Alan Paul's Blog, page 13

May 24, 2017

Lynyrd Skynyrd Live from Ardent Studio, 1973 – Story behind Freebird

So I stumbled across this really cool video of Lynyrd Skynyrd live in Ardent Studios, 1973. I wanted to share it with you and also my little story below about the origins of “Free Bird.” I was a talking head in the documentary Lynyrd Skynyrd – Gone With The Wind , which many have seen on AXS TV.

, which many have seen on AXS TV.

Lynyrd Skynyrd Live from Ardent Studio, 1973

And now I present you with the story behind the writing and recording of one of rock’s most iconic songs, “FREE BIRD” Originally released on (Pronounced ‘Leh-‘Nérd ‘Skin-‘Nérd) (MCA, 1973).

(MCA, 1973).

Guitarist Allen Collins came up with the music to “Free Bird” very early in the band’s songwriting process. But while everyone recognized the grace of the chord progression, Ronnie Van Zant could not come up with a suitable vocal melody.

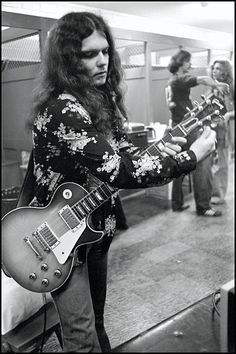

Recalls Gary Rossington, “Allen had the chords for the beginning, pretty part for two full years and we kept asking Ronnie to write something and he kept telling us to forget it; he said there were too many chords so he couldn’t find a melody. He thought that he had to change with every chord. Then one day we were at rehearsal and Allen started playing those chords again, and Ronnie said, ‘Those are pretty. Play them again.’ He said, ‘I got it,’ and wrote the lyrics in three or four minutes—the whole damned thing!

Like “Stairway to Heaven,” one of its chief competitors for the unofficial title of rock’s most epic song, “Free Bird” starts out as a ballad before becoming a solo-fueled rocker. That was not by design, recalls Rossington: “When we started playing it in clubs, it was just the slow part. Ronnie said, ‘Why don’t you do something at the end of that so I can take a break for a few minutes.’ I came up with those three chords at the end and Allen and I traded solos and Ronnie kept telling us to make it longer; we were playing three or four sets a night, and he was looking to fill it up and get a break.”

Gary Rossington

The structure of “Free Bird” was set, but it was still lacking one final element; the elegant piano intro, which was written by then-roadie Billy Powell. “One of our roadies told us we should check out this piano part that another roadie had written as an intro for the song,” says Rossington. “We did–and Billy went from being a roadie to a member right then.”

The original album version of the song clocked in at almost 10 minutes and according to Rossington and Ed King, MCA objected to putting such a long song on the band’s debut album. A 3:30 radio edit was cut and the single, at 4:10, became a Top 20 hit. “MCA said we couldn’t put a 10-minute song on an album, because nobody would play it,” recalls King. “Of course, that was the song everyone gravitated towards!”

On Skynyrd’s first live album, 1976’s One More From the Road Van Zant can be heard asking the crowd, “What song is it you wanna hear?” The overwhelming response leads into the 14-minute version of the song that became iconic. Though Van Zant often dedicated “Free Bird” to Duane Allman, contrary to urban legend, it was not written for him.

Van Zant can be heard asking the crowd, “What song is it you wanna hear?” The overwhelming response leads into the 14-minute version of the song that became iconic. Though Van Zant often dedicated “Free Bird” to Duane Allman, contrary to urban legend, it was not written for him.

May 16, 2017

Check out first single from upcoming Chris Robinson Brotherhood album

I’ve been listening a lot to the upcoming Chris Robinson Brotherhood album Barefoot in the Head as I prepare to interview Chris at 530 this evening and it’s quite good. You can check out the first single “Behold the Seer” right here. And you can tune in to my interview with Chris and his acoustic performance with Neal Casal live at 530 EST TODAY, May 16, right here on the Guitar World YouTube Channel.

as I prepare to interview Chris at 530 this evening and it’s quite good. You can check out the first single “Behold the Seer” right here. And you can tune in to my interview with Chris and his acoustic performance with Neal Casal live at 530 EST TODAY, May 16, right here on the Guitar World YouTube Channel.

May 7, 2017

An interview with Bill Kreutzmann

On the occasion of his birthday….

Give the Drummer Some

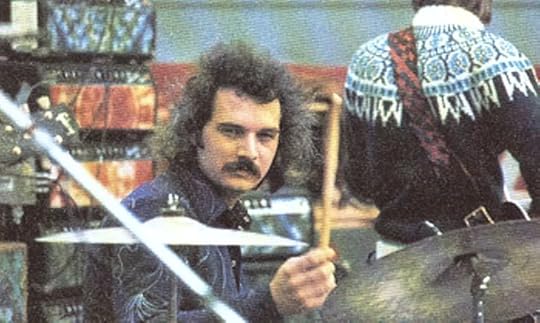

As he prepared to release his memoir, Deal, Bill Kreutzmann reflected on the joy and frustrations of life in the Grateful Dead, working with Jerry Garcia – and what Phil Lesh had against John Belushi. Going deep with the drummer.

A small portion of this interview ran in The Wall Street Journal on May 1, 2015. The rest was published only in my Kindle Single Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead.

It’s been 50 years since the Grateful Dead formed in Palo Alto, 20 years since Jerry Garcia died, and five years since the band’s four surviving members last played together. Now, as the quartet prepares for what all say will be their last shows ever, the band’s musical rock Bill Kreutzmann is coming out with a memoir that captures his honest view of the inner workings of an anarchic band that became an unlikely American institution.

Though he was one of two drummers, Kreutzmann was the Dead’s musical rock, his steady beat keeping even their most tipsy jams from falling off the rails.

“Bill was the pulse and rhythm of the Grateful Dead, the fundamental propulsion,” says Dennis McNally, who was the group’s publicist for its final 11 years and is the author of the band biography, A Long Strange Trip. “He’s the guy who maintained the drive no matter what.”

In Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams, and Drugs with the Grateful Dead , Kreutzmann and co-author Benjy Eisen unflinchingly chronicle the Dead’s formation, its improbable, zigzagging rise to become rock’s top-grossing live band, and its many low points. The latter include deaths, drug addictions, falling outs and personal failings that led to a string of broken marriages.

, Kreutzmann and co-author Benjy Eisen unflinchingly chronicle the Dead’s formation, its improbable, zigzagging rise to become rock’s top-grossing live band, and its many low points. The latter include deaths, drug addictions, falling outs and personal failings that led to a string of broken marriages.

“As ridiculous as some of those stories sound, they all happened,” Kreutzmann says, leaning forward in an overstuffed modern chair in a Philadelphia hotel suite, the Liberty Bell National Park visible through large windows behind him.

The tales in Deal include partying with John Belushi; riding camels through the Egyptian desert to a Bedouin musical jam; drawing Secret Service wrath for setting off fireworks in presidential candidate George McGovern’s hotel; blowing up abandoned cars; drunkenly racing Alfa Romeos through the San Francisco streets; and behind-the-scenes reports on Woodstock and Altamont. Through it all, Kreutzmann and most of his bandmates gobbled LSD like baby aspirin.

