Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 29

November 8, 2021

Review of Paulette Kennedy's Parting the Veil, a Victorian romantic suspense debut

Paulette Kennedy’s debut, Parting the Veil, is a veritable Gothic feast. Romantic suspense is a genre the author clearly loves, and the novel’s stuffed full of its hallmarks and tropes: a single woman, a mysterious inheritance, a crumbling mansion reputed to be haunted, its broodingly handsome owner, a shocking Tarot card reading… and that’s just to start.

Paulette Kennedy’s debut, Parting the Veil, is a veritable Gothic feast. Romantic suspense is a genre the author clearly loves, and the novel’s stuffed full of its hallmarks and tropes: a single woman, a mysterious inheritance, a crumbling mansion reputed to be haunted, its broodingly handsome owner, a shocking Tarot card reading… and that’s just to start. The fun is in recognizing which of these elements will play out as expected, and which will be given an unexpected twist.

In 1899, Eliza Sullivan and her younger, mixed-race half-sister Lydia, natives of New Orleans, arrive in the Hampshire village of Chesterbridge to take up residence at Sherbourne House, which had been left to Eliza by a great-aunt she barely knew. The terms of Tante Theo’s bequest, though, disconcert the independent-minded heiress. Eliza learns that to take possession of her fortune, she must get married within three months.

Malcolm, Viscount Havenwood, is the sole surviving member of his family after a fire three years earlier damaged his home’s south wing. An immediate physical attraction springs up between Eliza and Malcolm. She throws caution to the wind and – against the practical Lydia’s advice – weds him.

But married life perplexes Eliza. While ardent in the bedroom at night, Malcolm is cold and proper, even condescending, during the day. His behavior will have readers wondering whether Malcolm deserves a happily-ever-after with our heroine.

A profusion of mysteries drives the story along. What (or who) causes the rhythmic tapping Eliza hears at night? What happened to Malcolm’s Scottish mother, who was rumored to be mad? Why does he behave so weirdly? Why is Eliza haunted by painful childhood memories?

author Paulette Kennedy

author Paulette KennedyThe atmosphere is a piquant blend of Southern Gothic meets Jane Eyre. As Americans, Eliza and Lydia’s entrance into Hampshire society meets with curiosity; contrary to stereotype, though, they aren't treated like unwelcome outsiders. They form friendships with local women, including newlywed Sarah Nelson, whose candor is a breath of fresh air. There are hints of same-sex relationships in some women’s pasts, which add layers of intrigue. (One minor complaint: the pet name “darling” is overused.)

For readers on the fence about romantic suspense, the ambience may be overwhelming. But for those who adore it, settle into this compulsive read and soak it all in.

Parting the Veil is published by Lake Union this month; I read it from a NetGalley copy as part of the blog tour for Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours.

Published on November 08, 2021 04:30

November 5, 2021

The Family by Naomi Krupitsky visits mid-20th-century Mafia families from the female viewpoint

Mario Puzo meets Elena Ferrante in Krupitsky’s dynamite debut novel, a decades-spanning saga beginning in 1920s Brooklyn. “There is no easy way to untangle what is Family and what is family,” her characters realize, to their chagrin and peril.

Mario Puzo meets Elena Ferrante in Krupitsky’s dynamite debut novel, a decades-spanning saga beginning in 1920s Brooklyn. “There is no easy way to untangle what is Family and what is family,” her characters realize, to their chagrin and peril. Daughters of influential Mafiosos, fiery Sofia Colicchio and her introverted best friend, Antonia Russo, know their families aren’t typical. Schoolmates avoid them, their mothers constantly worry, and on Sundays they attend a large Italian feast at their fathers’ boss’s home.

When Antonia’s papa tries to escape his profession, he gets “disappeared,” a terrible warning against future betrayals. Sofia and Antonia are resilient, multifaceted young women whose bond occasionally strains as they test the boundaries of independence, and their choice of husbands ensnares them further in Family business.

Depicting twentieth-century Mafia families primarily from the female viewpoint is a fabulous concept that Krupitsky carries out with aplomb. Perspective shifts are smooth, and the backdrops of Prohibition and WWII are superbly realized.

Italian American traditions (including delicious casseroles) are highlighted, and the unique immigration stories show why and how Italian and Jewish newcomers get pulled into organized crime. Fans of Adriana Trigiani and Lynda Cohen Loigman will inhale this tense, engrossing novel about family ties, women’s friendships, and the treacherous complications of loyalty.

The Family was published on Tuesday by Putnam in hardcover and ebook. I read it back in May and reviewed it for the September 1st issue of Booklist, and I'm glad my editor there decided to assign it to me!

Also, am I wrong, or does the font used on the cover remind you of the one used for Mario Puzo's The Family, his novel about the infamous Borgias of 15th-century Italy, who he called the "original crime family"?

Published on November 05, 2021 07:42

November 1, 2021

Carolyn Korsmeyer discusses writing and researching Charlotte's Story, her novel about Charlotte Lucas from Pride & Prejudice

Please help me welcome Carolyn Korsmeyer with a post about re-creating the world of Charlotte Lucas from Pride and Prejudice, and what she learned over the course of the writing process. Her explanation of the differences between approaching a setting from the viewpoint of a reader vs. that of a writer really resonated with me.

~

Researching and Writing Charlotte's Story

Carolyn Korsmeyer

I have been drawn to historical fiction since I first learned to read, but my first attempt at writing it came when I wrote a novel in the voice of one of Jane Austen's characters, Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice. It was her realistic, dispassionate, and cool decision to wed the Reverend William Collins that interested me, because I thought reflection on that choice might resonate with contemporary readers in ways that extend beyond Austen's own times.

I have been drawn to historical fiction since I first learned to read, but my first attempt at writing it came when I wrote a novel in the voice of one of Jane Austen's characters, Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice. It was her realistic, dispassionate, and cool decision to wed the Reverend William Collins that interested me, because I thought reflection on that choice might resonate with contemporary readers in ways that extend beyond Austen's own times.

It was intriguing to imagine the inner life of a woman who faced some of the same choices as we do today, and yet was hindered by customs and limits that no longer exert the same force—although they have by no means disappeared. I decided to write a first-person narrative so that her own thoughts and worries were immediately accessible on the page. Her ruminations needed to conform reasonably well with early nineteenth-century sensibilities, but they also needed to ring true to readers today.

Charlotte is a middle-class woman with few financial resources of her own. She is not particularly pretty, so a stable and prosperous future more or less depends on making a good marriage. It might seem, to use contemporary language, that she "settles" on an unattractive man of means whom few others would want. That, however, is not quite the way I imagined it. Charlotte recognizes and accepts social restrictions that women today would not, and she is not inclined to be rebellious. (Unlike the heedless Lydia Bennet, for instance.) On the other hand, she is also not passive. She is strategic, in her own words "conniving," when the need arises.

