John G. Messerly's Blog, page 65

October 31, 2018

Religion as Community

Dr. Darrell Arnold, Professor of Philosophy

Note – My last post elicited multiple thoughtful comments from readers but I thought that Dr. Darrell Arnold’s were worth reprinting in their entirety. I have known Dr. Arnold for more than 30 years and he is a careful and conscientious thinker whose thought I highly value. Here is Dr. Arnold’s commentary followed by a brief rejoinder.

Clearly, religion has done and continues to do much harm. And most of the everyday religious dogmas should be taken no more seriously than the idea that Athena sprang from the head of Zeus. But beyond providing individual consolation, which you note, religions also provide much more. They often provide the impetus for social justice, provide individuals with a strong sense of belonging, and through spiritual direction offer something akin to analytic counseling.

Major social justice movements of the 20th century and of the present have had strong religious impulses. We can look to the movements of which Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were leaders as examples. In Miami, through obligations associated with the Catholic University where I originally worked, I became involved with a Social Justice organization that works on local (progressive) politics that is comprised almost exclusively of Justice committees of local churches, synagogues, and mosques. These congregations do provide an infrastructure for social coordination at the local (and national) level. And it appears to me that many of the adherents … derive [ a sense of purpose] from that work “being their brother’s keeper” and from the sense of community that the organizations and the collective work provide.

The non-religious often lack the social bonds, outside of family, that religious organizations can provide, and they often lack the organizational infrastructure for collective social justice work. You’re probably familiar with Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community[image error]. He reflects on the lack of community in contemporary life and problems of social belonging and so on related to this. We can, of course, join Green Peace or the Sierra Club or various organizations and work together for good purposes. But it appears that there is a bit of a vacuum often left by those who leave their churches.

But these are a couple of the roles that religions also fulfill that can be important for a meaningful life. It was this social function of religion that Durkheim focused on more than the question of individual comfort or of religious experience (such as William James writes about). Those without religion (or those who hope that religion will fade) will likely do well to find other ways to facilitate community. This, I’m sure, is part of what is behind the efforts like Alain Botton’s School of Life, which has meetings in London and other places, or the various Atheist churches. Some of them couple that with some other functions of religion, such as philosophical counseling as a stand-in for spiritual direction.

Mostly what I’m getting at here is that there is more that religion provides people than the individual comfort of a supernatural belief system. Many of those things are vitally needed for many people to have a good life and are benefits of a caring community. Maybe that last phrase should be highlighted since I think that a lot of the appeal of religion comes down to that. For all the sicknesses of any religion I’ve encountered, you can often find in the midst of that elements of a caring community — at least some group of people who are focused on a moral life and who find meaning in acts of kindness toward individuals and in work for social causes greater than themselves.

Brief reply – I agree with everything Dr. Arnold writes here. Religions have done, and motivate believers to do, many good things. (And the corollary is that many non-religious persons have done terrible things.) Religions also provide a sense of community to many, especially in a culture like America where isolation is such a big problem. I really think that religions are social clubs as much as anything else. It was Kierkegaard I believe who said that when you tell someone what religion you belong to you are basically telling them who you hang out with. The social and emotional aspects of religion also explain why rational arguments have so little effect on believers.

October 28, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 2 – Religion and Meaning

… continued from a previous entry

Western Religions: Are They True?

Western monotheistic religions try to answer both the meaning of and the meaning in life questions with an overarching worldview. However, religions consist of multifarious beliefs, expressions, and experiences making them difficult to characterize. We could plausibly say there are as many religions as there are religious practitioners. But western religious answers to questions of meaning typically involve narratives and beliefs about gods, souls, and an afterlife.

Here are two examples from Christianity. The Westminster Shorter Catechism answers the question: “What is the chief end of Man?” with “Man’s chief end is to glorify God, and enjoy him forever.” The Baltimore Catechism answers, “Why did God make you?” with “God made me to know Him, to love Him, and to serve Him in this world, and to be happy with Him forever in heaven.” Similar ideas can be found in Judaism and Islam.

But such answers are highly problematic. The philosophical arguments for the existence of a God are notoriously weak, the concept of soul scientifically irrelevant, the evidence of an afterlife almost nil and contravened by experience. Religious beliefs are often superstitious and implausible, both an affront to the intellect and an insult of our best scientific knowledge. The gods that people believe in are almost certainly imaginary and science convincingly explains our tendency to believe in them. In other words, popular religious beliefs are almost certainly false.

Allegorical and less literal interpretations of religious beliefs are more intellectually palatable, but they are often still tethered to dubious claims about supernatural realities, miraculous divine intervention and the like. Sometimes these more sophisticated interpretations reject supernaturalism, but then they often cease to be what most people mean by religion—the God of pantheism, panentheism, process theology or death of god theology aren’t recognizable to most believers. Such obscure metaphysical speculations might provide insight if grounded in scientific knowledge, but usually they are not.

Philosophical theologians conversant with and appreciative of modern science often posit a “god of the philosophers” using the word God to mean a cause, reason, explanation, designer, or necessary being. I can’t rehash all the arguments for these various conceptions of gods except to say that the vast majority of contemporary philosophers don’t find those arguments convincing. I count myself among this majority. In my view, defenders of these arguments generally deceive themselves through motivated reasoning. They base their beliefs on what they want to believe, not on what is most likely to be true.

Still, I grant many persons derive meaning in life from their fervently held, emotionally satisfying religious beliefs, which is fine as long as they don’t try to impose those beliefs on others. I understand the deep desire to believe in truth, beauty, goodness, justice, the end of suffering and death, and the meaning of life. I realize that religious beliefs provide comfort to some people, and that is probably the best argument for accepting them. Life is hard, tranquility elusive, and living without appeal to gods, souls, and an afterlife takes courage. But wanting something to be true doesn’t make it so. As for me, I don’t want to believe, I want to know.

Western Religions: Are They Good?

Nonetheless, we pay a hefty price for this religious consolation—theocracy, fanaticism, hatred, war, etc. Moreover, religious institutions typically are anti-scientific, anti-democratic, anti-progressive, misogynistic, authoritarian, and medieval. Religion has opposed or still opposes free speech, the eradication of slavery, sex education, reproductive technologies, stem cell research, women’s and civil rights, and the advancement of science. It also encourages credulity and blind faith, which stand in opposition to the critical thinking we so desperately need.

Furthermore, many measures of social dysfunction strongly correlate with greater religiosity including homicides, large prison populations, infant mortality, sexually transmitted diseases, teenage births, political corruption, income inequality, and more. Perhaps all this is worth the comfort religious beliefs provide, or maybe this correlation doesn’t imply causation. But to the extent that religion causes much of this suffering, its consolations aren’t worth the price.

Consider that the cultural domination by Christianity during the Middle Ages resulted in some of the worst conditions in human history. Much the same could be said of religious hegemony in other times and places including the present day. And, if religion causes less harm today than it once did, that’s because its power has been reduced. Were that strength regained, the result would surely be disastrous, as anyone who studies history or lives in a theocracy will confirm.

Still, I admit religion isn’t the only anti-progressive force in the world—conservatives, plutocrats, and despots hate change too, especially if it affects their wealth and power. I should also note that many people evidently derive social and health benefits when surrounded by like-minded believers. Moreover, religion has promoted good things like education and healthcare for which I commend it. But secularists promote such things too without relying on supernatural justification. Consider that in today’s world the best places to live like the Scandinavian countries and Western Europe are also the least religious, while the worst places to live are generally the most overtly religious. I doubt this is coincidental.

As for me, I believe that western religion is as harmful as it is untrue. We will be better off the sooner we outgrow it. To put it simply religion is, in my view, an enemy of the future.

Western Religions: Do They Reveal Meaning?

Moreover, even if religious claims are literally true it’s not clear how they answer questions about life’s meaning. How does being a part of your God’s plan give your life meaning if being a part of your parent’s or country’s plan doesn’t? How does your God give your life meaning, if you can’t do that yourself? How can your God’s love give your life meaning if other people’s love doesn’t? How does living with your God forever provide meaning if living forever doesn’t do that by itself?

I’m not saying the above questions are unanswerable, just that their solutions aren’t obvious. We can imagine that some God makes sense of everything, but this article of faith doesn’t explain anything; it’s just a placeholder for our ignorance. Just as easy to imagine that this God enjoys watching our suffering, laughs at our efforts, and is entertained by our foibles—life may be the cruel joke of an immature, malevolent, or capricious God. Surely the mere existence of a God or gods doesn’t necessarily make life meaningful.

And, even if your God is real, do you really want to live forever with a being or beings apparently responsible for so much evil? Consider for a moment the innocent who are starving, homeless, incarcerated, and otherwise suffering unimaginably—as you read this now! Consider what fate has in store for all us. Given all this misery are the machinations of theologians about free will, the devil, or the necessity of evil to build our souls really satisfactory? No, they are not.

Thus Western religious answers to the questions of meaning are suspect because: 1) the supernatural realm is probably imaginary; 2) religion causes much harm; and 3) it isn’t clear how gods make life meaningful. If the truth, usefulness, and relevance of religion are suspect then its answers to questions about life’s meaning are suspect. As for me, Western religious answers to questions about meaning are non-starters; they simply aren’t available.

Eastern Religions and Meaning in Life

However, other religions concern themselves more with right action than right belief, with humility and compassion instead of creed and dogma. While this emphasis on right action rather than right belief can be found in the West, it is more prevalent in the self-salvation traditions of the East.

Of course, Eastern religions make use of metaphysically dubious notions like reincarnation, karma, lila, samsara, moksha, etc. and their practitioners can be as superstitious and spiteful as Western religious believers. Still, Eastern religions are typically less concerned with literal or historical truth and more accepting of modern science than Western religions. So our previous criticisms of Western religious beliefs don’t apply straightforwardly to Eastern religions.

Put differently, eastern religions typically focus less the meaning of life and more on finding meaning in life through activities such as searching for truth, being compassionate, reducing desires, or experiencing self-realization, bliss, liberation, or oneness with reality. Even to the extent there is a stated meaning of life—for example escaping the cycle of birth and rebirth in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism—the emphasis is on how to achieve this goal. In other words, eastern religions generally place more emphasis on acting to find enlightenment rather than believing that salvation depends on accepting certain propositions.

While all eastern religions largely share these traits, Buddhism is especially anti-dogmatic, anti-metaphysical, and practical. It provides instructions for good living, ending suffering, understanding reality, cultivating compassion and achieving mindfulness. Moreover its central tenets—that reality is radically impermanent and that we lack a core self—are consistent with findings in modern science. To the extent that it can be called a religion, as opposed to a philosophy of life, Buddhism is the best one that humans have created. For insight into finding meaning in life, Eastern wisdom devoid of supernaturalism is generally a good guide.

to be continued next week …

October 25, 2018

The Presocratics – Heraclitus

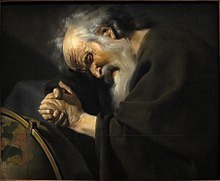

Heraclitus by Johannes Moreelse

Heraclitus by Johannes Moreelse

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

More than anything, Heraclitus is known as the philosopher of flux. As is famously attributed to him: “One cannot step in the same river twice” (D 91). Or as he similarly notes elsewhere: “As they step into the same rivers, other and still other waters flow upon them.”

Though it is important to understand Heraclitus as a great speculative philosopher who exceeds the Ionians in complexity, it is also important to see that he sets out similarly to the Ionians — so it is not without reason that Plato classifies all these early thinkers together as “Heracletians.” As Heraclitus says, indicating his similarity to the Ionians regarding the source of knowledge: “Whatever comes from sight, hearing, learning from experience: this I prefer” (D 55). Yet, seeing and hearing are not enough. To this, as the Ionians also appear to have clearly recognized, one must add understanding. “Eyes and ears are bad witnesses for those who have barbarian souls” (D 107).

