Alan Paul's Blog, page 16

January 25, 2017

RIP Butch Trucks, 1947-2017

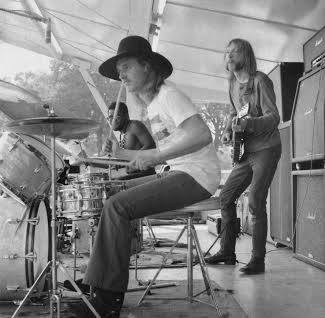

Butch had the fire until the end.

Claude Hudson “Butch” Trucks (b. May 11, 1947, d. January 24, 2017)

It’s with a very heavy heart that I report the death of Butch Trucks, drummer, founding member and bedrock of the Allman Brothers Band. I am stunned to be writing these words, having communicated with Butch several times in just the past few days. My fingers are frozen just looking at the top of this page and seeing the words pouring onto my screen

Butch was devastated and angry about Trump’s election and had vowed to live at his house in the South of France throughout the new president’s term, but I doubted his resolve because he loved his grandchildren too much; I watched him light up with joy holding his new grandson at last summer’s Peach Festival. He was also very excited about playing with two bands: his Freight Train Band and The Brothers, recently renamed from Les Brers, featuring his Allman Brothers backline mates Jaimoe and Marc Quinones, as well as former ABB members Jack Pearson and Oteil Burbridge, plus Pat Bergeson, Bruce Katz and Lamar Williams Jr.

Tulane homecoming 1970 – Sidney Smith

To the end, Butch remained an incredibly powerful and melodic drummer whose parts defined the Allman Brothers’ classic songs as much as any guitar riff, bassline or vocal. I was on the road with Les Brers last fall and they put on excellent shows. I can barely find the words to describe my own joy at standing alongside Butch, Jaimoe and Marc again; it was like coming home to something very special and indescribable. It was a physical sensation as much as anything; something I felt deep in my bones and which gave me a feeling that I couldn’t have known I missed so much until I felt it again. I wish every one of you could have watched an Allman Brothers show from the side of this percussion powerhouse. It was an overwhelming experience and one that helped you understand the very deep, profound impact the drummers had on the greatness of the music.

Butch and Duane, Piedmont Park Atlanta, 1969.

Butch was irascible. He could be grumpy. He was also very bright, well versed in all manners of things. And he delighted in talking about it all. In March 2015 we spent a lot of time together over one weekend when he was doing some events in New Jersey and I drove him around while we talked in depth about anything and everything. I heard some wild Allman Brothers stories for the first time; maybe he figured they were safe to let out now that the book was done!

Bothers forever. Photo by Derek Trucks during final Allman Brothers band rehearsals, October 2014.

He came to my house for breakfast with my family in great spirits and was extremely kind and gracious to my wife and children. He also engaged my Uncle Ben, Dartmouth grad and retired judge, in an in-depth conversation about their shared passions for philosophy and physics. He was impressed that my then 17-year-old son Jacob knew his philosophers and that made me very proud. Later that afternoon, we did a talk together at Words, Maplewood’s bookstore and owner Jonah Zimiles was wowed. He later told me that Butch was his favorite guest ever – and the store has hosted a cavalcade of literary stars.

My relationship with Butch first deepened over a book – and it wasn’t One Way Out. He reached out to me in 2011 after reading about my memoir Big in China in Hittin the Note magazine. He was fascinated by my story about playing music in China and our relationship deepened. Throughout the writing of One Way Out, Butch answered my phone calls and emails consistently and quickly and was always ready to share an opinion or memory. He was, in short, an invaluable resource – and he immediately agreed to write a Foreword when I asked. Then he almost as quickly wrote it by himself, straight through, and it ran with very little editing. That’s not how celebrity Forewords and Afterwords usually happen.

in Hittin the Note magazine. He was fascinated by my story about playing music in China and our relationship deepened. Throughout the writing of One Way Out, Butch answered my phone calls and emails consistently and quickly and was always ready to share an opinion or memory. He was, in short, an invaluable resource – and he immediately agreed to write a Foreword when I asked. Then he almost as quickly wrote it by himself, straight through, and it ran with very little editing. That’s not how celebrity Forewords and Afterwords usually happen.

Paul family breakfast with Uncle Butchie.

Butch played with Duane and Gregg long before the Allman Brothers Band formed in March 1969. The brothers briefly hooked up with Butch’s folk rock band The 31st of February and recorded an albumin Miami that Vanguard Records rejected. It included the first properly recorded version of “Melissa” as well as “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg’s moving tribute to Martin Luther King Jr. Musical history may have been written differently if Gregg had not flown back to Los Angeles and learned that he was still contractually bound to Liberty Records. Duane moved on to Muscle Shoals and began establishing himself as a session musician.

