J. Mark Bertrand's Blog

February 4, 2013

Help Me Give Away My Book: Download Back on Murder for free

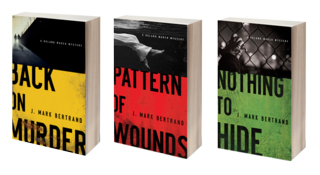

If you love my Roland March series and wish you could introduce more people to the dogged and depressed Houston homicide cop, here's a perfect opportunity. Since Friday, the first book in the series, Back on Murder, has been available as a free e-book on a variety of platforms -- Kindle, Nook, and more. The goal in sharing the book this way is to hook more readers on the series. Over the weekend, Back on Murder became the #1 free title in Amazon's Kindle Store. Those numbers fluctate all the time, but it's good to know more readers are discovering Roland March for the first time.

Publishers Weekly called the world of Roland March "gritty and chilling," and Books & Culture editor John Wilson declared this "a series worth getting attached to." The three novels in the Roland March series are, in order of publication:

Back on Murder (2010)

Pattern of Wounds (2011)

Nothing to Hide (2012)

The stories focus on March's life and career as he investigates a gang-related murder somehow connected to a missing teenage girl, a knife-wielding serial killer stalking Houston's affluent West University neighborhood, and a deadly conspiracy involving the FBI and the Mexican cartels. The novels have been praised for their realism, for their writing, and for engaging thoughtfully with serious themes.

If you haven't read Back on Murder yet, download the free e-book and give it a try. If you like it, both of the follow-up volumes are available as specially priced e-books, too. If you're already a fan, share the news with your friends. You'll make this crime novelist very happy indeed.

October 2, 2012

How to Write: Sir Steven Runciman's Method

One of the pleasures of the novel I'm working on, which is set partly in the fifteenth century, is that it gives me an excuse to re-read Sir Steven Runciman. Since, in addition to being an historian, Runciman was also a lovely prose stylist, I found his answer to the question "How do you write, when you're writing a book?" quite interesting:

"Well, I do most of my writing when I’m walking about, until I get fairly clear what I want to say and how to say it. I then sit in front of an old typewriter –– I type very slowly because I’ve never been taught how to type properly––and I mutter as I go along to make it sound right. And then I –– I don’t need to make very many corrections, because I usually send that first draft to the publishers."

Now one of the things authors (myself included) will tell aspiring writers is, don't send your first draft to the publisher. You should revise and rewrite, making sure everything's perfect. As with most writing advice, however, this doesn't take into account other ways of working. The assumption is that first drafts are always bad. But Runciman's method sounds literally peripathetic. He walked around, thinking of what he wanted to say (and how to say it), and only then sat down to write. And as he wrote, he muttered the words aloud to get them to sound right. In other words, what many authors do after the fact -- or not at all -- Runciman did in before and during the writing process.

What matters isn't how you do it but what you get done. If you've ever read Sir Steven Runciman, you know his method produced marvelous results. Here's the entire interview:

September 21, 2012

"The key to realism is a vivid imagination."

September 20, 2012

Top 5 Crime Shows on TV (British Style)

When I made my Top 5 list of American crime shows on television, I promised to do the same thing for the Brits. This list reaches farther back into history, mainly because I loved British crime shows long before American ones were worth watching. As before, the idea isn't to put out an objective canon. These just happen to be the shows that switched a light on for me.

To be honest, this shouldn't be on the list. I'm not a fan of CSI-style forensics shows, cold case files, or episodic stories. But Waking the Dead has one redeeming quality that counteracts everything: Trevor Eve as Boyd. He's having fun chewing up the scenery, and I'm having fun with him.

4. Conviction

As in the American list, I had to throw in a mini-series. The coppers in Conviction are real people. Their mistakes lead to real moral dilemmas. This series also illustrates one of the reasons I like crime fiction in general: the scale of the action and what's at stake don't have to be monumental for the drama to be seriously absorbing.

3. Foyle's War

Given my thing for anti-heroes, this may be a surprising choice. But hey -- great theme music, great sidekicks, and above all, Michael Kitchen as Foyle, a plausible moral stalwart (which is not easy to pull off these days). This eccentric fly-fishing Detective Chief Superintendent is always delivering sermons to his bureaucratic and social superiors, and I love 'em all. Even when justice can't be done -- as when the killer turns out to be essential to the war effort -- Foyle says, "Fine, I'll nick you when the war is over." The way Kitchen delivers his lines -- that alone is worth the price of admission.

2. Cracker

I identify with Fitz way too much. I even like his sense of style. While Robbie Coltrane is clearly the show-stopper, there are some impressive supporting characters: the despicable Jimmy Beck, DCI Billborough with his "dying man's statement," a host of soon-to-be-famous guest stars. Memory plays tricks: re-watching Cracker, I'm astonished how few episodes there are relative to the number of scenes this show etched on my mid-90s brain.

This should come as no surprise. Season 5, with Steven Mackintosh as The Street, is my favorite, but they're all pretty great. Helen Mirren as DCI Jane Tennison is simply iconic. She manages to be selfish, ambitious, all too human, yet utterly sympathetic. Prime Suspect was the first crime show I can remember watching that clearly cared about its craft. I adored it and still do.

* * *

Now that I've started, I'm thinking of so many shows I'm leaving out. But that's the nature of the beast. What do you think? Have I omitted something brilliant?

September 19, 2012

The End (Or Is It?)

What if Philip Marlowe had lived in Berlin in the 1930s instead of LA? Novelist Philip Kerr explored the question in a trio of novels written in the late 80s, with his Marlowe stand-in Bernie Gunther. The Berlin Noir trilogy achieved cult status over the years. My copy of the Penguin omnibus has been read and re-read. As far as anyone knew, Gunther's adventures had ended. Then, fifteen years later, Kerr started adding to the series. With the most recent release, Prague Fatale, he has added five more books to the series, bringing the total to eight. I'm a big fan of these books. The series is well worth following.

When readers ask me about the future of the Roland March series, Berlin Noir is what comes to mind. The three novels in print -- Back on Murder, Pattern of Wounds, and Nothing to Hide -- complete the original contract signed with the publisher. They can be read as a trilogy, but they weren't written to end that way. I have plans for future installments, assuming another publisher is willing to take the series on. If people want to see more of March, they will. It's up to the readers.

In the meantime, I'm looking forward to more from Kerr. If you haven't checked out these books yet, you really should:

September 18, 2012

Louis Malle and the Interrogative Method

I came across some great advice on writing, in of all places the September issue of Vogue. Tucked between the full-color ads is playwright David Hare's account of how he came to write the screenplay for Louis Malle's film Damage. After intruding on Hare's St. Tropez vacation after inducing him to read the novel by Josephine Hart, Malle asked him to recount the story of the book over breakfast -- an effort that ended up stretching into late afternoon. Malle would interrupt every few moments with questions -- clarify this, explain that slowing the progress so much that, on Day 1, Hare barely made it through the first six pages of the book.

Over the course of ten days, the process repeated itself. Hare told the story while Malle pushed and prodded. Each day, he insisted that Hare begin at the beginning. For the playwright, the whole thing was excruciating. But as he complied, something began to change:

"...after three or four days, even I had to admit that I was becoming like an Olympic athlete whose punishing hours of training were bringing unnoticed rewards. Much to my surprise, my muscles were starting to ripple. I could even get through whole sentences without interruption. It was as if Louis and I were laying down planks over marshy ground and together finding a path. Slowly we constructed a watertight narrative, which was secured by the oddest of means: endless repetition. The more often I told the story out loud, the more natural its logic and development seemed to become.

"At the end of the ten days, I was able, without notes, to recount the entire story of the book in approximately 20 minutes. My listener did nothing more than light and relight his pipe throughout. When, for the final time, I got to the dramatic end, our hero disgraced and in lifelong exile, Louis beamed with pleasure and said, 'Well, you might as well write it now. After all, you've done all the work. The script itself will be a formality.'"

This way of proceeding, Hare says, is what he came to know as the interrogative method. It reminds me of a formative experience I had in Dan Stern's novel writing workshop in the early 90s, just a few years after the event Hare recounts. Short story workshops abound, while novel workshops are rare. As a result, I enrolled with enthusiasm, imagining myself completing a novel during the course of the semester.

Class after class, I would bring in my ambitious chapters, only to have Stern shoot them down. He would ask me questions about the main character, the setting, the background, focusing on minor, even pointless details. Sometimes I answered with a shrug. Sometimes I gamely invented details whose inconsistency testified to their improvisation. "You don't know the story," Stern would conclude. "You should know these things."

If I'd had ten days one-on-one with Stern, I might have developed the Olympic muscles Hare alludes to. But I didn't. I experienced the frustration, but only learned the lesson much later. In a sense, I was writing too soon, before I knew what I was writing about. I was making things up as I went, and it showed.

When it comes to the novel, you write it twice: first at the story level, and then at the sentence level. How this is accomplished varies from writer to writer. The interrogative method sounds like an interesting thing to try.

September 17, 2012

Noir as Moral Instruction

“I suspect we’re near the end of the glamor days of juvenile delinquency. I think a very unusual crop of kids is coming along. Good kids, but strange. They’ve become bored with the dissipations of their elders and the animal philosophies of their contemporaries. They are tired of using the bogeyman of military service as a built-in excuse for riot and disorder. This is a very moral crop of kids. They are sophisticates, but they practice moderation by choice. They seem to have a sense of moral purpose and decent goals, which, God knows, is something difficult to find in the here and now. They are all right. But they appall me a little. They make me feel like a doddering degenerate.”

John D. MacDonald

The Executioners, p. 85

John D. MacDonald’s 1957 novel The Executioners served as the basis for Cape Fear, the 1962 thriller starring Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. At the novel’s mid-point, inspired by a conversation with his daughter Nancy's new boyfriend, protagonist Sam Bowden gives the speech quoted above about the new generation, which might serve as a epithet for the soon-to-come Camelot era.

Reading it for the first time this week, however, I was reminded of the op-ed piece David Brooks penned for the New York Times back in April, “Sam Spade at Starbucks,” which expressed some doubt that today’s young do-gooders have an accurate read on human nature, something they could correct by reading some noir fiction. Brooks doesn’t mention The Executioners by name. He should have, because MacDonald's Sam Bowden is very much an idealist confronted by a force of (fallen) nature, a harsh reality not dreamt of in his philosophy of law and order.

Reading it for the first time this week, however, I was reminded of the op-ed piece David Brooks penned for the New York Times back in April, “Sam Spade at Starbucks,” which expressed some doubt that today’s young do-gooders have an accurate read on human nature, something they could correct by reading some noir fiction. Brooks doesn’t mention The Executioners by name. He should have, because MacDonald's Sam Bowden is very much an idealist confronted by a force of (fallen) nature, a harsh reality not dreamt of in his philosophy of law and order.

Bowden is a morally upright attorney who, despite his sophistication, believes in the law. When a menace from his past, convicted rapist Max Cady, gets out of jail and seeks out Bowden for revenge, the lawyer learns just how thick a blindfold Lady Justice wears. To protect his family, he is forced to go outside the law, which does not come easily. The clean cut boyfriend might make gin-and-tonic-sipping Bowden feel like a degenerate, but by most standards he’s a saint. (He’s played in the movie by Atticus Finch. What more evidence do you need?)

Above: Peck (left) freezes Mitchum with his moral glare.

I’m forty-two years old. I spend a fair amount of time in the company of the younger generation, and there’s something the resonates with me both in Brooks’ op-ed and Bowden’s speech. It has to do with the youthful assurance of moral certainty. The appeal of noir, from a theological and moral standpoint, is that it offers a version of reality pretty much cleansed of such certitude. Noir fiction doesn’t assume a Manichean division between good and evil. It acknowledges the individual and systemic extent of human corruption, which touches even the good guys.

Over the past week, apropos the recent riots throughout the Middle East, I’ve seen a quotation of Steven Weinberg’s paraphrased numerous times, to the effect that good people do good things, evil people do evil things, but for good people to do evil things, that takes religion. It’s one of those pithy rhetorical statements that sounds pretty good until you stop and think. In melodrama, the human race is divided up between the good and the evil, the white hats and the black. The good tribe battles the bad tribe––if only they could be snuffed out, everything would be fine. Reality is a bit more complicated. To snuff out evil, you’d have to get rid of us all.

Nancy Bowden's English teacher, Miss Boyce, knows better. According to her, there’s a link between good fiction and moral perception.

“Good fiction is good,” Nancy relates, “because is has character development in it that shows that nobody is completely good and nobody is completely evil. And in bad fiction the heroes are a hundred percent heroic and the villains are a hundred percent bad.”

To Nancy, her father’s nemesis Max Cady seems to be the exception. “But I think that man is all bad.” MacDonald, pulp novelist, is having some fun here, of course. But Sam Bowden is quick to correct his daughter. There are reasons behind Cady’s actions, justifications. And as his own compromises illustrate, Bowden is a dab hand at rationalization, too. A man will do what he has to do to keep his family safe, law or no law.

Societal solutions that rely on an alliance of the good people against the bad are naive (at best) because they tend to be especially blind to the evil they themselves do. These are the evils which the noir mindset can’t help bringing to light. David Brooks is right to recommend Chandler, Hammett and others as a corrective to un-nuanced optimism. And Sam Bowden is right to be a little appalled by this “very moral crop of kids.” If there’s one thing noir can teach you, it’s never to get too comfortable in the presence of those who think they’re always in the right.

September 15, 2012

Top 5 Crime Shows on TV (American-Style)

Ranking my favorite crime shows on TV really kills me. For one thing, I don't like countdown lists. By nature I am a thumbs-up/thumbs-down kind of guy who doesn't spend a lot of time worrying about the finer shades of appreciation. I tend to love whatever I like, and whatever I dislike I loathe.

For another thing, television is a mind-eroding force for evil. It's one thing to enjoy TV and quite another to praise it. (I am being facetious here.) Nevertheless, we seem to be living in a golden age of television, mainly because -- if you'll excuse a novelist saying so -- the best shows have become so much more novelistic. Episodic structure is on the wane now that the series arc has been discovered, which means character and plot development loom larger than mere premise.

Since I'm a crime novelist, I'll focus on my top picks for crime shows. This list will also focus on recent American endeavors. Later, I will come clean with my top British picks as well.

5. Thief

This is cheating, because Thief is technically mini-series, but to my mind it exemplifies everything that's good with the best crime shows these days. It's a drum-tight little work of art. Andre Braugher is in the lead, and he delivers. The storyline is intricate and takes its time to unpack. The visual style makes Thief interesting to watch, too -- in contrast to so much television, which so often forgets it's a visual medium.

4. The Shield

Vic Mackey is a corrupt copper with a heart of gold. He gets the Stike Team into deeper trouble every season, which leads to more and more No Way Out-style episodes. What's fresh about The Shield is its sympathetic portrayal of cops who, in a more traditional procedural, would be the bad guys.

3. Dexter

I hate the serial killer fascination, so the idea of a serial killer who, because of his "code," only preys on other serial killers strikes me as a great send-up of the genre. Dexter pays attention to its craft on every level, from the storytelling to the performances to the photography. It also manages to explore interesting moral questions, something I appreciate in art.

2. The Wire

Audacity is the only word to describe The Wire. This show dramatizes the parts of policework the others skip over -- and makes them fascinating. It gets inside a world most cop shows don't seem to realize exists. And just when you think it can't take any more risks, you get a whole season in which the main characters become minor characters, taking a back seat to a group of high school kids. America, we don't deserve television this good. We haven't earned it.

