Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 13

March 29, 2021

THE PAST AND THE FUTURE

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich, c. 1818

I was listening to a podcast of “The Remnant” the other day, on which Jonah Goldberg made the observation that while political conservatives have usually gotten their ideals from the past, progressives have looked to the future. It struck me how much this applied to the history of architecture. Architecture has traditionally been conservative, not only because buildings were expensive and had to last a long time, but also because clients—the monarchy, the Church, and the merchant class—were conservative. For centuries, architectural ideals were rooted in ancient Greece, Rome, and the Middle Ages. This began to change at the end of the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the Art Nouveau movement, and was later fully realized by the utopian ideals of Russian constructivism and German modernism. Goldberg noted that while the danger for the conservative position is the attraction of nostalgia, it is precisley the draw of utopianism that is the danger for the progressive left. This is particularly dangerous for architecture because while past experience can provide a solid foundation for the art of building, the idealized future is unknown—and unknowable.

The post THE PAST AND THE FUTURE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

March 27, 2021

URBAN DISCONTINUITIES

Transect Urbanism is a collection of essays that describe a seminal idea of the New Urbanism movement. The concept is roughly based on observations made by Alexander von Humboldt, a nineteenth-century Prussian naturalist and Patrick Geddes, a twentieth-century Scottish biologist. Geddes was a pioneering urban planner and his Valley Section drawing of 1909 was the basis for a theory postulated by Andrés Duany a century later. Duany’s Rural-to-Urban Transect describes a smooth continuum of six zones—Natural, Rural, Sub-Urban, General Urban, Urban Center, Urban Core—from less to more dense, and from less to more urbanized. Perhaps it is the exception that proves the rule, but what strikes me is that many of my most memorable urban experiences have been the result of roughness rather than smoothness, of odd juxtapositions: the escarpment and ocean beach next to downtown Santa Monica, and Copacabana Beach in Rio; Mount Royal in the middle of downtown Montreal, and the Acropolis in Athens; the quais along the Seine in Paris, and the view of sculls and sailboats on the Charles River in Cambridge. Walking along Fifth Avenue beside Central Park and looking over a low stone wall at a large chunk of the bucolic Adirondacks you experience the Transect’s Zone T1 (Natural) and T6 (Urban Core) simultaneously. Unforgettable.

Transect Urbanism is a collection of essays that describe a seminal idea of the New Urbanism movement. The concept is roughly based on observations made by Alexander von Humboldt, a nineteenth-century Prussian naturalist and Patrick Geddes, a twentieth-century Scottish biologist. Geddes was a pioneering urban planner and his Valley Section drawing of 1909 was the basis for a theory postulated by Andrés Duany a century later. Duany’s Rural-to-Urban Transect describes a smooth continuum of six zones—Natural, Rural, Sub-Urban, General Urban, Urban Center, Urban Core—from less to more dense, and from less to more urbanized. Perhaps it is the exception that proves the rule, but what strikes me is that many of my most memorable urban experiences have been the result of roughness rather than smoothness, of odd juxtapositions: the escarpment and ocean beach next to downtown Santa Monica, and Copacabana Beach in Rio; Mount Royal in the middle of downtown Montreal, and the Acropolis in Athens; the quais along the Seine in Paris, and the view of sculls and sailboats on the Charles River in Cambridge. Walking along Fifth Avenue beside Central Park and looking over a low stone wall at a large chunk of the bucolic Adirondacks you experience the Transect’s Zone T1 (Natural) and T6 (Urban Core) simultaneously. Unforgettable.

March 23, 2021

POST-MODERNIST

Fletcher House, Nashville

The headline in Hugh Newell Jacobsen’s obituary in the New York Times describes him as a “famed modernist.” Famed he was, especially as the designer of exquisite high-end houses, but to call him a modernist is inaccurate. He was, rather, a post-modernist. That other post-modern master, James Stirling, was critical of mainstream modernism. “The language itself was so reductive that only exceptional people could design modern buildings in a way that was interesting,” he said.“It got stuck and it will have to unstick itself to move one.” Stirling’s unsticking involved broadening the language by introducing historicist motifs and color. Jacobsen (1929-2021) did it by combining minimalist modern interiors with traditional domestic forms (pitched roofs) and vernacular materials (clapboard). Unlike many modernists, he was not averse to symmetry and axes. The forms and materials depended on the location: coastal Maine, Nantucket, the Florida Panhandle. His houses always look at home in their sites. They also have another quality. A large house by a true modernist like Richard Meier can remind me of an upscale clinic; a Jacobsen house always looks—and feels—like a home.

March 20, 2021

NEW BLOOD

I recently came across an article in The Architect’s Newspaper titled “The future of our profession depends on diversity.” The author argues that the architectural profession needs to take specific steps to increase diversity. “The architecture profession runs the risk of becoming irrelevant if we do not adapt and create pathways for minorities to enter and lead the profession,” he writes. Received wisdom, but is it true? Or, rather, hasn’t it always been true? When I studied architecture in the 1960s, there were no women in my class, no blacks, and no aboriginal Canadians. But we were a mixed group: five immigrants (two from Hong Kong, two from Europe, one from Jamaica), four Jewish Montrealers, three Anglo Canadians, one French Canadian, one Italian Canadian, one Yugoslav Canadian. Our teachers were likewise international: two Brits, a Pole, a Hungarian, in addition to a scattering of Anglo Canadians. Architecture, at least in Montreal, had always benefitted from diversity. The school of architecture that I attended was founded by Scots, and their Arts and Crafts sensibility (as opposed to the Beaux-Arts background of many U.S. schools) was part of its tradition. I never saw architecture as a closed profession. In 1960s Montreal, the two leading architects were immigrants from Australia and Poland, and the partners of the top firm in the city consisted of three native-born Canadians (two English one French), and two immigrants, one born in Warsaw the other in Athens. My first job was with Moshe Safdie, an Israeli immigrant. Starting in the mid-twentieth century, the architectural profession in the U.S. likewise benefitted from the infusion of new blood, whether it came from immigrants or previously under-represented minorities such as Jews and Asians. And in many cases, these minorities did indeed “lead the profession” (think Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, I. M. Pei, and Frank Gehry). My point is that they did so not because of any set-asides or “pathways,” but rather because of their innate talents and abilities.

I recently came across an article in The Architect’s Newspaper titled “The future of our profession depends on diversity.” The author argues that the architectural profession needs to take specific steps to increase diversity. “The architecture profession runs the risk of becoming irrelevant if we do not adapt and create pathways for minorities to enter and lead the profession,” he writes. Received wisdom, but is it true? Or, rather, hasn’t it always been true? When I studied architecture in the 1960s, there were no women in my class, no blacks, and no aboriginal Canadians. But we were a mixed group: five immigrants (two from Hong Kong, two from Europe, one from Jamaica), four Jewish Montrealers, three Anglo Canadians, one French Canadian, one Italian Canadian, one Yugoslav Canadian. Our teachers were likewise international: two Brits, a Pole, a Hungarian, in addition to a scattering of Anglo Canadians. Architecture, at least in Montreal, had always benefitted from diversity. The school of architecture that I attended was founded by Scots, and their Arts and Crafts sensibility (as opposed to the Beaux-Arts background of many U.S. schools) was part of its tradition. I never saw architecture as a closed profession. In 1960s Montreal, the two leading architects were immigrants from Australia and Poland, and the partners of the top firm in the city consisted of three native-born Canadians (two English one French), and two immigrants, one born in Warsaw the other in Athens. My first job was with Moshe Safdie, an Israeli immigrant. Starting in the mid-twentieth century, the architectural profession in the U.S. likewise benefitted from the infusion of new blood, whether it came from immigrants or previously under-represented minorities such as Jews and Asians. And in many cases, these minorities did indeed “lead the profession” (think Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, I. M. Pei, and Frank Gehry). My point is that they did so not because of any set-asides or “pathways,” but rather because of their innate talents and abilities.

