J. Mark Bertrand's Blog, page 5

September 28, 2011

"The devil has been the unwilling instrument of grace..."

More from Flannery O'Connor. This is from the tail end of "On Her Own Work" in Mystery and Manners:

From my own experience in trying to make stories 'work,' I have discovered that what is needed is an action that is totally unexpected, yet totally believable, and I have found that, for me, this is always an action which indicates that grace has been offered. And frequently it is an action in which the devil has been the unwilling instrument of grace.

September 27, 2011

"Nothing produces silence like experience..."

Apropos of this, some thoughts from Flannery O'Connor:

"I have very little to say about short story writing. It's one thing to write short stories and another thing to talk about writing them, and I hope you realise that your asking me to talk about short story writing is like asking a fish to lecture on swimming. The more stories I write, the more mysterious I find the process and the less I find myself capable of analyzing it. Before I started writing stories, I suppose I could have given you a pretty good lecture on the subject, but nothing produces silence like experience, and at this point I have very little to say about how stories are written."

September 20, 2011

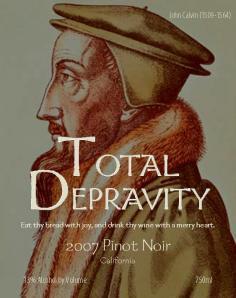

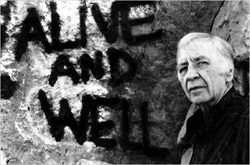

Theology and Noir

For more on the image above, click here.

Writers disagree on whether it's a good idea to read reviews of your own work. I still do, mainly to gauge whether or not my deeper effects are coming off. By deeper effects, I meant the subtextual stuff, the engineering underneath the plot. Some readers never notice this kind of thing -- and a few of them do but don't like it, suspecting authors with subtle intentions of preteniousness.

Mea culpa.

I'm a writer with theological interests, so my ears perk up when mention is made of that sort of thing. To me, the tropes of crime fiction lend themselves to an exploration of big questions about meaning and evil. But some religious readers don't like the realism of such fiction -- the most feedback you get from them is based on whether or not they perceived the book as a "clean" read -- while some crime readers don't want philosophical or theological ruminations getting in the way of the body count. Since I like what I'm doing in the March novels, it's good to get confirmation that the crime and the questioning work together.

Kevin Tipple's review of Pattern of Wounds suggests as much, even going so far as to say that the theology discussion "heightens the continuing sense of noir":

Furthermore, the theology discussion regarding good/evil and the role of God that comes up several times in the novel actually adds to the complexity of the novel and provides character depth. It also heightens the continuing sense of noir that was present in the first book and is also present here.

When you're writing about themes like sin and evil, it's important not to stack the deck. Bad arguments shouldn't win over good ones just because they support the author's preferred stance and he wants to deliver the "right" answer. Everybody has a case, as one of my professors used to say, and as the author you have to let them make it. One of the weaknesses of so much religious fiction is that the cleric or clerical stand-in always speaks ex-cathedra. You know from the beginning his is the argument that will carry the day. In the real world, it's just not so. I try to write about these issues the way they develop in reality, as opposed to following the conventions of fiction. Lars Walker writes:

Bertrand is doing almost exactly the thing I've tried to do (with far less success) in my own fantasy novels—to portray the real world through eyes of faith, giving both believers and unbelievers a fair chance to make their cases ... [He] is in the process of producing a detective series that does all I could ask of Christian literature. Good writing, strong characters, a compelling (though complicated) plot, realism, and no preaching.

All I can say to that is: Amen.

September 19, 2011

Clash of the Titans: Gardner vs. Percy

After mentioning Walker Percy and John Gardner back to back, I'd be remiss in not pointing out that Gardner's review of Percy's Lancelot, a book I happen to like a lot (it was my first Percy read), ended on a sour note:

Fiction, at its best, is a means of discovery, a philosophical method. By that standard, Walker Percy is not a very good novelist; in fact Lancelot, for all its dramatic and philosophical intensity, is bad art, and what's worse, typical bad art. Like Tom Stoppard's plays, it fools around with philosophy, only in this case not for laughs but for fashionable groans. Art, it seems to me, should be a little less pompous, a lot more serious. It should stop sniveling and go for answers or else shut up.

One thing I've never thought about Walker Percy is that he didn't "go for answers." In fact, Gardner concedes as much earlier in the review. His problem was, he didn't like Percy's answer. "But surely everyone must know by now," he wrote, "that Kierkegaard's answer is stupid and dangerous. Why Abraham's leap of faith and not Hitler's? Lancelot himself makes that point."

What Garder perhaps did not appreciate, seeing the novel as a philosophical method in tandem with philosophy proper (and therefore bound to its sense of what "everyone must know by now," is that a novelist might arrive at answers philosophy has already passed over. Percy shakes up the reader's assumptions enough that the seemingly outmoded answer takes on new relevance. In Flannery O'Connor's terms, he's shouting so that the deaf can hear.

And part of his technique, as Gardner notes, is to have his protagonist Lancelot raise the supposedly fatal objection himself, only to let the reader overrule him.

September 15, 2011

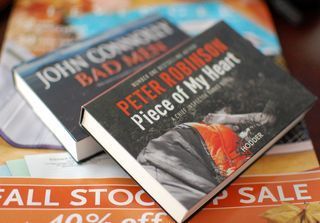

More Flipbacks

The mailman brought treats from across the sea today, a couple of new flipbacks to sate my newfound passion for the quirky little format. Thanks to the novelty factor, I'll soon be reading an author I really like but haven't kept up with for a couple of years (Peter Robinson) and another I haven't read yet but probably should have (John Connolly). I only wish the flipbacks were available Stateside so they didn't have to travel quite so far.

September 13, 2011

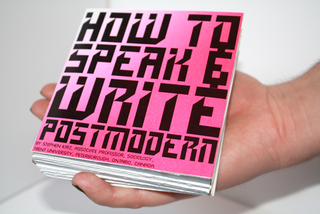

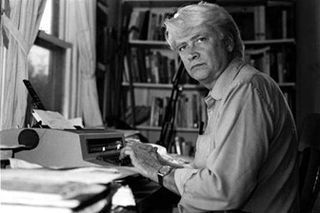

Deconstructing Postmodern Mysteries

For more on the above, click here.

For more on the above, click here.

Ted Gioia has devoted a site to what he calls the "postmodern mystery," complete with a list of essential works in the sub-genre, which has led Linda Richards to wonder whether the criteria for 'postmodern' -- books which, among other things, both celebrate and undermine the precepts of crime fiction -- isn't just another synonym for good writing. Personally, I think there's something to the concept, but the essentials list baffles me a bit.

From Martin Amis he includes London Fields but not Night Train. From Fredrich Dürrenmatt he includes The Pledge but none of the Inspector Barlach books, in which the games the author is playing are more apparent. There's some Umberto Eco but no Arturo Perez-Reverte. And I would have thought Graham Swift's The Light of Day rated inclusion, not to mention Julia Kristeva's Murder in Byzantium (because, well, she's Julia Kristeva, and she wrote a mystery). And the net is cast pretty wide, historically speaking, to include Robbe-Grillet and Flann O'Brien (plausible enough) along with Patricia Highsmith and Agatha Christie (not so much).

The result is a list that mixes in examples of more pure noir metafiction, such as Paul Auster, with other books which play, perhaps less self-consciously, with the conventions of the genre. Even so, it's a good list. Whether "postmodern mystery" is the right term or not, I like this sort of book, and thanks to Gioia I can add some titles to my to-be-read stack. While I think there's something more than simply genre bending or mash-up going on here, unlike Gioia I haven't put in the effort to try and quantify it. So my hat's off to him.

September 12, 2011

Sidebar: "Published Elsewhere"

I've added a column to the sidebar listing reviews and commentary of mine that's been published elsewhere over the past couple of years. Many of these have been noted on the blog, but I figured it would be helpful to have a round-up handy. The odds are, I've forgotten to include a few. I will add them as chance and memory dictate, as well as updating the list when new pieces come out.

September 11, 2011

The Savage Nights of Jim Thompson

Something surprising happened when my new bookshelves inpired me to re-organize my hopelessly scattered library. As I picked out novels here and there, consolidating each author's work on a shelf of its own, I started doing a quantitative ranking of favorites. If I had five of one writer's books and only one of a second guy's, it stood to reason I liked the first author five times better.

