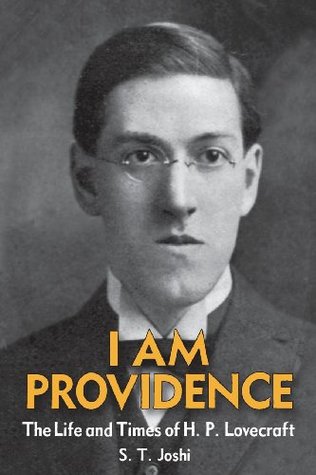

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

S.T. Joshi

Read between

October 19 - November 2, 2023

I don’t imagine that the publication of so large a biography of H. P. Lovecraft needs a defence today: his ascent into the canon of American literature with the publication of the Library of America edition of his Tales (2005), and, concurrently, his continued popularity among devotees of horror fiction, comics, films, and role-playing games suggest that Lovecraft will remain a compelling figure for decades to come.

Lovecraft, so keen on racial purity, was fond of declaring that his “ancestry was that of unmixed English gentry”;[67] and if one can include a Welsh (Morris) strain on his paternal side and an Irish (Casey) strain on his maternal, then the statement can pass.

What we do not find—as noted earlier and as Lovecraft frequently bemoaned—is much in the way of intellectual, artistic, or imaginative distinction. But if Lovecraft himself failed to inherit the business acumen of Whipple Phillips, he did somehow acquire the literary gifts that have resulted in a subsidiary fascination with his mother, father, grandfather, and the other members of his near and distant ancestry.

King Philip’s War (1675–76) was devastating to both sides, but particularly to the Indians (Narragansetts, Wampanoags, Sakonnets, and Nianticks), who were nearly wiped out, their pitiful remnants huddled together on a virtual reservation near Charlestown. The rebuilding of the white settlements that had been destroyed in Providence and elsewhere was slow but certain; from now on it would not be religious freedom or Indian warfare that would concern the white colonists, but economic development.

A colony of Jews had been present since the seventeenth century, but their numbers were small and they were careful to assimilate with the Yankees.

It is disturbing, but sadly not surprising, to note the increasing social exclusiveness and scorn of foreigners developing among the old-time Yankees throughout the nineteenth century. The Know-Nothing Party, with its anti-foreign and anti-Catholic bias, dominated the state during the 1850s. Rhode Island remained politically conservative into the 1930s, and Lovecraft’s entire family voted Republican throughout his lifetime. If Lovecraft voted at all, he also voted Republican almost uniformly until 1932.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born at 9 A.M.[5] on August 20, 1890, at 194 (renumbered 454 in 1895/96) Angell Street on what was then the eastern edge of the East Side of Providence. Although a Providence Lying-in Hospital had opened in 1885,[6] Lovecraft was born “at the Phillips home,”[7] and he would remain passionately devoted to his birthplace, especially after having to move from it in 1904.

In 1925 Lovecraft’s aunt Lillian gave him some idea of what he did as a new-born infant, and he responded to her remarks: “So I threw my arms about, eh, as if excited at the prospect of entering a new world? How naive! I might have known it would only be a bore. Perhaps, though, I was merely dreaming of a weird tale—in which case the enthusiasm was more pardonable.”[9] Neither Lovecraft’s cynicism nor his interest in weird fiction developed quite this early, but both, as we shall see, were of early growth and long standing.

