Alan Paul's Blog, page 15

March 13, 2017

Allman Brothers Band At Fillmore East 46th Anniversary

In honor of the 46th anniversary of the last night of the magical Fillmore East turn that produced the epic album. I present the following excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band.

This is a partial, very abridged version of Chapter 8. To read the full story of the making of At Fillmore East, pick up a copy of One Way Out.

Chapter 8.

LIVE ALIVE

Though their first two releases had caused barely a ripple in the marketplace, the band was drawing raves for their marathon live shows that combined the Grateful Dead’s go-anywhere jam ethos with superior musical precision and a deep grounding in the blues. A live album was the obvious solution. To cut the record, the band played New York’s Fillmore East for three nights — March 11, 12 and 13, 1971. They were paid $1250 per show.

The Allman Brothers Band had made their Fillmore East debut December 26-28, 1969, opening for Blood, Sweat and Tears for three night. Promoter Bill Graham loved the band and promised them that he would have them back soon and often, paired with more appropriate acts, and he lived up to this vow.

On January 15-18, 1970, the ABB opened four shows for Buddy Guy and B.B. King at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. They were back in New York on February 11 for three nights with the Grateful Dead. These shows were crucial in establishing the band and exposing them to a wider, sympathetic audience on both coasts.

TRUCKS: You can’t put in words what those early Fillmore shows meant to us. The Fillmore West helped us get established in San Fran and it was cool – especially those shows with B.B. and Buddy – but the Fillmore East was it for us; the launching pad for everything that happened.

ALLMAN: We realized that we got a better sound live and that we were a live band. We were not intentionally trying to buck the system, but keeping each song down to 3:14 just didn’t work for us. We were going to do what the hell we were going to do and that was to experiment on and offstage. And we realized that the audience was a big part of what we did, which couldn’t be duplicated in a studio. A light bulb finally went off; we need to make a live album.

BETTS: There was no question about where to record a concert. New York crowds have always been great, but what made the Fillmore a special place was Bill Graham. He was the best promoter rock has ever had and you could feel his influence in every single little thing at the Fillmore. It was just special. The bands felt it and the crowd felt it and it lit all of us up. The Fillmore was the high-octane gig to play in New York — or anywhere, really.

Bill Graham introducing the ABB. Photo by Sidney Smith. All rights reserved.

ALLMAN: That was the place to record and we knew it. It was a great sounding room with a great crowd, but what really made it special was the guy who ran it. Bill Graham called a spade a spade and not necessarily in a loving way. Mr. Graham was a stern man, the most tell-it-like-it-is person I have ever met and at first it was off-putting. But he was the fairest person, too, and after knowing him for while, you realized that this guy, unlike most of the other fuckers out there, was on the straight and narrow.

PERKINS: The Fillmores were so professionally run, compared to anything else at the time. And he would gamble on acts, bringing in jazz and blues and the Trinidad/Tripoli String Band – and he had taken a chance on the Brothers, which everyone appreciated and remembered.

DOWD: I got off a plane from Africa, where I had been working on the Soul To Soul movie [capturing a huge r&b, jazz and rock concert held in Ghana], and called Atlantic to let them know I was back and Jerry Wexler said, “Thank God; we’re recording the Allman Brothers live and the truck is already booked,” so I stayed up in New York for a few days longer than I had planned.

It was a good truck, with a 16-track machine and a great, tough-as-nails staff who took care of business. They were all set to go. When I got there, I gave them a couple of suggestions and clued them in as to what expect and how to employ the 16 tracks, because we had two drummers and two lead guitar players, which was unusual, and it took some foresight to properly capture the dynamics.

Dowd was thrilled with what he was hearing until the band unexpectedly brought out sax player Rudolph “Juicy” Carter and another horn player, as well as harmonica player Thom Doucette, a frequent guest who had played on Idlewild South.

DOWD: We were going along beautifully until the fourth or fifth number when one chap looked up and asked, “What do we do with the horns?” I laughed and said, “Don’t be a smart ass,” thinking he was joking, but three horn players had walked on stage. I was just hoping we could isolate them, so we could wipe them and use the songs, but they started playing and the horns were leaking all over everything, rendering the songs unusable.

JAIMOE: Dowd started flipping out when he heard the horns, but that’s something that could have worked. There’s no way that it would have ruined anything that was going on. It wasn’t distracting anyone, and it was so powerful.

Photo by Sidney Smith – Tulane U. homecoming, 1970. All rights reserved.

BETTS: Dowd was going nuts, but we were just having fun and everyone was enjoying it. We didn’t change our approach because we were recording. We never hired any of those guys. They’d just show up and sit in, and we all dug it.

PERKINS: The horn players would pop up and just sit in for a few songs. Those guys were friends of Jaimoe’s – we just knew them as Tic and Juicy and everyone liked their playing. Nothing was rehearsed with them. They’d just get up and play. Them showing up at those Fillmore gigs was a surprise to me and I didn’t think it was a good idea.

JAIMOE: Tic was a tenor player, Juicy played baritone and soprano – sometimes together, at the same time – and there was an alto player we called Fats, who was not at the Fillmore and didn’t come around as much. We had played together in Percy Sledge’s band and I knew them from Charlotte, NC. Good guys and good musicians.

PERKINS: They often had some heroin with them and were welcomed for that as well.

JAIMOE: I don’t know about that; if they showed up with a little something, it was probably because Duane or someone asked them to do so.

DOUCETTE: The plan was to bring on the horns full time. Duane would have liked to have 16 pieces. Duane had six different projects that he wanted to do and he just thought he could do it all at once on the same bandstand.

DOWD: I ran down at the break and grabbed Duane and said, “The horns have to go!” and he went, “But they’re right on, man.” And I said, “Duane, trust me, this isn’t the time to try this out.” He asked if the harp could stick around and I said, “Sure,” because I knew it could be contained and wiped out if necessary.

PERKINS: Doucette had played with the band a lot so he was a lot more cohesive with what they were doing. Duane loved those guys, but he would also listen to reason and I don’t think he put up any fight with Dowd.

DOWD: Every night after the show we would just grab some beers and sandwiches and head up to the Atlantic studios to go through the show. That way, the next night, they knew exactly what they had and which songs they didn’t have to play again. They would craft the setlist based on what we still needed to capture.

BETTS: You have to listen to it being played back to get a sense of whether or not it came together and we loved having that opportunity. We just thought, “Hey this is cool… I didn’t know I did that… That sounds pretty neat.” We were just enjoying ourselves and the opportunity to listen to our performances. We didn’t do a lot of that board tape stuff and we weren’t real hung up on the recording industry anyhow. We just played and if they wanted to record it they could. We were young and headstrong: “We’re gonna play. You do what you want.”

We just felt like we could play all night and sometimes we did. We could really hit the note. There’s not a single fix on there. All we did was edit some of the harmonica out, where there was a solo that maybe didn’t fit. It wasn’t doctored up, with guitar solos and singing redone in the studio, as on so many live albums. Everything you hear there is how we played it. We weren’t puzzled about what we were playing. We were a rock band that loved jazz and blues. We really loved the Dead, Santana, the Airplane, Mike Finnigan, and all the blues and jazz greats.

TRUCKS: We were listening to people like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and emulating them and trying to add that level of sophistication to our music – to add jazz and improvisation to blues, rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

DOWD: The Fillmore album captured the band in all their glory. The Allmans have always had a perpetual swing sensation that is unique in rock. They swing like they’re playing jazz when they play things that are tangential to the blues, and even when they play heavy rock. They’re never vertical but always going forward, and it’s always a groove. Fusion is a term that came later, but if you wanted to look at a fusion album, it would be Fillmore East. Here was a rock ’n’ roll band playing blues in the jazz vernacular. And they tore the place up.

BETTS: There’s nothing too complicated about what makes Fillmore a great album: that was a hell of a band and we just got a good recording that captured what we sounded like. I think it’s one of the greatest musical projects that’s ever been done in any genre. It’s an absolutely honest representation of our band and of the times.

JAIMOE: Fillmore was both a particularly great performance and a typical night. That’s what we did!

ALLMAN: You want to come out and get the audience in the palm of your hand right away: “1-2-3-4, bang! I gotcha!” That’s what you gotta do. You can’t be namby-pamby; you can’t be milquetoast with the audience.

WALDEN: Atlantic/Atco rejected the idea of releasing a double-live album. Jerry Wexler thought it was ridiculous to preserve all these jams. But we explained to them that the Allman Brothers were the people’s band, that playing was what they were all about, not recording, that a phonograph record was confining to a group like this.

Excerpted from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band (St. Martin’s Press). Copyright 2014, Alan Paul. All rights reserved.

March 6, 2017

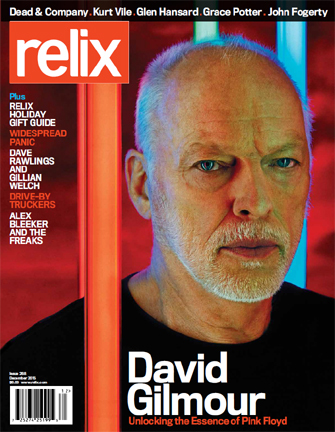

An Interview with David Gilmour

I interviewed David Gilmour in October, 2015, for a Relix cover story. Today is his birthday. Good enough reason to share the story with you.

I interviewed David Gilmour in October, 2015, for a Relix cover story. Today is his birthday. Good enough reason to share the story with you.

David Gilmour’s guitar sound is completely distinctive: the tone, the touch, the phrasing. Anyone with a passing familiarity with Pink Floyd – which is to say anyone who’s turned on a radio in the last 40 years – knows Gilmour’s work and has at least one of his riffs buried deep in his or her cerebral cortex.

Seconds into his recent solo album, Rattle That Lock , Gilmour’s guitar introduces itself and reminds you of all this. The album opens with a swirly atmospheric intro to the instrumental, “5 AM”, before the guitar blasts through like a high-powered beam of light slicing through dense London fog. It may as well scream, “I am David Gilmour and this is my album.”

, Gilmour’s guitar introduces itself and reminds you of all this. The album opens with a swirly atmospheric intro to the instrumental, “5 AM”, before the guitar blasts through like a high-powered beam of light slicing through dense London fog. It may as well scream, “I am David Gilmour and this is my album.”

Gilmour laughs at this thought. On the phone from his London studio, he says that yes, he understands the question. He is certainly aware of the distinctive power of his guitar and doesn’t shy away from the idea that those first notes are a means of saying hello and reminding listeners of who he is.

After all these decades as a singular player, does Gilmour still have to work at achieving this distinct sound? “No, I don’t,” he says. “It’s something that just arrives naturally at this point. I’ve no idea how or where it comes from. It’s nothing I ever attempted. I don’t know if anyone could actually set out to sound as distinctively as possible. It was just one of those strange mysteries. I think there’s some kind of strange peculiarity or my lack of coordination between hands that gives it something rather off and thus distinct. I’ve thought about it a lot but I can’t come up with precisely what it is.

“It’s a gift I suppose.”

A gift that just keeps giving. Pink Floyd was the biggest in the world during its peak, a remarkable six-year run that included 1973’s The Dark Side of the Moon, 1975’s Wish You Were Here and 1979’s The Wall, all multi-platinum worldwide hits. Bassist Roger Waters wrote all the lyrics on these epochal works, but Gilmour composed much of the music and sang the most memorable songs. His guitar playing was magnificent throughout, with parts that were essential to the songs, not mere adornments or instrumental passages.

and 1979’s The Wall, all multi-platinum worldwide hits. Bassist Roger Waters wrote all the lyrics on these epochal works, but Gilmour composed much of the music and sang the most memorable songs. His guitar playing was magnificent throughout, with parts that were essential to the songs, not mere adornments or instrumental passages.

“David Gilmour wrote solos that millions of people can hum,” says Warren Haynes. “You can’t separate his guitar parts from the songs and that’s incredibly rare. He created something uniquely him, which is the ultimate accomplishment as an instrumentalist.”

Gilmour’s distinct tone, lyrical playing and singing voice run like a continuous thread through the work of Pink Floyd and his four solo albums. Gilmour says that he does not feel burdened by any pressure to live up to his own esteemed history.

“I work pretty hard, tirelessly and obsessively on any project until I think it’s about as good as I can get it,” he says. “You always think you can take it a little bit further, and finally feel ready to finish when I’m hovering over wondering what else I can possibly do to a track. By then I’m always pretty convinced that what I’ve done is good, and I sort of suffer shocks later if people don’t like it.”

Much of Rattle That Lock is a collaboration between Gilmour and his wife, the writer Polly Samson, who penned the lyrics to half the songs, including the title track, which is inspired by John Milton’s 1667 epic poem Paradise Lost exploring the fall of man in 10 books- not exactly typical rock fare.

exploring the fall of man in 10 books- not exactly typical rock fare.

“Polly’s a writer and just had a book out earlier this year called The Kindness , which had a theme that was very related to Paradise Lost

, which had a theme that was very related to Paradise Lost ,” Gilmour says. “She spent a lot of time reading the book and trying to understand what it’s all about and having spent the last three or four years working on that, she found she couldn’t let go of Paradise Lost that easily and it made its entrance again on this song.”

,” Gilmour says. “She spent a lot of time reading the book and trying to understand what it’s all about and having spent the last three or four years working on that, she found she couldn’t let go of Paradise Lost that easily and it made its entrance again on this song.”

Many of Samson and Gilmour’s collaborations come about by her hearing pieces of his music, sometimes even unfinished songs, and feeling lyrical inspiration. Some of the snippets and different pieces of music were put together and assembled by co-producer Phil Manzanera. The Roxy Music guitarist served in the same role on 2006’s On The Island, Gilmour’s previous solo album, and also plays in his touring band.

Many of Samson and Gilmour’s collaborations come about by her hearing pieces of his music, sometimes even unfinished songs, and feeling lyrical inspiration. Some of the snippets and different pieces of music were put together and assembled by co-producer Phil Manzanera. The Roxy Music guitarist served in the same role on 2006’s On The Island, Gilmour’s previous solo album, and also plays in his touring band.

“Phil is a very old friend and he’s full of enthusiasm and a great help when putting together these things,” says Gilmour. “I have thousands of little bits of demos that I occasionally go through, but he loves doing that kind of hunting. And he’ll make little notes, join thing together on tape and say, ‘You could do this, and have a lovely song.’ A couple of tracks started out that way. ‘Today’ and ‘Faces of Stone’ both came about through that sort of process.

“Songs have to reveal themselves to you in a way. Some of the choosing process is the songs choosing themselves. One of them might inspire Polly to write words, for instance. If that happens, the song will move right up the priority list. Same if I hear a vocal melody presenting itself. I consider myself a singer as much as I am a guitar player and I love the popular song, the voices and everything mixed together that makes a song a song.”

One of the collaborations between Samson and Gilmour is “The Boat Lies Waiting,” a bittersweet reflection on the death of Pink Floyd keyboardist Rick Wright, who passed away of cancer in 2008. The song also includes gorgeous harmony vocals by Graham Nash and David Crosby.

“Rick had a 60-foot yacht and he loved sailing it around the world,” says Gilmour. “The music to ‘The Boat Lies Waiting’ was written first and the rhythm of the piano reminded Polly of a rolling boat on the ocean and it’s very easy from that to make the connection from that to Rick – for those of us who knew him well. Other people of course knew Rick primarily as a musician, but he was an old seafarer for much of his life. It was as much a part of his identity as being a musician, and as much how we thought about him.”

Wright left Pink Floyd in 1978, during the recording of The Wall, during which the other members felt he was not pulling his weight. He returned to the band almost a decade later, though not as an official member but rather a contributing musician, eventually being restored to partner. Whatever issues there were between the old collaborators seem to have been long since and fully buried. Wright performed regularly in Gilmour’s solo touring band. The guitarist has profoundly felt the loss of his longtime friend and musical collaborator.

“Sometimes you don’t realize what you’ve got until it’s gone,” says Gilmour. “There have been many moments since [Rick’s death] when I have been looking for something – a keyboard, a piano, a certain sound to complete a song- and the person I would naturally go to for those things is no longer around. It’s difficult developing that kind of rapport – a telepathic musical relationship – with people I do not know as well.

“Our relationship developed over many years and we knew what the other was thinking. We could communicate so much without saying more than a few words – or nothing at all. We were a step ahead of each other all the time. I knew what he was going to do next and he knew what I was gong to do next. That’s not something that’s easily replaced.”

Anyone who has ever listened to Pink Floyd knows that no keyboardist could possibly come up with better, more appropriate accompaniment or complementary parts to a David Gilmour melody or guitar line than Rick Wright. Throughout their greatest works, Gilmour and Wright’s musical ideas mesh seamlessly into one.

It’s hard to overstate Pink Floyd’s impact on classic rock and popular culture of the 70s and 80s, or Gilmour’s role in the band. Floyd was formed in London in 1965 by guitarist Syd Barrett, bassist Roger Waters, keyboardist Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason and quickly began making their mark with sonic freakouts and psychedelic light shows. By August 1967, the band had a hit with their first full album, Pipers at the Gates of Dawn, recorded at Abbey Road Studios, next to the Beatles. But Barrett’s always erratic behavior was growing ever more unreliable, and Gilmour, an old friend, was brought in to supplement and strengthen the group. After a few five-man shows, Barrett was out and Gilmour was in as onstage frontman/singer/lead guitarist. The stated plan was for Barrett to remain as an offstage songwriter, but he quickly faded out of the picture. The band would continue to be haunted by their original leader, and much of their greatest work explored his mental disintegration and its impact on everyone else.

The band continued to grow and expand, both commercially and artistically, and they exploded into a full-blown phenomenon with 1973’s Dark Side of the Moon. The title refers not to astronomy but to the human psyche and specifically Barrett’s condition. The album stayed on the Billboard charts for 14 years and has sold over 40-million copies worldwide. It was a conceptual, lyrical triumph for Waters, who wrote all the lyrics, and a musical statement by Gilmour, who wrote much of the music and sang the most iconic songs on this most iconic of albums, including “Money,” “Breathe,” “Us and Them” and “Time.”

Floyd’s next album, 1975’s Wish You Were Here, continued to explore similar themes; it’s no secret who the title “you” referred to, and the album open and closed with the epic salute to Barrett, the nine-part “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” Barrett visited Abbey Road Studios while the band was recorded the song, and his shambolic appearance and mental state shook everyone to their core. While Waters wrote the lyrics to these songs, Gilmour’s cutting guitar made them indelible.

The iconic riff that opens “Wish You Were Here” – another ode to Barrett – is a perfect example of Gilmour’s ability to craft unforgettable parts. Anyone with a modicum of facility on guitar can play this simple riff, but it is absolute perfection, setting a tone and pattern for the song that carries it through and digs it into your brain.

Says Haynes, “David’s sense of melody and his ability to play something that becomes a crucial part of the song rather than merely a solo interlude is what really stands out. He came up with all these hooks and riffs and memorable phrases that nobody else would think of in exactly the same way. That, combined with his unique tone and feel, are incredibly memorable. What he played on songs like ‘Time,” ‘Money’ and ‘Wish You Were Here’ are embedded into our brains just as much as the songs themselves are. David plays guitar like a singer; he’s telling a story. And he plays and sings the same phrases and melodies, just as B.B. King did.”

Haynes’ evocation of B.B. King in relation to Gilmour is telling. His playing is redolent of blues authority and feeling, albeit often in very different settings. Like most of his British peers, both the future blues of Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck and the more purist blues work of Eric Clapton and Peter Green in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers profoundly influenced Gilmour.

“All of those guys were incredible and I spent time trying to learn how to play their licks perfectly,” says Gilmour. “I would suggest any young player should try to sit down and do that. You will wind up knowing how to play their stuff quite well but eventually you will find your own style form that. It forces its way out of the copying.”

Gilmour is also an excellent slide player, generally employing a lap or pedal steel instrument. His work there has no real antecedent; he says he was never much impacted by great slide players like Duane Allman or Ry Cooder.

“My goodness, I don’t know where the slide came from!” he exclaims. “I believe it all started in a junk shop in Seattle where I bought a Fender double-neck lap steel guitar second hand for almost nothing in 1970, and brought it home and started tinkering. It’s a very expressive thing, and I just found that I had an ear for it, as some people do.

“I have to confess to not being a purist in my guitar approach. I know many people who have sat down and listened to nothing but blues guitar players and tried to nail that perfectly. I respect that, but it’s not me. I like so many different things.

“Singers, saxophonists and piano players also impacted my guitar playing; anyone anywhere who wrote or played beautiful melodies did, because that’s what I was attracted to. Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story was a huge influence, for example, but I hate to even mention anything, because for everything I say, I leave 100 others out. I am very, very broad-palette person.”

For all his broad palettes and influences, much of Gilmour’s most memorable playing, as in “Comfortably Numb” and “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” is essentially blues. The variation from standard blues themes in lyrical and musical composition and melody easily distracts from this truth. For all of Pink Floyd’s progressive leanings what could be a more appropriate musical form to deliver so many songs about the mental illness and disintegration of a beloved friend?

A decade after Barrett’s 2006 death and 40 years after recording “Wish You Were Here” and “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” Gilmour says he still thinks daily about his old friend.

“Syd’s was a creative life that had so much promise and was cut cruelly short,” says Gilmour. “The regret of Syd is that this really very, very warm, lovely intelligent guy stopped being the creative person that he had been, and that’s just a deep, abiding sadness.”

But, Gilmour adds, he also thinks daily of Wright and countless other friends who have left the mortal coil. Part of aging is being forced to make sense and order of all the people no longer with us. Following Wright’s passing, Gilmour went back to some music they had recorded but never released as Pink Floyd. Most of the tracks were cut during the 1994 The Division Bell sessions. Gilmour and Mason returned to the music, working with other musicians to create the 2014 mostly instrumental album The Endless River.

“Lots of beautiful pieces of music I remembered had been sitting there,” Gilmour says. “It was one of those pieces of tidying up I thought should be done. It suggested itself and we went back and listened to them all again. They sounded great and I thought I wouldn’t have to do much with them but there turned out to be quite a bit of work involved – as there always is.

“You listen through and think, ‘Oh they’re terrific,’ but then you start thinking, ‘If I did this, that and the other, we can make them even better and make them stand up for themselves.’ And so I had to spend quite a long time devoting myself to that project, which became a distraction from this album, but it was well worth it. I’m really proud of The Endless River.”

Wright’s passing seemed to put an exclamation point on the fact that Pink Floyd would not ever reunite. But Gilmour says that ship had long since sailed well before 2008.

“That was already long gone for me [before Wright’s passing],” he says. “After The Division Bell album and tour [in 1994] I had definitely decided that I had had enough of that. It was fantastic and a joy, something that I’m very proud of and had a lot of great times doing. But you have to move on sometimes. Having Rick Wright with me in 2006 on my solo On The Island tour, I had enough of Pink Floyd in there to make me happy. That was the most joyful tour I think I’ve ever been on. Every day was a pleasure, which is how it should be!”

