Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 39

November 5, 2020

The Evening and the Morning, Ken Follett's epic prequel to The Pillars of the Earth

Over a century before The Pillars of the Earth, the future English cathedral town of Kingsbridge is a mere hamlet with a stone church, ferry, alehouse, and a scattering of humble buildings. Follett’s supremely entertaining prequel centers on the locale known then as Dreng’s Ferry – named after a surly business owner – and the city of Shiring, while dramatizing their inhabitants’ interactions around the first millennium CE.

Over a century before The Pillars of the Earth, the future English cathedral town of Kingsbridge is a mere hamlet with a stone church, ferry, alehouse, and a scattering of humble buildings. Follett’s supremely entertaining prequel centers on the locale known then as Dreng’s Ferry – named after a surly business owner – and the city of Shiring, while dramatizing their inhabitants’ interactions around the first millennium CE. Three plucky protagonists have ambitious dreams that set them apart. Edgar, an illiterate boatbuilder with an engineer’s mind, loses his lover to a brutal Viking raid and works to raise his family out of poverty. Lady Ragna, the Count of Cherbourg’s daughter, leaves Normandy to marry her wealthy betrothed but is dismayed by her new life’s reality. And a monk, Brother Aldred, seeks to develop his abbey’s scriptorium and library into an educational beacon. However, with political influence held by a trio of wily brothers and their relatives, anyone stepping outside their societal role risks having their hopes, indeed their very lives, crushed. Wynstan, Bishop of Shiring, is a notably formidable nemesis.

Bursting with personality and detailed re-creations of daily life in historic England, this story is vintage Follett. Anyone who loved Pillars will want to scoop it right up. The characters, while belonging to their era, are recognizable types that make it easy to identify with or hiss at them. The momentum never flags, an impressive achievement in a tome that sprawls in length but not setting or time. Two pervasive themes are the corruption of power, and how average people have few choices. King Ethelred is a distant presence, and justice depends on leaders’ personalities and whims. Slave girls suffer particularly violent fates. It is frustrating to see our heroes’ plans so frequently thwarted, but one can’t help but read on, hoping for a better future – as the evocative title signifies.

The Evening and the Morning was published in the US by Viking in September. The UK publisher is Macmillan. I reviewed it from a NetGalley copy for November's Historical Novels Review. At 928pp long, the e-version was easier on my wrists/hands, and the story moved quickly. If you're feeling frazzled with all the election drama, rising Covid rates, and doomscrolling on social media, this book will make a good distraction. Hope you're all holding up OK during these stressful times.

Published on November 05, 2020 13:59

November 2, 2020

The background to Censorettes, a historical novel of WWII-era Bermuda, a post by author Elizabeth Bales Frank

Elizabeth Bales Frank is here today with a guest post about the path she took in writing her novel, Censorettes, which is out on November 5th from Stonehouse Press. The author is a fellow librarian, and the subject she's chosen is fascinating: the young women involved in reading and censoring mail in Bermuda during WWII. Please read on...

~

CensorettesElizabeth Bales Frank

1. Meet the Censorettes

I first learned of the Censorettes from a brief description of the Princess Hamilton Hotel. In the spring of 2006, I was in Bermuda, visiting a friend. I was flipping through one of her guidebooks to find something amusing to do when I came across this description of the Princess Hamilton, “during the war, the basement of the Princess served as a station for the Imperial Censorship Detachment. It was nicknamed the ‘Bletchley of the Tropics.’”

I first learned of the Censorettes from a brief description of the Princess Hamilton Hotel. In the spring of 2006, I was in Bermuda, visiting a friend. I was flipping through one of her guidebooks to find something amusing to do when I came across this description of the Princess Hamilton, “during the war, the basement of the Princess served as a station for the Imperial Censorship Detachment. It was nicknamed the ‘Bletchley of the Tropics.’”

Who would have bestowed such a nickname? Bletchley’s activities were not made public knowledge until decades later. Further, the employees of Bletchley focused their activities on computing and code-breaking, while those of the Imperial Censorship Detachment, initially at least, concentrated on the interception of correspondence and cargo between warring Europe and the neutral United States. And, Bermuda is not in the tropics. It is approximately 700 miles east of Wilmington, North Carolina. Its location was helpful in many American wars, including the Civil War in which, you may recall from Gone with the Wind, Rhett Butler secured his fortune as a blockade runner by diverting shipments of cotton, almost certainly using Bermuda as a way station.

But I am getting ahead of myself. What fascinated me was the description, scant as it was, of the “Censorettes,” young European women hired because of their knowledge of languages or, in some cases, chemistry.

I walked from my friend’s house to the Bermuda Historical Society, passing the Princess Hamilton Hotel, reminding myself that it had during the war been known as the Princess Louise Hotel, after one of Queen Victoria’s many daughters. I stood in its driveway, caressed by (sub) tropical breezes and asked myself, how would a Censorette have felt, to be here, in this demi-paradise, reading mail in a basement, knowing that ‘out there’ – and life on Bermuda must surely consist of a lot of speculation regarding ‘out there’ – the world was in flames? Would she feel relieved at her own safety? Worried about the people back home? Would she be made frantic by her own isolation and helplessness?

I addressed the man at the Bermuda Historical Society, “I’m looking for anything you might have on Bermuda during the Second World War?”

“Won’t find much,” he replied. (In fairness, he was probably a volunteer. He certainly looked weary enough to have lived through the war himself.)

My Censorette was lonely. Perhaps bereaved. Perhaps she studied the ocean, wishing she could swim back home.

At the Bermuda Maritime Museum, I was advised to look into Sir William Stephenson’s book A Man Called Intrepid. I received the same advice at the Bermuda Library. Then, I tucked away my notebook. I was on vacation, after all.

2. Secondary Sources

Won’t find much were prophetic words. A Man Called Intrepid devotes a scant five pages to the entire Bermuda operation. The Censorettes receive an even briefer account, described by their shapely legs and their presumed “romantic” notions of a posting to Bermuda. A story in World War II magazine, “How Bermuda’s ‘Censorettes’ Made a Nest of Spies Disappear,” provided my central mystery. A cover story in the August 18, 1941 edition of Life magazine described the social activities of the Censorettes while focusing a photo spread on the blasting on the island by American troops, the U.S. Navy and the Army Corps of Engineers, who had arrived on the island as a result of the Destroyer for Bases Act (later folded into the Lend-Lease Act) to create a Navy air base and Kindley Field, the airfield which is still in use today.