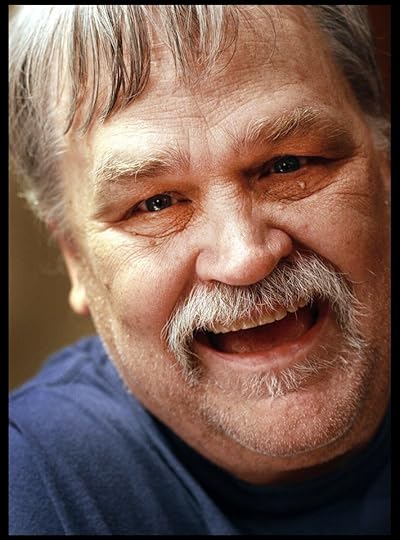

Today, Kreutzmann is tan and lean, with thinning gray hair sprouting at improbable angles, a neatly trimmed goatee and almost invisible frameless glasses. The 68-year-old drummer lives on an organic farm in Kauai, Hawaii, with his fifth wife, Aimee. He is playing at a high level heading into the five Fare Thee Well shows in Santa Clara, California (June 27-28) and Chicago’s Soldier Field (July 3-5). His new band, Billy and the Kids, displays the kind of loose-limbed improvisational sense that marked the Dead’s finest moments.

“Yesterday at rehearsal, I had two transcendental musical experiences of the type I thought were behind me at my age,” Kreutzmann says with a smile. “Bullshit! can happen at any age if you’re playing the right music with the right people.”

Kids’ bassist Reed Mathis has been amazed watching how Kreutzmann operates. “Bill wants true group improvisation,” says Mathis. “We will get to sections of a song where we eject from it completely and begin composing, which is what I love about the Grateful Dead, and I think Bill is carrying on that legacy more truly than anyone else.

“With Phil, for instance, it’s very clear who’s in charge. That’s just his way. Bill doesn’t want anything like that. He wants an authentic group experience, for us to play as his equals. I’ve realized that the more I speak my mind on my instrument, the more he brightens up, the more he plays.”

Hours after our interview, during soundcheck at the Ardmore Music Hall, the band is ripping through the Dead’s “Eyes Of The World” when Kreutzmann abruptly stops playing. He jumps up, exclaiming, “We’re fucking good!”

With a smile, he ambles over to the bar for a glass of water. “I’m playing music with people who love to play music,” he says, with a faraway look in his eyes. “I’m a very happy man.”

You write that when you took acid for the first time, you knew your life would be changed forever. Why?

BILL KREUTZMANN: Because my dreams were coming true. I always knew that there was more out there than met the eye, or that I was being taught in school or by my parents. Then I took acid and thought, “Ah, the key!” Taking acid together was the best suggestion that was made to the Grateful Dead in the early days. Pigpen (Ron McKernan) was the only who wouldn’t do it. The rest of us took it and had a great time.

I didn’t even know what it was, but I had the most wonderful time. The first trip was with the whole band and Robert Hunter, who I spent most of my time with. What a wonderful man. Isn’t it lucky that we found him?

And it wasn’t just taking the drug, right? The band really gelled by playing at the acid tests.

The acid test was a place where you could take acid – or not – and play music – or not. There were definitely no rules. No one was judging you about if you looked right or were playing a song right. You could be a total free spirit and that encouraged us to experiment and to just play. It always worked for people who were high on acid. And we were fortunate to be getting the good stuff and to all be in sync because we were taking the exact same drug.

We originally got Sandoz [LSD from the Sandoz lab in Switzerland, where it was first created]. There were these little red capsules and you hold them up to the light and see this little tiny speck of dust; a microgram is really a very little amount, except in LSD. We all had Sandoz, and then that stopped. And then Owsley (Stanley) came into our lives and was making stuff that was the equivalent, and we had plenty of that for a long time.

And beyond the drugs, Owsley was sort of your patron.

Not sort of; he was our patron! He bought us clothes and food. We didn’t have to have day jobs. It was totally important because none of us had any money. One time we were living in Olompali and my mother sent me a check for $15 for my birthday. We went and bought as much spaghetti as we could so we could eat for two days. We were like that at the beginning. 15 bucks!

By Jay Blakesberg

Characters like (Neal) Cassady and (Ken) Kesey became hugely important to the band’s development and…

They were larger than life figures. Neal Cassady and I became really good friends. I loved that guy. I’m attracted to people who are out of the ordinary. When someone says, “Oh, that guy’s a hard case,” I immediately want to find out what makes him so hard. I want to learn about that. So Neal was like a giant library of interest. He was a far out guy.

Have you ever felt responsible for leading people down the path to drugs?

No. I feel compassion for people who have a hard time, but I don’t feel responsible, because I’ve never once told anyone to do drugs. I cannot say that taking acid was good for everyone, because obviously it was not. People had bad experiences, but for those for whom it was good, it could be very good. We’re talking about Silicon Valley and giants like Steve Jobs. You can see by looking at Apple and Microsoft which one took acid.

You write that when Jerry’s opiate problem became obvious, you all wanted to play with him so much that you turned a blind eye. Blessed with hindsight, could you have done more?

It’s not that we didn’t try to do anything. We attempted interventions, but he saw a setup for what it was. And he would go to [rehab] places, but he was smarter than the therapists and could outtalk them all. I think 12-step is a great program, but he would have nothing to do with it, firmly believing that a person had the right to do whatever he liked as long as it didn’t hurt other people. But hurt where? Hurt how? Emotional pain can be much more painful than physical pain.

And your pain is still evident.

We just had no luck with getting him to leave heroin. The drug owned him and that’s really sad. I was never mad that he was a heroin addict. I felt compassion and deep sorrow, which I could sometimes hear in his playing. He would come out alone after Drums and Space (the band’s famous improvisational segments), after Mickey (Hart) and I had done our thing and filled the night with crazy sounds, and play the most forlorn, lonesome-sounding solos. It was the one time where I could really hear inside him, and it was a great, deep sadness.

Why did you feel like you couldn’t hear inside him at other times?

He would never talk about his personal life. I knew things about him, of course, that he watched his father drown in a river, for instance, which is a horrible thing for anyone to witness, much less a nine-year-old kid. He didn’t talk about that stuff. He wasn’t open like that to me.

You say several times that the Grateful Dead’s lack of communication was perhaps reflective of men of your generation.

Yes. My wife really believes that. I’ve pondered it quite a bit and I’m not sure. I was actually always someone who was comfortable talking about my feelings and emotions, but the Grateful Dead was not conducive to that. In the beginning we were, but it faded more and more.

The Grateful Dead was very much a band, but you’re quite open about Jerry’s importance.

He was so charismatic, just bigger than life, and the first time I saw him play, with Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, I thought, “I’ll follow this guy forever.” He was almost a father figure, but more like an older, wiser, very warm brother. That was the feeling, and he had an unlimited amount of love that he could offer. There was this very open feeling about him that was really cool. Jerry was also my best and most complete music teacher.

The similarities and differences between Jerry and Duane Allman are very interesting. Duane was not shy about telling people what to do.

Right on, and Jerry did not like that.

Right, but they both had this thing where people wanted to please them unconditionally and followed them, without them ever having to be asked.

Yes! I don’t know how to describe it, but there’s a spark in some people that you can’t deny. It’s there and it’s palpable but it’s not always easy to put into words. The word love isn’t even complete enough. And Jerry was my greatest musical teacher. I was a kid when we met and knew nothing. He literally said, “These are changes.”

And you write that Phil was your life leader, that you wanted to be like him as a person. Can you explain that?

