David E. Grogan's Blog, page 3

February 14, 2024

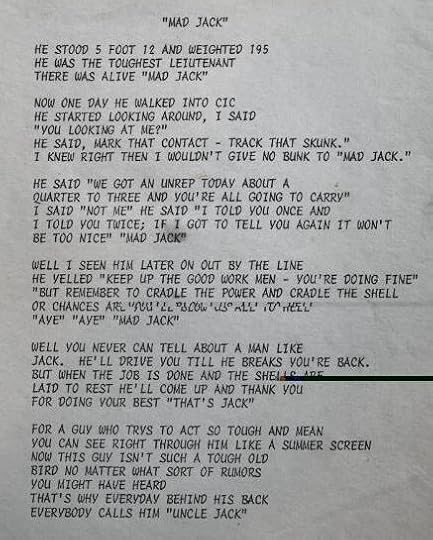

Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army – Three Things to Count On

It’s often said there are only two things in life you can count on, death and taxes. Ask Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army, and other young men during the mid-1960s and they would tell you there was a third – the draft. Mark received his draft notice shortly after his college notified his local draft board he was eligible, thus beginning a chain of events that would lead to him patrolling the jungles of South Vietnam in search of the Viet Cong. This is his story.

Mark was born in November 1945 in Aurora, Illinois, and raised in Naperville, a Chicago suburb located about thirty miles west of the city. His father was a pillar of the Naperville community. Not only was he an attorney and the owner of an insurance consulting business with offices in Naperville and Chicago, but he also served as a Naperville City Councilman and was active in his church. His mother, who had a master’s degree from the University of Michigan, taught English to foreign scientists working in and around Batavia, Illinois. Mark was the third of the family’s five children and, like his two brothers and two sisters, attended Naperville Central High School. As a big kid, he played football and wrestled, competing in the 180-pound weight class. He excelled in both sports, participating for all four years of high school. He also did well in his studies and was inducted into the National Honor Society prior to graduation.

Mark graduated from high school in June 1963. He enrolled in Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, in the fall. Duke proved not to be a good fit, so after completing eighteen months, he transferred to Aurora College to be closer to home. Still, he found it hard to focus on his studies, especially since he participated on the college’s wrestling team. After a year, officials at Aurora College determined he wasn’t making sufficient progress and notified the local draft board.

With the Vietnam War raging and the Army and Marines needing more and more young men to fill their ranks, the draft board took swift action. Soon, Mark received a draft notice instructing him to report to the induction center in Wheaton, Illinois, at 6:00 a.m. on August 25, 1966. Although the notice itself surprised Mark, he was excited because he thought it would give him the opportunity to go to Vietnam and serve his country.

Until the report date arrived, Mark worked for a concrete construction company. Then, on Thursday, August 25, he reported as directed to the induction site. The atmosphere was subdued as it was early in the morning, and no one wanted to be there. Mark took his place with the other draftees and the officials told them they needed six Marines. Mark thought about being a Marine, but before he could say anything, six others volunteered. That meant Mark and the remaining draftees were headed for the Army.

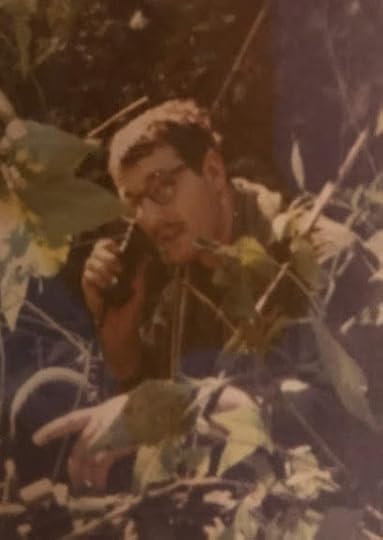

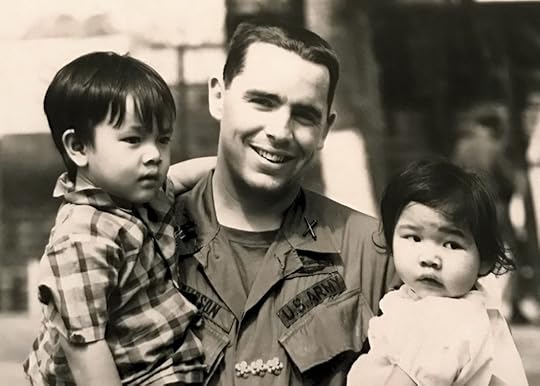

Mark Myers out on patrol in Vietnam

Mark Myers out on patrol in VietnamThe officials at the Wheaton induction center administered the oath of service to all the draftees and then sent them on their way for initial training. Mark was sent to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, but after a week of waiting there, he and those with him were flown to Fort Lewis, Washington, to begin Basic Training. Before boarding the flight, they were weighed, causing Mark to wonder if there was something wrong with the airplane such that the crew had to be careful not to have too much weight onboard. Much to his relief, the plane arrived safely at McChord Air Force Base just outside of Tacoma, Washington.

Mark and the other draftees transferred by bus from McChord to Fort Lewis to commence Basic Training. Mark was tagged almost immediately for a leadership position, Trainee Platoon Sergeant, which he attributes to him being a big guy and in good shape. As Trainee Platoon Sergeant, Mark stood in front of his platoon’s formation and gave instructions regarding formation movements. He also assigned people to KP (“kitchen police”) when it was their turn. Finally, he had to eat last when the platoon went to chow to ensure all his men got to eat. More than once, this resulted in Mark stuffing his mouth full of food when the allotted time for the meal ended and the platoon had to leave the chow hall.

Overall, Mark found Basic Training tolerable. Fort Lewis itself was beautiful, especially with Mount Rainier visible in the distance. Even the weather cooperated while he was there, with the only rainy period unfortunately coinciding with the platoon’s week in the field. No one complained, though, because everyone was in the same boat. Even the physical training proved not to be a problem given Mark’s wrestling experience and work as part of a concrete construction crew. He found rifle training more challenging, particularly because some trainees cut corners to get high scores. Mark was content to play it straight and accept whatever score he earned.

That marksmanship score, together with Mark’s other accomplishments, proved good enough for his platoon sergeant to nominate him for Soldier of the Cycle. Unfortunately, the platoon sergeant didn’t tell Mark about the nomination and only instructed him to report to a particular office at a particular time. Mark did as directed, wearing his usual training uniform. When he arrived, the other nominees were already there looking all spit and polished in their dress uniforms. Although Mark did not get the award, he considered it an honor to have been nominated.

Mark graduated from Basic Training in early November 1966. Pursuant to orders he received prior to graduation, he reported to Fort Sam Houston, located in San Antonio, Texas, for training to become an Army medic. Just as at Basic Training, the sergeants at Fort Sam Houston recognized Mark’s leadership potential and designated him as a squad leader. This gave him administrative responsibilities in addition to his medic training, which consisted of instruction on a wide range of medical skills. Mark learned how to triage illnesses and injuries, administer shots and medication, and even perform basic procedures like initiating an IV and administering an enema. Basically, Mark was trained as a first responder who had to be prepared to keep seriously wounded soldiers alive until they could be evacuated to a medical facility for further treatment by doctors and nurses.

Mark’s administrative responsibilities weren’t quite as daunting. On one occasion, Mark was directed to inform a soldier in another barracks he had KP duty. Mark found the soldier asleep in his bunk but couldn’t wake him up. He pulled the man to the floor; still the soldier did not wake up. Afraid something might be wrong, Mark alerted the soldier’s sergeant, who was not surprised. Together, they dragged the sleeping soldier by his hands and feet into the shower, where they woke him up by streaming cold water on him. On another occasion, the Army recognized Mark and the other soldiers designated as squad leaders with an evening out at a local brewery for a few beers. This was a memorable event for Mark, as he had very recently turned twenty-one. The next day, it was back to training as usual.

As Mark approached graduation from medic training, he was offered the opportunity to attend jump school to become airborne qualified. Because this would increase his monthly pay from around $125/month to around $180/month, Mark accepted the opportunity and transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia. He hoped it would lead to him being assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and sent to Vietnam so he could take part in the action. He arrived at Fort Benning in January 1967, where he learned to parachute from airplanes and operate as part of the Army’s highly mobile airborne forces. He also participated in rigorous physical training, including long runs, which he again excelled at given his history of physical fitness and involvement in sports.

