John G. Messerly's Blog, page 67

July 26, 2018

Why Do Conservatives Tolerate Trump?

© Darrell Arnold– (Reprinted with Permission)

http://darrellarnold.com/2018/07/25/t...

Oh, the times they have a’ changed, but not for the good. As Jonathon Freedland has noted in an opinion piece in the Guardian, the recording released in late July by Donald Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen, speaking to Trump about the need to pay hush money to Karen McDougal, would have likely been enough to undo any recent presidency, including Clinton’s. It implicates the president not only in the sordid affair but in possible campaign finance breeches. Yet, the fact is that hardcore Trump supporters are simply unswayed by traditional moral argument. The “moral realm” they inhabit is one in which any act by Trump, however brazen, is justifiable as long as it keeps Democrats out of office — because the greatest moral threat to the country, in their view, comes not from the daily lies, the sexually predatory behavior or even the threat to our global political alliances of the president but from Democratic policies.

Some of them see this great threat to consist in the Democratic Party’s cultural policies, which support gay marriage and abortion, promote equal pay for women, and support diversity in education and the workplace and a more generous immigration policy. Each of these policies is thought to threaten traditional ways of life.

But the hostility extends toward social programs to alleviate the poor, to provide medical care for all, to increase debt relief for students, and to regulate corporations. Insofar as these are connected with tax increases, much of Trump’s base rejects them — even if those tax increases are only for the wealthiest Americans. In the positive light in which Trump supporters see this, their own policy choices reflect the value of self-reliance. Everyone is to take care of themselves. Policies that require solidarity are to be rejected — even if when we look around the world we see that they pay off in higher life expectancies, greater literacy rates, lower infant mortality rates and a host of other quality of life issues.

Much of this is tied to a hyper-masculinity. The cultural policies outlined threaten the dominance of white males in America. The fiscal policies noted require empathy and point to a sense of community responsibility, both of which are rejected by the hyper-masculine, who live in a world where each takes care of himself, and there is no acknowledgement of the social character of the self, but an illusion is cultivated that each of us is self-made, not a product of our own decisions against the backdrop of cultural and social forces that were not of our choosing.

So Trump can do what he wills. He will suffer no repercussions from his staunch base because that base has a quasi-religious ideological entrenchment. When it comes down to it, many of them will chalk up the political dispute to cultural values. Of primary importance to many of them is a cultural war, in which they see themselves as the preserver of traditional values and, as startlingly mad as it may seem, view Trump as the champion of these values. Because Trump at times talks with respect about traditions they value (even while invoking prejudice and sexism), is willing to make promises about them that he cannot keep and fights against a world that makes his base feel uneasy, his greatest sins are forgivable. The Democrats, by contrast, threaten Trump’s base with an openness to new cultural mores and with the support of policies that require, as Obama put it, quoting scripture, that we acknowledge that we are each our brothers (and sisters) keeper.

It does not appear that this will change. In fact, the more frightened the Trump supporters become, and the more who join them in the fear, the less open these voters will be to policies that reflect openness and challenge us to social solidarity.

For now, we find ourselves in a strange, topsy-turvy world where a base strongly supports the least moral president in our lifetime at least in part for reasons that many of them find morally imperative.

July 23, 2018

Review of Timothy Snyder’s, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century

[image error][image error]

© Darrell Arnold– (Reprinted with Permission)

http://darrellarnold.com/2018/07/16/o...

In bite-sized chunks of two to eight (short) pages Timothy Snyder, the Levin Professor of History at Yale University, offers a practical guide to understanding and possibly averting tyranny. [In his new book, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century.]

At 126 pages, this small paperback is a great, quick read that offers lessons Snyder has accumulated over years of studying tyrannies around the world. His advice, accompanied by anecdotal stories from authoritarian regimes in twenty chapters, includes: Defend institutions, Remember Professional ethics, Believe in truth, Establish a private life, Be a patriot.

[image error]

In Chapter 4, “Take responsibility for the face of the world,” Snyder asserts that “life is political”: “the minor choices we make are themselves a kind of vote” (33). In everyday life, then, we should be attentive to our effect on the social and political world around us. In Hitler’s Germany, for example, small delinquencies in the everyday cascaded into increasingly larger ones: those who were able to be stamped as “pigs” were easier to later boycott because they were Jewish; and they were so much the easier to target more egregiously later. After first dehumanizing them in speech and with symbols, it was later possible to completely dominate them.

In Chapter five, “Remember professional ethics,” Snyder mentions both how legal and medical professionals came to the service of the Nazi regime. Professional lawyers helped twist the law to the Nazi’s perverse ends. Medical professionals proved quite willing to participate in ungodly experiments with Jews to advance medical knowledge. Collectives of professionals who are committed to the ethical codes of their professions can offer some resistance to dehumanizing practices supported by a government. As Snyder notes: “Professional ethics must guide us precisely when we are told that the situation is exceptional” (41).

In Chapter eight, “Stand Out,” Snyder reminds us of great individuals throughout history, like Rosa Parks, who were not afraid to stand out and follow their consciences in the face of opposing political forces and who set positive examples for the struggle against domination. In various historical examples, we see it is all too easy to accommodate those who dominate. However, Winston Churchill in 1940 was another counter-example, as he entered into war to help Poland, which was largely seen by many others as a lost cause. As Snyder writes: “he himself helped the British to define themselves as a proud people who would calmly resist evil…. Churchill did what others had not done. Rather than concede in advance, he forced Hitler to change his plans” (54ff.).

