John G. Messerly's Blog, page 63

February 11, 2019

Futurism Remembering the 1950-60’s USA ‘Futurists’ – What Went Wrong?

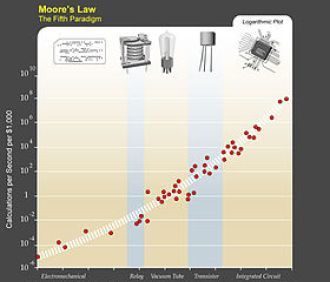

Moore’s law is an example of futures studies; it is a statistical collection of past and present trends with the goal of accurately extrapolating future trends.

(Alan Brooks, one of my regular readers, penned this essay about the history of futurism. I reprint it here, slightly edited for brevity, with his permission.)

Futurism in the United States properly began during the late 1950s and then took off in the 1960s with the Gemini space program and its ten manned flights. Then came Apollo which made futurism respectable. Unfortunately, with the prospect of landing on the Moon, futurist heads become giddy. It wasn’t hubris necessarily, it was more akin to being slightly intoxicated, tipsy, with anticipation; futurists knew if there were no more major accidents after Apollo 1 men would land on the Moon and space would rapidly be colonized. They were correct on the former but mistaken concerning the latter. The public lost interest after a few lunar landings and the Apollo program was soon canceled to concentrate on Skylab.

Concurrently the ‘back to nature’ movement was in large part a reaction to pollution in modern cities. Thus a new word was coined, “smog”—the haze of gasses floating over an urban area. Water and noise pollution also played a part. Such worries were new, as previously people worried about being poor and hungry, while a haze of gasses over a city was often looked upon as a symbol of vibrant industry and economic activity. How much better to enjoy modern life to its fullest, rather than fret about urban gases; dying of cancer at age 75 was preferable to death at age 40 …

Of all the manifestations of ‘back to nature’, the most practical was and still is an interest in ‘health foods.’ Of course, at the time many practitioners simply confused the natural for the healthy and taken to its ad absurdum il-logic, toadstools in one’s backyard are healthy. But while the majority of food additives are unnecessary, it is erroneous to think preservatives, for instance, should be dispensed with altogether or that we shouldn’t add chlorine to public water supplies. The fact is that some preservatives are required to keep food from spoiling and the addition of chlorine to water supplies is necessary for disinfection purposes. The notion of ‘health food’ was a new one as previously most people lived by the truism “eat drink and be merry, for tomorrow you may be no more.” …

Another manifestation of ‘back to nature’ was an emphasis on rural living. While some hardy souls did persevere in the rustic life, the majority of ‘back to nature’ enthusiasts eventually became bored with living on farms and would-be vegetarians would run to the nearest diner to purchase hamburgers when the craving for meat became unbearable.

This author remembers this 1970s Vandervogel movement, this time to the farm rather than to the countryside hike. Predictably, ‘70s rustic would-be vegetarian living did not last long. Although the idea of returning to rural simplicity was not new (more than a century before, romantics celebrated the rustic) no one has ever seriously returned to the rustic on a mass scale in modern times. Previous to the 1970s, most wanted to strike it rich, move to large homes, and eat at high-class restaurants, not live on poor farms eating tofu and alfalfa sprouts in a shack. It was ‘new’ in that in the past, rural living had been perceived as a necessity, while during the ‘back to nature’ era rural living was seen as a luxury—the luxury of escaping from polluted, hectic cities and conformist suburbs …

One common thread among today’s futurists is knowing the lure of conservatism is flawed

—we all move on in one way or another, via sickness, age, death, and so forth. Eventually, conservative values are altered beyond all recognition. You Can’t Go Home Again[image error], as in the title of Thomas Wolfe’s book—there is no return to the status quo.

Even the meaning of beautiful art, often considered an exemplar of permanence, changes. For instance, when Michelangelo and Botticelli painted scenes in the Sistine Chapel, those images had a more powerful hold on human imagination than they do in today’s secular world. “Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving”, wrote Goethe.

Well, perhaps… but let’s not take Goethe’s word for it.

February 4, 2019

Darrell Arnold: Philosopher and Musician

In addition to being a professor of philosophy, Darrell Arnold, my oldest and dearest friend, is an accomplished musician. I don’t know any other musician in the world today who combines the depth of thought of a professional philosopher with such musical gifts. His profound music and lyrics remind me of artists like Dan Fogelberg, Cat Stevens, Jim Croce, Jackson Browne, and James Taylor.

His most recent CD, “Changing World[image error],” is available through Amazon. Just click on one of the links above to purchase. Here is a sample song from the CD that Darrell wrote and performed for the funeral of a friend who had died of cancer. It is one of the most beautiful songs I’ve ever heard.

About Dr. Arnold – Originally from Nebraska, Darrell now lives in Surfside, Florida and regularly plays in the Miami area. His compositions are soulful folk-rock, with a twist of country blues. Darrell has recorded five studio CDs.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Darrell lived in Germany and worked into the club scene in Germany and Holland. There he played and arranged music with Darrell Arnold and the Dead Buffaloes and Darrell Arnold and the Buffalo Fish. He opened for two tours with the Yardbirds and played festivals with Canned Heat, Eric Burdon and the New Animals, Alvin Lee, and Joe Cocker. Darrell produced four CDs while in Germany. For Everyday Stories (2002), Darrell Arnold and the Dead Buffaloes won a national prize for CD production of the Year with the German Pop and Rock Music Association.

In the Miami area, over the past couple of years, Darrell has played regular shows with some excellent South Florida musicians, as they have arranged his songs and developed their live showcase. Changing World[image error], the fruition of this work, is Darrell’s fifth studio CD.

Finally, here is Darrell performing another song from the CD live without his band at WLRN Folk Music Radio. Just a singer/songwriter armed with his guitar, voice, and most of all, his deep and probing mind. How fortunate I’ve been to have been a friend of this talented man for more than 30 years.

[image error]

January 28, 2019

The Will to Doubt: Summary of Bertrand Russell’s “Free Thought and Official Propaganda”

Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, London, WC1R 4RL

What is wanted is not the will-to-believe, but the wish to find out, which is its exact opposite. ~ Bertrand Russell

In 1922 Bertrand Russell delivered his Conway Memorial Lecture, “Free Thought and Official Propaganda[image error],” to the South Place Ethical Society, the oldest surviving freethought

organization in the world and the only remaining ethical society in the United Kingdom. (It is now called the Conway Hall Ethical Society.) The lecture was later included in his anthology The Will to Doubt[image error].

The main theses of the lecture are to: 1) advocate for freedom of expression; 2) champion the will to doubt; 3) explain the origins of dogmatism; and 4) promote critical thinking.

Free Expression

Russell begins by noting his agreement with the common definition of “free thought” as the rejection of popular religious beliefs.

I am myself a dissenter from all known religions, and I hope that every kind of religious belief will die out. I do not believe that, on the balance, religious belief has been a force for good. Although I am prepared to admit that in certain times and places it has had some good effects, I regard it as belonging to the infancy of human reason …

However, Russell argues that the term should also refer more broadly to having and being allowed to express any opinion without penalty. Yet many ideas—for example, anarchism

or polygamy—are considered so immoral that we don’t tolerate them. But suppression of unpopular ideas is exactly the view that allowed torture during the Inquisition.

