Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 35

April 10, 2021

Revisiting Bletchley Park through Kate Quinn's The Rose Code

In July 2019, my husband and I took a week's trip to London, back when vacations were a thing. On a friend's suggestion, we planned a visit to Bletchley Park in Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, taking the London Northwestern Railway from Euston Station. After arriving at the Bletchley stop, we walked down a long flight of stairs, exited the station, crossed the street, and the entrance to Bletchley Park was a short walk away.

In July 2019, my husband and I took a week's trip to London, back when vacations were a thing. On a friend's suggestion, we planned a visit to Bletchley Park in Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, taking the London Northwestern Railway from Euston Station. After arriving at the Bletchley stop, we walked down a long flight of stairs, exited the station, crossed the street, and the entrance to Bletchley Park was a short walk away.From watching The Bletchley Circle, I knew what had taken place during WWII at Bletchley, the center of codebreaking activities, and the heroic acts of the thousands of very smart people employed there during the war, most of them women. Their work was key to the Allied victory and reportedly shortened the length of the war by two years.

Bletchley Park mansion from a distance, and small lake, which

Bletchley Park mansion from a distance, and small lake, which appears in the story early on. Photo taken by me (7-15-19)

So of course when I first heard about Kate Quinn's The Rose Code, I knew I'd have to read it. When I had a break between review assignments this past week, I dived right in.

The Rose Code is a smart, character-driven historical thriller about three women who become unlikely friends and allies while working at Bletchley during the war, and the terrible betrayals that destroyed their strong bond.

Work tables inside one of the huts

Work tables inside one of the hutsMab Churt is a tall, self-sufficient East Ender worried about her mother and younger sister in London. Canadian-born Osla Kendall, a character based on Osla Benning, an early girlfriend of Prince Philip, runs in elite social circles and has led a relatively sheltered life. She has a talent for languages and wants the world to know she's more than a "silly deb." Lastly, shy Beth Finch, a whiz with puzzles, escapes her overbearing mother's insults and abuse when she discovers, to her astonishment, that she fits in with the other codebreakers at Bletchley. Their work is so secret that each worker only knows their own task.

Alternating chapters set in 1947, in the days leading up to the royal wedding, follow the trio as they're forced to reunite, with one of them held against her will in a sanitarium, in order to unmask a spy within their earlier ranks.

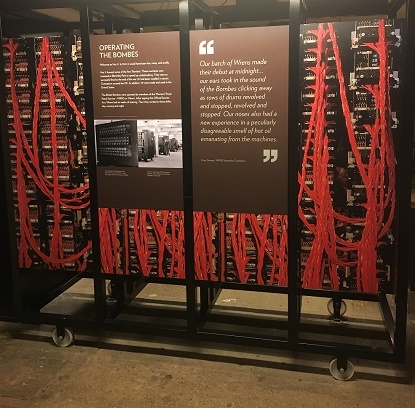

Exhibit on operating the Bombes

Exhibit on operating the BombesThe story takes you right inside the huts at Bletchley where all the codebreaking takes place and also inside the characters' heads as they try to crack the codes used by the Germans. You feel their exhaustion as they push themselves to their physical and mental limits, and rejoice when they succeed in finding the right pattern. Mab becomes one of the women operating the decryption machine known as the Bombe (image above). When I visited in summer, the huts were cool, but all of the rooms are fairly small, with narrow corridors connecting them. One could easily imagine how hot and cramped they were, with the women constantly in motion as they put the heavy drums in their slots and adjusted the wires to keep the Bombe running.

The setup at Bletchley, in July 2019, made it appear as if the huts' occupants had just stepped away from their desks for lunch.

The setup at Bletchley, in July 2019, made it appear as if the huts' occupants had just stepped away from their desks for lunch.The story makes for compulsive reading as it interweaves the women's friendships with several poignant love stories and the intense race-against-time atmosphere of the earlier and later timelines.

The office inside the Bletchley Park mansion

The office inside the Bletchley Park mansionIt does feel rather startling to have just finished this novel as Prince Philip's death was announced, as he's a major character. In The Rose Code he's the dashing and tanned Prince Philip of Greece, Royal Navy officer and distant relative of the British royals. He and his girlfriend, Osla, set up by a mutual friend, share the feeling of having no real home. His depiction feels realistic and respectful.

I'd love to see the novel as a film, and with the recent announcement of a TV adaptation, hopefully that will happen in the near future. Both a visit to Bletchley and the novel itself are definitely recommended. (Thanks to the publisher, William Morrow, for approving an e-copy via Edelweiss.)

April 7, 2021

While Paris Slept by Ruth Druart, a novel of family and courage in Nazi-occupied France

To what lengths would you go to ensure your child’s survival? What would you sacrifice in yourself to preserve their well-being? With her accomplished first novel, Druart penetrates to the heart of these emotional questions, exploring them in multiple ways through the interlinked stories of two couples.