Austen is still so popular that for many readers her novels almost achieve the familiarity that we find with contemporary fiction. That was my own impression when I launched into writing Charlotte's Story. But then I began to stumble over details about her household, the way she got from place to place, what she ate, what she wore, how long it took to walk from one neighbor to another, and so forth. Pretty soon I realized the difference between thinking you recognize a world as you read, and actually writing that world, when puzzles and uncertainties emerge.

The same thing, incidentally, has happened with my second historical novel, which is set in a place where I have lived for decades and whose history is very familiar. But when I actually began to write this story, its details demanded an unexpected amount of research. I think this demonstrates a deceptive and elusive distinction between reading—where you enter another world and feel at home—and writing—where inventing that world reveals your ignorance. It brings the gap between now and then into focus.

For Charlotte's Story, I took off from the text of Pride and Prejudice itself, imagining myself in the Bennet rooms (oh—but what's the floor plan?), walking into Meryton (how long does that take?), perhaps riding in a coach (what, actually, is a barouche?), stitching by the fire (how do you net a purse?) Immediately, I realized that I didn’t know as much as I thought I did.

Charlotte was brought into being just as the COVID pandemic shut us all down, so I was lucky that lots of virtual resources were available. I had recently joined the Jane Austen Society, and they held their 2020 annual meeting virtually. It was full of enlightening and entertaining events. I watched lectures on conveyances, clothing, dancing, manners. I took a virtual tour of Austen's home in Chawton. Later I tuned into lectures sponsored by local chapters. With the libraries all closed, I scoured my own shelves and read every nineteenth-century English novel I could find, plus some old travel literature that had landed in my attic. I looked up maps of English cities like Bath to see how their streetscapes had changed over time. And I also watched period-style movies and TV series, noting with some alarm when they came in for criticism regarding their historical accuracy (Wrong hairstyle! Inappropriate shoes!).

author Carolyn Korsmeyer

author Carolyn Korsmeyer

However, the errors to guard against are far from just factual. There is also the question of style and tenor of writing, which keeps a narrative in tune with the time of its settings. For example, the dialogue exchanged in Austen's own novels is far more elaborate and repetitive than would be common now, but Charlotte and her friends needed to converse in a manner that fit their times. It isn't a good idea just to try to imitate a style; rather one needs to find a tone and vocabulary that is congenial with an older one, but that also flows naturally for contemporary readers.

Even more subtle are the distortions that might enter one's writing when developing a character from the past. It is fascinating to wonder how influenced we all are by our own times and cultures. If we lived two centuries ago, would we have the same values and attitudes and feelings? Are there universals that apply to all people at all times? Perhaps the very basic ones do: we fear danger, we worry about children, are angry at insults, and so forth. But we are by no means insulted at the same things, and our worries and fears have quite different content now. (Think of Geraldine Brooks's wonderful novel Caleb's Crossing and the way she conjures a fear of hell in her Puritan characters.) Literature that was written in the past gives us hints about those similarities and differences, and fiction can explore them still further. The historical fiction writer can be seen as a historian of emotions as well as of actions, characters, and plots from long ago.

~

About Charlotte's Story (TouchPoint Press; on-sale October 11th; ISBN: 978-1-952816-58-1; trade paperback and ebook editions):

Charlotte Lucas, a character first appearing in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, has made an unfortunate marriage to the loquacious William Collins, reckoning that his tedious conversation is a small price to pay for the prosperous home and family she hopes to gain. However, trouble brews within the first months of marriage, and she is upset and angered by his presumptuous tendency to interfere with her friendships.

To ease the strain of their relationship, Charlotte leaves her husband to visit the fashionable city of Bath with several women companions. The weeks in Bath prove to be a time for self-discovery and freedom, even license. Although the marital frost between Charlotte and William begins to thaw, that tranquility lasts only briefly, for events in Bath have resulted in an unfortunate, even calamitous, consequence.

Charlotte devises a solution to the advantage of all that combines bold connivance and compassionate duplicity. Some would castigate her audacious stratagem, but she believes it justified by the hope of happiness and the wit and courage to seek it.

About the author:

A longtime admiration of Jane Austen and other nineteenth-century women novelists led Carolyn Korsmeyer to write Charlotte’s Story. She is also the author of numerous philosophical works, including Things: In Touch with the Past, Savoring Disgust: The Foul and the Fair in Aesthetics, and Making Sense of Taste: Food and Philosophy. Her website is https://www.carolynkorsmeyer.com.

~

Researching and Writing Charlotte's Story

Carolyn Korsmeyer

I have been drawn to historical fiction since I first learned to read, but my first attempt at writing it came when I wrote a novel in the voice of one of Jane Austen's characters, Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice. It was her realistic, dispassionate, and cool decision to wed the Reverend William Collins that interested me, because I thought reflection on that choice might resonate with contemporary readers in ways that extend beyond Austen's own times.

I have been drawn to historical fiction since I first learned to read, but my first attempt at writing it came when I wrote a novel in the voice of one of Jane Austen's characters, Charlotte Lucas of Pride and Prejudice. It was her realistic, dispassionate, and cool decision to wed the Reverend William Collins that interested me, because I thought reflection on that choice might resonate with contemporary readers in ways that extend beyond Austen's own times.It was intriguing to imagine the inner life of a woman who faced some of the same choices as we do today, and yet was hindered by customs and limits that no longer exert the same force—although they have by no means disappeared. I decided to write a first-person narrative so that her own thoughts and worries were immediately accessible on the page. Her ruminations needed to conform reasonably well with early nineteenth-century sensibilities, but they also needed to ring true to readers today.

Charlotte is a middle-class woman with few financial resources of her own. She is not particularly pretty, so a stable and prosperous future more or less depends on making a good marriage. It might seem, to use contemporary language, that she "settles" on an unattractive man of means whom few others would want. That, however, is not quite the way I imagined it. Charlotte recognizes and accepts social restrictions that women today would not, and she is not inclined to be rebellious. (Unlike the heedless Lydia Bennet, for instance.) On the other hand, she is also not passive. She is strategic, in her own words "conniving," when the need arises.

Austen is still so popular that for many readers her novels almost achieve the familiarity that we find with contemporary fiction. That was my own impression when I launched into writing Charlotte's Story. But then I began to stumble over details about her household, the way she got from place to place, what she ate, what she wore, how long it took to walk from one neighbor to another, and so forth. Pretty soon I realized the difference between thinking you recognize a world as you read, and actually writing that world, when puzzles and uncertainties emerge.

The same thing, incidentally, has happened with my second historical novel, which is set in a place where I have lived for decades and whose history is very familiar. But when I actually began to write this story, its details demanded an unexpected amount of research. I think this demonstrates a deceptive and elusive distinction between reading—where you enter another world and feel at home—and writing—where inventing that world reveals your ignorance. It brings the gap between now and then into focus.

For Charlotte's Story, I took off from the text of Pride and Prejudice itself, imagining myself in the Bennet rooms (oh—but what's the floor plan?), walking into Meryton (how long does that take?), perhaps riding in a coach (what, actually, is a barouche?), stitching by the fire (how do you net a purse?) Immediately, I realized that I didn’t know as much as I thought I did.

Charlotte was brought into being just as the COVID pandemic shut us all down, so I was lucky that lots of virtual resources were available. I had recently joined the Jane Austen Society, and they held their 2020 annual meeting virtually. It was full of enlightening and entertaining events. I watched lectures on conveyances, clothing, dancing, manners. I took a virtual tour of Austen's home in Chawton. Later I tuned into lectures sponsored by local chapters. With the libraries all closed, I scoured my own shelves and read every nineteenth-century English novel I could find, plus some old travel literature that had landed in my attic. I looked up maps of English cities like Bath to see how their streetscapes had changed over time. And I also watched period-style movies and TV series, noting with some alarm when they came in for criticism regarding their historical accuracy (Wrong hairstyle! Inappropriate shoes!).

author Carolyn Korsmeyer

author Carolyn KorsmeyerHowever, the errors to guard against are far from just factual. There is also the question of style and tenor of writing, which keeps a narrative in tune with the time of its settings. For example, the dialogue exchanged in Austen's own novels is far more elaborate and repetitive than would be common now, but Charlotte and her friends needed to converse in a manner that fit their times. It isn't a good idea just to try to imitate a style; rather one needs to find a tone and vocabulary that is congenial with an older one, but that also flows naturally for contemporary readers.

Even more subtle are the distortions that might enter one's writing when developing a character from the past. It is fascinating to wonder how influenced we all are by our own times and cultures. If we lived two centuries ago, would we have the same values and attitudes and feelings? Are there universals that apply to all people at all times? Perhaps the very basic ones do: we fear danger, we worry about children, are angry at insults, and so forth. But we are by no means insulted at the same things, and our worries and fears have quite different content now. (Think of Geraldine Brooks's wonderful novel Caleb's Crossing and the way she conjures a fear of hell in her Puritan characters.) Literature that was written in the past gives us hints about those similarities and differences, and fiction can explore them still further. The historical fiction writer can be seen as a historian of emotions as well as of actions, characters, and plots from long ago.

~

About Charlotte's Story (TouchPoint Press; on-sale October 11th; ISBN: 978-1-952816-58-1; trade paperback and ebook editions):

Charlotte Lucas, a character first appearing in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, has made an unfortunate marriage to the loquacious William Collins, reckoning that his tedious conversation is a small price to pay for the prosperous home and family she hopes to gain. However, trouble brews within the first months of marriage, and she is upset and angered by his presumptuous tendency to interfere with her friendships.

To ease the strain of their relationship, Charlotte leaves her husband to visit the fashionable city of Bath with several women companions. The weeks in Bath prove to be a time for self-discovery and freedom, even license. Although the marital frost between Charlotte and William begins to thaw, that tranquility lasts only briefly, for events in Bath have resulted in an unfortunate, even calamitous, consequence.

Charlotte devises a solution to the advantage of all that combines bold connivance and compassionate duplicity. Some would castigate her audacious stratagem, but she believes it justified by the hope of happiness and the wit and courage to seek it.

About the author:

A longtime admiration of Jane Austen and other nineteenth-century women novelists led Carolyn Korsmeyer to write Charlotte’s Story. She is also the author of numerous philosophical works, including Things: In Touch with the Past, Savoring Disgust: The Foul and the Fair in Aesthetics, and Making Sense of Taste: Food and Philosophy. Her website is https://www.carolynkorsmeyer.com.

Published on November 01, 2021 06:00

October 28, 2021

New post about popular trends in historical fiction

Author and blogger M. K. (Mary) Tod recently invited me to write a post for her site about current trends in historical fiction, and I was happy to accept.

Please jump over to A Writer of History to read it, and thanks to Mary for the opportunity!

Published on October 28, 2021 11:33

October 26, 2021

Interview with Clarissa Harwood, author of the gothic novel The Curse of Morton Abbey, set in 1890s Yorkshire

I'm glad to welcome Clarissa Harwood back to Reading the Past for an interview about her new historical gothic novel, The Curse of Morton Abbey, which is out today. The heroine is Vaughan Springthorpe, a woman trained as a solicitor, who arrives at the Yorkshire estate of Sir Peter Spencer to help prepare it for future sale in his absence. Her employer's invalid brother, Nicholas, doesn't want his home sold, though. Estate gardener Joe Dixon appears to support her efforts, but there are enough mysterious happenings around Morton Abbey to make Vaughan realize that someone wants her gone. Nonetheless, she wants to prove herself and presses forward with her task, uncovering uncomfortable facts about the estate and the town in the process. I enjoyed trying to predict where the plot would lead, and the story is dark and suspenseful without edging into horror. If you like romantic suspense, put it on your list!

How did you choose the time and place of late Victorian Yorkshire?

How did you choose the time and place of late Victorian Yorkshire?

This was a no-brainer for me because late-Victorian Yorkshire is my happy place! The novels of the Brontë sisters were a formative influence from my young adulthood, especially Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. I know I’m not alone in considering the Yorkshire moors the most romantic, evocative place on earth because of these novels. Of course, the Brontës were early rather than late Victorian, but I have a great love for late-Victorian literature because of my academic training. My doctoral dissertation focused on fin de siècle works such as Dracula and Heart of Darkness with their highly symbolic monstrous figures that represented widespread societal fears of the era.

Vaughan has an intriguing profession for a woman of her time, having been trained as a solicitor without the official designation (and with an expertise in conveyancing – a term new to me, but an important role). How did you research her career?

Because of Vaughan’s strong personality, I knew she needed to work at something unusual for a woman, but she’s definitely an introvert and wouldn’t want to be a leader or at the forefront of a movement like Lilia in Impossible Saints, so she needed something she could do quietly while still showing her determination and strength. Also, I needed a reason for her to go to Morton Abbey that didn’t involve childcare (she is not governess material). I taxed the patience of my university’s law librarian as I researched women law clerks and lawyers for months. Since women couldn’t officially practice law in late-Victorian England, it was difficult to find anything until I stumbled upon a real-life woman who was unofficially practicing law in late-Victorian England: Eliza Orme, who ultimately became the first woman to earn a law degree in England. I couldn’t resist giving Eliza a cameo role in The Curse of Morton Abbey.

I enjoyed how you combined classic gothic elements, like the English estate and family full of secrets, with feminist touches. Who are your influences in the genre of gothic fiction and romantic suspense?

There are too many influences to list them all, but I’ll start with the gothic novelists whose work I studied and taught: Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, and Bram Stoker. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca is another iconic gothic novel, and I was scandalized by the way Netflix twisted it into a romance, which it isn’t! (I love romance, but I get testy when brilliant novels are adapted in ways that present them falsely.) For romantic suspense, Mary Stewart is a huge influence, and I re-read her brilliant novel The Ivy Tree regularly. More recent novels that draw on the gothic tradition while offering new twists include Kris Waldherr’s The Lost History of Dreams, Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, and Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic, which have contributed to the resurgence of interest in this genre.

The author visiting the Yorkshire Moors

The author visiting the Yorkshire Moors

The gardens that Joe Dixon maintains are beautiful and provide a restful atmosphere amid the mysteries of Morton Abbey. Do you have a favorite English garden?

This question made me laugh because I have no personal interest in gardens or gardening: in fact, my husband has banned me from working in our garden because I (unintentionally) kill the plants. For a while he let me do some pruning, but apparently I cut too much off the bushes. I do love sitting in a beautiful garden if the weather isn’t too hot, but I had to do a lot of research just to figure out what the names of basic plants were and what sort of work Joe would be doing in a late-Victorian Yorkshire garden.

What have been the most enjoyable and/or challenging aspects of independent publishing?

I feel as if I have the best of both worlds because my first two novels were traditionally published. If I’d started with indie publishing, I think I would have been completely overwhelmed, but because I knew generally how the process worked and how long it would take, I constructed a reasonable timeline for The Curse of Morton Abbey. Another advantage of having two published novels already under my belt was being able to draw on the knowledge and experience of my wonderful community of authors. They have saved me from making plenty of bad decisions!

The best part of independent publishing has been having control over every aspect of the process. It was especially fun working with my cover designer, Tim Barber at Dissect Designs (he was a dream to work with and I highly recommend him). The hardest part of independent publishing has been the stigma that still exists in the industry. It’s difficult and expensive to be reviewed by one of the big trade publications if you’re an indie author. The self-doubt that every author experiences from time to time is also worse if you’re an indie author because you don’t have the gatekeepers of the publishing world validating your work. What has helped me the most in this respect has been the support and encouragement of my agent, Laura Crockett. In fact, The Curse of Morton Abbey is the novel that first got her attention and prompted her offer of representation.

Thank you so much for inviting me to do this interview!

My pleasure, and thanks for answering my questions!

~

For more information about Clarissa Harwood and her books, please see her website, or find it on Goodreads here.

How did you choose the time and place of late Victorian Yorkshire?

How did you choose the time and place of late Victorian Yorkshire?This was a no-brainer for me because late-Victorian Yorkshire is my happy place! The novels of the Brontë sisters were a formative influence from my young adulthood, especially Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. I know I’m not alone in considering the Yorkshire moors the most romantic, evocative place on earth because of these novels. Of course, the Brontës were early rather than late Victorian, but I have a great love for late-Victorian literature because of my academic training. My doctoral dissertation focused on fin de siècle works such as Dracula and Heart of Darkness with their highly symbolic monstrous figures that represented widespread societal fears of the era.

Vaughan has an intriguing profession for a woman of her time, having been trained as a solicitor without the official designation (and with an expertise in conveyancing – a term new to me, but an important role). How did you research her career?

Because of Vaughan’s strong personality, I knew she needed to work at something unusual for a woman, but she’s definitely an introvert and wouldn’t want to be a leader or at the forefront of a movement like Lilia in Impossible Saints, so she needed something she could do quietly while still showing her determination and strength. Also, I needed a reason for her to go to Morton Abbey that didn’t involve childcare (she is not governess material). I taxed the patience of my university’s law librarian as I researched women law clerks and lawyers for months. Since women couldn’t officially practice law in late-Victorian England, it was difficult to find anything until I stumbled upon a real-life woman who was unofficially practicing law in late-Victorian England: Eliza Orme, who ultimately became the first woman to earn a law degree in England. I couldn’t resist giving Eliza a cameo role in The Curse of Morton Abbey.

I enjoyed how you combined classic gothic elements, like the English estate and family full of secrets, with feminist touches. Who are your influences in the genre of gothic fiction and romantic suspense?

There are too many influences to list them all, but I’ll start with the gothic novelists whose work I studied and taught: Horace Walpole, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, and Bram Stoker. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca is another iconic gothic novel, and I was scandalized by the way Netflix twisted it into a romance, which it isn’t! (I love romance, but I get testy when brilliant novels are adapted in ways that present them falsely.) For romantic suspense, Mary Stewart is a huge influence, and I re-read her brilliant novel The Ivy Tree regularly. More recent novels that draw on the gothic tradition while offering new twists include Kris Waldherr’s The Lost History of Dreams, Sarah Perry’s Melmoth, and Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic, which have contributed to the resurgence of interest in this genre.

The author visiting the Yorkshire Moors

The author visiting the Yorkshire MoorsThe gardens that Joe Dixon maintains are beautiful and provide a restful atmosphere amid the mysteries of Morton Abbey. Do you have a favorite English garden?

This question made me laugh because I have no personal interest in gardens or gardening: in fact, my husband has banned me from working in our garden because I (unintentionally) kill the plants. For a while he let me do some pruning, but apparently I cut too much off the bushes. I do love sitting in a beautiful garden if the weather isn’t too hot, but I had to do a lot of research just to figure out what the names of basic plants were and what sort of work Joe would be doing in a late-Victorian Yorkshire garden.

What have been the most enjoyable and/or challenging aspects of independent publishing?

I feel as if I have the best of both worlds because my first two novels were traditionally published. If I’d started with indie publishing, I think I would have been completely overwhelmed, but because I knew generally how the process worked and how long it would take, I constructed a reasonable timeline for The Curse of Morton Abbey. Another advantage of having two published novels already under my belt was being able to draw on the knowledge and experience of my wonderful community of authors. They have saved me from making plenty of bad decisions!

The best part of independent publishing has been having control over every aspect of the process. It was especially fun working with my cover designer, Tim Barber at Dissect Designs (he was a dream to work with and I highly recommend him). The hardest part of independent publishing has been the stigma that still exists in the industry. It’s difficult and expensive to be reviewed by one of the big trade publications if you’re an indie author. The self-doubt that every author experiences from time to time is also worse if you’re an indie author because you don’t have the gatekeepers of the publishing world validating your work. What has helped me the most in this respect has been the support and encouragement of my agent, Laura Crockett. In fact, The Curse of Morton Abbey is the novel that first got her attention and prompted her offer of representation.