Chapter 10, entitled “Believe in Truth,” begins with the prescient statement: “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights” (65). Once truth is disarmed, and people simply reject it as the adjudicating criteria for belief, politics can quickly descend into spectacle. Hostility toward verification dominates. “Shamanistic incantations,” which Victor Klemperer described as “endless repetition” of some key phrases, takes over: Think of “lock her up” or “Build that wall.” Magical thinking also comes to dominate, accompanying the confused view that one particular political leader alone can solve the nation’s ills. As in the German example, people come to accept that one just needs faith in the “Fuehrer.” Our post-truth culture increases our vulnerability to this. In Snyder’s words: “Post-truth is pre-fascism” (71)

To break the spell of magical thinking and incantation, it is important to “investigate” (Chapter 11). Clearly, much of the information that we encounter every day is false. Some of it is purposefully meant to sew confusion. So it is important to learn to think critically about sources of information and to pursue a correct understanding of the world. As Vaclav Havel had written, “If the main pillar of the system is living a lie, then it is not surprising that the fundamental threat to it is living in truth” (78).

In “Practice corporal politics” and “Establish a private life” (Chapters 13 and 14), Snyder highlights the need for contact with people in one’s private life, partially in civil society (churches, clubs, organizations). Since “tyrants seek the hook on which to hang you,” he also advises “try not to have hooks.” Secure private information, for example, on your computer. But also publicly we can join groups that preserve human rights (91). This is related to Chapter 15, “Contribute to good causes”: The contribution can be in time or money, but it is a form of active engagement in shaping the world in accord with our own values and views.

In Chapter 16, “Learn from peers in other countries,” Snyder urges us to not only learn from others but to make friends with those in other countries. And in case the tyranny comes, “Make sure you and your family have passports” (95).

In “Be Calm When the Unthinkable Comes,” Chapter 18, we are urged to consider that demagogues often exploit crises to implement Martial law. In the search for safety, it is precisely in times of crisis that people are often more willing to compromise civil liberties and to allow changes in the constitutional order. Realize this, and counter it if it begins to occur. Understand the difference between patriotism and nationalism. In “Be Patriotic,” Chapter 19, Snyder encourages us to serve the ideals of our rights-based democracy, not to be victims of an authoritarian politics carried out by nationalists who are often completely out of sync with the ideals of the nation. Chapter 20 enjoins “Be as courageous as you can”: “If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny” (115).

Snyder finishes the book with a short epilogue contrasting two views of politics that he views as anti-historical, the “politics of inevitability” with the “politics of eternity.” Inevitability politicians work with a teleological view of history in which the course of history is maintained to be known in advance. It is anti-historical insofar as such a view presumes that there is no real freedom to escape the final end of history. Eternity politicians are anti-historical in another way. They focus on a past, but as an ideal type, not one comprised of real facts. So, eternity politicians refer to the soul of a country, pure, and often under siege by external forces. In contrast, Snyder sees what we might call a politics of freedom under which “history permits us to be responsible: not for everything, but for something” (125).

This typology is developed further in Snyder’s “The Road to Unfreedom.” Regardless of whether one finds the typology ultimately compelling or accepts Snyder’s apparent moderate liberalism, one may still admire Snyder’s attempt to highlight the importance of human freedom. Those attracted to Snyder’s book, which I hope will be many, are likely to agree with his appeals that we ought to “begin to make history” (126). Otherwise, various authoritarians surely will do it for us.

Since Snyder wrote his book, the possibilities of an increase in authoritarianism, unfortunately, do not appear to be abating. Rather, there increasingly appear to be very good reasons to heed Snyder’s practical suggestions for a politics of resistance.

July 20, 2018

Fox News: An Information Ecosystem For Fallicious Reasoning

By Darrell Arnold, Ph.D. – http://darrellarnold.com/2018/07/16/f... (Reprinted with Permission)

Fox news has long functioned in the service of America’s conservative movement. What is particularly concerning is their willingness to do so even if it undermines truth and sound reasoning. One way that it regularly undermines truth and clear reasoning is through subtext in the framing of their stories. Another is through editorial decisions on what stories to feature — not the framing of their stories but their framing of their news environment. This creates a kind of informational ecosystem that facilitates fallacious reasoning for ideological purposes. As an example of this latter issue, on their webpage on the day of the Helsinki Summit, after many hours they finally featured a story about “bipartisan backlash.” Yet one of their other featured stories of the day was about — you guessed it — Hillary and Bill Clinton. The day’s lead story thus dealt with the issue of the day. The other though didn’t but served as a reminder for the Fox viewer of all the “Clinton scandals.”

Fox’s decisions in this instance, like on so many others, borders on serving as propaganda, and the informational ecosystem they create facilitates fallacious reasoning in service to their ideological agenda. By selective editorial placement a modern media company like Fox will not exactly commit the Tu Quoque fallacy, sometimes known as Whataboutism (though they do this often in enough of their commentary) — but it can certainly facilitate it among its audience, or create an environment for it.

Whataboutism is a version of the Tu Quoque fallacy. Tu Quoque means “you too” or “who’s talking?” The fallacy in its various forms functions as a diversion, directing people’s attention away from the issue under discussion by focusing on how those making a particular accusation are themselves guilty of the same kind of thing they are accusing others of. Whataboutism in a context of a political scandal will often draw attention away from a scandal by pointing out that an opposing political party also has committed scandals that are just as bad or worse.

In our given example, on the one hand, we have an extraordinarily serious scandal of a sitting U.S. president undermining his own intelligence agencies and the preceding U.S. administration, with no apparent reason other than the fact that Vladimir Putin very strongly protested the charges. Indeed, the event was serious enough that Senator John McCain called it “one of the most disgraceful performances of an American president in memory.” John Brennan, former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, said “Donald Trump’s press conference … rises to and exceeds the threshold of ‘high crimes and misdemeanors.’” Various Democrats also clearly condemned the president’s actions at the summit.

