More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

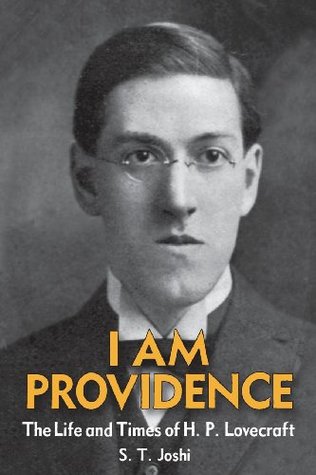

S.T. Joshi

Read between

October 19 - November 2, 2023

Throughout his life he believed alternately, and sometimes simultaneously, in an aristocracy of class and breeding and an aristocracy of intellect; very gradually the latter took over more and more, but he never renounced the former.

Lovecraft is very reticent about the causes or sources of what we can only regard as a full-fledged nervous breakdown in the summer of 1908.

The third statement, which states that he actually did graduate, is one of the few instances I have found where Lovecraft plainly lies about himself.

the period 1908–13 is a virtual blank in the life of H. P. Lovecraft. It is the only time in his life when we do not have a significant amount of information on what he was doing from day to day, who his friends and associates were, and what he was writing. It is also the only time of his life when the term “eccentric recluse”—which many have used with careless ignorance in reference to his entire life—can rightly be applied to him.

Later in life Lovecraft knew that, in spite of his lack of university education, he should have received training in some sort of clerical or other white-collar position that would at least have allowed him to secure employment rather than moping about at home: I made the mistake in youth of not realising that literary endeavour does not always mean an income.

Lovecraft’s wife, although she never knew Susie, makes a plausible claim that Susie “lavished both her love and her hate on her only child”;[20]

Mrs. Lovecraft talked continuously of her unfortunate son who was so hideous that he hid from everyone and did not like to walk upon the streets where people could gaze at him.

I busied myself at home with chemistry, literature, & the like . . . I shunned all human society, deeming myself too much of a failure in life to be seen socially by those who had known me in youth, & had foolishly expected such great things of me.”[43]

Lovecraft—who would not set foot outside of the three states of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut until 1921,[48] who would not sleep under a roof other than his own between 1901 and 1920,[49] and who (largely for economic reasons) never left the North American continent—must

One begins to develop the impression that Lovecraft was compulsive in whatever he did: his discovery of classical antiquity led him to write a paraphrase of the Odyssey, Iliad, and other works; his discovery of chemistry led him to launch a daily scientific paper; his discovery of astronomy led him to publish a weekly paper for years; and now his discovery of pulp fiction caused him to be a voracious reader of both the good and the bad, both the work that appealed to his special tastes and the work that did not.

it is a very clever poem, and reveals that penchant for stinging satire which would be one of the few virtues of his poetic output.

Amateur journalism was exactly the right thing for Lovecraft at this critical juncture in his life. For the next ten years he devoted himself with unflagging energy to the amateur cause, and for the rest of his life he maintained some contact with it. For someone so unworldly, so sequestered, and—because of his failure to graduate from high school and become a scientist—so diffident as to his own abilities, the tiny world of amateur journalism was a place where he could shine.

Lovecraft never tired of attacking the commercial spirit, whether in the amateur world or outside it.

Naturally, Lovecraft harps on some of his favourite topics, especially cosmicism. In speaking of the possibility that the farthest known star may be 578,000 light-years away, he notes: Our intellects cannot adequately imagine such a quantity as this. . . . Yet is it not improbable that all the great universe unfolded to our eyes is but an illimitable heaven studded with an infinite number of other and perhaps vastly larger clusters? To what mean and ridiculous proportions is thus reduced our tiny globe, with its vain, pompous inhabitants and arrogant, quarrelsome nations! (“[The Stars, Part

...more

The question again arises as to the sources for Lovecraft’s views. The anthropology of Huxley and others is a clear influence, and I have no doubt that his family played its role. Lovecraft, as a member of the New England Protestant aristocracy, would have come to such views as a matter of course, and he is only distinctive in expressing them in his early years with a certain vehemence and dogmatism.

This examination, if it survives, has not come to light, but its results make one much inclined to think that Lovecraft’s “ailments” were largely “nervous” or, to put it bluntly, psychosomatic.

I have already noted that among the great benefits Lovecraft claimed to derive from amateurdom was the association of sympathetic and like-minded (or contrary-minded) individuals. For one who had been a virtual recluse during the 1908–13 period, amateur journalism allowed Lovecraft a gradual exposure to human society—initially in an indirect manner (via correspondence or discussions in amateur papers), then by direct contact. It would take several years for him to become comfortable as even a limited member of human society, but the transformation did indeed take place; and some of his early

...more

Lovecraft, so far as I can tell, was not actually doing much during this period aside from writing; but he had discovered one entertaining form of relaxation—moviegoing. His enthusiasm for the drama had waned by around 1910, which roughly coincided with the emergence of film as a popular, if not an aesthetically distinguished, form of entertainment.

right from the beginning, Lovecraft intuitively adopted many of the principles of short-story technique that (as he himself points out in “Supernatural Horror in Literature”) Poe virtually invented and exemplified in his work—“such things as the maintenance of a single mood and achievement of a single impression in a tale, and the rigorous paring down of incidents to such as have a direct bearing on the plot and will figure prominently in the climax.” This “paring down” applies both to word-choice and to overall structure, and we will find that all Lovecraft’s tales—even those that might be

...more

it nevertheless stresses the fundamental way in which the short story differs from the novel: “A short-story produces a singleness of effect denied to the novel.” [14] This principle is manifestly derived from Poe,

suffice it to say that literature is fortunate for Lovecraft’s ultimate realisation that fiction, and not poetry or essays, was his chosen medium. His first several tales show remarkable promise, and they are the vanguard for the great work of the last decade of his life.

At one point he makes one of his noblest utterances, as he attempts to free Wickenden from the immortality myth: No change of faith can dull the colours and magic of spring, or dampen the native exuberance of perfect health; and the consolations of taste and intellect are infinite. It is easy to remove the mind from harping on the lost illusion of immortality. The disciplined mind fears nothing and craves no sugar-plum at the day’s end, but is content to accept life and serve society as best it may. Personally I should not care for immortality in the least. There is nothing better than

...more

For now it is of interest to realise the degree to which Lovecraft’s stories are already becoming intertextually related, a phenomenon that would continue with his later stories. It is, to be sure, unusual for an author to be so self-referential, and there is certainly no doubt about the thematic or philosophical unity of all Lovecraft’s work, from fiction to essays to poetry to letters; but it does not strike me as helpful to regard all his tales as interconnected on the level of plot—which they manifestly are not—or even in their glancing and frequently insignificant borrowings of names,

...more

At the outset it was one particular phase of Dunsany’s philosophy—cosmicism—that most attracted Lovecraft. He would maintain hyperbolically in “Supernatural Horror in Literature” that Dunsany’s “point of view is the most truly cosmic of any held in the literature of any period,” although later he would modify this opinion considerably. What is somewhat strange, therefore, is that Lovecraft’s own imitations are—with the sole exception of “The Other Gods”—not at all cosmic in scope, and rarely involve that interplay of “gods and men” which is so striking a characteristic of Dunsany’s early work.

“The Statement of Randolph Carter” remained a favourite of Lovecraft’s throughout his life, perhaps more because it captured a singularly distinctive and memorable dream than because it was a wholly successful weird tale.

It becomes clear from this passage that the principal cause, in the atheist Lovecraft’s mind, of the Puritans’ ills was their religion. In discussing “The Picture in the House” with Robert E. Howard in 1930, he remarks: “Bunch together a group of people deliberately chosen for strong religious feelings, and you have a practical guarantee of dark morbidities expressed in crime, perversion, and insanity.”[26]

“Ex Oblivione.” This work was published in the United Amateur for March 1921 under the “Ward Phillips” pseudonym, one of the few instances in which a story appeared under a pseudonym.