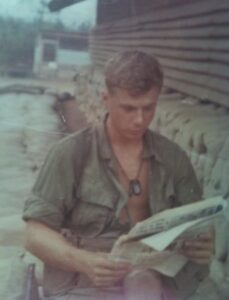

Mark Myers reading a newspaper next to his barracks – note the sandbags around the barracks

Mark Myers reading a newspaper next to his barracks – note the sandbags around the barracksAfter completing the three-week jump school at Fort Benning, Mark earned the right to wear parachutist wings on his uniform. However, instead of joining the 101st Airborne Division and heading to Vietnam as he had hoped, he received orders to report to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for general medic duty. He was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 325th Infantry, which was part of the 82nd Airborne Division. He lived in the barracks as did most of the other medics, with his sergeant telling them, “If the Army wanted you to have a wife, the Army would have issued you one.” Furthermore, what the Army expected of Mark at Fort Bragg was not very challenging. He served in a pool of medics where each morning, he was assigned to a unit requiring a medic for whatever training activities they were conducting that day. It was not the military experience Mark expected.

Sometimes Mark’s assignments took him out in the field with units on weeklong training exercises. During one such exercise, at about eleven a.m., a jet whizzed by low overhead, breaking the sound barrier and creating a massive sonic boom. The boom startled everyone, shaking everything nearby. The next day, the same thing happened, causing Mark to look over his shoulder every morning around 11:00 in expectation of another sonic boom ready to scare the daylights out of him. Every morning they came, just like clockwork, fraying Mark’s nerves.

On another occasion in the field, a soldier reported to Mark for sick call. Mark had three medications he could dispense, one in a green bottle, one in blue bottle, and one in a red bottle. By accident, he gave the soldier the wrong medication and the soldier spit it out declaring it tasted terrible. Mark then gave him the correct medicine and the soldier left. Mark was afraid the soldier might report him but he never did. Not surprisingly, the soldier never came back to sick call.

On one last occasion, a jeep drove by where Mark was working and he waved to the jeep’s passengers. Unfortunately, there was a colonel in the jeep who thought he deserved a salute from Mark rather than a wave. To help drive home the point, Mark was instructed to dig a large hole, which he did. After that, Mark didn’t wave at any more jeeps passing by.

When Mark had liberty, he enjoyed spending time in Fayetteville. On paydays, he and a friend met at an Italian restaurant for a nice dinner. On one payday when his friend couldn’t meet up with him, Mark went to a bar to grab a beer. There he saw an older gentleman with white hair, dressed in a sport coat and having a drink. The gentleman saw Mark, too, and started a conversation. He introduced himself as Tommy Bartlett, an entertainment celebrity who ran water skiing and skydiving shows in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. Upon learning Mark was airborne qualified, Tommy told Mark if he ever visited Wisconsin Dells, he was welcome to jump out of planes there. This was Mark’s one brush with a celebrity during his hitch in the Army.

In the spring of 1967, Mark was unexpectedly transferred to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he joined Charlie Company of the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division. Even more unexpected, he and his unit were slated to go to Vietnam. And, due to a clerical error where someone mistakenly recorded his MOS (military occupational specialty) as 11B – infantryman rather than 91B – medic, he was issued an M16 and assigned duties as a rifleman rather than as a medic. The Army eventually caught the error and offered Mark the opportunity to revert to medic if he wanted, but since he had been training as an infantry soldier at Fort Campbell, he decided to stick with it. Accordingly, on December 4, 1967 – his sister’s twenty-first birthday – he and the rest of the 3rd Battalion boarded military transport planes and started the long journey to Vietnam dressed in their military fatigues and carrying their M16 rifles, ready for action. They made three stops along the way, the highlight being a 4:00 a.m. breakfast in Manila in the Republic of the Philippines. Then it was back on the planes until they arrived in Vietnam.

Once in South Vietnam, the 3rd Battalion deployed to its new base camp at Phước Vĩnh, located about forty-five miles northeast of Saigon. There they were joined by the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 506th Infantry, also part of the 101st Airborne Division. Once there, Mark’s first assignment was to fill sandbags and stack them around his barracks for protection from shrapnel and bullets in the event of an enemy attack. Then, after a short acclimation period, Mark’s platoon helicoptered to a landing zone where they were dropped off to patrol the surrounding area in search of Viet Cong. This turned out to be a typical mission, with Mark’s platoon or his company often being in the field up to two weeks before returning to the base camp to decompress and resupply.

Although Mark went on numerous patrols during his time in Vietnam, his platoon never engaged in a traditional firefight. Instead, Viet Cong guerrillas approached Mark’s unit under the cover of the jungle, fired at them, and then fled. As a result, Mark never knew when or where the enemy might be taking aim at him. Every step he took could be his last. Only once did he actually see a small group of Viet Cong firing at his platoon. They barely had the chance to return fire before the group disappeared. On another occasion the platoon came close, finding an abandoned Viet Cong camp with warm rice and tea right where the enemy left it before slipping away into the jungle. Faced with such hit and run tactics, Mark and the other members of his unit had to remain alert at all times – their lives depended on it.

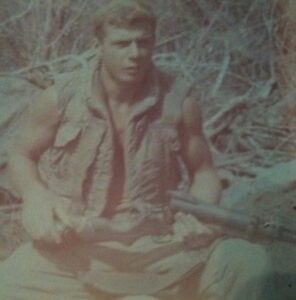

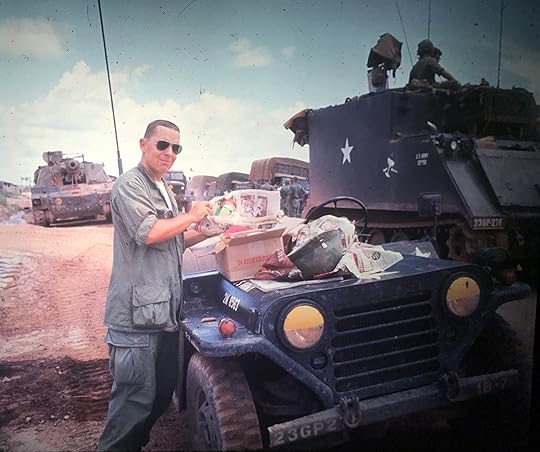

Mark Myers with an M79 grenade launcher – he carried the M79 during the latter part of his tour

Mark Myers with an M79 grenade launcher – he carried the M79 during the latter part of his tourThe enemy wasn’t the only danger Mark had to be wary of. After securing a perimeter to bed down for the evening while out on patrol, Mark was standing next to a soldier armed with an M79 grenade launcher. Without warning, the soldier inadvertently fired the weapon, launching a grenade into the ground just inches from where Mark stood. Fortunately, the grenade had a safety feature that required it to rotate a certain number of times before it exploded, and it did not have time to reach that threshold before it stuck in the jungle floor. Had it gone off, Mark certainly would have been killed.

During another patrol where Mark’s platoon was acting as an ambush unit, a call went out for artillery support. The first round missed the target, so the forward observer gave correcting instructions. Someone somewhere made an error and the second round fell near Mark’s platoon leader and medic. Mark heard the artillery round screaming overhead and took cover just in time. He was covered by leaves from the blast. The man next to him wasn’t so lucky as he was hit by a piece of shrapnel and the platoon’s medic was killed. It was a horrible night Mark will never forget.

On another night nearer the end of his tour, Mark and three or four members of his squad went outside the perimeter of the base camp to set an ambush. Once in position, they each dug a fox hole for protection and then set their weapons out in front of them so they could easily access them in the event the enemy wandered into their trap. When a new soldier next to Mark set out his grenades, Mark noticed he had straightened the grenades’ safety pins making it possible for them to slip out, allowing the grenades to detonate. When Mark told him not to do that, the new soldier told him “Don’t tell me what to do.” The next day, the same new soldier had point and was carrying his M16 at his hip, parallel to the ground with a round chambered and the safety off. When he turned around, his weapon discharged, narrowly missing Mark and the soldier following behind him.

Despite these two clear safety violations, the patrol made it back to the base camp at Phước Vĩnh and resumed their normal duties. That night, while Mark and three others stood watch in a guard tower on the base perimeter, they heard an explosion in the vicinity of the barracks. They soon learned the explosion was not caused by an enemy mortar, but by an accidental detonation of one the grenades carried by the new soldier who had straightened the safety pins despite being told not to do so. Not only was that soldier killed, but another soldier in the barracks near where the new soldier was standing was also killed. It was a tragic incident that never should have happened.

Aside from the danger, going out on patrol was physically demanding. Mark’s rucksack weighed so much from the supplies he needed to carry to survive in the jungle for five or more days, he couldn’t pick it up and put it on. Instead, he set it on the ground and worked into it there, then had to try to stand up with it on his back. During one patrol in particularly hot weather, a tall soldier from California was overcome by the heat and had to be medevac’d by helicopter. Rather than send his rucksack back with him, the platoon sergeant asked for a volunteer to carry the pack with its extra supplies in case they might need them. Thinking if he carried the pack, he might be overcome by heat too and get to go back to the base camp, Mark volunteered. His plan didn’t work and he ended up carrying the rucksack for the remainder of the patrol.

