Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 33

June 5, 2021

Eternal by Lisa Scottoline, her first historical novel, set in WWII-era Rome

Readers will emerge informed and moved from Lisa Scottoline’s first historical novel, which dramatizes WWII-era Rome via three best friends and their families. Known for her bestselling legal thrillers, Scottoline describes Eternal as “the book she was born to write.” Her passion shows in the carefully depicted setting and her compassion for her characters, whose ties are repeatedly tested.

Readers will emerge informed and moved from Lisa Scottoline’s first historical novel, which dramatizes WWII-era Rome via three best friends and their families. Known for her bestselling legal thrillers, Scottoline describes Eternal as “the book she was born to write.” Her passion shows in the carefully depicted setting and her compassion for her characters, whose ties are repeatedly tested. In 1937, Sandro Simone, a Jewish mathematics student, and Marco Terrizzi, a popular, outgoing cyclist, both recognize that their longtime friendship with Elisabetta D’Orfeo has turned to love, turning them into unintended rivals. Pretty and strong-willed, but shy about romance, Elisabetta weighs a possible relationship against her desire to become a journalist.

As the trio work out their feelings, the political situation deteriorates. Sandro’s and Marco’s fathers are longtime Fascists, optimistic about the positive change they see Mussolini bringing to their country. Their futures diverge once Il Duce strengthens Italy’s bond with Nazi Germany and starts promulgating anti-Semitic race laws.

Scottoline does an exceptional job placing readers in the moment as people’s worlds are upended, and Rome, with its storied architecture and vibrant culture, grows unrecognizably dark in spirit. Sandro’s father, a lawyer so entrenched in the Fascists that his beliefs essentially define him, has difficulty comprehending this betrayal of the Jews, while Marco, employed by a rising Party official, is blind to how his loyalties affect his friendships.

These and other heartbreaking moments are juxtaposed against scenes showing the warm heart of the Roman people, including feisty Nonna, crafter of delicious pasta at the restaurant where Elisabetta works. Even Elisabetta’s cat is a delightful personality. Family secrets from decades prior – in this ancient city, the past is never far away – add additional depth to this absorbing epic evoking the worst and very best of humanity.

Eternal was published in April by Putnam (I'd reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review). Lisa Scottoline has been enthusiastic about sharing the research she did for the novel, and you can read and view lots more via her website, which has an interactive map of Rome and eighteen episodes in her Behind the Book series. These short videos cover topics ranging from her trio of main characters to prominent Roman landmarks to food customs to the Stolpersteine, brass plaques memorializing Holocaust victims which were placed into the pavement at their last residence.

Published on June 05, 2021 15:29

June 3, 2021

Fidelity to the Truth in Biographical Fiction, an essay by Maryka Biaggio, author of The Point of Vanishing

Novelist Maryka Biaggio, who writes historical fiction about real-life people, is visiting today with an essay about an issue that all writers of biographical novels must address. Welcome, Maryka!

~

Fidelity to the Truth in Biographical Fiction Maryka Biaggio

“The historian serves the truth of his subject. The novelist serves the truth of his tale. As a novelist, I have tools no historian should touch: I can manipulate time and space, extrapolate from the written record to invent dialogue and incident, create fictional characters to bring you close to the historical figures, and fall back on my imagination when the research runs out.” --William Martin

Historical fiction based on real people is not unusual, and many readers love to eavesdrop on the lives of royals, celebrities, and notorious persons. Although biographies can satisfy some of that yen, fiction does something biography can’t always do—bring us inside these people’s worlds and show us their doubts, their fears, and the words they might have spoken.

Historical fiction based on real people is not unusual, and many readers love to eavesdrop on the lives of royals, celebrities, and notorious persons. Although biographies can satisfy some of that yen, fiction does something biography can’t always do—bring us inside these people’s worlds and show us their doubts, their fears, and the words they might have spoken.

