David E. Grogan's Blog, page 5

January 21, 2022

Specialist Andrea Marshall, U.S. Army – Something Bigger Than Self

It takes courage to enlist in the military. Once you raise your right hand and take the oath to serve and defend the Constitution, you must go wherever the military says you are needed most. When the nation is at war, that need could very well be in a war zone where your life is at risk. Such is the case with Specialist Andrea Marshall, who enlisted in the Army in 2008. Four years later, she found herself assigned as a combat medic at a Forward Operating Base in Afghanistan. This is Andrea’s story.

Andrea was born and raised in New Berlin, Illinois, a very small town located about fifteen miles west of Springfield, the capital of Illinois. Her dad was a career Navy Reservist. Andrea remembers seeing him bring home books to study for advancement exams and carefully keeping track of his drill points to make sure he earned enough points to retire. His experience weighed heavily on her as she looked at life beyond New Berlin High School. She saw the military not only as an opportunity to get away from her small town and see the world, but also as a means of adding structure and direction to her “wishy-washy” outlook and participating in something that was bigger than self.

The Air Force almost snagged Andrea after she graduated from high school in 2007. In fact, an Air Force recruiter worked up an enlistment package on her before she graduated, but Andrea didn’t feel like he was being responsive to her questions and concerns. His indifference convinced Andrea the Air Force was not for her. Instead, she enrolled at Lincoln Land Community College hoping to teach music to kids. Music had been her love in high school, where she played the clarinet, the saxophone, and a handful of other instruments. One of the benefits of the Lincoln Land program was that it allowed her to teach music to kids at a local elementary school. That experience proved crucial, because it taught her that her love of teaching music to kids did not include dealing with their parents.

During the spring semester of 2008, Andrea talked to an Army recruiter at the college. Her goal was to be a musician in the Army’s Big Band. The recruiter said he could arrange for an audition, but she had to have a “Plan B” in case she wasn’t selected for the band. Andrea thought that was reasonable, so she and the recruiter worked up an alternative enlistment package for the medical field. She also took and passed the Army’s Physical Fitness Test (PT test), which she was told would benefit her once she graduated from Basic Training.

The Army recruiter delivered on his promise for the audition, which took place before the end of Andrea’s second semester at Lincoln Land Community College. She was very nervous for the audition and, looking back, she feels as though she should have auditioned for saxophone rather than clarinet. Unfortunately, she did not make the band, but she was still excited about her second choice of becoming an Army combat medic.

Andrea completed her second semester at Lincoln Land Community College and then reported to the St. Louis Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) for her formal induction into the Army in June 2008. She arrived at the MEPS around 4:00 a.m. and was the first person through the screening line. As instructed, she took an elevator to the building’s top floor. When the elevator arrived at the top floor, the doors wouldn’t open and Andrea found herself trapped inside alone. She pushed the help buttons, but it was just after four o’clock in the morning, so no one answered. Eventually she connected with someone through the elevator’s emergency phone who promised to send someone to get her out.

While Andrea was waiting for help to arrive, she called her father on her cell phone. He told her not to panic and asked if there was a vent in the elevator. When she told him there was, he assured her she would be okay because there should be enough oxygen in the elevator for her to breathe. This created a new worry because now Andrea wondered if her dad might be wrong. Finally, the firefighters arrived. They had to pry open the doors because the elevator had gone two feet past the stopping point for the top floor. Andrea climbed out, put the incident behind her, and went on with her day. Still, this was not the beginning she envisioned for her enlistment in the Army.

After completing her final physical and taking the oath of enlistment, Andrea and the other new Army recruits at the MEPS took a bus to the airport and a flight to Atlanta. Once in Atlanta, they boarded another bus to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, arriving at “zero dark thirty”. Drill sergeants screamed at them to get off their bus and immediately let the new arrivals know who was in charge.

Although the male and female recruits lived in separate barracks, they did their Basic Training together. Platoon and squad leaders were chosen by the drill sergeant from within the ranks of the recruits, rotating on a weekly basis. During one week, a recruit platoon leader returned to the barracks after the firing range upset because she was told she could no longer be a platoon leader because her rifle scores were too low. In consoling her comrade, Andrea indicated that didn’t seem right and that leadership was more than just being able to fire a weapon. Much to Andrea’s chagrin, the drill sergeant overheard what she said. The drill sergeant asked her, “So you don’t think I make good decisions?” He then promoted Andrea to platoon leader so she could see what leadership really entailed.

Unlike her predecessor, Andrea could shoot. In fact, when she went to the range to qualify with the M4 rifle, she is pretty sure the sergeants took bets on how well she would do. When Andrea’s target was scored, she only missed on two of the forty rounds she fired. Her drill sergeant came up to her afterwards and asked her how she could have missed twice, once on a 50-meter target and once on a 300-meter target. Andrea is sure he bet that she would score hits with all forty rounds and had to pay up even though she’d excelled on the range and earned her Sharpshooter badge.

Andrea Marshall at AIT

Andrea Marshall at AITAndrea graduated from Basic Training in August 2008. Because she had completed one year of college and passed the PT test prior to enlisting, she was immediately promoted to Private First Class. This meant more pay and seniority as she reported to her follow-on Advanced Individual Training (AIT) at Fort Sam Houston, located in San Antonio, Texas. It was there that Andrea would learn to become a combat medic.

Andrea loved everything about AIT. The training was broken into two sessions. The first was the “civilian” session, where Andrea earned her Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) certification. The training was intense because the normal semester-long certification had to be completed within two months. During this session, Andrea learned such skills as controlling bleeding, stabilizing broken bones, and dealing with patients in shock.

The second two-month session was called the “whiskey school” because the Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) code for combat medics is 68W (where the “W” is pronounced “whiskey”). During this session, Andrea learned the additional skills she would need to keep wounded soldiers alive on the battlefield, like dealing with gunshot and shrapnel wounds, applying tourniquets and stabilizing soldiers suffering amputation injuries, and administering medications. As a final exercise, Andrea spent seven days in the field being tested on what she had learned on soldiers with simulated combat injuries.

Andrea graduated from AIT in December 2008, earning her combat medic MOS. After taking leave over the holidays, she reported to the 2nd Battalion, 159th Aviation Regiment (2-159th), located at Storck Barracks in Illesheim, Germany. The 2-159th Battalion, together with the 3rd Battalion, 159th Aviation Regiment (3-159th), operated Apache attack helicopters and were the two principal units operating from a small airfield located on the installation. The remainder of the 12th Combat Aviation Brigade, of which the 2-159th and 3-159th were a part, operated out of the U.S. Army Garrison at Ansbach, located about fifteen miles away. Thus the U.S. facilities available at Storck Barracks were limited to a commissary, a gas station, a small convenience store, an elementary school, and family housing.

