Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 31

August 19, 2021

Julie Klassen's A Castaway in Cornwall takes a romantic escape to Poldark country

A castaway, the dictionary tells us, is “a person who has been shipwrecked and stranded in an isolated place.”

A castaway, the dictionary tells us, is “a person who has been shipwrecked and stranded in an isolated place.”Both the heroine and hero of Julie Klassen’s historical novel are castaways, literally or figuratively. With its picturesque backdrop of North Cornwall’s rocky shores during the Napoleonic Wars, it’s tailor-made to draw in Poldark fans, though the love story is more of a gentle, slow burn than one of smoldering passion.

In 1813, Laura Callaway, a young woman of 23, is a lost soul of sorts. Orphaned as a teenager, she had moved to Cornwall eight years earlier to live with her late aunt’s husband, Matthew Bray. Unfortunately, Matthew’s new wife has never truly accepted Laura as part of the family. As a pastime, Laura wanders along the shoreline, collects objects washed up on the sand after shipwrecks, and tries to identify their rightful owners. After the Kittiwake runs aground off the coast one evening, she guards the life of the survivor of the wreck. He calls himself Alexander Lucas and claims to be from Jersey – but he speaks English with a slight accent, and signs point to something hidden in his background. With Britain at war with France, what could his secret possibly be? And Alex may not, in fact, be the only passenger who survived…

Both Alex and Laura are wholeheartedly good people, and their falling in love, despite the obstacles thrown in their path, is a foregone conclusion. Laura’s principal flaw is that she lets her pride get in the way of getting to know her neighbors. Her discoveries over the course of the book eventually set her to rights and give her a sense of belonging.

A Castaway in Cornwall is a story where the setting is a character in its own right, and it’s the most intriguing and multifaceted one of all. The author establishes a sense of community through her large cast while blending Cornish history and customs credibly into the plot. We learn, for example, about St. Enodoc in Trebetherick, a quaint old church partly buried underneath the dunes, and how its minister (Laura's Uncle Matthew) is lowered via rope through a hatch in the roof in order to conduct services there once a year. There are more authentic Cornish names than you can shake a stick at, and the shipboard action scenes are first-rate; I wouldn’t have minded more of them.

Though marketed as Christian fiction, the biblical content is very light overall. It’s an enjoyable story, though there is one scene toward the end that adheres to genre conventions but made me uneasy, given everything that happened beforehand.

A Castaway in Cornwall was published by Bethany House in December 2020; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Published on August 19, 2021 07:24

August 14, 2021

The Boy King by Janet Wertman examines the short reign of the young Tudor monarch, Edward VI

The six-year reign of Edward VI is often forgotten amid the eventful lives of his fellow Tudor monarchs. With the newest novel in her Seymour saga, Janet Wertman shows why the boy and his era are worth a closer look.

The six-year reign of Edward VI is often forgotten amid the eventful lives of his fellow Tudor monarchs. With the newest novel in her Seymour saga, Janet Wertman shows why the boy and his era are worth a closer look. Born in 1537 as the long-sought male heir to Henry VIII and his third queen, Jane Seymour, who died days later, Edward embodied the hopes not just of his family but of the entire nation. His story in Wertman’s retelling is one of unachieved potential, a theme which Edward himself sadly acknowledges. He knows he’s too young to rule alone.

Spanning from his father’s death in 1547 to his own in 1553, aged fifteen, the novel is pure catnip for fans of Tudor politics – which are made easy to grasp because politics and character are so inextricably woven together. Lonely and overprotected, with the most private aspects of his life governed by ritual (a scene showing how his bed is freshly assembled each night to assure his safety is illuminating for both him and the reader), Edward struggles to discern his advisors’ true motives. They may have England’s best interests at heart, or they could be seeking to consolidate power.

The ongoing rivalry between the Lord Protector – his uncle Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset – and John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, plays out in powerful fashion, and the behavior of Somerset’s irresponsible brother, Tom, teaches Edward a tough lesson. Not even a nine-year-old likes to be caught off guard.

Edward’s viewpoint, shown in close third person, is utterly credible: his yearning to fulfill the promise that his birth foretold, his internal growth as he learns the threats facing his realm and rule, and his longings for aspects of a normal childhood. His insistence on viewing an acrobat’s street performance on his coronation day is meaningful and sad, “the first time since his accession that he had actually done what he wanted instead of what someone else wanted.” Edward’s cascade of emotions while seated on the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, in full view of the large congregation, is magnificent:

“After a joyous time, he caught his breath and his heart returned to normal… The warm oil’s touch on his forehead was a mystical cord binding him to Christ. For a moment he was Christ, all blinding light and pulsating energy. Then the word pulled him back and from that height he tumbled through time, past the other sanctified prophets and rulers, until he was just himself sitting on the holy chair again, a boy straining to hold the heavy regalia upright.”

The Boy King has a serious tone befitting its subject, so the few moments of joy and kindness stand out, such as Edward’s love for his loyal dog and his friendship with Barnaby Fitzpatrick, a baron’s son whose honesty he trusts. Alas, their closeness is used against him.

In counterpoint to Edward’s perspective, Wertman also gives us that of his sister, Mary, a woman in her thirties whose devotion to her mother’s Catholicism is as fervent as Edward’s Protestant beliefs. While his councilors urge lenience with Mary’s religious expression, in the interest of international diplomacy, Edward detests “popish superstition.” Although Edward’s personal story is tragically short, one can’t help but wonder how his intolerance would have affected England in the future, had he lived longer.

The Boy King was independently published in 2020; thanks to the author for the Kindle copy. [Find it on Goodreads]

Published on August 14, 2021 08:19

August 10, 2021

Finding the Tracks of a Scottish Witch, an essay by Nancy Hayes Kilgore, author of Bitter Magic

A big welcome to Nancy Hayes Kilgore, who contributes an essay about her research into the life and times of a historical 17th-century Scotswoman who confessed to performing witchcraft.

~

Finding the Tracks of a Scottish WitchNancy Hayes Kilgore

How do you find the tracks of a 17th-century witch? This was my quest as I traveled to the Highlands of Scotland to research my novel, Bitter Magic.