The bipartisan reaction to Trump’s performance is highlighted in the main story of the news of the day. On the other hand, we have the “scandals” about the Clintons, which have been thoroughly investigated but already dismissed. In the case of the Hillary “scandals,” for example, the Benghazi Affair was Congress’s longest investigation, costing over 7 million dollars. The Email controversy was investigated by various bodies over numerous years. In both cases, no criminal wrongdoing was found. But a new story about the Clintons is placed a story or two under the lead story of the day. So we have the Trump issue presented, but the Fox audience is at the same time presented with the question: What about Hillary? What about the Clintons?

Fox is facilitating the Whataboutism fallacy as it subtly suggests a false equivalency between a very real scandal of the day and a trumped up one. This is something they have done regularly over the years and continue to this day, bringing up both of Hillary’s controversies on a regular basis. Through their editorial decisions about what stories to feature and highlight (and to run regardless of credibility) and then by decisions about how to place these in proximity to other stories, media companies and information providers like Fox can serve the purpose of facilitating fallacious reasoning, and in the case of Fox to do so for reasons of ideology. Though this observation here focuses on one story, an observer of Fox will easily find that this is going on regularly. Add to it the regular commentary of certain media figures and the regularity with which it brings up stories with little credibility at all, and we can see that Fox in particular is essentially an information ecosystem that continually nudges toward fallacious reasoning for ideological purposes. It has long been doing this at the service of the Republican’s moves to undermine democratic norms. Now it is apparently pleased to assume the role in support of an administration with clear authoritarian characteristics.

July 16, 2018

Finding Work That You Love

Steve Jobs, in his 2005 commencement speech at Stanford, argued that we should do the work we love. Here is an excerpt of his main idea:

You’ve got to find what you love. And that is as true for your work as it is for your lovers. Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle…

In the past few days I have encountered four separate articles concerning the question of whether one should (only) do the work they love. Each piece had Jobs’ claims in mind.

In “A Life Beyond Do What You Love,” philosophy professor Gordon Marino argues that doing what we don’t want to do—doing our duty—is more noble and ethical than just doing what we love. He doesn’t take kindly to the physician who quit his practice to skateboard all day. In, “In the Name of Love,” the historian Miya Tokumitsu says that the “do what you love” ethos is elitist and degrades work not done from personal passion. It neglects that work may develop our talents, be part of our duty, or be necessary for our survival. The socio-economic elite advance the do what you love view, forgetting their lives dependonn others doing supposedly less meaningful work. In, “Never Settle is a Brag,” the economist and futurist Robin Hanson critiques Jobs’ advice that we shouldn’t settle for unfulfilling work. If everyone followed Jobs’ counsel a lot of needed work would go undone. Note too that the advice works best for the talented, so by advising others to not settle for anything less than work they love, you signal your status. You are bragging. Finally in “Is Do What You Love Elitist?” philosophical blogger Mark Linsenmayer recognizes the flaws in Jobs’ prescriptions but finds in them an obvious truth too—the good life requires that we not be wage slaves in a market economic system. Thus we should change the system so that work can be more satisfying.

I agree with Marino that doing our duty, even if it doesn’t make us happy, is admirable. And I agree with Tokumitsu and Hanson that elitists, who often do the most interesting work, fail to value more mundane work. But I think that Linsenmayer makes the most important point. We need a new economic system—one where we can develop our talents and actualize our potential. Most of us are too good for the work we do, not because we are better than others, but because the work available in our current system is not good enough for any of us—it is often not satisfying. (I have written about this previously.) As Marx wrote almost two hundred years ago, most of us are alienated from the work we do, and thus ultimately alienated from ourselves and other people too.

Still we do not live in an ideal world. So what practical counsel do we give people, in our current time and place, regarding work? Unfortunately my advice is dull and unremarkable, like so much of the available work. For now the best recommendation is something like: do the least objectionable/most satisfying work available given your options. That we can’t say more reveals the gap between the real and the ideal, which is itself symptomatic of a flawed society. Perhaps working to change the world so that people can engage in satisfying work is the most meaningful work of all.

July 12, 2018

The Impossibility of Mind Uploading

My most recent post, “Living in a Computer Simulation,” elicited some insightful comments from a reader skeptical of the possibility of mind uploading. Here is his argument with my own brief response to it below.

My comment concerns a reductive physicalist theory of the mind, which is the view that all mental states and properties of the mind will eventually be explained by scientific accounts of physiological processes and states … Basically, my argument is that for this view of the mind, mind uploading into a computer is completely impractical due to accumulation of errors.

In order to replicate the functioning of a “specific” human mind within a computer, one needs to replicate the functioning of all parts of that specific brain within the computer. [In fact, the whole human body needs to be represented because the mind is a product of all sensations of all parts of the body coalescing within the brain. But, for the sake of argument, let’s just consider replicating only the brain.] In order to represent a specific human brain in the computer, each neuron in the brain would need a digital or analog representation, instantiated in hardware, software or a combination of the two. Unless this representation is an exact biological copy (clone), it will have some inherent “error” associated with it. So, let’s do a sort of “error analysis” (admittedly non-rigorous).

Suppose that the initial conditions of the mind being uploaded are implanted in the computer with no errors (which is highly unlikely in its own right). When the computer executes its simulation, it starts with that initial condition and then “marches in time”. The action potential duration for a single firing of a neuron is on the order of one millisecond, which implies that the computer time step would need to be no larger than that (and probably much smaller or else additional computational errors are induced). So the computer would be recalculating the state of the brain at least 1,000 times per second as it marches in time (and probably more like 10,000 times per second).