To what lengths would you go to ensure your child’s survival? What would you sacrifice in yourself to preserve their well-being? With her accomplished first novel, Druart penetrates to the heart of these emotional questions, exploring them in multiple ways through the interlinked stories of two couples. In 1953 Santa Cruz, California, Jean-Luc and Charlotte Beauchamps are the proud parents of a son, Sam, who loves burgers and chocolate-chip cookies as much as any American kid. They’ve strived to adapt to their new country, speaking only English, and never revisiting the trauma they fled in Paris nine years earlier. The tone is ominous as a car pulls up to their house. Inspectors take Jean-Luc in for questioning, and his carefully built life begins unraveling.

Back in March 1944, Jean-Luc maintains tracks for the French national railway, now under German control. He’s nervous after being transferred to the Drancy station, as rumors float about forced deportations of Jews. He never sees any trains, but evidence left on the platform – a stuffed toy, a broken shoe, and something much worse – implies passengers are being transported to a dreadful end. Jean-Luc feels he must act but doesn’t know how. Then one day a train does stop, and a frantic young mother, Sarah Laffitte, thrusts her weeks-old son into his arms.

Druart keeps suspense thrumming throughout, even with readers’ prior knowledge about some characters’ fates. The crushing weight of the Nazi occupation and its impact on Sarah and husband David, as well as Jean-Luc and Charlotte, a nurse he meets at a German hospital, come through clearly. Sam’s physical and emotional reactions are particularly convincing. It catches at the heart that there are no villains among the five main characters, but their choices cause pain, nonetheless. The ending is as beautiful as one could wish.

While Paris Slept was published by Grand Central in February; I'd reviewed it for February's Historical Novels Review. It's also published in the UK by Headline Review, and in Australia by Hachette.

April 2, 2021

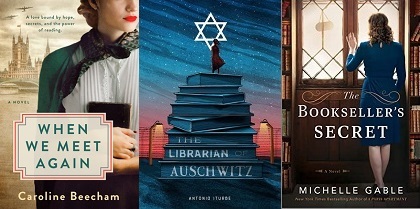

A historical fiction microtrend: World War II, librarians, and books

When We Meet Again by Caroline Beecham (Putnam, Jul. 2021), her first novel to be published in the US, focuses on a woman employed in London's publishing industry in 1943 and her plight following an unintended pregnancy. Antonio Iturbe's The Librarian of Auschwitz (2017), marketed towards YAs but suitable for adults as well. reveals the story of Holocaust survivor Dita Kraus who, as a teenager, courageously guarded eight books within the Auschwitz death camp. Nancy Mitford, one of the famous Mitford sisters, stars in Michelle Gable's The Bookseller's Secret (Graydon House, Aug.), a multi-period novel which depicts her time as a bookshop manager and literary salon hostess in 1940s London.

So many of these novels are set in London and Paris! Janet Skeslien Charles' The Paris Library (Atria, Feb. 2021) reveals the heroic actions of the staff at the American Library in Paris during the Nazi occupation. Third in her Sunrise at Normandy series, The Land Beneath Us by Sarah Sundin (Revell, 2020) tells the romantic story of a library worker at Camp Forrest, Tennessee, who exchanges letters with her new husband after he's sent to fight overseas. And Mario Escobar's The Librarian of Saint-Malo (Thomas Nelson, June 2021) takes place in Nazi-occupied Brittany and a woman who dares to save books that the Nazis are purging from St.-Malo's libraries.

Kristin Harmel's multi-period The Book of Lost Names (Gallery, Jul. 2020), like the previous book, focuses on Nazi soldiers' looting of European libraries; in contemporary times, a librarian comes across a book that holds codes only she can decipher. Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows' The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008), now a modern classic with a film version, revolves around a book club on Guernsey during wartime and celebrates how books can unite people. Lastly, Madeline Martin's The Last Bookshop in London (Hanover Square, Apr. 2021), set during the Blitz, centers on a young bookshop employee and how storytelling can keep hope alive.

March 30, 2021

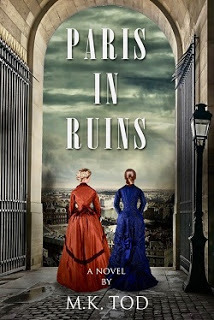

Delights of a Research Trip to Paris, an essay by M. K. Tod, author of Paris in Ruins

~

Delights of a Research Trip to ParisM. K. Tod

Paris In Ruins is set during the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris, and the Paris Commune. I arrived at these momentous events not by design but by calculating when two characters from an earlier novel, Lies Told In Silence, would be roughly twenty years old. I had imagined a novel about friendship between these very different women with a dash of romance and perhaps some tangled family dynamics. However, when I discovered a war, a siege, and a bloody insurrection, the plot took on much more drama.

Paris In Ruins is set during the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris, and the Paris Commune. I arrived at these momentous events not by design but by calculating when two characters from an earlier novel, Lies Told In Silence, would be roughly twenty years old. I had imagined a novel about friendship between these very different women with a dash of romance and perhaps some tangled family dynamics. However, when I discovered a war, a siege, and a bloody insurrection, the plot took on much more drama.Three earlier novels dealt with World War I, an era recent enough that I knew people (my grandparents) who had lived through it, and once augmented with sound research, could imagine their lives and how that war had affected them. But 1870 Paris required a different approach in order for the time and place to come alive. What did Paris look like? What were the norms and expectations for young women of the upper class? Where did they live and shop? What entertainment was available? How did they travel? What clothing styles were prevalent? What did they talk about? Where did they get their news? Layered on top of that were questions about politics and government, military matters, life under siege, and the origins of unrest and rebellion.

During the early months of 1870, Prussia engineered a crisis that threatened the security of France. By the middle of July, the two countries were at war. The Prussian army had superior numbers, leadership, and technology, and on September 2nd, Napoleon III surrendered after huge losses at the Battle of Sedan. By September 15th, the Prussian army reached the outskirts of Paris. By the 19th, Paris was totally surrounded. The siege lasted until the end of January 1871, but the turmoil continued and two months later, radical republicans overthrew the government and established the Paris Commune. For ten weeks, the Commune carried out acts of murder, assassination, pillage, robbery, blasphemy, and terror, until finally expiring in blood and flames.

“We have to go to Paris,” I said to my husband. “I need to walk the streets, watch the people, explore the history, and get a feel for living there.”

We’d been to Paris before, but never for more than a few days. What I was imagining was something more intense, a chance to live almost like Parisians do. Fortunately, my husband jumped at the opportunity and soon, he had rented an apartment in the 17th arrondissement for three weeks and booked our flights. By this time, I had many chapters written and a solid outline for the rest. With the story concept in hand, I created a master list of places to see and things to do and the topics I needed to further understand.

After a day of settling in, buying groceries, wine and other important items, and exploring our local neighborhood, we began to tackle my list. Armed with a map, a slim guidebook, and our cameras, each day we walked for miles, taking pictures at what seemed like every street corner. We visited museums and beautifully restored grand homes. We went to Versailles. We climbed the hill to Montmartre and walked its narrow streets. We went to the top of the Pantheon and the Arc de Triomphe. We visited a fan museum. While browsing in a used bookstore on the Left Bank, I found and purchased a book titled Fashion Design: 1850-1895. Another prize from that trip is a map of Paris 1871 which was on sale at one of the museums and now hangs in a lovely frame beside my desk. I used the map regularly to understand the city’s layout as well as the existence of particular streets during the time of Paris in Ruins.

For a look at military matters, we wandered through a museum in Montmartre that featured scenes from the Paris Commune and visited Musée De l’Armée, the National Military Museum, where a display featuring women who participated in the Commune gave me the idea of having a woman become a soldier in the National Guard.

We sat in cafés and watched the comings and goings of Parisians, the way they talked, their gestures and body language. We had lunch at Restaurant Polidor, a wood-paneled place with thick beams holding up the ceiling and a cluttered bar at the back and simple tables and chairs. Le Polidor dates from 1845 and just might have been the place where radicals gathered to plot an attempted coup in October 1871. We admired a display at the Louvre that featured gowns, suits, accessories, furniture, and photographs from the 1870s. We walked in and out of shops that had been built before 1870. We climbed to the top of the Pantheon where Camille and Mariele went to watch one of the battles and the Arc De Triomphe where Camille watched the conflagration and wondered whether Andre would survive. We stood where the Tuileries Palace once was and tried to imagine its splendor before it was burned by the Commune, never to be rebuilt.

We walked the wide boulevards and the narrow side streets of almost every arrondissement. We strolled along the Seine and saw the chestnut trees with their conical white or pink blossoms and walked through the Luxembourg gardens where the Medici Fountain glistened in the sun. On one sublime afternoon, we listened to a concert while sitting amid the sparkle of the stunning stained-glass windows of Sainte-Chapelle.

Of particular interest were the hotel particuliers – grand homes – we visited: Musée Cognacq-Jay, Musée Jacquemart-Andre, Musée Carnavalet, and Musée Nissim de Camondo. I wanted to understand how my two main characters, both from wealthy Parisian families, might have lived including the layout of such homes, the décor, the furnishings, the paintings and other accoutrements of their lives. The splendour and luxury were astonishing and although these home inspired only a few brief descriptions in the novel, they gave me images that I carried around in my head as I wrote.

Musée D’Orsay never disappoints. It’s home to a superb collection of impressionist works of art. However, on this visit, I looked for paintings done in the late 1860s and early 1870s, paintings of Paris, of fashion, of homes and cafés that might spark a scene and help me imagine the lives of both rich and poor. Frédéric Bazille, Claude Monet, Henri Fantin-Latour, Berthe Morisot, and others provided such inspiration. Three weeks of immersion in the world of Paris was not only a spectacular trip but also a wonderful way to absorb the feel of the city, to watch the people interact, to listen to the language, to see the trees and flowers in bloom, and to let my imagination roam. A lingering sense of being there continued to guide the writing of Paris In Ruins.

I’m grateful to Sarah Johnson for having me on her blog today. I know I speak for many other authors in expressing gratitude for Sarah’s ongoing efforts to promote the presence and enjoyment of historical fiction.

~

About Paris in Ruins:

A few weeks after the abdication of Napoleon III, the Prussian army lays siege to Paris. Camille Noisette, the daughter of a wealthy family, volunteers to nurse wounded soldiers and agrees to spy on a group of radicals plotting to overthrow the French government. Her future sister-in-law, Mariele de Crécy, is appalled by the gaps between rich and poor. She volunteers to look after destitute children whose families can barely afford to eat.

