John G. Messerly's Blog, page 64

December 6, 2018

The Presocratics – Pythagoras

Bust of Pythagoras of Samos in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Bust of Pythagoras of Samos in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

Pythagoras was among the most celebrated philosophers of the Antique period. He supposedly was “the first to bring to the Greeks philosophy in general” and was the first to use the term ‘philosophy’ and to call himself a ‘philosopher.” His teaching focused on mathematics and rational inquiry, yet was thoroughly esoteric.

He is said to have traveled very broadly and to have incorporated teaching from everywhere he went. It is said that he met with and learned from Thales, as well as Anaximander. He is also thought to have studied geometry with the Egyptians and to have gained knowledge of ethics at Delphi. His esoteric teaching would have been particularly influenced by learning of the Orphic mysteries from Aglaophamus and to his initiation into the mysteries of Egyptian religion.

There are many myths surrounding Pythagoras’ life. One myth was that he had descended into Hades. Another was that he remembered his earlier lives, indeed that his soul had wandered and could remember “all the plants and animals it had been in and everything that his soul had experienced in Hades and that other souls there endure.” There are myths of him being a miracle worker. Some even worshiped him as a god.

The school that he founded, which is said to have lasted ten generations, was a sect devoted to theoretical learning, moral training, but also a strong indoctrination. There were levels to the initiation. Learners who joined the school would initially be silent for five years. After being tested they would then belong to the “household.” In the Pythagorean school, students were prohibited from eating animals, except for those that were allowed for sacrifices. Those were the animals into which the human soul does not migrate. Pythagoreans were “to abstain from beans as though from human flesh…and from almost all creatures of the sea.”

In a story surely apocryphal given its poetic (in)justice, Pythagoras is said to have died after the house where he was visiting Milo the Wrestler was set afire. He fled, but the jealous people who set the house ablaze caught up with him at a bean field when he refused to cross it. They there slit his throat. We might assume the tale is meant to sarcastically point out the absurdity of not eating beans, which were not consumed because they looked “like testicles or the gates of Hades.”

Despite the strangeness of the apocryphal stories surrounding Pythagoras and his school, we see in him great learning. He viewed the reality as numerical. He formalized the Pythagorean theorem, named after him. He and his students also came to understand the ratio character of musical scales. Along with Parmenides and the Eleatics he represents an epistemological orientation that is important in the development of Western thought — the focus of his thought being not primarily on sense experience but on concepts and logic. His focus, in particular, was on mathematical knowledge. With this focus, along with Parmenides, he was a was influence on Plato.

Side by side with great learning, however, Pythagoras and his students also displayed great dogmatism. Hippasus, who is said to have revealed how to draw the dodecahedron (and is thought by some to have developed the idea irrational numbers and thereby undermined the Pythagorean view of the rationality of the universe), was killed by the Pythagoreans, cast to sea.

December 2, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 7 – Optimism and Hope

continued from a previous entry

22. Attitudinal Optimism

One response to the failure of our intellectual analysis to demonstrate that life is or is becoming fully meaningful is to adopt, to the extent it’s possible, certain attitudes to help us live in the face of the unknown. Let’s consider two potentially helpful attitudes—optimism and hope.

Optimism is a tendency to expect the best possible outcome. Optimists believe that things will improve, while pessimists believe that things will worsen. I wholeheartedly reject such optimism because I don’t expect good outcomes or have faith that the future will be better.

Optimism also refers, not to expectations about the future, but to an attitude that we have in the present. This kind of optimism sees the glass as half-full rather than half-empty or looks on the bright side of life. Such optimism is generally beneficial—you tend to be happier seeing the glass half full. Thus I recommend this attitudinal optimism if it excludes expectations about the future which can easily lead to disappointment.

23. Attitudinal Hope

Hope also need not refer to an expectation but to an attitude we have in the present; a kind of hope illuminated by contrasting it with its opposite—despair. When we despair, we no longer care; we give up because our actions don’t seem to matter. After all, why play a game we can’t win or fight for a better world if it’s impossible to bring one about?

So attitudinal hope entails caring, acting, and striving. To hope is to reject despair—to care although it might not matter; to act in the face of the unknown; and to not give up. I don’t know if my actions will improve my life or help bring about a meaningful cosmos, but I can choose to hope, care, act, and strive toward those goals nonetheless. Again, this hope isn’t about future expectations; it’s an attitude which informs my present while rejecting despair or resignation. Such hope is the wellspring for the cares and concerns which manifest themselves in action.

Moreover, if I despair I won’t enjoy my life as if I adopt a hopeful attitude. Thus there is also a pragmatic reason for adopting a hopeful attitude—it makes my life go better. The only caveat is that the objects of our hopes must be realistic—having false hopes usually makes our lives go worse. In sum, attitudinal hopefulness rejects despair, leads to caring and acting and makes my life better.

A key difference between optimism and hope is that optimists usually believe that a desirable outcome is probable or likely whereas hope is independent of probability assessments. I may hope for unlikely outcomes but it’s hard to be optimistic about them. Another difference is that despair is more debilitating than pessimism. So while recommending both attitudinal optimism and attitudinal hope, I regard hope as somewhat more fundamental.

24. Wishful Hope

Yet hope is more than simply an attitude we adopt in the present; it also entails having certain desires, dreams, wants or wishes for the future. Again I reject such hopes if they include the idea of expectations, but I can have desires, dreams, wishes, or wants without expecting that they will be fulfilled. (I can wish or want to win the lottery without expecting to win.) Note this hopeful wishing is not faith since I don’t believe or have faith that my wishes will come true.

Like attitudinal hope, wishful hope rejects despair and spurs action. Hopes provide the impetus for acting, which in turn makes the fulfillment of what I hope for more likely. This connection between wishful hoping and action is straightforward. If I hope to become a physician and nothing prevents me from becoming one, then that desire may motivate me to act. In this sense, there is nothing intellectually objectionable or detrimental about wishful hoping—as long as there is a realistic possibility that such hopes can be fulfilled.