Phil was seriously my older brother, and I looked up to him totally. It’s one of those charisma things again. He just had an attraction. He had stuff to teach me or tell me about. It was how he carried himself and conducted himself, but mostly about music. He turned me on to John Coltrane when I was 17. I never heard drumming like Elvin Jones, and I thought, “God, that’s legal?” I meant by the laws of physics! He turned me on to so much good music and opened my mind. Hearing Coltrane and taking acid in the same couple of years was like… how lucky can you get?

You learned from all your bandmates; when Mickey joined, he taught you a lot about rudiments.

Yes. He was a rudimentary champion, beating his dad who had won the year before. And that’s a hard-ass thing to do. You have to stand in front of a snare drum alone and play a three-minute piece that you have composed using all of the rudiments.

It speaks volumes about how some fans viewed the Dead that you feel the need to write, “We were not a cult and Jerry was not the messiah.”

I never wanted people to think that we were better than them. We were good musicians who were like-minded and who found each other in the right time and place. That’s all fortunate.

When I first started playing drums, my father, who went to Stanford, said, “You can’t be a drummer, Billy. You’ll never earn any money.” That wasn’t my goal, but he really thought musicians were like the help, who had to come in through the back door, and he didn’t want that for his son. Then one day he showed up at a show at Stanford wearing a Grateful Dad shirt and I went, “Yay, dad.”

Did people looking at him as a messiah become an increasing burden on Jerry?

Oh, yeah. The other side of being famous is you can’t just walk down the street and be like anybody and that’s a drag. I could put a hat on after a show, pull it down and walk by people. Jerry was a lot more visible. He always did great stuff, for my money; I mean, real early on if someone was having a hard time on acid, he would talk him or her down for the rest of the night. That became impossible, because the line to see him snaked out the door.

Did you and Mickey work stuff out or just sit and play?

Oh, no. No. [laughs] It looked that easy, huh? We worked stuff out. In the beginning, I actually played with him playing marches just for my hands and stuff. That was part of my education from him.

After all the practice, once you were up on stage, were you playing parts, or were you listening to him and playing off what he did?

Both. If he got on the low tones, big drums, I’d get on the higher tones and we’d have conversations, which I loved.

The closest comparison is the Allman Brothers, but…

There’s really no comparison. I love the Allman Brothers – and I love you, Jaimoe! – but there’s no similarity other than having two drummers. And there hasn’t been anyone that really used two drummers like Mickey and I did, which is that four-limbed beast thing.

Other bands have the drummers play the same thing, which…

… is pointless!

It can create more power but no more breadth and depth.

And it’s not really creating more power. Turn the drums up louder if that’s what you want. I have some strong feelings about double drumming. By the way, Jaimoe is one of the greatest drummers ever.

Your co-author Benjy Eisen is now your manager. I’ve never heard of anything like that. How did it happen?

When you work closely with someone for three years you learn one another’s nuances. And nothing ever came up that spoiled my feeling about him. I saw how hard he’ll hustle and the great ideas he comes up with, so one day I said, “You want to be a manager?” and he said, “Yeah.” And here we are.

Over the years, the Grateful Dead had issues with a lot of managers.

Yeah, just different things would come up. Like the time in France where we had to literally lift the promoter up because he wouldn’t pay us – me and the biggest equipment guy… and he had just tons of francs in his pockets. He was stuffed like a scarecrow with bills. Then I had to let the manager go. I just said, “I’m not supposed to do that. That’s not my job.” And anyhow, this heavy-handed shit is not the Grateful Dead.

But were you guys just unmanageable? It’s got be hard to manage a gaggle of proud iconoclasts.

[laughs] That’s a great question and a fair point, but I don’t think we were hard to manage. From where I stood, they just didn’t have a handle on it. At the end of the Grateful Dead, Cameron Sears was our manager and he was great.

Most of the odd time signatures and complicated musical passages came from Bob and Phil, not Jerry.

The time songs. For sure. That’s right. And?

Well, you say in the book that you often didn’t like playing their songs as much because they didn’t feel as intuitive.

That is particularly true of Phil’s songs. Phil’s songs were definitely mind songs. Bobby’s songs were more intuitive.

I’m wondering if you just don’t like the odd time signatures.

No, no. I do. I just loved the Jerry songs more. He brought them in and he knew what he wanted, so all of us could find our parts quickly and easily and intuitively. And Jerry was an incredible songwriter; he could look at a lyric sheet and say, “This chord will perfectly match that word” – and he’d always be right! Bobby’s songs were always much rougher sketches that would take more effort for us all to fill in.

For instance, Bobby came and showed me “Estimated Prophet” at a rehearsal. And he had it going, “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7…1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7…” I said, “Bobby, that’s no groove. That’s not working.” I went home on a rainy night and stood in front of my fireplace by myself, rocking my body back and forth and counting and thinking. And I went, “Wow. Why don’t we make it half time and make two bars of seven into a 14? So it’s 7 doublets and you come down on an even number!” So we play sevens in bars of two; phrasing it that way is much more musical. That’s how I gave “Estimated Prophet” groove. [sings the beat] The half time is the end of 4, which takes you to a new 7.

Was Phil less open to interpreting his songs because he presented them as compositions?

Um…. They were just really hard to interpret. I about busted my ass trying to find good things to play on some of them. That’s not all of his songs – just towards the end. There are others that were much more fun to play.

Is it true that at one point Pigpen and Bobby were fired but just kept coming?

Yeah, but that’s been covered and written about so much. And I never got into those committees about firing people. I honestly never got into taking sides. I was like, “What is this? Aren’t we musicians?” Jerry was like that, too. We’d come along at the end of the meetings and say, “Oh, ok.”

We had a meeting about firing Bobby once and nobody even brought it up. Not even the management. [laughs] And that’s the Grateful Dead. We need to find a new word for waffling, because that’s far too mild. It was a double-decker waffle!

Phil seems to have been the one pushing this. What was his issue?

He had something up his sleeve. I don’t really remember specifically what the issue was because it didn’t have that much importance to me. I care about the music and what people are doing on stage.

And you say that (keyboardist) Tom Constanten couldn’t really cut it on stage.

He had some kind of stage fright. I could never understand that. He would play brilliantly in rehearsal and we’d go, “Yeah, right on, man.” Then we’d get on stage and nothing; it was, “Yikes. Come on. Where are you now? We need to hear from you.”

Of course you had a lot of keyboardists.

Yeah, that was the hot seat. Or maybe I should say cold seat.

it seemed like once Keith (Godchaux) joined, you and he and Jerry would really lock into grooves.

Yeah, that was the band. We could have been a jazz band. We could have been lots of things. Jerry called me one day and said, “Billy, come down to the studio. I’ve got this guy you’ve got to hear.” He couldn’t get ahold of Bobby and Phil, but I came down right away. Jerry and I tried to fool Keith as much as we could, throwing him every curveball we could think of, and he was all over it. There was nothing we could play he wasn’t on top of.

He was a complementary player, weaving in between us all and making everything sound better. And he didn’t make the mistake that a lot of pianists did of copying Jerry’s line, shadowing him. Jerry hated that, man. That was one time you’d see him really mad: “Don’t play what I just did!” Vince (Welnick) did that more than was necessary – which is not at all.

Why did the band refuse the McGovern campaign’s request for an endorsement in 72?

We were truly apolitical. We backed Obama in ’08 and Jerry would have vetoed that had he been alive, because he put all politicians in the same bag; some are more tolerable than others, but they’re still politicians.

You were not happy when Mickey first left the band and you had to become the only drummer.