Bitter Magic is inspired by the true story of Isobel Gowdie, whose witchcraft confession in 1662 is one of the most famous in Scottish history. Famous, partly because of its length – it was recorded verbatim over the course of four weeks – but mostly because of its uniqueness.

Bitter Magic is inspired by the true story of Isobel Gowdie, whose witchcraft confession in 1662 is one of the most famous in Scottish history. Famous, partly because of its length – it was recorded verbatim over the course of four weeks – but mostly because of its uniqueness.

Unlike many witchcraft confessions, which contain similar elements – I made a pact with the devil, I killed someone with a curse, I stopped the milk in my neighbor’s cow – Isobel’s confession veered off significantly from the script that was often fed to and forced out of the victims.

Isobel elaborated upon and embellished her story beyond what her interrogators asked of her, describing what characters looked like and how she felt. She turned herself into a hare or a crow, she said. (The crow became a featured image in my novel.) She talked about leaving her body and flying through the night with the fairies. She knew the fairy queen. “I was in the Downie Hill and got meat there from the queen of fairy, more than I could eat. The queen of fairy is brawlie clothed in whyt linens and in whyt and browne cloathes..."

Isobel knew the devil and was “sore affrighted” of him. Nevertheless, she described having sex with him.

Before I went to Scotland, I spent several years researching and writing drafts of this tale of Isobel Gowdie and her community, including the landed gentry, who were “Covenanters.” These strict Presbyterians believed that “cunning women” like Isobel, peasants who adhered to the old folklore and beliefs, were demons in human form. I was also interested in the Christian women who may have been sympathetic to or protective of the “witches,” like my protagonist, Margaret.

I wanted to find all the places I had researched and written about in my first drafts of Bitter Magic – the castles where some of my characters lived, the “fermtoun” where Isobel lived, the Auldearn Church where she met the devil, but most of all I wanted to find the Downie Hill, Isobel’s sacred place. I wanted to climb up and stand on top of it. Would I find a special vibrational energy there? Would I sense the “Otherworld? From my research I had learned that The Downie Hill was an actual hill and that it is still where Isobel said it was, between Auldearn and Brodie. This was where the fairy queen lived, she said, and where she could enter the Otherworld of fairies, elves, and other beings. The Downie Hill would open and she would go in to see and visit them.

The Downie Hill, in actuality, is a mound, one of a number of mounds or hillocks that are now assumed to be Iron Age dun forts (750 BC – 43 AD). These were ancient dwellings or forts that scholars believe, over time, became covered with earth and buried. Some of them have been excavated to reveal artifacts, but many, like the Downie Hill, have not.

In Isobel’s time, the 1660s, the mounds were known as fairy mounds. Most people, even the church and ruling class, believed that these mounds were where the fairies were active and that magic happened there. Thus, they were, and still are, called fairy mounds.

Great Britain has a very handy mapping system, the Ordnance Survey, that plots almost every hill and valley as well as ancient sites. On the OS map, I located the Downie Hill. But finding it on the ground was not so easy.

I drove around the neighboring roads until suddenly I spied, across a wide expanse of field and almost hidden behind a thicket of trees, an enormous mound. A cone-shaped hill thrusting up out of the flat land that I would have missed if the sun hadn’t been shining directly on it. I stopped at the farmhouse across the road and knocked on the door. A friendly young man at the door said, oh yes, that’s an old hill fort. And it was okay if I walked over to it. I trudged the half mile across the stubbly field, and when I came to the tree-covered hill, discovered that the area around it was too overgrown with ferns and brush to get through.

When I told my new friend Morag about my find, she was as enthusiastic as I to visit the Downie Hill, and on this sunny July day we set out on our adventure in her little sports car with the top down. We found another path from a roadside lay-by, and began to hike in. Now we could see the hill, but the terrain was uneven and covered with six-foot ferns – bracken. I had reservations about pushing through, but Morag, a more intrepid hiker than I, said, “Of course we can forge through all of that,” and I followed her up the hill. At the top the bracken was as thick as below, but we found a small clearing and stood amidst the ferns.

A sudden quiet fell. No bagpipes playing from the clouds, no wild men in kilts, and not even flickering fairies. The sun sparkled and the ferns shone green and radiant, and we were drawn inward, to a stillness in tune with this place.

I looked down. On the ground beside me was a crow feather.

I picked it up, took it home, and tacked it on the wall above my writing desk.

~

Nancy Hayes Kilgore

Nancy Hayes Kilgore

(credit: Kathy Tarantola)Nancy Hayes Kilgore, winner of the Vermont Writers Prize, is the author of two other novels, Wild Mountain (Green Writers Press, 2017,) and Sea Level (RCWMS, 2011,) a ForeWord Reviews Book of the Year. She has published in a She Writes Press anthology, in Bloodroot Literary Magazine, Vermont Magazine, The Bottle Imp, and on Vermont Public Radio.

Nancy is a graduate of the Radcliffe Writing Seminars and holds a Master of Divinity degree and a Doctorate in Pastoral Counseling. She is a former parish pastor, a psychotherapist, a writing coach, and leads workshops on creative writing and spirituality. Find her online at nancykilgore.com.

~

Finding the Tracks of a Scottish WitchNancy Hayes Kilgore

How do you find the tracks of a 17th-century witch? This was my quest as I traveled to the Highlands of Scotland to research my novel, Bitter Magic.

Bitter Magic is inspired by the true story of Isobel Gowdie, whose witchcraft confession in 1662 is one of the most famous in Scottish history. Famous, partly because of its length – it was recorded verbatim over the course of four weeks – but mostly because of its uniqueness.

Bitter Magic is inspired by the true story of Isobel Gowdie, whose witchcraft confession in 1662 is one of the most famous in Scottish history. Famous, partly because of its length – it was recorded verbatim over the course of four weeks – but mostly because of its uniqueness. Unlike many witchcraft confessions, which contain similar elements – I made a pact with the devil, I killed someone with a curse, I stopped the milk in my neighbor’s cow – Isobel’s confession veered off significantly from the script that was often fed to and forced out of the victims.