Gilmour still plays plenty of Floyd material in his solo shows. He practically recoils when this is mentioned on the heels of his suggestion that he wants to look forward and not back.

“Of course!” he says, displaying a rare trace of irritation in a an otherwise gentle, genial conversation. “To say that I don’t want to be a part of being in Pink Floyd with other people, creating new things, doesn’t mean that I want to discard my past in any way. I’m very proud of it.”

Pink Floyd’s biggest rupture came in 1984, a year after the release of the fractious The Final Cut , which felt like a Waters solo album. When Waters and Gilmour both released solo albums and toured behind them, Pink Floyd seemed to be done. The title The Final Cut took on new meaning.

, which felt like a Waters solo album. When Waters and Gilmour both released solo albums and toured behind them, Pink Floyd seemed to be done. The title The Final Cut took on new meaning.

Waters took steps to dissolve the partnership, and when Gilmour and Mason pushed on, the bassist sued to stop them from recording or touring as Pink Floyd. He lost and the Waters-less Pink Floyd released Momentary Lapse Of Reason in 1987 and launched a worldwide tour. According to the 2008 book Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd

in 1987 and launched a worldwide tour. According to the 2008 book Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd , Waters dismissed the album, saying, “I think it’s facile, but a quite clever forgery … The songs are poor in general … [and] Gilmour’s lyrics are third-rate.”

, Waters dismissed the album, saying, “I think it’s facile, but a quite clever forgery … The songs are poor in general … [and] Gilmour’s lyrics are third-rate.”

Seven years later, with Wright back as a fulltime member the band released The Division Bell  , another hit album followed by another hugely successful world tour.

, another hit album followed by another hugely successful world tour.

The four classic era members – Gilmour, Waters, Mason and Wright – played together for the first time in 2005 at the Live 8 concert in London, hopes were raised that it would lead to an ongoing Pink Floyd reunion tour. The group reportedly turned down incredibly lucrative offers.

“It was never a consideration for me,” Gilmour says. “I can’t say for sure about the others, but to me it was something for a specific purpose and that was it. It was very nice and very good for me to be able to play with those guys and have that day, the time on stage together. There was a little bit of repairing of past damages done at that time, but it was not something I wanted to go back to.”

He pauses to reiterate his bottom line: “It’s been terrific. I loved Pink Floyd and I’ve had a great time playing this music for a long time but I’ve moved on now and love what I’m doing.”

The absence of Pink Floyd and the infrequency of shows by Gilmour and Waters individually has led to a thriving market in tribute bands. It’s a trend that Gilmour understands, appreciates and essentially endorses.

“Why not?” he asks, rhetorically. “Musicians have got to earn a living and there are a lot of people who want to hear the music. I’ve been very impressed with some of what I’ve heard, but there’s an essential difference between cover bands and what we did and continue to do. We play every night what we feel like playing and the cover bands tend to think that it’s important to take a performance and play precisely what we played at that particular moment on that particular day. They take it from a live performance or a record and copy it.

“I understand that concept, of course, but those records and things we played live are living, breathing moments and we occasionally capture one and put it on record. But every night is different. I don’t have to play the same solo every night. It’s a living thing and I would go insane trying to match it always. The cover bands are a bit more like playing a record. It’s not original and musically inspiring. But I still like it!”

Pink Floyd began as a highly experimental band, particularly so in the pre-Gilmour Barrett days. As the band grew bigger, they improvised less often and less aggressively. Gilmour says that this was a natural development.

“In our earliest days, the improvisation could be radical,” says “Gilmour. “That would mean that we could have some sublime moments, but there were a lot of tedious moments as well. People can look back at it with rose-tinted glasses and say that it was all great, but a lot of it really wasn’t.

“As you get older, I think you want to raise the whole level of your game and be a bit more consistently great. Some people might say that to lop off the low end you’ve got to lop off a bit of the sublime end, too, but I’m not sure I agree. I think we just started aiming higher. We never stopped improvising but the moments do become fewer and possibly less adventurous.”

Throughout their career, Pink Floyd were renowned for their great sound. Most of the band actually boycotted the record release celebration for Dark Side of the Moon, incensed that it was not being heard in a quadrophonic mix that would allow its full sonic glory to be appreciated. They took the same level of care to their live shows well before most bands paid much attention to such things – the Grateful Dead and their Wall of Sound being the exception that proves the rule.

When music ricocheted through arenas, Floyd’s concerts featured pristine sound. When shows moved to stadiums, they were again one of the first acts to master the new venues and manage to create intimate feeling shows even amidst a fair amount of pageantry – shows that looked and sounded great, with video and other visual cues that pulled the crowd in.

“We just always thought that we shouldn’t cut corners,” says Gilmour. “We always thought that we should do things the best possible way. We were at the forefront of developing the modern PA system. We had the best one that anyone had ever heard back in 1971 and ‘72.

“We would carry our own PA systems around America at a time when a lot of rooms had their own PAs built in but we didn’t think they were good enough, because you are only as good as your weakest link. If the speakers are rubbish then your music doesn’t sound anywhere near as it could. You want it to sound as good as it can. There are a lot of people who do and always have cut corners and I would suggest it’s to their long term detriment.”

This spring, Gilmour will bring his solo tour for Rattle That Lock to North America, opting to play just 10 shows in only four cities (Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto and New York).

“I’m not a young kid any more,” he says. “I’m 69 and I just don’t feel the desire to travel around dozens of cities. I think most of my audiences are much younger than me and I kind of think they can travel to me rather than me having to go them quite as much. I don’t want to do a big long tour.

“I want to really enjoy a shorter your playing in really nice places, in rooms I can control well sound-wise and really enjoy myself. That will be better for the people who come to them. I don’t want to do a long, arduous tour. I’ve done plenty of those and I’m kind of done with it.

“But,” he adds quickly, “I am certainly not playing music.”

March 5, 2017

A Tribute to Butch Trucks 3/1/17: thoughts, photos, videos.

By Eric Gettler

Last Weds. March 1, I paid tribute to Butch Trucks with a special band: my Big in China core supplemented by Andy Aledort (Dickey Betts), Peter Levin (Gregg Allman) and Junior Mack (Jaimoe).

This show meant a lot to me. March in NYC has a lot of resonance for us Allmans people. It was the most exciting month for almost 25 years and a sense of loss has lingered each of the last three years as 3/1 approaches and we’re not prepping for the Beacon. We lost not only the great shows, but the camaraderie, the pre- and after- show parties, drinks and meals. This year was that sense of loss times 1000, because Butch’s death shattered our hearts and left many of us reeling, sad and confused.

Butch was incredibly helpful in the writing and promotion of One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band and the process brought us pretty close. I have valued his daughter Elise Trucks‘ friendship for a long time. I was devastated by his death and I wanted to honor him. So I thought about who I would want in a dream band to do this and quickly decided: Andy on lead and slide, Junior on guitar and vocals, Pete on keys. I know this music really well and these three are as good as ANYONE at playing it. So I called them all and one by one they said yes, sure. We added my Big in China band, fortified it with some of Andy’s guys and special guests like Tim Woods, Ben Sparaco and the amazing Taz and set this thing up. Then the only question was, could we pull it off, and by “we” I mean “I” because I never doubted Andy, Jr or Peter. I knew I had to step it up.

By Joel Fried

Honestly, it came off better than I could have hoped, and it was very emotional for all of us to play this music together. Because of our depth of sadness for Butch’s loss. Because of our sadness about no more Allman Brothers Band. Because we all LOVE this music and it has been central to our lives. We played from the heart and for the heart and we got so much love back. I feel incredibly gratified. Proud that we pulled it off and validated in my belief that if we could do so, it would mean a lot to a lot of people.