Okay, so maybe that's not the best way to judge. Some authors crank the books out and others don't. I only have two of Homer's books, but that's all he wrote. Briefly I toyed with the idea of calculating percentages -- i.e., if I had 100% of an author's books, even if there were only two of them, then clearly I preferred him to somebody I'd only gotten 50% of the way through (even if that 50% amounted to a dozen books). There were two problems here: (1) mathematics and taste don't go well together, and (2) I learned math in the Louisiana public school system, so I'm all right at counting but not so good at calculating percentages.

The point is, I had a lot more Jim Thompson than I realized -- fourteen books, not counting five or six duplicates -- and of them I've read (and in some cases re-read) The Killer Inside Me, Savage Night, After Dark, My Sweet, The Getaway, A Swell-Looking Babe, The Grifters, and Pop. 1280. And I'm about halfway through Wild Town.

While I know his work, I knew relatively little about his Hollywood career, an omission rectified by a two-part piece by Richard Santos published at Criminal Element: "The Nothing Man: Jim Thompson in Hollywood." Part One is the history lesson, including the troubled relationship between Thompson and Stanley Kubrick, while Part Two looks at the various film adaptations of Thompson's novels, including my favorite, Coup de Torchon, based on Pop. 1280 with Philippe Noiret in the lead. The survey leads Santos to conclude that perhaps Thompson's books (like the man himself) are unadaptable for Hollywood:

Jim Thompson wrote some of the most bizarre, disturbing and just plain good literature of the twentieth century. He not only wrote characters who committed unimaginable crimes, he also wrote novels that stretched the boundaries of the crime genre and the form of the novel itself. But maybe on some level Thompson's creations are un-adaptable. Maybe his vision of America is just too damn scary to put on the big screen without some sort of filter over the material.

It's strange to think, considering the reverence modern crime readers have for Jim Thompson, that he was booted off the film adaptation of The Getaway, replaced by another writer. The boot was on the foot of Steve McQueen, but even so, if that had happened in one of the books, say Savage Night, McQueen would have ended up with a stump at the ankle.

September 9, 2011

Truth As a Goal, Not a Point of Departure

In The Art of Fiction, which possesses that virtue, rare for books on writing, of actually being worth reading (though it is typically assigned to those who aren't ready to), John Gardner has this to say about telling the truth:

"Telling the truth in fiction can mean one of three things: saying that which is factually correct, a trivial kind of truth, though a kind central to works of verisimilitude; saying that which, by virtue of tone and coherence, does not feel like lying, a more important kind of truth; and discovering and affirming moral truth about human existence -- the highest truth of art. This highest kind of truth, we've said, is never something the artist takes as a given. It's not his point of departure but his goal. Though the artist has beliefs, like other people, he realizes that a salient characteristic of art is its radical openness to persuasion. Even those beliefs he's surest of, the artist puts under pressure to see if they will stand."

The emphasis is mine, because failure in fiction -- my own failures, at least -- always seem to flow from having forgotten this fact.

September 8, 2011

"Small disconnected facts, if you take note of them, have a way of becoming connected."

When they were both young, Walker Percy and Shelby Foote took a road trip to William Faulkner's house in Oxford, Mississippi, intending to introduce themselves to the great man. On the curb outside, Percy chickened out and stayed in the car. From there, he got to watch his bolder friend Foote sipping whiskey on the porch with Faulkner, and I'd give anything to know what he was thinking. Frankly, in that scenario, I would be in the car with Percy, too much in awe to make the approach.

Then again, I'd be too much in awe of Percy to sit with him in the car. I'd need some vantage point down the street where I could observe the scene twice removed. This is probably the best angle from which to view one's heroes anyway.

In The Thanatos Syndrome, Percy writes: "Small disconnected facts, if you take note of them, have a way of becoming connected." He has epidemiology in mind, though this could just as easily serve as a rationale for conspiracism (see Foucault's Pendulum). I take it, though, as a paraphrase of Henry James' dictum, "Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!" I don't imagine much was lost on Walker Percy, the quintessential observer, as he sat behind the wheel on Faulkner's curb.