1. Breaking Bad

A high school science teacher diagnosed with terminal cancer starts cooking meth to provide for his family after he’s gone, only it’s the most chemically pure meth anyone has seen, leading to high demand and a whole lot of trouble. Done. I'm all in. And this show really cares about its craft:

Again, the moral questions explored are gripping. Jesse Pinkman's Season 4 speech at the NA meeting about responsibility for your actions is one of those places most shows never earn the right to go.

* * *

Well, that's it. Did I leave something essential out or get them in the wrong order? Let me know.

September 14, 2012

Things You Must Not Do, #3: Talk About Work-in-Progress

A more experienced novelist gave me a hard time once for talking too much about the story I was working on. To be fair, I'd dumped ten minutes of exposition on him -- too much by anyone's standards. "You should never talk about your work-in-progress," he said. "Put that energy into writing, not talking."

Some writers leak details of their ongoing work for publicity reasons. That's a different matter. The concern this writer had was that, by talking, I was satisfying my urge to tell the story. The chatter served as a release valve, bleeding off the pressure until I could safely return to procrastiation.

Since then I've published five books and spent a lot of time with aspiring writers. I see them doing the same thing I used to do, and I give the same advice. Don't talk about what you're working on; work on it. Then you won't have to talk about the story because the story will do its own telling.

September 13, 2012

Things You Must Not Do, #2: Disrespect Your Reader

In her essay "Imagination and Community," Marilynne Robinson laments the fact that so many writing students come to her classroom with a cynical view of readers:

"A pretty large percentage of these fine young spirits come to me convinced that if their writing is not sensationalistic enough, it will never be published, or if it is published, it will never be read. They come to me persuaded that American readers will not tolerate ideas in their fiction .... They are good, generous souls working within limits they feel are imposed on them by a public that could not possibly have an interest in writing that ignored these limits -- a public they cannot respect."

While I doubt that my creative writing professors in grad school considered me a fine young spirit or a good, generous soul, they shared enough of Robinson's sensibility never to instill or reinforce a disrespect for readers. Indeed, they helped train me to be a reader -- the kind on whom (to borrow from Henry James) nothing is lost. My indoctrination in cynicism came later, when I came in direct contact with publishing professionals.

"You don't understand the Reader," they would tell me. "She can't follow these complicated sentences. She doesn't know these fancy words." She -- it was always a she -- does read, technically, but her reading habit was nothing like the lofty practice I had come to revere. It sounded more like watching television. Her books needed to be predictable, unchallenging, and simply written. "She's not like Us," they would say, not one of the cognoscenti. She was more like a mark, the dupe we were unloading our product on. For they were speaking, of course, about Consumers, not Readers.

"Nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public," H. L. Mencken observed. And all the cynics in publishing said, "Amen."

So much of the how-to culture surrounding writing makes these unflattering assumptions about the reader. Years ago, I worked with a marketing professional who always referred to the hypothetical customer as Joe Six-Pack. (The surname was a reference to his choice of beverage, not his abs.) A similar way of thinking informs a lot of writing advice. Follow the formula. Don't make the reader stretch. Use bold colors and bright lights, because the "reader" can change the channel any moment.

Paradoxically, the same people who spread this depressing orthodoxy also lament the deluge of formulaic crap that's submitted to them in response. Originality and depth still win, even if they are undreamt of in the cynic's philosophy. Robinson again:

"A writer controlled by what 'has' to figure in a book is actually accepting a perverse, unofficial censorship, and this tells against the writerly soul at least as surely as it would if the requirements being met were praise to some ideology or regime. And the irony of it all is that it is unnecessary and in many cases detrimental because it militates against originality."

Here's the reassuring thing. For all the cynics out there, publishing is stlll a business for idealists. Refuse the perverse, unofficial censorship and you find kindred spirits, people who are equally tired of treating readers as if they needed everything handed to them on a plate, pre-digested in simple, Anglo-Saxon words. My advice? Don't write for the market; write for the reader.

The how-to culture may warn you not to pay the reader too much respect. It's wrong. Disrespecting your reader is one of the Things You Must Not Do.