great night, but was still far from accomplishing my mission. I had filled a 90-minute tape with our rambling, noisy conversations, but I had no idea what was actually on there. As I waited for him to load up so we could go back to his room and finish the interview, I noticed that most of his partying dressing room guests were still hanging around. I started to get a little nervous as I realized that they may well be accompanying us back to Hubertâs room, where I had hoped to have a quiet, one-on-one conversation.

As we headed back to his room, in a relatively cheap and seedy west side Manhattan hotel, we were indeed accompanied by a couple of young blueshounds, including one hippie kid I recognized as a busboy from the Lone Star Roadhouse, at the time still New Yorkâs best roots music venue. This was Rob, Hubertâs âadopted son,â and constant protector.

Back at the room, Hubert had cans of Spam and sardines sitting around. Sitting on the couch was a beat-up hat box held together by duct tape, in which he transported his crisp, beautiful stage Fedora. Once we started talking, Rob and the others sat on the floor, rapt with Hubertâs still sharp memories about his days helping make the music of one of Americaâs greatest performers even greater. It was a role he relished. Throughout the long, early morning conversation, Hubert never lost his good nature or his mischievous, impish grin. He really was just as nice as his guitar lines were nasty.

We talked the night away and by the time I climbed into a cab to head home, dawn was approaching. I barely had time to get a few hoursâ sleep and a shower before grabbing a cup of coffee and heading into work. Everything was a little fuzzy that day, and I wasnât sure the whole night had really even happened as I had remembered it; it was one of those experiences that is extremely vivid while itâs occurring, but as soon as itâs over, it feels like a dream or hallucination. But a day or two later, I started transcribing my tapes, and they were even better than I had hoped. Here is the entire story:

Hubert with Wolf

Hubert Sumlin: The Wolfâs Man

Hubert Sumlin is one of the greatest and most influential of the Chicago blues guitarists. From the time he joined the legendary Howlinâ Wolfâs band in 1954 until the singerâs death in 1976, Sumlin played a central role in crafting some of the most memorable electric blues ever recorded. His economical, stinging fills, unusual rhythmic approach and perfectly placed bent notes are integral to classics like âSpoonful,â âSmokestack Lightninâ,â âKilling Floorâ and âThe Red Rooster.â The recently released Howlinâ Wolf Chess Box, a 71-song collection, is as much a tribute to Sumlin as it is to his immortal boss.

Sumlinâs playing had a particular impact on those rock guitarists who cut and bloodied their teeth on Howlinâ Wolf tunes: Jimi Hendrix, who often covered âKilling Floorâ; Keith Richards and The Rolling Stones, who continue to play âThe Red Roosterâ; Robby Krieger, who helped The Doors remake âBack Door Manâ; Stevie Ray Vaughan, who took Sumlinâs signature glissandos and made them a staple of his own bag of tricks, and who paid the blues man explicit tribute on âMay I Have A Talk With You,â [The Sky Is Crying]; and Page, Clapton and Beck, all of whom flattered Sumlin by imitating him on âSpoonfulâ and âSmokestack Lightnin.ââ

Sumlin backed Howlinâ Wolf for 23 years, a stretch broken only by six months in 1956 when he worked for Wolfâs arch-rival, Muddy Waters. After Wolfâs death, Sumlin launched his long-delayed solo career, becoming a Chicago blues club fixture and making occasional festival appearances. Over the past five years, however, he has picked up steam, touring often and recording three albums: 1986âs Blues Party (Black Top), 1988âs Heart And Soul (Blind Pig) and 1990âs excellent Healing Feeling (Black Top). Sumlin seems to truly enjoy performing, grinning broadly as he roams a small New York stage, his purple ESP Strat – a gift from Buddy Guy – held in place by a red and white music-note strap – a gift from Stevie Ray Vaughan.

ALAN PAUL: Did Howlinâ Wolf explicitly tell you what to play?

HUBERT SUMLIN: Not really. When I first got with him, he told me that I wasnât ready to play his music, so I should go home and think about it for a day, a week, a month or a year, whatever it took. âCome back when youâre ready,â he said. âWhen you figure out how to play my stuff, then youâre hired.â I went home and prayed and slept with my guitar under my pillow trying to figure something out, because I knew that this man was serious – Wolf did not bullshit.

