J. Mark Bertrand's Blog, page 3

May 21, 2012

Listen to Roland March!

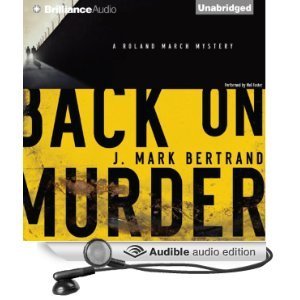

Time for an update. I mentioned in October that the first two Roland March novels were being made into audiobooks. Brilliance Audio is the company producing the books, with award-winning narrator Mel Foster reading. They are available as CDs, MP3 CDs, and downloads from all the usual sources -- Amazon, B&N, Audible.com, and so on.

The audio version of Back on Murder is available now. They're in production with Pattern of Wounds now. I'm keeping my fingers crossed that Nothing to Hide will make it to audio, too. In the meantime, if you're the type who prefers to listen to fiction, enjoy!

May 18, 2012

The Title from Hell

Above: the finished mauscript, circa 2011.

Above: the finished mauscript, circa 2011.

From the day a manuscript is turned in to the book's publication a year or more later, book titles have a funny way of changing. Both of the novels with my name on the cover that released in 2010 got fresh titles before publication. Beguiled, co-written with my friend Deeanne Gist, was called The Deceitful Welcome when we handed the manuscript over. I remember sitting across the conference room table from our editor as he politely said, "Umm ... no."

My first Roland March novel was called The Suicide Cop originally. After a grueling brainstorming process (during which my editor Dave Long and my line editor Luke Hinrichs helped me come up with dozens of possibilities only to have them shot down one after another), we finally settled on a workaround. The book was divided in three sections, the first of which was titled “Back on Murder.” We swapped the section and book titles, titling the novel Back on Murder and the first section “The Suicide Cop.”

I wrote the second book with the title Pattern of Wounds already in mind, and that’s the way it stayed ... after another lengthy brainstorming process. Score one for me!

My luck didn't hold. The working title for the third book was The Devil of Matamoros. I like that, but my editors worried that it didn’t peg the story quite right. (Not to mention the implications for South-of-the-border tourism.) Plus, now that the first two March novels had three word titles, I’d established a pattern -- and hadn't I already used an 'of' in Book 2?

The notepad came out, a list of alternatives developed. My favorite: Ain’t No Grave, from the Johnny Cash song. But have you ever tried to convince English majors that “ain’t” is proper English? It ain’t easy, so in the end the book became Nothing to Hide.

Whatever you call it, this is my most ambitious story so far. It releases in July, but you can read the opening here. Nothing to Hide, like all of the March novels, is available to order online, too.

May 17, 2012

Reading Balzac: Part Mystery, Part Tragedy

There's a soft spot in my literary heart for Honoré de Balzac. For one thing, he added that de to his name so he could sound more aristocratic (and got away with it). For another, he was a fiend when it came to his coffee, a sentiment I can get behind whole-heartedly. But the greatest thing about Balzac was the crazy scope of his writing project. All his novels, taken collectively, constitute La Comédie humaine, the mother of all interlinking stories, a social document in fiction which (unlike so many social documents) is actually enjoyable to read.

I have Balzac on the brain for two reasons. First, with the publication of my third Roland March novel looming, I find myself contemplating the ways in which the three books are really one long project. Not three novels each in three parts, but one novel in nine parts ... discreet episodes in a single story world.

Not that I'm comparing myself to Mr. B. The beauty of his accomplishment is that the main character in one novel becomes a minor character in the next, crossing both time and genre. The closest parallel today might be the miniseries, only you'd have to imagine a really meandering one with the patience to follow a background character through the side exit into the world in which he's a protagonist.

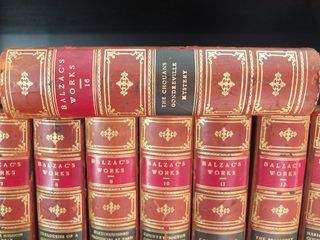

My second reason for mentioning Balzac is that I'm reading him again. This time I'm diving into The Gondreville Mystery, collected in a little tome entitled The Mysteries of Honore de Balzac, the tenth volume in a series called The Classics of Mystery published by Jupiter Press. This has been my midnight reading for several days now, and I'm enjoying it immensely.

The truly sad part of the story is that I have a much older, nicer copy of the book, sharing the same cover with The Chouans (above). Only I can't read it. When I rescued this complete set of Balzac from a Palo Alto bookseller four or five years ago, I thought my days of Balzac deprivation were over. As the intro to the Classics of Mystery volume notes, finding the great man in English translation isn't easy. I've tried him in French, but my grasp of la langue française isn't up to the task.

Unfortunately, these beautiful books suffer from a terrible case of leather rot (I think the conservators call this "red rot," because when you touch them, your hands come away red). I didn't realize it until too late. Frankly, I would have bought them anyway. In some far off time, I imagine having them restored or rebound. Until then, I mainly just gaze at them, dreaming of what might have been.

May 10, 2012

Spies, Drug Lords, Nutjobs, and Dante: Read the Opening of Nothing to Hide

If you're reading this, do me a favor: check out the first two chapters of Nothing to Hide. It's the third of my Roland March novels, and the opening chapters are now available on Scribd (which you can scroll through below). Read 'em and feel free to share them, too.

This is my most ambitious novel to date: there are spies, drug lords, Dante, conspiracy nuts -- wait, did that say Dante? Yes, it did -- and it all gets started with some decapitation and degloving, as you'll discover:

May 2, 2012

Dayne Sherman Makes the "Hard-Boiled Gazetteer to Country Noir"

Dayne Sherman may sound like a character on Treme, but he's a real-life novelist and librarian turned political gadfly in my home state of Louisiana. His first novel, Welcome to the Fallen Paradise, was named by Booklist as a Best Crime Novel Debut of the Year, and earned an even rarer honor: an Amazon review by yours truly. Now Booklist has honored Dayne again by including his book in the May issue's "Hard-Boiled Gazetteer to Country Noir." Maybe it's time for a re-read. (And if you haven't read Fallen Paradise yet, the e-book is just a buck, so why not?)

In the meantime, here's my take on the book circa 2006:

They call Louisiana the "sportsman's paradise," but in this case paradise is fallen. The grave-digging opener put me in mind of Wise Blood, and chapter after chapter Sherman delivered on that promise with plenty of corruption and ol' time religion. The novel rings with authenticity. Baxter Parish is a place where the fringes are mainstream. As wild as Moxley gets, and as extreme as the Tadlock response can be, I never once doubted the truth of it. Jesse Tadlock returns home with dreams of the garden, only to find a serpent bent on devouring him. The story may be simple, as an earlier review noted, but the emotions underneath are complex and stirring.

I stand by every word. The book also includes perhaps the best revivalist preacher scene I've ever read. That's saying something. While I've never had the pleasure of meeting Dayne in person, we've kept up over the years and he was kind enough to send me a signed Tim Gautreaux novel, which I'm reading now.

April 30, 2012

"Faux Fancy" Writing

A long time ago while visiting Germany, I discovered a paperback copy of Paul Fussell's book Class: A Guide Through the American Class System and stayed up all night reading it, cackling with delight the whole time. Some of his terms entered my lexicon and never left -- for example, "prole gap," to describe the distance between an ill-fitting suit jacket's collar and the back of the wearer's neck. While the book is tongue-in-check enough to be dismissed as entertainment, Fussell puts his finger on quite a few real phenomena, including the way middle class aspiration to status can result in absurd behavior ... and speech.

One of the things I noticed in the early days of the Internet was how, when engaged in virtual squabbles, a certain kind of person tends to lapse into quasi-Victorian rhetoric. "You, Sir, are no Gentleman!" The assumption being that this is how the better sort of people talk. This rhetorical style outs the aspirations of the people who engage in it. I think of it as "faux fancy" talk. People do it thinking they'll be perceived as more educated, more suave, more intelligent than they are. Sadly, the effect is rather different.

The same thing applies to some aspiring writers. They know "good" writing is supposed to be beautiful in some way, and they aspire to be good writers. So they fancy up the prose. No word is too polysyllabic or archaic for use, and the actual meaning of words fades to insignificance. The main thing is that they sound fancy. You could write, "Her face flushed," but why do that when you can wax eloquent like so: "A cherry red flush burst forth upon her formerly lily-white cheeks"?

Like faux fancy talk, faux fancy writing stands out because it's a poor imitation of the thing to which it aspires. Often, it is an attempt to write according to a set of perceived "rules" which the writer does not understand.

"Don't use passive verbs," some well-meaning instructor will recite. And the student, not understanding that there are instances in which passive verbs are not only acceptable but preferred, not realizing that the rule has more to do with overuse, will contort her sentences to avoid ever having to write was. (Ironically, the same teacher who wants to cross out all the being verbs might know enough to tell the same student never to embellish a dialogue tag. Your characters should never just be, the resulting scheme suggests, but they should never do more than say.)

The cure for faux fancy writing is first-hand knowledge of good writing. When the student realizes through reading that the great novelists the teacher venerates don't follow the teacher's rules for greatness, she can decide which example to follow. Unfortunately, aspiring writers are not always diligent readers. It shows when you try to read what they write.

April 17, 2012

Another Reason to Say Merci to France

It's happened again. Turns out the French introduced me to another noir classic without my knowledge. I've already written about the first time, when Francois Truffaut's film Confidentially Yours (which I've always liked) turned out to be based on a novel by noir great Charles Williams, The Long Saturday Night. Now, thanks to the new Library of America volume of David Goodis novels, I have belatedly discovered that the half-remembered Gerard Depardieu movie Moon in the Gutter, which I muddled through in college, desperately wanting to like it, is based on a Goodis novel of the same name.