Russell then describes incidents in his own life to illustrate the lack of freedom of thought.

He was forced to be raised Christian despite his dying father’s wishes.

He lost the Liberal Party nomination for Parliament because he was an agnostic.

He was denied a Fellowship at Trinity College because he was considered too “anti-clerical.” And when he later expressed opposition to World War I, he was fired.

Russell concludes this section by advocating total freedom of expression.

The Will to Doubt

Next, Russell turns to the importance of the will to doubt. He was responding to William James‘ notion of the will to believe. James had claimed that even without (or with conflicting) evidence, one might be justified in choosing to believe in something—like Christianity for example—simply because it may have beneficial outcomes. But this “will to believe,” binds one to many untruths and halts the search for further truths.

Russell contrasts such an attitude with what he calls “the will to doubt,” which is choosing to remain skeptical as a means of eventually understanding more truth.

William James used to preach the “will-to-believe.” For my part, I should wish to preach the “will-to-doubt.” None of our beliefs are quite true; all have at least a penumbra of vagueness and error. The methods of increasing the degree of truth in our beliefs are well known; they consist in hearing all sides, trying to ascertain all the relevant facts, controlling our own bias by discussion with people who have the opposite bias, and cultivating a readiness to discard any hypothesis which has proved inadequate. These methods are practiced in science, and have built up the body of scientific knowledge … In science, where alone something approximating to genuine knowledge is to be found, [it’s] attitude is tentative and full of doubt.

In religion and politics on the contrary, though there is as yet nothing approaching scientific knowledge, everybody considers it de rigueur to have a dogmatic opinion, to be backed up by inflicting starvation, prison, and war, and to be carefully guarded from argumentative competition with any different opinion. If only men could be brought into a tentatively agnostic frame of mind about these matters, nine-tenths of the evils of the modern world would be cured. War would become impossible, because each side would realize that both sides must be in the wrong. Persecution would cease. Education would aim at expanding the mind, not at narrowing it. [People] would be chosen for jobs on account of fitness to do the work, not because they flattered the irrational dogmas of those in power.

As an example of the benefits of this kind of actual skepticism, Russell describes Albert Einstein‘s overturning of the conventional wisdom of physics and Darwin‘s contradicting the Biblical literalists. As soon as there was convincing evidence of these truths, scientists provisionally accepted them. But they didn’t dogmatically regard them as the final word incapable of further refinement.

Russell states his conclusion of this section in a single, concise sentence, “What is wanted is not the will-to-believe, but the wish to find out, which is its exact opposite.”

Dogmatism

Yet despite the fact that rational doubt or fallibilism is so important, individuals and cultures often adopt an irrational certainty regarding complicated issues. But why? Russell believes this results partly “due to the inherent irrationality and credulity of average human nature.” But three other agencies exacerbate these natural tendencies:

1 – Education — Public education doesn’t teach children healthy learning attitudes, but often indoctrinates children with often patently false dogma. As he puts it:

Education should have two objects: first, to give definite knowledge—reading and writing, language and mathematics, and so on; secondly, to create those mental habits which will enable people to acquire knowledge and form sound judgments for themselves. The first of these we may call information, the second intelligence.

2 – Propaganda — People aren’t taught to weigh the evidence and form original opinions, so they have little protection against dubious or false claims. As Russell states: “The objection to propaganda is not only its appeal to unreason, but still more the unfair advantage which it gives to the rich and powerful.”

3 – Economic pressure — The State and political class use its control of finances and economy to impose its ideas, restricting the choices of those who disagree. They want conformity. In Russell’s words:

There are two simple principles which, if they were adopted, would solve almost all social problems. The first is that education should have for one of its aims to teach people only to believe propositions when there is some reason to think, that they are true. The second is that jobs should be given solely for fitness to do the work.

This second point led Russell to emphasize tolerance: “The protection of minorities is vitally important; and even the most orthodox of us may find himself in a minority some day, so that we all have an interest in restraining the tyranny of majorities.”

Critical Thinking

And tolerance for Russell connects with the will to doubt: “If there is to be toleration in the world, one of the things taught in schools must be the habit of weighing evidence, and the practice of not giving full assent to propositions which there is no reason to believe true.” While Russell doubts that our moral defects can be easily improved, he argues that we can improve our intellectual virtue. Note the prescience of his ideas regarding disinformation:

Therefore, until some method of teaching virtue has been discovered, progress will have to be sought by improvement of intelligence rather than of morals. One of the chief obstacles to intelligence is credulity, and credulity could be enormously diminished by instructions as to the prevalent forms of mendacity. Credulity is a greater evil in the present day than it ever was before, because, owing to the growth of education, it is much easier than it used to be to spread misinformation, and, owing to democracy, the spread of misinformation is more important than in former times to the holders of power.

Russell concludes by asking how we might nurture a world where critical thinking reigns.

If I am asked how the world is to be induced to adopt these two maxims — namely: (1) that jobs should be given to people on account of their fitness to perform them; (2) that one aim of education should be to cure people of the habit of believing propositions for which there is no evidence—I can only say that it must be done by generating an enlightened public opinion. And an enlightened public opinion can only be generated by the efforts of those who desire that it should exist.

My brief thoughts

If we are educated to think freely and critically, which itself encourages the will to doubt, the human condition would improve. Only if we emphasize the truth, rather than lies and propaganda, can we create a world where we all can survive and flourish. After a lifetime of pursuing truth, I have concluded that lying may be the greatest sin of all.

January 21, 2019

The Basics of Taoism

[image error]

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/11/...

Laozi

Along with Confucius, Laozi is one of the two main thinkers of importance in the history of Chinese philosophy. In early periods of Chinese history, the philosophies of the two schools to develop from their thought (Confucianism and Taoism) are viewed as in rivalry. However, in the Middle Ages, a syncretism developed between Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. Ideas from each of these philosophical schools were thought to have an appropriate place in a balanced life.

There is much legend surrounding the life of Laozi. Some have even questioned whether he lived at all. Most, however, accept that he did live at around the same time as Confucius, in the 6th century BCE. While Confucius, however, develops what is

largely a social theory, the focus of Laozi is on a metaphysics and individual ethics.

Laozi and the Tao te Ching — Introduction

It is difficult to know what precisely Laozi (also Lao Tzu) thought. Though according to legend he was the author of the Tao te Ching, scholars now know this isn’t the case. Stylistically, the various parts of the book differ too extremely from one another. In addition, some of the aphorisms in the book are known to have pre-dated the 6th century BCE when he is thought to have lived.

The text is generally thought to have been completed in the 3rd century BCE. It may well be that going back in Chinese history, the aphorisms in the Tao te Ching became part of an oral culture, passed on among groups of Taoists. The Tao te Ching is the most translated book in the world except for the bible. And there have been over 200 commentaries on the work since it was written. For the sake of convenience, I will here attribute the ideas of the Tao te Ching to the legendary Laozi.