My first memories are of the summer of 1892—just before my second birthday. We were then vacationing in Dudley, Mass., & I recall the house with its frightful attic water-tank & my rocking-horses at the head of the stairs. I recall also the plank walks laid to facilitate walking in rainy weather—& a wooded ravine, & a boy with a small rifle who let me pull the trigger while my mother held me.[14]

The sequence of Lovecraft’s parents’ residences seems, therefore, to be as follows: Dorchester, Mass. (12 June 1889?–mid-August? 1890) Providence, R.I. (mid-August? 1890–November? 1890) Dorchester, Mass. (November? 1890–winter? 1892) Dudley, Mass. (early June? 1892 [vacation, perhaps of only a few weeks]) Auburndale, Mass. (Guiney residence) (winter 1892–93) Auburndale, Mass. (rented quarters) (February?–April 1893)

At the age of two I was a rapid talker, familiar with the alphabet from my blocks & picture-books, & . . . absolutely metre-mad! I could not read, but would repeat any poem of simple sort with unfaltering cadence. Mother Goose was my principal classic, & Miss Guiney would continually make me repeat parts of it; not that my rendition was necessarily notable, but because my age lent uniqueness to the performance.[30]

Elsewhere Lovecraft states that it was his father who, with his taste for military matters, taught him to recite Thomas Buchanan Read’s “Sheridan’s Ride” at the Guiney residence, where Lovecraft declaimed it “in a manner that brought loud applause—and painful egotism.” Guiney himself seems to have taken to the infant; she would repeatedly ask, “Whom do you love?” to which Lovecraft would pipe back: “Louise Imogen Guiney!”[31]

The illness that struck Winfield Scott Lovecraft in April 1893 and forced him to remain in Butler Hospital in Providence until his death in July 1898 is worth examining in detail. The Butler Hospital medical record reads as follows: For a year past he has shown obscure symptoms of mental disease—doing and saying strange things at times; has, also, grown pale and thin in flesh. He continued his business, however, until Apr. 21, when he broke down completely while stopping in Chicago. He rushed from his room shouting that a chambermaid had insulted him, and that certain men were outraging his

...more

What was not known in 1898—and would not be known until 1911, when the spirochete that causes syphilis was identified—was the connexion between “general paresis” and syphilis.

M. Eileen McNamara, M.D., studying Winfield’s medical record, concluded that the probability of Winfield’s having tertiary syphilis is very strong:

Winfield Scott Lovecraft almost certainly died of syphilis.[40]

I suppose I heard people mentioning that my father was ‘an Englishman’ . . . My aunts remember that as early as the age of three I wanted a British officer’s red uniform, and paraded around in a nondescript ‘coat’ of brilliant crimson, originally part of a less masculine costume, and in picturesque juxtaposition with the kilts which with me represented the twelfth Royal Highland Regiment. Rule, Britannia![54]

At about the age of six, “when my grandfather told me of the American Revolution, I shocked everyone by adopting a dissenting view . . . Grover Cleveland was grandpa’s ruler, but Her Majesty, Victoria, Queen of Great Britain & Ireland & Empress of India commanded my allegiance. ‘God Save the Queen!’ was a stock phrase of mine.”[55]

Lovecraft had an idyllic and rather spoiled early childhood.

Lovecraft frequently emphasised the quasi-rural nature of his birthplace, situated as it was at what was then the very edge of the developed part of town: . . . I was born in the year 1890 in a small town, & in a section of that town which during my childhood lay not more than four blocks (N. & E.) from the actually primal & open New England countryside, with rolling meadows, stone walls, cart-paths, brooks, deep woods, mystic ravines, lofty river-bluffs, planted fields, white antient farmhouses, barns, & byres, gnarled hillside orchards, great lone elms, & all the authentick marks of a rural

...more

What is frequently ignored is that this return to Providence from Auburndale essentially allowed Lovecraft to grow up a native of Rhode Island rather than of Massachusetts, as he is very likely to have done otherwise;

Lovecraft retained a passionate fondness for Massachusetts and its colonial heritage, finding wonder and pleasure in the towns of Marblehead, Salem, and Newburyport, and the wild rural terrain of the western part of the state. But the heritage of religious freedom in Rhode Island, and the contrasting early history of Puritan theocracy in its northeasterly neighbour, caused Massachusetts to become a sort of topographical and cultural “other”—attractive yet repulsive, familiar yet alien—in both his life and his work. It is not too early to stress that many more of Lovecraft’s tales are set in