Since the computer representation of the brain is not perfect, errors will accumulate. For example, suppose that the computer representation of one neuron was only 90% accurate. After that neuron “fired”, its interaction with connected neurons would have roughly a 10% error. Now consider that the human brain has roughly 86 billion neurons, each with multiple connections to other neurons. The computer does not know which of those 86 billion neurons are needed at each time step, so all would need to be included in each calculation. One can see that 10% errors in the functioning of individual neurons within the millisecond duration will quickly accumulate to produce a completely erroneous representation of the functioning of the brain a short time after the computer started its simulation. The resulting “mind” that gets created in that computer would probably bear no similarity to the original human mind (or to probably any “human” mind). It would probably be “fuzzy” and unable to function.

Would 99% accuracy in the representation of a neuron be any better? Not really. 99.9% accuracy? Still no good. 86 billion neurons is a large number (and remember, the computer is recalculating the entire brain state 1,000 to 10,000 times per second). In order for accumulated errors to not overwhelm the simulation of the brain in the computer, the accuracy in representing each neuron would need to be extremely high and the amount of information needing to be stored for each of the 86 billion neurons would be huge, leading to an impractical data storage and retrieval problem. The only practical “computer” would be a biological clone, which is not the topic here.

Consequently, if one believes in a reductive physicalist theory of the mind, then uploading the specific mind of an individual human into a computer is, for all intents and purposes, impossible.

My Response

Let me say briefly that I wouldn’t call mind uploading impossible, as many experts (Ray Kurzweil, Marvin Minsky, Randal A. Koene, Nick Bostrom, Michio Kaku, and others) attest to its possibility. And even skeptics like Kenneth Miller don’t reject the idea in principle. My view is that, with enough time for future innovation, something like it is almost inevitable. Of course we may not have that time.

July 9, 2018

Living In A Computer Simulation

Many scientists believe that we will soon be able to preserve our consciousness indefinitely. There are a number of scenarios by which this might be accomplished, but so-called mind uploading is one of the most prominent. Mind uploading refers to a hypothetical process of copying the contents of a consciousness from a brain to a computational device. This could be done by copying and transferring these contents into a computer, or by piecemeal replacement with parts of the brain gradually replaced by hardware. Either way, consciousness would no longer be running on a biological brain.

I am in no position to judge the feasibility of mind uploading; experts have both praised and pilloried its viability. Nor can I judge what it would be like to live in a virtual reality, given that I don’t even know what it’s like to be a dog or another person. And I don’t know if I would have subjective experiences inside a computer, in fact, we don’t know how the brain gives rise to subjective experiences. So I certainly don’t know what it would be like to exist as a simulated mind inside a computer or a robotic body. What I do know is that the Oxford philosopher and futurist Nick Bostrom has argued that there is a good chance that we live in a simulation now. And if he’s right, then you are having subjective experiences inside a computer simulation as you read this.

But does it make sense to think a mind program could run on something other than a brain? Isn’t subjective consciousness rooted in the biological brain? Yes, for the moment our mental software runs on the brain’s hardware. But there is no necessary reason that this has to be the case. If I told you a hundred years ago that some integrated silicon circuits will come to play chess better than grandmasters, model future climate change, recognize faces and voices, and solve famous mathematical problems, you would be astonished. Today you might reply, “but computers still can’t feel emotions or taste a strawberry.” And you are right they can’t—for now. But what about a thousand years from now? What about ten thousand or a million years from now? Do you really think that in a million years the best minds will run on carbon-based brains?

If you still find it astounding that minds could run on silicon chips, consider how absolutely remarkable it is that our minds run on meat! Imagine beings from another planet with cybernetic brains discovering that human brains are made of meat. That we are conscious and communicate by means of our meat brains. They would be amazed. They would find this as implausible as many of us do the idea that minds could run on silicon.

The key to understanding how mental software can run on non-biological hardware is to think of mental states not in terms of physical implementation but in terms of functions. Consider for example that one of the functions of the pancreas is to produce insulin which maintains the balance of sugar and salt in the body. It is easy to see that something else could perform this function, say a mechanical or silicon pancreas. Or consider an hourglass or an atomic clock. The function of both is to keep time yet they do this quite differently.

Analogously, if mental states are identified by their functional role then they too could be realized on other substrates, as long as the system performs the appropriate functions. In fact, once you have jettisoned the idea that your mind is a ghostly soul or a mysterious, impenetrable, non-physical substance, it is relatively easy to see that your mind program could run on something besides a brain. It is certainly easy enough to imagine self-conscious computers or intelligent aliens whose minds run on something other than biological brains. Now there’s no way for us to know what it would be like to exist without a brain and body, but there’s no convincing reason to think one couldn’t have subjective experiences without physicality. Perhaps our experiences would be even richer without a brain and body.

We have so far ignored important philosophical questions like whether the consciousness transferred is you or just a copy of you. But I doubt that such existential worries will stop people from using technology to preserve their consciousness when oblivion is the alternative. We are changing every moment and few worry that we are only a copy of ourselves from ten years ago. We wake up every day as little more than a copy of what we were yesterday and few fret about that.

Perhaps an even more pressing concern is what one does inside a simulated reality for an indefinitely long time. This is the question recently raised by the Princeton neuroscientist Michael Graziano. He argues that the question is not whether we will be able to upload our brains into a computer—he says we will—but what will we do afterward.

