More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

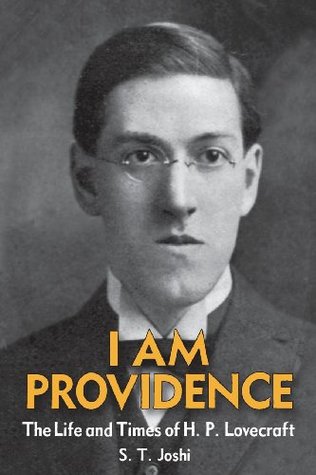

by

S.T. Joshi

Read between

October 19 - November 2, 2023

this period—from the summer of 1926 to the spring of 1927—represents the most remarkable outburst of fiction-writing in Lovecraft’s entire career. Only a month after leaving New York he wrote to Morton: “It is astonishing how much better the old head works since its restoration to those native scenes amidst which it belongs.

two short novels, two novelettes, and three short stories, totalling some 150,000 words, were written at this time, along with a handful of poems and essays. All the tales are set, at least in part, in New England.

Lovecraft was utilising his pseudomythology as one (among many) of the ways to convey his fundamental philosophical message, whose chief feature was cosmicism. This point is made clear in a letter written to Farnsworth Wright in July 1927 upon the resubmittal of “The Call of Cthulhu” to Weird Tales (it had been rejected upon initial submission): Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. To me there is nothing but puerility in a tale in which the human form—and the local

...more

It is careless and inaccurate to say that the Lovecraft Mythos is Lovecraft’s philosophy: his philosophy is mechanistic materialism and all its ramifications, and if the Lovecraft Mythos is anything, it is a series of plot devices meant to facilitate the expression of this philosophy.

Each one of these passages, and others throughout the story, has its exact corollary in his letters. It is rare that Lovecraft so bluntly expressed his philosophy in a work of fiction; but “The Silver Key” can be seen as his definitive repudiation both of Decadence as a literary theory and of cosmopolitanism as a way of life.

It must frankly be admitted that Carter has no concrete or coherent personality, and that Lovecraft resurrected him—at least, in the three tales (“The Unnamable,” “The Silver Key,” and the Dream-Quest) where he has a personality at all—as a convenient mouthpiece for views that were indeed his at that moment.

In the Dream-Quest, then, Carter serves as a means for emphatically underscoring Lovecraft’s New England heritage.

After a few more days in Athol, Lovecraft went on a lone tour first to Boston

the next day, to Portland, Maine. He spent two days in Portland and enjoyed the town immensely: although it was not as rich in antiquities as Marblehead or Portsmouth, it was scenically lovely—it occupies a peninsula with hills at the eastern and western ends, and has many beautiful drives and promenades—and at least had things like the two Longfellow houses (birthplace and principal residence), which Lovecraft explored thoroughly.

characterisation was far and away the weakest point in Lovecraft’s literary arsenal.

on Friday, June 29, Lovecraft moved on to another leg of his journey as distinctive as his Vermont stay; for Edith Miniter, the old-time amateur, almost demanded that Lovecraft pay her a visit in Wilbraham, Massachusetts,

Lovecraft rose at 6.30 to catch an 8 o’clock train to North Wilbraham. He stayed for eight days, being charmed by the vast array of antiques collected by Beebe, the seven cats and two dogs who had the run of the place, and especially by the spectral local folklore Miniter told him.

There was also a spectacular firefly display one night: “They leaped in the meadows, & under the spectral old oaks at the bend of the road. They danced tumultuously in the swampy hollow, & held witches’ sabbaths beneath the gnarled, ancient trees of the orchard.”[20] This trip certainly combined the archaic, the rustic, and the weird!

He first took a bus to Springfield (the largest town near Wilbraham), then on up to Greenfield, where he stayed in a hotel overnight

As will become manifestly evident, Lovecraft not only did not plan out all (or any) of the details of his pseudomythology in advance, but also had no compunction whatever in altering its details when it suited him, never being bound by previous usage—something that later critics have also found infuriating, as if it were some violation of the sanctity or unity of a mythos that never had any sanctity or unity to begin with.

the barrage of old-fashioned poetry Toldridge sent to him helped to refine his views. In response to one such poem he wrote: It would be an excellent thing if you could gradually work out of the idea that this kind of stilted & artificial language is “poetical” in any way; for truly, it is not. It is a drag & hindrance on real poetic feeling & expression, because real poetry means spontaneous expression in the simplest & most poignantly vital living language. The great object of the poet is to get rid of the cumbrous & the emptily quaint, & buckle down to the plain, the direct, & the vital—the

...more

Lovecraft wrote what I might regard as his single most successful poem, “The Ancient Track.”

Charleston remains today one of the most well-preserved colonial oases on the eastern seaboard—thanks, of course, to a vigorous restoration and preservation movement that makes it today even more attractive than it was in Lovecraft’s day, when some of the colonial remains were in a state of dilapidation. Nearly everything that Lovecraft describes in his lengthy travelogue, “An Account of Charleston” (1930), survives, with rare exceptions.

“Medusa’s Coil” is as confused, bombastic, and just plain silly a work as anything in Lovecraft’s entire corpus. Like some of his early tales, it is ruined by a woeful excess of supernaturalism that produces complete chaos at the end, as well as a lack of subtlety in characterisation that (as in “The Last Test”) cripples a tale based fundamentally on a conflict of characters.

The sight of the Canadian countryside—with its quaint old farmhouses built in the French manner and small rustic villages with picturesque church steeples—was pleasing enough, but as he approached the goal on the train he knew he was about to experience something remarkable. And he did: Never have I seen another place like it! All my former standards of urban beauty must be abandoned after my sight of Quebec! It hardly belongs to the world of prosaic reality at all—it is a dream of city walls, fortress-crowned cliffs, silver spires, narrow, winding, perpendicular streets, magnificent vistas, &

...more

I last Wednesday [January 14] compleated the following work, design’d solely for my own perusal and for the crystallisation of my recollections, in 136 pages of this crabbed cacography . . .”[124] The work in question was: A DESCRIPTION OF THE TOWN OF QUEBECK, IN New-France, Lately added to His Britannick Majesty’s Dominions. It was the longest single work he would ever write. After a very comprehensive history of the region, there is a study of Quebec architecture (with appropriate drawings of distinctive features of roofs, windows, and the like), a detailed hand-drawn map of the principal

...more

Lovecraft was at work on a document that was actually was designed to be read by the general public: “The Whisperer in Darkness.” Although this would be among the most difficult in its composition of any of his major stories, this 25,000-word novelette—the longest of his fictions up to that time aside from his two “practice” novels—conjures up the hoary grandeur of the New England countryside even more poignantly than any of his previous works, even if it suffers from some flaws of conception and motivation.

But whereas such flaws of conception and execution cripple “The Dunwich Horror,” here they are only minor blemishes in an otherwise magnificent tale. “The Whisperer in Darkness” remains a monument in Lovecraft’s work for its throbbingly vital evocation of New England landscape, its air of documentary verisimilitude, its insidiously subtle atmosphere of cumulative horror, and its breathtaking intimations of the cosmic.

It does not appear as if Lovecraft has entirely thought through the role of Nyarlathotep in this story; and, to my mind, Nyarlathotep never gains a coherent personality in the whole of Lovecraft’s work. This is not entirely a flaw—certainly Lovecraft wished this figure to retain a certain nebulousness and mystery—but it makes life difficult for those who wish to tidy up after him.

By the early 1930s Lovecraft had resolved many of the philosophical issues that had concerned him in prior years; in particular, he had come to terms with the Einstein theory and managed to incorporate it into what was still a dominantly materialistic system. In so doing, he evolved a system of thought not unlike that of his later philosophical mentors, Bertrand Russell and George Santayana.

We all know that any emotional bias—irrespective of truth or falsity—can be implanted by suggestion in the emotions of the young, hence the inherited traditions of an orthodox community are absolutely without evidential value regarding the real “is-or-isn’tness” of things. . . . If religion were true, its followers would not try to bludgeon their young into an artificial conformity; but would merely insist on their unbending quest for truth, irrespective of artificial backgrounds or practical consequences. With such an honest and inflexible openness to evidence, they could not fail to receive

...more

Democracy, quantity and money over quality, foreigners, and mechanisation—these are the causes of America’s ruination. In all honesty, I am not at all inclined to dispute Lovecraft on the first, second, or fourth of these. In this same letter he elaborated upon his precise complaints about democracy, especially the mass democracy of his day. What he found offensive in it was its hostility to excellence.

Lovecraft came to believe that good art means the ability of any one man to pin down in some permanent and intelligible medium a sort of idea of what he sees in Nature that nobody else sees. In other words, to make the other fellow grasp, through skilled selective care in interpretative reproduction or symbolism, some inkling of what only the artist himself could possibly see in the actual objective scene itself.[32]

The end result—and this is a dim reflection of Oscar Wilde’s clever paradox that we see “more” of Nature in a painting of Turner’s than in the natural scene itself—is that “We see and feel more in Nature from having assimilated works of authentic art”; and so, “The constant discovery of different peoples’ subjective impressions of things, as contained in genuine art, forms a slow, gradual approach, or faint approximation of an approach, to the mystic substance of absolute reality itself—the stark, cosmic reality which lurks behind our varying subjective perceptions.”

At the Mountains of Madness, written in early 1931 (the autograph manuscript declares it to have been begun on February 24 and completed on March 22), is Lovecraft’s most ambitious attempt at “non-supernatural cosmic art”; it is a triumph in every way. At 40,000 words it is his longest work of fiction save The Case of Charles Dexter Ward; and just as his other two novels represent apotheoses of earlier phases of his career—The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath the culmination of Dunsanianism, Ward the pinnacle of pure supernaturalism—so is At the Mountains of Madness the greatest of his attempts

...more

Lovecraft’s science in this novel is absolutely sound for its period, although subsequent discoveries have made a few points obsolete. In fact, he was so concerned about the scientific authenticity of the work that, prior to its first publication in Astounding Stories (February, March, and April 1936), he inserted some revisions eliminating an hypothesis he had made that the Antarctic continent had originally been two land masses separated by a frozen channel between the Ross and Weddell Seas—an hypothesis that had been proven false by the first airplane flight across the continent, by Lincoln

...more

Lovecraft’s prime concern—beyond even verisimilitude and topographical realism—was a rigid adherence to Poe’s theory of unity of effect; that is, the elimination of any words, sentences, or whole incidents that do not have a direct bearing on the story. Accordingly, a character’s eating habits are wholly dispensed with because they are inessential to the denouement of a tale and will only dilute that air of tensity and inevitability which Lovecraft is seeking to establish.

the description of Tsathoggua is of interest: “He was very squat and pot-bellied, his head was more like that of a monstrous toad than a deity, and his whole body was covered with an imitation of short fur, giving somehow a vague suggestion of both the bat and the sloth. His sleep lids were half-lowered over his globular eyes; and the tip of a queer tongue issued from his fat mouth.”[78] Lovecraft generally followed this description in most of his citations of the god.

In late 1931 he estimated that his regular correspondents numbered between fifty and seventy-five.[86] But numbers do not tell the entire story. It certainly does seem as if Lovecraft—perhaps under the incentive of his own developing philosophical thought—was engaging in increasingly lengthy arguments with a variety of colleagues.

His letters are always of consuming interest, but on occasion one feels as if Lovecraft is having some difficulty shutting up.

the oldest continuously inhabited city in the United States, St Augustine, Florida. In the two weeks Lovecraft spent in St Augustine he absorbed all the antiquities the town had to offer.

he arrived at his ultimate destination, Key West. This was the farthest south Lovecraft would ever reach, although on this and several other occasions he yearned to hop on a boat and get to Havana,

this is predicated on Lovecraft’s habit of eating only two (very frugal) meals a day. He actually maintained that “my digestion raises hell if I try to eat oftener than once in 7 hours.”[20]

Lovecraft violently disliked John Collier’s “Green Thoughts,” but he never cared for the mingling of humour and horror, even the dark, sardonic humour of Collier.

“The Dreams in the Witch House” is also Lovecraft’s ultimate modernisation of a conventional myth (witchcraft) by means of modern science.

Few knew Lovecraft better at this period, on a personal level, than Harry Brobst. He would later gain a B.A. from Brown in psychology and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania.

Aside from Price’s, the only letters to Lovecraft we have in any abundance are those from Donald Wandrei, Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, C. L. Moore, and Ernest A. Edkins.

The next day the two of them went to Newburyport to see the total solar eclipse, and were rewarded with a fine sight: “The landscape did not change in tone until the solar crescent was rather small, & then a kind of sunset vividness became apparent. When the crescent waned to extreme thinness, the scene grew strange & spectral—an almost deathlike quality inhering in the sickly yellowish light.”[65]

Cook did, however, see Lovecraft on his return, and his portrait is as vivid a reflexion of Lovecraft’s manic travelling habits as one could ask for: Early the following Tuesday morning, before I had gone to work, Howard arrived back from Quebec. I have never before nor since seen such a sight. Folds of skin hanging from a skeleton. Eyes sunk in sockets like burnt holes in a blanket. Those delicate, sensitive artist’s hands and fingers nothing but claws. The man was dead except for his nerves, on which he was functioning. . . . I was scared. Because I was scared I was angry. Possibly my anger

...more

How Lovecraft could actually derive enjoyment from the places he visited, functioning on pure nervous energy and with so little food and rest, it is difficult to imagine; and yet, he did so again and again.

I fervently hope that “The Horror in the Museum” is a conscious parody—in

Long before his talentless disciples and followers unwittingly reduced the “Cthulhu Mythos” to absurdity, Lovecraft himself consciously did so.