Alan Paul's Blog, page 11

September 6, 2017

Gregg Allman: A Personal Reflection

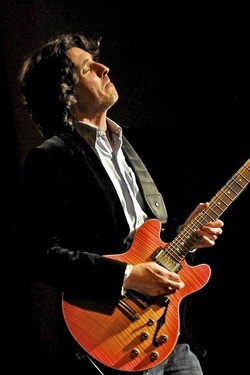

Photo – Derek McCabe – Note Farmer to the left.

I wrote this personal reflection on Gregg for Relix. It appears in their stellar tribute issue. I am re-posting in advance of the Friday, September 8 release of his final album, Southern Blood.

“Check this out, man!”

Gregg Allman leaned back in his chair and pulled his shirt up to reveal giant scarring across his midsection.

“Ooh boy! If they told me how much it hurt, I would have just said, ‘No thanks; I’ll die!”

Gregg let out a long laugh, pulled his shirt back down and took a sip of a cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee that his longtime right hand man Chank Middleton handed him. He was joking about preferring to die over suffering the pain of the liver transplant, but everything about his mood that day screamed, “Happy to be alive!”

This was October, 2010, in a New York Hotel room, during one of his first interviews after the transplant that saved his life a few months earlier. We were there to talk about his upcoming solo album Low Country Blues. A night or two prior he had made his first post-surgery appearance, singing a few songs with a T Bone Burnett revue, which he would do again that night at the Beacon.

“I’m glad I got that one of out the way!” he said. “I was as nervous as a whore in church, man.”

I chuckled at the description. I had heard Gregg use similarly colorful descriptive phrases over the years in our many interviews. He once explained the way “Midnight Rider” came to him in a flash of inspiration by noting, “it hit me like a sack of hoe handles.” Playing electric guitar was “like having a dragon on a leash.” Ray Charles, Little Milton and Bobby Bland were the three guys “who really blew up [his] skirt.” This was Gregg at his best: funny, charming, insightful, downhome.

He was in prime form that day, as he often was in quiet moments away from the stage. Before a show, Gregg could be a sullen, foreboding presence, all but emitting a force field that said “stay away.” This was surely a mix of wanting to get his game face on, being a private man who wanted to be left alone after a lifetime in the spotlight, and a reflection of the stage fright that remarkably never vanished. A different person would emerge when he was comfortable: relaxing on a dressing room couch shaking out his ponytail post-show; reclining on a tour bus sectional; chilling in a hotel room; or holding court with old friends, especially beloved blues musicians.

At such times, Gregg likely had one of his little dogs curled up in his lap, with another maybe nipping at his feet as he scratched her ears. His wife might be cuddled up by his side or dozing nearby. He would often have a bottle of water or a cup of coffee in his hand and sometimes be holding a joint, especially in the earlier years of our acquaintance. A TV would often be playing a classic movie or the hot TV show of the moment, because Gregg was a film and TV buff, who could talk enthusiastically about Steven Spielberg’s genius or his frustration that Mulder and Scully “didn’t do it already” on The X-Files.

Foto – Kirk West. Gregg and Jazzy, 1991.

At times like this, Gregg Allman, rock star, was nowhere to be seen and I met Gregory, the guy Jaimoe talked about all the time. He might express some indignation that no one quite understood how hard he worked to master his craft. “People think I was born with my voice, that I just opened my mouth and it came out, but I went to great lengths to develop it,” he told me once. “I devoted my whole life to it because I really wanted to learn how to sing.”

Or he might surprise by explaining what a big influence folkies Tim Buckley, Steven Stills and Jackson Browne were on his songwriting. “Shakespeare said, ‘a rose by any other name is still a rose’ and people consider that profound; well, people like Jackson Browne have said things just as profound, to me. He really touched a soft side of me and made me want to be a songwriter and find new ways to express things.”

That last quote was in 1996, during a middle of the night interview in a Chicago hotel room. That night he spoke at length about the impact that rooming with Browne and seeing people like Buckley and Stills had on his development as a songwriter.

When Gregg was being reflective and honest, the conversations often turned to songwriting and folk music and blues and soul heroes. To the differences between the “small amps” of his solo band and the “big amps” of the Allman Brothers Band. There was always an undercurrent of frustration that his gentler side was obscured and overlooked in favor of the Allman Brothers’ blues swagger and the band’s split personality, communally formed by six members and democratic until the end. “It can get really fucking frustrating,” he told me in that same Chicago interview. “But it’s something in me; it’s part of my metabolism and my nervous system. I can’t be me without you.”

Few of these conversations occurred in the first five years I covered the band extensively, 1990-95. During this time Gregg was often a ghostly presence who appeared behind his B3 and vanished when the curtain came down. His on and off struggles with drug and alcohol addictions led him to be virtually non-existent in the band’s telling of their story: Dickey Betts, Warren Haynes and Butch Trucks did most of the talking in those days. Gregg went to rehab in January 95, the day after the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and while his sobriety may not have been a straight line, he was a completely different person before and after that day, with a ton of support in the first decade or so from his wife Stacey. His last 22 years, when the real Gregory re-emerged more and more often and he reclaimed his rightful place as an American treasure, were a blessing.

I knew for months that Gregg was fatally ill and I thought that I had “pre-grieved,” that I was prepared for his passing, but the news hit me like a right cross. Gregg had dodged so many bullets that he seemed invincible. The finality was too much to bear. It was like hearing that George Washington had fallen off Mt. Rushmore.

August 11, 2017

Roots Rock Revival: What It’s All About

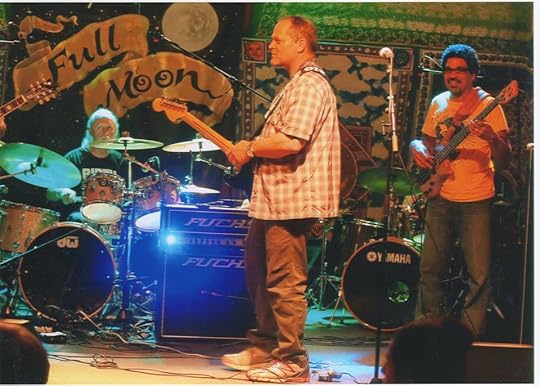

Jamming with Oteil and Butch, 2014. This explains a lot but not all of why Roots Rock is so great.

On Monday, August 14, some 100 music lovers and jam fiends from all over the world will descend on the Full Moon Resort near Woodstock New York for the fifth annual Roots Rock Revival music camp. Roots Rock was the brainchild of Allman Brothers drummer Butch Trucks, who recruited a staff of teachers/counselors including bassist Oteil Burbridge (Allman Brothers, Dead and Company) and brothers Cody and Luther Dickinson (North Mississippi All Stars).