But what of the importance of honesty in rendering these lives? Does the novelist owe it to his or her subjects to tell the tale true? If not, why would an author base a fictional account on an actual person in the first place? If it’s wild storytelling an author is after, why would he or she not steer clear of even insinuating that the subject of the novel is an actual person? And don’t readers expect a certain fidelity to the truth in biographical fiction? If they are led to believe a novel is based on the life of an actual person, don’t they have the right to expect they will find some resemblance to the life of that person?

I think most readers and writers would agree that, yes, novelists who base their stories on actual persons should adhere to the generally established truths about that person. And readers can reasonably expect that stories about real people not deviate wildly from the facts (unless they are labeled as alternative history).

But the “truth” and “facts” are not always easy to agree on, even among historians and biographers who aim for a high degree of accuracy. We can probably agree on the dates and certain facts about well-known events—say the particulars of a Civil War battle. But when it comes to the generals commanding their troops, we may dispute the motives behind their battle strategies. So what can readers reasonably expect and how can authors more or less hew to those expectations?

Joyce Carol Oates takes an interesting approach to this issue in her novel Blonde, which is certainly about Marilyn Monroe. Oates never refers to her subject by that name, but rather as Norma Jean Baker. Although Monroe’s affair with John F. Kennedy is a fairly well-established fact, she refers to him only as The President. Oates is not purporting to write a biography of Marilyn Monroe. She says in her Author’s Note that “Blonde is a radically distilled ‘life’ in the form of fiction, and, for all its length, synecdoche is the principle of appropriation.” She goes on to explain ways in which her account differed from her subject’s real life, and she also notes the many biographies and books on related topics she consulted. But this novel is a masterful work, portraying the inner world of its protagonist more richly than any biography ever could. In fact, I consider it Oates’ masterpiece, and she herself told me in 2009 that it is a particular favorite of hers.

Of course, there are many authors who are not shy about using their subjects’ actual names, sometimes in the titles, including Burr by Gore Vidal (about Aaron Burr) and I Was Anastasia by Ariel Lawhon. In the case of Lawhon’s book, the central question is whether the protagonist, Anna Anderson, actually was Anastasia Romanov. Lawhon explains in her Author’s Note that “it will come as no surprise . . . that I had to take liberties with this story. I did so primarily because the historical record contains a cast of hundreds, and that is simply untenable for a novel of any sort, much less one that is already complex and nonlinear.” She, like Oates, goes on to list authoritative sources and to articulate some of the ways that her novel deviates from the historical record--“all of them necessary for the sake of clarity and narrative drive.” So, again, both Oates and Lawhon are striving for a certain narrative authenticity, which sometimes necessitates deviations from the complex truth or from potentially confusing twists and turns.

I write novels about actual people, and I have had to confront questions about fidelity to the truth over and over in the telling. If I’m going to recount a story about an actual person, I believe I owe it to the reader to render the story in a way that doesn’t completely obscure that person’s actual life. But stories must make sense, they must adhere to an arc, they must take a person from one point to the next in a way that makes sense. Real life isn’t always this “logical,” but we expect a certain logic in novels. We realize Hamlet must pay a price for his indecision, we expect insight into some of the consequential decisions Marilyn Monroe made in her tragic life, and we want to know if Anna Anderson was a fraud or royalty. In the words of Iain M. Banks, “The trouble with writing fiction is that it has to make sense, whereas real life doesn't.”

So biographical fiction about historical figures has a tall order to fill—to show us the inner worlds of the character, to bring a certain fidelity to the story of their life, and to satisfy our curiosity about the meaning of their existence. Done well, biographical fiction can do all this and more—it can captivate and entertain.

About the Author:

Maryka Biaggio is a psychology professor turned novelist who specializes in historical fiction based on real people. She enjoys the challenge of starting with actual historical figures and dramatizing their lives–figuring out what motivated them to behave as they did, studying how the cultural and historical context may have influenced them, and recreating some sense of their emotional world through dialogue and action. Doubleday published her debut novel, Parlor Games, in January 2013. She lives in Portland, Oregon, that edgy green gem of the Pacific Northwest.

About The Point of Vanishing:

The Point of Vanishing is based on the true story of child prodigy writer, Barbara Follett. In 1939, at the age of 25, she vanished, never to be heard from again. Now historical novelist Maryka Biaggio brings her enigmatic story—and mysterious disappearance—to life.

Intrigued? Check out the author's book trailer below.

~

Fidelity to the Truth in Biographical Fiction Maryka Biaggio

“The historian serves the truth of his subject. The novelist serves the truth of his tale. As a novelist, I have tools no historian should touch: I can manipulate time and space, extrapolate from the written record to invent dialogue and incident, create fictional characters to bring you close to the historical figures, and fall back on my imagination when the research runs out.” --William Martin

Historical fiction based on real people is not unusual, and many readers love to eavesdrop on the lives of royals, celebrities, and notorious persons. Although biographies can satisfy some of that yen, fiction does something biography can’t always do—bring us inside these people’s worlds and show us their doubts, their fears, and the words they might have spoken.

Historical fiction based on real people is not unusual, and many readers love to eavesdrop on the lives of royals, celebrities, and notorious persons. Although biographies can satisfy some of that yen, fiction does something biography can’t always do—bring us inside these people’s worlds and show us their doubts, their fears, and the words they might have spoken. But what of the importance of honesty in rendering these lives? Does the novelist owe it to his or her subjects to tell the tale true? If not, why would an author base a fictional account on an actual person in the first place? If it’s wild storytelling an author is after, why would he or she not steer clear of even insinuating that the subject of the novel is an actual person? And don’t readers expect a certain fidelity to the truth in biographical fiction? If they are led to believe a novel is based on the life of an actual person, don’t they have the right to expect they will find some resemblance to the life of that person?

I think most readers and writers would agree that, yes, novelists who base their stories on actual persons should adhere to the generally established truths about that person. And readers can reasonably expect that stories about real people not deviate wildly from the facts (unless they are labeled as alternative history).

But the “truth” and “facts” are not always easy to agree on, even among historians and biographers who aim for a high degree of accuracy. We can probably agree on the dates and certain facts about well-known events—say the particulars of a Civil War battle. But when it comes to the generals commanding their troops, we may dispute the motives behind their battle strategies. So what can readers reasonably expect and how can authors more or less hew to those expectations?

Joyce Carol Oates takes an interesting approach to this issue in her novel Blonde, which is certainly about Marilyn Monroe. Oates never refers to her subject by that name, but rather as Norma Jean Baker. Although Monroe’s affair with John F. Kennedy is a fairly well-established fact, she refers to him only as The President. Oates is not purporting to write a biography of Marilyn Monroe. She says in her Author’s Note that “Blonde is a radically distilled ‘life’ in the form of fiction, and, for all its length, synecdoche is the principle of appropriation.” She goes on to explain ways in which her account differed from her subject’s real life, and she also notes the many biographies and books on related topics she consulted. But this novel is a masterful work, portraying the inner world of its protagonist more richly than any biography ever could. In fact, I consider it Oates’ masterpiece, and she herself told me in 2009 that it is a particular favorite of hers.

Of course, there are many authors who are not shy about using their subjects’ actual names, sometimes in the titles, including Burr by Gore Vidal (about Aaron Burr) and I Was Anastasia by Ariel Lawhon. In the case of Lawhon’s book, the central question is whether the protagonist, Anna Anderson, actually was Anastasia Romanov. Lawhon explains in her Author’s Note that “it will come as no surprise . . . that I had to take liberties with this story. I did so primarily because the historical record contains a cast of hundreds, and that is simply untenable for a novel of any sort, much less one that is already complex and nonlinear.” She, like Oates, goes on to list authoritative sources and to articulate some of the ways that her novel deviates from the historical record--“all of them necessary for the sake of clarity and narrative drive.” So, again, both Oates and Lawhon are striving for a certain narrative authenticity, which sometimes necessitates deviations from the complex truth or from potentially confusing twists and turns.

I write novels about actual people, and I have had to confront questions about fidelity to the truth over and over in the telling. If I’m going to recount a story about an actual person, I believe I owe it to the reader to render the story in a way that doesn’t completely obscure that person’s actual life. But stories must make sense, they must adhere to an arc, they must take a person from one point to the next in a way that makes sense. Real life isn’t always this “logical,” but we expect a certain logic in novels. We realize Hamlet must pay a price for his indecision, we expect insight into some of the consequential decisions Marilyn Monroe made in her tragic life, and we want to know if Anna Anderson was a fraud or royalty. In the words of Iain M. Banks, “The trouble with writing fiction is that it has to make sense, whereas real life doesn't.”

So biographical fiction about historical figures has a tall order to fill—to show us the inner worlds of the character, to bring a certain fidelity to the story of their life, and to satisfy our curiosity about the meaning of their existence. Done well, biographical fiction can do all this and more—it can captivate and entertain.

About the Author:

Maryka Biaggio is a psychology professor turned novelist who specializes in historical fiction based on real people. She enjoys the challenge of starting with actual historical figures and dramatizing their lives–figuring out what motivated them to behave as they did, studying how the cultural and historical context may have influenced them, and recreating some sense of their emotional world through dialogue and action. Doubleday published her debut novel, Parlor Games, in January 2013. She lives in Portland, Oregon, that edgy green gem of the Pacific Northwest.

About The Point of Vanishing:

The Point of Vanishing is based on the true story of child prodigy writer, Barbara Follett. In 1939, at the age of 25, she vanished, never to be heard from again. Now historical novelist Maryka Biaggio brings her enigmatic story—and mysterious disappearance—to life.

Intrigued? Check out the author's book trailer below.

Published on June 03, 2021 05:00

May 31, 2021

Love and Fury by Samantha Silva, a galvanizing portrait of English writer Mary Wollstonecraft

The lives of trailblazing English proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, overlapped by only eleven days, as Wollstonecraft tragically died from postpartum infection in 1797. In her second novel, Silva (Mr. Dickens and His Carol, 2019) probes the perspective of another literary icon, imagining the older Mary, weakened from childbirth, telling her life story to her baby at her midwife’s suggestion.

The lives of trailblazing English proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, overlapped by only eleven days, as Wollstonecraft tragically died from postpartum infection in 1797. In her second novel, Silva (Mr. Dickens and His Carol, 2019) probes the perspective of another literary icon, imagining the older Mary, weakened from childbirth, telling her life story to her baby at her midwife’s suggestion. Mary’s passionate declaration of selfhood carries readers on a wide-ranging, deep journey where she eloquently voices the circumstances shaping her views, her strong attachments to other independent thinkers, like Fanny Blood, and her struggles to escape societal constraints. Raised in a large family where her father abused her mother, she grows infuriated by gender inequality and aims to enlighten women who participate in their own diminution.

Related with superb detail on late-eighteenth-century locales and intellectual pursuits, Mary’s experiences leave her initially doubting the possibility of equal marriage between men and women. This absorbing tale of courage, sorrow, and the dance between independence and intimacy delivers a sense of triumphant catharsis.

Love and Fury was published by Flatiron in May, and I'd turned in this review for Booklist (the final version was published in their historical fiction issue on May 15th). Allison & Busby will publish the novel in the UK in mid-June. Terrific book, with a beautiful cover. You can read an excerpt at the author's website.

Published on May 31, 2021 15:00

May 30, 2021

Historical fiction giveaway for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month

In March, at the time of the blog's 15th anniversary, I'd mentioned I'd be posting a giveaway sometime soon. I decided to offer one during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (May), since this gives me the chance to offer up copies of four excellent historical novels, set in different countries within Asia and by writers of Asian heritage. All were five star reads for me.

Here are the books and links to my earlier reviews:

Janie Chang, The Library of Legends, which follows a real and mystical journey through war-torn 1937 China.

Charmaine Craig, Miss Burma, an engrossing novel of family, politics, and the history of modern Burma, based on the lives of the author's mother and grandparents.

Min Jin Lee, Pachinko, the bestselling, critically acclaimed novel of Korean life in 20th-century Japan.

Sujata Massey, The Widows of Malabar Hill, an original mystery (first in a series) starring the only female lawyer in 1920s Bombay.

To enter, fill in the form below. (For email subscribers, please visit the original blog post to enter the giveaway.) Deadline is Sunday, June 6th, a week from today. The winners will be randomly chosen and notified after the deadline. This giveaway is being funded by me, and is open to all readers in countries where Amazon or Book Depository delivers, except where prohibited by local laws.

Good luck!

Loading…

Published on May 30, 2021 08:00

May 25, 2021

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead, an adventurous historical fiction epic about daring, unconventional women

Great Circle is a richly spacious novel about a bold female pilot who feels simultaneously larger-than-life and intimately real. Marian Graves leaves behind a logbook from her final flight in 1950, when she attempted to circumnavigate the globe longitudinally. “My last descent won’t be the tumbling helpless kind but a sharp gannet plunge,” she writes, just before disappearing over Antarctica. A fictional character, Marian sits alongside historic aviators like Amy Johnson and Elinor Smith, whose tales are highlighted in asides, but her path is her own.

Great Circle is a richly spacious novel about a bold female pilot who feels simultaneously larger-than-life and intimately real. Marian Graves leaves behind a logbook from her final flight in 1950, when she attempted to circumnavigate the globe longitudinally. “My last descent won’t be the tumbling helpless kind but a sharp gannet plunge,” she writes, just before disappearing over Antarctica. A fictional character, Marian sits alongside historic aviators like Amy Johnson and Elinor Smith, whose tales are highlighted in asides, but her path is her own. Marian’s early life is similarly dramatic. As infants in 1914, she and twin brother Jamie are saved from a burning ship and sent to Missoula, Montana, to stay with their uncle, an artist with a gambling problem. Two barnstormer pilots ignite Marian’s urge to expand her world, but flying lessons are costly and inappropriate for girls.

Seeking direction and funding, she forms a reluctant attachment to Barclay McQueen, a wealthy, controlling bootlegger. Jamie, a vegetarian and pacifist, is equally captivating. Like Marian, he enters into relationships that spur him to confront his values.

Their stories run alongside that of Hadley Baxter, a contemporary actress whose messy love life is sabotaging her career. By playing Marian in a new biopic, she hopes to begin anew. Hadley’s account initially feels superficial in comparison, but as she researches her subject, the timelines have an exciting interplay, and missing pieces click into place.

The characters’ journeys encompass many locales – 1920s Montana, wild remote Alaska, WWII England with the Air Transport Auxiliary, a cloud’s opaque, dizzying interior – yet the research feels weightless. The vast black crevasse Marian glimpses while flying over western Canada comes to symbolize life’s darknesses: how do we move past situations that threaten to swallow us whole? Imbued with adventurous spirit and rendered in gorgeous language, this is an epic worth savoring.

Great Circle was published by Knopf this month, and I'd reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. If you're not convinced yet to put it on your TBR, read Ron Charles's review at the Washington Post, which recommends it as "perfect summer novel." All of his reviews are terrific and worth reading regardless.

Published on May 25, 2021 07:00

May 23, 2021

Edward Rutherfurd's China takes an epic, multi-perspective look at 19th-century Chinese history

For his newest epic about an intriguing world locale, Rutherfurd (Paris, 2013) dives into seventy years of Chinese history, beginning in 1839, as circumstances lead to the First Opium War, through the Boxer Rebellion and after.

For his newest epic about an intriguing world locale, Rutherfurd (Paris, 2013) dives into seventy years of Chinese history, beginning in 1839, as circumstances lead to the First Opium War, through the Boxer Rebellion and after. The novel has a tighter scope, time-wise, than his usual canvas, which allows for in-depth exploration of an overarching theme: China’s subjugation by Western powers, particularly Britain.

Taking the long view, Rutherfurd adeptly dramatizes the impact of and fallout from major events, including the Taiping Rebellion and the destruction of Beijing’s Summer Palace. His characters, among them British merchants, missionaries, Chinese government officials, peasants, pirates, and an artisan who rises high in service at the imperial palace through unusual means, assert their individuality while embodying beliefs on different sides of China’s internal and external conflicts.

