John G. Messerly's Blog, page 62

April 8, 2019

Review of: A Thinker’s Guide to Living Well

I have given away almost my entire collection of philosophy books, which at one time numbered more than a thousand. I have kept maybe 75 books, mostly ones that I had written or had been gifted to me with inscriptions, or that had special meaning to me.

Surprisingly one that I still possess is a book I reviewed for a professional journal more than 25 years ago—the first such review I had ever done. That book was titled, A Thinker’s Guide to Living Well[image error] by Dennis Bradford. The review, which appeared in The Modern Schoolman, LXX, January 1993, I reprint here with minor editing.

Dennis E. Bradford’s book provides a plan for living well. “Providing a good plan that works is what this book is all about.” (p. 3) He recognizes that others have attempted this—Confucius, Socrates, Aristotle, and Ben Franklin among others—but he wants to show how this can be done in “present-day North America.” (p. 3) The author claims that a good life is one of health, wealth, and wisdom. Wisdom is especially concerned with living well, but although you can have wisdom without health or wealth, it is better to have all three, “just ask anyone who is either unhealthy or poor.” ( p. 4) He also claims by being informed by modern medical science and technology, his plan has advantages over previous attempts to describe the good life.

The author has some informative things to say about health. He emphasizes how important health is to the good life, (not a sufficient but a necessary condition) and the importance of things like choosing a qualified physician, have regular physical exams, receiving appropriate vaccination, keeping up with health care developments, a practicing preventative medicine, and learning basic first aid techniques. While such advice may seem mundane, it is important nonetheless.

Habits are the next topic. Good habits increase the chance of success in one’s project–defined as one’s most important activity—and bad habits decrease this chance. In Chapter 3 he focuses on eliminating bad health habits, particularly smoking. “Your smoking habit began voluntarily and can be stopped voluntarily.” (p.39) And, it turns out, Bradford is a former smoker himself. “Think of curing dried leaves off a bush, shredding and blending them rolling them into a piece of thin paper, lighting one end, and sucking the resulting smoke into your lungs. The whole sequence is preposterous.” ( p.44)

Chapters 4 & 5 focus on creating good health habits. These habits aren’t identified as those leading to pleasure and besides “it is false that pleasure is the only abstract good.” (p. 52) Eating, for instance, may be pleasurable but is purpose is to contribute to one’s health. Bradford offers some suggestions about a healthy diet but defers to nutritional experts for specific advice? As for exercise, he recommends walking for beginners and he provides a detailed explanation for a gradual training program.

The author considers knowledge to be intrinsically valuable, and he advises getting as much education as possible. Bradford also argues that work is intrinsically valuable. Unfortunately, many people don’t have the opportunity to engage in satisfying work because of social and economic conditions. But as this is not a treatise in political philosophy, the issue is not explored. He does recommend that individuals pursue formal education and strive for financial independence. But he reminds his readers, that financial independence is a means to an end. To live well and engage in one’s most important project is the end and financial independence is the means to that end. Benjamin Franklin exemplified this approach. His business success provided him the means to pursue his project—scientific activities. Still, “Financial independence is not the meaning of life.”

( p. 179) The question now becomes, “What is?”

The last chapter, entitled “The Meaning of Life,” probes this question. Bradford argues that “Nothing done by any human … will have any permanent significance.” ( p. 184) He doesn’t believe that we have any cosmic significance and that the burden of proof rests with those who suppose we do. Those who believe that we have a special cosmic significance should present evidence. “Where is that evidence? I know of none.” ( p. 185) But our cosmic insignificance implies that we can do with our lives what we want. We can give them meaning and significance through our projects. And what do worthwhile project entail? He argues they must be: 1)capable of withstanding rational scrutiny, 2) directed toward a valuable end; 3) moderately challenging; and 4) a source of lasting satisfaction. He offers two examples of such a project—a life of service exemplified by someone who helps house the homeless, and a life of inquiry exemplified by a medical researcher.

Is there any way to decide which life is most valuable or which one should we choose? Such questions lead to considerations of the relationship between facts and values. The author believes that the “value-facts” exist but are difficult to determine.” ( p. 208) Value-facts derive from a consideration of human nature. Because of our nature, health, knowledge, friendship, wealth and wisdom are all intrinsically valuable.

Bradford’s book echoes much of Aristotle’s writing on the good life. As such he fills in a lot of details that Aristotle could not. And he concludes by stating that he wrote the book “for the satisfaction of communicating something useful to other passably intelligent people.” I believe he has succeeded.

April 1, 2019

Socrates: The Trail And Death

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/25/...

Socrates is philosophy’s most famous martyr. Yet he wasn’t the first tried in the courts of Athens. The Decree of Diopeithes allowed for the persecution of “those who fail to respect (nomizein) things divine or teach theories about the heavens” (OCD). It had been used against Anaxagoras, who challenged traditional views of gods and taught the heavens were merely burning stones. There is also evidence that Diogones of Apollonia was accused (Laks, 7). Numerous other thinkers and statesmen were also sentenced to death for various reasons around this time: Sophocles is only the most famous of others to be executed for impiety (Johnson, 152)

The rigid legal system was a sign of the crisis in religious and moral traditions at the time, and of the fear of those governing. The legitimation of morality in Athens, like the legitimacy of religion, was viewed as under threat. The Presocratics along with the Sophists — and some other thinkers — were seen as a threat to the civil order. Here religion was not a private affair. There was a civil obligation to participate in religious rites. It would have been widely accepted that the gods may punish the city for the impiety of its members. There would have been a strong desire among many to prevent the teaching of new ideas about the gods and to halt any questioning of traditional ethics. New teachers of all sorts were suspect.

Socrates and Xenophon both make strains to distinguish Socrates from the Sophists and the Presocratics, the philosophers of nature like Anaxagoras, who Pericles had invited to Athens. This is writ large in The Apology and Plato’s general narrative about Socrates. Aristophanes’ The Clouds, however, told a different story, one that would have been familiar to many at Socrates’ trial. Aristophanes’ work might be read as an early medial attack on a leading public figure. It set up Socrates, apparently very unjustly, for a fall. We can imagine that it also influenced Plato’s later developed view of the potentially negative role art could play in a polis.