I had played with a pick for eight or nine years, and I couldnât put it down. Then I woke up one morning and started playing without a pick, and the first thing I thought of was âSmokestack Lightnin.ââ I played it better than I ever had and realized, âI donât need no pick. I donât need anything but my fingers.â And that was it.

AP: Everything fell into place when you got rid of the pick.

SUMLIN: Exactly. I started playing with a lot more soul. I never used a pick again – that was my secret to unlocking everything. My tone, my sound, everything happened right then. People canât understand how I play – the average guitar player donât know what Iâm doing. But itâs my thing. Itâs what God gave me; I donât need a pick, because I got five fingers – how can one pick compete?

AP: One unusual aspect of your style is that you donât play a lot of chords.

SUMLIN: No, I donât, but I play a lot of tricks. Like Muddy Waters once said, Iâve got a lot of gimmicks up my sleeves. I know when to get in and when to get out. Lots of guitarists just miss out on that aspect of playing. I know how and where to put it, which is what itâs all about.

AP: Did many of your personal playing trademarks develop as a result of playing with Howlinâ Wolf for so long?

SUMLIN: Yes and no. I also played with Muddy Waters for six months and, Lord, I learned a lot from Jimmy Rogers [Waterâs lead guitarist]. I picked up from every guitarist I ever worked with. Iâd take a note from here and a note from here, a lick from him and a lick from him, and put it all together – thatâs the Hubert Sumlin style. And thatâs what I would recommend any guitarist do – listen to players you like and pick things up from everyone and everywhere.

You have to learn how to use your instrument to its fullest. You got five different Eâs, you got five different Aâs, and you got to use them all. If youâre all over the neck, youâre better. Thatâs why I never used a clamp [capo] like Muddy or Albert Collins or Jimmy Rogers: Why limit yourself? Youâll notice that kids coming up today play great, and they donât use a clamp. Because theyâve got better knowledge of the instrument. AP: Thereâs one element of your background thatâs almost unique among bluesmen: you studied guitar at The Chicago Conservatory Of Music. What was the extent of your formal training?

AP: Thereâs one element of your background thatâs almost unique among bluesmen: you studied guitar at The Chicago Conservatory Of Music. What was the extent of your formal training?

SUMLIN: I studied for six months with this old guy who was with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was the first time I ever saw a dude who played both opera and blues on his guitar. It had a huge impact on me, because I didnât know the piano keyboard and I didnât know how to read – I didnât know an F from an A, an A from a B or a B from a C. That guy showed me so much in just six months.

AP: Even though you always played electric guitar with Wolf, your sound often had a bit of a country blues vibe. Is that where you come from, musically?

SUMLIN: Actually, when I was a kid I wanted to be a jazz player like Charlie Christian more than anything. But I also loved and heard the blues. They were all around me, and at a certain point, I realized how great all these dudes I listened to were: Charley Patton, Lonnie Johnson, Robert Johnson, all those guys. Peetie Wheatstraw, the âdevilâs son-in-lawâ: Jesus, man, he was something. Then when I got with Wolf and Muddy I realized that they actually played with these guys, and that blew my mind. Iâll never forget my old 78 of Charlie Patton. He was a wizard, man, a genius. I tried to ask Wolf about him and he said , âAw, you young punk, youâre too young to understand.â It always hurt me that I missed out on seeing and playing with those old guys, because they wrote the book that Wolf and Muddy electrified and expanded. If Wolf and Muddy were the fathers of rock and roll, then those acoustic guys were the granddaddies.

AP: It sounds like Wolf was very conscious of the age difference between you two.

SUMLIN: Yeah. He told me one time, a couple of years before he died, that he was â40 years too early.â He said, âI plowed mules barefoot in December, with snow on the ground, the dirt frozen as a rock.â I said, âDonât lie, man.â And he said, âIâm not lying. Iâm 40 years too early. Things are getting better all the time.â The next year he got sick and went on a kidney dialysis machine.

