Alan Paul's Blog, page 42

August 20, 2013

Why I Write

I did in an interview for the Why I Write website, and I think it came out pretty well.

It’s really hard to read something like about yourself and not feel a little pompous, but it captures my method of writing, or lack thereof.

#goodreads-widget {

font-family: georgia, serif;

padding: 18px 0;

width:565px;

}

#goodreads-widget h1 {

font-weight:normal;

font-size: 16px;

border-bottom: 1px solid #BBB596;

margin-bottom: 0;

}

#goodreads-widget a {

text-decoration: none;

color:#660;

}

iframe{

background-color: #fff;

}

#goodreads-widget a:hover { text-decoration: underline; }

#goodreads-widget a:active {

color:#660;

}

#gr_footer {

width: 100%;

border-top: 1px solid #BBB596;

text-align: right;

}

#goodreads-widget .gr_branding{

color: #382110;

font-size: 11px;

text-decoration: none;

font-family: verdana, arial, helvetica, sans-serif;

}

Goodreads reviews for Big in China

Reviews from Goodreads.com

August 15, 2013

Playing Duane Allman’s guitar

A special guest post:

What was it like to play Duane Allman’s guitar?

by Sonny Moorman

had the thrill of my musical life last year when I got to play Duane Allman’s 1957 Goldtop Les Paul on a Macon, Georgia, stage.

I grew up listening to Lonnie Mack playing in bars around my Ohio hometown and have been greatly influenced by Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Winter, Roy Buchannan, Rory Gallagher, Peter Green, Carlos Santana and a host of others.

But it was the Allman Brothers Band’s Duane Allman and Dickey Betts who hit me the hardest. Their mix of rock, blues, jazz, soul and country improvised by virtuoso players just floored me — and it still does!

Willie Perkins, the ABB’s tour manager during their golden era, 1970 to 1976, has been my manager for the past 15 years. So the Brothers and their music have played a huge role in my life and career, which made playing Duane’s Goldtop a thrill and pleasure almost beyond words.

The 1957 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop, serial No. 7 3312, is relatively light for a Les Paul, with a big, rounded neck profile. It was refinished by Tom Murphy in 1997 at Gibson’s Historic Division and set up much as Duane might have played it, including the stringing “over” rather than through the stop bar (something I do on my guitars as well). This gives the guitar a nice, supple feel while sacrificing little if any of the famous Les Paul sustain.

I own and play a 1996 Gibson Historic Collection Les Paul Goldtop R7, which I’m elated to say is very similar to Duane’s guitar in appearance and feel. Duane’s is a bit lighter, perhaps because the pickguard, pickup switch ring and pointers have been removed, but the guitars looks and feel virtually identical. Here’s a pic by E.J. Devokaitis , the curator of the Big House Museum of me with both guitar

This Goldtop is Duane’s voice on the first two ABB albums (The Allman Brothers Band andIdlewild South), as well as on Derek and the Dominos’ Layla sessions.

Even un-amplified, the guitar truly speaks in a lively resonant voice, as I learned sitting outside the back door of the Cox Capital Theater in the quiet of the Georgia night with Willie Perkins by my side: Any Duane fan would have recognized that guitar in the dark! It had the same tonal character in that Macon alleyway that it has on all of those famous recordings. After listening to that guitar thousands of times, I could barely believe it was in my hands and I was going to play it on stage.

I played my Gibson Flying V through my reissue Marshall model 1962 Bluesbreaker as we played songs from our Atlas Records CDsLive as Hell and More Live as Hell for about an hour (for that part of the show). Drummer Dave Fair, bassist Chris Perreault and I were loving the crowd and having a fine night. And then it really got special, as Willie came onstage bearing Duane’s guitar. He said, “This is my friend Duane Allman’s guitar, and I carried it all over the country, but my friend Sonny Moorman’s gonna play it tonight.”

I then invited Berry Duane Oakley, son of original ABB bassist Berry Oakley, to play with us. He came out carrying his dad’s “Tractor” bass, plugged in to Chris’s Ampeg SVT, and we started into the ABB classic “Dreams.” After that, we rolled right into “One Way Out.” Videos of both are at the bottom of this post.

I had been worried I would be too nervous to play this iconic instrument — that I would freeze up and choke at the prospect — but its current owner, Scot LaMar, had admonished me to “Play it like I stole it,” so I dedicated myself to giving it my all. From the moment I first picked it up, it could not possibly have seemed more natural for me to play that guitar. I felt absolutely and totally at home!

It was a special pleasure to play it alongside Berry Duane Oakley, who is truly his father’s son! I’ve never heard ANYONE other than his dad play those songs with the kind of feel, fire and emotion that he delivered, and the combination of Dave and Berry’s stellar playing and the magic of Duane’s guitar truly made a dream come true for me.

What was it like to play Duane Allman’s guitar? Man, we were hittin’ the note!

We played “Dreams”:

and we rolled right into “One Way Out”:

My very special thanks to Scot LaMar, E.J.Devokaitis, the Big House Museum, Dave Pierson, GABBA, and of course, Willie Perkins, for making this happen.

June 27, 2013

How David Bowie saved Peter Frampton’s career…

I interviewed Peter Frampton for the WSJ Speakeasy blog. I enjoyed doing it… He’s a smart, interesting guy and a real gentleman. I never knew about the Bowie connection.

April 23, 2013

From the archives: Earl Monroe

In honor of his new autobiography Earl The Pearl: My Story, I present the story below about Earl Monroe.

This was a really fun one for me to dig out and read. I forgot how unusual it was and how many people I spoke to, including a passel of Basketball Hall of Famers, amongst them Earl’s college coach, Clarence “Big House” Gaines. man, I used to be really ambitious with these stories.

Earl is speaking right here in Maplewood, at Words bookstore, this Saturday at 5 pm. I will be there.

**

Slam has been on the trail of Earl “The Pearl” Monroe for years, so I couldn’t believe my luck when the man himself answered the phone at his New Jersey contracting and promotions business. True to the word of everyone who’s ever known him, Monroe was thoughtful, polite and articulate. He even seemed glad to hear from me, so his assertion that he didn’t want to talk about his glittering career because he was “ancient history” came as a shock.

I assured him that he was wrong, and said that Hall of Famers line up to sing his praises. Indeed, Clyde Frazier says Pearl’s the only opponent he ever dreamed about stopping. Willis Reed calls him the only player he would stay home to watch on TV. Tiny Archibald says it was an honor just to be on the same court. Hard-driving CEO’s Dave DeBusschere and Dave Bing sound like awe-filled children as they recall Earl’s exploits. Still, Monroe doesn’t want to talk, thanking me for the attention and offering his blessing if we want to write a story without him. Recent health problems, he explains, leave him longing to look forward and not back.

It’s hard to believe there is no room in Earl Monroe’s brain for basketball – like hearing Shakespeare say words no longer interest him. After all, the guy had so much shine that his street name was Jesus. What follows then are the words of his Apostles. Hopefully, it’s enough to make you – and him – understand why the people who knew his game the best were convinced that Earl Monroe was the Savior.

**

Earl Monroe was a legend long before he ever set foot on an NBA floor, a playground deity in his hometown of Philadelphia, a black college messiah after leading Winston Salem State to a championship by averaging a remarkable 41.5 ppg in ‘67. And the points tell only a sliver of the story.

“You could be embarrassed by Earl in a split second,” recalls Bing. “You had to be completely prepared and involved and even then you could only react because you never what he was doing next. He could get anyone out of position with his body contortions and fakes and he knew what to do once he had you there.”

His endless improvisations and bottomless bag of tricks led Monroe to be tagged with countless nicknames. He was Magic before Magic and Doctor before the Doc, to name a few.

“Some of Earl’s street names were Jesus, the Savior, Slick, Einstein, Thomas Edison, the Doctor and Black Magic,” recalls Philadelphia hoops impresario Sonny Hill. “Those names were an attempt by people to describe the unbelievable things they were seeing on the court. Earl’s game was hard to explain because it was the embodiment of the creativity of black culture.”

Monroe was a late bloomer, favoring soccer and baseball as a kid. He didn’t hit the hardwood until he was 14 and didn’t make the varsity team at John Bartram High until midway through his junior year. After graduating, he enrolled at Temple Prep to improve his chances of getting a scholarship offer, but dropped out after a semester and worked as a shipping clerk.

All the while, Monroe’s playground legend was growing. Though he played center in high school, on the blacktop the 6-3 Monroe was already a whirling dervish of improvisational moves. His growing street rep filtered all the way down to North Carolina, where Winston-Salem coach Clarence “Big House” Gaines offered Monroe a spot on his team sight unseen.

“It wasn’t unusual to sign a player without seeing him and I had no doubts about Earl because my boys in Philly told me could play,” recalls Gaines, a Hall of Famer with the third-most collegiate wins ever. “In those days, you couldn’t get a bad player out of Philadelphia.”

Winston-Salem played in the CIAA league of black colleges, which was filled with top shelf talent as D1 schools were only beginning to fully integrate. The league featured an uptempo game which was rare elsewhere and which allowed Monroe to be himself. He averaged just 7.1 ppg as a freshman, but 23.2 ppg as a sophomore and 29.8 ppg the following year before blowing up as a senior for 41.5.

Meanwhile, he continued to return to Philadelphia each summer, growing his legend in the city’s competitive Baker League. Tiny Archibald, another playground hero who became an NBA Hall of Famer, recalls people literally bowing down when Monroe walked onto the court for games pitting the Baker League All Stars against New York’s Rucker League All Stars.

“Earl was an attacker who made things happen,” says Archibald. “Inner city playgrounds are filled with guys who are flashy for no purpose. But every move Earl made, no matter how incredible, was intended to score a basket, not to show off. He did them to freeze defenders or send them the wrong way. When you watched him you were entertained, but his purpose was to win.”

The winning began in earnest during Monroe’s senior year, as Winston-Salem State went 31-1 and won the College Division (now D2), becoming the first black school to win any NCAA basketball title. It was this season that began to transform Monroe from an underground legend to an aboveground sensation. Put another way, it’s when some white people started to hear of him. It was also when he was tagged “the Pearl” after a writer referred to Monroe’s abundant points as “Earl’s Pearls.”

Despite all his success, Monroe was considered an uncertain pro prospect. Baltimore and Detroit flipped a coin for the right to pick first and grab Providence’s Jimmy Walker. Detroit won the battle, but lost the war, though the Bullets hesitated long and hard before selecting Monroe at the urging of a young scout by the name of Jerry Krause.

“There were questions about Earl’s ability to perform against top-notch competition,” recalls longtime Knicks announcer Marv Albert. “Once he got here, however, you could see immediately that he was the real deal. He was phenomenal.”

Two months into the season, Monroe was in full control of the Bullets, and was named ROY after averaging 24.3 ppg, tied with Wilt for third in the league. But, again, the points only tell a fraction of the story. Every guard in the league dreaded facing Pearl because his improvisational moves made it impossible to play anticipation D. Bing laughs when told that Frazier dreamed about defending Monroe.

“In our dreams is the only place any of us could stop Earl,” notes the guard who was himself ROY in ‘67. “He wasn’t exceedingly fast and he couldn’t jump all that high, but he had an uncanny ability to get free and he didn’t need much room to get his shot off.”

Monroe’s assortment of moves and brilliant, endless knowledge of the game became ever more important as his knees, already bad as a rookie, grew worse over the years.

“Earl had a great work ethic and he understood the game incredibly well,” says Frazier. “He always had an extra dribble because he never committed until after you did and then he was gone. And his footwork was exquisite; he always kept his feet staggered, so he could go left or right with equal ease, which is what made his spin move so effective. I never fully understood all these little tricks until Earl became my teammate and it helped my own game quite a bit.”

Despite commanding such reverence from his peers, Monroe was, as Frazier notes, “extremely misunderstood.” He was viewed as a flashy individualist despite teaming with Wes Unseld to transform the Bullets from doormats to serious contenders. After losing to the champion Knicks in a great 7-game Eastern Finals in ‘70 they made the Finals the next season, losing to the Bucks of Kareem Abdul Jabbar and Oscar Robertson. Monroe also remained a fixture in the Baker and other summer leagues, giving him a profound connection to the black community, even while some pundits wrote him off as a sideshow attraction. When he was traded to the Knicks midway through the 71-72 season, critics clucked that Pearl would never meld with Clyde or fit into Red Holzman’s team-oriented system.

“There was some apprehension about Earl amongst the Knicks because no one really knew him,” recalls Albert. “As an opponent, he wasn’t around much, so some thought he was arrogant. But it turned out he was just very shy, and was like the greatest guy in the world. He fit in right away and became extremely popular with his teammates.”

Still, Monroe retained a mysterious aura. Albert recalls that he would often seem to appear out of thin air, though Frazier has a simple explanation for this occurrence: “He was just always late. Punctuality was not his thing. When Earl arrived, the plane departed.”

While his game was still intact, Pearl quietly took a backseat on the Knicks. After averaging 24 ppg in his four full seasons with the Bullets, Monroe initially served as sixth man in New York before teaming with Frazier in one of the greatest backcourts in league history.

“It was really exciting,” Frazier says. “People questioned our ability to share the ball, but we never let our egos get involved and we didn’t worry about who was the ‘1’ or ‘2.’ We were both guards. We had to handle, we had to score, and we had to rebound and play d. It was a joy to play with him and it was ironic because he was so flashy on the court and so quiet and introverted off it while I was just the opposite. My game was relatively generic, but I had the Broadway image.”

While still electrifying, Pearl gave up countless shots, averaging just 11.9 and 15.5 ppg in his first two season with the Knicks, a sacrifice which did not seem to bother him in the least. Having already accomplished so much individually, Monroe only wanted one thing when he arrived in New York: a ring. He got it in his second season there, clinching the ’73 title by scoring eight points in the last two minutes of the deciding game to drop the Lakers in five. Their second title in four years was a virtual last gasp for the Knicks. After one more elite season, Reed and DeBusschere were gone, Bill Bradley was barely hanging on — and Monroe again became a leading man.

Recalls Sonny Hill, “When the Knicks started falling apart, Red Holzman went to Earl and asked if he still had any tricks in his bag. He needed Earl to Be Earl again.”

Monroe upped his scoring back over 20 ppg from ‘75-’77, while also increasing his boards and assists. He had two more solid years in ‘78 and ‘79 before finally slowing down in his final year, ‘79-80, playing just 51 games and scoring just 7.4 ppg. It was a remarkable 13-year career for a guy who played with knees so bad that a ’68 Sports Illustrated profile questioned his ability to play more than a handful of NBA seasons.

“Earl enjoys anything that’s the opposite of what people think,” says Hill. “When they said he couldn’t fit into the team system, he took his ego and put it in the bag. Later, when people thought the Pearl had no more shine, he took it right back out. His very creative mind is always running, which is how he became such a unique talent. There’s not anyone you can compare him to, because there has never been anyone like Earl Monroe.”

April 21, 2013

From the archives: Rasheed Wallace

In honor of Rasheed Wallace’s second and presumably final retirement, I present this profile of him I wrote for Slam in 1999 or 2000. Lots of classic moments in here, including a convo with Sheed’s mother and a good interview with Dean Smith.

The Portland Tail Blazers just lost a tough game to the Knicks and the postgame sea of reporters is buzzing in the hallway outside Madison Square Garden’s visiting locker room. Talk focuses on Rasheed Wallace, who just celebrated his first-ever All Star selection by getting tossed from his fourth game in 10 days, then throwing both a towel and a wrist band onto the court before being escorted away by an anxious coach Mike Dunleavy.

The locker room doors open and the reporters bumrush Wallace, who sits at his locker, legs spread, head bowed between his knees, hands clasped behind his skull, fingers gently rubbing his hair. The reporters ready their tape recorders, uncap their pens and flip through their notebooks, preparing for what appears to be Wallace’s imminent interview session. Understand that a player needn’t be sitting at his stall; NBA locker rooms have more backrooms than a political convention. Being there postgame generally indicates a readiness to talk.

For long minutes Wallace sits silently, the only player in the room, as the reporters shuffle their feet, clear their throats, sneak glances at one another and look around the room praying that another Blazer will emerge. Where the hell is Scottie Pippen when you need him?

Finally, Wallace runs his hands vigorously through his ‘do and stands up, exhaling loudly. He looks around at the gathered masses, waves his hands in front of him, says, “Let me take a shower first” and shuffles out of the room, his flip flops flipping and flopping. The journalists let out a collective exhale and disperse in search of Pippen, Brian Grant or Steve Smith. Meanwhile, Bonzi Wells sits in front of his locker, rubbing cocoa butter into his arms. No one gives him a second glance, even though his 18 fourth-quarter points just single-handedly kept his team in the game. He asks what I’m working on.

“I’m waiting on Rasheed.”

“You gonna be waiting till your wheels fall off.”

“Why’s that?”

“Sheed’s cool; he’s my man. We hang all the time. But he’s kind of to himself.”

A few minutes later, Wallace is back, silently dressing at his stall, his back turned to the re-gathering reporters. I’m standing just to his right. “Uh, Rasheed,” I say, more quietly than is my norm. “Got a minute for Slam?”

He doesn’t so much as glance sideways at me. “Go ahead, man.”

So we talk as more and more reporters gather behind his back, patiently waiting their turn. I ask him about his foundation for kids, his record company, his All Star selection, and his days at North Carolina running with Jerry Stackhouse. He speaks in something of a monotone. His answers are short but thorough, and he actually doesn’t seem in any particular hurry for me to shut up.

All the while the press corps behind us is growing increasingly agitated at me for violating the postgame locker room etiquette of talking about tonight’s game first and foremost. Finally, one guy can’t stand it anymore. “Hey, Rasheed,” he says, “how about a question about tonight’s game?”

So I melt away and he turns around, mutters something to the effect of “tough loss” and walks out of the room.

So it is with Rasheed Wallace. You want to talk to him, move quickly when you have a chance and hope for the best. You want to appreciate his talents, just watch him play. You want to know more about him, talk to any of his teammates or coaches, who are quick to say that the Rasheed seen on court is nothing like the Sheed they know at practice, on the bench or at home hanging with his wife and three kids.

Wallace is unusually close with his mother, Jackie, who resigned her 23-year job with the state of Pennsylvania and moved to North Carolina when he enrolled because “I didn’t want my baby to be alone and we have no family down here.” She now runs his foundation with her two other sons.

“I’m damn proud of Rasheed as a ballplayer but I’m way more proud of him as a person,” Wallace says. “He is a great father and he was determined to give back to the community which is why he set up his foundation, which will be his legacy in Philly long after he’s gone. He’s very dedicated and if you know him, he can be silly as a rabbit. Put a Dreamcast or a paintball in his hand and you’ll see just how funny that boy can be. And I know that no one would think that from the way he acts on the court.

“Part of that is a result of how competitive he is –he hates losing – and partly, I actually think he thinks that if something is obviously wrong and he expresses his opinion, they will change the call. And there he is dead wrong. I’ve discussed this with him since high school, but this is one area where he doesn’t listen to his mother. He actually tries very hard to not react to a call, but it just gets to him. He gives 100 percent and he just gets a little twisted, a little bent out of shape, in the heat of battle.

“He wants to give the outward appearance that he’s a tough guy. Growing up and living in Philadelphia, when I walked out of the house, I would have a set face on that said, ‘Don’t mess with me.’ It was just a façade. That’s what he’s doing, and a lot of it comes from growing up in such an urban environment.”

Says Dean Smith, who coached Wallace at the University of North Carolina, “I was delighted to be his coach for two years and I’m sure everyone who’s had him would tell you the same thing: the guy’s a jewel. He puts the team first, practices hard and is a great influence. In fact, Portland’s Tates Locke called me about him when they had a chance to make the trade [with Washington, in 1996] and I said, ‘If you’re lucky enough to get him, you better jump on it.’”

“His demeanor on the court is that he’s a real hard-nosed guy, but off the court, he’s totally different,” says Jermaine O’Neal, along with Wells probably Wallace’s best friend on the team. “He’s very smart, a real family man, loves video games and listening to music. He’s a real down-to-earth guy. Everybody’s missing that about Rasheed. I think in order for him to play well, he has to be the way he is on the court. Once he gets to the locker room, all fun and games are over, but that’s not the guy his friends know.

“When I got here, it was a tough transition coming right out of high school in South Carolina to being a professional in a city so far from home, with a totally different culture. The very first night I got here Sheed took me out to dinner and we started talking and he helped me tremendously with all my adjustments. And we’ve been great friends ever since. He’s like a big brother to me.”

Adds Jerry Stackhouse, Wallace’s UNC running mate, “Sheed’s a great guy who’s a lot of fun to be around. Basically, everyone who knows him loves him. He’s excited all the time, he’s always upbeat and positive and he doesn’t let anything bother him. That rubs off on the people around him. You see him on the court and he’s so emotional that you would think he has a lot of turmoil pulling at him, but that’s just not the case. He’s just happy-go-lucky Sheed, and he really never has a bad day.

“I think the reason he’s the way he is on court is that he thrives on being the villain, especially when the fans are nagging him. He gets into it and it fuels his competitive fire. Then it’s not just you against the guy you’re guarding or the team; it’s you against the whole arena. A lot of guys in this league struggle to find motivation each night and that’s something that he uses to get himself going, whether it’s the fans or the officials. But while he may appear to be a volatile guy, he’s not. You just have to get to know him.”

Yet, how can anyone but Wallace’s closest friends ever know him if he refuses to speak to the press? From all appearances Wallace is a dedicated family man, who fought long and hard for custody of his son. He’s also a budding rap entrepreneur with his Urban Life Music record company, and an involved community uplifter through his Rasheed Wallace Foundation, which is run by mother and brother and sponsors kids activities and rec centers, primarily in Philadelphia and North Carolina. Rasheed personally runs two weeks of free basketball day camp in Philly every summer. But none of that explains why reporters have been dogging him since he was a 14-year-old North Philadelphia resident with a basketball court painted onto his bedroom floor and a poster of Patrick Ewing watching his every move. The reason so many try so hard to elicit so few words is simple: The guy can flat out play.

As a UNC sophomore in ’95, he shot a remarkable 65 percent from the floor in teaming with Stackhouse to lead UNC to the Final Four. Both then went pro, and were chosen back to back, Stack going third to the Sixers and Wallace going next to the then Washington Bullets, who incredibly gave up on him after one season and sent him to Portland for Rod Strickland. Over the course of his five-year pro career, he’s shot 52 percent and averaged 13.6 ppg , 5.9 rpg and just over one block. But the numbers only begin to tell Wallace’s story.

“What really makes him such a valuable asset is his versatility,’ says Dunleavy. “He can play three positions – the 3, 4 and 5 – at a very high level, both offensively and defensively and that gives me great flexibility.”

Indeed, for the last two years, Wallace, a natural power forward, logged most of his minutes at the 3 and in the Knicks game alone, he was matched up at various times with Latrell Sprewell, Patrick Ewing, Marcus Camby and Larry Johnson.

“Defensively, I don’t really worry about who I’m playing against,” says Wallace. “I just go out there and play team defense. But on offense I always know who’s on me. If it’s someone as small as Spree, I’m going to the block. If it’s Patrick, I’m going outside. You got to know that. That’s just basic basketball.”

But there’s nothing basic about Wallace’s ability to excel in so many different ways, which puts him in rare company.

“I think Sheed, Webber and Garnett are the best power forwards in the NBA,” says Blazer pg Damon Stoudamire. “They are the new breed of forward. Sheed’s 6-11 but can really move and shoot, so he can take you outside or inside.”

Knicks forward Kurt Thomas acknowledges that Wallace presents serious matchup problems and notes that while this season marked his first All Star selection, he has been widely respected by players for years. “Just look at the guy,” says Thomas. “He’s 6-11, he jumps out of the gym, he has a great touch, he runs the floor well and he plays defense. His height and length alone – he must have the wingspan of someone 7-5 – make him very tough to guard. He’s easily one of the top power forwards in the league and is a great asset to the team; anyone would love to have him and Portland is lucky that they do.”

Don’t think they don’t know it.

Says Dunleavy, “Rasheed always gives us a mismatch in our favor because he can guard anybody and score on anybody. The one way I know people can stop him is if he’s not in the game. We need to have Rasheed on the floor.”

Which brings up the problem; at the halfway point of the season, he led the league with 21 T’s in the team’s first 43 games. O’Neal says that Sheed is acutely aware of the game situations and would never jeopardize the team by picking up a T in a bad spot. “I’ve never seen him get one in crunch time of a close game,” he insists.

Yet Wallace himself says that he refuses to alter his game or style to avoid whistles, even after he’s been whistled for one technical. “I don’t let it alter my approach,” he says. “I’m still going to go bust my ass and do what I do.”

Many of Wallace’s teammates insist that he has become a marked man, receiving technicals for things that would be ignored if committed by other players. Smith says this happened in college, as well. “He had nine or 10 technicals in two years here which is probably a record under me,” Smith recalls. “It was strange because his demeanor was so different in practice, but he also got a lot of them for virtually nothing because he had the reputation, which can be tough to overcome.”

Still, while few will say so publicly, this is an area of concern for some of Wallace’s teammates. One not to afraid to admit it publicly is Pippen.

“We try to talk to him on the court, but it goes as far as he wants it to,” Pippen says. “He feels that he’s not getting the calls, but he can’t keep letting us down by getting eliminated from the game.”

Ironically, in all other respects, Wallace is a consummate team player. In fact, any complaints about his game have tended to focus on his lack of assertiveness and his willingness to go with the flow of the game rather than demand his touches.

“When Rasheed says he’s more interested in the team winning, he means it,” says Smith. “He actually takes the team-first mentality too far sometimes. Every once in a while, I used to call a timeout and remind everyone that we had a guy down low shooting 65 percent and we had to get him the ball. He was content not to have it, to take whatever shots came his way and focus on rebounding and playing defense. I think Mike’s trying to talk him into being more assertive offensively right now, in fact.”

Pippen says that with a little more aggressiveness and impassioned commitment, Wallace could make the final leap from greatness to superstardom.

“He has so much talent and he might never scratch the surface of it,” Pippen says. “If he would just put a little more effort into perfecting a few things it would change his whole game and make him a much better player. He’s a great player — he has so many tools –and he should use that to his advantage. If he worked at it, he could be one of the best players in the game. But I’m not sure if ‘Sheed wants that. He doesn’t even want to be an All-Star, but, hey, he is.”

Pippen is entitled to his opinion, but it seems likely that he is confusing Wallace’s contentment with playing a non-starring role to a lack of dedication. Like most of his teammates, he could be averaging much higher numbers in a different setting but is happy winning in Portland.

“This is a great situation,” says Wallace. “I don’t mind being a decoy or whatever. If the teams are concerned or worrying about me, that’s going to leave someone else out there. And you have to respect them all. You have to respect Damon’s and Steve’s j’s. you have to respect Pip’s slashing and Brian’s rebounding capabilities. It takes a whole lot of pressure off any one person.”

Wallace was named Portland’s lone All Star despite solid but not gaudy numbers – halfway through the season he was averaging 15.5 ppg and 7 rpg. He insists that he doesn’t care one way or the other and would have just as soon had a few days rest to prepare for the second half of the season.

“I don’t care about being selected,” Wallace says. “It’s all favoritism and politics. Actually, it surprised me that they selected me because of my rep. Anyhow, I’d rather have the respect of my peers than be named an All Star by the league.”

But Rasheed’s closest friends say that his non-chalance about his All Star selection is a false modesty.

“Sheed said he didn’t care about making All Star?” asks Stackhouse. “That’s baloney. It’s a great honor, and it’s everybody’s dream to be an All Star in this league.”

O’Neal too doesn’t quite believe Wallace’s claims of indifference, though he says that his friends’ team-first attitude makes him somewhat embarrassed to be singled out. “Plus,” adds O’Neal. “He’s a hard-nosed guy so he’s not going to admit that he’s happy he made it, but everyone wants to play in the All Star game. I can tell you this: every single person on this team was extremely happy for him; when we heard the news we were all jumping up and down and hugging.”

O’Neal is talking before a game with the Celtics at Boston’s Fleet Center, a few days after the Knicks debacle. The team is back on track, winning fairly easily, with Sheed going for 13 and 5, as well as three swats.

Afterwards, he sits at his locker scraping down the calluses and blisters on his feet with a mean-looking device that looks frighteningly similar to a bottle opener. Teammates Stacey Augmon and Gary Grant look on in disbelief.

“That is too nasty,” Grant says, as Augmon adds some hoots of derision.

Sheed quickly fires back, “I’m a runner and this is from running,” he says to his seldom-used teammates. “Y’all wouldn’t know about that.”

He goes off to shower and while he’s gone a none-too popular reporter from another magazine appears. Apparently, he’s been chasing Sheed for months and I immediately know that his presence just as I’m making some inroads is not a good thing. Sure enough, when Sheed returns, he is even less forthcoming than normal, giving us each a few brief quotes before heading for the bus.

As he leaves, I recall something my junior high coach always screamed whenever someone talked smack or argued with a ref: “Let the ball do the talking!” How ironic, I thought, that someone who disobeys that missive so thoroughly on the court should follow it so religiously off of it. Go figure. In any case, if you really want to know about Rasheed Wallace, the ball has plenty to say. Learn to listen.

April 4, 2013

“God Rest His Soul” – paying tribute to Dr. King on the 45th anniversary of his murder

45 years ago today Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in Memphis. I think it’s important to remember that he was there marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m also sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so.

Gregg Allman wrote this song for Dr. King but it was never on one of his studio releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… Anyhow, I think it’s a great tribute to a great man and the person who put this video together with pics of Dr. King did it justice.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable.

Please pause to remember Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968).

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

March 29, 2013

Why I Write Interview

This interview with me is part of a really interesting “Why I Write” series.

” I do not keep regular hours. That’s why I’m a writer! If I wanted to keep regular hours, I’d go work in an office.’

February 26, 2013

Allman Brothers’ Beacon rehearsal

I had the pleasure of sitting in on an Allman Brothers Band Beacon rehearsal in a Manhattan studio Sunday night for several hours. It was a really interesting and they sounded very good. I am sworn to secrecy on what specifically I heard, but it was a mix of things. They were working up some of their own songs they have not played in years, learning some new covers and also rehearsing a few old standbys. They rehearse like every other band: ”Let’s take it from the top” … “Let’s try the ending again…” “I think we should wait a bar after the solo before the vocal comes back in…” “Can we try that a wee bit faster?”… “Should we bring it down and up or ride it slowly up, up, up?”

They are sounding very good, and Gregg is very much on top of his game and involved with what’s going on in that room. From the relatively little that I saw, I feel secure in saying that people headed to the Beacon in coming weeks are not going to be disappointed. I’m itching to go myself, but won’t be there until Tuesday, March 5.

I have my own gig Friday night in W. Orange - if anyone seing this is coming to town for the Beacon and not going to to opening night, come on by. Mention this post and I’ll buy you a drink.

*

UPDATE: Some followup

My friend Norman Bradford writes, “Lets hear some details, does Warren direct things? How active is Gregg? Does everybody get along? What’s the “vibe”? (Serious or joking around? Etc)”

The basic vibe is loose and seriously interested in getting sh*t done. Gregg was very involved and sounds very strong. Who directs depends a bit on the song. Warren is definitley in the center of a lot, but everything is discussed and different people have different opinions on different songs and sections.

The coolest part is it’s really not that different from every reharsal any of us have ever been in with our favorite bands, except, of course, everyone’s a lot better.

February 23, 2013

China-bound. Beijing and Shanghai dates!

BIG NEWS! VERY EXCITED ABOUT THIS UPCOMING JAUNT TO BEIJING AND SHANGHAI – PLAYING MUSIC AND TALKING BOOKS

WOODIE ALAN REUNION SHOWS AND LITERARY FEST APPEARANCES

SHANGHAI INTERNATIONAL LITERARY FESTIVAL:

•MARCH 15, 7 PM Appearing on a panel for the launch of Unsavory Elements, an Anthology of Expats in China Glamour Bar, M on the Bund, Shanghai

Also on the panel: Matthew Polly (author of American Shaolin), Mark Kitto (author of China Cuckoo), Derek Sandhaus (author of Tales of Old Peking) and Nury Vittachi (author of The Curious Diary of Mr Jam), along with editor Tom Carter and publisher Graham Earnshaw of Earnshaw Books.

RMB 75, includes drink. Shanghai Glamour Bar, 7/F, No.5 The Bund (corner of Guangdong Lu). Tel: (86-21) 6350-9988. Advance reservations encouraged!

•MARCH 15, 8 PM Ford-sponsored Big in China book talk, Woodie Alan gala reunion show Glamour Bar

RMB 100, includes drink. Shanghai Glamour Bar, 7/F, No.5 The Bund (corner of Guangdong Lu). Tel: (86-21) 6350-9988. Advance reservations encouraged!

