Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 38

December 15, 2020

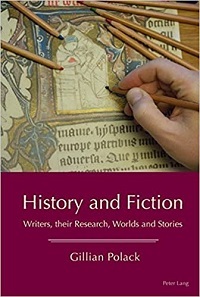

Interview with Gillian Polack, author of History and Fiction: Writers, their Research, Worlds, and Stories

I'm pleased to have Dr. Gillian Polack here today for a Q&A about her book History and Fiction: Writers, their Research, Worlds, and Stories, which is newly out in paperback from Peter Lang ($22.95/£15.00). I'm glad to see it finally available in this format, since this will encourage more individual readers and writers to check it out and pick up their own copies.

I'm pleased to have Dr. Gillian Polack here today for a Q&A about her book History and Fiction: Writers, their Research, Worlds, and Stories, which is newly out in paperback from Peter Lang ($22.95/£15.00). I'm glad to see it finally available in this format, since this will encourage more individual readers and writers to check it out and pick up their own copies.

History and Fiction takes an in-depth look at the varied approaches that fiction writers take in incorporating history into their stories. This can depend on many factors, including the genre they're writing, the demands of the marketplace, their emotional involvement with their chosen subject or period, and more.

Gillian's background and expertise give her a unique perspective on the complex history-fiction relationship. A scholar based in Canberra, Australia, she writes historical and speculative fiction and has doctorates in both Medieval History and Creative Writing. Her research for the book was based on interviews she conducted with a wide spectrum of authors. I first reviewed History and Fiction for the Historical Novels Review in 2016 and was impressed by its insights. As I wrote in the original review, "This study will be an essential read for genre scholars, but the accessible writing style extends its appeal beyond academic circles. Historical novelists can consult it for deeper insight into their own writing and research choices, while anyone curious about how authors bring the past to life through fiction will come away with considerable knowledge of what goes into the crafting of the novels they enjoy."

I hope you'll enjoy this Q&A. Please visit Gillian's website at https://gillianpolack.com for more background on her research and writings.

How did you first get the idea to write this book?

The relationships between history and different types of story are one of my lifelong interests. When I became a fiction writer, I read the scholarship on how history relates to novels and found a hole. I researched to fill the hole (mainly for my own benefit) and writers asked if I could explain my research to them, and History and Fiction was the result.

One of the book’s highlights, for me, was the honest commentary provided by the many authors you interviewed, and your analysis of their thoughts. How did you decide which authors to talk to?

I sent out a request through my networks for authors who had an interest in the Middle Ages to answer questions for my research. From those who expressed willingness, I chose those who represented the biggest possible range of author experience. I didn't want to focus on only famous authors or on a group of writers who were all as yet unpublished. I wanted a clear cross-section of experience and interest.

Why the Middle Ages? My first doctorate was in Medieval History, so I had the best skills for evaluating answers relating to knowledge and sources used by focusing on that period. I admit, having the Middle Ages as a focal point also gained me responses from a wider range of writers, for some writers back then knew me as a Medievalist and others as a writer of science fiction and fantasy.

I appreciated the broad focus on the types of authors who incorporate history in their fiction. This may be an American thing, but there doesn’t seem to be significant overlap between writers of historical fiction and speculative fiction, or their readerships – even though storytelling and detailed world-building are important to both genres, and authors of both are frequently inspired by real-world history. I was a fantasy reader long before I was a historical fiction reader – one genre led me to another – though that doesn’t seem typical. The genres diverge, of course, on the type of research involved, the purposes of the research, the level of historical accuracy, and other factors, as you’ve explained in the book. Do you feel that these two groups of writers (and/or communities of readers) could benefit from a greater acquaintance with one another, and if so, how?

I suspect the overlap between the two groups of writers is greater than it used to be. I am active in both, and I often find friends/fellow writers who are also. I will catch up with a couple of friends at a science fiction convention and a couple more at the Historical Novel Society Australasia conference. Our overlap group is not large in number, but it’s definitely growing.

