J. Mark Bertrand's Blog, page 6

September 7, 2011

The Problem with Charles Williams

Part of the problem has to do with disambiguation. Whenever I recommend him, I have to explain which Charles Williams I mean. As I've mentioned before, there were two of them, and the more famous of the two these days is the other Charles Williams, the minor Inkling. Part of the problem, too, is the lurid cover art. There's a certain kitsch appeal thanks to the passage of time. Even so, you look at the cover and think you're entering the realm of guilty pleasure. Sure, there's pleasure, but no need to feel guilty about it. Charles Williams knew how to write.

The real problem with Charles Williams is that he's mostly out of print. That makes no sense to me at all.

Like Simenon, another of my obsessive favorites, Williams keeps telling more or less the same story. Some middle-aged loner with a seafaring bent gets into trouble alongside an exceptional woman. At some point, there will be a math problem to work out, usually having to do with navigation. I'm no good at math, but I find this stuff riveting. In fact, the trouble with the film adaptation of Dead Calm is that it cuts out all the math. That's a book about dead reckoning under extreme pressure. Put a nav computer onboard and you lose the spine of the story.

Not all of Williams' books take place on sea. Until recently, I've kept them sorted into two mental piles -- the land-based books and the nautical noir. That changed a couple of weeks ago when I started reading Man on a Leash, in which a grounded sailor confronts the bank-robbing cabal that murdered his father.

Above: It must have killed the designer

not to be able to put a swimsuited babe on the cover.

The reason I'd put Leash off is that I figured it wouldn't have the navigational problem to solve. Oh, but it does. To find the lair of the villains, the main character has to figure out where his father drove, with nothing but an odometer reading and the dust on the car to guide him. This might seem impossible to you or me, but a Charles Williams protagonist is used to pinpointing tiny sloops on the vast stretch of the Pacific. All he has to do in this case is get out a map and take every available route until he finds a location at mid-point that seems promising. All he has to do, in other words, is the math.

When I realized the problem was here on land just as it is in the sea novels, I remembered that this isn't the only case of geographical math in Williams' non-nautical books. In his noir classic The Hot Spot, the central caper relies on fitting a careful timeline to the well-traveled landscape. There are spatial/mathematical problems to be worked out in some of the others, too.

All this to say, Williams makes for compelling reading. If you're not convinced, check out Ed Lynskey's piece on Williams, weighing his greatness against his relative lack of renown. A lot of writers slip into obscurity deservedly. In some cases, though, it's a crying shame. As for me, I'm snatching his books up wherever I can find them.

September 6, 2011

Two Ways to Love a Genre

"It's like an episode of CSI, only much longer."

The first thing you need to know about this line is that it was written about my novel Back on Murder, which introduces my series protagonist Roland March. The second thing you need to know is that it was intended as a compliment. Not everyone would take it that way, which goes to show that while two people might love the same genre, they love it in very different ways.

Some people who love the crime genre love everything about it. Kill somebody and then launch an investigation, and they'll follow along with delight. Doesn't matter if the detective's a deadbeat alcoholic fighting crime in between bouts of depression or an eccentric English grandmother fitting in her sleuthing beween crosswords and crochet. Crime is crime, and they love it all.

Others love a narrow slice of the genre. They prove that love in part by hating all the rest. A lot of writers (though certainly not all) fall under this heading. The worst thing you can do is lump them in with the wrong kind of crime. My misgivings about CSI in particular and the pseudo-science of forensic fiction in general are on the record, so there's no use denying them. One of the reasons I incorporated Houston's real-life crime lab scandal into Back on Murder was to undercut the easy assurance CSI-style storytelling seems to impart. So comparing it to "an episode of CSI, only much longer," is like channeling Sartre's definition of hell.

But, hey, I write crime fiction. What was I expecting? "It's like Proust's In Search of Lost Time, only the gunfights are more realistic." I should probably be grateful. The people behind the various CSIs make a lot of money. If more people realized my books were like a never-ending episode of that show, my wife could finally have her kitchen redone.

September 5, 2011

"I Alone Understand What I Do": More Manchette

At the risk of boldly going where I've already gone before, let me quickly offer More Manchette. I missed J. P. Smith's review of Fatale, the latest Manchette re-issue from NYRB, and it's worth circling back for the insight it offers into Jean-Patrick Manchette the author.

On April 29th, 1977, Jean-Patrick Manchette wrote in his diary that his editors at Gallimard's famed Série Noire didn't like Fatale (which was then titled La Belle Dame Sans Merci, after Keats's poem of the same name), which prompted Manchette to request that it be published outside this legendary series of crime novels. He writes: "This negative response clearly shows what I should never forget: I alone (with Melissa [his wife, to whom Fatale is dedicated]) understand what I do."

As pretentious as it might sound, I imagine every writer has had to fall back on that thought at one point or another. I alone understand what I do. And sometimes even I don't have a clue.

Manchette was a Marxist who considered the noir novel an artefact of the counter-revolution. The gumshoe is a revolutionary operating after the failure of the revolution, unable to right any systemic wrongs and hence cynical, but still fighting against the corruption and hence moral.

...the roman noir is characterized by the absence or weakness of the class struggle and its replacement by individual action (which is, incidentally, hopeless). While the bastards and the exploiters in fact hold social and political power, the others – the exploited , the masses of people – are no longer the subject of history, and in any case only appear in the roman noir in minor roles, more or less socially marginalized – taxi drivers, racial minorities (blacks, chicanos), vagabonds, the unemployed, déclassé intellectuals, servile personnel (but also, in surprising numbers, in the figure of workers, always especially mistreated before or during the novel's action by the bosses, big shots and their strong-arm men).

Here the class struggle is not absent in the same way as in the mystery detective novel. It is simply that here the exploited have been defeated and are forced to suffer under the reign of evil. This reign is the field of the roman noir, a field in which and against which the actions of the hero are organized. When this hero is not himself a bastard fighting for his tiny portion of power and money (as is the case in the early novels of James Hadley Chase) when he (as is the case in Hammett and Chandler) knows what good and evil are, he is nothing but virtue in a world without virtue. He can right a few wrongs, but he will never right the general wrong of this world; he knows this, and this is the source of his bitterness.

That's a quote from "Five Remarks on How I Earn My Living," and there's more along these lines in the later "Toast to Dash." Despite the fact that my own take on noir has led me to pursue other lines, I find Manchette's reading quite plausible (especially in the case of Hammett).

According to Smith's review, Manchette decided that since he couldn't further the communist revolution, he decided to "soley entertain, to distract." Fatale does that, and a little more, though I agree that it feels slight in comparison to The Prone Gunman and Three to Kill.

September 3, 2011

Shining a Light on Character

One of the fun things about writing detective stories is getting to equip your characters. There's so much gear to research ... or at least, there would be if I didn't devote so much of life to "gear research" already. And the little details do not go unnoticed. You might think nothing when Roland March whips out his flashlight. But to some readers, it makes a difference.

March is a detective,which means he's in plain clothes and doesn't have a rig for carrying lots of equipment. When he wants to shine some light on the situation, he slips out his trusty Fenix. Compared to the big flashlights of old, these little things put out an incredible volume of light relative to their size. I have a couple of them myself, and I think they're better than the old Surefires they replaced, despite being a whole lot cheaper.

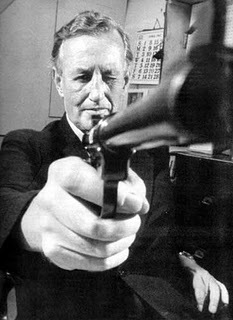

Ian Fleming (above) probably started the gadget trend in adventure fiction -- and he wasn't above getting some of the details wrong. After all, he gave James Bond a .32 caliber pistol on account of its stopping power. I'm not complaining, though. As any gear-obsessive will tell you, the choice of equipment reveals character. As a reader, I enjoy knowing what kind of equipment a hero chooses, and as an author I do my best to make those choices meaningful.

September 2, 2011

The Craftsman's Pleasure in His Tools

I write my books with a simple word processor rather than Scrivener, and I take notes on mere paper instead of using Penultimate. I guess you could call me a throwback. Although I have both pieces of software -- I've even tried to use them -- the fact is, I prefer more traditional tools. That's just the way my mind works.

Did I mention I also have a tool fetish?

Above: If you keep track of such things, the outside pens are both Pelikans,

the black ones are Mont Blancs, the yellow ones are a Bexley fountain pen

and a Visconti rollerball, and in the center is a Montegrappa.

Despite my computer literacy, I do a lot of my work with pen and ink and paper. Any pen or paper will do, but if I have a choice in the matter, I prefer the good stuff. Carpenters probably feel the same way about their hammers -- or do they use nail guns now? (As a crime novelist, I'm more accustomed to thinking of how nail guns can be misused. And hammers, for that matter.)

For years I preferred rollerballs because they shared the fountain pen aesthetic without squirting ink all over the place. Plus they wrote a much finer line, and I have small handwriting. Then I discovered that fountain pen nibs come in a variety of sizes. My first pen, the Pelikan up top, was purchased in West Germany in the late 1980s and came with a Broad nib, which forced me to write much larger than normal. As a result, many of the love letters I wrote to my future wife look like they were written by an elderly man. I insisted on cursive, despite having switched to block letters in junior high, so they're not only large print but also shaky.

Now I've got the fountain pen thing under control. My only problem is finding the ultimate pen. Like so many inadvertant collectors, I ended up with a lot of pens when in reality I only want one. But it has to be the right one, know what I mean? Fortuately I've narrowed the field down to two or three possibilities.

The niftiest pen in the world has to be the Sheaffer Oversize Balance from the 1930s. I've been on the lookout for one of these for quite some time:

Then again, there is something to be said for taking the custom pen plunge. I find some of Brian Edison's work extremely appealing:

I may write tough-minded modern crime fiction, but my tastes in writing instrument seem to be decidely cozy mystery, eh? One day, when I find the perfect pen, I fully intend to get rid of all the others. That's what I tell myself, anyway, as the pile continues to grow!

September 1, 2011

"The more identities a man has, the more they express the person they conceal."

There's a pivotal scene in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in which Smiley recounts to his accolyte Peter Guillam the story of his attempt in the mid-1950s to convince Soviet spymaster Karla to defect. During the interview, which took place in an Indian prison, the Russian never spoke a word, leaving Smiley to ramble on and on -- an inversion of the interview technique we see an older Smiley using throughout the book, keeping quiet to encourage the subject to talk. Young Smiley convinces himself he can read into Karla's expression, when in fact he is projecting his own sentiments onto the other man. The resulting failure, however, teaches Smiley a lesson.

"I even put it to Control: we should take the opposition's cover stories more seriously, I said. The more identities a man has, the more they express the person they conceal. The fifty-year-old who knocks five years off his age. The married man who calls himself a bachelor; the fatherless man who gives himself two children ... Or the interrogator who projects himself into the life of a man who does not speak. Few men can resist expressing their appetites when they are making a fantasy about themselves."

True enough. John le Carre has a knack for making the particulars of his fictional intelligence world feel like universal expressions of the human condition, and here he hits on something that resonates. The anonymity of the Internet gave everyone the opportunity to craft a cover story, and the fantasies we made about ourselves surely expressed our real appetitites, for better or worse. It's always telling to know what a person would change about himself, what would drive him to concealment or deception. These lies are in fact a form of unwitting self revelation.

What Smiley says is particularly true for authors. Our protagonists can serve as avatars, our plots as a vicarious means of wish fulfillment. When we invent stories, we make a fantasy about ourselves, and its difficult to resist expressing our appetites. Not to bag on Stieg Larsson, but one of the recurring themes in criticism of his work is how closely Mikael Blomkvist resembles his creator, and how ready the author's female creations are to shack up with him. If you're attuned to such things as a reader, you can't help but wince at the thought that the author hasn't covered his tracks well enough. If you're an author yourself, you wonder what secrets you've revealed about yourself as well. Under a similar magnifying glass, would you fare any better?

On the one hand, I agree that making simple biographical interpretations is facile. When people who know me try to connect the mannerisms of Roland March and his circle to me and mine, more often than not they're off the mark. On the other hand, I think Smiley is right. The choices we make when given the power to create an alternate identity are revealing indeed.

August 31, 2011

Advice for Writers

As of today, four of my books have been published and a fifth comes out next summer. Inevitably, I am asked for advice. Most advice on writing is pretty poor but that hasn't stopped a whole industry from cropping up to pass it along. I don't want to be part of that. Writers should make their money off of readers, not aspiring writers. And yet I'm an opinionated fellow prone to lecturing others. If you ask, it's hard for me to keep my mouth shut.

In the past, I've devoted a lot of energy to writing about writing. If you're keen with your Google, you can probably find some of that stuff. Through experience, I've whittled my writing advice down to two points.

First, read lots of novels.

Second, if that doesn't answer all your questions, read Stephen Koch's Modern Library Writer's Workshop. After that, read a bunch more novels. This won't solve all your problems, but it will save you having to ask other people for advice on how to write. Oh, and one more thing: Write.

August 28, 2011

A Pocket Book That Really Fits

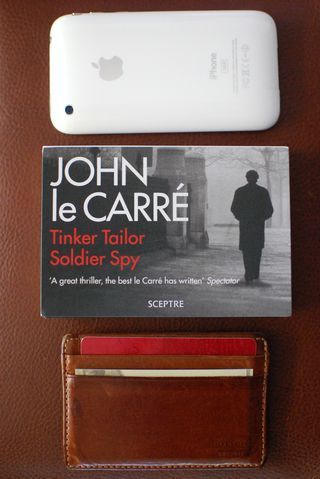

One of the blogs I try to keep up with is Everyday Carry, where people dump and photograph the (highly premeditated, tightly edited) contents of their pockets. If I were going to take a snapshot of my EDC these days, it would look something like this:

The "pocket-sized book" rarely lives up to its name. Mass market paperbacks, the small, thick volumes stuffed into the supermarket racks, are the closest thing, but these days they tend to be very cheaply produced ... and quite garishly ugly. And yet, I've been carrying John le Carre's Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy around in my pocket the past couple of days. Last night I forgot it was there and ended up carrying it along to the house of some friends. It fits in the pocket thanks to an innovative new design format. It's called a flipback.

I've written about the concept recently on my other blog. Recently I met the design team and the printer behind the project, 2Krogh and Jongbloed. They gave me a few flipback editions to whet my appetite. Thanks to Amazon UK, I now have more, which gives me an excuse -- as if any were needed -- to re-read my favorite Le Carre novel.

The flipback works like so: Instead of opening in the traditional way, with a page on the left and another on the right, it's oriented sideways. The text column runs down the length of two pages, effectively doubling the reading surface. This allows the book to be much smaller than a mass market paperback while boasting roughly the same column size. The use of super thin paper helps keep the whole thing quite compact. I'm about halfway through Tinker Tailor and yes, it does take some getting used to. After the first few minutes, the only trick is having to turn the pages upward instead of side to side.

While there aren't many flipback editions to choose from, what few there are offer a nice variety. Next for me will be Peter Robinson and John Connolly.

August 26, 2011

I Hate the Kindle Ads. Wanna Know Why?

I like the Kindle. I hate the Kindle ads:

I didn't always feel this way. When the Kindle was bagging on the iPad's glary screen, I chuckled along. You see, I don't have a Kindle device, but I use the Kindle app on my iPad and iPhone, and I absolutely hate the screen glare. (I hate it on my Mac, too, and long for the good ol' days when Macs came with outdoor-appropriate matte screens.) But now the Kindle is bagging on physical books, not to mention bookstores. You shouldn't kick a man when he's down.

Not to mention how selective the conversation in the commercial is! The guy with the Kindle thinks it looks like a printed book's page. I have to wonder what kind of books he's used to reading. The ones I prefer aren't set in bland and awkwardly spaced system fonts like Times Roman. My gripe with the Kindle -- indeed, with all e-books -- is that they don't at all look like printed books in one important way: design and typography.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not against e-books. The concept excites me. My books are all available as e-books for purchase. I read e-books and enjoy them. But I don't enjoy them as much as I would if they were capable of typographical precision. A beautifully designed book -- whether physical or digital -- will always be a pleasure to read. I'm just worried that despite a few exceptions, e-books aren't being designed very well.

The Kindle ad that will get me pumped will go something like this:

"Hey, I see you're reading a physical book -- but, wow, whoever designed that thing should be hit over the head with a copy of Bringhurst's ELEMENTS OF TYPOGRAPHICAL STYLE!"

"Yeah, I know, it really sucks. But what can I do?"

"Well, with my Kindle, I just push a button, and the designer's crappy work is stripped out and re-formatted according to classic typographical principles."

"Cool. Hand me that beautiful piece of technology."

Until then, Kindle, try to tone down the triumphalism!

August 25, 2011

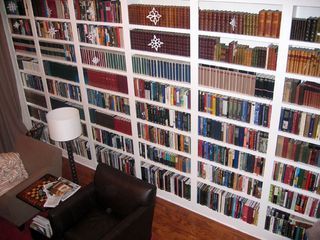

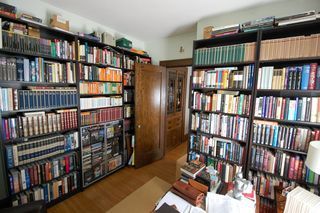

The Bookshelf Saga

My wife says I'm a hoarder, but the term I use is bibliophile. Like many a reader before me, I can't help but accumulate books. Hey, I'm a writer, what can I say? It's part of my profession. We have thousands of them, perhaps enough to open our own bookstore -- the only problem being, I can't bring myself to part with any of them. Realistically, I know I'll never read the vast majority of them; and of those I've read, only a small number will ever be consulted again, let alone re-read. Yet I can't break myself of the conviction that I need them all. And not only that, I also need them to be readily available at a moment's notice. Which means that along with all the books have come many, many bookcases.

About a decade ago, when we still lived in humid Houston, I finally broke down and had a carpenter make built-in cases along one of the towering walls of our suburban home. He'd never done this before -- demand, apparently, isn't very high these days -- and lived in constant fear that the shelves would collapse under the weight of books. Therefore he over-engineered them in a big way, resulting in a bookcase gorillas could climb without causing so much as a creak. I was in heaven.

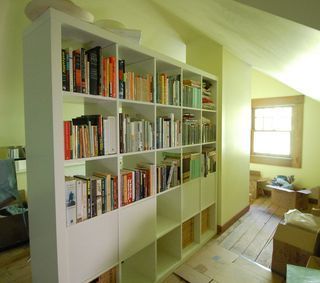

But we left Houston and the built-ins behind. Despite my bad experiences with particle-board shelves, I stocked up on as many IKEA bookshelves as I could fit in a truck, then spent about a week putting them all together. They get the job done, but that's about all I can say for them.

In theory, the IKEA shelves are easy to disassemble and move around. And they're better than a lot of other cheap bookcases I've used. Still, there's something about their impermanence that makes it hard for me to keep my books organized. After our most recent move, they've end up scattered all over the house, tucked next to one another in no order but that of acquisition, like so many sedimentary layers waiting to be explored by a future archeologist of taste.

One solution to a problem like mine is editing. If you love books, though, you know how hard it can be to part with them -- even the ones you don't particularly care for. Intellectually, I have made my peace with the idea of thinning the herd. The second solution might help in that regard: barrister bookcases.

Barrister bookcases aren't exactly new. Think of them as the original modular shelving, only they were built to last and not fall apart. A barrister bookcase is basically a stack of self-contained shelves. To move them, you just unstack the units. Traditionally they're made of solid wood -- in fact, you can still buy high quality wood units from places like Levenger -- but the ones that get me excited are mid-century Globe Wernicke shelves made of metal. We just bought a few:

I'm hoping to add more in the future. They're gunmetal gray with glass doors and a manufacture date of April 1963. Considering their age, they're in great shape. Since I only have eight shelves to fill, the question is which books to put in them. Maybe having to make that editorial choice will spur a larger purge of the collection? That's what I tell myself, anyway. If nothing else, it might help me find the books I use most often a little more easily.