The alleged impiety of non-traditional thinkers like Socrates was of grave concern to many in Athens. Add to this the fact that Socrates had attracted to him members of the Thirty Tyrants who were had early staged a bloody coup of the Athenian government and harbored some of the strongest critics of the Athenian Democracy. Critias, his former student and the cousin to Plato’s mother, had led the group. Charmides, a close associate, was Plato’s uncle (Johnson 145ff.). Socrates had also, no doubt, regularly embarrassed many of the leading figures of the city and not unlikely some on his jury or well-connected to jury members. The Athenian democracy, too, was a purely majoritarian political order, entailing all of the possible threats of a mobocracy. Spurred on by the fate of Socrates, Plato will later offer one of the most influential attacks on democracy in history, precisely as facilitating mob rule and rule by the least fit.

The jury, according to The Apology, consisted of 500 citizens of Athens. In the trial, Socrates displays his typical irony. Specifically of importance for the case of denying the existence of the gods, Socrates relates how his entire philosophical quest (which is resulting in his now being tried) began only after his friend Chaerephon had been told by the priestess of the Oracle at Delphi of the judgment of the Oracle that none was wiser than Socrates. The irony here, of course, is that the Oracle is deeply significant for the religious. Do the religious really want to condemn one who their own most famous oracle has said was unmatched in his wisdom?

There would, of course, have been various ways to understand the Oracle. One might have understood it to mean that no man is wise at all — along the lines of Heraclitus’ fragment that “a man is found foolish by a god…” (D 79). So Socrates’ wisdom like that of all other men would be negligible. Socrates, however, does interpret the Oracle rather more commonly as implying that he does possess a kind of wisdom. Interestingly, though, Socrates does not simply accept the statement of the Oracle on faith. He trusts his own reasoning, not the declaration of a religious authority. So he sets out apparently thinking it may be possible to show the Oracle wrong. Socrates surely has a different piety than most Athenians. His has underlined the importance of trusting his own reasoning, not that of authorities. Yet he does come to see the truth of the Oracle. As earlier discussed, he sees a form of wisdom in his understanding of the limits of his own knowledge.

The story of the Oracle, of course, provide Socrates with the possibility of describing how he came to be a public philosopher. Yet, since this is the major Oracle of religious importance, the story serves as a sort of witness of character — for those willing to believe, from the gods. Much of what Socrates offers in the court scene similarly witnesses to his character. He recounts his service in the Peloponnesian War. He distances himself from the natural philosophers who had otherwise been tried in Athens, noting that as a young man he had already turned his back on their speculations having found them bereft of evidence and also unimportant since the teaching would not improve the soul of man. Similarly, he distances himself from other new atheists, the sophists, who are known to teach for profit. The former group may teach heresy about the gods. The latter were in many cases more vehement about their atheism, not redefining the gods anew, and they were thought to corrupt the youth. Socrates shows he has a kind of piety.

By contrast with the sophists — he maintains — he fundamentally cares about the soul. Further, he claims not really teach at all. He just spurs his interlocutors on to self-reflection in conversations. In his plea, Socrates reveals that he is not like Heraclitus, who condemned the religious rites as having a corrupting influence on those who practiced them. Socrates may have unorthodox views about the gods, but he still participates respectfully in the civic religious ceremonies. More still, Socrates, even is led in his decisions, always consulting with the voice of a daemon, which speaks to his conscience, not bidding him positive things to do but warning him when he should avoid some negative course of action. Though his defense does show that he is far from Orthodox, it also does show Socrates to be a deeply spiritual man.

Is he an atheist? It is clear that he does not believe in the gods of Hesiod. Does he corrupt the young? He does for those who think that teaching non-traditional ideas about the gods and about morality is corrupt. Socrates, however, makes his case denying atheism and maintaining that he did not take money for teaching like the sophists, who it is implied might really be considered too corrupt the young. And in any case, he underlines he would only encourage the young to use their minds, to care for their souls, that which is best in them.

In the end, the 500 votes were cast. It was a close decision, as Socrates was found guilty by fewer than 30 votes. But guilty he was found. It thus came to him to propose a penalty. Now, though, in a display of Socratic irony, even at this point Socrates refuses to placate his jurors. As a proposed punishment, rather than suggesting a reasonable fine or exile — something customary that may well have swayed enough jurors in his favor — as punishment, he suggests free meals at the Prytaneum for life, the reward for Olympian heroes. Would not Socrates deserve at least as much since he cared for what is most important in man — not the body but the soul? This was clearly in jest. But large numbers in the jury, we can well imagine, would have been less than amused. He then notes that he has but one mena, an amount that would buy a copy of Hesiod — so again, an insult. So he finally suggests that his friends would come up with thirty menas (Johnson, 167), about 1/5 of his annual income. This was not insignificant but was still not a serious amount of money as an alternative to a death penalty. At the jury reconvening, in a larger number than the initial vote, they sentence Socrates — to death by the drinking of hemlock (Johnson 151ff.).

Socrates in prison

Ordinarily, Socrates would have been executed the day after the trial. But because of a religious ceremony over three days, the execution had to be postponed. The prison reflections that occur (or that Plato places) in this period in Crito and Phaedo provide Socrates (or Plato) an opportunity to reflect on the trial, of his views of his obligations to the state and on his views of death. They show Socrates content with his decisions in the trial and willing to face death, even if it is unjust.

Crito, who the dialogue is named after, depicts conversations between Socrates and his friend in his final days. In the dialogue, Crito offers arguments critical of Socrates’ behavior in the trial and reasons for Socrates to allow his friends to pay a bribe so that Socrates can flee prison. Socrates in each case offers counter-arguments that Crito appears to find convincing. A first argument concerns why Socrates was so disregarding of the mores during the trial. Surely, Socrates would have had a better chance with his case had he simply been respectful of those trying him. To this Socrates indicates that he does not believe that respect in such arguments is due to those in power, but to those who have truth on their side. “One should greatly value some opinions,” Socrates notes, “and not others.” Besides he argues, “A good life is more important than a long life.” Socrates is unrepentant. Crito is an obedient interlocutor.

