Dickensians! discussion

David Copperfield - Group Read 1

>

May - June 2020: David Copperfield: chapters 45 - 64

Bionic Jean wrote: "This chapter was definitely the wordiest we have had yet! I do tire easily now, of Mr Micawber's pomposity and grandiloquence - not to mention the bathos :(... Does anyone else feel like this?"

Bionic Jean wrote: "This chapter was definitely the wordiest we have had yet! I do tire easily now, of Mr Micawber's pomposity and grandiloquence - not to mention the bathos :(... Does anyone else feel like this?"Not me, Jean - I love the Micawbers and the more ridiculous letters and turns of phrase from Mr Micawber the better for me!

I have noticed, though, that their family doesn't seem to age at the same rate as the other characters - surely the twins should be almost grown up by now, as they were babies when the young David was working at the blacking factory at the age of 10 or 11, and he is now a successful author!

Lori wrote: "I notice that this is very different from Mr Micawber’s usual reaction to his creditors. This is far beyond the “something will turn up” type of pep talks we’re used to hearing from Micawber. This ..."

Lori wrote: "I notice that this is very different from Mr Micawber’s usual reaction to his creditors. This is far beyond the “something will turn up” type of pep talks we’re used to hearing from Micawber. This ..."I think you are right, Lori, especially as he can't be cheered up even by making punch - usually food and drink cheer Mr Micawber up immediately!

Jean wrote: Aunt Betsey detects what has not been said, that Emily is very probably expecting a child, mentioning how she would have loved to be a godmother to (the fantasy child) David's sister, but that:

Jean wrote: Aunt Betsey detects what has not been said, that Emily is very probably expecting a child, mentioning how she would have loved to be a godmother to (the fantasy child) David's sister, but that:"hardly anything would have given me greater pleasure, than to be godmother to that good young creature’s baby!"

Jean, I must admit I read this quite differently - that Aunt Betsey would have liked to be godmother to the baby of the young woman who cared for Emily, and that she is the "good young creature" mentioned here. I didn't think Emily herself was pregnant - I think they would probably not be considering emigrating to Australia if that was the case, at any rate until after the baby had arrived.

Sorry to write several posts in succession, I had fallen behind and have just caught up again, so am reading through the thread. :)

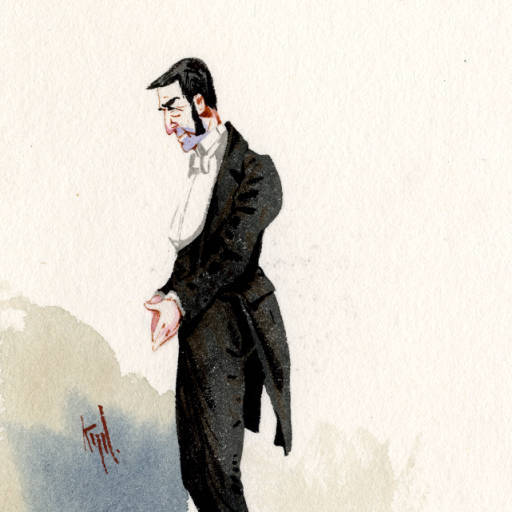

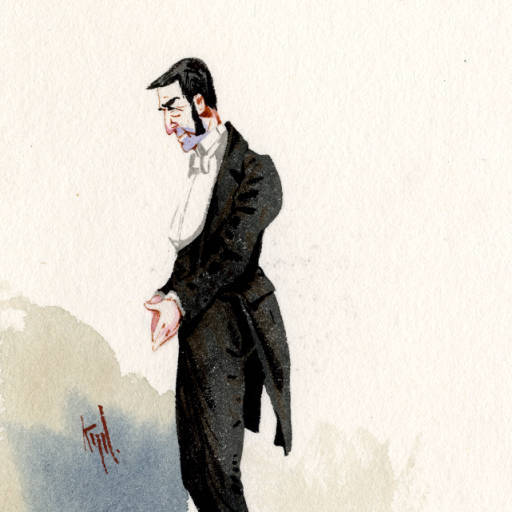

Well I came on here, just thinking I'd like to post Kyd's portrait of Littimer, as when I saw Cindy's excellent post, finishing with the "sweet deal for [Steerforth], not so much for everyone else!" I thought this would seal how we think of that "noble servant"!

Littimer - Kyd

As it was after midnight here - but when I come on the next morning there are 16 further comments! (Not that I'm complaining you understand!)

Littimer - Kyd

As it was after midnight here - but when I come on the next morning there are 16 further comments! (Not that I'm complaining you understand!)

There are so many topics we could about about - for instance as Robin pointed out, the displacement of the indigenous Australians. Whilst we talk about the seeming contradiction of whether it's a land of opportunity for the English working class, or a place for England to send convicts to, the Victorians were so blinkered that they missed this main point completely.

So I'd like to take up several things, and am enormously pleased that you're all enjoying it so much - even Micawber's "loquacity" (perfect description Cindy) and Judy too likes this - it's good to know others appreciate Mr Micawber's flowery prose :) Thank you so much for linking to that article about John Dickens's overly verbose letters Judy. It looks as though Mr Micawber is an exaggeration, but oh my goodness the tendency is there, and these are priceless :D

But I must pass many possible lines of discussion through lack of time, and just mention a couple.

So I'd like to take up several things, and am enormously pleased that you're all enjoying it so much - even Micawber's "loquacity" (perfect description Cindy) and Judy too likes this - it's good to know others appreciate Mr Micawber's flowery prose :) Thank you so much for linking to that article about John Dickens's overly verbose letters Judy. It looks as though Mr Micawber is an exaggeration, but oh my goodness the tendency is there, and these are priceless :D

But I must pass many possible lines of discussion through lack of time, and just mention a couple.

Thank you so much Sara for the detailed look back at the parts of the book about Aunt Betsey. Like Petra I too had remembered the references to Mr Dick's brother. Since we now know that Betsey Trotwood had no hesitation in inventing another "man of business" - albeit for a higher purpose - I now do not necessarily believe all she says of the back story to do with Mr Dick! And anyway, the existence of an eccentric other brother does not preclude Mr Dick's case going to court.

Actually, there are huge amounts of money involved: £3000 outright, plus £100 per year. When you bear in mind that £1 in 1850 is worth £135.51 today we see how enormous that fortune is! (3000 x 135.51 ... I'm sure somebody can check the Maths, but I make it £406,530. 00 - nearly half a million pounds in today's money, with more income each year!)

On the other hand John Sutherland was postulating about the courts being involved, and from your careful research Sara, it looks as though they have not actually been mentioned. Still, I would like to know the connection between her and Mr Dick. And we do still have a little more to learn, before we can claim that this was a loose end Charles Dickens never tied up!

Actually, there are huge amounts of money involved: £3000 outright, plus £100 per year. When you bear in mind that £1 in 1850 is worth £135.51 today we see how enormous that fortune is! (3000 x 135.51 ... I'm sure somebody can check the Maths, but I make it £406,530. 00 - nearly half a million pounds in today's money, with more income each year!)

On the other hand John Sutherland was postulating about the courts being involved, and from your careful research Sara, it looks as though they have not actually been mentioned. Still, I would like to know the connection between her and Mr Dick. And we do still have a little more to learn, before we can claim that this was a loose end Charles Dickens never tied up!

Judy - I had been thinking of you, as I know you like to read by installment, yet thought we hadn't hear for several. I'm glad you're posting again. Actually I know of at least three members who are also reading this with us, but not chipping in, but I still hope they do :)

Yes! You have identified another conundrum with the Micawber children! The twins should not now be so young, as we are at least a decade later, with David in his early twenties. This is definitely something John Sutherland could write another essay on, in his book of Literary Conundrums. I can quite see the lines of enquiry he would take ... these are perhaps not the same twins but two more, the others having died of inanition, the possibility of Mrs Micawber having consulted specialist doctors in the towns where they lived ... etc etc. Let's hope he does!

Ah, but it's fairly clear (although suitably chastely written, for Victorian sensibilities) that Emily must be pregnant. I'll start another post.

Yes! You have identified another conundrum with the Micawber children! The twins should not now be so young, as we are at least a decade later, with David in his early twenties. This is definitely something John Sutherland could write another essay on, in his book of Literary Conundrums. I can quite see the lines of enquiry he would take ... these are perhaps not the same twins but two more, the others having died of inanition, the possibility of Mrs Micawber having consulted specialist doctors in the towns where they lived ... etc etc. Let's hope he does!