No one would deem “Herbert West—Reanimator” a masterpiece of subtlety, but it is rather engaging in its lurid way. It is also my belief that the story, while not starting out as a parody, became one as time went on. In other words, Lovecraft initially attempted to write a more or less serious, if quite “grewsome,” supernatural tale but, as he perceived the increasing absurdity of the enterprise, abandoned the attempt and turned the story into what it in fact was all along, a self-parody. The philosophical subtext of the story may bear out this interpretation. We have already seen that

...more

a 1929 letter he declares that the function of each work of art is to provide a distinctive vision of the world, in such a way that this vision becomes comprehensible to others: I’d say that good art means the ability of any one man to pin down in some permanent and intelligible medium a sort of idea of what he sees in Nature that nobody else sees. In other words, to make the other fellow grasp, through skilled selective care in interpretative reproduction or symbolism, some inkling of what only the artist himself could possibly see in the actual objective scene itself.

Half in earnest, half in jest I remarked, “What a lot of perfectly good affection to waste on a mere cat, when some woman might highly appreciate it!” His retort was, “How can any woman love a face like mine?” My counter-retort was, “A mother can and some who are not mothers would not have to try very hard.” We all laughed while Felis was enjoying some more stroking.[74]

It is not too early to remark here a feature that we will find again and again on Lovecraft’s journeys—the keenness of perception that allows him to absorb to the full the topographical, historical, and social features of regions that many of us might heedlessly pass over. Lovecraft was exceptionally alive to whatever milieu he found himself in, and this accounts both for raptures like the above and for the violence of his reaction to places like Chinatown, which defied all his norms of beauty, repose, and historic rootedness.

Sonia adds a startling note about what transpired the day after “The Horror at Martin’s Beach” was conceived: His continued enthusiasm the next day was so genuine and sincere that in appreciation I surprised and shocked him right then and there by kissing him. He was so flustered that he blushed, then he turned pale. When I chaffed him about it he said he had not been kissed since he was a very small child and that he was never kissed by any woman, not even by his mother or aunts, since he grew to manhood, and that he would probably never be kissed again. (But I fooled him.)[85]

And Lovecraft would later wonder why, around the age of thirty, his health suddenly began to improve! Freedom from his mother’s (and, to a lesser degree, his aunts’) stifling control, travel to different parts of the country, and the company of congenial friends who regarded him with fondness, respect, and admiration will do wonders for a cloistered recluse who never travelled more than a hundred miles away from home up to the age of thirty-one.

do not believe there was any condescension in this: Lovecraft’s friends surely knew of his lean purse, but their hospitality was both a product of their own kindness and their genuine fondness for Lovecraft and their desire to have him stay as long as possible. We shall find this becoming a repeated pattern in all Lovecraft’s peregrinations for the rest of his life.

Marblehead was—and, on the whole, today remains—one of the most charming little backwaters in Massachusetts, full of well-restored colonial houses, crooked and narrow streets, and a spectral hilltop burying-ground from which one can derive a magnificent panoramic view of the city and the nearby harbour. In the old part of town the antiquity is strangely complete, and very little of the modern intrudes there.