Photo – Christian Koerwer

Thanks to everyone who came out, to Kendall Deflin, Gideon Plotnicki, Kunj Shah and Live For Live Music for doing so much to make it happen and to American Beauty NYC for hosting.

To paraphrase Jaimoe at Butch’s Macon Memorial Service: Thank you God. Thank you Butch Trucks. And thank you Allman Brothers Band.

“Dreams”

“You Don’t Love Me”

“You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go”

“Blue Sky”

“Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More”

“In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” w. Brandon “Taz” Neiderauer

“Stormy Monday”

February 12, 2017

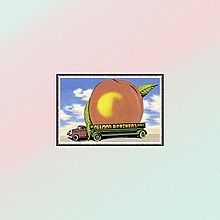

The 45th Anniversary of Eat A Peach

Today is the 45th anniversary of the release of Eat A Peach, the album that first hooked me on the Allman Brothers Band. In honor of this, I offer you this edited excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band about the making of this landmark album. You can buy the paperback by clicking the link above, or order a signed copy of hardcover or paper by clicking here.

***

After the release of At Fillmore East and before it’s gold certification, the band entered Miami’s Criteria Studios with Dowd to work on their third studio album, which they had begun the previous month by laying down the initial tracks for “Blue Sky,” Betts’ sweet, country-tinged tune, which would be his first vocal with the band.

TOM DOWD: They only had a few songs ready to track and we never wrote in the studio. That was one way we saved money on studio time.

DICKEY BETTS: I wrote “Blue Sky” for my then-wife Sandy Blue Sky, who was Native American, but once I got into the song I realized how nice it would be to keep the vernaculars — he and she — out and make it like you’re thinking of the spirit, like I was giving thanks for a beautiful day. I think that made it broader and more relatable to anyone and everyone. That was a bad marriage but it led to a good song.

BUTCH TRUCKS: Dickey wanted Gregg to sing “Blue Sky” and Duane just got all over him. He said, “Man, this is your song and it sounds like you and you need to sing it.” It was Dickey just starting to sprout his wings as a singer.

The band worked on three songs — “Blue Sky,” an instrumental track tentatively called “The Road to Calico,” which would eventually have vocals added and become “Stand Back,” and “Little Martha.” The latter, a sweet, lilting Dobro duet, was the only composition ever credited to Duane Allman.

BETTS: Duane and I played acoustics together all the time backstage and in hotel rooms and buses. Duane usually had his Dobro, I had a Martin and Berry had a Gibson Hummingbird. The three of us spent plenty of time sitting around playing blues — Duane loved Lightnin’ Hopkins and we both loved Robert Johnson and Willie McTell. We also worked out things for our own songs. “Little Martha” was not all typical of what we played — it sounded more like something I might do, really — but he had shown us pieces of it for years, so it wasn’t a shock.

ALLMAN: My brother loved playing that kind of stuff, and I have to think there would have been more music coming out of him. He put “Little Martha” together piece by piece.

BETTS: The song is played in straight E. I played the low third and Duane played the higher third. He wrote that song for his girlfriend Dixie; she’s “Martha.”

Betts’ insistence on this title is at odds with what most others believe; that “Little Martha” is named in honor of Martha Ellis, a 12-year-old girl buried in Rose Hill, with an eerie late 19th century statue atop her grave.

TRUCKS: Until that time I had always been sort of the lead drummer in the studio, but “Stand Back” was a perfect song for Jaimoe because it was this funky r&b style he’s so good at and I said, “You play the drums on this. I’m not even going to play.” Jaimoe took the lead.

JAIMOE: “Lead drums?” I don’t really call it that. What I was playing fit the song more than the kind of feel that Butch plays. It was a simple, funk thing that fit what I was doing. There’s a lot of things that maybe he shouldn’t have played on, but that kind of decision wasn’t made. There’s always a positive and a negative to everything you do, so what’s the sense of even bringing this kind of stuff up? Well, it might be interesting for people listening to us to know these things, just like Miles Davis or Elvis Presley, or anyone else people listen to and care about.

Photo – Twiggs Lyndon

NOTE: There is no easy way to summarize the next chapters of the book, or of the band’s history, but here goes. After finishing those three songs in about a week, they took a break and returned to the road, ending a short run of shows on October 17, 1971 at the Painter’s Mill Music Fair in Owings Mill, Maryland. Then, with most of the group struggling with heroin addictions, Duane, Oakley, Red Dog and Kim Payne checked into rehab in Buffalo, NY.

Duane returned to Macon on October 28, 1971 after a stopover in New York City. The next day, he was killed in a motorcycle crash. The details of the Buffalo rehab, the New York visit, the last day in Macon and the horror, shock and pain of Duane’s death are all important, and if you don’t know them well, I urge you to read up in One Way Out. For the purpose of our Eat A Peach story, let’s say that no one knew what would come next and it was equally impossible to imagine the band continuing without Duane and ending right there.

The band took a short hiatus before regrouping, gravitating back towards each other and immersion in their work. They committed to fulfilling previously scheduled dates in New York. Their first appearance without their leader was at CW Post College in Long Island on November 22, 1971; it was exactly three weeks after Duane’s funeral. In December they returned to Miami to work on the album. Our story continues there.

The band recorded four more outstanding tracks with Dowd, including “Melissa,” Betts’ instrumental “Les Brers In A Minor” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” Gregg’s defiant response to his brother’s passing.

ALLMAN: I wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” for my brother right away. It was the only thing I knew how to do right then.

TRUCKS: Of course, the music we recorded was all about Duane. Gregg wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and that was obviously about how to deal with this tragedy, but I think “Les Brers in A Minor” is about Duane just as much. We did everything we could to try and fill the gap and “Les Brers” was Dickey’s response — starting with the title, which is bad French for “less brothers.”

BETTS: When I wrote “Les Brers” everyone kept saying they had heard it before, but no one could figure out where, including me. But it’s in my solo on “Whipping Post” from one night. It was just a lick I was playing in there, and years later it showed up in a bootleg, which was kind of amazing. I mean, none of us knew where it came from until that tape surfaced years later. It just sounded familiar.

TRUCKS: We were all putting more into it, trying so hard to make it as good as it would have been with Duane. We knew our driving force, our soul, the guy that set us all on fire, wasn’t there and we had to do something for him. That really gave everybody a lot of motivation. It was incredibly emotional.

BETTS: It was difficult to suddenly have to play slide and I put in some time to get my part down for “Ain’t Wasting Time No More.” I’ve always enjoyed playing acoustic slide and would even often play it with Duane; when the two of us played acoustic blues I was often the one with the slide, but I never cared as much for playing electric slide.

The band also recorded “Melissa,” a song Gregg had written in 1967 — he says it is his first tune he ever considered a keeper after several hundred — but had never recorded.

ALLMAN: When we were finishing Eat a Peach, we needed some more songs and I knew my brother loved “Melissa.” I had never really shown it to the band. I thought it was too soft for the Allman Brothers and was sort of saving it for a solo record I figured I’d eventually do.

The double album Eat A Peach was completed with three live songs: “One Way Out” from the June 27, 1971 final concert at the Fillmore East, and two songs recording during the March At Fillmore East performances: “Trouble No More” – the Muddy Waters track that had been the first song Gregg sang with the band – and the epic, 33-minute “Mountain Jam.” The latter, which took up both sides of a vinyl album, had been an evolving staple of their performances almost since the beginning.

DOWD: When we recorded At Fillmore East, we ended up with almost a whole other album worth of good material, and we used [two] tracks on Eat A Peach. Again, there was no overdubbing.