Seeing that Socrates is in such a difficult situation and that Crito and his other friends can help, Crito suggests though that Socrates allow them to pay a bribe for his escape. This would have occurred often enough in the situation. Crito drives home particularly that this would be justified since the sentence was wrong, and indeed Socrates death would bring about a further wrong of depriving his wife and their children of his care. Socrates rejects this utilitarian argument about the greater of evils. He adheres to a strict ethics of duty. Even though the sentence was wrong, paying a bribe is wrong as well; and two wrongs do not make a right.

A tacit contract — and a basis for civil disobedience

Finally, Socrates argues that besides the fact that bribery is wrong, he thinks that has a duty to the city-state of Athens to accept the punishment of its legal system, even if that penalty is unjust. Here Socrates puts forward an argument that will be important in the history of philosophy that individuals living in a polity form a tacit contract with the political body from which they benefit. In Socrates’ case, he has benefited from his education in Athens and from the security of the city-state. So while he has a fundamental obligation to follow his conscience on matters of individual action, he also has an obligation to accept the punishment for that if the city-state metes it out.

Socrates implied throughout the court case that he has an obligation to follow a higher law than that of the city. He must follow his conscience in matters of personal action. Here, however, he displays a paradox, like later proponents of civil disobedience. While maintaining the duty to breach a particular law (here to question traditional views even if it is not permitted), he still affirms a basic duty to the system of law. He must accept the punishment the city-state provides for breaching that particular law.

The entire point is not so clearly laid out as it is displayed. Though these fundamental principles of what will become civil disobedience are not all clearly synthesized in a treatise, the basis for the argument is clearly to be reconstructed from the text.

There are some further elements in a teaching of civil disobedience as later developed missing here. In John Rawls 20th century theoretical formulation of the ideas, it is important that the breaches of the law be done with the purpose of pointing out the failure in the legal system to those in power so that they reform it. In most cases, civil disobedience later occurs not with individual actors, who would likely be ineffectual, but as part of a social movement.

Nonetheless, whatever differences there are between civil disobedience as a developed teaching and Socrates’ depicted actions in the trial and death scenes, there are some remarkable similarities. In the ideas depicted in these final scenes of Socrates life, we thus see two vital ideas for the later history of thought: the idea that there is a tacit contract between an individual and her polity; and the kernel of the often related teaching on civil disobedience.

On death and the soul

Phaedo is thought to be a middle-period work of Plato. In it, Plato develops ideas on the immortality of the soul that many scholars think differ from Socrates’ own views. In part, this is because they show a tension with other views that are expressed on the soul by Socrates in the Apology. In that dialogue, contemplating death Socrates assures his friends that there is no need to fear, for it is one of two things. Either it is a night of dreamless sleep, which should cause none to worry, or it is as the poets claim, which is a reason to be cheerful. Socrates expresses a hope that it is the latter, but without a worry if it is not.

In Phaedo more Platonic views of the soul are introduced. In that dialogue, Socrates wife, Xanthippe and his child were sitting with Socrates when his friends entered to speak to him. They are led away after the arrival of his friends. In the ensuing scenes, the character Socrates is together with Crito, Cebes, Simmias, and Phaedo discussing many (of Plato’s) ideas about the soul.

One of the remarkable elements of Socrates’ death scenes is the great serenity with which he is shown to confront death. He is 70 at the time of his execution. He exudes a sense that he has lived a life of good conscience and he can die in peace. After a long discussion, Socrates finally summons the guard for the hemlock. He drinks it and settles down to die. Of those present, Socrates alone remains calm. He eventually lies down and covers himself. The parting words of the philosopher were a request to settle debts: “He was beginning to grow cold about the groin, when he uncovered his face, for he had covered himself up, and said—they were his last words—he said: Crito, I owe a cock to Asclepius; will you remember to pay the debt? The debt shall be paid, said Crito.”

March 25, 2019

Random Musings

I recently finished a series of posts summarizing a lifetime of thinking on the meaning of life (they begin here if you’re interested.) Since then I have been using my blogs to let a number of regular readers submit essentially guest posts. I very much appreciate their contributions and will feature more of them in the coming months.

What then have I been doing? Mostly 1) playing golf, 2) taking care of my grandchildren, 3) learning, and 4) keeping up with world events. The first three I find rewarding, the last one extraordinarily depressing.

I play golf mostly for the 6-mile walk, the enjoyment of nature, and the camaraderie with friends. Walking the course also elicits fond memories of playing with my father when I was young and of the many times when the solitude of walking alone on a course brought inner peace in troubled times. Walking in nature I find a haven from a troubled world. My own unique monastery.

Playing with my grandchildren brings out my inner child, a kind of playfulness that we lose as we mature. So it too provides an escape from troubles of the world. Yet the innocence of children evokes a sweet sorrow in me. It is beautiful and yet it makes you want to cry thinking of all the evil of which they’re ignorant and which they’ll confront. How can life begin like this and end up so differently?

Learning is intrinsically rewarding. To contemplate reality lifts the mind beyond itself, to a type of union between the mind and the universe which is one of the highest goods we can achieve. We truly transcend the world in thought, going beyond what is to what could be. Thus we can momentarily forget the world’s troubles through contemplation, just as we do when meditating, listening to music, enjoying nature, etc.

Yet while playing and loving and learning life our hearts, the world is always there to bring us back down. We live in a country where elected members of a major political party willingly destroy democratic government and chance further descent into violence and chaos … simply to be reelected. And what do they then do? Simply accept and affirm the abuses of authoritarian fascists. All around the world, human avarice continues to destroy the earth and climate on which our survival and flourishing depend, which is to say nothing of the pain, poverty, slavery, and violence that constitutes so much of life. Humans, myself included, are such flawed monkeys.

Still, any regular reader knows that at this point I’ll turn to hope. Perhaps the future will be better than the past; maybe we can lift ourselves up from our primate roots, outgrow our medieval institutions and make something of ourselves and the world. I do hope so.