Isobel elaborated upon and embellished her story beyond what her interrogators asked of her, describing what characters looked like and how she felt. She turned herself into a hare or a crow, she said. (The crow became a featured image in my novel.) She talked about leaving her body and flying through the night with the fairies. She knew the fairy queen. “I was in the Downie Hill and got meat there from the queen of fairy, more than I could eat. The queen of fairy is brawlie clothed in whyt linens and in whyt and browne cloathes..."

Isobel knew the devil and was “sore affrighted” of him. Nevertheless, she described having sex with him.

Before I went to Scotland, I spent several years researching and writing drafts of this tale of Isobel Gowdie and her community, including the landed gentry, who were “Covenanters.” These strict Presbyterians believed that “cunning women” like Isobel, peasants who adhered to the old folklore and beliefs, were demons in human form. I was also interested in the Christian women who may have been sympathetic to or protective of the “witches,” like my protagonist, Margaret.

I wanted to find all the places I had researched and written about in my first drafts of Bitter Magic – the castles where some of my characters lived, the “fermtoun” where Isobel lived, the Auldearn Church where she met the devil, but most of all I wanted to find the Downie Hill, Isobel’s sacred place. I wanted to climb up and stand on top of it. Would I find a special vibrational energy there? Would I sense the “Otherworld? From my research I had learned that The Downie Hill was an actual hill and that it is still where Isobel said it was, between Auldearn and Brodie. This was where the fairy queen lived, she said, and where she could enter the Otherworld of fairies, elves, and other beings. The Downie Hill would open and she would go in to see and visit them.

The Downie Hill, in actuality, is a mound, one of a number of mounds or hillocks that are now assumed to be Iron Age dun forts (750 BC – 43 AD). These were ancient dwellings or forts that scholars believe, over time, became covered with earth and buried. Some of them have been excavated to reveal artifacts, but many, like the Downie Hill, have not.

In Isobel’s time, the 1660s, the mounds were known as fairy mounds. Most people, even the church and ruling class, believed that these mounds were where the fairies were active and that magic happened there. Thus, they were, and still are, called fairy mounds.

Great Britain has a very handy mapping system, the Ordnance Survey, that plots almost every hill and valley as well as ancient sites. On the OS map, I located the Downie Hill. But finding it on the ground was not so easy.

I drove around the neighboring roads until suddenly I spied, across a wide expanse of field and almost hidden behind a thicket of trees, an enormous mound. A cone-shaped hill thrusting up out of the flat land that I would have missed if the sun hadn’t been shining directly on it. I stopped at the farmhouse across the road and knocked on the door. A friendly young man at the door said, oh yes, that’s an old hill fort. And it was okay if I walked over to it. I trudged the half mile across the stubbly field, and when I came to the tree-covered hill, discovered that the area around it was too overgrown with ferns and brush to get through.

When I told my new friend Morag about my find, she was as enthusiastic as I to visit the Downie Hill, and on this sunny July day we set out on our adventure in her little sports car with the top down. We found another path from a roadside lay-by, and began to hike in. Now we could see the hill, but the terrain was uneven and covered with six-foot ferns – bracken. I had reservations about pushing through, but Morag, a more intrepid hiker than I, said, “Of course we can forge through all of that,” and I followed her up the hill. At the top the bracken was as thick as below, but we found a small clearing and stood amidst the ferns.

A sudden quiet fell. No bagpipes playing from the clouds, no wild men in kilts, and not even flickering fairies. The sun sparkled and the ferns shone green and radiant, and we were drawn inward, to a stillness in tune with this place.

I looked down. On the ground beside me was a crow feather.

I picked it up, took it home, and tacked it on the wall above my writing desk.

~

Nancy Hayes Kilgore

Nancy Hayes Kilgore(credit: Kathy Tarantola)Nancy Hayes Kilgore, winner of the Vermont Writers Prize, is the author of two other novels, Wild Mountain (Green Writers Press, 2017,) and Sea Level (RCWMS, 2011,) a ForeWord Reviews Book of the Year. She has published in a She Writes Press anthology, in Bloodroot Literary Magazine, Vermont Magazine, The Bottle Imp, and on Vermont Public Radio.

Nancy is a graduate of the Radcliffe Writing Seminars and holds a Master of Divinity degree and a Doctorate in Pastoral Counseling. She is a former parish pastor, a psychotherapist, a writing coach, and leads workshops on creative writing and spirituality. Find her online at nancykilgore.com.

Published on August 10, 2021 05:00

August 8, 2021

A gallery of twelve new ancient and medieval historical novels

While the WWII trend in historical fiction is still riding high, novels set in the more distant past still exist and have a strong readership base. Here are a dozen new and upcoming novels taking place in ancient and medieval times, all of which I've either read or have my eye on. (On a personal note, I'm typing this, or trying to, while the newest addition to the household, a formerly stray tortie named Cocoa, is attacking my legs and climbing all over my desk and keyboard. It's a challenge!) On to the books...

In From the Ashes, Melissa Addey presents a colorful behind-the-scenes view of the Roman Colosseum's construction and grand opening through the eyes of an enslaved young woman, Althea, who must take charge after her master is subsumed with grief following the loss of his family during the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. I've read this one and found it highly entertaining and moving, especially the scenes showing the startling disappearance of Pompeii. Letterpress Books, Feb. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Karen Brooks always chooses singular heroines and intriguing historical periods for her fiction. The Good Wife of Bath, set in 14th-century England, promises to cast new light on the well-known, multi-married character from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. HQ Australia, July 2021; it will be published in the US next winter. [see on Goodreads]

Setting her debut in thirteenth-century Mongolia, F. M. Deemyad recounts the story of three princesses from different lands whose fates were closely linked to the empire of Genghis Khan. History Through Fiction, March 2021. [see on Goodreads]

The protagonist of Annie Garthwaite's debut novel is Cecily Neville, future matriarch of the Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet family, as she seizes the opportunity to see her political fortunes rise during England's War of the Roses. Viking UK, July 2021. [see on Goodreads]

There's been considerable buzz about Lauren Groff's Matrix, which retells the story of Marie de France, a rebellious young woman of seventeen when she's exiled to England to take charge of a faltering abbey of nuns in the late 12th century. Riverhead, Sept. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

In Elodie Harper's new novel, the "wolf den" of the title is the lupanar (brothel) in ancient Pompeii; this is an absorbing, fast-paced story recounting the lives of the women who live and work there, and it does so without delving into salaciousness. Yes, another novel on this list that's set in that well-known, tragic city. The eruption of Vesuvius is still a few years in the future for this book, which is first in a series. Head of Zeus, May 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Johnson's romantic novel features two strong-willed leads: an heiress from Carthage and a Roman centurion, whose lives come together during the time of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps in 218 BCE. Bellastoria, April 2021. [see on Goodreads]

I enjoyed Fortune's Child, first in James Conroyd Martin's two-book series about Empress Theodora in 6th-century Byzantium, and am looking forward to reading this sequel, which centers on her years as empress as opposed to her earlier life. Hussar Quill Press, June 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Carol McGrath is skilled at bringing forth the personalities of lesser-known medieval royal women. Her subject in The Damask Rose, second in her She-Wolves trilogy, is Eleanor of Castile, queen of Edward I and prominent businesswoman in the thirteenth century. Headline Accent, April 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Christina of Markyate, not her birth name, was a 12th-century English anchoress from a wealthy family who denied herself worldly pleasures and dedicated herself to a spiritual life. Having just finished Mary Sharratt's Revelations, I'm intrigued by Ruth Mohrman's novel about an earlier medieval mystic; the author has a doctorate in medieval literature. Cadoc Publishing, Jan. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

I've been looking forward to Anne O'Brien's novel about the 15th-century Pastons for some time. The Royal Game follows three women from this famous English family during their surprising rise to power. HQ, September 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Last but not least (the books in this post are alphabetized by author surname), The Moon God's Wife is also set the furthest back in time: the setting is Mesopotamia of 2300 BCE. Shauna Roberts' novel imagines the story of Enheduanna, a high priestess of the goddess Inanna whose name has come down in history as the first recorded poet. Nicobar Press, July 2021.

And here's Miss Cocoa, posing on a historical fiction book pile which has since been dismantled because I bought more shelves. Happy International Cat Day from both of us!

In From the Ashes, Melissa Addey presents a colorful behind-the-scenes view of the Roman Colosseum's construction and grand opening through the eyes of an enslaved young woman, Althea, who must take charge after her master is subsumed with grief following the loss of his family during the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. I've read this one and found it highly entertaining and moving, especially the scenes showing the startling disappearance of Pompeii. Letterpress Books, Feb. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Karen Brooks always chooses singular heroines and intriguing historical periods for her fiction. The Good Wife of Bath, set in 14th-century England, promises to cast new light on the well-known, multi-married character from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. HQ Australia, July 2021; it will be published in the US next winter. [see on Goodreads]

Setting her debut in thirteenth-century Mongolia, F. M. Deemyad recounts the story of three princesses from different lands whose fates were closely linked to the empire of Genghis Khan. History Through Fiction, March 2021. [see on Goodreads]

The protagonist of Annie Garthwaite's debut novel is Cecily Neville, future matriarch of the Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet family, as she seizes the opportunity to see her political fortunes rise during England's War of the Roses. Viking UK, July 2021. [see on Goodreads]

There's been considerable buzz about Lauren Groff's Matrix, which retells the story of Marie de France, a rebellious young woman of seventeen when she's exiled to England to take charge of a faltering abbey of nuns in the late 12th century. Riverhead, Sept. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

In Elodie Harper's new novel, the "wolf den" of the title is the lupanar (brothel) in ancient Pompeii; this is an absorbing, fast-paced story recounting the lives of the women who live and work there, and it does so without delving into salaciousness. Yes, another novel on this list that's set in that well-known, tragic city. The eruption of Vesuvius is still a few years in the future for this book, which is first in a series. Head of Zeus, May 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Johnson's romantic novel features two strong-willed leads: an heiress from Carthage and a Roman centurion, whose lives come together during the time of Hannibal's crossing of the Alps in 218 BCE. Bellastoria, April 2021. [see on Goodreads]

I enjoyed Fortune's Child, first in James Conroyd Martin's two-book series about Empress Theodora in 6th-century Byzantium, and am looking forward to reading this sequel, which centers on her years as empress as opposed to her earlier life. Hussar Quill Press, June 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Carol McGrath is skilled at bringing forth the personalities of lesser-known medieval royal women. Her subject in The Damask Rose, second in her She-Wolves trilogy, is Eleanor of Castile, queen of Edward I and prominent businesswoman in the thirteenth century. Headline Accent, April 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Christina of Markyate, not her birth name, was a 12th-century English anchoress from a wealthy family who denied herself worldly pleasures and dedicated herself to a spiritual life. Having just finished Mary Sharratt's Revelations, I'm intrigued by Ruth Mohrman's novel about an earlier medieval mystic; the author has a doctorate in medieval literature. Cadoc Publishing, Jan. 2021. [see on Goodreads]

I've been looking forward to Anne O'Brien's novel about the 15th-century Pastons for some time. The Royal Game follows three women from this famous English family during their surprising rise to power. HQ, September 2021. [see on Goodreads]

Last but not least (the books in this post are alphabetized by author surname), The Moon God's Wife is also set the furthest back in time: the setting is Mesopotamia of 2300 BCE. Shauna Roberts' novel imagines the story of Enheduanna, a high priestess of the goddess Inanna whose name has come down in history as the first recorded poet. Nicobar Press, July 2021.

And here's Miss Cocoa, posing on a historical fiction book pile which has since been dismantled because I bought more shelves. Happy International Cat Day from both of us!

Published on August 08, 2021 11:00

August 4, 2021

The Bohemians by Jasmin Darznik, a shimmering portrait of Dorothea Lange's early years in San Francisco

In her second novel, Darznik presents a shimmering portrait of little-known histories: that of an iconic American photographer, a culture, and a city, all at a time of pivotal transformation.

In her second novel, Darznik presents a shimmering portrait of little-known histories: that of an iconic American photographer, a culture, and a city, all at a time of pivotal transformation. In May 1918, 22-year-old Dorothea “Dorrie” Lange arrives in San Francisco, full of ambition and dreams. Almost immediately, she’s robbed of her savings and forced to hock her beloved Graflex camera to survive. Through her tight friendship with the effervescent Caroline Lee, a Chinese American woman who speaks unaccented English and wears her own beautifully tailored clothing, Dorrie gets introduced to Monkey Block, a four-story structure that withstood the 1906 fire and earthquake and hosts an enclave of bohemians: talented and freewheeling artists, writers, and performers.