Somehow, Camille and Mariele must find the courage and strength to endure months of devastating siege, bloody civil war, and great personal risk. Through it all, an unexpected friendship grows between the two women, as they face the destruction of Paris and discover that in war women have as much to fight for as men.

War has a way of teaching lessons—if only Camille and Mariele can survive long enough to learn them.

About the author:

M.K. (Mary) Tod writes and blogs about historical fiction. Her latest novel, Paris in Ruins is available on AmazonUS, AmazonCanada, Kobo and Barnes & Noble. She can be contacted on Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads or on her website www.mktod.com.

March 29, 2021

Winner and finalist for the 2020 Langum Prize in American Historical Fiction

The winner is The Cold Millions by Jess Walter (Harper, 2020), set in the early 20th century. From the selection committee's commendation:

The winner is The Cold Millions by Jess Walter (Harper, 2020), set in the early 20th century. From the selection committee's commendation: "Jess Walter’s The Cold Millions is a novel of the burgeoning Pacific Northwest that presents history through an engaging storytelling voice brimming with both humor and pathos.... The history of this period of labor unrest is woven seamlessly into the plotting, allowing The Cold Millions to illuminate an era that is often overlooked. Walter’s characterization and multiple narrative perspectives, from Pinkertons to burlesques, add even more color to an already vibrant portrayal of the tramp lifestyle amid the industrialization of the Pacific Northwest. The result is an entertaining and riveting read."

And the finalist for 2020 is The Book of Lost Light by Ron Nyren (Black Lawrence Press). From the commendation:

"Set in San Francisco and surrounding areas at the turn of the 19th century, this novel portrays the activities of an eccentric tiny family.... The prose is engaging and the descriptive passages illuminative. We read a vivid description of the San Francisco earthquake and its effects on the everyday citizenry of San Francisco. There is much here on the history of photography. There is considerable discussion of [Eadweard] Muybridge and his and other early photographers’ work, and this gives the reader a good sense of the period and a feel for technological innovation in photography during this period. The book feels fresh."

"Set in San Francisco and surrounding areas at the turn of the 19th century, this novel portrays the activities of an eccentric tiny family.... The prose is engaging and the descriptive passages illuminative. We read a vivid description of the San Francisco earthquake and its effects on the everyday citizenry of San Francisco. There is much here on the history of photography. There is considerable discussion of [Eadweard] Muybridge and his and other early photographers’ work, and this gives the reader a good sense of the period and a feel for technological innovation in photography during this period. The book feels fresh."Congratulations to both authors!

The Langum Prize celebrates the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." For more information, please see the Langum Foundation website.

March 27, 2021

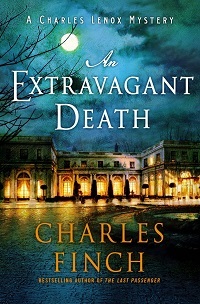

An Extravagant Death by Charles Finch sends his Victorian detective overseas to Gilded Age Newport

In this fourteenth volume of his Charles Lenox mysteries, Finch changes things up by sending his refined detective-hero on a jaunt to America.

In this fourteenth volume of his Charles Lenox mysteries, Finch changes things up by sending his refined detective-hero on a jaunt to America. In 1878, following Lenox’s successful exposure of a corruption scandal at the heart of Scotland Yard, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli judges it politically prudent for Lenox to be out of the country when the trial gets underway, so he engineers an overseas tour in which Lenox will meet with American law enforcement about current methods of detection. With his successful business and growing family (including infant daughter Clara), Lenox never got the opportunity to explore the world as he'd once dreamed. His wife Lady Jane, always a wise and steadying influence, encourages him to go.

Then his train trip from Manhattan to Boston gets derailed (figuratively) when the bodyguard for William Schermerhorn IV boards Lenox’s car and requests that he investigate a crime in Newport, Rhode Island, the summer residence of New York’s moneyed elite. The body of Miss Lily Allingham, a noted beauty, was found below a cliff in the wee hours following a fancy-dress ball. Her two suitors are the most likely suspects. The request disconcerts Lenox, since it smacks of entitlement: he doesn’t like acting at anyone’s beck and call.

Lenox is immensely likeable, always a plus in a series with a recurring protagonist. His methodology is thoughtful, he loves his family and has many dear friends, and he’s a witty observer of (and participant in) the social rituals of Victorian England – both city and countryside. Gilded Age America has its own unofficial aristocracy, though, and Lenox’s mental adjustments to the differences from England are fun to observe. Between the Knickerbockers with their Old-World city wealth and the enormous but tightly packed “cottages” gracing Newport’s coastline, Lenox is simply agog at the ostentatious opulence.

Lenox gains a potential protégé, a rich man’s son who yearns to be a detective, and sees his own past reflected in the younger fellow. Also tying this book together neatly with the recent prequel trilogy is a character Lenox meets up with in Newport, someone who made their first appearance in The Last Passenger, set over two decades earlier.

The mystery plot proceeds apace, but the culprit isn’t obvious. Few can imagine anyone who wanted Miss Allingham out of the picture. The solution, when it arrives, doesn’t feel wholly satisfying for several reasons, but Lenox is such good company that this shouldn’t deter anyone from pursuing his future adventures.

