Alan Paul's Blog, page 23

January 26, 2016

Derek Trucks 2006 interview: “It’s really nice to get away from the kid thing.”

In honor of the release of the Tedeschi Trucks Band’s Let Me Get By, which I believe not only represents a quantum leap in the band’s development but is the great Derek Trucks studio statement we’ve all been waiting for, I present this 2006 Guitar World interview. It has never been published, as it got turned into a shorter story using some of the quotes. I did a much longer story when I caught up with Derek and Doyle Bramhall 2 in Shanghai with Clapton. (I’ll post that down the line.)

It was a very exciting time for Derek. The Derek Trucks Band’s Songlines was about to come out. He had just recorded The Road to Escondido with JJ Cale and Eric Clapton and was about to set out on a world tour with EC and he was still riding high with the Allman Brothers. Enjoy.

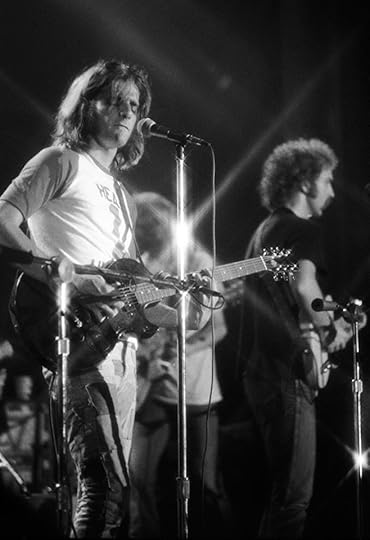

Foto by Kirk West. 7/12/04 Kansas City, MO

The whole music world is about to find out what Allman Brothers fans and jam band aficionados have known for years: Derek Trucks is a strikingly original musician redefining the slide guitar. Derek Trucks. After releasing Songlines, his own band’s sixth and best album, Trucks has joined Eric Clapton’s band for a year-long world tour, while an album they recorded together will be released this fall. Trucks also remains a member of the Allman Brothers Band, who have restructured their touring schedule to keep him on board; they will hit the road during Clapton’s down time.

Trucks’ rising profile is no surprise to anyone who has been watching his very public development. He has been touring since he was 11, released his first album when he was 17 and joined the Allman Brothers when he was 19. Now 26, Trucks is an endlessly inspired and crafty guitarist, equally capable of playing tasty, minimalist fills or extended improvised solos that never fail to surprise. Always tuned to open E and never using a pick, Trucks has established a wholly individual sound, incorporating Indian classical music, “sacred steel” gospel and jazz into a more classic and rock and blues base.

Trucks was first featured in the pages of Guitar World 15 years ago as a pre-teen Florida phenom with a freaky ability to mimic slide great Duane Allman. He has come so far because, unlike many child prodigies, his own virtuosity never blinded him to the larger picture – seeking to create great music. Instead, he has constantly pushed himself further, exploring the very boundaries of slide guitar.

“I started playing slide when I was 9 years old,” says Trucks. “I was trying to sound like Duane and [bluesman] Elmore James and it was also easier on my little hands – it didn’t hurt as much. Eventually, as I got deeper into it, I felt like slide guitar, by being fretless, had less limitations and allowed me to get more of vocal, nuanced sound, which was my goal.

“And the other thing about slide is I felt it was more wide open and unexplored. Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan have inspired thousands of clones, but slide guitar’s potential is still pretty untapped.”

One reason for the lack of exploration of rock slide guitar is the fact that Allman, its greatest practitioner, died when he was 24, and only just beginning his sonic explorations. In many ways, Trucks has picked up where he left off; mastering Allman’s music has been a starting point for Trucks, rather than a destination.

How did you come to be a member of Eric Clapton’s band?

TRUCKS: Out of the blue, I got a call from Doyle Bramhall saying Eric wanted me to come record with him. I was shocked and thrilled and flew out to L.A. having heard no music. The sessions were very laid back and all the tunes went down really smoothly. Being in the studio with people you don’t know can be really tense and frustrating, but this was natural and comfortable. In addition to meeting Eric, I also met JJ Cale who produced the session and Billy Preston, who played keys and that was also really exciting. It was one of those things where even as it is happening, you know it’s something you’ll remember forever and will end up being a career highlight.

It has been said that Eric is recreating Derek and the Dominos with you in the Duane role.

I know that is the perception of some people the outside but that’s not what’s really going on. I have not heard Eric or anyone from the inside say that. I don’t really want to be compared with Duane again, but it is inevitable that will come up since I am jumping from the Allman Brothers to Eric Clapton. I just want the chance to do this on my own terms and the fact is no matter what anyone says or where you’ve come from, you have to make it happen. Once you’re in the studio or standing up on stage, no one cares about anything except whether or not you can deliver the goods.

What is your role in Clapton’s band? How much will you be playing assigned parts versus ripping improvised solos?

I have no idea. It’s actually really exciting to go into such an unsure situation and to think about playing a gig where 95 percent of the audience has no idea who I am. It’s a real luxury to play with a great band without expectations that you should be carrying the show.

You are going to have a very busy year.

To say the least! [laughs] Eric basically tours one month then takes a month off and during those times I will go straight into an Allman Brothers tour. And my guys [the Derek Trucks Band] will be opening a bunch of the ABB shows. With Songlines coming out and the band reaching a point I feel very good about, I have to do whatever it takes to keep it going and that means working more than usual. It will be an exhausting year but it’s a really exciting time for me. Opportunities like this Clapton tour don’t appear too often and you have to seize them when they do. You can work out the details later.

On Songlines, you again play everything from Delta blues to Indian classical music, but it somehow feels more unified than it has on your previous albums.