The Tao

Laozi is known for the emphasis on the Tao. Translated variously as the way, or nature’s way, there were two main characteristics of the Tao. It was used as a verb “to direct,” “to guide,” or “to establish communication.” As a noun, it was used to refer to the order of nature familiar in the patterns of seasons and the alterations between night and day and so on. The Tao was thought to reflect the complimentary oppositions of the yin and yang, principles of the cosmic order, which became associated with female and the male, the dark and the light, the cold and the hot, the damp and the dry. In Taoism, this idea of nature’s balancing of oppositions takes on a greater clarity than in the Heraclitian or ancient Greek world generally.

A focus of Laozi, however, becomes to guide or direct or show the way for individuals to establish a conscious connection with this cosmic order. In the main Laozi emphasizes an ethics or, even more broadly, a general form of life, that will create the means of communication with the Tao, with nature’s Way.

Laozi emphasizes the reality is a dynamic process. However, the precise character of the process remains somewhat unclear.

The Unknowable Tao

As the Tao te Ching opens: “The Tao that can be trodden is not the enduring and unchanging Tao. The name that can be named is not the enduring and unchanging name.” (Tao te Ching, 1)

The Tao is a reality that Laozi does not think can be known absolutely. The unchanging Tao is beyond human categorization and conceptualization. The concepts we develop for it, and this would apply to those like Yin and Yang and the concepts that we use to describe its process, have a contingency and incompleteness.

The Tao as mother of all things

That said, the Tao te Ching goes on to describe quite a lot. “(Conceived of as) having no name, it is the Originator of heaven and earth; (conceived of as) having a name, it is the Mother of all things” (Tao te Ching, 1). The Tao is thought to pre-exist all things. It is the source of creation.

Yet, while the Tao is the source of all things, it is not for that a separate creator: “All things depend on it for their production, which it gives to them, not one refusing obedience to it. When its work is accomplished, it does not claim the name of having done it. It clothes all things as with a garment, and makes no assumption of being their lord…” (Tao te Ching, 34).

The Tao is best conceived as a foundation of all reality, as a system in flux, but unfolding with certain regularities.

Balancing oppositions

The Tao in the Tao te Ching, like the cosmos in thought of the Ancient Greek Philosopher Heraclitus, is viewed as fundamentally in process as oppositions are balanced. “The movement of the Tao by contraries proceeds” (Tao te Ching, 40). Or as Chapter 2 already notes: “All in the world know the beauty of the beautiful, and in doing this they have (the idea of) what ugliness is; they all know the skill of the skillful, and in doing this they have (the idea of) what the want of skill is.” On the one hand, here the emphasis is on the balance of oppositions in the world. On the other, the focus is also on the inevitability of oppositions for our conceptual understanding. We do not know the beautiful without a concept of the ugly, and so on.

Emptiness

While highlighting the oppositions that comprise the Tao with a great clarity, the Tao te Ching also focuses on emptiness and nothingness. “The Tao is (like) the emptiness of a vessel; and in our employment of it we must be on our guard against all fullness” (Tao te Ching, 4). Or, for a text emphasizing emptiness in multiple contexts: “The thirty spokes unite in the one nave; but it is on the empty space (for the axle), that the use of the wheel depends. Clay is fashioned into vessels; but it is on their empty hollowness, that their use depends. The door and windows are cut out (from the walls) to form an apartment; but it is on the empty space (within), that its use depends.

Therefore, what has a (positive) existence serves for profitable adaptation, and what has not that for (actual) usefulness” (Tao te Ching, 11). Nonbeing is as fundamental or more fundamental than Being in Taoism, as in Buddhism.

Intuition and its critical limitations

Laozi is known for emphasizing the need for a mental intuition in order to achieve this understanding of the Tao. In this, he downplayed very much the importance of education, which he saw as indoctrinating individuals into preconceived views of what is right and wrong and to limited views of reality.

Laozi was thus not known for encouraging an empirical and rational critical outlook. Xunzi, the third century BCE Confucian scholar criticized him saying “Lao Tzu understood looking inward but knew nothing of looking outward” (Qtd. in Kahenmark, 20). Early sources maintain that he was gifted with a spiritual intuition. As noted in the Chuang Tzu, he, along with Kuan Yin “made [their teaching’s] basic principle the Permanent Unseen and its ruling idea the Supreme One. Their outward demeanor was gentle and accommodating; their inward principles were perfect emptiness and noninjury to all living creatures” (Chapter 33, Qtd. in Kahenmark, 21).

The epistemology at work in Laozi is more instrumentalist than realist. Named things have a contingent use value. But it is not through reflective analysis that we will know the law of balance of the Tao or the order of the cosmos. It is a spiritual intuition that leads to a more reliable kind of knowledge. The harmony with the Tao is not achieved through discursive reason. Rather, it is achieved through a spiritual insight.

Ethics and political thought

This insight of the unity of all things in the Tao also has its benefits for the ethical life. Comprehending this unity, individuals do not assert their own ego interests above that of others. Rather they willingly engage in cooperation with one another. The Taoists tended to emphasize a fundamental goodness of human nature. For this reason, they opposed a heavy-handed legalist framework. In the view of the Taoists, laws were not necessary to generate civility or cooperation among people. They thus argued for a minimalist political framework. “Governing a small country is like frying a small fish. You ruin it by poking too much” (70). Too much government would, in Laozi’s view, cause more problems than it solved: “The more restrictions and prohibitions there are, the poorer the people will be” (57).

The ideal of Laozi, however, is small village life. One might wonder whether the rather lassie faire political philosophy works well in cosmopolitan cities with individuals who do not share common cultural ideals or in other general contexts of global governance.

January 7, 2019

The Basics of Confucianism

Temple of Confucius of Jiangyin, Wuxi, Jiangsu

Temple of Confucius of Jiangyin, Wuxi, Jiangsu

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/07/...

Confucius’ life

Confucius, or “Master Kung” as he became known, was born in the city of Lu (now known as Qufu) in the Northeast of China in 551 BCE and he died in 479 BCE.

According to legend, his father died at the age of 70 and he was raised by his mother. Women in the Confucian system of political philosophy are important in childhood education, as Confucius’ mother is thought to have been in his own upbringing. Besides studying history and music, as a child, he learned hunting, fishing, and archery. Confucius exemplified in his own life the rather broad set of competencies and broad minded interests that come to be thought befitting of a well-developed gentleman within the Confucian system of education. He married but divorced.

Confucius spent a part of his early life as a civil servant for the Duke of Lu. According to legend he had great success in that position, but his job was compromised due to the jealousy of others. After leaving that position, he spent his life as a scholar and educator. He developed the system of political philosophy that would come to dominate Chinese society for more than 2000 years. As a scholar, he traveled from town to town, with students who followed him. He sought throughout his life to again find work as a political advisor, as he thought that having the opportunity to positively influence political institutions was key to creating the conditions for the self-development of individuals. He found such work again at the age of 67 as an advisor for the Duke of Ai.