On the bus taking her from the airport to Storck Barracks for the first time, Andrea couldn’t believe her new assignment. She’d enlisted in the Army to get away from small-town life in New Berlin, Illinois, and now she was going to live and work in a small town located in the middle of nowhere in Germany. Once she completed a week-long course about living in Germany and learned some basic German phrases, she felt less stressed about her new assignment.

Andrea worked at the Storck Barracks clinic, together with one or two other combat medics and a flight surgeon (sometimes two). Her duties included diagnosing and treating patients, issuing medications, and dealing with the normal administrative tasks associated with operating a clinic. For field exercises, Andrea would pack up the unit’s medical equipment, load it on a Humvee, drive the Humvee about ninety-five miles on the autobahn to the exercise site at the Grafenwoehr Training Area, and set up and run an aid station in the field.

During one such exercise, a soldier reported to the aid station that he was having terrible pain in his arm, having injured it while playing frisbee. Andrea examined his arm and concluded it was broken, which meant she would have to ride with him to the Grafenwoehr clinic, located about fifteen minutes away, where his arm could be x-rayed. When Andrea relayed her opinion to the flight surgeon to get his permission to go, he said he didn’t think it was broken and that Andrea was just saying that because she wanted to stop at Burger King, which was near the clinic. Andrea pushed back and the flight surgeon gave in. The trio then rode to the clinic where an x-ray revealed that the soldier’s arm was indeed broken. Feeling vindicated, Andrea insisted they stop at Burger King on the way back to the aid station and that the flight surgeon pay for it, which he did.

In 2011, Andrea had a baby girl and got married to another soldier assigned to the unit. She had only a little time with her daughter, though, before another big event loomed on the horizon – the 2-159th Battalion was getting ready to deploy to Afghanistan in May 2012. Because Andrea and her husband were both deploying with the unit, they flew back to the United States to meet each other’s parents and leave Andrea’s daughter in their shared custody while Andrea and her husband deployed. Having to leave her daughter was very hard, but at least Andrea knew she was in good hands.

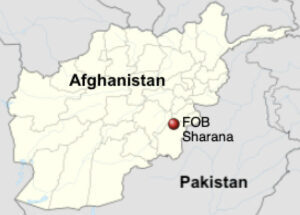

Andrea and the 2-159th Battalion did not deploy directly to Afghanistan – they made an initial stop in Kazakhstan for some final theater-specific training. This included rollover training, where Andrea learned how to escape from a Humvee after it rolled over and pull the other occupants to safety. After about a week in Kazakhstan, the unit continued to Forward Operating Base (FOB) Sharana in eastern Afghanistan, near the border with Pakistan.

Map of Afghanistan showing location of FOB Sharana – Source: NordNordWest

Map of Afghanistan showing location of FOB Sharana – Source: NordNordWestAndrea arrived at FOB Sharana in May 2012. Aside from Afghanistan being a dangerous war zone, Andrea thought the country itself was beautiful. She also had the opportunity to meet some of the local nationals who had set up tents where soldiers could purchase knives, DVDs, and rugs. She found the people she met very friendly and easy to talk to.

Life at FOB Sharana soon settled into a routine with the highlight of every day revolving around meals. Soldiers would do their work wherever they were assigned, but for meals, they would go to the chow hall as a group with their friends. Andrea found it strangely similar to the way the various cliques ate together in her high school cafeteria.

Another important event was when supplies were flown in. If the supplies included Pepsi, some of the supply guys unloading the helicopters would bring a case to the clinic because they knew the Andrea liked it. In return, Andrea would put on a Scrubs, House, or Chief DVD and let the supply guys watch on the TV in the waiting room.

During Andrea’s time at FOB Sharana, she typically dealt with lots of routine injuries, like ankle sprains occurring when soldiers twisted their ankles running on the FOB’s rock-strewn terrain. On one occasion, a soldier tried to use his knife to clean something stuck to a helicopter and ended up stabbing himself in the leg. On another occasion, a soldier passed out while standing in formation and fell face first onto the rock and gravel-covered ground. In both cases, Andrea cleaned the wounds and stitched them up and the soldiers returned to duty.

The most serious condition Andrea had to deal with turned out to be her own. In August 2012, Andrea began to experience severe pain in her lower back. Eventually, the pain got so bad that she collapsed while trying to get her gear. The soldiers from the communications shop (S-6) heard her fall and called the flight surgeon. The flight surgeon initially suspected kidney stones, but later determined the cause to be blood clots resulting from a known risk of smoking while taking birth control pills. Although Andrea was aware of the risk, she never thought it would happen to her. Now she cautions women about the risk saying it’s more than just theoretical—it really can happen.

The condition was so severe that Andrea had to be medevac’d to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. She was initially placed in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) until the blood clots resolved. During this time, the Wounded Warrior Project stepped in to purchase clothes for her at the PX (post exchange) and made sure she was taken care of. Andrea then transitioned to temporary quarters at Ramstein so she could be monitored as she moved off blood thinner shots and started blood thinner pills.

After approximately three weeks, Andrea was back on her feet, but she was not permitted to return to her unit in Afghanistan because of her blood thinner medication. Accordingly, she returned to Storck Barracks, where she rejoined her husband who was recuperating from surgery after severing a tendon in his thumb. When Andrea became pregnant with their second child, she told her husband she couldn’t do another hitch in the Army. She’d already missed her daughter’s first birthday, her first steps, and her first words, and now the cycle was going to start again.

Andrea’s daughter welcoming Andrea home at the airport

Andrea’s daughter welcoming Andrea home at the airportWith her new direction clear, Andrea was honorably discharged from the Army in February 2013. Because her husband had to finish his tour in Germany and Andrea was not considered a command sponsored dependent, Andrea moved with her daughter to Alabama to live with her in-laws. The family later reunited at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, for Andrea’s husband’s follow-on tour, but the pressures on the family proved too great and Andrea’s marriage dissolved. Andrea then moved with her daughter and son back to her hometown in New Berlin, Illinois, to start her life anew.

As Andrea looks back at her service in the Army, there is one painful aspect that needs to be told. Andrea was sexually assaulted by a someone she trusted. Because he was in her chain of command, she felt like she had nowhere to turn or anyone she could talk to about it. She hopes that by talking about it now, it will empower women to reach out to each other for strength and support. She also calls on the military to continue to root out sexual misconduct by changing the culture and holding those responsible accountable for their actions.

