Manetho (/ˈmænɪθoʊ/; Koinē Greek: Μανέθων Manéthōn, gen.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos (Coptic: Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, romanized: Čemnouti[2]) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third century BC, during the Hellenistic period.

He authored the Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) in Greek, a major chronological source for the reigns of the kings of ancient Egypt. It is unclear whether he wrote his history and king list during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter or Ptolemy II Philadelphos, but it was completed no later than that of Ptolemy III Euergetes.

The original Egyptian version of Manetho's name is lost, but some speculate it means "Truth of Thoth", "Gift of Thoth", "Beloved of Thoth", "Beloved of Neith", or "Lover of Neith".[3] Less accepted proposals are Myinyu-heter ("Horseherd" or "Groom") and Ma'ani-Djehuti ("I have seen Thoth").

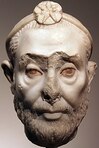

In the Greek language, the earliest fragments (the inscription of uncertain date on the base of a marble bust from the te

[close]

Manetho (/ˈmænɪθoʊ/; Koinē Greek: Μανέθων Manéthōn, gen.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos (Coptic: Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ, romanized: Čemnouti[2]) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third century BC, during the Hellenistic period.

He authored the Aegyptiaca (History of Egypt) in Greek, a major chronological source for the reigns of the kings of ancient Egypt. It is unclear whether he wrote his history and king list during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter or Ptolemy II Philadelphos, but it was completed no later than that of Ptolemy III Euergetes.

Name

The original Egyptian version of Manetho's name is lost, but some speculate it means "Truth of Thoth", "Gift of Thoth", "Beloved of Thoth", "Beloved of Neith", or "Lover of Neith".[3] Less accepted proposals are Myinyu-heter ("Horseherd" or "Groom") and Ma'ani-Djehuti ("I have seen Thoth").

In the Greek language, the earliest fragments (the inscription of uncertain date on the base of a marble bust from the temple of Serapis at Carthage[4] and the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus of the 1st century AD) wrote his name as Μανέθων Manethōn, so the Latinised rendering of his name here is given as Manetho.[5] Other Greek renderings include Manethōs, Manethō, Manethos, Manēthōs, Manēthōn, and Manethōth. In Latin it is written as Manethon, Manethos, Manethonus, and Manetos.[citation needed]

Life and work

Although no sources for the dates of his life and death remain, Manetho is associated with the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC) by Plutarch (c. 46–120 AD), while George Syncellus links Manetho directly with Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC).

That Manetho links himself directly to Ptolemy II is depicted in Ptolemy Philadelphus in the Library of Alexandria by Vincenzo Camuccini (1813)

If the mention of someone named Manetho in the Hibeh Papyri, dated to 241/240 BC, is in fact the celebrated author of the Aegyptiaca, then Manetho may well have been working during the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes (246–222 BC) as well, but at a very advanced age. Although the historicity of Manetho of Sebennytus was taken for granted by Josephus and later authors, the question as to whether he existed remains problematic. The Manetho of the Hibeh Papyri has no title and this letter deals with affairs in Upper Egypt not Lower Egypt, where our Manetho is thought to have functioned as a chief priest. The name Manetho is rare, but there is no reason a priori to presume that the Manetho of the Hibeh Papyri is the priest and historian from Sebennytus who is thought to have authored the Aegyptiaca for Ptolemy Philadelphus.

Manetho is described as a native Egyptian, and Egyptian would have been his mother tongue. Although the topics he supposedly wrote about dealt with Egyptian matters, he is said to have written exclusively in the Greek language for a Greek-speaking audience. Other literary works attributed to him include Against Herodotus, The Sacred Book, On Antiquity and Religion, On Festivals, On the Preparation of Kyphi, and the Digest of Physics. The treatise Book of Sothis has also been attributed to Manetho. These works are not attested during the Ptolemaic period when Manetho of Sebennytus is said to have lived and are only mentioned in another source in the first century AD, leaving a gap of 200–300 years between the composition of the Aegyptiaca and its first attestation. The gap is even larger for the other works attributed to Manetho such as The Sacred Book that is mentioned for the very first time by Eusebius in the fourth century AD.[6]

Manetho of Sebennytus was probably a priest of the sun-god Ra at Heliopolis (according to George Syncellus, he was the chief priest). He was considered by Plutarch to be an authority on the cult of Serapis (a derivation of Osiris and Apis). Serapis was a Greco-Macedonian version of the Egyptian cult, probably started after Alexander the Great's establishment of Alexandria in Egypt. A statue of the deity was imported in 286 BC by Ptolemy I Soter (or in 278 BC by Ptolemy II Philadelphus) as Tacitus and Plutarch attest.[7] There was also a tradition in antiquity that Timotheus of Athens (an authority on Demeter at Eleusis) directed the project together with Manetho, but the source of this information is not clear and it may originate from one of the literary works attributed to Manetho, in which case it has no independent value and does not corroborate the historicity of Manetho the priest-historian of the early third century BC.

Aegyptiaca

The Aegyptiaca (Αἰγυπτιακά, Aigyptiaka), the "History of Egypt", may have been Manetho's largest work, and certainly the most important. It was organised chronologically and divided into three volumes. His division of rulers into dynasties was an innovation. However, he did not use the term in the modern sense, by bloodlines, but rather, introduced new dynasties whenever he detected some sort of discontinuity, whether geographical (Dynasty Four from Memphis, Dynasty Five from Elephantine), or genealogical (especially in Dynasty One, he refers to each successive king as the "son" of the previous to define what he means by "continuity"). Within the superstructure of a genealogical table, he fills in the gaps with substantial narratives of the kings.

Some have suggested[citation needed] that Aegyptiaca was written as a competing account to Herodotus' Histories, to provide a national history for Egypt that did not exist before. From this perspective, Against Herodotus may have been an abridged version or just a part of Aegyptiaca that circulated independently. Neither survives in its original form today.

Two English translations of the fragments of Manetho's Aegyptiaca have been published: by William Gillan Waddell in 1940, and by Gerald P. Verbrugghe and John Moore Wickersham in 2001.[8]

Transmission and reception

Despite the reliance of Egyptologists on him for their reconstructions of the Egyptian dynasties, the problem with a close study of Manetho is that not only was Aegyptiaca not preserved as a whole, but it also became involved in a rivalry among advocates of Egyptian, Jewish, and Greek histories in the form of supporting polemics. During this period, disputes raged concerning the oldest civilizations, and so Manetho's account was probably excerpted during this time for use in this argument with significant alterations. Material similar to Manetho's has been found in Lysimachus of Alexandria, a brother of Philo, and it has been suggested[citation needed] that this was inserted into Manetho. We do not know when this might have occurred, but scholars[citation needed] specify a terminus ante quem at the first century AD, when Josephus began writing.

The earliest surviving attestation to Manetho is that of Contra Apionem ("Against Apion") by Flavius Josephus, nearly four centuries after Aegyptiaca was composed. Even here, it is clear that Josephus did not have the originals, and constructed a polemic against Manetho without them. Avaris and Osarseph are both mentioned twice (1.78, 86–87; 238, 250). Apion 1.95–97 is merely a list of kings with no narratives until 1.98, while running across two of Manetho's dynasties without mention (dynasties eighteen and nineteen).

Contemporaneously or perhaps after Josephus wrote, an epitome of Manetho's work must have been circulated. This would have involved preserving the outlines of his dynasties and a few details deemed significant. For the first ruler of the first dynasty, Menes, we learn that "he was snatched and killed by a hippopotamus". The extent to which the epitome preserved Manetho's original writing is unclear, so caution must be exercised. Nevertheless, the epitome was preserved by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius of Caesarea. Because Africanus predates Eusebius, his version is usually considered more reliable, but there is no assurance that this is the case. Eusebius in turn was preserved by Jerome in his Latin translation, an Armenian translation, and by George Syncellus. Syncellus recognized the similarities between Eusebius and Africanus, so he placed them side by side in his work, Ecloga Chronographica.

Africanus, Syncellus, and the Latin and Armenian translations of Eusebius are what remains of the epitome of Manetho. Other significant fragments include Malalas's Chronographia and the Excerpta Latina Barbari, a bad translation of a Greek chronology.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manetho