Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 12

May 30, 2021

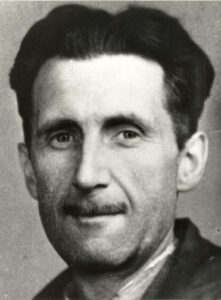

ORWELLIAN

In a 1946 essay on politics and the English language, George Orwell criticized pretentious diction and meaningless words. “Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic color, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance.” What would he have made of today’s slew of popular adjectives: social (distancing), societal (change), equitable (outcomes), or systemic (racism)? “A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks,” observed Orwell. “It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier to have foolish thoughts.”

In a 1946 essay on politics and the English language, George Orwell criticized pretentious diction and meaningless words. “Adjectives like epoch-making, epic, historic, unforgettable, triumphant, age-old, inevitable, inexorable, veritable, are used to dignify the sordid process of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic color, its characteristic words being: realm, throne, chariot, mailed fist, trident, sword, shield, buckler, banner, jackboot, clarion. Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac, ancien regime, deus ex machina, mutatis mutandis, status quo, gleichschaltung, weltanschauung, are used to give an air of culture and elegance.” What would he have made of today’s slew of popular adjectives: social (distancing), societal (change), equitable (outcomes), or systemic (racism)? “A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks,” observed Orwell. “It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier to have foolish thoughts.”

The post ORWELLIAN first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

May 27, 2021

THE COMMISSION

John Russell Pope’s proposal for the Lincoln Memorial, 1911-12

President Biden’s decision to appoint four new members to the U.S Commission of Fine Arts has focussed public attention on this body. The New York Times rather snarkily described the Commission as a “low-key, earnest design advisory group”; just tell that to the architectural firms that have had to undergo detailed and sometimes severe reviews. Not all the reporting has been accurate; the Commission does not report to Congress, nor is the chair appointed, he or she is elected by the commissioners.

The Commission of Fine Arts was created in 1909 personally by President Theodore Roosevelt to act as an aesthetic watchdog over the urban makeover of Washington, D.C. that produced the National Mall, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Jefferson Memorial, as well as an extensive urban park system. Congress formalized Roosevelt’s decision a year later. The Commission reviews the designs of new federal buildings, monuments, and memorials in the District, as well as all new buildings—private as well as public—in the monumental core of the city. Over the years the Commission’s responsibilities have grown to include reviewing overseas military cemeteries, all coins and medals issued by the U.S. Mint, and heraldic designs of the Army. When Charles Freer founded the Freer Gallery he stipulated that all acquisitions (and deaccessions) be approved by the Commission, and when I was a member, one of our more pleasurable duties was to visit the Gallery and inspect their latest acquisitions.

There are seven members of the Commission, appointed by the President for four-year terms. The first commissioners included Daniel Burnham, Thomas Hastings (architect of the New York Public Library), Cass Gilbert (architect of the Supreme Court), the sculptor Daniel Chester French, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. Such prominent architects as Charles A. Platt, John Russell Pope, Henry Bacon, and Paul Cret later served; so did the artists Lee Lawrie and Paul Manship. The postwar period saw such leading designers as Pietro Belluschi, Wallace K. Harrison, Hideo Sasaki, Gordon Bunshaft, and Kevin Roche. It also included leading figures in the design field such as Aline Saarinen and Adele Chatfield-Taylor. There have been periods when appointments to the Commission have been political, but generally it is composed of architects, landscape architects, and artists. J. Carter Brown, the director of the National Gallery, was chair for three decades, and was followed by his successor at the Gallery, Rusty Powell. Commissioners serve at the pleasure of the president, and President Biden was entirely within his rights to make replacement appointments, although this is the first time a president has done so. It is a shame that the National Gallery is no longer represented, and I hope a landscape architect will join the Commission in the not too distant future.

The post THE COMMISSION first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

May 26, 2021

THE BEDPAN LINE

Bedpan, 1501-1700

Bedpan, 1501-1700I spent some time in a hospital room recently, visiting. The atmosphere was distinctly technological: screens, flashing lights, mechanical beds, not to mention numerous pharmaceuticals. I was brought up short by the appearance of a device that was more Florence Nightingale than Big Pharma: a bedpan. The bedpan was plastic, but I’d always thought of them as glazed metal. Early bedpans were made of ceramic and were heavy affairs. A famous bedpan, made of pewter, belonged to Martha and George Washington, but the device is much older than the Colonial period. The Science Museum in London has a collection of old British and French bedpans, ingenious designs in which the hollow handle doubles as a pouring spout. The oldest model, made of glazed earthenware, is vaguely dated “1501-1700.” The earlier date suggests that the origin of the bedpan might be medieval. That inventive period gave us the windmill, the printing press, and eyeglasses—and perhaps the bedpan. Apropos of nothing, I came across a humorous reference: the British suburban railway line linking the city of Bedford to London’s St Pancras station is nicknamed the Bedpan Line.