AP: It can be said that you are the link between the Delta bluesmen and rock and roll. On the one hand, you played with Wolf, who was a contemporary of Robert Johnson and the other guys you mentioned. At the same time, you also exerted a huge influence on the next generation – rock guitarists who werenât really all that much younger than you.

SUMLIN: Iâm very proud of that, and I got to meet those guys. I met Eric Clapton in 1970 when I played on Wolfâs London Sessions [Chess]. I wasnât supposed to be there, but Clapton said, âIf Hubertâs not there, I donât record.â Then Wolf said he couldnât record without me, so they had to bring me. Wolf was on a dialysis machine right in the studio, with doctors tending him night and day. He was so sick that on a couple of nights, we didnât even record. We just sat in the studio and got high. Mick Jagger and Bill Wyman came in and we partied all night long, man. The cleaning lady came in the next morning and everyone was laying there on the floor. Mick Jagger had his head up inside the bass drum. [laughs] It was wild. We had a ball.

Hubert with Derek Trucks and Gregg Allman

AP: Did you spend much time with Clapton?

SUMLIN: Yes. One day, Eric sent a limousine for me, and we drove for 30 or 40 miles outside of London to his big old mansion in the country. A gorgeous place, like a castle. We had a beautiful dinner, then he took me down to the basement, where he had all these guitars. It looked like a factory – three-and-a-half walls of a room lined with every kind of guitar you can imagine.

He said, âPick out a couple of those guitars, Hubert. Iâm giving you two of them.â I walked all the way around the room, looking at every one of them. Then I saw this case sitting in the middle of the room. I sat down on the floor and said , âWhatâs in there?â He said, âIt ainât nothing, man.â I asked if I could take a look. He said. âYou donât want that.â I opened the case and took out this beautiful Fender Stratocaster and started playing it there, sitting on the floor.

He said, âHey, man, I told you to pick any two you want from those that are up against the wall.â I said, âI know, but this Fender sure sounds good. Is it your regular?â He said, âIt sure is.â I said, âI knew it, because thatâs the one.â He said, âYou mean to say youâre going to take it from me, man?â I said, âNo, I canât do it. I donât want none of these.â He said, âTake it, man. At least I know itâs got a good home. Just promise me that if I ever want it back youâll give it to me.â

I kept it for two years and hardly ever played it. Then we were both at the Montreaux Jazz Festival, and I brought it over to him. He asked me how much money I wanted, if there was anything I needed. I said, âNothing man, itâs your guitar. Donât embarrass me.â He just gave me a hug. Heâs a nice guy, a beautiful guy.

AP: Did you have any sense that you were making history when you recorded those classic tracks with Wolf?

SUMLIN: No, and I really didnât care. But I knew that he was going to be one of the greats. And I was so devoted that I wanted to push him to the top. When youâre recording for people the caliber of Howlinâ Wolf, youâre going to do your best. And in those days, there wasnât even a question, man: you were going to play your guts out. There had been some days in the past when my stomach ached from not having anything to eat. When I recorded, I would remember those days, and remember how I never wanted to go back to them – and I would play!

AP: What kind of personal relationship did you have with Wolf?

SUMLIN: We were like father and son, although we had some tremendous fights. he knocked my teeth out, and I knocked his out. None of it mattered; we always got right back together.

AP: You fought with Wolf? He was a huge man.

SUMLIN: Oh man, he was big – he could wrap one of his fingers around my guitar neck three times. One time after a gig, we were loading up the truck and I wasnât there, because Iâd run off with this cute girl whoâd been sitting on my amplifier, smiling at me all night long. When I got back they were just finishing loading, and Wolf was standing on top of the stage. He started yelling at me, calling me every name you ever heard – and some you couldnât imagine – because he had to load my gear. I was embarrassed, man, because this was right in front of the whole band.

So I thought, âHe canât do this to me. He canât humiliate me.â So I waited until he was looking the other way, and I hit him in the face as hard as I could. He didnât move. He just turned back real slow and slapped me with the back of his hand. I fell and rolled down the ramp that was pushed up to the stage to load the amps. I got up and walked back, screaming at him. When I got to the top he did the same thing again, and I rolled right back down, spitting out teeth.