Eventually, Duane would appear at Butch’s Jacksonville home. He wrote in his Foreword to One Way Out:

“…there came a knock on my door and there was Duane with an incredible-looking black man. Duane, in his usual way, introduced us to each other as Jaimoe, his new drummer, and Butch, his old drummer…. He left Jaimoe at my house and, for the first time in my middle class white life I had to get to know and deal with a black man. It changed me profoundly. Over forty four years later, Jaimoe and I still best of friends and I am very proud to call him my brother.”

Three drummers – by Kirk West

Over the last four years, Butch established a wonderful, warm family vibe at his Roots, Rock Revival Camp near Woodstock. It was his baby, and Oteil as well as Luther and Cody Dickinson were the other core counselors Bruce Katz, Bill Evans, Roosevelt Collier and others also were involved. I attended the first two and they were fantastic. It’s hard to over-state what he created up there: a small but growing and fiercely loyal band of brothers and sisters.

Trucks is the third founding member of the Allman Brothers Band to leave this mortal coil and the first since Berry Oakley in 1972. Founder and guiding light Duane Allman died in 1971, of course. You either understand how I feel right now or you don’t. If you do, I offer a digital hug of brotherhood. I send my deepest condolences to Melinda, Elise, Seth, Vaylor, Chris, Duane, Derek, Melody and all other members of the bountiful and wonderful Trucks family. Condolences go out also to the entire extended Allman Brothers Band family. It’s a sad, sad day in our little world, friends.

Any media members are free to quote at will from the obituary as long as you promise to not say that Derek Trucks was Butch’s son. He is his nephew!

January 24, 2017

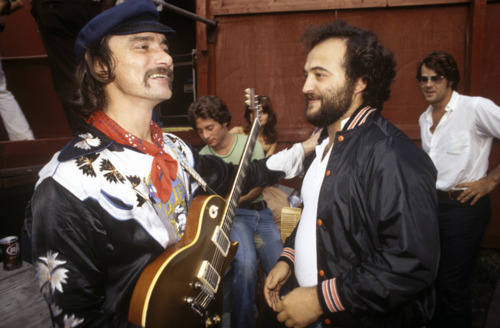

John Belushi jamming with the Allman Brothers

Photo: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns

John Belushi would have been 68 today. On 4/20/79, he joined the Allman Brothers onstage at the Capitol Theatre, Passaic NJ for “Hey Bartender.” Check it out:

January 23, 2017

Rich Robinson

In honor of the debut last weekend in four shows of The Magpie Salute, featuring Rich Robinson with several Black Crowes alum, including guitarist Marc Ford, I present...

The GW Inquirer with Rich Robinson – from 2004, as he was releasing his first solo album, Paper.

You just released your first solo album, Paper. Is this something you’ve always wanted to do?

No, I only started working on the material after the Crowes were no longer playing together. I felt content writing music for the guitar but now that I’ve done it I have a whole new perspective on songwriting. Writing from a total hole is a lot different than working with my brother where I’ll write the music and he’ll write the lyrics. It’s cool having something come totally from me.

You also produced the music. Was it intimidating to be in the studio all alone?

No. I’m really comfortable in a studio; it’s like home. We cut the album much like we recorded many Crowes songs – with me and the drummer going in together and laying down basic tracks, then adding everything else. Except I was doing most of the adding myself – playing bass, lead guitar, keyboards and percussion, plus singing.

There are a lot of rumors that the Crowes will be back together soon.

Chris and I are brothers and we’ve spoken about it and both feel good about the idea, but there are no plans right now. He has a baby, which is my first nephew and we’ve been spending time together and we’re getting along great, so the door is definitely open.

What do you think was your best gig ever?

Two stand out and both were because of the overall experience. Once, we played with Dylan and the Stones in the South of France and it was unforgettable. We did a great set, then stood on the side of the stage and watched Dylan blaze through “Tangled Up In Blue” and a fantastic show. Then the Stones came out and tore it up, with Bob sitting in. The other was in Breja, italy, outside of Milan, where we played with Neil Young in the town square on a beautiful summer night. Dylan came out to see Neil play and hung out on the side of the stage next to us and Neil just tore it up with Crazy Horse.

How about your worst gig?

We played Russia in front of a half a million people and everything about the gig was bad. We had gear malfunctions but more importantly there was just a really bad vibe to the whole thing that freaked us out. There were 40,000 Russian troops beating the shit out of people and we found later that 11 people died and many people were raped. It was just insane and horrible.

What inspired you to play guitar?