The post THE BEDPAN LINE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

May 11, 2021

PHILLY PHLASH

Helmut Jahn (1940-2021) died three days ago in an unfortunate bicycle accident. I don’t know if the world is a better place thanks to his flashy, in-your-face architecture, but his Liberty Place project, once the tallest in Philadelphia, does not make the city a better place. Ostensibly a take-off of the Chrysler Building, the pair of skyscrapers has always struck me as an uncomfortable presence on the skyline. First off all, Philadelphia has always had its own distinctive tall buildings, beginning with John McArthur, Jr.’s city hall tower (1894), Howe & Lescaze’s PSFS Building (1932), and Ritter & Shay’s U. S. Customs House (1934), so an ersatz New York tower seems out of place. Unlike Van Alen’s Art Deco original, Jahn’s building is modernist, and it suffers a problem common to most modernist work, that is, its big formal moves are unsupported by appropriate detail. There are no equivalents to the Chrysler’s hood-ornament eagle heads, the hubcap decorations, and the sunburst spire. The result is like a preliminary sketch–or a rough plasticine model. Moreover, to make matters worse, there are two towers (built in 1987 and 1990), which undercuts the effect. It is possible to make beautiful twin towers, as Emery Roth’s 1930s San Remo and El Dorado apartment buildings in Manhattan demonstrate, but there is nothing evocative about Jahn’s dumpy pair.

Helmut Jahn (1940-2021) died three days ago in an unfortunate bicycle accident. I don’t know if the world is a better place thanks to his flashy, in-your-face architecture, but his Liberty Place project, once the tallest in Philadelphia, does not make the city a better place. Ostensibly a take-off of the Chrysler Building, the pair of skyscrapers has always struck me as an uncomfortable presence on the skyline. First off all, Philadelphia has always had its own distinctive tall buildings, beginning with John McArthur, Jr.’s city hall tower (1894), Howe & Lescaze’s PSFS Building (1932), and Ritter & Shay’s U. S. Customs House (1934), so an ersatz New York tower seems out of place. Unlike Van Alen’s Art Deco original, Jahn’s building is modernist, and it suffers a problem common to most modernist work, that is, its big formal moves are unsupported by appropriate detail. There are no equivalents to the Chrysler’s hood-ornament eagle heads, the hubcap decorations, and the sunburst spire. The result is like a preliminary sketch–or a rough plasticine model. Moreover, to make matters worse, there are two towers (built in 1987 and 1990), which undercuts the effect. It is possible to make beautiful twin towers, as Emery Roth’s 1930s San Remo and El Dorado apartment buildings in Manhattan demonstrate, but there is nothing evocative about Jahn’s dumpy pair.

The post PHILLY PHLASH first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

May 6, 2021

THE FOG OF LIFE

A recent conversation on GoodFellows, a podcast from the Hoover Institution, concerned Niall Ferguson’s recent book Doom, and included a comparison between military and civilian planning. This brought to mind what I have always thought was a weakness of the discipline of city planning. Good military planning, as I understand it, is based on preparing for “what if,” that is, developing different scenarios. What if this happens, or that happens? City planning is different, more like advocacy, that is, what should happen. This advocacy is based on certainties: open space is good, density is good—or bad, depending. The problem is that what planners think should happen—separation of pedestrians and cars, superblocks, megastructures—often runs into trouble when it hits the fog of life. Louis Kahn posited a city of mammoth parking structures, whereas Uber reduces the need for car ownership; Paul Rudolph imagined megastructures, whereas cities grow in unexpected directions—small increments help. Years ago, Jane Jacobs pointed out that the city was much too complicated to succumb to simple nostrums; better by far to learn from what was actually happening on the ground.

A recent conversation on GoodFellows, a podcast from the Hoover Institution, concerned Niall Ferguson’s recent book Doom, and included a comparison between military and civilian planning. This brought to mind what I have always thought was a weakness of the discipline of city planning. Good military planning, as I understand it, is based on preparing for “what if,” that is, developing different scenarios. What if this happens, or that happens? City planning is different, more like advocacy, that is, what should happen. This advocacy is based on certainties: open space is good, density is good—or bad, depending. The problem is that what planners think should happen—separation of pedestrians and cars, superblocks, megastructures—often runs into trouble when it hits the fog of life. Louis Kahn posited a city of mammoth parking structures, whereas Uber reduces the need for car ownership; Paul Rudolph imagined megastructures, whereas cities grow in unexpected directions—small increments help. Years ago, Jane Jacobs pointed out that the city was much too complicated to succumb to simple nostrums; better by far to learn from what was actually happening on the ground.

The post THE FOG OF LIFE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

April 19, 2021

FEELING GOOD

Walking down a corridor of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia I came across a decorative mosaic panel hanging on the wall. An accompanying label explains that it is a portion of the lobby floor of the Elm Building, which was demolished in 1981 to make room for the building in which I’m standing. The Elm Building was built by the hospital in 1901, a photograph on the hospital website shows an attractive one-story brick and limestone building with a pedimented temple front. Clearly a building of some consequence, it housed administration offices and an assembly room. The unidentified architect took trouble with the lobby floor, and imported the tiles from Germany, the work of Sinziger Mosaikplattenfabrik, located in northern Rhineland-Palatinate. The mosaic pattern replicates ancient Roman tile work. Nice stuff. Increasingly, I am coming to the Hemingwayesque conclusion that a “good building” is simply one that makes you feel good. This piece of saved floor does. The building that replaced it—not so much.

Walking down a corridor of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia I came across a decorative mosaic panel hanging on the wall. An accompanying label explains that it is a portion of the lobby floor of the Elm Building, which was demolished in 1981 to make room for the building in which I’m standing. The Elm Building was built by the hospital in 1901, a photograph on the hospital website shows an attractive one-story brick and limestone building with a pedimented temple front. Clearly a building of some consequence, it housed administration offices and an assembly room. The unidentified architect took trouble with the lobby floor, and imported the tiles from Germany, the work of Sinziger Mosaikplattenfabrik, located in northern Rhineland-Palatinate. The mosaic pattern replicates ancient Roman tile work. Nice stuff. Increasingly, I am coming to the Hemingwayesque conclusion that a “good building” is simply one that makes you feel good. This piece of saved floor does. The building that replaced it—not so much.

The post FEELING GOOD first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

April 10, 2021

THE RIGHT STUFF

The Associated Press reports that President Emanuelle Macron has approved a plan to rebuild the roof and spire of Notre-Dame cathedral exactly as it was before last year’s fire. Hurrah! That means an oaken structure supporting a lead roof and a spire according to the nineteenth-century design of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. A thousand three-foot diameter oaks are being felled to provide the timber, which must be allowed to season for at least eighteen months. According to the cathedral’s rector, Patrick Chauvet, the entire reconstruction is expected to take ten to fifteen years.

The Associated Press reports that President Emanuelle Macron has approved a plan to rebuild the roof and spire of Notre-Dame cathedral exactly as it was before last year’s fire. Hurrah! That means an oaken structure supporting a lead roof and a spire according to the nineteenth-century design of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. A thousand three-foot diameter oaks are being felled to provide the timber, which must be allowed to season for at least eighteen months. According to the cathedral’s rector, Patrick Chauvet, the entire reconstruction is expected to take ten to fifteen years.

The post THE RIGHT STUFF first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

April 6, 2021

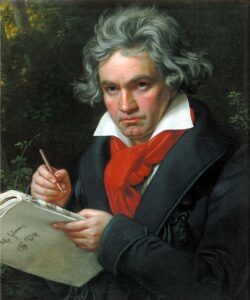

ROLL OVER BEETHOVEN

A musician friend sent me a recent article in the Telegraph reporting that “Musical notation has been branded ‘colonialist’ by Oxford professors hoping to reform their courses to focus less on white European culture . . . Academics are deconstructing the university’s music offering after facing pressure to ‘decolonise’ the curriculum following the Black Lives Matter protests.” According to the British newspaper, music professors said the classical repertoire taught at Oxford, which spans works by Mozart and Beethoven, focuses too much on ‘white European music from the slave period.’” Actually, Habsburg Austria-Hungary, where the pair lived and worked, was not a colonial power hence hardly involved in the slave trade, but you get the idea. So it goes in music teaching in a venerable university. Can architecture be far behind? The field seems ripe for revision, after all, Western architecture is—or was, until very recently—rooted in ancient Rome and Greece, both slave-owning societies. Out, damned column!

A musician friend sent me a recent article in the Telegraph reporting that “Musical notation has been branded ‘colonialist’ by Oxford professors hoping to reform their courses to focus less on white European culture . . . Academics are deconstructing the university’s music offering after facing pressure to ‘decolonise’ the curriculum following the Black Lives Matter protests.” According to the British newspaper, music professors said the classical repertoire taught at Oxford, which spans works by Mozart and Beethoven, focuses too much on ‘white European music from the slave period.’” Actually, Habsburg Austria-Hungary, where the pair lived and worked, was not a colonial power hence hardly involved in the slave trade, but you get the idea. So it goes in music teaching in a venerable university. Can architecture be far behind? The field seems ripe for revision, after all, Western architecture is—or was, until very recently—rooted in ancient Rome and Greece, both slave-owning societies. Out, damned column!

The post ROLL OVER BEETHOVEN first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

April 2, 2021

THE TROPICAL SHIRT

In a colloquium that took place during the 2016 Driehaus Prize ceremonies in Chicago, Andrés Duany made an interesting observation. He pointed out that Florida Panhandle resort towns such as Seaside, Rosemary Beach, and Alys Beach—all planned by his firm DPZ—were actually urban experimental testbeds with potentially long-term effects. “Americans are willing in the circumscription of a resort experience to try anything,” he said. He speculated that the people who holidayed in these walkable, dense, traditionally designed resort towns—so different from their everyday suburban communities—were affected, that is changed, by the experience. Now, I’m a great admirer of the Seaside prototype, which introduced a new model to holiday real estate: the resort as an actual village. Although the idea had earlier surfaced in Europe—Portmeirion in Wales and Port Grimaud in France—it was new to the U.S. But an urban testbed? I remember an incident, long ago, when my wife and I spent a holiday week in Martinique. We were in a good mood and while there Shirley bought a floral dress and I a tropical shirt. After we returned home to Canada we unpacked. We stared at the colorful clothes. What had we been thinking? They had looked so attractive in the French Antilles, but here they looked entirely out of place. That’s the trouble with vacations; they are an escape, from routine, from the everyday, from the mundane.

In a colloquium that took place during the 2016 Driehaus Prize ceremonies in Chicago, Andrés Duany made an interesting observation. He pointed out that Florida Panhandle resort towns such as Seaside, Rosemary Beach, and Alys Beach—all planned by his firm DPZ—were actually urban experimental testbeds with potentially long-term effects. “Americans are willing in the circumscription of a resort experience to try anything,” he said. He speculated that the people who holidayed in these walkable, dense, traditionally designed resort towns—so different from their everyday suburban communities—were affected, that is changed, by the experience. Now, I’m a great admirer of the Seaside prototype, which introduced a new model to holiday real estate: the resort as an actual village. Although the idea had earlier surfaced in Europe—Portmeirion in Wales and Port Grimaud in France—it was new to the U.S. But an urban testbed? I remember an incident, long ago, when my wife and I spent a holiday week in Martinique. We were in a good mood and while there Shirley bought a floral dress and I a tropical shirt. After we returned home to Canada we unpacked. We stared at the colorful clothes. What had we been thinking? They had looked so attractive in the French Antilles, but here they looked entirely out of place. That’s the trouble with vacations; they are an escape, from routine, from the everyday, from the mundane.

The post THE TROPICAL SHIRT first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

March 30, 2021

PLUS ÇA CHANGE

As one gets older one tends to spend an inordinate amount of time visiting hospitals. Ours is Pennsylvania Hospital, which bills itself as “the first in the nation” and was co-founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1751. The original building was designed in 1754 by Franklin’s friend, Samuel Rhoads (1711-84), a self-taught carpenter/architect. Rhoads, who was later a delegate to the First Continental Congress and would serve as the city’s mayor, laid out two wings connected to a central pavilion. Only the east wing, a sturdy Georgian brick structure, was built before the Revolution. The west wing and the central pavilion, which included a medical library, were completed in 1805 by David Evans, Jr., according to Rhoads’s general design but in a more refined Adamesque Federal style. While the delicate facade of the entrance pavilion features prominently in the hospital’s literature, the actual entrance is elsewhere, via a banal addition built in the 1970s. No cupolas, no basketweave brickwork or carefully proportioned windows, instead a concrete canopy and a “just the fact ma’am” interior of low suspended ceilings, more like a Days Inn than a civic landmark. Over the last two centuries, while medical expertise has grown remarkably, architectural ambition, not to mention competence, appears sadly diminished.

As one gets older one tends to spend an inordinate amount of time visiting hospitals. Ours is Pennsylvania Hospital, which bills itself as “the first in the nation” and was co-founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1751. The original building was designed in 1754 by Franklin’s friend, Samuel Rhoads (1711-84), a self-taught carpenter/architect. Rhoads, who was later a delegate to the First Continental Congress and would serve as the city’s mayor, laid out two wings connected to a central pavilion. Only the east wing, a sturdy Georgian brick structure, was built before the Revolution. The west wing and the central pavilion, which included a medical library, were completed in 1805 by David Evans, Jr., according to Rhoads’s general design but in a more refined Adamesque Federal style. While the delicate facade of the entrance pavilion features prominently in the hospital’s literature, the actual entrance is elsewhere, via a banal addition built in the 1970s. No cupolas, no basketweave brickwork or carefully proportioned windows, instead a concrete canopy and a “just the fact ma’am” interior of low suspended ceilings, more like a Days Inn than a civic landmark. Over the last two centuries, while medical expertise has grown remarkably, architectural ambition, not to mention competence, appears sadly diminished.

The post PLUS ÇA CHANGE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers