Alan Paul's Blog, page 22

May 7, 2016

Allman Brothers’ Jessica – keyboards only

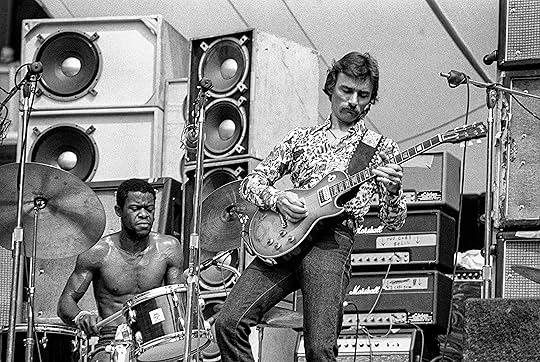

Dickey and Jaimoe – RFK Stadium, 1973. Photo – John Gellman

I thought this was pretty cool. Dickey Betts and the Allman Brothers’ classic instrumental”Jessica” – keyboards only (or emphasized). Obviously, Chuck Leavell is the star here, but pay attention to some of Gregg’s organ licks and harmonies.

March 25, 2016

Susan Tedeschi, Derek Trucks interview

Foto – Kirk West

In this extensive interview, Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks discuss Let Me Get By, working with Leon Russell, the Allman Brothers’ demise, much more.

I love the Tedeschi Trucks Band’s third studio album, Let Me Get By. I think it is their first great artistic statement after six years as a band, a rich, varied collection of songs that glides effortlessly through rock, soul, blues, jazz and Indian musics.

I was excited to interview Susan and Derek about the album, for a feature in the Wall Street Journal. We spoke in their hotel suite in Asheville, North Carolina, the afternoon before they performed at Warren Haynes Christmas Jam. Both were sipping tea and nursing the normal road dog exhaustion, made a bit worse by the fact that Trucks was recovering from major surgery. About two weeks earlier, he had a large benign tumor removed from his spine. The prognosis was excellent but he pretty clearly should have been resting in their Jacksonville home. Instead, he was finishing up a final tour of the year. The band would be piling on their bus after their performance to drive to New Orleans en route to Austin, Texas for a taping of Austin City Limits.

Towards the end of our chat, with my recorder off, we spoke more about Derek’s surgery and how his guitar rested right on his scar. “Show him, honey!” Susan exclaimed, and Derek pulled up his T shirt to reveal two large scars.

Our conversation covered a lot of ground, only a fraction of which made it into the story. I thought some of you would enjoy reading the whole thing.

Here is the full interview, only lightly edited for flow.

**

Let Me Get By sure covers a lot of ground.

Derek Trucks: We just wrote songs and let them go wherever and if it worked, it worked. We didn’t think twice about having a long segue. We didn’t think about stuff like that at all. If it held our attention, that was the only criteria.

It feels like you guys just opened the doors and windows to anything and everything.

DT: Yeah!

Susan Tedeschi: Which all works together without sounding alike. There’s a lot more improv on this record and a lot more diversity in the songwriting.

Certainly in Mike’s songs. And these are his first TTB lead vocals. Did you feel more comfortable with that now that you are more established?

ST: That’s part of it. His voice is so great and it really freshens it up for me.

DT: We had the idea to do that even before we got off of Sony, which opened up a lot of freedom to do whatever we want. And Sony was great for a major label. I couldn’t believe what we got away with. We finished the last record and started thinking about the next one, we were already saying, “We’ve got to have a Mike vocal.”

And on “Right on Time” Sue, you sing very prominent harmony. Did you enjoy that?

ST: I did! I loved it. That’s actually one of my favorite songs on the record.

DT: It’s a lot of fun. There’s something really refreshing when you get to go into the studio and break out weird microphones and think, “Oh cool. Susan is going to be singing a harmony part to Mike on it. How do we want to see it and hear it and feel it?” Those are fun things to do. And it’s pretty amazing with a band like this to think… it’s like having some serious race cars in your garage and you think, “Ok, how are we going to stack this up today?”

Because you can’t be drag racing constantly.

DT: Totally. But it’s nice to know it’s always there when you want it or need it. It’s pretty great to be able to think about a duet with Mike and Susan and still have Mark and Alicia’s voices there, waiting in the wings. Even Doyle was there for some of that.

“Right on Time” is very reminiscent of Tom Waits.

DT: The whole idea was just wherever it goes, we are going to follow. If it gets all weird and becomes a sonic trippy album that’s what we’re going to do. We went down a lot of different avenues and it started to settle in. Me and Mike sat down with “Right on Time” and he had a verse and a chorus and it originally reminded me of Tom Waits and Scrapomatic…

ST … and Leonard Cohen. It’s a great song.

DT: And I added the second chorus to it and it became a little Muppets-like singalong. [laughs]

There are a lot of joint songwriting credits. How does that work?

ST A lot of times it was Mike with a lyrical idea and Derek would work with him on it or Derek and Mike and I would sit around together finishing an idea.. or Doyle would have an idea and he and Derek would go in the studio and build a track and then Mike and I might listen to it and where he was mush mouthing lyrics. There was a lot of different methods of collaboration.

DT: It was really song by song. For “Anyhow,” I was in the house with our daughter and she was listening to some music and I played her the Dolly Parton tune “Jolene” and there was this great acoustic guitar riff on the live version and I started messing around with it and said, “Sofia, what do you think of this?” and it just became the song.

So that one started with the riff, then we started writing lyrics together. Usually it started with the tune and then me and Sue or me and Mike would or two or three of us would get together and say, “Here’s what the concept of the song is…” because usually when you write a melody you already have a feel about it – it feels like something… Usually the music will come together pretty quickly.

So “Anyhow” started with the riff. “Let Me Get By” and “Laugh About It” started with grooves that we played at soundchecks over the last year or two. A lot of really musical things happen then – like Tim starts playing a groove, Kofi jumps on it, JJ would jump in and every two or three soundchecks there would be something we stumble on and all go, “That’s bad ass.” So I realized we were stumbling into some very cool musical sketches and ideas and told everyone if you play something cool, record it on your phone. So one of us breaks our phone out, and you end up with all these 20 or 30-second clips on your phone and there’s a few that you just remember. Those two were riffs where it was like, “Hey, you remember that Raleigh rehearsal?” and everyone does, which mean sit’s good. Then when we’re in the studio we try to restart that.

Smart to capture the naturally flowing musical energy.

Smart to capture the naturally flowing musical energy.

DT And it can come from anywhere. We took a break from recording and I heard JJ singing this melody to Kofi at the piano and it became the chorus for “Don’t Know What It Means.”

[Susan sings the melody wordlessly and we all bop our heads. ]

That was a JJ Johnson melody and then we start singing the melody, which felt very Sesame Street 70s sing-along, and and we said, “What does that sound like?”

And it turned out to sound very much like Sly Stone. Do you think you were influenced by touring with Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings?

ST Probably – but the songs had all been written before that, so not in the way you mean.

What kind of impact did the Mad Dogs and Englishman show have on you?

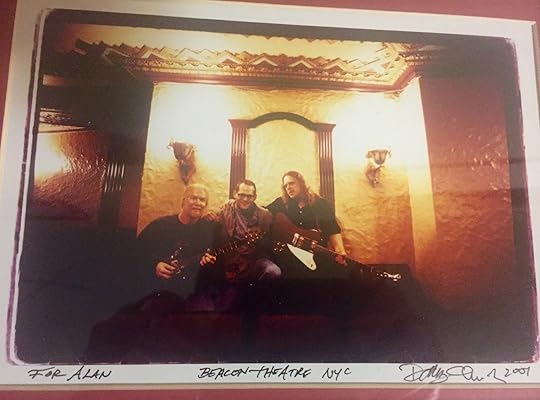

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

DT: A pretty big one. It wasn’t just the show. We had been listening to that for a while and already playing some of the tunes. That whole realm certainly impacted us. One is the material and two is the impact with Leon Russell and all those people…

ST Rita Coolidge!

DT: People are always asking if people we play with give us advice or information or how they impacted us. This time, it really felt when we did the rehearsals and show like it was something bestowed on us. It really felt different. It felt special doing that gig and afterwards, on our there was a different spirit with the band and it’s continued. We’ll play two or three of those Mad Dogs songs every night – changing them up – and it really feels connected to the group now. The show was magic and in way the rehearsals were even more magical, just being in the room when everyone showed up, no one really knew each other. We had met Leon once or twice and he was super complementary about the band

ST: People were magically paired up… like we all go to mics and Alecia was paired up with Rita Coolidge, who was her childhood idol.

I feel like you guys have gotten so much more adept at playing with the large band instead of just laying like you would anyhow, except you have a horn section. Does that make sense?

DT: Absolutely!

ST: Yeah yeah, yeah.

I could hear both in your guitar playing, Derek and your singing, Susan. That’s something you had to adapt to, right?

DT: Totally. Yes, yes.

As a singer, you start out accompanying yourself on guitar, then add a bass and drums, a keyboard, a saxophone, but..

DT:… but you’re not part of the orchestra.

Right. It’s the same basic approach you started with and this is very different. I notice that there are a lot of places where you start a line and let one of the other singers finish it. Which must change the whole way you breathe, because you can start the next line. This is subtle but profound.

ST: Yes! “In Every Heart” does that a lot and yes it really does change the approach entirely. I was singing it the whole way through and Derek suggested, “Honey, why don’t you let them do that line and it frees you up – exactly like you said – to sing he next line.” So I don’t have to take a quick, deep breath so I can get to the next line. I can take my time and phrase just how I want.

Does that then mentally impact how you do everything else? Maybe it gives you a more relaxed vibe.

ST: It definitely affects a lot of songs. I feel a lot of freedom having them there and knowing that they’re going to do certain things and I can play off of them and off of Derek. There’s a lot of space considering there are12 people. We all listen to each other and react to one another. There are little moments where you know maybe the horns are going to be featured here, the guitar and keyboards here, but it’s flexible.

DT: It’s liberating because once you… [pauses and thinks]… I totally think there was a shift somewhere about a year ago. When Tim [Lefevbre, bass] joined the band, that was the first time I thought, “Now I know what this thing is supposed to be.” There were glimpses before that, but it wasn’t the right mix, it wasn’t the right mentality. When Tim came in, that was it. It still took us six or eight months to realize it fully. But now we’ve got a level of trust with the band.. even if you’re doing weird segues shifts or improvisational stuff, you don’t have to fill all the space yourself. You can breathe, lean back and listen and think, “Ok, that’s good.” Then you add when you add and lay back where it feels right. It becomes more orchestral. And you have more great simple moments like you’re talking about, where you can breathe where you want, then the other singers come in and when you come in you can hammer it a little differently.

You start thinking about that instrumentally as well. That’s been a shift and I think like it’s helped me just as a musician to think that way. Even if you are improvising, you are playing parts and it’s got to make it better.

ST: It’s got to add something.

DT: Yeah and sometimes if you stop playing you realize it’s grooving harder without me, so you realize that if you’re going to add something you’ve got to get inside it. You listen harder I think.

Derek, you‘ve become much more physically assertive on stage. Did you make a conscious decision to do that?

ST: He’s walking around kind of conducting things more. He’ll walk around and give people a heads up or look at the drummers and really communicate. You do see him actively communicating a lot more.

DT: I think there are a lot more moving parts in the band and a lot more improvisation going on now where you’re not just playing the arrangements so you’ve got to be locked in and in touch with each other.

ST: Like last night we were playing “Coming Home,” which we haven’t done in forever and all of a sudden at the end I thought I was going to do something and Derek looks over at Elizabeth, our trombone player, and has her solo and it was really cool. We had never done that and it just took the song to a new place, and she and Derek were riffing off each other and the whole band elevated and it took everything to a new place. Those kinds of things happen all the time now.

DT: I think everyone is on their toes more.

ST: Everyone’s like, “Oh shit. Derek might look at me.”

DT: You can’t just learn your part. You have to learn the tune.

Foto – Kirk West

And horn players tend to just live off charts. That’s what they do – read music, play music.

ST: Yeah, but not this horn section.

DT: It is refreshing. Every day after soundcheck you’re walking around backstage and you hear them having a sectional. They’re just constantly hammering it and it’s like, “yeah!” I don’t have to ask. Everyone is just putting in their own time and energy to make it better.

ST: That’s because there’s no bullshit going on. There’s no, “We’re awesome. We don’t have to practice.” Kebbi is thrilled because everyone wants to practice, because he was pulling teeth before. I hate to say it, but, you know, better is better. If you have the right combination of people… like Derek said, having Tim pushed the band to a new level ad we started to go to different places. It’s exciting.

You know what’s really interesting is, every person can change the chemistry of a band. You don’t realize how much one person in a band can really change it. I do feel that there is something special about this edition of the band that is very fun, positive and very unpredictable. You can’t say exactly what will happen each night. You can plan it out, but it’s not going to unfold just like that.

You produced it yourselves, but I feel like you are using the studio more this time, in terms of not just capturing a live performance or doing overdubs to recreate the sound and feel of a live performance.

DT: Yes. Definitely.

For instance, places where you are playing two guitar parts Derek and there’s no attempt to hide that it’s you playing two guitar parts.

DT: That was part of the whole mindset going into it: “Fuck it. Let’s make it sound good… as good as we can.”

ST: Like a record, not a show.

DT: I want to go in there and play and listen back and say, “Cool.” I didn’t overthink that stuff. I remember when I used to write tunes on a cassette tape four-track machine and double and triple track guitars and that stuff sounded cool. I like three –part guitar tracks!

Like on “Laugh about It” and “Right On Time” you have different tones and one part ends and another begins and it’s quite clear.

DT: Totally. What me and Bobby were doing there was real conceptual: “I’ve got this line and I’m thinking maybe we put two acoustic guitars on the side and then an answer line electric guitar up the middle.” We’d go spend a few hours getting the sound and go, “Close, but I don’t think you can tell what it is enough.” It needs to be a little weirder. It needs to have a personality.

“Laugh About It” is triple-tracked guitars. I play an intricate slide line and then play a slide harmony because it’s something you don’t really hear a lot. Usually, slide is a last minute throwaway thing and people aren’t very precise with it so it’s hard to double or triple it up and get the inflections right. And it’s not something that two or three guitarists can really do because it’s so much your own thing – you know where to put the fucking wiggle! It’s easier to do it yourself than to have someone else cop it. That stuff on this record – it hit me that it’s just fun to do. It’s fun to sit with a solo section and work out ideas and concepts instead of just blowing a solo.

ST: And Charlie hit you with some ideas, too.

DT: Yes. My son was listening to all these Beatles records and he had read somewhere that research indicates your left ear can understand diction better than you right here and he goes, “Hey, dad, do you think they do this on purpose? It seems like John Lennon’s lead vocals are in the left side all the time.” And I was like, “I don’t know, but that’s an awesome concept.” And he asked if we ever do that and I said no and he goes. “Well, maybe you should.”

So on one of the tunes we threw Susan’s vocals hard left and then the chorus comes in on the right and it was like, “Thanks Charlie. That’s great idea.” From the mouth of the babes.

A few years ago, when you first used the home studio for the final Derek Trucks Band album, you said, “Duane Allman and Jimi Hendrix showed the way for how to be a great musician, but they left it blank for how to marry that with having a life and a family and being an adult.”

DT: Oh man. I said that? It’s true!

Yes. And the home studio was a big part of your attempt to do that, as was having a band with Sue. Has it worked?

DT: It has. It really has. This time of year, we’re thinking about what are we going to do next year. We’re thinking about band bonuses… you actually have a moment to take stock of what happened and think because we always run so constantly. This is one of the first times we sat down and I said, “Sue, this is actually working. How the hell did we do this?”

We have 12 musicians on the road and another 10 crew and everyone’s making a living wage. We’re making this thing happen. It’s kind of a beautiful thing. It’s one of the first times I’ve felt like that. That’s always been my goal, my M.O., going back to my solo group. We want to make this thing rise as a group. In other camps –almost every group I’ve played in – there’s so much discontent with the way things go. We’ve always tried to be pretty wide open with how do things, accepting ideas from everywhere.

Going back to what you said about having the right personnel, with 12 people there are 12 more opportunities for dissension.

ST: Yes!

DT: Totally.

Democracy is great but it’s messy.

ST: Yes. We don’t talk about it but it’s understood that at the end of the day Derek is going to be our final decision maker and we all have trusted him to do the right thing. We don’t have to appoint a leader because we all just kind of defer because he’s such a natural at it… and he has such great ideas that everyone usually agrees.