Ah, but it's fairly clear (although suitably chastely written, for Victorian sensibilities) that Emily must be pregnant. I'll start another post.

Is Emily Pregnant?

This is indicated in subtle ways, Judy, so we need to do a close textual analysis to be sure. You're quite right that the first indication isn't clear on its own; the tense is ambiguous.

"hardly anything would have given me greater pleasure, than to be godmother to that good young creature’s baby!"

I had actually wondered, in previous readings, if Betsey Trotwood had been referring to Clara, David's mother. Your idea that "Aunt Betsey would have liked to be godmother to the baby of the young woman who cared for Emily" is also a tempting one, although there's no connection between the two - and little enough between Aunt Betsey and Emily. She's never met her, and the sole connection is through David. It also occurred to me that one of the reasons the young woman took Emily in and cared for her, was because she spotted that Emily was at an early stage of pregnancy, before anyone else did (as she herself was pregnant).

I actually put two quotations to indicate her pregnancy in my summary, and it's the second that clinches it. When Mr Peggotty says, of the time before their voyage, "She’ll work at them clothes, as must be made;" what else could he mean? I can think of nothing else except her own pregnancy clothes, and clothes for the baby. He also wants to keep her safe until they travel, because of her condition. The full quotation is:

"‘Em’ly,’ he continued, ‘will keep along with me—poor child, she’s sore in need of peace and rest!—until such time as we goes upon our voyage. She’ll work at them clothes, as must be made; and I hope her troubles will begin to seem longer ago than they was, wen she finds herself once more by her rough but loving uncle.’"

It also fits (as Lori it was indicated, I think) with Rosa Dartle's wrath, provoked even more by jealousy for Steerforth's child. And they would need to get far far away, as there would be no escaping the fact that Emily was pregnant in her own neighbourhood, where her story was known and she would be shamed. Perhaps the locals might be sympathetic while she was merely a young woman who was "taken advantage of" but the presence of a child might be a step too far. Neither would she have the option of going away somewhere secret, in the country, to give birth, and then giving her child up for adoption (as so many Victorian females in an inappropriate situation seemed to). There would be no money for that; it would be the workhouse.

No, emigrating before giving birth is the best possible option. We know that Emily loves children, as she spent hours playing with little Minnie (Mr Omer's granddaughter), as well as the fisher-folk's children on the beach abroad. It's perhaps also a clue that Charles Dickens adds David's visit to the Omer family in the same chapter. Emily would want to keep her child, and in a new far-off country she would pass as a young widow.

Also from chapter 51, Dan Peggotty says:

"Theer’s mighty countries, fur from heer. Our future life lays over the sea.’

‘They will emigrate together, aunt,’ said I.

‘Yes!’ said Mr. Peggotty, with a hopeful smile. ‘No one can’t reproach my darling in Australia. We will begin a new life over theer!’"

A future - with children. I can see Mr Peggotty dandling Emily's child on his knee. He would take her as his own, just as he did Emily and Ham, and provide a home for them :) Just lovely!

This is indicated in subtle ways, Judy, so we need to do a close textual analysis to be sure. You're quite right that the first indication isn't clear on its own; the tense is ambiguous.

"hardly anything would have given me greater pleasure, than to be godmother to that good young creature’s baby!"

I had actually wondered, in previous readings, if Betsey Trotwood had been referring to Clara, David's mother. Your idea that "Aunt Betsey would have liked to be godmother to the baby of the young woman who cared for Emily" is also a tempting one, although there's no connection between the two - and little enough between Aunt Betsey and Emily. She's never met her, and the sole connection is through David. It also occurred to me that one of the reasons the young woman took Emily in and cared for her, was because she spotted that Emily was at an early stage of pregnancy, before anyone else did (as she herself was pregnant).

I actually put two quotations to indicate her pregnancy in my summary, and it's the second that clinches it. When Mr Peggotty says, of the time before their voyage, "She’ll work at them clothes, as must be made;" what else could he mean? I can think of nothing else except her own pregnancy clothes, and clothes for the baby. He also wants to keep her safe until they travel, because of her condition. The full quotation is:

"‘Em’ly,’ he continued, ‘will keep along with me—poor child, she’s sore in need of peace and rest!—until such time as we goes upon our voyage. She’ll work at them clothes, as must be made; and I hope her troubles will begin to seem longer ago than they was, wen she finds herself once more by her rough but loving uncle.’"

It also fits (as Lori it was indicated, I think) with Rosa Dartle's wrath, provoked even more by jealousy for Steerforth's child. And they would need to get far far away, as there would be no escaping the fact that Emily was pregnant in her own neighbourhood, where her story was known and she would be shamed. Perhaps the locals might be sympathetic while she was merely a young woman who was "taken advantage of" but the presence of a child might be a step too far. Neither would she have the option of going away somewhere secret, in the country, to give birth, and then giving her child up for adoption (as so many Victorian females in an inappropriate situation seemed to). There would be no money for that; it would be the workhouse.

No, emigrating before giving birth is the best possible option. We know that Emily loves children, as she spent hours playing with little Minnie (Mr Omer's granddaughter), as well as the fisher-folk's children on the beach abroad. It's perhaps also a clue that Charles Dickens adds David's visit to the Omer family in the same chapter. Emily would want to keep her child, and in a new far-off country she would pass as a young widow.

Also from chapter 51, Dan Peggotty says:

"Theer’s mighty countries, fur from heer. Our future life lays over the sea.’

‘They will emigrate together, aunt,’ said I.

‘Yes!’ said Mr. Peggotty, with a hopeful smile. ‘No one can’t reproach my darling in Australia. We will begin a new life over theer!’"

A future - with children. I can see Mr Peggotty dandling Emily's child on his knee. He would take her as his own, just as he did Emily and Ham, and provide a home for them :) Just lovely!

Jean, thank you so much for establishing the worth of Mr. Dick's monetary situation. It is another evidence of Aunt Betsey's good character that she did not consider taking any help from his fortune to help assuage her own turn of bad investment. I remember her clearly stating his money was to be used for himself only.

Jean, thank you so much for establishing the worth of Mr. Dick's monetary situation. It is another evidence of Aunt Betsey's good character that she did not consider taking any help from his fortune to help assuage her own turn of bad investment. I remember her clearly stating his money was to be used for himself only.I agree that Emily cannot have been other than pregnant. Even when I was a child that word was taboo and every euphemism was used or the condition totally ignored...and that was in situations where the woman was married. I believe Dickens would have needed to set it between the lines, as he has done, but Victorians would have picked up on the implications more easily than modern readers do.

I love your image of Dan Peggotty dangling a future child upon his knee. Australia would be an opportunity not only for Emily to start again but for the child not to suffer the ridicule that his state of birth would have brought upon him if known, which it could not help to have been in England.

Chapter 53:

Such a short chapter, to describe "the Little Blossom, as it flutters to the ground!".

Dora has grown weaker and weaker, and David no longer carries her downstairs. He knows really that what is coming is inevitable, and sits with her for many hours. Others too come to see her, such as her elderly aunts:

"Dora lies smiling on us, and is beautiful, and utters no hasty or complaining word."

"It is better so" - Fred Barnard

Aunt Betsey takes great care of Dora, and everyone remains cheerful with her, talking about when she will be better. David feels conflicted:

"Do I know, now, that my child-wife will soon leave me? They have told me so; they have told me nothing new to my thoughts—but I am far from sure that I have taken that truth to heart."

Dora speaks from her heart, having grown in wisdom:

"I am afraid, dear, I was too young. I don’t mean in years only, but in experience, and thoughts, and everything. I was such a silly little creature! I am afraid it would have been better, if we had only loved each other as a boy and girl, and forgotten it. I have begun to think I was not fit to be a wife."

David is distraught, and protests, but she goes on:

"... as years went on, my dear boy would have wearied of his child-wife. She would have been less and less a companion for him. He would have been more and more sensible of what was wanting in his home. She wouldn’t have improved. It is better as it is."

Dora has asked most particularly that Agnes should some and visit her, and now she insists that she be allowed to speak to Agnes alone.

When David is downstairs, he is aware how very old Jip now is. Jip has lost all his fiery aggression, and is more restless than usual. When he sees David he whines to go upstairs.

"He lies down at my feet, stretches himself out as if to sleep, and with a plaintive cry, is dead."

Agnes enters the room, and David calls to her about Jip, but is instead made instantly aware of her grief-stricken demeanour.

"It is over. Darkness comes before my eyes; and, for a time, all things are blotted out of my remembrance."

Such a short chapter, to describe "the Little Blossom, as it flutters to the ground!".

Dora has grown weaker and weaker, and David no longer carries her downstairs. He knows really that what is coming is inevitable, and sits with her for many hours. Others too come to see her, such as her elderly aunts:

"Dora lies smiling on us, and is beautiful, and utters no hasty or complaining word."

"It is better so" - Fred Barnard

Aunt Betsey takes great care of Dora, and everyone remains cheerful with her, talking about when she will be better. David feels conflicted:

"Do I know, now, that my child-wife will soon leave me? They have told me so; they have told me nothing new to my thoughts—but I am far from sure that I have taken that truth to heart."

Dora speaks from her heart, having grown in wisdom:

"I am afraid, dear, I was too young. I don’t mean in years only, but in experience, and thoughts, and everything. I was such a silly little creature! I am afraid it would have been better, if we had only loved each other as a boy and girl, and forgotten it. I have begun to think I was not fit to be a wife."

David is distraught, and protests, but she goes on:

"... as years went on, my dear boy would have wearied of his child-wife. She would have been less and less a companion for him. He would have been more and more sensible of what was wanting in his home. She wouldn’t have improved. It is better as it is."

Dora has asked most particularly that Agnes should some and visit her, and now she insists that she be allowed to speak to Agnes alone.

When David is downstairs, he is aware how very old Jip now is. Jip has lost all his fiery aggression, and is more restless than usual. When he sees David he whines to go upstairs.

"He lies down at my feet, stretches himself out as if to sleep, and with a plaintive cry, is dead."

Agnes enters the room, and David calls to her about Jip, but is instead made instantly aware of her grief-stricken demeanour.

"It is over. Darkness comes before my eyes; and, for a time, all things are blotted out of my remembrance."

I found this to be such a moving chapter; some of the prose is so poetic.

Charles Dickens seems to have put his heart into it. Perhaps he took especial care, because was telling his earlier lady-loves, Maria Beadnell, and his wife (who he no longer really cared for by now) that in the early days of their relationship(s), his love was strong and true? Who knows what went through his mind. But this feels authentic to me.

When someone we love is dying don't we all feel "I cannot shut out a pale lingering shadow of belief that she will be spared"? It is heart-rendingly beautiful.

The older David's voice is present throughout, and I love the way that he frames his vision, as if he actually sees the events not just in his mind, but as images before him. It reminds me of the device in films where the picture goes all blurry, before we get remembrances from the past. It's very theatrical, and affecting.

The self-reproach which Dora tells David he must not feel, comes through strongly, as the older David reproaches himself and feels remorse.

" ... my tears fall fast, and my undisciplined heart is chastened heavily—heavily.

I sit down by the fire, thinking with a blind remorse of all those secret feelings I have nourished since my marriage. I think of every little trifle between me and Dora, and feel the truth, that trifles make the sum of life ... Would it, indeed, have been better if we had loved each other as a boy and a girl, and forgotten it?"

Is this the David of the time, or the older David? I think the regret and remorse is slanted towards the older David, thinking retrospectively, with hindsight and the wisdom of age. The David of this scene is so full of love, that he would not have wanted to be without his child-wife. When he says this to Dora, I think he is genuine:

"We have been very happy, my sweet Dora."

Perhaps this is also why he cannot bear to dwell on describing either Dora's miscarriage, or Emily's pregnancy. It was losing a baby which began Dora's fragility and weakness, and she eventually died.

Jip dying at the same time ... is it a kind of urban myth? It's certainly there in literature, and another way to tug at our heartstrings. Perhaps some people swear that it is true, on occasion. Anyway, here it seemed "right", although I do wish David had carried the little dog to be with Dora.

We are left to speculate on why Dora wanted to see Agnes so strongly.

And this is one of my favourite illustrations too :) Just look at the position of Dora's hand (as Elizabeth urged us to take note of hands). It is Dora who is comforting David! And I have found this to be true, sitting by my brother's bedside at such a time. Being with one who is dying, we hope that we can be the one who offers comfort, but it may not be that way.

"It is better as it is." Beautiful, and so poignant. I am pleased this came from Dora, who has redeemed herself, I believe.

And her tragic death brings us to the end of installment 17.

Charles Dickens seems to have put his heart into it. Perhaps he took especial care, because was telling his earlier lady-loves, Maria Beadnell, and his wife (who he no longer really cared for by now) that in the early days of their relationship(s), his love was strong and true? Who knows what went through his mind. But this feels authentic to me.

When someone we love is dying don't we all feel "I cannot shut out a pale lingering shadow of belief that she will be spared"? It is heart-rendingly beautiful.

The older David's voice is present throughout, and I love the way that he frames his vision, as if he actually sees the events not just in his mind, but as images before him. It reminds me of the device in films where the picture goes all blurry, before we get remembrances from the past. It's very theatrical, and affecting.

The self-reproach which Dora tells David he must not feel, comes through strongly, as the older David reproaches himself and feels remorse.

" ... my tears fall fast, and my undisciplined heart is chastened heavily—heavily.

I sit down by the fire, thinking with a blind remorse of all those secret feelings I have nourished since my marriage. I think of every little trifle between me and Dora, and feel the truth, that trifles make the sum of life ... Would it, indeed, have been better if we had loved each other as a boy and a girl, and forgotten it?"

Is this the David of the time, or the older David? I think the regret and remorse is slanted towards the older David, thinking retrospectively, with hindsight and the wisdom of age. The David of this scene is so full of love, that he would not have wanted to be without his child-wife. When he says this to Dora, I think he is genuine:

"We have been very happy, my sweet Dora."

Perhaps this is also why he cannot bear to dwell on describing either Dora's miscarriage, or Emily's pregnancy. It was losing a baby which began Dora's fragility and weakness, and she eventually died.

Jip dying at the same time ... is it a kind of urban myth? It's certainly there in literature, and another way to tug at our heartstrings. Perhaps some people swear that it is true, on occasion. Anyway, here it seemed "right", although I do wish David had carried the little dog to be with Dora.

We are left to speculate on why Dora wanted to see Agnes so strongly.

And this is one of my favourite illustrations too :) Just look at the position of Dora's hand (as Elizabeth urged us to take note of hands). It is Dora who is comforting David! And I have found this to be true, sitting by my brother's bedside at such a time. Being with one who is dying, we hope that we can be the one who offers comfort, but it may not be that way.

"It is better as it is." Beautiful, and so poignant. I am pleased this came from Dora, who has redeemed herself, I believe.

And her tragic death brings us to the end of installment 17.

Bionic Jean wrote: "

Bionic Jean wrote: "Is Emily Pregnant?

This is indicated in subtle ways, Judy, so we need to do a close textual analysis to be sure. You're quite right that the first indication isn't clear on its own; the tense ..."

Thank you, Jean, for your further thoughts and analysis on this. I can see that reference to making clothes does hint at a pregnancy, without saying it outright - and of course it was difficult for authors to state this type of thing outright at this time. There was a lot of controversy when Elizabeth Gaskell made an unmarried mother the heroine of her novel three Ruth, published in 1853, a few years after David Copperfield.

I was partly surprised at the idea of pregnancy because Emily is portrayed as on the brink of entering into prostitution like Martha at this point. Sadly she would not be the only pregnant woman to earn her living in this way in Victorian England, though. I think travelling all the way to Australia while pregnant (and probably quite far gone given all she has already gone through since splitting up with Steerforth) would have been quite dangerous given the conditions on ships at that time, but I suppose she would have her uncle to look after her. So, anyway, you have probably convinced me on the pregnancy front!

I don't think Aunt Betsey can be referring to Emily though. Looking back at Mr Peggotty's account, he refers to the woman who cared for Emily as "that good young creetur" and Betsey then uses exactly the same phrase "that good young creature's baby", so that's still how I read that comment, although, as you say, she never even met the woman. Then again, she only met Clara once! I suppose being a godmother is probably the main way she can think of to express approval and help anyone!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Judy - I had been thinking of you, as I know you like to read by installment, yet thought we hadn't hear for several. I'm glad you're posting again..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Judy - I had been thinking of you, as I know you like to read by installment, yet thought we hadn't hear for several. I'm glad you're posting again..."Thank you, Jean - sorry to keep disappearing but I have been a bit busy. Kind of you to think of me. It would be fun to see John Sutherland write a piece about why the Micawbers' children grow up so slowly - this is something else that had never struck me on previous readings of the book, like Emily's pregnancy.