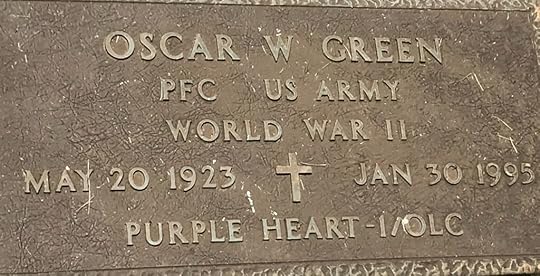

After arriving back in Illinois, Andrea returned to college to pursue a nursing degree using her GI-Bill benefits. However, when she learned the program would not give her credit for her previous science courses and some family emergencies required her time, she decided she needed a stable career now to provide for the two most important people in her life: her daughter, Nevaeh, and her son, Aidan. That’s when she found a position working as a National Cemetery Representative for the Camp Butler National Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois. In her position, Andrea helps veterans and their families at a time when they need it most, meeting with the family members of the deceased, advising them of veterans’ benefits, and providing them information on burials at national cemeteries.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Andrea Marshall for her service in Army. She enlisted during a time of war and answered our countries call by deploying to Afghanistan, where she served with distinction. She then returned to civilian life to raise her family, all while continuing to serve veterans and their families as a National Cemetery Representative. We thank Andrea and her family for their service and sacrifice, and wish her fair winds and following seas.

Andrea Marshall (left) with her sister

Andrea Marshall (left) with her sister

December 23, 2021

Sergeant Jim Elsener, U.S. Marine Corps – From Chicago to Da Nang…and Back

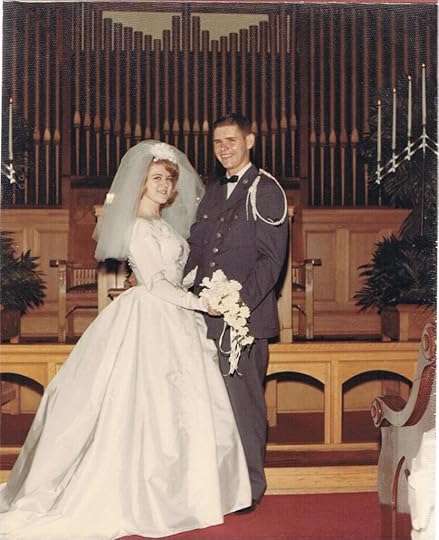

Sometimes in life we are presented with choices where the “right” choice is obvious. Sergeant Jim Elsener, U.S. Marine Corps, was given such a choice in January 1966. He could finish out his enlistment at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, having served in the Marines with honor, and return to civilian life in the Midwest. Or he could choose a course that promised many unknowns. Jim chose the latter, and as the poet Carl Sandburg so eloquently expressed, that choice has made all the difference. This is Jim’s story.

Jim was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1943. His father worked at the Douglas Aircraft Company’s assembly plant at what is now O’Hare International Airport. Having been born in 1912 and married with one son when the war began, Jim’s father wasn’t drafted until the very end of World War II. He never had to serve, though, because the war in Europe ended and he was no longer needed.

In 1947, Jim’s family moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, and later to Detroit, where his father worked as a floor covering salesman. In 1955, the family moved again to Jonesville, Michigan, a small town about 100 miles west of Detroit where his father and uncle entered the farm implement business. They stayed in Jonesville for all of Jim’s school years, frequently traveling to Chicago to visit family and friends. They still considered Chicago home.

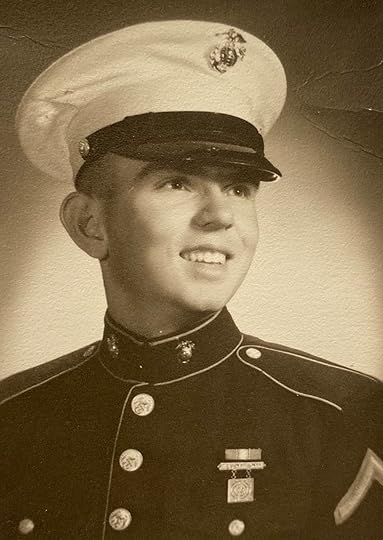

Jim graduated from Jonesville High School in the spring of 1961. He enrolled at nearby Albion College, but after completing one unsatisfactory year, he enlisted in the Marines in July 1962.

Jim reported for boot camp at Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) San Diego. He succinctly sums up his experience there by saying “there was nothing warm and fuzzy about boot camp.” He did, however, have an exceptional junior drill instructor, Sergeant Johnny Adams. Jim and the other recruits respected him and, at the end of their training, agreed Sergeant Adams was a gifted leader and outstanding instructor.

After graduating from boot camp as a Private First Class (E-2), Jim went through infantry training at Camp Pendleton, California, and then radio school at MCRD San Diego, where he learned Morse Code. In June 1963, he received orders to his first permanent duty station, Communications Platoon, Headquarters & Service Company, 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines, at Camp LeJeune.

From left to right, Cpl John Briggs, Cpl Jim Elsener, LCpl Norm Jetland, and LCpl Bill Donohue on Vieques Island, Puerto Rico, in January 1965

From left to right, Cpl John Briggs, Cpl Jim Elsener, LCpl Norm Jetland, and LCpl Bill Donohue on Vieques Island, Puerto Rico, in January 1965In December of that same year, Jim’s battalion deployed aboard ships to the Caribbean for a three-month tour of duty. Jim and his unit sailed on the USS Monrovia (APA-31), which had seen service during World War II and Korea. Ports of call were Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Camp Garcia on Vieques Island, Puerto Rico, where they practiced amphibious landings, close air support, and basic infantry tactics.

In January 1964, Jim’s battalion was sent to the Panama Canal Zone for jungle training at Fort Sherman, a U.S. Army base. The first night in-country, anti-American riots erupted in Panama’s capital, Panama City. The battalion was ordered back aboard ship and docked at the Coco Solo Naval Base at the Caribbean end of the canal to provide security. They stayed there for two months, living aboard ship but practicing riot control techniques ashore. Despite the unrest, the battalion was able to finish its jungle training before returning stateside. History has tagged this period as the “beginning of the end” for U.S. control of the Panama Canal Zone.

In October 1964, the Second Marine Division, which included Jim’s battalion, participated in Operation Steel Pike, the largest peacetime amphibious landing in history. Over 28,000 U.S. Marines and Spanish military took part in the exercise along the southwest coast of Spain. Unfortunately, it got off to a bad start when two helicopters ferrying Marines ashore collided, killing nine and injuring thirteen. As Jim waited on the flight deck of the USS Okinawa (LPH-3) for his turn to board a helicopter to join in the landing, he could see smoke and flames from the crash even though he was five miles out to sea. Once ashore, Jim’s battalion held a field memorial service for their fallen comrades. The exercise continued for seven days. After it concluded, the USS Okinawa stopped in La Rochelle, France, and Plymouth, England, giving Jim and his fellow Marines some well-deserved liberty before returning to the United States.

In the spring of 1965, Jim’s battalion once again deployed to the Caribbean for a lengthy stay in Vieques, Puerto Rico, and then Fort Sherman in the Panama Canal Zone. Other ports of call were Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Barbados; and Kingston, Jamaica. This was the battalion’s third deployment in two years.

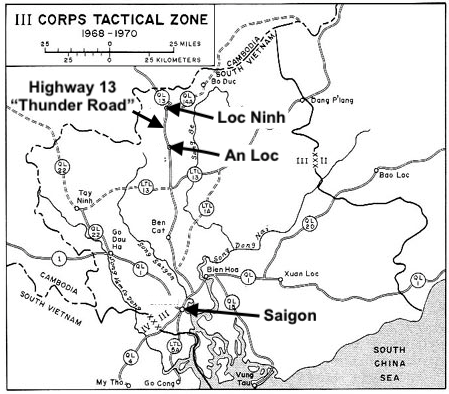

Map of South Vietnam showing Da Nang

Map of South Vietnam showing Da NangShortly after his battalion returned to Camp Lejeune, Jim’s tour of duty with the 8th Marines came to an end. In July 1965, he transferred across the base to the 10th Marine Regiment, which provides artillery fire support to the infantry regiments of the Second Marine Division. When Jim reported to the 10th Marines, he had less than one year remaining on his enlistment. Being a relative “short-timer,” he was in a position to ride out the rest of his time at Camp Lejeune and transition back to civilian life in the summer of 1966. However, the war in Vietnam had begun to escalate rapidly, both in terms of U.S. troop involvement and intensity. In March 1965, the 9th U.S. Marine Expeditionary Force had deployed to Da Nang, a city located approximately 380 miles northeast of Saigon, to provide security for the airport. It was the first Marine combat unit in Vietnam and the Marine Corps needed more men to fulfill its expanding combat mission. To help achieve this, on August 20, 1965, the Marine Corps involuntarily extended the enlistments of Jim and other regular Marines for four months, which meant Jim would not be eligible for discharge until November 1966.

Because Jim now had adequate time on his enlistment to go overseas, he was offered an “opportunity” to take an all-expense paid trip to Vietnam. He had trained for three years to do his job as a Marine and had been promoted to corporal (E-4). As a non-commissioned officer (NCO), he felt an obligation to do his part in the war. So, in February 1966, Jim took leave to visit his family and then reported to Camp Pendleton for three weeks of intense training. He spent long days and nights in the field operating on little sleep, learning lessons that could save his life in Vietnam.

In March 1966, Jim boarded an Air Force C-141 “Starlifter” transport jet and crossed the Pacific, stopping to refuel on Wake Island and finally landing on Okinawa. A week later, Jim and the other Marines deploying as individual replacements loaded onto an Air Force C-130 “Hercules” transport for the six-hour flight across the South China Sea to Da Nang.

Upon arrival in Da Nang, Jim was assigned as a radio operator with the 1st 8-Inch Howitzer Battery of the 12th Marines. At the time, the unit consisted of 8 officers and 200 enlisted Marines who manned and fired the powerful M115 8-inch howitzers. These big guns, known as the “King of Battle,” could hurl 200-pound high-explosive projectiles to targets located as far as fourteen miles away. Jim felt the earth shake every time one of the howitzers fired.

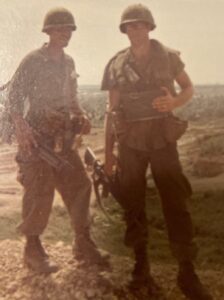

PFC Willie King (left) with Jim Elsener (right) in Vietnam in July 1966

PFC Willie King (left) with Jim Elsener (right) in Vietnam in July 1966While Jim was with the battery, the unit occupied three different fire bases, all within approximately ten miles of Da Nang. Several guns and crews were also deployed with Marine infantry units operating from fire bases deeper in the countryside.

Because Jim was a radio operator, he was assigned as the driver for the battery’s commanding officer (CO), Major Paul Wilson, a crusty Mustang (enlisted Marine who became an officer) and veteran of the Korean War. Each day Jim and Major Wilson visited the battery’s various firing positions to check on the guns and their crews. They also searched for new firing positions across the Da Nang tactical area of responsibility (TAOR). On May 1, 1966, Major Louis J. Cavallo, an ROTC graduate from the University of Maine and also a Korean War veteran, assumed command of the battery and kept Jim on as his driver. Jim especially admired Major Cavallo and thought he was a terrific leader.

Though Jim’s jeep had reinforced metal plates on the floor to protect against explosive devices, on many mornings Jim and his CO had to wait for engineers to clear the roads of mines before they could proceed. Often, they found themselves alone searching for new firing sites, which required them to be extra alert for trouble. On one occasion, they heard a bullet whiz by and saw it hit the road just in front of the jeep. Jim stepped on the gas and got out of there.

Jim experienced enemy fire another time when his fire base was probed by the enemy one night. When the shooting started, Jim was off duty. He jumped out of his sleeping quarters into a nearby sandbagged bunker and saw the hot end of an automatic weapon firing in his direction. The Marines at the closest guard post opened fire and silenced the enemy weapon. The unit then called in “Puff the Magic Dragon,” a fixed wing gunship operated by the U.S. Air Force to provide close air support for ground troops. “Puff” shot up the area outside the fire base, putting an end to any Viet Cong (VC) in the area.

Jim on R&R in Hong Kong

Jim on R&R in Hong KongLife as a driver also had its perks. One day, Jim drove Major Cavallo to pick up two Red Cross “Donut Dollies” who were assigned to the battery. These young women had volunteered to support U.S. servicemembers in Vietnam by socializing with the men, playing cards and other games, telling jokes, and just trying to help maintain their morale while all were serving so far from home. Jim said it felt like a high school double date when they picked up the women in Da Nang. Jim drove, with one woman sitting in the passenger seat, while the Major and the other woman scrunched into the back next to the radio. At the fire base, the women ducked for cover when they first heard an eight-inch howitzer fire but were reassured when they learned it was outgoing – not incoming.

Besides his duty as the CO’s driver, Jim stood regular radio watches in the Fire Direction Center (FDC). The battery was always involved in direct support of Marine units engaged with the enemy or nighttime harassment and interdiction, known as H&I fire. Forward observers in the field would call in fire missions to Jim and the other radio operators, who would relay the firing coordinates and specifications (type of explosive, target adjustments, and number of rounds to be fired, as well as after action reports) to the FDC crew. The FDC crew would, in turn, prepare and communicate specific firing instructions to the gun crews via land line. It was crucial that all the information be passed accurately at every point of the communication trail.

Often, the Marine forward observers communicating with Jim would whisper into their radio handsets, reflecting their proximity to enemy forces. Sometimes all the forward observer could do was click the microphone to acknowledge message receipt because speaking was too dangerous. The fact that there were Marines in the field whose lives depended on him was never lost on Jim. He realized that even a small error in relaying the target coordinates could cost American lives.

Jim also often went on patrols around the perimeter of the fire base and in nearby villages searching for signs of enemy activity. And he and his fellow Marines fought a constant battle with the humid tropical environment trying to keep their weapons clean. If he didn’t give his M14 rifle a thorough cleaning almost every day, it would begin to rust—a grave sin for any Marine.

Jim was promoted to sergeant (E-5) in September 1966. The following month, he enjoyed R&R (rest and relaxation) in Hong Kong. That trip stands out in his mind because he recalls sitting in the lobby of his hotel reading a newspaper and learning the Baltimore Orioles had swept the Los Angeles Dodgers in four games in the 1966 World Series.

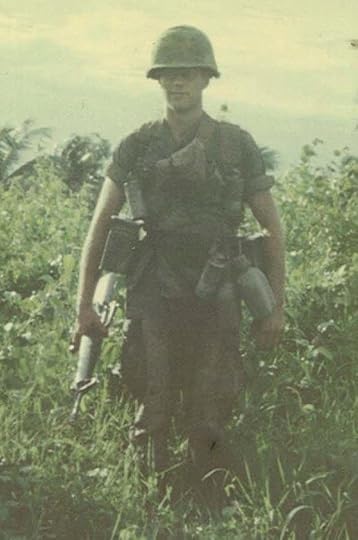

Jim Elsener and Bob Snead with their discharge papers

Jim Elsener and Bob Snead with their discharge papersBy December 1966, Jim had only one month left on his enlistment. Friend and Company Clerk, Sergeant Bob Snead, told Jim he could cut orders to get them both home before the holidays. Sergeant Snead was good to his word and the two men detached from their unit and headed to the Da Nang terminal to catch a flight to the United States via Okinawa.

As had happened when Jim arrived in country, the veterans getting ready to leave Vietnam began shouting warnings at the new troop arrivals disembarking from the airplane Jim would take on its return trip to Okinawa. This time, Jim was one of the NCO’s ordering the veterans to knock it off rather than being on the receiving end of their taunts. Jim departed Vietnam on December 10, 1966, after having spent eight months and twenty-two days in country.

On December 13, Jim left Okinawa on a chartered Continental Airlines flight bound for the United States. His journey ended at El Toro Marine Corps Air Station, where he received his Honorable Discharge on December 20. He had served four years, five months, and five days on active duty. Jim and Bob Snead then spent two days in Las Vegas “decompressing” before returning to their homes in time to spend Christmas with their families.

In January 1967, Jim drove to Los Angeles where he found work as a lineman for the telephone company. Although he enjoyed the job and the California lifestyle, he moved back to Michigan in the fall of 1967 to attend Western Michigan University using his GI Bill benefits. This time he excelled at college, graduating in 1970 with a degree in communications.

Jim’s first job was with the City News Bureau of Chicago, where he worked as a reporter and editor covering federal and state courts, politics, and the police beat. Two-and-a-half years later, he was hired by the Chicago Tribune, where he worked for five years as a general assignment reporter and covering politics and business. It was during this time that he met his future wife – Patricia, also a Tribune journalist.

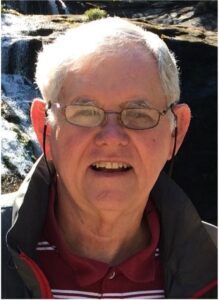

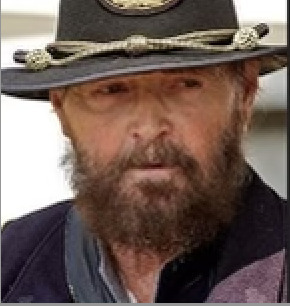

Jim Elsener

Jim ElsenerIn 1975, the Tribune sent Jim to study for a year as a Knight-Bagehot fellow at the prestigious Columbia University School of Journalism in New York City, where he studied business, economics, and finance. After returning to the Tribune, Jim specialized in covering economics and the energy industry. He spent three weeks in Alaska reporting on the construction of the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline, which was the major economic and environmental story of that era.

Jim left the Tribune in 1977 to manage a national newspaper trade association and in 1992, he and his wife started their own regional business publication. They sold the company fifteen years later to a local daily newspaper. He stayed with that company for seven years before retiring in 2017. During the span of his forty-two-year journalism and publishing career, he served as a reporter, columnist, editor, publisher, sales manager, and association executive.

Although Jim’s newspaper days are behind him, his writing continues. In August 2018, he published his first novel, The Last Road Trip, about a major league baseball player trying to figure out what comes next after his baseball playing days have ended. In June 2021, he released his second novel, Reflections of Valour, a story of untested lovers from opposite backgrounds during the tumultuous early days of the Vietnam War. The book is equal parts a love story and a soldier’s story at war, and is a fictionalized autobiography of Jim’s time in the Marine Corps. The story uses the Vietnam Memorial Wall as an important backdrop. Jim’s third book, a murder-mystery, is currently in the works. You can learn more about Jim on his author website.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Jim Elsener for his distinguished service in the Marine Corps and in Vietnam. Whether conducting exercises off the coast of Spain, guarding the Panama Canal Zone, or helping to direct artillery fire on enemy positions near Da Nang, Jim served with distinction and answered our country’s call. We thank him for his years of service and wish him fair winds and following seas.

November 20, 2021

Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force – “A Year in Nha Trang: 1968-69”

Destiny has a way of just happening, whether you want it to or not. Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force, knows that all too well. No matter how many times he tried to point his life in a particular direction, destiny kept bringing him back to where he was meant to be. He was destined to serve our country in Vietnam, where his expertise with armaments would help protect American lives. And, he was destined to marry Barbara, his wife of fifty-two years, despite his impending deployment to a war zone and not knowing if he would ever return. This is his story.

Dean was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1947. He attended Atlanta city public schools, graduating from Franklin D. Roosevelt High School in 1965. Although he did not know her well yet, his future wife, Barbara, graduated from the same high school one year ahead of him. Since senior girls did not normally associate with junior boys, their romance was yet to be.

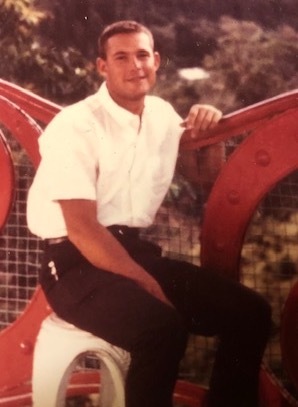

Dean and Barbara’s wedding

Dean and Barbara’s weddingDean’s graduation from high school in 1965 was bittersweet. He was thrilled to be moving on to the next stage of his life, but he also knew graduation meant the very real possibility of being drafted to fight in the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam. Against that backdrop, he enrolled in his local community college to study electronics, giving him a deferral from the draft. His courses were technical and vocationally oriented, rather than degree oriented, and he really enjoyed the hands-on work. As an offshoot of his studies, he earned his FCC license and became a HAM radio operator. The two-year course of study also gave him the opportunity to begin dating Barbara now that the junior/senior distinction of high school was gone.

Dean finished his electronics studies in 1967 and immediately received a notice to report for his pre-induction physical. Concerned with the prospect of being drafted into the Army or the Marines, he visited his local Air Force recruiter. The recruiter told him his two years of electronics training would allow him to bypass the Air Force’s introductory electronics school at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, and immediately get to work in the electronics field. That sounded good to Dean, so he committed to the Air Force, enlisting in the delayed entry program in June 1967, with a report date three months later.