AC/DC. I loved Angus and Malcolm and started messing around with my dad’s guitar, which was 50s Martin D28. to get me away from it, he I bought me a Lotus Strat copy and my brother a bass , with one Peavey bass amp for us to play through. It sounded really loud and shitty, but it was awesome. The minute we got them Chris and I ere floored and we started writing songs almost immediately.

January 17, 2017

Oteil sits in with Tedeschi Trucks Band

How nice to see Oteil Burbridge back on stage with the Tedeschi Trucks Band for a song last weekend at the Sunshine Blues Fest in Boca where Oteil now lives. They played Leon Russell’s Space Captain. Check it out:

Setlist: Tedeschi Trucks Band | Sunshine Music Festival | Boca Raton, FL | 1/15/17

Set: Anyhow, Don’t Know What > Keep On Growing, Within You Without You > Just As Strange, Crying Over You, Let’s Go Get Stoned, Feelin’ Alright#, Leavin’ Trunk**, Volunteered Slavery**, I Wish I Knew, I Pity The Fool, I Want More > Soul Sacrifice

Encore: A Song For You, Delta Lady, Space Captain++, With A Little Help From My Friends

# w/ Dave Mason

** w/ Luther Dickinson

++ w/ Oteil Burbridge

January 14, 2017

Gregg Allman’s tribute to Martin Luther King Jr.

Photo – David Oppenheimer

Every year on MLK Day I share “God Rest His Soul,” Gregg Allman’s beautiful tribute to Dr. King, which he wrote and recorded in 1968, shortly after the assassination.

Gregg Allman wrote this song for Dr. King but it was never on any of his proper releases. He’s said that he never intended to release it and just wrote it as a personal tribute, but he also sold the song for way too cheap to producer Steve Alaimo when he needed money to get back from Florida to Los Angeles. Alaimo also bought “Melissa,” which ABB manager Phil Walden eventually bought back 50 percent of… There are multiple versions of it, and this is not my favorite but I think it’s a great tribute to a great man and the person who put this video together with pics of Dr. King did it justice, though he misidentifies it as being The Hourglass. This tracks was actually cut with Butch Trucks’ The 31st of February and produced by Alaimo.

As always, I think it’s important to remember that when Dr. King was assassinated he was in Memphis marching in support of striking garbage haulers. I’m sure many of those striking men could have and would have done a lot of other things had they had the opportunity to do so. It bothers me that we have garbage pickup today. Let’s not allow MLK Day to become another excuse for sales.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop” is below that. Unbelievable.

MLK’s haunting final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop”:

January 11, 2017

Phathers and Sons: Trey Anastasio Meets Phil Lesh

Photo – Jay Blakesberg at Shoreline

I compiled my best Grateful Dead-releated journalism in an Amazon Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead. This interview with Trey Anastasio and Phil Lesh is one of the greatest, most unique stories in there. I wanted to share it with you. I was inspired to do so by my friend Jay Blakesberg posting the photo above on his Facebook page.

Phathers and Sons

The Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh and Phish’s Trey Anastasio have only done one interview together. This is it.

The following interview – the only one that I know of with both Phil Lesh and Trey Anastasio – almost never happened. I started contacting Anastasio and Lesh in April, 1999, following the very first Phil and Friends shows, featuring Anastasio and his Phish bandmate Page McConnell. Trey quickly signed on and we targeted Phish’s two-night September appearance at Shoreline Ampitheatre in Lesh’s San Francisco Bay Area.

Phil was a lot harder to nail down. Phil and Friends was a new entity, lacking the normal structures of management and publicity. I got a name from someone as Phil’s contact and emailed with him about this interview for months. He thought it was a great idea and Phil and wife/manager Jill seemed to agree. But I couldn’t get any commitment and my contact finally told me that he wasn’t really a publicist; he was the father of a kid on Lesh’s son’s Little League team who had been helping Phil out. He was as frustrated as me.

Somehow, we pushed through all this; Lesh agreed to come to Shoreline at 5 pm on September 17, 1999, the second of two Phish shows. Phish sent a limo to pick up Phil and Jill and deliver them. I hung out at Shoreline all afternoon, growing excited. However, 5 pm came and went and no limo and no Lesh. Pre-cell phone, no one knew where he was or when he would arrive. They showed about an hour before showtime and Anastasio politely said he couldn’t do it so close to curtain, though I did nudge everyone into the photo with Jay Blakesberg that you see above.

Phish management kindly sat me in a box with Phil and Jill, and we had a nice chat. I recommended Jimmy Herring to him and while I’m sure I wasn’t alone in that, I like to think it played a part in the gig that would soon come the guitarist’s way. 9-17-99 was about to become a well-known day in Phish history, because by the second set Lesh had left our box and was walking on stage with the band. He played “You Enjoy Myself ” ,” even jumping on a trampoline, and stuck on stage for an extended jam, “Wolfman’s Brother” and “Cold Rain and Snow.” Warren Haynes joined Lesh and Phish for an encore of the Dead’s “Viola Lee Blues.”

It was an epic night of music, but I was crestfallen. I had come a long way for an interview that just didn’t happen. Both Lesh and Anastasio promised to see it through, but I doubted we would ever clear the logistical hurdles. I kept in touch with everyone and about seven months later, when Lesh and his Friends – now including Herring – played six nights at the Beacon Theatre in April, 2000, Anastasio traveled to New York. We rented a hotel room and sat down to talk the afternoon before a Lesh performance. Lesh had opted to keep touring with this band that spring and summer rather than join his ex-Deadmates in The Other Ones and was quite open about his preference to being in charge. Versions of the interview ran in Guitar World and Revolver magazines. It has never appeared in full before now.

•

Sitting across from each other in a New York hotel suite sipping coffee and San Pellegrino water, Phil Lesh and Trey Anastasio don’t look or sound anything like the once and future Kings of psychedelic rock. There is no day glo or tie dye to be seen. No dilated pupils. No muddled, Santana-esque raps about angelic visions.

With Central Park shimmering outside the picture window, the bespectacled pair looks more like father and son tourists preparing for a day on the town. At 60, the tall, angular Lesh is clean cut and fit-looking, remarkably so for someone less than two years removed from a life-saving liver transplant. The uninformed observer certainly wouldn’t guess that they were looking at Jerry Garcia’s right hand man. With his scraggly beard and unkempt hair, Anastasio is more disheveled, though there is still little to indicate that the Phish frontman is the shamanistic Pied Piper for a new generation of youth looking to turn on and tune in.

Appearances be damned, these two have been smack dab in the middle of some of the most exploratory rock and roll played for the last 35 years. In many ways, Anastasio’s Phish picked up where Lesh’s Dead left off following Garcia’s 1995 death, building a huge and rabidly dedicated following through hard touring, word of mouth and fanatical tape trading.

There is such a natural affinity between the bands that one might assume that their relationship stretches back for years, but it does not. Anastasio and Lesh first met two years ago, when Phil enlisted the guitarist and his bandmate, keyboardist Page McConnell, for three San Francisco performances. These shows, in April 99, were of particular significance because they marked Lesh’s remarkable recovery from his transplant. Lesh has since plunged headlong into the solo career he largely shunned during the Dead’s life, turning his back on his former Deadmates in The Other Ones to perform with his Phil and Friends.

“Phil faced down death and came out the other side and has basically decided to do exactly what he wants with no compromise,” says guitarist Warren Haynes, who has played with Lesh frequently and has become close with him. “That means a band which maintains the Dead’s improvisational quality, while also being more structured.”

Phish, meanwhile, has taken an extended hiatus, which will last at least one year, following over a decade of relentless touring. Just before the band’s final pre-break tour, Anastasio leapt at the opportunity to pick the brain of one of his musical heroes.

“I welcome any opportunity to sit and talk with Phil, which was one of my favorite things about playing with him,” says Anastasio. “Anyone who really cares about music can learn a lot from this man.”

TREY ANASTASIO: Phil, our experience playing with you last year was incredible for many reasons. But rehearsal was my favorite part. I really enjoyed the chance to spend so much time talking to you about music and the history of the band and just realizing that as legendary and great as the Dead was, it was also just a band with all the usual dramas and personalities. And on a simpler level, we rehearsed long and hard – eight hours a day! – and I love to do that.

PHIL LESH: I love to do it too, especially because we didn’t do much of it for an awful lot of years in the Grateful Dead.

ANASTASIO: But you must have done it for a while.

LESH: Yeah, and I loved it when we did. The first few years we played together all day, every day, no matter what, so we just got to know each other incredibly well. It trailed off in ’74 and after we took that break in ’75, that was pretty much it for rehearsal.

ANASTASIO: That’s really interesting. We’ve been slowing down on rehearsing a lot, though not really in a planned way.

LESH: Yeah. Life interferes with your schedule by intruding on that little hermetic environment. I think it’s an evolutionary process, where after a certain period of time you’ve done your woodshedding and you know each other well enough that maybe it’s not going to get much better. Maybe putting all that work and time into it isn’t going to really produce much in the way of results.

ALAN PAUL: Yet you seem happy to be rehearsing vigorously again. Was that ever a source of tension in the Dead?

LESH: Only subconsciously. The group mind was pretty much in accord in many ways, all the way through. I mean individuals have their own preferences, but the group mind really ruled, so after a while you give in to that. [laughs]

Almost 20 years later… Fare Thee Well. Photo – Jay Blakesberg

ANASTASIO: One of the things that will always put the Dead in a completely unique position is that you guys charted more new ground than any other rock band. You broke down boundaries and took influences from things like bluegrass and jazz at a time when there were no books written on how to do that. Whereas we could weigh the good and the bad, and decide what worked and what didn’t.