Judy wrote: "I suppose being a godmother is probably the main way she can think of to express approval and help anyone! ..."

That's a good thought :) I do love Aunt Betsey. At the end of this novel we should have a "Who's your favourite character!?" I know who mine would be!

That's a good thought :) I do love Aunt Betsey. At the end of this novel we should have a "Who's your favourite character!?" I know who mine would be!

Those who have read biographies will recall that Dickens was hugely grieved by the death of his sister-in-law. It is a bit creepy in my opinion, but it probably gave him the ability to write death scenes like this with great pathos.

Those who have read biographies will recall that Dickens was hugely grieved by the death of his sister-in-law. It is a bit creepy in my opinion, but it probably gave him the ability to write death scenes like this with great pathos.

While some might say this was melodramatic, I found it quite touching. Jip's death coinciding with Dora's seemed so right, as he was always with her and it conjured an image of her beaconing to him as soon as she crossed over to come.

While some might say this was melodramatic, I found it quite touching. Jip's death coinciding with Dora's seemed so right, as he was always with her and it conjured an image of her beaconing to him as soon as she crossed over to come. I have also sat at the bedside of a dying loved one and I understand exactly what you are saying regarding the comforting, Jean. Perhaps those of us left behind need the comfort more, since we must now grapple, as David does, with even our innermost thoughts that might now seem like betrayals or tresspasses.

This might seem foolish to others, but I wondered if this scene did not inspire the death of Lavinia in Downton Abbey. The statement from Dora that it might be better this way echoed Lavinia in my memory. And the sweetness of Dora echoed her as well.

Robin wrote: "Dickens was hugely grieved by the death of his sister-in-law ... it probably gave him the ability to write death scenes like this with great pathos."

I'm sure you are right, Robin. Mary Hogarth's death in 1837 affected him hugely, and Charles Dickens was right there at her side, (as Mary lived with the couple, to help his wife Catherine with the household duties). Mary was only 17 years old, and Charles Dickens's novels are full of depictions of beautiful sensitive 17 year old girls, (two of whom do actually die). It was the only time Charles Dickens ever missed a deadline for his work.

He must have lived the tragedy of that scene over and over, and writing about different deathbed scenes might have been cathartic. It certainly is powerful.

Charles Dickens can be full of melodrama, and this puts some modern readers off, but each death scene in David Copperfield has really moved me.

I'm sure you are right, Robin. Mary Hogarth's death in 1837 affected him hugely, and Charles Dickens was right there at her side, (as Mary lived with the couple, to help his wife Catherine with the household duties). Mary was only 17 years old, and Charles Dickens's novels are full of depictions of beautiful sensitive 17 year old girls, (two of whom do actually die). It was the only time Charles Dickens ever missed a deadline for his work.

He must have lived the tragedy of that scene over and over, and writing about different deathbed scenes might have been cathartic. It certainly is powerful.

Charles Dickens can be full of melodrama, and this puts some modern readers off, but each death scene in David Copperfield has really moved me.

Rosemarie wrote: "I am enjoying this read so much more than I would on my own thanks to everyone's comments and Jean's excellent summaries.

Rosemarie wrote: "I am enjoying this read so much more than I would on my own thanks to everyone's comments and Jean's excellent summaries.I also think we could form an Aunt Betsey Fan Club-she is such a strong an..."

I am enjoying the reading too, Rosemarie. When I introduced myself to the group, I wrote that I woulnd’t probably take part in the read because I was afraid I couldn’t make it, but when I saw the discussion I couldn’t resist, and started reading it, and I am keeping up, and enjoying it so much.

As for the Aunt Betsey Fan Club, please count me in. I love aunt Betsey. :)

I wonder if we will ever be privy to Dora’s last words to Agnes.

I wonder if we will ever be privy to Dora’s last words to Agnes. I couldn’t help thinking that Dora’s deathbed scene is what I would consider the “quintessential Victorian death scene”. Dora sort of faded away over the course of a few chapters and parted without complaint but with an abundance of sweetness. Attended to in her bedroom by family members. I love that the “Little Blossom” is finally the source of understanding and insight. “It’s better this way” are words of profound wisdom and I would not have predicted that earlier in the novel.

I also thought it was appropriate for the aging Jip to depart with Dora. For me it signified her transition from this world to the next.

I am struck by Dora's clear-headed dialogue with David in the deathbed scene. She states clearly and seriously here what she has tried to express to David, but could only express herself in childish ways and language before, that she "always was a silly little thing," not an adequate partner, and that as time went on he would find it difficult to continue to love her. In the past Dora has stated she wished to live with Agnes in order to learn from her. I believe she realizes now that it is Agnes who could be a real partner equal to David, although she does not speak of that to David, only that she wishes to see Agnes alone. She has always been self aware and now we can see her, not as David has seen her and continues to think of her as his child-wife, but as a woman with wisdom, thoughtfulness and filled with love for her husband.

I am struck by Dora's clear-headed dialogue with David in the deathbed scene. She states clearly and seriously here what she has tried to express to David, but could only express herself in childish ways and language before, that she "always was a silly little thing," not an adequate partner, and that as time went on he would find it difficult to continue to love her. In the past Dora has stated she wished to live with Agnes in order to learn from her. I believe she realizes now that it is Agnes who could be a real partner equal to David, although she does not speak of that to David, only that she wishes to see Agnes alone. She has always been self aware and now we can see her, not as David has seen her and continues to think of her as his child-wife, but as a woman with wisdom, thoughtfulness and filled with love for her husband. As Dora says, "it is better as it is."

Bionic Jean wrote: "I love the way that he frames his vision, as if he actually sees the events not just in his mind, but as images before him. It reminds me of the device in films where the picture goes all blurry, before we get remembrances from the past. It's very theatrical, and affecting."

Bionic Jean wrote: "I love the way that he frames his vision, as if he actually sees the events not just in his mind, but as images before him. It reminds me of the device in films where the picture goes all blurry, before we get remembrances from the past. It's very theatrical, and affecting."Jean, I also loved the way he frames his vision. You are right: it’s very affecting. I confess that the words of the book got blurred a couple of times while I was reading this chapter. :-)

Sometimes you know something is coming and, yet, here I am where just reading the comment make me cry.

Sometimes you know something is coming and, yet, here I am where just reading the comment make me cry. I agree that most of it is recounted from older David's perspective, younger David is completely in the moment... Only in hindsight can he let himself agree with Dora that it was better this way and that he would have tired of her, he was already regretting is marriage at that point. Dickens prose here might be melodramatic, but it is effective.

I don't know if pets dying at the same time as their masters is plausible or not, but I know that when my grand-father died, the dog stopped eating and was dead within 2 weeks so animals not wanting to live without their master is 100% possible.

I've been enjoying the discussions and Judy's post with an excerpt of a John Dickens letter was very interesting (I miss it in the other thread) though you would have thought that JD would have recognized himself in Wilkins Micawber!

The Micawbers' children have been traveling in the Tardis for a couple of years... though The Doctor met Charles Dickens only around Christmas 1869 so I'm not sure how they accomplished the everybody forgetting the real life of the Micawber children in the original David Copperfield. The only explanation I can see is that some Retcon was used courtesy of Torchwood.

The Micawbers' children have been traveling in the Tardis for a couple of years... though The Doctor met Charles Dickens only around Christmas 1869 so I'm not sure how they accomplished the everybody forgetting the real life of the Micawber children in the original David Copperfield. The only explanation I can see is that some Retcon was used courtesy of Torchwood.If you understood nothing of this comment, sorry. I went a little off world there! Needed a little break from this sad chapter.

I agree Dora's death is very sad, and she really isn't silly in this scene, even though she keeps saying that she is. The death of Jip at the same moment is sentimental but I think it works well, all the same - Dickens shows Dora's death through Jip's, as we don't actually see the moment of her passing.

I agree Dora's death is very sad, and she really isn't silly in this scene, even though she keeps saying that she is. The death of Jip at the same moment is sentimental but I think it works well, all the same - Dickens shows Dora's death through Jip's, as we don't actually see the moment of her passing.I didn't really find Dora annoying this time around, after reading the book several times before - she is very sweet and loving as well as being spoilt and silly.

I also noticed it is briefly mentioned in an earlier chapter that she goes to the prison to visit the young page boy who stole her watch because he asks to see her, even though she is scared and faints when she gets there - I was quite surprised to realise she has the courage to do something like that.

France-Andrée wrote: "The Micawbers' children have been traveling in the Tardis for a couple of years... though The Doctor met Charles Dickens only around Christmas 1869 so I'm not sure how they accomplished the everybo..."

France-Andrée wrote: "The Micawbers' children have been traveling in the Tardis for a couple of years... though The Doctor met Charles Dickens only around Christmas 1869 so I'm not sure how they accomplished the everybo..."Very good, France-Andrée! ;)

Milena wrote: "Jean, I also loved the way he frames his vision. You are right: it’s very affecting. I confess that the words of the book got blurred a couple of times while I was reading this chapter. :-)..."

Me too :)

As France-Andree said, we can know something is coming up - and this was telegraphed quite clearly - yet it still affects us.

And "when I saw the discussion I couldn’t resist, and started reading it, and I am keeping up, and enjoying it so much" - this makes me so happy, Milena!

Judy - "sorry to keep disappearing but I have been a bit busy - Not at all! My goodness, life will keep interrupting our reading ;) I thought of (and missed) your expertise with the accent especially during Mr Peggotty's exposition about Emily, but fortunately he didn't use too much dialect :)

France-Andrée - I was fine with (ie., I understood!) your comment about Doctor Who - and of course the good Doctor does know Charles Dickens - as he has met him on at least one (maybe two?) occasions (Simon Callow played Dr Who.)

I was a little stumped by Sara's reference to Lavinia, but do get the gist!

Maybe Rosemarie can arrange to hire the Tardis, just for the Aunt Betsey's fan club outing ;)

Judy - [Dora] goes to the prison to visit the young page boy who stole her watch" Oh yes! I'd forgotten that - but I do remember being surprised at the time. Perhaps that was when she was beginning to grow up a little.

As Elizabeth says, "I am struck by Dora's clear-headed dialogue with David in the deathbed scene".

You gave a lovely summing-up :) Dora finally seems to beginning to mature at this point, although she has been a little thoughtful before, and David didn't notice it. In earlier parts she was truly childlike; blameless really, because she had never really got much past seeing herself at the centre of everything, until she became ill. But she never did anything unkind, and was always sweet (albeit annoying - but kids are sometimes, aren't they?!)

Me too :)

As France-Andree said, we can know something is coming up - and this was telegraphed quite clearly - yet it still affects us.

And "when I saw the discussion I couldn’t resist, and started reading it, and I am keeping up, and enjoying it so much" - this makes me so happy, Milena!

Judy - "sorry to keep disappearing but I have been a bit busy - Not at all! My goodness, life will keep interrupting our reading ;) I thought of (and missed) your expertise with the accent especially during Mr Peggotty's exposition about Emily, but fortunately he didn't use too much dialect :)

France-Andrée - I was fine with (ie., I understood!) your comment about Doctor Who - and of course the good Doctor does know Charles Dickens - as he has met him on at least one (maybe two?) occasions (Simon Callow played Dr Who.)

I was a little stumped by Sara's reference to Lavinia, but do get the gist!

Maybe Rosemarie can arrange to hire the Tardis, just for the Aunt Betsey's fan club outing ;)

Judy - [Dora] goes to the prison to visit the young page boy who stole her watch" Oh yes! I'd forgotten that - but I do remember being surprised at the time. Perhaps that was when she was beginning to grow up a little.

As Elizabeth says, "I am struck by Dora's clear-headed dialogue with David in the deathbed scene".

You gave a lovely summing-up :) Dora finally seems to beginning to mature at this point, although she has been a little thoughtful before, and David didn't notice it. In earlier parts she was truly childlike; blameless really, because she had never really got much past seeing herself at the centre of everything, until she became ill. But she never did anything unkind, and was always sweet (albeit annoying - but kids are sometimes, aren't they?!)

Jean, if my memory serves me (and it usually doesn't!), Lavinia was the young woman Matthew Crawley became engaged to when he and Mary split up. She recognized that he and Mary were still in love, but he was too kind and honorable to dump Lavinia and go back to Mary. Lavinia, like a real trooper, accepts her impending death (during the Spanish flu pandemic) with grace, perfectly willing to go to eternal rest so that Matthew can be with his true love. She's definitely a better woman than me!

Jean, if my memory serves me (and it usually doesn't!), Lavinia was the young woman Matthew Crawley became engaged to when he and Mary split up. She recognized that he and Mary were still in love, but he was too kind and honorable to dump Lavinia and go back to Mary. Lavinia, like a real trooper, accepts her impending death (during the Spanish flu pandemic) with grace, perfectly willing to go to eternal rest so that Matthew can be with his true love. She's definitely a better woman than me!

And better than me as well, Cindy. I would love to be able to ask Julian Fellowes if his reading of Dickens had any influence on his writing. Couldn't help drawing the parallel in my mind.

And better than me as well, Cindy. I would love to be able to ask Julian Fellowes if his reading of Dickens had any influence on his writing. Couldn't help drawing the parallel in my mind.

I was thinking that Dora's deathbed scene seemed very theatrical, but in a good sense. It showed Dora thinking clearly, feeling concern about David, and acting very mature and loving, so we care even more deeply that she died. The death of Jip at the same moment added to the theatrical feeling. It seemed like Dora was passing the torch to Agnes to care for David.

I was thinking that Dora's deathbed scene seemed very theatrical, but in a good sense. It showed Dora thinking clearly, feeling concern about David, and acting very mature and loving, so we care even more deeply that she died. The death of Jip at the same moment added to the theatrical feeling. It seemed like Dora was passing the torch to Agnes to care for David.

Chapter 54:

David finds that his grief for Dora becomes overwhelming, and it is suggested that he go abroad for a while, and travel. His thoughts turn to Agnes:

"I began to think that in my old association of her with the stained-glass window in the church, a prophetic foreshadowing of what she would be to me ... she was like a sacred presence in my lonely house."

My Child-Wife's Old Companion - Phiz

Until he is to go abroad, he waits for the "final pulverization of Heep", and the departure of those emigrating to Australia.

One day Traddles asks that David, his aunt, and Agnes, go to Canterbury, to meet with Mr Micawber. Aunt Betsey asks Mr Micawber if he has thought any more about emigrating, and Mr Micawber sets out how he plans to repay the loan she has promised, setting the repayments to be a little delayed to "allow sufficient time for the requisite amount of—Something—to turn up".

The Micawbers seem to be determined to make a success of their new enterprise. The children have been helping in various ways, such as learning to milk cows, tend pigs and poultry, and drive cattle. Mrs Micawber explains, in a flowery style much in keeping with that of her husband, that she has been writing letters to her family, in an attempt to reconcile their differences. It has been a revelation to her, she says, that they were apprehensive that Mr Micawber would ask them to put their names to various bills. Since Mr Micawber now has no "pecuniary difficulties" she does not see why her family should not plan and pay for a "festive entertainment", in her husband's honour, at which he will speak.

Mr Micawber gives his candid views as to his wife's relations:

"my impression being that your family are, in the aggregate, impertinent Snobs; and, in detail, unmitigated Ruffians ... I can go abroad without your family coming forward to favour me,—in short, with a parting Shove of their cold shoulders; and that, upon the whole, I would rather leave England with such impetus as I possess, than derive any acceleration of it from that quarter."

But Emma Micawber is sad that the two sides do not understand one another. Mr and Mrs Micawber then leave the others alone. David confesses his worries about his Aunt Betsey to Traddles, but Aunt Betsey insists it is nothing—although her face betrays that this is not so.

Traddles starts off by being very complimentary about Mr Micawber, Mr Dick and Mr Wickfield, all of whom, he says, have worked so hard and long to sort out the "great mass of unintentional confusion in the first place, and of wilful confusion and falsification in the second", which was the result of Uriah Heep's plots. Now that Uriah Heep has gone Mr. Wickfield's memory and attention to business have improved so much that he has been able to help to clarify certain things. Traddles is happy to announce that Mr Wickfield is not in debt, but that he might like to consider selling his property—although it would be up to Mr Wickfield—he merely suggests the thought. Agnes says she would like for them to rent the house, and she will start a school: "Our wants are not many ... I shall be useful and happy."

Traddles moves on to Aunt Betsey, and establishes that £8000 had been appropriated by Uriah Heep, as the value of her cottage, but he is perplexed that he can only account for £5000. This is correct, as Betsey Trotwood can account for the rest. She explains that she had used £1000 to pay David's articles, and the other £2000 she had kept by her, not telling David about it, because she wanted to see if he could manage without her financial help. David, she says, came out nobly—"persevering, self-reliant, self-denying!"

Everyone learns more examples of the harm caused by Uriah Heep's greed, as Aunt Betsey tells how Mr Wickfield had been persuaded that this was all his fault, and:

"wrote me a mad letter, charging himself with robbery, and wrong unheard of. Upon which I paid him a visit early one morning, called for a candle, burnt the letter, and told him if he ever could right me and himself, to do it; and if he couldn’t, to keep his own counsel for his daughter’s sake."

Traddles says that even Uriah Heep's avarice was still not as great as his hatred of David:

"He said he would even have spent as much, to baulk or injure Copperfield."

Traddles does not know where the Heeps are now, but he knows that they went off somewhere by the London night coach. There is no chance that Uriah Heep will mend his ways, he says:

"He is such an incarnate hypocrite, that whatever object he pursues, he must pursue crookedly."

Next Traddles moves on to Mr Micawber, and Aunt Betsey says that the IOUs which Uriah Heep has from him must be paid. They work out a sum of money which includes these, the fees for their passage and outfits, plus a hundred pounds. Also that:

"Mr. Micawber’s arrangement for the repayment of the advances should be gravely entered into, as it might be wholesome for him to suppose himself under that responsibility."

David finally says that he will give Mr Peggotty another hundred pounds, to cover whatever money Mr Micawber may ask him to lend, and that he will tell both men enough of the other's history and character, to help them to understand each other and get along.

Traddles hesitates before mentioning his final duty, which is to do with Betsey Trotwood's husband. She confirms that there was such a person in Uriah Heep's power, but Traddles has not been able to discover anything. If he could do anything, he would.

"My aunt remained quiet; until again some stray tears found their way to her cheeks. ‘You are quite right,’ she said. ‘It was very thoughtful to mention it.’"

After a brief visit to Mr Micawber to finalise the payment of some of the bills—and the strong recommendation from Aunt Betsey that he never get into the habit of borrowing such money again—the day's business is completed. Aunt Betsey promises to tell David what has been troubling her for so long, the next morning.

At 9am, they take a little chariot and drive to one of the London hospitals, outside which stands a hearse.

"You understand it now, Trot, ... He is gone! ... He was ailing a long time—a shattered, broken man, these many years ... in this last illness, he asked them to send for me. He was sorry then. Very sorry."

David realises that her husband had died the night before they went to Canterbury."

"‘No one can harm him now,’ she said. ‘It was a vain threat.’’’

They drive through Hornsey (North London), where Aunt Betsey says he had been born, and watch the funeral service in the churchyard where he was to be buried. She had married him 36 years ago, when he was "a fine-looking man".

The chapter ends with typical bathos from Mr Micawber. A letter from him pronounces that all is lost, and he is incarcerated in goal, moving "to a speedy end" because of his "mental torture". However a P.S. reveals that Traddles has paid the outstanding bill, in Aunt Betsey's name, and that as a consequence now "myself and family are at the height of earthly bliss."

David finds that his grief for Dora becomes overwhelming, and it is suggested that he go abroad for a while, and travel. His thoughts turn to Agnes:

"I began to think that in my old association of her with the stained-glass window in the church, a prophetic foreshadowing of what she would be to me ... she was like a sacred presence in my lonely house."

My Child-Wife's Old Companion - Phiz

Until he is to go abroad, he waits for the "final pulverization of Heep", and the departure of those emigrating to Australia.

One day Traddles asks that David, his aunt, and Agnes, go to Canterbury, to meet with Mr Micawber. Aunt Betsey asks Mr Micawber if he has thought any more about emigrating, and Mr Micawber sets out how he plans to repay the loan she has promised, setting the repayments to be a little delayed to "allow sufficient time for the requisite amount of—Something—to turn up".

The Micawbers seem to be determined to make a success of their new enterprise. The children have been helping in various ways, such as learning to milk cows, tend pigs and poultry, and drive cattle. Mrs Micawber explains, in a flowery style much in keeping with that of her husband, that she has been writing letters to her family, in an attempt to reconcile their differences. It has been a revelation to her, she says, that they were apprehensive that Mr Micawber would ask them to put their names to various bills. Since Mr Micawber now has no "pecuniary difficulties" she does not see why her family should not plan and pay for a "festive entertainment", in her husband's honour, at which he will speak.

Mr Micawber gives his candid views as to his wife's relations:

"my impression being that your family are, in the aggregate, impertinent Snobs; and, in detail, unmitigated Ruffians ... I can go abroad without your family coming forward to favour me,—in short, with a parting Shove of their cold shoulders; and that, upon the whole, I would rather leave England with such impetus as I possess, than derive any acceleration of it from that quarter."

But Emma Micawber is sad that the two sides do not understand one another. Mr and Mrs Micawber then leave the others alone. David confesses his worries about his Aunt Betsey to Traddles, but Aunt Betsey insists it is nothing—although her face betrays that this is not so.

Traddles starts off by being very complimentary about Mr Micawber, Mr Dick and Mr Wickfield, all of whom, he says, have worked so hard and long to sort out the "great mass of unintentional confusion in the first place, and of wilful confusion and falsification in the second", which was the result of Uriah Heep's plots. Now that Uriah Heep has gone Mr. Wickfield's memory and attention to business have improved so much that he has been able to help to clarify certain things. Traddles is happy to announce that Mr Wickfield is not in debt, but that he might like to consider selling his property—although it would be up to Mr Wickfield—he merely suggests the thought. Agnes says she would like for them to rent the house, and she will start a school: "Our wants are not many ... I shall be useful and happy."

Traddles moves on to Aunt Betsey, and establishes that £8000 had been appropriated by Uriah Heep, as the value of her cottage, but he is perplexed that he can only account for £5000. This is correct, as Betsey Trotwood can account for the rest. She explains that she had used £1000 to pay David's articles, and the other £2000 she had kept by her, not telling David about it, because she wanted to see if he could manage without her financial help. David, she says, came out nobly—"persevering, self-reliant, self-denying!"

Everyone learns more examples of the harm caused by Uriah Heep's greed, as Aunt Betsey tells how Mr Wickfield had been persuaded that this was all his fault, and:

"wrote me a mad letter, charging himself with robbery, and wrong unheard of. Upon which I paid him a visit early one morning, called for a candle, burnt the letter, and told him if he ever could right me and himself, to do it; and if he couldn’t, to keep his own counsel for his daughter’s sake."

Traddles says that even Uriah Heep's avarice was still not as great as his hatred of David:

"He said he would even have spent as much, to baulk or injure Copperfield."

Traddles does not know where the Heeps are now, but he knows that they went off somewhere by the London night coach. There is no chance that Uriah Heep will mend his ways, he says:

"He is such an incarnate hypocrite, that whatever object he pursues, he must pursue crookedly."

Next Traddles moves on to Mr Micawber, and Aunt Betsey says that the IOUs which Uriah Heep has from him must be paid. They work out a sum of money which includes these, the fees for their passage and outfits, plus a hundred pounds. Also that:

"Mr. Micawber’s arrangement for the repayment of the advances should be gravely entered into, as it might be wholesome for him to suppose himself under that responsibility."

David finally says that he will give Mr Peggotty another hundred pounds, to cover whatever money Mr Micawber may ask him to lend, and that he will tell both men enough of the other's history and character, to help them to understand each other and get along.

Traddles hesitates before mentioning his final duty, which is to do with Betsey Trotwood's husband. She confirms that there was such a person in Uriah Heep's power, but Traddles has not been able to discover anything. If he could do anything, he would.

"My aunt remained quiet; until again some stray tears found their way to her cheeks. ‘You are quite right,’ she said. ‘It was very thoughtful to mention it.’"