However, if the objects of our hopes are unachievable then hoping for them is futile—we set ourselves up for disappointment if we hope for the unattainable. Conversely, realistic hopes generally make our lives go better because they give us reason to live and to find meaning in the projects motivated by our hopes. I wholeheartedly recommend wishful hope.

to be continued next week …

November 29, 2018

The Presocratics – The One and the Many

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

One of the earliest disputes of the Greek naturalists and Eleatics concerned the question of the one and the many — that is was the substratum of the natural world or reality itself one substance or many? Parmenides is clearly a monist, who thought that all change and difference in the world was essentially illusory. Yet Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes were also monists. While they accept that there are many diverse entities in the world, they argue that the substrate underlying them or the primal stuff from which they emerge is singular. For Thales, they are all made of water. For Anaximander, they all come from the original unity of the unbound. For Anaximenes, they all stem from an original chaos but have aether as their basic element. Some of those who most clearly argue that the basic components of the world are not singular but multiple have not been mentioned.

Empedocles, who many early Greeks viewed as responsible for the developed teaching of the elements, is thought a pluralist. There is not one substance underlying the diverse things in the world; rather, there are a few key ones. The change we view in the world occurs over and above a “mingling and separating” of things that are themselves unchanging, primary oppositions: Wet, dry, cold and warm are eternal qualities that comprise all things, but that are propelled in their motion by two other eternal powers that also pull in opposition to one another, love and strife. The various things in the world around us do undergo change and transition as these eternal elements and forces ascend and recede from the foreground. Yet these basic qualities themselves are eternal. Basic reality, ultimate reality is not singular but plural. Empedocles is not a monist but a pluralist.

Another great “Presocratic” pluralist is Democritus, who was born just after Socrates, around 460 BCE — a reminder of the trouble with the temporal designation of “Presocratics.” The atomists maintain that the primary components from which all things in the world are comprised are atoms. From eternity, they have existed, with slightly different shapes and sizes. All things combine from a mixture of atoms and void. But the reality is expressed not by qualities of things. “By convention sweet and by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention color: in reality atoms and void.” Qualities that we experience only have an apparent reality. Some of the Ancients viewed Democritus as a skeptic, but Sextus, an early commentator on Greek natural philosophy, has contributed to a common view that makes greater sense in view of his various truth claims:

In the Rules[Democritus] says that there are two kinds of knowing, one through the senses and the other through the understanding. The one through the understanding he calls genuine, witnessing to its trustworthiness in deciding truth; the one through the senses he names bastard, denying it steadfastness in the discernment of what is true. He says in these words, “There are two forms of knowing, one genuine and the other bastard. To the bastard belong all these: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch. The other, the genuine, has been separated from this.” Then preferring the genuine to the bastard, he continues, saying, “Whenever the bastard is no longer able to see more finely nor hear nor smell nor taste nor perceive by touch, but something finer…

Over the course of time, Democritus sees the atoms combining into different formations, which for their part then again dissemble. In fact, the atomists propose an idea that various other Presocratics also shared — that over the course of time the cosmos emerges, then collapses only to later re-emerge.

November 25, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 6 – Skepticism and Meaning

continued from a previous entry

Skepticism

Yet, as we ascend these mountains of thought, we are brought back to earth. Looking to the past we see that truth, beauty, goodness, love, and meaning have emerged from cosmic evolution but so too have ignorance, loneliness, war, cruelty, despair, poverty, and pain. Surely serious reflection on this misery is sobering and we must temper our optimism accordingly.

We should also remember that if we find patterns of progress in evolution, we might be victims of confirmation bias. After all, progress isn’t the whole story of evolution—most species and cultures have gone extinct, a fate that may soon befall us. Furthermore, this immense universe (or multiverse) is largely incomprehensible to our three and a half pound brains, so we should hesitate to substitute an evolutionary view for our frustrated metaphysical longings. If reflection reveals that our deepest wishes may come true, our skeptical alarm bell should go off. For we want to know, not just to believe.

Yes, cosmic and biological evolution—and later the emergence of intelligence, science, and technology—leave us awestruck. But this doesn’t imply that we are meant to be here or that human consciousness was inevitable. It is only because we value our life and intelligence that we succumb to anthropocentrism. The trillions and trillions of evolutionary machinations that led to us might easily have led to different results—ones that didn’t include us. We want to believe evolution had us as its goal—but it did not. We are radically contingent, our existence serendipitous. Like the dinosaurs, we too could be felled by an asteroid.

So while we can say that meaning has emerged in the evolutionary process, we cannot say these trends will continue as evolution proceeds. We are moving, but we might be moving toward our own extinction, toward universal death, or toward eternal hell. We long to dream of better worlds but our skepticism awakens us from our Pollyannish imaginings. The evolution of the cosmos, our species, and our intelligence give us some grounds for believing that life might become more meaningful, but they offer no guarantees.

Here then is the essence of the problem. Despite our best efforts we may collectively fail to bring about this meaningful reality we imagine. In other words, while we know how life could be fully meaningful, we don’t know if it is or will become fully meaningful. We could only know that sub specie aeternitatis. So it seems that we can’t erase all our doubts or allay all our fears. As long as we are committed to intellectual integrity we must admit that life may be utterly absurd, futile, and meaningless. All of reality may be heading … nowhere. Our lives, our cares, our dreams … all for naught.

to be continued next week …

November 22, 2018

The Presocratics – Parmenides and Zeno

Bust of Parmenides

Bust of Parmenides

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/18/...

Hans Georg Gadamer, an important 20th century Germany hermeneutical philosopher, emphasizes … the importance of Parmenides and the Eleatics for Plato’s later theory of the forms. Like Plato … Parmenides, as well as Zeno and other Eleatics, dismisses sense experience as a source of truth. For these thinkers, it is the analysis of concepts that lead to a truth that one must affirm regardless of how out of sync it is with our common understanding of the world.