The most powerful emotional climax he had ever experienced—the high tide of his life: these statements were uttered after his marriage had begun and ended, after his two hellish years in New York and his ecstatic return to Providence, but before his sight of Charleston and Quebec in 1930, which in their way perhaps matched his Marblehead glimpse of 1922. What exactly was it about Marblehead that so struck him? Lovecraft clarifies it himself: with his tremendous imaginative faculty—and with the visible tokens of the present almost totally banished for at least a short interval—Lovecraft felt

...more

It would take Lovecraft nearly a year—and several more trips to Marblehead—to internalise his impressions and transmute them into fiction; but when he did so, in “The Festival” (1923), he would be well on his way to revivifying Mater Novanglia in some of the most topographically and historically rooted weird fiction ever written. He had begun haltingly to head in this direction, with “The Picture in the House”; but New England was still relatively undiscovered territory to him, and it would take many more excursions for him to imbibe the essence of the area—not merely its antiquities and its

...more

It is clear that Lovecraft functioned largely on nervous energy: he frequently admitted that he had no intrinsic interest in walking or other forms of exercise, but would undertake them only for some other purpose—in this case, the absorption of antiquity and, perhaps, the force-feeding of antiquity upon Moe, since just before his visit Moe had confessed that ancient things did not much attract him.

After Morton left, Lovecraft went home and slept for twenty-one hours continuously; later rests of eleven, thirteen, and twelve hours show how much the exertion of the Chepachet expedition, and perhaps of Morton’s trip generally, had told upon him. This would be a recurring pattern in Lovecraft’s travels—intense activity for several days, followed by collapse. But to someone who, largely for monetary reasons, needed to squeeze as much as he could out of a trip, it was a price well worth paying.

the summer of 1923 brought a radical change in Lovecraft’s literary career—perhaps as radical as his discovery of amateur journalism nine years previously.

Weird Tales never made any significant amount of money, and on several occasions—especially during the depression—it came close to folding; but somehow it managed to hang on for thirty-one years and 279 issues, an unprecedented run for a pulp magazine.

Temperamentally Machen was not at all similar to Lovecraft: an unwavering Anglo-Catholic, violently hostile to science and materialism, seeking always for some mystical sense of “ecstasy” that might liberate him from what he fancied to be the prosiness of contemporary life, Machen would have found Lovecraft’s mechanistic materialism and atheism repugnant in the extreme. They may have shared a general hostility to the modern age, but they were coming at it from very different directions.

And yet, because Machen so sincerely feels the sense of sin and transgression in those things that “religion brands with outlawry and horror,” he manages to convey his sentiments to the reader in such a way that his work remains powerful and effective. Lovecraft himself came to regard “The White People” as perhaps second to Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” as the greatest weird tale of all time; he may well be right.

It is difficult to convey the richness and cumulative horror of this story in any synopsis; next to The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, it is Lovecraft’s greatest triumph in the old-time “Gothic” vein—although even here the stock Gothic features (the ancient castle with a secret chamber; the ghostly legendry that proves to be founded on fact) have been modernised and refined so as to be chillingly convincing.

“The Rats in the Walls” is, technically, the first story Lovecraft wrote as a professional writer,

It is, in one sense, the pinnacle of his work in the Gothic/Poe-esque vein (it is, in effect, his “Fall of the House of Usher”), but in another sense it is very much a work of his own in its adumbration of such central themes as the influence of the past upon the present, the fragility of human reason, the baleful call of ancestry, and the ever-present threat of a reversion to primitive barbarism. It represents an exponential leap in quality from his past work, and he would produce nothing so good until “The Call of Cthulhu” in 1926.

“The Festival” (written probably in October[44]), which for the sustained modulation of its prose can be considered a virtual 3000-word prose-poem.

He passes by the old cemetery on the hill, where (in a literal borrowing from his letter of nearly a year previous) “black gravestones stuck ghoulishly through the snow like the decayed fingernails of a gigantic corpse,”

For Lovecraft, the eighteenth-century rationalist, the seventeenth century in Massachusetts—dominated by the Puritans’ rigid religion, bereft of the sprightliness of the Augustan wits, and culminating in the psychotic horror of the Salem witchcraft trials—represented an American “Dark Age” fully as horrifying as the early mediaeval period in Europe he so despised. Religion—seen by Lovecraft as the overwhelming of the intellect by emotion, childish wish-fulfilment, and millennia of pernicious brainwashing—proves to be the source of terror in “The Festival,”