The protagonists are predominantly men, but many fascinating women also feature in the story. Though the first third feels overly drawn-out, the novel takes an entertaining, educational journey through China’s rich and complex history, geography, art, and diverse cultures across a tumultuous epoch.

Edward Rutherfurd's China was published by Doubleday this May in the US, and I wrote this review (based on a PDF sent to me) for Booklist. The novel is 800pp long, and these days I find longer books easier to read in electronic form, so the PDF worked just fine. Your mileage may vary, though, and I have most of Rutherfurd's earlier novels in hardcover. My favorite among his work is The Princes of Ireland, the first in his two-book Dublin saga.

Published on May 23, 2021 08:50

May 22, 2021

A note for email subscribers to Reading the Past: mailing list migration next weekend

On April 14, I got an email from Google letting me know that its FeedBurner email subscription feature would be discontinued in July. FeedBurner is the application that powers the "Subscribe by email" widget used by Blogger, which I've been using for the past dozen years.

Software changes can be annoying, but free technology services don't last forever, and I'm glad FeedBurner has been up and running reliably for so long.

Since I got the news about the change, I've been looking for another product so that readers could receive new blog posts via email, and finally settled on Mailchimp.

I plan to migrate the list of email subscribers to the new Mailchimp platform over Memorial Day weekend in the US (May 29-31). If you're currently subscribed via email, you'll continue to be subscribed after the move. I expect everything will go smoothly (fingers crossed!).

The new emails will be coming from my address rather than from Google.com, so if you're a subscriber, you may want to add my email (sarah at readingthepast dot com) to your approved senders list so you don't miss anything.

Anyone who signed up for email updates within the last two weeks is already on the new mailing list. Also, anyone who doesn't receive new posts via email but would like to, please sign up via the Subscribe by Email box on the left-hand sidebar of the blog.

Thanks so much for reading my posts, however you choose to do so!

Software changes can be annoying, but free technology services don't last forever, and I'm glad FeedBurner has been up and running reliably for so long.

Since I got the news about the change, I've been looking for another product so that readers could receive new blog posts via email, and finally settled on Mailchimp.

I plan to migrate the list of email subscribers to the new Mailchimp platform over Memorial Day weekend in the US (May 29-31). If you're currently subscribed via email, you'll continue to be subscribed after the move. I expect everything will go smoothly (fingers crossed!).

The new emails will be coming from my address rather than from Google.com, so if you're a subscriber, you may want to add my email (sarah at readingthepast dot com) to your approved senders list so you don't miss anything.

Anyone who signed up for email updates within the last two weeks is already on the new mailing list. Also, anyone who doesn't receive new posts via email but would like to, please sign up via the Subscribe by Email box on the left-hand sidebar of the blog.

Thanks so much for reading my posts, however you choose to do so!

Published on May 22, 2021 06:23

May 20, 2021

Review of the final book in Alison Weir's Six Tudor Queens Series: Katharine Parr, The Sixth Wife

Henry VIII was neither her first nor her last husband, yet it’s Katharine Parr’s status as his sixth wife, naturally, that commands the most attention. Weir’s admirable conclusion to her Six Tudor Queens series reveals Katharine as a woman of intellect, kindness, and strategic acumen who plays the long game to attain her heart’s desires.

Henry VIII was neither her first nor her last husband, yet it’s Katharine Parr’s status as his sixth wife, naturally, that commands the most attention. Weir’s admirable conclusion to her Six Tudor Queens series reveals Katharine as a woman of intellect, kindness, and strategic acumen who plays the long game to attain her heart’s desires. Twice-widowed when she marries Henry, she brings a diverse range of experiences to her queenship. Weir smoothly knits all these life segments together, showing how Katharine’s background shapes her character and beliefs.

Raised amid a loving family that respects women’s education, she first weds a nobleman’s son and secondly an older, Catholic baron. The story strikes a clear path through the complicated political and religious circumstances of 1520s-40s England as the action sweeps from Lincolnshire to Yorkshire during the Pilgrimage of Grace to dazzling London.