First things first: thank you, France. We gave you back the key to the Bastille and called it quits. But you keep giving and giving. A friend of mine once wrote a novel that couldn't find a publisher here in the United States, but it was published in France. My response: "That is my dream." They don't call me Bertrand for nothing.

Franophilia aside, as I creep through the chapters of Goodis' novel late at night (which is the best time for reading noir), I find myself wondering, "Where have I been all my life? Was I not paying attention?" Suppose everything I've ever liked turns out to be based on a book? (Fine idea.) Suppose they're all books by famous authors I've somehow managed not to read? (Embarassing notion.) And I call myself a writer.

There's more about the Goodis volume in the Wall Street Journal, including some hard-boiled recommendations I've added to my to-read list.

April 16, 2012

Pattern of Wounds Nominated for Best Suspense

In a live ceremony this morning, the finalists for this year's Christy Awards were announced. Pattern of Wounds made the cut in the suspense category. Winners will be announced in July, and needless to say, competition is fierce. The other finalists are last year's winner Steven James, whose novel The Queen is racking up an impressive (and well-deserved) list of nominations, and Brandilyn Collins, who has been an encourager to many writers, myself included, and is long overdue for the recognition. "It's an honor just to be nominated" may sound like boilerplate, but in this case it also happens to be true.

The fact that I was a Christy judge myself in years past makes this particularly meaningful. I did it twice, and if my own experience is anything to go by, the judges will have read a staggering number of entries to arrive at this final selection. My hat is off to them. It's a lot of work!

February 6, 2012

The Policeman's Tortured Psyche

Norman Mailer, in a letter to William F. Buckley, Jr. quoted in The New Yorker, wrote this:

"I'm not the cop-hater I'm reputed to be, and in fact police fascinate me. But this is because I think their natures are very complex, not simple at all, and what I would object to in your speech if we were debating is that you made a one-for-one correspondence between the need to maintain law and order and the nature of the men who would maintain it. The policeman has I think an extraordinarily tortured psyche. He is perhaps more tortured than the criminal...."

February 1, 2012

Advice for Aspiring Novelists

Once upon a time, I dispensed lots of advice to fellow writers. I still do, one on one. But I stopped blogging about the writing craft when it became clear that the people who are interested in that sort of thing are other writers, not readers. The question comes up often, though, so I'm going to take a crack at summarizing all my best advice. Here goes:

1. First, read good novels

You don't learn to speak a language fluently in the classroom. While you can pick up the rules and rudiments there, to become truly proficient, you have to listen to people who speak the language well. The same is true when it comes to writing fiction. The single best thing you can do (and the single most enjoyable) is to read good novels.

Reading bad novels will teach you plenty, too, but it won't inspire you to excell. When you read a bad novel, you end up thinking, "I could do that." You begin to write with the idea, not of doing your best, but of improving on the crap that passes too often for fiction. This is like watching a bunch of awkward kids at Little League practice and deciding to go for the Majors.

So what's a good novel? It's the one you read and wonder afterward, "How did he do that?" Pose that question and stick with it until you come up with an answer. That'll teach you better than anything how to write a novel.

2. If you must read a how-to book, make it Stephen Koch's The Modern Library Writer's Workshop

I'm not saying it's the only, or even the best how-to book out there, just that it's the best summary of the essentials, and includes an annotated bibliography in back that will guide you through the rest. I spent years in an excellent MFA program, and I don't think I learned anything of value that isn't covered by Koch to one extent or another. Think of this book as orientation.

3. Read "Planning a Novel": Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

The thing that prevents most novels from being written isn't poor writing, it's poor planning. Back in 2007, I wrote a series of posts called "Planning a Novel" outlining my own method. Think of the planning process as the time you spend (a) learning your story and (b) figuring out how to tell it. A lot of the work you do during this period won't end up in the finished manuscript. That doesn't mean it's wasted. The goal of planning isn't to map everything out in advance; it's to know your material so well that you can take it in whatever direction the story wants to go.

4. If you want more of my advice, read through Crime Genre and Write About Now

Here at Crime Genre, I occasionally break my own rule and write about craft. Before this, I wrote almost entirely about craft at a blog called Write About Now, which went dormant in 2010. (Prior to that, I wrote a dedicated blog for writers called Notes on Craft, which isn't online anymore. Not to worry: some of the best material was reposted at Write About Now.)

5. One last thing: Don't put too much stock in the "rules"

Grammar is one thing, craft is another. Now that there's an industry that exists to educate (and profit from) aspiring novelists, an unparalleled volume of how-to guides are being written, most of them based not on fresh experience but on a regurgitation of earlier how-to guides. Often, these sources will inform you about the things you must do -- or not do -- in order to sell your work.

You won't sell your novel by following a set of rules any more than you'll fail to sell it by breaking them. If only it were that simple. The fact is, many of the rules are either helpful observations that have been misunderstood and misapplied over time (like "show, don't tell"), or particulars drawn from one writer's success then universalized (such as the notion that if you write in the style of James Patterson you will sell a similar number of books). Try to tune this stuff out.