In Parmenides case, the great rational revelation concerned the constancy and unchangeability of Being. “What is is,” he wrote, “and what is not is not.” If something were to come into being, then it would now be nothing. But nothing cannot exist. Similarly, if something now existed it could not later no longer exist. If so, where there is now something there would later be nothing. But nothing cannot exist.

For Parmenides, the eyes and ears lead us astray. As he notes: “Seeing, they saw in vain; Listening, they failed to hear.” In his view, following the logic of the argument, we should recognize that Being is unitary and unchanging. Our ordinary, temporal understanding, it follows, must be illusory. Being must, by definition, be eternal without beginning and without end.

Other Eleatics, like Zeno, followed in Parmenides’ footsteps. Zeno developed a series of logical paradoxes to underline the Parmenidean view that change, as perceived by sense experience, is illusory. Zeno’s arrow paradox plays on a concept of time. If an arrow is shot toward a target, at any given instance in time it would find itself at rest at some place on the trajectory. Since at every instant the arrow is at rest, it could never move from the arrow to the target. Logic, Zeno argues, disproves that movement is possible. We should thus not trust our senses.

His racecourse paradox reaches a similar conclusion. Imagine Homer running toward a target. To get there, he would first have to get halfway there and to get halfway, he would first have to get to the half-way point of that half-way, ad infinitum. Between each space, however, there would be an infinite number of points to cross from one to another, since each half can again, mathematically be divided in half, ad infinitum. It is impossible to cross an infinitude, so the motion can never occur. The race could never start.

Though these paradoxes clearly have something wrong with them, they are mind-bending What are the problems with taking logic and applying it to realities of space and time in this way? Aristotle criticizes Zeno, as well as Plato. Plato, for his part, follows the lead of the Eleatics. He thinks we should follow reason even if it conflicts with sense experience. He like the Eleatics is thus known as a rationalist.

November 18, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 5 – Transhumanism and Meaning

continued from a previous entry

A Fully Meaningful Cosmos

Thus there are good reasons to believe that individual and cosmic death might be avoided. Yet immorality doesn’t guarantee a meaning of life, as the idea of hell so graphically illustrates. Immortality is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for a fully meaningful reality. But what do we mean by fully meaningful?

Meaningful things matter and they are good. But to be fully meaningful they must matter completely, be perfectly good and last indefinitely. The more we and the cosmos matter, the better we and the cosmos are, and the longer we and cosmos last, the more meaningful they are. In other words, a fully meaningful life and a fully meaningful cosmos are as significant, good, and long-lasting as they can possibly be. An individual life and the cosmos can be partly meaningful without meeting all of these conditions but they cannot be fully meaningful.

Can we then create a fully meaningful cosmos? I think this is plausible. To bring about such a glorious future we must enlarge our consciousness, perfect our moral natures, and overcome all human limitations. The philosophy which underlies these ideas is called transhumanism.

Transhumanism and Fully Meaningful Cosmos

Transhumanism is an intellectual movement that aims to transform and improve the human condition by developing and making available sophisticated technologies to greatly enhance human intellectual, physiological, and moral functioning. Transhumanism is based on the idea that humanity in its current form represents an early phase of its evolutionary development. A common transhumanist thesis is that human beings may eventually transform themselves into beings with such greatly expanded abilities that they will have become godlike or posthuman. Notably, this includes defeating the limitation imposed by death.

Now we may fail in these efforts, succumbing to asteroids, pandemics, nuclear annihilation, malevolent artificial intelligence, climate change, vacuum decay, a new Dark Ages, or scenarios we can’t now fathom. But if we do nothing, we will certainly perish. Without sci-tech we are helpless in the face of asteroids, pandemics, and all the rest. On the other hand, if sci-tech conquers individual and universal death and enhances our intellectual and moral faculties, then it will create the conditions that may eventually bring about a fully meaningful reality.

Transhumanism and Religion

What will be the effect of transhumanism on religion? If sci-tech defeats suffering and death religion will have lost its raison d’être—to soften the blow of suffering and death and to give life meaning. For who will pray for heavenly cures, when the cures already exist on earth? Who will die hoping for a reprieve from the gods, when science offers immortality? Who will look elsewhere for meaning when the world boasts a plenitude of it.

So, as our descendants continue to distance themselves from their past, they will lose interest in the gods. In a thousand or a million years our descendants, traveling through an infinite cosmos or virtual realities with augmented minds, won’t find their answers in ancient scriptures. Robust superintelligence won’t cling to the primitive mythologies that once satisfied ape-like brains.

Now some say that transhumanism is just a high-tech substitute for old-time religion and, yes, transhumanism has religious components. Transhumanists want infinite being, consciousness, and bliss as do those who imagine a beatific vision or other heavenly rewards. But there is a vast difference between having faith in the existence of a heaven and gods and actively trying to create them. Posthumans won’t die and go to heaven, they’ll (hopefully) create a heaven. In the future, the gods will exist … only if we become them.

The implication of all this is that we must take control of our destiny; we must become the protagonists of the evolutionary epic. If we don’t play God, no one will. There are risks, but with no risk-free way to proceed, we either evolve or we will die. That is the transhumanist message. But does the past offer any indication that the future really will be unimaginably better and more meaningful?

Cosmic Evolution and the Meaning of Life

Fortunately, a study of cosmic evolution supports the idea that life has become increasingly meaningful, a claim buttressed primarily by the emergence of beings with conscious purposes and meanings. Where there once was no meaning or purpose—in a universe without mind— there now are meanings and purposes. These meanings and purposes have their origin in the matter which coalesced into stars and planets, which in turn supported organisms that evolved complex brains. (I am also sympathetic with panpsychism which posits that mind was present from the beginning. Either panpsychism or emergentism explains mind.) And, since the minds from which meaning and purpose emerge are a part of the universe, part of the universe has meaning too.

This has a further profound implication—the universe is partly conscious. The story of cosmic evolution is of a universe becoming self-conscious through the conscious minds that emerge from it. Nature creates consciousness which in turn contemplates nature. Reality has grown the eyes so to speak with which it sees itself. We are as windows, vortexes, apertures or nodes through which the universe has become and continues to become ever more self-conscious. In short, when we contemplate the universe, it is partly conscious; and when we have purposes and meanings, parts of the universe do too.