In choosing Henry over personal happiness, Katharine, secretly Protestant, seeks to guide the realm in that direction. She comes to love the King, despite his age and infirmities, but influential women tend to acquire enemies.

Her relations with her stepchildren are handled with realistic nuance, and Henry’s death drops her into intense romantic intrigue. This wide-ranging novel expertly showcases Katharine’s courageous, eventful life and many noteworthy accomplishments.

Katharine Parr, The Sixth Wife was published by Ballantine this month in the US, and by Headline Review in the UK. I wrote this review for Booklist and it appeared in the April 15th issue.

This is the fifth book in the series I've reviewed... all except the first book, which focused on Katherine of Aragon. This book and the third, Jane Seymour, The Haunted Queen, are my favorites. With this one, I particularly liked how Weir devoted so much time to Katharine's life before her marriage to Henry VIII; she was well-educated and traveled quite a bit within England. She had five stepchildren in all, including, of course, the future Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Now that this series is complete, I wonder what direction Weir will take next with her fiction.

Published on May 20, 2021 07:48

May 16, 2021

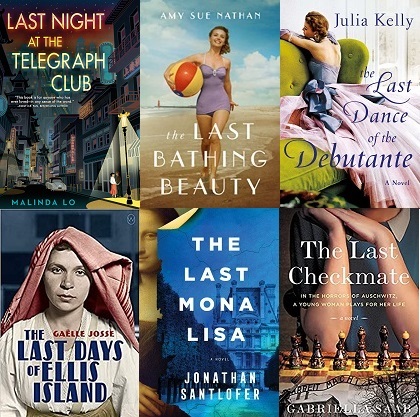

Trendspotting: the many new historical novels with "Last" in their titles

Have you noticed that the titles of many new historical novels have a certain air of finality?

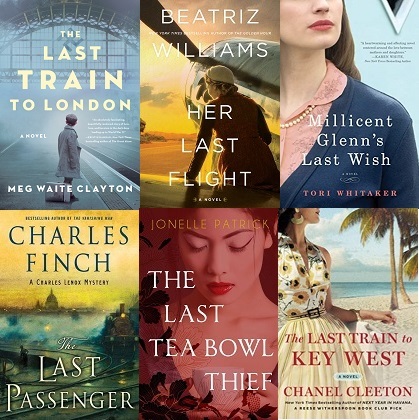

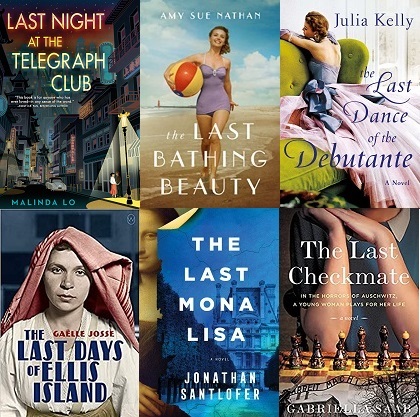

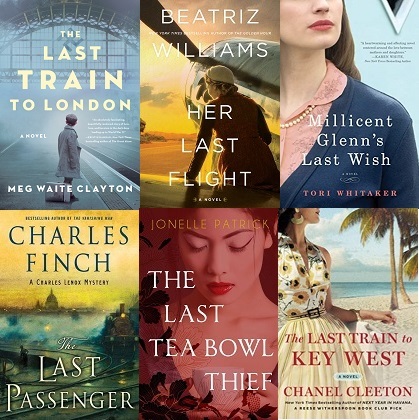

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were.

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were.

(Shown above: The Last Tiara by M.J. Rose; The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly; The Last Green Valley by Mark Sullivan; The Last Night in London by Karen White; The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin; The Last One Home by Shari J. Ryan.)

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.

(Above: Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo; The Last Bathing Beauty by Amy Sue Nathan; The Last Dance of the Debutante by Julia Kelly, forthcoming; The Last Days of Ellis Island by Gaelle Josse; The Last Mona Lisa by Jonathan Santlofer; The Last Checkmate by Gabriella Saab. These last two are out later this year.)