Thank you so much for inviting me to do this interview!

My pleasure, and thanks for answering my questions!

~

For more information about Clarissa Harwood and her books, please see her website, or find it on Goodreads here.

Published on October 26, 2021 06:00

October 23, 2021

Eye of a Rook by Josephine Taylor explores women's pain and health, past and present

Australian writer Josephine Taylor’s first novel is a psychologically penetrating and honest read that juxtaposes two women, one Victorian and one modern-day, who suffer from the same debilitating medical condition.

Australian writer Josephine Taylor’s first novel is a psychologically penetrating and honest read that juxtaposes two women, one Victorian and one modern-day, who suffer from the same debilitating medical condition. In 1866, newlyweds Emily and Arthur Rochdale visit the London office of a physician who proposes a drastic cure for Emily’s chronic gynecological pain. Emily and Arthur are despondent; she can barely function and has withdrawn from society, and he struggles to help her. From boyhood on, Arthur has strived to speak up for those who cannot, but he isn’t sure whether to trust the surgeon and his diagnosis of “hysteria.”

In 2009, a Perth-based academic, Alice Tennant, is struck down by the same disorder, which makes sitting excruciatingly painful and prevents physical intimacy with her older husband, Duncan.

Taylor places readers in the moment with Arthur, Emily, and Alice as they process the pain they all endure and how it changes their outlook on life. An emotional support system can make a big difference. Emily writes letters (which read as believably Victorian) to her sister-in-law, Bea, who provides reassurance and understanding. Alice sees many traditional and alternative medicine practitioners but finds few answers – this hasn’t changed over time – and Duncan’s patience soon wears thin. In researching the history of women’s health, however, Alice taps into a new vein of creativity.

Eye of a Rook dares to travel to uncomfortable places of the flesh and spirit, and does so with lyricism and visceral empathy. It beautifully describes landscapes, like England’s Peak District and the Australian countryside, and the mental respite they offer. Toward the end, the two timelines intersect in an ingenious way. The novel should prove validating for anyone suffering from an invisible illness, and eye-opening for anyone unfamiliar with vulvodynia, which is little-known but not as rare as one would guess.

This novel, for which the author's personal experiences provided source material, was published by Fremantle Press in Australia in 2021; I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review, based on a personal purchase (it's sold in the US as well). In Australia, the price is $32.99 in paperback. Read more about the novel's background in the author's interview for The Nerd Daily.

Josephine Taylor is a speaker at this weekend's Historical Novel Society Australasia virtual conference, which I'm attending, though the time zone differences between here and Sydney meant I wasn't able to attend her session in person. Fortunately, everything is being recorded for viewing over the next few months.

Published on October 23, 2021 06:00

October 18, 2021

A visual preview of the winter 2022 season in historical fiction

Here's my latest seasonal preview of forthcoming historical novels, covering books to be published between January and March next year. I'm featuring 15 titles of personal interest (and I'll be lucky to have time to read them all!), and have aimed to include a range of settings and time periods. They're listed in alpha order by author surname. Will you be adding any to your TBR piles also? Links below go to the books' Goodreads pages.

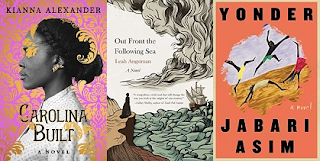

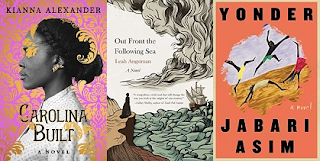

Kianna Alexander's Carolina Built (Gallery, Feb.) is biographical fiction about Josephine Leary, a woman born into enslavement who achieved huge success in the business world as a real estate developer in late 19th-early 20th-century North Carolina. Another American-set historical is Leah Angstman's Out Front the Following Sea (Regal House, Jan.), which follows a young woman accused of witchcraft in 17th-century New England. Yonder by Jabari Asim (Simon & Schuster, Jan.), called "The Water Dancer meets The Prophets" by the publisher, takes place on a plantation in the Southern states in the mid-19th century.

Karen Brooks always incorporates intriguing settings and plots, and her latest, The Good Wife of Bath (William Morrow, Jan.; already out in Australia) retells Chaucer's classic story of pilgrimage from the title character's viewpoint. Danielle Daniel's Daughters of the Deer (Random House Canada, Mar.) has been on my list ever since I saw the publishing deal reported in Publishers Marketplace. Set in New France in the 1600s, it focuses on a Algonquin woman who agrees to marry a French settler in an alliance to save her people. Interestingly, Agatha Christie (and her mysterious 11-day disappearance in 1926) has been the subject of several novels of late. Nina de Gramont's The Christie Affair (St. Martin's, Feb.) delves into the mystery from the perspective of Christie's husband's mistress. Lots of buzz for this one.

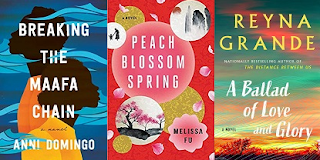

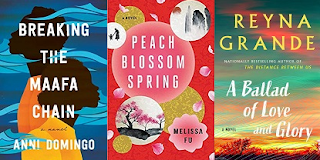

Basing her first novel on the true story of Queen Victoria's Yoruba goddaughter Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Anni Domingo's Breaking the Maafa Chain (Pegasus, Feb.; already out in the UK from Jacaranda Books) traces the separate journeys of two African sisters from their homeland to England and America, countries which have different views on slavery in the mid-19th century. Melissa Fu's debut Peach Blossom Spring (Little, Brown, Mar.) promises to be a moving saga of about three generations of a family in China and America beginning in the 1930s. A Ballad of Love and Glory by Reyna Grande (Atria, Mar.) is described as a "sweeping historical saga," which the title emphasizes; it centers on the unexpected love story between a Mexican healer and an Irish immigrant during the Mexican American War.

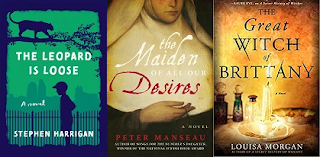

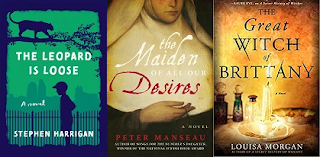

Stephen Harrigan is an excellent prose stylist (his Remember Ben Clayton is a favorite of mine), and his upcoming novel The Leopard Is Loose (Knopf, Feb.), set in 1952 Oklahoma, shows the tumult of the postwar era through a child's eyes. Skipping over the Atlantic to England just after the Black Death, Peter Manseau's The Maiden of All Our Desires (Arcade, Feb.) plunges into the dramas of faith and flesh within a community of nuns. Louisa Morgan's The Secret History of Witches was a word-of-mouth hit, and her newest, The Great Witch of Brittany (Redhook, Feb.) is a prequel beginning in 18th-century Brittany that reveals the backstory of the powerful clan's magical matriarch, Ursule Orchière.

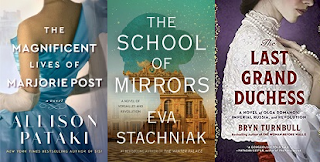

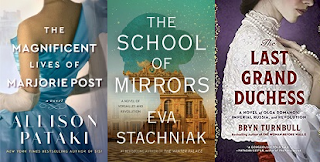

The wide-ranging, glamorous, hard-working 20th-century life of cereal heiress and socialite Marjorie Merriweather Post is depicted in Allison Pataki's The Magnificent Lies of Marjorie Post (Ballantine, Feb.) Eva Stachniak, who most recently chronicled the life of Polish dancer-choreographer Bronislava Nijinska, moves to 18th-century France with The School of Mirrors (William Morrow/Doubleday Canada, Feb.), about the young women selected as potential mistresses for Louis XV. Lastly, The Last Grand Duchess by Bryn Turnbull (MIRA, Feb.) reveals the inner life of Romanov grand duchess Olga, eldest daughter of Nicholas and Alexandra.

Kianna Alexander's Carolina Built (Gallery, Feb.) is biographical fiction about Josephine Leary, a woman born into enslavement who achieved huge success in the business world as a real estate developer in late 19th-early 20th-century North Carolina. Another American-set historical is Leah Angstman's Out Front the Following Sea (Regal House, Jan.), which follows a young woman accused of witchcraft in 17th-century New England. Yonder by Jabari Asim (Simon & Schuster, Jan.), called "The Water Dancer meets The Prophets" by the publisher, takes place on a plantation in the Southern states in the mid-19th century.

Karen Brooks always incorporates intriguing settings and plots, and her latest, The Good Wife of Bath (William Morrow, Jan.; already out in Australia) retells Chaucer's classic story of pilgrimage from the title character's viewpoint. Danielle Daniel's Daughters of the Deer (Random House Canada, Mar.) has been on my list ever since I saw the publishing deal reported in Publishers Marketplace. Set in New France in the 1600s, it focuses on a Algonquin woman who agrees to marry a French settler in an alliance to save her people. Interestingly, Agatha Christie (and her mysterious 11-day disappearance in 1926) has been the subject of several novels of late. Nina de Gramont's The Christie Affair (St. Martin's, Feb.) delves into the mystery from the perspective of Christie's husband's mistress. Lots of buzz for this one.

Basing her first novel on the true story of Queen Victoria's Yoruba goddaughter Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Anni Domingo's Breaking the Maafa Chain (Pegasus, Feb.; already out in the UK from Jacaranda Books) traces the separate journeys of two African sisters from their homeland to England and America, countries which have different views on slavery in the mid-19th century. Melissa Fu's debut Peach Blossom Spring (Little, Brown, Mar.) promises to be a moving saga of about three generations of a family in China and America beginning in the 1930s. A Ballad of Love and Glory by Reyna Grande (Atria, Mar.) is described as a "sweeping historical saga," which the title emphasizes; it centers on the unexpected love story between a Mexican healer and an Irish immigrant during the Mexican American War.

Stephen Harrigan is an excellent prose stylist (his Remember Ben Clayton is a favorite of mine), and his upcoming novel The Leopard Is Loose (Knopf, Feb.), set in 1952 Oklahoma, shows the tumult of the postwar era through a child's eyes. Skipping over the Atlantic to England just after the Black Death, Peter Manseau's The Maiden of All Our Desires (Arcade, Feb.) plunges into the dramas of faith and flesh within a community of nuns. Louisa Morgan's The Secret History of Witches was a word-of-mouth hit, and her newest, The Great Witch of Brittany (Redhook, Feb.) is a prequel beginning in 18th-century Brittany that reveals the backstory of the powerful clan's magical matriarch, Ursule Orchière.

The wide-ranging, glamorous, hard-working 20th-century life of cereal heiress and socialite Marjorie Merriweather Post is depicted in Allison Pataki's The Magnificent Lies of Marjorie Post (Ballantine, Feb.) Eva Stachniak, who most recently chronicled the life of Polish dancer-choreographer Bronislava Nijinska, moves to 18th-century France with The School of Mirrors (William Morrow/Doubleday Canada, Feb.), about the young women selected as potential mistresses for Louis XV. Lastly, The Last Grand Duchess by Bryn Turnbull (MIRA, Feb.) reveals the inner life of Romanov grand duchess Olga, eldest daughter of Nicholas and Alexandra.

Published on October 18, 2021 15:30

October 15, 2021

When I Come Home Again by Caroline Scott, a beautifully written post-WWI novel of mystery, loss, and hope

Caroline Scott’s The Photographer of the Lost (US title The Poppy Wife) is one of my favorite recent novels about WWI, so when I had some free time, her follow-up, When I Came Home Again, rose to the top of my TBR. Like its predecessor, it’s a gorgeously melancholy depiction of the era, evoking the personal and national losses of the Great War and their enduring aftereffects – not just on returning soldiers but on the families left behind.

Caroline Scott’s The Photographer of the Lost (US title The Poppy Wife) is one of my favorite recent novels about WWI, so when I had some free time, her follow-up, When I Came Home Again, rose to the top of my TBR. Like its predecessor, it’s a gorgeously melancholy depiction of the era, evoking the personal and national losses of the Great War and their enduring aftereffects – not just on returning soldiers but on the families left behind. Both are slow-burning mysteries, though atypical ones. There’s no formal detective, just a natural unfolding of events. The Photographer of the Lost has the stronger plot of the two, though this one is still very good.

The story opens in November 1918 in Durham Cathedral. A man is caught desecrating its Galilee chapel by drawing chalk illustrations on the flagstones. Though clearly a former soldier, he has no memory of who he is. The police give him the name “Adam Galilee” and place him into the care of Dr. James Haworth, who brings him to a convalescent hospital in Westmorland called Fellside, in the hopes he’ll recall his name and previous life. It doesn’t work; the trauma he experienced is so terrible that it remains buried.

In 1920, when a newspaper publishes a collection of photographs, including Adam’s, under the strapline “the living unknown warriors,” a parade of women comes forth, all wanting Adam to be their lost loved one.

