Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 37

February 2, 2021

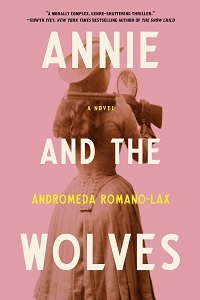

Interview with author Andromeda Romano-Lax about Annie and the Wolves

A dozen years ago, I posted an interview with Andromeda Romano-Lax about her debut novel, The Spanish Bow. We recently reconnected, and I jumped at the chance to pose her some questions about her newest novel, Annie and the Wolves, which is out today.

A dozen years ago, I posted an interview with Andromeda Romano-Lax about her debut novel, The Spanish Bow. We recently reconnected, and I jumped at the chance to pose her some questions about her newest novel, Annie and the Wolves, which is out today. Annie and the Wolves follows the intertwining stories of Annie Oakley, the famous American sharpshooter, and Ruth McClintock, a contemporary historian struggling to prove her hypothesis that choices Annie made later in life were motivated by childhood abuse. After Ruth is sent some writings purporting to be Annie's personal journal, it sets her on a path to learning the truth not only about Annie's past but also about unsolved mysteries and odd phenomena from Ruth's own personal life.

This isn't your standard dual-time novel about historical research and discoveries, but a multi-stranded thriller about the dawn of psychotherapy, the path to overcoming trauma, women's empowerment, and the tantalizing possibilities of time-travel. It left me thinking about uncanny real-life coincidences and how history itself is formed. Hope this intrigues you, and hope you'll enjoy this interview with Andromeda about her amazing genre-defying book.

The novel delves into Annie Oakley’s impoverished, difficult youth and her middle years, from the time of her train accident going forward. How did you get interested in these less well-known aspects of her life?

Discovering that Annie was essentially held captive for two years as a child by a farm couple called “The Wolves” was my starting point for the novel—along with the fact that, simultaneously, I was mulling over issues of abuse in my own family. (My sisters were abused by my father, who died around the same time I stumbled on the historical footnote that led me to Annie’s story.) There’s no question that I sublimated my concern for my sisters—and even my survivor’s guilt, as the youngest, least-affected child—into the work of finding a way to tell Annie’s story, which is ultimately an uplifting one.

From those first intertwining inspirations, I went on to learn more about the head-on train collision Annie Oakley survived in 1901, and about her legal battle with William Randolph Hearst, who libeled her in print. That middle-aged period isn’t unknown but documentation is spotty, which leaves the novelist plenty of room for invention.

I should make clear that the historical record was just a jumping-off point. From a few basic facts—childhood abuse, mid-life problems and injury—I built up a fictional premise: that Annie Oakley was disturbed by a yearning for revenge against her abusers, and that she sought a type of counseling, talk therapy, that happened to be developing in Vienna during that same era. Especially given that Annie Oakley was comfortable traveling to Europe, including Vienna (where she was much admired), I found that coincidence intriguing and used it to create a plot that is rooted in possibility but completely fanciful in its dramatized form.

The dynamic between Ruth, a researcher in her early 30s, and the tech-savvy high-school student, Reece, was an especially enjoyable part of the book. It’s like they become partners in solving multiple mysteries that other people are determined to ignore. What inspired them and their unusual relationship?

I’m glad you like Reece! I didn’t want Ruth to go it alone, and as I invented him, I came to realize—as I think Ruth does—that he could be a stand-in for the relationship she never managed to have with her troubled younger sister, Kennidy. With Reece, Ruth learns to communicate more openly, to ask for help, to risk being uncomfortable, and to care. This is a book that fully spans one-hundred and fifty years, and I wanted Reece to be our touchpoint for today: a smart, extroverted, probably non-binary (I don’t spell it out) teenager with his own artistic interests and problems. One early reader questioned how mature he is, but I’m a mom of twenty-somethings and they and their friends were just as assertive, quirky and smart as Reece when they were his age.

author Andromeda Romano-LaxThe novel imagines that Annie Oakley sought help from a psychoanalyst, and re-creates evidence of their communications. How did you go about creating these writings?

author Andromeda Romano-LaxThe novel imagines that Annie Oakley sought help from a psychoanalyst, and re-creates evidence of their communications. How did you go about creating these writings? It’s funny how once you create a fictional world it can seem inevitable and real—at least to the author, and hopefully to some readers! At one point while researching and pondering how Annie Oakley would have dealt with her trauma (especially given that she was a celebrity and couldn’t risk letting the world see her as weak), I was also reading about Anna O., the famous analysand who was treated by Josef Breuer and written about in a book by Breuer and Freud. (Readers often confuse the two men.) I thought, “A.O. and A.O.—that’s weird.” My brain got that same “everything-is-connected” feeling that frequently overwhelms Ruth.

The fact that the Annie of my novel is saddled with memories of childhood abuse in the same era that psychoanalysis (with an emphasis on recall of childhood traumatic events) was being developed seemed too interesting a coincidence to pass up. If she was going to talk to someone about it, why not the Viennese doctor who first wrote about talk therapy? From there, I knew they’d have to communicate only once in person and thereafter by letter, because Annie would need to be back in America to deal with the ongoing Hearst trials—which were, again, a biographical reality. Then it was left to me to invent those letters, as well as the original mystery journal that opens the book.

The concept of time-travel is always fun to explore, since it lets us ponder what would happen if the past could be physically reached and changed. I enjoy the speculative aspects of these novels as they relate to history, and how authors depict how it all works. What attracted you to the concept? Do you think it’s important in fiction for time-travel to have rules?

Yes, time travel absolutely must have rules. (And what a challenge they can be to invent and explain!) I never expected to write a time travel novel—and in fact avoided any speculative or fantasy element in early drafts. But when it comes to exploring not only history, but trauma, time travel becomes both a logical mechanism and a larger metaphor. When I was doing my initial research on time travel, I kept stumbling across psychological research papers that use the term mental “time travel” simply to mean reconstructing personal events in the past. Well, we all do that. People with PTSD do it even more intensely. As for changing the past, that’s the question, isn’t it? If one could, should one? And if one can’t or shouldn’t, what does that say about our orientation to the past and future at the expense of the present? I think time travel plots will remain timeless—no pun intended—because they fulfill our desire to imagine changing the past while also allowing us to ponder ancient questions of destiny and free will.

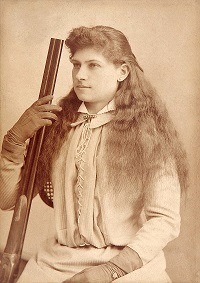

Annie Oakley in the 1880sThe story is amazingly creative and multifaceted, with so many different subplots – I read along with great interest in seeing how they would all come together. What skills or tools as a writer did you draw on to keep track of everything going on?

Annie Oakley in the 1880sThe story is amazingly creative and multifaceted, with so many different subplots – I read along with great interest in seeing how they would all come together. What skills or tools as a writer did you draw on to keep track of everything going on? I wish I had a better answer for you. I keep some thinking and planning notes in a journal, but I mostly discover as I write and do ongoing research, then revise to make things clearer or when a new lightbulb goes on, over my head. (For example: “Of course that’s who the antiques seller is! Why didn’t I know that from the beginning?”)

What lessons can modern readers take away from Annie’s life story?

The fictional Annie of my novel and the real Annie Oakley—the biographical one, who is so much more impressive than the “Annie Get Your Gun” character from musicals and movies—has so much to teach us. The real Annie rescued herself, saved her family from poverty and ruin thanks to her small-game-hunting abilities, crafted a unique role as a world-famous sharpshooter and performer, made a good living, protected her brand, confronted her enemies (like Hearst, in court), and thrived with the support of a husband who supported her career. Having survived her own childhood and her especially dark years with the Wolves, she committed to helping others, which included training women in self defense and financially supporting girls and orphans. My novel supposes—and I’d like to believe it’s true—that helping other girls and women was what gave Annie the strength to endure the trials of her later years and achieve a sense of peace.

~

Annie and the Wolves was published by Soho Press; thanks to the publisher for granting me access via NetGalley. For more information, please visit the author's website at https://www.romanolax.com.

Published on February 02, 2021 06:00

January 29, 2021

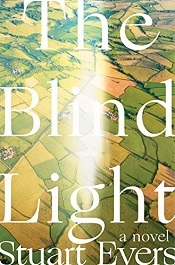

The Blind Light by Stuart Evers, a British family saga of the nuclear age

Doom Town is the catchy yet grim nickname for a real site in Cumbria, England, used for simulating the aftermath of a nuclear strike. In Evers’ spacious and unusual saga, Drummond “Drum” Moore and Jim Carter run training rescue missions there in 1959 for their National Service, an experience that shakes them deeply and casts a shadow on their families henceforth.

Doom Town is the catchy yet grim nickname for a real site in Cumbria, England, used for simulating the aftermath of a nuclear strike. In Evers’ spacious and unusual saga, Drummond “Drum” Moore and Jim Carter run training rescue missions there in 1959 for their National Service, an experience that shakes them deeply and casts a shadow on their families henceforth. Evers excels at depicting the men’s strong, identity-shaping bond, which doesn’t quite surmount their class differences. Following their military commitments, Drum works at a Ford factory in suburban London and raises two children with wife Gwen, a former barmaid, while the arrogant, posh Carter weds and lives in rural Cheshire. Years later, Carter persuades Drum to take over his neighbor’s farm, thus keeping Drum’s loved ones secluded and safe, but in doing so, Drum loses sight of other family problems.

The novel spans six decades, and the later generation’s stories aren’t as interesting, but the moody setting, rich in details reflecting social change in Britain, well suits this tale of lives eclipsed by fear.

Blind Light was published by WW Norton in October (I reviewed it for Booklist's 9/1 issue; reprinted with permission). Some other notes:

I've seen reviews that call "Doom Town" a fictional location, but it was a real site, located at Millom Airfield in Cumbria. You can see a 1-minute video showing training missions there, as part of the British Pathé collections (the clip dates from 1955). As the video mentions, and as the novel depicts, many men did a stint there at the end of their National Service, "learning all there is to know about rescue methods in the atomic age."

Published on January 29, 2021 14:10

January 24, 2021

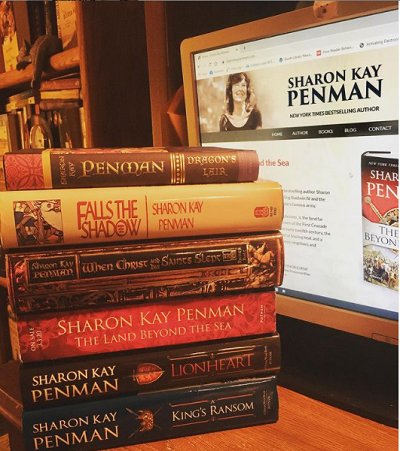

In remembrance of historical novelist Sharon Kay Penman

The historical fiction community is in mourning following the loss of one of the great authors in our genre, Sharon Kay Penman, on Friday. I'd written up a short post for my Instagram at that time and thought I'd expand upon my reflections here. The outpourings of sorrow and memorials I've been seeing on social media since her passing have been enormous; she was a good friend and supporter of numerous historical novelists and a longtime cherished author of many more readers.

Sharon Kay Penman has been a favorite author of mine ever since I read The Sunne in Splendour, her masterwork about Richard III, when I was in middle school. It came out in 1992, and it was one of the first "adult" historical novels I'd read, along with Anya Seton's Katherine. I also remember carrying the heavy hardcover of When Christ and His Saints Slept along with me on the plane to the campus interview for my first library job, since I was in the middle of reading and didn't want to leave the story behind. Most recently, I had the privilege of reviewing her latest, The Land Beyond the Sea, focusing on the 12th-century Kingdom of Jerusalem, for Booklist.

Ten of her novels are deeply researched epics (massive tomes, which you can see from the book pile above) that brought the prominent personalities from the Middle Ages, especially England's ruling Plantagenet family and their close relatives, to amazing life. If I had to pick a favorite, it would be Here Be Dragons, about the marriage between King John's illegitimate daughter, Joanna, and Llewelyn "the Great" of Wales in the 13th century. Like Maria Comnena in The Land Beyond the Sea, Joanna was a fascinating protagonist whose story hadn't previously been told in fiction, and who I was glad to get to know. Sharon introduced her readers to the vivid landscapes and castles of medieval England and Wales and the complex relationships among the family members who ruled there.

Sharon also wrote four mysteries featuring sleuth Justin de Quincy in Eleanor of Aquitaine's time, starting with The Queen's Man. These are shorter novels, but also assiduously researched. Reading the detailed author's notes at the end of her novels are a pleasure in themselves. The one for The Land Beyond the Sea runs for eight pages.

Although I didn't really know her personally, I enjoyed hearing from her on Facebook (she was friends there with many of her readers) and via her blog, where she interviewed other novelists and spoke about her research. I was glad for the opportunity to exchange emails with and meet Sharon when the Historical Novel Society conference committee invited her to be a guest of honor for our 2009 conference in Schaumburg, Illinois – and she returned to take part in later conferences. She leaves a wonderful legacy of stories for readers to discover and return to.

Published on January 24, 2021 06:32

January 21, 2021

The Gates of Athens by Conn Iggulden recounts ten pivotal years in ancient Greek history

This rousing series opener brings ten pivotal years in ancient Greek history to energetic life. Spanning from the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE to the Spartans’ valiant stand at the Battle of Thermopylae, the story moves nimbly among the perspectives of Athenian leaders, primarily the politician and general Xanthippus, plus their allies and Persian foes.

This rousing series opener brings ten pivotal years in ancient Greek history to energetic life. Spanning from the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE to the Spartans’ valiant stand at the Battle of Thermopylae, the story moves nimbly among the perspectives of Athenian leaders, primarily the politician and general Xanthippus, plus their allies and Persian foes. A celebrated historical adventure writer, Iggulden (The Falcon of Sparta, 2019) illustrates both large-scale military maneuvers and minute details, from close-up views of bronze-armored Greek soldiers in formation to fearsome scenes of the immense Persian fleet, bent on destroying Athens.

The intervening decade between major battles in the ongoing Greco-Persian Wars holds equal fascination as Athens is shaken by infighting that divides its statesmen. These inner political workings are vividly personified via courageous, intelligent, well-rounded characters.

Iggulden has impressive command of period terminology and largely follows the historical record, filling in gaps with well-thought-out reasoning. This is also an inspiring read about the value of democracy, whose birthplace was classical Athens, and how people fought hard and long to preserve it for posterity.

The Gates of Athens was published in the US on January 5 by Pegasus, and I reviewed it for Booklist's Dec. 15th issue (reprinted with permission).

Other notes: This book was a revelation. Historical military adventure isn't normally my thing, but this novel is much more than that. It focuses on character development and theme as much as technical details and who-does-what-to-whom. Readers seeking nonstop action may be disappointed by the middle sections that delve into Athenian politics and how its policies were implemented, such as the process by which men could be forced into exile. Reading it as a PDF on my iPad turned out to be a great advantage, too, since for any unfamiliar terminology I encountered, I could highlight a term, and I had my choice of the Kindle's internal dictionary or Wikipedia for a definition. There was no glossary in my ARC. My appetite is whetted for book two.

Published on January 21, 2021 16:00

January 16, 2021

A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes, a women's retelling of the Trojan War

“Sing, Muse,” commands a poet, invoking inspiration for his Trojan War verse, but Calliope, goddess of epic poetry, has her own purpose in mind. She offers a tale not of men’s glory but the experiences of all the women. Except maybe Helen, who annoys her.

“Sing, Muse,” commands a poet, invoking inspiration for his Trojan War verse, but Calliope, goddess of epic poetry, has her own purpose in mind. She offers a tale not of men’s glory but the experiences of all the women. Except maybe Helen, who annoys her. Haynes tells a witty, unapologetically feminist story of women’s suffering, courage, and endurance, which demands that we reconsider our concept of heroism. Following a ten-year siege, Creusa, a young wife, wakes to see her city aflame, while other women of Troy wait along the shoreline to be parceled out as slaves to the Greek victors.

Showing Haynes’ comedic touch, Penelope writes letters to her husband, Odysseus, growing exasperated as she learns the reasons for his delayed voyage home to Ithaca. Some characters are familiar, others less so, including Oenone, Paris’s abandoned wife. Cassandra’s account is especially wrenching.

The telling is nonlinear, but the varied stories flow naturally together, ensuring readers won’t be lost. Grounded in the classics, this freshly modern version of an ancient tale is perfect for our times.

A Thousand Ships will be published on January 26th by Harper in the US. In the UK, the novel has been out for a while (2019) and was shortlisted for the 2020 Women's Prize for Fiction. I submitted this review for the December issue of Booklist. I'd read A Thousand Ships last October and began noticing the number of new and upcoming publications retelling ancient Greek myths from the women's viewpoint, spurred on by the success of Pat Barker's The Silence of the Girls and Madeline Miller's Circe. Look for a post about this soon! Haynes is also the author of The Children of Jocasta, fiction based on the stories of Sophocles' Oedipus and Antigone.

Published on January 16, 2021 06:57

January 11, 2021

Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms by Anita Heiss sees the WWII home front from the Indigenous Australian perspective

On August 5, 1944, hundreds of Japanese POWs in a compound on the outskirts of Cowra, a small town in central New South Wales, Australia, organized a mass breakout, driven by the shame brought on their families due to their captivity. With her historical novel using this pivotal event as a starting point, Anita Heiss imagines a gentle romance between an escaped Japanese soldier, Hiroshi, and Mary Williams, eldest daughter of an Aboriginal family that grants him refuge.

On August 5, 1944, hundreds of Japanese POWs in a compound on the outskirts of Cowra, a small town in central New South Wales, Australia, organized a mass breakout, driven by the shame brought on their families due to their captivity. With her historical novel using this pivotal event as a starting point, Anita Heiss imagines a gentle romance between an escaped Japanese soldier, Hiroshi, and Mary Williams, eldest daughter of an Aboriginal family that grants him refuge. Dr. Heiss, a member of the Wiradjuri nation, makes a unique contribution to WWII literature by depicting the Indigenous Australian perspective on the home front. She warmly depicts the interactions among the Williams family members, their friends, and neighbors, as well as the growing rapport between seventeen-year-old Mary and Hiroshi, who must spend long, lonely days concealed in an air raid shelter, his only respite being Mary’s visits with the meager rations she’s able to give him.

I found aspects of the love story somewhat far-fetched, but the couple’s ongoing dialogue enables the author to relate the characteristics of their substantially different cultures. Above ground, the story highlights the strength of the Williams parents, Banjo and Joan, who raise their family with dignity on Erambie Mission, knowing that white authorities won’t hesitate to take their children away if they’re found slacking on household cleanliness.

They take huge risks in sheltering Hiroshi but – not without some disagreement among them – choose to act out of human kindness, and with the knowledge that they and the Japanese are both fighting against the Australian government at the time. Forbidden to own their hereditary lands, Aboriginal people have their lives strictly controlled and aren’t able to vote – the people at Erambie have less freedom than even the Italian POWs working on farms nearby. The writing flows easily throughout this sensitively drawn story.

I read this from a personal copy. Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms was published by Simon & Schuster Australia in 2016. The novel may not be easy for non-Australians to find these days, but it's worth seeking out for its storyline, history, and viewpoint.

Published on January 11, 2021 05:30

January 4, 2021

The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly, a multi-period novel centered on an Edwardian garden

A country house in rural Warwickshire is the scene for Kelly’s touching, immersive read, which has definite appeal for aficionados of Downton Abbey and Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows’ The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008). Over a century, five distinctive women are connected through a historic Edwardian garden, each struggling in different ways between family and societal expectations and achieving their hearts’ desires.

A country house in rural Warwickshire is the scene for Kelly’s touching, immersive read, which has definite appeal for aficionados of Downton Abbey and Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows’ The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society (2008). Over a century, five distinctive women are connected through a historic Edwardian garden, each struggling in different ways between family and societal expectations and achieving their hearts’ desires. In 1907, Venetia Smith arrives to design an elaborate new garden for Highbury House’s wealthy residents. Decades later, the British home front comes alive through the tales of Highbury’s widowed young owner, her restless cook, and a neighboring land girl as the estate is requisitioned during wartime. Lastly, a contemporary designer uncovers mysteries while aiming to replicate Venetia Smith’s original plans.

Subplots involving love, loss, and hope for new beginnings gracefully intertwine, and readers will be enraptured by the garden theme, from the labor and artistic expression involved in their craftsmanship to the therapeutic power of nature’s beauty. Like gardens themselves, these pages invite lingering and thoughtful reflection.

The Last Garden in England is published by Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster on January 12th. I read it back in August last year and reviewed it for the 10/15/20 issue of Booklist from an Edelweiss e-copy. Isn't the cover beautiful?

