Alan Paul's Blog, page 46

April 19, 2012

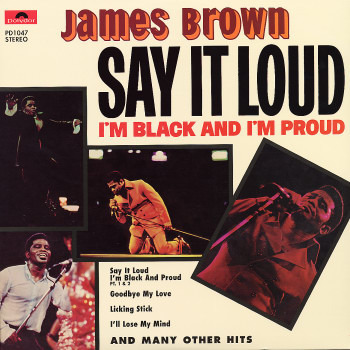

Behind the scenes of James Brown’s “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)”…Yep, I interviewed him.

In 1999, Guitar World devoted an entire issue to the 30th anniversary of 1969, which we proclaimed the greatest year in rock. I wrote the histories of several landmark albums, including James Brown’s “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud).” The best part of the entire project by a long shot was interviewing the great man himself. I am going to try to piece it together and post as a Q-A, but here is the final piece.

Note how entirely ungracious he was towards Jimmy Nolen, his longtime collaborator and the man who really wrote the book on funk guitar. Brutal.

Next up from this 1969 series: The Grateful Dead’s Live/Dead.

*

When James Brown released the single “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” in late ‘68, he was an artist on a roll, with a huge and expanding audience, both black and white, and a steady diet of hits on both the pop and r&b charts. But “Say It Loud,” interpreted by many white listeners as an angry rebuff, was to be his final pop hit.

Today, Brown says that anyone who viewed the song as an angry anthem was way off base. “I was trying to do two things,” says Brown, who recently released I’m Back (Private Music). “One, give the power structure –which in America means the white power structure – a way to understand how we felt, and know that we had people who could do things and just wanted a fair shake. Two, I wanted young black kids to wake up and realize that they should be proud of who they were, get an education and try to make something of themselves. Proud and bad are too different things. I never wanted to separate. My thing was to let the pride be there, and to let people get into the skin of a black man and realize that he only wants to be recognized for the contributions that he has made.

“I was just telling it like it is. Would you rather have someone tell you how they’re feeling to your face, or wait till you turn around and whisper their anger behind your back? You got to swing for the fences every time you’re at bat; you owe it to your children and grandchildren. That’s what I was doing, and I’ve always been about building, not destroying. I was there when Dr. King was assassinated, telling everyone to cool out, trying to remind everyone that you don’t want to destroy your country. You want to build it.”

“I was just telling it like it is. Would you rather have someone tell you how they’re feeling to your face, or wait till you turn around and whisper their anger behind your back? You got to swing for the fences every time you’re at bat; you owe it to your children and grandchildren. That’s what I was doing, and I’ve always been about building, not destroying. I was there when Dr. King was assassinated, telling everyone to cool out, trying to remind everyone that you don’t want to destroy your country. You want to build it.”

Nonetheless, notes Brown expert Harry Weinger, “That record lost him a big audience. From ‘65 to ‘68, he was extremely popular, with his audience getting wider and wider. Then he did this album and lost his white audience, and never had another top 10 single.”

What all these listeners were missing is the fact that whatever his politics, Brown’s music was just getting leaner and meaner, and ever funkier. The album Say It Loud, which was really a collection of singles recorded throughout ’68, also included the impossibly taught “Licking Stick” and the organ-driven instrumental “Shades of Brown.”

“Hey, that was just continuing what I started a few years back when I changed the music from being on the 2 and 4, where it had always been to the 1 and changing the emphasis from the downbeat to the upbeat,” Brown says. “That’s what created funk music – gospel and jazz mixed together by James Brown with a little help from God. And I just kept doing it and innovating it, right on through ‘Say It Loud’ and further.”

The single and most of the album also feature the distinctive sound of Brown’s backing band, the JB’s featuring guitarist Jimmy Nolen, generally credited as a major funk innovator. Brown says Nolen was great, all right, but he really wasn’t all that original. “Sometimes ignorance is bliss,” Brown says. “Jimmy Nolen was a man who could play anything I wanted him to play and didn’t know enough to play anything but what I wanted. And that’s what made him great on ‘Say It Loud’ and everything else.”

April 4, 2012

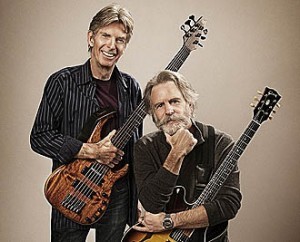

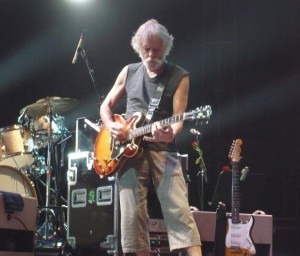

Almost Dead: The Furthur interviews

Almost Dead: The Furthur interviews

Bob Weir and Phil Lesh revive the spirt of the Grateful dead with some serious help from guitarist John Kadlecik and some other young guns.

Phil and Bob by Jay Blakesberg

Originally appeared in Guitar World, March 2012. Reposted here in honor of the Furthur spring tour.

**

Bob Weir and Phil Lesh stand on the broad Madison Square Garden Stage, hunched over their instruments. The musicians, who began playing together as founding members of the Grateful Dead in 1965, look resolute and meditative. They appear to be oblivious to the roar of a sold-out house of rabid fans punching the air and twirling in their seats with delight. With the beatific grins and intense concentration of men lost in prayer, bassist Lesh and guitarist Weir resemble nothing so much as ministers preaching to their dedicated congregation.

They are guiding their band, Furthur, through an intricate passage of “The Eleven,” a complicated Grateful Dead classic that the original group effectively stopped performing in 1970. It is one of many chestnuts resuscitated by Furthur since the group’s 2009 formation. It’s not hard to grasp why Weir and Lesh are so excited about their longest running collaboration since Jerry Garcia’s 1995 death ended the Dead’s long, strange trip.

Guitarist John Kadlecik takes flight, twisting away from the solid foundation held down by Lesh, Weir, drummer Joe Russo and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, eventually touching back down to the song’s riff to rapturous applause. With the three new members’ thorough understanding of the Dead catalog and their high level of musicianship, as well as the subtle addition of two backup singers, Furthur sometimes sounds like a Steely Dan version of the Dead. The band is threading a delicate musical needle, at once sounding more Dead-like and more creatively original than any of the previous post-Garcia formations.

Tearing up ”The Eleven” and hundreds of other Dead classics is second nature to Kadlecik. The 42-year-old guitarist spent 12 years fronting the Dark Star Orchestra, a tribute band specializing in recreating specific performances, from the Dead’s 30-year career. His encyclopedic grasp of the Dead repertoire and Garcia’s playing and tone make him the perfect guy to complement Lesh and Weir’s sturdy, expansive grooves, but he is proving to be much more than a tribute band imitator.

Tearing up ”The Eleven” and hundreds of other Dead classics is second nature to Kadlecik. The 42-year-old guitarist spent 12 years fronting the Dark Star Orchestra, a tribute band specializing in recreating specific performances, from the Dead’s 30-year career. His encyclopedic grasp of the Dead repertoire and Garcia’s playing and tone make him the perfect guy to complement Lesh and Weir’s sturdy, expansive grooves, but he is proving to be much more than a tribute band imitator.

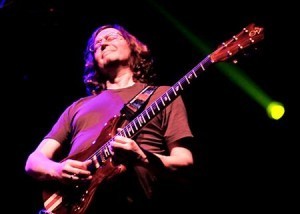

John

Kadlecik is the first guitarist to do for Garcia what Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks have done for Duane Allman – nail the master’s style perfectly so that it can be expanded upon. Without the right amount of skilled mimicry, the material can’t come to life. Without doing more, the songs sound stale. Kadlecik has struck the delicate balance that allows the music to soar, exactly what Lesh and Weir were searching for when they sought a new direction after the Dead’s last tour ended in 2009.

In the 17 years since Garcia’s death, Lesh and Weir have alternated between their own groups (Phil and Friends and Ratdog, respectively) and coming together with drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kruetzman and different guitarists as the Dead. Furthur is their first effort together without the percussionists.

“That last Dead tour reminded Phil and I of how much we enjoy playing together, but feeling like we needed a new venue to do so,” says Weir. “Decades of playing together led us to learn how to intuit each other and know where each other is going. I could get to wherever Phil was going and be there with a little surprise for him. And he could do it for me – and these things can happen in such intuitive ways that it’s just fun. We wanted to take that and run.”

GW: Bob, you and Phil long approached Grateful Dead material by trying to re-imagine rather than recreate it. Did you make a conscious decision to reverse course by bringing in John from the Dark Star Orchestra, a fantastic Dead tribute band?

WEIR: Not really. I understand why it would appear that way, but people told us that John was great, so we had him out to play with us – and as well as he could play the Jerry stuff, it was actually just as important for us to make sure that it wasn’t all he could do. He can play Jerry chapter and verse or go off in new directions and he is certainly not a mimic. He’s fast on his feet, so he can hear what we’re up to, grasp where we’re headed and be there waiting.

Also, I have not made many conscious efforts to “re-imagine” songs. I just let them happen the way they’re going to happen. I always required Ratdog to play any Grateful Dead song we were going to do once very true to a late recording to make sure they understood the source material. Then we let it go where it wanted to go, and we do something similar with Furthur.

GW: John, at your audition, did you get a sense that showing you could not play like Jerry was as important as showing that you could?

KADLECIK: Yes. First, I have to say that I almost missed the whole thing because Bob’s manager sent me an email that ended up in my SPAM folder. By the time I found it, I thought I might have missed the boat. Luckily, I had not and flew out to San Francisco, along with the other guys they were considering…

WEIR: And by the end of the week, it became clear that we had a band. Phil and I felt the fire and were excited to see where we could go.

KADLECIK: They threw mountains of repertoire at us and definitely wanted to see how I would respond to leaving behind what I knew. They needed to see how flexible I would be and wanted to feel out if I was stuck in their old arrangements, which was no big deal to me, because in Dark Star we had five different arrangements of every song. The idea that these songs were not static was not foreign to me.

Bob, with his 335

WEIR:And that’s a key thing to understand: most of these songs did not remain static within the Grateful Dead. We are not really making special efforts to recreate the past with Furthur – at least I don’t think so, but I’m way too far into the forest to be able to see a single tree.

GW: Why did you want to do this without Bill or Mickey? And why not two drummers, whish is a Dead signature?

WEIR: When the four of us are involved, the expectations are different. It just changes in that way. We did start with two drummers, but Jay Lane went back to whence he came – Les Claypool and Primus. It changed the dynamic in a good way. Joe is a very strong and very busy drummer, so we felt no need to start looking for another guy.

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?Servic... Widgets</A>

GW: You have said the last Dead tour “felt like work.” Why was that the case?

WEIR: It just seemed like it was taking a lot of effort to make the Dead work and it was time to look in some different directions. The Grateful Dead was one long, decades-long continuum until Jerry died in 1995. When we reconvened as the Dead, that continuum was missing and so was Jerry. We could go for a while just playing and having fun, and we regrouped with various guitarists and other members, but it became obvious to us that there was something missing.

At that point, we had a choice: either we just stick it out and keep going with it and it’s going to be a lot of work or we can break up in various shards and go new places quicker because we’re bringing new blood into the music. We opted for that. We can dust the Dead off every now and again and take it out and see if anything changes and we will have some fun doing that.

GW: Are you surprised at the overwhelmingly positive response from Deadheads, including some old naysayers who have tsk-tsked every group since Jerry died?

WEIR: I’m not surprised. When we all got together and started playing, we realized we had new places to go. This outfit is a little faster on our feet than previous ones, but to be fair to the Dead it doesn’t come with the same expectations, so we have more room to work. Like I said, that’s the gist of why Phil and I wanted to work together but not in a context of being “The Dead.” We constantly throw curveballs at each other and that’s what we really wanted to do.

KADLECIK: What’s remarkable is the degree to which both Bob and Phil are still really focused on being present in the moment with improvisation. They truly are masters and they will not settle for something being good and sticking with it, or be afraid to try something completely new. It’s very inspiring. It’s easy in live music to get on autopilot and those curveballs Bob talks about are ways of keeping each other away from that. Sometimes any of us might be feeling a little off and we try to prod each other to dig deeper. Sometimes for me that can mean almost going into an internal trance, a prayer to your muse to plead, “Please give me something.” [laughs]

During my early days with the band, we’d get into rehearsing a jam section and we’d stop and talk about breaking out of the style. The more we did that and the more we actually get the collective group vibe happening, it became more and more comfortable to trust. With the DSO I was doing an experiment in restraining my influences to just Garcia – I have a lot of others but I kept them bottled up and now they’re coming out more.

GW: So you actually feel less constrained to sticking with Jerry licks in Furthur than you did in DSO!

KADLECIK: [laughs] Actually, yes. And the longer we play together, the more free it is and the more I get a sense of a look from Bob or Phil that says “change gears.” I’m really wrestling with the dynamic of being thought of as “that Jerry guy” and knowing where to draw the line. That’s sort of the essential challenge. The jamming this music demands is all about balancing two opposing directions. There are infinite varieties, but you’re staying within certain boundaries to create a structure to hang things on.

The other interesting factor is that a lot of what people identify as Garcia licks are actually arrangements or orchestrated two-guitar parts. It’s very much a shoulder-to-shoulder conversation. I may be slightly in front from a melodic standpoint, but it’s really a free-flowing thing and we support each other

GW: Can you give a specific example to illuminate Bob’s overlooked contributions?

KADLECIK: There are many, but a good one is “Scarlet Begonias,” which has really intricate arrangements between Jerry and Bob’s parts. It’s a very unique approach and the deepest roots of the style are in the polyrhythm of African drumming, where five people can play similar sounding things and everyone’s voice is heard. In that kind of setting, it doesn’t hang together if I throw something completely different in there.

There’s a pretty short list of really successful two-guitar teams and Bobby and Jerry are high on it. They came up with some of the best arrangement ideas that ever happened in rock and roll. To my ear, it is hybridized between bluegrass music and Coltrane’s classic quintet arrangements. And there are some songs where Bobby and Jerry’s style dovetails with what Dickey and Duane were doing in the Allman Brothers Band – the ABB’s “Leave My Blues At Home” is a great example.

GW: Bob, you and Phil have such very unique styles that maybe only fully can blossom with one another. With the Grateful Dead, you really created new ways of playing rhythm guitar and bass – and you did it with one another. Are you more relaxed playing with him, in ways that allow you to just drop thinking and play?

WEIR: Hmmm. That’s an interesting thought, actually. I’ll have to say not really because you have to be on your toes and we’re constantly pushing. We’re poised for anything and very confident, but I’m not sure relaxed is the right word, because the beauty of this thing is we’re always trying to push and prod each other in different directions and to new places. I’m part of a bigger picture and hopefully it’s nothing you can think your way through. It’s something you have to feel. We don’t know exactly what we’re going to do next and that’s the fun part.

KADLECIK: Bob and Phil have a very unique, interlocking style and it’s amazing to observe on stage every night. One thing that has been really fun and endlessly interesting has been the experience of writing new material with these guys, which we have been doing since our very first show.

Songwriting is a completely different arc from performance and seeing some very experienced writers and arrangers work has been fantastic. Most of the stuff is brought in with a fairly abstract framework. Sometime we have to try out an arrangement to even know if it’s going to stick. Then it will go back in the oven and all of a sudden there are sections in 6/4 time. Big changes happen: whole sections get thrown out or added to. It’s been incredibly exciting to be in the middle of this process.

GW: Could this material, some of which is being worked on with lyricist Robert Hunter, lead to a Furthur studio album?

WEIR: We do not have any plans to record but I don’t see any reason not to head that way. We’ve got the great facility in my [new] TRI Studio, which has been a gas to put together, even if it has at times freaked out my accountant. I had a couple of good years and had some nickels in my jeans and then the good folks at API Audio offered me a real sweet deal whereby if I would come play their hoedown, they would give me a substantial discount on their top of the line board, with all the bells and whistles. I reacted quite smartly and jumped on a plane.

Then I found a fantastic building built as a studio but heading to a bank sale and got a great deal and the end product of all this is an absolutely sterling facility, with audio and video capability as great as you can get and a mix of large and small rooms, the biggest of which features Meyer Sound Constellation, with 80 speakers on all sides and in the ceiling. We can recreate any kind of acoustic ambiance, from a living room to a stadium and you can reshape any song on the fly. It’s remarkable and is a place where live music can be broadcast on the web in the highest possible quality. You can plug your computer into your home theater system and be inside the band. It’s the most intimate musical experience you can get. You can have a bunch of friends over and go to a concert with no lines or security to deal with. We’re trying to put a stage in everyone’s living room.

GW: The Grateful Dead never had setlists and rehearsed inconsistently. This band has specific setlists for every show and has had extensive rehearsal time. The result is a much more polished sound. Is there as much room in Furthur for spontaneity as there was in the Dead?

WEIR: Of course there is. Rehearsal only makes spontaneity easier and better, but it’s not as different as you and many others think. It’s still complete will of the wind with Furthur and the Dead practiced more than we had a reputation for. Also, we spent so much time on stage that we all knew where we were headed.

We started using setlists in this band because some of the guys needed to bone up on tunes. And our working repertoire now is well over 200, while the Dead ever took out more than 100 at any given point, so it takes some more forethought, but again the Grateful Dead wasn’t operating as completely on the fly as people imagine.

Basically, Jerry and I would plot out the first few songs and then let the set unravel from there. We usually had in mind what we were going to close with and it was a matter of making it all flow. For the second set, we would decide what we were going to close with and anyone could come chat about it during the drum segment and we would sometimes craft concepts.

GW: This is the longest running post-Grateful Dead collaboration. Is it an ongoing band?

WEIR: Oh yeah. I’m not sure we’re going to do four tours a year. Next year we might do three because we don’t want to run ourselves out of gas. But what I’m here to do is play and I think Phil feels that way as well. And we’re really happy with this band we’ve got together here.

April 2, 2012

Stephon Marbury wins a Chinese championship

This is just so cool in so many ways. Video below tells a sweet story. Details here at the indispensable NiuBBall.com.

March 28, 2012

About This American Life, Mike Daisey and Chinese factory workers…

From the NewYorker.com

This whole story about monologist Mike Daisey lying throughout his piece about Apple’s Foxconn factories in China is just awful. This story explains why rather well.

But all you really have to do to understand the whole thing is to listen to This American Life’s retraction, which you can do right here. It is absolutely devastating, and Daisey is reduced to being an inch high. None of his explanations make sense or are defensible. It’s a sad episode in American journalism and the ramifications will continue for a long time. Chinese apologists and nationalists will use it to cast doubts and aspersions on any negative reporting that comes out of the place.

Major kudos to Rob Schmitz at Marketplace for seeing through this phony bit of reporting – and actually acting on it. Many, many veteran Chinese reporters rolled their ideas at the piece, but Schmitz set about dismantling it.

I thought that the smartest thing Daisey says in the whole piece is: “I don’t know if this is a smart thing to be telling you into this microphone.” He was given rope and he hung himself. Many of us will pay the price.

Leslie Chang, the author of Factory Girls

, which is one of the best books about contemporary China and certainly the finest piece about life in the factories there,wrote a great article for the New Yorker: Do Chinese Factory Workers Dream of Ipads?

, which is one of the best books about contemporary China and certainly the finest piece about life in the factories there,wrote a great article for the New Yorker: Do Chinese Factory Workers Dream of Ipads?She gets right to he heart at the narcissim that is at the center of this whole issue- Daisey’s self-involvement, yes, but also all of ours. Her conclusion is a bit brutal, but right on:

“The simple narrative equating American demand and Chinese suffering is appealing, especially at a time when many Americans feel guilty about their impact on the world. It’s also inaccurate and disrespectful. We must be peculiarly self-obsessed to imagine we have the power to drive tens of millions of people on the other side of the world to migrate and suffer in terrible ways.”

She covers a lot of the same material in this interview with PRI’s The World.

March 12, 2012

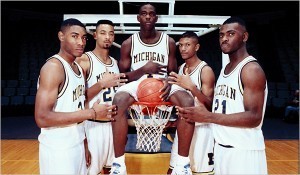

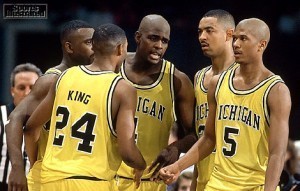

March Madness Special: A look back at The Fab Five

The Fab Five were in action just a few years after I graduated from U-M and I watched their exploits very closely.That made writing this story for Slam about a decade a go a special pleasure. It stands up well. Enjoy it as a March Madness moment.

Leaders of the New School

A look back at one of the most impactful team in college basketball history.

The Fab Five will forever be remembered by fans and critics alike, both for their on- and off-court antics. Meanwhile, this year’s edition of the Wolverines, led by the backcourt duo of Tim Hardaway Jr and Trey Burke, are co-Big Ten champs and have Michigan fans hype heading into March. Enjoy this look back at a classic piece, and expect plenty more to come as the NCAA Tournament approaches.— Slam Ed.

by Alan Paul

“The Fab Five was once in a lifetime! What they achieved will never, ever happen again.”

The familiar voice of Dick Vitale booms through the phone line, scratchy and emphatic. He may be a bit less frenzied off the air, but Vitale can’t contain his excitement when the subject turns to the Fab Five, the heralded freshmen who drove Michigan to consecutive title games in ’92 and ’93. “This story deserves special acclaim,” Vitale says. “I can’t tell you how many times I hear coaches say, ‘We can’t win because we have two freshmen in our rotation.’ It’s absolutely accepted wisdom and the Fab Five turned it on its head. I think what they did is absolutely unique in the history of basketball and doesn’t get the play it deserves.”

Vitale’s statement is accurate but stunning nonetheless. How could the Fab Five be underrated when, despite never winning a league or national championship, they still managed to change the face of college ball? The concept would have been unfathomable nine years ago when Chris Webber, Jalen Rose, Juwan Howard, Ray Jackson and Jimmy King were garnering countless headlines and being covered in a manner more MTV than ESPN.

“They were greeted like rock stars,” recalls Rob Pelinka, a role player on those teams and now an agent whose clients include Jazz rookie DeShawn Stevenson. “We sometimes needed police escorts because our bus would be surrounded by people.”

And just like every new sensation from Elvis to Eminem, there was debate about whether the Fab Five represented something creative and wonderful or arrogant and destructive. Their brash confidence, in-your-face trash talking and hip-hop fashion sense were both embraced and attacked like no college sports team before or since. The debate continues to this day, especially in Ann Arbor, where the basketball team struggles along under a cloud of impropriety that dates back to the Fabs’ recruitment. But one thing is beyond debate: The Fab Five represented something entirely new, an entire class of blue chip recruits covering every position, each of whom lived up to their top billing.

Power forward Webber was Michigan’s Mr. Basketball and the nation’s top recruit. Howard, a 6-9 center, and the 6-5 shooting guard King were the top players in Illinois and Texas, respectively, and Rose was a 6-8 pg who had led Detroit’s Southwestern High to two state titles. Jackson was the only one of the five who wasn’t a McDonald’s All-American, but the 6-6 Texan was one of the nation’s top small forward prospects. And while serendipity and coach Steve Fisher’s intense leg work certainly played huge roles in landing such an esteemed class, the Fab Five also recruited themselves.

Power forward Webber was Michigan’s Mr. Basketball and the nation’s top recruit. Howard, a 6-9 center, and the 6-5 shooting guard King were the top players in Illinois and Texas, respectively, and Rose was a 6-8 pg who had led Detroit’s Southwestern High to two state titles. Jackson was the only one of the five who wasn’t a McDonald’s All-American, but the 6-6 Texan was one of the nation’s top small forward prospects. And while serendipity and coach Steve Fisher’s intense leg work certainly played huge roles in landing such an esteemed class, the Fab Five also recruited themselves.

“Juwan is responsible for the whole thing,” says Webber today. “Jalen and I had talked about going to school together since we were 12, but Juwan is the one who got it going. He made us believe that we could create something great together.”

Explains Howard, “I started a chain reaction. Jimmy and I met on our visit and decided to go to Michigan. Then I called Chris, because we had become good friends through the All-Star games, and started working on him. I persuaded him and he got a hold of Jalen, which is exactly what I wanted. I was looking to win a national title or two, instead of just going somewhere and being assured of being the man.”

It didn’t take long for the dreams to come to fruition; all five recall that the chemistry was immediate. “The day we all met, we played a pickup game outside our dorm and it was just there,” says Webber.

Nonetheless, it takes a huge leap for a memorable pickup squad to become an NCAA title contender. Most great college teams result from a slow blending of talents, with experience trumping nearly everything else. The Fab Five turned that formula on its head. Juniors Pelinka, James Voskuil, Michael Talley and Eric Riley were key contributors, but clearly support players to the five freshmen, a seemingly impossible situation deftly managed by Fisher and his staff.

“It takes freshmen a while to grasp the college game,” says Randy Ayers, a current Sixers assistant who was the head man at Ohio State at the time. “A high school star has an adjustment period learning to accept sacrificing for the good of the team. That almost always takes a year or two, but the Fab Five found their niches immediately. Chris, Jalen and Juwan were the go-to guys and the Texas kids were the defenders. And they played off each other beautifully.”

Adds Vitale, “These guys truly enjoyed each other’s company and responded as a unit, with the emphasis on the team rather than individual stats. They were a very unselfish team that blended extremely well.”

And, the players all say, they made each other better on a daily basis, filling one another with their trademark confidence. “As a group, we always felt invincible,” says Webber. “Individually, you always have fear and doubt, but we never did as a team. I felt that together we could accomplish anything.”

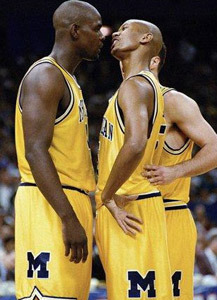

While the Fab Five’s critics accused them of showboating—“too much with the French pastry and the hot-dogging!” proclaimed broadcaster Al McGuire—the fact is, they played solid, team-oriented ball. If you watch their games today—easy to do, thanks to ESPN Classic—you’ll see a confident unit playing great help D, running crisp sets and effortlessly improvising whenever necessary.

“We had pretty good game-time execution, which is often overlooked because of some of the players’ flamboyance,” says Jay Smith, then a Michigan assistant, now the coach of Central Michigan University. Indeed, from their very first tip-off, Webber, Rose and King in particular exhibited tremendous flavor to go with their savvy. Webber was a dominant post presence with supple hands and ferocious power. Rose was a cocksure point with maddening lapses but an uncanny knack for coming through in the clutch. And King was a tremendous finisher as well as a deadly three-point shooter and reliable defensive stopper. Howard, meanwhile, was rock solid in the post, making teams pay for collapsing on Webber, and Jackson was a steady hand who often came through with crucial baskets, boards and stops. All five turned in highlight-reel-worthy jams on a regular basis.

“There were times when we just played basketball, and it may not have been all that structured, but we often ran the passing game, which is really just fundamental ball: reading each other, setting picks and cutting,” says King, who, like Jackson, is now playing in the IBL. “We were able to do it well because of our knowledge and understanding of the game, and because we practiced it a lot.”

But much of the initial buzz about the Fab Five had little to do with fundamentals—or basketball at all. Gallons of ink were spilled about their flapping shorts, black socks and gleaming bald domes and their constant on-court chatter, as they endlessly jawed at both opponents and each other. If it seems hard to understand why such things would cause a furor, that itself is evidence of the Fab Five’s impact. Watch their games and you’ll see that while the Fab Five’s opponents look dated in their clingy unis, the Michigan youngsters—even now—look contemporary. “They completely changed the fashion of college ball,” says Ayers.

And while some critics blasted Fisher for allowing such freedom, the coach wisely used it as a motivational tool.

“Fish would let us do things like get bigger shorts and wear black socks if we practiced hard,” Webber recalls. “He was like, ‘You can wear what you want as long as you work hard, practice right and play smart.’”

The group first came to serious national acclaim in the fifth game of their rookie year, when they took defending champ Duke to overtime before falling 85-81. Most observers considered it a great moral victory, but the Michigan players were incensed they lost a game they could have won. But while the sight of Webber and Rose yapping in the faces of Christian Laettner and Bobby Hurley delighted those who found the Dookies arrogant and insufferable, it also ruffled a lot of feathers. Columnists spewed and older Michigan alums stewed. Even refs weren’t beyond getting in on the act, as when Rose got T’d up for smiling.

to overtime before falling 85-81. Most observers considered it a great moral victory, but the Michigan players were incensed they lost a game they could have won. But while the sight of Webber and Rose yapping in the faces of Christian Laettner and Bobby Hurley delighted those who found the Dookies arrogant and insufferable, it also ruffled a lot of feathers. Columnists spewed and older Michigan alums stewed. Even refs weren’t beyond getting in on the act, as when Rose got T’d up for smiling.

The Fab Five seemed unbothered by any of it, however, finishing their freshman season 21-8 and ranked 14th in the nation, with a sixth seed in the Big Dance. In a fitting omen, the team ran into Muhammad Ali, the man who invented trash talking, at their Atlanta hotel the night before their first tournament game, against Temple. When The Greatest pulled Howard close and whispered “Shock the world!” in his young ear, The Fab Five had themselves a new rallying cry, which they rode to an Elite Eight battle with Big Ten champion Ohio State. The Jim Jackson-led Buckeyes had beaten Michigan twice already, but things had changed.

“They were a totally different team,” recalls Ayers. “They were physically stronger and they played smarter and with more confidence.”

Different enough to win a thrilling OT game, 75-71, catapulting them to the Final Four, where Nick Van Exel’s Cincinnati squad lay in waiting. After winning a nail-biter, the Fab Five had another date with Duke. Though they seemed unflappable, they came out for introductions lacking their usual fire, with nary a chest bump or holler. But if the rookies were a tad nervous, the reigning kings looked downright spooked. Perennial tourney hero Laettner sleepwalked through the first half, and the Fab Five clawed their way to a one-point lead.

It didn’t last. At the six-minute mark of the second half, the roof caved in and Michigan suddenly couldn’t score or defend. They ended up losing by 20, sending Webber running off the court, his uniform pulled over his sobbing eyes. In the locker room, he and his teammates all pledged to never again feel such crushing disappointment. They were at least sure of one thing: there was always next year.

But the sophomore season wasn’t the same for any of the Fab Five. “The novelty wore off and people no longer seemed to like the confidence and swagger they carried,” says Smith. “It got to the point where you either loved them or hated them.”

And, indeed, many younger fans gave serious love. Though they were widely criticized in the press, baggy shorts, black socks and M logos became as ubiquitous as Nikes on playgrounds and in gyms from coast to coast. And the impact was felt throughout college ball. Opposing coaches began letting their players alter their uniforms, and the Fab Five’s fashion sense already seemed less radical. By the time they faced North Carolina in the ’93 title game, the Tar Heels shorts were even longer than theirs. But that was little consolation to a group of 19-year-olds who felt themselves being tarred and feathered as everything-that’s-wrong-with-sports-and-kids-today.

“It’s a good story to build someone up and it’s a good story to tear them back down,” says King. “I understand that now, but at the time we couldn’t understand how we went from being media darlings to the nation’s bad boys. We didn’t really do anything to warrant that.”

In truth, as sophomores, the Fab Five were sometimes a bit out of control. After a big win at Michigan State, several players pretended they were defecating on the Spartans’ center-court S. And the team talked incessant trash before an early season rematch with Duke, with Webber saying he “wished Laettner would come back from [the NBA] so we can beat him too.” The Cameron Crazies had a field day heckling the team, as Duke pasted them by 11.

pretended they were defecating on the Spartans’ center-court S. And the team talked incessant trash before an early season rematch with Duke, with Webber saying he “wished Laettner would come back from [the NBA] so we can beat him too.” The Cameron Crazies had a field day heckling the team, as Duke pasted them by 11.

Still, the Fab Five righted themselves to go 25-4 and earn a No. 1 seed in the West regional. Now the attacks could really begin. Before the start of the tourney, Bill Walton called the Fab Five “one of the most overrated and underachieving teams of all time…who epitomize a lot of what’s wrong with a lot of basketball players.” It was the most vicious and well-publicized—but certainly not the only—assault on the team.

“We were just playing ball and having fun, and people said, ‘Just play, be quiet and don’t enjoy your wins,” says King. “But we weren’t putting on a show. We were just having fun doing what we love. We weren’t kicking people when they were on the ground like Christian Laettner did. But no matter what happened, teams like Indiana, UNC and Duke got only good press, because their coaches were perceived as being strong and in control, and we got attacked for taking over college basketball because we were perceived as being out of control.”

In the second round, the overrated underachievers pulled off the greatest comeback in Michigan history, coming back from 19 down to beat UCLA in overtime 86-84 on a King putback at the buzzer. After beating George Washington, the only thing standing in the way of a second straight Final Four was Temple, led by Eddie Jones, Aaron McKie and a bunch of less-talented tough guys. Chaney’s big men did everything but gouge out Webber’s and Howard’s eyes. On the verge of defeat, Chaney was finally T’d up for spewing profanities at both Fisher and the refs, had to be restrained by his assistant coaches and finally refused to shake Fisher’s hand—then went to a press conference and blasted the Fab Five for taunting.

“That kind of criticism was really bothersome all year long,” says King. “We just ignored it. In fact, we never even talked about how much less fun the second year was until Chris said it in a Final Four press conference. I remember thinking, ‘So it’s not just me.’”

In the semifinals, Michigan was a seven-point underdog to Jamal Mashburn’s powerful Kentucky team, which had dismantled its previous tourney opponents by an average of 31 points, thanks to Rick Pitino’s brutal end-to-end pressure. The Fab Five took the Cats into OT, their fourth extra period in eight games, before winning 81-78. It was not only their best-played game in months, but also one of the most memorable Tournament battles in recent years.

Despite all the criticism, pressure and close calls, they’d made it back to their second title game, where they would face UNC. In the first half, the Fab Five were again flat and out of sync, down six at the break. Then Fisher aggressively challenged them in the locker room and Webber lifted the team en route to 23 points, 11 rebounds and three blocks. The team got in trouble when Rose and King lost their shooting touches down the stretch, but Webber seemed fated to be the hero when he grabbed a missed UNC free throw with 20 seconds left and looked upcourt. After getting away with an uncalled traveling violation, he was headed for the history books—for all the wrong reasons.

Carolina led by two. With Rose covered, CWebb headed to the other end of the court, picked up his dribble and panicked. With Pelinka wide open and desperately waving his arms behind the three-point line across court and King staking out position underneath the basket, Webber called timeout. Michigan had none left. A T was whistled, UNC hit the shots and went on to win 77-71.