Three women feel certain he belongs with them. Scott conveys their desperate eagerness to claim Adam as their son, brother, or spouse, and Adam’s panicked reaction since he doesn’t recognize any of them. But who is he? Is it possible none are right? Memories can be unreliable. And James, in wanting to identify Adam, may be pushing him down an incorrect path. James is also facing his own wartime demons, which affect his marriage to Caitlin, a talented potter.

The principal mystery involves Adam, but because he’s initially a blank slate upon which others project their hopes, the women’s tragic stories resonate more strongly. There’s Celia, who refuses to believe her son Robert will never come home. Anna hopes for a fresh start with her missing, troubled husband, Mark. Lucy was left to raise her brother’s children after he failed to return from France and resents her stifling existence. Caitlin is the only woman Adam feels comfortable with, since she doesn’t want anything from him except friendship.

Over time, Adam’s character gets colored in. He’s a gentle soul with artistic talent who knows the Latin names for plants, but not his own name, or the name of the woman whose image he draws.

At the end, some clues are left unexplained, which bothered me a bit. But I did appreciate how well the novel transported me to the post-WWI era, and into the minds of men and women searching for an exit to the holding patterns of their lives.

When I Come Home Again was published by Simon & Schuster UK in 2020 (I read it from a personal copy I purchased on Kindle).

Published on October 15, 2021 08:58

October 10, 2021

Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers unveils the hidden lives of ordinary people in '50s Britain

Can Gretchen Tilbury’s tale about her 10-year-old daughter be true, and if so, how is it scientifically possible?

Can Gretchen Tilbury’s tale about her 10-year-old daughter be true, and if so, how is it scientifically possible? In 1957, reporter Jean Swinney, pushing 40, has a tedious home life caring for her irritable, reclusive mother. In investigating a claim of parthenogenesis, a virgin birth, for her suburban London newspaper, Jean sees her world unexpectedly transformed.

Surprisingly, she finds no apparent holes in Gretchen’s story. Gretchen had been bedridden in a clinic alongside others when Margaret was conceived. As mother and daughter undergo laboratory tests to prove or debunk the hypothesis, Jean’s intrinsic loneliness leads her to respond to the Tilburys’ friendly overtures.

Margaret is a charming girl, and Howard, Gretchen’s older husband, has a disarming manner that attracts Jean. As Jean’s personal and professional circles become enmeshed, the plot takes dramatic, even shocking turns.

British novelist Chambers penetrates the secret hopes and passionate inner lives of ordinary working people throughout her gripping novel, while its locked-room-style medical mystery calls to mind Emma Donoghue’s The Wonder (2016). The characters provoke so much empathy, readers may have trouble remembering that they’re fictional.

Small Pleasures will debut in the US on Tuesday this week; the publisher is Custom House, a HarperCollins imprint. In the UK, where it's been out since last July, it was longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction and was a breakout hit. I reviewed it for Booklist's September 1 issue from an Edelweiss e-copy.

I thought about this book for days after I finished and wasn't able to read anything else during that time. If you've read it, you'll likely understand why; I'll say no more!

Published on October 10, 2021 07:11

October 5, 2021

Historical Research: A Many-Faceted Jewel, an essay by Catherine Gentile, author of Sunday's Orphan

Catherine Gentile's Sunday's Orphan, a novel of a woman's self-discovery and family history set in 1930s Jim Crow-era Georgia, was published in September. I'm pleased to welcome the author here today for a post about her research.

~

Historical Research: A Many-Faceted JewelCatherine Gentile

The historical fiction of Pulitzer Prize winner Edward P. Jones, The Known World, inspired me to fulfill my desire to write about the complexities of life during 1930. I envisioned a novel set on a plantation on a fictional island town off the coast of Georgia. Little did I realize the scope and depth of research needed to support the characters who would live in that island town, from the weather, topology, flora, and fauna, to the modes of transportation, the embracing issues of politics and religion, and squirmy birthing and funeral practices—I researched every detail. As painstaking a process as it was, I loved every second!

The historical fiction of Pulitzer Prize winner Edward P. Jones, The Known World, inspired me to fulfill my desire to write about the complexities of life during 1930. I envisioned a novel set on a plantation on a fictional island town off the coast of Georgia. Little did I realize the scope and depth of research needed to support the characters who would live in that island town, from the weather, topology, flora, and fauna, to the modes of transportation, the embracing issues of politics and religion, and squirmy birthing and funeral practices—I researched every detail. As painstaking a process as it was, I loved every second!

To gain a deeper appreciation for the layout and management of Southern plantations, I visited plantations in Louisiana, South Carolina, and Georgia. I then designed Mearswood Plantation and located the cabins, barns, and outbuildings, pastures, and gardens within a sketch. This primitive drawing served as an invaluable map that helped me maintain consistency of locations and positions of structures relative to one another.

Shack in woods, side view

Shack in woods, side view

I wasn’t sure what the simple cabins and privies on the plantation looked like. Fortunately, while hiking in Georgia, taking photos of the flora and fauna within the marshes, I came upon the serendipitous answer: cabins in varying stages of decay. These pretty much substantiated my imaginings, but the fact that they were situated on raised posts was a revelation.

Shack in woods, front view

Shack in woods, front view

I didn’t have the same luck with privies, thank goodness! Again, I resorted to my primitive sketching ability, which gave me enough information to address the privies that appeared in the novel more often than I had anticipated!

Hiking proved invaluable from recreational and research points of view, as I gained understanding of the poor soil quality, the variety of trees, the construction of shell middens, and intensity of forest growth. The abundance of Old Man’s Beard, aka Spanish Moss, became an important detail for the novel. Naughty as this was, I confess to secreting samples of pine straw and other plants home for me to study.

Shell-packed dirt road in the woods

Shell-packed dirt road in the woods

The idyllic nature of hiking found its polar opposite in the unsettling research on Jim Crow “law” and its soul-crushing abuses. Try as I did to circumvent incorporating such information in my novel, fellow authors in my writing group argued that they were essential to the story. Gilbert King’s The Devil in the Grove helped me adjust my attitude and hence, set the stage for writing those chapters. I needn’t go into detail here. Suffice it to say, online offerings, memorials to victims of lynching, helped in this regard. Acts of hanging and reports of the celebratory atmosphere—bands, parties, picnics—surrounding these acts captured the cruelty. Postcards of individuals on whom these acts were committed captured its heart-searing insensitivity. As much as I loved research, working these pieces of human history into Sunday’s Orphan was dispiriting.