Yeah, it was kind of empty-sounding for a couple of gigs.

Do you think the time alone spurred your development as a drummer?

It totally did. I was ready to be my own drummer. I used all the stuff I learned from him and just kept drumming. Drums and Space was way less, of course. I just did some drum solos. But the band played great. The ’72 tour of Europe was wonderful and you can hear that. It’s a nice steady record. It’s grooving.

It seems like you were coming into your own as a drummer. Did you need to be forced into that situation for that to happen?

I agree, but that wasn’t my motivation. My motivation was Mickey was going through a really hard time then. We tried to play and he was just out of it. All that tightness we had learned before wasn’t there. It just wouldn’t work. Playing with two drummers, it’s either really on or really off. And it had gotten off.

When he first came back, you were not happy about it. Did you just feel, “I’ve been playing my ass off and the band sounds great. Why are we messing with it?”

A little bit like that, yes. I just didn’t think it was necessary. I pretended to be ok, but I thought it sounded horrible. It wasn’t working and it took a lot of rehearsing to get it sounding better.

But listening to me would have been the world’s biggest mistake; so much good music was still to come with Mickey back. I’m not always right! These are just the emotions I had at the time and being honest about them.

How long did it take you to start feeling good again?

It probably took a while. I’m going to tell you something: two or three years can go by and I feel like it was a week. I really have no length of time sense. It’s confounding to people, but if we didn’t have these devices that remembered things for us, I would be fucked. [laughs]

It is ironic to hear you say that you have no sense of time.

As a drummer, yes. [laughs] I have a great feel of time. That’s different.

You write about 5/7/77 as one of the best shows in the band’s career. That was a great era…

Right on. Just after Mickey returned!

…and right after you recorded Terrapin Station with an outside producer forcing you to buckle down and tighten up. Do you think it paid off?

It did pay off on the album, but I’m not sure about in the way that you mean, on stage, because in recording sessions you’re not really playing ensemble music. It’s not like being on stage where the whole band is out there cooking with full-on vocals.

And that recording was aggravating – especially the song “Terrapin Station,” which is not a simple drum part. Mickey and I had not come to agreement and it was dragging on and on. I was kind of upset and I finally said, “Mickey, come in my room. Let me show you how this song goes. We’ve got to play the right parts here or we’ll be in here for another month and I’ve had it with LA.

I just went, “This part works really well here. This part works really well there… “ We learned it like that, in sections, and went in the next night and recorded it.

Things were getting a bit torn and frayed both inside the band and in society in 1970 and you guys came out with the more stripped down Workingman’s Dead, then American Beauty. Do you think that was a reaction to and reflection of the times?

I think all music played at any given time is a reflection of what is going on in that person’s life, so yeah. We are the kind of musicians who play how we feel. We were just totally gung ho going for it in terms of music at that time. Totally focused and locked in together.

And a big change between was those two albums was Crosby, Stills and Nash coming in and saying, “Hey, you guys, this is how you do parts. This is how you do harmony.” It changed the ballgame entirely.

Incredible. People associate the Grateful Dead with peace and love but there are a lot of guns…

:… in my book, right? Yes. Well, we never brought that attitude on stage. That was just boys having fun out in the backwoods. No one got hurt, thank God, and rather miraculously.

It’s amazing that you guys never did any real jail time.

Yes. I did 10 days once, for growing what were probably all male marijuana plants. I didn’t know what I was doing, which is not really a defense. Those 10 days weren’t so bad. I walked in and some guy handed me a pill, smack or something I didn’t really do, and I just popped it and went to sleep for two days. It went by very fast and I didn’t give a shit. There was a guy in there who knew me and liked the band, so he passed me down burgers at 3 in the morning when I was starving.

You said that when Jerry was arrested in ’85 the judge was a Deadhead and went easy on him. Do you think at some point he would have benefited from not being treated that way?

Yes. I totally agree with what you’re saying. The addict will never voluntarily tell you they need help, and they are never going to be voluntarily arrested.

I had my hopes up for Jerry big time when he went to the Betty Ford Center, but he only stayed two weeks and it’s a fact of medicine that your body takes a minimum of 28 days to develop a new scene. And for someone who’s been using for a long time and heavily, 28 days is nothing. It’s a day. You have to stay away for at least six months. And then you have to really work with someone, a therapist of some sort, to make it work.

You write that you think Jerry was thinking of putting the Dead on hiatus again.

We actually talked about that in ’93 but the business had gotten to be so big that we had to keep playing or we’d financially crumble.

You felt an obligation to the empire and to keeping everyone employed?

Yes. That’s the sad thing; I did. The only way we could have helped Jerry is if we would have stopped being the Grateful Dead, just refused to play. But he would have just had other musicians come in. It wouldn’t have mattered. It wouldn’t have been the Grateful Dead, but nothing would make Jerry stop playing music – or using drugs.

You managed to walk that line all these years.

I don’t seem too crazed. I somehow know how to handle this shit.

I always felt like I was walking on the edge of a really sharp sword. It wasn’t cutting me, but if I went too far this way, ooh, man! If I went too far that way, it was over. I tried to stay right there in the middle on the edge, where I still felt pretty healthy.

John Belushi was another nutball friend of yours.

Oh, yeah! I don’t call him a nutball. I call him a wonderful, spiritual human being. I loved that guy so much. I was driving when I heard the news of him dying on the radio and I almost wrecked. It just took the wind right out of me because we were really close.

We were both as loony as each other and it was great. He was actually a drummer before he became known as a comedian. I used to joke about him practicing and he showed me his Samurai sword at his house in LA, darn it. He’d come to a show and sit down behind me and make one of those faces and it would just make your night. The warmth and energy and intensity coming off of him were tremendous.

And he crashed your stage one night at the Capitol in New Jersey.

He did. That was the farthest out, coolest, funniest thing. That big guy did a cartwheel waving a flag to “US Blues” and landed in front of the one empty microphone and sang the chorus in perfect time.

This was after Phil and Jerry didn’t approve of him coming on stage?

Jerry did! I asked Phil first because he was always the one I knew would be most strict about anything, so I figured I need to run it by him before it goes anywhere else. And he said, “No, Bill. We can’t do that!“ So I went to John and said, “I’m so sorry, man.” And he faked me out and said, “Yeah, Bill. No problem. I understand.”

Phil was often the contrarian to such things. Did he just have a strong sense of how things should be done?

Yeah… For some of that stuff, huh? He definitely had his vision of how everything should be. He was looser than that but sometimes he just didn’t want anyone coming on stage unless it was Ornette Coleman or someone.

Do you think that the pickiness of Deadheads kept you guys honest? You couldn’t get away with anything because they would call you on it.

No, I kept myself honest. I had a real esteem about playing good. I never, ever went out there feeling like I was going to throw one off. I went out with the deepest sense of giving the best I can to the audience. That’s what I’m there for. Not “I’m gonna play good for the Deadheads who know what’s going on.” It was for all people, for myself and for the music.

You say that post ’93, anyone listening to the tapes can tell that not everyone took that approach.

It was very frustrating because if any one person is having a seriously hard time, the band is at that level. You truly are only as strong as the weakest link in the chain.

Did that become a source of tension?

The tension in the Grateful Dead was all inside, because we didn’t communicate verbally very much. It was an internal boil and you could feel it in the music on stage. People would be sending each other signals and messages. When your lead guy is having such a hard time and forgetting words, there’s just no way you’re gonna say the music’s good. You can’t pretend. You can’t ignore that or cover it up.