I suppose that some may get bored with eons of time and prefer annihilation. Some would get bored with the heaven they say they desire. Some are bored now. So who wants to extend their consciousness so that they can love better and know more? Who wants to live long enough to have experiences that surpass our current ones in unimaginable ways? The answer is … many of us do. Many of us aren’t bored so easily. And if we get bored we can always delete the program.

July 3, 2018

Is Evolution True? Yes, and the World is Round Too

“As a rule we disbelieve all the facts and theories for which we have no use.” ~ William James

I rarely reply to a comment of a previous post. One reason is that, as 30 years of being a professor has demonstrated, you rarely change people’s minds. And I am just too old to enter into many polemics. But I may have been misunderstood. So to clarify the position of my previous post, I’ll reply to this comment.

“In view of the fact that you mention the germ theory of disease, its interesting to note that Ernst Boris Chain the co-winner of the Nobel prize for his work in refining and perfecting penicillin, which has probably saved over 200 million lives, believed in God and thought Darwinism was no more than a fairy tale.“

The reader is correct that there are theistic scientists, a self-evident claim that no rational person would deny. In fact, this blog and my recent book document that 7% of the members of the national academy of science members are theists. Of course the evidence also meticulously shows that religious belief declines with educational attainment, among other factors. Now, this doesn’t mean that religious belief is false, but it does suggest that religion is not best defended by appealing to the frequency of religious belief among scientists, for religious belief among that cohort is considerably less than in virtually any other group. Other arguments are better suited to a defense of religion.

As for the fact that an individual scientist rejects the near-unanimous opinion of other scientists, this is hardly surprising. There are hundreds of thousands of scientists in USA—more than ten million if you count all those employed with science and engineering degrees—so it is easy to find outliers. You can find a (very) few scientists who believe in Bigfoot or alien abductions too. That doesn’t change the fact that evolution has the same scientific status as the theory of gravity or the atom, a claim easily verified at the National Academy of Science website or any of hundreds of legitimate scientific websites listed below.

The consensus of belief in biological evolution is based on the overwhelming evidence from multiple sciences including: physics, chemistry, biochemistry, genetics, molecular biology, cell biology, population biology, ornithology, herpetology, paleontology, geology, zoology, botany, comparative anatomy, population ecology, anthropology and more. Anyone who tells you they don’t believe in evolution is either lying or scientifically illiterate. There is no other possibility. Remember that when you get a flu shot each year or finish your antibiotics, you’re implicitly accepting evolution—viruses and bacteria evolve quickly.

Still, it is possible that the outliers are correct. Maybe what goes up doesn’t come back down, perhaps the earth is flat or things don’t change over time—perhaps the gods deceive us about all of this to test our faith. But I wouldn’t bet on it! Finding outliers is simple confirmation bias—finding cases to confirm what one already believes.

Yet I have no illusions that anything I say will change people’s mind. I learned long ago that people don’t want to know, they want to believe. Interestingly, credulity itself has evolutionary origins. We are wired to believe what our parents tell us—it helped us survive—hence we often believe in adulthood what we were told when we were young.

For those interested in the truth about the fact of evolution you can visit any of these links.

Alabama Academy of Science

American Anthropological Association (1980)

American Anthropological Association (2000)

American Association for the Advancement of Science (1923)

American Association for the Advancement of Science (1972)

American Association for the Advancement of Science (1982)

American Association for the Advancement of Science (2002)

American Association for the Advancement of Science Commission on Science Education

American Association of Physical Anthropologists

American Astronomical Society

American Astronomical Society (2000)

American Astronomical Society (2005)

American Chemical Society (1981)

American Chemical Society (2005)

American Geological Institute

American Geophysical Union (1981)

American Geophysical Union (2003)

American Institute of Biological Sciences

American Physical Society

American Psychological Association (1982)

American Psychological Association (2007)

American Society for Microbiology (2006)

American Society of Biological Chemists

American Society of Parasitologists

American Sociological Association

Association for Women Geoscientists

Association of Southeastern Biologists

Australian Academy of Science

Biophysical Society

Botanical Society of America

California Academy of Sciences

Committee for the Anthropology of Science, Technology, and Computing

Ecological Society of America

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology

Genetics Society of America

Geological Society of America (1983)

Geological Society of America (2001)

Geological Society of Australia

Georgia Academy of Science (1980)

Georgia Academy of Science (1982)

Georgia Academy of Science (2003)

History of Science Society

Idaho Scientists for Quality Science Education

InterAcademy Panel

Iowa Academy of Science (1981)

Iowa Academy of Science (1986)

Iowa Academy of Science (2000)

Kansas Academy of Science

Kentucky Academy of Science

Kentucky Paleontological Society

Louisiana Academy of Sciences (1982)

Louisiana Academy of Sciences (2006)

National Academy of Sciences (1972)

National Academy of Sciences (1984)

National Academy of Sciences (2007)

New Mexico Academy of Science

New Orleans Geological Society

New York Academy of Sciences

North American Benthological Society

North Carolina Academy of Science (1982)

North Carolina Academy of Science (1997)

Ohio Academy of Science

Ohio Math and Science Coalition

Pennsylvania Academy of Science

Pennsylvania Council of Professional Geologists

Philosophy of Science Association

Research!America

Royal Astronomical Society of Canada — Ottawa Centre

Royal Society

Royal Society of Canada

Royal Society of Canada, Academy of Science

Sigma Xi, Louisiana State University Chapter

Society for Amateur Scientists

Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology

Society for Neuroscience

Society for Organic Petrology

Society for the Study of Evolution

Society of Physics Students

Society of Systematic Biologists

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (1986)

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (1994)

Southern Anthropological Society

Tallahassee Scientific Society

Tennessee Darwin Coalition

The Paleontological Society

Virginia Academy of Science

West Virginia Academy of Science

I’m sure you could find many others … if you are really interested in the truth.

June 29, 2018

Ignoring Politics

The political situation in the US is so depressing I often have to focus on something else. Was I to absorb all the dishonesty, hypocrisy, ignorance and cruelty that permeates the current administration and the Republican party … I would be consumed in misery. Was I to swallow all the psychic waste they flush into the world whenever they speak and act, my being would be contaminated. And that helps no one.

So I shop for groceries, exercise and enjoy my family. I’m more of a spectator than a participant in politics. I do what I can; I try to inform people on my blog. But an individual’s efforts are minuscule in the big scheme of things.

And I really don’t see the political situation ending well—the civil war will increase and may even lead to substantial violence. The fascism I warned of is here. Of course, by many measures, the world is better than ever: ( see for example Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress[image error], and The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined[image error]).

But there are so many existential risks that past progress may not be predictive of the future. I’m not sure we’ll survive the Anthropocene. I’m not sure we’ll survive Trump. Hopefully, I’m wrong.

And now I’m going for a walk during which I’ll meditate on Descartes 3rd maxim:

My third maxim was to endeavor always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in things external to us, all wherein we fail of success is to be held, as regards us, absolutely impossible: and this single principle seemed to me sufficient to prevent me from desiring for the future anything which I could not obtain, and thus render me contented; for since our will naturally seeks those objects alone which the understanding represents as in some way possible of attainment, it is plain, that if we consider all external goods as equally beyond our power, we shall no more regret the absence of such goods as seem due to our birth, when deprived of them without any fault of ours, than our not possessing the kingdoms of China or Mexico, and thus making, so to speak, a virtue of necessity, we shall no more desire health in disease, or freedom in imprisonment, than we now do bodies incorruptible as diamonds, or the wings of birds to fly with.

But I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and frequently repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and, amid suffering and poverty, enjoy a happiness which their gods might have envied.

For, occupied incessantly with the consideration of the limits prescribed to their power by nature, they became so entirely convinced that nothing was at their disposal except their own thoughts, that this conviction was of itself sufficient to prevent their entertaining any desire of other objects; and over their thoughts they acquired a sway so absolute, that they had some ground on this account for esteeming themselves more rich and more powerful, more free and more happy, than other men who, whatever be the favors heaped on them by nature and fortune, if destitute of this philosophy, can never command the realization of all their desires.

From Rene Descartes The Discourse of Method, Chapter 3

June 25, 2018

Great Popular Philosophy Books (that changed my life)

I am a reader of non-fiction. (A post about the most influential work of fiction that I ever read, Orwell’s 1984, can be found here.)

Since a list of all the non-fiction books I’ve read would be quite long—literally thousands— I would like to briefly mention four books that changed my life before I was a professional philosopher and four more that changed my life after I became a professional philosopher.) This doesn’t mean these are the best or most important books I’ve read, or that other books might have had a greater influence on me if I had read them. But these are the ones that most affected me when I was young, and their message resonates within me still.

[image error] [image error]

As a college freshman in 1973, the most memorable book I read wasn’t one assigned for my classes, but one I stumbled upon in the college library—Will Durant’s The Mansions of Philosophy: A Survey of Human Life and Destiny . (An updated version of the book was retitled: The Pleasures of Philosophy[image error].) The book did bear the imprint of a 1920s American male view of women, much to my dismay, but the rest of the book has stood the test of time. Its prose is glorious and its philosophical insights still fresh today. I have reprinted parts of its beautiful introduction as well as its conclusion in previous posts. What drew me to the book was that it was so unlike the foreboding philosophy I was reading in my classes. It seemed Professor Durant was speaking directly to me about substantive topics in plain, clear language. On the first page, he says of his book: “I send it forth … on the seas of ink to find here and there a kindred soul in the Country of the Mind.” I thank him for sending it to my kindred soul.

. (An updated version of the book was retitled: The Pleasures of Philosophy[image error].) The book did bear the imprint of a 1920s American male view of women, much to my dismay, but the rest of the book has stood the test of time. Its prose is glorious and its philosophical insights still fresh today. I have reprinted parts of its beautiful introduction as well as its conclusion in previous posts. What drew me to the book was that it was so unlike the foreboding philosophy I was reading in my classes. It seemed Professor Durant was speaking directly to me about substantive topics in plain, clear language. On the first page, he says of his book: “I send it forth … on the seas of ink to find here and there a kindred soul in the Country of the Mind.” I thank him for sending it to my kindred soul.

[image error] [image error]

Shortly thereafter I happened upon Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian and Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects . I have noted my affinity for the depth and breadth of Russell’s philosophy in a number of my essays, as well as my belief that he was the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century. While professional philosophers will not rank this popular book with his classics in the philosophy of mathematics or his famous work in logic—W.V.O Quine famously said that Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica was “one of the great intellectual monuments of all time”—this was the Russell book that affected me most. I can still remember exactly where I was sitting in a small public library in south St. Louis County in 1974 when I read it.

. I have noted my affinity for the depth and breadth of Russell’s philosophy in a number of my essays, as well as my belief that he was the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century. While professional philosophers will not rank this popular book with his classics in the philosophy of mathematics or his famous work in logic—W.V.O Quine famously said that Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica was “one of the great intellectual monuments of all time”—this was the Russell book that affected me most. I can still remember exactly where I was sitting in a small public library in south St. Louis County in 1974 when I read it.