During patrols in Vietnam’s intense heat, water was more valuable than gold. Typically, Mark carried up to a gallon of water split between several canteens. This was usually enough to hold him until a helicopter could resupply the unit with water (and newspapers and candy) in the field, but sometimes the helicopters could not reach them in time. When that happened, they had to find another source of water. Once when the platoon ran out of water, Mark found a bomb crater filled with green and brown water so dirty he would not otherwise have gone near it. Now parched with thirst, he filled his canteen with the nasty water and added an iodine pill to purify it. He then had to wait twenty minutes to allow the pill to do its work. After seventeen minutes, Mark figured he’d waited long enough and drank the water, barely keeping it down. Fortunately, the pill did what it was supposed to and he did not get sick. Not much later, the resupply helicopter arrived with fresh water.

Mark Myers taking a break during a patrol in Vietnam

Mark Myers taking a break during a patrol in VietnamAfter a while, Mark developed a routine on patrol. In the evening, the platoon formed a circular defensive perimeter, with each man taking a position about ten meters from the next. Each man then dug a foxhole to bed down in for the evening. Mark always spread out his poncho in the fox hole first, then sat down on it with a hot cup of coffee, three cookies from his c-rations, and music from the Armed Forces radio station in Saigon. One night as he mellowed to the music in his own little world, a shot rang out and Mark instinctively dove for cover, crushing his cookies and spilling his coffee. For the rest of the evening, he had to fight off the bugs crawling into his fox hole trying to abscond with the cookie crumbs he could not get rid of in the dark.

Mosquitoes also posed a hazard because they carried malaria, but red fire ants were Mark’s true nemesis. Whenever shots rang out and he dove for cover, he often found himself popping back up because of painful fire ant bites. The ants were so numerous, sometimes the normally green leaves in trees a quarter of a mile away appeared reddish-green because they were crawling with so many ants. One time Mark caught a fire ant in some rubber tree sap and tried to kill it with a match. Instead of dying, the ant fought with the flame until it extinguished the fire, giving Mark all the more reason to fear the painful pest.

Leaches were another menace, particularly when Mark patrolled through rice paddies. Normally, everyone walked on the berms outlining the rice paddies, but sometimes they had to trudge through the water. Somehow, Mark avoided the leach scourge until his final patrol, when he was serving as point man on a mission through the jungle. When they stopped to take a break, he removed his boots and found a leach attached to his foot just above his big toe. He sprayed it with mosquito repellent and it fell off, providing yet another reason why he could not wait to leave Vietnam.

Sometimes patrols brought unexpected surprises. One day when Mark’s platoon was forging its way through tall elephant grass, they detected someone heading in their direction. Instinctively, they took cover and prepared to defend themselves. When the approaching group finally became visible, it turned out to be five or six bare-breasted Montagnard women carrying large jars of water on their heads. Without an ounce of fear, and despite seeing Mark and the other soldiers pointing weapons in their direction, the women carried on with their chore, smiling broadly as they walked by. The Montagnards were a fiercely independent indigenous people often allied with U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. Unfortunately, they were also extremely poor. When Mark’s platoon buried their empty c-ration cans and boxes in the jungle to keep them from giving away their position, Montagnard children living nearby often dug them up in search of something to eat or to shore up their ramshackle huts.

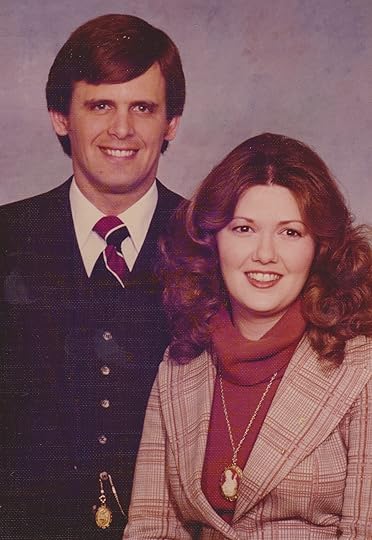

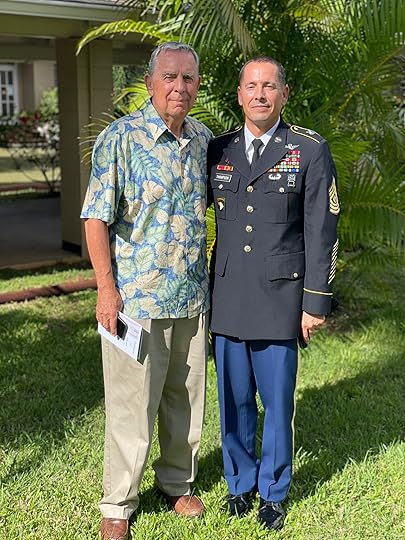

Mark and Linda Myers at their wedding

Mark and Linda Myers at their weddingWhen Mark wasn’t patrolling in the field, he was back at the base camp in Phước Vĩnh. There he did lots of reading, wrote letters, and occasionally grabbed a beer at the enlisted man’s club. All the club’s empty beer bottles then had to be broken in two the next day using a trenching tool to prevent the Viet Cong from turning them into weapons like Molotov cocktails. Mark also had to stand duty guarding the base perimeter and perform latrine duty, which was particularly nasty. This involved taking the fifty-five-gallon drums filled with raw sewage from under the latrines and burning the contents with diesel fuel. The only bright side of the duty was it didn’t take long to get the fire started, so it gave him time to relax until the drums’ contents burned away.

Mark finally reached the end of his tour in Vietnam in August 1968. Although Army tours in Vietnam were normally one year, Mark was able to depart after just over eight months because his two-year service obligation was set to expire on August 25. In addition, while he was in Vietnam, he wrote Aurora College and asked if he could be re-admitted, which they approved. When the Army saw this, they scheduled Mark to be discharged two weeks early so he could begin the fall semester at Aurora College on time.

To put this plan into place, Mark departed Vietnam on August 8, 1968, returning safely to the United States in San Francisco. He was honorably discharged as a Specialist 4 (E-4) two days later, on August 10, giving him just enough time to return to Aurora College in Illinois to begin classes. This time, he had over $2000 in savings from his time in the Army and his GI Bill benefits to help offset the costs of attendance. He also returned part time to his cement contractor construction work, eventually partnering with a friend to start their own company.

In 1976, Mark attended a party his mother threw for an exchange student she was hosting from Japan. Across the living room, Mark saw a pretty girl, Linda Nease, standing in between her mother and father. He summoned up his courage and, with Linda’s mother and father listening to every word, he asked Linda if she would go out with him. Linda’s mother fully supported Mark’s request because she approved of Mark’s family. Linda’s father did not because Mark was twenty-nine and Linda was just nineteen. Linda’s father had the final word that night, but Mark did not give up. He called the director of nursing at the hospital where Linda worked and left a message asking for Linda to give him a call. She did and the two began to date.

Mark’s work commitments made earning his college degree difficult. In pursuit of needed academic flexibility, he enrolled in a number of programs, including at the Illinois Institute of Technology, the University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, and Control Data Institute, before he finally graduated from Aurora College with a bachelor’s degree in accounting in 1978. Two years later, an even more significant event occurred – he married Linda Nease. In 1994, they moved to Palm Harbor, Florida, after realizing the Sunshine State’s climate would be a better fit for Mark’s concrete construction business. They also started a home inspection business, with Mark conducting the inspections, although he occasionally employed other trained home inspectors to assist him. Linda ran the business, so she could be there for their growing daughter and son and all their activities and schooling. They finally retired in 2015 but still keep busy with their two children and six grandchildren, who all live nearby. Mark also continues to deal with the fallout from exposure to Agent Orange during his time in Vietnam.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army, for his distinguished service during the Vietnam War. Drafted in 1966, Mark challenged himself as a medic, a paratrooper, and an infantryman, doing whatever it took to allow him to serve in Vietnam. Once there, he performed his duties under fire with courage and commitment, patrolling the jungles of Vietnam in search of a determined foe. For all he has done, and for the effects of the war he continues to endure, we thank him for his service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Mark’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

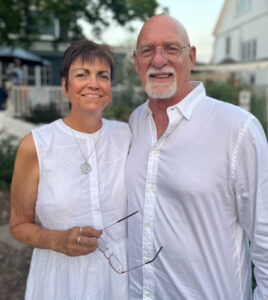

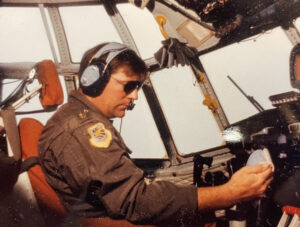

Mark and Linda Myers

Mark and Linda Myers The post Specialist 4 Mark Myers, U.S. Army – Three Things to Count On first appeared on David E. Grogan.

January 17, 2024

SK2 Donald A. Chivas, U.S. Navy – Father Knows Best

Since time immemorial, children grow up and leave their parents, seeking to chart their own way. For most, that means learning life’s lessons the hard way as they find it difficult to accept their parents’ advice, even though their parents walked in their shoes not so many years before. Storekeeper Second Class Donald A. Chivas, U.S. Navy, bucked the trend and listened to his father, realizing his father’s wisdom could help him navigate a pivotal fork in the road. The result changed Don’s life forever. This is his story.