Were you able to feel connected to the crowd once you were playing in stadiums?

No. Stadiums were the hardest for me because you didn’t get any contact. One of the things I loved doing at smaller gigs was find somebody in the front who was looking at me and smiling and I’d use them all night. They’d become my muse

The Wall of Sound is the craziest thing, but I never thought about if from the perspective of the guy sitting directly underneath until I read your book.

Ha! The first time I saw it was in Reno and the thing was blowing because they only had one two-ton winch up there and one chain down to it and I went, “Nuh-uh, no good. I’m not sitting under that thing.” I’m not an engineer but I said, “Put two more winches there, one on each corner so it’s triangular shaped, with the longest side on the speakers out front.” And that made it a lot better, but it was intolerable for other reasons!

It was too impractical. All your sound came from behind you and that’s ridiculous. It made the drums sound horrible. Just think about that much sound going out over you. It went right into the drum mics. It was far out, but it was hard for me to get real intimate. I didn’t like it.

You say that the band in later years had lost communication so much you couldn’t take acid together.

That happened pretty early on, I’m afraid, darn it. It happened at different times with different people. I became afraid to take acid after a while because you had to play for the crowd instead of yourself. Suddenly the energy of being free to play got lost and now we were just playing the songs good like any other band. It wasn’t a good acid experience anymore.

I gather that you are back to feeling comfortable taking acid and playing.

Yeah, there’s a thread of psychedelics in the book. I do every once in a while take a teeny bit.

You were the one who was adamant that the band was over when Jerry died.

Yeah. We had a meeting where names of people who could step in were being discussed. The others wanted to keep on going, but it was not for me. My feeling was that I didn’t make this decision; Jerry did. I was in serious grieving, which was not caused only by his death. Those years leading up to his death were very draining. We held in a lot of sadness and it all flushed out when Jerry died.

I was blindsided and emotionally distraught. I don’t even know how I could drive when I heard the news, but I managed to get myself to the ocean and surf. I didn’t even try to catch waves. I just laid on the water and cried with waves breaking all over me. I was almost paralyzed. 1995 was just the worst year of my life. Jerry died, then my father died a month later, and my girlfriend had lung cancer. I entered a serious depression, and was at home drinking wine and taking tons of pain pills. I called my doctor and said, “Get me into rehab. I can’t do this.” I went to Sierra Tucson, who helped me out immensely.

In 1998, there was a regrouping as The Other Ones, but you declined to join.

I was still in bad shape, physically and otherwise, and knew that I had to really heal Bill. And I was glad with my decision, because when I went to see them, I knew I could not be on that stage. I got there late, walked in to them doing Jerry songs, and felt terrible. It wasn’t good enough for me.

But after that, I did join the next Other Ones, with Alphonso Johnson on bass, who’s a fine musician and a wonderful human being. And for me, more than half of it is, how’s the person? Can you get along, look him in the eye, talk about something real? Where I come from, to play music it has to come from in here, the heart, not the head.

Is that what you look for now with the guys in Billy and the Kids?

Oh, yeah, and I have it. I had this interesting thing happen playing with the Dead many years ago up in Canada, where I couldn’t feel my body. I was out here observing myself playing. Maybe it’s like what a yogi does in meditation. And I had that feeling in practice the other day for the first time in ages. I was just going, “Wow! I’m not asking my body to do anything. It’s just doing.” And of course, as soon as I observe that, bam! It goes away. Being in the moment is the only thing that matters. It’s like active meditation.

How are you feeling about the upcoming Fare Thee Well shows?

I’m totally looking forward to them: to making Deadheads happy to see us again, and to playing real good. I’m very happy with my drumming right now and feel really confident.

Given the history, something special must happen when the four of you play together.

Well, we’ll find out! Phil and Jerry were my older brothers. And I loved them dearly and deeply and I still do. We might not get along right now or at a given moment, and we might not talk much, but I’ll love Phil forever. I can’t say too much about what we have planned for the shows, but I am looking forward to it all immensely.

It’s like I’m Billy Kreutzmann in 1965 and I’m Billy Kreutzmann in 2015. The way I feel about music hasn’t changed. My ability to play has certainly changed for the better. But the way I feel about the integrity of music hasn’t changed.

May 5, 2017

Another Gov’t Mule song debut – “Dreams and Songs”

Photo – Derek McCabe

As I’ve said, I am really excited about Gov’t Mule’s upcoming album Revolution Come, Revolution Go. I spent a lot of time with the album getting ready to interview for the next Guitar World cover story, and I can’t wait to share that with you.

I previewed the first two singles right here. Now you can hear another one, “Dreams and Songs,” below. I find this one to be very strong, emotionally honest and quite poignant, especially this week. Warren has had too many such weeks. The tune would not have been out of place in the soul-oriented Warren Haynes Band. If you listen to all three songs, their wide range will stand out.

Explains Warren in that upcoming GW cover story: “I just found myself writing in a lot of different directions and all of them seemed to work together especially when interpreted by the band and our collective personality. You never know where an album is going to head until you get into it.”

May 2, 2017

RIP Col. Bruce – A Tribute to a Friend and Genius

Photo – Jess Burbridge

Oteil Burbridge: “If you’re lucky enough, you’ll meet someone who will show you the impossible over and over again until one day you find yourself doing things you never thought you possibly could. Without him there would be no Oteil in the Allman Brothers Band or Dead & Co. There would be no Oteil From Egypt. He changed the entire trajectory of my life. He literally ‘changed my mind.’”

“Obituary writer for musicians I knew and loved” is a job I neither sought nor desired. And yet…

I went to bed last night texting with Kirk West, who was sending me reports from the massive 70th birthday tribute concert to our mutual friend, Col. Bruce Hampton at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre, featuring Warren Haynes, Derek Trucks, Susan Tedeschi and dozens of others. I wasn’t there because I had been in DC for the WH Correspondents Jam. Kirk was sending me messages like, “Derek, Warren and Chuck just blew the roof off this place with Schools and Duane Trucks.” And “Bruce played 20 minutes and has been sitting side of the stage grinning like mad.”

I went to bed smiling at all this and woke up to news that Bruce was dead, after collapsing during an all-hands-on-deck “Lovelight” finale. I am, of course, shocked, and am writing this in a bit of a daze.

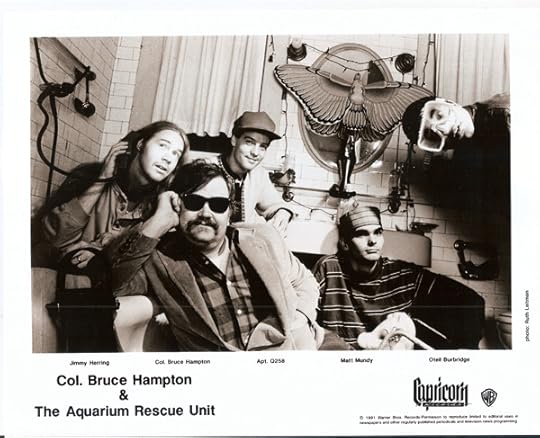

A few years ago, I wrote a Relix appreciation of Bruce and his fabulous Aquarium Rescue Unit, the band that spawned Jimmy Herring, Oteil Burbridge and, essentially, Derek Trucks and Widespread Panic. It is below and if you don’t know anything about Bruce, you should probably start there. I’m in a more reflective, personal mood right now and am going to share some impressionistic memories of our interactions.