And while sophisticated defenders of religion may quibble with Russell’s arguments—as they do with any arguments that challenge their preconceived beliefs—the fact is that religion stands on the wrong side of history and will be, as I have argued often, ultimately relegated to the dustbin of history. For, as Russell knew, rational persons could never believe religion’s fantastic claims unless they were indoctrinated, immature, irrational, fearful, feeble-minded or misled. Of course, more sophisticated believers don’t accept the supernatural elements of their religions but hide its nonsense behind esoteric language and obscurantism. Yet to this day I find it astonishing that any marginally intelligent person can take religion seriously. But then perhaps I just don’t get it. Either way I thank Russell for awakening me from my dogmatic slumber more than forty years ago.

[image error] [image error]

Shortly after finishing my undergraduate degree, a friend gave me a copy of Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving, whose very first lines I’ll never forget .

.

Is love an art? Then it requires knowledge and effort. Or is love a pleasant sensation, which to experience is a matter of chance, something one “falls into” if one is lucky? This little book is based on the former premise … “

I have written previously about this small but powerful book and its effect on me. I have not successfully put its message into practice, but I have never forgotten its fundamental lesson—that love is something you have to work at. Its insights have always remained in my subconscious, even though I may have been unable to summon them to affect my behavior. There are few books that say something new and profound about a topic that everybody talks about, but this book did.

[image error] [image error]

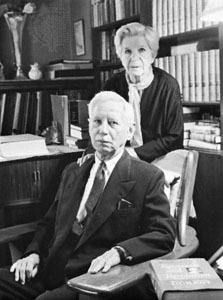

While sitting in the dealer’s room in Las Vegas in 1985, preparing to enter graduate school, I read Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the World’s Greatest Philosophers . Already familiar with Durant, I was determined to read this classic, one of the best-selling philosophy books of all time. From it, I learned that the history of philosophy was a long, continual dialogue, and I was excited to think that in graduate school I might learn enough to be part of that dialogue. It wasn’t so much the philosophers in the book that inspired me, but Durant’s love of them. Today this book is the single most prized possession in my library; thanks to my son, I have a copy signed by Will Durant himself. The book also contains the most beautiful dedication I’ve ever read. It is from Will to his beloved wife Ariel. Thirteen years his junior, he expected her to outlive him:

. Already familiar with Durant, I was determined to read this classic, one of the best-selling philosophy books of all time. From it, I learned that the history of philosophy was a long, continual dialogue, and I was excited to think that in graduate school I might learn enough to be part of that dialogue. It wasn’t so much the philosophers in the book that inspired me, but Durant’s love of them. Today this book is the single most prized possession in my library; thanks to my son, I have a copy signed by Will Durant himself. The book also contains the most beautiful dedication I’ve ever read. It is from Will to his beloved wife Ariel. Thirteen years his junior, he expected her to outlive him:

TO MY WIFE

“Grow strong, my comrade … that you may stand

Unshaken when I fall; that I may know

The shattered fragments of my song will come

At last to finer melody in you;

That I may tell my heart that you begin

Where passing I leave off, and fathom more.”

(Will and Ariel Durant were married almost 70 years and died a few days apart. You can read about their intellectual development, world travels and wondrous love story in Will & Ariel Durant: A Dual Autobiography .)

.)

Now here are four more that changed me after I become a professional philosopher. I reiterate that I’m not saying these are the best or most important books I’ve ever read, but they are ones that stand out as profoundly affecting me.

In graduate school, E.O. Wilson’s  On Human Nature was assigned for a seminar in evolutionary ethics. (I’ve written previous posts about Wilson’s thought here and here.) It is the only one of the books selected as most affecting my thought that was assigned for a class. My mind was startled and transformed by its first few pages.

On Human Nature was assigned for a seminar in evolutionary ethics. (I’ve written previous posts about Wilson’s thought here and here.) It is the only one of the books selected as most affecting my thought that was assigned for a class. My mind was startled and transformed by its first few pages.

… if the brain is a machine of ten billion nerve cells and the mind can somehow be explained as the summed activity of a finite number of chemical and electrical reactions, boundaries limit the human prospect—we are biological and our souls cannot fly free. If humankind evolved by Darwinian natural selection, genetic chance and environmental necessity, not God, made the species … However much we embellish that stark conclusion with metaphor and imagery, it remains the philosophical legacy of the last century of scientific research … It is the essential first hypothesis for any serious consideration of the human condition.1

Yes, I knew all this before I read Wilson, but his prose cemented these ideas within me. Evolutionary biology is the key to understanding mind and behavior, and to understanding morality and religion as well. Life and culture are thoroughly and self-evidently biological. Yet most people reject these truths, choosing ignorance and self-deception instead. They mistakenly believe that they are fallen angels, not the modified monkeys they really are. But why can’t they accept the truth? Because, as Wilson says, most people “would rather believe than know. They would rather have the void as purpose … than be void of purpose.”2

Still, Wilson’s lessons weren’t depressing. Science liberates by giving us self-knowledge, while simultaneously placing within us the hope “that the journey on which we are now embarked will be farther and better than the one just completed.”3 Wilson taught me who we are, the dilemmas we face, and how we must choose our future path. As Wilson says, the evolutionary idea is the greatest and truest one that humans have ever discovered.

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

One cannot summarize Carl Sagan’s The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark , in a few brief paragraphs. One has to read it to appreciate it. Sagan’s basic message is that unreason and superstition are dangerous, while science and reason light the world. But it’s one thing to state this message, it’s another to communicate it. And that’s what Sagan does. If you read this book closely you will learn to despise ignorance and pseudo-science in all their forms.