Following months of hard work, Dorrie opens her own portrait studio, with Caroline as her assistant, and weighs pursuing a relationship with Western painter Maynard Dixon. The story compellingly narrates her journey as she learns to observe places and people with a candid eye and present them as they wish to be seen.

“What had struck me most about San Francisco so far wasn’t the newness of the place—that I’d expected—but the absence of the past,” Dorrie relates. In many ways, San Francisco seems to be a city where difference is celebrated, but it treats its Chinese residents abominably and doesn’t acknowledge the incongruity; Caroline has developed a tough exterior to protect against internal pain.

As a character, Caroline has a basis in history (Lange did work alongside a Chinese woman), and her personality as imagined by Darznik is deeply multifaceted and unforgettable. Donaldina Cameron and Consuelo Kanaga are among other real-life secondary figures whose courageous lives are worth heralding.

With its themes of female self-invention and empowerment, xenophobia, and people’s enforced separation during the Spanish flu pandemic, readers will find this novel uncannily relevant for today’s world.

The Bohemians was published by Ballantine this year, and I'd reviewed it initially for August's Historical Novels Review.

Published on August 04, 2021 15:51

July 29, 2021

Revelations by Mary Sharratt illuminates the remarkable life of medieval English mystic Margery Kempe

“My story is not a straightforward one. Women’s stories never are.”

“My story is not a straightforward one. Women’s stories never are.” Margery Kempe, born in the small town of Bishop’s Lynn in Norfolk circa 1373, was a woman who confounded and transformed her medieval world. Married to a much older man, she left her family life behind after bearing fourteen children, taking a vow of celibacy and choosing to pursue a spiritual path.

Following her first pregnancy, she had suffered a mental breakdown and was brought out of it after seeing a radiant vision of Christ which instilled her with a feeling of divine love. Later, as a middle-aged woman, after receiving support and understanding from the anchoress Julian of Norwich, Kempe took a pilgrimage route to the Holy Land and later to Santiago de Compostela. Toward the end of her life, she composed a book thought to be the first English-language autobiography.

Mary Sharratt’s Revelations brings us acutely into the interior life and outward experiences of Margery Kempe, who narrates her story in the first person. It’s a wonderful evocation of an extraordinary figure and the medieval mindset in general. The author is an eloquent chronicler of historical women’s thorny paths to self-fulfillment, and Margery faces significant obstacles on her journey, as a sole female disrupting the gender status quo, and traveling through a world designed for men.

“A questing soul with a hungry mind,” Margery challenges sumptuary laws by dressing in white, as her visions direct her to, and narrowly avoids convictions of heresy at a time when Lollards – followers of John Wycliffe, who translated the Bible into English – are burned at the stake. On her wanderings throughout Europe, Margery sees many strange and wondrous sights (the landscapes are beautifully described), comes into the company of other travelers, and must quickly decide how much she can trust them. Trouble accompanies her everywhere. She remains a sympathetic figure, and at the same time, it’s clear how some of her actions and beliefs are incomprehensible to those around her.

Revelations is an illuminating read for anyone interested in stepping back into a long-ago time and envisioning its main character’s life and accomplishments. Though both are separate stories, it makes for a nice pairing with the author’s earlier novel Illuminations, about Hildegard of Bingen.

Revelations was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt earlier this year (I read it from a NetGalley copy).

Published on July 29, 2021 15:33

July 25, 2021

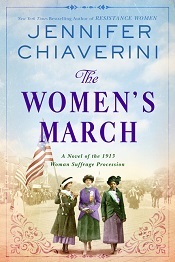

The Women's March by Jennifer Chiaverini relates three women's roles in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession

On March 3, 1913, a day before President Wilson’s inauguration, suffragists marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, to advocate for a constitutional amendment. Chiaverini’s impassioned account pulls readers into the organization, staging, and aftermath of this large, historic event, making the details feel freshly alive.

On March 3, 1913, a day before President Wilson’s inauguration, suffragists marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, to advocate for a constitutional amendment. Chiaverini’s impassioned account pulls readers into the organization, staging, and aftermath of this large, historic event, making the details feel freshly alive. The perspective alternates among three historical figures. Procession co-organizer Alice Paul grows impatient with the national suffrage organization’s focus on state-by-state legislation and pushes for a federal solution. Activist Ida Wells-Barnett, whose background is abundantly illustrated, works to ensure Black women’s rightful place at the voting booth and in the parade. So-called “militant suffragist librarian” Maud Malone challenges politicians to take a stance.

As their plans come together, the story adeptly evokes the obstacles they all face, including Wilson’s opposition, inadequate police protection, and internal divisions about appeasing bigoted Southern white women.

Although some expressions feel overly modern, this politically aware novel about a historic quest for democratic justice compels readers to contemplate everything that has and hasn’t changed over time with voting rights and gender and racial equality.

The Women's March will be published this coming Tuesday by William Morrow; I wrote this review for Booklist's historical fiction issue (5/15/2021). Needless to say, this is a very timely novel. All three women are historical figures, though only Wells-Barnett's name had been known to me previously.

Published on July 25, 2021 11:00

July 23, 2021

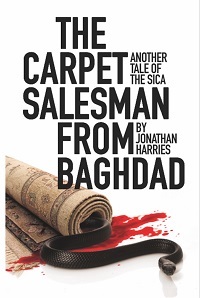

What Happens Next Is Anyone’s Guess, an essay by Jonathan Harries, author of The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad

Today I'm welcoming author Jonathan Harries with an entertaining post about his writing process for what sounds like an equally entertaining historical adventure series.

~

What Happens Next Is Anyone’s Guess

Jonathan Harries

“Come, come,” my wife’s brother said to me. “Surely you plot out your novels. What sort of idiot embarks on a novel without any idea where it will end up?” Well, that’s the gist of what he said. He didn’t use words like “come, come,” but he definitely used “idiot” or it could have been “moron,” I forget. Or perhaps I wasn’t listening.

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad

is my sixth novel, and I’m in the process of putting the finishing touches to my seventh, The Bodyguard of Sarawak. In none have I developed a plotline on the appropriate app nor pinned an outline to a cork board. I have no notebook with character sketches and elaborate ideas for how they’d develop as the novel plods its way to the finish. I’m sure someone who may have picked one up in the past will be making some sort of disparaging sound and thinking, “Well, there you go. That explains a lot.”

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad

is my sixth novel, and I’m in the process of putting the finishing touches to my seventh, The Bodyguard of Sarawak. In none have I developed a plotline on the appropriate app nor pinned an outline to a cork board. I have no notebook with character sketches and elaborate ideas for how they’d develop as the novel plods its way to the finish. I’m sure someone who may have picked one up in the past will be making some sort of disparaging sound and thinking, “Well, there you go. That explains a lot.”

My first novel, Killing Harry Bones, began as a biography of a childhood friend who lived the most colorful—and irresponsible—life imaginable. My initial flirtation with his story happened to coincide with a particularly nasty incident at work involving a despicable swine whose actions I felt were in dire need of redress. I am not by nature a vindictive person, but in his case, I felt a dollop of vengeance was justified. So, I combined the two stories, threw in animal traffickers, poachers, big-game hunters, and ex-Nazis for good measure and began to write with absolutely no idea where the story would end, other than that the bad guys would get their comeuppance. Two other books in the series followed a similar theme.

Now, I imagine the mere mention of the word “theme” means there is some plotting involved. In that respect I suppose there is. All my books have unimaginably awful people getting their just deserts. In the Roger Storm books – Killing Harry Bones, Killing Bobby Fatt, and Killing Valerian Zolotov, trophy hunters and animal traffickers are creatively dispatched by a group of vigilantes hell-bent on saving the planet’s dwindling wildlife. In the Tales of the Sica series—The Tailor of Riga, The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad, and the soon-to-be-completed Bodyguard of Sarawak—a family of assassins who can trace their origin back nearly two thousand years (and just happen to be my own family) take out some of the biggest rotters in history—including Jack the Ripper. The weapon of choice? A millennia-old dagger called a sica, once used in the Jewish uprising against the Romans in around 70 AD.

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad, which launches on July 27, features a distant relative, Elias Smulian-Hasson, who is summoned from Baghdad to Bombay by David Sassoon, the “Rothschild of the East,” on behalf of the Maharaja of Kutch. The year is 1858, soon after the end of the Sepoy Uprising against the British occupiers of India, and the man Elias is tasked with whacking is an English officer whose cruelty towards the Indian survivors of the rebellion are too much even for his own men. What seems like a standard hit at first turns out to be a lot more complicated, and after surviving an ambush in some caves outside of Bombay, Elias pursues his quarry to the southern Kingdom of Travancore. Here, beneath a magnificent temple in amongst troves of gold and jewels and nests of giant cobras, a fierce battle takes place. Will justice be served up like a fiery chicken vindaloo? Aha, you’ll just have to find out.

I don’t believe I knew who would be in the book initially (other than Elias) or who he’d meet or where he’d meet them until shortly before he did. I really like it when my characters make their own decisions as to where they’re going, and I become no more than a chauffeur dropping them off at their destination and picking them up when they’re ready to leave. It’s more fun for me—which is why I write—and I hope more entertaining for my readers.

If you’re one of them, then I appreciate you very much. You may also like to know that every cent I make on all my books go to different animal and wildlife charities.

Bio

Jonathan Harries began his career as a trainee copywriter at Foote, Cone & Belding in South Africa and ended it as Chairman of FCB Worldwide with a few stops in between.

Jonathan Harries began his career as a trainee copywriter at Foote, Cone & Belding in South Africa and ended it as Chairman of FCB Worldwide with a few stops in between.

After winning his first Cannes Lion award, he was offered a job at Grey Advertising in South Africa, where he worked as a copywriter and ended up as CEO at age 29, just before emigrating to the US. Like most immigrants in those days, he started once again from scratch. After a five year stint as Executive Creative Director of Hal Riney in Chicago, he was offered a senior position at FCB. Within ten years, he became the Global Chief Creative Officer and spent the next ten traveling to over 90 countries, racking up 8 million miles on American Airlines alone.

He began writing his first novel, Killing Harry Bones, in the last year of his career and transitioned into becoming a full-time author three years ago, just after retiring from FCB. He’s been writing ever since while doing occasional consulting work for old clients.

Jonathan has a great love of animals, and he and his wife try to go on safari every year. They’ve been lucky enough to visit game reserves in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Tanzania, India, and Sri Lanka.

Blurb

What if my highly dubious story of a two-thousand-year-old family of assassins turned out to be true?

Can you blame a chap for wanting to turn his otherwise humdrum family into a bunch of assassins?

It turns out you can.

I found this out soon after my novel The Tailor of Riga was published, and I received a bunch of beastly emails and threats from incensed family members horrified that I’d portrayed them as the descendants of bloodthirsty hitmen.

Then, out of the blue, a package arrived from a long-lost cousin in Argentina that changed everything.

It was the diary of an unknown ancestor, Elias Smulian-Hasson, summoned from Baghdad to Bombay by the enormously wealthy David Sassoon to take on an assignment for the Maharajah of Kutch.

His mission was to find and kill a British officer responsible for some of the most brutal acts of retribution against Indian survivors of the Great Sepoy Uprising and retrieve a fortune in stolen gemstones. Elias pursues his quarry from Bombay to the Kingdom of Travancore, where the contemptible swine is planning to rob the vaults of the richest temple in the world.

Priceless treasures, mysterious maharajahs, unspeakably evil villains, and the beautiful Mozelle Jacob, a woman Elias will pursue to the ends of the earth, all blend together like a spicy chicken vindaloo in the next saga of the sica.

The Tailor of Riga (see the review at Kirkus), the first book in the Tales of the Sica, is free on Kindle between July 23-27, for anyone interested in getting started with the series.

~

What Happens Next Is Anyone’s Guess

Jonathan Harries

“Come, come,” my wife’s brother said to me. “Surely you plot out your novels. What sort of idiot embarks on a novel without any idea where it will end up?” Well, that’s the gist of what he said. He didn’t use words like “come, come,” but he definitely used “idiot” or it could have been “moron,” I forget. Or perhaps I wasn’t listening.

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad

is my sixth novel, and I’m in the process of putting the finishing touches to my seventh, The Bodyguard of Sarawak. In none have I developed a plotline on the appropriate app nor pinned an outline to a cork board. I have no notebook with character sketches and elaborate ideas for how they’d develop as the novel plods its way to the finish. I’m sure someone who may have picked one up in the past will be making some sort of disparaging sound and thinking, “Well, there you go. That explains a lot.”

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad

is my sixth novel, and I’m in the process of putting the finishing touches to my seventh, The Bodyguard of Sarawak. In none have I developed a plotline on the appropriate app nor pinned an outline to a cork board. I have no notebook with character sketches and elaborate ideas for how they’d develop as the novel plods its way to the finish. I’m sure someone who may have picked one up in the past will be making some sort of disparaging sound and thinking, “Well, there you go. That explains a lot.” My first novel, Killing Harry Bones, began as a biography of a childhood friend who lived the most colorful—and irresponsible—life imaginable. My initial flirtation with his story happened to coincide with a particularly nasty incident at work involving a despicable swine whose actions I felt were in dire need of redress. I am not by nature a vindictive person, but in his case, I felt a dollop of vengeance was justified. So, I combined the two stories, threw in animal traffickers, poachers, big-game hunters, and ex-Nazis for good measure and began to write with absolutely no idea where the story would end, other than that the bad guys would get their comeuppance. Two other books in the series followed a similar theme.

Now, I imagine the mere mention of the word “theme” means there is some plotting involved. In that respect I suppose there is. All my books have unimaginably awful people getting their just deserts. In the Roger Storm books – Killing Harry Bones, Killing Bobby Fatt, and Killing Valerian Zolotov, trophy hunters and animal traffickers are creatively dispatched by a group of vigilantes hell-bent on saving the planet’s dwindling wildlife. In the Tales of the Sica series—The Tailor of Riga, The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad, and the soon-to-be-completed Bodyguard of Sarawak—a family of assassins who can trace their origin back nearly two thousand years (and just happen to be my own family) take out some of the biggest rotters in history—including Jack the Ripper. The weapon of choice? A millennia-old dagger called a sica, once used in the Jewish uprising against the Romans in around 70 AD.

The Carpet Salesman from Baghdad, which launches on July 27, features a distant relative, Elias Smulian-Hasson, who is summoned from Baghdad to Bombay by David Sassoon, the “Rothschild of the East,” on behalf of the Maharaja of Kutch. The year is 1858, soon after the end of the Sepoy Uprising against the British occupiers of India, and the man Elias is tasked with whacking is an English officer whose cruelty towards the Indian survivors of the rebellion are too much even for his own men. What seems like a standard hit at first turns out to be a lot more complicated, and after surviving an ambush in some caves outside of Bombay, Elias pursues his quarry to the southern Kingdom of Travancore. Here, beneath a magnificent temple in amongst troves of gold and jewels and nests of giant cobras, a fierce battle takes place. Will justice be served up like a fiery chicken vindaloo? Aha, you’ll just have to find out.

I don’t believe I knew who would be in the book initially (other than Elias) or who he’d meet or where he’d meet them until shortly before he did. I really like it when my characters make their own decisions as to where they’re going, and I become no more than a chauffeur dropping them off at their destination and picking them up when they’re ready to leave. It’s more fun for me—which is why I write—and I hope more entertaining for my readers.

If you’re one of them, then I appreciate you very much. You may also like to know that every cent I make on all my books go to different animal and wildlife charities.

Bio

Jonathan Harries began his career as a trainee copywriter at Foote, Cone & Belding in South Africa and ended it as Chairman of FCB Worldwide with a few stops in between.

Jonathan Harries began his career as a trainee copywriter at Foote, Cone & Belding in South Africa and ended it as Chairman of FCB Worldwide with a few stops in between. After winning his first Cannes Lion award, he was offered a job at Grey Advertising in South Africa, where he worked as a copywriter and ended up as CEO at age 29, just before emigrating to the US. Like most immigrants in those days, he started once again from scratch. After a five year stint as Executive Creative Director of Hal Riney in Chicago, he was offered a senior position at FCB. Within ten years, he became the Global Chief Creative Officer and spent the next ten traveling to over 90 countries, racking up 8 million miles on American Airlines alone.

He began writing his first novel, Killing Harry Bones, in the last year of his career and transitioned into becoming a full-time author three years ago, just after retiring from FCB. He’s been writing ever since while doing occasional consulting work for old clients.

Jonathan has a great love of animals, and he and his wife try to go on safari every year. They’ve been lucky enough to visit game reserves in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Tanzania, India, and Sri Lanka.

Blurb

What if my highly dubious story of a two-thousand-year-old family of assassins turned out to be true?

Can you blame a chap for wanting to turn his otherwise humdrum family into a bunch of assassins?

It turns out you can.

I found this out soon after my novel The Tailor of Riga was published, and I received a bunch of beastly emails and threats from incensed family members horrified that I’d portrayed them as the descendants of bloodthirsty hitmen.

Then, out of the blue, a package arrived from a long-lost cousin in Argentina that changed everything.

It was the diary of an unknown ancestor, Elias Smulian-Hasson, summoned from Baghdad to Bombay by the enormously wealthy David Sassoon to take on an assignment for the Maharajah of Kutch.

His mission was to find and kill a British officer responsible for some of the most brutal acts of retribution against Indian survivors of the Great Sepoy Uprising and retrieve a fortune in stolen gemstones. Elias pursues his quarry from Bombay to the Kingdom of Travancore, where the contemptible swine is planning to rob the vaults of the richest temple in the world.

Priceless treasures, mysterious maharajahs, unspeakably evil villains, and the beautiful Mozelle Jacob, a woman Elias will pursue to the ends of the earth, all blend together like a spicy chicken vindaloo in the next saga of the sica.

The Tailor of Riga (see the review at Kirkus), the first book in the Tales of the Sica, is free on Kindle between July 23-27, for anyone interested in getting started with the series.

Published on July 23, 2021 05:00

July 18, 2021

The Lengthening Shadow by Liz Harris, a saga set in England and Germany between the world wars

The title of this fast-paced and memorable saga, spanning from 1914 through 1934 in England and Germany, reflects the historical atmosphere: the darkness spreading across the land as the Nazis rise in power and influence, and its chilling effect on the people living beneath it.

The title of this fast-paced and memorable saga, spanning from 1914 through 1934 in England and Germany, reflects the historical atmosphere: the darkness spreading across the land as the Nazis rise in power and influence, and its chilling effect on the people living beneath it. Each volume in the Linford series focuses on different characters. In this third entry, the protagonists are Dorothy Linford, eldest daughter of Joseph, chairman of a prominent London-based building company; and her troubled younger cousin, Louisa. Although some material overlaps with the previous two books, they can all be read independently, and readers familiar with the saga will appreciate how Harris has avoided spoilers for The Dark Horizon (book one) and The Flame Within (book two) – this is very skillfully done!

Serving as a nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment during WWI, Dorothy meets and falls in love with one of her hospital patients, Franz Hartmann, a German internee. Disowned by her parents after their marriage, Dorothy moves with Franz to Germany, where they raise two children. Although she misses England dreadfully, she loves the friendliness and religious amity in their small town, Rundheim.

Through the experiences of the Hartmanns and their neighbors, the novel shows the subtle and, later, overt pressures that ordinary German citizens felt to support Hitler, even against their better judgment. One scene set in 1933, where the view from a mountain hike sweeps from the beauteous natural backdrop to the swastika flags flying from windows below, evokes an unsettling contrast.

As her worry and fear grow, Dorothy has painful decisions to make. Back in England, Louisa, a surly teenager, must reassess her priorities after a major wrongdoing. The characters realistically grow and change, and readers will turn the pages eagerly, hoping for optimistic endings for them all.

The Lengthening Shadow was published by Heywood Press in 2021; I reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review. This is the third and last book in the Linford series. The author's next historical novel, The Darjeeling Inheritance, out in October, is set in India in 1930. I look forward to reading it.

Published on July 18, 2021 08:20

July 14, 2021

Those I Have Lost by Sharon Maas, a wartime saga set in India and Ceylon

Sharon Maas is a novelist whose works I’ve been meaning to read for some time, since her books promised to bring me to places beyond the familiar sites we see so often in historical fiction.

Sharon Maas is a novelist whose works I’ve been meaning to read for some time, since her books promised to bring me to places beyond the familiar sites we see so often in historical fiction. Set in India and Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) before and during the WWII years, Those I Have Lost takes an angle on the war that will be new for many readers. Events are seen through the eyes of Rosalind (Rosie) Scott, who narrates a heartfelt story of coming of age, love, and loss.

A girl of English heritage raised in a household free of cultural prejudice in pre-Partition India, Rosie loses her beloved mother at age 10, and her passing leaves her and her father, an academic scholar, in deep grief. When her late mother’s good friend, Silvia Huxley, pays a visit and asks to take Rosie to live with her family in Ceylon, sharing proof that it’s what her mother would have wanted, her father reluctantly agrees that a girl of Rosie’s age needs a woman’s guiding touch, and lets her go.

The Huxleys, who live in a “bungalow” (really a mansion) at a tea plantation in the green hills near the city of Kandy, are the parents of three boys, the younger two of whom, Andrew and Victor, were Rosie’s playmates on her earlier visits there. Graham, considerably older than his brothers, was a more distant figure and now works as a surgeon. As the war approaches, all three brothers sign on, to their mother’s anguish. Furthermore, Andrew has fallen in forbidden love with Usha, Rosie’s friend and the Huxleys’ cook's daughter, whose marriage had been arranged with another man. And Rosie’s father vanishes after an enigmatic note, leading her to think he’s away in the mountains following an Indian guru. In other words, her personal life and the world around her are in turmoil.

Those I Have Lost is a briskly paced saga enhanced by its colorful, lush setting of mango trees and sweetly scented frangipani and its richly developed secondary characters and social contexts. The viewpoint of Usha’s mother, Sunita, is never seen firsthand, but we sense her thoughts based on her reactions to events, and her admonition to Usha to “remember her place.” The Catholic priest called “Father Bear,” an old friend of Rosie’s family, is refreshingly different from stereotype; he’s a self-described “Christian freethinker” who tells amusing dad-jokes.

I found the story most gripping during the war years, as Rosie and the Huxleys wait on tenterhooks to hear news of the three sons. A couple of the plot twists (there are many) were too much for my taste, but I did enjoy this story and the interactions among its multicultural cast.

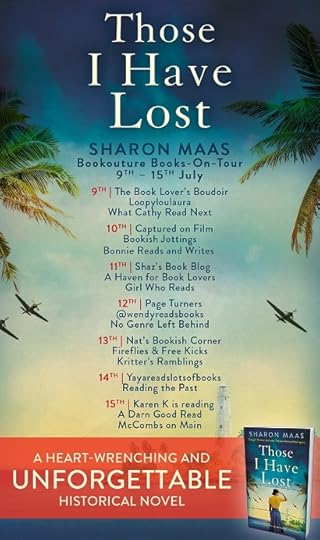

Those I Have Lost was published by Bookouture this month; I read it from a NetGalley copy, and this review forms part of the publisher's blog tour.

Author Bio:

Sharon Maas was born into a prominent political family in Georgetown, Guyana, in 1951. She was educated in England, Guyana, and, later, Germany. After leaving school, she worked as a trainee reporter with the Guyana Graphic in Georgetown and later wrote feature articles for the Sunday Chronicle as a staff journalist.

Her first novel, Of Marriageable Age, is set in Guyana and India and was published by HarperCollins in 1999. In 2014 she moved to Bookouture, and now has ten novels under her belt. Her books span continents, cultures, and eras. From the sugar plantations of colonial British Guiana in South America, to the French battlefields of World War Two, to the present-day brothels of Mumbai and the rice-fields and villages of South India, Sharon never runs out of stories for the armchair traveller.

Please visit the author at: https://www.sharonmaas.com/ and at https://twitter.com/sharon_maas.

Published on July 14, 2021 06:00