Thanks. That is the goal. In the past, people have complained that we sounded like three or four different bands on one record and I thought they had a point. That is less and less the case, as we solidify a band sound regardless of what we are playing. That has been for the last two or three years and the recording felt like the culmination of that process. This is our first record that I can enjoy listening to instead of only hearing a million things I wished I could redo.

Though still very raw by contemporary standards, Songlines is also more produced and polished than your previous efforts, utilizing a variety of tones and more multi-tracking.

We really wanted to utilize the studio, not just capture a great live performance. We wanted to air things out and do something a little different. We have always taken pride in capturing songs in one or two takes but we were much more open minded this time. We were striving to make a great album, which is kind of a lost art, especially in this little [jam bands] scene we find ourselves in.

We have approached previous albums by writing out a set list and seeing if we can capture a great performance. But now we have recorded an actual live album [2004’s Live At The Georgia Theatre] and it was time to try something else.

At 26, you have already been a touring musician for over 15 years. Has the perception of you has changed now that no one can say, “He’s really good for a kid”?

It’s really nice to get away from the kid thing. The novelty tag helped us at the start — it probably kept us on the road by keeping the interest up –so I don’t want to say anything too negative about it. But it is definitely nice to move beyond that and have the music taken at face value.

January 20, 2016

Remembering Glenn Frey

The following piece is written by Bob Lefsetz. I did not write it!

Bob writes a great newsletter to which I have subscribed and suggest you do as well. Check it out here, along with his archives.

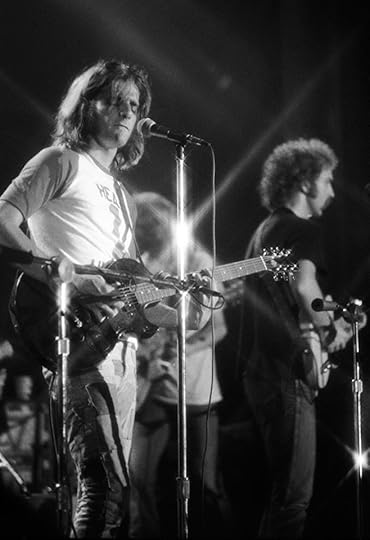

Photo by Kirk West. Chicago, 1974

Glenn Frey – by Bob Lefsetz

He lived the American Dream.

You know, wherein your wits, smarts and pluck, never mind the gleam in your eye, take you from nothing to everything, in this case not only accumulating riches, but influencing the culture.

And there were those who hated him for it.

They lionize Steve Jobs. And Mark Zuckerberg. The techies that changed the world.

But they hate Glenn Frey and his flock of Eagles for being so damn successful, for worming their way into women’s hearts. And let me be clear, it’s always guys complaining about the Eagles, girls loved them. Because females are not into pecking order, not married to the past, they can embrace that which truly satisfies, casting preconceptions aside.

And the preconception was that you had to be English, with bad teeth and little education, or American and challenging cultural commandments, or else you didn’t matter. Gram Parsons might be the father of country rock, but he could never compose a song that penetrated the public consciousness to the point that radio stations could not stop playing it and none of us could ever forget it.

Like “Take It Easy.”

That acoustic guitar came out of the speaker in the dashboard and in the summer of ’72 all of America felt good. It was a different country back then, divided for sure, but we still believed we were winners, that if we put our minds to it we would come out on top. We were never gonna be here again, so we opened up and took across this great country of ours, lived life to the fullest, with the radio blasting all the while.

And despite the hit single, it was the era of album rock. So upon hearing the mellifluous tune you went out and purchased the Asylum LP and…you played it over and over again. Thirty seven minutes long, the debut had no clunkers, it begged to be heard. Take that modern music.

But the follow-up was a commercial dud. “Desperado” got no traction, not the LP nor the title track. The press had primed us for it, back when “Rolling Stone” was the bible of a generation, but without a hit single “Desperado” faded in an era where music dominated and we couldn’t afford to buy all we wanted.

And then “Best Of My Love” went to number one. Credit a deejay, who rejected the two authorized singles in favor of it. Suddenly, the Eagles owned the airwaves.

Of course Glenn would tell us they were called “Eagles,” and was unhappy that everyone appended the “the,” but he and the rest of the band were thrilled with the attention and the dough. They were rock stars. Raising funds for political candidates and partaking of the goodies that accompany the success. It’s one thing to be rich and famous, it’s another thing for it to be based on your creativity, your art. These are the people we exalt. The Eagles were at the pinnacle, especially with the following year’s “One Of These Nights,” they were a stadium act, the biggest band in the land.

And the hatred ensued.

But unlike today’s wimpy musicians, the Eagles barked back, owned their talent and success. Funny how we give Kanye a pass, despite not having made memorable music for years, but we excoriate the SoCal band that was bigger than the rest.

But no one was prepared for “Hotel California.” When you dropped the needle on the record you heard a sound foreign to the catalog. The guitars screamed and if they were big before, the Eagles were now America’s band.

It was “Life In The Fast Lane.” A term every baby boomer knows and said for decades, when they snorted coke, when they did what they should not do. The Eagles blasted open the highway and then we drove right down it.

And now Glenn Frey is gone.

I felt he would make it. It had been weeks, he’d made it through the dreaded holiday period, but then he passed.

And America was shocked.

The press didn’t know how to react. Because they had to be cool, they couldn’t attest to what data tells us, that the Eagles are the biggest American band in history.

Their “Greatest Hits” jockeys with “Thriller” for number one. And unlike so many albums of the past, it still sells. It’s not in the rearview mirror. The strange thing about the Eagles is they never went away. They inspired the country pickers and they still own the bars and the radio. That’s what you get what you’re that damn good.

And there’s no one better.