The texts of Confucius

For most of Chinese history, Confucius was thought to have edited (or written) five books which became known as the Confucian Classics. These books covered areas thought integral for the well-rounded education of civil servants. These included:

The Classic of Poetry — a book of 305 poems and songs, performed at court ceremonies

The Book of Documents — a book of documents and speeches attributed to leaders of the Chao period

The Book of Rites — a description of ancient rites and ceremonies

I Ching — a book of divination

Spring and Autumn Annals — a historical record of the region of Lu from which Confucius came

Besides these texts, the Analects is the collection of sayings of Confucius, early compiled by his students. It consists largely of proverbs, thematically related in sections. From this text, in particular, we cull some of the basic ideas of Confucius.

The warring state period

Confucius, like Laozi, lived in a period of political disarray in China, known as the warring states period. The time was one of political dissolution in which the unity of the Chou dynasty was eroded and small state conflict was dominant. Various philosophical and political systems were developed at this time with the aim of helping to reestablish a better functioning political order.

Besides Confucianism and Taoism, in political thought the period gives rise to legalism, which sought strong centralist policies for the empire, and Mohism, which argued for the need to rule in accord with “the will of heaven,” but offered a utilitarian standard of considering the greatest benefit (li) for the people. While Taoism argued for a return to largely self-government, or even anarchism, with the small village unit as a model, Confucianism argued for reestablishing the feudal ideal identified with the earlier Shang and Zhou dynasties.

Confucius as a model

Like Socrates’ in Ancient Greece, Confucius’ life is thought of as exemplary. Though Confucius did not think of himself as a sage, in Chinese history he has come to serve in particular as an example of a normal individual who is able, through his own efforts, to become a sage. He is not a prophet with a divinely inspired message. He is not a mystic. He is a scholar who strives to live virtuously. In fact, Confucius sees himself not as the founder of a school but as one individual in a long line of scholars (Ju chia) which extends back to the era of the Shang dynasty, circa 1100 BCE.

Views of religion

Though Confucianism was intricately tied into the state religion in China, Confucius did not teach much about the gods. His is not primarily a religious philosophy but a political philosophy. As noted in the Analects, “The Master did not talk about marvels, feats of strength, irregularities, gods” (7/21).

We often find Confucius expressing hesitancy to discuss questions of traditional religion. The following is indicative: “Chi-lu asked about serving the ghosts and gods. The Master said, ‘Until you can serve men how can you the ghosts.’ ‘Permit me to ask about death.’ ‘Until you know about life how can you know about death?’” (11/12)

Similarly, it is noted: “The Master said, ‘To work for the things the common people have a right to and to keep one‘s distance from the gods and spirits while showing them reverence can be called wisdom.’” (6/22)

That said, Confucius did emphasize the importance of ritual for a virtuous life. And the civic religious functions played an important role in this. Still, we might say that he sees religion more in the service of a good life than man in the service of religion.

Self Development

The focus on Confucius is on self-development. In the Confucian worldview this not means that one lives with a focus on narrow self-interest, but with an understanding of how one’s life and well-being is tied into that of others. One becomes self-developed through cultivating virtues and fulfilling one’s social role.

Jen and Li

Of special importance for self-development are the virtues of Jen and Li. Jen is a virtue entailing conscientiousness, empathy, and altruism (that is, action done for the benefit of others, not ourselves). Li is translated as rites, ceremonies, or customs. Here religion clearly played role, but Li extends beyond the religious rights tot he cultivation of custom. All of this is to play a part in helping us develop Jen. In fact, the everyday rituals and customs can serve to wake us to the special character of the everyday world we are immersed in. It can foster our empathy and serve to undergird the social order.

Interlinked connections

While both Taoism and Confucianism underline the need for self-development in harmony with the Tao, their understandings of what this entails differ from each other. The Taoists have a much greater focus on individualism and spirituality as traditionally understood. Confucianism, by contrast, sees our harmony with the Tao and our self-development as taking place always against the backdrop of our existing social relationships. We fulfill ourselves and live in harmony with the Tao by fulfilling our roles as sons or daughters, fathers, and mothers, within the family, or by fulfilling our roles as civil servants within the state.

The well-ordered society is key to well-ordered individuals. And developing ourselves requires contributing to our society in its various social systems. Human life is characterized fundamentally by a network of relationships of interlinked systems. The self finds itself interlinked with a family, within a city, within a regional government, within an empire, within the world. The Tao is aligned when each of these system levels is aligned.

Education

The study of the earlier mentioned five classics was thought integral to the education of civil servants throughout most of Chinese history. The works cover various domains of human life, and the study of them was to instill in them the importance of artistic expression, social processes and social systems, rituals, and considerations of metaphysics. These were tracked formally to the poetic vision, political vision, social vision, metaphysical vision, and historical vision. Each of these domains is key to our own self-development. They are domains of human expression that shape us. A wise civil servant shapes our social and political institutions with a view to the importance of each of these domains of human life, in service of the goal of virtue.

The Mandate of Heaven

Confucius emphasized that an emperor had a great responsibility to lead by virtuous example. As stated in the Analects: “Direct the people with moral force and regulate them with ritual, and they will possess shame, and moreover, they will be righteous.” (2.3)

The leader should be a well-rounded developed individual, who lives virtuously and properly embodies the empire’s customs and conscientiousness. Such an exemplary leader governs not for himself but to meet the needs of those in the kingdom. Seeing this, the people will follow his example. This is key to aligning the earth with heaven, for aligning action with the Tao. Under the best circumstances, this occurs, and the emperor is owed allegiance.

However, if an emperor fails to fulfill his role, then Confucianism came to accept that an empire could rightfully be overturned and a new imperial order could be instituted that did fulfill its correct purpose. The old empire — failing to fulfill its purpose — would lose the mandate of heaven. A new dynasty could then ascend and gain it. The kind of regime change that was imagined here would, of course, be extremely rare.

The rectification of names

The Confucian system developed a quite rigid set of roles for individuals within the imperial system. As very concisely expressed in the Analects:

“Let the ruler be a ruler, the subject a subject, a father a father, and a son a son” (12.11).

Confucianism became quite focused on obligations associated with the roles one had in society. These roles also paid respect to and solidified a set of “natural hierarchies”: The subject owed the emperor obedience. The son owed the father allegiance. The wife owed the husband obedience. The friend owed the friend respect.

The obligation to retain that allegiance in each case was that the father, husband, friend, etc. fulfilled their own obligation. If they did not, then there were not considered an emperor, father, friend and so on in the true sense of the word and the obligation was not complete.

In the example, we have discussed, the emperor had a set of attributes and rituals that he was to really be an emperor. Conscientiousness about fulfilling that role was essential to retain the mandate of heaven. In the case of the other various roles, conscientiousness of the obligations of the role was also vital. When individuals lived up to the name of their role (lived up to the obligations of being a good father, son, wife, friend, minister, etc.) then heaven was thought to be unified with earth.

Criticisms

Many Chinese, especially in the twentieth century, came to be critical of the Confucian system of government in different ways, but mainly for what we can see as its conservatism. Its emphasis of traditions and rituals meant it was somewhat backward looking. Though the Chinese had made many technological and scientific developments, the focus of the Confucian education system was on disciplines that are hermeneutic rather than scientific. The focus of education was all too often on interpreting what great men of the past had said rather than examining the world with modern science.

Other issues of contention included the rather hierarchical social order of the Confucian ethical system. In alignment with the Confucian system, children were to obey their parents, wives to obey their husbands, citizens to obey their political leaders. Individuals increasingly felt that this often lead to the unjust treatment of many. And it simply came to be thought that these characterization of natural roles (of women, for example) were simply incorrect.

Further after years of international subjugation of China to Western powers, various Chinese wondered if Confucianism was partially responsible because of its focus on obedience to those in power.

The Confucian dynasty system was finally ended in 1912. Under Mao and modernization, much has changed. Nonetheless, various elements of Confucianism are still present in Chinese culture, much like Christianity is in a now largely secular Europe …

December 31, 2018

Philosophical Pessimism

Arthur Schopenhauer, the quintessential philosophical pessimist

A thoughtful reader offered a rejoinder to the conclusion of my recent series on life and meaning. It advances an unequivocal pessimism in response to my (qualified) notions of optimism and hope. I repeat it here, edited slightly for brevity.

… We are in a desperate place since there is so much evidence that as Schopenhauer said it is suffering which is primary to existence and our pleasures are only momentary relief from ongoing suffering or strife which is always, like time, nipping at our heels.

However, I think an honest person must as you say admit the fact that there are too many unknowns to say with any certainty what is the ultimate truth of this matter and we don’t know what the end game looks like. However, we do, to the best of our awareness know what is happening now and in the past. With that in mind, I can no longer put your kind of hope near the top of my list of things to believe in. [Just a minor point. I don’t believe in hope, rather it describes a certain attitude and certain wishes that I have.] There is TOO much suffering for that and not very much to your hope that this all ends up with these horrible wrongs righted and all wounds healed and anguish soothed …

You say here it’s the best thing to hope for the good and work towards that in spite of anything to the contrary but what does that mean? … Most would feed the starving and hope they survive. I would say all that does is create more misery as a full belly plus free time creates more innocent babies to starve all over again. There’s plenty of evidence for that. IMO, and that of the tiny few brother and sister antinatalists, … our most fervent and beautiful hope would be the extinction of the human race and even beyond that the elimination of all life that has a nervous system that can feel pain. I cannot think of a more certain way to end suffering and if we are honest we must admit that suffering is a certainty, whereas a happy ending for all is just another hope against hope that has never yet materialized and we’ve been preaching it for a long long time. There is really no evidence for it and if we want to go with the odds we should … have mercy on all future generations by not forcing them into existence.

I do wish I had better things to say than this. I would love to believe that your hope is worth hoping and that the sufferings possibly caused by acting on that hope might be worth it in the end but I can’t do that. I know what suffering is like close up both physically and emotionally and a reality that has this much of it is likely not planning on being kind to us in that unknown end game. Too often humans have felt that the suffering of others is a price worth paying for the chance at a better future that they want to imagine. IMO that’s callus and non-compassionate. Most don’t take the time to really see what some of this suffering actually looks like. It’s easier to look away and hope and that’s almost always what happens. That’s why our newspapers never really show the body parts with graphic close-ups or the screams on TV and radio. We can’t take that and we’d be outraged if we were forced to, but someone is taking it right now. I’m sorry to say all this. I miss that hope you seem to still have a strong hold on. I had to give it up or let’s say put it way down near the bottom of my possibles list. That or feel like a fraud. You’re a very lucky guy. I hope you know that. Best of luck to everyone, we all need it.

I would like to thank my reader for his thoughts.

JGM

December 24, 2018

Buddhist Metaphyics, Epistmology and Ethics

Standing Buddha statue at the Tokyo National Museum

Standing Buddha statue at the Tokyo National Museum

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/02/...

Buddhist Metaphysics

While some strands of Buddhism have very thick metaphysics, there are some forms with an extremely pragmatic orientation and a general focus on practices. Buddhism rejects that there is an all-powerful, all-knowing creator God. Buddhist emancipation is in some forms tied up with devotion to Celestial Boddhistavas, enlightened saints who are thought to have the power to ease others’ karma, but various forms of Buddhism do not accept or focus on this. In particular contemporary forms of Zen Buddhism downplay the importance of such metaphysics. One of the best-known tales of the early encounters with the Buddha makes this pragmatic stance toward metaphysics especially clear.

The monk and the arrow

Once when the Buddha was visiting a sangha (monastery), after some time a monk, Malunkya, who had been practicing diligently with the Buddha became quite dissatisfied with the fact that the Buddha had left various metaphysical questions unanswered. Malunkya thought to himself that he would ask the Buddha these questions and if he was given satisfactory answers he would devote himself to further study; otherwise he would leave the sangha.

Meeting the Buddha, Malunkya then asked him his questions: Was the universe was finite or infinite? Were the body and soul one and the same or different? Would the Buddha exist after his death or not? Mulunkya further informed the Buddha that if he refused to answer the questions, he would leave the sangha. The Buddha responded, asking if he had ever asked Malunkya to join the sangha so that he could get the answers to those questions. Malunkya acknowledged he had not.

The Buddha continued, noting that Malunkya’s decision to leave the sangha for not having received the answers to those questions was similar to a man who had been shot by an arrow going to a doctor for help but then refusing to allow the doctor to help remove the arrow until he could answer many questions about the one who had shot the arrow: his caste, his clan name, his height, his skin color, the name of his hometown, what type of a bowstring he used, the shape and material of the arrow, the poison used. The man would die before receiving the answers to those questions. Similarly, a man wanting the answers to those metaphysical questions would die before the Buddha would answer them. One does not have to know whether the universe is eternal or not or the soul immortal, the Buddha emphasized. There is suffering, birth, aging, and death. The teaching is to alleviate the pain accompanying that.

Orthopraxy

For many contemporary Buddhist practitioners, this story provides a good example of the practical orientation of Buddhism. The focus of Buddhist philosophy is not on certain dogmas but on engaging in practices that change one’s behavior and mental attitude.

The eightfold path provides the set of practices that it is thought end cravings and, by so doing, eradicate suffering. In this tradition, like in Hinduism, meditation practices and ethical behavior should facilitate an understanding of the basic metaphysical truths. But for philosophical Buddhism, the three marks of existence are more fundamental metaphysical truths: impermanence, no-self, and suffering. These are viewed as rather common sense, even empirical psychological observations.

The various elements of the eightfold path work in cohort to create the necessary understanding of these, complimenting one another. Right understanding and right resolve focus on wisdom. Right speech, right action, right livelihood focus on morality. Right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation focus on meditation. Each element works together. By meditating, one breaks down the barriers of the ego and comes to be wiser, while also overcoming the wrong views that lead one to unethical behavior. The ethical behavior, for its part, can also increase one’s empathy and help one to cultivate a better understanding of the world.

All of these things facilitate a conscious living in the moment. From moment to moment what we then have is a mental focus on a particular sensation. We have one interconnected occurrence after another. In the moment, the division between the self and the world break down, as one, for example, breathes in air from outside oneself or exhales it into the world upon which one is codependent. As the zen practitioners especially emphasize, the point is to prevent one’s mind from wandering and focusing on the past or the future. It is to be present.