, in a few brief paragraphs. One has to read it to appreciate it. Sagan’s basic message is that unreason and superstition are dangerous, while science and reason light the world. But it’s one thing to state this message, it’s another to communicate it. And that’s what Sagan does. If you read this book closely you will learn to despise ignorance and pseudo-science in all their forms.

In the first chapter, Sagan quotes Edmund Way Teale “It is morally as bad not to care whether a thing is true or not, so long as it makes you feel good, as it is not to care about how you got your money as long as you have got it.” Right away you know that Sagan cares about truth. He continues ” … it is far better to grasp the Universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.” You may disagree, believing instead that the masses need Platonic noble lies or the Grand Inquisitor’s deceptions, but it is clear from reading Sagan that he won’t deceive himself; he has a passion for the truth.

We can undermine our reason in a thousand ways, but Sagan will have none of it. For if we infuse our understanding with our prejudices and emotions, we live in darkness. But if we dispassionately reason, we will increasingly bring light to that darkness. This process is painstakingly slow, but illumination comes to those who persist. Let there be light.

Victor Frankl’s Man’s Man’s Search for Meaning is the most emotionally moving text that I have ever read. I have taught out of it on many occasions and have read it cover to cover at least five times. Anyone can read it in a few hours. But the book is worth returning to over and over again to be reminded of its central lesson—that meaning can be found in our labor, our relationships, and our suffering. Yet nothing that I write does justice to the experience of reading this book—its power lies in its narrative.

is the most emotionally moving text that I have ever read. I have taught out of it on many occasions and have read it cover to cover at least five times. Anyone can read it in a few hours. But the book is worth returning to over and over again to be reminded of its central lesson—that meaning can be found in our labor, our relationships, and our suffering. Yet nothing that I write does justice to the experience of reading this book—its power lies in its narrative.

So let me describe a single scene in the book to give you a sense of the power of Frankl’s prose. Being marched off to work one dark morning, cold and hungry, while being hit with the butt of rifles by Nazi guards, a fellow prisoner says to Frankl, “If our wives could see us now! I do hope they are better off in their camps and don’t know what is happening to us.” This exchange caused Frankl to think about his wife, her face, her smile, her look:

A thought transfixed me: for the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth—that love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which a man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of human is through love and in love. I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for the brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when a man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way—an honorable way—in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, “The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory.

Afterword – In 1942, Frankl, his wife, and his parents were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto where his father died. In 1944 Frankl and his wife Tilly were transported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, but Tilly was later transferred from Auschwitz to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where she died in the gas chambers. Frankl’s mother Elsa was killed in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, where his brother Walter also died. Other than Frankl, the only survivor of the Holocaust among his immediate relatives was his sister Stella. She had escaped from Austria by emigrating to Australia.4

I will respond to the above with a few lines of original poetry:

And so the world goes on,

good gods perpetually sleeping,

good people perpetually weeping,

and waiting, for a new world to dawn. [image error] The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence[image error]

[image error] The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence[image error]

No book can be profound in the way that Frankl’s book is, but a book can change you for other reasons. Before I read Kurzweil, I thought about prospects for improving humanity in terms of genetic engineering. But Kurzweil made me see another way to transform the species—through artificial intelligence and robotics—and with it a new vision of the future appeared to me. Moreover, the broad outlines of his vision are already coming true.

With the caveat that many things can derail technological evolution—asteroids, viruses, climate change, nuclear war, a new dark ages, etc.—if scientific advance continues, the future will be unlike the past. Let me embellish that. The future is going to be really different than the past. Perhaps everyone knows that, but Kurzweil convinced me of it. He also showed me how universal death is avoidable.

So will the Universe end in a big crunch, or in an infinite expansion of dead stars, or in some other manner? In my view, the primary issue is not the mass of the Universe, or the possible existence of antigravity, or of Einstein’s so-called cosmological constant. Rather, the fate of the Universe is a decision yet to be made, one which we will intelligently consider when the time is right.5

I have written a book, The Meaning of Life: Religious, Philosophical, Transhumanist, and Scientific Perspectives , one of whose central themes is that life can only have full meaning if it persists indefinitely. Kurzweil was the first to suggest to me how this was scientifically possible. I will never forget reading this book on a screened-in front porch in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. It bent my mind in a new direction. [image error]

, one of whose central themes is that life can only have full meaning if it persists indefinitely. Kurzweil was the first to suggest to me how this was scientifically possible. I will never forget reading this book on a screened-in front porch in Mayfield Heights, Ohio. It bent my mind in a new direction. [image error]

I would like to sincerely thank the authors of these books for the contribution they made to my education. Their thoughts transformed me. ___________________________________________________________________________

1. Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) 1-2.

2. Wilson, On Human Nature, 170-171.

3. Wilson, On Human Nature, 209.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viktor_...

5. Ray Kurzweil, The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence (New York: Viking Press, 1999) 260.

I thank Durant, Russell, Fromm, Wilson, Frankl, Sagan, and Kurzweil for leaving a part of themselves in their books, where I found them and was enriched by the encounter.

June 23, 2018

Two Million Page Views!

I made my first blog post on December 19, 2013, and began to use site stats to record traffic in February 2014. About 3 years later, in January 2017, I passed 1,000,000 page views. Now, a year and a half later, I just passed 2,000,00 page view. To date, I have published over 800 posts. I do this work without pay, and my family income is entirely based on social security—thanks FDR—so I’m hardly rich. But I am privileged to share my thoughts in the hope that some might benefit from them.

I would like to thank my readers, many of whom have made insightful comments, and a few of whom I’ve come to know through email. Despite what they might say about writing for themselves, every writer also wants to be read. So again thanks to all who have viewed these pages.