This year the camp will continue without Trucks, who died in January. Two legendary drummers Bernard Purdie and Johnny Vidocovich will be on hand, along with former Allman Brothers guitarist Jack Pearson, keyboardist John Medeski and a host of other instructors including Butch’s son Vaylor Trucks and Berry Duane Oakley, son of original Allman Brothers bassist Berry Oakley. The whole camp will be dedicated to celebrating the life and music of Butch Trucks and Col. Bruce Hampton, who was aninstructor in past years and who also died this year.

Roots Rock is part of the Music Masters series, which also includes camps with Dweezil Zappa, Richard Thompson, Robben Ford and members of the extended The Band family. It was Butch Trucks’ baby and the decision to continue on without him was difficult, but only for a moment, according to Henry Stout, who founded and runs the Music Masters camps.

Oteil at Full Moon

“After mourning, everyone agreed that ‘he road goes on forever’ and none of us had any question that Butch would have wanted us to carry on,” says Stout. “ Butch and I had a deep understanding and connection regarding the concept of Roots Rock Revival. Roots is a home base for carrying the torch of his legacy and passing on the music of the Allman Brothers Band.”

Luther, Oteil and Butch in the Barn. Captures a lot.

Adds Burbridge, “We could have never have anticipated Butch’s absence, but we quickly had a lot of participants voice their desire to see it continue. We’ve grown to really appreciate and cherish the relationships that have grown out of our camp. ultimately for me it had to be all about the campers. It was for them in the beginning and it still is now. We need to learn from Butch’s life and his death and apply those lessons to our present and future.

“We also have had some really great musicians agree to come and participate this year. After losing Butch to have Bernard Purdie and Johnny Vidacovich bless us with their presence is really amazing. They are both legendary figures in American drum history. We’re so excited for our campers to get a chance to see them in action and personally pick their brains as well as the other great guest teachers.”

James Biehn, Luther Dickinson, Lara Cwass, Berry Duane Oakley

As much as the staff is central to the experience, the campers themselves have formed a cohesive family-type atmosphere. There is a large percentage of returnees who not only welcome the annual reunions, but stay in touch throughout the year, form bands, meet up for shows and immediately welcome newcomers into the fraternity. Attendees range the gamut of musical experience, from weekend warriors to people with many years of gigs under their belts. Brandon “Taz” Neiderauer, who has been at every Roots Rock camp, was taken under his wing by Trucks and other counselors the first year, 2013, when he attended as a nine-year-old. This year, after a long run starring in Broadway’s School of Rock, sitting in with dozens of acts and establishing himself with his own band, the 14-year-old will be there as a guest artist.

“The opportunity to play with other like-minded musicians, let alone the chance to sit in with Butch, Oteil the Dickinson brothers and so many others is just amazing,” says Chris Dinardo, a New Jersey guitarist and bassist. Chris has played several gigs with my band – after we met at the second Roots Rock in 2014. “I’e met so many talented musicians from around the world at Roots Rock and while it may sound cliché, many have come like family members. We celebrate each other’s successes and mourn losses.”

Over the years, the campers have not grown only close to one another but to the staff.

“Watching the campers growth over the years is always the biggest mind blower,” says Burbridge. “That’s always the biggest change that I notice. The Roots Rock community overlaps on different levels. A lot of the campers are obviously into live music as fans, they are probably festival goers, some are playing professionally, some are hoping to do so one day, no matter their age. It’s great to see friendships develop and run into campers outside of Roots Rock Revival at a concert somewhere or when I’m on the road.

“That’s why my favorite part of Roots Rock is just seeing everybody. Hearing everybody’s progress. Getting questions I would have never expected. Seeing the excitement of all the campers at being back at Full Moon. And the camp has definitely had an impact on m own playing. I always learn a lot from teaching and interacting with others. All the different viewpoints always result in enlightenment in some degree. It’s a great mirror and measuring stick to have someone else dissect the mechanics and philosophy behind what you choose to play. It inevitably makes me realize just how many things I don’t consciously think of when I am playing. The human computer is still the greatest.”

Roots Rock Revival runs from Monday August 14-Friday August 18. There are still a few spots available.

Inside Roots Rock Revival from Music Masters Camps on Vimeo.

August 9, 2017

Watch video for Gregg Allman’s “My Only True Friend”

Photo – Marc Millman

Rounder Records has released a video for “My Only True Friend,” the first single off of Gregg Allman’s last album, Southern Blood , which will be released Sept. 8 but can be ordered now by clinking the link in the album title. The song is very moving and the video is very cool. What do you think?

, which will be released Sept. 8 but can be ordered now by clinking the link in the album title. The song is very moving and the video is very cool. What do you think?

Photo – Marc Millman

Rounder Records has released a v...

Photo – Marc Millman

Rounder Records has released a video for “My Only True Friend,” the first single off of Gregg Allman’s last album, Southern Blood , which will be released Sept. 8 but can be ordered now by clinking the link in the album title. The song is very moving and the video is very cool. What do you think?

, which will be released Sept. 8 but can be ordered now by clinking the link in the album title. The song is very moving and the video is very cool. What do you think?

August 1, 2017

Watkins Glen Summer Jam: the story behind the largest rock festival

In honor of Jerry Garcia’s 75th birthday, I present this extensive, exclusive article on the Watkins Glen Summer Jam, at the time the largest concert ever. What an event. This story ran in a Grateful Dead one shot I wrote and edited for Parade along with the great GD historian Blair Jackson. We did great work and it was under-seen. I am trying to figure out how to get this out to more people.

In 1973, the Grateful Dead, Allman Brothers Band and The Band teamed up for the Watkins Glen Summer Jam in New York’s Finger Lakes Region. It was the largest music festival ever, drawing about 650,000 people — nearly twice as many as Woodstock four years earlier. The festival was the culmination of a mutual admiration society between the Dead and the Allman Brothers that existed almost from the latter’s beginning.

In 1973, the Grateful Dead, Allman Brothers Band and The Band teamed up for the Watkins Glen Summer Jam in New York’s Finger Lakes Region. It was the largest music festival ever, drawing about 650,000 people — nearly twice as many as Woodstock four years earlier. The festival was the culmination of a mutual admiration society between the Dead and the Allman Brothers that existed almost from the latter’s beginning.

The Allmans were one of the first major groups to adopt the Dead’s two-drummer format in the late ’60s, and the Allman’s famous “Mountain Jam,” based on the melody of Donovan’s “There Is A Mountain,” first appeared as a brief musical quotation on the Dead’s trippy Anthem of the Sun in 1968, an album the Allmans knew well. The two bands first crossed paths in the summer of 1969 when they played for free in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park. The Dead, already well-established hippie heroes, arrived after the Allman Brothers, whose debut had not yet come out, had played, but they met and socialized. The ABB’s Duane Allman, Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley were particular fans of the Dead, a respect that was often returned by Jerry Garcia and the rest of the band.

“We always loved playing with the Allman Brothers,” says Bob Weir. “It was clear from the first time we played together that we were kindred spirits.”

The two groups’ first bill together was three shows at New York’s Fillmore East, February 11 -14, 1970. The first night of the run featured an epic jam, with most of the Allman Brothers joining the Dead, along with guitarist Peter Green and other members of Fleetwood Mac, who were not on the bill. Over the next couple of years, there was just one more joint billing and a few sit-ins, even as the simpatico nature of both the musicians and their fans became more evident.

“The Dead’s philosophy was always very similar to ours,” Allmans Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts said in 1994. “We sound very different, because we’re from different roots. They’re from a folk music, jug band, and country thing. We’re from a urban blues/jazz bag. We don’t wait for it to happen; we make it happen. But we’ve always had a similar fan base and philosophy — keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.”

Duane and Jerry often expressed admiration for one another’s each other’s work, and a friendship was budding. Duane even popped into a Boston radio station on November 21, 1970, when Weir and Garcia were performing acoustically. He picked up a guitar and joined in. Six months later, during the Dead’s final week of shows at the Fillmore East, Duane turned up for the April 26, 1971 and added his distinctive sound to three tunes.

“We developed a close relationship with Duane that unfortunately never had the time to blossom because he was gone so soon,” says Weir.

Following Allman’s death in October 1971, the two bands finally planned a few joint shows together, which Dead crew member Steve Parish described as “trying to support our friends” during a difficult transition. The performances were scuttled when Oakley died the night before the first scheduled show, in Houston. By the time the bands finally played together again, on June 9 and 10, 1973, they had both grown so popular that they co-headlined Washington DC’s RFK Stadium, alternating opening and closing slots.

On July 28, they topped two nights at a stadium with the Watkins Glen Summer Jam. The one-day festival was planned by the Dead’s Sam Cutler and the Allman Brothers Band’s Bunky Odom. They agreed together to invite The Band to open the day’s music.

“We thought those three bands represented America,” says Odom. “They were the three best American bands and they related to each other, the music related, the fans related and they all knew each other. It was just a great fit.”

The concert was planned for the Grand Prix speedway in the remote hamlet of Watkins Glen, New York. The concert was produced by two young promoters Jim Koplik and Shelley Finkel, who paid the Dead and Allman Brothers $110,000 each. One hundred and fifty thousand tickets were sold for $10, but the crowd exploded to many times that number. The rest got in for free, though many of the masses certainly never got within sight of the stage. The small country roads leading to the concert site became parking lots – first figuratively, then literally, as many people abandoned their vehicles and walked miles to the concert.

“It was hard to get in and out of that place,” says Weir. “It got way, way bigger than we intended for it to get. We thought maybe if we’re lucky we’d get 100,000 people; 60-70,000 would be nice and handle-able.”

The bands were staying 18 miles away in a small motel in Horsesheads, New York. The day before the festival they were supposed to soundcheck but the roadways were completely blocked by people abandoning their vehicles in the standstill traffic and walking to the raceway grounds.

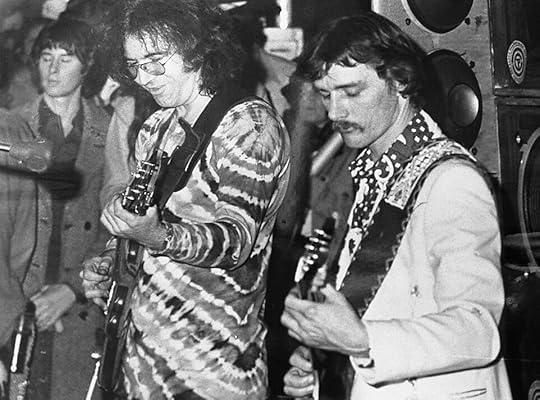

Jerry and Dickey, NYE 73. Photo – Sidney Smith

“When we first got there we were able to drive in and out of the site, but the road became like Armageddon overnight,” says Allman Brothers tour manager Willie Perkins. “It was like there had been a nuclear attack and people had just abandoned their cars.”

It was obvious that the band and crew would not be driving to the concert ground. Helicopters were summoned and as they drew close, the passengers asked the pilot to circle the site.

“We wanted to soak it in and it was absolutely stunning, exhilarating and exciting to see this incredible mass of human beings,” recalls Allman Brothers keyboardist Chuck Leavell. “It was an ocean of bodies. We were all just really buzzed by the whole scene and situation.”

“All the stuff like transportation just broke down,” says Parish. “Amenities were impossible to maintain, fences were broken down. It became a serious security situation for the crowd, but the stage was secure.”

With crowds pouring in and an estimated 200,000 people already on site, the July 27 soundchecks became public performances. The Band did about 45 minutes. The Allman Brothers pushed close to two hours, and the Dead did an almost-complete show. The one-day festival had organically doubled in length.

Recalling the soundcheck still registers amazement in the voice of Allman Brothers drummer Butch Trucks. “That afternoon rehearsal ended up being my most powerful memory because in daylight you could see 600,000 people stretched out in front of you and my God! What a sight!” he says. “Everyone should get up in front of 600,00 people some time in their life. It’s sort of intimidating but also very, very inspiring.”

At Cutler’s insistence, the promoters had hired Bill Graham, a key figure to both the Dead and Allman Brothers, to handle the staging and backstage area. Graham had taken his usual care in constructing a welcoming backstage area, which Perkins recalls as “idyllic.” Palm trees were brought in and most band members had their own trailers, traipsing in and out of one another’s spaces, with endlessly mutating jam and hangout sessions. Leavell, Kreutzmann, Garcia and Jaimoe seemed to particularly enjoy playing with one another. In his memoir, Deal , Kreutzmann writes that his best memories of the Summer Jam was playing with Jaimoe backstage.

, Kreutzmann writes that his best memories of the Summer Jam was playing with Jaimoe backstage.

While the bands were enjoying each other’s company, the crowd just kept swelling. Impossibly hot weather was interrupted by rain storms, but things remained mostly calm and friendly. In A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead , Dennis McNally reported that the county sheriff said, “We have four or five times as many people here as we have at our races, and we are getting less than half the trouble. These kids are great.”