DT: But you’re right; the chemistry and personalities have to be right for the approach to work. And that’s why you can’t make any definitive statements because you don’t know how things are going to shift and change but the personalities right now are in a pretty amazing place right now and it’s the first time since the very beginning where there are no egos that have to be pulled down in line with what we’re trying to do. Everyone now is thinking of it as a group instead of “Well, I need to do this…” or “I need to able to do play that.” Everyone is just doing what makes it go and when the show is good everyone knows it and when the show is not good everyone knows it – whether they played great or not.

It’s a fine line though because when you put together a great band everyone is going to have a big ego.

DT: That’s true. It’s a fine line and that’s what separates great bands from bands that are just mediocre and what separates bullshit supergroups that are just names thrown together but have no chemistry. Some of the greatest bands of all time – like the Coltrane quartet or the Miles bands – have big egos together. But there’s ego and then there’s narcissism. Everyone is going to have an ego but it’s the ability to not always put yourself first that’s important in a band and that’s what I think we’ve been able to accomplish with this group.

And that’s a good reference. After all, if Cannonball Adderley and John Coltrane can subvert themselves to the betterment of the group…

DT:… then who are you? We can get this together!

Back to the studio – has having it in your home paid off in the way you hoped it would, allowing you to have more of a work/family balance?

DT: Yes. Building the studio and putting everything we had to that point into it was probably the best decision we’ve made to date – other than having kids and putting a band together. We’ve made every record there since Already Free there and the amount of time it’s allowed us to have as a band, whether it’s rehearsing or making records is incredible.

ST: I did a couple of tracks on my last solo record there…

DT: We did the Herbie track there, and Revelator, Made Up Mind and Let Me Get By. And we mixed the live record there.

Just having that space and being able to learn that room together as a band is incredible. Almost every rehearsal we’ve ever done has been in that same room, so there’s tremendous continuity when we go to record.

So when you go to record, everyone is in their comfort zone.

ST: Yeah. It doesn’t feel like recording, which can be very intimidating and very time sensitive. There’s a lot more pressure on bands to perform. The time sensitivity really messes with your head. If you just relax and you feel like there’s no time and we can do whatever.. that really is huge. Having a band be comfortable and confident is everything. And everyone knows we’re in it together and having fun.. it is more fun. And now Bobby Tis lives right across the street and rides his bike to work every day… [laughs]

DT: When we’re down there, it’s even more extended family, because my brother [David] keeps the studio rolling when we’re gone and when the band is there he’s cooking out. My parents are there… my brother and his wife and their kids… Bobby Tis and his wife and kids… It’s become more and more of an extended family.

Foto – Kirk West. Kofi, Tim, Derek

Having your family so close has been a huge part of this for you, right? As a father, I completely understand the importance of having family who can help so close by.

DT: We probably would not have been able to put a band together or even think about what we’re doing. There are a lot of people who make this thing go.

ST: There are a lot of people working together who make this possible. I counted 30 recently actually making a living based on this band and that’s an amazing accomplishment.

Does that freak you out at all? It’s a lot of responsibility.

DT: The only time this feels a bit daunting is like this tour, the last your of the year.. I just had major surgery and I was not supposed to be on the road for 4-6 weeks and 12 days after surgery the tour is supposed to start… and I’m having conversations with Blake, who’s saying, “Just tell me. We can cancel the tour”

ST: He’s stubborn

DT: I don’t want to fucking cancel shows and end the year on that note. It changes the whole thing and it’s just a weird way to go out. It’s been such a great year.

I was just re-reading an interview I did with Phil Lesh and Trey Anastasio in 2000 and they were talking about how their organizations got so big that they felt pressured to stay on the road to keep everyone working.

DT With both of those guys, when you add a serious drug addiction to the mix, it gets real hard. Shit, people deal with that all the time in real life. Small business owners and many other people are constantly dealing with pressure. You don’t get a few years into it, it starts working and you scream, “I can’t take it!”

Part of being a grown man is you have responsibilities. One of the things I got from my dad is go to work. His responsibilities were different – getting on a roof and getting up at 5 am no matter how hard you pushed it on the weekend or whatever. You feel like dogshit, whatever, you get your ass up and you go to work. It’s what you do. I feel like, for us there’s responsibility and all of that but really all you have to do to do is what you’ve always done. Yeah, there’s extra phone calls and stress, but you still just got to show up and play the gig.

ST: You and I have literally in our lives maybe cancelled a gig once, Derek. I don’t remember ever cancelling a gig. I have played with strep throat and laryngitis and I can still sing. I remember playing the Boulder Theatre once, which was sold out and I wasn’t going to cancel. I couldn’t even talk but I was not going to cancel. I can’t see Derek canceling a gig. People are like, “ I can’t do it. My throat hurts.” What? Get out there and do the show. These people paid for the tickets. People come from all over. They plan their weekends, or planned it three months out. They bought airline tickets and hotel rooms. You don’t know. You play a place like Red Rocks, people come from all over the world, so you’ve got to be able to play.

DT: I don’t overthink this or put too much emphasis on it, but in the past few months there have been multiple Make A Wish people who’ve come out with their families and it’s the last thing they’re doing. Ever! And it’s like, “Wow. I was having a bad day, but I guess we’ll fucking step it up. Put an extra song in or something.”

ST: When we played in Holland, they had just had the terrorist attacks in Paris and people kept asking if we were still going to play and it was like “Yeah, we’re going to fucking play!” We played in Utrecht Holland and that beautiful girl came out with a Make A Wish type thing. She came with her dad and they had one of our songs tattooed on their arms and the girl is young and beautiful and doesn’t even look sick, but she had a terminal illness and it’s a miracle she’s even here. When you see people like that, there’s no way we’re going to cancel.

DT: It puts it into perspective.

ST: Because we so blessed. If you’re healthy enough to walk out on that stage, you get out there. [laughs]

DT: It’s pressure but it’s small time. My grandfather is 96 and he was walking across France and Germany in 1945. There are people playing in bar bands working a lot harder than us.

ST: And moms working three jobs and trying to feed their kids… come on now.

You know, there is one easy storyline that one could easily take here: Derek Trucks leaves Allman Brothers Band, makes great artistic leap forward. [Everyone laughs] How true is that?

DT: I think it definitely fuels the next thing. I know for me when finally the 45 was coming around, there was so much back and forth and misinformation and people talking out of one side of their face. It was such a mild train wreck at the end. When it was finally coming to the end, I was just like, “Can we make this go out right?” I just wanted to see the shows be strong and the things we talked about five years ago happen. And when it did, it was a huge relief and I was proud of everyone involved and then I really felt that cord being cut. I felt it strongly. It took a minute to dissipate.

I just remember for a few days after those shows being exhausted like I’ve never been. We were on the road and I was like, “Holy shit! I didn’t realize how much that was eating at me.” When that was done, we got home and started writing and making a record and it felt sooo different. I really did feel liberated from the whole thing .

Not for nothing, the last few years with the Allman Brothers, it felt like the dark cloud was hovering, whether it was Farmer passing, or the weird shit that happened on the set of Gregg’s movie, or the illnesses and people getting sick. When Farmer passed, my dad called me and said, “Promise me that you are going to get away.” He was worried! There’s just this thing around them and you feel that. I’m not superstitious but I was like, “It’s time. This is not healthy.” As beautiful as it was, it was just time. Getting away from all of that has been really nice.

I cherish the time I had there and I was honored to be a part of it, but it already feels like a different lifetime. It seems like a long time ago that that Beacon show happened. In a good way! So yeah, I think that fueled it.

Some of it was just the natural evolution of the band by itself and certainly me being able to focus and not be split…

ST: That was the big thing that he kept saying to me: “I just want to focus on one band.” He was spreading himself thin whether it was Clapton or the Allman Brothers. You’re doing a lot of projects and there’s a lot of material there. He recently played Clapton’s 70th birthday… and he and Doyle had to plunge back in…

DT: You want to do them right.

ST: He really puts all of his effort into a project. It’s not like he’s going to just learn tunes and do it. He really puts his heart and soul into it. With the Allman Brothers, there was a lot more psychic energy required than most people probably realize.

DT: Right. People were like, “it’s only a few months a year.” But no one knew how many phone calls it took, how much plotting, how many games of telephone.

ST: No one will ever know the work these guys put in for that group. I can’t even begin to explain it.

DT: [laughing] Me and Warren were like Atlas for a few years. It’s so much deeper than people realized. There was so much psychology involved.

March 18, 2016

Brothers In Arms – Warren and Jimmy as Phil’s Phriends

Beacon 2000. Photo by Danny Clinch

It was a treat to see the Phil Les Quintet last night at the capitol Theater in Port Chester. Phil Lesh, Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring, John Molo, Rob Barraco. Together,t his incarnation of Phil and Friends performed ome of my very favorite shows in 1999-2000 – dare I say better than the Allman Brothers Band at the time. Probably my favorite post 80s Grateful Dead music – and definitely my favorite post- Jerry Garcia. They will be at the Cap again tonight. Enjoy if you’re going.

This story appears in my Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead. The book includes interviews with Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, Robert Hunter, Bill Kreutzmann and others. It dives in-depth into post-Jerry Dead. And it costs less than your latte. Support the home team, brothers and sisters!

Former Allman Brothers guitarists Warren Haynes and Jimmy Herring came together in Phil Lesh and Friends and the Dead.

Though closely associated with one another and with the Allman Brothers Band, Jimmy Herring and Warren Haynes did not play together regularly before joining Phil Lesh and Friends in September, 2000, and they never were concurrent members of the Allman Brothers Band. (They did play one memorable ABB show together, in September, 2000, at the One For Woody benefit/tribute to the late Allman Brothers bassist Allen Woody.)

Herring toured with The Other Ones/The Dead in 2002 and 2003. Haynes joined him in ’04, then toured as the sole guitarist in 2009, the last full-fledged tour of the four surviving members of the Grateful Dead. This story looks to the beginning of the collaborative relationship and captures Haynes still amazed by his entry in the land of the Dead.

The following story has never appeared in this form, though some elements ran in Guitar World in the fall of 2000. The interviews were mostly conducted in October, 2000, while the Phil Lesh Quintet was playing a seven-show run at New York’s Beacon Theatre that played a large role in cementing that group’s reputation.

When Phil Lesh formed Phil and Friends in 1999, he envisioned a rotating cast of musicians offering ever-new interpretations of the Grateful Dead repertoire. In the band’s first year, its guitarists included Little Feat’s Paul Barerre, Hot Tuna’s Jorma Kaukonen, Phish’s Trey Anastasio and jazz great Robben Ford. But then Lesh discovered Jimmy Herring and Warren Haynes, and, voila, the revolving guitar seat came to a virtual standstill.

The Q. Photo by Kirk West

“I heard them doing [John Coltrane’s] ‘Afro Blues’ and became fascinated,” recalls Lesh about the first time he heard Haynes, Herring and Derek Trucks, on Gov’t Mule’s live album With A Little Help From Our Friends. “I knew they were the guys for me. The way they play, they can’t be held down to any one bag or genre. It’s like, you can build a concrete slab over the ground, and if there’s seed under there, it’ll grow and break that slab and reach toward the light. That’s how these guys are.”

Though the two North Carolina natives have often jammed together since meeting in 1994, the gigs with Lesh represented their first opportunities to collaborate on a steady, ongoing basis. The results were predictably combustible from the first, with Haynes’ meaty, blues-based attack and Herring’s lighter, more jazz-inflected approach egging one another on to consistently higher heights.

“We had a great chemistry from the first time we jammed together, and the more we play together, the deeper it grows,” says Haynes. “We share a common thread of influences and approaches, but there are big differences in how we play as well, and that’s the combination you need to generate sparks between two instrumentalists.”

Both guitarists were Allman Brothers alums when they started playing with Lesh, which cast them in an entirely different light.

“It’s is a unique and wonderful experience,” says Haynes. “I thought I was open-minded musically, until I met him. Phil Lesh is, hands-down, more musically open than anyone I’ve ever met. He strips it down to the beginning, when music was meant to convey what you feel, not to be perfected, analyzed or nitpicked. You spend your whole life trying to become proficient on your instrument, then you get back to chasing that child-like wonderment you had before you even knew what you were doing.

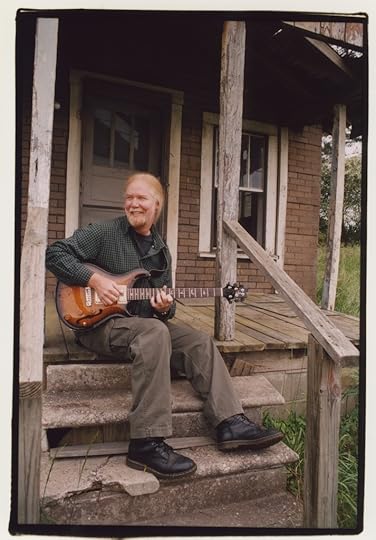

Warren Haynes by Kirk West

“Playing with him has really opened my mind a lot. Just seeing what makes him tick is pretty incredible. There are certain things you can’t figure out as a listener, but once you get on the inside, you understand. I did that to a certain extent with the Allman Brothers. I listened to them since I was nine, and studied that music intensely, but once I played with them, I began to understand things on a more profound level. And that happened to a much greater extent with Phil and the Dead; I really learned a lot from being there, because I didn’t study the Grateful Dead growing up.”

Herring speaks of the experience of playing with Lesh in similarly reverential tones.

“It’s incredibly liberating because there’s no pressure, nothing weighing on you, “says Herring. “He encourages all the musical mischief you can get into, but there’s also a limit where he doesn’t want you drawing attention to the solo. He doesn’t want you falling into the conventional lead and rhythm roles. It makes me play a completely different way. Sometimes, it can seem frustrating, as you may feel like you’re ready to make a musical statement, and you have to pull back.”

The reason the guitarists feel the need to pull back, to stay on their toes and be ready to shift gears at any moment, is Lesh’s love of full-on improvisation, going as far as changing the root note or key signature in the middle of a musical passage. It’s a maneuver designed to make sure everyone is listening intently at all times.

“It took a while for Jimmy and I to adjust because Phil will suddenly change the root and impose a completely different path behind you than the one you were headed down, and that was initially frustrating,” says Haynes. “You have to give up some control, and that’s what he wants. You have to open yourself up in a different way to let that happen. You become less in charge of your own solo.”

Jimmy Herring – By Kirk West

And, adds Herring, that loss of control – the radical idea that a solo is not just an individual musical statement – is precisely Lesh’s goal. “He doesn’t want you too much into your own space,” says Herring. “Phil wants the improvisation, the group interaction. It forces you to be more selfless. You really are able to get to the core of it all.”

Neither Haynes nor Herring had extensive backgrounds in the music of the Grateful Dead, and their deep immersion into the songbook with Lesh gave both guitarists a deeper appreciation and understanding of the music.

“I just realized more than ever how many great songs they have,” says Haynes. “When most people think of the Grateful Dead, they think of the imagery, the fact that their fans are so hardcore or maybe that they improvise a lot and play a different show every night. Not, ‘They’ve written tons of great songs’ but the fact is, very few bands boast such a deep and great catalog of original music. I think it’s amazing how that gets overshadowed. The more I study the material, the more I realize how great a lot of those songs are and how much time went into writing them. Those songs weren’t just thrown up overnight. Some of them have more changes than a jazz song, and Phil wrote a lot of that stuff.”

With the entire Dead catalog at their disposal, as well as a growing body of original material, Lesh prefers to use the tunes as set pieces, launching pads for improvisatory journeys that are equally likely to circle back to their departure point or launch off to parts unknown.

“Phil represents true open mindedness in the sense that there is no mistake you can possibly make,” says Haynes. “It’s music in its rawest form, containing every flaw, every unpolished element. We get up there and for 20 or 30 minutes and just start noodling and jamming and exploring different themes. We sometimes jam for 20 or 30 minutes before we played the first song and it’s amazing to get up and do that and know that your audience will be okay with it.

“That’s what the Grateful Dead did. They created that relationship with their audience that was totally open to the fact and concept of, ‘We’re just jamming and whatever happens, happens.’ We’re searching for magical moments and to get them, there are going to be some less than magical moments, and the audience loves that, which is remarkable and quite liberating.”

March 11, 2016

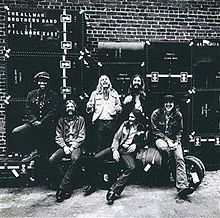

Recording At Fillmore East – A One Way Out excerpt

Today is the 45th anniversary of the start of the three night Allman Brothers Band run at the Fillmore East which produced the greatest live album ever – At Fillmore East. In honor of the historic, holy day, I present to you this excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. If you don’t have the book, please click through and get it! And if you don’t have the album, by all means, get busy!

