David E. Grogan's Blog, page 7

April 21, 2020

SGT Daniel J. Smith, U.S. Army – From Army Medic to Coaching Wounded Warriors

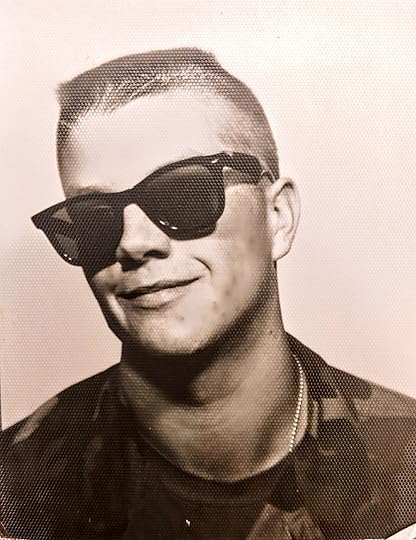

Successful people have one thing in common—they turn life’s challenges into opportunities. Sergeant Daniel Smith, U.S. Army, had lots of challenges early on but overcame them all. His path to success began with a tour of duty as an Army medic, led to his coaching Wounded Warriors in international competitions, and continues to this day through his participation in triathlon and swimming competitions and coaching high school students and para athletes. This is his story.

Daniel J. Smith

Daniel J. SmithDaniel grew up on a farm in Firelands, Ohio, not far from Vermilion, which is located on Lake Erie between Cleveland and Toledo. He had a tough time with math and English in high school, not knowing at the time that he was mildly dyslexic, making classwork difficult. He also had a tough time finding a place to fit in at his high school with all the cliques, so by the time he graduated in June of 1986, he was ready for a change.

The problem was Daniel saw his options as limited. He didn’t have the grades for college. He also didn’t want to work at the local Ford plant or Goodrich chemical plant because he wanted more potential for growth. His one ticket out was the Army, but there was a major drawback to that, too. He didn’t want to have to use a gun to kill—he wanted to help people instead.

Rather than giving up on his dream, Daniel called the Army recruiter who had visited his high school. The recruiter had him take the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) and he scored so high he was able to choose whatever he wanted to do. He opted for field medic, which was a perfect fit. His sole purpose in the Army would be helping people and it would allow him to get a fresh start in a new place. It would also earn him benefits under the GI Bill and the opportunity to attend college after he served. He signed his enlistment papers and agreed to give the Army the next three years of his life.

Daniel reported for duty to the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Cleveland in the fall of 1986. After passing his physical and being sworn in, he was put on an airplane and sent to Fort Bliss, Texas, which was quite a change for him as he’d never ventured far out of Ohio before. He and a busload of recruits arrived sometime after midnight and were told to file off the bus, where they stood in the cold night air and snow flurries. After being berated outside for 45 minutes, the recruits flowed through two lines to get their hair roughly shaved and their uniforms issued. Daniel remembers trying to get to sleep in the barracks that night in an uncomfortable bed with the sound of other young men crying themselves to sleep. As someone with a strong personality who did not like to conform to authority, he thought his life was over—and this was just the first night.

The next day began with physical training and lots more yelling. Daniel couldn’t understand why the instructors had to act so mean. He remembers being singled out because, although he was an excellent athlete in high school, he did the fewest pushups in his company. Getting mocked really angered him, so he set out to prove the First Sergeant wrong. By the end of Basic Training, Daniel could do more pushups than anyone else in his company and was the most improved on the run and in sit-ups. Given his excellent performance overall, he earned the Soldier of the Cycle award.

Daniel J. Smith

Daniel J. SmithAfter Basic Training, Daniel reported to Advanced Individual Training (AIT) for medics at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. As a medic, his job would be to keep wounded soldiers alive until they could be transported out of the area of immediate combat and be treated by a doctor. This meant he had to learn how to give IVs, do tracheotomies, stitch up wounds, and remove partially amputated limbs. His training lasted 4 months and he graduated 2nd in his class of 800 people.

Now a Specialist (E-4), Daniel reported to his first assignment, the 42nd Field Hospital in Fort Knox, Kentucky, during the late spring of 1987. Upon arrival, Daniel began training with his unit on how to quickly deploy and set up a 200 bed hospital. As the Army’s only deployable field hospital, the entire hospital could be packed and loaded onto transport aircraft, dropped into a landing zone, and reassembled in short order. However, since this was peacetime, the medics in the unit had to engage in other activities to keep their skills sharp. One of Daniel’s favorite training rotations involved working at the Ireland Army Community Hospital, where he worked in surgery, the Intensive Care Unit, and the Emergency Room. He found the toughest part of the hospital assignment was dealing with grief counseling.

Not all of Daniel’s training was medically related. In 1988, Kentucky was besieged by forest fires. Daniel’s First Sergeant asked his team whether anyone in the unit could drive a big truck. Having driven some stick shift farm equipment growing up in Ohio, Daniel volunteered. He soon found himself with a buddy driving a two-and-a-half-ton water truck through the mountains of Kentucky into the fire zone to help fight the fires. When the firefighters used up all of the water, Daniel would make another trip for more. He and his buddy often pitched in to help fight the fires in an effort to give some of the exhausted men on the front line a break.

At one point, Daniel and his buddy dozed off in the truck while they were parked in the fire zone. When they woke up, they found the truck surrounded by fire. Afraid they would be burned to death and that the truck would explode, they used water from the truck to clear a path back down the road to safety. It was a close call.

Daniel with Marine athletes at the 2012 Warrior Games

Daniel with Marine athletes at the 2012 Warrior GamesThe other significant training Daniel participated in consisted of two 3-month assignments each year with either the 82nd Airborne Division or the 101st Airborne Division at the National Training Complex (NTC) near Death Valley, California. NTC is a giant training area in the Mojave Desert, making it the perfect location for training U.S. forces for desert warfare. Daniel would be assigned as the medic for an airborne infantry unit and exercise with them under the intense temperature extremes of the Mojave Desert. The training was serious business and dangerous, as the following incident illustrates.

During one nighttime exercise, Daniel’s unit was convoying down a mountain in blackout mode, so drivers could only see the vehicle in front of them using night vision gear. Daniel was in the last vehicle in the convoy, which was typical since he was the medic. That way, if anyone had any medical issues, they could get out of their vehicle and wait for Daniel to come by. Daniel’s vehicle, however, was a Vietnam era M561 Gama Goat, which often broke down and was unreliable in the rocky terrain. Capping off the setting, Daniel’s driver was a devout Christian, so he was praying and praising Jesus out loud while he navigated the treacherous road at the rear of the convoy. Suddenly, there was a thud and the Gama Goat came to an abrupt stop—they’d hit a boulder and the vehicle’s front wheel broke off. Without a radio and in the pitch black darkness, they had no way to alert the other vehicles in the convoy, which continued driving unaware that Daniel’s vehicle had become disabled. Daniel and his driver stayed with their vehicle for 3 days with no food or water, watching out for scorpions, listening to the howls of a pack of coyotes surrounding them every night, and even scaring off a mountain lion, until a helicopter finally spotted them and they were rescued. Had the helicopter not seen them, Daniel is sure they would have died.

Photo taken by Daniel of the World Trade Center from Liberty State Park on September 11, 2000

Photo taken by Daniel of the World Trade Center from Liberty State Park on September 11, 2000Not everything Daniel did was training. On one occasion, he helped save an ROTC cadet who fell 80 feet into a ravine and onto her M16 rifle, breaking her back. On another occasion, he prevented a soldier from bleeding to death after his hands were crushed during repair work on a tank. In each case, Daniel was awarded an Army Commendation Medal for helping save the soldier’s life.

Daniel was discharged in the late summer of 1989 and returned to Ohio. He began working at a lakeside bar in Vermilion where lots of people from New York and New Jersey vacation. One day, two women at the bar asked him if he wanted to go to the beach with them and he accepted. At the beach, one of the women started setting up camera equipment and asked him if she could take a few pictures. That impromptu photo shoot led to Daniel entering a modeling competition in New York City, which he won in November of 1990. He then began a 14-year modeling career that had him doing photo shoots in countries around the world and castings with many top models and photographers.

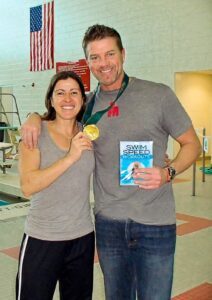

Gold Medalist Sheila Taormina with Daniel

Gold Medalist Sheila Taormina with DanielRecognizing he would not be able to model forever, Daniel learned the art of photography from the master photographers doing his shoots and he started his own photography business. He also began working out more intensely and fell in love with biking, swimming and running, so he was a natural for triathlons. In 2002, after he’d left New York and moved back to Ohio, the athletic and the artistic sides of his life merged into an opportunity to take photographs for an Olympic gold medalist swimmer, Sheila Taormina, who was writing what would turn out to be a worldwide best-selling series, Swim Speed Secrets.