ALLMAN: We always planned on having “Mountain Jam” on this album. That’s why you hear the first notes of the song as “Whipping Post” ends on At Fillmore East.

TRUCKS: That “Mountain Jam” is only on there because it’s the only version we had on multi-track tape and it was such a signature song of the band with Duane that we simply had to have it on a record. We played it many times so much better, but better a relatively mediocre version than nothing at all.

BETTS: That was probably the worst version of “Mountain Jam” we ever played. When we were recording live, we really were still focused on the crowd rather than the recording.

With recording done, the album had to be mixed. Dowd started the process, but the album had run over and he had other commitments, so Sandlin was called to Miami.

SANDLIN: I think Tom had to work with Crosby Still and Nash. I went down to Miami the last day Tom was still working on it, and sat with him, and he showed me what he was doing and discussed some aspects of recording. As I mixed songs like “Blue Sky,” I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there’s not going to be any more from him.

I was very proud of my work on Eat A Peach but really pissed because I did not receive credit, only a “special thanks.” It was the first platinum record I’d ever worked on and it meant a lot to me, so that felt like a slap.

TRUCKS: After we were all done and the album was being finalized, I walked into Phil’s office and they showed me the beautiful artwork, with this title on it: The Kind We Grow in Dixie. I said, “The artwork is incredible, but that title sucks!”

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

Then I hand-lettered the Allman Brothers name and photographed it with a little Kodak camera and had it developed at the drugstore, then cut the letters out and pasted them on the side of the truck, under the peach. Duane was still alive and the album had not been titled. We figured we’d go back and add that.

TRUCKS: Duane didn’t like to give simple answers so when someone asked him about the revolution, he said, “There ain’t no revolution. It’s all evolution.” Then he paused and said, “Every time I go South, I eat a peach for peace.” That stuck out to me, so I told Phil, “Call this thing Eat a Peach for Peace,” which they shortened to Eat A Peach.

It didn’t occur to me until decades later that Duane’s comment was a reference to T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” though I knew Duane was a big fan. I was reading Prufrock and came across the reference to eating a peach and was blown away. The symbolism is obvious. Prufrock was totally anal and didn’t want to do anything that would get messy and there’s nothing messier than eating a peach. Duane would have loved that metaphor.

POWELL: The cover was kind of a new approach, a soft sell, because it did not say the name of the album – and the name of the band was just in tiny letters. We left that to a sticker on the shrink-wrap. When we showed it to someone at the label, he said, “They are so hot right now, they could sell it in a brown paper bag.”

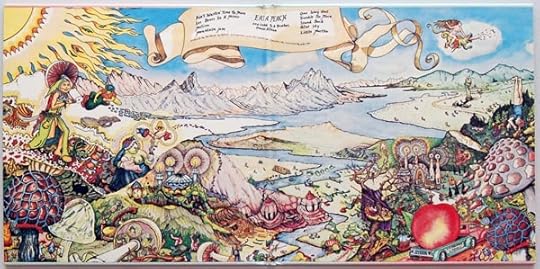

The double album opened up as a gatefold filled with another Wonder Graphics piece of art; an entire universe that seemed to promise some kind of psychedelic paradise. It told a story of happy, mystical brotherhood that was receding ever further into fantasy as the band grappled with the tragedy of Duane’s death.

POWELL: That was really a cooperative venture between Jim [Flournoy Holmes] and I, completed with almost no planning or discussion. We were working on a large piece of illustration board, on a one-to-one scale – it was the size of the actual spread – and we just started drawing, with Jim’s work primarily on the left and mine on the right. This work was profoundly influenced by [Hieronymous] Bosch.

The whole thing was done over the course of one day while we were in Vero Beach, Florida. While one of us was drawing or painting, the other was out swimming in the ocean. We swapped off this way with virtually no conversation about the drawing, just fluid tradeoffs.

February 8, 2017

Tedeschi Trucks Band announce Live DVD and album – info and videos

“A new peak in the continuing story of a great American rock & roll family band.” – From album liner notes by David Fricke

“A new peak in the continuing story of a great American rock & roll family band.” – From album liner notes by David Fricke

EDITED PRESS RELEASE: On March 17th, Tedeschi Trucks Band will release their second live album and first ever concert film, Live From The Fox Oakland. The film also features extensive behind the scenes footage, including Derek’s recent visit to Marc Maron’s garage for the WTF! Podcast (http://bit.ly/2jDCZAN), and an interview with Derek and Susan conducted by Rolling Stone critic David Fricke for SiriusXM Satellite Radio

The film also features extensive behind the scenes footage, including Derek’s recent visit to Marc Maron’s garage for the WTF! Podcast (http://bit.ly/2jDCZAN), and an interview with Derek and Susan conducted by Rolling Stone critic David Fricke for SiriusXM Satellite Radio

Filmed and recorded in a single night, September 9th, 2016, at Oakland, CA’s gorgeous Fox Theater, the concert film and audio were mixed using a vintage Neve console to achieve an exquisitely immersive sound experience, and mastering guru Bob Ludwig added his craft to the full 5.1 surround sound mix and album audio. The film was produced and directed by Jesse Lauter (Bob Dylan In The 80s: Volume One) and Grant James (Father John Misty) with Trucks continuing in his role as producer on all music elements. ‘Live From The Fox Oakland’ will be released in multiple formats including vinyl, DVD and Blu-ray

KEEP ON GROWING:

In another memorable segment, sarod master Alam Khan joins TTB onstage for the first time on their original song “These Walls.” This genre-defying moment reveals TTB’s classical Indian influences and proves the 12-piece ensemble can drop their sound down to a whisper when it serves the song.

‘LIVE FROM THE FOX OAKLAND’ FILM TRAILER

For a band that spends hundreds of days on the road a year, it was important to choose the right time for their second live album. As Trucks explains, “we’ve been wanting to properly document the progress of this band for a while and it really felt like we were hitting our stride and firing on all cylinders last fall.” Tedeschi adds, “it was special capturing the live performance from Oakland. The audience was great and the band played with passion. I am thankful we captured the band at this moment in time.”

Trucks and Tedeschi’s full commitment to making the best sounding live recording possible was evident from start to finish. “Our engineers Bobby Tis and Brian Speiser have been tweaking our recording setup on the road over the last year so we can really capture the sound of being in the room,” says Trucks. “The three of us spent countless hours in our studio after the recording to bring the tracks to life and make sure you can hear all the energy and nuances, which isn’t easy with a 12 piece band. We put a lot of work in to make sure the mixing/mastering was a notch above and I think our fans and music deserve the extra effort.”

Album Track List

1. Don’t Know What It Means

2. Keep On Growing

3. Bird On The Wire

4. Within You, Without You

5. Just As Strange

6. Crying Over You

7. These Walls (featuring Alam Khan)

8. Anyhow

9. Right On Time

10. Leavin’ Trunk

11. Don’t Drift Away

12. I Want More (Soul Sacrifice outro)

13. I Pity The Fool

14. Ali

15. Let Me Get By

Film Track List

Don’t Know What It Means

Keep On Growing

Bird On The Wire

Within You, Without You

Just As Strange

Crying Over You

Color Of The Blues

These Walls (featuring Alam Khan)

Leavin’ Trunk

I Pity The Fool

I Want More (Soul Sacrifice outro)

Let Me Get By

You Ain’t Going Nowhere

February 6, 2017

Rich Robinson, Marc Ford and Magpie Salute to play London, Chicago, San Fran

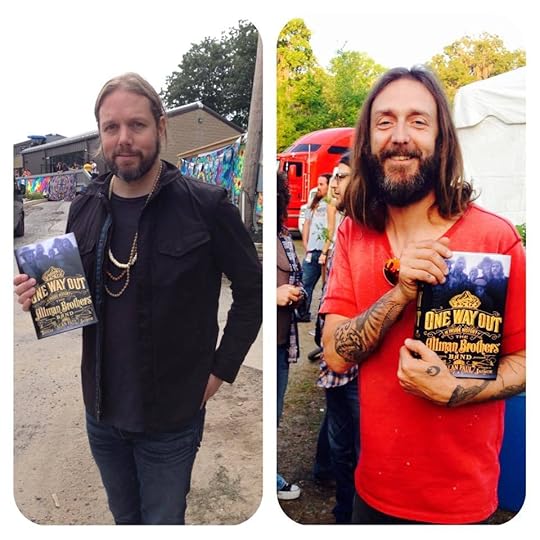

They don’t agree on much, but they know a good book when they see one…

The following is a press release from the band. Not my words or sentiments. Happy this is all happening, and wish I could have written about it already!- AP

Coming off their successful debut as a band with four back-to-back sold-out shows at the Gramercy Theatre in New York last month, THE MAGPIE SALUTE have announced concerts in London (April), Chicago (July) and San Francisco (September). The full ticket info is below.

Formed by Rich Robinson, the guitarist and co-founding member of The Black Crowes, THE MAGPIE SALUTE is an exciting new band bringing together two other key members of Crowes fame–guitarist Marc Ford and bassist Sven Pipien–alongside members of Robinson’s own band: drummer Joe Magistro and guitarist Nico Bereciartua. THE MAGPIE SALUTE also boasts a fine cast of vocalists, including lead singer John Hogg (Hookah Brown, Moke), former Crowes singer Charity White and background singers, Adrien Reju and Katrine Ottosen. THE MAGPIE SALUTE marks the reunion of the Robinson and Ford guitar team (Ford left The Black Crowes after their fourth album and 1997 Further Festival tour).

The band’s opening show at the Gramercy (January 18) began with a 12-minute filmed tribute to the late keyboard Eddie Harsch, the Black Crowes keyboardist who past away in November before he was set to perform with the band at the Gramercy shows. The tribute ends with footage of THE MAGPIE SALUTE performing at the Gramercy which you can click here to watch.

In the U.K., THE MAGPIE SALUTE will perform three shows (April 12-14) at the London venue Under The Bridge. Opening night sold-out within an hour of the tickets going on pre-sale and now only a few remain for the 4/13 and 4/14 shows.

In Chicago, the band has announced a July 28 show at Metro. Pre-sale begins Wednesday, February 8 at 10am CST with general on-sale beginning Friday, February 10 at 10am CST. Tickets can be purchased here.

On September 7, THE MAGPIE SALUTE will perform in San Francisco at TheFillmore. Pre-sale begins Wednesday, February 8 at 10am PST with general on-sale beginning Friday, February 10 at 10am PST. Tickets can be purchased here.

February 4, 2017

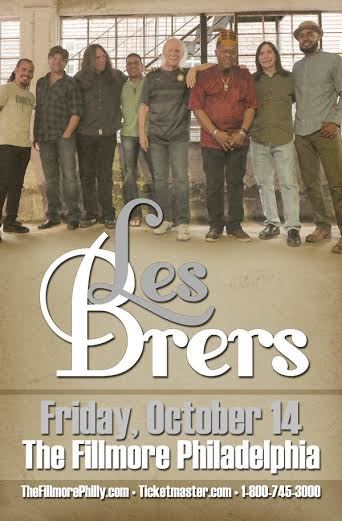

Les Brers – Philly Fillmore, 10-14-16 video and more…

Kirk West, of course.

I’ve had so many thoughts about Butch in the past couple of weeks and one thing I keep coming back to is how good Les Brers was and how few people got to see that and really understand that. It was as close as there’s been to an Allman Brothers show since October, 2014 and it was, of course, a special treat to hear Jaimoe, Butch and Marc play together again. Those of us who got to really dig into this were very lucky.

In October, I saw two shows, one near me in Montclair NJ and the next one at Philadelphia’s Fillmore. I rode the bus down there with the band and had a fantastic time BS’ing with Jaimore, Jack Pearson, Lamar Williams Jr and Oteil in the back lounge.

The show was fantastic. Packed house, with over 1,000 people there at a free show celebrating the one-year anniversary of the Fillmore. Great performance, which I mostly watched from the stage and streamed live to thousands… Afterwards, a rush of people at the merch stand… everyone signing autographs and taking pictures with the fans. It was a great, great vibe all the way around.

Back on the bus, we stopped at a great cheesesteak place down the street, loaded up, climbed back on, gorged on great Philly cheesesteaks and began the ride back home. Back to the hotel around 330, and staggered home to my bed at 4 am. A great, great night. I never thought it would be the last time I saw the band.

Now someone has posted a pro video (not pro sound alas) of the first set. I’m so happy to have this. Enjoy… and at the end Butch comes out and talks and is so so Butch. Makes it extra special.

February 3, 2017

Garth Hudson with Warren Haynes and Last Waltz 40 – I Shall Be Released and more…

Circumstances have conspired to keep me away from this run of Warren Haynes’ Last Waltz 40 tour, which is a real shame. I’ve been loving what I hear. Last night in Albany, they were joined by one of two surviving The Band members, keyboardist Garth Hudson, and it seems like it was pretty great.

Sean Roche, whom I don’t know but whose videos I’ve long enjoyed, was there and captured a bunch of songs. Here’s a few of the highlights I saw. For good measure, I added “The Night The Drove Old Dixie Down” from Boston a few nights earlier, featuring a fantastic vocal from Joan Osborne.

If you like them, click over to YouTube and watch some others.

“I Shall Be Released”

“The Weight”

“Chest Fever, with Garth organ solo”:

“The Night The Drove Old Dixie Down,” with Joan Osborne:

February 2, 2017

Frogwings 2-9-99 Complete Show RIP Butch Trucks

Well, this is a nice thing to see pop up. I was at this show at New York’s Wetlands on 2-9-99. What a great place to see this remarkable, short-lived band. There’s so much great stuff happening here. Butch, Marc, Derek, Jimmy, Oteil, Kofi … and, yeah, John Popper, who I am not such a big fan of.

Well, this is a nice thing to see pop up. I was at this show at New York’s Wetlands on 2-9-99. What a great place to see this remarkable, short-lived band. There’s so much great stuff happening here. Butch, Marc, Derek, Jimmy, Oteil, Kofi … and, yeah, John Popper, who I am not such a big fan of.

What I remember most about this night: I was crammed up close to the stage for the first set just totally blissed out. Then I went into the tiny dressing room to say hi to people and hang at the break. I was in there with Andy Aledort and Warren showed up at some point. I couldn’t really make my way back out to a good spot when the second set started so I stayed close to the dressing room to just listen and enjoy, but I was wedged into a corner with my head right by the Leslie cabinet blaring Popper’s harmonica. Two of my favorite guitar players in the world, all this greatness happening and I had that harp alone blasting me in the face. I was pissed. Andy and I joked about it.

Thanks to whomever made this available now. The band is one of Butch Trucks’ unsung legacy points. Cool fact in One Way Out from Warren about Butch’s rationale for starting Frogwings. Go look it up. I made a mistake not including the Frogwings record in the One Way Out discography. Sorry about that Butch!

Info from YouTube post:Frogwings

February 9, 1999

Wetlands Preserve

New York, NY

Face First Production

Taped by Tom P

Captured by Ray B

Synch & Author by Anon

Video: Single Cam } Hi8 Master } Sony Sony DCR-TRV480 } Firewire } HD } Vegas 6 (.avi) } MPEG2 } Architect 5 } DVD5 & DVD9

[NTSC, 4:3, 8.0 Mbs, 720X480, 29.97 fps]

Audio: SBD } PCM-M1 } DA-P1 } Audiofile 24/96 } Audacity } Fission } xACT } FLAC

Taped by Dave Nolan

[LPCM, 1.5 Mbs, 16 Bit, 48 khz]

DVD 1 Set 1

Kickin’ J.S. Bach

Wetlands Shuffle

Hurdy Gurdy Fandango

Feel For You

Pattern

00:46:22

DVD 2 Set 2

Cut Mullet

Among Your Pillows

Just One

Ganja

Deviant Dreams

Nomad

Band Intros

Hot Lanta *

01:26:56

John Popper – Harmonica

Jimmy Herring – Guitar

Derek Trucks – Guitar

Kofi Burbridge – Keyboards, Flute

Oteil Burbridge – Bass

Butch Trucks – Drums

Marc Quinones – Percussion

Warren Haynes – Guitar *

January 31, 2017

Derek and Doyle Take Shanghai with Eric Clapton

Photo – Doyle Bramhall II

In honor of the release of Eric Clapton’s new double-CD Live In San Diego (with Special Guest JJ Cale), I present the following article, which I wrote for Guitar World. Hanging out with Derek and Doyle in Shanghai was so much fun, as you can well imagine.

The show itself was spectacular and it actually inspired me to start what became Woodie Alan when I returned to Beijing – so a very monumental weekend for me. The tracks with Cale are getting the attention and deservedly so, but I’m thrilled that this edition of the Clapton band has a performance captured for well-mixed, official release.

••

Derek Trucks stands in the middle of a narrow Shanghai street, camera pressed to his eye. He is aiming his lens towards a group of Chinese men and women off to the side, behind the stalls, engaged in a game of mahjong, while several kids play on the ground around their feet. Doyle Bramhall II is a few feet back, eying a stall filled with antique radios, watches and phonographs, a huge camera dangling around his neck.

In a few hours, the two guitarists will climb onto Shanghai’s Grand Stage, joining Eric Clapton as the music legend makes his Chinese debut. It is their latest stop on a year-long world tour, which kicked off last May and has taken them through Europe, North America, Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Trucks and Bramhall have had plenty of chances to get out and see the sites, capturing it all with their high-end Leica cameras.

Bramhall has had a longtime interesting in photography (as the photos accompanying this story attest), but Trucks has only recently caught the bug. Shutterbug Clapton took his young protégé to a Leica store in Germany and fairly demanded he make a purchase.

Bramhall has had a longtime interesting in photography (as the photos accompanying this story attest), but Trucks has only recently caught the bug. Shutterbug Clapton took his young protégé to a Leica store in Germany and fairly demanded he make a purchase.

“I figure with the amount of things we were seeing on this tour, it would be good to have a nice camera to document a year in the life of the Eric Clapton band,” says Trucks. “It’s all been pretty amazing.”

Even the unflappable Trucks is impressed with this gig. Now 27, he’s been gigging since he was 11, fronting his own band since he was 15, a member of the Allman Brothers Band since he was 20. But touring the world with a certified rock superstar is different. They fly around Asia first class and jet around Europe and North America on a private plane, staying in five-star hotels everywhere. With Trucks’ future collaborations with Clapton up in the air, you might think he would have a hard time leaving this life behind. You would be wrong.

“Filling up my passport excites me,” says Trucks, over a lunch of soup dumplings and fried noodles in a restaurant near the market. “But touring with three bands on three completely different levels at the same time has made me realize just how much it’s all the same. The hotel may be different but you deal with the same bullshit and you get the same payoff – going on stage and playing music for people.”

Trucks left the Clapton tour with 12 dates to go join the Allmans’ annual run at New York Beacon’s Theatre. This summer, he will focus on touring with the ABB and his own band, who have largely been waiting for him to return from the Clapton jaunts. He first joined up with Clapton in the studio for Road to Escondido, the guitarist’s collaboration with JJ Cale, on the recommendation of Bramhall, who has worked with Clapton since 2000.

Photo – Doyle Bramhall II

“Eric said he wanted a third guitar player, which I thought was unnecessary,” recalls Bramhall. “He explained that he wanted to put together a band to play some different music, including a lot of Derek and the Dominos. There are a lot of guitar parts on that album and he felt he hadn’t really been able to play the material correctly all these years. I really thought Derek was the only guy who could do justice to that spot.”

Clapton’s also hired a new rhythm section, drummer Steve Jordan and bassist Willie Weeks, who form a hard-hitting, dynamic core. The band pushes Clapton hard, unlike many of his previous groups, whose prime function seemed to be setting an unthreatening musical bed upon which Clapton could lay his guitar and vocals. The current group feels very much like a real band, with give and take, pushing and prodding.

In Shanghai, they came out and launched into five straight Derek and the Dominos songs, including an extended, gorgeous take on Jim Hendrix’s “Little Wing” that spotlighted all three guitarists. Clapton, on top of his game, relentlessly drove the group from one song to another, with propulsive and energetic rhythm and lead playing. He barely spoke, which was confusing to Asian crowds used to much more pandering and interaction from its performers.

“Eric is turning his back to the audience much more than he has in the past,” notes Bramhall. “It is not out of indifference but because he wants to hear everything the band is doing and really interact with everyone. He’s feeling it. He’s in a zone.”

Photo – Doyle Bramhall II

The song selection was heavenly for us guitar freaks, but it left much of the crowd perplexed. Many would have preferred to hear “I Shot the Sheriff” or “Pretending,” hit songs that have been dropped as the tour progressed. The crowd finally surged to its feet when the band closed with a stirring “Layla,” more similar to the original version than anything Clapton has played in years. Trucks replicated Duane Allman’s soaring slide lines while Bramhall held down the rhythm and fills, freeing Clapton to focus on leads. The night ended with an encore of “Crossroads,” that also drew a wild response.

“Eric had never been to China before and he hasn’t hit some of the other places in 10-15 years,” Trucks says. “Those people expect to hear hits and they may well not know any of his music except [the greatest hits collection] Timepieces or Unplugged. They respond much more to any song on either of those albums.”

Adds Bramhall, “It seemed like most of Asia pretty much sat on their hands the whole show.”

Trucks notes that he was surprised to find similarly seated and mellow crowds through much of Europe. “Playing all these places has given me a new appreciation for American crowds,” he says. “It’s really the best place to play this type of music in terms of feedback and feeling the crowd is with you from the very first moment, which really helps you give a little more.”

After the show. Bramhall and Trucks headed out for a night on the town of one of the world’s most pulsing cities. They first hit a tiny music club. Expecting a quiet scene, they walked into a small, cramped room packed with young Chinese fans who had attended the show and greeted them with a standing ovation and flashing cameras. The excited Chinese band launched into “Sweet Home Alabama” followed by a steady stream of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Clapton and Allman Brothers songs.

The two guitarists signed autographs for virtually every person in the place. Overwhelmed, they left after about 20 minutes and found a cozy little club where a flaming lounge singer named Coco performed Chinese torch tunes. Trucks proclaimed it the best music he’s discovered on the road, before pushing down the street to the Cotton Club, where a blues band played. The scene was mellow, the group thrilled to welcome the young guitarists to their stage, where each played a song. It was almost sunrise when they crawled into a cab to take them back to the Four Seasons hotel.

Trucks and Bramhall were tired but feeling good, happy to have once again busted out of the grind to explore their surroundings and secure in the knowledge that they had an off day before flying to Seoul, Korea.

“I spent a lot more time sitting in my hotel room the last time I toured with Eric,” Bramhall recalled. “Then we added this young slide guitarist who likes to go out and see and do everything. It’s been fun.”

Trucks laughs and shrugs. “I want to see it all,” he says. “Who knows when an opportunity like this will present itself again.”