Instrumentalism/Constructivism

The approach that Buddhists tend to have to many metaphysical ideas … is instrumentalist. As a tendency, they are not epistemological realists but constructivists. Applied to metaphysical ideas such as reincarnation and karma, as well as Celestial Boddhisatvas, philosophical Buddhists tend to say that if those ideas serve useful purposes, then it is fine to use them. But if they do not, or if they have outworn their use, then one can set them aside.

One finds statements like this in Buddhist thinkers as diverse as D.T. Suzuki, who along with Alan Watts was influential in introducing an earlier generation of U.S. Americans and Europeans to Zen Buddhism, as well as the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh, two international leaders in Buddhism, who are influential in spreading Buddhist teaching to the West.

Given the doctrine of no-self, the self, as we tend to understand it cannot be viewed as having any kind of permanent existence. It instead is viewed as a construct. It is a useful convention to refer to the self. Indeed it would likely be impossible to live without doing so. And one can hardly talk of the three marks of existence without referencing some individual’s pain or using nouns that refer to stable things. Buddhists tend to adopt a pragmatic approach to these and other distinctions. Various such metaphysical ideas have their uses. But their usefulness does not mean they have any ultimate truth value.

Such constructivist pragmatism, especially about the difficult to answer questions of the gods, the afterlife, and so on, has proven attractive to many people in the U.S., Europe and elsewhere who have given up on traditional views of God but find some attraction to meditative or mindfulness practices of the Buddhist tradition, or of yoga from the Hindu tradition, which they view as improving their lives, providing them with some greater felt sense of interconnectedness with the world and others around them, or simply relieving stress and contributing to greater mental balance.

Sam Harris, who is well-known for his arguments against God’s existence, is one well-known public intellectual in the U.S. who has come out in support of Buddhist philosophical ideas and some practices. He, like various others, would like to separate this from the “religious” aspects of the tradition, as he understands those. But for him and many other American Buddhists, the constructivist pragmatism, at least about traditional metaphysical topics, is a great source of attraction.

Of the various religious systems, contemporary forms of Buddhism are probably the least heavily loaded with “requirements” for thick metaphysics. That said, most Buddhists practitioners do believe in karma, reincarnation. Many believe in celestial Boddhistavas. Pure land Buddhists believe in a Pure Land the people inhabit after death. They believe that some individuals can be reincarnated as gods or devils. In Tibetian forms of Buddhism, most believe in reincarnations of Llamas, who refuse the leave the cycle of life and death and are reborn to help lead others to emancipation …

Brief comments on ethics

Much more can be said about the ethics in these traditions. Here I have only emphasized how both Hindus and Buddhists generally believe that ethical practice is part of what helps cultivate the intuition into metaphysical truths. Similarly, they both think that the intellectual intuition that meditation cultivates should break down the boundaries of the ego so that, seeing one’s self as either linked with others in Brahman (in Hinduism) or as co-dependently arising (in Buddhism), one would not act selfishly but cooperatively. Buddhists in particular focus on the virtue of compassion. Both philosophical schools otherwise have multifaceted ethical systems beyond what can be explored here.

Other teachings in Indian Philosophy

… Indian philosophy (and science) has made contributions to multiple areas of human understanding. Amartya Sen, Harvard Professor of Philosophy and a Nobel Prize winner of economics, underlines in particular early views of the 4th century BCE Indian philosopher, Kautilya, who in Arthasastra cataloged all knowledge into four disciplines: 1) Metaphysics, 2) knowledge of right and wrong, 3) the science of government, and 4) the science of wealth. As an early thinker of economics as a mere technical field, Sen contrasts Kautilya with Aristotle, who subsumes thinking about economics under considerations of ethics. But it is Kautilya who may be the first full-fledged economist in world history; and he breaks our mold of Indians as religious thinkers.

So, too, though I have emphasized Advaita Vedanta, the best known of all religious schools of Hindu philosophy, in fact, some of the earliest known expressions of atheism, the view that there is no god, come from Indian philosophy. Of course, as we have seen, Buddhism rejects the idea of a creator god. But the Charvaka or Lokayata, beginning around the sixth century BCE, develop a decidedly less spiritual philosophy than Buddhists. They embraced a form of materialism that accepted that all things were comprised of four elements. They rejected the Vedas, a belief in gods and the afterlife. And they proposed a radical hedonism, thinking we should live for what increases our individual immediate pleasure. Even if pains sometimes arise from doing so, it is in their view, worth it.

The point is, Indian philosophers have done much more than I have been able to indicate in these general statements, where I have confined myself to issues of metaphysics as they intersect with epistemology and ethics and I have focussed in particular on the religious philosophies.

December 20, 2018

The Basics of Buddhism

Standing Buddha statue at the Tokyo National Museum

Standing Buddha statue at the Tokyo National Museum

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/08/31/...

Buddhist philosophy originates with Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha. The Buddha’s life itself weaves an interesting philosophic narrative. According to tradition, he was born the son of a king in the Magda empire of Ancient India or present-day Nepal. He was raised a prince but eventually turned away from the life of politics that his father had envisaged for him in order to pursue a life of spirituality. Specifically, according to legend, his father attempted to shield him from seeing the troubles of the world. But on various occasions, the young Siddhartha left the princely castle and escaped into the streets of the city where he saw those who were ill, who grew old, who died, and finally a monk. Seeing this suffering Siddhartha felt compelled to seek a spiritual life. He then left his home to join wandering mendicants and try to achieve spiritual enlightenment.

The sixth century was a tumultuous time, with many religious reformers who were dissatisfied with traditional Hinduism. Buddha, not himself a member of the priestly class or the Brahmin, joined these reformers, questioning the focus on the priestly class within Hinduism and more generally its strong caste system. In his search for enlightenment, Siddhartha initially engaged in strict asceticism, denying himself many of his bodily needs. But he is thought by adherents to eventually have achieved Enlightenment, after having long meditated under a Bodi tree.

The Middle Way

One of his first proclaimed truths was the importance of “the Middle Way,” which states that it is not the life of excess (such as he enjoyed as prince) nor the life of ascetic denial (which he attempted in his early spiritual search) that leads to enlightenment. Rather, it is the middle path that neither indulges nor denies basic human needs. Buddha presented some of his basic teachings in his first sermon, to monks with whom he had practiced asceticism but who were drawn to him after believing he achieved enlightenment. In that talk, known as the Deer Park Sermon, besides describing the Middle Way, Siddhartha (who now was given the honorific title of the Buddha, the awakened one) also presented his views of the four noble truths and the eightfold path, two of the most fundamental teachings of Buddhism, accepted by all Buddhist practitioners.

The four noble truths

The four noble truths outlined in this sermon are 1) that life is fundamentally characterized by suffering (dukkha); 2) that the cause of that suffering is attachment or craving (tanha); 3) that suffering can be overcome by the elimination of craving; and 4) that there is an eightfold path that makes it possible for us to eliminate this craving and thus eliminate suffering.

The eightfold path

This eightfold path consists of 1) right understanding; 2) right thought; 3) right speech; 4) right action; 5) right livelihood; 6) right effort; 7) right mindfulness; 8) right concentration. It is through the cultivation of a disciplined spiritual, ethical practice that one is relieved of attachment and one overcomes suffering. These various components of thought, behavior and concentration work in concert to allow individual liberation.

The three marks of existence

Metaphysically, Buddha also went a different path that his Hindu forebearers. While the Hindu thinkers emphasized the unity of all things in Brahman, a world substance that many of them thought to be permanent and unchanging, Buddha proposed a view of reality that continues to change and along with it a view of “no-self.” Where the Hindus focused on a unified “being” that encompassed all things, Buddha focussed on emptiness and non-being. All things, he emphasized, were in a state of constant change. The self, too, then is not “Atman” (Self, with a capital “S” or world soul) but “Anatman” (no-self).

As some Western philosophers have expressed this idea: If an object changes from moment A to moment B, then how can that object be characterized as the same object at those two times? Is it not rather two different ones? Buddha himself highlights how at any given moment the mind is aware of a sensation, a thought, a feeling, etc. These he views as “aggregates.” Where is the self behind all of these? The awareness we have is not of a self, but rather of one of these aggregates. With considerations like these, Buddha develops a considerably different metaphysics than one finds in the Hindu worldview that he grew up with. He speaks of three marks of existence that set his views apart from traditional Hindu thought: impermanence, no-self, and suffering.

Some common questions

Buddhism too raises numerous philosophical questions: For example, if the doctrine of the “no-self” is true, then what sense do moral commands to individuals have? Who is to carry them out? Who is responsible if there is no-self. And how are we to make sense of the goal of liberation or enlightenment if there is no self to be liberated or enlightened?

Buddhists, of course, have ways of addressing such concerns. Buddhists will, of course, acknowledge that as a practical matter, we will continue to refer to the self, use the words that reference the self, like “I,” “me,” “mine.” Yet this self is not thought to have ultimacy. This language, while needed for practical life, does not, for that, indicate that there is a permanent or separate self.

Co-dependent arising

This is tied to the Buddhist idea of “co-dependent arising.” That teaching, as we might express it in relationship to certain ecological ideas today, emphasizes the interconnection of all the conventionally understood self with an entire world. For example, though we might think of the boundaries of our skin as the boundaries of our self, in fact, we breathe in the air continually. We need the resources of water and food. Cut off from those things, the self disappears.

So, we might wonder, can we adequately consider the self as cut off from the world around it? Without the oxygen, produced by the plants, we will expire. Without water for several days, we also die. The self is tied into and co-dependent upon these other things. So we might think of those things too as only conventionally existent. For they, too are dependent on other things, which undergo change from moment to moment and do not retain a permanent existence. What we have, though, is always only the happening of each moment, itself continually undergoing change.

Some similarities between Hindu and Buddhist thought

In some general way, philosophers of the Hindu and the Buddhist traditions that we have discussed here display similarities. Both emphasize an interconnection between things. Yet, while Hindu philosophers speak of the individual self as part of a larger “Self,” a kind of Superorganism in which each individual is like a cell, Buddhists question that there is some overarching “Self.” They emphasize instead that all processes are undergoing change. They emphasize emptiness and nothingness rather than “Being.”

Yet other elements of these systems of thought are similar. Both traditions emphasize the need for adherence to a quite similar moral code and the need for a set of spiritual practices in order to achieve an intuitive awareness of metaphysical truths. They both generally accept the idea of reincarnation, and that the form of one’s reincarnation is dependent on how one has lived in previous lives — that is, they accept the reality of karma. Finally, they both accept the goal of enlightenment, even if they think that enlightened individuals understand the ultimate reality differently in these two traditions.

This conversation is only hinting at some of the philosophical issues at play in Hindu philosophy and Buddhism. Various concepts described here are also understood in other ways. And it is important to bear in mind that these worldviews are not static or uniform. In fact, we find various Hindu and Buddhist philosophers, all with subtle differences in how they understand their own traditions. These are rich thoughtful systems of thought, which each contain thinkers who debate issues with each other and with the traditional bodies of knowledge acknowledged by their traditions.

Some basic questions

Questions of course abound. Many of those posed when discussing Hinduism apply to Buddhism. Some of the following apply to both worldviews:

Why should we accept that there is anyone who can be fully enlightened and that enlightenment comes through a spiritual practice rather than analytical thinking?

If there is karma, why do so many good things happen to bad people and bad things happen to good people?

Is the evidence that this is somehow related to past lives in any way convincing, or does it function as an ideological foil?

Are these spiritual systems too focused on individual mental liberation and do they short social justice concerns?

Are these systems ultimately overly pessimistic? Is individual life so oppressive and disappointing that we ought desire to escape the cycle of existence?

Finally are basic elements of these systems of thought self-contradictory?

December 17, 2018

Hindu Metaphysics, Epistemology, and Ethics

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/02/...

Metaphysics of Advaita Vedanta

Metaphysics studies the type of things that exist and includes reflections on ultimate reality. In the presentation of ideas so far, the views of Brahman and the self in Hinduism and the marks of existence in Buddhism, as well as related discussions of the five aggregates are all part of the subject matter of metaphysics. Reincarnation and karma also can be included in this area of philosophy, as they concern processes to which existent things are subject.

The discussion of the self in Advaita Vedanta offered earlier was incomplete. So far, besides discussing the self as we normally understand it — a given individual, named Sarah, for example — we discussed Atman, the world soul of which Sarah would be an expression. Beyond that, however, the Hindus speak of self in a further sense called jiva. Jiva is an individual soul, separate from the world soul, but also not identical with a specific person. The jiva undergoes reincarnation, passing through various reincarnations as specific individuals until it achieves Moksa, the full awareness that ultimate reality is one unified whole. While Sarah is the individual in a particular lifetime, the jiva is the soul that transmigrates from one life to another. Sarah in this life may become Shiela in the next. A typical analogy is that of water which can be poured from one container to another, taking on the form of whatever container it is in.

So in one life, the water is in the form of a cup (Sarah), in another it takes the form of a pot (Shiela). Another analogy is that of a pillow and a pillowcase. The jiva is the pillow, in one life slipped in one pillowcase (Sarah), in another slipped into another one (Shiela). This is supposed to happen until jiva (non-named since it always takes on the name of its present incarnation) learns the lessons it should and awakens to the deep truth of the fundamental unity of everything through a practice of yoga. That knowledge is sufficient to end the cycle of births and rebirths. The individual soul at that point simply disappears again into the primordial unity of Brahman. To return to our water analogy, the water is then returned to the ocean, where it simply exists in unity, losing its individual features.

Epistemology in Advaita Vedanta and Beyond

One of the great difficulties with any of these religious-philosophical systems concerns how we are to know these difficult metaphysical truths — about the self and ultimate reality — that they expound.