While reasoning is as important as experience, it is not something that Heraclitus unhinges from experience. Heraclitus does not engage in the same abstract thought as Parmenides, speculating on the basis of an apriori logic. For him, the world around us, where one is born grows old dies, where all things change, serves as the basis of speculation. And that speculation should lead us to see the shifts and changes occur in accord with a law-like substratum. Here he posits a teaching of both logos (of word or mind or principle) and the elements. In this “All things are one.” Yet that unity contains diversity with the process: “Fire lives the death of earth and air lives the death of fire; water lives the death of air, earth that of water.” Individual objects in the world emerge and fade away out of a relationship of the transformation of elements through time.

Though Heraclitus will refer to the logos as divine, he does not speak of it as an external force acting upon a separate material. The process of the material change of the basic elements (with fire as the most basic) is not imposed by external deities, but is the order of the cosmos itself: “The ordering, the same for all, no god nor man has made, but it ever was and is and will be: fire everliving, kindled in measures and in measures going out.” Fire, the fundamental element, which also best symbolizes the transformation of the cosmos, transforms into the other elements in a process of continual change, where difference is fundamental, but difference persists in a process of unity.

One of Heraclitus’ fundamental themes is that this change in cosmos occurs through the balancing of oppositions. As he notes: “What is in opposition is in agreement, and the most beautiful harmony comes out of things in conflict (and all happens according to strife.)” Or more poetically, dismissing those who strive to see all conflict disappear: “They do not comprehend how being at variance it agrees with itself: it is a harmony turning back upon itself like a bow and a lyre.” This conflict between opposites is fundamental to the unfolding of the logos in the cosmos. In contrast to Hesiod who sees this conflict as a curse, Heraclitus posits that strife is not only “the father of all;” “strife is [also] justice.”

Beyond merely seeing how apparent conflicts complement one another, the “divine,” objective view of the cosmos that he stresses strives to rise above the common human-centric vision of reality. As he notes: “Sea is the most pure and most polluted water. For fish it is drinkable and life-preserving; for people it is undrinkable and deadly.”

Part of Heraclitus project is to reconceive of the divinity. It is now the cosmos as a whole or the logos that permeates it. Specific gods are part of this, but demythologized and viewed as functions of a law-like determinate universe. He notes the tension of his time, as myths are being secularized: “The one and only wise thing is and is not willing to be called by the name of Zeus.”

While this approach to reconceiving the gods is not unique to Heraclitus, he is more radical than most in that he not only rejects the traditional views of the gods, but also the rites and ceremonies honoring them, which he sees as having a corrosive effect on human beings. As he notes of ancient rites to Dionysos: “If it were not in honor of Dionysos that they organize a procession and sing the phallic hymn, what they do would be most shameless: but Hades and Dionysos are one and the same, in whose honor people rave and celebrate the Bacchic revelry.”

It is not the honoring of the gods that determine one’s fate and well-being. Rather: “Mans character is his fate.” The responsibility for what one becomes lies with oneself. Against this backdrop, Heraclitus notes: “the people should fight on behalf of the law as (they would) for (their) city wall.”

Heraclitus does re-conceive of the divine and of nature. One dovetails into the other. He bases his speculative reasoning on the senses but thinks it takes one beyond them. At least the knowledge that we have of him surpasses that of the Ionians by explicitly taking up not only issues of natural philosophy and metaphysics but also issues of ethics and teaching of the soul. In this, he among the Presocratics is the first to approach the systemic character of the later thought of Plato and Aristotle.

October 21, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 1 – Life and Meaning

(Author’s note. Over the next few weeks I’ll try to summarize my current but evolving views on life and meaning in once a week installments.)

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning

All my life I struggled to stretch my mind to the breaking point, until it began to creak, in order to create a great thought which might be able to give a new meaning to life, a new meaning to death, and to console [humanity]. ~ Nikos Kazantzakis

Two Questions about Life and Meaning

I distinguish between two basic questions concerning life and meaning.

The first is: “What is the meaning of life?” It might also be expressed: “Why does anything exist?” “Does anything matter?” “Does the universe have a purpose?” “What’s it all about?” This is the cosmic dimension of the question. It asks if there is a deep explanation or universal narrative that would make sense of everything, including us.

The second is: “Can I find meaning in life?” It might also be expressed: “What the point of my life?” “Does my life matter?” “What kind of life is meaningful?” “How should I live?” This is the individual dimension of the question. It asks if there is a valuable, significant, or worthwhile way of living that prevents life from being futile, pointless, or absurd.

Thus the often-asked, singular question, “what is the meaning of life?” is really a marker or an amalgam for all the above questions.

Putting our two main questions together leaves four possible answers:

1) Both the cosmos and our individual lives are (ultimately) meaningful;

2) Both the cosmos and our individual lives are (ultimately) meaningless;

3) The cosmos is (ultimately) meaningful but we can still live meaningless lives;

4) The cosmos is (ultimately) meaningless but we can still live meaningful lives;

What Do We Mean by Meaning?

The cosmos or an individual life is meaningful if it is purposeful, valuable, or significant. Furthermore, a meaningful cosmos contains things like truth, beauty, goodness, justice, joy, and love, while a meaningful life entails flourishing, satisfaction, contentment, and moral goodness. (While happy, moral, and meaningful lives aren’t identical, I believe they mostly overlap. Thus I won’t distinguish between them further.)

Put differently, both a meaningful cosmos and a meaningful life matter, they are good, and they are long-lasting. The more they matter, the better they are, and the longer they last, the more meaningful they are. In other words, what I call a fully meaningful reality is the best one that can be, and a fully meaningful life is the best one that we can live.

Note too that meaning varies over time. The cosmos may be more or less meaningful now than it will be in the future—it may one day become perfectly meaningful, totally meaningless, or something in between. Individual lives may also become more or less meaningful over time, and their meaning also varies from person to person. In other words, meaning is a gradient good.

However, a meaningful life isn’t necessarily devoid of all obstacles for many meaningful projects —developing our talents, educating our minds, raising our children—involve disappointment that is often at odds with our momentary happiness. I’m not implying that suffering is good or desirable, simply that, for now, it often accompanies our attempts to live meaningfully. Still, the maximally meaningful reality that we should seek would be devoid of evil.

Should We Ask About Meaning?

Questions about meaning and life arise because we are big-brained hominids capable of adopting a detached point of view. We can disengage from life and reflect on it. This ability to reflect is made possible, or at least greatly enhanced, if our basic needs are met—we possess a modicum of wealth, health, and education, don’t fear for our safety, live in a relatively just political order, etc.

Our consciousness of suffering, impermanence, death, and our apparent insignificance in the vastness of space and time especially stimulate questions of meaning. We can’t live long without wondering why life is so hard; we can’t love passionately without asking why we and our loved ones must die; we can’t think deeply without realizing that something about life is amiss. We wonder where it all came from, where it’s all going, and what it’s all about. These questions resonate deeply within us and are hard to silence.

Yet even if we could avoid our deepest questions, we shouldn’t. Our questioning ennobles us and is part of a rich interior life that differentiates us from less conscious beings. We simply don’t fully actualize our powers of thought and reason until we reflect seriously about ourselves and our place in the cosmos. The examined life, all other things being equal, is better than its opposite.

Furthermore, good answers to our deepest questions promote our survival and flourishing, as well as aid our descendants in successfully navigating into the future. Without knowing the purpose of our lives we don’t know where we should go or how we should get there. Without an understanding of life and meaning, we are lost, adrift on our cosmic journey without a compass. But where do we look for understanding? One answer is to religion.

to be continued next week …

October 18, 2018

The Presocratics – The Ionians

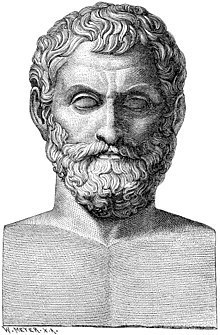

Thales of Miletus “the first philosoher”

Thales of Miletus “the first philosoher”

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

The very first of the Greek thinkers — the Ionians — lived in Asia Minor, in present-day Turkey. They were speculative natural philosophers. Thales, who Aristotle considered the first philosopher, speculated that the various distinct objects of the world all had the same substratum. Underneath the appearance of division in the world, there was a basic material unity: All things were comprised of water. While this is a scientific statement about what comprises reality, it is also a metaphysical statement. It is maintaining a basic unity among diversity.

We do not know precisely why Thales speculated that the common substance of all things was water. Aristotle speculated that it was because water is necessary for all living things. Water could also take the forms of solid (as ice), gas (as steam) and liquid (as water). In any case, what is remarkable about Thales’ view is not really the specific answer that he provides to the question. It is more the approach he initiates to address questions. He is not like the religious poet who comes bearing a message from the gods — his thoughts are not gifts of Hermes. Rather, he is speculating posting natural causes and using natural reason.

What Thales begins, various Ionian philosophers after him continue. Anaximander goes further than Thales, positing views about the origin of the diverse things in the world from a primordial unity. In the beginning was the Apeiron, the boundless or unlimited, a nondifferentiated unity. Out of it, the many things of the world emerge. Decisive here as a break in the explanatory model of the Greek religious-mythical thinkers, the emergence of the world does not occur because of the action of the gods. Neither Zeus nor Prometheus is involved. Rather, it is fundamentally the interaction of two factors — hot and cold — that are at work as the world emerges out of the unlimited. Animals are born from moisture heated by the sun. Humans originate from similar processes — natural and lawlike, even if not so clearly articulated as we might like.

Anaximenes continues reflections on these same issues. He proposes views contrasting with those of both Thales and Anaximander. Not water, he thinks, is the substratum, but air, aether. Following Anaximander, he appears to wonder that if all were comprised of water, how we would account for fire. Yet, in contrast to Anaximander, he posits a clearer mechanism through which the many arise from the original unity. The starting point for the development of the world was not the unbound but was chaos. Out if it, from a primordial breath, the many arise.

One of the main characteristics that we see in these earliest Ionian thinkers is that they do not take the authority of their tradition as a starting point for their reasoning. While they are undoubtedly influenced by that tradition, they set out to reason on the basis of what they experience …

October 14, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Preface

When I consider the brief span of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the little space which I fill, and even can see, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I am ignorant, and which know me not, I am frightened, and am astonished at being here rather than there; for there is no reason why here rather than there, now rather than then.

~ Blaise Pascal

Preface

Wandering around my backyard when I was about 7 years old I climbed a small mound behind our garage when suddenly it hit me: “Why is there anything at all rather than nothing?” That is the first philosophical question I ever remember asking—and what a big question it is. I remained inquisitive throughout childhood, especially about religion and politics, constantly badgering my father for answers to my questions. He did as best he could but eventually I outgrew most of his answers.

In my early teens, I fell briefly under the spell of the New England transcendentalists, the first intellectuals I had ever encountered. Thoreau taught me the value of non-conformity and of hearing “a different drummer,” while Whitman told me to travel my own road in search of truth. His words still resonate within me,

I tramp a perpetual journey, (come listen all!)

My signs are a rain-proof coat, good shoes, and a staff cut from

the woods,

No friend of mine takes his ease in my chair,

I have no chair, no church, no philosophy,

I lead no man to a dinner-table, library, exchange,

But each man and each woman of you I lead upon a knoll,

My left hand hooking you round the waist,

My right hand pointing to landscapes of continents and the public road.

Not I, not any one else can travel that road for you,

You must travel it for yourself.

But what principles should guide my search for truth and meaning? Here Emerson showed me the way with an insight that has informed my journey for more than fifty years,

[Life] offers every mind its choice between truth and repose. Take which you please, — you can never have both. Between these, as a pendulum, man oscillates. He in whom the love of repose predominates will accept the first creed, the first philosophy, the first political party he meets, — most likely his father’s. He gets rest, commodity, and reputation; but he shuts the door of truth. He in whom the love of truth predominates will keep himself aloof from all moorings, and afloat. He will abstain from dogmatism, and recognize all the opposite negations, between which, as walls, his being is swung. He submits to the inconvenience of suspense and imperfect opinion, but he is a candidate for truth, as the other is not, and respects the highest law of his being.

I knew then that an intellectual voyage lay ahead and that I might never anchor. Then, as I was about to enter college, philosophical discussions with a friend further awoken me, as Kant said of encountering Hume, from my dogmatic slumber. It was as if a dam had broken within me, forcing me to see the parochialism of my childhood indoctrination. I now wanted to live and die with as large a mind as possible and I found an irresistible desire to explore the mindscape. In other words, I had fallen in love with philosophy becoming, in Dostoyevsky’s words, “one of those who don’t want millions but an answer to their questions.”

Next, as a college freshman, I eagerly enrolled in “Major Questions in Philosophy,” taught by a newly minted Ph.D. from Harvard, Paul Gomberg. He introduced me to Descartes’ epistemological skepticism, Hume’s demolition of the design argument, and Lenin’s critique of the state. Wow! Knowledge, the gods, and the state all undermined in sixteen weeks. Subsequently, I took the maximum number of philosophy courses allowable in pursuit of my B.A. including: existentialism and phenomenology, Ancient, Medieval, Modern, American, and Asian philosophy, as well as philosophy of religion, science, mind, and law. Holding all these strains of study together was a deep and passionate concern about life’s meaning.

As a graduate student, I focused mostly on the history of western philosophy, theoretical ethics, game theory, and evolutionary philosophy, while teaching my own classes in ethics, Greek philosophy, and the philosophy of human nature. But it was in a series of seminars with Richard Blackwell that my thoughts began to coalesce. In “Concepts of Time,” I learned to think deeply about the mystery of time and began to see change as a fundamental aspect of reality. In “Evolutionary Ethics” and “Evolutionary Epistemology,” I came to understand that knowledge and morality evolve, and in “The Seventeenth Century Scientific Revolution,” I encountered a dramatic example of intellectual evolution.

Then a careful reading of “Aristotle’s Metaphysics” led me to wonder if Aristotle’s view of teleology—that reality strives unconsciously toward ends—could be reconciled with modern evolutionary theory which is decidedly non-teleological. This led to my discovery of Piaget’s conception of evolution where I found the concept of equilibrium, the biological and epistemological analog of the quasi-teleological approach I had been seeking. I now saw how evolution could be characterized as a non-deterministic orthogenesis. Perhaps evolution and progress could be reconciled after all.

So, as a result of six years of graduate study, I had come to believe that evolution was the key to understanding everything from the cell to the cosmos, that the minds and behaviors of human beings are largely explained by biology, that there was some evidence that reality unfolds in a progressive direction, and that the meaning of human life must be found, if it was to be found at all, in cosmic evolution. Naturally, this led me to wonder if the cosmos become increasingly meaningful as it evolves or whether there is any direction to cosmic evolution.

It was also as a graduate student that I first thought about teaching a meaning of life course so as to better ascertain if there was a deep connection between evolutionary philosophy and my existential concerns. Then, shortly after receiving my Ph.D., I got a chance to teach that class, resulting in my becoming conversant in the contemporary philosophical literature surrounding the issue of life’s meaning. However, to my dismay, none of the philosophers I studied were much interested in evolution.

At about the same time I was regularly teaching a class in bioethics. What I found especially interesting there was the potential of genetic engineering to transform human beings infinitely faster than biological evolution could. If technological evolution can transform humanity, I thought, surely that was relevant to questions about meaning in and of human life. So the question of the meaning of life had to be connected with both past and future evolution, especially cultural and technological evolution.

Subsequently, I had the good fortune of teaching a course on the philosophical implications of artificial intelligence and robotics. There I learned to think about the future and human transformation in a new light. We could go well beyond manipulating our genome—changing our wetware if you will—we could potentially become cyborgs, robots, use neural implants, or upload our consciousness into a computer—we could change the hardware on which our consciousness ran. Perhaps we could even be as gods. Now the question of the meaning of life appeared again in a new light. Is meaning of life to become godlike? What would it mean to posthuman?

I subsequently taught the meaning of life class a number of times through the years and in 2012 all these strands of thought came together in my book: The Meaning of Life: Religious, Philosophical, Transhumanist, and Scientific Perspectives. That book mostly summarized the hundreds of books and articles I had read on the subject and was meant to serve as the prerequisite research for having a more informed view on the subject. I wanted to approach the topic of meaning only after having conducted an even more thorough research of the literature.

Now, six years later, with more books read and essays written, and with multiple grandchildren and advancing age, I think it’s time to distill the essence of my own views. (However, I won’t provide their supporting arguments, as those can be found elsewhere in my writings.) Of course, I can never read, write and think enough, as I don’t have unlimited time. But if I don’t do this now I probably never will.

So here I offer my insights and answers on questions of meaning with the following caveats. My thinking is slow, my brain small, my experiences limited, and my life short. At the same time, the universe moves incredibly fast, is inconceivably large, unimaginably mysterious, and incredibly old. We are modified monkeys living on a planet that spins at 1600 km an hour on its axis, hurls around the sun at more than 100,000 km an hour, as part of a solar system that orbits the center of its Milky Way galaxy at about 800,000 kilometers an hour. The Milky Way itself moves through space at more than 2,000,000 km an hour and the galaxies move away from each other faster than the speed of light! (Yes, although nothing can move through space faster than light speed the space between galaxies expands faster than light speed.)

And there’s more. Our galaxy contains more than 100 billion stars and there are more than 100 billion galaxies in the universe. All this in a universe that is almost 100 billion light year across and almost 14 billion years old. And there may be an infinite number of universes! Even weirder, we may be living in a computer simulation. All of this is hardly comprehensible.

Against this immense backdrop of speed and space and time shouldn’t we be humbled by our limitations and apparent insignificance? Who, other than the dishonest or delusional, would claim to know much of ultimate truth? I make no such claim; no one should. My answers are, at best, applicable only to a certain time, place, perspective, and person. Ultimately they are mine alone.

Still, as a species, we are less ignorant than we once were and we share an evolutionary history and a human genome—we are similar as well as different. Perhaps then my conclusions aren’t worthless and may be relevant to others. In this spirit, I offer the following words hoping they provide comfort in what is, at times, a mercilessly cruel world. I also hope there’s some truth in them.

October 11, 2018

The Presocratics

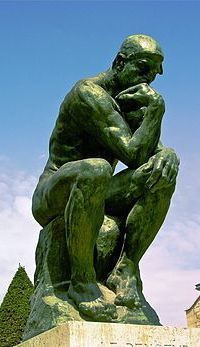

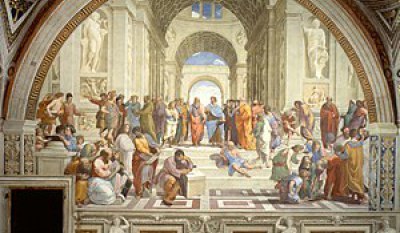

The School of Athens fresco by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael

The School of Athens fresco by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

The earliest Greek philosophers are typically known as “Presocratic” philosophers. Yet this designation as “Presocratic” first was explicitly used in the 18th century as historians of philosophy attempted to re-catalog the discipline’s past. As a temporal reference, the term is a misnomer since some of the “Presocratics” were also Socrates’ contemporaries. As a practical and now well-established classification, however, we might maintain the term to designate a group of Greek thinkers in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE who were intellectually concerned with issues of natural philosophy and/or speculative metaphysics that were of primary relevance prior to the Socratic and Sophist turn toward questions of ethics.

Though much of the thought of these philosophers from Thales (620-546 BCE), who is classically regarded as the first Western philosopher, onwards was focused on questions of the natural world and was proto-scientific, many of the “Presocratics” also challenged the conventional Greek views of the gods and re-conceived of the divine in various ways. They re-conceived the soul. They produced a form of thought that begins to turn against “mythological” explanation. Yet the traditional view that they represent a decisive move from “myth” to “reason” is oversimplified. For one thing, myth itself is infused with reason. For another, some of the earliest thinkers recognized as philosophers used poetry and myth among their devices for reasoning.

It is clear that mythical-religious thinkers — from Egypt to Mesopotamia to Persia and India — prior to the early Greeks had well-developed views about metaphysics, ethics, politics and the other issues of philosophy. They had philosophic perspectives, which did influence the Greeks. Thales and later Pythagoras are known to have lived in Egypt and to have been influenced by Egyptian thought. Plato had some knowledge of Zoroastrianism. Aristotle mentions dualistic ideas of the Persian Magi.

Yet we do see from the 6th century BCE onward the focus on a new kind of reasoning in Greece. It is one more naturalistic in tone than what had been dominant — that is, it does not claim to offer a revelation but to result from natural processes of reasoning. But the philosophy that was emerging was also not only a naturalistic form of reasoning. Science, in some forms independent of philosophy, was being practiced. Many of the Presocratics practiced this, too, but they also did so against the background of metaphysical questions.

Whatever the focus of their individual thought, Presocratics are characterized by the presupposition that reality is rationally structured and that some methodology of rational and/or evidence-based argumentation can be used to settle disputes about the correctness of one’s worldview. Generally, the Presocratics develop a cosmology — a vision of reality as a whole that surpasses the views of science alone.

That said, many of them also did science. Indeed, the Presocratics proposed some broad views about the natural world that we also now accept as true, even if for different reasons than those they proposed. For example, Democritus (460-370 BCE) and other early Atomists argued that all things are comprised of tiny particles known as atoms; and Anaximenes (585-525 BCE) argued that in the course of its history the earth underwent a process of evolution. Though they lacked a full scientific method that since the 17th century has led to the great development of knowledge, the Presocratics created an opening for a scientific naturalistic outlook.

Plato offered one of the earliest cataloguings of early Greek philosophy but as it played into his own system of thought. He contrasted “Heracletians,” who emphasized sense experience and the changes in the world, with “Eleatics” (like Parmenides and Zeno) who focused on the need to bend our views to logic, even if doing challenged the most common sense of our sense experience.

This classification scheme fit with Plato’s own view of himself as the more sophisticated synthesizer of these schools, who in a certain sense completed the project of early Greek philosophy. The world of sense experience, in Plato’s view, is highlighted by the Heracliteans, while the Eleatics prepare the ground for Plato’s own view of the reality of a supersensible realm of unchanging ideas. Truth, in Plato’s view, comes through conceptual reasoning, not through the sense experience. In this, he sees himself as completing the Parmenides’ project. To understand Plato and how he sees himself as responding to the thinkers of his time, this is important.

However, historians of philosophy today understand Plato’s own cataloging as deeply flawed. One recent suggestion for cataloging this early thought is topical as relating to (a) the study of nature related to cosmological order, (b) “cultural polemics”, (c) considerations of the soul, and (d) processes of reasoning. We see this group of thinkers take up these issues, some devoted with greater focus to one, some to another.

October 8, 2018

Belief and Knowledge

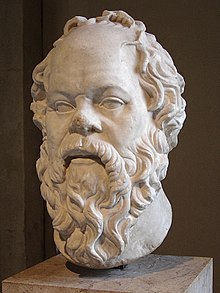

A marble head of Socrates in the Louvre

A marble head of Socrates in the Louvre

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/02/...

Socrates famously noted that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” But what exactly does an examined life require? …

Our starting point

We do all start our process of self-reflection with our inherited perspectives. We are born into a particular family and society and acquire our first views from such contexts — influenced strongly by our parents, our schools, the religious, civic and political authorities. There are always background assumptions in such contexts. One thing philosophers try to do is bring those background assumptions to light and examine them. Philosophers do so with the intention of clarifying concepts, providing a justification for beliefs and considering whether our priorities are well-ordered.

Some basic questions on belief and knowledge

As we consider an examined life, I want briefly to reflect on a few basic concepts of importance for this examination. First, what is a belief? For beliefs are largely what we will examine. Second, how do beliefs relate to knowledge? For true beliefs have been the traditional goal of philosophers. Third, what is a warranted belief? For while the traditional philosophical goal of certain and absolute truth largely evades us, I would like to suggest that this more moderate goal [of having warranted beliefs,] … may replace it [the goal of absolute truth or knowledge.]

A belief

A belief is a subjectively held view. We think that our beliefs are true, but some of them are and some of them are not. Beliefs, as we have discussed, are first of all a product of our social environment. We acquire beliefs, among other things, from our “knowledge communities.” In our society, we have established schools where knowledge from diverse academic disciplines is passed on: There we learn that 1+1+2. We learn that atoms (or subatomic particles) are fundamental building blocks. We learn that organisms are comprised of cells. We learn that organisms evolve through history. From our households, churches, and political system, we learn certain views of about morality and/or law are correct. We learn that certain religious views are or are not correct. In all of this, we learn how to learn. That is, we are taught by our communities fundamental approaches to knowledge questions that are deemed respectable.

Relative degrees of certainty and appropriate forms of justification

When I say “we learn” here what I really mean is that we are taught these things and we come to believe them. For some of the things I’ve mentioned are thought to be knowledge and quite certain and others less so. We are taught — though we may not be conscious of this — that different standards of evidence are required for different domains. Aristotle already differentiated between areas, like physics in which we could have considerable certainty, and other areas, like ethics, where we have much less certainty.

Dogmatism

Sometimes we are taught that no evidence is needed for some beliefs, but that we should just dogmatically embrace a set of ideas. This form of dogmatism is decidedly unphilosophic. Philosophy is characterized by seeking justifications for all beliefs.

When it comes to religious beliefs, no small children and few young adults have views that were not taught to them by their parents or guardians, or someone with whom they had a lot of contact as children. Most of those in the United States are Christians, born into Christian households. Yet it is clear that if they had been born in India, of Hindu parents, they would likely be Hindu. Some students, now adults, have examined beliefs they grew up with and have moved away from the religion of their parents. Some have examined them and retained the religion of their parents. Some haven’t thought about their religious views much. People are often not willing to compromise on religious beliefs. Some people do hold religious ideas non-dogmatically, though, viewing them as basic principles that are open to some revision.

Though religious beliefs are among the beliefs held most dogmatically, they are not the only beliefs that are held dogmatically. Some political beliefs or basic moral positions are held without much justification ever provided. In the United States, many people think that the country is the best, most free country in the world, or in world history. Regardless of whether it is true, few people attempt to justify the belief in any detail. Those who do clearly don’t do so by pointing to the wellness indexes of the UN such as average life expectancy, the average educational level, the results of average happiness studies. None of those indicate that life in the U.S. is superior to that in other countries. They also rarely make use of in-depth cross-country or cross-historical arguments. Doing so would require specifying clearly what the criteria for greatness are.

This political view, like a religious view, is normally held dogmatically. Reflecting on the view can teach us something, but there is often a hesitancy to reflect on it, because to do so may be viewed as unpatriotic, or it will simply go against the cultural grain, and we are uncomfortable to take a minority stance. Identity issues are tied up with some of our basic beliefs about religion and politics. This makes movement on those issues particularly cumbersome.

Knowledge beyond certainty

As mentioned, philosophers have long indicated that different domains allow different levels of certainty and different criteria for justification. Contemporary philosophy has long moved beyond searching for absolute certainty for most of our beliefs. Instead, philosophers, like the pragmatists, have developed views that while it is important to seek justifications for beliefs, we need not have justifications that are always airtight. Indeed, we cannot.

Yet that does not mean that any belief is just as a justifiable as any other. John Dewey, an American pragmatist of the early 20th century, argued that we should look for “warranted assertability.” For this, we need to consider what kind of evidence applies to the domain under question and try to figure out what the right amount of evidence for that domain is. This, of course, is a difficult task. But as thoughtful and serious people, it is a task that we cannot avoid. To do so would essentially to affirm a willed ignorance about various domains about which rational reflection and the use of evidence-based reasoning could help us to develop some reasonable beliefs.

Knowledge is generally thought of as a kind of true belief. But of course, we could have a true belief serendipitously. We might have been taught something true and believe it even though we do not know why we believe it. In alignment with the philosophical desire to understand the world and to understand the reasons for beliefs and to form beliefs responsibly, it is perhaps more appropriate to view (theoretical) knowledge as consciously justified true belief. But this description too might only work as a guide rather than as a hard and fast definition, since much-purported knowledge cannot be known to be absolutely true.

One of the values of philosophical reflection is that it can help us to gain greater clarity about appropriate forms of evidence for beliefs and to grasp why we might hold something to be true (and even provisionally call it the best knowledge available), given the state of evidence that we have, without clamoring to the view as dogma.

Fallibilism and abduction

Twentieth-century philosophers from John Dewey and Charles Pierce to Karl Popper have emphasized the wisdom of revising our beliefs in light of new evidence that we find. Pierce develops a position known as fallibilism that is also later developed by Popper. Pierce’s view is that knowledge grows as we formulate positions and develop beliefs that are open to being disproven or improved upon and that we revise those views in light of knowledge we gain. Pierce’s article The Fixation of Belief highlights the value and wisdom of such an approach, which, in stark contrast to dogmatism, is open to correction.

The lack of certainty that we have in various domains thus does not condemn us to absolute relativism — the view that any view is as good as any other. But because our accepted beliefs are not shown to be absolutely certain, but only the best available ones given the available evidence, we might speak of “truth” with a small “t” rather than a capital “T.” This attitude expresses humility — an acknowledgment of the difficulty of the questions being posed.

Pierce thinks that at least when it comes to scientific views, the evidence is always strong enough to point to the best answer. He calls the reasoning to this best explanation abduction. Various theorists apply this term to domains outside of science. There is some debate among philosophers of science about whether it is even possible in the domain of science. There is even more debate about whether it is possible in other domains. Is there a best single answer applicable to all people to all questions of applied ethics or to all questions of the spiritual or religious life?

Philosophical reflection facilitating self-knowledge

If there is not one best answer to all of the kinds of questions philosophers ask, we could ask what value there is to asking those kinds of questions at all. Might we return to Socrates’ dictum at this point? Might it be valuable for providing us with the possibility to know our own minds, to gain greater clarity about what our own values are — in short, for facilitating self-knowledge that can improve our lives?

Even if in some domains (like religion or ethics) do not in every case provide us with universally acceptable answers, or clearly best answers, might there be a value in reflecting on what some of the reasonable answers are? We will likely at least learn what some really bad answers are. And might the reflection at least facilitate us in better deciding the things that we, individually, find worthy to care about and the beliefs we find worthy to pass on?

Useful links

See my short discussion of Fallablism or see

Fallabilism (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) or see

Belief (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

October 4, 2018

PBS Frontline “Trump’s Showdown”

[image error]

Last night I watched the new PBS Frontline “Trump’s Showdown.” It was the sixth film in this anthology from Frontline” filmmaker Michael Kirk. Other films include Trump’s strategy for wresting power from the Republican establishment (“Divided States of America“) and muscling his way into the Oval Office (“Trump’s Takeover”), to what his surrogate represents (“Bannon’s War”) to our susceptibility to Russian influence (“Putin’s Revenge”), and more.

It is difficult to verbalize how well-researched and powerful the 2-hour documentary is. If watching this series were a prerequisite to voting in this country Trump couldn’t possibly have been elected. I doubt that any reasonably intelligent, impartial person could watch it and still be a Trump supporter. Unfortunately, there are many misinformed and/or bad people in the country. I encourage my readers to take a look.

In the meantime let’s hope for the success of the many forces allied against this attempted coup by Trump and his Republican sycophants. We should remember that civilization is a high achievement that is founded on the rule of law, as Aristotle noted long ago, and that it rests on very shaky foundations. It doesn’t take much for warlike words to turn in to warlike action. We tread a path that may lead to a dissolution of the social order. And if we ever get there we will regret our lack of self-control.

For a more in-depth discussion of the documentary see: “Decoding Trump’s “Showdown” strategy, from Roy Cohn to Michael Cohen” in Salon.

_______________________________________________________________________

(Note – The political situation in the USA is so depressing that I’m not going to write about it for a while. Over the next few weeks I’ll return to philosophical topics. )

September 30, 2018

Kavanaugh is Obviously Guilty of Sexual Assault

Tarquin and Lucretia by Titian

Tarquin and Lucretia by Titian

I hesitate to comment on the current spectacle surrounding the nomination of Bret Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court since my words are unlikely to sway anyone’s mind. Still, let me state how a non-partisan juror or good critical thinker might consider the problem.

Point 1 – Your intuition about who is or isn’t lying is worthless. It has been well-demonstrated that humans are very bad at detecting lying. Instead, they simply superimpose what they want to believe or disbelieve onto whoever they are listening to. So don’t tell me someone seems credible or not. Your intuition here is worthless.

Point 2 – Dr. Ford has little incentive to lie and had a lot of incentive to remain quiet. Mr. Kavanaugh has every incentive to lie.

Point 3 – There is a lot of circumstantial evidence against Kavanaugh. People who knew him as a teenager say he was a frequent drunk; his friend and fellow alleged assaulter Mark Judge wrote a book Wasted: Tales of a Genx Drunk[image error] (which is now almost impossible to buy); there are other allegations of sexual assault against Kavanaugh; etc. (A Yale classmate has also accused him of being a drunk.)

Point 4 – Kavanaugh is a liar. He gave misleading testimony about his knowledge of stolen documents when he was in the Bush White House and about his involvement in judicial nominations. In addition when asked about his yearbook claim to be a “Renate Alumnius,” he pretended that there was no sexual insinuation. This was almost certainly a lie. He also lied by saying that it was legal for him to drink as a high school senior. He was then 17 and in his state the drinking age was 21. And he lied about having no connections to Yale when he was a legacy student. And he lied when he said that references in his yearbook were about a drinking game and flatulence when they were almost certainly about anal sex and sex between two men and one woman. And he lied …

Point 5 – False accusations of sexual assault and/or rape are the exception, not the rule. This is well-established in the scientific literature. The bottom line is that false allegations are probably somewhere between 2% and 10%. For more see:

a) Wikipedia – False accusations of rape

b) National Sexual Violence Resource Center – False Reporting

c) Stanford University – Myths About False Accusations

Based on this fact alone Kavanaugh is very likely guilty.

Conclusion

If I were a betting man I’d say the chances he assaulted Dr. Ford are about 100 to 1. It’s possible he’s innocent but very unlikely. This may or may not disqualify him from a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court, but the fact that he is probably a liar should.

Finally, Kavanaugh wants our sympathy for bad deeds committed as a teenager—which he may deserve—but you can bet he won’t show any mercy to non-white teenagers who plead before him in his court. At them, he will throw the full weight of the law.

Poor Kavanaugh. If denied this seat he will likely go back to sitting on the nation’s highest appeals court or accept a multimillion-dollar salary as a partner in a law firm. Like most entitled rich, white frat boys the law doesn’t apply to him—he only wants to apply it to the rest of us.

Finally, for a persuasive case against Kavanaugh by a conservative, see Jennifer Rubin’s great piece in today’s Washington Post “If we want to protect the Supreme Court’s legitimacy, Kavanaugh should not be on it.”

For more see also:

“Kavanaugh is Lying: His Upbringing Explains Why”

“Here’s Where Kavanaugh’s Sworn Testimony Was Misleading or Wrong”

“At times Kavanaugh’s Defense Misleads or Veers Off Point”