But will the cosmos become increasingly conscious and meaningful? Will it progress toward complete meaning, or approach meaning as a limit? We can’t say for sure but there is a trajectory to past evolution: molecular processes were organized into cells; cells into organisms, and human organisms into families, tribes, cities, and nations. Uninterrupted, this could lead to global and interstellar cooperatives, with a concomitant increase in intelligence that may eventually lead to an omnipotent command of matter and energy—even to omniscience itself.

Think of it this way. If the big bang could expand into a universe almost a hundred billion light-years across, if some of the atoms in stars could become us, and if unconscious random genetic evolution and environmental selection could give rise to conscious beings, then surely we can direct cosmic evolution toward more perfect forms of being and consciousness. Or perhaps the universe is consciously doing this itself, as some panpsychists suggest. So there are good reasons to believe that reality may become increasingly meaningful.

The Meaning of Life

If we try to improve reality we may actualize its potential for full meaning. If we are successful in this project we will have been a part of something larger than ourselves. The part will have been meaningful in bringing about a fully meaningful whole. The meaning we found in our lives would then have been connected to … the meaning of life. In other words, the best ways to find meaning in life contribute to creating a meaning of life.

In practice, this implies that we find the deepest meaning in life by playing our small role in this upward progression of cosmic evolution. Individually our efforts are minuscule but collectively they transform reality. We do this in relatively mundane ways—nurturing our children, helping others, increasing our knowledge, caring for the planet, loving as best we can. These are simple things yet, simultaneously, they are the most important and meaningful ones.

Here then is our cosmic vision. In our imagination, we exist as links in a golden chain leading onward and upward toward higher levels of being, consciousness, truth, beauty, goodness, justice, joy, love and meaning—perhaps even to their apex. We dream that our descendants will gradually transform and perfect their moral and intellectual natures, make themselves immortal, and bring about a fully meaningful reality. And if all this comes true then there is a meaning of life.

to be continued next week …

November 14, 2018

Summary of David Benatar’s “The Human Predicament”

[image error]

I have previously written about the philosopher David Benatar’s anti-natalism. Now Oxford University Press has published Benatar’s new book The Human Predicament: A Candid Guide to Life’s Biggest Questions[image error]. Here is a brief summary of the book followed by a few comments.

Benatar’s book addresses the biggest question such as whether our lives are meaningful or worth living, and how we should respond to our impending death. He forewarns his readers that he won’t provide comforting answers to these questions. Instead, he argues

that the (right) answers to life’s big questions reveal that the human condition is a tragic predicament—one from which there is no escape. In a sentence: Life is bad, but so is death. Of course, life is not bad in every way. Neither is death bad in every way. However, both life and death are, in crucial respects, awful. Together, they constitute an existential vice—the wretched grip that enforces our predicament. (1-2)

The rest of the book explains this predicament. The basic structure of the argument goes something like this. While our lives may have meaning to each other, life is meaningless from a cosmic perspective; they have no grand purpose. “The universe was indifferent to our coming, and it will be indifferent to our going.” (200) Whatever little meaning our lives have is fleeting, and all human achievements ultimately vanish. In the end, it will all be as if we never were. This doesn’t imply that life has no meaning whatsoever, but “that meaning is severely limited.” (201)

However, even if our lives have some little meaning they are poor in quality and involve endless suffering. Some lives are better or luckier than others but in the long run, none of us fare well. It’s not that every moment is horrible but that sooner or later life will probably deal us some terrible fate. However, Benatar doesn’t conclude that since life is bad death is good. Instead, he argues that death is bad too. “Death does nothing to counter our cosmic meaninglessness and usually (though not always) detracts from the more limited meaning that is attainable.” (2-3)

Benatar doubts claims of immortality, even scientific ones, and also considers that immortality might not be a good thing. He grants that having the option of immortality would be better than not having it, but doubts that we will ever have that option. And while suicide doesn’t solve the human predicament it is sometimes the best choice we have. Yet, even when it is rational, suicide is tragic because it both affects others and annihilates an individual. Thus the prescription to “just kill yourself if it’s so bad” fails to appreciate our existential predicament.

This human predicament is not the product of a conscious agent, but of blind evolutionary forces. Yet human consciousness worsens the situation because humans “inflict colossal quantities of suffering and death on other humans. The deceits, degradations, betrayals, exploitations, rapes, tortures, and murders …” (203) However, while we should be pessimistic about the possibility of cosmic meaning, we can still obtain limited meaning. And this implies that

One should not desist from loving one’s family, caring for the sick, educating the young, bringing criminals to justice, or cleaning the kitchen merely because these undertakings do not matter from the perspective of the universe. They matter to particular people now. Without such undertakings, lives now and in the near future will be much worse than they would otherwise be. (205)

Naturally, people resist pessimistic views of life. Furthermore, they try to undercut them by claiming that adherents to pessimism are grouchy, pathological or macho individuals. While Benatar these adjectives describe some pessimists, they don’t describe them all. For many pessimism is an authentic response to one’s understanding of the human predicament.

So how then should we respond to the human predicament? First, we should cease having children and thereby perpetuating the cycle of suffering. But as we already exist, what can we do about our situation? Suicide might be a rational response, but better to invest some meaning into our lives.

An even better response would be to adopt a pragmatic optimism that recognizes the human predicament but uses optimism to cope. This would be most successful if one actually believed in an optimistic view. But suppose you only accept optimism as a kind of placebo? The optimist might recognize the horror of the human predicament but try to keep this horror at bay and remain optimistic. However, Benatar worries that this compartmentalization will be hard to maintain—to acknowledge the bleakness of life and yet remain optimistic. If you can’t maintain the correct balance here, you might become overly optimistic or revert back into pessimism.