LESH: Well, you take what you need and you leave the rest. [laughs] Artists have always done that, so it’s not new and it’s not wrong.

ANASTASIO: Maybe it’s even more than that. I feel like there is an active second generation of bands right now and we can learn a lot from your successes and failures. I saw CSNY recently and spent the night talking to those guys afterwards. The first thing Graham said was, “Congratulations on your success. Don’t fuck it up.”

LESH: That sounds like something Nash would say. [laughs]

PAUL: So, what can you proactively do to make sure you don’t fuck it up?

ANASTASIO: I haven’t thought of anything specific and that’s what worries me. [laughs] Phil?

LESH: First, it has to be apparent that you’re fucking up, and that’s the hard part. Hindsight is easy. Musically, the quest never ends. Music is an infinite process, and that’s what holds the attraction. You’ll never get to the end of it, so you can never be bored with it. That’s why playing with so many different people after playing with the same ones for so long has been revelatory. I learn from every musician that comes through this band.

We have gone places that the Grateful Dead never went. My vision for the Dead was always group improvisation and movement and instrumental passages but not solos – not one person stepping out. Now this is my band and I can try to make it happen just as I always wanted, so it’s been liberating.

ANASTASIO: That brings up the concept of intent, which was the biggest thing I latched on to about the Dead. The intent behind a song always seemed to be about touching an emotion. It didn’t have anything to do with selling records. It didn’t seem like somebody sat down and tried to think out a hit song.

LESH: Oh, no. We couldn’t do it. In fact, we did try to write hit singles a few times, but it always came out sounding deformed. And that’s the way it goes when you try to do something like that.

PAUL: What is an example of such an attempt?

LESH: Actually, there’s only one instance to which I can concretely point, though I know there were others. It was when we were doing the follow up to our only hit single, “Touch of Grey” and the album In the Dark. We were recording Built to Last and we really thought “Foolish Heart” was going to be the next big thing, and worked on it with that in mind. But we did it in the weirdest way. We recorded a basic track, then everybody erased their parts and overdubbed.

ANASTASIO: Really? One at a time? Wow. Did you leave the drums?

LESH: Actually, I think we made the drummer play along with the other track. It was the most bass-ackwards kind of way to make a record. I don’t really know what we were thinking. It would be very hard to explain. And it just goes back to the fact that the payoff for the Grateful Dead was playing for people. We were a live band.

PAUL: For both of your bands, the concert experience is even bigger than the music.

LESH: Absolutely. The shows create a little sanctuary. You know that the world is temporarily reduced to this group of like-minded people. And it’s the same urge that brings people together in any situation, be it a poetry reading, a concert hall or a coffee shop. People have gathered together to hear music for as long as there have been people. We’re up there making music and singing songs, like telling stories around a campfire. That’s something both our bands share. Getting together like that is something as old as humans, and there’s a reason people have always done it.

PAUL: Fan tape trading has played an important role in the success of both the Grateful Dead and Phish. The notion of allowing — and even encouraging — people to tape concerts hardly raises eyebrow now, but when the Dead began doing so, the larger music world was shocked.

LESH: The tradition of taping Dead shows started in a very humble way. A fan simply asked permission to record one of our performances, and Jerry [Garcia] said, “After we play it, we’re done with it. Let them have it.” And everybody agreed. The group mind spoke through Jerry, and it turns out to have been the smartest move we ever made.

ANASTASIO: We did it from the start but again we basically learned from the Dead’s example and encouraged taping from the start. In our early days, we were able to tour the country with no record label solely on the strength of word-of-mouth and tape trading. That’s just one example of how much easier things have been for us, thanks to the Dead.

PAUL: What’s your view of fans downloading music via Napster and other Internet sites?

ANASTASIO: It gets more complicated when people download studio albums without paying for them, but I don’t believe you can stop it. My only answer is, I hope that the Internet spawns a new morality — one where people begin to develop a deeper respect for artists and their work, and voluntarily pay when they download music.

PAUL: Phil, as someone who lived through the Sixties—a time when many people dreamed of a new morality—do you think that’ Trey might someday have his dream become reality?

LESH: I’m not sure; it all depends on your ability to create a strong personal bond. Personally, I’m skeptical because I find communicating via the Internet to be distancing. I hope, however, that the ‘Net continues to be unregulated. We’ve seen the good it’s done in repressive regimes like China or Kosovo where people have been able to receive uncensored information by fax and the computer.

ANASTASIO: I don’t know if it’s going to happen, because it may well be co-opted by commerce, but the potential is there to put the power in the hands of the people. For people to instantaneously communicate with one another from anywhere.

LESH: That’s a righteous prediction, and it’s going to happen. The ecommerce is what’s going to drive the creation of the bandwidth and network that will give us instantaneous, lightning fast download of any artistic material, and media.

ANASTASIO: I’m a little more optimistic about Internet culture. The ‘Net has played a huge role in creating a community for Phish fans. One hundred thousand people came to see us play in a Florida swamp last New Year’s Eve, and as far as I know we didn’t buy a single word of advertising. Word spread on the Internet, and it sold out in advance.

But what was really incredible was the level of respect our audience had for the event. For example, there was no garbage left on the site. People knew from talking online that the show was held on an Indian reservation, so they cleaned up after themselves. At the end of the event the people had neatly stacked over 90 tons of recyclable trash. And the whole thing was done without involving the media in any way.

PAUL: Are either of you nostalgic for the activism of the Sixties?

ANASTASIO: I find it sad that when people reflect on that decade they tend to focus on things like pot and tie-dyes instead of the ideas that were being discussed. It was a time when people believed in change. Or so it seems from the perspective of someone who was three years old in 1967. Am I right, Phil?

LESH: Oh, yes. There were a lot of utopian dreams, and they were the foundation of everything we did. Everybody thought we really had a handle on things.

PAUL: It is widely believed that one of the things that undermined those dreams was hedonistic excess. Do either of you feel any dismay that drugs are a big part of the listening experience for many of your fans?

ANASTASIO: I certainly feel a responsibility for the overall safety and well being of everyone at our shows, but I don’t think we can control their actions. We can’t force them to be clean any more than we can force them to drive intelligently The decision to use a substance is a personal choice, and while I have had some positive experiences with drugs, I would never encourage anyone to use them. Phil and I both have kids, so I think we understand the danger in suggesting anything like that.

LESH: People have always tried to break down the barriers that hold them within their physical form. No matter what time we live in, or what legislation is enacted, people will continue to do this. Some of these drugs are sacraments, which open you up. Others are not. People who lie around and use hedonistic drugs are not the same people who do psychedelic drugs seeking to connect with a higher consciousness. It’s a basic human drive to know that there’s more to the world than meets the eye. That’s what religion is all about. Psychedelics are really a shortcut — ultimately, music alone can take you there — but I don’t think that makes the experience any less real.

ANASTASIO: That’s very true. Psychedelics didn’t ruin me. I’m a productive member of society and a good father of two great kids. The first time I ever took acid was at a Dead show in New Haven. It really did change my life and open up my mind; it was a pivotal experience. That doesn’t make me want to do it every day, but I certainly have no regrets because it really woke something up in me.

LESH: At various stages in your life, there are things that wake you up. My first encounter with music was like that. It’s why I became a musician, and it continues to this day.

PAUL: Because of the cult-like nature of your respective followings, both of you could easily release albums on-line exclusively. How does being on a major label benefit you?

ANASTASIO: Limos to drive you around when you come to New York, as well as free coffee and a conference room to do interviews in. Without them, you have to pay for the coffee. And, of course, they give us plenty of aggravation. But, to be honest, we have a good balance right now. We’re allowed to put out live albums via our newsletter or the Internet, and still put out albums on Elektra, so we’re happy.

LESH: The majors sure were sorry they signed us. We never paid off for them, and we did like to spend the money. I think we knew all along that the Dead was a band that played for the people. That was the payoff for us. The studio was a diversion, and we were never really good at it.

ANASTASIO: Oh, I disagree.

PAUL: What’s your favorite Dead studio album, Trey?

ANASTASIO: I have two favorite tracks: “Casey Jones” and “Shakedown” Street,” both of which have great, very unique basslines. I heard “Shakedown” on my car radio the other day and was overcome with how unique sounding it actually is.

LESH: When you hear, the Grateful Dead within a medley of radio songs, it sounds so different. It doesn’t sound like a radio song at all. We never figured out how to do that through 30 years. I still don’t understand how to do it. The few times we actually tried to make a hit single, it came out sounding rather deformed, not surprisingly.

PAUL: Well, that’s not quite true. After 20 years The Dead had a hit single in 1987 with “A Touch of Grey,” which paved the way for the band’s late-Eighties revival. Were you surprised by the song’s success, and how did it affect the band?

LESH: Yes, we were completely surprised, and its effects were dramatic. It brought in a number of young people who didn’t really have a feel for the scene and the ethos surrounding it, which was considerable after two decades. We were thrilled with the interest in the band, but it just stood everything on its head. More people wanted to see us, so we had to play larger venues. Playing in front of larger crowds resulted in a loss of intimacy, and for me the experience was all downhill from there. Of course, the decline might have happened anyhow, because after 22 years we were struggling creatively. We were just out there hacking away at it, and the new success actually made it easier to keep going, because it gave us more resources.