Dean’s parents and Barbara weren’t thrilled with Dean’s enlistment. He was an only child, so his parents were understandably worried. Barbara also worried because she had no idea what lay in store for Dean now that the Air Force owned him for the next four years. Dean reassured them his Air Force enlistment protected him from the draft and he would be safe. So, with heavy hearts, they bid Dean farewell in September when it came time for him to honor his commitment.

Dean reported for Basic Training at Lackland Air Force Base in September 1967. After graduating, Dean was shocked to learn he was being sent to Armament School at Lowery Air Force Base in Denver, Colorado. There, instead of commencing work in electronics as the recruiter had promised, he would learn how to arm airplanes with bombs, rockets, guns, and missiles. He also surmised that meant he would be headed to Vietnam as soon as he finished his training, rather than working on electronics systems stateside or in Europe.

Mustering all of the intestinal fortitude he could as a newly-minted Airman (E-2), Dean approached his sergeant and told him his new orders had to be a mistake. He told his sergeant he believed he was supposed to be working on electronics and the orders should have been to Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, not Lowery Air Force Base in Colorado. Dean’s sergeant left no room for misunderstanding. He told Dean he was in the Air Force now and would be assigned based on the needs of the Air Force, not his desires or what he thought he had been promised. He told Dean he was going to be a weapons mechanic and he better get used to it.

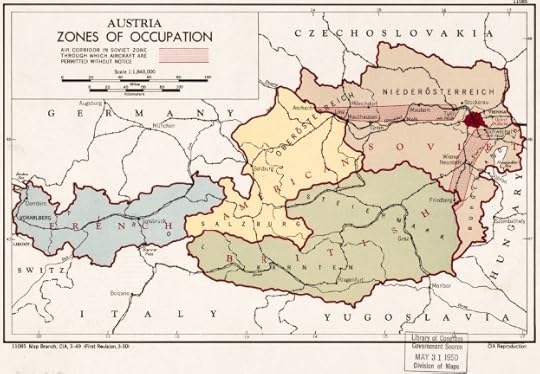

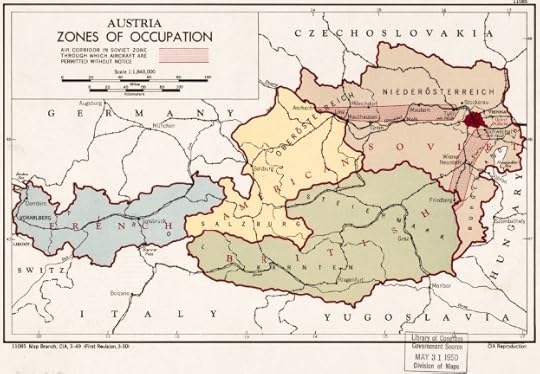

Dean Moss’s South Vietnam

Dean Moss’s South VietnamDean reported to Lowery Air Force Base as ordered and learned all about the art of arming aircraft. In week eleven of the fifteen-week course, Dean received orders to his first duty station: the 4th Air Commando Squadron in Pleiku, Republic of South Vietnam. While it was bad enough receiving orders to Vietnam, what he dreaded even more was calling Barbara and his parents to tell them the news. With coverage of the bloody Tet Offensive having recently played out on televisions all across America, their reaction was predictable. Dean also talked with Barbara about their future, not wanting her to commit to someone who was about to be sent to a war zone. That didn’t matter to Barbara, so after much thought and prayer, Dean proposed to her during a call he made from a phone booth in Colorado. After she accepted, Dean committed himself to finishing his training at Lowery, where he graduated as an Honor Graduate in April 1968.

After graduating from Armament School, Dean took thirty days leave. He went home to Atlanta on April 17th and married Barbara on May 4th. Behind the scenes and unbeknownst to Dean, his mother wrote their Congressman to request that Dean not be sent to Vietnam given he was the only male child in their family’s line. She told the Congressman if he died, there would be no one to carry on the family name. Her request was denied.

On May 20, 1968, just sixteen days after marrying Barbara, Dean found himself kissing her goodbye at Atlanta’s Hartsfield International Airport. It was the hardest thing Dean would ever do, not knowing if he would ever see her again. He then flew from Atlanta to Seattle, Washington, where he reported to McChord Air Force Base for further transit to Vietnam. At McChord, he and servicemen from all the other services boarded a chartered Northwest Orient flight bound for Vietnam. They flew nonstop to Tokyo, where the plane refueled and English-speaking Japanese stewardesses replaced their American counterparts for the final leg of their journey.

The flight landed in South Vietnam after dark at Cam Ranh Bay Air Base, located approximately 180 miles northeast of Saigon. Dean hadn’t been given any real training on what to expect other than to make sure he had a will and had given his wife a power of attorney, so everything about Vietnam surprised him. He hadn’t expected a lush tropical climate, nor had he been informed about the magnesium star shells that would be lazily descending over the base at night to help ward off would-be attackers. So, when Dean got off the plane and saw a flair floating over the base on a parachute, he wondered if the base was under attack. Even more worrisome, he’d received no training on things he’d heard about like booby traps and grenade attacks. All he’d had was M16 rifle training, but he’d not been issued a rifle or battle gear, so he felt very vulnerable. It made for a stressful transit from the flight line to the barracks and for a sleepless night once there, where he not only had to cope with the intense tropical heat, but also had to fight off a multitude of Vietnamese mosquitoes trying to welcome him to his new home.

The next morning, Dean boarded a C-130 cargo plane headed for Pleiku in South Vietnam’s Central Highlands. The plane made a spiraled approach into the airfield at Pleiku, causing Dean to hang on for dear life as it felt like the airplane was crashing. Once on the ground, he found it noticeably cooler than Cam Ranh Bay, especially since the monsoon season was just beginning. As per his orders, he reported to the 4th Air Commando Squadron, which operated AC-47 gunships, known as “Puff the Magic Dragon”. Each plane was equipped with three Gatling guns (called miniguns) that in a matter of seconds could saturate an area the size of a football field with thousands of 7.62-millimeter machine gun rounds. The squadron wanted Dean to man one of the airplane’s miniguns during flights to make sure it fired when needed. Unfortunately for the squadron, Dean did not have the level of training required for the job and they did not have time to train him. They told Dean they were going to send him back and, at least for a moment, Dean thought that meant he would be going back to the States.