March 12, 2021

IN MEMORIAM

Ten years ago I joined the jury of the Driehaus Prize for Classical Architecture. I came to know Richard H. Driehaus (1942-2021) as padrone of the prize and as a munificent host on my periodic trips to Chicago. But his passing this week touched me in an unexpected way—I had lost a friend. Like anyone who met him, I was impressed by his curiosity and intelligence. And by his generosity. Over the years I occasionally sent him pieces of my writing that I thought would interest him—and everything interested him: people, buildings, art, cars. I once introduced him to a public gathering as a true son of the great Daniel Burnham. Like Burnham, Richard never made small plans, and like him he leaves a large legacy, not only in his native Chicago, but around the world.

Ten years ago I joined the jury of the Driehaus Prize for Classical Architecture. I came to know Richard H. Driehaus (1942-2021) as padrone of the prize and as a munificent host on my periodic trips to Chicago. But his passing this week touched me in an unexpected way—I had lost a friend. Like anyone who met him, I was impressed by his curiosity and intelligence. And by his generosity. Over the years I occasionally sent him pieces of my writing that I thought would interest him—and everything interested him: people, buildings, art, cars. I once introduced him to a public gathering as a true son of the great Daniel Burnham. Like Burnham, Richard never made small plans, and like him he leaves a large legacy, not only in his native Chicago, but around the world.

March 9, 2021

THE REAL THING

My wife and I live in a downtown Philadelphia loft in the Larkin Building, a 12-story industrial building built in 1912-13. The builder was the Larkin Company, which a decade earlier had hired Frank Lloyd Wright to build its headquarters building in Buffalo, N.Y. Our building was designed by a lesser light. C. J. Heckman was a Buffalo-based architect about whom the internet provides no information at all. Was he the Larkin house architect, or did he simply specialize in industrial buildings, the lowest rung on the practitioner’s ladder? Perhaps the latter, because our building is a very early example of reinforced concrete construction, a 20 by 20-foot grid of mushroom columns. The building originally contained showrooms on the first floor, offices on the second, and manufacturing and warehouse floors above. Mundane uses, but in small ways Heckman gave the building some real refinement. He designed the windows to emphasize the 20-foot structural grid. As architects had been doing since ancient Greek times, he beefed up the corners. He treated the lower two floors as a “base” and introduced an external molding that turned the upper two floors—ever so subtly—into an attic (the original building had a prominent cornice, long since gone). In these ways, although Heckman was working with a new material—reinforced concrete—and a new structural system, he established links to the architectural past. At the same time as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (not yet Le Corbusier) was doodling sketches of the Dom-ino House, Heckman was building the real thing, and doing it in a way that did not upset but rather re-affirmed the old architectural verities.

March 6, 2021

HATS

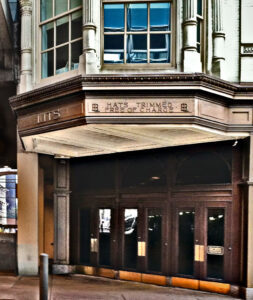

The old Lit Brothers department store (built and expanded between 1859 and 1918) on Philadelphia’s Market Street has a sign over one of its corner entrances, that has always puzzled me. HATS TRIMMED FREE OF CHARGE is embossed into the metal fascia of the canopy. It’s the only such sign. But whose hats, men or women? Did it refer to a hat bought in the store, or was it—as I suspected—an enticement to walk in and get your hat “trimmed,” whatever that meant? And why was this procedure so important—and so common—that it had to be emblazoned over the store entrance? The Internet has many references to the sign, but I couldn’t find an explanation. The closest I got was an article on how Stetson hats were made (John B. Stetson, a native of New Jersey, not Texas, established his factory in Philadelphia in 1865). The original Stetsons were made out of felt composed of beaver fur. The last step in the manufacturing process was to sand the blocked felt to remove excess hairs. Did such felt hats require periodic sanding and “trimming.” Perhaps.

The old Lit Brothers department store (built and expanded between 1859 and 1918) on Philadelphia’s Market Street has a sign over one of its corner entrances, that has always puzzled me. HATS TRIMMED FREE OF CHARGE is embossed into the metal fascia of the canopy. It’s the only such sign. But whose hats, men or women? Did it refer to a hat bought in the store, or was it—as I suspected—an enticement to walk in and get your hat “trimmed,” whatever that meant? And why was this procedure so important—and so common—that it had to be emblazoned over the store entrance? The Internet has many references to the sign, but I couldn’t find an explanation. The closest I got was an article on how Stetson hats were made (John B. Stetson, a native of New Jersey, not Texas, established his factory in Philadelphia in 1865). The original Stetsons were made out of felt composed of beaver fur. The last step in the manufacturing process was to sand the blocked felt to remove excess hairs. Did such felt hats require periodic sanding and “trimming.” Perhaps.

March 3, 2021

ROADBLOCKS

The pandemic lockdown has turned me into a podcast listener. One of my favorites is GLOP Culture, with Jonah Goldberg, Rob Long, and John Podhoretz. In a recent conversation about woke bullying at the New York Times and Slate, Long made an interesting observation. There are too many wannabe journalists chasing too few jobs. What if wokeness is simply an expression of careerism, the young finding a way to make room for themselves by pushing out the old? A recent wokey article in Architect magazine, the official journal of the AIA, approvingly describes the dean of the Princeton school of architecture characterizing professional licensure as “a gargantuan roadblock to a racially and otherwise diverse and equitable field.” Since architecture is a zero-sum game—if you get the job then I don’t—I’m not sure what “equitable” means. In any case, the architectural profession needs more roadblocks, not fewer. I once asked a colleague at the Wharton School why his MBA grads earned two or three times more than my architecture students who had actually spent a year longer in graduate school. “Your guys actually like what they do, so why should people pay them for it,” he said jokingly. More seriously, he pointed out that there were simply too many architects. When I graduated there were 6 Canadian schools of architecture; today there are 12. In the United States there are 121 accredited programs; more than 5,000 graduates every year. Too many architects; too little work.

The pandemic lockdown has turned me into a podcast listener. One of my favorites is GLOP Culture, with Jonah Goldberg, Rob Long, and John Podhoretz. In a recent conversation about woke bullying at the New York Times and Slate, Long made an interesting observation. There are too many wannabe journalists chasing too few jobs. What if wokeness is simply an expression of careerism, the young finding a way to make room for themselves by pushing out the old? A recent wokey article in Architect magazine, the official journal of the AIA, approvingly describes the dean of the Princeton school of architecture characterizing professional licensure as “a gargantuan roadblock to a racially and otherwise diverse and equitable field.” Since architecture is a zero-sum game—if you get the job then I don’t—I’m not sure what “equitable” means. In any case, the architectural profession needs more roadblocks, not fewer. I once asked a colleague at the Wharton School why his MBA grads earned two or three times more than my architecture students who had actually spent a year longer in graduate school. “Your guys actually like what they do, so why should people pay them for it,” he said jokingly. More seriously, he pointed out that there were simply too many architects. When I graduated there were 6 Canadian schools of architecture; today there are 12. In the United States there are 121 accredited programs; more than 5,000 graduates every year. Too many architects; too little work.

February 27, 2021

CONVICTION

I’ve come to the conclusion that what I value most in architectural work, apart from skill and competence, is conviction. That is why I appreciate the work of Louis Kahn and his teacher Paul Cret equally, because while their work is quite different, it’s executed with a strong sense of purpose. Absent that, architecture risks becoming merely a weak-kneed copy-book reproduction, whether it is modernist or classicist. There is nothing weak-kneed about one of my favorite Philadelphia buildings, the Main Branch of the U.S. Post Office on Market and Thirtieth Street. It was built in 1931-35 and designed by the leading local firm of Rankin & Kellogg. John Hall Rankin was a graduate of MIT and Thomas M. Kellogg had attended MIT and apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White. They formed a partnership in 1891 and acquired a national reputation after winning competitions for several prominent federal buildings. The Post Office, which covers a city block, is a five-story steel frame building clad in Indiana limestone. The flat roof was designed as a landing pad for autogyros that brought air mail from nearby airports in Camden and Philadelphia. The overall composition of the building is Beaux-Arts classicist but the style is Art Deco combined with pre-Columbian Inca motifs. An odd combination. I always glance at the granite entrance portal as I walk by. A stylized American eagle is perched above the entrance. The curved Art Deco forms are stylishly streamlined, but they also suggest—a mail box! The portal contrasts with the smooth limestone wall and the Pre-Columbian patterned panel above. It shouldn’t make sense but it does. That’s conviction.