Published on January 04, 2021 10:00

December 31, 2020

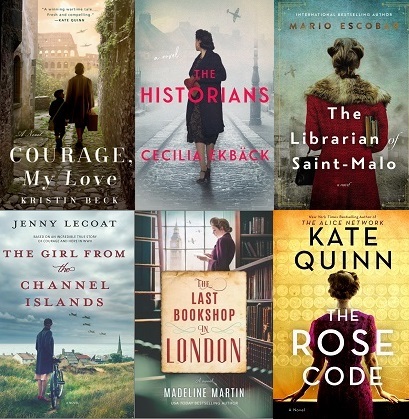

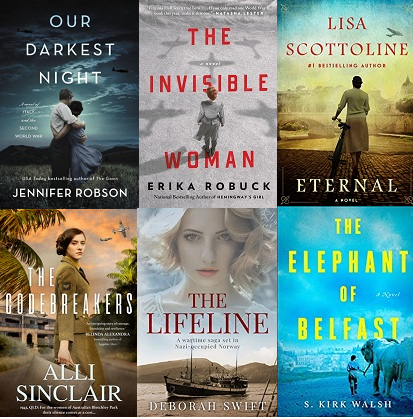

An abundance of upcoming WWII fiction for the first half of 2021

Since I'd posted earlier about historical novels not featuring WWII, I thought it only fair to include a gallery of forthcoming fiction set during this prominent era. All will be appearing in the first half of 2021. There are more where these came from; I selected a dozen out of personal interest and in an attempt to provide a variety of locales, without considering the cover designs. As it happens, many offer a similar look: women in period-appropriate garb (and seriously spiffy hairdos) with their back to the reader. Links go to the book's page on Goodreads.

Above we have a mix of debut novels and new releases from established historical novelists. Kristin Beck's Courage, My Love (Berkley, April) features two young Italian women who join the resistance during the Nazi occupation of Rome. The Historians (Harper Perennial, Jan.), from Swedish novelist Cecilia Ekbäck, is a conspiracy thriller set amidst tensions surrounding Sweden's neutral status in the war. Saint-Malo, a historic coastal town in Brittany, is the locale for Mario Escobar's The Librarian of Saint-Malo (Thomas Nelson, June). It reveals the love story between a librarian and her longtime sweetheart and her determination to protect the library's book collections during the war.

Another debut, The Girl from the Channel Islands by Jenny Lecoat (Graydon House, Jan.), called Hedy's War in the UK, centers on a young Jewish woman, a refugee from Vienna, and the daring choices she makes to survive the Nazi occupation of the island of Jersey. Madeline Martin's first mainstream historical, The Last Bookshop in London (Hanover Square, Apr.), another novel with obvious appeal for bibliophiles, evokes the value of stories in its tale of Grace Bennett, a bookshop employee in wartime London. The Rose Code by Kate Quinn (Berkley, Mar.), her followup to The Huntress, promises to be another twisty historical novel, this time surrounding three women involved in codebreaking activity at Bletchley Park. I visited Bletchley on vacation last year, back when we could still travel, so this novel is high on my TBR.

Canadian author Jennifer Robson writes that her newest book, Our Darkest Night (Morrow, Jan.) is based on true events; it focuses on a young Jewish woman from Venice who takes refuge with a former-seminarian-turned-farmer to escape the Holocaust. Virginia Hall, an American spy who worked with Britain's SOE during WWII, is the subject of Erika Robuck's biographical novel The Invisible Woman (Berkley, Feb.). Bestselling thriller writer Lisa Scottoline's first historical novel is Eternal (Putnam, Mar.), which centers on three friends as Mussolini comes to power in Italy; it promises a story of love, loss, and tested loyalties in the heart of Rome.

The Codebreakers by Alli Sinclair (MIRA Australia, Mar.) is about the women covertly working for the intelligence organization called the Central Bureau in 1943 Brisbane, cracking codes that may shift the course of WWII in the Pacific. Deborah Swift's newest romantic WWII saga, The Lifeline (Sapere, Jan.), takes place in Nazi-occupied Norway and deals with the covert seafaring operation known as the Shetland Bus. And the setting of S. Kirk Walsh's The Elephant of Belfast (Counterpoint, Apr.) should be obvious; the blurb reveals it's inspired by historical events and features a female zookeeper's bond with an elephant in the Belfast zoo during the Blitz.

This is my last post for this year, and I'll be glad to see 2020 gone. Thanks for reading my site, and I send my wishes for a peaceful 2021 and an upcoming year of great reading to everyone.

Published on December 31, 2020 08:00

December 27, 2020

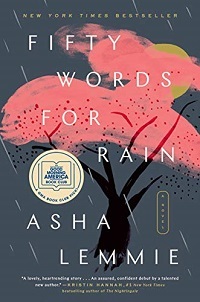

Fifty Words for Rain by Asha Lemmie, a dramatic coming-of-age novel set in post-WWII Japan

With her first novel, Asha Lemmie proves herself a talented writer unafraid to take chances. Her heroine’s situation is unique, and her journey to adulthood is one that won’t leave the mind quickly.