Dean standing with an O-1E Bird Dog loaded with rockets

Dean standing with an O-1E Bird Dog loaded with rocketsInstead, Dean was sent to the 21st Tactical Air Support Squadron (TASS) in Nha Trang, located on the coast just twenty-seven miles north of Cam Ranh Bay. The 21st TASS operated the single-engine Cessna O-1E “Bird Dog” and its replacement, the twin-engine Cessna O-2A. These slow-moving and vulnerable planes provided Forward Air Control (FAC) guidance to tactical aircraft and helped artillery units and even ships at sea attack enemy forces on the ground. In addition to radioing target coordinates, the Bird Dogs fired white-phosphorous rockets at enemy positions to mark their locations with smoke. Attack planes would then swoop in to deliver bombs and other ordnance on the targets. After the attack, the slow-moving Bird Dogs would again fly low over the enemy positions to assess the damage and, if necessary, call in another attack. It was dangerous work; often the planes came back riddled with bullet holes. With the pilot’s and spotter’s lives at risk on every mission, it was crucial the planes’ rocket launchers worked as intended. Dean’s new job was to make sure they did.

Keeping the rocket launchers in working order meant keeping them clean and making sure the rockets went where they were aimed. On one occasion, a pilot returned from a mission and reported the rockets were hitting left of target. When Dean inspected the plane, he found the metal sight extending vertically from the engine cowling had been bent to the left. He straightened it out and reported the problem solved. Before the plane could be considered fully mission capable, though, it had to undergo a functional check flight (FCF). The FCF pilot asked Dean to go along in the spotter seat behind the pilot. The two men flew until they found a deserted hut on stilts near a riverbank. Having been cleared to test the rockets, the pilot made a textbook approach toward the hut and fired two rockets, scoring direct hits and setting the burning hut adrift down the river. Unfortunately, the hut had not been completely deserted, but was occupied by a bunch of chickens who did not fare well in the blast. The pilot told Dean not to tell anyone what had happened, but somehow word leaked out. As a result, the pilot’s call sign was changed to Colonel Sanders and someone stenciled a dead chicken on the side of his airplane.

Despite arming planes daily with rockets, at times it was hard for Dean to remember he was in a war zone. His barracks was just across the road from where he worked, so going to work was easy. The mess hall always had hot food—it might have been powdered milk and powdered eggs—but Dean was keenly aware it was better than what the soldiers fighting in the jungle were getting. The base even had a beach designated as a U.S. Armed Forces Beach where people could swim or sunbath. The reminder of exactly where he was came in the form of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong mortar attacks, which happened frequently. The attacks were primarily aimed at the airfield and the planes, but occasionally 81-millimeter mortars would stray into the barracks areas. Dean knew if a mortar hit his barracks, it would turn out badly, but there was nothing he could do about it, so he didn’t dwell on it.

One very popular amenity on the base was a nine-hole putt-putt golf course built on the beach by the base’s Red Horse Squadron (a heavy construction unit). During most mortar attacks, it seemed like the NVA and Viet Cong saved their very last round for the putt-putt course, believing its destruction would adversely impact American morale. Dean said the attacks didn’t achieve their goal, though, because the putt-putt course was often the first thing repaired and back in action after an attack.

Dean in Nha Trang

Dean in Nha TrangFor Christmas 1968, Barbara sent Dean an eighteen-inch, fully decorated Christmas tree. Dean’s barracks chief permitted him to plug in the lights as long as he was in his quarters, so it brought a touch of Christmas cheer to Dean’s home away from home. The chapel also helped bring in the holiday by building a nativity scene on a grassy spot just outside the chapel. To represent Mary, Joseph, the baby Jesus, and the three wise men, the chapel wrote the Spiegel catalog company and it sent the chapel mannequins. The parachute shop made costumes for the mannequins and the nativity scene turned out beautifully. One night after it had been set up, two or three mortars hit right outside the chapel and blew the nativity scene apart, destroying all the characters except the baby Jesus. Dean said the following Sunday, there were a lot of extra people attending services at the chapel!

One other memorable Christmas event involved Dean’s selection to attend the Bob Hope USO Christmas Show being held on December 23rd at Cam Ranh Bay. He and the other airmen lucky enough to go were loaded into a truck for the twenty-seven mile drive south along the coastal highway. Everyone was particularly excited about the prospect of seeing Ann-Margret, so all were equipped with their cameras and lots of film. None, however, carried a weapon, so they joked the truck could have been commandeered by a Viet Cong guerilla with a pocketknife. Fortunately, that didn’t happen, and Dean and his friends enjoyed the show and made it back safely.

Because of his background in electronics, Dean was especially suited for working with the rocket launcher’s control system and wiring. On his own initiative, he developed a way to test the adequacy of the voltage being sent through the launching system, which earned him a certificate and a twenty-dollar bonus from the Air Force’s beneficial suggestion program. His knowledge was really put to the test when his squadron was tasked with completely rebuilding a Bird Dog badly damaged in a crash. The plane was in such bad shape that it had to be airlifted back to Nha Trang by a heavy-lift helicopter.

Dean’s NCOIC (non-commissioned officer in charge) asked him if he thought he could rewire the rocket launcher system by himself. Dean responded “absolutely” and spent the next two days doing so. When he finished, though, the system wasn’t registering the required voltage. Dean checked everything but couldn’t find the problem. Finally, he reported his failure to his NCOIC. Rather than chew him out, Dean’s NCOIC told him to take a break and come back in a couple of days with a clear head. Dean did, and to his surprise, the system worked flawlessly without him doing a thing. He initially suspected his NCOIC had found the problem and fixed it on his own, but his NCOIC assured him he had not. They then discovered what the problem was—the voltage meter Dean had used to test the system the first time had a faulty fuse. Now that he was testing with an accurate voltage meter, his rewiring of the system proved perfect.

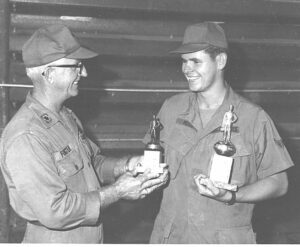

Dean receiving his 7th Air Force Munitions Maintenance Mechanic of the Quarter and Semi-Annual awards

Dean receiving his 7th Air Force Munitions Maintenance Mechanic of the Quarter and Semi-Annual awardsDespite being just an Airman First Class (E-3), Dean was recognized as an expert in his field. He was selected as the 7th Air Force Munitions Maintenance Mechanic of the Quarter and received a similar semi-annual award. He also taught and certified Airmen assigned to Forward Operating Locations on safely handling explosive ordnance and loading aircraft rockets. For his final Airman Performance Report, Dean was ranked in the top 1% of Airmen, making him feel very proud.

Consistent with tradition, Dean marked the beginning of his final month in South Vietnam by wearing the ribbon from a bottle of Seagram’s VO whiskey on the top button of his uniform shirt. One week prior to departure, he tied the ribbon into a bow. Finally, in May 1969, one year after arriving at Cam Ranh Bay, Dean boarded an outbound flight and departed South Vietnam for home.

Dean’s flight landed at McChord Air Force Base and he and five other service members hired a taxi to the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. On the way there, the taxi rear-ended another vehicle and Dean hit his knee on the front console, causing him to limp slightly when he finally got out of the cab. At the airport, the only welcome Dean received was from war protestors, who heckled him as he limped along. One individual stayed close behind him, but Dean ignored him until the man called him a “baby killer”. Dean turned around and said, “I’m not a baby killer, so back off and leave me alone.” The protester responded by spitting in Dean’s face. Dean still has the scar on his hand from where he broke the heckler’s nose.