I suspect the overlap between the two groups of writers is greater than it used to be. I am active in both, and I often find friends/fellow writers who are also. I will catch up with a couple of friends at a science fiction convention and a couple more at the Historical Novel Society Australasia conference. Our overlap group is not large in number, but it’s definitely growing. The genres diverge and we talk about that a lot when we meet up. Who writes what kind of story for what kind of audience, is what it boils down to. One thing that’s really clear about writers who work in both genres is that we’re all very aware of genre and how the history we need is different in each. Good editors are aware of this. I discovered this personally when I wrote a story for a mixed-genre anthology. I know the editor (Sherwood Smith) through speculative fiction but wrote historical fiction for It Happened at the Ball, because I wanted to explore what might happen after a couple of waves of plague (ironically, given this year). Sherwood edited it very much as historical fiction.

I probably should explore this area more one day. Where research meets and produces different types of fiction, and how editors handle the genre differences are fascinating questions.

The area with much less overlap is historians and historical fiction. More historians who are also fiction writers write historical fantasy, romance or literary fiction than historical fiction. I used to worry about how historians would deal with my Medieval time travel novel ( Langue[dot]doc 1305 ) because of this, but other historians have enjoyed it. Such a relief!

As you read over the responses from the authors, did they take you in any unexpected directions with your research?

I love research because there are always unexpected directions!

It still strikes me that I went in thinking about historical fiction and historical fantasy, and that now I feel very strongly that we should not be neglecting other genres. Historical romance is critical for the way many people interpret history and why someone falls in love with one period or another, for example. It’s understudied. Too many people say, “Oh, romance,” and miss its importance.

The responses also reminded me, over and over again, that writers are each and every one of them individuals with personal responses to history and with different publishing experience. I'm very good at interpreting the wider cultural patterns in narrative: those responses taught me that wider cultural patterns should never be divorced from real people.

Why a writer chooses a time and place and genre is critical. Who they are and what they experience plays a part in those choices. Elizabeth Chadwick's memory of her childhood has become my personal trigger for remembering that writers matter and that who they are affects what stories they tell.

Many historical fiction fans enjoy reading authors’ notes and learning more about the research and writing choices undertaken. You wisely point out, though, that the presence of bibliographies or notes doesn’t always indicate that the author has interpreted history correctly. What in your view makes for a good (or helpful, trustworthy, etc.) author’s note in a historical novel? (Feel free to provide specific examples if you’d like.)

I love this question. I don’t have a lot of opinions about the good, the helpful, the accurate, or even the trustworthy in author’s notes. I do, however, have opinions. Some writers want me to evaluate their notes. I have annoyed several of my friends because of this.

I love this question. I don’t have a lot of opinions about the good, the helpful, the accurate, or even the trustworthy in author’s notes. I do, however, have opinions. Some writers want me to evaluate their notes. I have annoyed several of my friends because of this.I was an historiographer before I became a Medievalist. The way historiographers interpret history is one of my favourite things, and so I don't judge bibliographies and notes on how they compare to the equivalent given by a specialist historian. This is why good and bad, helpful and unhelpful aren’t the categories that inform my judgement.

For me, author's prologues and epilogues and notes are tools to find out how the writer thinks about the history they've used in a given novel. I want to know where their insights come from and what writers want readers to think about in relation to their stories.

It's not about how accurate the history is, it's about how credible it is. How much do we want to believe it when we read the novel? A list of books, or an explanation of research, or a description of how an event is seen by an historian - all these things help me see a writer's relationship to history.

Some of the authors you interviewed described their strong emotional links to the periods and/or characters they wrote about, and you spoke about how this can color their research choices and their writing. Even more, they may not be aware this is happening. How can the average reader gain awareness of these potential biases?

Reading those author’s notes is an excellent start. I also read interviews (like this one!) and blog posts by writers. I look to see where they come from and how they define that magic word ‘research’. I always, always check for their emotional response. In History and Fiction Wendy Dunn’s answers to my questions are a perfect litmus test for emotional responses.

Emotional responses to the past are not bad things at all. What they do is help us follow a line of decisions a writer makes. If Writer A loves George IV passionately and will never hear a bad thing said about him, then they will write a very different story to Writer B who wants to express all their anger about how he treated his father or Writer C who refuses to write anything set after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Each of these writers may have identical characters, but the books will be vastly different. That’s where we see these responses at work in fiction.

The easiest way to find potential biases is to look for the trails they leave, in other words. Not all biases are bad, but we can make our own decisions about them if we understand them.

One of the statements you made in the first chapter, “The role of the fiction writer in exploring history, in creating new interpretations and in exploring old ones, cannot be underestimated,” struck me as being particularly true and relevant. What are some works of fiction you feel have been particularly influential in this respect, either for you personally or on a larger cultural level?

I have so many answers to this question.

I generally start with Lord Dunsany, William Morris, JRR Tolkien and the fantasy Middle Ages or Sir Walter Scott and the historical Middle Ages. Recently I added Maurice Druon and an entirely different historical Middle Ages to my answer, because what happens in French language historical fiction is quite different to what happens in English. I cannot count how many conversations I’ve had about the effect of Georgette Heyer and the entire rewriting of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century in the minds of many.

This is something I teach. I ask students to imagine a Richard III without Thomas More’s “History of King Richard III.” Even people who hate it and who despise Shakespeare's play and every other offshoot from More’s satire are affected by it. We can write stories that love Richard and stories that hate Richard and alternate histories that cut him out of history, but all of them are influenced by More and his followers.

I also love talking about it, because every culture uses story based on history to help shape what it is. Sometimes we take from the influential work and we add to it, but treasure its form and cultural function. Sometimes we do the opposite. This question is a well that never runs dry.

December 11, 2020

Looking at the "best of" historical fiction lists for 2020

As the year winds down, media outlets, bloggers, and other review venues are compiling lists of their favorite novels of 2020. Not all include historical fiction as its own category, but here are some sites that do. I enjoy looking over these lists to see which books I've read already (usually not many, since my tastes are eclectic and my reading is partly based on what I'm assigned), to get introduced to new titles, and to see whether I agree with the choices made.

In the Goodreads Choice Awards, Brit Bennett's The Vanishing Half won the historical fiction category handily with over 100K votes. The Jane Austen Society by Natalie Jenner took second place. I loved both books. And I've actually read 7 out of the 16 that were finalists, which isn't typical. My favorites among the finalists are The Vanishing Half, The Jane Austen Society, and .

The New York Times lists 10 standout novels of historical fiction. My favorite among them is Daniel Kehlmann's Tyll. There are a couple novels on this list I was lukewarm about. Only two titles overlap between the NYT list and the Goodreads list (Maggie O'Farrell's Hamnet and Hilary Mantel's The Mirror and the Light).

Kirkus Reviews also posted their Best Historical Fiction of 2020, with a dozen selections (Hamnet is the only one I've read).

NPR's Book Concierge is always fun to explore. I like how they intermix adult and children's titles in their historical fiction collage, along with historical romance. This site uses the broadest umbrella for the genre, which appeals to me.

Glancing at these lists so far, Alice Randall's Black Bottom Saints (Black Detroit from the early 20th century), Emma Donoghue's The Pull of the Stars (the 1918 flu epidemic), Jess Walter's The Cold Millions (early 20th-c Spokane), and Maggie O'Farrell's Hamnet (Shakespeare's England) make multiple appearances.

She Reads has two lists of best historicals for 2020, ones chosen by their historical fiction reviewer, Cindy Burnett, and another of their winners in the official She Reads awards.

The Times (London) lists their favorite novels set in the past. You'll need a login (which gives access to some free articles) to read it. This list includes one title I hadn't come across before, All Our Broken Idols by Paul M.M. Cooper, set in ancient Assyria and the present day. Mantel and O'Farrell are here too.

If I missed any lists, please let me know in the comments. I'm still debating about whether to post my own list, plus my year of reading isn't over yet.

December 7, 2020

A secret WWII history comes to light in Aimie K. Runyan's Across the Winding River

I’ve revisited this novel so many times in the past few months that the characters feel like old friends. First I read it back in June, but before I could gather my thoughts together and write a review, I was assigned a different book with a very short deadline – then the same thing happened in September. After finding some time over the Thanksgiving weekend, I got my writeup done at last.