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.

(Above: The Last Train to London by Meg Waite Clayton; Her Last Flight by Beatriz Williams; Millicent Glenn's Last Wish by Tori Whitaker; The Last Passenger by Charles Finch; The Last Tea Bowl Thief by Jonelle Patrick; The Last Train to Key West by Chanel Cleeton.)

I'm sure we aren't seeing the last of this title trend.

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were.

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were. (Shown above: The Last Tiara by M.J. Rose; The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly; The Last Green Valley by Mark Sullivan; The Last Night in London by Karen White; The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin; The Last One Home by Shari J. Ryan.)

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.(Above: Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo; The Last Bathing Beauty by Amy Sue Nathan; The Last Dance of the Debutante by Julia Kelly, forthcoming; The Last Days of Ellis Island by Gaelle Josse; The Last Mona Lisa by Jonathan Santlofer; The Last Checkmate by Gabriella Saab. These last two are out later this year.)

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.(Above: The Last Train to London by Meg Waite Clayton; Her Last Flight by Beatriz Williams; Millicent Glenn's Last Wish by Tori Whitaker; The Last Passenger by Charles Finch; The Last Tea Bowl Thief by Jonelle Patrick; The Last Train to Key West by Chanel Cleeton.)

I'm sure we aren't seeing the last of this title trend.

Published on May 16, 2021 09:30

May 14, 2021

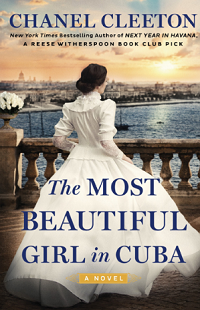

Chanel Cleeton's The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba follows three bold women during the Cuban War of Independence

Chanel Cleeton’s fourth historical novel explores the nature of freedom on multiple levels, from the dynamics of international politics to the individual dilemmas of three bold women. They all become embroiled, in different ways, in Cuba’s fight for independence. They also find themselves caught between society’s expectations and the images they want to craft for themselves.

Chanel Cleeton’s fourth historical novel explores the nature of freedom on multiple levels, from the dynamics of international politics to the individual dilemmas of three bold women. They all become embroiled, in different ways, in Cuba’s fight for independence. They also find themselves caught between society’s expectations and the images they want to craft for themselves. Set in the late 19th century, the book’s subject is the lead-up to the Spanish-American War, an event rarely touched upon in historical fiction, especially from the female viewpoint.

As the Cuban people strive to overturn the repressive rule of their Spanish colonizers, Evangelina Cisneros, a young Cuban woman, is thrust into a grim women’s prison in Havana under false political charges. She’s a historical figure, and her plotline aligns with real-life history. The other two protagonists are Grace Harrington, an American newspaper journalist working for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and Marina Perez, a Cuban farmer’s wife forced to leave her home with her family, travel across the ruined countryside, and endure dire conditions in a reconcentration camp.

It takes a little while to get used to all three viewpoints and the switches among them, but the stories come together in a powerful way.

Competition between Hearst’s paper and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World is cutthroat, and Grace places herself in the thick of it. Operating under the principle that it’s important not just to report on the news, but act on it, the Journal aims to pressure the United States into backing Cuban independence. When Hearst learns about Evangelina languishing in prison, the paper takes her up as a symbol of injustice, declares her the “most beautiful girl in Cuba,” and plans to break her out. Under the guise of a laundress, Marina delivers secret messages for the rebels while worrying desperately about her beloved husband, who’s separated from her and their daughter while fighting for freedom.

I thoroughly enjoyed this multifaceted view of this pivotal historical time: the view of late 19th-century Cuba from the Cuban and American perspectives, the action-intensive plot, and the women’s different but equally touching love stories. Their emotionally grabbing quests for self-determination run alongside that of Cuba in this wide-ranging and page-turning tale.

The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba was published by Berkley on May 4th; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Published on May 14, 2021 13:14