Witold Rybczynski's Blog, page 9

March 19, 2022

NOT QUITE ALONE

Madrid, April 1976

It is a curious thing, this new solitude of mine. More than one person has told me “You will always have the memories of your life together.” Well, I suppose that’s true, but life exists in the present, not the past, and it is in my daily routines that Shirley is most present. After almost five decades, many of my habits are entwined with hers: how I cook, or shop, or simply look at the world. There is a downside: many of the things we did together—eating out, traveling, going to a museum or a concert, watching Jeopardy—have lost their appeal. These things only remind me that she is no longer able to enjoy them. But every time I do the laundry I remember her instructions; take care of this, make sure of that. I am alone, and yet not quite.

The post NOT QUITE ALONE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

March 16, 2022

THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

Robert A. M. Stern has just published Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture. This is not a review; I’ve only read the first chapter—on Amazon—which details the author’s childhood. But Stern’s book is not exactly an autobiography; the publisher calls it “a personal and candid assessment of contemporary architecture and his fifty years of practice.” In fact, architectural memoirs are few and far between. With the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously unreliable An Autobiography, I only know of two modern examples, Nathaniel Owings’s The Spaces in Between: An Architect’s Journey (1973), and A. Eugene Kohn’s The World by Design: The Story of a Global Architecture Firm (2019). I think there are a number of explanations. Writers keep journals; architects carry sketchbooks—theirs is a visual not a literary imagination. More to the point, architecture is a profession, which makes candid recollections tricky, like telling tales out of school. I once asked Gene Kohn about a recent KPF project that seemed to me awkward. “Yes,” he answered. “That one got away from us.” We were, of course, speaking privately. Difficult clients, design mistakes, and missed opportunities are a part of every architect’s “journey,” but they are always discreetly kept out of the public eye.

Robert A. M. Stern has just published Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture. This is not a review; I’ve only read the first chapter—on Amazon—which details the author’s childhood. But Stern’s book is not exactly an autobiography; the publisher calls it “a personal and candid assessment of contemporary architecture and his fifty years of practice.” In fact, architectural memoirs are few and far between. With the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously unreliable An Autobiography, I only know of two modern examples, Nathaniel Owings’s The Spaces in Between: An Architect’s Journey (1973), and A. Eugene Kohn’s The World by Design: The Story of a Global Architecture Firm (2019). I think there are a number of explanations. Writers keep journals; architects carry sketchbooks—theirs is a visual not a literary imagination. More to the point, architecture is a profession, which makes candid recollections tricky, like telling tales out of school. I once asked Gene Kohn about a recent KPF project that seemed to me awkward. “Yes,” he answered. “That one got away from us.” We were, of course, speaking privately. Difficult clients, design mistakes, and missed opportunities are a part of every architect’s “journey,” but they are always discreetly kept out of the public eye.

The post THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

March 4, 2022

NOT INTERESTED

In this difficult time the famous Leon Trotsky quote comes to mind: “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

In this difficult time the famous Leon Trotsky quote comes to mind: “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

The post NOT INTERESTED first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

February 15, 2022

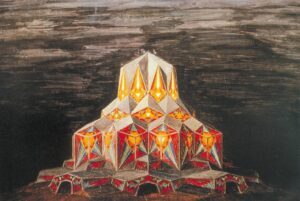

CRYSTAL CITY

“The City Crown,” Bruno Taut, 1919.

Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) was a German writer of the turn of the nineteenth century; today we would call him a sci-fi author. In 1914 he wrote a novel with the unwieldily title The Grey Cloth and Ten Percent of White. The protagonist is an architect, more specifically a “glass architect,” and Scheerbart dedicated the book to Bruno Taut, a Berlin architect who promoted the idea of revolutionary all-glass buildings. Glasarchitektur (the title of another Scheerbart book) was an avant-garde obsession; Taut imagined “glowing crystal houses and floating, ever-changing glass ornaments.” When I look out my window I can see his crystal city come to life. It is certainly glowing, especially on a sunny day. Ever-changing? Well sort of. What is missing is the color and jewel-like qualities of Taut’s rather beautiful sketches. And the mute glass boxes undermine traditional architectural qualities such as mass and shadow, structure and weight, but I suppose that was the whole point of glasarchitektur.

The post CRYSTAL CITY first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

February 7, 2022

HOUSE MEMORY

Alvaro Ortega, Jon Boone, Breuer, WR and my old BMW 1600

I met Marcel Breuer in October 1973 at his home in New Canaan, Connecticut. He designed the house, known as Breuer House II, in 1951, a low-slung affair with rough fieldstone walls, a slate floor, and an unpainted wood ceiling. Plate-glass windows looked out on a Calder stabile on the lawn, and nearby woods. We ate lunch sitting on Cesca chairs at a table that consisted of a thick granite slab. Breuer himself, 71, was courtly and engaging. Philip Johnson once called him a “peasant mannerist,” and there was something appealingly simple in his demeanor, as in the house itself. I admire Breuer’s houses, but that visit apart I have never actually seen one—I know them only from black-and-white photographs in books. So, when James S. Russell writes in the New York Times on the occasion of the demolition of Breuer’s Geller House, “Regrettably, the lessons such houses teach are lost as they grow fewer all the time,” I must disagree. The demolition of a public building—or any building in public view—can be like the loss of an old friend, but when a private house in rural surroundings is torn down, it is more like the proverbial tree falling unheard in the forest. I was lucky to see Breuer House II—he sold it three years later. In 2007, the house was disfigured—to my eye—by an intrusive glass addition designed by Toshiko Mori, but my memory of the visit and the old black and white photos taken when it was occupied by Constance and Marcel Breuer are still there. That house will live on.

The post HOUSE MEMORY first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

February 4, 2022

NOT THE POST OFFICE

One of the stated goals of the American Institute of Architects Strategic Plan 2021-2025 is “To ensure equity in the profession.” Equity may apply to pay, work opportunities, awards, or even, I suppose, to the makeup of the profession, that is, it should reflect the population as a whole. But the architectural profession is not the post office. It depends on the availability and preferences of clients, it depends on the swings of the economy, and success relies on individual drive and talent. Architecture is a zero-sum game, of course: there are a limited number of building commissions at any one time and if one architect gets the job, another doesn’t. Some of the most prominent commissions—the ones that build a reputation—are the result of architectural competitions. In these blind auditions, only the most talented have a chance to shine. And talent is not evenly distributed; “cream rises” as Stewart Brand memorably wrote in the Whole Earth Catalog. Hard to put your thumb on that scale. Finally, opening up architecture implies increasing the size of the profession. But there are already too many architects! When I was a student in Canada in the 1960s, there were 6 schools of architecture—I know because on a federally-funded scholarship tour six of us fitted into a large station wagon. Today there are 12 schools. The US, with nine times the population, has not 108 but 140 NAAB-accredited schools.

One of the stated goals of the American Institute of Architects Strategic Plan 2021-2025 is “To ensure equity in the profession.” Equity may apply to pay, work opportunities, awards, or even, I suppose, to the makeup of the profession, that is, it should reflect the population as a whole. But the architectural profession is not the post office. It depends on the availability and preferences of clients, it depends on the swings of the economy, and success relies on individual drive and talent. Architecture is a zero-sum game, of course: there are a limited number of building commissions at any one time and if one architect gets the job, another doesn’t. Some of the most prominent commissions—the ones that build a reputation—are the result of architectural competitions. In these blind auditions, only the most talented have a chance to shine. And talent is not evenly distributed; “cream rises” as Stewart Brand memorably wrote in the Whole Earth Catalog. Hard to put your thumb on that scale. Finally, opening up architecture implies increasing the size of the profession. But there are already too many architects! When I was a student in Canada in the 1960s, there were 6 schools of architecture—I know because on a federally-funded scholarship tour six of us fitted into a large station wagon. Today there are 12 schools. The US, with nine times the population, has not 108 but 140 NAAB-accredited schools.

The post NOT THE POST OFFICE first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

January 15, 2022

LET’S PRETEND

I’ve been watching a building going up a block from where I live in Philadelphia. 222 Market Street is a nineteen-story office block. The structure is steel, and except for a couple of odd slanted columns at one end, it is the sort of regular frame of I-beams that engineers have been designing for well over a hundred years; the first steel framed building in the U.S., was Burnham & Root’s ten-story Rand McNally Building in Chicago, erected in 1890. When the Market Street steel was topped off the structure reminded me of the high-rises that Mies van der Rohe put up in Chicago in the 1950s. Mies followed the age-old practice—going back to the ancient Greeks—of expressing the structure in the architecture; in his case in a very bare-bones fashion. That isn’t good enough for the architects of 222 Market (the global firm Gensler), whose approach I can only characterize as Let’s Pretend. The skin of the building, a combination of glass and flimsy-looking prefab glazed brick panels, is designed to give the impression that the building is composed of three-story high stacked-up boxes. In other words, architecture has been replaced by packaging.

I’ve been watching a building going up a block from where I live in Philadelphia. 222 Market Street is a nineteen-story office block. The structure is steel, and except for a couple of odd slanted columns at one end, it is the sort of regular frame of I-beams that engineers have been designing for well over a hundred years; the first steel framed building in the U.S., was Burnham & Root’s ten-story Rand McNally Building in Chicago, erected in 1890. When the Market Street steel was topped off the structure reminded me of the high-rises that Mies van der Rohe put up in Chicago in the 1950s. Mies followed the age-old practice—going back to the ancient Greeks—of expressing the structure in the architecture; in his case in a very bare-bones fashion. That isn’t good enough for the architects of 222 Market (the global firm Gensler), whose approach I can only characterize as Let’s Pretend. The skin of the building, a combination of glass and flimsy-looking prefab glazed brick panels, is designed to give the impression that the building is composed of three-story high stacked-up boxes. In other words, architecture has been replaced by packaging.

The post LET’S PRETEND first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

December 30, 2021

THE TROPIC OF GRIEF

Shortly after my wife died, a friend emailed me a quote from Julian Barnes’s Levels of Life, which deals in part with the death of his wife of twenty-nine years. “This is what those who haven’t crossed the tropic of grief often fail to understand,” Barnes wrote, “the fact that someone has died may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.” It struck me as an intellectual conceit rather than a real insight. But I ordered the book from Abebooks. It was well written, as I had expected, and it was full of aperçus such as: “There are two essential types of loneliness: that of not having found someone to love, and that of having been deprived of the one you did love. The first is worse.” But I was still unconvinced that someone who had died could nevertheless exist. No longer. For me, Shirley does exist, not the memory of her, but her actual presence in our home—and in my consciousness. “I talk to her constantly,” was another Barnes comment that struck me as farfetched when I first read it. Now, months later, I must agree, for I, too, talk to her constantly.

Shortly after my wife died, a friend emailed me a quote from Julian Barnes’s Levels of Life, which deals in part with the death of his wife of twenty-nine years. “This is what those who haven’t crossed the tropic of grief often fail to understand,” Barnes wrote, “the fact that someone has died may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.” It struck me as an intellectual conceit rather than a real insight. But I ordered the book from Abebooks. It was well written, as I had expected, and it was full of aperçus such as: “There are two essential types of loneliness: that of not having found someone to love, and that of having been deprived of the one you did love. The first is worse.” But I was still unconvinced that someone who had died could nevertheless exist. No longer. For me, Shirley does exist, not the memory of her, but her actual presence in our home—and in my consciousness. “I talk to her constantly,” was another Barnes comment that struck me as farfetched when I first read it. Now, months later, I must agree, for I, too, talk to her constantly.

The post THE TROPIC OF GRIEF first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

December 24, 2021

FAME

I’ve just finished reading Roxanne Williamson’s American Architects and the Mechanics of Fame (1991). Despite some interesting historical research into the professional connections between architects and their mentors/employers, it is not a very satisfying book. The first question to ask about fame is “Famous among whom?” The public, the architectural profession, the critics, architectural historians? Williamson considered only the last group. She compiled an “Index of Fame” by consulting twenty histories of architecture and four encyclopedias, and counting the number of times individual architects were mentioned. Since most recent historians (Giedion, Hitchcock, Banham, Pevsner, Fitch, and Scully) have been interested in the history of modernism, this naturally skews the results. An architect such as Rudolph Schindler, who designed a handful of interesting private houses is more “famous” than Paul Philippe Cret, who built major civic buildings such as the Federal Reserve, the Detroit Institute of Art, the Walter Reed Hospital, and much of the campus of the University of Texas in Austin. The second problem is that fame is treated as an absolute quality. But, as the old saying goes, “All glory is fleeting.” Sixty years ago, when I was a student, the famous architects we admired were Aldo Van Eyck, Peter and Allison Smithson, and Shadrach Woods, long since forgotten (none appear in Williamson’s book). But neither does the “Index of Fame” include Norman Foster, who, in the years since the research for this book was conducted (the late 1970s) has become the world’s most recognized architect (and the richest). If you are going to study fame—a dubious undertaking—you must incorporate a sliding time scale: famous today, not so famous tomorrow, and vice versa.

I’ve just finished reading Roxanne Williamson’s American Architects and the Mechanics of Fame (1991). Despite some interesting historical research into the professional connections between architects and their mentors/employers, it is not a very satisfying book. The first question to ask about fame is “Famous among whom?” The public, the architectural profession, the critics, architectural historians? Williamson considered only the last group. She compiled an “Index of Fame” by consulting twenty histories of architecture and four encyclopedias, and counting the number of times individual architects were mentioned. Since most recent historians (Giedion, Hitchcock, Banham, Pevsner, Fitch, and Scully) have been interested in the history of modernism, this naturally skews the results. An architect such as Rudolph Schindler, who designed a handful of interesting private houses is more “famous” than Paul Philippe Cret, who built major civic buildings such as the Federal Reserve, the Detroit Institute of Art, the Walter Reed Hospital, and much of the campus of the University of Texas in Austin. The second problem is that fame is treated as an absolute quality. But, as the old saying goes, “All glory is fleeting.” Sixty years ago, when I was a student, the famous architects we admired were Aldo Van Eyck, Peter and Allison Smithson, and Shadrach Woods, long since forgotten (none appear in Williamson’s book). But neither does the “Index of Fame” include Norman Foster, who, in the years since the research for this book was conducted (the late 1970s) has become the world’s most recognized architect (and the richest). If you are going to study fame—a dubious undertaking—you must incorporate a sliding time scale: famous today, not so famous tomorrow, and vice versa.

The post FAME first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

December 19, 2021

M. ROGERS

The architect Richard Rogers, 88, died yesterday. His obituaries invariably started by mentioning the Centre Pompidou, the seriously ill-conceived museum that turned the youthful Rogers and his partner Renzo Piano, into overnight sensations. I remember that when I was a member of the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., a now seasoned Rogers came before us to present 300 New Jersey Avenue, an addition to an old office building near Union Station. The limestone building was designed in 1935 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (the architects of the Empire State Building), a fine example of early American modernism: a blend of practical engineering, Beaux-Arts planning, and an Art Deco sensibility. When Rogers presented his concept—a ten-story glass wing that created a triangular atrium between the new and the old buildings—the sketchy drawings and a patchy model were hard to understand. Exactly where was the design heading? Over subsequent presentations, the project slowly jelled, but was still hard to follow. A few years later, my fellow commissioner, Michael McKinnell, and I went to see the built result. The jungle-gym aesthetic, structural struts, and brash colors, were world’s away from Shreve, Lamb & Harmon’s orderly design. “That was then, this is now,” seemed to be Rogers’s message. Contrasting the new with the old has become an architectural cliché that often leaves the old in its dust, but here we came away admiring both buildings. Both evinced a strong sense of conviction—a key architectural quality. Chapeau, M. Rogers!

The architect Richard Rogers, 88, died yesterday. His obituaries invariably started by mentioning the Centre Pompidou, the seriously ill-conceived museum that turned the youthful Rogers and his partner Renzo Piano, into overnight sensations. I remember that when I was a member of the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C., a now seasoned Rogers came before us to present 300 New Jersey Avenue, an addition to an old office building near Union Station. The limestone building was designed in 1935 by Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (the architects of the Empire State Building), a fine example of early American modernism: a blend of practical engineering, Beaux-Arts planning, and an Art Deco sensibility. When Rogers presented his concept—a ten-story glass wing that created a triangular atrium between the new and the old buildings—the sketchy drawings and a patchy model were hard to understand. Exactly where was the design heading? Over subsequent presentations, the project slowly jelled, but was still hard to follow. A few years later, my fellow commissioner, Michael McKinnell, and I went to see the built result. The jungle-gym aesthetic, structural struts, and brash colors, were world’s away from Shreve, Lamb & Harmon’s orderly design. “That was then, this is now,” seemed to be Rogers’s message. Contrasting the new with the old has become an architectural cliché that often leaves the old in its dust, but here we came away admiring both buildings. Both evinced a strong sense of conviction—a key architectural quality. Chapeau, M. Rogers!

The post M. ROGERS first appeared on WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI.

Witold Rybczynski's Blog

- Witold Rybczynski's profile

- 178 followers