BEIJING INTERNATIONAL LITERARY FESTIVAL:

MARCH 17, 11 AM Appearing on a panel for the launch of Earnshaw Books Anthology of Expats in China

Also on the panel: Matthew Polly (author of American Shaolin), Audra Ang (author of To The People Food Is Heaven), writer Matt Muller, and Kaitlin Solimine (author of Empire of Glass), along with editor Tom Carter and publisher Graham Earnshaw of Earnshaw Books.

RMB 65, includes drink. Capital M Beijing, 3/F, No.2 Qianmen Pedestrian Street (just south of Tian’anmen Square).

Tel: (86-10) 6702-2727. Advance reservations encouraged!

MARCH 17, 9 PM Woodie Alan gala reunion show with many guests Jiangu Jiuba, Beijing

This is my favorite club in Beijing and I’m really excited about it. RMB 60 at Door, RMB 50 in advance

地址:交道口南大街东棉花胡同7号

小站:http://site.douban.com/jianghujiubar/

微薄:http://weibo.com/jianghubar

电话:64015269,18610087613

Mail: Jincanzh@gmail.com

February 19, 2013

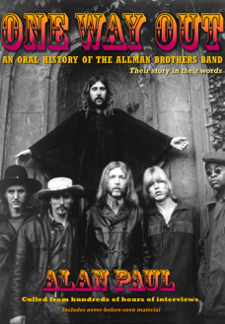

St. Martin’s to release One Way Out as a full-length hardcover book

“If you want to know the real deal, read Alan Paul. I learned a lot reading One Way Out.”

-Oteil Burbridge, the Allman Brothers Band

“No journalist knows the ins and outs of the Allman Brothers Band better than Alan Paul.”

-Warren Haynes

I am proud to announce that St. Martin’s will be publishing a greatly expanded hardcover version of One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band in March, 2014, to coincide with the band’s 45th anniversary. The book will be up to 5 times longer than the original Ebook version and far more in-depth. The entire design, including the cover will be new.

I have been working furiously for the past six months, crafting what I hope will be the ultimate word on the greatest band in rock history. Since the publication of the Ebook, I have interviewed the following, some several times: Butch Trucks, Jaimoe, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Chuck Leavell, Johnny Sandlin, Jonny Podell, Bert Holman, Mike Lawler, David Goldflies, Kim Payne, Stephen Paley, W. David Powell, Rick Hall, Bunky Odom, Don Law, Michael Caplan, Col. Bruce Hampton, Mama Louise Hudson, John, Scoots and AJ Lyndon, Linda Oakley, John Scher, Kirk West and Johnny Neel.

Many, many more interviews are in the works. I’m not quite ready to share who is writing the Foreword, but it’s a band member and it’s going to be great.

The book will also include at least 50 photographs, including many never-before-seen images. I am still working out rights and details, so can’t get more specific at this time, but the book will feature great work by great artists.

I will be taking the current Ebook version of One Way Out down by the end of March, to clear the plate for what is to come. I am incredibly excited about this project and look forward to sharing it with you all. Thanks for the interest and stay tuned for updates.

ABOUT THE BOOK:

One Way Out is an oral history of the Allman Brothers Band culled from hundreds of hours of interview, all conducted by award-winning author and journalist Alan Paul, of Guitar World magazine.

The book includes many never-before-published interviews with band members Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Jaimoe, Butch Trucks, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Oteil Burbridge, the late Allen Woody, Jack Pearson, Jimmy Herring, plus Eric Clapton, Tom Dowd, Phil Walden, Rick Hall, Billy Gibbons, Dr. John, Scott Boyer and others.

It also includes: a highly opinionated discography with short reviews of over 50 albums from the ABB, Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Gov’t Mule, Derek Trucks Band and more.

One Way Out is the most complete exploration of the Allman Brothers music yet written and makes for a great companion read to Gregg’s best-selling memoir My Cross to Bear. It tracks the band’s career arc from their 1969 formation through their historic 40th anniversary star-studded Beacon run, right on up to today. The book is filled the musical and cultural insights that only these insiders can provide.

One Way Out includes the most in-depth look at the acrimonious 2000 parting with founding guitarist Dickey Betts; an intense discussion of Dickey Betts and Duane Allman’s revolutionary guitar styles; thorough behind-the-scenes information on the recording of At Fillmore East, Layla, Eat A Peach and other classic albums. You will not find this information anywhere else.

“Alan Paul is one of America’s foremost experts on the Allman Brothers Band. For the past 20 years, he has written informative, comprehensive articles on the band, and he truly understands the essence of their significance. It’s great to see him release this chronicle.”

-E.J. Devokaitis

Curator / Archivist

Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House