Later, during an antiquing trip, the research gods smiled on me when I happened across a 1927 copy of Successful Farming. This treasure trove contained articles on farming, raising livestock and children, putting up preserves, and farm finances. Loaded with ads, these primarily black and white pictures provided close ups of furnishings, kitchen tools and appliances, and gave me a peek at work-a-day clothing and their more fashion conscious cousins, hats and dresses. And yes, I bought that copy of Successful Farming.

Marsh's edge

Marsh's edge

I located internet photos depicting the scandalous decrease in the post Roaring Twenties length of women’s skirts, and incorporated this small, but telling detail into Sunday’s Orphan, when a fashionable Bostonian visits Mearswood Plantation in Georgia and relinquishes her city clothing for hand-sewn country attire. Fascinating sociological details such as women’s horrified responses to manufactured undergarments replacing those that were hand-made appeared as well, but those had to be saved for another story.

Librarians were generous in helping me locate information. One knowledgeable research librarian at Tybee Library plied me with stacks of resources containing answers to questions I had amassed while drafting Sunday’s Orphan. Another librarian loaned me audio tapes of interviews conducted with rural Southern midwives, describing their practices and experiences.

Catherine Gentile

Catherine Gentile

(credit: Lesley McVane)There, however, was little documentation to prove that people living in 1930 actually farmed the scrappy soil on Georgia’s barrier islands. I couldn’t find the answer in the library, and residents with whom I spoke weren’t sure. Farming played an important role in Sunday’s Orphan, and I wanted to be sure it had, in fact, occurred on the barrier islands. Walking through a local cemetery, I considered my authorial options should this piece be untrue. Again, the research gods smiled on me: there, in Tybee Island Memorial Cemetery, was the headstone of Nameless Brown, husband, father, and farmer.

Research deepened my experience of Georgia; now, I’m anxious to draft my next work of historical fiction. Learn more at www.catherinegentile.com.

~

Historical Research: A Many-Faceted JewelCatherine Gentile

The historical fiction of Pulitzer Prize winner Edward P. Jones, The Known World, inspired me to fulfill my desire to write about the complexities of life during 1930. I envisioned a novel set on a plantation on a fictional island town off the coast of Georgia. Little did I realize the scope and depth of research needed to support the characters who would live in that island town, from the weather, topology, flora, and fauna, to the modes of transportation, the embracing issues of politics and religion, and squirmy birthing and funeral practices—I researched every detail. As painstaking a process as it was, I loved every second!

The historical fiction of Pulitzer Prize winner Edward P. Jones, The Known World, inspired me to fulfill my desire to write about the complexities of life during 1930. I envisioned a novel set on a plantation on a fictional island town off the coast of Georgia. Little did I realize the scope and depth of research needed to support the characters who would live in that island town, from the weather, topology, flora, and fauna, to the modes of transportation, the embracing issues of politics and religion, and squirmy birthing and funeral practices—I researched every detail. As painstaking a process as it was, I loved every second! To gain a deeper appreciation for the layout and management of Southern plantations, I visited plantations in Louisiana, South Carolina, and Georgia. I then designed Mearswood Plantation and located the cabins, barns, and outbuildings, pastures, and gardens within a sketch. This primitive drawing served as an invaluable map that helped me maintain consistency of locations and positions of structures relative to one another.

Shack in woods, side view

Shack in woods, side viewI wasn’t sure what the simple cabins and privies on the plantation looked like. Fortunately, while hiking in Georgia, taking photos of the flora and fauna within the marshes, I came upon the serendipitous answer: cabins in varying stages of decay. These pretty much substantiated my imaginings, but the fact that they were situated on raised posts was a revelation.

Shack in woods, front view

Shack in woods, front viewI didn’t have the same luck with privies, thank goodness! Again, I resorted to my primitive sketching ability, which gave me enough information to address the privies that appeared in the novel more often than I had anticipated!

Hiking proved invaluable from recreational and research points of view, as I gained understanding of the poor soil quality, the variety of trees, the construction of shell middens, and intensity of forest growth. The abundance of Old Man’s Beard, aka Spanish Moss, became an important detail for the novel. Naughty as this was, I confess to secreting samples of pine straw and other plants home for me to study.

Shell-packed dirt road in the woods

Shell-packed dirt road in the woodsThe idyllic nature of hiking found its polar opposite in the unsettling research on Jim Crow “law” and its soul-crushing abuses. Try as I did to circumvent incorporating such information in my novel, fellow authors in my writing group argued that they were essential to the story. Gilbert King’s The Devil in the Grove helped me adjust my attitude and hence, set the stage for writing those chapters. I needn’t go into detail here. Suffice it to say, online offerings, memorials to victims of lynching, helped in this regard. Acts of hanging and reports of the celebratory atmosphere—bands, parties, picnics—surrounding these acts captured the cruelty. Postcards of individuals on whom these acts were committed captured its heart-searing insensitivity. As much as I loved research, working these pieces of human history into Sunday’s Orphan was dispiriting.

Later, during an antiquing trip, the research gods smiled on me when I happened across a 1927 copy of Successful Farming. This treasure trove contained articles on farming, raising livestock and children, putting up preserves, and farm finances. Loaded with ads, these primarily black and white pictures provided close ups of furnishings, kitchen tools and appliances, and gave me a peek at work-a-day clothing and their more fashion conscious cousins, hats and dresses. And yes, I bought that copy of Successful Farming.

Marsh's edge

Marsh's edgeI located internet photos depicting the scandalous decrease in the post Roaring Twenties length of women’s skirts, and incorporated this small, but telling detail into Sunday’s Orphan, when a fashionable Bostonian visits Mearswood Plantation in Georgia and relinquishes her city clothing for hand-sewn country attire. Fascinating sociological details such as women’s horrified responses to manufactured undergarments replacing those that were hand-made appeared as well, but those had to be saved for another story.

Librarians were generous in helping me locate information. One knowledgeable research librarian at Tybee Library plied me with stacks of resources containing answers to questions I had amassed while drafting Sunday’s Orphan. Another librarian loaned me audio tapes of interviews conducted with rural Southern midwives, describing their practices and experiences.

Catherine Gentile

Catherine Gentile(credit: Lesley McVane)There, however, was little documentation to prove that people living in 1930 actually farmed the scrappy soil on Georgia’s barrier islands. I couldn’t find the answer in the library, and residents with whom I spoke weren’t sure. Farming played an important role in Sunday’s Orphan, and I wanted to be sure it had, in fact, occurred on the barrier islands. Walking through a local cemetery, I considered my authorial options should this piece be untrue. Again, the research gods smiled on me: there, in Tybee Island Memorial Cemetery, was the headstone of Nameless Brown, husband, father, and farmer.

Research deepened my experience of Georgia; now, I’m anxious to draft my next work of historical fiction. Learn more at www.catherinegentile.com.

Published on October 05, 2021 04:00