I’ve revisited this novel so many times in the past few months that the characters feel like old friends. First I read it back in June, but before I could gather my thoughts together and write a review, I was assigned a different book with a very short deadline – then the same thing happened in September. After finding some time over the Thanksgiving weekend, I got my writeup done at last. Aimie K. Runyan’s fifth novel is anchored in two historical periods – California in 2007, and Germany during WWII – and told from three perspectives. The story combines a classic plot pattern of a young woman discovering her father’s secret wartime history with his first-person account of that history, along with a third strand from the viewpoint of a German woman, a female pilot and aircraft designer who’s an aristocrat by marriage, and who has secret Jewish heritage. The stories interlock, but not the way you’d assume.

In the modern era, Beth Cohen is startled to discover a decades-old snapshot of her father, Max, gazing into the eyes of a pregnant young blonde. At the end of his life, at age 90, Max Blumenthal is finally ready to reveal his involvement with the woman he loved and lost before he met Beth’s mother, hoping to solve a mystery that’s lingered for decades. In 1944, as a newly minted dentist, Max decides to enlist rather than wait to be drafted, feeling an obligation to do his part for the war because of his lost relatives from Latvia. Part of a medical detachment during the Battle of Hürtgen Forest near the German border, he gets pulled into the resistance movement after one night when he intercepts a young woman stealing medical supplies for a friend she claims is working against Hitler. He chooses to let her go.

Of the three protagonists, Johanna Schiller is the most intriguing. As a skilled test pilot, she doesn’t fall into the Nazis’ preferred role for women, and she grows uneasy about her brother’s quick absorption into the Hitler Youth and fellow Germans’ reporting on each other’s “unpatriotic” activities. Johanna also has a younger sister, Metta, who seems resigned to the life planned out for her as a loyal wife to the Reich. The story moves from the sexism German women faced under Nazi rule to the heroism of the resistance, and the courageous paths traveled by those who actively yet covertly rebelled. The plot has a couple of incredible coincidences but wraps up in a way that enables the characters to heal from the wounds of the past.

Across the Winding River was published by Lake Union/Amazon in August (reviewed from a NetGalley copy).

December 1, 2020

The WWII home front from the Cherokee viewpoint: Even As We Breathe by Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle

Clapsaddle’s debut, the first novel by an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, is an impressive work of literary historical fiction. Her protagonist’s journey of first love and coming-of-age is embedded in an Appalachian setting that feels both mysterious and tangibly real. She also pens a moving ode to the many conduits of human history – people’s memories, writings, bones, the very ground under our feet – and how we learn what they teach us.

Clapsaddle’s debut, the first novel by an enrolled member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, is an impressive work of literary historical fiction. Her protagonist’s journey of first love and coming-of-age is embedded in an Appalachian setting that feels both mysterious and tangibly real. She also pens a moving ode to the many conduits of human history – people’s memories, writings, bones, the very ground under our feet – and how we learn what they teach us. In 1942, nineteen-year-old Cowney Sequoyah, eager to escape his overbearing uncle and his home on the Cherokee reservation in the Smoky Mountains, takes a job with the grounds crew at the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, two hours away. Accompanying him on the drive is Essie Stamper, a young woman whose beauty, sophistication, and self-confidence unsettle him.

Born with a twisted foot, Cowney is ineligible for military service, but he gets entangled in wartime intrigue, nonetheless. The inn is being used by the U.S. Army to house high-ranking POWs, including foreign envoys and their families. While Cowney’s immediate supervisor treats him well, others on site exhibit racist attitudes towards Indians. He and Essie become good friends and frequently meet in an unoccupied hotel room to talk and play dominos, but Essie is keeping a secret from him, and the disappearance of a Japanese diplomat’s daughter threatens to destroy his freedom. As Cowney struggles to prove his good name, he gradually learns the truth about his late father’s death in WWI.

Through Cowney, Clapsaddle presents warm, lyrical observations of Cherokee family life and traditions, such as the comfort of his grandmother Lishie’s quilts and the holiness of “ladies in boldly colored headscarves [who] sang ‘Amazing Grace’ in our language.” The concluding message about the characters’ ties to their homeland is also beautifully affecting.

Even As We Breathe was published by Fireside Industries, an imprint of the University Press of Kentucky that publishes on Appalachian themes, in July. I reviewed it from Edelweiss for the Historical Novels Review.

November 28, 2020

The Four Winds by Kristin Hannah, her forthcoming epic about women's strength during the Dust Bowl

With this emotionally charged epic of Dust Bowl-era Texas and its dramatic aftermath, the prolific Hannah has added another outstanding novel to her popular repertoire.

With this emotionally charged epic of Dust Bowl-era Texas and its dramatic aftermath, the prolific Hannah has added another outstanding novel to her popular repertoire. In 1921, Elsa Wolcott is a tall, bookish woman of 25 whose soul is stifled by her superficial parents. By 1934, after marrying Rafe Martinelli, a young Italian Catholic who was the first man to show her affection, Elsa is a mother of two who has found a home on her beloved in-laws’ farm. Severe drought and terrible dust storms affect everyone in this proud family, and they are all forced to make tough choices.

This wide-ranging saga ticks all the boxes for deeply satisfying historical fiction. Elsa is an achingly real character whose sense of self-worth slowly emerges through trying circumstances, and her shifting relationship with her rebellious daughter, Loreda, is particularly moving. Hannah brings the impact of the environmental devastation on the Great Plains down to a personal level with ample period-appropriate details and reactions, showing how people’s love for their land made them reluctant to leave.

The storytelling is propulsive, and the contemporary relevance of the novel’s themes—for example, how outsiders are unfairly blamed for economic inequities—provides additional depth in this rich, rewarding read about family ties, perseverance, and women’s friendships and fortitude.

The Four Winds will be published by St. Martin's Press in February 2021. I'd reviewed it from an Edelweiss e-copy for Booklist's 10/15/20 issue. Hannah's earlier historical novel, The Nightingale, was the historical fiction category winner in the Goodreads Choice awards for 2015 (I haven't read it yet, so no spoilers, please!). Will you be reading this one, and which among her works is your favorite so far? Happy to hear your recommendations.

November 24, 2020

Twelve upcoming historical novels for 2021 that aren't set during WWII

Here's the first in a series of previews of upcoming 2021 releases. As you've no doubt noticed, publishers' interest in World War II as a historical fiction setting continues unabated. I've been keeping an eye on current publishing deals, and the trend looks to last through 2022 at least. For readers who prefer earlier settings, or who enjoy focusing on a wide variety of eras, this post is for you. These dozen titles will be appearing from US publishers in the first half of next year. Links go to the books' Goodreads pages.

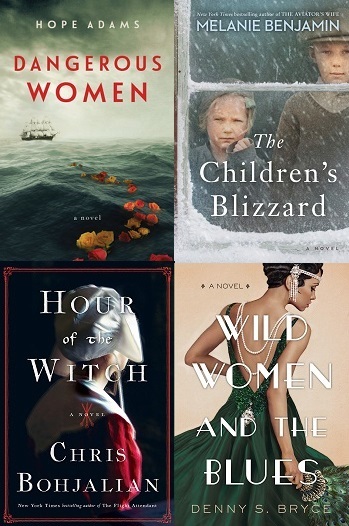

Hope Adams' first novel Dangerous Women (Berkley, Feb.) follows 180 Englishwomen on a convict ship to Van Diemen's Land (modern Tasmania) in 1841. Along the way, they assemble a giant quilt, an artifact that can be viewed today, and evade a potential murderer on board. The setting for Melanie Benjamin's The Children's Blizzard (Delacorte, Feb.) is the Dakota Territory in January 1888. Young people and their teachers were in school as a sudden blizzard hit, leaving them with tough decisions to make. Moving to an earlier period than his usual, Chris Bohjalian's Hour of the Witch (Doubleday, Apr.) delves into the life of a young Puritan woman in 1660s Boston who's desperate to end her violent marriage. And for her debut, Wild Women and the Blues (Kensington, Mar.), Denny S. Bryce intertwines the stories of a chorus girl in Jazz Age-Chicago and a modern film student who interviews her decades later, when she's 110 years old.

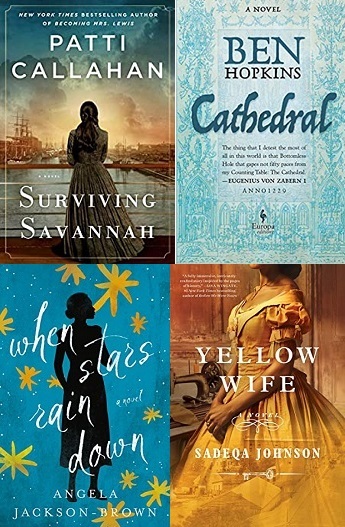

Incorporating another pulled-from-history subject, Patti Callahan (Becoming Mrs. Lewis) focuses on the sinking of the steamship Pulaski in 1838, a family affected by the tragedy, and a contemporary professor researching the topic, in her Surviving Savannah (Berkley, Mar). Ben Hopkins' Cathedral (Europa, Jan.) looks tailor-made for Ken Follett fans, with its subject the bustling community surrounding the construction of a Gothic cathedral in 13th-century Germany. When Stars Rain Down by Angela Jackson-Brown (Thomas Nelson, Apr.) takes us to small-town, Depression-era Georgia with the story of a young Black woman coming of age during a time when the KKK is wreaking havoc in her community. Sadeqa Johnson's Yellow Wife (Simon & Schuster, Jan.), set in the mid-19th century, recounts the tale of a young woman hoping to be granted her freedom but who finds herself returned to slavery and working in a notorious Virginia jail (based on a true story).

Mitchell James Kaplan's third novel, Rhapsody (Gallery, Mar.) centers on the decade-long affair between composers George Gershwin and Kay Swift in the 1920s-30s. In the Palace of Flowers by Victoria Princewill (Cassava Republic, Feb.) takes place in the royal court of Iran in the 1890s, with two enslaved people as its protagonists. (The UK release date was this August.) Mary Sharratt's historical novels are always excellent, and I'm looking forward to Revelations (HMH, Apr.), her take on English mystics Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe in the 15th century. Lastly, Leaving Coy's Hill by Katherine A. Sherbrooke (Pegasus, May) is another work of biographical fiction, illuminating the life of Lucy Stone, a 19th-century American orator and abolitionist.

November 22, 2020

Millicent Glenn's Last Wish by Tori Whitaker, a multi-period novel about family secrets and family ties

Tori Whitaker is an avid reader of novels that juggle past and present-day timelines, highlighting worthy examples on social media and penning a feature article on multi-period fiction (Historical Novels Review, Issue 83). In her debut, she demonstrates mastery of this popular historical fiction format herself.

Tori Whitaker is an avid reader of novels that juggle past and present-day timelines, highlighting worthy examples on social media and penning a feature article on multi-period fiction (Historical Novels Review, Issue 83). In her debut, she demonstrates mastery of this popular historical fiction format herself. Her heroine is Millicent Glenn, a spry widow of 90 who readers will come to care for right away. Family means everything to Millie, so when her daughter Jane moves back home to Cincinnati in 2015, and granddaughter Kelsey announces her pregnancy, she couldn’t be happier. Millie’s relationship with Jane is strained, and she knows that to repair it, she must find the courage to reveal a traumatic time from the Glenns’ past and hope for Jane’s forgiveness.

Back in mid-century Ohio, Millie is a former tenement girl of German heritage newly married to her sweetheart, Dennis Glenn. Remembering her mother’s admonishment to earn her own income, she’s excited to help Dennis spread the word about his prefab home dealership. When she becomes pregnant after years of trying, they feel their prayers are answered. Millie’s dreams of a large family never materialize, though, for a terrible reason that becomes a secret too painful to reveal.

Both timelines are equally gripping, and the shifts between them keep the suspense level high. Whitaker notices the small details that make the 1950s Midwest feel tangible, such as metal milk-delivery boxes, radio soap operas, and two-tone Chevrolets. In addition to nostalgic elements of vintage décor and pastimes, though, the story illustrates the weight of expectations women faced, pressured to be perfect wives and mothers while seeing their career hopes stifled. Millie can’t even open a savings account without Dennis’s permission (sadly, historically accurate). This tenderly written, fast-moving tale of marriage, women’s friendships, and family reconciliation is satisfying and extremely moving.

Millicent Glenn's Last Wish was published by Lake Union in October 2020. There are over 8000 ratings on Amazon, which is pretty amazing; the novel was chosen for their First Reads program over the summer, which got it into many readers' hands early. I reviewed it from a PDF for November's Historical Novels Review.

If you're interested in dual-timeline novels, Tori Whitaker's article "Multi-Period Novels: The Keys to Weaving Together Two Stories from Different Time Periods" will be worth reading. She describes several plot patterns used in these stories and interviews authors Chanel Cleeton, Jane Johnson, James Carroll, and Ariel Lawhon about their writing. The other day, the author announced a deal for her upcoming book, another multi-generational novel set in Prohibition-era Detroit and modern Kentucky. I await it eagerly.

November 19, 2020

The Tainted by Cauvery Madhavan, a novel of Ireland, India, and their intersecting histories

Madhavan describes an era long gone which continues to make an impact. An Indian-born writer who has lived in Ireland for over thirty years, she conveys her extensive familiarity with both countries’ histories and how they intersected. The first half of this thought-provoking novel opens in 1920, as Private Michael Flaherty settles into life in the Indian hill town of Nandagiri along with his regiment, the Royal Irish Kildare Rangers.

Madhavan describes an era long gone which continues to make an impact. An Indian-born writer who has lived in Ireland for over thirty years, she conveys her extensive familiarity with both countries’ histories and how they intersected. The first half of this thought-provoking novel opens in 1920, as Private Michael Flaherty settles into life in the Indian hill town of Nandagiri along with his regiment, the Royal Irish Kildare Rangers. While assisting the local priest with Sunday Mass preparations, Michael meets Rose Twomey, a pretty Anglo-Indian who serves as the lady’s maid to the wife of his commanding officer, Colonel Aylmer. In her diary, Rose shares her feelings about Michael, her role in the Aylmer family, and her longing for Ireland, which she considers her true homeland. Her naivete is heartbreaking, for readers know that even with her elegant handwriting, fair skin, and her utter rejection of her Indian heritage, she’ll never be accepted into Irish society. When Michael and his fellow soldiers get word about the atrocities committed by the Black and Tans during the Irish war for independence, they take drastic action that affects his relationship with Rose.

The novel’s second half is even better. In 1982, Richard Aylmer, the colonel’s grandson, travels to Nandagiri for a photography project, and the friendships he establishes allow for open cross-cultural dialogue about the region’s complicated history. A key contributor to the discourse, May Twomey, Rose’s granddaughter, wryly observes Anglo-Indians’ misplaced sense of nostalgia for the days of the Raj: “We’re tainted – we were never white enough then and will never be brown enough now.” She’s a terrific character, a woman with a clear-eyed view of the past and present. The story offers a lot to unpack about colonialism and social belonging and is recommended for its insights and thoughtful writing.

The Tainted was published by Hope Road in 2020, and I reviewed it from a purchased copy for November's Historical Novels Review.

The Royal Irish Kildare Rangers are based on the historical Connaught Rangers. As I learned on Twitter afterward, on November 3rd, 2020, the Embassy of Ireland in New Delhi hosted a virtual conference with Jawaharlal Nehru University entitled India, Ireland, and World War I: The Connaught Rangers 1920 Mutiny and its Socio-Political Dimensions. Author Cauvery Madhavan was a featured speaker, discussing the historical background to The Tainted and how she wove it into her story. The archived presentation is available on Facebook. Her session begins around the three-hour, 29-minute mark (3:29:00). Having just finished the novel, I found it absolutely fascinating.

November 15, 2020

The Flame Within by Liz Harris, an English family saga set between the wars

The pages turn swiftly in The Flame Within, second in Liz Harris’s Linford Saga. Rather than a sequel to The Dark Horizon, it works as a companion volume, revealing the full story of a secondary character: Alice Foster Linford, aunt-by-marriage of the first book’s protagonists.

The pages turn swiftly in The Flame Within, second in Liz Harris’s Linford Saga. Rather than a sequel to The Dark Horizon, it works as a companion volume, revealing the full story of a secondary character: Alice Foster Linford, aunt-by-marriage of the first book’s protagonists. In the prologue, set in Belsize Park, London, in 1923, Alice takes a new position as companion to an elderly woman while debating how to win back her estranged husband, Thomas Linford, whom she had somehow wronged. The scene then reverts to 1904, with young Alice growing up in the small Lancashire town of Waterfoot.

Wanting a future beyond mill or factory work, Alice aims to lose her local accent and improve her education. Life interferes with her plans, though, until her training with the British Red Cross, and the outbreak of war, introduce her to Thomas, youngest son of a prominent family of suburban London builders. After suffering injuries in France, Thomas, who uses a wheelchair and prosthetic leg, has difficulty adjusting to life at home. A patient, caring woman, Alice becomes worn down by her formerly cheerful husband’s moodiness and jealousy and the restrictions he imposes on her.

For readers of The Dark Horizon, some of the plot in the middle will be familiar, but the new angle enhances the earlier picture. (The book will also read well on its own.) Joseph Linford, head of the family firm, remains a daunting figure, but because he likes and approves of Alice, his nefarious side doesn’t emerge here. Harris deftly interweaves many social issues of the day, including how wartime trauma can affect a marriage, legal issues affecting women, and the difficulties of crossing class lines. Alice is a sympathetic heroine who makes realistic choices for a woman in her position. Without giving spoilers, the conclusion is very satisfying.

The Flame Within was published by Heywood Press in October, and I first reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review. If you missed reading The Dark Horizon , I posted a review last month. I'm curious to see who Liz Harris's next protagonist will be as the series continues.

November 11, 2020

Dark Tides continues Philippa Gregory's Fairmile saga in 17th-century England and America

Gregory continues her Fairmile saga, following the atmospheric Tidelands (2019), by casting a broad arc spanning the Old and New Worlds and adding a mysterious, disruptive new character.

Gregory continues her Fairmile saga, following the atmospheric Tidelands (2019), by casting a broad arc spanning the Old and New Worlds and adding a mysterious, disruptive new character. In 1670, Alinor Reekie and her daughter, Alys, reside in London, where Alinor practices herbalism and Alys runs a small wharf. Then Sir James Avery, Alinor’s faithless former lover, returns hoping to marry her, and Livia, her son Rob’s Italian wife, shows up with her baby, claiming that Rob drowned in Venice. Expressing disappointment in her in-laws’ low social status, Livia settles into their home and insinuates herself into the family business, and Alinor doesn’t trust her.

In distant New England, Alinor’s brother, Ned, seeks peace as tension stirs between colonists and the Indians. His tale, while evocatively illustrating English-Native relations and the English Civil War’s far-reaching aftereffects, feels disconnected from the juicier story of uncovering exactly what Livia’s endgame is.

Resolute and proud of her working-class heritage, Alinor remains enigmatically compelling. Answers arrive via an unexpected avenue as the plot heats up, with dramatic twists aplenty.

Dark Tides is published this month by Atria/Simon & Schuster; I reviewed it initially for the 10/15/20 issue of Booklist (reprinted with permission).

I'd previously reviewed Tidelands last September. Comparing the two, I prefer Tidelands. Livia is a character I found extremely irritating, although to be fair, Alinor feels the same (in other words, she's written that way). And I expected the stories set in New England and London to connect more than they did, but apart from letters and occasionally goods moving across the Atlantic, they're essentially separate. I did appreciate the New World storyline, though, as it delves into an aspect of history rarely covered in historical fiction.