I’ve come to the conclusion that what I value most in architectural work, apart from skill and competence, is conviction. That is why I appreciate the work of Louis Kahn and his teacher Paul Cret equally, because while their work is quite different, it’s executed with a strong sense of purpose. Absent that, architecture risks becoming merely a weak-kneed copy-book reproduction, whether it is modernist or classicist. There is nothing weak-kneed about one of my favorite Philadelphia buildings, the Main Branch of the U.S. Post Office on Market and Thirtieth Street. It was built in 1931-35 and designed by the leading local firm of Rankin & Kellogg. John Hall Rankin was a graduate of MIT and Thomas M. Kellogg had attended MIT and apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White. They formed a partnership in 1891 and acquired a national reputation after winning competitions for several prominent federal buildings. The Post Office, which covers a city block, is a five-story steel frame building clad in Indiana limestone. The flat roof was designed as a landing pad for autogyros that brought air mail from nearby airports in Camden and Philadelphia. The overall composition of the building is Beaux-Arts classicist but the style is Art Deco combined with pre-Columbian Inca motifs. An odd combination. I always glance at the granite entrance portal as I walk by. A stylized American eagle is perched above the entrance. The curved Art Deco forms are stylishly streamlined, but they also suggest—a mail box! The portal contrasts with the smooth limestone wall and the Pre-Columbian patterned panel above. It shouldn’t make sense but it does. That’s conviction.

February 26, 2021

THE AFTER TIME

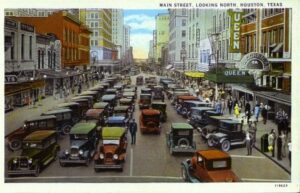

A lot has been written about the effect of Covid-19 and the associated year-long shutdown, on cities. The present situation is dispiriting: so many of the amenities that attracted people to cities in the first place—theaters, museums, ball parks, restaurants, bars—are either closed or half-closed. Too many businesses have gone out of business. Municipal tax revenue is down; municipal social costs are up. Commuting is down; crime is up. Tourism—a number one industry in many cities—is down; homelessness is up. Most urban commentators have reverted to their priors. Advocates of decentralization see a further shift to suburban living; digital seers see more work at home; downtown advocates say not to worry, it will all come back. Will it? Peggy Noonan’s contrarian column in the Wall Street Journal makes for sobering reading. “You can know something yet not fully absorb it. I think that’s happened with the pandemic. It is a year now since it settled into America and brought such damage—half a million dead, a nation in lockdown, a catastrophe for public schools. We keep saying ‘the pandemic changed everything,’ but I’m not sure we understand the words we’re saying.”

A lot has been written about the effect of Covid-19 and the associated year-long shutdown, on cities. The present situation is dispiriting: so many of the amenities that attracted people to cities in the first place—theaters, museums, ball parks, restaurants, bars—are either closed or half-closed. Too many businesses have gone out of business. Municipal tax revenue is down; municipal social costs are up. Commuting is down; crime is up. Tourism—a number one industry in many cities—is down; homelessness is up. Most urban commentators have reverted to their priors. Advocates of decentralization see a further shift to suburban living; digital seers see more work at home; downtown advocates say not to worry, it will all come back. Will it? Peggy Noonan’s contrarian column in the Wall Street Journal makes for sobering reading. “You can know something yet not fully absorb it. I think that’s happened with the pandemic. It is a year now since it settled into America and brought such damage—half a million dead, a nation in lockdown, a catastrophe for public schools. We keep saying ‘the pandemic changed everything,’ but I’m not sure we understand the words we’re saying.”

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers