Alan Paul's Blog, page 45

June 15, 2012

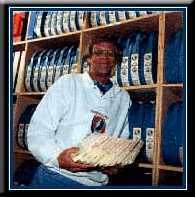

An interview with Dick Latvala: Dick’s Picks and more…

Please check out my new book One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band.

Tricky Dick

In this 1997 interview, Dick Latvala, Grateful Dead tapemaster and father of Dick’s Picks, reflects on how he turned his hobby into a job.

I conducted the interview below with Dick Latvala on the phone, in 1997. [NOTE: This intro was written in 2000.] We spoke for a long time and had a nice, somewhat rambling conversation. Not surprisingly, we hit it off, and I was truly fascinated by Dick and his passion. It amazed me that someone as spaced out as he obviously was could keep 1,000 versions of “Dark Star” straight in his mind.

I conducted the interview below with Dick Latvala on the phone, in 1997. [NOTE: This intro was written in 2000.] We spoke for a long time and had a nice, somewhat rambling conversation. Not surprisingly, we hit it off, and I was truly fascinated by Dick and his passion. It amazed me that someone as spaced out as he obviously was could keep 1,000 versions of “Dark Star” straight in his mind.

This is something that has always fascinated me any time I speak of such things with compulsive tape or memorabilia collectors. It is a part of my personality that is completely absent. I have no idea how many Allman Brothers shows I’ve seen, for instance, though I am often asked. More than 20 and 100. I don’t keep ticket stubs, I don’t save my VIP passes, or file away my laminates (though anyone who ever peaks at Ebay knows I’m a fool).

I generally experience the show and move on. I almost always love “You Don’t Love Me” but I have no clue if I heard a better one at Jones Beach in ‘92. My brain just doesn’t function that way. I see advantages and disadvantages to each way of being, so I’m not bragging – just explaining why it fascinates me to talk to someone who could literally devote their life to seeking out the ultimate “St. Stephen’s.”

Dick and I hit it off and exchanged a series of emails over the next couple of years. Last March we finally met, at one of the Brothers’ Beacon shows. It was intermission and I had drifted down to the basement, directly under the stage, to procure a cup of coffee. There I saw a disheveled, middle-aged guy stumbling down the stairs from stage left heading directly toward me. I approached Dick, extended my hand and introduced myself. He shook it limply, his eyes far away. A little memo pad and pen sat in his shirt’s breast pocket.

“Enjoying the show, Dick?”

“It’s fucking great,” he said. “Unbelievable! But I’m flying way too high to really talk right now. Great to meet you, though.”

He then wandered away, towards the safety and security of his shepherd, my friend the tour mystic Kirk West.

After the show, we met up again backstage and he was now considerably more grounded. We chatted a while before walking out the backstage door together. As we approached the frigid New York air, he zipped up his way-too-thin windbreaker and pulled a hat down over his ears. He pulled a menthol cigarette out and lit it, standing smoking, hunched against the cold As he got ready to climb into a waiting van to go back to Kirk’s hotel couch, he asked if he’d see me the following night.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “I have a one-year-old son so it’s kind of hard to get out too much.”

I was just being honest, but many snort at such sentiments; rock and roll isn’t about raising kids properly. But Dick’s answer surprised me.

“That’s great,” he said. “It’s a fucking blast raising kids. My son is 22. It never ceases to be fun and amazing. They can amaze you every day.”

“That’s true,” I replied. “And you know what? My boy really likes the Allmans already.”

I thought this was a pretty amazing fact, but Dick didn’t. “Of course he does,” he said. “Keep playing him great music, man. My kid had no choice but to love the Dead, because his old man was so crazy, playing it all the time. It’s a great trip, man. Enjoy it.”

And with that, he pulled his thin, shivering body into the van and gave me a wave. I told him I’d see him soon, and headed off towards my car. Five months later, I was taken aback to learn that he had a heart attack and had died at age 56.

It would be a stretch to say that we were friends, but Dick and I had our moments and I cherish them, because he was one of the all-time great characters, an American original.

***

“I’m the proverbial kid in the candy store,” Dick Latvala exclaims with a chuckle. “I’m a guy who is lucky enough to have been chosen to turn his compulsive hobby into a profession. If I didn’t have my job, I’d be doing almost the same thing for free.”

Latvala, a self-described “full-fledged Deadhead” since 1966, has for the last 15 years been on the band’s payroll, hired to archive, label and clean up the band’s huge tape vault. For years, he blissfully labored in obscurity. Then, in 1993, Grateful Dead Records launched Dick’s Picks, a series of sonically enhanced CD’s of the band’s greatest performances from every stage of their 30-year career—as chosen by Latvala. Suddenly, he was a celebrity in Deadland. And with Jerry Garcia’s 1995 passing and the band’s subsequent retirement, the series has gained even more prominence.

Dick’s Picks, which currently averages three volumes a year, has released nine sets (simply titled Volume One, Volume Two, etc.), plus a single-CD Allman Brothers album, all available mail order only. All of the material is culled from two-track recordings (reels, DATs, cassettes or videos) pulled from the tape archives Latvala has come to know so well. The sound achieves the sort of sonic grace previously unavailable on the myriad bootlegs and home tapes that Deadheads have long traded with the eager enthusiasm of 11-year-old boys swapping baseball cards. This has given the series a sterling reputation. But one nagging question remains:

ALAN PAUL: “Who the hell is this Dick we keep hearing about?”

DICK LATVALA: Dick is crazy tape pervert who just seems to have never gotten his fill of live tapes. He found out they existed in 1974 when he lived in Hawaii with a two-year-old son being raised in the green rather the gray concrete of the city. He

discovered live tapes and, boy, he was off and running. There was nothing more important to him. He had no money, but somehow within seven or eight years had acquired 800 7-inch Maxell reels–because he didn’t want to go the cassette route. He wanted the real deal.

AP: Okay, so how did you go from being a fanatical collector to the fanatical collector–the guy on the band’s payroll, sorting through tapes.

LATVALA: It all started when I met Kid [Cadelerio, Dead roadie] at Red Rocks on August 12 ‘79. I was just a consumer. I had just been another face in the crowd, since I had my first trip with the Grateful Dead, on January 21, 22 and 23 1966, at the Trips Festival in San Francisco. I had been a hardcore Deadhead since then, and everything started to change when I happened to meet Kid backstage.

Then I started meeting more and more people on the inside, one thing led to another and suddenly I had Phil Lesh’s attention and asked him, in a concerned way, as a fan, “Is anybody taking care of these tapes?” I wanted to play him what I call primal Dead–great old tapes–so I said, “Sit down Phil and listen to this.” He actually did, and we went through two or three cassettes in three hours. Man, he was real impressed and realized that maybe some care had to be taken of these things.

AP: What did you play him?