AP: Is that why you left to play with Muddy Waters?

SUMLIN: No. Me and Wolf patched it up right away. In fact, the next morning, my wife woke me up and said that Wolf had been sitting in his car in front of my house all night long. I went out there and he apologized, and gave me money to fix my mouth.

I left to play with Muddy because he tripled my salary. They were rivals, and Muddy wanted to take me away from Wolf.

AP: Was the rivalry between Wolf and Muddy apparent to everybody?

SUMLIN: Sure. They were jealous of one another; they were enemies: âYou stole my shit.â âYou did this.â âYou did that.â It was endless because they were the two biggest dudes in Chicago, and they were always arguing and competing about who was number one. [laughs] Iâll never forget the day we played the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, and Wolf and Muddy sat down and talked and made friends. They shook hands and said, âNo more enemies.â That thrilled me so much, I went and got a beer. This is a business which we do every day and love to death, and I never understood that jealousy. Itâs music. Who cares whoâs the best?

AP: What are your memories of Jimi Hendrix?

SUMLIN: He was just a little olâ dude living in England. It was before his band, the Experience, hit it big. We played in Liverpool, the Beatlesâ home, and in walked Jimi Hendrix, a little olâ hip guy wearing earings and a bandanna. Wolf said, âWhat the fuck is this guy? I ainât saying nothing to that motherfucker.â He came right up to Wolf and asked if he could play his guitar. Wolf nodded and Hendrix picked it up, turned it over and played it with his teeth. [laughs] He played the hell out of it. Wolf looked at him, big-eyed, and said, âYou hired, man, you hired!â He said, âNo, thank you Mr. Wolf. But I admire you and the blues. You guys are 100 percent. Beautiful, man.â

I never played with him after that, but I saw him do his thing in New York, after he hit, and I fell in love. The guy was great! Just a little olâ skinny youngster. He was in his twenties, but he looked 16 or 17, and he was good, man. I mean, really good.

AP: Hendrix often called you a big influence. Your playing on several tracks from the Fifties represents some of the earliest instances of guitarist using distortion. How did you do that?

SUMLIN: I was just using my Gibson and my Wabash amp, which I used for a long time. It was one of the first amps to have 15-inch speakers. I also got an Echoplex right when they came out, and combined with those 15-inch speakers, that made âdistortion.â

AP: What sort of Gibson did you play?

SUMLIN: A Les Paul – I believe it was a â56. I often played them. I also had a Kay guitar. For four years, Wolf didnât have a piano or even a bass – just two guitars and drums, so Jody Williams [Wolfâs second guitarist] and I coordinated our parts closely and decided that we would both play Kays. I didnât like that Les Paul all that much, but I sure do wish that I had it now. [laughs]

November 9, 2015

Live Stream and Photos from Dead & Co @ MSG

Photo – Jay Blakesberg

Live Audio and Video Stream below, as well as great photos from my friends jay and Derek.

You know about out my Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations with the Grateful Dead – right?

Interviews with Phil, Bob, Trey, Hunter, Billy, Warren and more. Costs less than your coffee. Order it now.

VIDEO STREAM – Thanks for the tunes, Amex.

Mayer’s guit

AUDIO STREAM:

Photo – Derek McCabe

Photo – Jay Blakesberg

Photo – Derek McCabe

Photo – Derek McCabe

November 8, 2015

Dead & Co. MSG 11/7/15

Photo – Jay Blakesberg

Hey, you, check out my Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations with the Grateful Dead.

Some thoughts on Dead & Co. at the Garden.

“The wheel is turning & you can’t slow down

You can’t let go and you can’t hold on,

You can’t go back and you can’t stand still,

If the thunder don’t get you then the lightning will.

Won’t you try just a little bit harder,

Couldn’t you try just a little bit more?

Won’t you try just a little bit harder,

Couldn’t you try just a little bit more?”

The wheel keeps turning and they keep trying. Four months after we marked the end of the Core Four Grateful Dead appearances together with triumphant fireworks over Chicago’s soldier Filed, here we were in a sold-out madison Square Garden. While Weir, Kreutzmann and Hart kept Jeff Chimenti and signed up John Mayer and our old friend Oteil Burbridge for anew venture called Dead & Co., Phil Lesh continued to pump away with his Phil & Friends. They were playing at the Capitol Theater 30 Miles north in Portchester, just weeks after Phil announced he was undergoing treatment for bladder cancer.

Think about the above for a minute because it’s really quite amazing. And I don’t think fans at either venue left disappointed.

Dead & Co is really a pretty fascinating venture and I thought it succeeded with flying colors. Oteil and Mayer are bringing a new energy and a slightly different direction to the music. Mayer has his own style and, while he’s clearly embraced and ingested the music of the Dead, he is not shying away form sounding like himself. I think that’s a good thing. There are enough Dead tribute bands out there and we don’t need another one anchored by the real deal. The tunes themselves are so sturdy that they invite reinterpretation and any sincere effort can work. And Weir seemed to be really enjoying the energy radiating out from his right flank. I thought he sang and played at a very high level, and you could really hear his guitar,

Mayer’s guitar alpha and omegas are, I think, Clapton and SRV and that works beautifully for me, though I’m sure some Heads feel otherwise. He helped make “Cold, Rain and Snow” like Backless-era Clapton. In a good way. Oteil dug into the songs and provided stone cool grooves, helping steer jams and nailing complicated passages on songs like “Slipknot” and “The Other One.” It was especially fun to hear him go to town on loping tunes like “Tennessee Jed” and “He’s Gone” where the groove is distinctive but elastic. He and Mayer bought the bad tremendous energy, Chimenti filled in so many holes, often working in tandem with Oteil to play and high and low around the main melody and guitars.

Oteil even joined Billy and Mickey for drums, as he often did with the Allman Brothers. It was great to see him so happy and so engaged. And to hear the music be so strong. I’m looking forward to seeing where this all heads. Seems to me, it’s got some serious legs.

Photo by Derek McCabe

Set 1:

Shakedown Street

I Need a Miracle

Cold Rain and Snow

Tennessee Jed

They Love Each Other

Jack Straw

Set 2:

Help on the Way

Slipknot!

Franklin’s Tower

He’s Gone

St. Stephen

Drums> Space

The Other One

Stella Blue

Not Fade Away

Encore:

Brokedown Palace

October 20, 2015

The story behind “Free Bird”

On this day (October 20) in 1977, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s twin engine plane crashed in a swamp in Gillsburg, Miss., killing three of the band members – singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines and singer Cassie Gaines – assistant manager Dean Kilpatrick and both pilots on impact. Twenty other people survived with various injuries, some very severe.

The last surviving original member still in the band Gary Rossington is recovering at home from a heart attack. Sending him best wishes and also to early members Ed King, Artimus Pyle, Cassie Hawkins, Larry Junstrom….

In tribute to the band and those lost, this is the story of their most enduring song.

Foto by Kirk West

“FREE BIRD”

Originally released on pronounced leh-nerd skin-nerd (MCA, 1973)

Guitarist Allen Collins came up with the music to “Free Bird” very early in the band’s songwriting process. But while everyone recognized the grace of the chord progression, Ronnie Van Zant could not come up with a suitable vocal melody.

Recalls Gary Rossington, “Allen had the chords for the beginning, pretty part for two full years and we kept asking Ronnie to write something and he kept telling us to forget it; he said there were too many chords so he couldn’t find a melody. He thought that he had to change with every chord. Then one day we were at rehearsal and Allen started playing those chords again, and Ronnie said, ‘Those are pretty. Play them again.’ He said, ‘I got it,’ and wrote the lyrics in three or four minutes—the whole damned thing!

Like “Stairway to Heaven,” one of its chief competitors for the unofficial title of rock’s most epic song, “Free Bird” starts out as a ballad before becoming a solo-fueled rocker. That was not by design, recalls Rossington: “When we started playing it in clubs, it was just the slow part. Ronnie said, ‘Why don’t you do something at the end of that so I can take a break for a few minutes.’ I came up with those three chords at the end and Allen and I traded solos and Ronnie kept telling us to make it longer; we were playing three or four sets a night, and he was looking to fill it up and get a break.”

Gary Rossington

The structure of “Free Bird” was set, but it was still lacking one final element; the elegant piano intro, which was written by then-roadie Billy Powell. “One of our roadies told us we should check out this piano part that another roadie had written as an intro for the song,” says Rossington. “We did–and Billy went from being a roadie to a member right then.”

The original album version of the song clocked in at almost 10 minutes and according to Rossington and Ed King, MCA objected to putting such a long song on the band’s debut album. A 3:30 radio edit was cut and the single, at 4:10, became a Top 20 hit. “MCA said we couldn’t put a 10-minute song on an album, because nobody would play it,” recalls King. “Of course, that was the song everyone gravitated towards!”

On Skynyrd’s first live album, 1976’s One More from the Road, Van Zant can be heard asking the crowd, “What song is it you wanna hear?” The overwhelming response leads into the 14-minute version of the song that became iconic. Though Van Zant often dedicated “Free Bird” to Duane Allman, contrary to urban legend, it was not written for him.

The story behind âFree Birdâ

On this day (October 20)  in 1977, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s twin engine plane crashed in a swamp in Gillsburg, Miss., killing three of the band members – singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines and singer Cassie Gaines – assistant manager Dean Kilpatrick and both pilots on impact. Twenty other people survived with various injuries, some very severe.

The last surviving original member still in the band Gary Rossington is recovering at home from a heart attack. Sending him best wishes and also to early members Ed King, Artimus Pyle, Cassie Hawkins, Larry Junstrom….

In tribute to the band and those lost, this is the story of their most enduring song.

Foto by Kirk West

âFREE BIRDâ

Originally released on pronounced leh-nerd skin-nerd (MCA, 1973)

Guitarist Allen Collins came up with the music to âFree Birdâ very early in the bandâs songwriting process. But while everyone recognized the grace of the chord progression, Ronnie Van Zant could not come up with a suitable vocal melody.

Recalls Gary Rossington, âAllen had the chords for the beginning, pretty part for two full years and we kept asking Ronnie to write something and he kept telling us to forget it; he said there were too many chords so he couldnât find a melody. He thought that he had to change with every chord. Then one day we were at rehearsal and Allen started playing those chords again, and Ronnie said, âThose are pretty. Play them again.â He said, âI got it,â and wrote the lyrics in three or four minutesâthe whole damned thing!

Like âStairway to Heaven,â one of its chief competitors for the unofficial title of rockâs most epic song, âFree Birdâ starts out as a ballad before becoming a solo-fueled rocker. That was not by design, recalls Rossington: âWhen we started playing it in clubs, it was just the slow part. Ronnie said, âWhy donât you do something at the end of that so I can take a break for a few minutes.â I came up with those three chords at the end and Allen and I traded solos and Ronnie kept telling us to make it longer; we were playing three or four sets a night, and he was looking to fill it up and get a break.â

Gary Rossington

The structure of âFree Birdâ was set, but it was still lacking one final element; the elegant piano intro, which was written by then-roadie Billy Powell. âOne of our roadies told us we should check out this piano part that another roadie had written as an intro for the song,â says Rossington. âWe did–and Billy went from being a roadie to a member right then.â

The original album version of the song clocked in at almost 10 minutes and according to Rossington and Ed King, MCA objected to putting such a long song on the bandâs debut album. A 3:30 radio edit was cut and the single, at 4:10, became a Top 20 hit. âMCA said we couldnât put a 10-minute song on an album, because nobody would play it,â recalls King. âOf course, that was the song everyone gravitated towards!â

On Skynyrd’s first live album, 1976’s One More from the Road, Van Zant can be heard asking the crowd, “What song is it you wanna hear?” The overwhelming response leads into the 14-minute version of the song that became iconic. Though Van Zant often dedicated âFree Birdâ to Duane Allman, contrary to urban legend, it was not written for him.

October 16, 2015

Today is Bob Weir’s 68th birthday. Happy birthday Bob.

T...

Today is Bob Weir’s 68th birthday. Happy birthday Bob.

This interview appears in my Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead, along with similarly extensive interview with Phil, Phil and Trey, Robert Hunter, Bill Kreutzmann, Warren Haynes, Mark Karan and Steve Kimock. It costs less than a latte. Check it out!

A couple of notes: I spent a lot of time with Bobby down in Philly on this afternoon and really enjoyed talking with him. He was gracious, relaxed and easy to be with. We did most of the interview in his hotel room, but also hung out quite a bit at the show.

Just before this – I think even the night before — we also hung out at the Jammies for a good while. They were at Roseland that year, and I actually presented an award. Wish I could remember what it was or to whom. Anyhow, we chilled in his dressing room then. And then I also hung out with him in an NYC hotel room as he did a guitar lesson with Andy Aledort that ran with this piece and it was really fascinating to watch/listen to him demonstrate many of his songs and the proper way to play them.

For as long as the Grateful Dead has existed, people have loved to rag on Bobby for a lot of different reasons – some of which are easy to understand, others of which I think are really unfair. But he is a very interesting and different guitar player; he composed a lot of their most intricate and interesting songs, such as “The Other One,” as well as their catchiest tune – “Sugar Magnolia”; and he is a very good hang. Ultimately, only thing matters: he’s the guitarist Jerry wanted playing by his side all those years.

One other editorial note: when you see Bobby discussing Napster and downloading below, this interview was conducted when that was a very hot issue and Metallica was a taking a lot of fire for battling downloading and file sharing.

Kirk West Foto

Top Dog

Former Grateful Dead rhythm guitarist Bob Weir returns to the land of the living with Ratdog, his ever-evolving ârock and roll Dixielandâ band.

by Alan Paul

Outside Philadelphiaâs Electric Factory the wind is whipping on a cold winter night. Shivering ticket scalpers circulate through a parking lot slowly filling with musical pilgrims arriving to see Ratdog, the band led by Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir.

Inside the nearly empty theater, the mood is sedate as soundcheck gets underway. Lead guitarist Mark Karan is showing off his beautiful assortment of instruments, including a vintage Gretsch and Les Paul and gleaming new PRS and Modulus guitars. Drummer Jay Lane is giving his young daughters lessons, with one girl banging the snare drum while another taps the high hat. Keyboardist Jeff Chimenti is eating a slice of pizza and chatting with the techs.

Without uttering so much as a single word, Weir plugs in his custom Modulus guitar, turns up the volume and starts playing a slinky triad riff. Longtime Weir collaborator Rob Wasserman settles down behind his upright electric bass and joins in. Within moments, the guests peel away, the musicians turn serious and the band falls into place, quickly moving into âBury Me Standing,â the lead track of the groupâs debut album, Evening Moods (Grateful Dead Records). And just like that, theyâre off, tearing through a half-hour tune-up for the coming gig. In a few hours, theyâll bring down the house full of aging Deadheads and young jam lovers with their interlocking, ebb and flow improvisations, playing a mix of new material and beloved Grateful Dead standbys.

Those are the moments for which Weir lives, the reason why heâs out here humping it night after night, promoting his new album and whipping his band into shape. He has a beautiful wife and gorgeous two-year-old daughter 3,000 miles away in California and he could be with them, spending his days relaxing in the sun, riding his beloved mountain bike or hiking the wooded trails of Marin County, north of San Francisco. Such are the perks of 30 years spent in the Grateful Dead, a group he helped form when he was just 17 years old.

But Weir is far from ready to give up the ghost. He sees himself as a guitarist. And a guitarist plays guitar, so here he is on a cold East Coast night, pushing ahead with the group that has received most of his passion and effort since the Deadâs 1995 disbanding following Jerry Garciaâs death.