The following story – Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights Reserved.

**

Though their first two releases had caused barely a ripple in the marketplace, the band was drawing raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with superior musical precision and a deep grounding in the blues. A live album was the obvious solution. To cut the record, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights — March 11, 12 and 13, 1971. They were paid $1250 per show.

Though their first two releases had caused barely a ripple in the marketplace, the band was drawing raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with superior musical precision and a deep grounding in the blues. A live album was the obvious solution. To cut the record, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights — March 11, 12 and 13, 1971. They were paid $1250 per show.

The Allman Brothers Band had made their Fillmore East debut December 26-28, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat and Tears for three night. Promoter Bill Graham loved the band and promised them that he would have them back soon and often, paired with more appropriate acts, and he lived up to this vow.

On January 15-18, 1970, the ABB opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. They were back in New York on February 11 for three nights with the Grateful Dead. These shows were crucial in establishing the band and exposing them to a wider, sympathetic audience on both coasts.

BUTCH TRUCKS: You can’t put in words what those early Fillmore shows meant to us. The Fillmore West helped us get established in San Fran and it was cool – especially those shows with B.B. and Buddy – but the Fillmore East was it for us; the launching pad for everything that happened.

GREGG ALLMAN: We realized that we got a better sound live and that we were a live band. We were not intentionally trying to buck the system, but keeping each song down to 3:14 just didn’t work for us. We were going to do what the hell we were going to do and that was to experiment on and offstage. And we realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off; we need to make a live album.

DICKEY BETTS: There was no question about where to record a concert. New York crowds have always been great, but what made the Fillmore a special place was Bill Graham. He was the best promoter rock has ever had and you could feel his influence in every single little thing at the Fillmore. It was just special. The bands felt it and the crowd felt it and it lit all of us up. The Fillmore was the high-octane gig to play in New York — or anywhere, really.

ALLMAN: That was the place to record and we knew it. It was a great sounding room with a great crowd, but what really made it special was the guy who ran it. Bill Graham called a spade a spade and not necessarily in a loving way. Mr. Graham was a stern man, the most tell-it-like-it-is person I have ever met and at first it was off-putting. But he was the fairest person, too, and after knowing him for while, you realized that this guy, unlike most of the other fuckers out there, was on the straight and narrow.

WILLIE PERKINS: The Fillmores were so professionally run, compared to anything else at the time. And he would gamble on acts, bringing in jazz and blues and the Trinidad/Tripoli String Band – and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered.

TOM DOWD: I got off a plane from Africa, where I had been working on the Soul To Soul movie [capturing a huge r&b, jazz and rock concert held in Ghana], and called Atlantic to let them know I was back and Jerry Wexler said, “Thank God; we’re recording the Allman Brothers live and the truck is already booked,” so I stayed up in New York for a few days longer than I had planned.

It was a good truck, with a 16-track machine and a great, tough-as-nails staff who took care of business. They were all set to go. When I got there, I gave them a couple of suggestions and clued them in as to what expect and how to employ the 16 tracks, because we had two drummers and two lead guitar players, which was unusual, and it took some foresight to properly capture the dynamics.

Dowd was thrilled with what he was hearing until the band unexpectedly brought out sax player Rudolph “Juicy” Carter and another horn player, as well as harmonica player Thom Doucette, a frequent guest who had played on Idlewild South.

Photo by Twiggs Lyndon

DOWD: We were going along beautifully until the fourth or fifth number when one chap looked up and asked, “What do we do with the horns?” I laughed and said, “Don’t be a smart ass,” thinking he was joking, but three horn players had walked on stage. I was just hoping we could isolate them, so we could wipe them and use the songs, but they started playing and the horns were leaking all over everything, rendering the songs unusable.

ALLMAN: Juicy was playing baritone and would basically play along with the bass. Dowd was a perfectionist and the best one I ever met, but we didn’t think it was that big of a deal.

We knew we were recording a lot of nights and probably just figured we’d get it the next night if it didn’t work out. We wanted to give ourselves plenty of times to do it because we didn’t want to go back and overdub anything, because then it wouldn’t have been a real live album.

JAIMOE: Dowd started flipping out when he heard the horns, but that’s something that could have worked. There’s no way that it would have ruined anything that was going on. It wasn’t distracting anyone, and it was so powerful.

BETTS: Dowd was going nuts, but we were just having fun and everyone was enjoying it. We didn’t change our approach because we were recording. We never hired any of those guys. They’d just show up and sit in, and we all dug it.

PERKINS: The horn players would pop up and just sit in for a few songs. Those guys were friends of Jaimoe’s – we just knew them as Tic and Juicy and everyone liked their playing. Nothing was rehearsed with them. They’d just get up and play. Them showing up at those Fillmore gigs was a surprise to me and I didn’t think it was a good idea.

JAIMOE: Tic was a tenor player, Juicy played baritone and soprano – sometimes together, at the same time – and there was an alto player we called Fats, who was not at the Fillmore and didn’t come around as much. We had played together in Percy Sledge’s band and I knew them from Charlotte, NC. Good guys and good musicians.

PERKINS: They often had some heroin with them and were welcomed for that as well.

JAIMOE: I don’t know about that; if they showed up with a little something, it was probably because Duane or someone asked them to do so.

GREGG ALLMAN, undated letter to Twiggs in jail: “Juice plays barry and soprano at once, Tick Tock plays the dogshit out of that tenor (and alto and flute) and Fats plays alto. All we need now is two of the baddest trumpets we could find and commence to kick ass. Duane says if we can cut it payroll-wise, long about summertime we’d like to take them on permanently. Man, those cats are so mellow I can’t believe it. Last week I got a 1956 Wurlitzer and it’s the funkiest thing since poke salad.”

THOM DOUCETTE: The plan was to bring on the horns full time. Duane would have liked to have 16 pieces. Duane had six different projects that he wanted to do and he just thought he could do it all at once on the same bandstand.

DOWD: I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, “The horns have to go!” and he went, “But they’re right on, man.” And I said, “Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.” He asked if the harp could stick around and I said, “Sure,” because I knew it could be contained and wiped out if necessary.

PERKINS: Doucette had played with the band a lot so he was a lot more cohesive with what they were doing. Duane loved those guys, but he would also listen to reason and I don’t think he put up any fight with Dowd.

DOWD: Every night after the show we would just grab some beers and sandwiches and head up to the Atlantic studios to go through the show. That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again. They would craft the setlist based on what we still needed to capture.

BETTS: You have to listen to it being played back to get a sense of whether or not it came together and we loved having that opportunity. We just thought, “Hey this is cool… I didn’t know I did that… That sounds pretty neat.” We were just enjoying ourselves and the opportunity to listen to our performances. We didn’t do a lot of that board tape stuff and we weren’t real hung up on the recording industry anyhow. We just played and if they wanted to record it they could. We were young and headstrong: “We’re gonna play. You do what you want.”

BUNKY ODOM: The band was obviously playing great but you also have to give a lot of credit to Tom Dowd. I’ve known two geniuses in my life: Duane Allman and Tom Dowd. Tom in the studio was like Duane on stage: totally charismatic and he knew how to get the best out of you. They both made everyone they worked with better.

Bill Graham – photo by Sidney Smith

ALLMAN: We sure didn’t set out to be a “jam band” but those long jams just emanated from within the band, because we didn’t want to just play three minutes and be over. And we definitely didn’t want to play anybody else’s songs like we had to do in California, unless it was an old blues song like “Trouble No More” that we would totally refurbish to our tastes. We were going to do our own tunes, which at first meant mine, and because of that there was a lot of instrumentals and long passages between the verses sometimes. Sometimes we had to keep playing to get wound up in search of spontaneity.

BETTS: We just felt like we could play all night and sometimes we did. We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on there. All we did was edit some of the harmonica out, where there was a solo that maybe didn’t fit. It wasn’t doctored up, with guitar solos and singing redone in the studio, as on so many live albums. Everything you hear there is how we played it. We weren’t puzzled about what we were playing. We were a rock band that loved jazz and blues. We really loved the Dead, Santana, the Airplane, Mike Finnigan, and all the blues and jazz greats.