I know, I know, you’ll cite artists breaking convention, your favorite player, but the truth is writing catchy songs with meaning and singing them with exquisite harmonies is damn hard to do, it’s just that the Eagles made it look easy. Hell, half of Nashville walks in their footsteps, but no one’s done it nearly as well, and so many of those stars don’t even write their own material.

But the Eagles did. With help from J.D., Jackson and Jack Tempchin. But they weren’t guns for hire, but members of the club, a roaming group of musicians who owned the hearts and minds of America throughout the seventies, and didn’t let go thereafter.

So you’re either sad or you’re not.

But if you are…

67 is way too young. And although Don Henley had more solo success, it was Glenn’s band. He started it, he guided it. And every group needs a driving force.

So it’s the end of an era. And it’s a great loss. You’ll never be able to see the Eagles again. But if you did…

The sun would be setting behind the stage.

And at the appointed time, with no wait, they would take the stage and Glenn would say…

They were the Eagles from Southern California.

And the guitars would strum, the bass would pluck, the drums would pound and as the sound washed over you you’d become your best self.

America runs on California. That’s where the innovation begins, where you go to test limits, where there’s no ceiling on either creativity or success.

And people hate California the same way they hate the Eagles.

But what they really want to do is get on board.

And we all got on board with the Eagles. Even those who say they do not care. They only wish they were standing on that corner in Winslow, Arizona, with a girl checking them out.

In a flatbed Ford, made in Detroit. Where Glenn Frey emanated from.

But he remembered his roots.

And built upon them.

Want to be successful?

Need it. Study. Make friends. Seize opportunities.

And take no shit as you ascend into the stratosphere.

That’s what Glenn Frey did.

You cannot make a big enough deal about his death. Because what once was is now gone. Doesn’t mean we can’t create something new, but so far we haven’t minted stars as big as those from the seventies, never mind create music as memorable.

Glenn Frey was here for the long run. He got stuck in the Hotel California and he wasn’t eager to get out. But we all meet our demise, his as a result of side effects from arthritis drugs, he just didn’t want the pain.

None of us want the pain. We’re self-medicating every day.

But years ago the music was enough. We just turned on the stereo and a smile crossed our face.

Glenn Frey took us there.

Now we don’t know where to go.

Written by Bob Lefsetz. Click for more from him.

January 18, 2016

RIP Glenn Frey – isolated vocals, “Take It Easy,” “Hotel California”

Photo – Kirk West. Aragon Ballroom. Chicago, 1974.

Glenn Frey (November 6, 1948 – January 18, 2016)

Well,this has been a hard week. David Bowie, now Glenn Frey. Glenn and the Eagles were not without their controversies and they sure had plenty of critics, but the music was the soundtrack for so much for so many of us.

If you want to understand the band, where they came from, their place in history and what tore them apart and brought them back together, this documentary is a must. It’s pretty insightful about rock, the 70s, and long-term business relationships in general, actually.

One of the things that struck me in History of the Eagles is Glenn Frey saying how much he was influenced by jackson Browne, who taught him how to approach songwriting like a pro. Any one who has read One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band knows that Gregg Allman said something very similar. jackson is sure an interesting cat. Think of the songs he inspired: “Take It Easy” (which he co-wrote), “Midnight Rider,” “Peaceful Easy Feeling,” “Whiping Post”… and on and on.

I chose a couple of cool video and music tracks below which I believe highlight the craft of the Eagles music: isolated vocal tracks for “Take It Easy” (demo) and “Hotel California.”

The Eagles, “Take It Easy” – vocals only This is a demo. Not sure who all is on the harmonies, but it’s definitely bassist Randy Meisner and Frey and, I suppose, Don Henley. And Bernie Leadon?

The Eagles, “Hotel California” – vocals only – starts at 0:54, when vocals come in… This is, of course, Don Henley on lead vocals. But listen to the harmonies.

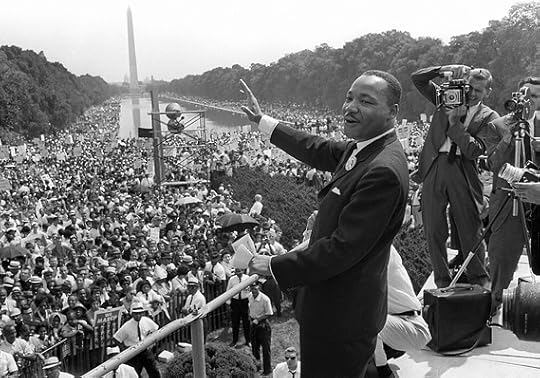

Honoring Dr. King with Gregg Allman’s haunting “God Rest His Soul”

I Have A Dream Speech – Getty

Please pause to remember Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) today.

Today is the 30th time that we as a nation have taken a day off to officially celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. anyone my age or older remembers what a struggle it was to get that law passed – eventually signed by President Reagan, who had opposed it.

Let us take a moment to really honor him. If you want to perform some type of service today, click here – quickly.

Photo – Derek McCabe

Dr. King was, of course, murdered in Memphis. I think it’s important to remember that he was there marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m also sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so.