Handsome men, clever girls with “shapely” legs – I began to presume “romantic” notions myself.

I would call my heroine Lucia, I decided. Lucy to her friends.

3. Primary Sources, Librarians, and Archivists

author Elizabeth Bales FrankI wrote to the curator of the U.S. Naval Museum, the historian for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a librarian at the Bermuda National Library, who was kind enough to photocopy several issues of the Royal-Gazette from 1941 so I could see what kind of public information would be available to my homesick Censorettes. An inquiry to the Imperial War Museum in London resulted in the location of an account of her time as a Censorette by Gwendolyn Peck (née Owen) tucked away in a folder.

author Elizabeth Bales FrankI wrote to the curator of the U.S. Naval Museum, the historian for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a librarian at the Bermuda National Library, who was kind enough to photocopy several issues of the Royal-Gazette from 1941 so I could see what kind of public information would be available to my homesick Censorettes. An inquiry to the Imperial War Museum in London resulted in the location of an account of her time as a Censorette by Gwendolyn Peck (née Owen) tucked away in a folder.

I decided that Lucy, in addition to being fluent in Italian due to her Italian mother, should also have fluency in French and German and an education from Girton College, Cambridge (one of the few colleges that accepted women at the time). What did I know of the Girton College curriculum in 1939? Nothing, but Hannah Westall, the archivist of Girton College, supplied all the information I needed.

Each librarian and archivist I reached out to was not only courteous and thorough in their response, devoting hours to my questions, but encouraging and enthusiastic about the novel. Their professionalism was not the only factor, but certainly a major one, in my decision to attend library school myself in the spring of 2014. It is now fourteen years since I first studied that pink hotel, fourteen years of researching, correspondence and why not, while I’m at it, pursuing a master’s degree in library science. Now I have a novel and an MLIS, and will be someday in the position to return the favor to another novelist.

~

Elizabeth Bales Frank is the author of the historical novel Censorettes (Stonehouse Publishing, November 5, 2020). Her previous novel was Cooder Cutlas, published by Harper & Row. Her essays have appeared in Glamour, Cosmopolitan, The Sun, Barrelhouse, Post Road, Epiphany, The Writing Disorder and other literary publications. She was awarded a residency at Ragdale. Frank earned a BFA in film from New York University, and an MLIS from the Pratt Institute. She lives in New York City. Her website is https://elizafrank.com.

~

CensorettesElizabeth Bales Frank

1. Meet the Censorettes

I first learned of the Censorettes from a brief description of the Princess Hamilton Hotel. In the spring of 2006, I was in Bermuda, visiting a friend. I was flipping through one of her guidebooks to find something amusing to do when I came across this description of the Princess Hamilton, “during the war, the basement of the Princess served as a station for the Imperial Censorship Detachment. It was nicknamed the ‘Bletchley of the Tropics.’”

I first learned of the Censorettes from a brief description of the Princess Hamilton Hotel. In the spring of 2006, I was in Bermuda, visiting a friend. I was flipping through one of her guidebooks to find something amusing to do when I came across this description of the Princess Hamilton, “during the war, the basement of the Princess served as a station for the Imperial Censorship Detachment. It was nicknamed the ‘Bletchley of the Tropics.’”Who would have bestowed such a nickname? Bletchley’s activities were not made public knowledge until decades later. Further, the employees of Bletchley focused their activities on computing and code-breaking, while those of the Imperial Censorship Detachment, initially at least, concentrated on the interception of correspondence and cargo between warring Europe and the neutral United States. And, Bermuda is not in the tropics. It is approximately 700 miles east of Wilmington, North Carolina. Its location was helpful in many American wars, including the Civil War in which, you may recall from Gone with the Wind, Rhett Butler secured his fortune as a blockade runner by diverting shipments of cotton, almost certainly using Bermuda as a way station.

But I am getting ahead of myself. What fascinated me was the description, scant as it was, of the “Censorettes,” young European women hired because of their knowledge of languages or, in some cases, chemistry.

I walked from my friend’s house to the Bermuda Historical Society, passing the Princess Hamilton Hotel, reminding myself that it had during the war been known as the Princess Louise Hotel, after one of Queen Victoria’s many daughters. I stood in its driveway, caressed by (sub) tropical breezes and asked myself, how would a Censorette have felt, to be here, in this demi-paradise, reading mail in a basement, knowing that ‘out there’ – and life on Bermuda must surely consist of a lot of speculation regarding ‘out there’ – the world was in flames? Would she feel relieved at her own safety? Worried about the people back home? Would she be made frantic by her own isolation and helplessness?

I addressed the man at the Bermuda Historical Society, “I’m looking for anything you might have on Bermuda during the Second World War?”

“Won’t find much,” he replied. (In fairness, he was probably a volunteer. He certainly looked weary enough to have lived through the war himself.)

My Censorette was lonely. Perhaps bereaved. Perhaps she studied the ocean, wishing she could swim back home.

At the Bermuda Maritime Museum, I was advised to look into Sir William Stephenson’s book A Man Called Intrepid. I received the same advice at the Bermuda Library. Then, I tucked away my notebook. I was on vacation, after all.

2. Secondary Sources

Won’t find much were prophetic words. A Man Called Intrepid devotes a scant five pages to the entire Bermuda operation. The Censorettes receive an even briefer account, described by their shapely legs and their presumed “romantic” notions of a posting to Bermuda. A story in World War II magazine, “How Bermuda’s ‘Censorettes’ Made a Nest of Spies Disappear,” provided my central mystery. A cover story in the August 18, 1941 edition of Life magazine described the social activities of the Censorettes while focusing a photo spread on the blasting on the island by American troops, the U.S. Navy and the Army Corps of Engineers, who had arrived on the island as a result of the Destroyer for Bases Act (later folded into the Lend-Lease Act) to create a Navy air base and Kindley Field, the airfield which is still in use today.

Handsome men, clever girls with “shapely” legs – I began to presume “romantic” notions myself.

I would call my heroine Lucia, I decided. Lucy to her friends.

3. Primary Sources, Librarians, and Archivists

author Elizabeth Bales FrankI wrote to the curator of the U.S. Naval Museum, the historian for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a librarian at the Bermuda National Library, who was kind enough to photocopy several issues of the Royal-Gazette from 1941 so I could see what kind of public information would be available to my homesick Censorettes. An inquiry to the Imperial War Museum in London resulted in the location of an account of her time as a Censorette by Gwendolyn Peck (née Owen) tucked away in a folder.

author Elizabeth Bales FrankI wrote to the curator of the U.S. Naval Museum, the historian for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a librarian at the Bermuda National Library, who was kind enough to photocopy several issues of the Royal-Gazette from 1941 so I could see what kind of public information would be available to my homesick Censorettes. An inquiry to the Imperial War Museum in London resulted in the location of an account of her time as a Censorette by Gwendolyn Peck (née Owen) tucked away in a folder. I decided that Lucy, in addition to being fluent in Italian due to her Italian mother, should also have fluency in French and German and an education from Girton College, Cambridge (one of the few colleges that accepted women at the time). What did I know of the Girton College curriculum in 1939? Nothing, but Hannah Westall, the archivist of Girton College, supplied all the information I needed.

Each librarian and archivist I reached out to was not only courteous and thorough in their response, devoting hours to my questions, but encouraging and enthusiastic about the novel. Their professionalism was not the only factor, but certainly a major one, in my decision to attend library school myself in the spring of 2014. It is now fourteen years since I first studied that pink hotel, fourteen years of researching, correspondence and why not, while I’m at it, pursuing a master’s degree in library science. Now I have a novel and an MLIS, and will be someday in the position to return the favor to another novelist.

~

Elizabeth Bales Frank is the author of the historical novel Censorettes (Stonehouse Publishing, November 5, 2020). Her previous novel was Cooder Cutlas, published by Harper & Row. Her essays have appeared in Glamour, Cosmopolitan, The Sun, Barrelhouse, Post Road, Epiphany, The Writing Disorder and other literary publications. She was awarded a residency at Ragdale. Frank earned a BFA in film from New York University, and an MLIS from the Pratt Institute. She lives in New York City. Her website is https://elizafrank.com.

Published on November 02, 2020 05:38

October 28, 2020

Stealing Roses by Heather Cooper, a Victorian tale set on the Isle of Wight

Heather Cooper’s Stealing Roses is a warmly delightful debut novel set in the small seaside town of Cowes on the Isle of Wight in 1862. Aside from brief mentions of Queen Victoria’s summer home at nearby Osborne House, major historical events and figures don’t intrude. The focus is on a young woman’s growing into adulthood amid social change in her immediate world.

Heather Cooper’s Stealing Roses is a warmly delightful debut novel set in the small seaside town of Cowes on the Isle of Wight in 1862. Aside from brief mentions of Queen Victoria’s summer home at nearby Osborne House, major historical events and figures don’t intrude. The focus is on a young woman’s growing into adulthood amid social change in her immediate world. The writing style enhances the sense of period, employing the Victorian tendency toward long, winding sentences and a tone of elevated formality. It makes a nice contrast with the personality of its heroine, 19-year-old Eveline Stanhope, the adventurous youngest daughter in a well-to-do family. She has two older sisters who married well, a mother she loves despite her tendency to meddle and gossip, and a caring aunt. Living with them is Eveline’s former governess, Miss Angell, who would have had nowhere else to go if the Stanhopes hadn’t taken her in.

The building of a railway line between Cowes and Newport alarms Eveline at first, since she shares her late father’s love of natural landscapes and hates to think of the ground being torn up. Over time, she comes to realize the benefits that trains will bring for local fishermen, other businesses, and even their family. Two suitors present themselves in her life: Charles Sandham, nephew of Mrs Stanhope’s good friend and social rival, and chief railway engineer Thomas Armitage, a Yorkshireman.

Eveline is an engaging heroine, a product of her time who recognizes but sets aside the limitations imposed on young women of her class. Eveline’s mother despairs of her interest in photography and desire to go sea-bathing, but as with many things, Mrs. Stanhope can be persuaded to change her mind if she’s told such pursuits are fashionable or progressive. (While she can be flighty and marriage-obsessed on Eveline’s behalf, she’s no Mrs Bennet; over the course of the novel, her character shows significant depth.)

Jane Austen fans should enjoy this novel with its emphasis on family interactions, social responsibility, and the economic position of women. The era depicted in is firmly Victorian, though, and delves into the era’s proprieties and improprieties (with examples both saucy and serious). Some parts of the ending feel too abrupt, but overall, it’s enjoyable to spend time within these pages.

Stealing Roses was published by Allison & Busby last year; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Published on October 28, 2020 07:10

October 22, 2020

Focusing on autumn 2020 historical fiction releases, UK edition

Well, I'd intended to post this preview of autumn 2020 titles from British publishers a while ago, but time got away from me. The good news, though, is that for interested readers, there's no need to wait to get them because many are available now. Here are nine from my personal wishlist. Did any make it to your wishlist as well? Links below go to Goodreads.

Suzannah Dunn has written many insightful historical novels about Tudor personalities, and in The Testimony of Alys Twist (Little Brown UK, Oct.) she chooses a laundress-turned-spy in Princess Elizabeth's household, circa 1553, as her protagonist. Elizabeth (here writing as E.C.) Fremantle's newest historical thriller, The Honey and the Sting (Michael Joseph, Aug.) centers on three women and a secret in early Stuart-era England. The Glorious Guinness Girls by Emily Hourican (Headline Review, Sept.) is about the three real-life Guinness sisters, Anglo-Irish socialites in 1920s Ireland and London, as seen from an outsider's perspective.

I enjoy reading novels based on family history. A More Perfect Union , Tammye Huf's debut (Myriad Editions, Oct.), tells the story of her great-great-grandparents, an Irish immigrant and an enslaved woman, in 1840s Virginia. Naomi Miller's Imperfect Alchemist (Allison & Busby, Nov.) heads back to Tudor England to reveal the life of Mary Sidney, poet and literary patron, alongside that of a maid in her family's household. Continuing her fictional chronicles of medieval women, Anne O'Brien's The Queen's Rival (HQ, Sept.) centers on Cecily Neville, Duchess of York, a powerful figure during the Wars of the Roses (mother of Edward IV and Richard III). Women's lives seem to be a favorite theme of mine...

Caroline Scott's first WWI novel, The Poppy Wife / The Photographer of the Lost, stood out in a crowded field. Her second, When I Come Home Again (Simon & Schuster, Oct), reveals the story of a man with amnesia in a Durham hospital and three women who claim to know him. Acclaimed novelist Rose Tremain's latest work, Islands of Mercy (Chatto & Windus, Sept.) takes place in Bath, England, and in Borneo in 1865; it makes me curious how the novel's settings and characters will intertwine. Lastly Jeremy Vine's The Diver and the Lover , another "inspired by real events" novel, journeys with two English sisters over to Spain in 1951, as Dali begins a new artistic work.

Published on October 22, 2020 14:30

October 19, 2020

We All Fall Down: Stories of Plague and Resilience, nine historically rich tales

I wasn’t always a fan of historical short stories. The format seemed too concise to support the world-building and character depth necessary for the genre. But the more I read, the more I grew to appreciate them. Short stories are powerfully concentrated in terms of character, plot, and historical detail. When done right, the length suits the material perfectly.

I wasn’t always a fan of historical short stories. The format seemed too concise to support the world-building and character depth necessary for the genre. But the more I read, the more I grew to appreciate them. Short stories are powerfully concentrated in terms of character, plot, and historical detail. When done right, the length suits the material perfectly. Several weeks ago, I watched a Zoom panel, “Stories of Plague in the time of Covid,” sponsored by the Historical Novel Society NYC Chapter, over my lunch hour. A collection of international authors who contributed to the We All Fall Down anthology spoke about their stories and took questions. It was one of the best online panels I’ve seen, and now that I’ve read the book, I’m tempted to watch it again.

The book was conceptualized long before the current pandemic, and it’s eerie how well some situations in the nine tales reflect our time. All are set during periods of the Black Death between the 14th and 17th centuries: stories of sorrow, grief, family, love, art, beauty, and the strength to survive after immense loss.

Kristin Gleeson’s “The Blood of the Gaels,” set in Ireland in 1348, follows a young novice as she travels home to her family after getting word of her father’s illness. This unpredictable story has hints of mystery as it showcases the religion, folk beliefs, and laws of the time.

“The Heretic” by Lisa J. Yarde introduced me to a less familiar period, 14th-century Moorish Spain, and to the historical figure of Ibn al-Khatib, personal secretary to the sultan, who observes how the plague is spreading and develops controversial views about how to lessen its severity. I highlighted multiple passages that felt historically relevant and uncannily familiar to today.

Following a girl as she hawks elixirs with her motley group of faith-healers and fraudsters on their travels through 14th-century Siena, Laura Morelli’s “Little Bird” draws readers into the world of the Lorenzetti painters as the “Great Mortality” lands in the city – perhaps, as was thought, as punishment for its residents’ sins. This was one of my favorites, for its re-creation of the tools of the artists’ workshop and the glories of medieval Siena: “The cathedral is a chamber of echoing footsteps and pigeon wings, lit by dozens of gilded altarpieces shimmering in the candlelight.”

As a reader interested in fiction about little-known royal figures, I appreciated J. K. Knauss’s illustration of the life of Leonor de Guzmán, mistress of Alfonso XI of Castile, and the challenges she faces after he dies of plague in 14th-century Seville.

With the poignantly meditative “On All Our Houses,” set in Gargagnago, Italy, in 1362, David Blixt revisits his character Pietro Alighieri (Dante’s son) later in life. Aged 64, Pietro reflects on his existence and the fearsome inevitability of death as his eldest daughter Betha lies dying of plague.

Moving ahead to Venice (Venezia) in 1576, Jean Gill’s “A Certain Shade of Red,” replete with historical detail and symbolism, is narrated by Death himself as he observes the famous painter, Tician (Titian), dying of pestilence, and at earlier moments in his life. Then, as now, political leaders make choices about public health vs. the economy; these passages hit home.

“The Repentant Thief” by Deborah Swift stars an Irish immigrant boy in 1645 Edinburgh who steals a coin and locket from a tenement he’s broken into and then, as plague spreads, worries he’s brought God’s wrath down on his family. Historical atmosphere, well-wrought characters, realistic dialogue, pertinent themes, and a great ending: they’re all here.

Demonstrating the state of health care at the time, Katherine Pym’s “Arrows that Fly in the Dark” takes the perspective of time-traveling youths who inhabit the bodies of a physician’s apprentices in 1665 London. They find their master’s techniques for protecting against plague distasteful and sometimes ridiculous.

Lastly, “778” by Melodie Winawer, a tale of regret and resilience, shows how the rapidly shifting political climate in 17th-century Mystras, Greece, affects everyone in a Turkish man’s household. The arrival of plague adds to the heightened tensions.

A wide-ranging, rich collection of human experiences, all contained in a collection of fewer than 200 pages. This was a personal purchase. Hope this post encourages others to check it out for themselves. You can watch the YouTube recording of the panel below.

Published on October 19, 2020 06:00

October 12, 2020

A Wild Winter Swan by Gregory Maguire, a fairy-tale sequel set in 1960s NYC

New York at Christmastime can be an enchanting place. With his newest literary fantasy, a sort-of sequel to Hans Christian Andersen's “Wild Swans” fairy tale set in the 1960s, Maguire adds new facets of wonder to this locale.

New York at Christmastime can be an enchanting place. With his newest literary fantasy, a sort-of sequel to Hans Christian Andersen's “Wild Swans” fairy tale set in the 1960s, Maguire adds new facets of wonder to this locale. Raised by her stern Italian grandparents, Laura Ciardi is a lonely fifteen-year-old recently expelled after retaliating against a school bully. Her main company is their cook, the delightful Mary Bernice, and two friendly workmen repairing the family brownstone before a big holiday feast.

There, Laura’s grandparents hope to entice their rich Irish brother-in-law into investing in her Nonno’s grocery, while Laura wants a guardian angel to rescue her from potential boarding school in Montreal. Appearing instead on the roof, one stormy night, is a dirty, bedraggled young man with a swan’s wing for an arm.

Hilarity and awkwardness ensue as Laura tries to care for him and build him another wing without anyone noticing. Sensitive portraits of generational conflict and coming-of-age intertwine with whimsy as Maguire touchingly shows how people invoke stories to help elucidate their complicated world.YA/General Interest: YAs will easily identify with Laura and her journey towards maturity while finding the fantasy elements intriguing.

A Wild Winter Swan was published last week by William Morrow/HarperCollins. I reviewed it for the 9/1/20 issue of Booklist (reprinted with permission). A number of Maguire's novels incorporate historical settings: Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister (17th-c Holland), Hiddensee (early 19th-c Germany), Mirror Mirror (16th-c Italy). It was a nice change to see an American setting used for this latest imaginative tale.

Published on October 12, 2020 15:30

October 7, 2020

How Research Drives Plot, an essay by Libby Fischer Hellman, author of the historical novel A Bend in the River

I'm very happy to have Libby Fischer Hellman here today with a guest post about the primary and secondary source research she undertook for her new novel, A Bend in the River, which is out today. She also includes many wonderful photographs from her trip to Vietnam. I enjoy novels that transport me to different places and am looking forward to reading her book. Hope you'll enjoy the insights in her post as much as I did.

~

How Research Drives PlotLibby Fischer Hellman

Novelists drive plot by developing conflicts, actions, and dialogue. But I’d add another element to the mix: research. Especially when the story has an historical angle. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve discovered an actual historical event, person, or situation that I’ve woven into my fiction. Indeed, that was the case in A Bend in the River, my new historical novel about two Vietnamese sisters struggling through the “American War” (the Vietnam War to us) in quite different ways.

Novelists drive plot by developing conflicts, actions, and dialogue. But I’d add another element to the mix: research. Especially when the story has an historical angle. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve discovered an actual historical event, person, or situation that I’ve woven into my fiction. Indeed, that was the case in A Bend in the River, my new historical novel about two Vietnamese sisters struggling through the “American War” (the Vietnam War to us) in quite different ways.

I divide my research into primary and secondary sources. Primary sources include what I see, people to whom I talk, and visual materials that include film, photographs, videos, speeches, or interviews. That might be the reason my historical novels are largely based on Twentieth Century events, a time during which visual materials proliferated. I am, or was, a filmmaker and video producer. Secondary sources are, of course, books, including fiction written about the time period, documents, interview transcripts, articles, and historiography about the period. In both types of research, I found some fascinating nuggets that I included in Bend.

Primary Research

I was lucky enough to go to Vietnam for three weeks. Our trip included five days in Hanoi, another five in Saigon, and a river cruise up the Mekong River to Cambodia and beyond. Along the way I talked with as many Vietnamese people as I could.

The Colonel and the Translator

One of my most curious interviews was in Hanoi where I had the opportunity to speak to a former Colonel in the North Vietnamese army. I wanted to get his perspective on the war and his most vivid memories. Our tour guide served as translator, and we wove through the maze of narrow back alleys of Hanoi on his motor scooter to a ramshackle shack sandwiched between others.

The first thing I noticed was a photo of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin on the wall of his tiny parlor. The second was the fact that he was wearing his army jacket, adorned with patches and medals. Even after fifty years, in a country that embraces rapid growth and (dare I say it) capitalism, the colonel was still a committed Communist. I found that fascinating! I recorded the interview on my iPhone and asked all sorts of questions, to which the colonel made long responses in Vietnamese. However, my translator synthesized his comments into short ten second summaries. I was surprised he could do that so succinctly but didn’t say anything.

When I got home, I had the recording translated by a bilingual Vietnamese student. She emailed me with her concern: Apparently my translator was not relaying to me what the colonel had said. The Colonel’s answers to my questions were being filtered and adulterated through our guide who worked, of course, for the Communist government, and he had “interpreted” questions in a way that was acceptable either to the government, or western tourists, or both.

That told me, after the fact, that anything and everything said by Vietnamese citizens was monitored carefully and that true freedom of expression is an illusion. It was a cautionary lesson and one that I remembered when I interviewed other people back in the US.

Refugee Silence

In fact, it was probably that very circumstance that made it difficult to find Vietnamese-Americans who would talk to me back when I came home. I was looking specifically for “Boat People” who had escaped Vietnam—legally or not—by ship, boat, barge, or another vessel. But one after another declined to talk. I understood. Even after forty years, many refugees still fear that what they say might cause harm from either the US or the Vietnamese government. Or maybe they just want to forget. Happily, I eventually found one woman who agreed to talk and even allowed me to use her name in the acknowledgements.

The Mekong River

Our journey up the river was the heart of my trip. We stopped at villages where the wealthiest people in the village were the sampan maker, or the woman making non-las, the conical hats.

A family business where everyone helped out making rice candy, from cooking the rice, to adding the ingredients, to boxing and preparing it for distribution. Other villages boasted a wet market, or a Catholic church and school (the result of missionary work from prior decades), or small farms.

These were fascinating “slices of life,” and all the photos I took helped me create a sense of place. Of course, the people we saw were pre-selected by our tour operators, and undoubtedly had been cleared by the government. Still, the explosion of sights, sounds, and particularly smells, for example at the Binh Tay market in Saigon, were unforgettable. So were unplanned events like cockfights and school children flocking around us.

Cu Chi Tunnels

Perhaps the most consequential site I visited were the Cu Chi Tunnels outside Saigon. Two hundred kilometers of tunnels originally built by the French but upgraded and expanded by the North, the tunnels, not far from the southern tip of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, became the major transit route between North Vietnam and the Saigon area.

North Vietnamese fighters often lived in the tunnels for weeks. I spent hours at the tunnels, exploring them carefully, as they became an indispensable element of my plot.

Secondary Sources

In Stanley Karnow’s exceptional Vietnam: A History is a discussion about a female Vietnamese pediatrician who was in the inner circle of the Diem administration in the early Sixties. She was also a committed Communist and spied for the North. After the war, she renounced Communism, but she was not penalized by either the South or the North. I found her to be such a mysterious, absorbing person, that I fictionalized her as Dr. Đường Châu Hằng, a major character who recruited for the Viet Cong and also was a double agent in my book.

Part of A Bend in The River references the Cao Dai religion. Knowing nothing about it, I researched it online and read several articles about its history. The center of Cao Daism is in a city in which one of my characters spends quite a bit of time, so I gave that character a job in the kitchen of the temple campus where she spies on specific Cao Dai clergymen who might be aiding the South surreptitiously.

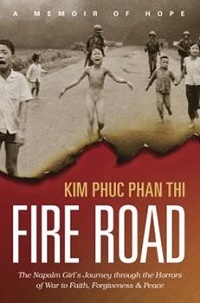

In the middle of writing Bend, a book called Fire Road was published. Its author, Kim Phuc Phan Thi, was the little girl who appeared in many photos at the time. She had been burned by a napalm attack and was naked, running down the road while screaming. Now in her fifties, the author came to Chicago; I met her and bought her book. While she is not directly part of my novel, her story gave me information about Vietnamese responses to American attacks and how profound those consequences could become.

In the middle of writing Bend, a book called Fire Road was published. Its author, Kim Phuc Phan Thi, was the little girl who appeared in many photos at the time. She had been burned by a napalm attack and was naked, running down the road while screaming. Now in her fifties, the author came to Chicago; I met her and bought her book. While she is not directly part of my novel, her story gave me information about Vietnamese responses to American attacks and how profound those consequences could become.

Finally, I found a series of interviews with girls who worked in Saigon GI bars during the Sixties (Maclean’s, 1968). Since one of my characters does exactly that, the articles were the pot of gold I’d been hoping to find. Again, my preconceptions were wrong. Most of the girls loved their jobs and felt liberated for the first time in their lives. They found American GIs courteous and respectful, as well as great tippers. They did not want to settle down with Vietnamese men.

This is not the first time that my research opened up possibilities for plot development, but it is the first time I found so many opportunities to weave history into the story. Each time I find a nugget that works, it’s immensely satisfying. For me it’s a way to keep history alive and fresh; for readers, I hope it whets their appetite for more.

~

More about A Bend in the River by Libby Fischer Hellmann

(The Red Herrings Press, on-sale October 7, 2020)

In 1968 two young Vietnamese sisters flee to Saigon after their village on the Mekong River is attacked by American forces and burned to the ground. The only survivors of the brutal massacre that killed their family, the sisters struggle to survive but become estranged, separated by sharply different choices and ideologies. Mai ekes out a living as a GI bar girl, but Tâm’s anger festers, and she heads into jungle terrain to fight with the Viet Cong. For nearly ten years, neither sister knows if the other is alive. Do they both survive the war? And if they do, can they mend their fractured relationship? Or are the wounds from the paths they took too deep to heal? In a stunning departure from her crime thrillers, Libby Fischer Hellmann delves into a universal story about survival, family, and the consequences of war.

About the Author

Libby Fischer Hellmann left a career in broadcast news in Washington, DC and moved to Chicago over 35 years ago, where she, naturally, began to write gritty crime fiction. Many novels and short stories later, she claims they'll take her out of the Windy City feet first.

She has been nominated for many awards in the mystery and crime writing community and has even won a few. She has been a finalist twice for the Anthony and three times for Foreword Magazine's Book of the Year. She has also been nominated for the Agatha, the Shamus, the Daphne, and has won the IPPY and the Readers' Choice Award multiple times. Libby hosts both a TV interview show and conducts writing workshops at libraries and other venues. She was the national president of Sisters In Crime, a 3500-member organization dedicated to the advancement of female crime fiction authors. Her books have been translated into Spanish, German, Italian, and Chinese. All her books are available in print, e-book, and audiobook formats. More information can be found online at libbyhellmann.com.

~

How Research Drives PlotLibby Fischer Hellman

Novelists drive plot by developing conflicts, actions, and dialogue. But I’d add another element to the mix: research. Especially when the story has an historical angle. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve discovered an actual historical event, person, or situation that I’ve woven into my fiction. Indeed, that was the case in A Bend in the River, my new historical novel about two Vietnamese sisters struggling through the “American War” (the Vietnam War to us) in quite different ways.

Novelists drive plot by developing conflicts, actions, and dialogue. But I’d add another element to the mix: research. Especially when the story has an historical angle. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve discovered an actual historical event, person, or situation that I’ve woven into my fiction. Indeed, that was the case in A Bend in the River, my new historical novel about two Vietnamese sisters struggling through the “American War” (the Vietnam War to us) in quite different ways. I divide my research into primary and secondary sources. Primary sources include what I see, people to whom I talk, and visual materials that include film, photographs, videos, speeches, or interviews. That might be the reason my historical novels are largely based on Twentieth Century events, a time during which visual materials proliferated. I am, or was, a filmmaker and video producer. Secondary sources are, of course, books, including fiction written about the time period, documents, interview transcripts, articles, and historiography about the period. In both types of research, I found some fascinating nuggets that I included in Bend.

Primary Research

I was lucky enough to go to Vietnam for three weeks. Our trip included five days in Hanoi, another five in Saigon, and a river cruise up the Mekong River to Cambodia and beyond. Along the way I talked with as many Vietnamese people as I could.

The Colonel and the Translator

One of my most curious interviews was in Hanoi where I had the opportunity to speak to a former Colonel in the North Vietnamese army. I wanted to get his perspective on the war and his most vivid memories. Our tour guide served as translator, and we wove through the maze of narrow back alleys of Hanoi on his motor scooter to a ramshackle shack sandwiched between others.

The first thing I noticed was a photo of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin on the wall of his tiny parlor. The second was the fact that he was wearing his army jacket, adorned with patches and medals. Even after fifty years, in a country that embraces rapid growth and (dare I say it) capitalism, the colonel was still a committed Communist. I found that fascinating! I recorded the interview on my iPhone and asked all sorts of questions, to which the colonel made long responses in Vietnamese. However, my translator synthesized his comments into short ten second summaries. I was surprised he could do that so succinctly but didn’t say anything.

When I got home, I had the recording translated by a bilingual Vietnamese student. She emailed me with her concern: Apparently my translator was not relaying to me what the colonel had said. The Colonel’s answers to my questions were being filtered and adulterated through our guide who worked, of course, for the Communist government, and he had “interpreted” questions in a way that was acceptable either to the government, or western tourists, or both.

That told me, after the fact, that anything and everything said by Vietnamese citizens was monitored carefully and that true freedom of expression is an illusion. It was a cautionary lesson and one that I remembered when I interviewed other people back in the US.