LATVALA: Just stuff from my tape collection.

AP: At that point, what was the status of the band’s official tape archives?

LATVALA: Well, it all started with our saint and legend Bear who had the impulse to do it all and record them. He took care of the tapes, then he went to jail in 1970 and things fell asunder. No one cared. It’s hard for people to understand that back then the only reason they kept recording after Bear left was because of the tradition he had to set up. It wasn’t because they wanted to accumulate accurate recordings they some day could release.

For a while, Bear wasn’t in jail but he couldn’t leave the Bay Area as part of his trip, so he would continue to record the band while they were home, but when they went on tour the shoes were either taped, or they weren’t. There was no order. From July of ‘70 to December of ‘70, there really weren’t any tapes except for Harpur College, which has always been around. All those tapes are missing, though I know they were recorded, and we are getting access to many of them, most importantly 9-19-70, which is one of the best “Dark Star” through “Lovelight” jams there ever was. That’s tremendous stuff, and we didn’t have it in the vaults.

AP: That is somethi

ng that blows my mind: that after listening to every performance the band’s ever done, it is still clear to you when you hear a great “Dark Star.” Doesn’t it all start to turn to mush?

LATVALA: No. It depends on how much of it you’re doing. It’s like any other drug. If you abuse it, it will abuse you. If you listened to 69 Dark Star/St. Stephen/Love light” jams back to back, you would get really desensitized to it. It would sound the same and you wouldn’t pick up the uniqueness. But when you listen to a whole, you will put one on that’s spectacular and say, “Wow, something went by. That’s the same jam, but it’s really, really good.” You can catch that, even in a numb state. Those things happen all the time and will continue to happen.

To me, there’s still a discovery stage, because I haven’t heard all these shows. I’m in a state of learning, and I don’t have any set-in-stone ideas about what shows or even what eras I want to pursue. We’re all just another one of those guys with an idea. We all have an opinion, and I’m interested in everyone else’s opinions, too. That’s Dick. I want everyone to be able to have the same experience through the music as me. It’s important to get it out. That’s who I am. That’s my compulsion. I can’t do anything about it. It’s like destiny.

AP: Well, you’re working in an area where a lot of people have very strong opinions. I assume you get a lot of input from fans.

LATVALA: I’m swamped with input. I want input, but I am so far behind on what I got here that I can’t keep up with what people are sending me.

AP: Last year, you worked on an Allman Brothers CD, which is the first and only Dick’s Pick for a band other than the Dead.

LATVALA: Yeah, to hook up with the Allmans was like a dream come true for me…the Allmans and the Dead to me are the only bands that ever said it the way I wanted to hear it. And they’re still doing it. They’ve been my favorite band since 92, when I first got wind of the regrouping and went to see them and was just blown away. They were–and are–the hottest band on the planet. Certainly hotter than the Dead was at that point.

AP: You know, around that time, I stopped going to Dead shows for that very reason, which I sort of regret now.

LATVALA: Oh, you didn’t miss anything. They were bad.

AP: It seemed that way to me, but…

LATVALA: Oh you were right. Try listening to it all on tape. It’s kind of hard to find something that will get your juices flowing if you’re somewhat critical, like most picky Deadheads. I have a hard time finding great things for myself in ‘94 and certainly in ‘95.

AP: When do you think was the last great period for the Dead?

LATVALA: That’s a real toughy. Everyone will agree that ‘89-’90 was cool stuff, all multi-tracked for consideration of the Without a Net CD, and several things from then have come out. Then Bruce [Hornsby] joined in ‘91 and that was pretty thrilling stuff. But in ‘92 and ‘93, I started losing my thrill with it. Going to shows became a habit or something.

I think maybe the end for me was just after [Bill] Graham died [in October, 1991]. Those shows they did in Oakland were really great. That memorial they did for him in the park sort of felt like the last time I remember experiencing something great. But I must say that even in the later years when most shows were so bad, I come across some spectacular evenings, like 3-23-95 or 3-18-95 at the Spectrum. Now those are really great shows. And, yeah, I saw a couple out here in 94 and 95, I guess, but it wasn’t as consistently there. Throughout history, there’s been great shows and bad ones–or numbing, not happening ones — and I can definitely say in my heart they seemed to not have as many winners as the years went on, from the beginning to the end. It sort of declined in the last 10 or 15 years. But that’s just my bias. A lot of people who lived through it had a great time and who’s to deny that? I’m just saying from my perspective it wasn’t happening as much as we left the 70’s. That’s pretty much where I ended on a nightly basis.

But let me say that I have favorites to the very end, so I’m not saying they died in 1977 or something. You have to be a real picky Deadhead and listen to everything. Then you’re defined as being crazy because you don’t do anything else. So I’m crazy. I’m just compulsively crazy.

AP: How did the Allmans release actually come about?

LATVALA: Well, we had this tape of the Brothers opening for the Dead, which Bear had recorded, just on a hunch. And then I met Kirk West, whose like my counterpart with the Allman Brothers and bam. We were like instant soulmates, karmic buddies and all that. So we decided to do this together and it was great fun, man.

AP: What is the process of something becomes a Dick’s Pick, from beginning to end.

LATVALA: It’s a complex question. I don’t have an agenda. I don’t have things I want to get to or something. I have like a broad, slim grasp of certain periods and certain shows within that period, an awareness of them, but they demand re-listening. I have a flimsy grasp of all the eras and ideas within each period of what would be a good show to think of, but what really determines it is where we are right now. We don’t have them stacked up on the shelves waiting to be mastered or something. I’m constantly listening and trying to figure it out, and a lot of it is determined by what the previous one was. We are always trying to create. I have to get the agreement of two other people: John Cutler and Jeffrey Norman. The three of us have total control and veto power.

AP: So the band has no input, which wasn’t always the case.

LATVALA: No, it wasn’t, and it took a long time to get here. Phil played a role, and it was a log-jam type role. He was an obstacle. I’m not bad-mouthing him, but his sense of good music is really refined as he says, so refined that we would never hear it out here in Deadland if he were left in charge. And I realized that a long time ago. It was hard to get things past his veto power and I didn’t think he gave things a fair listen and how could he want to: it’s not logically possible to be both the judge and the creator.

He tries hard and he really likes the music, but he’s very critical, like everyone on the inside. And they don’t know how it is being on the outside. The mindset of the people who put the shows on and those who go buy a ticket is so fundamentally different. The band themselves don’t have a sense of things, and I found this out after a lot of years of pain and frustration. I realized that I wasn’t wrong–they just don’t understand. Everyone has his own agenda, and it can overshadow the important thing, which is to capture a great performance. They listen to it and think, “Oh, I’m not mixed loud enough…I missed a note there…I’m a half-step off on the turnaround.”

A performer can drive themselves nuts with that type of close analysis. What they need to do is jus let it go and find someone they trust, then trust in them to do it right.