Gregg Allman wrote the song “God Rest His Soul” for Dr. King but it was never on one of his studio releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… Anyhow, I think it’s a great tribute to a great man. The version featured below was on One More Try, a great anthology I worked on and wrote the liner notes for and which is sadly out of print.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable. Take a moment to listen. His self prophecy is beyond words and understanding.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

January 11, 2016

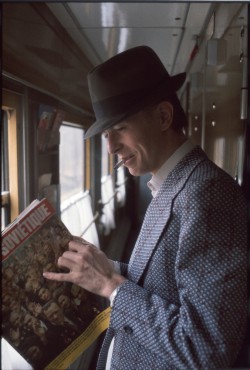

Photos of David Bowie in Russia, 1976

Photo by Andrew Kent. 1976. Train from Moscow > Helsinki

How awful to wake up this morning to learn that Dvid Bowie has died at 69. He did a masterful job keeping his illness secret, right through a flurry of press attention for the release of last week’s Blackstar album (which features Tedeschi Trucks Band bassist Tim Lefebvre). Two years ago, I wrote the following story for Guitar Afficionado’s Photo Finish feature. The discussed image as well as many other Kent/Bowie shots and thousands of other iconic rock images are available to purchase here at Rock Paper Photo.

**

Photographer Andrew Kent spent six months chronicling a 1976 David Bowie world tour. With a brief respite between Zurich and Helsinki, Bowie decided to do some Eastern exploring.

“David loved trains and already taken the Trans Siberian Express and decided to do a side trip to Moscow,” Kent recalls. “The band flew on to Helsinki, but he, his manager, his assistant and Jimmy [Iggy Pop] were headed to Moscow and asked if I wanted to join them.”

This was the height of the Cold War and Westerners faced strict restrictions on travel through the Soviet Union. Kent recalls that Bowie knew that one could get a transit visa from Zurich to Helsinki, passing through Poland and Moscow without political ramifications.

“We were ghosts until we got to Brest, Poland, where an albino KGB agent took us off the train and interrogated us. They took a Playboy magazine and some books of David’s and let us go, saying someone would meet us in Moscow, but no one did. We took a walk around Red Square, visited the famous GUM department store, had dinner at the Metropol Hotel, and then got back on a train and left.”

Kent was walking down a hallway when he saw Bowie reading a Russian Socialist magazine and snapped this photo. “It was a long trip with very little English reading material,” Kent says. “David was just looking for something to do; it was not a political statement.”

At the Russian border, Pop and Bowie were strip-searched; there seems to have been a lot of people smuggling religious icons in their body cavities.

“It was mostly a very low key trip, though it created a scandal in Scandinavia,” Kent says. “The train schedule was wrong and people were expecting us a day earlier. The publicist had lined up a lot of press to meet the train and interview David and when we didn’t show up there were banner headlines: ‘Bowie missing in Russia.’ We just showed up and walked off the train the next day.”

Photo by Andrew Kent, via Rock Paper Photo

Photo by Andrew Kent, via Rock Paper Photo

Photo by Andrew Kent via Rock Paper Photo

January 6, 2016

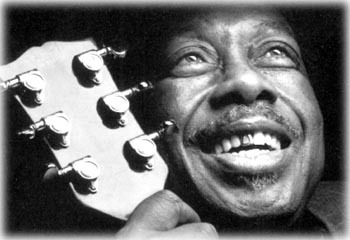

Jimmy Rogers, 1924-1997

Jimmy Rogers was a seminal guitar player -whether or not you’ve ever heard of him. I never did a massive interview with him, which is endlessly annoying, because I was supposed to do so several times. Circa 1995, I spoke with him several times and even set up a photo shoot with Danny Clinch, who took great pics, which I’d love to see. We at Guitar World put off doing the feature when we found out that he was working on an star-studded new album. We figured we’d do the story when that happened, said to be in a year or so. Sadly, Jimmy died in 1997 and the album, Blues Blues Blues– featuring Clapton, Richards, Page, Plant, Taj Mahal, Buddy Guy and many others, never came out until 1999. Do the math.

I wrote this short story for Guitar World circa 96. RIP Jimmy.

••••

As Muddy Waters’s lead guitarist from 1947-54, Jimmy Rogers helped pioneer Chicago Blues. He then went on to score a dozen hits as a solo artist, penning blues standards like “That’s Alright.” ‘Walking By Myself” and “The Last Time.” Still, for many years, Rogers languished in obscurity, despite praise by the likes of Eric Clapton, who once called him “one of the all-time great guitar heroes,” and recorded two Rogers tunes on From the Cradle. His prime solo material out of print, his royalties tied up in legal purgatory, Rogers continued to make excellent, unsung albums for small indie labels, without ever quite receiving his due. Until now.

The guitarist recently signed with Atlantic Records, for which he is currently recording a star-studded album, thus far featuring Clapton, Taj Mahal, Stephen Stills and fellow blues legend Lowell Fulson. Several other high-profile rockers may come aboard shortly. Just as significantly, Rogers has finally begun receiving the royalties due him from his own work as well as from From The Cradle and Gary Moore’s Still Got The Blues, which featured “Walkin’ By Myself.”

Photo by Michael Amsler

“It’s been a long time coming and it’s all welcome,” says Rogers from his Chicago home. “Making this Atlantic album is real nice—and so is cashing the royalty checks. So many of my beloved associates have passed on, so I just feel fortunate that mother nature let me stick around, to be here when the checks finally started rolling in.”

*

Want to learn a little more about Jimmy? Check out the following.

My friend Ted Drozdowski wrote a great piece for Gibson, whose headline sum sup rogers’ importance – Did Guitarist Jimmy Rogers Invent Chicago Blues?

Jas Obrecht did a good interview for Guitar Player in 1996, which you can find here.

December 19, 2015

Allman Brothers at American U. 12/13/70 Review

I reviewed the Allman Brothers Band at American University 12/13/70 for Guitar World when it was released by the band in 2002.

Duane Allman, probably at American U. Photo by Twiggs Lyndon. Featured in One Way Out: An Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

****

THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND

The Allman Brothers Band Recording Company

Though he died at the tender age of 24, Duane Allman left a tremendous mark on the musical world. In four short but action-packed years, Allman became rock’s first slide guitar virtuoso and helped write both the blues-rock and jam band canons on three studio and two live albums with the Allman Brothers Band. He also lit a fire under Eric Clapton on Derek and the Dominos’ Layla and produced enough great studio work to fill two two-CD anthologies, backing everyone from soul great Aretha Franklin to jazz flautist Herbie Mann. Despite – or because off — this legacy of great music, Allmans’ 1971 death left fans starving for more.

Like Jimi Hendrix, Allman combined deep blues feel and knowledge with a wide-open mind. Both also played with an endless sense of possibility tempered by an r&b session player’s discipline. Unlike Jimi, Allman did not leave behind miles of studio tape to be unearthed. He did, however, kick out the jams almost every night of his too-short adult life, and bootlegs and tape trading have long flourished among the faithful. The handful of adequately captured Duane-era ABB performances have been sought after and swapped like so many pieces of the Holy Grail, and with good reason. The band played with unmatched ferocity and combined great songs with a truly open approach that made each performance a unique entity. At Fillmore East is revered as rock’s greatest live album, but it merely captures in full sonic glory a typically great performance.

For all these reasons, the sudden appearance of a virtually unheard Duane-era ABB performance is big news, making it an excellent choice to debut the band’s series of sanctioned, self-released archive CDs. It doesn’t hurt, of course, that the band’s December 13, 1970 performance was top notch.

The sound is not as crystalline as that heard on radio-broadcast-based bootlegs, but producer Tom Dowd and his team have done an excellent job of breathing life into what was apparently an awful-sounding tape. Due to the limitations of working with a one-track master, you don’t quite get the band’s full-tilt power. Both the double drummer propulsion and Berry Oakley’s unique free range bass playing are somewhat muted, with Duane’s guitar and brother Gregg’s vocals dominating the mix.

With Duane’s concise slide riffs front and center, “Statesboro Blues,” “Trouble No More” and “Don’t Keep Me Wondering” all sound quite different than they ever have, despite succint, not particularly improvised versions. A rare live performance of “Leave My Blues At Home” boasts some particularly splendid interplay between Dickey Betts and Duane, but it is a mere prelude to the savage, almost 16-minute blitzkrieg through “You Don’t Love Me” which follows.

Here, Betts and Allman shine in all their glory. Each takes gripping solo flights, spinning the song’s blues riff into inspired, deeply personal sonic gold, before coming back together to toss ideas back and forth in a heated exchange. Betts’ melodic blues and hyper-charged country chug stand out. The album closes with a 20-minute ride through “Whipping Post,’ which is considerably different though only slightly less epic than the revered At Fillmore East version they would cut four months later.

American University is not a starting point for ABB novices –that would be Fillmore or Eat A Peach – but it is required listening for dedicated fans, who will continue to discover nuances to the band’s sound, and more reasons to revere the Allman/Betts team.

Buy the album here: American University 12/13/70.

December 18, 2015

Derek Trucks on Joyful Noise

From the archives and just dug out. I wrote this article for Guitar World in 2002. Enjoy.

Joyful Noise (Columbia) is Derek Trucks’ third album but the first that he could bear to listen to by the time it was released.

Joyful Noise (Columbia) is Derek Trucks’ third album but the first that he could bear to listen to by the time it was released.

“My first two albums were pretty good but they didn’t seem to represent what we sounded like when they came out,” says Trucks, who plays in the Allman Brothers Band as well as his own group. “This one does, because we’ve settled down as a band and we had the opportunity to put some really cool, different stuff on here. It should stand up as a statement for a long time to come.”

The “different stuff” includes guest vocalists whose diversity highlights the Trucks Band’s eclectic approach: soul crooner Solomon Burke, salsa star Ruben Blades, blues belter Susan Tedeschi, also known as Mrs. Derek Trucks, and Pakistani vocalist Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, who sings on the mystical, ancient “Maki Madni.” The rest of the album features five original instrumentals, where all these sounds mix and mingle with ease. What binds it all together is Trucks’ remarkable guitar work, played solely in open E and always with his fingers only.

While his straight playing has come a long way, Trucks’ slide work remains his calling card, as it has been since he started appearing with the Allman Brothers at age 12. Now 23, his every note radiates confidence and a distinctly off-the moment feel and he never sounds like he’s showing off.

“You never want to play everything you know,” says Trucks, who has been just as influenced by Indian sarod master Ali Akbar Khan as by Duane Allman. “I get bored when bands sound like there’s nothing more to be revealed. Everything you play should be a choice and you should be forcing yourself to stretch out and bring the audience with you. It’s easy to fall back on the licks people want to hear in the Allman Brothers and the rest of this little world, but it’s much more of a challenge and ultimately much more rewarding to turn them on to something they think they have no desire to hear.”

–Alan Paul

GUITAR: Washburn Custom, Gibson SG ’62 reissue

STRINGS: DR .11-.46

AMPLIFER: (Derek Trucks Band) ’63 Fender Super Reverb (Allman Brothers Band) 100-watt Marshall head through Marshall reissue cabinet

ALL-TIME FAVORITE ALBUMS: Wayne Shorter, Speak No Evil; Ali Akbar Khan, Signature Series, Vol. 2, John Coltrane, A Love Supreme, The Otis Redding Story, Freddie King, The Ultimate Collection

CURRENTLY LISTENING TO: Wayne Shorter, Footprints: Live

December 11, 2015

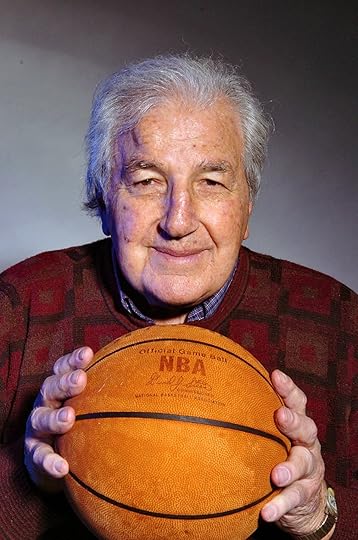

RIP Dolph Schayes – an interview with the big man

Dolph Schayes died yesterday at age 87. He was one of the great early NBA players and a bridge to the modern game. He was also bright, reflective and analytical – all of which is apparent in this 2002 interview I did for Slam. RIP Dolph, and condolences to Danny and the Schayes family.

Dolph Schayes died yesterday at age 87. He was one of the great early NBA players and a bridge to the modern game. He was also bright, reflective and analytical – all of which is apparent in this 2002 interview I did for Slam. RIP Dolph, and condolences to Danny and the Schayes family.

*

Dolph Schayes is the greatest Jewish basketball player of all time. Stop snickering and learn something; my tribe was a dominant basketball force in the first half of the twentieth century. Though the golden era of Jewish hoops came before the NBA’s 1946 formation, we were well-represented in the league’s early years. Still, Schayes stood out because he was a true star, one of the best players of the league’s first decade as demonstrated by his selection to the NBA’s 25th and 50th Anniversary Teams.

A 6-8, 220-pound forward, Schayes played in 12 straight All Star games and was an annual mainstay among the league leaders in points and rebounds, averaging 18.5 ppg and 12.1 rpg in 16 seasons. He also led the Syracuse Nationals to three Finals and the ‘55 title. An iron man whose durability was as remarkable as his skills, Schayes played in 764 straight games over 10 years.

“He once broke the wrist of his shooting hand and had the doctor leave his fingers out of the cast and never missed a game,” recalls Bill Russell. “He was completely tenacious and he worked as hard as anyone ever could have.”

Schayes’ opponents were forced to work equally hard or risk being embarrassed because he never quit moving on the court, driving defenders to distraction and exhaustion, a style he sums up simply: “Basketball is a game of movement, so move!”

Schayes had a high arcing set shot with deep range and possessed an agility and grace rare for big men of the era, driving to the basket and feasting at the free throw line. He retired in 1964 as the NBA’s All-time leading scorer (19,247 points) and coached the 76ers for three years before becoming the NBA director of officiating for three seasons. His son Danny played 18 seasons in the league. Now 74 years old, Dolph Schayes is a businessman in Syracuse.

SLAM: In 1951, a point-shaving scandal rocked New York college basketball and helped the NBA get its footing. What do you recall about that?

SCHAYES: It was shocking. I knew a couple of the guys very well and had played a lot of ball with them. They were good kids from good families and I never could understand how they could have stabbed the game they loved in the back. College basketball in New York City never fully recovered.

As for helping the pro game, I think that’s been overstated. The Knicks did not have a sudden surge in attendance, though more people gave them a chance and started paying attention for the first time. New York was the basketball mecca and college was king by a long shot. Once people couldn’t trust the college game, some checked out the pro game, but that was in big trouble, too. We had no clock and a lot of faults. People looked at the slow pace and at big guys like George Mikan and said pro basketball was just for overgrown pituitary cases. Baseball and football were numbers one and two and pro basketball wasn’t even in the same universe.

SLAM: You were on the Syracuse Nationals when the team’s owner Danny Biasone introduced the 24 second clock in 1954. Did you have any idea that it was revolutionizing the game?

SCHAYES: No. To get paid to play a game I love was enough for me, no matter what the rules were. The coaches were the same. Guys like Red Auerbach didn’t worry about the health of the game; they played to win. Before the clock that meant that if you were leading, you held the ball and if you were losing you fouled like crazy. Looking back, it was a nightmare. The games were long, dull and violent and the 24-second clock saved it.

SCHAYES: No. To get paid to play a game I love was enough for me, no matter what the rules were. The coaches were the same. Guys like Red Auerbach didn’t worry about the health of the game; they played to win. Before the clock that meant that if you were leading, you held the ball and if you were losing you fouled like crazy. Looking back, it was a nightmare. The games were long, dull and violent and the 24-second clock saved it.

Danny came up with 24 seconds using the following mathematical formula. In the 53-54 season, each team averaged 60 shots a game –120 shots — 48 minutes was 2,880 seconds so divide 120 into 2,880 and you come up with a shot every 24 seconds. That formula wouldn’t make sense today, but almost 50 years later, 24 seconds remains.

SLAM: Why was basketball such a popular Jewish sport?

SCHAYES: It’s fair to say that Jews dominated basketball and that started in the 30s in all the big cities. I think it was simply because Jews lived in ghettoes and basketball is a great schoolyard game. You don’t need a lot of space or equipment and you can adapt it to how many players you have.

I’ve heard the joke a million times that “Jews in Sports” must be the thinnest book in the world. Actually, I’ve seen a lot of great players working at the Maccabi Games [International Jewish Olympics], but they tend to be Division 2 or 3 guys. And, hey, the Jewish Book of Doctors, Lawyers and Accountants is very thick.

SLAM: You were a big man who played like a guard. How did you develop those skills?

SCHAYES: Playing in the New York City schoolyard, where the game was all movement. I happened to be tall, but I learned the fundamentals well — the give and go, setting picks, passing, fast breaks and everything else that we called “New York style.”

I was a center in college but I was a high post guy, feeding cutters and rebounding. Going to pro ball, I clearly wasn’t big and strong enough to play center against giants like Mikan so I kept evolving. I never had a postup game, which really hurt me eventually. Later in my career, teams would put smaller guys on me to stop my shooting and driving and I wasn’t able to exploit my height advantage. I would just take bigger guys outside and drive or shoot my setshot.

SLAM: Your range went to 30 feet. How many more points would you have averaged with a three-point line?

SCHAYES: Quite a few, but I didn’t score out there as much as people think. My game was slashing to the basket, getting fouled and making three-point plays. But I hit enough deep shots to keep them honest and make them come out.

The real secret to my success was I could shoot with either hand. Ironically, I became ambidextrous as a direct result of breaking my right hand. I kept playing with a cast and had no choice but to rely on my left hand, which changed everything. Every clinic I’ve ever done, I tell the kids, “Go left, young man.” Tie your right hand behind your back, cover it with a newspaper — do anything to immobilize it. Learn to use your weak hand and deny your man his strong hand and you can go far in this game.

SLAM: You were known for your compulsive practice habits and incredible work ethic.

SCHAYES: I always stayed on before and after practice. I just think that if you want to excel at anything, be it basketball, dance or the piano, you need to practice a lot. As for the work ethic, I’m just the kind of guy who takes what he does seriously. I never missed a day of school, I’ve rarely missed work and I played all those straight games; my streak only ended when I broke my cheekbone.

Guys hated to play against me because my stock in trade was constant movement. I was quick but not fast so I would move my defender into picks, from one end of the court to another and wear him out until I had him tired and off-guard. If we were both moving I had the advantage, because I could switch directions when I got the ball and he would be off balance. And I had an excellent running shot and great anticipation. I always knew where the ball was and had a good idea of where it was going, but I never stopped and thought about it; it was all instinctual, which I developed from playing so much. You can’t think about basketball or you ruin your game. It is an instinctive game.

SLAM: Those instincts allowed you to grab so many rebounds without being able to jump very well.

SCHAYES: It was anticipation and one other thing — I disobeyed a basic basketball rule and never boxed out. I figured that if I had the inside position I had enough of an advantage to just go get the ball. And coaches left me alone because I got it. The great thing about basketball is it’s a live ball. If someone’s in your way, push them out of the way, go around them or over them, whatever it takes. And my instincts told me where the ball was going from the angle and depth of the shot. That also gave me an advantage on the break because I could take off a moment before my opponent and that first step was all I needed.

SLAM: Some say Clyde Lovelette was the dirtiest player ever. What do you remember about him?

SCHAYES: He was a heavy, physical player who used his body, but I don’t know if he was the dirtiest, even of our era. There were guys on the Celtics who gave me fits, like Jungle Jim Loscutoff. He would pull down your pants, stick a finger in your eye and an elbow in your gut. But we didn’t necessarily even think of him as dirty. It was a tough game and we developed intense rivalries because there were so few teams. We had tremendous fights with the Celtics all the time and the fans got involved too, especially in Syracuse, where they would run on the courts, throw beers on players and all the rest.

One of the most memorable fights happened when Loscutoff lowballed me and I broke my wrist and smashed my face. One of the Celtics said. “He got what he deserved,” which started a huge brawl. My teammate Paul Seymour smashed this guy and wouldn’t let him go; the police had to get him off by grabbing him by his nostrils and yanking. It’s hard to imagine all this stuff happened, but it did. I sure wish we had some decent film footage of the games. But filming was considered an absurd luxury because there was no money.

SLAM: You were a great foul shooter, a skill you honed through an unorthodox practice routine. Describe it.

SCHAYES: A basketball diameter is 10 inches and a rim is 18 inches so I made a 14-inch rim I put in to practice on. Few people could do that because it was so frustrating that it drove everyone but me nuts. That led to me shooting very high, which basic physics tells you is the best angle – the hole is bigger from above than from the side. And I shot with two hands, which was rare even in my day, because I felt it didn’t make sense to shoot free throws differently from your regular shot, which would limit the benefits of your practice. So my outside shooting became abnormally high as well. They called them rainmakers because they went through the clouds. As a coach, I used to challenge poor free throw shooters to contests shooting 25 shots and said that mine only counted if they swished. I would still win and drive them nuts.

SLAM: You weren’t able to help Wilt Chamberlain when you were his coach. He shot about 51 percent from the line with or without you.

SLAM: You weren’t able to help Wilt Chamberlain when you were his coach. He shot about 51 percent from the line with or without you.

SCHAYES: I sure tried. When he was traded to the Sixers, Wilt told his sister, “I’m finally going to learn how to shoot free throws from Schayes.” I think the biggest problem was the size of his hands –same with Shaq. It’s impossible to have the balls rest properly on the fingertips of such huge hands. But we worked endlessly and Wilt did really well in practice but something psychological went wrong in games. And that had a huge impact, especially at the end of games. For instance, we were on the wrong end of the famous “Havlicek stole the ball” play [in the closing seconds of Game 7 of the ’66 Eastern Finals]. That play came about because I didn’t want to do the obvious and toss the ball to Wilt because they would have fouled him and put him on the line.

By the way, I think he would dominate Shaq. Russell might have trouble with him, but Wilt’s strength would keep Shaq away from the spots from which he kills everyone.

SLAM: Your career spanned generations and you ended up playing against Elgin Baylor and Oscar Robertson, the guys who really started the next great transformation of the game.

SCHAYES: Two amazing players who were the first guys to really hang in the air. You would jump up with Elgin, come down and look up to see him still up there. And Oscar could do everything — shoot from outside or in, pass, rebound, dribble — and completely dominate a game. They were just amazing talents who had the same sort of tremendously honed basketball instincts we talked about. And again, they came from the ghetto and played a lot of basketball and developed terrific skills to go along with a phenomenal athleticism.

December 2, 2015

The Allman Brothers Band Memorabilia – an Interview

I’ve been really enjoying a new book, The Allman Brothers Band Classic Memorabilia, 1969-76. The topic is pretty much right in the title.

The book highlights individual collectibles, including band instruments and equipment, t-shirts, apparel and merchandise, autographs, bookkeeping documents, passes, posters, tickets, programs, promotional items, vintage photographs, and more. Duane’s Galadrielle Allman wrote the introduction.

The authors are Willie Perkins, the Allman Brothers road manager from 1970-76 and Jack Weston, an avid ABB collector who hipped me to the awesome W. David Powell coloration of David and Flournoy Holmes that graces the front and back inside covers of One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band. Willie is also the author of No Saints, No Saviors: My Years with the Allman Brothers Band.

I caught up with Willie and Jack for the following interview.

Duane 1970 – Twiggs Lyndon photo.

Willie – you were in the middle of a hurricane and at the center of what many consider the best rock band ever. How aware were you of all that at the time, and how much were you just hanging in on for dear life every day?

PERKINS: A lot of hanging on! Linda Oakley told me recently that the band guys had me so flipped out my eyes were spinning around in their sockets like a cartoon character. We were so busy getting it done that there was little time for reflection as I note in the book. I remember early on saying: “This is the best band in America, only America doesn’t know it yet.” That was somewhat prophetic.

You kept a lot of documents and files, so you must have had some sense that this stuff would have historical significance. Do you remember when it started to occur to you that things like tour ledgers and guitar cases would be of interest to people?

PERKINS: Probably around the time of Duane’s passing. We certainly knew those guitars had to be secured that weekend before they “wandered” off. I don’t think anyone began collecting for monetary gain. I know that I wanted to preserve from a historical perspective any important documents I had possession of. By the late 1990’s I realized business checks signed by Duane definitely had collector appeal and monetary value. I receive almost weekly social media inquiries regarding dates and sequences of shows performed and am so glad I held on to copies of the monthly personal appearance financial reports. That info is priceless to me and I have the most comprehensive records for 1971 – 1976.

Jack, when did you start collecting ABB memorabilia?

WESTON: I first started to collect Allman Brothers Band memorabilia in the late 1980’s. It was driven by my love of the band’s music which first began in 1971 soon after I heard the band’s At Fillmore East. I began to trade tapes with other tape traders that placed ads in the back section of Relix magazine. Most of the traders at this time were trading Grateful Dead cassette concert tapes but some were also trading Allman Brothers Band shows. In addition to concert tapes some of the Allman Brothers Band traders were trading posters, handbills, tickets, photos , and other ephemera from the band’s early days. When the Allman Brothers Band’s magazine Hittin’ The Note was first published in the early 1990’s I became a subscriber and it had a traders section in it as well which of course fueled the fire.

Is there one section or even item in the book that you would like to call special attention to? What are you most proud about?

PERKINS: I am so glad we led off the book with “instruments and musical equipment” because the band was certainly all about the music. I am pleased with the high definition and clarity of the images. Also, Jack and I gave the book design concept to the team Burt & Burt and they delivered exactly what I had in mind and our publishers Mercer University Press gave us virtually everything we asked for and didn’t edit a single word or image. The colors and concept just pops right off the page.

WESTON: It would have to be Dickey Betts’ 1968 Fender Bassman amplifier, one of the first two purchased by the band in early 1969. It was at first used by Duane Allman, Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley. Then it became Dickey Betts’ stage amp. The band’s first road manager Twiggs Lyndon wrote “ Allman Bros” and “Dick” on the back panel of the amp in white marker pen. The Lipham Music Co invoice for this amp’s purchase is also pictured in this chapter showing the amp’s serial number. I learned a great deal after having this amplifier restored to working condition. When I first acquired the amp the two output tubes in it were modern Groove Tubes. These were replaced with a set of original matched 1960’s Fender brand 6L6’s. My friend Skip Simmons of Sacramento, California did a historical restoration of the amp’s electronics. Only the power supply capacitors needed replacement. All the other active electronics in the amp are vintage original.

There are a lot of great and beloved bands but none have their own museum like The Big House. What do you attribute this to?

PERKINS: I give 100% credit to the idea of restoring and conserving the Big House to Kirk and Kirsten West. There have been many financial and creative contributions made by countless others, but they had the foresight and love to get the ball rolling. The band inspired a lot of love from a lot of people with the soul, passion and originality of their music. The museum is manned by a great staff and volunteers as well. Nothing like it for any band before or since!

WESTON: The history of The Allman Brothers Band spans over 50 years. As a result The Allman Brothers Band has a very large and loyal fan base, which encompasses virtually all age groups. From the time the band played free concerts at Piedmont Park in Atlanta until its final concert at The Beacon Theater in 2014 it has always been regarded as “The People’s Band. I can’t recall many other band’s having this unique type of fan base other than The Grateful Dead. As you know, The Big House Museum was once the home of the band in the early years. It is not just a museum. It is a home. This unique combination is why The Big House has so many fans coming back year after year to share in the music, culture, and legacy of their favorite band.

What about the Allman Brothers inspires so much passion?

WESTON: To me the passion stems from “The Brotherhood,” which was established early on between the founding band members, their families, and the band’s original road crew. In the beginning it was a strong cohesive brotherhood that still exists today amongst the band’s contingent of loyal fans. This passion was inspired early on by founding member Duane Allman making the musical journey revolutionary as well as evolutionary.

Willie, a lot of your tour documents are now in the Big House Archives and were incredibly helpful for me in researching One Way Out. So thanks for that.

PERKINS: I am glad so many of my financial records and other items of interest made it to the Big House Museum and they will be preserved for current and future fans and historians. I am glad Jack’s and my book will do the same in the printed word and image medium as well.