Don’s father, Norman Chivas, served in the U.S. Army and fought in France during World War II. After the war, he took a job in the maintenance department at a hospital in Detroit. There he met a medical technician, Shirley Myers, who also worked at the hospital. They married and had three children including Don, who was born in April 1946.

When Don was in the third grade, the family moved to Naperville, Illinois, then a small suburb west of Chicago. Don attended Naperville public schools, enrolling in Naperville Community High School (now Naperville Central High School) as a freshman in 1960. He loved sports, and as a big kid, excelled at football, wrestling, and track field events like shotput and discuss. He also was an accomplished clarinetist, having chosen the instrument in middle school because the prettiest girl in his class played clarinet, too. He stuck with it all the way through high school, not only playing in his high school band, but also playing the bass clarinet as a member of the Naperville Municipal Band. As if sports and music weren’t enough, Don worked at the Container Corporation of America in the carton department, shaking printed sheets to help them dry and loading them onto pallets for shipment.

Don graduated from Naperville Central High School in the spring of 1964. In the fall he began classes at Wisconsin State University – Platteville studying mining engineering. He had a lot of fun in Platteville, perhaps a bit too much, because after three years, the university informed him he had not made sufficient progress to continue his studies. Dejected, he went home to tell his father he needed to find another career path.

Don’s father could see the writing on the wall. Every day the newspapers carried headlines from the Vietnam War and with Don no longer eligible for the college deferral from the draft, he knew Don would soon receive his draft notice. Having served in combat in France, he also knew what lay ahead for Don, so he encouraged Don to choose his own destiny by enlisting in the Navy before Uncle Sam chose it for him by drafting him into the Army or Marines.

Don heeded his father’s advice and marched to the nearest Navy recruiting center. When the Navy recruiter asked him what job he wanted to do, Don told him since he had three years of college in mining engineering, he wanted to be in the Navy Construction Battalion, better known as the Seabees. The recruiter said, “the Seabees it is” and Don signed the four-year enlistment contract on the spot. When he got home, his father was waiting for him waiving an envelope. Unbelievably, Don’s draft notice had arrived in the mail that same day. Had he not already enlisted, he would have been drafted into the Army or Marines and on his way to Vietnam.

When it came time to report to boot camp in September 1967, Don boarded a train for the short sixty-mile trip to Naval Training Center Great Lakes, just north of Chicago. As a big guy of over 200 pounds, Don really had to work at boot camp’s physical training, especially running because he could not run far or fast. What he could do was play the clarinet, qualifying him for the recruit band. This allowed him to trade the two-week service portion of his training for time in the band, which he really enjoyed.

USS Sabine (AO-25) – Source: U.S. Navy

USS Sabine (AO-25) – Source: U.S. NavyBoot camp lasted eight weeks and then it was time for Don’s first assignment. Instead of the Seabees as the recruiter promised, Don received orders to report to the USS Sabine (AO-25), a World War II oiler commissioned in December 1940 and homeported in Mayport, Florida. The Sabine had a storied past, including serving in the task force that launched the Doolittle raid on Tokyo in 1942. Don arrived onboard as an undesignated seaman, meaning he didn’t yet have any job specialty and would have to find one after he gained experience as a sailor. Like most undesignated seamen, he was assigned to the deck department, working hard with other new sailors to maintain the ship and its deck equipment and lifeboats. Deck maintenance work was never ending on Sabine, not only because the ship was nearly thirty years old, but also because of its constant exposure to salt water. Without proper maintenance, the ship would succumb to rust and corrosion. As a result, Don spent his time chipping off old paint from the hull and deck and repainting the surfaces to protect them from the elements.

Don also learned basic seamanship skills each time the Sabine got underway off the east coast of the United States. When the ship conducted gunfire exercises, Don and the other new sailors in the deck department went outside to watch the ship’s big 5-inch/38-calibre guns fire away. The noise was so loud, though, it continues to affect his hearing to this day. Looking back, Don wishes the Navy had provided him and his fellow sailors with hearing protection, both during his time onboard Sabine and subsequently during the small arms training he received, so he would not now be suffering from impaired hearing.

During one underway period in August 1968, the Sabine crossed the equator heading southward for a port call in Rio de Janeiro. Because crossing the equator is a significant event in any sailor’s career, Don participated in the traditional “Crossing the Line” ceremony, where uninitiated new sailors like Don, referred to as “pollywogs”, become experienced “shellbacks”. Don earned his “shellback” status after completing the ceremony and then had a great time in Rio, although he was disappointed to learn he could not practice the Spanish he had learned in school because the people in Brazil spoke Portuguese.

By the fall of 1968, the Sabine had reached the end of her illustrious career. In October, she sailed from Mayport to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard to be decommissioned. This was a busy time for Don, as he and the other members of the deck department had to unload essentially everything from the ship that wasn’t welded in place so the ship could be mothballed. The work was grueling even for someone as big and strong as Don, and he injured himself carrying fifty-pound CO2 canisters off the ship. After two-weeks bed rest, he was back in action to finish the job. The Sabine’s last chapter closed on February 20, 1969, with the ship’s decommissioning.

USS Suribachi (AE-21) – Source: U.S. Navy

USS Suribachi (AE-21) – Source: U.S. NavyOnce his work on Sabine was complete, Don reported to another ship homeported in Mayport, the USS Suribachi (AE-21). The Suribachi’s mission was to keep the Navy supplied with ammunition anywhere in the world. Just as he had done on the Sabine, Don started working in the deck department. However, after some time onboard, he met a Second Class Storekeeper (abbreviated SK2) working in the ship’s supply department. The Petty Officer told Don he would make a good SK and Don agreed, so he began “striking” to become an SK. Don was a natural for the SK job field, referred to as a “rating”, especially because his aunt had taught him how to type. That meant he could prepare requisitions and inventory records without having to hunt and peck for the right keys on the typewriter. He did so well, he promoted to SK3 (Storekeeper Third Class) while onboard the Suribachi.

Although the Suribachi was homeported in Mayport, it spent most of the first four months of 1969 in Mobile, Alabama, in overhaul, including some drydock time. The ship finally came out of the yards in May. Over the next few months, Don spent time underway in preparation for the ship’s upcoming December deployment to the Mediterranean Sea. The underway periods allowed Don to gain valuable experience as a Storekeeper and to visit places like New York City, Philadelphia, Ocho Rios Jamaica, and Guantanamo Bay Cuba, when the Suribachi pulled into port. He especially enjoyed Guantanamo Bay because he was able to visit a high school friend stationed there.

As the time for Suribachi’s Mediterranean deployment drew near, the ship’s captain received notice that the Navy needed him to release four sailors for duty in Vietnam. To Don’s surprise, his name was on the list. That meant instead of deploying to the Mediterranean Sea in December with the rest of the crew, Don headed to Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek in Virginia Beach, Virginia, for survival training and physical conditioning. He also spent time in the classroom and trained on weapons to ensure he was prepared for his new assignment in a war zone.

Don completed his training at Little Creek in January 1970 and boarded a military flight to San Francisco. Another military flight took him from there to Saigon, where he arrived on February 4, 1970. He had been told because he had three years of college, he might be assigned to Vice Admiral Elmo Zumwalt’s staff at Naval Forces Vietnam, which commanded a fleet of Navy swift boats operating along the coast and on the rivers in South Vietnam. Instead, he was issued an M16 without ammunition and sent to the Navy base at An Thoi on Phu Quoc Island off South Vietnam’s southwest coast in the Gulf of Thailand.

Don worked on a non-self-propelled barracks barge called Auxiliary Personnel Lighter Thirty (APL-30) which was tied up to the piers at the Navy base. The barge’s mission was to provide berthing and meals for the crews of the coastal swift boats, known as Patrol Craft Fast or “PCFs”, that operated from there. The PCFs departed each day on their missions patrolling the Vietnamese coast and then tied up to the barge at night so the crews could get a hot meal and bed down for the evening. Don, who was now a Storekeeper Second Class (SK2), was responsible for keeping the barge and the PCFs supplied with the food and other supplies they needed to get their jobs done. He even arranged for some movies to be shown to the PCF crews in the evenings after they returned from their missions. As he had seen the PCFs come back with bullet holes in them and evidence of American casualties, he knew just how important it was to support the sailors taking the fight to the enemy.

Coastal swift boats weren’t the only forces operating out of An Thoi; U.S. helicopters did so as well because the base had a 4,000-foot asphalt runway. Occasionally, the aircrews offered Don a ride and he got to fly on their missions. The rides provided a break from Don’s normal routine, but sometimes they proved a little too exciting if the helicopter got tasked with rocketing a Viet Cong target.

Part way through Don’s assignment, the Navy turned over responsibility for the coastal patrols to the South Vietnamese. Rather than turning over Don’s barracks barge as well, the Navy towed it to the swift boat base at Cat Lo, located sixty miles from Saigon on Vietnam’s southeast coast. Don performed the same support functions at Cat Lo that he did at Phu Quoc, except now the crews he assisted belonged to riverine patrol boats. These boats patrolled the Mekong River Delta to disrupt Viet Cong operations and frequently came under enemy fire.

Don’s one year tour in Vietnam ended in February 1971. He departed just as he had arrived, on a flight out of Saigon. As he prepared to board the plane, he mentally said goodbye to Vice Admiral Zumwalt, whom he never got to meet during his tour. Then he flew back to San Francisco and prepared to serve his final six months in the Navy.

When Don had six months left to serve of his four-year enlistment, the Navy offered him an early out option which he readily accepted in March 1971. This worked out well because while he was in Vietnam, he had written Wisconsin State University – Platte and asked to be re-admitted now that he had a more mature outlook toward his studies and his future. The university granted his request, allowing him to enroll in the fall 1971 term. As he had before, Don pursued a degree in mining engineering.

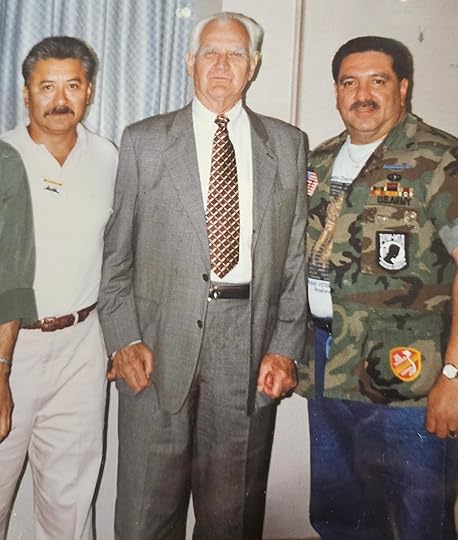

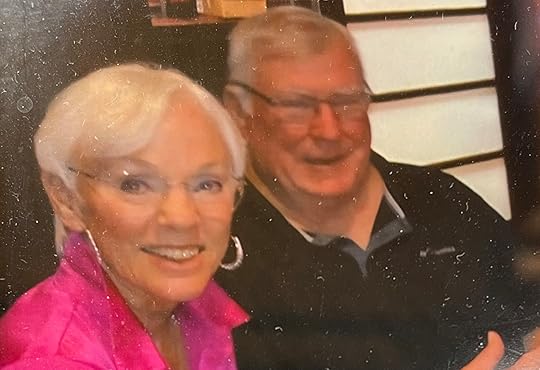

Don and Ginny Chivas

Don and Ginny ChivasThis time, Don’s educational plans worked out. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin – Platte (the university had changed its name) in May 1976 with a Bachelor’s degree in Mining Engineering. Better still, he used his GI Bill benefits to pay for his education and continued in the Naval Reserve until he graduated. After graduation, he went to work for the AMAX Coal Company in Terre Haute, Indiana, as part of a survey crew. From there he went to the Manley Brothers sand company, helping process sand from the Lake Michigan coastline. He finally found the job he was looking for when he went to work for his father as a manufacturer’s representative selling metal detectors and other equipment to the food industry, certifying their equipment’s status, and even repairing their equipment in the field. He continued in this role until he finally retired in 2022.

The other post-Navy event of lasting significance in Don’s life was his marriage to Virginia Ann “Ginny” Wolf in 1981. They have one son and are enjoying retirement together in Naperville, as Ginny retired from the family’s business at the same time Don did. Now as Don looks back over his Navy service, he is thankful his father channeled him in the Navy’s direction before his draft notice arrived. His father’s advice truly shaped the rest of Don’s life.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Storekeeper Second Class Donald A. Chivas, U.S. Navy, for his distinguished service onboard two Navy warships and for his tour of duty in Vietnam. The hallmark of his efforts was his support to the fleet, always giving the warfighters what they needed to successfully carry out their missions. We thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Don’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Don Chivas

Don Chivas The post SK2 Donald A. Chivas, U.S. Navy – Father Knows Best first appeared on David E. Grogan.

December 20, 2023

STG2 David S. Fones, U.S. Navy – Plan for the Worst, Hope for the Best

It’s easy to measure success in a basketball game or a race. Just look for the team with the most points or the runners with the fastest times. But what if your job is to be incredibly prepared for something you hope will never happen? Such was the case with Sonar Technician Second Class David S. Fones, U.S. Navy. He spent six years training to hunt and kill adversary submarines, ever vigilant and always ready to be called to action but hoping he never would be because it would mean the world was at war. Yet with all this responsibility, he always served as a positive ambassador for the United States in every foreign port his ships called. This is his story.

Dave was born into a family with a proud military heritage. Both of his grandfathers served in combat in Europe during World War I, while his father, Ted Fones, served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War II. He was a navigator on a bomber and flew twenty missions over Japan, serving as the lead navigator on seventeen of those missions. After the war, he used his GI Bill benefits to enroll in Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, a small city located about 170 miles southeast of Chicago, to study engineering.

One other thing Ted Fones did during the war was marry Melba Mae Simpson, his high school sweetheart. She worked as a switchboard operator for the local telephone company until Dave was born in August 1948. That meant Dave’s father had to get a job to support his growing family while still studying at Bradley, so he began working for Caterpillar Inc., a heavy equipment manufacturer headquartered in Peoria. Ultimately, he graduated with his engineering degree and rose to the level of Caterpillar’s Director of Research.

Dave’s parents sent him to Catholic schools, including his all-boy high school, Spalding Institute in downtown Peoria, where he began his freshman year in the fall of 1962. Although he ran varsity cross country, he loved playing pick-up basketball games and became quite good. His focus, though, was his grades and he excelled academically. So much so that after he graduated from Spalding Institute in June 1966, he enrolled in Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and began attending classes in the fall.

At Marquette, Dave got involved in Navy ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps), a university-level training program designed to qualify participants to serve as commissioned officers in the U.S. Navy. One of the areas he learned about was anti-submarine warfare, which really interested him. This also caused him to think about how the Navy might help him pay for his college education. Because his father was an engineer with Caterpillar, Dave did not qualify for financial aid. That made paying for Dave’s education at a private university like Marquette a strain on the family’s finances, especially since Dave’s parents were still raising his younger brother and younger sister. Accordingly, Dave decided to enlist in the Navy after completing his first year at Marquette so he could use the GI Bill to pay for his education.

Dave followed through with his plan, enlisting for six years in September 1967 at the height of the Vietnam War. After passing his physical and swearing to support and defend the Constitution, he boarded a train in Bloomington-Normal and headed off to boot camp at Naval Training Center, Great Lakes, just north of Chicago. When he and the other new arrivals were divided into companies, Dave was surprised to hear the name of a grade school friend, Rick Heiser, assigned to his company, too. At least he would not be going through the boot camp ordeal alone.

Much to his surprise, Dave did not find boot camp difficult. He already had a crew cut, so the Navy barbers got little satisfaction from the buzz cut they gave him on the first day of training. He had also attended Catholic schools all his life, so it was easy for him to trade the shirt and tie he wore to school each day for a Navy uniform. His Catholic schooling also imbued in him the necessity of following rules, taking the shock of that aspect of boot camp away, too. Finally, he was in great shape and a good swimmer, so he had no problems with the physical training. All this translated into a successful boot camp experience.

Boredom proved to be Dave’s biggest challenge. He found the military adage “hurry up and wait” to be true because in between training activities, he and the other recruits had nothing to do. To remedy this, Dave sent his parents a letter asking them to send him paperback books he could tuck into the back pocket of his dungarees. Then when his company had to sit around and wait, he could pull out a book and read. The solution worked so well Dave vowed he would never be bored again. For the rest of his time in the Navy, he kept a book in his back pocket to call upon when things got slow. Other things that kept Dave from getting bored at boot camp included winning the recruit basketball tournament with his company and standing watch outside in the cold guarding a garbage dumpster to keep enemy spies from stealing anything from it (or so the watchstanders joked among themselves).

Seaman Apprentice Dave Fones

Seaman Apprentice Dave FonesAfter Dave graduated from boot camp in the late fall of 1967, the Navy put him on the path to becoming a Sonar Technician (abbreviated “STG” for Sonar Technicians serving on surface ships). His first stop was basic electronics “A” school, also located on board Naval Station Great Lakes. Once he had basics down, he transferred to Naval Station Key West in Florida to attend “B” and “C” schools, where he learned how to listen for, identify, and track submerged enemy submarines using sophisticated sonar equipment. He also learned how to program, maintain, repair, and operate a bulky fire control computer to calculate the firing solutions his ship needed to launch weapons to destroy any enemy submarines lurking nearby. Dave described his job as always being ready for the worst in case he was called upon to locate and destroy enemy submarines, but hoping for the best and that war would never come.

As a tropical paradise, Key West offered distractions from the weighty training Dave engaged in during the normal workweek. On weekends when they had liberty, Dave and a friend explored the warm waters of the Caribbean searching for Langosta “spiny” lobsters. They took their catch to the Enlisted Club on base and the cooks prepared the lobsters for free. Dave also played basketball, with his team winning the base championship, and he enjoyed swimming at the base pool at the end of the workday. Still, life at Key West wasn’t all training and fun, especially before the start of each school. During those interim periods Dave and the other sailors waiting for classes to begin did janitorial work, mopping floors, stripping wax from the floors, and then rewaxing them. It was a small price to pay for living in Key West.

After graduating from Sonar Technician “C” school in the summer of 1968, Dave transferred to his first ship, the USS Robert H. McCard (DD-822), homeported in Charleston, South Carolina. The McCard was a destroyer commissioned in October 1946, a year after the end of World War II. Although it had been built at a time when German and Japanese submarines were the ship’s intended targets, McCard’s ability to detect and track Soviet submarines, and destroy them if necessary, made the ship a critical component of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. Given Dave’s newly earned expertise in operating the sonar equipment underlying the ship’s warfighting capabilities, he immediately became an essential member of the ship’s crew.

Dave reported for duty on the McCard’s quarterdeck around 3:00 a.m. The duty section checked him in and assigned him to the top rack in the corner of his new division’s berthing spaces. Because it was so early in the morning, no one in his division knew he was there so they did not wake him up in the morning. He woke up later on his own, feeling very seasick. He tried to find a head (the Navy’s term for a bathroom) but didn’t know where one was. He started to climb up a ladder to get out of the berthing compartment but threw up before he could leave. At that point he decided the best thing he could do was go back to his rack to sleep until he felt better. He was awakened not long after by a call reporting someone had thrown up on everyone’s clothes in a laundry basket. Just a few hours on board and he’d already left his mark.

Dave’s primary responsibility when he first reported onboard involved conducting preventive maintenance under the watchful eye of an experienced First Class Petty Officer (E-6). This meant performing certain daily, weekly, and monthly checks on the sonar and fire control systems to ensure they were always in working order and prepared for war. The experience he gained soon made him an expert on the ship’s sonar equipment and its Mark 114 underwater fire control system. In fact, Dave had enlisted for six years to obtain his advanced “B” school and “C” school training right after “A” school. Other new sailors in his division had enlisted for only four years, so they did not have the same advanced training. It was Dave’s job to train them to conduct the required preventive maintenance on all their gear.

The Navy tested Dave’s expertise when the Robert H. McCard left Charleston to participate in NATO exercise Silvertower in the North Atlantic during September and October 1968. The North Atlantic seas proved treacherous, battering Dave and the rest of McCard’s crew throughout the exercise. At one point, a helicopter approached the ship with supplies but had to turn away because it was too dangerous to attempt a transfer. The rough seas also made it difficult to keep the ship’s sonar equipment calibrated, requiring Dave to spend countless hours working to maintain its operational readiness. Even the ship itself was damaged, so at the end of the exercise, it had to put in at Portsmouth, England, for repairs. This worked to Dave’s advantage because as a reward for the work he’d done during the exercise, he was granted leave in London. While there he took in all the major sites, including the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace, and Trafalgar Square, as well as Lord Horatio Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory, in Portsmouth harbor.

Dave returned to Charleston on the McCard, which then went into the shipyards for an overhaul from December 1968 to April 1969. While the ship was in the yards, the fire control computer Dave worked on had to be replaced. Given the computer’s mammoth size, shipyard workers had to cut a hole in the deck above the computer. Then a crane lowered four hooks at the end of wire ropes to connect to four big eye bolts on the top of the computer console. Dave labeled and disconnected all the computer’s wiring so it could be reconnected to the replacement unit. Finally, the crane hoisted the computer out of the ship and onto a waiting truck. The process was reversed when the replacement unit arrived a few days later.

After the yard period, the McCard began workups off the U.S. Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean in preparation for an upcoming deployment to the Mediterranean Sea. This training period gave Dave the opportunity to practice the sub hunting skills he’d learned at “C” School, including using his sonar equipment to listen for submerged U.S. submarines making practice attacks against U.S. Navy surface vessels. The job was part skill and part art, as Dave had to calibrate both the equipment and his ears to discern whether a submerged submarine was approaching his ship, departing the area, or heading on a parallel course. Then he worked closely with those manning the ship’s weapons – torpedoes and ASROCs (anti-submarine rockets) – to successfully simulate an attack on the submarine. Data extracted from the dummy weapons used in the simulation measured Dave’s success. In the event of war, his success would be measured instead by the lives he saved from an attack by an enemy sub.

Once McCard and her crew completed their training requirements in the Caribbean and made port calls at area islands for some much-needed stress relief, the ship returned to Charleston. Then, in September 1969, McCard got underway for a six-month deployment to the Mediterranean Sea, where it conducted operations with the ships of the U.S. Sixth Fleet.

Dave and the McCard returned to Charleston on March 28, 1970, after completing their Mediterranean assignment. Later that year, the ship began the workup cycle again, training off the Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean to prepare for yet another deployment to the Mediterranean Sea. This time, Dave and the ship left Charleston on April 15, 1971, and returned on October 16, 1971, completing Dave’s second sixth-month deployment in less than two years.

USS McCard (DD-822) in 1968. Source: Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS McCard (DD-822) in 1968. Source: Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.During both “Med” deployments, the McCard made port calls in various allied countries, demonstrating U.S. resolve and capability during some of the tensest times of the decades long Cold War. Two examples illustrate the roles Dave and the McCard played in what often turned out to be a cat-and-mouse game at sea.

On February 3, 1970, the McCard was operating together with the light cruiser USS Little Rock (CL-92), when the Little Rock made sonar contact with a suspected submarine. The McCard was called in to prosecute the contact, with Dave’s team of Sonar Technicians taking center stage. The McCard conducted a simulated attack on the submarine, using it as a training event to hone its sub hunting skills. The reality of the situation came to light when a submarine’s periscope was sighted nearby.

On another occasion, intelligence reports indicated the Russian helicopter carrier Moskva would soon emerge from the Black Sea through the Turkish Straits. McCard was given the task of trailing her in the Mediterranean until she was relieved by another ship to continue the trail. As the intelligence report did not indicate exactly when the Moskva would emerge, McCard took station off the coast of Turkey and waited. After about a week, the Moskva appeared, and McCard shadowed the Soviet ship at a safe distance. While Dave found this exciting at first, the excitement wore off quickly when McCard started to run out of fresh fruits and vegetables and other supplies. While McCard was supposed to be relieved by another Sixth Fleet ship, conducting a turnover rendezvous was difficult because only the Moskva new where she was going. Eventually the turnover occurred, but not before Dave and the rest of the crew had eaten mostly powdered eggs and “bug juice” (generic Kool-Aid) for days.

The best parts about Dave’s two deployments to the Mediterranean Sea were the port calls McCard made and the countries Dave got to visit. These included stops in Spain, France, Italy, and Greece, with each country’s culture and history being older than the last. Dave particularly enjoyed his time in Greece, where two events stand out.

The first involved an excursion to tour Olympia, the site of the ancient Olympics in Greece. He rented a car to drive there himself, but missed a sign along the way telling him to turn right. After going some distance in the wrong direction across paved, then cinder, and then dirt roads, he came upon a family spreading grapes from their farm onto tarps to let the sun turn them into raisins, their primary cash crop. He got out of his car and asked the family if they could show him how to get to Olympia. The father of the family smiled – he had been a merchant seaman and not only spoke some English but had worked with Americans before. Plus, he saw this as an opportunity for his teenage daughter to practice the English she was learning in school with a real American. “Of course,” he said, “but you must stay and have dinner first.”

Thinking this would be a memorable experience, Dave returned with the family to their home, a small adobe hut with an awning covering an open front porch. Inside the hut was the kitchen and the place the family’s children slept, while the farmer and his wife slept on a brass bed on the open-air porch.

To prepare for dinner, the farmer sent his son and Dave to the nearby river to catch some fish and to bring back two beers he kept cool in the river. When they returned, they found the farmer’s wife preparing a fresh chicken. Dave ended up having a wonderful dinner with the family, experiencing Greek life in a way he never expected. When Dave was finally ready to go, he thanked the family and asked how to get to Olympia. The farmer replied they would get him on his way, but not until the next morning. That night, the farmer gave Dave the brass bed under the awning on the open-air porch, while the farmer and his wife slept inside with their children. The next day, they sent Dave off in the right direction after Dave bought them breakfast and said goodbye. He continued to correspond with the family for years afterwards.

The second experience involved a trip Dave made to the southernmost point on Greece’s Peloponnese peninsula. After touring the ancient Greek amphitheater in Epidaurus, he arrived in a coastal town around 9:00 p.m. to check into a family-run hotel where he had made reservations. He found the front desk manned by a teenage boy who told him they thought he wasn’t coming because it was late, so they had given his room away. Dave said he understood and left to find another room in town. As he started to drive slowly through the town’s streets, he saw a commotion in the rear-view mirror and children running after him. He circled back to see what was going on and learned the town’s families were arguing about who would get to host the tall American visitor. Needless to say, Dave had no trouble finding a place to stay that night.

Both these experiences occurred because of Dave’s approach to port visits. Using travel guidebooks he’d acquired along the way, he planned each visit to take advantage of every opportunity a country had to offer. He especially loved meeting local people and learning about their culture. For these two reasons, he considers his Greek experiences priceless.

USS Fiske (DD-842). Source: Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.

USS Fiske (DD-842). Source: Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command.After returning from his second deployment, Dave transferred from the USS Robert H. McCard to another Gearing class destroyer, the USS Fiske (DD-842). This meant moving north because the Fiske was homeported in Newport, Rhode Island. Dave’s duties onboard were essentially the same as those onboard the McCard, although now he was an experienced Sonar Technician Second Class (STG2). His expertise, however, extended well beyond sonar. The Fiske’s commanding officer recognized this by presenting Dave with a letter of commendation for the many hours he put in as a member of the ship’s ASROC handling team preparing the ship for its nuclear weapons acceptance inspection at the end of 1972.

Dave did one deployment onboard the Fiske, which began in January 1973. The ship was initially headed for the coast of Vietnam, but when it was announced on January 27, 1973, that all U.S. troops would be withdrawn from Vietnam within sixty days, the ship’s mission changed. Instead, after crossing the equator in the Atlantic Ocean and rounding the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, the ship headed north through the Indian Ocean to Pakistan.

During this cruise, the Fiske made two port visits that are especially memorable for Dave. The first was in Mombasa Kenya, where Dave finagled two weeks leave. Normally, leave for such a long period during a deployment was impossible, but the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) had recently released a memo saying too many sailors were being discharged with large leave balances, requiring the Navy to pay them for their unused leave on their way out. As Dave was scheduled to be discharged as soon as the ship returned to Newport, Rhode Island, and had a large leave balance on the books, he submitted the CNO’s memo with his third leave request, the first two having been denied. He was subsequently told to report to the captain’s office, where both the captain and the executive officer grilled him about his plans. Finally, they asked “what are you going to do if the ship’s schedule changes and you can’t get back to the ship before we pull out of port?” Ready for the question, Dave produced his credit card and said he could make the necessary travel arrangements to rejoin the ship later. Satisfied Dave had a plan and could handle himself, they approved Dave’s leave.

Dave’s photo of an elephant charging his vehicle during his safari in Kenya

Dave’s photo of an elephant charging his vehicle during his safari in KenyaAs a result of his persistence and planning, Dave spent two exciting weeks in Kenya. He started by taking a taxi with five other people to Nairobi, located 300 miles away. During the drive, he sat next to a professional photographer, who told him how to take pictures of animals in the wild. Dave put the lessons to good use during a safari, where he saw and photographed elephants, lions, giraffes, cheetahs, and zebras. One of the cheetahs even posed by laying on the hood of his Land Rover, apparently enjoying the engine’s warmth. Dave also saw lion cubs playing under the watchful eye of their mother and an alligator sunning himself on a flat rock. The alligator was invisible until his guide pointed it out and explained the danger alligators posed to villagers filling jugs of water along the river’s banks. In addition to the many photos he took, Dave hauled back to the ship a large shield and two spears he purchased in a remote village, all three items being used by young boys as part of their test to cross the bridge to manhood.

The other notable port call was in Massawa, Ethiopia (today Massawa is in Eritrea), where Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie came onboard the Fiske. The emperor inspected the crew while onboard, passing directly in front of Dave, who towered over him as the emperor was very small in stature.

The Fiske returned to its homeport in Newport, Rhode Island, in July 1973. By that time, Dave had less than ninety days to serve on his six-year enlistment, so he qualified for an early discharge. This he took in August 1973 after passing his discharge physical. He then loaded up his car and headed back to Peoria, Illinois.

Once back in Peoria, Dave used his GI Bill to pay for his college education, enrolling in Illinois State University in Normal, Illinois. While there, he met a dormitory management assistant named Ari who had a Greek accent. Dave asked him where he was from and Ari replied the southern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula in Greece. When Dave asked what he did there, he said he worked at his family’s hotel. Then, by incredible coincidence, they realized Ari was the teenage boy who told Dave they had given away his room at the hotel when he arrived later than expected after visiting the amphitheater in Epidaurus.

Dave and Susie Fones

Dave and Susie FonesDave met one other significant person at Illinois State, a graduate student named Susie. They fell in love and were married in 1977, the year after Dave earned bachelor’s degrees in Physical Education and Marketing Education. Since then, Dave has had a successful career in business and teaching, including coaching both tennis and basketball at the high school level. Moreover, he and Susie have two boys, one who followed in Dave’s footsteps by joining the military (Army) and the other who followed in Dave’s footsteps by becoming a teacher.

Dave and Susie are now retired, but Dave remains active, particularly in support groups helping people deal with serious health challenges similar to those he has experienced. In fact, Dave serves as an Ambassador for the Head and Neck Cancer Alliance, giving presentations to organizations about head and neck cancer to promote awareness and provide support for those suffering from the disease. In addition, he walks five miles every day and has covered 15,000 miles since he began in 2016 after his father died. He also speaks publicly about his military experience and that of his grandfathers, his father, and his son, reminding the public of what it means to serve.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sonar Technician Second Class David S. Fones for his dedicated service in the Navy from 1967-1973. Sailing on two destroyers across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, he maintained constant readiness to protect the fleet from adversary submarines. He went wherever and whenever the Navy called, putting his civilian life on hold and serving as an outstanding ambassador for America in every country he visited. We thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Dave’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The post STG2 David S. Fones, U.S. Navy – Plan for the Worst, Hope for the Best first appeared on David E. Grogan.

November 15, 2023

Sergeant Harold P. Jantz, U.S. Army – When Being Right Counts

Everyone understands soldiers follow orders. They must or their military organizations will devolve into chaos and fail. What makes the U.S. military unique, however, is it expects its soldiers to think and take the initiative, seizing opportunities that might otherwise be lost. Such was the case with Sergeant Harold P. Jantz, U.S. Army. When a far superior enemy force engaged his platoon during the Vietnam War, he charged into the fray and brought to bear the necessary firepower to defeat his foe. Without his quick thinking and forceful action, his entire platoon might have been destroyed. In the aftermath, he left no U.S. soldier behind. The events of that day were the defining moments of his life, molding him into the man he is today. This is his story.

Harold was born on Good Friday in April 1949 and spent his earliest years in North Merrick, a small town on Long Island, New York. He was one of six children and had four sisters and one brother. His father was a World War II veteran who served in the U.S. Army Air Corps in Italy, while his uncle “Doc” Jantz fought with the 82nd Airborne Division across northern Europe. After the war, Harold’s father and many of his relatives worked for the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation in Bethpage, providing his family with a solid middle-class income.

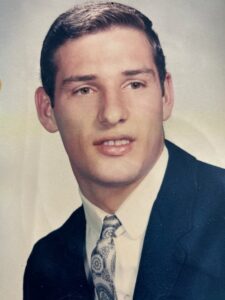

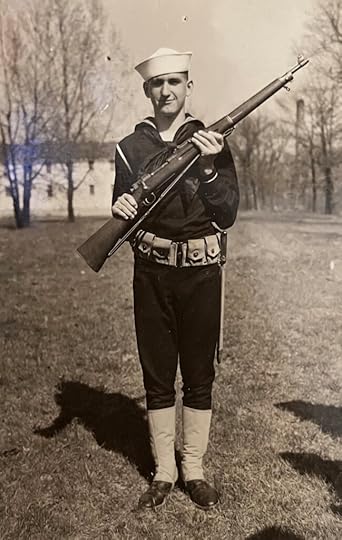

Harold’s high school graduation photo, June 1968

Harold’s high school graduation photo, June 1968When Harold was seven, the family moved a short distance to Bellmore, Long Island, putting down permanent roots. Harold attended Bellmore Public Schools, including his first two years of high school at Wellington C. Mepham High School. However, when the new John F. Kennedy High School opened its doors in September 1966, Harold transferred there to complete his last two years. He was an outstanding athlete, having played baseball, football, and wrestling at Mepham, but he especially excelled at football. His football coach at John F. Kennedy High School immediately recognized his athletic ability and leadership skills and made him the team captain for both his junior and senior years. Harold reciprocated by fully committing to football and dropping the other two sports.

Football wasn’t his only love in high school. During his junior year, he met Valerie Dvorak, who was one year behind him, and they began to date. Their relationship was straight out of a high school storybook – the football captain dating the prettiest girl on the school’s “kickline team”. They dated all through high school and continued even after Harold graduated in June of 1968.

With his diploma now in hand, Harold followed in his father’s footsteps and started working at Grumman. Defense contractors like Grumman needed lots of workers to keep America’s fighting forces in Vietnam supplied. However, America’s need for soldiers trumped Grumman’s requirements, as Harold found out when he received his draft notice in early 1969.

On May 17, 1969, Harold reported for service as directed by his draft notice. He and the other draftees from his region traveled by bus to Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, New York, where they were sworn in as the newest members of the U.S. Army. They then boarded buses enroute to Newark International Airport, where they caught a flight to Columbia, South Carolina. When they arrived, they again boarded buses, this time headed for Fort Jackson and Basic Training.

Harold’s induction into the U.S. Army began in earnest at Fort Jackson. He joined a host of other draftees in an in-processing assembly line that continued for three days. At one point early on, he waited in line in his civilian clothes to enter a building. When he emerged from the building at the other end, he was wearing an Army uniform and carrying a duffle bag full of gear. His civilian clothes, and his civilian life, were things of the past.

After in-processing, the real Basic Training began. Harold and his fellow draftees moved to worn out, beat up, World War II era barracks in an area known as “the hill”. They trained there during May, June, and part of July, baking in the South Carolina sun. Harold was assigned to Company C62, led by Sergeant Citron from Panama, who despite being only about 5’2”, was “tough as nails”. Word was he’d had two tours in Vietnam. If that wasn’t enough, he was also the Army’s lightweight boxing champion. He made it clear no one should mess with him and no one did because everyone was afraid of him. He also told them they were going to Vietnam, and he was going to make sure they were ready.

Sergeant Citron made good on his promise. Sometimes he would wake up Harold’s company in the middle of the night and have them “low crawl” under the nasty vermin and spider-infested area under the barracks. He drilled into them they had to be prepared for anything and that they could not afford to hesitate because doing so might cost them their lives. He also assigned the men KP (“kitchen police”) to teach them to follow orders, but for Harold, he reserved an especially monotonous task – cleaning weapons in the armory, day in and day out. Surprisingly, Harold appreciated the assignment. He became an expert in disassembling, cleaning, and reassembling the M16 and other weapons like the M60 machine gun. He learned which parts failed frequently and what spare parts he needed to carry to repair his weapon in the field. A year later, Harold wrote Sergeant Citron, thanking him. He told him his experience in the armory really helped prepare him for combat in Vietnam.

Overall, Harold had a positive experience at Basic Training. Having been an excellent athlete in high school, he adapted well to the physical training. He also enjoyed meeting and working with the other draftees, who came from all walks of life and all regions of the United States. His company bonded well together, helping each other get through the ordeal.

Harold graduated from Basic Training in July 1969, but his training at Fort Jackson wasn’t over. His next stop was Advanced Infantry Training (AIT). There he became proficient with the M16 rifle, the M60 and .50 caliber machine guns, and hand grenades, and learned how to operate as part of an infantry unit in the field. He also moved into a newer and more comfortable barracks than the one he lived in during Basic Training, but his instructors still enforced strict discipline. Harold and everyone else knew their next assignment was Vietnam, so they took their training seriously. Their lives literally depended on it.

Harold at graduation from Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) in September 1969

Harold at graduation from Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) in September 1969Harold completed AIT in early September 1969 and returned home to Bellmore on thirty days leave. To keep his mother from worrying, he told her the Army was sending him to Germany, a very believable scenario given U.S. commitments to NATO and the ongoing Cold War with the Soviet Union. His father wasn’t fooled. He knew Harold was going to Vietnam. He played along anyway, allowing Harold to have an enjoyable visit.

Harold said goodbye to his family and flew to Oakland Army Base in Oakland, California, on October 4, 1969. There he exchanged all his existing gear for new jungle gear, which he packed in his duffel bag for his flight to Vietnam. When his name was called, he took a bus to Travis Air Force Base, then boarded a charter flight to Japan. He changed planes in Japan and flew to the U.S. Air Base at Bien Hoa, located about sixteen miles northeast of Saigon, arriving on October 6, 1969. His tour in Vietnam had officially begun.

As if being sent halfway around the world to fight in a war wasn’t stressful enough for a twenty-year-old, Harold and most of the other young men on the plane had to do it alone. That is, they weren’t part of a unit that had trained together, bonded together, and then deployed to the war together. Instead, they were replacement soldiers, filling in at a unit for someone who had either gone home at the end of their one-year tour of duty or who had been wounded or killed in action. So, as Harold disembarked the plane at Bien Hoa, he had no idea where he was going or what he would be doing. He simply went where he was told and hoped he would fit in.

Along with the other newly arriving replacement soldiers, Harold boarded a “deuce-and-a-half” truck for the four-and-a-half-mile trip to Long Binh, the Army’s largest installation in South Vietnam. He checked in with the 90th Replacement Battalion, which would tell him where he would be assigned. That meant waiting a couple of days until they called his name and announced his assignment. When he finally heard his name, he learned he’d been assigned to the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), known as the “Redcatchers” because their primary mission was finding and destroying Communist forces in Vietnam.

Harold reported to the 199th’s headquarters unit at Long Binh for in-processing. There he had to turn in all the jungle gear issued to him at Oakland Army Base. In return, he received yet another set of jungle gear. At the end of about three days, just long enough for Harold to start to acclimate to the weather, the 199th issued him his M16, his allotment of ammunition, and a knapsack filled with field supplies. They then put him in a helicopter to Fire Base Mace, located at the foot of Signal Mountain, about forty miles east of Saigon in an area permeated by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong activity. Signal Mountain was so named because of the important U.S. communications facilities at the top, making it the target of frequent enemy attacks. Part of the mission of the forces occupying Fire Base Mace was to make sure those enemy attacks never succeeded.

Once at Fire Base Mace, Harold learned he would be joining the 1st platoon of Bravo Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Infantry, of the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light), which was currently conducting operations in the field. Armed and ready, Harold boarded a helicopter, which ferried him to a landing zone (LZ) in the jungle. To his surprise, his new platoon was engaged in a firefight, which he was now expected to jump into after only a few days in country and having never even met anyone he would be fighting alongside. He felt sheer terror as he disembarked the helicopter and joined in the engagement. Once he survived that experience, fear completely left him. For the rest of his time in Vietnam, he was afraid of nothing, because in his mind, nothing could ever be as terrifying as his first encounter with enemy fire.

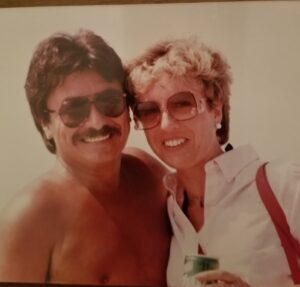

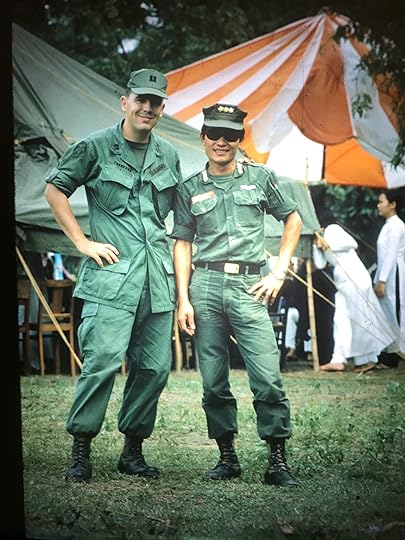

PFC Lynwood Thornton (left) and PFC Harold Jantz (right) with a radio on the ground between them

PFC Lynwood Thornton (left) and PFC Harold Jantz (right) with a radio on the ground between themAfter the firefight, Harold got to meet the men in his unit. His lieutenant, Roger Soiset, was from Georgia and a graduate of The Citadel, a prestigious military academy in South Carolina. As the lieutenant had a thick Georgia accent which was hard to understand on the radio, and as Harold had an equally thick New York accent that was easier to understand, Lieutenant Soiset immediately designated him his new radio telephone operator, or “RTO”. This meant in addition to carrying his weapon and his personal gear, Harold had to carry a twenty-five-pound radio on his back together with a supply of batteries. It also made him a priority target for the enemy because if they could kill a unit’s RTO, they could more easily isolate and destroy the unit. When Harold said he had no idea how to operate the radio, the lieutenant replied, “You’ll learn.” From that point on, Harold was the RTO for the platoon’s first squad, while Private First Class Lynwood Thornton served as the RTO for the platoon’s second squad.