âWe are coming into our own,â says Weir. âWeâre not there yet, but we are learning how to read each otherâs moods and impulses, which is what makes a good band. You need to get to the point where you hear footsteps coming up behind you and know with certainty that someone else is about to pick up the ball and finish your phrase. Thatâs what the Grateful Dead had and I feel it coming in this group.â

Evening Moods is an important album for Weir, the first of his six efforts outside the Dead that really captures his essence. In doing so, it clearly illustrates what he brought his old band. Weir hardly ever played solos, content to spur on Garciaâs crystalline flights of fancy. But he is an extremely interesting and inventive player, rarely playing the consistent, revolving patterns that are the bedrock of most rock rhythm styles. Instead he relies on counterpoint, riffs and non-circular chord progressions. He was also an important songwriter for the Dead, contributing much of the bandâs oddest, most ambitious tunes, like âThe Other One,â âWeather Report Suiteâ and âEstimated Prophet,â as well as âJack Strawâ and âSugar Magnolia.â

All of these tunes can be heard in different versions on the never-ending stream of Grateful Dead live albums, released on both Grateful Dead Records (mail order only, online at www.dead.net) and Arista. There are also plans to digitize the bandâs extensive tape archives to make them available for online downloads, a process said to be causing rifts with bassist Phil Lesh. And, of course, thereâs the ongoing story of Ratdog. Certainly, there is much to discuss with Weir and heâs game to talk about it all, reclining comfortably on a hotel suite couch, barefoot and clad in jeans and polo shirt, hours before the Ratdog gig in Philadelphia.

Your guitar style is extremely original. Who were your primary influences?

Initially country and acoustic blues players, but my dirty little secret is that I learned by trying to imitate a piano, specifically the work of McCoy Tyner in the John Coltrane Quartet. That caught my ear and lit my flame when I was 17. I just loved what he did underneath Coltrane, so I sat with it for a long time and really tried to absorb it. Of course, Jerry was very influenced by horn players, including Coltrane, but I never really explicitly thought about that relationship, because I didnât really ever decide to pattern myself after McCoy Tynerâs piano. It just grabbed me.

Iâve never had much of an idea of what Iâm up to and Iâm not sure that I do even now, but I have always been there to serve the music and believed that if you sincerely do so then your appropriate role will present itself. Then itâs just a matter of finding the perfect place to play that role and Iâm very fortunate that this happened to me at a very young age.

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

One of the hallmarks of your style is that unlike conventional rock and roll rhythm playing, you do not play repetitive patterns.

I think that is partly a result of my dedication to rhythm playing and not really trying to be a soloist. Because Iâm concentrating on just that figure, I can put a little more energy into it and develop it more brightly. Another big reason for me not being repetitive is the influence of Jerry and, even more so, Phil, who never repeats anything. If no one else is repeating anything, Iâll be damned if Iâm going to play the same thing over and over. Besides, itâs not what the music ever wanted. It wants to keep developing and growing and moving, and I really am in service to the music.

Rather than straight chords, you play a lot of figures, riffs and fills that often verge on lead guitar. Iâm thinking, for instance, of your work on âChina Cat Sunflower.â

Right. I always played a lot of counterpoint in support of Jerryâs guitar or vocal melody. But itâs funny that you mentioned âChina Cat Sunflowerâ because thatâs just about the only song where Jerry ever taught me a riff and told me itâs what he wanted to hear. That little arpeggiated lick was his. I do something similar on âScarlet Begonias,â which I came up with. But the concept of the band was always group improvisation, not merely playing behind Jerryâs solos. The Grateful Deadâs m.o. was to play together in a seamless mesh. We coined the term ârock and roll Dixieland,â a phrase we also often use in Ratdog, and that explains a lot because in Dixieland jazz, every instrument plays a crucial role in support of one another. Jerry was quite a lead guitarist but he also often chugged away in support of what someone else was doing. But people focused so much on his leads they often missed that, and frankly he was so far up in the mix that fans often thought his support lines and rhythm parts were lead lines.

A lot of your songs have featured unusual timing and odd chord changes. Do those things come naturally to you, or did you say, âI want to use unconventional structures?â

It goes back to the late Sixties when the Beatles studied with the Maharishi and suddenly there was an explosion of Northern Indian classical music in American popular culture. To even begin to appreciate people like Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar you have to be able to count in their time signatures, where they will take, say, 13 and put it against 18. They call them the âtallsâ and itâs nothing I ever expect to master because it is very deep. But even attempting to understand it got me started.