But it also inflated the whole organization. We had to fulfill all these obligations just to pay the bills, and that meant three tours a year plus weekends, and no chance to ever take a breather and get it together. This inflation seems to be the inevitable course of success.

ANASTASIO: Do you think a hit single would harm us – and our community? Some people think so, and it’s a big topic of discussion in our camp.

LESH: From my experience, I would have to say yes.

ANASTASIO: But, the thing is, I like hit singles! I always give people who can write them incredible amounts of credit.

LESH: Absolutely. In many ways, a hit single is the ultimate example of tapping into the zeitgeist of the time. They really are strokes of inspiration, because they have to be composed well before the moment they hit public consciousness. A great song that reflects what the masses are thinking and feeling is a function of true precognition. I also think a three-minute single may well be the perfect metaphor for this moment in history where everything changes so rapidly.

PAUL: Trey, in your mind what made the Dead so musically unique?

ANASTASIO: Many things. First, their relaxed quality. Back in the Eighties, a Dead show might’ve seemed kind of slow, but when you really paid attention to what was going on, you discovered a conversational quality that was totally unique. Their jams would make the whole arena resonate — almost like the building was becoming an instrument. There was a sensitivity that just does not happen at arena shows. You could sense that the Dead not only listened to each other, but that they were actually sensitive to the entire environment, which brought everyone in the room in the picture.

Also, I was immediately and completely blown away by Jerry’s guitar playing and singing. I really have come to deeply miss that feeling, when he would start to sing a song and the hair would stand up on the back of your neck. He would sing one line and the whole place would just melt. It was magic, and as the years go by it starts to sink in that that’s never going to happen again. It was so bristling with depth that you simultaneously wanted to cry and crack up laughing.

LESH: Oh yeah, that was there from the beginning. Being in a band with Jerry was cosmic. It always felt like destiny. There was just an overwhelming sense of rightness for everybody involved. And, ultimately, I think we all reinforced each other. The heart was distributed between us.

ANASTASIO: Growing up in suburban New Jersey, with the mall as the center of everything, I often wondered, “What does life have to offer me?” All I could see was consumerism, but the concept that buying things was going to make me happy seemed hollow and meaningless. School offered nothing, and even most music seemed horrible. Music was supposed to be all about spirituality—its history is intertwined with weddings, births and funerals — but there was nothing. And then I saw the Dead, and I immediately understood that they were trying to communicate real, human emotions instead of fake, consumer emotions. And I just threw my arms around them and embraced their music.

PAUL: Phil, you have done a lot of touring and even jamming with Bob Dylan. What is your perspective on what makes him so great?

LESH: Every generation throws up a few real masters and in our generation it’s probably the Beatles, Coltrane, Picasso and Dylan. He’s a poet, an artist and a hero. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was the first thing I heard on the radio that really knocked me out. Hearing Bob Dylan on AM radio was a reminder that anything is possible. Dylan going electric was an absolute door opener. More so than the Beatles, whom I didn’t really like at first.

There was one point in ’64 where you could walk the streets of [San Francisco’s] Haight-Ashbury and hear Bringing It All Back Home coming out of virtually every window. And it had a profound influence on people while also completely altering the prevailing concept about the level to which you could take songwriting. It changed everything.

PAUL: In Phil and Friends you have now played with three Allman Brothers Band guitarists — Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring and Derek Trucks. In many ways there has always seemed to be a simpatico feeling between the Dead and the Allmans, two bands that approached similar ideas from very different perspectives.

LESH: Exactly. As musicians those guys have always had that same kind of open mind and willingness to go for the brass ring even at the risk of falling flat on their faces, which is very endearing to me. And it doesn’t surprise me that they could come up with the idea in Georgia while we were doing so in California. There are times when things are in the air. Revolution in the air, as Dylan said. And where you’re from just sort of determines your approach to the same basic problem or aspect or way of looking at things. And it’s definitely a major way of looking at music. And at life, if you like.

Trey, I’m curious about the relationship between improvisation and composition in Phish’s music.

ANASTASIO: I think a lot more of it composed than people seem to realize.

LESH: At your show at Shoreline, I couldn’t tell what was composed and what wasn’t, which I consider an ideal blend, something I hear in the music of Branford Marsalis. What are the proportions of each, and how do you determine what’s going to be improvised?