ALLMAN: The Grateful Dead? Well, I never really thought so much of them.

TRUCKS: Jerry and Duane were friends. They really got along well and respected each other, and we all did. The Dead were definitely an influence on us – not huge but definitely in there.

JAIMOE: When I first heard the Grateful Dead, I thought, “What do these cats really want to do?” Then we played a gig with them and after we finished I had nowhere to go so I got the conga drum and sat down on the stage behind the curtains and I just played along with the Dead and someone from their crew saw me and said, “Let him out on stage” and I went out there and got miked up. The minute I started playing with them it made a lot of sense. I had to be inside that music to understand it.

BETTS: I also like the Dead’s philosophy, which is very similar to ours. We sound very different, because we’re from different roots. They’re from a folk music, jug band, and country thing. We’re from a urban blues/jazz bag. We don’t wait for it to happen; we make it happen. But we’ve always had a similar fan base and philosophy — keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.

BOB WEIR: They were definitely more blues-oriented and we were more eclectic, with a jug band background and also come country, and we were also listening to a lot of modern classical music – just grabbing stuff from any and all idioms. But they used the same approach – improvising fairly heavily – and we were both looking to take a scene and run with it. It was clear to me from the first time we played together that we were kindred spirits. We were both just starting to feel our oats. We felt like were becoming a hot band and the Allmans definitely were real hot – they were tight, together and they improvised very well together.

TRUCKS: We were listening to people like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and emulating them and trying to add that level of sophistication to our music – to add jazz and improvisation to blues, rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

DOWD: The Fillmore album captured the band in all their glory. The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove. Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East. Here was a rock ’n’ roll band playing blues in the jazz vernacular. And they tore the place up.

Photo – Sidney Smith

BETTS: There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album: that was a hell of a band and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like. I think it’s one of the greatest musical projects that’s ever been done in any genre. It’s an absolutely honest representation of our band and of the times.

JAIMOE: Fillmore was both a particularly great performance and a typical night. That’s what we did!

ALLMAN: You want to come out and get the audience in the palm of your hand right away: “1-2-3-4, bang! I gotcha!” That’s what you gotta do. You can’t be namby-pamby; you can’t be milquetoast with the audience. There’s a lot of good music out there. It’s like what B.B. King did on Live at the Regal [1965], which is like one big long song, a giant medley. He never stopped. He just slammed it. The second big live record for me was James Brown, Live At the Apollo [1963] and that was the same thing. Those records are what got me into doing everything so meticulously – paying attention to arrangements, the order of the songs. The little things are important.

WALDEN: Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album. Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing was what they were all about, not recording, that a phonograph record was confining to a group like this.

Walden won his fight to release At Fillmore East as a double album “people-priced” for the cost of a single LP.

ALLMAN: I still listen to Fillmore. Those licks that my brother plays are so fresh still and he has such a tone – and Oakley, too. That boy was one of a kind, just like Duane. Just the chance that we would all meet up and form a band is amazing – everything seemed to fall right into place and you can hear it on this record.

WARREN HAYNES: At Fillmore East was a dream come true for a young guitar player — a double record of guitar licks. You could go for a year without leaving your room, just running the needle back over and over saying, “How did they do that?” A lot of us wore multiple copies out, picking up and dropping needles trying to learn the licks.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights Reserved.

February 24, 2016

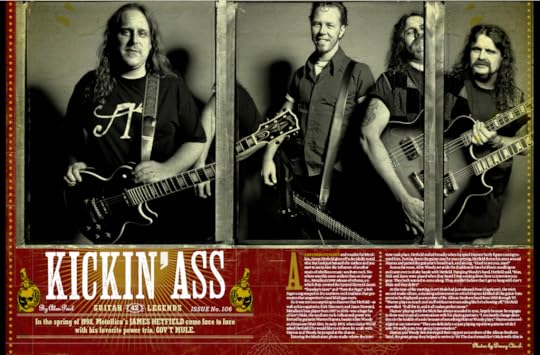

Metallica Meets Gov’t Mule

Photo by Danny Clinch. I love this!

Dose, my favorite Gov’t Mule album, was released 18 years ago this week. In honor, I present this classic Guitar World Dose interview with Warren Haynes, Allen Woody and Metallica’s James Hetfield.

I hatched the idea for this piece on the Gov’t Mule tour bus where I spent two long days… hanging out… with Warren and Woody in Ann Arbor, Michigan when they played the Blind Pig and Rick’s American Cafe on consecutive nights. Looking up the dates just now I realized that the Pig show was on my fifth anniversary – February 27, 1997. How cool is my wife? She came with me to the show, heard how loud it was, kissed me on the cheek and headed home.

They told me on the bus that James Hetfield was a big fan and had recently come to a show in California. We were discussing how to convince my editors at Guitar World to do a bigger story on their second album than we had on their first, and I said, “Maybe we can get James involved.” I had some history of such things with James – he interviewed Tony Iommi for Guitar World in 1992, a story I co-wrote with Brad Tolinski and which you can see here.

Within a few days, I had written a letter to Metallica’s publicist, Hetfield quickly agreed, and the wheels were set in motion. The following December, with Dose due to be released, what follows went down in New York City. Photographer Danny Clinch was hired, he rented a studio in Soho, where we did both the photo shoot and the interviews. This was the beginning of a long, fruitful relationshp between Danny and Metallica. (His relationship with Mule also began with Guitar World – with our 1994 Warren/Dickey Allman Brothers cover.)

This interview with James Hetfield and Gov’t Mule was conducted in December, 1997 and became part of a Guitar World cover story. It was reprinted in the Guitar Legends Southern Rock issue, which is available in the GW Store, and which also included my history of the genre and my piece on the Allman Brothers band’s At Fillmore East, as well as a fantastic Lynyrd Skynyrd story. I’m happy to launch this into the digital world. Enjoy. And, as always… Woody!

The spread in the reprint.

Kickin’ Asses

Metallica’s James Hetfield comes face to face with his favorite band, Gov’t Mule.

James Hetfield enters the Manhattan photo studio, guitar case in hand, and strides across the huge, empty room. His face cracks open into a wide grin as he spies Warren Haynes coming towards him. Putting down the guitar, Hetfield throws his arms around Haynes and pats the guitarist’s broad back. “Good to see you, man.”

Across the room, Allen Woody sets aside the doubleneck bass he’s been noodling on and comes over to shake hands with Hetfield. Pumping Woody’s hand, Hetfield says, “It’s great to meet you,” with an enthusiasm you might not expect from someone who’s sold over 35-million albums. “Man, Kirk and Jason were pissed when they heard I was coming down here to interview you guys. They both wanted to come along. They couldn’t believe that I got to hang with Gov’t Mule and they didn’t.”

Haynes and Woody, the objects of all this Metalli-fection, snicker and share a grin. Hetfield’s genuine excitement proves to them what they’ve believed since the moment they formed Gov’t Mule four years ago: they’ve got something special happening. For this is a band heavy enough to be Hetfield’s favorite; grungy, gritty and bluesy enough to earn the praises of ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons; and swirly enough to speak loud and clear to the Phishheads who flock to their shows to twirl the night away. It’s all displayed on Dose (Capricorn), the trio’s second studio album, and a stunning instrumental achievement, on which Haynes fulfills all the guitar hero promise he displayed as a member of the Allman Brothers Band from 1989-97.

“Warren plays so much, and such cool stuff without ever sounding like he’s showing off,” marvels Hetfield. “It all fits in, and it all makes perfect sense.” One reason that Haynes’s playing always sounds so in sync is that as much as he is the featured performer, the Mule distinctly does not consist of a rhythm section playing a locked-in groove while a soloist goes off all night. Rather, they engage in endless three-way conversations, with Woody and drummer Matt Abts often speaking almost as much as Haynes.

“I constantly change directions in the middle of a solo because of something Matt or Woody plays,” Haynes acknowledges. “They are definitely not just playing repetitive patterns while I solo. It’s really pure, true group improvisation.”

Haynes and Woody first developed their rapport as members of the Allman Brothers, the great group they helped to revive in ‘89. After eight years, the duo left the Allmans last spring to concentrate on the Mule, which was born in 1993, when Haynes, Woody and Abts first played together at a Los Angeles jam session. A year later, they played their first formal show, going on to do about 80 gigs in-between Allman Brothers tours before releasing their self-titled 1995 debut on Relativity Records.

Today, some 300 gigs later, the first album sounds like but a demo for Dose, the album on which the group’s vision of a high-powered jam band playing progressive rock with jazz skill and subtly and heavy metal power comes to full fruition. The Mule’s sound has deepened, expanding in almost every direction–becoming both bluesier and heavier, more expansive and tighter. From the proto-metal minor key riff of “Game Face” to the Miles Davis tribute “Birth of the Mule” and from the psychedelic freakout coda tagged onto the Beatles’ “She Said, She Said,” to the acoustic, Zeppelin-esque “Raven Black Night,” Dose is a powerhouse, one of the boldest, most adventurous guitar records of recent years.

“There’s a lot of range in their music,” observes Hetfield. “But it always seems appropriate and it always sounds fuckin’ cool.” So it is that the Metallica frontman leaped at Guitar World’s offer to interview the band, showing up filled with enthusiasm, loaded with questions and anxious to rap.

The original cover

James, how did you first hear the Mule?

JAMES HETFIELD: We had an accountant named Kenny Silva on the road with us, who had been working with the Allman Brothers. He gave me a tape and said, “I think you’ll like this. It’s serious guitar music with a heavy Southern Rock vibe.” I threw it in, and I just fell in love with it. Kirk got wind of it around the same time and also fell in love. It just hit us right away.

What attracted you so strongly?

HETFIELD: I’m not generally a big solo guy, because I’m not into showing off that way. But this stuff fit exactly with the music, and it just sounded like stuff I’d want to hear. In fact, it sounded like stuff I’d want to play. If I was playing lead, that is how I’d like to play–but I can’t. That thought struck me right away: This is how I’d like to be able to play leads. So in a way, I feel like Warren’s playing is my expression of a solo voice. And then you’ve got a kick-ass bass player playing chords–which is incredibly cool but is not allowed in our band. [laughs] We’re like, “Jason, keep one finger right here and play.”

So you and Kirk enjoy Gov’t Mule together, but conspire to make sure Jason never hears it?

HETFIELD: [laughs] Exactly.

ALLEN WOODY: That’s a good idea, James. I can give a guy a lot of bad habits if you’re not careful. I tend to think I’m Leslie West with a bass.

Warren, what did you guys think when you first heard that the guys in Metallica were fans?

HETFIELD: [laughs] He thought, “Metalli-who?”

WARREN HAYNES: No, no. Believe me, I knew who you were. I thought it was really cool. I was happy to hear it. Any time somebody is into your band that’s a good thing. And if they’re in a really cool, really popular band, that’s a better thing. I had heard their stuff over the years and was actually thinking of going to check out one of their Lollapalooza shows, so I was relieved when I heard that they dug us because I figured that would make it a lot less awkward than going backstage and having someone say, “Here’s some guy from some band who wants to drink your beer.” [laughs] Instead, I met them and they were super nice, and very flattering, which was great. I know where Metallica is coming from, and I don’t think them liking us is as strange as it may seem to some people. First of all, our stuff is a little heavier than most people probably think. I don’t classify it as hard rock, but everything we do definitely has a hard edge, and I think there are a lot of Metallica fans who would be Gov’t Mule fans if they checked us out, though they don’t know it. We’re definitely not just for Allman Brothers fans.

James, do you think most Metallica fans would like the Mule?

HETFIELD: I think so. Without waving the guitar flag too high, there are a lot of guitar fans who like Metallica because there’s a lot of crunching going on and a lot of guitars in your face. And I think the people who are attracted to Metallica for that reason will definitely dig Gov’t Mule, because you talk about guitar in your face, this is it, man.

James, you have told me before that you really dig Lynyrd Skynyrd, but never really got into the Allmans.

HETFIELD: Yeah, that’s true. Actually, I went back and listened to a lot of the Allmans catalog to get ready for this, and I thought that a lot of it was very stiff. It is very jamming on the surface, but there are many things which can’t really let go because you’ve got two guitarists and two drummers and a keyboardist. It will sort of go off on a jam for a while, but it doesn’t just go crazy like some of the stuff in the Mule, which I love. Plus, of course, the Mule definitely has a rockier edge, everyone’s covering a lot more ground rather than just playing their parts, and it is a lot more loose. Being a three-piece, it has to be.

HAYNES: Right. Because I’m the only chord, it’s easy to just take off. I think the less people you have in a band, the easier it is to take off for uncharted territory. Because if you have three chordal instruments, the others have to either lay out or listen really, really closely to what one guy’s doing.

Photo – Danny Clinch

WOODY: Obviously, it’s a lot more dangerous to turn seven guys loose than it is three. With the Allman Brothers, you could get into trouble real fast if you got outside of the parameters, because of the two drummers and seven guys bubbling under everything. But with three guys, who’s to say it’s a mistake? If you can react, go for it. There’s some really good moments on our records which were, in fact, mistakes.

HETFIELD: Just play ’em twice, and they won’t be mistakes. That’s cool. There is definitely some crazy stuff going on in the new album. For instance, on “Thorazine Shuffle” your drummer just goes fucking nuts at the end. Who’s holding the beat?

WOODY: We are.

HETFIELD: Wow. That must have been pretty damn hard to play along with.

HAYNES: Yeah. Woody and I are laying the beat and Matt’s soloing across it. I think it’s very cool for the drummer to be set free from having to worry about holding down the beat every once in a while, though it’s a little constricting to us. It was actually Woody’s idea to give Matt a drum solo across that weird time signature. We were trying to figure out how to end the song and Woody said, “I think Matt ought to turn the snares off like Bill Bruford and play a drum solo across the outro and we’ll keep the riff going.” We tried it, and it turned out to be a cool thing. I think that’s just one example of Matt playing incredibly cool stuff on this album. He tuned his kit higher this time than on the first album, where he had more of a bottom tuning. As soon as he did that, his drums rose above the thickness of the guitar and bass and really altered our sound a lot.

The reprint cover

WOODY: When we recorded “Thorazine Shuffle,” we were all within five feet of each other, with our amps off in some other room. That’s something we’ve always done, because you really have to if you want it to be loose and flow. On your last few albums it sounds like you guys are heading in that direction, so I was wondering if you’ve ever recorded that way?

HETFIELD: We’re trying to do that sort of thing, but five feet is a little close for us. [laughs] We don’t want to be within choking distance. We do the drum tracks first and we’re all there for that, which is new for us. But when it comes time to do overdubs, it’s like, “Get the fuck out of here. I’m letting loose.” It works better that way because, for instance, if I’m there when Kirk is doing his rhythm stuff, he’s already nervous doing stuff he hasn’t done before, so the last thing he needs is me glaring over his shoulder. It’s really better if I’m not there. Then when I hear it, it’s like, “Grrrr…I guess I can live with that.” But it’s cool, it’s pure, it’s him. You guys, on the other hand, do almost everything live–and point out whatever isn’t in the notes, which is pretty awesome.

HAYNES: Yeah, we like to point out where the overdubs are. Since I’m the only guitarist, the rhythm guitar drops out during solos. We usually don’t change that, but when you do hear a second guitar, we overdubbed the rhythm part, because all the solos are live.

HETFIELD: Wow! That’s awesome. So you don’t overdub the solos–which is backwards off how most people approach it. Your overdubs are just for filling in, so it’s really not cheating from the live approach.

HAYNES: Right. On the new album the only solo we overdubbed was “Larger Than Life,” because that’s a new song and we’d never played it live so I put the rhythm down and went back to the solo. But our main goal is to get the jamming feel on tape, which is why I play the solos live and overdub the rhythm as necessary. It’s a very old school way of doing things, and something we have to do in order to get the three-piece vibe we want. If I didn’t play a solo live, Allen and Matt would be guessing what to play, because we really do play off each other.

Do you carry that live approach all the way to effects?

HAYNES: Yeah. I ‘m stepping on the pedals as I solo. The only time I remember running a signal back through an effect was the wah wah on “Blind Man in the Dark.” I didn’t play it live because I’m just not a good wah wah player. I’ve never been really into it. I heard it for that song, but if I tried to play it live, it probably would have taken us 20 takes to get it right–and we never do 20 takes.

Though you did seem to utilize the studio more this time.

HAYNES: Yeah, we really wanted to take advantage of it. For instance, on “Blind Man,” we panned the bass off to the right, with the dirty vocal up the middle, the guitars off to the left and the drums are stereo. In pre-production, we talked about wanting to find one song where we could pan all the guitar to one side and all the bass to the other side like they used to do. It’s a really old school mix.

WOODY: If you listen to some old Cream or Beatles records, you have the bass and vocals on one side, and the guitars and drums on the other side.

HETFIELD: That’s sort of what we tried to do on our last couple of records–just have the guitars completely split. Kirk’s in the right speaker and I’m in the left speaker. Just make it real simple if anyone wants to know who’s playing what.

HAYNES: That’s a really cool thing to do in a two-guitar format. We did that in the Allman Brothers a bit and I wish we had done it more because the old Allman Brothers were always Dickey on one side and Duane on the other. When you have two guitar players playing all the time, it’s very cool, but when you have one guitar coming in and out, as we do now, you have to pick your spot.

It really is clear listening to Dose that there’s only one guitar. James, I think you’ve tended to like duel-guitar bands. Is new for you to be so into a one-guitar setup?

HETFIELD: Not totally. I’ve always liked Rush, but it’s true that in the early days, metal generally meant two guitars. In bands like the Scorpions, UFO and Judas Priest, you had the rhythm guy, and then the guy who did the solos. Those was their duties and it was clear cut, so that’s how we always did it, too. But as time went on, I started thinking, “Why does it have to be so strict?” I love playing melodies, so I started saying, “Okay, Kirk, you play some rhythm and I’ll just fuck around here.” And it’s been a lot of fun.

HAYNES: More slow, melodic guitar parts are popping up in your stuff. Is that you?

HETFIELD: Yeah. I love playing the melodic stuff. I love adding textures and colors, and we’ve mixed it all up now, with Kirk doing more rhythms and me doing more leads.

HAYNES: I love the way you guys used pedal steel on the new record. Was that you?

HETFIELD: Yeah. I can’t really play the thing but if I figure the part out, I can make it sound good. Those things are hard, man. There’s just so much going on, with the foot pedals and everything. It’s like playing drums and guitar at the same time, but if you can figure something out it sounds awesome. I wanted to do that because we were accused of going country on Load: “Well, there’s pedal steel on it and blah blah blah…”

WOODY: They ever hear of Led Zeppelin?

HETFIELD: Exactly! That’s why I said, “Fuck ‘em. I’ll really play country on this one.” I used both the pedal steel and a B-Bender Tele. I like the way you guys used some different instruments on Dose, too, like the mandolin, and more acoustics. It adds a lot of cool textures. Again, very Zep-like.

HAYNES: Thanks. To be honest, I was worried that you wouldn’t like that stuff as much, and there is quite a bit of it on this album. All the mandolin stuff is Woody. He played a dulcimer on “Raven Black Night,” an electric mandolin on “I Shall Return” and on “John The Revelator,” he played a prima, which is a Serbian instrument that’s sort of a cross between a mandolin and a banjo. It looks like a mandolin but plucks like a banjo.

Warren, the thing that always trips me out at your shows is seeing all these hippie kids dancing away to a Black Sabbath groove. It amazes me that they respond to music much heavier than what they are used to.

HAYNES: I think that kids today are much more open-minded. It’s okay to mix genres, whereas in the old days you couldn’t do that. I did, and Woody did–musicians did–but the general public tended to like one style of music, and it was like, “I’m a rocker, I don’t listen to country music,” or “I‘m a blues guy and rock sucks,” or “I’m into jazz and Eddie Van Halen sucks.”

WOODY: It was like a class war.

HETFIELD: Exactly. You were either in or out, and it was hard to go half way. Like, I liked metal and punk, so I wasn’t accepted by either group.

HAYNES: But it’s not like that anymore. Kids listen to a lot of different stuff, and pick and choose what they like, and part of what makes Gov’t Mule work is we run the whole gamut from really heavy to really soft. In a trio, you have to have the dynamics. There are really soft and delicate moments and really loud and obtrusive moments, and everything in between. Because dynamics is our fourth member.

HETFIELD: Ooooh. Deep. [laughs]

WOODY: He’s got lots of little sayings like that written down on scraps of paper in his pockets.

HAYNES: Yeah, I’ve got lots of little crib notes. [laughs] The good thing about having a bigger band is all the different sounds and textures and layers you can do. In a trio, you don’t have that option. That’s why I use more effects than I would in a larger band and it’s why we really exaggerate the dynamics.

HETFIELD: Yeah. In a lot of your songs, you’ll go from an intensely loud and heavy chorus or bridge to a very mellow verse and it’s like, “Wait a minute, how did they get here? I didn’t notice how they arrived here!” It seems so natural and that’s the thing that impresses me so much about your song structures. It always seems really hard for us to pull that off; the switches tend to seem too obtrusive and obvious.

HAYNES: Thanks. The chemistry between the three of us has been great from the get-go, which is really crucial to pulling that off, but it’s also something we’ve discussed at depth: ways to vary things and react to each other and adapt to make a full, rich sound with just the three of us. If Woody and Matt played the way they do in a larger band, we would sound empty. The beauty is they just beat and bang to death, but it’s all perfectly tasteful and fitting.

WOODY: I have a sneaking suspicion, however, that Matt and I would play exactly like this in a larger band.

HETFIELD: [laughs] Yeah, man, but now it’s okay. Now you’re let loose! You’re free of the rhythm section cage. That must be awesome.

WOODY: Yeah, it’s a real treat, especially coming from where I was. I played with Warren for eight years in the Allman Brothers and loved it, and then the first time I played with Matt, I thought, “This is it. This is the guy I’m supposed to play with.” It’s a rare opportunity all the way around: to be able to play in a three-piece, to be able to play busy and to be able to play with people who really know what they’re doing and dig what you’re doing. And it’s also been very exciting to see so much progress. If you listen to the first record and Dose back to back, I think the growth is tremendous.

HETFIELD: “Game Face” has a killer, extra-heavy, minor riff. Its heaviness really stood out to me. It’s even something that we would do. Actually, it reminds me of early UFO.

HAYNES: Hmmm. They were a good band, but I don’t think I’ve been influenced by them at all. I was, however, a big Deep Purple and Ritchie Blackmore fan and a lot of my attraction to the harmonic minor carries over from those days. I don’t remember exactly where that riff came from, but it’s definitely pretty dark. I love minor keys, and it’s a lot easier to be heavier in them than in a major.

HETFIELD: Oh yes. We know all about that. Major is too happy for us.

HAYNES: Although I’ve noticed that you guys have started trying some songs with major thirds, which is cool. It’s good to go somewhere different once in a while.

HETFIELD: Yeah, but for us, that means the lyrics have to be extra heavy to balance it out. [laughs] Warren, your solos always seem so well formed. Are they written out?

HAYNES: No. All the solos are pretty much improvised. Most of the time, I would play it completely differently each time, then we’d decide which one we liked. Once we pick one and record it, I usually learn it and try to base my performances around it, or else the song will just seem wrong to people.

HETFIELD: Lately, Kirk has been trying to come up with solos more like that. He’ll noodle along while we record basic tracks, trying out different ideas, and by the time he’s ready to record, he has a pretty good idea of what will work. Jason does a similar thing, trying out different basses, so he ends up with all these awesome sounds, and they always fit right into the song. It’s sort of a new thing for us, because it was always just Lars and I slugging it out during basic tracks: “That sucks! Do it over.” Back and forth, back and forth. I was the only one stuck in hell forever. Now everyone goes with me, so it’s less of a hell. It kind of intimidates Lars into doing his homework more and playing a little better. That process has made the studio a lot more fun for us. How many takes do you guys do to get these live performances?

HAYNES: It depends, but usually we use early the first two or three takes.

HETFIELD: Wow.

HAYNES: Although there are always the problem children that take 15 takes.

WOODY: But we will not play anything 15 times in a row. We’ll just move on and come back. Our producer is pretty good at not letting us bang our heads against the wall.

HAYNES: He sees the magic dripping out after three or four takes, and comes up with some excuse for us to break.

HETFIELD: Warren, do you feel the need to perfect your parts or just see what comes about through jamming?

HAYNES: It’s more about improv. I don’t make myself sit down with a tape recorder and write riffs as much as I should. Instead, I wait for cool moments to happen when we’re jamming or to get lyrically inspired and suddenly think, “I need a riff for this song.” Part of it is laziness and part is just my love for improv. I’m more interested in where the jamming will lead us than in seeing what I can figure out in my living room.