An Extravagant Death was published by Minotaur in February; thanks to the publisher for the review copy.

March 25, 2021

Reading the Past turns 15 years old today

I first started blogging regularly at Reading the Past on March 25, 2006, so today the blog is celebrating its 15th birthday.

I first started blogging regularly at Reading the Past on March 25, 2006, so today the blog is celebrating its 15th birthday. Over this time, the blog has had over 1600 posts, over 1.9 million pageviews, and over 11,000 comments, which kind of blows my mind. Every so often I debate moving to a new platform, but as anyone who collects physical books knows, the process of moving becomes more difficult the more content you accumulate.

In acknowledgment of the anniversary, I changed out the header image for the blog recently with a new photo, this time of Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire... and I'm looking forward to being able to travel again someday.

While blogging has diminished in popularity over time, I'm glad to see new historical fiction blogs continuing to pop up and think (hope!) there'll always be spaces for book lovers to congregate online, share reviews and opinions, and post thoughts about what they're reading.

Although it's a bit hard to get in a celebratory mood with everything that's been going on in the U.S. and world recently, I did want to mark the occasion somehow. Look for a giveaway sometime in the near future.

As a look back to this blog's extended history, I thought I'd share details on what the most popular posts have been over time. Counting down from #15 to #1, we have:

#15: The late T.D. (Tim) Griggs' guest post about the Boer War.

#14: Listing of the bestselling historical novels from 2009.

#13: Listing of the bestselling historical novels from 2011. Publishers Weekly no longer collates these annual roundups, alas.

#12: Historical fiction picks from BookExpo America from 2011.

#11: Zenobia Neil's guest post about diversity in the ancient world.

#10: Analysis of the so-called "Puritan Maiden's Diary," a supposed primary source from the 17th century which turned out to be a fake written in the 19th century.

#9: My review of Sarita Mandanna's novel Tiger Hills, set in 19th- and 20th-century India.

#8: Guest post from Victoria Wilcox about point of view in historical fiction. If you haven't read her trilogy about Doc Holliday, I highly recommend it.

#7: Guest post from Frances Hunter about Fanny Clark O'Fallon, sister of George Rogers Clark and William Clark, a character in their novel The Fairest Portion of the Globe.

#6: My thoughts on the similarities between two Pack Horse Librarian historical novels. I'm surprised these rumors haven't died down by now, but the post continues to get traffic, week after week.

#5: David J. Cord's guest post on Aristotle and accuracy in historical fiction.

#4: Listing of the bestselling historical novels from 2012.

#3: C. W. Gortner's guest post about Marlene Dietrich, subject of his novel Marlene.

#2: Barbara J. Taylor's guest post about the Billy Sunday snowstorm in Philadelphia in 2014.

#1: My 1000th blog post, from 2014, with looked at another blog milestone and included a preview of ten new and upcoming historicals.

Thanks to all the readers who've been following my posts, whether you're new arrivals or longtime subscribers, and to all the authors who've contributed essays and written books that I've covered here. I appreciate it! If you've found new reads or authors via this blog, I'd love to hear about it.

March 22, 2021

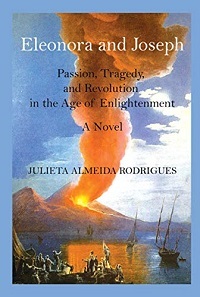

The Role of Minor Characters in Historical Fiction, an essay by Julieta Almeida Rodrigues, author of Eleonora and Joseph: Passion, Tragedy, and Revolution in the Age of Enlightenment

~

The Role of Minor Characters in Historical FictionJulieta Almeida Rodrigues

About Eleanora and Joseph:

As the novel opens, aristocratic Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel pleads with the High Court of Naples to be beheaded instead of hanged like a criminal. One of the leading revolutionaries of her time, Eleonora contributed to the establishment of the Neapolitan Republic, based on the ideals of the French Revolution. Imprisoned in 1799 after the return of the Bourbon Monarchy – due to her work as editor-in-chief of Il Monitore Napoletano – and while waiting to be sentenced, she writes a memoir. Here, she discusses not only her revolutionary enthusiasm, but also the adolescent lover who abandoned her, Joseph Correia da Serra. While visiting Monticello many years later, Joseph discovers Eleonora's manuscript in Thomas Jefferson's library. Now retired, Jefferson is committed to founding the University of Virginia and entices Correia with a position when the institution opens. As the two philosophes explore Eleonora's writing through the lens of their own lives, achievements, and follies, they share many intimate secrets.

As the novel opens, aristocratic Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel pleads with the High Court of Naples to be beheaded instead of hanged like a criminal. One of the leading revolutionaries of her time, Eleonora contributed to the establishment of the Neapolitan Republic, based on the ideals of the French Revolution. Imprisoned in 1799 after the return of the Bourbon Monarchy – due to her work as editor-in-chief of Il Monitore Napoletano – and while waiting to be sentenced, she writes a memoir. Here, she discusses not only her revolutionary enthusiasm, but also the adolescent lover who abandoned her, Joseph Correia da Serra. While visiting Monticello many years later, Joseph discovers Eleonora's manuscript in Thomas Jefferson's library. Now retired, Jefferson is committed to founding the University of Virginia and entices Correia with a position when the institution opens. As the two philosophes explore Eleonora's writing through the lens of their own lives, achievements, and follies, they share many intimate secrets. Told from Eleonora and Joseph's alternating points of view, the interwoven first-person narratives follow the characters from the elegant salons of Naples to the halls of Monticello, from the streets of European capitals such as Lisbon, London, and Paris to the cultured new world of Philadelphia and the chic soirées in Washington. Eleonora and Joseph were both prominent figures of the Southern European Enlightenment. Together with Thomas Jefferson, they formed part of The Republic of Letters, a formidable network of thinkers who radically influenced the intellectual world in which they lived - and which we still inhabit today.

~

I still do not fully comprehend why I have such fondness for the three minor characters I created in Eleonora and Joseph. Maybe the reason is that I see them as stepping-stones to connect the novel’s dots. As I was writing the book, these characters seemed to have a life of their own, popping out of my mind to solve plot issues I needed to address. We know how a novel thrives on conflict between major protagonists to advance to its conclusion. Those minor figures, however, far from conflicting, helped shape the narrative’s details. As a result, I developed a sense of wonder about them. Like in a magician’s show, they emerged from my imagination as stars from inside a top hat.

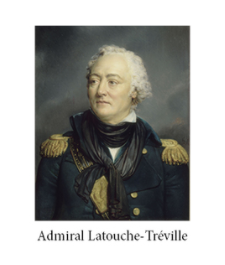

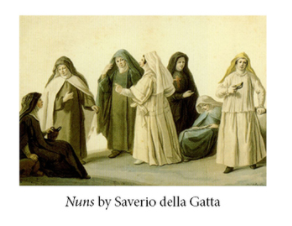

Two of these figures existed: Eduardo (Edward) José Correia da Serra (1803-?) – son of Joseph, a Portuguese abbot – and Louis René Latouche-Tréville (1745-1804). I needed them for my plot, and they were there for me! Suor Amadea della Valle, a nun, is a person belonging to a ubiquitous social group in eighteenth-century Naples but a character of my imagination.

Two of these figures existed: Eduardo (Edward) José Correia da Serra (1803-?) – son of Joseph, a Portuguese abbot – and Louis René Latouche-Tréville (1745-1804). I needed them for my plot, and they were there for me! Suor Amadea della Valle, a nun, is a person belonging to a ubiquitous social group in eighteenth-century Naples but a character of my imagination.I will address Eduardo as Edward – the English translation of his name I use throughout the book. I would have enjoyed meeting this young man in real life! Edward seems to have had a formidable Parisian education and to have enjoyed his stay in America. Most probably he had ambivalent feelings about his paternity when he was young; but the Abbé certainly visited often mother and son while he was in Paris. The bond developed between the two men at that time must have been the basis for a satisfying relationship later on. Correia da Serra arrives in America in 1812, therefore Edward lived alone with his mother after the age of nine. The name Esther (Delavigne) suggests Edward’s mother was Jewish.

Abbé Correia, by Domenico

Abbé Correia, by Domenico Pellegrini (1759–1840)In the so-called “Memórias” of the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon, there is a letter where Correia thanks a Parisian friend for lending him some money for Esther and Edward. The letter is written in New York and dated of 1813. The writing is in French and he addresses Edward as his ‘petit filleul’, “little godson’. It is not known when Edward arrived in America to be with his father, but in 1817 he is at St. Mary’s College in Baltimore. Before that, father and son lived in a boarding house in Philadelphia. In the correspondence below, Edward speaks fondly of their occupants. At one point, he says he has been to Monticello with his father and that he recalls how Jefferson loathed newspapers in the later part of his life. This is the reason why I included in my novel a description of one of Edward’s visits to Monticello.

At the end of The Abbé Correa in America (1812-1820) – a book about the correspondence between Correia da Serra and Jefferson – Richard Beale Davis includes a few letters that Edward wrote to several people in America after father and son left the country. Almost all I know about Edward comes from these letters. The tone is polite, deferential, intelligent, and liberal.

As I proceeded to explore his character, I kind of worried for Edward. Beale describes how he was introduced as his father’s secretary or nephew in America. How horrible Edward must have felt! The family secret, however, must have been disclosed to Thomas Jefferson during an intimate conversation in Monticello. When encouraging his friend to accept, one day, a teaching position at the University of Virginia, Jefferson tells Correia to settle in Virginia with his family. Moreover, he offers his house for the family to stay.

I also wondered what Edward thought about his father’s confession to the inquisition. In his letters, Edward mocks the provinciality of life in Lisbon, the despotism of priests, and the inquisition’s instruments of torture. If so, how would he view his father’s confession, once he found out about it? Even if the Catholic Church kept those documents undisclosed, Edward was bound to find out about them one way or another. What a stain in his father’s character! This is why I conceived a paragraph or two at the end of the novel where Correia considers the best way to discuss the issue with his son. He wants to ask for Edward’s forgiveness, and is undecided as to the best way to proceed. Would it be better to have a conversation with him, or write a letter his son could read after his death?

Curiously, Edward mentions in one of his letters a job he holds for a while in the Department of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon. He hates the job, considering it beneath his capability. Moreover, he describes how pleasing it is that the building where he works – a public building now – had been in the past an Inquisition palace. I quote Edward: “an ancient temple of cruel superstition.” He is keen to leave Lisbon and move to Paris to study medicine, he wants to have the same profession his grandfather once held.

Edward seems to get along quite well with his famous father, another endearing trait.

~

Louis René Latouche-Tréville is the dashing French Admiral who, in real life, arrived at the bay of Naples in late 1792 commanding a French squadron at the head of a warship, the Languedoc. As he announced, he was ready to reduce Naples to “rubble,” as the French Republic took offense on a diplomatic incident with the Kingdom of Naples. Latouche-Tréville was a French aristocrat who early on had joined the French Revolution, and was elected a deputy to the Tiers-État, in 1789. He renounced his title to serve the French Republic and fight for the sans-culottes, the people!

Besides this stupendous credential, of the outmost importance to the Neapolitan revolutionaries, the Admiral had served in the American War of independence. The French had given him the immense privilege of transporting aboard L’Hermione the Marquis de Lafayette during his second voyage to America. The frigate also carried supplies, munitions and troops to help Americans fight for their independence.

Besides this stupendous credential, of the outmost importance to the Neapolitan revolutionaries, the Admiral had served in the American War of independence. The French had given him the immense privilege of transporting aboard L’Hermione the Marquis de Lafayette during his second voyage to America. The frigate also carried supplies, munitions and troops to help Americans fight for their independence. Eleonora goes on board when the admiral decides to provoke the king and queen of Naples and invites the Neapolitan Jacobins to a banquet aboard the Languedoc on January 12, the king’s birthday. Daring as she had become, Eleonora attends the festivities with her compatriots, the only woman among, maybe, two hundred guests! She feels she has nothing to lose at this point in her life.

In the novel, Eleonora ends up falling in love with the French naval hero and, for her, the meeting is transformational. She says that since the time she was in love with Correia da Serra, she hadn’t felt that way. Latouche-Tréville had her sit at the main table, to his right, and they discussed the current political events in both their nations. As the conversation proceeds, they fervently smiled and glanced at each other. Among Phrygian caps and tricolor cockades, the two end up the evening dancing on the warship’s deck at the sound of patriotic songs the French sailors chant.

After this moment there is no going back for Eleonora. She is fully committed to a radical change, and to help install a Republican government in Naples. She has learned in the flesh that, if the French revolutionaries can change a government, so can Neapolitans if they so chose. When in prison later, she dreams of the flamboyant French admiral and his invitation to see him in France. When she is in the Bay of Naples ready to go into exile, it is him who comes into her mind as she envisions a new life. At this point in the novel, the political and the romantic reverie became for her, truly, one.

I feel very pleased to have imagined Eleonora falling in love late in life; in 1793 she was forty-one years old. But, this, of course, is totally within her character.

~

I put in Suor Amadea della Valle’s words what the diarist Carlo de Nicola ‒ someone who recorded the Neapolitan Republic in great detail between 1798 and 1800 ‒ said about Eleonora the day she was hanged. She is in the crowd in Piazza Mercato watching the event.

Suor Amadea is a character of my imagination. I made her the Madre Superiore, the nun in charge of the Vicaria Prison, the women’s section. Not an unlikely situation, since many religious orders were involved in public and community work, devoting their lives to ameliorating the condition of the destitute.

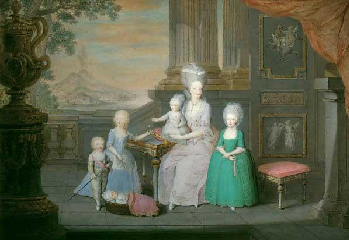

Sour Amadea had to enter the novel at an early stage so that she and Eleonora could develop a close relationship throughout the years. So I had her pay a visit to Queen Carolina when Eleonora is the queen’s librarian. As the Madre Superiore, Suor Amadea had to be literate (as only members of the high classes of Naples were). She goes to the Royal Palace to ask for royal assistance in helping the prisoners acquire the rudiments of reading and writing. The majority of Neapolitans were illiterate, it being common to sign one’s name by making the sign of the cross.

Queen Carolina and her children

Queen Carolina and her childrenAs Eleonora writes her memoir in secrecy while in her filthy prison cell – awaiting her sentence – her account must be found later, after she dies. Suor Amadea had placed her old friend in a cell by herself, and had given her a table to write, parchment paper, a quill pen, and a jug of ink. She shows Eleonora the table’s secret compartment, where she advises her to hide all those objects. Given the appalling conditions of a Neapolitan prison in the late eighteenth century, only a devoted friend would provide Eleonora with such luxuries.

I see Suor Amadea as one of the nuns portrayed by Saverio della Gatta, which I have also included in the Gallery page of my website. She is the one fully dressed in the olive green habit, with the matching green hood. She is plump, and friendly, and warm-hearted. Like Eleonora, Suor Amadea is also of Portuguese descent, a link both women discuss when they originally meet at the Royal Palace.

I see Suor Amadea as one of the nuns portrayed by Saverio della Gatta, which I have also included in the Gallery page of my website. She is the one fully dressed in the olive green habit, with the matching green hood. She is plump, and friendly, and warm-hearted. Like Eleonora, Suor Amadea is also of Portuguese descent, a link both women discuss when they originally meet at the Royal Palace. Amadeu Lopes Sabino calls Suor Amadea a feminist avant la lettre, someone ahead of her times. And this is exactly how I see her. Her sense of solidarity towards Eleonora, despite her official position as the prison head, is palpable throughout the novel.

Suor Amadea understands Eleonora both at a human and a spiritual level. She offers comfort to her friend, she is kind and compassionate – even if there is really nothing she can do to alter the course of events. She acts courageously, albeit covertly, while Eleonora is at the Vicaria prison under her official surveillance. She is surrounded by nuns, and she knows some are cruel and ruthless; one among them could denounce her for aiding a convict. Eleonora is not a common prisoner; she is a political prisoner who risked defying the Neapolitan monarchy. Suor Amadea’s discretion is imperative to bring her own plan to fruition: if Eleonora is to die, her memoir must survive. To find out what she does, one must read my novel!

March 19, 2021

Cloudmaker by Malcolm Brooks, a coming-of-age novel about the frontier of flight in '30s Montana

Brooks (Painted Horses, 2014) evokes rural Montana’s magnificent beauty in his coming-of-age novel set during aviation’s Golden Age, an era marked by technical ingenuity and the allure of wide-open skies.

Brooks (Painted Horses, 2014) evokes rural Montana’s magnificent beauty in his coming-of-age novel set during aviation’s Golden Age, an era marked by technical ingenuity and the allure of wide-open skies. In the small town of Big Coulee in 1937, fourteen-year-old Houston “Huck” Finn yearns to build and fly an airplane and has the chops to achieve it. With his Pop’s support and the help of a new machinist, “Yak” McKee, Huck works diligently while hiding the project from his overprotective, religious mother.

His sophisticated eighteen-year-old cousin, Annelise, a pilot-in-training banished from California to preserve her reputation after a romantic liaison, arrives expecting dreary exile but instead finds her excitement rekindled by Huck’s enterprise. Danger and mystery enhance the plot when gangsters seek to reclaim an expensive watch Huck had pulled off a dead man found in a local creek.

The cast and their interactions are wonderful, and digressions into their personal stories deepen the characterizations and historical backdrop. An entrancing tale about the challenges of pursuing one’s dreams and of American frontiers, old and new.

Cloudmaker was published this month by Grove. I'd read the novel earlier this winter and wrote this draft for Booklist (the review ran in the 2/15/21 issue).

March 12, 2021

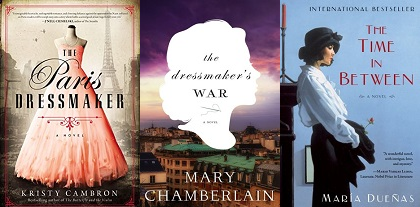

A historical fiction microtrend: World War II and fashion

If you search for "dressmaker" on Goodreads, you'll find mostly historical fiction. Two of these are Kristy Cambron's new release The Paris Dressmaker, focusing on women who used fashion as a tool for Resistance work during the Nazi occupation, and Mary Chamberlain's The Dressmaker's War (UK title The Dressmaker of Dachau), about a naïve young British dressmaker taken prisoner and forced to work for the Nazis. María Dueñas' debut novel, The Time in Between, recounts the journey of a Spanish seamstress in Morocco during the Spanish Civil War and back in Europe during the lead-up to WWII. I've had this one on my TBR for way too long.

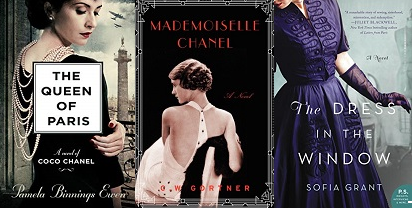

The full life of designer and businesswoman Coco Chanel is envisioned in C. W. Gortner's Mademoiselle Chanel, while Pamela Binnings Ewen's The Queen of Paris centers on the controversies surrounding Chanel's WWII-era life in Paris. Sofia Grant's The Dress in the Window, set just after the war in America, focuses on the relationship between two designer sisters.

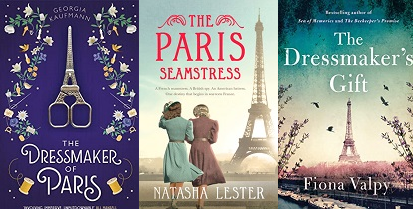

Georgia Kauffman's The Dressmaker of Paris sweeps from Italy to Switzerland, Paris, Rio, and New York as its heroine reveals her unusual story. As you can guess from the covers, the remaining two novels also evoke the City of Light: Natasha Lester's The Paris Seamstress is a dual-time novel set in WWII-era Paris and contemporary times. The Dressmaker's Gift by Fiona Valpy, another multi-time saga, follows three intrepid seamstresses, the secrets they keep, and how these mysteries reverberate two generations later.