After a brief visit to Mr Micawber to finalise the payment of some of the bills—and the strong recommendation from Aunt Betsey that he never get into the habit of borrowing such money again—the day's business is completed. Aunt Betsey promises to tell David what has been troubling her for so long, the next morning.

At 9am, they take a little chariot and drive to one of the London hospitals, outside which stands a hearse.

"You understand it now, Trot, ... He is gone! ... He was ailing a long time—a shattered, broken man, these many years ... in this last illness, he asked them to send for me. He was sorry then. Very sorry."

David realises that her husband had died the night before they went to Canterbury."

"‘No one can harm him now,’ she said. ‘It was a vain threat.’’’

They drive through Hornsey (North London), where Aunt Betsey says he had been born, and watch the funeral service in the churchyard where he was to be buried. She had married him 36 years ago, when he was "a fine-looking man".

The chapter ends with typical bathos from Mr Micawber. A letter from him pronounces that all is lost, and he is incarcerated in goal, moving "to a speedy end" because of his "mental torture". However a P.S. reveals that Traddles has paid the outstanding bill, in Aunt Betsey's name, and that as a consequence now "myself and family are at the height of earthly bliss."

Well Emma Micawber seems to be approaching her husband's grandiloquence here! Though I did enjoy the relish with which Micawber set to with his final bills, which is ironic since he is supposed to be leaving all that behind and going to be a farmer! His final letter here is a perfect chapter ending :)

So all the way through we've been tempted to speculate on the mystery about Aunt Betsey's husband, and the explanation, when it comes, is really just a bit of a let-down.

It seems very likely to me, that Aunt Betsey's husband was a sort of potential back-up plot. He was a flexible non-character who could be expanded as Dickens saw fit—or treated as a loose end which he could just tie up—as he has done. Very useful in serial writing, and at least Charles Dickens didn't leave the thread dangling.

So all the way through we've been tempted to speculate on the mystery about Aunt Betsey's husband, and the explanation, when it comes, is really just a bit of a let-down.

It seems very likely to me, that Aunt Betsey's husband was a sort of potential back-up plot. He was a flexible non-character who could be expanded as Dickens saw fit—or treated as a loose end which he could just tie up—as he has done. Very useful in serial writing, and at least Charles Dickens didn't leave the thread dangling.

Phiz's illustration

to this chapter, "My child-wife's old companion" is as always, worth a closer look.

David is seated sorrowfully in front of the fire. A guitar: a symbol of Dora, has a string broken, and the sheet music next to it bear the words "Requiem" and "Mozart". We can see Jip's pagoda, just behind Jip, which reminds us of Dora's impractical and romantic nature. Behind David is a candle which is smoking as it gutters out. A portrait of Dora looks down over him, and Agnes watches from the doorway.

Through the window, we can just see a church spire behind her, perhaps to signify a funeral, perhaps something else. Agnes's posture is subdued, and contained; she almost has a stance of supplication. Charles Dickens says in the text "The bright moon is high and clear", but here we see a cloud moving across it, immediately above Agnes's head.

The previous etching we looked at by Phiz showed a lot of disorganised clutter and confusion. Now though, we see things in their proper place, and the ornaments of the mantelpiece seem to reflect David and Dora's life: cupid holding aloft a rosebud, (or is it two?) and a clock to signify the passage of time.

David's thoughts are still full of Dora: a book lies on the floor, not shelved - and a sealed envelope too. Or perhaps this confusion represents Dora herself, to contrast with David's personal space. We can see that his writing desk and bookcase are tidy and well-organised, with his books and quill pen in their proper place.

I'm sure there are other details in this etching which are significant too.

David is seated sorrowfully in front of the fire. A guitar: a symbol of Dora, has a string broken, and the sheet music next to it bear the words "Requiem" and "Mozart". We can see Jip's pagoda, just behind Jip, which reminds us of Dora's impractical and romantic nature. Behind David is a candle which is smoking as it gutters out. A portrait of Dora looks down over him, and Agnes watches from the doorway.

Through the window, we can just see a church spire behind her, perhaps to signify a funeral, perhaps something else. Agnes's posture is subdued, and contained; she almost has a stance of supplication. Charles Dickens says in the text "The bright moon is high and clear", but here we see a cloud moving across it, immediately above Agnes's head.

The previous etching we looked at by Phiz showed a lot of disorganised clutter and confusion. Now though, we see things in their proper place, and the ornaments of the mantelpiece seem to reflect David and Dora's life: cupid holding aloft a rosebud, (or is it two?) and a clock to signify the passage of time.

David's thoughts are still full of Dora: a book lies on the floor, not shelved - and a sealed envelope too. Or perhaps this confusion represents Dora herself, to contrast with David's personal space. We can see that his writing desk and bookcase are tidy and well-organised, with his books and quill pen in their proper place.

I'm sure there are other details in this etching which are significant too.

And a little more ...

A last bit about Uriah Heep :

We know that physically Uriah Heep is based on Hans Christian Andersen, but just as with Dora Spenlow/Copperfield, Uriah Heep is possibly an amalgam of more than one person in Charles Dickens's life. He may have been partly based on a Thomas Powell.

Thomas Powell (1809–1887) was an English writer and fraudster. He was noted early for his prolific output and social charm, and he entertained a circle of notable authors at his home, often showing-off his skill at mimicking authors’ handwriting. But it became clear that he was putting this gift to criminal use, forging cheques and signatures.

According to one of Charles Dickens's biographers, Edgar Johnson, Thomas Powell had originally been introduced to Charles Dickens by his "ne’er-do-well brother" Augustus. These two were fellow clerks in the shipping business of John Chapman & Co. Charles Dickens knew the partners, and had asked them to find employment for Augustus. Using this work contact, Thomas Powell gradually ingratiated himself into the Dickens household, and dined several times with Charles Dickens at his home in Devonshire Terrace.

To amuse them all, Thomas Powell showed off his ability to mimic his fellow authors' handwriting and signatures. However, at the same time, he sold documents which he said were original letters and books inscribed by the authors, whose authenticity was questioned. Some of these were thought to be forgeries. He also embezzled a large sum of money from his employer, and when it was revealed that through a series of forgeries, Thomas Powell had defrauded his employer John Chapman out of 10,000 pounds, he attempted suicide by taking an overdose of laudanum.

John Chapman took pity on Thomas Powell, for his family's sake, and forgave his crime. However, after this Thomas Powell passed forged cheques defrauding various tradesmen. He was brought before a magistrate, but escaped prosecution by having himself certified insane and committed to a lunatic asylum.

Thomas Powell then fled to New York - where he escaped prosecution for another forgery! There Thomas Powell passed himself off as a literary man who had mingled with many celebrities in London, and published a sketch of Charles Dickens in “The Evening Post”.

When he heard about this sketch, Charles Dickens proclaimed it to be “A complete and libelous lie.” He wrote to a New York publisher, giving a full account of Thomas Powell’s career, and the letter was published in the “New York Tribune.”

Thomas Powell then sued Charles Dickens for £10,000. In retaliation, Charles Dickens gathered together all of the evidence of Powell’s misdeeds, and in 1849 had Bradbury and Evans print these in a four-page pamphlet, which Charles Dickens then forwarded to the editor of “The Sun” newspaper.

Apparently Thomas Powell had cultivated the acquaintance of various well-known writers, including Leigh Hunt, Robert Browning, William Wordsworth, and Alfred Tennyson. Robert Browning had corrected the proof sheets of a collection of verse published by Thomas Powell, although he was said to later regret his acquaintance with him, and had written to a friend, “None of your Powells inspecting my Bowels.”

Could aspects of this admirable chap Thomas Powell, who had caused Charles Dickens so much trouble, have found their way into the depiction of Uriah Heep, perhaps?

A last bit about Uriah Heep :

We know that physically Uriah Heep is based on Hans Christian Andersen, but just as with Dora Spenlow/Copperfield, Uriah Heep is possibly an amalgam of more than one person in Charles Dickens's life. He may have been partly based on a Thomas Powell.

Thomas Powell (1809–1887) was an English writer and fraudster. He was noted early for his prolific output and social charm, and he entertained a circle of notable authors at his home, often showing-off his skill at mimicking authors’ handwriting. But it became clear that he was putting this gift to criminal use, forging cheques and signatures.

According to one of Charles Dickens's biographers, Edgar Johnson, Thomas Powell had originally been introduced to Charles Dickens by his "ne’er-do-well brother" Augustus. These two were fellow clerks in the shipping business of John Chapman & Co. Charles Dickens knew the partners, and had asked them to find employment for Augustus. Using this work contact, Thomas Powell gradually ingratiated himself into the Dickens household, and dined several times with Charles Dickens at his home in Devonshire Terrace.

To amuse them all, Thomas Powell showed off his ability to mimic his fellow authors' handwriting and signatures. However, at the same time, he sold documents which he said were original letters and books inscribed by the authors, whose authenticity was questioned. Some of these were thought to be forgeries. He also embezzled a large sum of money from his employer, and when it was revealed that through a series of forgeries, Thomas Powell had defrauded his employer John Chapman out of 10,000 pounds, he attempted suicide by taking an overdose of laudanum.

John Chapman took pity on Thomas Powell, for his family's sake, and forgave his crime. However, after this Thomas Powell passed forged cheques defrauding various tradesmen. He was brought before a magistrate, but escaped prosecution by having himself certified insane and committed to a lunatic asylum.

Thomas Powell then fled to New York - where he escaped prosecution for another forgery! There Thomas Powell passed himself off as a literary man who had mingled with many celebrities in London, and published a sketch of Charles Dickens in “The Evening Post”.

When he heard about this sketch, Charles Dickens proclaimed it to be “A complete and libelous lie.” He wrote to a New York publisher, giving a full account of Thomas Powell’s career, and the letter was published in the “New York Tribune.”

Thomas Powell then sued Charles Dickens for £10,000. In retaliation, Charles Dickens gathered together all of the evidence of Powell’s misdeeds, and in 1849 had Bradbury and Evans print these in a four-page pamphlet, which Charles Dickens then forwarded to the editor of “The Sun” newspaper.

Apparently Thomas Powell had cultivated the acquaintance of various well-known writers, including Leigh Hunt, Robert Browning, William Wordsworth, and Alfred Tennyson. Robert Browning had corrected the proof sheets of a collection of verse published by Thomas Powell, although he was said to later regret his acquaintance with him, and had written to a friend, “None of your Powells inspecting my Bowels.”

Could aspects of this admirable chap Thomas Powell, who had caused Charles Dickens so much trouble, have found their way into the depiction of Uriah Heep, perhaps?

It's good to see that Aunt Betsey has found peace, and that she had a chance to say good-bye to her husband.

It's good to see that Aunt Betsey has found peace, and that she had a chance to say good-bye to her husband.

Bionic Jean wrote: "A guitar: a symbol of Dora, has a string broken, and the sheet music next to it bear the words "Requiem" and "Mozart". We can see Jip's pagoda, just behind Jip, which reminds us of Dora's impractical and romantic nature. Behind David is a candle which is smoking as it gutters out."

Bionic Jean wrote: "A guitar: a symbol of Dora, has a string broken, and the sheet music next to it bear the words "Requiem" and "Mozart". We can see Jip's pagoda, just behind Jip, which reminds us of Dora's impractical and romantic nature. Behind David is a candle which is smoking as it gutters out."I usually prefer Barnard’s pictures, but I love this one.

When it comes to law and business, I’m almost as ignorant as Dora, let alone Victorian law. But I hoped that Uriah would get some punishment instead of getting away with all he had done like that. If I understood correctly, there is a sort of negotiation between Traddles and Heep, and then:

When it comes to law and business, I’m almost as ignorant as Dora, let alone Victorian law. But I hoped that Uriah would get some punishment instead of getting away with all he had done like that. If I understood correctly, there is a sort of negotiation between Traddles and Heep, and then:He left here,” said Traddles, “with his mother. […] They went away by one of the London night coaches, and I know no more about him.

I wonder what would Uriah have done if he belonged to a social class that allowed him to study in a school like David did. He is smart, ambitious, he might have had a career, and not being forced to be “humble”. This might partly explain why (as Traddles said) “whatever object he pursues, he must pursue crookedly. It’s his only compensation for the outward restraints he puts upon himself.” This is a nature vs nurture question difficult to answer, but I like that Dickens raised the issue somehow.

Finally Mr Micawber did something good. As a reward, aunt Betsey gives him money to go to Australia. I am not sure as to whether aunt Betsey sends the Micawbers to Australia to prevent Mr Micawber from asking money to his nephew, or Dickens wishes his parents went to Australia. Either way, the Australians are grateful and are cheering enthusiastically.

But the real hero of the tale is Traddles: he is the man who, “in a composed and business-like way” (ch. 52) defeat the villain. No more skeletons for him. Way to go Tommy Traddles!

Thanks for posting all the details about Thomas Powell, Jean - fascinating stuff. I've seen him mentioned in various places but wasn't aware of the full extent of his forgery! Presumably his verse must have been quite good if Browning went to the trouble to correct his proofs.

Thanks for posting all the details about Thomas Powell, Jean - fascinating stuff. I've seen him mentioned in various places but wasn't aware of the full extent of his forgery! Presumably his verse must have been quite good if Browning went to the trouble to correct his proofs.

Thanks from me as well, Jean, for both the info on Powell and the details in the illustration. I do enjoy all the symbolism and doubt I would catch half of it without your astute observations. I can imagine the illustrations were very important to the serial readers.

Thanks from me as well, Jean, for both the info on Powell and the details in the illustration. I do enjoy all the symbolism and doubt I would catch half of it without your astute observations. I can imagine the illustrations were very important to the serial readers. Aunt Betsey's husband is another example of wasted potential. She would have made him a good and loving wife had he simply turned his hand to being honest. I suspect he knew that, since she was the person he called for on his deathbed.

I was pleased that David was going to give Mr. Peggotty a bit of insight into the Micawbers. Forewarning is necessary with Mr. Micawber, whom I sincerely hope is about to change his ways and actually have something "turn up."

What can you say about Uriah. Ugh, I hate him.

Mentioning Browning reminds me, I meant to comment earlier on the incident where Jip is kidnapped (or dognapped) and Dora has to pay a ransom - this used to happen quite a lot in London and happened to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's beloved spaniel, Flush, three times.

Mentioning Browning reminds me, I meant to comment earlier on the incident where Jip is kidnapped (or dognapped) and Dora has to pay a ransom - this used to happen quite a lot in London and happened to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's beloved spaniel, Flush, three times. There is a very long article about it here for anyone who shares my passion for the Brownings - Flush's last dognapping happened in 1846, so only a few years before David Copperfield was published. The article also has a lot of background about the whole dog-stealing network in the 1840s. There are thought to have been 141 people who made a living from stealing dogs and ransoming them!

https://medium.com/truly-adventurous/...

I was very impressed with how Tommy Traddles handled Heep's forgeries. He was so calm, thorough, and tactful, making sure that everyone received their due. He's matured a lot, but still retains his kindness. Along with Aunt Betsey, he's on my list of favorite characters.

I was very impressed with how Tommy Traddles handled Heep's forgeries. He was so calm, thorough, and tactful, making sure that everyone received their due. He's matured a lot, but still retains his kindness. Along with Aunt Betsey, he's on my list of favorite characters.

What great information about Thomas Powell, Jean, it is easy to see the link between him and Uriah. After all, poor Hans Christian Andersen might have been a bad visitor to have, but he wasn’t a fraudster so I agree that Heep is probably an amalgamation.

What great information about Thomas Powell, Jean, it is easy to see the link between him and Uriah. After all, poor Hans Christian Andersen might have been a bad visitor to have, but he wasn’t a fraudster so I agree that Heep is probably an amalgamation.I’m glad that David will give a head’s up to Dan Peggotty about Micawber and that the delicate matters on both sides will be made known to both parties so they wont have to mention them.

Dognapping?! Wow, I think I only saw that in novels, never thought it was based on real life. Not sure I would pay a ransom, it only opens you up to further dognapping especially if the dog behaved himself with his new “guardians”. Thank you, Judy, that was very interesting.

Jean, it's such a treat when you dig up such interesting information such as Thomas Powell's fraud. It was no easy thing for Dickens to be dealing with lawsuits across the Atlantic at a time when communication was so slow. Dickens is to be commended for alerting the American book sellers and authors.

Jean, it's such a treat when you dig up such interesting information such as Thomas Powell's fraud. It was no easy thing for Dickens to be dealing with lawsuits across the Atlantic at a time when communication was so slow. Dickens is to be commended for alerting the American book sellers and authors.