To a man, the Michigan players will tell you they never considered the possibility of losing that game. So they had to skip doubt and leap directly to heartbreak. Again. Before long, Webber would announce he was leaving school for the NBA, and that was that for the Fab Five. They finished their two-year run at 56-14, including losses in the two games that mattered most.

Might Walton have been right? Were they just a bunch of overhyped losers? If you ever ask Vitale that question, be ready to duck.

“It is absolutely absurd for people to criticize the Fab Five as underachievers or failures because they didn’t win a title,” Vitale says. “College ball is not the NBA. It’s one game and there’s a lot of luck involved. Many great teams don’t win titles, but we unfortunately live in a world where if you don’t cut down the nets, you didn’t achieve anything. That’s a ridiculous perspective.”

And no team ever proved that point more than the Fab Five.

*

Hey, you read this far. Now don’t forget to take a look at my book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues, and Becoming a Star in Beijing.

March 10, 2012

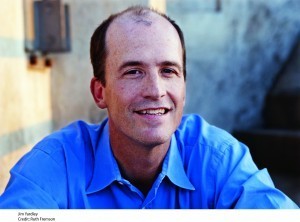

Q+A: Jim Yardley

My friend the author on Yao, Lin and t...

Q+A: Jim Yardley

My friend the author on Yao, Lin and the Chinese basketball system. Originally posted Friday, March 9 on Slam Online.

Jim Yardley was my friend and neighbor throughout the three and a half years I lived in Beijing. We ate, drank and hung out together often, usually sharing our tales of adventure. As the New York Times Bureau Chief, Jim knew the country inside and out, as evidenced by the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting he shared for an in-depth series on the Chinese legal system.

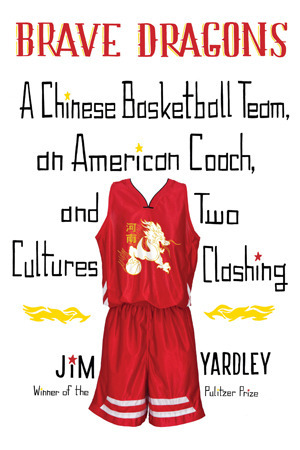

There were only a couple of small slices of Chinese life I felt I understood better than Jim—and one of them was basketball. I was, after all, SLAM’s man in China and had gotten pretty deeply into Chinese basketball. So I was surprised when he told me that he would be writing a book—about basketball in China. I was not, however, the least bit surprised to realize that my friend had penned a masterly work when I read the final product, Brave Dragons: A Chinese Basketball Team, an American Coach, and Two Cultures Clashing.

Jim Yardley does not do half-way and he immersed himself in the Chinese Basketball Association, in the process capturing much of what makes China so wonderfully contradictory—vibrant but stilted, incredibly modern but remarkably moribund.

Jim immersed himself in the subject, spending a year with the Taiyuan Brave Dragons after the team—the laughing stock of the CBA—hired ex-Hawks and Sonics coach Bob Weiss, the first former NBA head coach to take over a Chinese squad. Careful SLAM readers will recognize the Brave Dragons as the dysfunctional team God Shammgod played for when I profiled him in 2006.

Brave Dragons is a must-read for any hoops fan with a hankering to understand what is and isn’t happening in China.

SLAM: I was struck by the way you very clearly and rightly wrote about how Chinese players and fans have this ingrained sense of athletic inferiority—that they can’t be as good as Americans. Does that help explain the real power of Yao Ming?

JY: Yao Ming’s success in the NBA was huge in bolstering national pride, not only because he was so big—thus defying the clichés about Chinese being small—but because he became an All Star. Chinese love winners, and Yao was a big winner. But probably more interesting is what is happening right now with Jeremy Lin.

Lin has roots in China but his family is from Taiwan. He is 6-3—tall but hardly a giant—and is disproving all the preconceptions held by many Chinese, including coaches, about their own physical inferiority. I’ll never forget listening to a coach tell me that Chinese players were the equivalent of substandard raw materials, as far as producing basketball players. The best way to improve them, these coaches argued, was through relentless and repetitious drilling.

Lin is proving that someone with an Asian heritage can physically compete, even dominate, against the very best athletes in the world. Of course, Lin is American, and, without sounding jingoistic, I don’t think that should be discounte

d; he grew up in an environment where he was better able to develop his individual skills. His parents also sound like they were incredibly supportive. And, most of all, Lin sounds like a very determined guy, and, in the end, talent rarely rises without determination, too.

SLAM: I don’t think that people who haven’t spent time there could really understand how deep that feeling is. I believe that Lin could be a transformational player since he is essentially normal sized (compared to Yao).

JY: You are absolutely right. The whole Chinese basketball system is consumed by the search for another Yao, or at least for other big players. Lin forces that equation to be changed. There are plenty of 6-3 players in China. But why aren’t they developing the way Lin did by growing up playing in the United States? I think that question will resonate and, I hope, will help change the typical Chinese training methods.

To some degree, it is already happening. Some of the best young players are being identified and sent to the USA, Australia and Europe for coaching and conditioning.

SLAM: One of the oddest things about watching Chinese basketball is how lazy the players seem to be. Once you start to understand it, it becomes obvious that that’s only because it’s a defense mechanism because they have to work so hard—six days a week, 50 weeks a year. The insanity of this is obvious to every foreign observer. Do you think it is becoming more apparent to people within the system?

JY: You’ve made a crucial observation about the vicious cycle of how Chinese players are trained. They practice roughly 11 months a year, living as a team in a dormitory, often drilling and running two or three times a day. Players get worn down, also because most teams follow outdated weight lifting regimens and offer mediocre support from medical trainers.

So, yes, many players learn to loaf out of pure survival. They want to extend their careers, which means a certain amount of self-preservation is required. I do think many coaches are aware of this, but their response, usually, is just to push players harder in practice. Many Chinese coaches believe that players have to drill constantly, and practice daily, over months, to improve. It is pretty self-defeating actually.

The good news, though, is that many teams are starting to change, and these are the teams that are winning. The dominant team in the Chinese league—the Guangdong Southern Tigers—also happens to be the most enlightened, as far as training techniques.

Amazon.com Widgets

SLAM: Right, but I’ve been surprised by how little impact that had for years. Do you think it’s finally starting to initiate more changes throughout the League?

JY: I think change is starting to happen, especially since I left. Bob Weiss was actually a breakthrough figure. Foreign coaches had been in China for years, but Weiss was the first big name. And his success in turning around the Brave Dragons influenced other teams. More and more teams have started hiring foreign coaches with experience in the NBA. Also, the league is gradually transitioning in its ownership structure. Fewer and fewer teams are now owned by local governments, or by government sports bureaus. More teams have private owners, and some of them are trying to emulate the Guangdong model. Not all, of course. The owner of the Brave Dragons is a private entrepreneur but his treatment of the team is decidedly old school.

SLAM: There is a younger generation of Chinese players, exemplified in your book by “Kobe” and Joy playing with more passion and more out of love. Is this an actual trend?

JY: That, to me, is one of the wonderful things about the league. The young guys love the game, and are desperate to win, and to play the game in a more free wheeling style. You can see their passion for the game.

In December, I met an 18-year-old kid playing for the Guangsha team in the Chinese league. He also played on the Chinese national junior team. His name is Wang Zirui. I think he has the potential to be a very, very good point guard. I hope so.

SLAM: As you detailed recently in the NYT Magazine, the NBA’s China plans are struggling. How ecstatic are they about Lin?

JY: The NBA remains very popular in China, but they have seen their ambitions curbed in recent years. They wanted to create their own NBA league in China, if in partnership with the CBA. But the Chinese league turned them down. They talked about creating a network of arenas. But that also hasn’t happened. Television ratings had sunk since Yao’s best years—say, 2005 and 2006. Again, the League was still popular, but the NBA was facing challenges in finding new revenue streams. Now along comes Jeremy Lin.

Fans in mainland China and Taiwan are going nuts. Knicks jerseys, real and counterfeit, are flying off the shelves. I assume television ratings are shooting up. Given that Yao retired last year, Lin would seem to arrive with absolutely perfect timing for the NBA. He doesn’t solve some of their deeper issues, about finding new ways to make money, or about developing a league. But I assume they are absolutely thrilled.

SLAM: Did David Stern sacrifice 18 virgins to make this happen?

JY: I heard it was 24 oxen.

SLAM: There was a great line in your book about the failure of the CBA to change, from someone who had been hired to analyze the league: “You can’t really understand something if your job depends on you not understanding it.” Does that still apply?

JY: It’s important to remember that the CBA is a government bureaucracy as much as a sports league. It is run by guys who either played or coached in the league, or by other bureaucrats, so they are invested in the status quo. However, they are facing real pressure to improve the quality of play, since fans need only watch the NBA on television to see a better basketball product. The CBA is trying to do this in superficial ways, by bringing in cheerleaders and game time music and stuff like that. They also seem more interested in developing better talent.

But many people question whether the league can ever achieve its potential if it remains controlled by the government. The ultimate responsibility of the CBA is not to put on the best possible basketball league for fans; it is to develop a national team to compete for China in international competitions. Several years ago, the CBA hired a consulting firm for advice on how to improve. The consulting firm drew up a plan in which the league would be largely separated from the government sports administration. There would be transparency in accounting, and other things. Needless to say, the CBA didn’t go for it.

SLAM: Is there an inherent conflict between one organization running the league and the national team?

JY: Yeah, lots of people think the CBA has got to attain greater independence from the government. It can’t develop properly otherwise. If the goal is to make the CBA a true commercial basketball league, then you can’t have government officials running it. Officials make policy that may or may not be conducive with winning CBA games. Private owners, dominated by a commercial impulse, just want to do whatever they can to win games.

SLAM: How excited were you when you found out that Bonzi Wells was coming to the team you were following?

JY: I had mixed feelings. Bonzi’s arrival meant another former NBA player, Donta Smith, would be cut; I really liked Donta and the team was doing really well with him. However, I realized that Bonzi was a hell of a story, and he was. He is a very complicated guy, and I hope I captured some of that in Brave Dragons. One thing I found interesting was the relationship between Bonzi and Boss Wang; they clashed, big-time, yet Boss Wang really respected Bonzi.

SLAM: Boss Wang is a seriously crazy dude and the Brave Dragons have long been notorious for being mercurial and terrible. The year I was following God Shammgod off and on for SLAM, they went through four or five coaches—and had a translator who couldn’t really speak English. Did you choose them to follow because of their nuttiness and the assumption that whatever happened would be interesting and fun to write about?

JY: Someone told me that Boss Wang was like a Chinese Steinbrenner, or maybe a Mark Cuban in his early days. To be honest, I knew almost nothing about Boss Wang when I hooked up with the team. I had heard that Weiss was coming to China and I contacted him to see if I could spend time with him. At that point, I hadn’t decided whether to follow one team, or to jump around the league, tackling different themes and subjects through different players and teams. But once I got to Taiyuan, and settled in with the Brave Dragons, I realized that I had a hell of a story with just this team. It was oftentimes hilarious, oftentimes heartbreaking but always interesting.

SLAM: Foreign players in China are in a tough position: They feel they need to score 40 ppg to earn their contract—and sometimes the teams directly make them feel that way. But doing so does not help Chinese players develop. Do they feel that tension?

JY: As a foreigner, where your livelihood is at stake, you do have to be something of a basketball mercenary in China. The system is weird: Teams are usually allowed only two foreigners, and those foreigners are the highest paid guys on the team. They also are limited in their playing time. So when they are in the game, they’ve got to justify their contracts, which means shooting and shooting often.

Some guys just flat out gun at will. Others, though, manage to fit into the team and score their points. But, absolutely, tensions do arise between foreign and Chinese players after a long season. Usually, it boils down to respect; if one side doesn’t offer it to the other, problems can arise. Amazon.com Widgets