Generally, we accept that we gain knowledge through reflection on our sense experience and logical deductions. But the spiritual systems propose metaphysical truths about which we have no sense experience. Generally, the religious systemizers will maintain that a type of internal sense, an internal sight, or insight, is possible that allows us to understand the metaphysical truths that are expounded. These Eastern systems, in particular, are less dogmatic than the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) tend to be.

Hinduism does have many sacred texts that are formative for all in the tradition, but it largely does not understand itself as a dogmatic belief system but as a living system. Gurus are thought to have the insights and to be able to guide others to have these as well. This requires the practice of various forms of yoga, which eventually should allow the insights among the practitioners. It is this kind of intuition that should lead individuals to accept the truth of the ideas of Brahman, Atman, reincarnation, and so on.

There are five general types of yoga: 1) Hatha yoga is the type of yoga most people are familiar with through yoga centers in the U.S. and Europe. In this form of yoga … one assumes asanas (or postures), engaging in physical practices that are to reform the mind, leading to Moksa. 2) Bhakti yoga is the yoga of devotion. 3) Karma yoga is the yoga of service. 4) Raja yoga is the yoga of meditation. 5) Jnana yoga is the yoga of theoretical learning.

In Hinduism, the practice of these forms of yoga is related both to epistemology and ethics. Each of these practices should lead individuals to understand their ultimate unity with one another in Atman and Brahman. Knowing this, these individuals will also lose the egoism that drives selfish and immoral behavior. So, it is such practices, along with the adherence to a moral regime, that lead to insight about metaphysical truths.

Of course, it has to be acknowledged that only very few individuals will indeed have had such deep insight. But in the most charitable reading, one might note that few understand relativity theory or string theory either. But the assumption accepted is that with enough work they would be able to understand it. In these religious systems, the vast majority have some faith that they could, one day with enough practice, understand the truths that they now largely accept on faith.

Should we trust our cultivated inner perception?

A problem with such arguments about an inner perception is that there seems to be little agreement among those who maintain they have one (whether in the Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, Muslim or other traditions). Most of these worldviews maintain that some such insight is available, at least to some. Yet the fundamental descriptions of the metaphysical reality across these traditions are not in agreement, unlike the descriptions of relativity theorists, for example, in diverse places such as China, Germany, the U.S. and so on.

Reincarnation is also a process that practitioners of these Eastern systems maintain one might also have an inner perception of. Deja vu experiences, dreams, and the like are the general reports used in support of veracity of such views. The question for those considering such views is whether those experiences are best explained as indicating the reality of reincarnation and as lending sometimes support for the mechanism of karma, or whether some other explanation might be more compelling.

Indeed, given the lack of agreement among the various religious systems in the world about what that inner perception is — regarding views of God, the self, the afterlife — how reliable of a guide is it? …

December 13, 2018

The Basics of Hinduism

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2018/09/02/hindu-and-buddhist-thought-2/

The German philosopher Karl Jaspers has characterized the period of the 6th to the 2nd century BCE (before the common era) as the Axial Age. This is a period of the establishment and flourishing of new worldviews that began to replace the polytheistic religious views that were dominant before that time. Many significant figures for the development of worldviews that were determinant for two thousand years lived at this time. In Greece, we see the early natural philosophers, as well as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle (who for their part go on, along with the Old Testament prophets of this period, to strongly affect Christianity). In India, we see the formulation of the philosophical ideas in the Bhagavad Gita that serve as the foundation for the later developed Advaita Vedanta. We also see Buddha challenge the Hindu ideas that he inherited. In China, Loazi (the founder of Taoism) and Confucius (the founder of Confucianism) begin to develop their philosophical systems …

Advaita Vedanta

… Here we will only survey some basic ideas of the school of Indian philosophy known as Advaita Vedanta. This philosophical school was developed by the philosopher Shankara in the eighth century of the common era. Yet it draws on ideas in the Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita, sacred texts within the Hindu tradition, the latter of which was developed in the Axial Age. Advaita Vedanta is particularly important for its clear expression of pantheism, the idea that there is one thing and that thing is God. Hindus view everything in the world as ultimately an expression of one underlying godhead.

While the main forms of Hinduism are pantheistic, Hinduism generally also accepts that one can speak of a plurality of gods. Hinduism generally acknowledges hundreds of thousands, or some say even millions, of gods. Yet the entire Hindu pantheon can all be viewed as expressions of the same underlying godhead, Brahman. Hindus believe that one can worship any of them as a vehicle for Moksa, or enlightenment. Brahman can work through the varying guises.

Given that Hinduism generally accepts that one can worship any of the various manifestations of the Godhead, Hinduism is also known as henotheism. Henotheism identifies all particular deities ultimately with one ultimate reality and accepts that one may worship whichever manifestation one wants. As a rule, the proponents of Advaita Vedanta focus on seeing this philosophically, however, and emphasize Brahman.

While this is already complicated, in fact, the discussion of ultimate reality in Advaita Vedanta is more complicated still: Just as that pantheon can be identified with the one Godhead, Brahman, so all different people and things in the world can ultimately be viewed as expressions of a single world soul, known as Atman. This world soul is the true Self underlying many apparently separate visages of individuals. So you and I and all others are actually expressions of this world-soul comparable to how the manifold gods are really expressions of one basic godhead, Brahman.

Ultimately, in fact, yoga (in any of its multiple forms that allow a binding of the individual to the Godhead) will unveil that Brahman and Atman are also really unified. In other words, those forms identified with transcendent Brahman (the pantheon of gods) and the individuals of the world (viewed as expressions of Atman) are themselves really one thing. This too is called Brahman. Rightly understood, the transcendent and the immanent aspects of the Godhead are seen as unified: Brahman and Atman are the self-same. Advaita Vedanta also … has well-known views about the soul and its possible reincarnation and posits laws that control the transmigration of the soul–karma. These ideas will be expanded on later, as we also consider philosophical conundrums of pantheism.

One of the most serious questions involves ethics: For example, if all individuals are really an expression of the one Godhead, of Brahman, then what ultimate importance do moral ideas possess? If they slayer and the slain are one and the same, as is famously said in the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads, then how do we really make sense of moral command not to kill? (Shankara’s commentary on some of the Upanishads can be found online.)

Other questions concern what evidence is really sufficient for showing that there really is only one substance, Brahman and that our sense of individual existent entities is ultimately illusory? What evidence, too, is strong enough that we might believe that there is a soul and that reincarnation really occurs? Other questions of the afterlife also present themselves: Sri Aurobindo, a premier Indian philosopher of the 20th century and the developer of Integral Yoga, has asked what real consolation a belief in reincarnation provides for individuals given that it is not the individual self as we normally understand it who is reincarnated. If a man named John in one life is reincarnated as Leslie in a future life, there is in some sense no more John. Leslie will not generally have memories of having been John. John’s body will not exist, etc.

Of course, the discussion here of this as “Hindu philosophy” is oversimplified. There are minority positions within Hindu philosophy, like the Dvaita Vedanta, that are not monistic, such as the Advaita Vedanta I have discussed here. Proponents of Dvaita Vedanta are dualists who maintain that in fact the Godhead, the world, and the individuals in the world exist as separate substances. They focus also on the personal worship of Vishnu.