With her first novel, Asha Lemmie proves herself a talented writer unafraid to take chances. Her heroine’s situation is unique, and her journey to adulthood is one that won’t leave the mind quickly. Noriko “Nori” Kamiza is only eight when her beautiful mother brings her to her family home in Kyoto in 1948 and abandons her at the gates, making her promise to obey and keep silent. We soon learn why: Nori is illegitimate, the product of her aristocratic mother’s affair with a Black American GI, and her appearance and very existence are a deep source of shame.

For two years, Nori remains isolated in the mansion’s attic, cared for by her stern grandmother’s maid and educated well, but she’s subject to regular beatings and attempts to bleach her almond-colored skin. Her life changes when her teenage half-brother Akira arrives at the house to live after his father’s death.

The dynamic that forms between them – the beloved heir and the accursed bastard – is mesmerizing. After being hidden away for so long, Nori is hungry for attention but afraid to misstep. She worships Akira for easing her restrictions and standing up for her, which nobody has done before. For his part, Akira clearly cares for his little sister, but he’s a brilliant violinist with plans of his own; she isn’t his entire world, like he is hers.

This is literary fiction with many quotable lines and a cinematic, fast-moving plot. Nori’s path to maturity is unorthodox and beset by dramatic, often shocking shifts in circumstance. Nori is bright, curious, and – understandably – not in good control of her emotions. Readers may struggle with some of her choices. They also won’t fail to empathize with her as she learns self-acceptance, overcomes prejudice, and emerges as a powerful force of her own.

Fifty Words for Rain was published by Dutton in September (I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review). Its publication was moved up after it was chosen for the Good Morning America book club, and it subsequently became a NYT bestseller.

For background into the publication process, read Dutton editor Stephanie Kelly's article for the Penguin Random House website on acquiring historical fiction that moves readers.

Published on December 27, 2020 07:46

December 20, 2020

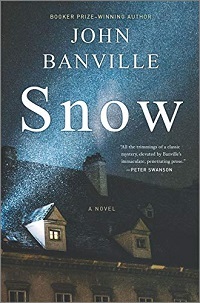

Snow by John Banville, a chilling historical mystery set in 1950s Ireland

Snow: cold, soft, brilliantly blinding. It muffles sound and casts a thick shroud over whatever lies beneath. The symbolism is apropos in Banville’s newest crime novel, the first to be written under his own name rather than the pseudonym (Benjamin Black) he’d established for genre-fiction purposes.

Snow: cold, soft, brilliantly blinding. It muffles sound and casts a thick shroud over whatever lies beneath. The symbolism is apropos in Banville’s newest crime novel, the first to be written under his own name rather than the pseudonym (Benjamin Black) he’d established for genre-fiction purposes. Snow takes place in County Wexford, Ireland, a time when the Catholic Church reigned supreme and buried its adversaries. One frigid day in 1957, Detective Inspector St. John (pronounced “Sinjun”) Strafford arrives at Ballyglass House to investigate a murder. The body of Father Tom Lawless, longtime friend of the Osborne family, lies on the floor of the ornate library, throat cut and private parts removed. A parish priest’s killing is bizarre enough on its own, and almost no one seems upset about it. Strafford shares the privileged Protestant background of the Osbornes but finds, to his annoyance, that this doesn’t gain him any ground in his sleuthing.

The story appears to follow a standard country-house mystery plot, with a closed-in setting and characters fitting familiar types: a refined patriarch, his attractive younger wife, their rebellious adult children. Banville peels away at these tropes as the personalities behind the theatrical parts make themselves known. Strafford is himself an intriguing figure, both in his career – most policemen in the Garda are Catholic – and in his reactions to the women he meets.

That said, he’s surprisingly slow on the uptake in pinpointing motive. An interlude late in the story, seen from Father Tom’s viewpoint, makes things clear for anyone who hasn’t yet figured it out. Banville has a consummate hand with establishing atmosphere, though, in sentences of chillingly ethereal beauty: “Surely such a violent act should leave something behind, a trace, a tremor in the air, like the hum that lingers when a bell stops tolling?”

Snow was published by Hanover Square Press in October; in the UK, Faber and Faber is the publisher. I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. This novel seemed apropos for this time of year in the US Midwest. This is my first time reading one of John Banville's (that is, Benjamin Black's) crime novels; if you've read others you'd recommend, please comment.

Published on December 20, 2020 07:15