...more

This combination of wonder and terror in Lovecraft’s early appreciation of Providence makes me think of a letter of 1920 in which he attempts to specify the foundations of his character: “. . . I should describe mine own nature as tripartite, my interests consisting of three parallel and dissociated groups—(a) Love of the strange and the fantastic. (b) Love of the abstract truth and of scientific logick. (c) Love of the ancient and the permanent. Sundry combinations of these three strains will probably account for all my odd tastes and eccentricities.”[71]

The result was an infatuation with the classical world and then a kind of religious epiphany. Let Lovecraft tell it in his own inimitable way: When about seven or eight I was a genuine pagan, so intoxicated with the beauty of Greece that I acquired a half-sincere belief in the old gods and Nature-spirits. I have in literal truth built altars to Pan, Apollo, Diana, and Athena, and have watched for dryads and satyrs in the woods and fields at dusk. Once I firmly thought I beheld some of these sylvan creatures dancing under autumnal oaks; a kind of “religious experience” as true in its way as the

...more

Earlier in this essay he reports that “I was instructed in the legends of the Bible and of Saint Nicholas at the age of about two, and gave to both a passive acceptance not especially distinguished either for its critical keenness or its enthusiastic comprehension.” He then declares that just before the age of five he was told that Santa Claus does not exist, and that he thereupon countered with the query as to “why God is not equally a myth.” “Not long afterwards,” he continues, he was placed in a Sunday school at the First Baptist Church, but became so pestiferous an iconoclast that he was

...more

From the age of three onward—while his father was slowly deteriorating both physically and mentally in Butler Hospital—the young Howard Phillips Lovecraft was encountering one intellectual and imaginative stimulus after the other: first the colonial antiquities of Providence, then Grimm’s Fairy Tales, then the Arabian Nights, then Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, then eighteenth-century belles-lettres, then the theatre and Shakespeare, and finally Hawthorne, Bulfinch, and the classical world. It is a remarkable sequence, and many of these stimuli would be of lifelong duration. But there remained

...more

Aside from discovering Poe and giving his fledgling fictional career a boost, Lovecraft also found himself in 1898 fascinated with science. This is the third component of what he described as his tripartite nature: love of the strange and fantastic, love of the ancient and permanent, and love of abstract truth and scientific logic. It is perhaps not unusual that it would be the last to emerge in his young mind, and it is still remarkable that it emerged so early and was embraced so vigorously.

“At school I was considered a bad boy, for I would never submit to discipline. When censured by my teacher for disregard of rules, I used to point out to her the essential emptiness of conventionality, in such a satirical way, that her patience must have been quite severely strained; but withal she was remarkably kind, considering my intractable disposition.”[28] Lovecraft certainly got an early start as a moral relativist.

That Lovecraft was a smart-aleck would be a considerable understatement. But school was the least significant of Lovecraft’s and his friends’ concerns; they were primarily interested—as all boys of that age, however precocious, are—in playing. And play they did.

Lovecraft always regretted his insensitivity to classical music, but he also found tremendous nostalgic relish in recalling the popular songs of his boyhood—and recall them he did. It was, let us remember, because he was “forever whistling & humming in defiance of convention & good breeding”[43]

Lovecraft was slow to make friends, but once he made them he remained firm and devoted. This is a pattern that persisted throughout his life, and in fact he became still more forthcoming with his time, knowledge, and friendship by means of correspondence, writing enormous treatises to perfect strangers when they had asked him a few simple questions or made some simple requests.

But Lovecraft’s days of innocence came to an abrupt end. Whipple Phillips’s Owyhee Land and Irrigation Company had suffered another serious setback when a drainage ditch was washed out by floods in the spring of 1904; Whipple, now an old man of seventy, cracked under the strain, suffering a stroke and dying on March 28, 1904.

His death brought financial disaster besides its more serious grief. . . . [W]ith his passing, the rest of the board [of the Owyhee Land and Irrigation Company] lost their initiative & courage. The corporation was unwisely dissolved at a time when my grandfather would have persevered—with the result that others reaped the wealth which should have gone to its stockholders. My mother & I were forced to vacate the beautiful estate at 454 Angell Street, & to enter the less spacious abode at 598, three squares eastward.[48] This was probably the most traumatic event Lovecraft experienced prior to

...more

psychologically the loss of his birthplace, to one so endowed with a sense of place, was shattering.

To compound the tragedy, Lovecraft’s beloved black cat, Nigger-Man, disappeared sometime in 1904. This was the only pet Lovecraft ever owned in his life,

Was Lovecraft actually contemplating suicide? It certainly seems so—and, incidentally, this seems virtually the only time in Lovecraft’s entire life (idle speculation by later critics notwithstanding) when he seriously thought of self-extinction.

This is a defining moment in the life of H. P. Lovecraft. How prototypical that it was not family ties, religious beliefs, or even—so far as the evidence of the above letter indicates—the urge to write that kept him from suicide, but scientific curiosity. Lovecraft may never have finished high school, may never have attained a degree from Brown University, and may have been eternally ashamed of his lack of formal schooling; but he was one of the most prodigious autodidacts in modern history, and he continued not merely to add to his store of knowledge to the end of his life but to revise his

...more

there is much doubt as to what Lovecraft’s voice actually sounded like—it

at this time Lovecraft himself developed an interest in firearms. Recall that during the initial creation of the Providence Detective Agency he himself, unlike the other boys, sported a real revolver. Lovecraft evidently amassed a fairly impressive collection of rifles, revolvers, and other firearms: “After 1904 I had a long succession of 22-calibre rifles, & became a fair shot till my eyes played hell with my accuracy.”[74]

Rifle-shooting was, however, the only sport that might remotely be said to have interested Lovecraft. Other team or individual sports he shunned with disdain as unfit for an intelligent person.

nothing would inspire his scorn or disgust more quickly than an offer to play cards or do crossword puzzles or watch a sporting event.

The whole issue of Lovecraft’s racism is one I shall have to treat throughout this book; it is an issue that cannot be dodged, but it is also one that we must attempt to discuss—difficult as it may be—without yielding to emotionalism and by placing Lovecraft’s views in the context of the prevailing intellectual currents of the time.

Recall Winfield Scott Lovecraft’s hallucinations regarding a “negro” who was molesting his wife; it is conceivable that he could have passed on his prejudice against blacks even to his two-year-old son.

To the end of his life Lovecraft retained a belief in the biological (as opposed to the cultural) inferiority of blacks, and maintained that a strict colour line must be enforced in order to prevent miscegenation. This view began to emerge in the late eighteenth century—both Jefferson and Voltaire were convinced of the black’s biological inferiority—and gained ground throughout the nineteenth century.

I do not cite these passages in extenuation of Lovecraft but to demonstrate how widely, in 1905, such views were prevalent even among the intellectual classes. New Englanders were particularly hostile to foreigners and blacks, for a variety of reasons, largely economic and social.

Lovecraft’s sympathy for the Southern cause in the Civil War was of very long standing and would persist throughout his life. He states that he and Harold Munroe were “Confederates in sympathy, & used to act out all the battles of the War in Blackstone Park.”[92]

The scientific refutation of racism was only beginning at the turn of the century, led by the pioneering work of Franz Boas (1858–1942) and others under his direction.

Like many of Lovecraft’s later protagonists, outward rationalism collapses in the face of the unknown.

years of astronomical study triggered the “cosmicism” that would form so central a pillar of both his philosophical and aesthetic thought:

By my thirteenth birthday I was thoroughly impressed with man’s impermanence and insignificance, and by my seventeenth, about which time I did some particularly detailed writing on the subject, I had formed in all essential particulars my present pessimistic cosmic views. The futility of all existence began to impress and oppress me; and my references to human progress, formerly hopeful, began to decline in enthusiasm. (“A Confession of Unfaith”)