Refugee Silence

In fact, it was probably that very circumstance that made it difficult to find Vietnamese-Americans who would talk to me back when I came home. I was looking specifically for “Boat People” who had escaped Vietnam—legally or not—by ship, boat, barge, or another vessel. But one after another declined to talk. I understood. Even after forty years, many refugees still fear that what they say might cause harm from either the US or the Vietnamese government. Or maybe they just want to forget. Happily, I eventually found one woman who agreed to talk and even allowed me to use her name in the acknowledgements.

The Mekong River

Our journey up the river was the heart of my trip. We stopped at villages where the wealthiest people in the village were the sampan maker, or the woman making non-las, the conical hats.

A family business where everyone helped out making rice candy, from cooking the rice, to adding the ingredients, to boxing and preparing it for distribution. Other villages boasted a wet market, or a Catholic church and school (the result of missionary work from prior decades), or small farms.

These were fascinating “slices of life,” and all the photos I took helped me create a sense of place. Of course, the people we saw were pre-selected by our tour operators, and undoubtedly had been cleared by the government. Still, the explosion of sights, sounds, and particularly smells, for example at the Binh Tay market in Saigon, were unforgettable. So were unplanned events like cockfights and school children flocking around us.

Cu Chi Tunnels

Perhaps the most consequential site I visited were the Cu Chi Tunnels outside Saigon. Two hundred kilometers of tunnels originally built by the French but upgraded and expanded by the North, the tunnels, not far from the southern tip of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, became the major transit route between North Vietnam and the Saigon area.

North Vietnamese fighters often lived in the tunnels for weeks. I spent hours at the tunnels, exploring them carefully, as they became an indispensable element of my plot.

Secondary Sources

In Stanley Karnow’s exceptional Vietnam: A History is a discussion about a female Vietnamese pediatrician who was in the inner circle of the Diem administration in the early Sixties. She was also a committed Communist and spied for the North. After the war, she renounced Communism, but she was not penalized by either the South or the North. I found her to be such a mysterious, absorbing person, that I fictionalized her as Dr. Đường Châu Hằng, a major character who recruited for the Viet Cong and also was a double agent in my book.

Part of A Bend in The River references the Cao Dai religion. Knowing nothing about it, I researched it online and read several articles about its history. The center of Cao Daism is in a city in which one of my characters spends quite a bit of time, so I gave that character a job in the kitchen of the temple campus where she spies on specific Cao Dai clergymen who might be aiding the South surreptitiously.

In the middle of writing Bend, a book called Fire Road was published. Its author, Kim Phuc Phan Thi, was the little girl who appeared in many photos at the time. She had been burned by a napalm attack and was naked, running down the road while screaming. Now in her fifties, the author came to Chicago; I met her and bought her book. While she is not directly part of my novel, her story gave me information about Vietnamese responses to American attacks and how profound those consequences could become.

In the middle of writing Bend, a book called Fire Road was published. Its author, Kim Phuc Phan Thi, was the little girl who appeared in many photos at the time. She had been burned by a napalm attack and was naked, running down the road while screaming. Now in her fifties, the author came to Chicago; I met her and bought her book. While she is not directly part of my novel, her story gave me information about Vietnamese responses to American attacks and how profound those consequences could become. Finally, I found a series of interviews with girls who worked in Saigon GI bars during the Sixties (Maclean’s, 1968). Since one of my characters does exactly that, the articles were the pot of gold I’d been hoping to find. Again, my preconceptions were wrong. Most of the girls loved their jobs and felt liberated for the first time in their lives. They found American GIs courteous and respectful, as well as great tippers. They did not want to settle down with Vietnamese men.

This is not the first time that my research opened up possibilities for plot development, but it is the first time I found so many opportunities to weave history into the story. Each time I find a nugget that works, it’s immensely satisfying. For me it’s a way to keep history alive and fresh; for readers, I hope it whets their appetite for more.

~

More about A Bend in the River by Libby Fischer Hellmann

(The Red Herrings Press, on-sale October 7, 2020)

In 1968 two young Vietnamese sisters flee to Saigon after their village on the Mekong River is attacked by American forces and burned to the ground. The only survivors of the brutal massacre that killed their family, the sisters struggle to survive but become estranged, separated by sharply different choices and ideologies. Mai ekes out a living as a GI bar girl, but Tâm’s anger festers, and she heads into jungle terrain to fight with the Viet Cong. For nearly ten years, neither sister knows if the other is alive. Do they both survive the war? And if they do, can they mend their fractured relationship? Or are the wounds from the paths they took too deep to heal? In a stunning departure from her crime thrillers, Libby Fischer Hellmann delves into a universal story about survival, family, and the consequences of war.

About the Author

Libby Fischer Hellmann left a career in broadcast news in Washington, DC and moved to Chicago over 35 years ago, where she, naturally, began to write gritty crime fiction. Many novels and short stories later, she claims they'll take her out of the Windy City feet first.

She has been nominated for many awards in the mystery and crime writing community and has even won a few. She has been a finalist twice for the Anthony and three times for Foreword Magazine's Book of the Year. She has also been nominated for the Agatha, the Shamus, the Daphne, and has won the IPPY and the Readers' Choice Award multiple times. Libby hosts both a TV interview show and conducts writing workshops at libraries and other venues. She was the national president of Sisters In Crime, a 3500-member organization dedicated to the advancement of female crime fiction authors. Her books have been translated into Spanish, German, Italian, and Chinese. All her books are available in print, e-book, and audiobook formats. More information can be found online at libbyhellmann.com.

Published on October 07, 2020 04:30

October 3, 2020

The Dark Horizon by Liz Harris, a saga set between the two world wars in England and America

Spanning the post-WWI period through the Great Depression in England and America, Harris delivers an addictive saga reminiscent of early Barbara Taylor Bradford. The story follows the romance between two young people from different worlds and its dramatic fallout.

Spanning the post-WWI period through the Great Depression in England and America, Harris delivers an addictive saga reminiscent of early Barbara Taylor Bradford. The story follows the romance between two young people from different worlds and its dramatic fallout. Lily Brown had met Robert Linford when she was a land girl working near his family’s Oxfordshire estate. Enraptured with one another, they marry and have a son, James, but Joseph Linford, the intimidating and stubborn family patriarch, schemes to split them up, since he thinks Lily is inappropriate wife material and only after Robert’s money.

Joseph is a villain with depth. As head of Linford & Sons, he oversees a company building new housing developments on London’s outskirts and knows that Robert, his son and future successor, will need a partner who bolsters his social position. While beautiful Lily is a devoted wife and mother, it’s true that her naivete, lack of education, and the resulting anxiety hold her back. After Robert and Lily are driven apart and forced to rebuild their lives separately, it leaves a question open about whether they will ever reunite, and how, especially with both unaware of the deceit underlying their split.

The novel journeys along with their well-developed coming-of-age stories, told in parallel, as they form ties with others that help them grow in confidence. The backdrop of early 20th-century Hampstead, a community in north London, is an original setting, and the Jewish tenements of New York’s Lower East Side are vibrantly animated.

The story zips along with emotional currents that make the book hard to put down. Harris also manages to navigate a path through a complicated plot maze at the end, wrapping up her tale in a satisfying manner while leaving room for future volumes in the Linford Saga.

The Dark Horizon was published by Heywood Press in 2020; I reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review and will be reviewing the next book, The Flame Within, next month. The next book will focus on Alice, the wife of Thomas Linford, who plays a secondary role here.

Published on October 03, 2020 13:57

September 29, 2020

Receive Me Falling by Erika Robuck, a haunting multi-period Caribbean mystery

Being home so much during the pandemic has given me time to catch up with novels I’d purchased a long time ago. Erika Robuck’s Receive Me Falling is her first, self-published novel, which came out in 2009, and I’ve had it on my shelf for about that long. If you haven’t read it before, now’s a choice time to pick it up, since its setting and themes are especially timely with the craze for all things Hamilton and the current #BlackLivesMatter movement.

Being home so much during the pandemic has given me time to catch up with novels I’d purchased a long time ago. Erika Robuck’s Receive Me Falling is her first, self-published novel, which came out in 2009, and I’ve had it on my shelf for about that long. If you haven’t read it before, now’s a choice time to pick it up, since its setting and themes are especially timely with the craze for all things Hamilton and the current #BlackLivesMatter movement. Skillfully jumping between the present day and the 1830s, using the popular dual-narrative format, Robuck zooms in on a sugar cane plantation, Eden, on the Caribbean island of Nevis (Alexander Hamilton’s birthplace) and its haunted history.

Meg Owen, a 33-year-old woman who works for Maryland’s controversial governor, is distraught when her parents die in a car crash the night after her engagement party. One of the properties they owned was an old plantation house on Nevis, and to clear her head, Meg travels to see her inheritance for herself. After she learns the shocking true state of her father’s financial affairs, finding the right buyer for the house and land becomes pressing.

Nearly two hundred years earlier, Catherine Dall lives with her alcoholic father, Cecil, at Eden, and oversees its sugar cane production, an operation dependent on the labor of over 200 enslaved people. Catherine believes herself to be a kind mistress and proves receptive to opinions shared by two British visitors, a father and son, who are pretending to be scoping out a site for a plantation of their own while secretly laying the groundwork for the abolitionist movement.

With its turquoise waters, cool sea breezes, and many varieties of colorful flowers filling the landscape, Nevis would be an idyllic paradise – if not for knowledge of its former residents’ slave-owning past. Meg has the option to sell to a developer who would transform the now-decrepit estate into a plantation-style resort, and she needs the money, but she finds that idea insensitive and distasteful. Catherine, meanwhile, is a wealthy young woman whose outlook reflects her time. While she may personally dislike slavery and is horrified by the actions taken by her father’s stereotypically cruel overseer, her lifestyle is so ingrained in the system that she’s unable to see a way out of it.

It’s up to Meg to sift through old artifacts and uncover, with the help of a local historian, what factors contributed to Eden’s downfall so long ago. As is rarely the case with multi-period novels, I found the modern narrative grabbed me the most, with its emphasis on sifting through the remnants of the past and its refreshingly non-standard romantic subplot.

Published on September 29, 2020 14:10

September 24, 2020

Review of The Queen of Tuesday: A Lucille Ball Story, by Darin Strauss

The premise of Strauss’s newest literary novel is grandiose and rather wacky: that his grandfather Isidore Strauss, a Long Island real estate developer, had a secret affair with Lucille Ball. This never happened. The author describes his work as “a hybrid: half memoir and half make-believe” sparked by “an innocent dream,” although Isidore and the actress did attend the same party in which Fred Trump demolished the glass Pavilion of Fun on Coney Island.

The premise of Strauss’s newest literary novel is grandiose and rather wacky: that his grandfather Isidore Strauss, a Long Island real estate developer, had a secret affair with Lucille Ball. This never happened. The author describes his work as “a hybrid: half memoir and half make-believe” sparked by “an innocent dream,” although Isidore and the actress did attend the same party in which Fred Trump demolished the glass Pavilion of Fun on Coney Island. Their imagined meeting there, moved to 1949 from its real 1966 occurrence, opens the story. Lucille, a former B-Movie queen, has ambitious plans for television; Isidore, a handsome Jewish man with a “Cary Grant chin,” is a better listener (and lover) than the actress’s hot-tempered, unfaithful husband.

The novel follows the pair – her overnight superstardom, his struggle to maintain normality amid their romance, their progressively strained marriages – mostly separately. In between, using metafiction techniques, the author describes his grandfather’s life and his own attempts to interest his (real) agent in a screenplay Isidore and Lucille co-wrote (obviously fictional).

The tale succeeds in entertaining, and Lucille steals the show, of course. Most moving are the scenes where she finds her comedic niche via the character of Lucy Ricardo: “Maybe she can be the audience, only funnier and a little prettier… She can conquer the world with realness.” Strauss also offers insight into celebrity culture and the difficult interplay between Lucille’s on-screen and off-screen marriages, both involving Desi Arnaz.

So much even beyond the central conceit is made up, however, that it pushes the novel into the alternate history spectrum. Even the weekday when I Love Lucy aired is off-kilter (it was Mondays, not Tuesdays). It’s best for people who value emotional over historical truth, but all the same, it should spur interest in Lucille Ball and her accomplishments.

The Queen of Tuesday was published in August by Random House (I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review). I'd love to know what historical fiction readers besides me think about this premise, and about the book if you've read it. Would you consider reading it?

Published on September 24, 2020 07:00