In the meantime, I’ll try to enjoy walking and playing and learning. When I move my body, play with my grandchildren and exercise my mind, it is then I find peace—experiencing perhaps, a small taste of what life might someday be.

As Bertrand Russell put it in his final manuscript:

Consider for a moment what our planet is and what it might be. At present, for most, there is toil and hunger, constant danger, more hatred than love. There could be a happy world, where co-operation was more in evidence than competition, and monotonous work is done by machines, where what is lovely in nature is not destroyed to make room for hideous machines whose sole business is to kill, and where to promote joy is more respected than to produce mountains of corpses. Do not say this is impossible: it is not. It waits only for men to desire it more than the infliction of torture.

There is an artist imprisoned in each one of us. Let him loose to spread joy everywhere.

March 18, 2019

Summary of Socrates’ Teachings

A marble head of Socrates in the Louvre

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Excerpt reprinted with permission.)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/21/...

Socrates’ biography

Socrates was of humble roots. In Nietzsche’s eyes: He was born of the rabble. His father was a stonemason, his mother was a midwife. As a young man, he is thought to have studied Greek natural philosophy. But he found the views of the natural philosophers too obscure and unsubstantiated. He thus, like the sophists, turned against natural philosophy to questions of morality and justice.

In Athens, he lived a life of simple means, married Xanthippe, with whom he had three children. He fought, evidently heroically, in the Peloponnesian war against Sparta. He was known in Athens for gathering and speaking in the Agora, the market place. He was known as unkempt, often unwashed, and for being quite homely … Yet many were attracted to him. He … gathered support from some Athenians who had been members and associates of the Thirty Tyrants, who had early led a bloody coup against the government in Athens and who were bitterly opposed to its democratic government.

According to Plato’s account, he … was motivated to his public discourse by an early Oracle of Delphi, which had indicated that no one in Greece was wiser than Socrates. In what we may take to be an ironic court defense, he maintains that he found this unbelievable so set out questioning the learned in Athens to find someone wiser than himself. In Plato’s account, Socrates’ questioning was unsettling to authorities in Athens, who thought that he was undermining the civic religion of Athens and corrupting the youth. Socrates was thus brought to court, where he was found guilty and sentenced to death. Socrates’ thus became a celebrated martyr for philosophy.

The examined life

Among the views for which Socrates is most famous is that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” The ability to think, in Socrates’s view, is our unique human capacity. To live a life devoid of thinking — where we simply accepted what tradition and authority told us — was thus to live a less than fully human life. But what does an examined life, the fully human life, entail? For Socrates, it entailed questioning especially the moral and religious views of his tradition. In Socrates’ view, this examination is to be done as a form of moral or spiritual development — it is done with the intention of moral improvement both to oneself and ultimately to one’s community.

While it was traditionally thought that the existing laws of a polis were identified with the will of the gods, Socrates questions this. There were hints already in Heraclitus and others of a view like this — that there is another law a law above the city’s laws to which one had a greater alliance. Socrates’ life and death is a testimony to a belief in such a law and to a sensibility that adherence to that other law is imperative.

The clarification of concepts

Socrates is invested in the clarification of concepts, even if he does not always finish the job (or hardly ever does) and provides us with a clearly satisfying definition or description, even if often we need to look to what he does — as a character in Plato’s dialogues — if we want to answer some of the questions he poses.

Socrates engaged in his own self-examination with the clear conviction that he could come to understand truth, and that the means to do so was through the clarification of concepts, achieved not through individual self-reflection but through dialogue. This indeed is so marked in him that Aristotle thought it fundamental to the shift in ancient philosophy from the Presocratics to a new era in Greek thought. We see hints of it in thinkers previous to Socrates who are thinking of metaphysics — Parmenides being the main case in point. But it becomes full-blown and receives a new focus on questions of justice in Socrates. What is justice? What is piety? As individuals, living in a society, we have internalized views about what these things are. [But] Socrates thinks that self-examination involves us in a process of thinking through our own beliefs on these questions …

The Socratic method

Socrates maintained that he did not teach anyone. What he did was facilitate their own self-reflection through public dialogues. The disputational method Socrates used in the public forum led to his reputation as a gadfly, for his logic was often stinging. Taking some proposed general definition to a question like what is justice, he was merciless in criticizing its weaknesses, often indirectly and with irony. And he did not hesitate to embarrass the most recognized of the citizens of Athens.

This dialogical approach, [today] described as the Socratic method, was used not to propose his own views. Socrates was not a guru who answered the most obscure of metaphysical questions and sought adherents to the system he constructs. Rather his method was to engage in an exploration and to get those involved to reflect on their own views, on the culturally accepted views they had largely adopted. It focused on clarifying what the concepts under discussion meant, what presuppositions they entailed. It typically started with a definition of a concept, which would then be analyzed, broke into discrete parts; then on the basis of the analysis, the ideas were synthesized.

In his public dialogues, Socrates appears to be motivated by a faith that the analysis of concepts should lead to positive results. Yet curiously perhaps, Socrates did not develop a set of clear ideas about what justice is, what piety is or the other things that he discussed so enthusiastically. He deconstructs much more than he constructs.

Socratic wisdom

Indeed, this [is] even fundamental to what becomes known as Socratic wisdom. In Plato’s rendering of Socrates’ story in The Apology, when … Oracle of Delphi [told Socrates] … that none was wiser than him, Socrates [was] skeptically. He claims it inspired him to begin to discuss ideas in public. Not feeling wise at all, he was sure — he says with some irony — there must have been others wiser than himself. In the court case where he discusses this, he notes however that after years of such questioning and public conversation he did come to recognize that there was some truth to the Oracle. He had a kind of wisdom. His wisdom, which others lacked, was simply in knowing the limitations of his own knowledge. Socrates’s wisdom consisted in knowledge of his own ignorance.

It is an interesting paradox perhaps that one of the individuals most celebrated for his wisdom in world history in fact baldly claimed that this wisdom consisted in so little. The fact is that those who have viewed Socrates as wise have never really taken this explicit statement of what his wisdom was to be the complete story. Socrates was trying to clarify concepts, but as a statement even of what his own wisdom was, this is quite incomplete — a negative definition only.

If that is all there were to Socratic wisdom, then we might have imagined this serving as a footnote in Ancient philosophy. But of course, much of what we have taken to be Socratic wisdom has consisted not in what was said, but in what was unsaid. It comes from an examination of how Socrates lived his life. And here there is much more indeed than is summarized in the negative description of wisdom.

Is his statement that he is wise because he recognizes what he does not know simply a case of irony? Is it likely not offered as a definition at all? In any case, if we want to know what Socrates wisdom consists in then an examination of his life offers us something much richer to work with than his negative definition. In his life, … Socrates is someone deeply curious, conscientious about self-examination, which he engaged in as a practice of self-improvement. Socrates is wise because of his care for the soul, because of his questioning whether his own priorities in life were rightly ordered and whether his own life was just and good … when it comes to understanding what he thinks, we have to do more than examine what he says. We must see how he lives.

March 11, 2019

Against Suicide: Coping with Reality

Sisyphus by Titian, 1549

Sisyphus by Titian, 1549

(This essay by Ms. Sara Jane Wojcik clarifies her previous guest post. These thoughtful ruminations remind me of E. D. Klemke’s profound essay, “Living Without Appeal.”)

The most basic form of integrity is to accept reality for what it is rather than how we would like it to be. I have always loved science fiction writer Phillip Dick on this when he says, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” I am sympathetic to the sentiment that underlies Parfit’s viewpoint—I really am. The prospect of this grand panoply of life, with all its colors, characters, and challenges, amounting to nothing, either personally or ultimately, is sometimes almost more than I can bear.

But it’s hard not to conclude that his [Derek Parfit] efforts amount to an elaborate rationalization, a denial of the essential truth of life’s meaninglessness, by reading into reality something that is just not there. The continuity of universal process (physics yields chemistry yields biology to beget us) that he equates to a sort of immortality doesn’t ring true. Once I shed the “mortal coil” of my body through death, so, too, disappears the consciousness that constitutes the unique “me-ness” of my personal identity as Sylvia Jane. I am more than the sum the physical elements and processes that constitute me. Even if these physical elements could be reconstituted exactly in Parfit’s thought experiment terms, it could never amount to the same “me” because I would necessarily have different experiences. It’s that old idea that you can never step into the same river twice.

I’m not happy about this pessimistic conclusion, but I would rather accept it than delude myself with false comfort. I maintain that the best we can do is to pursue what I have called the fulfillment offered by “pure experience.” We can only cope, not cure. (my emphasis.) Depending on our personal tastes, these can vary widely, but in their highest form, they are all participatory and first person in nature. This begins with the visceral pleasures of good food and drink, exercise, creating art or building things, discovery, and lending a helping hand. Then there are joys of children and especially grandchildren, of course.

But at this point in my life, I think its highest form might be the opportunity to interact with and imbibe of the camaraderie with other thinkers about life’s Big Questions as I am here. (Would that it could be more of a face-to-face event over a good glass of wine!) I have this unquenchable thirst to simply know how it all hangs together. Isn’t that why we all visit this wonderful blog! Beyond the practical advantages, it’s simply fascinating and, to me, an end in itself.

This might seem like so much fluff. I imagine everyone mostly gets the point of my conception of the vitality that pure experience affords, but it might lack the impact or immediacy that it deserves because no matter how artful the words it is nearly impossible to convey. It might be somewhat off the topic of the post in question, but I’d like to offer the following piece called “Success” to make what I mean by pure experience more tangible. It has been apocryphally, though not undeservedly, attributed to Emerson, but was actually written by Bessie Stanley in 1904. I grant it might be a tad overly sentimental but I think it still works and remains relevant. Here is my amalgam of its several variants:

To laugh often, love much, and appreciate beauty;

To find the best in others

and win the respect of intelligent people

as well as the affection of children;

To earn the appreciation of honest critics

and endure the betrayal of false friends;

To fill your niche and accomplish your task

by leaving the world a bit better than you found it,

whether by a healthy child, a garden patch,

a perfect poem, a rescued soul,

or a redeemed social condition;

To know even one life has breathed easier

because you have lived.

To live a life that inspires,

and whose memory becomes a benediction:

This is to have succeeded.

I claim no great progress in this direction. All I can say is that I find as I get older I am perhaps getting a little better at it. I like to think that intent matters as much as result. If we honestly do the best we can, we really have succeeded—at least in moral terms.

Anyway … I have far less difficulty with the Russell quotation, but vicarious immortality through living on through others yields, to me, only false comfort. Though our descendants are certainly derived from us, they are not us. I see it as a sort of cultural form of Parfit’s argument from the physical.

______________________________________________________________________

As I am finishing this, I noticed Mr. Miller’s comments on a previous post. I do sympathize with his ever pessimistic sentiment but find myself resisting the suicide that, as he accurately describes, seems to be dictated by the logic underwritten by the reality of existence. Is this a weakness in me, I wonder, for I like to think of myself as a creature who lives consistent within the dictates of reason and the constraints of reality? This is what is so unnerving about the meaning-of-life problem! It’s bad enough that life evidently has no meaning beyond the intrinsic, but that that same existence includes creatures impelled by the biologic imperative to resist with all their might (and then some!) its implications for action makes my head spin in an effort to make sense out of it. As mentioned elsewhere, perhaps I hold out hope that time will reveal a “solution” simply not apparent at this time. More likely, though, I am simply being swept along by the biologic imperative to survive. There is, perhaps, a little comfort in viewing the situation as an exercise in irony, but, if truth be told, not much. So I go on, wandering in the dark, not knowing where—and certainly not why.

Against Suicide: Accepting Reality and Coping

Sisyphus by Titian, 1549

Sisyphus by Titian, 1549

(This essay by Ms. Sara Jane Wojcik clarifies her previous guest post. These thoughtful ruminations remind me of E. D. Klemke’s profound essay, “Living Without Appeal.”)

The most basic form of integrity is to accept reality for what it is rather than how we would like it to be. I have always loved science fiction writer Phillip Dick on this when he says, “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” I am sympathetic to the sentiment that underlies Parfit’s viewpoint—I really am. The prospect of this grand panoply of life, with all its colors, characters, and challenges, amounting to nothing, either personally or ultimately, is sometimes almost more than I can bear.

But it’s hard not to conclude that his [Derek Parfit] efforts amount to an elaborate rationalization, a denial of the essential truth of life’s meaninglessness, by reading into reality something that is just not there. The continuity of universal process (physics yields chemistry yields biology to beget us) that he equates to a sort of immortality doesn’t ring true. Once I shed the “mortal coil” of my body through death, so, too, disappears the consciousness that constitutes the unique “me-ness” of my personal identity as Sylvia Jane. I am more than the sum the physical elements and processes that constitute me. Even if these physical elements could be reconstituted exactly in Parfit’s thought experiment terms, it could never amount to the same “me” because I would necessarily have different experiences. It’s that old idea that you can never step into the same river twice.

I’m not happy about this pessimistic conclusion, but I would rather accept it than delude myself with false comfort. I maintain that the best we can do is to pursue what I have called the fulfillment offered by “pure experience.” We can only cope, not cure. (my emphasis.) Depending on our personal tastes, these can vary widely, but in their highest form, they are all participatory and first person in nature. This begins with the visceral pleasures of good food and drink, exercise, creating art or building things, discovery, and lending a helping hand. Then there are joys of children and especially grandchildren, of course.

But at this point in my life, I think its highest form might be the opportunity to interact with and imbibe of the camaraderie with other thinkers about life’s Big Questions as I am here. (Would that it could be more of a face-to-face event over a good glass of wine!) I have this unquenchable thirst to simply know how it all hangs together. Isn’t that why we all visit this wonderful blog! Beyond the practical advantages, it’s simply fascinating and, to me, an end in itself.

This might seem like so much fluff. I imagine everyone mostly gets the point of my conception of the vitality that pure experience affords, but it might lack the impact or immediacy that it deserves because no matter how artful the words it is nearly impossible to convey. It might be somewhat off the topic of the post in question, but I’d like to offer the following piece called “Success” to make what I mean by pure experience more tangible. It has been apocryphally, though not undeservedly, attributed to Emerson, but was actually written by Bessie Stanley in 1904. I grant it might be a tad overly sentimental but I think it still works and remains relevant. Here is my amalgam of its several variants:

To laugh often, love much, and appreciate beauty;

To find the best in others

and win the respect of intelligent people

as well as the affection of children;

To earn the appreciation of honest critics

and endure the betrayal of false friends;

To fill your niche and accomplish your task

by leaving the world a bit better than you found it,

whether by a healthy child, a garden patch,

a perfect poem, a rescued soul,

or a redeemed social condition;

To know even one life has breathed easier

because you have lived.

To live a life that inspires,

and whose memory becomes a benediction:

This is to have succeeded.

I claim no great progress in this direction. All I can say is that I find as I get older I am perhaps getting a little better at it. I like to think that intent matters as much as result. If we honestly do the best we can, we really have succeeded—at least in moral terms.

Anyway … I have far less difficulty with the Russell quotation, but vicarious immortality through living on through others yields, to me, only false comfort. Though our descendants are certainly derived from us, they are not us. I see it as a sort of cultural form of Parfit’s argument from the physical.

______________________________________________________________________

As I am finishing this, I notice Mr. Miller’s comments on a previous post. I do sympathize with his ever pessimistic sentiment but find myself resisting the suicide that, as he accurately describes, seems to be dictated by the logic underwritten by the reality of existence. Is this a weakness in me, I wonder, for I like to think of myself as a creature who lives consistent within the dictates of reason and the constraints of reality? This is what is so unnerving about the meaning-of-life problem! It’s bad enough that life evidently has no meaning beyond the intrinsic, but that that same existence includes creatures impelled by the biologic imperative to resist with all their might (and then some!) its implications for action makes my head spin in an effort to make sense out of it. As mentioned elsewhere, perhaps I hold out hope that time will reveal a “solution” simply not apparent at this time. More likely, though, I am simply being swept along by the biologic imperative to survive. There is, perhaps, a little comfort in viewing the situation as an exercise in irony, but, if truth be told, not much. So I go on, wandering in the dark, not knowing where—and certainly not why.

March 4, 2019

Derek Parfit, Personal Identity, and Death

What does it take for a person to persist from moment to moment—for the same person to exist at different moments?

In a previous post, my guest author Ms. Wojcik expressed worries that death undermines meaning or perhaps renders our lives altogether meaningless. (Her argument is actually much longer and more complex but I think that is the salient idea.)

An anonymous reader responded by claiming that there is no personal identity over time—we are continually dying and being reborn—an insight he claims should assuage our fear of death and help us realize that we should care for others about as much as we care about ourselves. To help explain, the reader quotes the philosopher Derek Parfit:

When I believed [that personal identity is what matters], I seemed imprisoned in myself. My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less. Other people are closer. I am less concerned about the rest of my own life, and more concerned about the lives of others.

When I believed [that personal identity is what matters], I also cared more about my inevitable death. After my death, there will be no one living who will be me. I can now redescribe this fact. Though there will later be many experiences, none of these experiences will be connected to my present experiences by chains of such direct connections as those involved in experience-memory, or in the carrying out of an earlier intention. Some of these future experiences may be related to my present experiences in less direct ways. There will later be some memories about my life. And there may later be thoughts that are influenced by mine, or things done as the result of my advice. My death will break the more direct relations between my present experiences and future experiences, but it will not break various other relations. This is all there is to the fact that there will be no one living who will be me. Now that I have seen this, my death seems to me less bad.

However, Ms. Wojcik didn’t find comfort in Parfit’s words. As she puts it:

It seems to me that just because the nature of the biologic process involves the swapping out of atoms, it does not follow that we are ever “different” persons. Rather, there is an essential continuity that does not get lost in the physiologic process of life, including sleep … What I am today does not originate as a copy of the previous day’s experiences, but rather it’s a continuously evolving stream of the experiences of a single conscious entity. That my experiences may have an effect on others provides no comfort or mitigate the finality of my death.

Brief Reflections – I don’t know how to resolve this dispute. On the one hand, I regard death as an ultimate evil to be defeated. On the other hand, I find the idea of my continuity with those who will continue on after my death to be both comforting and insightful. Bertrand Russell beautifully expressed this latter sentiment:

The best way to overcome it [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.

If we must die perhaps this is our best response.

February 24, 2019

Summary of Justice in Plato’s Republic

Bust of Pythagoras based on traditional iconography at the Museum Capitolini, Rome.

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Excerpt reprinted with permission.) https://darrellarnold.com/2018/10/07/...

Justice in the Individual

… According to Plato, the human soul is comprised of three parts — an appetitive, a spirited and a rational part — all of which pull individuals in differing directions. As Plato expresses this in the Republic, he asks us to envisage humans as comprised of a multi-headed beast, a lion, and a human. Each of these pulls the human soul in a different direction, as they vie for dominance. However, it is ultimately our choice to feed one or the other. We can choose to feed the multi-headed beast. But a life in which we do so becomes one where we consume ourselves, in which we are never satisfied, but always at war with ourselves. We can choose to feed the lion, but then we become a victim of our own desire for honor or pride. It is only by feeding the human that we will gain a harmonious soul, a fulfilled nature, and a happy human life.

The wise who pursue such virtue will not thereby fail to acknowledge the value of the other parts of the soul. But they will know to meet the needs of the lower soul in appropriate measure. Through the cultivation of a virtuous character, individuals are able to bring the lower parts of their souls under the control of their rational soul.

In contrast then to Glaucon who affirms a social contract perspective that justice is not intrinsically valuable but only valuable because it prevents individuals from being punished for being unjust. Plato argues that virtue is good in itself because it creates a harmony of the soul that is lacking among the vicious. Those with vices in fact lack control of the self. They become enslaved to their lower desires. So enslaved, they lack true sovereignty, the control of the self that comes with virtue alone.

The appetites and spirited part of the soul, in fact, are parts of the soul that humans share with other animals. What is really defining for humans qua humans, however, is the rational soul. To cultivate habits that subject our reason to the whims of our appetites, or to the desire for social recognition or honor that appeals to our spirited part of the soul, is to cultivate a character that is less the fully human. We only really fulfill ourselves, our natures, if we feed our rational soul more than any of our other parts.

Justice in society

Plato imagines the polity to have a similar tripartite structure to the individual. He argues that there just as an individual has a rational, a spirited, and an appetitive part, so does the polity. In a polity, classes of individuals occupy natural strata of society — the king, the aristocrats, and the workers. Each of these strata is an expression of individuals who are dominated by a differing part of the soul. A just society would be one dominated by the wise, who are dominated by their rational souls. Plato imagines rule by philosopher kings, who others obey out of an understanding of their own rightful place in society. An oligarchy would be ruled by multiple individuals, but individuals who were not wise but dominated by their desire for honor and social recognition. This would lead to certain compromises injustice as those pursuing honor would at times overlook the true needs of those in society. Finally, a democracy would be ruled by the multitude, but of those dominated by appetites.

Democracy, in Plato’s view, is the worst form of government and would have a tendency toward self-dissolution. Since individuals, dominated by their own desires and lusts, would vie for power and become embroiled in political conflict, democracy would tend toward entropy. A just society, by contrast, would be one in which the wise ruled and members of other strata knew their place.

Plato’s entire discussion of justice in the polity is very involved. Here I can do no more than point to some very general similarities between that view and the view of justice in the individual. In both cases, the rational part should rule the others. In Plato’s view, this is the only path to harmonious relations between an individual, who has a conflict-ridden soul and the polity, which, unless guided wisely, otherwise also tends toward disharmony.

Conclusion

Though Plato draws out similarities between justice of the individual and justice of the polity, this is, of course, quite a large assumption. Many may be attracted to his view that a certain sovereignty comes in gaining control of the self and living moderately, rather than controlled by one’s passions or emotions. Yet this would not commit them to an acceptance of his views on the virtues of hierarchical forms of government.

For most of Western history, however, many thought these views did pair well together. It was thought that the aristocratic rulers should have nobility of spirit, which would make them suitable for rule. The majority, the rabble, would always be unfit for self-rule. Only in the Enlightenment do we begin to see strong shifts away from this and does support democratic forms of government begin to become the norm rather than the exception.

February 18, 2019

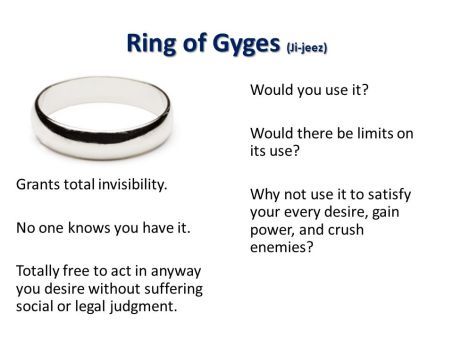

Summary the Ring of Gyges in Plato’s Republic

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission, edited slightly.)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/10/06/...

One of the most famous discussions of justice occurs in Book 2 of Plato’s The Republic

where Socrates’ interlocutor in the dialog, Glaucon, argues that there is no intrinsic reason to be just. The only reason to be just is to avoid the consequences of unjust actions. In making this point, Glaucon also highlights an anthropological underpinning for this view, namely the idea that people are largely selfishly motivated. He raises the issues of justice (from a perspective that Plato will reject) against the backdrop of a story that was well-known in Greece, the story of Gyges’ ring.

According to the story, Gyges, a young shepherd in the service of the King of Lydia was out with his flock one day when a great storm occurred. Near to where he was tending sheep, there was an earthquake, opening a crevice into the ground. Gyges descended into the crevice where he found, among other things, a bronze horse, with doors. Opening the doors, Gyges saw a human skeletal form possessing a golden ring. Gyges took the ring and ascended from the opening. Later in the month at a gathering of the shepherds of the King, Gyges noticed that twisting the ring on his finger, he disappeared. Those around him began speaking of him as if he weren’t there. Repeating this trial, it worked each time. Now, having acquired this new ability to become invisible, Gyges arranged to become a messenger sent to court. Once in court, Gyges used his magic ring to gain the graces of the queen, who he seduced. With the power to go undetected, he then managed to conspire with the queen to kill the king and to take over the kingdom.

Any man with similar power, Gyges maintains, would do the same. If we could get away with crimes that advanced our interest, we would all do so. The only reason that we are just is that we do not possess such magical rings and we thus would suffer negative consequences for acts of injustice. The implication of the story is that being just is not fundamentally in our interest. It is something we do as a compromise because we cannot get away with injustice. In short, no one is just for intrinsic reasons.

Beyond merely asking whether there is an intrinsic reason to be just, Glaucon also sets up the discussion with a clear hurdle. He asks: Is it always better to suffer injustice than to be unjust? Wouldn’t it, in fact, be better to have a reputation for justice while being unjust (at least in some instances) than to be just while suffering the negative repercussions of having a reputation for injustice?

We can all imagine situations where a just person is unjustly killed or imprisoned. Plato would certainly have been able to think of Socrates as one such example. But as bad as Socrates’ fate was, he was an aged man, who had lived a full life. What of someone, young and innocent, falsely accused of an injustice who might spend an entire life in prison? How does his life, just though it may be, stack up against the life of someone unjust but who goes undetected?

The view that Glaucon puts forward is a basis for a social contract view of justice such as we will see developed later in the history of philosophy by Hobbes and others. Glaucon’s proposal implies that we are essentially self-interested and amoral. We act morally not because morality fulfills our natures but because we have no other alternative.

In responding to Glaucon’s contractarian view Plato proposes an alternative view of human nature to that of the contractarians. We are, Plato will maintain, ultimately only fulfilled as human beings by being virtuous. Justice is thus intrinsically preferable to injustice. Indeed, Plato seems in general to underline Socrates’ view that care for the soul is our fundamental good. The only real harm is harm to the soul.

We will take up Plato’s response in our next post.

February 11, 2019

Futurism Remembering the 1950-60’s USA ‘Futurists’ – What Went Wrong?

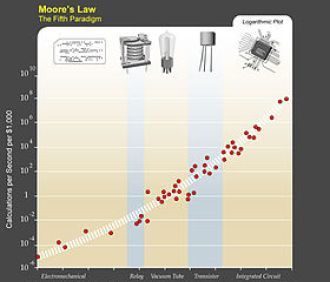

Moore’s law is an example of futures studies; it is a statistical collection of past and present trends with the goal of accurately extrapolating future trends.

(Alan Brooks, one of my regular readers, penned this essay about the history of futurism. I reprint it here, slightly edited for brevity, with his permission.)

Futurism in the United States properly began during the late 1950s and then took off in the 1960s with the Gemini space program and its ten manned flights. Then came Apollo which made futurism respectable. Unfortunately, with the prospect of landing on the Moon, futurist heads become giddy. It wasn’t hubris necessarily, it was more akin to being slightly intoxicated, tipsy, with anticipation; futurists knew if there were no more major accidents after Apollo 1 men would land on the Moon and space would rapidly be colonized. They were correct on the former but mistaken concerning the latter. The public lost interest after a few lunar landings and the Apollo program was soon canceled to concentrate on Skylab.

Concurrently the ‘back to nature’ movement was in large part a reaction to pollution in modern cities. Thus a new word was coined, “smog”—the haze of gasses floating over an urban area. Water and noise pollution also played a part. Such worries were new, as previously people worried about being poor and hungry, while a haze of gasses over a city was often looked upon as a symbol of vibrant industry and economic activity. How much better to enjoy modern life to its fullest, rather than fret about urban gases; dying of cancer at age 75 was preferable to death at age 40 …

Of all the manifestations of ‘back to nature’, the most practical was and still is an interest in ‘health foods.’ Of course, at the time many practitioners simply confused the natural for the healthy and taken to its ad absurdum il-logic, toadstools in one’s backyard are healthy. But while the majority of food additives are unnecessary, it is erroneous to think preservatives, for instance, should be dispensed with altogether or that we shouldn’t add chlorine to public water supplies. The fact is that some preservatives are required to keep food from spoiling and the addition of chlorine to water supplies is necessary for disinfection purposes. The notion of ‘health food’ was a new one as previously most people lived by the truism “eat drink and be merry, for tomorrow you may be no more.” …

Another manifestation of ‘back to nature’ was an emphasis on rural living. While some hardy souls did persevere in the rustic life, the majority of ‘back to nature’ enthusiasts eventually became bored with living on farms and would-be vegetarians would run to the nearest diner to purchase hamburgers when the craving for meat became unbearable.

This author remembers this 1970s Vandervogel movement, this time to the farm rather than to the countryside hike. Predictably, ‘70s rustic would-be vegetarian living did not last long. Although the idea of returning to rural simplicity was not new (more than a century before, romantics celebrated the rustic) no one has ever seriously returned to the rustic on a mass scale in modern times. Previous to the 1970s, most wanted to strike it rich, move to large homes, and eat at high-class restaurants, not live on poor farms eating tofu and alfalfa sprouts in a shack. It was ‘new’ in that in the past, rural living had been perceived as a necessity, while during the ‘back to nature’ era rural living was seen as a luxury—the luxury of escaping from polluted, hectic cities and conformist suburbs …

One common thread among today’s futurists is knowing the lure of conservatism is flawed

—we all move on in one way or another, via sickness, age, death, and so forth. Eventually, conservative values are altered beyond all recognition. You Can’t Go Home Again[image error], as in the title of Thomas Wolfe’s book—there is no return to the status quo.

Even the meaning of beautiful art, often considered an exemplar of permanence, changes. For instance, when Michelangelo and Botticelli painted scenes in the Sistine Chapel, those images had a more powerful hold on human imagination than they do in today’s secular world. “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving”, wrote Goethe.

Well, perhaps… but let’s not take Goethe’s word for it.