AP: And that’s you. Now that you three have full control, do you think the band listens to your work?

LATVALA: No, I don’t think they do. They’ve never commented on them. In my dreams. Or it used to be mine. Certainly Jerry isn’t listening. [laughs] I don’t think Weir would ever listen to them and Phil I seriously doubt ever has since he hasn’t had to any more. Billy would never listen, and I don’t think Mickey would. I would bet everything I have that not one of them has ever heard one of them.

AP: A friend of mine says they are like adult baseball cards. If you’re a collector, you’re a collector and you must have every one.

LATVALA: Oh, of course. I would think so, too. If I wasn’t who I was, but who I used to be, I’d be out there getting everything that the Grateful Dead released.

AP: Now that you’re on your own, you guys seem to be on a roll. What’s next.

LATVALA: Well, it’s gonna be great. That’s tooting my own horn, but I know that my team can deliver the goods, man. And it’s an organic process of discovery. It’s not preordained. The first seven were like giving birth and it was utter pain and frustration, almost to the point that I started feeling that I was never going to come up with something that was right with these people. But that frustration has dissipated and it’s a lot easier now, because I have a clue of what level of quality needs to be addressed. I give them good quality stuff to choose from, so then it’s only a matter of the quality of the performance. So if we all agree, it’s good stuff, and it will appeal to more than one segment of Deadheads

AP: Once you make the decision on what show to do, what happens next?

LATVALA: Then we go into the archives and bring out the master in whatever form it’s in, which could be seven-inch reel, DAT, or video, go through it and eq it as needed. And we do the reel flips–there are places where a tape ends in the middle of a song and you have to do something to cover up that reel flip. We keep EQing to a minimum because the idea is to get it as raw as the tape can be but to smooth over any imperfections in the tape. If there’s a problem in the tape, we’ll attempt to solve it some way and it all gets very creative. It’s done on a digital editing system called Sound Solutions. Dick’s Picks is, as you know, only concerned with two-track, so if there’s a problem, you can’t find it in the mix. There is no mix, so you have to be creative.

You can really do some clever editing even within that limited two-track format. I am amazed and thrilled and unbelievably proud about my team’s performance. I think we’ve always made it really beautiful, and some of the edits were enormously difficult; you have a tape flip in the middle of a jam and start on the other side in a verse, for example. Every tape is different, with one constant: there will never be studio-quality sound. These tapes weren’t recorded with the intention of being sold later. It’s a hit or miss deal and some of them are misses: the mixes are bad and we’ll never be able to use them. But the hits are great. I think what’s out there is great and there are going to be many, many, many more.

AP:S o you have had tapes where you really liked the performances, but the tapes were just not usable?

LATVALA: Oh yeah. Hundreds. I’ve been beat up and died over things. Harpur College was rejected every time I brought it up for years. From the first time I got involved, I was trying to bring Harpur College to people’s attention and it got beat down every time. It was like a nightmare to me.

AP: What finally led to the breakthrough which allowed you to release the show as number eight?

LATVALA: The slow and gradual success and credibility that came through the success of the first five or six releases. I started to be able to get at more of the stuff that I know everyone wants out there. It’s all working now, and there’s lots more. As the success of these releases keep going, it implies that people want to see more and there is more and more and more…there’s lots. We’ll certainly never use it up in our lifetime. Really, I think we could do more. We’re doing basically three a year, and I think we could five.

AP: When you do these CD’s do you feel that you are trying to recreate a concert experience for people to have in their home?

LATVALA: That’s a complex question. It’s not like we’re here to recreate the show itself, at all. That can’t be done. You need a lot of beautiful girls dancing around you, lots of flashing lights and swirling colors and real people up on stage and lots of flashing lights. You’re listening to a CD at home, alone in front of your speakers. There’s no ambiance. It’s just audio. So you have those limitations. You weren’t at the show? Well, too bad. You missed it. But you can hear a tape of it, which is the next best thing. And there’s a whole lot of Dead shows we as consumers want to hear because they weren’t at them all, though we would have liked to have been.

And it has to be a show. You can’t have it be the best of a tour compilation. That is the Without a Net concept and it doesn’t fly. This type of thing has to be expressed in terms of what happened in one night. When people listen to this 100 years from now, they should think, “This much winning sound happened in one night? Wow.” You got to have a limitation on how much time you’ll use on your fundamental baseline.

I’ve gone to the best of a run in one place, which is stretching things, but to me is sometimes necessary. The goal is to release the whole show, but that is easier said than done, because anything we release has to be right, and it’s hard to find a whole show, where everything is right. But the limitations are constantly loosening as time goes by. I’ve gotten away with more each time, from the master being on a cassette, to it being three CD’s instead of two, to it being a whole show. So now the foundations are laid, where we can get things done, whatever we dream up, almost.

AP: What is the Sonic Solutions?

LATVALA: I am not technically inclined, but it is a digital editing system and they groove on it from a little house in San Francisco. They make these state of the art digital editing systems. It’s the other side of taking razors to tape. You load analog to a hard disc on a digital editor, then you can manipulate things with all these remarkable techniques. It’s not a consumer type of thing yet. It costs a lot of money and it’s just really cool. iI you want to get the best product and best use of what’s on tape we have, that’s the way to go.

I’m blown away by its capabilities. We’re trying on each release to balance what has been done, and what songs haven’t been touched yet and what eras haven’t picked yet. We’re trying to spread it out and not ever get stuck in a rut. Then we have video releases and multi-track releases to contend with, and you don’t want to bump into each other.

When I figure out what the right era is and what year I should be looking for great stuff in, then I find it and that’s based on talking to people all the time and reading through everything on the net. Then I listen through the master and see what the problems are and I think, “How are they going to solve that? They are in a great instrumental passage at the end of China Cat there and when the reel flips they are in verses. How are they gonna solve that?” It always gets solved. Jeffrey is the main manipulator of the tools and he’s brilliant.

AP: On the more current shows, why does two-track even exist?

LATVALA: Two-track then is in the form of DAT or Beta or VHS tape. Theynever multi-tracked every show, except for limited periods which were financed by the record company to make a live release, from Live Dead to Without a Net. These opportunities for multi tracks were always within the context of material that’s gonna be used for an upcoming live release. For instance, the Fillmore releases on Arista were recorded for Live Dead. It’s like a rough draft of that album. They never thought they would release the whole shows, but that is exactly what I intend to do some day. Those were the classic four shows in history: 2-27, 2-28, 3-1 and 3-2 ’69, Fillmore West. That is enormous tuff.

I was there and those shows are the reason I got into live tape, because I wanted to hear something. It was the most intense thing in the history of my life and I went on a quest to hear it again. I finally heard those shows and they were as great as I thought it was. That is a perfect example of something that seemed huge and I listened to the tapes and it was.

AP: Have you had the opposite happen, where you thought a show was life-changing, then you hear the tape and it sort of sucks?

LATVALA: Sure. Then you go, “Well was it the drugs? It must have been, because this show sucks.” Then again, someone else might love it, because it’s all subjective. It’s just one man’s opinions

AP: You have managed to turn your passion into a profession.

LATVALA: Yeah, and that is really a miracle, isn’t it? I am so lucky that this happened. I just think I’m in a dream if I look at it straight on. There are enough painful experiences that go along with this trip that it keeps me in reality. It ain’t all gems and roses. At times, it’s been really horrible. Of course, a lot of other things in my life contributed to feeling terrible, like having my mouth fall apart and all my teeth fall out.

AP: Do you go back and listen to the CD’s once they come out?

LATVALA: No, I burn them out. I have heard them too much. They die for me to be set free to the public, although enough time has passed that I’m ready to go back. In fact, I’d really like to hear number two right now. Can we finish this up so I can go put it on, please? I need a dose of meditation.

_

<A HREF=”http://ws.amazon.com/widgets/q?rt=ss_... Widgets</A>

June 14, 2012

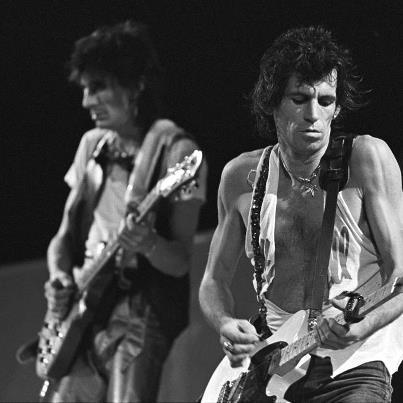

Kirk West, music photographer – great pics by a great friend

Keith and Ron Copyright Kirk West Photography

Many know my dear friend Kirk West as an Allman Bros expert. He is also a killer photographer. His great rock pics are coming online – and will finally be able to be viewed and purchased. A fully interactive website with a vast collection of classic shots available for purchase is coming soon. He has kicked it off with a slide show at www.kirkwestphotography.com. Check it out.

June 5, 2012

One Way Out – Jamming with Andy Aledort

Andy Aledort has been my friend and Guitar World colleague for almost 20 years. He has also been one of my very favorite guitarists – and that’s no hyperbole. He has been Dickey Betts’ indispensable right hand man in Great Southern for almost a decade now and has also appeared with the Allmans at the Beacon (true mecca gig), played with Buddy Guy and Johnny Winter, ghosted for Jimi with the Band of Gypsys and for Stevie with Double Trouble. He’s given lessons to Joe Perry and played trad jazz with the cats from Woody Allen’s dixieland band.

I could make a pretty persuasive argument that Andy is one of the most influential guitarists of the past 230 years, having pioneered tablature and excelled at giving lessons in print, on DVD, on TV, etc. He has taught the world how to play.

Every opportunity I have had to play with him has been a stone cold delight. While I have sat in with his excellent Groove Kings band several times, a few weeks ago I had the pleasure of Andy playing a full night of music with my Big in China band for the first time. The two videos below are all the sonic proof I have of what I know in my soul: it was a great night. “Little Wing” was a little rough as we had never played it before as a band. Wish I had some clips of us playing more of my music together, but very happy for what I got.

“One Way Out”

A very rough, very incomplete clip of “Little Wing”:

June 4, 2012

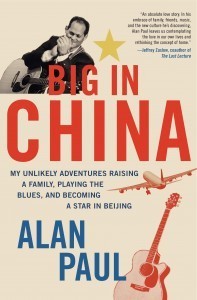

Big in China band at Suzy Que’s BBQ – Sat. June 9

The Big in China Band will return to Suzy Que’s Barbecue in West Orange this Saturday, June 9, with a Family-friendly start time of 8:30.

Due to the vagaries of five summer schedules, this will be our last performance for a while, so come on out for our usual fun mix of blues, originals, Dylan, Dead, Allmans and more.

Special guests expected.

Reservations recommended – tell them you are coming to see the band to get a table in the front. Call (973) 736-7899

WHAT: Big in China Band Live

WHEN: Saturday, June 9, 8:30 pm – 12:00 midnight

WHERE: Suzy Que’s Barbecue

34 S Valley Rd, West Orange, NJ 07052

June 2, 2012

Big in China excerpt: Teaching “Tight but Loose.” Introducing my Chinese bandmates to the Allman Bros.

A little background before we get to the excerpt, which is inspired by new Ebook One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band:

A little background before we get to the excerpt, which is inspired by new Ebook One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band:

I never could have guessed that the blues guitarist collaborator I had sought for years was waiting for me in Beijing, but he was – and I never would have found him if not for a broken guitar.

Occupied with settling down and helping my three kids, aged 2, 5 and 7, get their feet on the ground, I barely touched my guitars my first year in Beijing. To inspire myself, I bought a new guitar during an extended summer visit home to the US. It was a beautiful tobacco sunburst Epiphone 335 to mimic the vintage Gibson I had left with my brother for safekeeping. When I opened the case back in Beijing, the headstock was dangling off. I felt like crying, but it turned out to be one of the best things that ever happened to me.

A friend told me that Woodie Wu, a young Chinese guitarist who had recently returned from three years in Australia, could solve my problem, and he did — but I got back much more than a fixed guitar.

Woodie and I hit it off right away. When I saw the huge Stevie Ray Vaughan tattoo on his left arm, I knew we could do business. When I found out that he wanted to jam and was now focusing on lap steel guitar, I was thrilled; the sound of slide guitar has touched me deeply since the very first time I heard Duane Allman play.

I jammed once with Woodie’s band, and we discussed playing together more, but nothing quite happened. Then, two months later, I saw Eric Clapton in Shanghai, and spent the day eating dumplings and perusing antique markets with guitarists Doyle Bramhall 2 and Derek Trucks for a Guitar World story. My passion for music fully reignited, I contacted Woodie again; I needed the sound of his slide in my life.

I had already had a couple of memorable jams with American saxophonist Dave Loevinger and his playing also moved me greatly. I heard a sound in my head with Dave’s soulful sax in one ear, Woodie’s weeping slide in the other and my own voice and guitar in the middle. I wasn’t sure if it was an insane or brilliant vision, but became convinced of the latter after just one raggedy but promising trio show. We played about a dozen gigs with a few different rhythm sections before Woodie brought in bassist Zhang Yong and drummer Lu Wei.

Lu Wei fired us up with passionate, raw-edged drumming, while Zhang Yong brought not only rock solid, funky basslines, but also a composer’s knack for memorable melodies. We started rearranging all the cover songs that we were playing and quickly began writing our own material. I had a hard time explaining to the guys how we had to loosen our sound back up after we had tightened it beautifully with new arrangements and intense rehearsals. “Tight but loose” was an obvious concept to me, but one I struggled to have my Chinese bandmates understand.

When we were working out songs, they would ask how many bars a solo should be and look a bit blankly when I responded by saying things like, “Let’s call it 24 bars, but if you’re not feeling it, cut out at 12 and if you’re inspired, give a nod and keep going.”

The story that follows, excerpted from Big In China, illustrates how I stumbled upon the missing piece we needed to really break through and find our own voice: the music of the Allman Brothers Band.

Just a few months after this encounter, we were named the Best band in Beijing and were hard at work recording Beijing Blues, our debut CD, which has earned praise from Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, Joe Bonamassa, Col. Bruce Hampton and blues legend Charlie Musselwhite.

***

The band began meeting regularly at our new rehearsal space, a studio inside drummer Lu Wei’s duplex apartment in Tongzhou, on Beijing’s eastern fringes. To get there from my place, you drove out of town, through some countryside, then reemerged in a sea of high rises. It was a reminder of just how sprawled out Beijing was.

Tongzhou was a satellite city with over one million residents, but few foreigners even knew it existed. The first time I went there, I hired a driver, the second time a friend who speaks excellent Chinese accompanied me and spoke to Lu Wei all the way. After that, I drove myself, feeling proud every time I arrived at my drummer’s rundown compound, which had weeds sprouting through the concrete and disinterested young guards who just waved at me.

As distant as the place felt, Lu Wei’s house was immediately recognizable as a slacker band crash pad. I could have been in Ann Arbor or Austin. A couple of roommates lounged on a little couch in the middle of the day watching soap operas with their girlfriends. A small drying rack sat in the living room hung with laundry, including a pair of leopard-spotted panties. An overflowing ashtray sat on the coffee table and a stack of Chinese drum, bass and guitar magazines sat atop the upstairs toilet.

The Woodie Alan Band

One bedroom on the second floor had been converted into a studio, with a big sound system, nice monitors and multiple microphones. Here we transformed Woodie Alan into a real band, ironing out the details of six new songs and transforming “Beijing Blues” from lyrics atop a blues progression into a real composition, which quickly became out theme song.

I offered Zhang Yong a lift home one night after a late rehearsal. As I started up my van, the sound of prime Allman Brothers boomed through the stereo. I always loved the sensation of blaring uber-American music while driving through China and had been listening to a vintage recording at high volume on my way there.

Zhang Yong’s face lit up when he heard “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” a monumental instrumental penned by guitarist Dickey Betts, whom I had interviewed many times.

“This is the Allman Brothers,” I said in Mandarin. “Do you know them?”

“No, but I like,” he replied in halting English. We listened without speaking for A few minutes as the music washed over us—utterly familiar to me, amazingly fresh and foreign to him, even though it was almost 40 years old.

“Two drums?” he asked.

“Dui.” (Correct.)

“Two lead guitars?”

“Dui.”

I clicked ahead to “You Don’t Love Me,” an original take on a traditional blues, with Gregg Allman’s whiskeyed blues vocals leading into inventive guitar soloing. He was listening intently, astounded by what he was hearing.

Zhang Yong

Next up was the sweet, country-tinged “Blue Sky,” with Betts’ high, lonesome vocals leading into one of my favorite guitar solo sections in all of rock, as Betts and Duane Allman take flight separately before swooping back down to hit heavenly harmonies. Zhang Yong turned to me, grinning madly.

“Wow. Good! Different band?”

“Bu shi! Yi yangde!” (No, the same!)

“Oh wow. Two singers!”

We listened without speaking for a while, then he simply said, “Oh, so good.”

It would be unthinkable to come across an American rocker of Zhang Yong’s age and talent who did not know the Allman Brothers’ music, which had so permeated classic rock radio. Turning him onto it felt fantastic. My musical connections with my Chinese bandmates had been so easy and complete that I had forgotten about the vast differences in our backgrounds.

No wonder I had not been able to quite communicate what I wanted, or explain what I meant by “staying tight but loosening up.” I was trying to describe the Allmans’ music. It was grounded in the blues and built around perfectly executed riffs and licks, but the solos headed off on wild rambles, always managing to parachute right back onto the riff. That was the kind of approach I wanted us to take.

I burned three CDs of my favorite Allman Brothers tracks and handed them out at our next gig. A week later, Zhang Yong came to rehearsal and started playing and singing “Statesboro Blues,” one of the Allmans’ best-known songs, written 80 years ago by Georgia bluesman Blind Willie McTell.

“He wants to do this song,” Woodie said.

“Statesboro Blues” made the transition from 1928 Georgia to 2008 Beijing with ease and we worked it up as a duet with Zhang Yong singing the first two verses and me taking the last two. Woodie also immersed himself in the Allmans music, altering his entire conception of what he could with the lap steel guitar. “I need to take it further,” he said. “Now I hear all the possibilities of the instrument.”

Woodie was inspired by The Allmans’ young guitarist Derek Trucks, whom I knew well, having written many stories about him, starting when he was a 12-year-old prodigy. Seeing Trucks perform with Eric Clapton in Shanghai had inspired me to want to play with Woodie, who has now being inspired by his brilliant playing. And the Allman Brothers, who had ignited my love for music, were now inspiring my Chinese bandmates. There was some sort of poetry at work here.

Excerpted from

Big In China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising A Family, Playing The Blues and Becoming A Star in China (Harper). Copyright 2011 by Alan Paul.

// ]]>

May 25, 2012

My new Ebook: One Way Out: An oral History of the Allman Brothers Band

One Way OUt: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers band is the result of 25 years of interviews with everyone int he band, plus Eric Clapton, producer Tom Dowd, the late manager Phil Walden and many others. Please check it out here:

http://amzn.to/Lwqq1G

May 22, 2012

One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band

“If you want to know the real deal, read Alan Paul.”

-Oteil Burbridge, the Allman Brothers Band

I am proud to announce the Amazon-only release of One Way Out: An Oral History of the Allman Brothers Band.

It is their story in their words, culled from hundreds of hours of interviews, all conducted by award-winning journalist Alan Paul, starting with pieces for Request and Tower Pulse in ’89 and ’90 and running right through last month’s Guitar World.

The book includes many never-before-published interviews with band members Gregg Allman, Dickey Betts, Jaimoe, Butch Trucks, Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Oteil Burbridge, the late Allen Woody, Jack Pearson, Chuck Leavell and Jimmy Herring, plus Eric Clapton, Tom Dowd, Phil Walden, Billy Gibbons, Dr. John, Scott Boyer, Buddy Guy and others.

One Way Out is the most complete exploration of the Allman Brothers music yet written and makes for a great companion read to Gregg’s best-selling memoir My Cross to Bear. It tracks the band’s career arc from their 1969 formation through their historic 40th anniversary star-studded Beacon run, and is filled the musical and cultural insights that only these insiders can provide.

The book includes the most in-depth look at the acrimonious 2000 parting with founding guitarist Dickey Betts; an intense discussion of Dickey Betts and Duane Allman’s revolutionary guitar styles; thorough behind-the-scenes information on the recording of At Fillmore East, Layla, Eat A Peach and other classic albums. You will not find this information anywhere else.

“Alan Paul is one of America’s foremost experts on the Allman Brothers Band. For the past 20 years, he has written informative, comprehensive articles on the band, and he truly understands the essence of their significance. It’s great to see him release this chronicle.”

-E.J. Devokaitis

Curator / Archivist

Allman Brothers Band Museum at the Big House

Paul’s book Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues, and Becoming a Star in Beijing has earned the praise of Gregg Allman, Warren Haynes and Butch Trucks:

“What a romp. After writing about music for years, Alan Paul walked the walk, preaching the blues in China. Anyone who doubts that music is bigger than words need to read this great tale.” -Gregg Allman

“It’s hard to imagine a better American musical ambassador than Alan Paul. After spent crafting words, he found himself in a situation where words didn’t work anymore and was able to transcend them and make a deeper emotional connection with music. With the help of great local musicians, he bridged cultures with notes. It’s an amazing story.” -Warren Haynes

May 21, 2012

Time to appreciate Chris Bosh – an interview

Chris Bosh explains how his view of the League has changed and much more.

Seeing how the Heat have struggled since Chris Bosh’s injury, it seemed like a ripe time to look back at my interview from earlier this year. Originally run in Slam.

**

In the eyes of fickle NBA fans, Chris Bosh went from being the beloved underdog to a hated favorite. In a revealing interview, the future NBA Champ (yeah, we said it) explains how his view of the League has changed, and how hard he works at getting better.

by Alan Paul

Dropping into a plush chair, Chris Bosh unwinds his long, lean legs and smiles. It’s a bit surreal sitting with him in a New Jersey hotel room, 14 hours after watching him lead a Dwyane- and LeBron-less Heat team to a triple-OT victory over the Hawks on national TV. When the game ended at midnight, I stumbled to bed. Bosh boarded a plane in Atlanta, flew up here, checked into his hotel and slept a few hours. The Nets will be waiting tomorrow night, but now he has a rare moment in this year’s compressed schedule to breathe and reflect.

“Lucky shot,” Bosh says with a shrug, regarding the buzzer-beating, tying three-point bomb that sent the game into OT. But the twinkle in his eyes and the slight smile on the edge of his lips reveal that Bosh enjoyed his moment in the spotlight. His 33-point, 14-rebound, 5-assist performance was the kind of game he put up regularly during his first seven years as the Raptors’ undisputed man. His final year there, he averaged 24 ppg and 10.8 rpg before setting off for Miami as James’ and Wade’s running partner.

The minute he signed with the Heat last summer, Bosh’s public reputation was flipped on its head. The fourth pick in the great ’03 Draft and an All-Star every year since his third season, Bosh suddenly became overlooked, even mocked for being willing to accept third billing in his quest for rings. Last season, Bosh seemed a bit rocked by this change, pulling back from the spotlight. Now he is settling down into his role. Newly married, his wife expecting their first child, Bosh seems comfortable in his own skin and eager for another crack at his first ring this spring.

“Chris has been more aggressive this year in terms of both his play and his role on the team, taking on more vocal leadership,” says Heat assistant Bob McAdoo. “He’s very willing to step up and just very focused on winning.”

SLAM: You took last year’s Finals loss so hard that you could barely walk to the locker room afterward.

Chris Bosh: Yeah, I was almost in shock. I would have laughed if you had asked me the night before if we might lose. I thought we were in the perfect situation down 3-2 with two home games. There was no way we were going to lose! When it hit me that after all the things we went through we were going to lose—those few moments watching them roping off the court, the game ending and the Mavs celebrating—were like a slow death. All I could think was, This isn’t how it’s supposed to go.

I tried to congratulate Tyson [Chandler], who’s a good friend, and couldn’t even talk. He was talking to me and I was literally moving my lips with nothing coming out. I just walked off and took a knee and everything went by in a flash. It was just very painful.

SLAM: Did that pain fuel your off-season workouts?

CB: Absolutely. Every Finals come down to a handful of possessions. I watched every game six-to-eight times and saw I had weaknesses that were exploited, and I vowed that would not happen again. I’m not going to get that far and have people doing things to me and be unable to respond. I’m going to be physically and mentally stronger.

SLAM: Wasn’t it hard to watch those games again?

CB: No. It was much harder going through it all and coming up short. I watched with a remote in hand and I rewound and fast forwarded, froze… I kept going back and forth. I don’t want to run from the truth, and the film doesn’t lie. I’m my own biggest critic, and the only way I’m going to improve is to see what I was doing wrong.

SLAM: So what were those weaknesses?

CB: It’s really an attitude thing, and the goal is just being more aggressive, driving to the basket more. It’s fuel when you’re working out and are exhausted and tempted to do a light day after two really hard ones. Then I think, I’m not the champ. I don’t deserve to take a day off.

SLAM: The late great Dennis Johnson told us that his 0-14 Game 7 in ’78 propelled him. He said, “Success is a great thing, but sometimes failure is, too.”

CB: Absolutely! Everyone talks about success, but what happens before? There’s always something you have to overcome. Life is not going to be sweet all the time. Failure either breaks people or it makes them succeed. You can’t be afraid to get back up and try again, and you really can’t do that unless you acknowledge the failure.

SLAM: Did you anticipate the extent to which you guys would be public enemies?

CB: Absolutely not [laughs]. I made a basketball decision because I just wanted to win. I didn’t expect the backlash, and I don’t think any of us did. You can’t worry about what people say, but… People always harp on athletes being selfish individualists, and then LeBron makes a decision to join with us and he’s attacked because “the great ones win them by themselves.” That’s not true. Even the greatest had 10 other guys who were part of a unit and got it done together. We try to tune all that out and just stay focused on basketball.

SLAM: Is that easier now that you understand that every town you arrive in, the media is out in full force, the stands are full, the team is amped up…

CB: Yes. At first it was like, Man these guys really don’t like us [laughs]. I just couldn’t imagine what was going on. Now I don’t care. The other night I missed a shot and this guy heckled me: “Bosh, you’re a choke artist.” I laughed and gave him a thumbs up. Last year, it would have really bothered me. [Coach] McAdoo is always telling me to just follow my instincts and play basketball.

SLAM: That must have been a bit hard last year coming to such a different offense.

CB: It is different—I don’t have the ball in my hands all the time [laughs]. That did make it more difficult at first, but I took down that barrier and quit worrying. If you want to win, you have to sacrifice and do what makes the team work most efficiently.

SLAM: You also pulled back your public persona, not tweeting so much or doing the fun YouTube videos. Was that a result of all the scrutiny?

CB: To some extent. I don’t miss it. I value privacy a little bit more than I used to. I was doing those things because I just wanted to have fun and show another side of me. Honestly, all of the negative attention we received last year sort of jaded me from the spotlight. I mean, all of a sudden I suck, I’m the butt of all the jokes… and here’s what I found most disturbing: These retired guys from the NBA—this fraternity that we were supposed to be part of—were leading the charge about our alleged failings. They should have been encouraging younger guys.

SLAM: Did all that bring you guys closer together?

SLAM: Did all that bring you guys closer together?

CB: Absolutely. All this noise from the outside is what it is. We can’t do anything about it, but we’re going to lean on one another and help each other through it. We just have to play basketball and keep patting each other on the back. It encourages me to look out for young players even more. An old teammate told me early, “Look out for your guys. This is an exclusive fraternity.” I’ve always believed that, which is why it hurt so much to be attacked by guys we once considered our heroes.

After last season, I wanted to take on a little bit more of a leadership role. I’m getting older and things are coming to me more and I have to take responsibility for that. Experience has taught me a lot, and I don’t want to let that fall by the wayside.

SLAM: One of the downsides of being a top-5 pick is you’re usually going to a bad team, as you did. There you were, a skinny kid weighing…

CB: A solid 210! [Laughs long and hard.]

SLAM: And they trade Antonio Davis and you have to play center. Welcome to the NBA! Was being thrown in the fire positive or negative?

CB: [Laughs]. At the time it was negative, but in the long run it’s been positive. I learned very quickly that the NBA is a very rough place, physically and mentally. There’s no mercy. If you lost by 40 last night, the schedule still goes on; get on the plane and get ready for the next game. One of the hardest things for me as a rookie was watching Georgia Tech go to the Final Four. I remember telling my friends I wish I had stayed in school and they didn’t understand: “You’ve got all this money and everything you want.” But it wasn’t about the money. It was about how I felt right then.

It was just tough. It was the worst. We were losing every night, which was new for me, and I was getting physically and mentally beat up. I was 19 with no friends in the city, there was no one under 26 on the team and I had to learn how to be a grown man on my own. You think you’re grown in college but you’re not, because everything is kind of controlled. You lose the camaraderie and suddenly find yourself alone in an apartment just feeling lost. I would find myself in a hotel room or home after practice just wondering, What do I do now?

SLAM: That’s a lot of pressure to put on a kid’s shoulders. Do you envy the guys on your team now who have the shelter of you three and no pressure to star?

CB: No. Look, there were hard days but I never felt sorry for myself. This is what you ask for; it’s what I dreamed of as a kid playing in the park. This is the spot you want to be in, and if you want to be successful, you are going to have to deal with pressure.

It’s a luxury to play. I get to play basketball for a living. I’m a lucky guy and I’m thankful for everything I have and what I get to do. I realize how many people would give their left foot to just play one game in the NBA. This is the NBA! I want to bring that childlike approach every night—just go out there and have fun. I want to play like a kid, for fun but with intensity. Play to win.

May 7, 2012

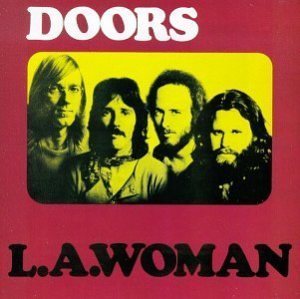

Robby Krieger breaks down The Doors’ LA Woman – final album recorded with Jim Morrison

Originally published in March, 2012 issue of Guitar World.

Originally published in March, 2012 issue of Guitar World.

The Doors were at a low point in December 1970, when they gathered to record their sixth studio album. They had been banned from performing after singer Jim Morrison’s prosecution for exposing himself at a Miami concert, effectively killing their performing career. Their previous album, 1970’s Morrison Hotel, had failed to break out. The group was enveloped in a general sense of doom and decline.

“We were pretty far down – people were saying we were over,” recalls guitarist Robby Krieger. “We couldn’t play anywhere. Morrison Hotel hadn’t done much. Jim was getting fat. Nothing really seemed to be happening and we didn’t have much material when we started the sessions.”

Then things really started to get bad. “Before we even started recording, our producer walked out on us,” recalls Krieger.

That was Paul Rothchild, who had been behind the boards for each of the Doors’ first five studio albums. During pre-production in the band’s rehearsal space – where they would record the album, to maintain a more informal feel -a frustrated Rothchild decided that the Doors were running into creative dead ends, wished them well and walked out. Engineer Bruce Botnick took over the reins, and that low moment became a catalyst for one of the band’s landmark albums – L.A. Woman.

A new 40th anniversary, two-CD version of the album includes alternate takes of “Love Her Madly,” “Riders on the Storm” and the title track, as well as a never-before-heard original, “She Smells So Nice.” Much to the surprise of Krieger, keyboardist Ray Manzarek and drummer John Densmore, Botnick discovered the track, a loose blues jam that segues into B.B. King’s “Rock Me Baby,” while reviewing the album’s session tapes for the reissue.

“I think we came up with an album so loose and cool that it has stood up for 40 years because there was no pressure,” Krieger says. “We figured we were screwed, so we started having fun again. We were so far gone that it was like a weight was lifted when Paul left. He was a great producer and you can’t argue with the stuff we did with him but he was always a very difficult guy to work for. He was a perfectionist and we were looking forward to having the dictator off our back and just having some fun recording for once, which is exactly what happened.

“Before that time, we probably weren’t ready to do something like that – we really needed Paul. But after five albums we all knew how to record and what a good take sounded like and we ended up recording everything in a couple of takes, maintaining a very loose vibe and energy throughout. It was great the way it came together, with everyone chipping in and contributing.”

LA Woman was released in April 1971, but what might have been a new start proved instead to be a farewell. Just three months later, Morrison was dead in a Paris hotel room.

“It’s just too bad that we tapped into on LA Woman didn’t last longer,” Krieger says. “Jim had been pretty uninvolved in some of the albums but he was right in there with us on this, and that’s a big part of what made it so special.”

Krieger shared his memories of some of the album’s greatest moments.

“I’ve always considered this the quintessential Doors song. It’s just magical to me and the way it came about was fantastic. We just started playing, and Jim started coming up with those words, and it just poured forth. Jim was sitting in the bathroom, which we were using as an iso booth, singing. I don’t know how he came up with that whole concept on the spot like that, but he did. You would think that would have been a poem that he had written before, as many of our songs were, but it’s not. That was just written on the spot.

“It’s very natural, and sums up a lot of our best qualities. All the interplay with Ray just happened. We really understood each other at that point. We could anticipate where one another were headed and just play.”

“Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me”

“Marc Benno played second guitar on four of the songs on this session. The idea was I’d be able to play the parts live and not have to overdub the solos, and it really worked. We recorded this live, Marc playing the rhythm, so I could just play the leads, fills and slide. I kind of get embarrassed when I hear it now because it’s so loose; it would be hard for me now to leave something this sloppy on a record now, but I’m glad I did. It‘s part of the charm of the song and of the Doors.”

“Cars Hiss By My Window”

“That was really done on the fly, all live. We wanted to do homage to [bluesman] Jimmy Reed and I just started playing in E and this song just happened. I love it.”

“She Smells So Nice>Rock Me”

“It’s amazing that we found anything new after all these years and all these reissues. We keep looking in those vaults and I guess we’ve never done a thorough job. We always seem to find something. Bruce Botnick found this and I was glad he did. It was a lot of fun to listen to because it’s really typical of the kind of jams we used to do to warm up and get ready for a session.

“It’s also interesting to hear Jim use the ‘Mr. Mojo Rising’ line that he used so famously in ‘LA Woman,’ and which I had not recalled him pulling out in a jam like this. There are different stories about where he came up with it. That witch [Patricia Keneally, who is said to have married Morrison in a Wiccan ceremony] claims to have told him about anagrams and apparently they came up with that one night at her place, but I have never known whether or not that was true.”

“We had some practice sessions and took down a couple of demos and that was one of them that Paul heard, and he hated it. It was one of the things that led him to walk out. The song had come about quite naturally. We were fooling around getting loose by playing The Ventures’ great guitar instrumental ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky’ and it just kind of morphed into something else, through jamming and Ray playing off me. I was playing with this cool tremolo sound that the Ventures favored and kept it going once ‘Ghost Riders’ became ‘Riders on the Storm.’

“I really feel that if you’re a real band, jamming can be the best way to write songs. You discover things and latch onto great riffs and interlocking parts, and we were doing that more and more – with Jim more involved in these sessions. I truly believe that if he had stuck around a little longer, we would have done more and more like this.”

Alternate versions of “LA Woman,” “Love Her Madly” and “Riders on the Storm”

“It’s fun to hear different version of these songs. Finding all that stuff was a big surprise. When we searched our vaults putting together the box set, we found alternate takes of ‘Roadhouse Blues,’ including one that I really preferred and wished we had used. Ever since, we’ve been searching for outtakes and when Bruce called and said he had heard outtakes, I was really excited.

“It’s fun for me to hear them, but hard to say that I prefer any of them over what we used. It’s not as simple as that, because after you pick a take, then you end up refining and overdubbing and it becomes almost a different song.”

“The WASP (Texas Radio and the Big Beat”

“This just has all kinds of weird things in it. In fact, Ray hates to play it because he always forgets it. When you try to play it with people, they always say, ‘That doesn’t make sense… why do you do this here and not go here?’ There’s no explanation. We just kind of knew when to come in, when to get out, when to make the changes and what one another were going to do. Generally, Ray set the pace and we had to follow or it would all fall apart. He just did what he wanted.

“A lot of these songs seem easy to play but they’re not They have extra bars in them or inconsistent turnarounds – things I would never do now that I know more about music, but which helped make them memorable and relevant to this day. At the time, the simplest things could amaze me, like a minor chord going to a major chord.”

“Hyacinth House”

“I had a little house up in Benedict Canyon, which is near Laurel Canyon. Jim and John and a couple other people came over to there one night, and we were just fooling around, taping some stuff. And I had this pet bobcat at the time, which would mostly stay outside, but sometimes it would come inside. But by that time it was getting real big, and kind of dangerous, so I didn’t let people pet it or anything. And that’s where Jim got that line about the lions.

“And ‘hyacinths’ referred to some hyacinth flowers that were right outside the window. And in that line about the bathroom, Jim was talking about this friend of ours who was there, who kept hogging the bathroom all night. Jim wanted to go to the bathroom, and he couldn’t. Finally, the guy got out of the bathroom, and Jim goes, ‘I see the bathroom is clear.’ He wrote the song on the spot, and I think that was how some of the best Doors songs were written. Then we just recorded it on my little Sony four-track, which was a real nice, high quality tape recorder. To call it a home studio is kind of funny, but it was a pretty revolutionary piece of home machinery at the time.

“That pet bobcat was so cute. I saw her in a pet store when she was a cute little kitten and said, ‘She looks just like a bobcat’ and the guy goes, ‘She is a bobcat.’ She was a great pet for about three years and then she got a little bit nasty and I gave her to this weird guy who loved jungle cats and specialized in taking people’s pets that had gotten too big and releasing them into the wilds in the Ventura County mountains but he claimed that she attacked him and he had to shoot her. Poor kitty. But at least she is remembered forever as the ‘lion’ in ‘Hyacinth House.’”

May 4, 2012

Andy Aledort with Big In China: 5-18 in NYC

Jamming with Andy - Photo by Tore Claesson

I am really proud and excited to announce that guitarist Andy Aledort will be joining Big in China at Uncle Mike’s in downtown New York on Friday, May 18. You can see details on the event here.

WHAT: Andy Aledort with Alan Paul and Big in China

WHEN: Friday, May 18 9 PM-1:00 AM

WHERE: Uncle Mike’s, 55 Murray St. New York, NY

Andy is a longtime friend and Guitar World colleague. He also is, truly, one of the World’s greatest guitarists. For the past decade or so, he has played with Dickey Betts’ Great Southern – see the video below of him tearing it up last week on “Liz Reed” and be awed.

I was in the room the first time Andy and Dickey played together for a Guitar World lesson interview to write the first batch of Betts columns. That led to Dickey inviting Andy to sit in and that led to the guitar legend asking him to go back to his hotel room and give him a lesson and realizing that he needed Andy in his band.

Andy has also played with SRV’s Double Trouble and Jimi’s Band of Gypsys – including at the Mt. Fuji Rock Festival. They call him Andy Hendrix in Japan. He has played with the Allmans at the Beacon, given Joe Perry guitar lessons, played bass for Johnny Winter and the entire Experience Hendrix Tribute Tour (he took over when Tommy Shannon took ill)…and this is just the tip of the iceberg.

I have played with his band the Groove Kings quite a few times – including at two Big in China book release parties last March. But this will be the first time Andy joins my own Big in China band. Andy lives on Long Island and while he tours the world, he does not play Manhattan very often. So come on by to hear one of the greats. The videos below provide a taste. Poke around online if you want to hear more.

Andy’s solo on “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” with Dickey Betts and Great Southern. 4-26-2012

“Will the Circle Be Unbroken” with Andy and the Groove Kings, March, 2011. Also features BIC guitarist Dave Gomberg.