, Dennis McNally reported that the county sheriff said, “We have four or five times as many people here as we have at our races, and we are getting less than half the trouble. These kids are great.”

“The news reported there were 600,000 there and maybe 2 million people in the area and it was declared a disaster area,” recalls Weir. “As disaster areas go, it was a pretty nice one, but people who were interested in going home, for instance, well, they couldn’t. If they wanted to leave, it just wasn’t possible. People had to be peeled away by layer by layer.”

Each of the band’s performed long sets. The Dead opened and were followed by The Band, who had not played together in a year. Their performance was interrupted by a thunderstorm before the Allman Brothers closed out the day with a four-hour performance capped by an all-band jam. Legend and the band’s own deprecatory comments have it that as with Monterey Pop in 1967 and Woodstock in ‘69, the Dead’s performance was limp. While the show was never officially released, widely circulated recordings indicate it was stronger than the band itself recalled. Still, most Deadheads swear that the soundcheck performance was more powerful.

“We got the short stick on who would open and who would close,” says Weir. “As I recall, it was essentially determined by drawing cards out of a hat because it was impossible to rank the bands. It would have been nice to have the lights and we didn’t get them because we played in daylight. I do remember the jam at the end was pretty spectacularly wiggy.”

One can debate whether Weir meant to say the jam was great or terrible—but Allman Brothers drummer Butch Trucks is far more direct in his assessment: “The jam was just ridiculous, because by the time we all got together everyone was fucked up — and fucked up on different drugs. The Band was all drunk as skunks and sloppy loose, the Dead were full of acid and wired in that far-out way, and we were all full of coke and cranked up. You put it all together and it was just garbage. While we were playing, we thought it was the greatest thing the world had ever heard, but then we listened to the playbacks.”

Five months after the landmark concert, the Allman Brothers played the Cow Palace in San Francisco on New Year’s Eve, in a performance nationally broadcast on radio. The Dead were off that night, and Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann sat in for much of the second set and encore, with Kreutzmann taking over for Trucks, who was dosed with LSD and unable to continue playing. The friendships between the two titans of the jam rock world seemed to be growing, but they would never again share a bill.

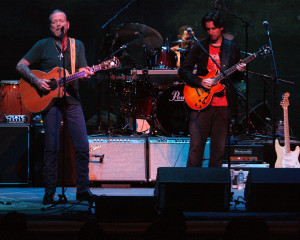

Scott Sharrard on Gregg Allman – w/ song preview

I interviewed Scott Sharrard, who played guitar with Gregg Allman since 2008 and became the musical director in 2015, for my Guitar World tribute to Gregg. I could only use a couple of quotes in that piece. An edited version of the rest of the story is here. Though I have been listening to an advance copy of Gregg’s Southern Blood

I interviewed Scott Sharrard, who played guitar with Gregg Allman since 2008 and became the musical director in 2015, for my Guitar World tribute to Gregg. I could only use a couple of quotes in that piece. An edited version of the rest of the story is here. Though I have been listening to an advance copy of Gregg’s Southern Blood for weeks, this interview was conducted before I had heard it.

for weeks, this interview was conducted before I had heard it.

Gregg’s health was up and down in the last few years, which led to cancelled shows. People always talk about playing each performance like it could be your last, but I wonder if you had a sense of him really thinking about that.

It definitely got more intense. He always had a certain ethos to playing. Certainly, no one could ever question his dedication. That guy fought to he last to go on stage is what I think. He was fighting against all odds and very few people knew that, because that’s how he wanted it.

The second to last show I played with him was at Red Rocks and he was having tremendous breathing problems, struggling with the altitude there. The guy would insist on making the gig! He would not take no for an answer. That night he was backstage and could not move. We had to carry him to the stage and then he picked up the guitar and the songs were slow but they were magical.

And then a month later, he played his final show, October 29th, 2016, in Atlanta.

Yes, and the first with the full band in a while, so we were all very happy. The first four songs he came out like a lion and the whole band was basically high fiving. As the show went on, his and power pitch started to diminish. I had a feeling that was it. They tried to bring him to New York for the 20 shows at City Winery but he was unable to stand up and perform.

He literally was torturing himself so he could be on stage and give a show for his fans. I can tell you 100 percent that he did not want to ever stop performing. If he could sing a note, he did it. He performed until he literally could not sing a note. That was last November and from there he went into an inevitable health decline.

The lead single of Southern Blood , co-written by Gregg and Scott;

, co-written by Gregg and Scott;

Gregg once told me the difference between the Allman Brothers Band and the Gregg Allman Band as “the big amp thing” and “the small amp thing.” Did you guys explicitly discuss what he wanted in that regard?

Yes, but not exactly like that. He would say all rock and roll is Southern Rock, so the whole designation of Southern Rock was BS to him. He basically saw it as he was playing rhythm and blues, blues and soul music but coming out of him it was rock and roll. He would always say that’s the way it started with Duane but somewhere along the way Duane got into Cream and psychedelic rock and it took the music to another place

So Gregg always considered his solo band to being a return to where he and Duane started, before his brother got into psychedelic rock. That’s how he talked about it.

He saw the band as his ultimate dream realized. Once he retired the Allman Brothers and put that to bed, he just poured it all into his band. It was interesting to watch. A lot of people thought I would be happy about all that, but at the last show, I was honestly very sad to see it go. I always hoped he’d keep it going and do both bands because I love the Allman Brothers Band very much. But it was also cool to see him devote everything to one band. He said many times he thought this band we had at the end was the best he ever had. He told us that every day and he was so happy about it.

That’s quite a statement.

That’s quite a statement.

I think once Duane died it really shattered him on many levels and he shut down a lot. Certainly we saw Dickey jump into the fray and grab the baton in the 70s and it led the band to its greatest success. Though very different, Dickey is also very song oriented – think “Rambling Man” and “Blue Sky” – but it moved away from Gregg’s music, I guess. The band went through a lot of things and I think Gregg kind of shut down and withdrew, at least until the 90s.

I was just listening to “Ain’t Wasting Time No More” from the Back To Macon, GA  album and it’s a really good example of how you guys rearranged an Allman Brothers song, replacing guitar solos with sax solos.

album and it’s a really good example of how you guys rearranged an Allman Brothers song, replacing guitar solos with sax solos.

I put that arrangement together because Gregg really loved having Art [Edmaiston] and Jay [Collins] play sax solos. They are very different players. Art is a Memphis guy with a big tone. Jay is more of a New York guy. What I tried to do with the horns is approach the tenor saxophone as the other guitar so if you’re playing any Allmans tune, I would use Art or Jay as my foil a la Dickey and Duane. And that’s easy for me because easily my biggest influences in improvising are Miles Davis, King Curtis, Maceo Parker and Junior Walker. I’ve learned more saxophone and trumpet solos note for note than guitar solos. Gregg liked that and he was very supportive of my style.

The bond we had really in common was the blues. When I was still pretty young, I was in clubs in Milwaukee playing with Pinetop Perkins and Hubert Sumlin. I came from school of learning real blues from the real dudes, and that’s something he would comment on. The blues was his grounding whether it was “Melissa,” “Whipping Post” or “Ain’t Wasting Time.” They all have different grooves and feel and structures but the blues was the ground floor of anything he did. It was always the base.

How direct was Gregg in his directions to you as a guitarist and musical director?

When he wanted something he was very direct about what he was looking for. He would also take the time to assess what was happening. He was patient and one of the hallmarks of Gregg is he was very careful with his words. He was very sensitive to how other people felt to criticisms or suggestions and extremely sensitive to very subtle creative things, like the dynamics of a band. And when we were doing songwriting together especially, he was very sensitive about honoring the intent.

What he would do to my lyrics would change the perspective and mood to fit his style and, of course, working with him in that way was a thrill and an honor.

You and Gregg seemed to become very close. Are there any memories you’d like to share?

I spent a couple days with him a few weeks before he passed away. We had a really intense hang at his house and I’m going to keep those memories to myself for now but it was really, really special and I am very happy we had that time. I brought him a gift that was very special to me and we had a very special bonding and hang and I was granted a very rare opportunity to see someone who started out as a hero of mine and became an employer, a mentor and a friend and I was able to express to him all that. We were able to heave a lot of laughs and I could ease his pain, so I feel very good about all that.

Photo – Mac MIllman

That’s wonderful. And it must have been very emotional to return South for his funeral just a few weeks later.

Yes, of course. Going to his house and funeral and burial was also a very intense experience and realizing I’ve actually become part of the family was just… to feel like you belong to a band like that, it’s overwhelming and very empowering.

Gregg played a lot of guitar in his band. How would you describe his playing?

His acoustic guitar playing has been well established and really cool, particularly when he was playing with fingerpick, as on “Midnight Rider” and “Come and Go Blues.” On those tunes, his voice and acoustic guitar became the vocal point of the arrangement.

On electric, he was more in support . We would bear the weight of doing the arrangements and he would put his guitar on top of that. He was a really complementary player. The way he played reminded me a lot of Jimmy Reed. That was our template, actually. The first thing I learned was a Jimmy Reed 12-bar pattern and same with Gregg: “Baby What You Want Me To Do” is how it started for him.

So what’s next for you and the Brickyard Band, Scott?

I will be honoring Gregg by creating new music in the ethos and in the mold that he and his brother set down. You’ve got to acknowledge there will not be another one of those. Gregg and Duane and the Allman Brothers Band just stand alone.

This is a moral imperative for a musician; we have to give people the songs they need and work much harder to find originality that’s rooted in tradition. That’s what Duane and Gregg did, and that’s how you honor them.

July 20, 2017

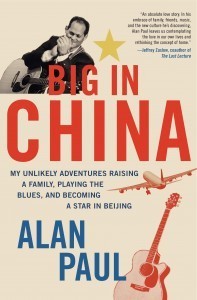

Introducing my Chinese bandmates to the Allman Brothers Band

This is an excerpt of my first book, Big in China. Signed copies are available directly from me here, where you can also learn a lot more about the book. It is also available in Kindle right here or as an Audiobook narrated by me here.

A little background first:

Occupied with settling down and helping my three kids, aged 2, 5 and 7, get their feet on the ground, I barely touched my guitars my first year in Beijing. To inspire myself, I bought a beautiful tobacco sunburst Epiphone 335 during an extended summer visit home to the US. When I opened the case back in Beijing, the headstock was dangling off.

A friend told me that Woodie Wu, a young Chinese guitarist who had recently returned from three years in Australia, could solve my problem, and he did — but I got back much more than a fixed guitar. Woodie and I hit it off right away. When I saw the huge Stevie Ray Vaughan tattoo on his arm, I knew we could do business. When I found out that he wanted to jam and was now focusing on lap steel guitar, I was thrilled; the sound of slide guitar has touched me deeply since the very first time I heard Duane Allman.

I jammed once with Woodie’s band, and knew I needed the sound of his slide in my life. I had already had a couple of memorable jams with American saxophonist Dave Loevinger and now heard a sound in my head with Dave’s soulful sax in one ear, Woodie’s weeping slide in the other and my own voice and guitar in the middle. We played one raggedy but promising trio show then about a dozen gigs with a few different rhythm sections before Woodie brought in bassist Zhang Yong and drummer Lu Wei.

Lu Wei fired us up with passionate, r

aw-edged drumming, while Zhang Yong brought not only rock solid, funky basslines, but also a composer’s knack for memorable melodies. We started rearranging all the cover songs that we were playing and began writing our own material. I had a hard time explaining to the guys how we had

to loosen our sound back up after we had tightened it beautifully with new arrangements and intense rehearsals. “Tight but loose” was an obvious concept to me, but one I struggled to have my Chinese bandmates understand.

Lu Wei fired us up with passionate, r

aw-edged drumming, while Zhang Yong brought not only rock solid, funky basslines, but also a composer’s knack for memorable melodies. We started rearranging all the cover songs that we were playing and began writing our own material. I had a hard time explaining to the guys how we had

to loosen our sound back up after we had tightened it beautifully with new arrangements and intense rehearsals. “Tight but loose” was an obvious concept to me, but one I struggled to have my Chinese bandmates understand.

The story that follows illustrates how I stumbled upon the missing piece we needed to really break through and find our own voice: the music of the Allman Brothers Band. Just a few months after this encounter, we were named the Best band in Beijing and were hard at work recording Beijing Blues, our debut CD.

***

The band began meeting regularly at our new rehearsal space, a studio inside drummer Lu Wei’s duplex apartment in Tongzhou, on Beijing’s eastern fringes. To get there from my place, you drove out of town, through some countryside, then reemerged in a sea of high rises. It was a reminder of just how sprawled out Beijing was.

Tongzhou was a satellite city with over one million residents, but few foreigners even knew it existed. The first time I went there, I hired a driver, the second time a friend who speaks excellent Chinese accompanied me and spoke to Lu Wei all the way. After that, I drove myself, feeling proud every time I arrived at my drummer’s rundown compound, which had weeds sprouting through the concrete and disinterested young guards who just waved at me.

As distant as the place felt, Lu Wei’s house was immediately recognizable as a slacker band crash pad. I could have been in Ann Arbor or Austin. A couple of roommates lounged on a little couch in the middle of the day watching soap operas with their girlfriends. A small drying rack sat in the living room hung with laundry, including a pair of leopard-spotted panties. An overflowing ashtray sat on the coffee table and a stack of Chinese drum, bass and guitar magazines sat atop the upstairs toilet.

The Woodie Alan Band

One bedroom on the second floor had been converted into a studio, with a big sound system, nice monitors and multiple microphones. Here we transformed Woodie Alan into a real band, ironing out the details of six new songs and transforming “Beijing Blues” from lyrics atop a blues progression into a real composition, which quickly became out theme song.

I offered Zhang Yong a lift home one night after a late rehearsal. As I started up my van, the sound of prime Allman Brothers boomed through the stereo. I always loved the sensation of blaring uber-American music while driving through China and had been listening to a vintage recording at high volume on my way there.

Zhang Yong’s face lit up when he heard “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” a monumental instrumental penned by guitarist Dickey Betts, whom I had interviewed many times.

“This is the Allman Brothers,” I said in Mandarin. “Do you know them?”

“No, but I like,” he replied in halting English. We listened without speaking for A few minutes as the music washed over us—utterly familiar to me, amazingly fresh and foreign to him, even though it was almost 40 years old.

“Two drums?” he asked.

“Dui.” (Correct.)

“Two lead guitars?”

“Dui.”

I clicked ahead to “You Don’t Love Me,” an original take on a traditional blues, with Gregg Allman’s whiskeyed blues vocals leading into inventive guitar soloing. He was listening intently, astounded by what he was hearing.

Zhang Yong

Next up was the sweet, country-tinged “Blue Sky,” with Betts’ high, lonesome vocals leading into one of my favorite guitar solo sections in all of rock, as Betts and Duane Allman take flight separately before swooping back down to hit heavenly harmonies. Zhang Yong turned to me, grinning madly.

“Wow. Good! Different band?”

“Bu shi! Yi yangde!” (No, the same!)

“Oh wow. Two singers!”

We listened without speaking for a while, then he simply said, “Oh, so good.”

Photo – Sidney Smith, 1970

It would be unthinkable to come across an American rocker of Zhang Yong’s age and talent who did not know the Allman Brothers’ music, which had so permeated classic rock radio. Turning him onto it felt fantastic. My musical connections with my Chinese bandmates had been so easy and complete that I had forgotten about the vast differences in our backgrounds.

No wonder I had not been able to quite communicate what I wanted, or explain what I meant by “staying tight but loosening up.” I was trying to describe the Allmans’ music. It was grounded in the blues and built around perfectly executed riffs and licks, but the solos headed off on wild rambles, always managing to parachute right back onto the riff. That was the kind of approach I wanted us to take.

I burned three CDs of my favorite Allman Brothers tracks and handed them out at our next gig. A week later, Zhang Yong came to rehearsal and started playing and singing “Statesboro Blues,” one of the Allmans’ best-known songs, written 80 years ago by Georgia bluesman Blind Willie McTell.

“He wants to do this song,” Woodie said.

“Statesboro Blues” made the transition from 1928 Georgia to 2008 Beijing with ease and we worked it up as a duet with Zhang Yong singing the first two verses and me taking the last two. Woodie also immersed himself in the Allmans music, altering his entire conception of what he could with the lap steel guitar. “I need to take it further,” he said. “Now I hear all the possibilities of the instrument.”

Woodie was inspired by The Allmans’ young guitarist Derek Trucks, whom I knew well, having written many stories about him, starting when he was a 12-year-old prodigy. Seeing Trucks perform with Eric Clapton in Shanghai had inspired me to want to play with Woodie, who has now being inspired by his brilliant playing. And the Allman Brothers, who had ignited my love for music, were now inspiring my Chinese bandmates. There was some sort of poetry at work here.

Excerpted from Big In China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising A Family, Playing The Blues and Becoming A Star in China (Harper). Copyright 2011 by Alan Paul.

July 18, 2017

Preview 3 songs from Lukas Nelson and the Promise of the Real

Lukas with Gary Clark Jr.

I saw Lukas Nelson and the Promise of the Real at a showcase show at the Mercury Lounge last month and I thought it was fantastic. I was as excited by an artist whose material I didn’t know as i have been in a very long time. They have an album coming out August 25, which you can preorder by clicking here.

I interviewed Lukas for Guitar World, so I’ll save more thoughts on him for that story, but you can listen to three songs from the album below. I think the vocal similarities between Lukas and his pops Willie Nelson will be pretty clear, as will the band’s groove and Lukas’ conversational, swinging guitar leads.

July 11, 2017

Reflecting on 25 Years of Interviewing Gregg Allman

The surprising secret at the heart of Gregg Allman’s blues-rock music: He was really a folkie soul singer.

Photo – Derek McCabe

I wrote this personal reminiscence of Gregg Allman for Billboard. Re-posted here exactly as it ran.

The news of Gregg Allman’s death got me listening to his music on repeat. In that regard, today isn’t much different than any other day — just more so.

It’s hard to describe how much Gregg’s music has meant to me, as both a fan and a journalist who interviewed him dozens of times over 25 years. For me as for so many, Gregg and The Allman Brothers Band weren’t background music, and they weren’t a passing fancy. They were a touchstone to many of our lives’ happiest and saddest moments, and thus his loss resonates profoundly, like the loss of a family member.

Gregg’s easy mixing of folk, blues and rock, genres that don’t usually go together is one of the hallmarks of his music. “A certain side of me has always viewed myself as a folk singer with a rock and roll band,” Gregg told me in 1995. “I developed that perspective when I lived in Los Angeles and saw people like Tim Buckley, Stephen Stills and Jackson Browne, who was my roommate for a while. All I had known was R&B and blues and these guys turned me on to a more folk-oriented approach and it’s always stuck with me, even if a lot of Allman Brothers fans never realized it.”

Most people don’t associate Gregg with California singer-songwriters but you could hear that love of folk rock in songs like “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” and in solo numbers like “Multi Colored Lady.” Gregg was not afraid to be vulnerable, to write and sing lyrics like “Come and Go Blues” that admitted to feeling lost, betrayed, heartbroken. Even “Whipping Post,” one of his most swaggering tunes, was rooted in a heartbreak and pain so profound that good Lord, he felt like he was dying. He sang the words night after night for 45 years, with a passion that connected with people because he embraced, rather than camouflaged, his pain. When he sang you heard his father being killed when Gregg was a toddler, and his father figure, big brother Duane, dying just before his vision of the Allman Brothers Band conquering the world came true, way back in 1971.

Photo – Sidney Smith

I interviewed Gregg dozens of times between 1990 and 2015 and I never quite knew what I would get. He could be thoughtful, funny and incisive, a fantastic storyteller and jovial presence, and he could be curt, just getting the job done. That’s not surprising for someone who spent a good chunk of his life picking up the phone to call reporters to advance a single show in Des Moines, Greenville or Irvine.

In 2013, I interviewed Gregg for the Wall Street Journal as he was promoting his memoir “My Cross to Bear.” It did not start out well. He was giving yes and no answers and I was scrambling to pull more out of him in our limited time. About ten minutes in, someone came to my front door and my little dog Meimei, resting at my feet, jumped up and started barking like a banshee. I was mortified, but Gregg was delighted.

“Hey!” he exclaimed with 1,000 times more enthusiasm than he had displayed prior. “You’ve got a little kitty, too? What is she?”

“A morkie, I think. She’s a rescue dog. What do you have?”

And then Gregg went off in a rapture about his two dogs, one of whom was also a morkie, and how much he spoiled them. I knew all this, having seen him with his beloved dogs over the years.

“Gregg, I actually use you as a defense whenever someone makes fun of me having a tiny dog,” I told him, quite truthfully. “If they say it’s not manly, I just go ‘Gregg Allman has two of them!’”

Photo – Kirk West

He chuckled. “I used to have giant dogs, even a St. Bernard once. I loved that dog! But you know who turned me onto little dogs? B.B. King. He told me, ‘You don’t know the love of a dog until you’ve had one who can sleep in the nook of your elbow.”

Now I had even better backup when someone made fun of my little pooch! B.B. King told Gregg Allman it was the way to go. Our interview resumed with new vigor and insight.

In 1997, I interviewed Gregg at 2 am in his Chicago hotel room after he played a solo gig at the Hard Rock Café. His then-wife Stacy and their two dogs were asleep behind us. It was a cover story for Guitar World Acoustic and I had brought an axe for him to demonstrate his finger-picked riff to “Come & Go Blues.” I handed it to him at the end of the interview, which had gone exceedingly well. It was the most relaxed, open conversation we ever had, by a long shot, which set the table for what came next.

He asked for a quarter and rounded off a couple of string ends. “You trying to take out my eye?” he inquired with a laugh. Then he re-tuned the guitar to an open tuning, took out a pouch with metal fingerpicks (which he put on) and showed me the riff, talking the whole time about how he was inspired to play in such a manner by Tim Buckley. Then he kept going, and he played and sang all of “Come & Go Blues.” Audience of one.

2009 – by Rayon Richards

It was an otherworldly experience, a moment where time and space were suspended and I was just right there. In that regard, it was just a heightened version of what millions experienced listening to Gregg for the last 50 years.

People talk about the concept of a musician having soul as if it were a phenomenon too complicated to grasp or explain. It is not. A performer has soul when he or she plays music because they feel compelled to do so, when he or she feels as if it is coming from another place and passing through them. Music has soul when it reminds listeners that they have one by stirring something within them, touching them somewhere deeper than their head. Music with soul doesn’t just entertain — it speaks. And it doesn’t just speak; it has something to say.

Gregg Allman had soul. Listening to him sing, you heard not just words or one-dimensional emotions, but determination, suffering, longing and love. This was in every note Gregg sang and played, because what he did is who he was. Gregg’s music was his life, his therapy, his means of expressing sadness and joy, of screaming in pain and gasping for breath. There was no wall between the artist and the art; everything he had went into his music, and the listeners understood that, even if they didn’t know it.

Alan Paul is the author of the New York Times best seller, One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band

July 10, 2017

Eric Krasno: center of the jam universe

Last year I profiled Eric Krasno for Relix magazine. Here’s the story. Amazing how much good music Eric has been in the middle of. He’s paying tribute to Gregg Allman and the Allman Brothers Band with Scott Sharrard and others this week at Irving Plaza.

Trying to keep up with Eric Krasno for a single night of the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival was an exhausting experience. Around 8 pm he walked off the outside stage of the FIYA Fest, after an exhilarating set with Dr. Klaw, featuring Cyril Neville, Nigel Hall, Adam Deitch and Dumpstaphunk’s Ian Neville and Nick Daniels. As he chatted with friends and wiped sweat from his face with a towel, a Fiya staff member grabbed Krasno’s arm and gently nudged him away. He had to get inside to the larger stage, where his Soulive bandmates were waiting and would soon start a funkified set with James Brown sax man Maceo Parker. When that ended at 10:30 pm and a sweaty, enervated crowd drained out, Krasno had some brief chill time backstage, before heading back to his New Orleans digs to rest for a while.

He was preparing for the day’s final gig – or the next day’s first – taking the stage at 2:30 am in the French Quarter with Oteil Burbridge, Deitch, Hall and special guest, jazz trumpet master Nicholas Payton. Kofi Burbridge and Neal Evans would also drop by for a mind-bending night of music. For at least one observer stumbling out into the street as daylight approached, it was an exhausting and exhilarating musical adventure. Krasno kept up the same pace for two weeks. And these manic New Orleans days are but a microcosm of his life and a metaphor for his career; Krasno seems to be everywhere.

As a guitarist, producer, bandleader, songwriter and entrepreneur, it often seems there are few corners of the musical world he hasn’t touched in recent years. He’s best known for playing with two bands, Soulive and Lettuce, for almost 20 years. But he’s also made his mark as a producer, label owner and guitarist for a wide range of artists, from soul legend Aaron Neville to melodic crunch duo the London Souls – both of whom record for Krasno’s Feel Records. He has also played frequently with Phil and Friends and, more recently, Billy and the Kids. He has written songs for the Tedeschi Trucks Band – with whom he also toured as a fill-in bassist in 2013 – and recorded with The Roots, Talib Kweili, Redman, Pretty Lights and 50 Cent.

Lettuce drummer Adam Deitch sums up why his longtime friend and collaborator can slide seamlessly into so many projects: “He’s a quite awesome person that people love to be around.”

Krasno is releasing a solo debut, Blood From A Stone, on July 8 on Feel. It will be followed by the Eric Krasno Band’s first tour this summer and fall. The album features appearances by Derek Trucks, as well as members of Soulive, Lettuce and The London Souls, but the focus is squarely on Krasno: his songs, his playing, and for the first time, his singing.