In 2011, when Sheila and Daniel were promoting the Swim Speed Secrets series, they were given the opportunity to do a swim clinic for the U.S. Wounded Warrior Battalion in Colorado Springs. One week later, they were hired to coach swimming for the Marine Wounded Warrior team to prepare them for the international Warrior Games. The United Kingdom’s Prince Harry would subsequently throw his full support behind the games and their name was changed to the Invictus Games. Daniel served as the assistant swim coach for 2011, 2012, and 2013. He worked closely with many Wounded Warrior athletes from the United States and allied countries during those years and considers them to be some of the most rewarding years of his life. He still does swimming and triathlon clinics whenever needed.

Daniel continues to be an avid triathlon participant and, at 52, is a national-caliber master swimmer. More importantly, he coaches both track and field and swimming for Avon Lake High School, located on the outskirts of Cleveland. One student para swimmer he coaches was a silver medalist at the Parapan American Games and is currently training to qualify for the 2021 Paralympics in Tokyo. He also does an occasional modeling shoot, proving he still has it after all these years.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Daniel J. Smith, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service in the 42nd Field Hospital and for his dedicated efforts working with Wounded Warriors. We are also thankful that he continues to work with high school athletes, helping them aspire to be the best they can be. We wish him continued success and fair winds and following seas.

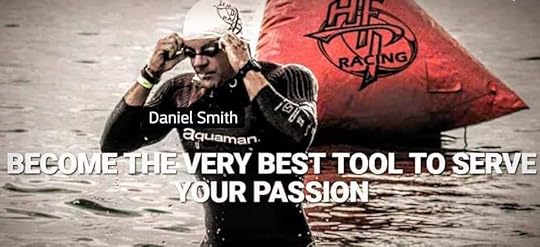

Daniel today in an Aquaman ad – he still has it!

Daniel today in an Aquaman ad – he still has it!

March 12, 2020

Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army – Helping Children Devastated by the Vietnam War

Wars inflict pain and suffering—no one knows that better than Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army. He saw war’s horrors firsthand and even heard a priest reading him his last rights as he lay on the brink of death in a field hospital in Vietnam. Yet Billy and the other members of his unit were able to look past the death and destruction to help South Vietnamese nuns carve out a sanctuary for one hundred children orphaned by the war. Looking back, Billy realizes the sanctuary saved him, too. This is his story.

Billy Terrell

Billy TerrellBilly’s childhood can best be described as riches to rags. He was born in Newark, New Jersey, in 1944, to a solid middle class working family. His father owned a successful construction business, which at its peak employed 22 people. With two cars in the driveway and the only television on the street, it looked like Billy’s family was living the American dream. That dream came to an abrupt end in 1952 when the construction company went bust, thrusting Billy’s family into poverty. In the first of many moves over the next ten years, Billy’s father relocated the family to the coast near Asbury Park, New Jersey.

The move did not improve the family’s financial situation. Many nights, Billy and his siblings went to bed cold and hungry, while his troubled mother and despairing father proved unable to support their family. As if admitting defeat, Billy’s father made him quit school when he was 16 to find a job to help support the family. Dressed in rags and missing his four front teeth after they became brittle, broke, and had to be pulled, Billy found it impossible to find anything but the most menial low-paying jobs. That’s when his Aunt Laura came to his rescue by letting him live with her in Newark and paying for the dental work he needed to replace his missing front teeth. With the newfound confidence of a full smile, Billy set out to find a job and a way to get started in show business.

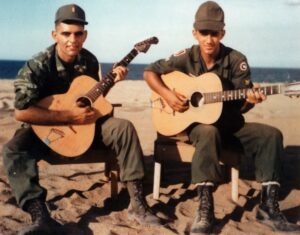

2d Lt Jordan Klempner and Billy playing guitar on the beach at Tuy Hoa in 1967

2d Lt Jordan Klempner and Billy playing guitar on the beach at Tuy Hoa in 1967Billy’s first break came when he was 17 working as a dishwasher at the Howard Johnson’s in Asbury Park. The bell captain from the nearby Empress Motel saw how hard Billy worked and got him a job bussing tables and delivering room service. Although he only had the first Monday off each month, Billy taught himself to play guitar and started playing gigs around town. Sometimes the acts performing at the Empress Motel would ask Billy to join them on stage to do a song or tell a few jokes. Clay Cole, the host of a popular New York TV show, saw Billy and said he had some people he wanted Billy to meet in New York. One week later, Billy, who now at 18 had Frankie Avalon looks and an infectious smile, signed with his first manager and did his first “demo” record. Although he didn’t get a recording contract, he inked a deal as a songwriter with Kama-Sutra Productions for $50 per week. By the middle of May 1965, The Duprees had recorded Billy’s first song on Columbia Records, They Said It Couldn’t Be Done. It looked like Billy was finally on his way, but Uncle Sam had other plans.

In May of 1965, Billy received his draft notice and notified his employer that he would soon have to leave for the Army. The people at Kama-Sutra Productions didn’t want him to go, even holding a séance for him in a blacklight lit room with a beatnik talking in tongues and banging on a gong. When the séance didn’t change Billy’s mind, they suggested he report for duty in women’s underwear and holding a dead fish. Having none of it, Billy thanked the staff for their concern, but told them that his grandfather had immigrated to the United States in 1902 from Italy and made a life for himself and his family, so he felt it his duty to serve his country in the Army. Billy said goodbye and walked out of Kama-Sutra Productions—his grandfather died the next day.

Johnny Young of Bayonne, New Jersey, and Billy at Phan Rang in 1966

Johnny Young of Bayonne, New Jersey, and Billy at Phan Rang in 1966The Army delayed Billy’s report date so he could attend his grandfather’s funeral, but on August 5, 1965, it was time to go. Billy reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Newark. From there he was bussed with his fellow draftees to Fort Dix, New Jersey, for 8 weeks of Basic Training. Although it was tough, Basic Training gave Billy a sense of self-worth he had never had before. Now he was part of a team, had a clean uniform to wear and three meals a day to eat. He started to become healthier and gain weight, and developed a sense of pride in what he was doing. At the same time, he recognized what he and all of the other draftees had in common. They were all poor and uneducated, from the bottom rung of society. Despite his new-found pride, he couldn’t help but think society thought them expendable. Billy would wrestle with this dichotomy throughout his time in the Army.

After completing 8 weeks of Basic Training and 8 more weeks of Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) at Fort Dix, Billy and a friend he made at Basic Training, Bob Reed, reported to Quartermaster School at Fort Lee, Virginia. Quartermasters manage the Army’s logistics and supply chain, making sure the fighting forces have what they need to win battles. Billy and the other soldiers trained for 4 weeks, making ready for assignments in Vietnam.

Part of the preparations included an orientation to duty in Vietnam, where the instructor told the new soldiers that they could not ship their cars to Vietnam and that their families could not visit them there. This offended Billy because it was obvious they could not do these things—Vietnam was a war zone. Irked that whoever prepared the orientation must have thought that he and the other trainees were ignorant, Billy stood up when the instructor asked if anyone had any questions. He said, “you’ve told us throughout training that in South Vietnam, we can’t tell who the enemy is because the Viet Cong have infiltrated the villages. Why don’t we just go into North Vietnam and get this over with?” The instructor didn’t appreciate Billy’s strategic thinking and sent a sergeant over to tell him to sit down, which he did.

The night before Billy’s Quartermaster class was to ship out, a sergeant and some Military Police roused Billy, his friend Bob Reed, and 2 others. The sergeant told them to pack their gear as they were moving out now. Not knowing what was going on, the men gathered their gear and went with the sergeant to the train station, where they were put on a train for Fort Riley, Kansas. There they joined the 96th Quartermaster Battalion, which would soon deploy as a unit to Vietnam. By May of 1966, the unit was ready. After transferring to Oakland, the men in the unit boarded the USNS General Nelson M. Walker (T-AP-125), a World War II era transport ship, en route to Vietnam.

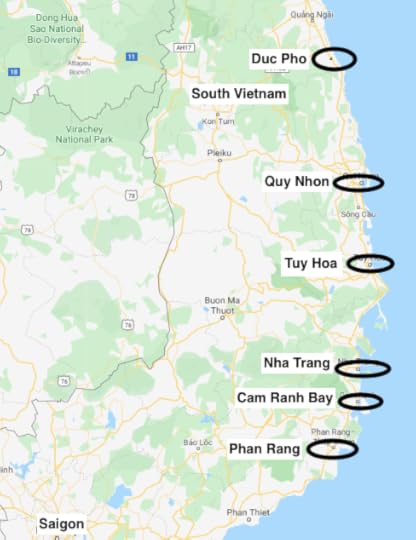

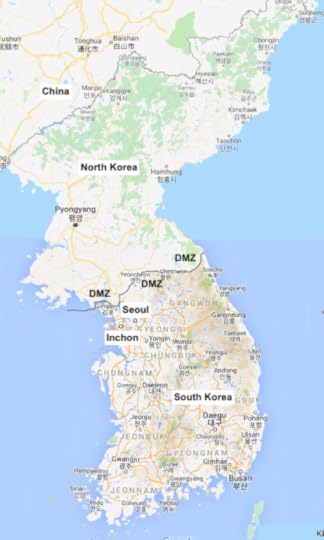

Map showing locations relevant to Billy’s tour in Vietnam

Map showing locations relevant to Billy’s tour in VietnamThe ship arrived in Cam Ranh Bay, Republic of South Vietnam, on May 28, 1966. Billy was ferried ashore in a Navy LCU (landing craft – utility). He and Bob Reed made it a point to take their first step onto Vietnamese soil together. Once everyone was ashore, the battalion broke into 2 companies, with Billy being assigned to the 226th Supply and Service Company. The unit spent a few days in Cam Ranh Bay and then drove by truck to Phan Rang, about 80 kilometers northeast of Saigon, where they set up camp. Billy remembers the camp being an isolated jungle setting not far from shore, with waste high grass all around the camp.

Phan Rang was a staging area for the company, so they had little to do other than prepare for their next assignment. This exacerbated racial tensions, which tended to surface when the men had free time on their hands. The unit included white soldiers from the South and African American soldiers from the North, and they did not get along. The unit also had members who had been given the choice of joining the Army or going to jail after committing violent crimes, so maintaining discipline was difficult. At night it could be particularly scary, with junior officers and sergeants sometimes being attacked and beaten. Billy was able to get along with all groups, because he had life experiences in common with both the enlisted soldiers and the officers, so he was left alone. Still, the racial tensions complicated an already dangerous wartime environment.

At the end of July 1966, Billy and the rest of the 226th Supply and Service Company embarked a Navy vessel and sailed up the coast to Tuy Hoa, which would be their supply base camp for the remainder of Billy’s tour in Vietnam. The first order of business was to set up tents to live and operate out of. Then they laid down a metal landing surface to allow supply aircraft to land and take off from the camp.

Billy’s Conex Box Post Office in Tuy Hoa

Billy’s Conex Box Post Office in Tuy HoaBilly was responsible for handling the unit’s mail, so he convinced the Company Commander, Captain Virgil Bon, to allow him to set up a post office in a Conex box. He used tin cans labelled alphabetically to sort letters, which he would then deliver to the men in his unit. He also flew by helicopter to units all around the area to deliver mail, sometimes bringing an added surprise like cans of soda on ice to the men in the field. More than once a cold soda resulted in a hug from a grateful recipient. Despite these lighter moments, the delivery runs were deadly serious. On more than one occasion, Billy remembers hunkering down in the helicopter while the machine gunner blasted away at targets below with the aircraft’s M-60 machine gun.

Billy also stood perimeter guard duty at night, which could be terrifying not only because it was so dark, but also because he was isolated and easy prey for the convicted felons who really didn’t want to be in the Army. Viet Cong infiltrators were also a concern, but primarily because they wanted to interrupt a fuel pipeline running from the beach to the base. One bright moonlit night, Billy heard tapping on the pipe, so he slipped out of the bunker he was manning and took cover in the nearby brush just in case the bunker was being targeted. The enemy did not attack, but it was a terrifying experience, nonetheless.

Life was also made difficult because Billy and the other soldiers could not trust the local population, who were friends by day and Viet Cong sympathizers by night. Vietnamese locals, who often worked at the camp, sometimes planted grenades and other charges among the pallets of supplies. When the forklift operators tried to move the pallets, they were injured or killed. The roads around the camp were also mined, so soldiers were always at risk of stepping or driving on a mine. The lack of trust flowed both ways as some of the more out of control soldiers tormented the locals. On one convoy driving along a narrow dirt road, Billy saw a truck driver intentionally swerve toward an ox pulling a cart carrying a farmer and his family. The animal panicked and bolted, throwing the farmer’s family under the truck, where they were crushed. The anguished cries of the farmer distraught over the death of his wife and children still plague Billy.

In the midst of all this suffering, a ray of hope cut through the war and brought life to everyone it touched. One afternoon in September 1966 when Lieutenant John Sheer was burning inedible C-rations, they discovered two nuns picking through the cans and scavenging for food. Lieutenant Sheer told the nuns, who spoke no English, that the food was bad and gave them $10 worth of military scrip to buy some food. An hour later they returned with a priest who spoke some English and could explain to Lieutenant Sheer the nuns’ plight.

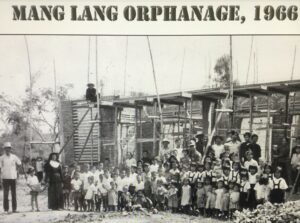

Mang Lang Orphanage under construction

Mang Lang Orphanage under constructionThe priest explained that the nuns ran the Mang Lang Orphanage, which had been destroyed by the Viet Cong. They had escaped with about 100 children and were now jammed into the tiny wing of a ramshackle hospital near town. Lieutenant Sheer asked Billy to go with him to visit the site. When they saw it, they were immediately convicted to help Sister Michelle and Sister Teresa with the orphanage. They began by setting out cigar boxes around the camp where soldiers could contribute money. Lieutenant Sheer also asked his church in Chicago to donate. Within a few weeks they had collected $600, which was enough for the nuns to buy land and build a new orphanage.

That wasn’t all the men did. Lieutenant Sheer, Billy, and other members of his unit became frequent visitors. Billy took the children chocolate he’d traded other soldiers for in return for the cigarettes he received in his C-rations. He also taught the boys, who were all under 10, to play baseball. Every time Billy visited, the children ran to him and clung to him when he had to go.

Billy with boys from the orphanage in 1966

Billy with boys from the orphanage in 1966The Mang Lang orphanage became a sanctuary for the children, where they actually had enough to eat and people who loved them. Just as important, the orphanage became a sanctuary for Billy and the other soldiers of the 226th Supply and Service Company, offering a lifeline to humanity in the middle of so much death and destruction.

In December 1966, Billy participated in a convoy led by soldiers from the 28th Regiment of the South Korean Army, who provided tenacious security for Billy’s base camp. As the convoy drove through the heavy monsoonal rain, Billy became delirious and ran a high fever. The Korean officer in charge of the convoy ordered that Billy be taken to the 563rd Medevac Company, which had a landing zone for casualty evacuation helicopters (“Dustoff choppers”) on a hill north of Tuy Hoa. The plan was to evacuate Billy to the 67th Evacuation Hospital in Quy Nhon, but the rain was too heavy for chopper operations. With the only tent already full of casualties, Billy and several other evacuees were wrapped in ponchos and left outside in the rain until morning. When the weather cleared, Billy was flown to the 67th Evacuation Hospital, and subsequently transferred to the 8th Field Hospital in Nha Trang, where they had the expertise to treat him.

By the time Billy arrived, he was baking with a 105-degree malaria-induced fever and hallucinating. The doctors said they had to bring his fever down or they would lose him, so they gave him an ice bath, which was incredibly painful. Moreover, when they removed his right boot, they found a hole through his foot between two of his toes and his skin rotting to the point where his shin bone was visible. After the ice bath, Billy remembers being put to bed and overhearing a doctor instruct the nurses to take his temperature every 30 minutes, give him a shot every hour, and if he makes it until morning he might have a chance.

Although his eyes were swollen almost completely shut, Billy could see USO Christmas lights decorating the hospital tent. Evoking strong emotions even now, Billy remembers staring at the Christmas lights and repeating over and over, “Oh my God, what is my mother going to do?” He was afraid that if he closed his eyes and fell asleep, he would die. Eventually he passed out. Later he saw an intense light and thought he must be dead. He jokes now that he started looking around for lost relatives, but seconds later he realized the bright light was the sun peeking through a gap in the sandbags surrounding the tent. He’d made it through the night!

Later in the day, Cardinal Francis Spellman (the Roman Catholic Vicar of the U.S. Armed Forces), the great evangelist Billy Graham, and motion picture star and comedienne Martha Raye, visited Billy. Reflecting that Billy was still in very serious condition, Cardinal Spellman administered him his last rights while Billy Graham held his hand and Martha Raye held his feet. Cardinal Spellman also gave Billy a crucifix, which he took home from the war.

After a day or so, the doctors told Billy he had to start walking to help circulate his blood or he would not make it. He was so weak, though, that he couldn’t even lift the heavy end of a spoon from a tray to feed himself. Then Martha Raye, who the soldiers affectionately called “Colonel Maggie”, reappeared at his bedside. She repeated what the doctors told him and said he wasn’t going to die on her watch. Then she helped Billy stand and told him to put his feet on hers and she walked him across the room. She visited at least one more time and did the same thing, until finally Billy gained enough strength to walk. Billy is certain that if Colonel Maggie had not come by to help him, the malaria would have killed him.

Although reduced to 89 pounds and looking like a living skeleton, Billy began to recover. He wondered whether he would be sent to the Philippines or Japan before going home, but the Army had other plans. His doctor informed him that he was being sent back to his unit. Billy asked how that could be given his weight and that he’d been in the hospital for over 30 days. The doctor countered that Army regulations required that he be returned to his unit because he’d not been in the same hospital for over 30 days. Knowing that he couldn’t fight the man and reminded of his Boot Camp feelings of being expendable, Billy shrugged it off and returned to his unit to finish out his tour.

Nearing the end of his tour, Billy and his friend, Lieutenant Jordan Klempner, flew in a Huey helicopter from Tuy Hoa north to a fire base near Duc Pho, where the helicopter came under fire. The pilot guided the helicopter to a landing zone behind four 105mm howitzers firing rounds at the enemy. Billy and Lieutenant Klempner jumped to the ground before the helicopter peeled away. They ran toward a group of vehicles assembled nearby and boarded a three-quarter ton truck in a convoy heading to Duc Pho. As they passed through several hamlets along the way, Billy sensed something wasn’t right and laid down on the bed of the truck with a round chambered in his rifle. Lieutenant Klempner, who was still standing in the back of the truck, asked Billy what he was doing. Billy said it was too quiet—he couldn’t hear birds anymore—just the sound of the trucks. Lieutenant Klempner got down too and moments later, gunfire erupted at the front of the convoy, killing the lead driver. A firefight ensued, pinning down Billy and Lieutenant Klempner. Eventually, two jets dropping napalm suppressed the attack and the convoy was able to continue to Duc Pho, carrying its dead and wounded. The next day, Billy and Lieutenant Klempner returned to the landing zone in a column of vehicles that included tanks at the beginning and the end, with a Huey helicopter gunship overhead spraying the terrain on both sides of the road with M-60 machine gun fire. After returning to the landing zone, Billy and Lieutenant Klempner flew back to Tuy Hoa. Billy considers the attack on the convoy on the road to Duc Pho to be his most trying experience of the war.

Because Billy only had a few days left in country, Captain Bon sent him to the relative safety of Cam Ranh Bay to await his flight back to the States. When he boarded the chartered Northwest Orient airliner for home, he was surprised to see his friend, Bob Reed, on the flight. Everyone onboard, from the most junior soldier to the most senior officer, sat in silence as the plane took off, all instinctively with their eyes closed and holding hands. When it was clear the plane was out of range of any danger, the men erupted in cheers, hugging and tears. They had survived their tours in Vietnam. The date was May 29, 1967–they were finally going home.

Once back in the States, Billy faced many challenges. The first came when he went home and learned his father had suffered a serious heart attack while he was gone. Billy initially felt responsible because he believed the news of his near death experience from malaria had been the cause. The second challenge came from the way everyone treated him. He had grown up watching World War II movies and saw the welcome home the troops received. He expected the same, wearing his uniform around town when he first arrived home. Instead of being welcomed, people rejected him.

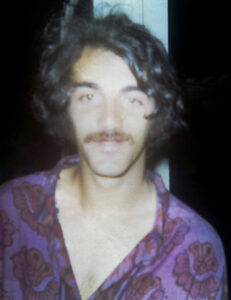

Billy Terrell in 1968

Billy Terrell in 1968Dejected and suffering from the trauma of war, Billy turned to the bottle. Things got so bad that at one point, he traded the crucifix he’d been given in the field hospital in Vietnam for a drink. He reached rock bottom on June 23, 1968, when he showed up drunk and disheveled for his brother’s wedding. Afterwards, he looked at himself in the mirror and felt like a disgrace. He’d survived the war and made it home to his family. Thousands of other soldiers hadn’t been so lucky. Out of respect to them and their mothers, he had to fix himself. He gave up drinking that day and set his sights on getting back into the music industry. That meant finding a cheap office in Asbury park and buying a broken down piano for $25, which he taught himself to play by practicing up to 20 hours a day.

Five months later, singer Debbie Taylor took a song Billy wrote, Never Gonna Let Him Know, to #5 on the R&B chart. Billy never looked back. Over the course of his career, he wrote, arranged, and/or produced over 2,000 records, with 64 hitting national and international charts. He produced records for the likes of Bobby Rydell, Helen Reddy and Maria Muldaur, and helped rekindle the career of his teen idol, Frankie Avalon, in the 1970s by creating a disco arrangement of Frankie’s 1959 #1 hit song, Venus. The 1976 hit helped Frankie land the role of Teen Angel in the blockbuster movie, Grease.

Despite all of his post-war success, Billy still had a few more scores to settle. He’d moved forward with his life after his brother’s wedding by trying to suppress his memories of the war, only to have them continue to torment him. Agent Orange also took its toll, afflicting him with several forms of cancer, all of which he’s beaten. His ultimate success came when he realized he continued to suffer from PTSD and sought counseling with other veterans to address it.

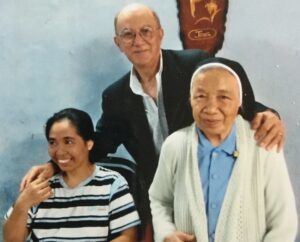

Billy with Sister Michelle and Ahn Doe at Mang Lang Orphanage in 2013

Billy with Sister Michelle and Ahn Doe at Mang Lang Orphanage in 2013In 2008, Billy found a trove of photographs of the Mang Lang orphanage he’d taken during the war. Curious, he searched the Internet and discovered the orphanage was still there, as was Sister Michelle. Then he did something he thought he would never do—he returned to Vietnam to visit the orphanage and confront some of his demons.

Billy’s visit to the orphanage in 2013 was life-changing, once again providing him with a sense of peace and sanctuary. He met with Sister Michelle, now in her 80s, and 4 women who remembered Billy from his visits when they were children during the war. One of the women, Ahn Doe, who had deformed feet, had been dropped off at the orphanage by her family because they didn’t want to raise a disabled child. During Billy’s 2013 visit, she told him through an interpreter that she loved the sweets Billy used to bring during his visits to the orphanage and that when Billy held her, it was the only time she ever felt safe. Ahn’s revelation brought Billy to tears, as he realized his efforts had made a difference. It was the beginning of the healing process.

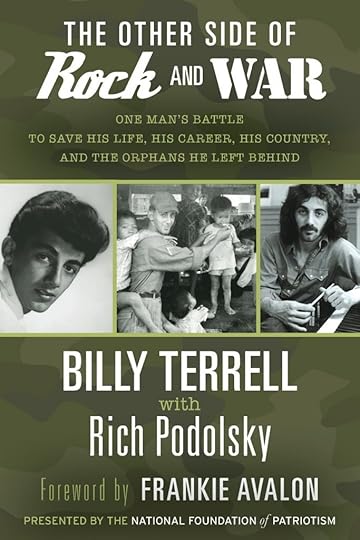

Now semi-retired, Billy freely shares his story with civic groups, veterans organizations, and schools. He’s even written his memoir, The Other Side of Rock and War, published by the National Foundation of Patriotism in 2018. If you’d like to learn more about Billy’s amazing life, including stories about the rock and roll legends he’s encountered like Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, George Harrison, Ravi Shankar, Cream, and Janis Joplin, I encourage you to read his book, which is available through Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Billy Terrell, U.S. Army, for his dedicated service to our country during the Vietnam War. Not only did he do all the Army asked of him and more, he epitomized the honor and dignity of the American soldier through his kindness to Vietnamese orphans whose lives had been upended by the war. Billy gave the most vulnerable victims of the war hope and made them feel safe, changing their lives forever. He continued to change lives after returning home by bringing smiles to people’s faces through his music. For all he has done throughout his life, we thank Billy and wish him fair winds and following seas.

Billy Terrell’s Memoir – The Other Side of Rock and War

Billy Terrell’s Memoir – The Other Side of Rock and War

February 8, 2020

Specialist Jack Murphy, U.S. Army – Saluting Fellow Veterans with a Heartfelt Song

Veterans instinctively understand each other. No matter who they are, where they come from, what their rank was, or what they did in the military, there is an unshakable bond between them. Explaining that bond can be difficult, but some people are gifted in conveying it in ways that help others understand. Specialist Jack Murphy, U.S. Army, has the gift. Twenty-five years after surviving war in the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam, Jack wrote a moving tribute to his fellow Vietnam veterans called The Promise. The song has touched the hearts of thousands and was played during the Memorial Day remembrance ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, in 1996. Jack could not have written The Promise without first having lived its lyrics. This is his story.

Jack was born and raised in Croydon, Pennsylvania, a small town about 20 miles north of Philadelphia. His father was a World War II veteran, having landed on Omaha Beach at Normandy and later fighting in the Battle of the Bulge. After the war, he worked for the Kaiser-Fleetwings Aircraft Company in Bristol, Pennsylvania. His mother stayed at home raising Jack and his brother and sister. Jack attended Delhaas High School and was really into music. He played in a number of bands outside of school.

By the summer of 1968, Jack could see the writing on the wall. He was working at a local cigar factory and all the young men his age were being drafted. He knew it would be only a matter of time before his number came up, too, so he tried to convince 3 of his buddies to enlist with him. After a few days of arm-twisting, all 4 young men went to the local recruiting center to join the Army. They took an aptitude test, signed a few papers, and it was official—they owed the next 3 years of their lives to Uncle Sam.

Jack and his friends reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station, or MEPS, in Philadelphia, on September 26, 1968. There they were given a physical exam, sworn into the Army, and loaded onto a train en route to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for Basic Training. As an 18-year-old kid traveling with his friends on a train, Jack found the whole experience exciting. All that changed when they got off the bus at Fort Bragg and met their platoon sergeant for the first time. They were definitely in the Army now.

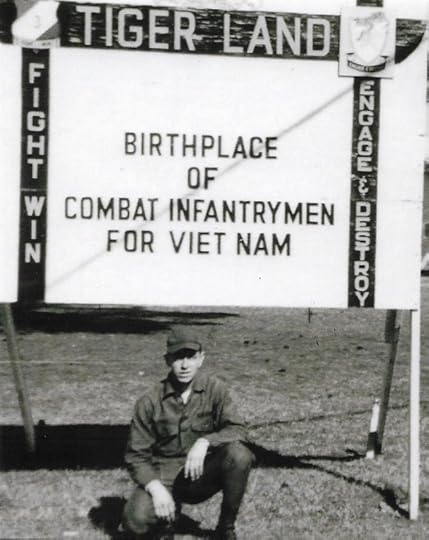

Jack Murphy at Tiger Land at Fort Polk, Louisiana

Jack Murphy at Tiger Land at Fort Polk, LouisianaBasic Training is still ingrained in Jack’s memory. He and his friends were assigned to the same platoon, so they were able to spend the next 8 weeks together learning to become soldiers. One of the hardest parts for Jack was the physical training because he was not an athlete in high school. He was more into music and hanging out on the corner “looking good”. He and his friends managed to get through it, but graduation was where they parted company. Jack’s three friends went to helicopter schools, while Jack went to Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Jack was on his own.

The AIT training at Fort Polk was known as “Tiger Land”. Its purpose was to train American soldiers how to fight and survive in Vietnam’s jungle environment. Jack describes it as “rough, very rough”. There he learned to conduct ambushes and to respond when caught in one. He also learned how to spot boobytraps by navigating through a course with boobytraps hidden along the route. Jack knew he had to master the skills if he was going to come back from Vietnam alive.

By the beginning of February 1969, training was over and it was time for the real deal. Jack went home for 30 days leave and at the end, said goodbye to his family at the airport in Philadelphia. His father, knowing better than most what Jack was about to go through, simply said “be careful” as tears welled up in his eyes. His mother was less restrained and cried openly. Jack then boarded the plane for the first leg of his trip to Vietnam.

Jack’s plane landed at San Francisco International Airport. From there, he went to Travis Air Force Base, where he boarded a chartered plane along with lots of other replacement soldiers headed to Vietnam. The plane landed at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in the Republic of South Vietnam on March 5, 1969. When the door opened, the heat, humidity and smell of diesel fuel rushed in, engulfing Jack and the rest of the new arrivals. It was so overpowering, Jack remembers thinking “what kind of place is this?” He didn’t have long to think about it, because soon after he got off the plane, he and the other replacements were loaded onto a bus heading for the sprawling U.S. base at Long Binh. The bus windows were covered by a metal mesh to prevent grenades from being tossed inside—a grim reminder of the serious business Jack was about to become involved in.

At Long Binh, Jack reported to the 90th Replacement Battalion. As a replacement soldier, Jack did not know what operational unit he would be assigned to. Instead, he and the other replacement soldiers were temporarily assigned to the 90th Replacement Battalion to await their permanent assignment. While there, they in-processed and received additional instructions about their time in Vietnam, but mostly they waited anxiously until their name appeared on a bulletin board identifying the unit they would be joining. Jack only had to wait a couple of days before his name appeared. His new assignment: the 199th Infantry Brigade (Separate) (Light).

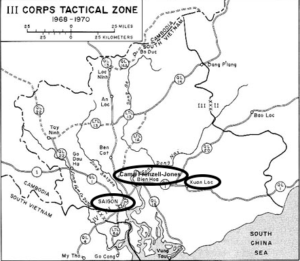

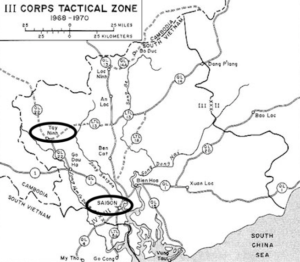

III Corps Area of Responsibility 1968-70 (Source: U.S. Army)

III Corps Area of Responsibility 1968-70 (Source: U.S. Army)Jack was not the only replacement heading to the 199th Infantry. He and the other new arrivals climbed aboard trucks and headed for the 199th Infantry’s main base at Camp Frenzell-Jones. Once there, they went through a week of boobytrap and rifle range training, made more intense than their stateside training with the realization that now their lives depended upon it. With the refresher training under his belt, Jack boarded a CH-47 Chinook helicopter and headed out to Delta Company of the 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry, which manned a company-sized fire base in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta.

When Jack arrived at the fire base, he was assigned to a squad and a bunker. As he started to talk to the men in his squad, he found them helpful, but they kept their distance. That is, they told him what to watch out for, but he soon realized they didn’t want to become close because they’d already lost too many friends. They told Jack to listen to the guys who’d been there a while and do what they did and he’d get through it. In other words, if Jack wanted to survive, he had to learn fast.

When it came time to bed down for the night, everyone laid down on the ground outside the bunker. Already concerned he was going to have trouble sleeping during his first night in the field, he asked why no one was sleeping in the bunker. His squadmates told him they slept outside because there were giant rats in the bunker. Later that night, the Viet Cong launched rockets at the fire base and everyone except Jack took cover in the bunker. Someone inside the bunker shouted at him to get inside, but he responded, “You told me there are rats in there.” The voice called out again, “Get in here, you dumbass. Would you rather get blown up or deal with the rats?” Jack joined his squad in the bunker.

The next day, Jack was assigned to work on a detail outside the wire (meaning outside the protective perimeter of the fire base) eliminating trees so there would be a clear field of fire around the base. After working for a while, his group was instructed to return inside the wire because a patrol was returning and they didn’t want any misidentifications or friendly fire incidents. When Jack returned to the camp, he saw the patrol emerge from the tree line. He asked the First Sergeant if that was the patrol they were expecting and just as he did, the returning patrol’s point man stepped on a Viet Cong boobytrap armed with a 105-millimeter artillery shell. At that exact moment, reality set in for Jack. He and those around him could be killed at any minute. All he could do was accept it and hope.

The next day, Jack joined his patrol on his first search and destroy mission, wading off through the rice paddies from the relative “safety” of the fire base in search of Viet Cong. The route took them over the area where he’d witnessed the boobytrap detonate the day before, only now it was he who was trudging through the dangerous terrain. On all such missions, the squad had to be ever vigilant, trying to detect and avoid the boobytraps they knew were there but could not see.

During the first three months of Jack’s tour, his squad deployed to different fire bases, sometimes using Boston Whalers and airboats to move around. Each of the airboats had a driver and a person riding shotgun to watch for snipers and boobytraps. On one occasion when Jack was preparing to go out on a patrol via boat, he learned that the person riding shotgun was going home, so they needed someone to replace him. Jack volunteered. After Jack and the driver dropped off the patrol, they returned on June 2nd, 1969, to take the patrol some cases of rations. When Jack got off the boat to deliver the rations, he set off a boobytrap, wounding him and 5 others. He had to be evacuated to the 3rd Army Field Hospital in Saigon, where he spent 2 weeks, and later to Cam Ranh Bay for 2 additional weeks. Jack would never volunteer for anything again. The only bright spot occurred in the 3rd Army Field Hospital when a famous singer from the 1930s-1950s, Tony Martin, visited Jack’s ward after a show and pinned a Purple Heart on Jack and the other wounded soldiers.

After completing his recuperation at Cam Ranh Bay, Jack returned to the 199th Infantry at Camp Frenzell-Jones. As soon as he arrived, he learned that the unit was being deployed to the vicinity of Xuan Loc, northeast of Saigon in the III Corps area of responsibility. His new outpost was Fire Base Libby, located in dense triple canopy jungle. This came as a shock to the men in the unit, as they were used to fighting the Viet Cong in the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta and now they were being asked to fight North Vietnamese regular soldiers in the jungle. The new assignment called for different tactics but was just as dangerous—Jack’s unit sustained casualties on the first night it arrived.

Although the enemy, the terrain, and the tactics were different, the unit’s search and destroy function was the same. Jack and the other 16-20 members of his platoon would set out from Fire Base Libby and patrol in the field for 15-20 days, seeking to engage the enemy. At the end of that time, they would return to the fire base for 3 days to rest, get showers and clean clothes, and gear up for the next patrol. On these patrols, the danger was not so much from boobytraps as it had been further south, but from engagements with North Vietnamese units. This was Jack’s life for the next 6 months.

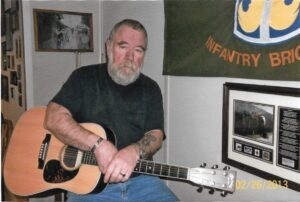

Jack with his guitar at home

Jack with his guitar at homeWith 30 days to go on his Vietnam tour, Jack was able to take advantage of an Army program to help him earn his GED. Not only would this get him his high school diploma, but it also had the significant benefit of getting him out of the field. He studied for his GED during his final month in Vietnam, and he would later finish it at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after returning to the United States.

Jack finally left Vietnam on March 5, 1970, one year to the day after he arrived. He considers that day to be the best day of his life. He departed from Tan Son Nhut Air Base, retracing his steps through Travis Air Force Base, before flying home to his family in Philadelphia. He still had 2 years to go on his 3-year enlistment, but the Army allowed him to work off the remainder of his commitment in the Fort Dix Commissary, which was quite a change from humping through the jungle as a radio-telephone operator just trying to stay alive. Jack was honorably discharged from the Army on November 2, 1971. His three friends who enlisted with him on September 26, 1968, also survived the war.

After the war, Jack returned to small town life north of Philadelphia. He married and had 2 children, and took a job working at a steel mill for U.S. Steel. After 10-11 years, the market for American steel dried up and the mills closed, so Jack found a new job driving for the medical clinic at the Willow Grove Naval Air Station. He eventually retired from that position.

Although Jack left Vietnam in 1970, Vietnam did not leave him. In fact, he’d been going to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, every Memorial Day and Veterans Day for years to pay his respects to his fallen comrades. He’d also wanted to write a song about his experience in Vietnam, but the inspiration wasn’t there. Then, one night in 1995, the inspiration suddenly came. Jack picked up his guitar, turned on his tape recorder, and in 15 minutes created the music and lyrics for The Promise. He took the tape to a producer at a local recording studio who liked it so much he wanted to produce it. They spent the next 2 hours recording the final version. The Promise was later played during the 1996 Memorial Day Ceremony at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Since then, the song has spoken to thousands of veterans and their families about the lasting impact the Vietnam War has had on those who fought and served.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Jack Murphy for his service in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. Despite being in constant danger and threat from enemy fire, Jack did his duty with bravery and distinction. Most important, he’s never forgotten those he served with, standing side-by-side with them in time of war and preserving their memory after his return. We thank Jack for his unselfish service to our country and wish him fair winds and following seas.

Now, please enjoy the song The Promise, by Jack Murphy:

January 18, 2020

Lt. Col. John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force (Retired) – Staying One Step Ahead of Disaster in Vietnam

Military pilots are a breed apart. They are risk takers and, at least by my standards, fearless. They aren’t satisfied with just getting by—they need to grab life by the reigns and live it on the edge. That description fits Lieutenant Colonel John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force (retired), to a tee. From being awarded the Silver Star in Vietnam to climbing some of the highest mountain peaks around the world, John has done it all. Even more important, John has lived a life of service to his country and his community. I could tell when I was interviewing him that I was speaking to a great American. This is his story.

Lt. Col. John Heimburger and 2 Marines at a local high school ceremony

Lt. Col. John Heimburger and 2 Marines at a local high school ceremonyJohn was born in 1941 and raised in Tolono, Illinois, just a few miles south of the University of Illinois in Champaign. His dad did everything from drive a gasoline delivery truck to serve as the chief of the local fire department, while his mom worked at home raising John and his brother and two sisters. John learned the value of work at an early age, distributing grocery store handbills and earning a penny for each one delivered. He later became a paperboy for the Champaign-Urbana Courier. His paper route not only allowed him to save enough money to buy a bicycle, but it led to an event that changed his life forever.

When John was 14, he won a trip to Washington, DC, by recruiting new subscribers for the newspaper. One of the sites he visited during the trip was the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, where he witnessed the plebes (first-year midshipmen) trying to scale a greased granite monument to place an officer’s hat on the top. Not only was it entertaining, but the midshipmen’s spirit, camaraderie, and teamwork also really made an impression on John. Later in the trip, John’s group had its picture taken on the Capitol steps with Congressman William Springer, who represented Tolono in the U.S. House of Representatives. Congressman Springer asked John what his favorite part of the trip was, and John told him it was his visit to Annapolis. When Congressman Springer heard this, he asked if John would like to go there. John said yes. Then the Congressman asked if John would like to be a pilot. John again said yes. Congressman Springer concluded by saying, “Have your parents call me in 3 years when you are ready to go to college. We’ve got a new Air Force Academy in Colorado and I can help you attend.”

Cadet John Heimburger and his father at the Air Force Academy

Cadet John Heimburger and his father at the Air Force AcademyThree years later, after graduating from Unity High School in Tolono, John reported to the new Air Force Academy just north of Colorado Springs as part of its fifth class, the “Golden Boys”. He credits his success at the Academy to his parents for raising him with a sense of personal discipline and to the Boy Scouts for giving him the self-confidence and leadership skills he needed. He dove right into Academy life, playing defensive end on the football team and even meeting Navy great, Roger Staubach, on the gridiron. He also excelled at field hockey and was invited to join the U.S. Field Hockey Team for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. As if that wasn’t enough, he sang in the Cadet Chorale, marched in President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural parade, and received his diploma with President Kennedy standing nearby. After graduating, he married Susan Young, to whom he was happily married for 18 years, in the Air Force Academy Chapel.

John next reported for flight training at Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock, Texas. There he spent approximately 13 months learning to fly the Air Force’s first supersonic capable training jet, the T-38 Talon, which had only recently been introduced. John loved to fly and it soon became clear he was a natural pilot. He also liked to press the envelope, and on one occasion just after he soloed, it almost cost him dearly.

On that occasion, John flew his T-38 near its ceiling of 48,000 feet, turned off its IFF transmitter so his altitude could not be tracked from the ground, and put his plane into a dive. Once he got the jet going fast enough, he pointed the plane’s nose upward with afterburners on to see what would happen when he went above 48,000 feet. When he reached 53,000 feet—an altitude where he could see the curvature of the earth—one of his two jet engines shut down. Although he managed to restart it after dropping 20,000 feet, he was sure he’d be in serious trouble. To his surprise, no one noticed his exploit and he continued his flying career, now informed by what could happen if he exceeded aircraft limits. On a more somber note, John remembers standing at attention on the base’s parade ground to mark President Kennedy’s death in November 1963. He had now come full circle with the late president, having marched in his inauguration.

John Heimburger flying a C-130 over Okinawa

John Heimburger flying a C-130 over OkinawaJohn graduated near the very top of his class from flight training, so the Air Force allowed him to choose the type of aircraft he would fly operationally. John picked the C-130 “Hercules”, a rugged 4-engine turboprop transport plane designed to move and supply troops on short runways at or near the battlefield. He chose C-130’s because he thought they would give him the best chance of getting into the Vietnam War—he was right! After completing his C-130 advanced pilot training at Sewart Air Force Base in Tennessee, he reported to the 35th Troop Carrier Squadron at Naha Air Base on Okinawa, arriving on December 31st, 1964. Shortly after arriving, he was presented with a certificate for being the #1 graduate from his C-130 training class at Sewart.

On January 1st, 1965, just 24 hours after arriving at Naha, John received a call at his quarters—it was time for his first mission. He reported to the squadron, got the C-130 ready, and lowered its cargo ramp. A black limousine approached and drove up the ramp until it was on board the plane. The cargo doors closed and the plane took off for Cambodia. After they landed, they opened the cargo doors and the car drove off.

The plane taxied near some woods to wait for the car’s return. Soon, a horde of people descended upon the crew seeking to sell them everything from food to souvenirs. One man approached John with a handful of stones. John found one that looked like a gray star sapphire that would fit his Air Force Academy ring exactly. He asked the man the price and the man answered $300. John told him he only had $37 (which was true), so the man left. A little later, he came back and dropped the price to $200, which John still could not pay. He came back a third time, only to get the same answer. When the limousine finally returned to the plane, the man came running back and sold John the stone for $37. Later in Tokyo, John replaced the original stone in his Academy ring with the gray star sapphire he acquired in Cambodia. He treats the stone with special respect, assuming that since it was an exact match for his Academy ring, it must have been recovered from an American serviceman killed in the war. It is one of John’s most treasured possessions.

Map of South Vietnam showing Saigon and Nha Trang

Map of South Vietnam showing Saigon and Nha TrangJohn flew his initial C-130 missions as copilot, helping qualify him to fly later as the aircraft commander. That opportunity came on a mission hauling sandbags from Saigon to Da Lat, which was up in the mountains. John recalls there was extremely limited visibility and is certain that had it not been for the skill of his navigator, they would have abandoned the mission. Instead, they broke through the clouds a mile from the runway and made a routine landing on what had been a perilous flight. From this point on, John would fly as an aircraft commander.

Bad weather wasn’t the only thing trying to kill John. On June 24th, 1965, John and his aircrew ate dinner at a floating restaurant on the Saigon river in Saigon. The next day, Viet Cong guerrillas blew up the restaurant, killing scores of people, including 12 Americans. John felt like that summarized his entire time in Vietnam—he was always just one step ahead of disaster.

By the latter part of 1966, the Air Force had lost so many pilots within South Vietnam proper that it held a lottery at Naha Air Base to recruit more. The pilots in John’s squadron were considered eligible for the lottery because, although they routinely flew dangerous missions in Vietnam, they were not permanently assigned there. For example, John’s typical mission schedule would be to fly to South Vietnam and stay in country for 10 days, flying up to 5 missions each day. He would then return to Okinawa for a week, where his wife and newborn son were waiting for him, until it was time to begin the cycle again. Pilots selected in the lottery would transfer to Vietnam and remain there until their tour of duty ended.

Cessna Bird Dog in flight over Vietnam

Cessna Bird Dog in flight over VietnamThe names of the approximately 440 C-130 pilots on Okinawa were put into a hat and 20 names were drawn. John was one of the 20 and because he was junior in rank, he was assigned to fly as a forward air controller, or FAC. This job was extremely dangerous because it involved flying a very slow single-engine Cessna O-1 “Bird Dog” over the jungle, identifying and marking enemy positions with smoke rockets, calling in tactical airpower to attack the target, and then flying over the target again to assess and report the damage. Later, a slightly faster plane, the 2-engine Cessna Skymaster was used, but the missions were still incredibly dangerous as evidenced by the need to replace the many pilots killed in the war.

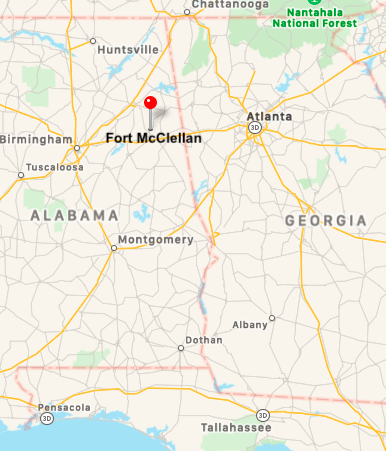

Having “won” the lottery, John reported to Eglin Air Force Base in Florida to learn to operate as a FAC. After completing his training, his next stop was Nha Trang, South Vietnam, where he flew missions primarily in the III Corps area of responsibility in the vicinity of Cam Ranh Bay. He roomed with field surgeons from the 8th Army, who liked having him around because he had his own jeep and could take them to the beach when they had free time. In return, the surgeons let John scrub up and taught him to be a surgical technician in the operating room. The experience helped John land a job years later on the faculty of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in Baltimore.

During one such surgical assistance session, a badly burned FAC pilot was brought in. John knew the officer from the Air Force Academy, although he was a couple of years ahead of John. His burns were severe and he could not talk, but John spent a lot of time with him, talking to him even though he could not respond. Being too weak to move, the officer could not be evacuated to a hospital better equipped to treat him. Finally, some new burn ointment arrived from Texas and the injured officer improved enough to be transferred stateside. He silently saluted John before he departed, even though John was the junior officer. Miraculously, the injured officer survived the war and John reconnected with him many years later.

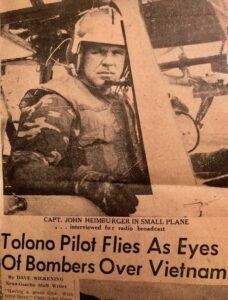

News-Gazette story about John Heimburger in Vietnam

News-Gazette story about John Heimburger in VietnamDuring one FAC mission out of Nha Trang, John took a hometown reporter along to see what flying low and slow in search of the enemy was like. During the flight, the reporter noticed a line running up the side of a mountain and pointing north. John flew down to take a closer look, snapping some pictures with a black and white Polaroid camera and reporting what now appeared to be several parallel and lateral open areas on the side of the mountain. A special forces team later reconnoitered the site and discovered it was a North Vietnamese radio antenna, likely used to report on U.S. military activities in the III Corps area. Strike missions were ordered and the antenna was destroyed. The Champaign-Urbana Courier, the News Gazette, and WLRW Radio all covered the story, making sure the people of Tolono knew what their hometown hero was doing in the war.

John was also exposed to Agent Orange during his time as a FAC. During “defoliant” missions, 3 C-123 twin-engine “Provider” aircraft would fly in a tight formation low over the jungle spraying Agent Orange. John flew above the formation watching for enemy fire, ploughing through the Agent Orange mist floating above the spraying aircraft. John is certain some of his health issues are Agent Orange related.

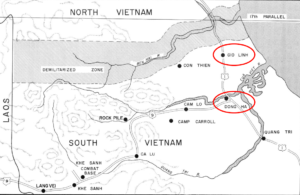

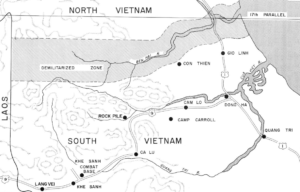

Around October of 1967, John was reassigned to the Marine fortress at Khe Sanh. The base was under constant attack by the North Vietnamese, who were determined to replicate their 1954 victory over the French by surrounding and defeating the Marines. The Marines, however, held their ground. John flew his Bird Dog from the Khe Sanh airfield, helping detect any positions and calling in supporting fires.

Khe Sanh near the DMZ between South and North Vietnam (Source: U.S. Army)

Khe Sanh near the DMZ between South and North Vietnam (Source: U.S. Army)During one such mission just before Christmas in 1967, John was called upon to assist two F-4 aircrew shot down near Tchepone Pass, Laos. Armed only with an M14 rifle, a revolver, and smoke rockets, and taking small arms fire from North Vietnamese forces, John held off the enemy and provided cover for one of the downed aircrew as he moved from bomb crater to bomb crater up the side of a mountain. With John flying low overhead in his Cessna Bird Dog, the aviator made it to a point where an unarmed Marine helicopter could rescue him. After refueling in Khe Sanh, John returned to the scene of the F-4 crash to search for the other aviator, all the time taking fire from the North Vietnamese. Unfortunately, the second aviator did not survive the crash. For his bravery under fire and disregard for his own life, John was awarded the Silver Star, our military’s third highest award for valor in combat.

In December of 1967, bad weather around Khe Sanh forced John to land at Nkhon Phanom Air Base in Thailand. He arrived just in time to see the Bob Hope Christmas Show. Even better, because John knew the officer in charge of the Officers Club, he attended a buffet with Bob Hope, Raquel Welch, Barbara McNair, Miss World, and other cast members after the show. This was the second of three times John would meet Bob Hope during his Air Force career.

As the North Vietnamese lay siege to Khe Sahn at the beginning of 1968, the mortar, artillery and rocket attacks intensified and small arms fire increased. John continued to operate from the base, flying FAC missions and watching as B-52s dropped tons of high explosives on the enemy forces hiding in the jungle. When John flew too close to the B-52s’ targets, the shock waves from the bombs buffeted his Cessna through the air.

Despite the incessant bombing and supporting artillery fire from U.S. forces, the North Vietnamese pressed their attack until it became too dangerous for John to operate from Khe Sanh’s airstrip. He was directed to leave, but continued to fly from Khe Sanh for two additional weeks. Finally, he was told that if he enjoyed being an Air Force captain, he needed to get out of Khe Sanh and operate from Da Nang. The Marines defending Khe Sanh displayed their admiration for him when he finally left by designating him as an honorary Marine. They also held on to Khe Sanh until the North Vietnamese siege broke. The Marines pulled out of Khe Sanh in June of 1968 and the base officially closed in July.

John left Vietnam and returned to the United States in the latter half of 1968. He had been designated for the Skylab astronaut program, but his entry into the program was delayed. Instead, he reported to Hurlburt Field on Eglin Air Force base for 6 months duty as a FAC instructor, helping train pilots to do what he had done so successfully for the past year. At the end of the 6 months, the Air Force again delayed John’s entry into test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base in California and continued him as a FAC instructor in Florida. Six months later, the same thing happened. When the Air Force sought to delay him a fourth time, John decided to return to civilian life, having accrued enough time on active duty to do so. Still, he continued to serve in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard in Utah, Maryland and Colorado. He retired in 1986 as a Lieutenant Colonel having flown 665 combat missions. He was awarded the Silver Star, 2 Distinguished Flying Crosses, the Bronze Star, 26 Air Medals, and the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry.

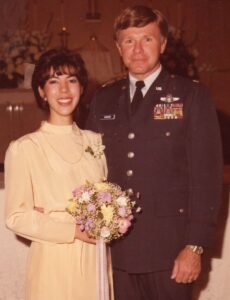

John and Chris at their wedding

John and Chris at their weddingJohn’s civilian life is every bit as extraordinary as his military career. After the Air Force, he obtained his MBA from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, graduating in 1972. He spent the next 4 years on the faculty of Johns Hopkins University before accepting the invitation of a friend to fly for Frontier Airlines, which later merged with Continental Airlines. He formally retired from Continental when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 60, having amassed nearly 31,000 flying hours. He’s an active member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and an ardent supporter of U.S. servicemembers. Finally, after his first marriage ended amicably, John married his wife Chris, who has stood by his side now for over 38 years.

No story about John would be complete without mentioning the impact of Scouting on his life. John and his best friend, Lin Warfel, joined Cub Scouts as young boys. Lin’s mother, Adeline, was their Den Mother. Adeline lost her husband on the beaches of Normandy during World War II and was like family to John. John credits Scouting with reinforcing the values his parents taught him, allowing him to be successful in life. John has tried to pay that back to Scouting, working with Boy Scouts and leading trips to exciting places around the United States, helping mold young men into solid citizens. John’s influence worked best at home, though, with three of his sons becoming Eagle Scouts.

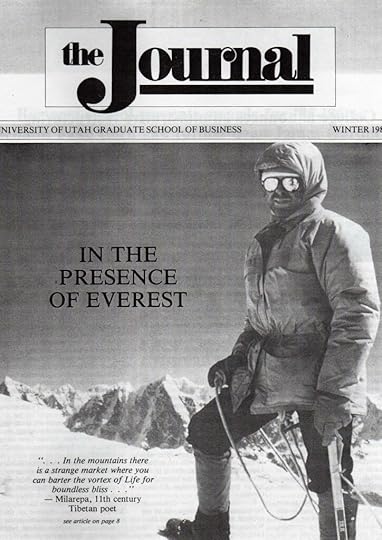

John Heimburger on the summit of Imje Tse near Mount Everest

John Heimburger on the summit of Imje Tse near Mount EverestAn outgrowth of Scouting is John’s love for the outdoors. He remembers as a boy marveling at the news Sir Edmund Hillary and Tensing Norgay had successfully reached the summit of Mt. Everest in 1953. He climbed to the top of the highest tree in his backyard and thought to himself that someday he, too, would climb that mountain. Never losing sight of his dream, John pioneered an adventure program at Frontier Airlines and, together with other Frontier and Continental Airlines employees, climbed mountains around the world, including in the Alps and the Andes, as well as Mount Fuji in Japan and Mount Kilimanjaro in Africa. Their initial climb was to the summit of Island Peak, also known as Imje Tse, near Mount Everest in the Himalayas. There, without oxygen, John and one other of the 8 Frontier Airlines employees on the expedition reached the 20,350 foot summit!

Although it has been a long time since John marched across the Air Force Academy campus, he still has a strong bond with his graduating class. At their 50th reunion in 2013, John made sure the program included a tribute to their wives in the Air Force Academy Chapel. John wants everyone to understand the crucial role military spouses play in supporting our armed forces. While servicemembers are deployed around the globe in harm’s way, it’s military spouses who hold their families together amid the reality that they may never see their loved ones again. The 700 people attending the tribute wholeheartedly agreed!

Words will never be enough to thank Lieutenant Colonel Heimburger for his many years of selfless service to the United States. Through his example during times of war and times of peace, he has embodied all that is good about America. He’s taught countless young men and women to see challenges as opportunities rather than barriers, and reinforced that the United States is the land of the free and the home of the brave. Voices to Veterans proudly salutes Lieutenant Colonel Heimburger for all he has done for our country. We wish him fair winds and following seas.

Lt. Col. John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force

Lt. Col. John W. Heimburger, U.S. Air Force

November 2, 2019

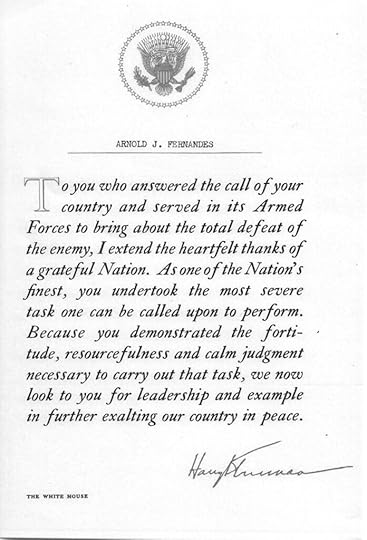

Petty Officer Second Class Arnold Fernandes, U.S. Coast Guard – From the Aleutian Islands in World War II to the Korean War

The bravery of the men and women in the United States Coast Guard is legendary. They set sail in the most hazardous weather conditions to rescue mariners and migrants at sea and to interdict smugglers trying to bring illegal drugs to our shores. The Coast Guard is also a military service, with ships and crews in harm’s way taking the fight to the enemy sometimes far from our shores. No story better exemplifies the bravery, heroism, and commitment of the men and women of the Coast Guard than that of Petty Officer Second Class Arnold Fernandes, who served in the Coast Guard during World War II and the Navy during the Korean War. This is his story.

Arnold’s parents immigrated to the United States from Portugal, initially settling in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where Arnold was born in January 1924. Arnold’s father was a commercial fisherman, plying his trade in the unforgiving waters of the north Atlantic until 1926, when he moved the family to the more hospitable environment of southern California. There they settled into the Portuguese fishing community of Point Loma, a beautiful, hilly peninsula bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the east by San Diego Bay. Arnold lived in Point Loma through his junior year of high school, but moved to Chula Vista in San Diego County for his senior year. He graduated from Sweetwater High School in June of 1941 and enrolled in the fall at San Diego State College.

Coast Guard Cutter Perseus (WPC 114)

Coast Guard Cutter Perseus (WPC 114)After a little more than a year of college and with World War II raging in Europe and across the Pacific, Arnold and three of his best friends from San Diego State decided to enlist in the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard was well-respected in the fishing community, and Arnold held it in high esteem. In fact, in the late 1930’s, the Coast Guard saved his father’s life after his father became very ill on his fishing vessel while operating off the coast of Mexico. So, it was only natural that on November 5, 1942, Arnold raised his right hand and answered the Coast Guard call of duty. Without being given uniforms or training, he and his three friends were immediately sent to the Coast Guard Cutter Perseus, which was homeported in San Diego. Arnold became a “sonar striker”, which meant he would be trained to send high-pitched pings through the water using the ship’s sonar equipment. When the pings bounced off the hull of a lurking submarine, he could pinpoint its location and help vector his ship in for attack.

Unfortunately, sonar training wasn’t available on board the Perseus, so Arnold transferred to Naval Station San Diego to attend sonar school. He graduated in early 1943 with the rank of Petty Officer Third Class, and, with a logic only those who have served in the military can appreciate, was detailed to a small patrol boat in San Pedro, California, that had no sonar capability. Instead, he was given quartermaster duties, which meant he was charged with helping to navigate the boat. The boat’s Executive Officer was a famous actor, Henry Wilcoxon, who had leading roles in a number of Cecille B. DeMille films and also starred in movies with the likes of Vivien Leigh and Lawrence Olivier. Arnold remembers Wilcoxon getting a kick out of watching him dive off the ship’s bridge for man overboard drills.

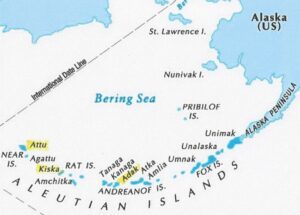

The Aleutian Islands in the northern Pacific Ocean

The Aleutian Islands in the northern Pacific OceanPatrolling off the coast of sunny San Diego in early 1943 was short-lived. After about one month, Arnold transferred to the Coast Guard Cutter Aurora in the Aleutian Islands. In a little known theater of the war, the Japanese had invaded the islands of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians in June of 1942 as a diversion for their planned invasion of Midway Island, further south. That gave the Japanese bases on U.S. soil from which they could attack U.S. ships and facilities on other islands in the Aleutian chain. Arnold realized this first-hand when he arrived at the U.S. Navy base in Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island en route to the Aurora. There he saw a repair ship smoldering after being bombed by the Japanese. With the smoke rising over the harbor, Arnold realized for the first time he was in the middle of a war. He continued west to the Navy base on Adak Island, where the Aurora was homeported. This time the ship did have sonar, as its primary duties were anti-submarine patrol, search and rescue, and escort duty.

Coast Guard Cutter Aurora (WPC 103)

Coast Guard Cutter Aurora (WPC 103)In May of 1943, the Aurora sailed with the U.S. task force charged with retaking Attu and Kiska Islands from the Japanese. The U.S. landed troops on Attu Island on May 11, 1943, without adequate equipment and under horrible weather conditions. The operation culminated on May 29th, when the Japanese commander led one of the largest Banzai attacks of the war against the unsuspecting Americans, breaking through the American lines and into the rear echelon. The attack was subsequently beaten back with heavy losses and complete annihilation of the Japanese attackers—only 28 enlisted men survived out of a force of around 2500. The U.S. suffered nearly 4,000 casualties retaking Attu, including 549 killed in action. The invasion is seared in Arnold’s memory.

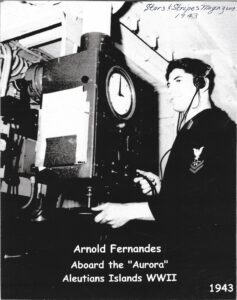

Arnold operating sonar onboard the Aurora in 1943. The photo appeared in Stars & Stripes magazine.

Arnold operating sonar onboard the Aurora in 1943. The photo appeared in Stars & Stripes magazine.Several other events stand out for Arnold in 1943. On one occasion when the Aurora was patrolling off Attu Island, Arnold was serving as the duty sonarman and made a definite contact with what he believes was a Japanese 2-man submarine trying to position itself to torpedo the Aurora. The Aurora went to general quarters and the crew manned all the ship’s guns. The ship also dropped depth charges and fired hedge hogs, and eventually the hedge hogs scored a hit, exploding when one made contact with the submarine. Although Arnold does not believe the engagement was recorded in the ship’s log, he is certain of both the contact and the resulting hit.

On another occasion, the Aurora rescued the crew of a downed PBY-Catalina patrol aircraft. The plane’s crew was laying on the wing, half-frozen in the frigid weather off the Aleutians. Then, on July 19, 1943, the Aurora was called upon to rescue the crew of the cable laying ship Dellwood, which had struck a rock while laying cable between Dutch Harbor and the outlying Aleutian Islands. The Aurora saved the crew without loss of life, but the Dellwood sank in Massacre Bay, the site of the U.S. Army’s landings on Attu Island.

Arnold’s most harrowing experience occurred on December 11, 1943, when the Aurora and the other ships in Task Force 8.6 were ordered to return to Adak Harbor to seek shelter from a mammoth storm heading toward them with 200 mile-per-hour wind gusts. On the way to the harbor, the Aurora’s starboard side started to ice up and the ship began to list from the weight. With the wind and waves tossing the 165-foot vessel to and fro, crewmembers went onto the main deck and, after securing themselves with safety lines, began to chip away the ice using fire axes. Although they were able to clear away a lot of the ice, the seas became so rough that the Captain gave up the effort and ordered all hands below deck. The men were further directed to secure all watertight hatches.