ANASTASIO: I used to really write a lot out, so some of the earlier tunes are fully charted — the drum parts, bass lines, guitar and keyboard fills, everything. And in our earlier years we did all these atonal fugues and other things which had to be played just so. Over the years we’ve done less of that and opened things up a bit but I still think it’s safe to say that more is composed than people imagine. We have a song called “Billy Breathes”…

LESH: Right. I know it.

ANASTASIO: Well, that outro that sounds like a jam is actually composed. The solo and everything is actually written out on paper, though when we play it live we will break away from it.

LESH: Ok. My question was actually about the live performance. It’s an interesting mix.

ANASTASIO: You have a compositional background, Phil. Are you writing out charts with this band?

LESH: No. I’m just encouraging active listening and “composing” on the fly. We move rapidly from one song to another, and oftentimes in the middle of an improvisation, someone will quote another song, which we sometimes will then actually play. People seem to think those moves are planned, but they are not. My experience is that if you have the right group of people and allow them to find such conjunctions on their own, they end up being beyond anything I could have thought up myself. It’s worth being forced to grope through darkness to find those magical moments. In fact, I consider that groping to be a big part of the art.

January 10, 2017

Stevie Ray Vaughan with David Bowie rehearsals

David Bowie died one year ago today. I’ve been spending a lot of time digging into Stevie Ray Vaughan’s work with Bowie on Let’s Dance, which was brought the guitarist to the attention of many in 1983. Check out some of their rehearsal work for the world tour that Stevie was supposed to be on. They had a falling out at the last minute. Nile Rodgers, who produced Let’s Dance, is playing on this as well.

<

January 4, 2017

Marc Quinones – The Allman Brothers’ secret weapon

Photo – Derek McCabe

Percussionist Marc Quinones may just be the most overlooked, underrated member in the Allman Brothers’ storied 45-year career. He was an incredibly insightful interview and source of information for One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band

.

. I wanted to share things that two founding members of the band – Jaimoe and Gregg Allman – told me about Marc.

JAIMOE: “Marc Quinones is probably the smartest person that’s ever been in the Allman Brothers Band.”

GREGG ALLMAN: “I’ll tell you when this [solo] band turned the corner and started sounding like I wanted… when marc Quinones came over from the Allman Brothers and joined. he just gives it that something extra, and raises everyone else up.”

Three drummers, 2002. FOTO BY KIRK WEST

December 15, 2016

Chris Stapleton, “Whipping Post”

Chris Stapleton and friends do a pretty damn good “Whipping Post” on Nashville’s Skyville Live, a show about which I know absolutely nothing… but need to learn more about.

“Whipping Post” from Skyville Live on Vimeo.

December 13, 2016

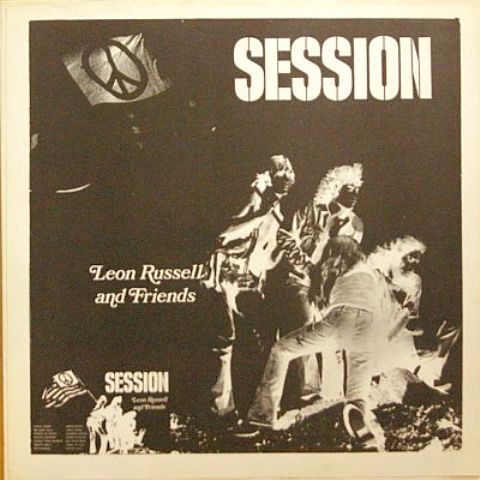

Just an incredible 1970 Leon Russell and friends performance

This Leon Russell and friends performance from 1970 is a contender for greatest thing ever. Fantastic music. Impeccable historical document. Includes Jim Horn, Furry Lewis, Don Preston, Carl Radle… and a bunch of their children…

The following information all comes from this very interesting website dedicated to 1970s bootleg recordings. This broadcast was very widely bootlegged.

This show – Homewood Session, Vine Street Theatre, Hollywood, CA – was originally broadcast on December 5, 1970 (US TV, KCET Los Angeles). A note adds:

The Vine Street Theatre had a little studio in the back part of the building. The show is billed on the theatre marquee at the beginning as “The Vine Street Theatre presents Homewood”, but the on air host calls it “Session”. They actually shot six hours but only broadcast one hour. As Leon says in the opening intro from when it was rebroadcast, it was unscripted and unrehearsed. Leon also says that it was the first national broadcast of a “stereo” rock and roll performance but that would have required an FM simulcast, since American television was not stereo in 1970 or even in the 1980s when this was probably rebroadcast.

“Session – Leon Russell and Friends”:

Don Nix

Claudia Linnear

Kathi McDonald

Chuck Blackwell

Jim Horn

John Gallie

Furry Lewis

Don Preston

Joey Cooper

Carl Radle

Emily

One of the most copied bootlegs of 1971.