The best coping mechanism would be to adopt pragmatic pessimism. Here you accept a pessimistic view of life without dwelling on it and busy yourself in projects that enhance and create terrestrial meaning. In other words “It allows for distractions from reality, but not denials of it. It makes one’s life less bad than it would be if one allowed the predicament to overwhelm one to the point where one was perpetually gloomy and dysfunctional … ” (211)

Benatar admits that the distinction between pragmatic optimism and pessimism as well as between denial and distraction are ambiguous. They exist midway in a continuum between “deluded optimism and suicidal pessimism.” (211) Like terminally ill patients we should confront our imminent death but not be so obsessed with it that we don’t spend time with our friends and family. So, while we can ameliorate our predicament somewhat, “this is the existential equivalent of palliative care.” (7)

In the end, the best we can do is to be the kind of “pessimists who have the gift of managing the negative impact of pessimism on their lives.” (213)

Reply – There is much to say about this book but let me mention a few things in passing. I believe that life is bad in many ways and so is death. The solution is to make life better and eliminate death. It may indeed be better if nothing had ever existed—assuming nothingness is even possible—but I just don’t know how to evaluate that claim. It may also be that something like Schopenhauer’s idea of blind will keeps us going and a rational analysis recommends putting an end to consciousness. But again I just don’t know how to evaluate such claims. Right now I enjoy my life, but then I’m a privileged white male in a first world country with a roof over my head, food in my refrigerator, access to medical care and the recipient of a wonderful education. I certainly understand that for many others life isn’t worth living and this fills me with irredeemable sadness. I wish I could say more about this.

The other thing I’d like to say is that I think the pragmatic response, whether slightly more optimistic or pessimistic is the correct approach. This aligns well with the kind of attitudinal and wishful hope that I’ve written about continually in this blog. The main difference in my approach is that I begin with ignorance or from a neutral point of view about the big questions whereas Benatar begins with some confidence that the answers to life’s big questions are pessimistic ones. Starting from my ignorance I claim that, assuming we have free choice, we might as well be optimists as that is pragmatically useful. As I’ve said many times this is no answer but a way to live. And in living we find the most meaning by making the world a better place.

November 11, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 4 – Death and Meaning

continued from a previous entry

Is There A Heaven?

Belief in personal immortality is widespread, yet there is little if any evidence for it. We don’t personally know of anyone coming back from the dead to tell us about an afterlife, and after people die they appear, well, dead. Yet people cling to any indirect evidence they can—near-death experiences, reincarnation and ghost stories, communication with the dead, etc. However, none of this so-called evidence withstands critical scrutiny.

Modern science generally ignores this supposed evidence for an afterlife for multiple reasons. First, the idea of an immortal soul plays no explanatory or predictive role in the scientific study of human beings. Second, overwhelming evidence supports the view that consciousness ceases when brain functioning does. If ghosts, souls, or disembodied spirits exist, then some of the most basic ideas of modern science are mistaken—which is very unlikely.

Now this cursory treatment of the issue doesn’t show that an afterlife is impossible. For that, we would need to answer complicated philosophical questions about personal identity and the mind-body problem. Suffice it to say that explaining either the dualistic theory of life after death—where a soul separates from the body at death and lives forever—or the monist theory—where a new body related to the earthly body lives on forever—is extraordinarily difficult. In the first case substance dualism must be defended and in the second case, the miraculous idea of the new body must be explained. Either way, the philosophical task is daunting. Clearly, the scientific winds are blowing against these ancient beliefs.

So while personal immortality based on supernatural considerations is logically possible, it’s easy to see that it isn’t very plausible. In the end, wishful thinking best explains belief in immortality, not reason and evidence. Therefore, I live under the assumption that my consciousness depends on a functioning brain and when my brain ceases to functions so will I. When I die, I doubt that I’ll move to a better neighborhood.

Death Is Bad For Us

But maybe death isn’t so bad. After all, there are undoubtedly fates worse than death. An indefinite hell is much worse and more meaningless than oblivion, and I prefer death to relatively short intervals of incarceration, dementia, or pain.

Nonetheless, death is bad because being dead deprives us of the good things of life. If life is on balance a good thing, then we are harmed by being dead even if death is devoid of experience. Note too that our aversion to death isn’t motivated exclusively by selfish concerns. We also don’t want others to die because we don’t want their value to be lost. In other words, our protestation against death reveals our fidelity to the intrinsic value of those we love.

Some people gainsay our worries about death, arguing that we should care no more about not existing after death than we now do about not having existed before death. But those situations aren’t symmetrical. While most of us want to live indefinitely into the future, almost no one wants their lives extended indefinitely into the past. We just care more about the future. We prefer a day’s suffering in the past to an hour’s suffering in the future; we prefer an hour’s pleasure in the future to a day’s pleasure in the past. Death doesn’t mirror prenatal nonexistence.

Others claim that death is really good for us because immortality would be boring, hopeless, or meaningless. This idea is promoted constantly by intellectuals. But people who say such things either really want to die or they deceive themselves. I think it’s the latter—they adapt their preferences to what seems inescapable. Happy, healthy people almost never want to die and are despondent upon receiving a death sentence. People cry at the funerals of their loved ones, accepting death only because they think it’s inevitable. I doubt they would be so accepting if they thought death avoidable.

So here’s our situation. After all the books and knowledge, memories and dreams, cares and concerns, effort and struggle, voices and places and faces, then suddenly … nothing. Is that really desirable? No, it isn’t. Death is bad. Death should be optional.

Individual Death and Meaning

What makes death especially bad is that being dead deprives us of the possibility of any future meaning. While death may not completely extinguish the meaning we find and create in life, it detracts significantly from that meaning by limiting the duration of our lives. This is easy to see. A life of a thousand years provides the possibility for more meaning than a life of fifty years, and the latter provides the possibility for more meaning than a life of five years. All other things being equal, a longer life holds the possibility for more meaning than a shorter one. And, needless to say, our deaths limit the amount of meaning we can contribute to other’s lives.

Nonetheless, many people claim that the prospect of our deaths actually makes life more meaningful by creating in us an urgency to live meaningfully now. But this isn’t true for everyone. Some people know their lives will be short and still live meaningless lives while others have good reasons to believe they will live long lives and still live meaningfully. Moreover, even if our imminent deaths focused us in this way that doesn’t justify all the meaning lost by our being dead.

However, while our individual deaths limit the meaning we can find and create in our lives, it’s still possible for there to be a meaning of life even if we die. If what ultimately matters isn’t our little egos but some larger purpose, and if our deaths somehow serve that purpose, then death may be acceptable. If this is true, then we could take comfort knowing that, after we’ve gone, others will pick up where we left off. By contrast, note how we recoil at the thought that shortly after we die all life will end or get worse. It seems then that some things do matter to us besides ourselves. Thus our deaths—while bad for us and others—don’t necessarily undermine the possibility of there being a meaning of life.

Cosmic Death and Meaning

However, cosmic death seemingly eliminates both meaning in and of life. The meaning we find in life might have had some small significance while we were living but cosmic death largely if not completely undermines that meaning. As for the meaning of life, it’s impossible to see how there can be one if everything fades into nothingness.

Now we might avoid our cosmic descent into nothingness and its implications if one of these conjectures is true: the death of our universe brings about the birth of another one; the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics implies that we somehow live on in different timelines; other universes exist in a multiverse; or, if all descends into nothingness, a quantum fluctuation brings about something from this nothing. Or maybe nothingness is impossible as Parmenides argued long ago.

Such speculative scenarios lead us back to the idea that something must be eternal for there to be a meaning of life. For if nothingness—no space, no time, nothing for all eternity—is our fate then all seems futile. We may have experienced meaning while we lived, and the cosmos may have been slightly meaningful while it existed, but if everything vanishes for eternity isn’t it all pointless? And, unfortunately, death appears inevitable for both ourselves and the cosmos. How then do we avoid feeling forlorn?

Scientific Immortality: Individual and Cosmic

Science is the most powerful method of gaining knowledge that humans have ever discovered; it is the only cognitive authority in the world today. Science is provisional, always open to new evidence, but therein lies its power. Like an asymptote where a line continually approaches a curve, scientific ideas slowly get closer to the truth as they advance. The practice of science winnows out bad ideas, leaving behind ever more robust ideas and the technologies they spawn. The entire technological world surrounding us attests to the truth of science. Put simply, if you want to fly, use an airplane; if you want to compute, use a computer; if you want to kill your infection, take an antibiotic; and if you want to protect your children, get them vaccinated.

One implication of all this is that, while a supernatural afterlife is highly unlikely, science and technology (sci-tech) may eventually conquer death. It’s possible that future generations will possess the computing power to run ancestor simulations; that my cryogenically preserved brain can be reanimated; that my consciousness can be uploaded into a robotic body or computer-driven virtual reality; or that some combination of nanotechnology, genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and robotics will defeat death. Individual immortality is plausible, maybe even inevitable, if sci-tech continues to progress. Perhaps our deaths aren’t inevitable after all.

As for the cosmos, our posthuman descendants may be able to use their superintelligence to avoid cosmic death by altering the laws of physics or escaping to other universes. And even if we fail other intelligent creatures in the universe or multiverse might be able to perpetuate life indefinitely. If superintelligence pervades the universe, it may become so powerful as to ultimately decide the fate of the cosmos. Perhaps then cosmic death isn’t foreordained either.

to be continued next week …

November 7, 2018

American Totalitarianism

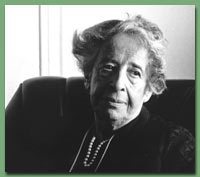

Hannah Arendt

(This article was originally published on my blog on December 29, 2016. It was also reprinted in the magazine of the Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies, in syndax vuzz, and Church and State. I thought it was a good time to reprint it here.)

“In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true. … Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie … The totalitarian … leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that … one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism. Instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.”

~ Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

For weeks now, I have been reading and blogging about dozens of articles from respected intellectuals from both the right and left who worry about the increasingly authoritarian, totalitarian, and fascist trends in America. Interestingly, when I tried to escape my scholarly bubble by looking for voices arguing that we are NOT heading in this direction, I came up empty. I found partisans or apparatchiks who maintain that all is good, but I couldn’t find hardly any well-informed persons arguing that we have nothing to worry about. I know there must be such people, but if there are they must be a tiny minority.

Now I did find informed voices saying that, in the long run, things will be fine. That the arc of justice moves slowly forward, that we take 1 step back but then take 2 steps forward. Such thinking about things from a larger perspective resonates with me. I write about big history and believe there may be directionality to cosmic evolution. I’ve argued that the universe is becoming self-conscious through the emergence of conscious beings, and I’ve even hypothesized that humans may become post-humans by utilizing future technologies. So I can’t be accused of ignoring the big picture.

However, at the moment, such concerns feel obtuse. Yes, it may be true that life is getting better in many ways, as Steven Pinker recently noted. But such thoughts provide little consolation for the millions who suffer in the interim. When people lack health care and educational opportunities; when they are deported, tortured, falsely imprisoned, or killed in wars; when they live in abject poverty surrounded by gun violence and suffer in a myriad of other ways, none of this is ameliorated by appeals to a far away future. Even if the world is better in a thousand years, that provides small consolation now.

What is almost self-evident is that America is now becoming more corrupt, and at a dangerously accelerating rate. In response, we must resist becoming like those of whom Yeats said: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” So I state unequivocally that I agree with the vast majority of scholars and thinkers—recent trends reveal that the USA is becoming more authoritarian, totalitarian, and fascist. The very survival of the republic is now in doubt.

Of course, I could be mistaken, as it’s hard to predict the future. Moreover, I am not a scholar of Italian history, totalitarianism, or the mob psychology that enables fascist movements. But I do know that all of us share a human genome; we are more alike than different. Humans are capable of racism, sexism, xenophobia, cruelty, violence, religious fanaticism, and more. We are modified monkey—in many ways we are a nasty species. As Mark Twain said: “Such is the human race … Often it does seem such a pity that Noah and his party did not miss the boat.”

Thus I resist the idea that fascism can happen in Germany, Italy or Russia, but not in America. It can happen here, and the signs point in an ominous direction. Furthermore, the United States was never a model of liberty or justice. The country was (in large part) built on slave labor as well as genocide at home and violent imperialism abroad. It is a first world outlier in terms of incarceration rates and gun violence; it is the only developed country in the world without national health and child care; it has outrageous levels of income inequality and little opportunity for social mobility; it ranks near the bottom of lists of social justice; it is one of the few countries in the world to condemn Article 25 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and it is consistently ranked as the greatest threat to world peace and the world’s most hated country.

Furthermore, signs of its dysfunction continue to grow. If authoritarian political forces don’t get their way, they shut down the government, threaten to default on the nation’s debt, fail to fill judicial vacancies, deny people health-care and family planning options, conduct congressional show trials, suppress voting, gerrymander congressional districts, support racism, xenophobia and sexism, and spread lies and propaganda. These aren’t signs of a stable society. As the late Princeton political theorist Sheldon Wolin put it:

The elements are in place [for a quasi-fascist takeover]: a weak legislative body, a legal system that is both compliant and repressive, a party system in which one party, whether in opposition or in the majority, is bent upon reconstituting the existing system so as to permanently favor a ruling class of the wealthy, the well-connected and the corporate, while leaving the poorer citizens with a sense of helplessness and political despair, and, at the same time, keeping the middle classes dangling between fear of unemployment and expectations of fantastic rewards once the new economy recovers. That scheme is abetted by a sycophantic and increasingly concentrated media; by the integration of universities with their corporate benefactors; by a propaganda machine institutionalized in well-funded think tanks and conservative foundations; by the increasingly closer cooperation between local police and national law enforcement agencies aimed at identifying terrorists, suspicious aliens and domestic dissidents.

Now with power in the hands of an odd mix of plutocrats, corporatists, theocrats, racists, sexists, egoists, psychopaths, sycophants, anti-modernists, and the scientifically illiterate, there is no reason to think that they will surrender their power without a fight. You might think that if income inequality grows, individual liberties are further constricted, or millions of people are killed at home or abroad, that people will reject those in power. But this assumes we live in a democracy. And a compliant and misinformed public can’t think, act or vote intelligently. If you control your citizens with sophisticated propaganda, mindless entertainment, and a shallow consumer culture, you can persuade them to support anything. With better methods of controlling and distorting information will come more control over the population. And, as long the powerful believe they benefit from an increasingly totalitarian state, they will try to maintain it. Most people like to control others; they like to win.

An outline of how we might quickly descend into madness was highlighted by David Frum, the conservative and former speechwriter for President George W. Bush. Frum envisions the following scenario which is, I believe, as prescient as it is chilling:

1) … I don’t imagine that Donald Trump will immediately set out to build an authoritarian state; 2) … his first priority will be to use the presidency to massively enrich himself; 3) That program of massive self-enrichment … will trigger media investigations and criticism by congressional Democrats; 4) ….Trump cannot tolerate criticism … always retaliating against perceived enemies, by means fair or foul; 5) … Trump’s advisers and aides share this belief [they] … live by gangster morality; 6) So the abuses will start as payback. With a compliant GOP majority in Congress, Trump admin can rewrite laws to enable payback; 7) The courts may be an obstacle. But w/ a compliant Senate, a president can change the courts … 8) … few [IRS] commissioners serve the full 5 years; 9) The FBI seems … pre-politicized in Trump’s favor … 10) Construction of the apparatus of revenge and repression will begin opportunistically & haphazardly. It will accelerate methodically …

Let me tell a personal story to help explain the cutthroat, no holds bar political world that is rapidly evolving in America today. Years ago I played high-stakes poker. It started out innocently, a few friends having a good time playing for pocket change. Slowly the stakes grew, forcing me to study poker if I didn’t want to lose money. My studies paid off, and I began to win consistently. Great.

Then I start playing with strangers, assuming my superior poker skills would prevail. But soon I started losing; finding out later that I was cheated. (I was being cold decked.) It turned out that my opponents played by a different rule—their rule was that I wasn’t leaving the game with any money. Then I discovered that some people will go further, robbing you at gunpoint of the money you had won. (This actually happened to me.) Once the gentleman’s rules of poker no longer applied, nothing was off-limits. Similarly, once the agreement to play by democratic rules is violated, all bets are off. For example, you begin to ignore the other parties Supreme Court nominees or threaten to default on the nation’s debts or ignore obstruction of justice in order to get your way. This is a sign that we have entered the world of mobsters and rogue nations, an immoral world. The logical end of this state of affairs is violence.

This describes the current political situation. The US Congress was once characterized by comity but is so no longer. From the period after World War II to about 1980, the political parties in the USA generally compromised for the good of the nation. The radicalization of the Republican party began in the 1980s and by the mid-1990s, with Republican control of the House of Representatives, the situation dramatically deteriorated. (Newt Gingrich is more responsible for this than anyone; he is possibly the worst American to live in this century.) One side was determined to get their way and wouldn’t compromise. It was now no holds barred.

In other words, American politics has entered a situation that game-theorists call the prisoner’s dilemma. A prisoner’s dilemma is an interactive situation in which it is better for all to cooperate rather than for no one to do so, yet it is best for each not to cooperate, regardless of what the others do. For example, we would have a better country if everyone paid their share of taxes, but it is best for any individual, say Donald Trump, not to pay taxes if he can get away with it. Put differently, you do best when you cheat at poker and don’t get caught, or control the situation if you do get caught. In politics this means you try to hide your crimes, but vilify the press or whistleblowers if you are exposed.

If successful in usurping power, you win in what the philosopher Thomas Hobbes called the state of nature. Hobbes said that in such a state the only values are force and fraud— you win if you dominate, enslave, incarcerate, or eviscerate your opponents. But the problem with this straightforward egoism, Hobbes thought, was that people were “relative power equals.” That is, people can form alliances to fight their oppressors. So while what Hobbes’ called the right of nature tells you to use whatever means possible to achieve power over others, the law of nature paradoxically reveals that this will lead to continual warfare—to a state of nature. The realization of this paradox should lead people to give up their quest for total domination and cooperate. They do so by signing a social contract in which they agree to and abide by, social and political rules.

But if we live in a country where people are radically unequal in their power—Democrats vs. Republicans; unions vs. corporations; secularists vs theocrats; African-Americans vs. white nationalists—then those in power won’t compromise with the less powerful. When the powerful few are imbued with the idea that they are better people with better ideas, and when they are drunk with their power, you can bet that the rest of us will suffer.

In short, it is a centuries old story. People want power. They will do almost anything to attain it. When they have it they will try to keep it, and they will try to divide those who should join together to fight them, hence they promote racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, etc. In the end, a few seek wealth and power for themselves, others want a decent life for everyone. Right now the few are winning.

November 4, 2018

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Part 3 – Philosophy, Science, and Meaning

continued from a previous entry

Western Philosophy and Meaning in Life

Western philosophers typically ignore the question of the meaning of life for one or more of the following reasons: 1) they reject supernaturalism; 2) they are uncertain the question makes sense; or 3) they doubt that we possess the cognitive wherewithal to answer the question. I too reject supernaturalism, although I think we can make reasonable inferences about the meaning of life if they are drawn from our best scientific knowledge. I’ll return to this later.

Regarding meaning in life, contemporary Western philosophers typically adopt one of three basic approaches—objective naturalism, subjective naturalism, or nihilism.

Objective naturalists reject supernaturalism and state that meaning can be found in the natural world by connecting with mind-independent, objective, intrinsic goods like truth, beauty, joy, justice, and love. According to these naturalists, we must want and choose objectively good things in order for our lives to be meaningful, so merely wanting and choosing arbitrarily is insufficient for a meaningful life. On this view, a life counting paper clips or memorizing long lists of phone numbers is not meaningful. Instead, paradigms of meaningful lives include those that search for truth, create beauty, act morally, or help others. The main problem with this view is that objective goodness might be illusory or, even if real, unable to provide sufficient meaning.

Subjective naturalists reject supernaturalism and argue that meaning is created by getting what we want or achieving our goals. On this view, meaning varies from person to person and can be found in any subjective desire. It doesn’t matter if we find meaning collecting coins, writing philosophy books, helping the homeless, or torturing innocent children. The main problem with this account is it permits us to find meaning by doing anything we want—including the immoral or trivial. This gives us a strong reason to reject a subjective approach to meaning.

Some philosophers combine these two approaches, arguing that meaning arises when we subjective attraction meets objective attractiveness. The idea is that while our lives are meaningless if we care about worthless or immoral projects, they are also meaningless if we don’t care about worthwhile or objectively good projects. Thus, the meaningful life is one that cares about the right things.

Nihilists argue that neither the cosmos nor individual lives have meaning because nothing has value, nothing matters, and all is futile. Some believe this because a god would be necessary for meaning and no god exists, and some argue that life would be meaningless even if a god was real. Others maintain that life is too boring, unsatisfactory or ephemeral to be meaningful, or that there is no universal morality to give life meaning.

But none of these answers fully satisfies. Nihilism haunts us and no amount of philosophizing is palliative in its wake, but why accept such a depressing conclusion if we can’t know that it’s true? Subjectivism provides a more promising response—we can live meaningfully without accepting religious or objectivist provisos—but we want more than subjective meaning; we want our lives to matter objectively. But even if objective values exist we can still ask, is that all there is? There may be good, true, and beautiful things but does that really matter in the end?

Tentatively, I’d say that by directing subjective desires toward (apparently) objectively good things, we can find meaning in life. But does science support such a conclusion?

9. Science and Meaning in Life

Putting this all together gives us a basic conception of good, happy, or meaningful lives. They are lives in which our fundamental needs for food, clothing, shelter, parental love, education, health-care, and physical safety are met; we are not obsessed with material possessions or wealth; we engage in productive work of our own choosing that allows for autonomy, mastery, and purpose; we care for and love both ourselves and others; and we show concern for the best things in life-like truth, beauty, goodness, justice, joy, and love. We might even say that by living a meaningful life we experience a kind of self-transcendence—by living them we transcend the ego.

So it isn’t too hard to find meaning in life—assuming our basic needs are met—what’s hard is choosing between the many different ways that life can be meaningful. Nonetheless, some claim that life is meaningless. Maybe such people are ignorant about what truly gives life meaning, or perhaps they lack life’s necessities, meaningful work, loving relationships, personal freedom, or physical and mental health. Many obstacles exist to finding meaning in life and if we find it we are indeed fortunate.

Is Meaning in Life Enough?

But should we be satisfied with the meaning available in life or should we want more? Here’s my answer. On the one hand, if we have too few desires we will be too easily satisfied with our lives and the current state of the world. On the other hand, if we have too many desires we will be too easily dissatisfied with our lives and the current state of the world. So we should be content enough to experience the meaning life offers while discontent enough to want there to be more meaning. Still, I admit that it is hard to find the best way to balance our outrage at suffering, injustice, and meaninglessness with equanimity, acceptance, and serenity.

Again, we should be grateful to be the kinds of beings who can live meaningful lives. If that is all life can give, we should be satisfied. Still, we can imagine that the meaning in our lives prefigures some larger meaning. We can envisage—and we desire—that there is a meaning of life.

For if everything we love, know, create, and care about ultimately vanishes, then the meaning we find and create in life is ephemeral. Against the backdrop of eternal oblivion, meaning in life is too shallow and fleeting to satisfy our hunger for cosmic meaning. We may find truth, create beauty, attain moral virtue, have a loving family and engaging work, but so what? How does this matter if everything evaporates into nothingness? What we really want then is a connection with some larger cosmic meaning and that seemingly demands that something is eternal.

to be continued next week …