“I’ve been writing vocal songs for other people to sing for a while and I always sang on the demos,” Krasno says. “And when we first started this project I thought I might do the same thing – bring someone else in to sing my parts, or maybe a bunch of different people. But as work on the album went on, I thought more and more that I should sing it all myself and I really worked on it. Every time I play a show or sing live, I get better and more comfortable.”

The core of Blood From A Stone began several years ago during a Maine writing session Krasno had with Dave Gutter of the band Rustic Overtones.

The core of Blood From A Stone began several years ago during a Maine writing session Krasno had with Dave Gutter of the band Rustic Overtones.

“I went up to Maine and within a day we had three or four songs that ended up on the album,” says Krasno, sipping a beer in a bar around the corner from his Greenpoint, Brooklyn apartment. “We were being so productive that we set up a studio in a barn and Chris [St. Hilaire, London Souls drummer], Stu [Mahan, bass] and Nigel [Hall, keys] came up to demo the songs and most of them ended up being on the record.”

After those initial sessions, Krasno continued to work on the solo between his other projects. “I was so busy with different things,” says Krasno. “I held onto a few of those tracks and ideas and worked on the album off and on for a few years.”

When he found himself not quite able to put the finishing touches on the album, he hooked up with Jeremy Most, who has worked with Emily King, Ed Sheeran and others. Most added some instrumentation and became the co-producer, adding a more modern, minimalist touch to the collection of blues and jazz influenced tunes.

“I’m usually the guy getting things done and pushing other people’s albums along and I needed someone to help me with that,” says Krasno. “I loved Jeremy’s production on the Emily King albums. We reconnected after one of their shows and I played him the music. He loved it and had some ideas right away, which was really welcome. The flight was almost there, but I couldn’t land it and he helped me bring it in.

“I liked the tracks but they didn’t feel like an album and Jeremy helped me zone it in and make some decisions about which tracks fit together and made for a cool journey. You want an album to sound cohesive but not for every track to sound the same.”

The album’s long gestation gave Krasno a chance to grow into the music, to adapt it and to be more ready to take the material on the road as a singing frontman. “I’m really ready and very excited to go out and do this now,” he says. “For years, I was more used to playing jazz and funk, mostly instrumental and jam-based, and I’ve gotten more and more into performing songs.”

Krasno’s love of more song-oriented performances grew during his summer-long stint as Tedeschi Trucks Band bassist, in between Oteil Burbridge’s departure and Tim Lefebrve’s arrival. He thrilled to hearing crowds singing along, especially to the four songs he co-wrote on TTB’s Made Up Mind. His subsequent performances with Billy and the Kids and Phil and Friends, playing the beloved Grateful Dead repertoire to appreciative audiences furthered the feeling.

“I love jamming and being improvisational – and the Jazzfest shows are the mecca where we try to see if we can take that vibration to another level,” says Krasno. “You also do that performing with the Grateful Dead camp, of course, but with them it all starts with the songs, which is very apparent when every tune becomes a spirited sing-along. And everyone in my band is going to be singing, which is something I learned to love from playing the Dead music – all those harmonies! – and missed in my other bands. I grew up on that music so I’m kind of excited to make a full circle back to where I actually began.”

Krasno traces his own musical awakening to seeing the Dead and Allman Brothers as young teenager and hanging around his brother Jeff‘s band in their family basement. His career began almost as early. At 16, the Connecticut native attended a summer program at Boston’s Berklee School of Music, where he met the core of what would become Lettuce: Deitch, guitarist Adam Smirnoff, bassist Erick Coomes and saxophonist Ryan Zoidis. Thrilled to find like-minded peers, the group jammed their summer away and pledged to return together in two years, a promise they remarkably all kept. A year later, Krasno transferred to Hampshire College, in part to study with jazz saxophonist Yusef Lateef. Lettuce kept playing together, but during a pause while most of the other members were in the funk/hip hop group Fatbag, Krasno joined up with brothers Neal and Alan Evans in Soulive. Even as that band began to pound the touring circuit and record, Krasno remained in touch with Lettuce, which continued performing whenever possible.

“Kraz is the godfather of the crew and has always been the guy who helped everyone out all the time,” says Deitch. “None of this would have happened without him.”

Krasno may have been born into his role. His grandfather Lou Krasno was a renowned klezmer and gypsy jazz violinist who fronted a group called the Gypsy Gems. His father Richard, a PhD educator, is a skilled musician who was a DJ in late 60s San Francisco. His uncle Ron Kaplan was a Chicago bass player who became a booking agent, working with Buddy Guy, Herbie Hancock and others and was very involved in helping Lettuce and Soulive grow in their earliest days. And Jeff Krasno managed both Lettuce and Soulive and started Velour Recordings, which released the band’s albums.

“For a good while Kraz was the only one who understood how to book Lettuce, how to get us shows, how to get paid,” says Deitch. ”We were all about showing up and handling the music part, but at first he alone saw the other side of this. He’s inspired all of us to be better businessmen – to be better at handling all the other stuff beyond the notes.”

Deitch says that everyone’s respect for Krasno and their long-term friendships eased the pain when the guitarist announced he would no longer be appearing at all Lettuce shows; he now appears with the band at select dates.

“I just decided that I really wanted to push Lettuce and give it a fair shot,” says Deitch. “Everyone was on the same page, except Kraz, who was like, ‘I appreciate what you want to do’ but I need to do something else.’ He’s a very good communicator in terms of both friends and business. We totally understand what he wants to do and as friends, we support him.”

Warren & Eric. Photo – Jeremy Gordon

While Krasno is preparing to release Blood From A Stone and hit the road with his solo band, don’t expect his focus to become singular. Soulive and Lettuce aren’t going anywhere. He will keep performing with Lesh and Kreutzmann and popping up in jams more often than Smuckers. He’s also producing a movie in New Orleans, Take Me To the River, Volume 2, which focuses on the city’s rich musical heritage and bringing some of the city’s rock and soul legends together in collaborations with younger musicians and mcs.

Krasno’s ability to remain both musically restless and ever focused and calm is impressive and reminiscent of Warren Haynes, with whom he shares a management team and a mutual respect.

“Eric is one of those cats who has a good vibe and adapts well to different settings,” says Haynes. “Moving across genres as he does starts with having a reverence for so many different approaches – being truly moved by different types of music and studying what makes them tick. In order to be convincing in a lot of different settings you have to have passion for them all and study them more than just a little bit. You have to go deeper and have that be reflected in your own voice. It’s really kind of a rare quality and something Eric clearly possesses.”