Some of you may remember Bruce from Sling Blade, where he had a brief but memorable role. I met Billy Bob Thornton and discussed it with him on Friday. I do believe he was there last night.

His death has gotten more publicity than it otherwise would because it happened on stage in front of thousands. He was surrounded by musicians who loved and respected him, including quite a few, like Warren, Derek, Susan and Taz, who matter to me. Matter to me as people, not just musicians or public figures. The ghoulishness of a lot of the interest and sharing of what is really a painful video makes me sick. Please consider that. These are real people who experienced something emotionally traumatic. They are not props there for the amusement of websites and publications who had no fucking idea who Bruce Hampton was. With that off my chest…

Foto – Kirk West. Mr. and Mrs. Hampton at XMas Jam 2007. This one captures it all.

Bruce was one of the greatest truth tellers I’ve ever known. Quite a few times over the years, a conversation with him clarified my thinking about a position or shifted my perception about a person or a situation.

Yet he could talk shit with the best of them. He would spin elaborate tales that teetered very close to believability and deliver them earnestly, with a sense of awe and raised eyebrows that really made you wonder. He briefly had me convinced that Big Head Todd was a Golden Child who had been smuggled out as a baby to be raised in anonymity in suburban Colorado until he could take his rightful place on the throne. He told me that in the Wetlands dressing room, before he performed. I had been telling him about a dim sum lunch with Todd, Kirk West and a bunch of others that afternoon. I knew it was bullshit… and yet I wondered.

Bruce spun a lot of tales like this. Think Big Fish. So when I heard about his death and the circumstances around it, I couldn’t help but feel a tinge of awe mixed in with my sadness. He couldn’t have written a more dramatic climax. He died in the middle of his own memorial service. It felt like a story he would have told about a fabled bluesman, filled with enough concrete details to pull you along.

“So Blind Willie lived his life in commercial obscurity – he was a railroad porter for 52 years – but he had a huge following of musicians who revered him. Famous musicians. Big names. Big stars. They all bowed to Blind Willie. On his 70th birthday they threw him the greatest concert the world had ever seen on the stage of a sold-out Carnegie Hall. For the first time, he understood what his music had meant to the world.

“And on the final number, with all his acolytes on stage, ol’ Willie collapsed and died, with a big smile on his face. Some say you could see an angel rise to heaven. And right at that moment, the biggest shooting star anyone had ever seen lit up the Southern sky.”

The Colonel and me, Eddie’s Attic, 5-15-14. Photo by Rhiannon Bradley.

…Bruce and I hit it off immediately after meeting in 1991. I began writing about him and the ARU as often as I could manage in Guitar World. I made sure a picture of him was the dominant image in my story in the 1992 HORDE tour and I believe that I was the first writer to cover them in a national publication. Bruce was very appreciative of all this, but basically we just liked each other. We began talking on the phone occasionally, and I’d go hang whenever he passed through New York.

…Then Bruce left the road, saying his health was too poor to keep on pounding one nighters. I moved to Ann Arbor. Bruce started doing some more limited road work Another version of the HORDE tour was coming to Detroit and Bruce and the Fiji Mariners were on it. I made my way backstage, searched buses until I found Bruce and sat down for a nice long catch-up talk while Neil Young played on the big stage.

Bruce complained that Neil played the exact same set every night. Then he asked what I had been up to and I told him that in addition to my ongoing Guitar World writing, I had a new gig – covering basketball for Slam. His eyes lit up and he launched into a lengthy explanation for why Wilt Chamberlain was far superior to Bill Russell. Over the next 20 years, our conversations included not only Wolf and Muddy, Duane and Dickey, BB and Blue, but also Dipper and Bill, Cousy and Isiah, Jordan and Drexler. I hadn’t seen that coming.

Kirk West captured the Col. and his young Lt. Derek.

…I moved to China. I formed a band with three Chinese musicians. We became popular, played all over Beijing, toured, recorded a CD. I sent it to Bruce. He texted me back: “Amazing. Call to explain how this all happened.”

I called. We talked.

…I saw Bruce at Warren’s Christmas Jam in 2014. He was playing with Bill Kreutzmann. “I’m the sane one in this band,” he whispered in my ear.

… When I began writing One Way Out in earnest in 2012 or 13. I wanted to interview Bruce, who was close to Duane. On my first reporting trip to Macon, he told me to meet him at Cluckers, a mediocre suburban Atlanta chicken joint near his house that was his main hang. I slid into a booth and as we both sipped iced tea, he looked me in the eye and asked a simple but important question:

“Are you really ready for this?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“You’re about to drive down a dark road, my friend, and you’re a person of the light. Be careful.”

If that sounds cinematic, it was. But that’s how things went with Bruce, which is why for all the tragedy of his death – and it is a crushing, deeply sad tragedy – it is also somehow in character. Head-scratchingly in character. Spend-the-rest-of-your-life-trying-to-figure-it-out in character. The mythmaker made his myth.

But know also that there are many people who lost a good friend today. That there are legions of musicians whose North Star is gone, who will now have to discover how to navigate the cold dark nights without him in the world. Know that Bruce has a lovely, saintly wife who made this all possible and who will miss her husband very much for a very long time.

Bruce Hampton was a musical and metaphysical light who burned incredibly brightly, who inspired so many. A man who never took the straight path but always arrived at the straight truth. I feel very lucky to have spent as much time with him as I did and very sad that it wasn’t more.

“Jessica” from Bruce70 – Derek, Warren, Chuck, Duane, Schools

ARU, 1992. Pretty good representation of what I heard and saw the first time.

Early ARU photo – note pre-beard Jimmy Herring!

This story originally ran in Relix’ 40th Anniversary Issue.

In February 1992, the reunited Dixie Dregs were coming to New York’s Ritz and I was excited to check them out. Though I had always considered their music sterile if brilliantly constructed, I recognized Steve Morse as a brilliant guitarist. As a young Guitar World Managing Editor, I was anxious to expand my musical scope and appreciation and Steve was someone that I thought I should better understand. Publicist Marc Pucci pushed me to get there early to see the opening act, the oddly named Aquarium Rescue Unit

He assured me that the newly reformed Capricorn Records was very excited about the band, led by a longtime Atlanta cult hero, Col. Bruce Hampton (Ret.). Still pinching myself over living in New York City, working at a major music magazine and having publicists ask me to go to shows, I earnestly arrived at the Ritz close to starting time to check out this band with an open mind but with few expectations. They had just started when I walked in to the half-filed Midtown Manhattan ballroom and strolled right up to the lip of the stage, immediately astounded by what was unfolded.

A skinny redheaded guy with a beard was hunched over a Stratocaster, dispensing lightning fast licks that danced the razor’s edge I love, where everything could fall apart at any moment, though his sure-handed playing and obvious blues rooting made that highly unlikely. To his right, a handsome young man was grinning, eyes cast towards the sky as he worked a six-string bass with the same mix of skill and abandon, sometimes scatting along to the notes he played.

On the other side of the stage a dark haired guy with bushy eyebrows was blasting out supercharged bluegrass licks on a Mandocaster – a mandolin in the shape of a mini Telecaster. A brilliant drummer was laying down beats from enough angles to replicate at least two percussionists. Overseeing the whole thing was a crazy little man with a handlebar moustache playing some kind of demented short-scale instrument I would later learn he called a Chazoid. He sang like a bastard child of Bobby Bland and Hazel Dickens and occasionally played wicked, inspired licks. This was obviously the Colonel. He was clearly the ringmaster of this nutty circus, which radiated light and the spark of life and was hilarious without being a joke.

Questions bounced around my racing mind: Who was he? What was this? Why wasn’t everyone talking about this fabulous band? I pushed them all down and out because I wanted to stay in the moment, to drink deeply from this heady brew. I’d like to tell you how the rest of the crowd reacted, but I have no idea. I wasn’t looking around, solely focused on the stage, experiencing something that I have just a handful of times – musical nirvana that hit me in the head, heart and guts at the same time and was all the more powerful for being so completely unexpected.

After the show, I watched the musicians break down their own gear and got guitarist Jimmy Herring’s attention, introducing myself and telling him I’d meet him downstairs. I had been invited to a meet and greet, which I had originally planned on stopping by just long enough to see whether or not they had free beer, but my plans had changed.

In a little room downstairs, I chatted a bit with Bruce and spoke at length with Jimmy. We were both somewhat star struck – Jimmy was thrilled that a Guitar World editor had so enjoyed his playing. I was gob smacked that someone like him cared what I thought, and convinced that I had just discovered a major talent. I was right, of course, and as silly as Jimmy’s excitement seemed then and still seems now, it was revealing about both his nature and the group’s circumstances.

“We were making $92 a week and sleeping in one room,” Hampton told me recently. “After two years we got two rooms and we were so ecstatic we had a celebration. There were five of us in a Chevrolet van with 400,000 miles on it. How we did it, I’ll never know, but I never had more fun or made greater music than I did during that run.”

No wonder Jimmy was so happy that I had taken note of this brilliant musical circus; they were playing for love and for each other and I was an outsider acknowledging their instincts were right, that they were onto something. There is no greater satisfaction for an artist than some affirmation that their struggling is not for naught, something they had received precious little of outside their Atlanta base.

This group of five had been playing together for about two years. Bassist Oteil Burbridge and drummer Jeff Sipe (then called Apt. Q258) had been with Bruce for about three more years. Hampton originally hired Oteil as a drummer. “We played about three gigs and then he picked up the bass one day and I said, ‘That’s what you’ll be playing from now on,” Hampton says with a laugh. “He was a good drummer, but he was like the greatest bassist I had ever heard.”

All the musicians came to Hampton as virtuosos. He opened up their boundaries. Hell, he obliterated the very concept of boundaries.

“Old timers would tell me that Oteil was playing too much, but the song was always there,” says Hampton. “He never lost that. And he was 21 and full of this amazing energy, so why not let him be free? Then I told him, whatever he wanted to do, do the opposite.”

But isn’t that a contradictory concept – be free and do the opposite of what you want to do? “Yes!” says Hampton. “That’s it.”

If that contradiction makes perfect sense to you, then you are well on your way to understanding Hampton’s Zambi musical approach, which Burbridge sums up in a few words: “Bruce was our professor of out.”

The Colonel’s educational role was obvious, but to this day he cringes at being called a mentor, even after 20 more years discovering great young players.

“I learn as much from them as they do from me,” he says. “What made me unusual was that everyone my age had either quit or made it. No one was playing clubs and putting together new bands on the cheap like that.”

Hampton had been making music in Atlanta since the late 60s. His Hampton Grease Band drew the attention of Duane Allman, who became a friend and supporter and got the group signed to Capricorn, who sold the contract to Columbia. Hampton says that their 1971 album Music to Eat is the label’s second worst selling album ever. Hampton spent the next 20 years working on his own and with the Late Bronze Age until he started putting together the ARU.

With Oteil at Wanee, 2014.

Hampton says that what he offered his young protégés was guidance. “They were already great when they joined the band, but what I did was try to break their boundaries,” he says. “I’d say, ‘Don’t be a fusion drummer or a blues bass player. Discover who you are.’ It was thrilling to discover all this together, and we went places that no one had ever been before – and very few people saw it.”

While their own shows may have rarely grown beyond large clubs, the ARU played on the early HORDE tours and became prime influences on the many bands and musicians, notably Phish, Widespread Panic and Derek Trucks, who was an honorary member by the time he could have been Bar Mitzvahed. The ARU were the jam band Velvet Underground; a group whose influence vastly overwhelmed their commercial success. Most of the members went on to make their marks: Oteil as bassist of the Allman Brothers Band since 1998; Herring with the Allmans, Phil Lesh and the Dead and now Panic; Sipe with a range of bands. Mundy quit the group suddenly in 1993, giving up music. He plays again, though not publicly. Hampton has consistently put together great new bands, including the Fiji Mariners and the Codetalkers. Nothing in his approach to music has really changed.

“You either leave essence or you don’t,” he says. “ You either capture the moment or you don’t and you know at every show if you missed it or hit it, but you don’t know when it’s coming or where it comes from. That elusiveness is what keeps all artists going. But in the ARU, I think we only had one or two bad gigs in four years. Every night it was on and we would push each other to the outer limits. We sometimes played six or eight-hour gigs for 99 cents admission. In other words, we were a mental illness group.”

Anyone who heard this brand of illness either fell in love or scratched his or her head and walked away. But even as the band was earning converts, they were cracking under the strain of the road. Mundy’s departure cost them more than a unique musical voice. “He was the glue,” says Hampton, who quit touring himself within a year. The band continued for a few years with a couple of different singers, before everyone started drifting off to other gigs. They have reunited for brief tours and one-off gigs over the years, most recently at last year’s Christmas Jam in Asheville, North Carolina.

At that first show, I eventually said good bye to Jimmy, who had to load his own gear onto a trailer and push on, and went back upstairs to hear the Dregs. The playing was spectacular, but I couldn’t quite focus on the music. It was exemplary but it existed in the known universe. That no longer seemed like quite enough.

<A HREF=”http://ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widg... Widgets</A>

April 24, 2017

Gregg Allman on supporting the home team

Me and Gregg, March, 2009, NYC.

I’ve been going through my archives and interviews conducted for One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band and pulling out some great pieces and tidbits that didn’t fit the book but that I wanted to share. such as…

As discussed in the songwriting story in One Way Out,, Gregg Allman and Jackson Browne were roommates for a brief time in Los Angeles. Gregg credits Browne with inspiring him to become a real songwriter.

Though Allman lost touch with Browne, he remained enamored of his old friend’s work. Allman recorded a fantastic version of Browne’s “These Days” on his 1973 solo album Laid Back. A year earlier, Browne had made his recorded debut with his self-titled debut, which was packaged in a brown paper bag with the words “Saturate Before Using” across the top. (Jackson Browne (Saturate Before Using)

“I lost track of Jackson after my brother moved back down South,” says Allman. “I moved in with some broad and he went his own way and got some girlfriend. I didn’t know whatever happened to him; didn’t hear of him again until all of a sudden I was going by a record store in Macon one day and I saw his name on a paper bag in the window and I said, ‘Jackson! I’m a son of a bitch.’ I was so happy I went inside and bought one just as fast as I could. ‘Cause if your best friends won’t buy ‘em, who the hell will?

“My mother told me that. She says that about tickets too — people call for tickets when we play up around North Carolina. A lot of people, because she’s from there, a lot of people call her and ask her to get them tickets and she tells ‘em all — my mother, she beats around the bush with no one — she says, ‘If their best friends won’t buy the damn tickets, who the hell will? The place be empty if y’all don’t buy tickets. If y’all buy tickets, we know somebody’ll be there. Does that make any sense to you? You’re supposed to support your family, not ask ‘What can you give me?’

“My mother, though she might be in her own rented limousine, from me or my brother, she’d go around front and buy a damn ticket and bring it around back and hand it to us and say, ‘I just wanted you to know I’m supporting the team.’ Or she’d order ‘em ahead of time.

“I went and saw John Lee Hooker the other night, wanted to just buy a ticket and go in. I tried to buy a ticket. I wanted to support the team. I didn’t get out and jammed or anything. I just sat there and watched, but one of his people saw me waiting in line and grabbed me and brought me in. It really is nice to just be a fan sometimes. I saw ZZ Top and sat in the crowd. They’re one of my favorites. They did that Recycler tour. Wasn’t that fun? All them babes come out and sweep up. Look out! I went out and got my binoculars.”

April 20, 2017

Albert King Career Overview

Photo – Kirk West

I wrote a lot of entries for a couple of Music Guides many eons ago. I am going to start sharing some here, starting with one of my all-time favorite guitarists. If this interests you, please check out my interview with Albert here – it was one of my first interviews for Guitar World and it remains one of my proudest moments.

Albert King

Born April 25, 1923, Indianola, Mississippi, died December 21, 1992, Memphis, Tennessee

Never as well-known as his like-named contemporary, B.B. King, Albert King was nonetheless almost as big of an influence. In fact, more rock guitarists – notably Jimi Hendrix, Cream-era Eric Clapton and Stevie Ray Vaughan – have copped directly from Albert than any other bluesman. Standing an imposing six-foot-five, 250-pounds, the former bulldozer driver played with brute force, bending the strings on his upside down Gibson Flying V with a ferocity that could be downright frightening. King made his first recordings in the early Fifties and cut some fantastic sides for Bobbin and King Records from 1959-63, but he really hit his stride when he signed with Stax Records in 1966 and began working with Booker T and the MG’s and the Memphis Horns. His collaborations with them worked as well as they did because for all his toughness, King’s music swung, a fact well-documented on the excellent live albums where he recaptures the Stax albums’ drive backed by a horn-less quartet. He was also a fantastic, if not particularly flexible singer.

WHAT TO BUY FIRST: King’s Stax debut, Born Under a Bad Sign (Atlantic, 1967, Al Jackson) **** 1/2 is an undisputed classic. The two-CD compilation; The Ultimate Collection (Rhino, 1992) ***** offers a fine career overview. Any of the three live albums recorded at San Francisco’s Fillmore West Auditorium in 1968, all produced by Al Jackson, capture the full power of Albert King live: Live Wire/Blues Power (Stax, 1968) ***** Wednesday Night in San Francisco (Stax, 1990) **** and Thursday Night in San Francisco **** (Stax, 1990).

WHAT TO GET NEXT: Let’s Have a Natural Ball (Modern Blues, 1989) **** collects King’s late-fifites, early-Sixties sides, where he was backed by a hard-charging horn section. I’ll Play the Blues For You (Stax, 1972) **** includes the killer title track as well as “Little Brother,” perhaps King’s most tender moment. Soul-blues never got much better than this. In Session –with Stevie Ray Vaughan (Fantasy, 1999) **** is a great document of a historic meeting of pupil and teacher. Includes studio dialogue and a host of great tunes.

WHAT TO AVOID: Red House (Castle Records, 1991) ** is a misguided, probably well-intentioned attempt by producers Joe Walsh and Alan Douglas to help the great bluesman by modernizing his sound. Ugh. Somebody got really excited when they discovered long-missing tapes of Albert King jamming with John Mayall and a band highlighted by soul jazz greats. Then Fantasy released The Lost Session (Stax, 1986) ** and it became painfully clear why the tapes got shoved into the warehouse in the first place.

THE REST: Jammed Together: Albert King, Steve Cropper, Pops Staples (Stax, 1969) ***, Years Gone By (Stax, 1969) ****, Lovejoy (Stax, 1970) ***1/2, I Wanna Get Funky] (Stax, 1973) ***, The Pinch (Stax, 1977) **1/2, New Orleans Heat (Tomato, 1979) ***1/2, Montreaux Festival (Stax, 1979) ***, Blues for Elvis (Stax, 1981) **, Crosscut Saw: Albert King in San Francisco (Stax, 1983/1992) ***1/2, I’m in a Phone Booth Baby (Stax, 1984) ***, Blues at Sunrise (Stax, 1988) ****.

PROTEGES: Otis Rush, Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Buddy Guy, Billy Gibbons, Joe Louis Walker, Kenny Wayne Shepherd

MENTORS: B.B. King, Jimmy Reed, T-Bone Walker

April 19, 2017

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ team up

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ have teamed up for a new album, TajMo

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ have teamed up for a new album, TajMo , and will be touring together this spring and summer. They are two of my favorites and I’ve been paying more attention to Keb since the Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon. I thought his “In My Life” was a highlight – it is below. so I recommend that anyone who loves acoustic music and/or blues, check this out. Reminded of it again when the dup appeared with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert last night.

, and will be touring together this spring and summer. They are two of my favorites and I’ve been paying more attention to Keb since the Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon. I thought his “In My Life” was a highlight – it is below. so I recommend that anyone who loves acoustic music and/or blues, check this out. Reminded of it again when the dup appeared with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert last night.

“All Around The World” with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert:

“Don’t Leave Me Here”

Keb Mo’ “In My Life,” Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ have teamed up for a new album,...

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ have teamed up for a new album, TajMo

Taj Mahal and Keb Mo’ have teamed up for a new album, TajMo , and will be touring together this spring and summer. They are two of my favorites and I’ve been paying more attention to Keb since the Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon. I thought his “In My Life” was a highlight – it is below. so I recommend that anyone who loves acoustic music and/or blues, check this out. Reminded of it again when the dup appeared with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert last night.

, and will be touring together this spring and summer. They are two of my favorites and I’ve been paying more attention to Keb since the Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon. I thought his “In My Life” was a highlight – it is below. so I recommend that anyone who loves acoustic music and/or blues, check this out. Reminded of it again when the dup appeared with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert last night.

“All Around The World” with Jon Batiste and band on Colbert:

“Don’t Leave Me Here”

Keb Mo’ “In My Life,” Love Rocks NYC show at the Beacon

Audio of great Butch Trucks Interview

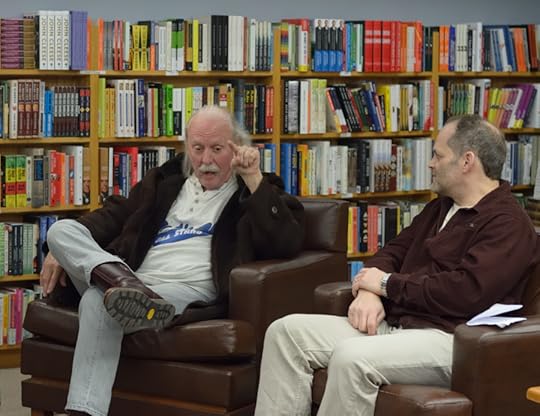

Butch interview @ Words, Maplewood, March, 2015.

This weekend’s Wanee Festival, which I will sadly miss, is filled with tributes to Butch Trucks, starting tonight when his Freight Train Band will kick things off. It felt like a good time to share the following.

I spent many hours talking to Butch and I think this Podcast captures the experience quite well. The whole text of his final interview, conducted just hours before his death, is also well worth reading. It just makes the puzzle all the more puzzling, the mystery all the more mysterious.