Dean returned to Atlanta and into Barbara’s welcoming arms. Because he had enlisted instead of being drafted, he still had two-and-a-half years to serve on his enlistment. The Air Force assigned him to the 428th Tactical Fighter Squadron at Nellis Air Force Base, so he and Barbara packed up and moved to Las Vegas, Nevada, to complete Dean’s service commitment. Dean was honorably discharged in September 1971 after turning down a $10,000 variable reenlistment bonus. He was ready for his civilian life to begin.

Dean Moss today

Dean Moss todayAfter being discharged, Dean and Barbara returned to Atlanta, where Dean took a job with a medical supply company. The job was short-lived because in June of 1972, Dean received a call from the federal government offering him a position with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) working on instrument landing systems. Dean took the job and in 1977, relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he stayed with the FAA until he retired in 2009.

On Dean and Barbara’s 40th wedding anniversary, they began an amazing year-long journey together. Remembering they had written each other every day when Dean was in Vietnam, they went into their attic and retrieved the letters they had sent each other, having saved them in a box for all of these years. Instead of reading them all at once, they read the letters to each other on the same day they were written forty years before. The year-long experience rekindled so many memories for Dean that he began to take notes, creating a detailed journal of his experience in Vietnam. Dean used the journal to write a fascinating memoir of his year in Vietnam. You can read Dean’s memoir, The Other Side of the World, for an even deeper understanding of his service in Vietnam.

Dean and Barbara have two sons. David, the youngest, is serving as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force. When David deployed to Iraq and had to spend a Christmas there, Dean and Barbara retrieved from the attic the Christmas tree Barbara had sent to Dean in Vietnam almost fifty years before. That little Christmas tree has thus brightened the spirits of two generations of service members in two war zones. Dean and Barbara’s other son, Scott, is serving as a Captain in the Navy. Sadly, Dean’s beloved wife, Barbara, passed away in 2020. They had been married for fifty-two years.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Staff Sergeant Dean Moss, U.S. Air Force, for his distinguished service in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Although far from home and the people he loved, he dedicated his heart and soul to his duties, making sure the systems he was responsible for functioned properly, saving American lives. We are proud of what Dean has accomplished in his life and wish him fair winds and following seas.

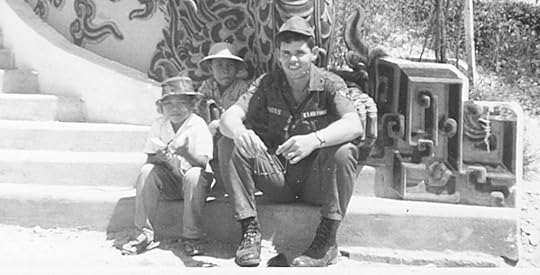

Dean with some boys in Nha Trang

Dean with some boys in Nha Trang

October 13, 2021

ETN3 Eugene Walker, U.S. Navy – Right Place, Right Time

Some people have a knack for telling stories. When you listen, you can’t help but share in their excitement as they reveal an unexpected outcome or describe an event that made a difference in their lives or the lives of other people. Petty Officer Third Class Eugene Walker, U.S. Navy, has the storytelling gift. If he were a guest at your home, you would easily listen for hours as he regaled you with stories about the places the Navy had taken him, the people he’d met, and the things he gotten to do. If you asked him to sum it up when he finished, you’d watch him get emotional and declare his service in the Navy opened doors for him throughout his entire life. This is his story.

Gene was born in Canton, Illinois, in July 1943. Soon after his birth, his father joined the Navy and was dispatched to the West Coast to join his ship, the escort carrier USS Altamaha (CVE 18). Gene’s father took his young wife with him, but they left Gene with his paternal grandparents, Wayne and Dale Walker. Gene’s parent’s marriage did not survive the war and, with Gene’s father deployed, Gene’s mother wrote Wayne Walker and told him she could not take Gene back. In her letter, she asked if Wayne and Dale could take care of Gene for her, which they did, raising Gene as if he were their own son.

Gene began at a very young age helping around his grandparent’s farm. He fed and groomed the animals and even learned to drive a tractor when he was six years old. He started first grade in a one-room schoolhouse, but then his grandparents moved in 1950 to another farm in Ipava, Illinois, a small town located about 175 miles southwest of Chicago. This move allowed Gene to finish school in a larger school district enrolling students from Ipava, Vermont, and Table Grove, Illinois.

All through elementary, middle, and high school, Gene worked hard on the farm. If the buildings needed repair or the barn’s roof needed patching or new shingles, Gene and his grandfather did it themselves. Needless to say, the work around the farm kept Gene in great shape, so it was only natural that he played football and ran track for VIT High School. Gene graduated from high school in the spring of 1961, one of forty-four VIT “Hornet” seniors to graduate that year.

Gene’s father, Eugene W. Walker, Sr.

Gene’s father, Eugene W. Walker, Sr.After high school, Gene attended Canton Community College beginning in the fall of 1961. He attended on a scholarship and graduated in the spring of 1963 with an Associate of Arts degree in Agriculture. With his new degree in hand, he returned to working on his grandfather’s farm. He was concerned, though, that with the U.S. involvement in Vietnam growing, he might be drafted into the Army or the Marines, which he did not see as favorable options. His friends told him the best option would be to enlist in the Air Force or the Navy. Gene heeded their advice and, influenced by his father’s service in the Navy, visited a Navy recruiter in Canton, Illinois. He liked what he heard and agreed to enlist.

Given the small rural environment, Gene needed to travel to Naval Station Great Lakes to get his enlistment physical and sign the enlistment contract. To make that happen, Gene’s grandfather dropped him off with the recruiter on the morning on November 18, 1963. The recruiter took him to the Naval Station, where he began the intake process the next day. When it came time for the eye exam as part of his physical, the optometrist told him to stand behind a line on the floor, take off his glasses, and read the smallest line he could see clearly. Gene did as instructed and replied, “I can’t read anything, sir.” Unfazed, the optometrist told Gene to start walking toward the eye chart and let him know when he could read the letters. Gene got to within two feet of the wall and announced that he could now read the giant “E” on the chart. Seeing that Gene was acutely nearsighted, the optometrist announced, “we can’t use you.”

Gene was devastated. He’d told everyone at home he’d joined the Navy and would now have to go back and let them know the Navy rejected him. Then, a First Class Petty Officer who’d been helping him navigate the intake process asked Gene if he wanted to go home. Gene told him, “No”. The First Class Petty Officer responded, “well you aced the math test and the only thing you’ve not passed is the eye exam, so let’s see if there is anything we can do.” He took Gene back to the optometrist and asked if there was any way the optometrist could let Gene in. The optometrist thought for a moment and said, “if he promises to keep two pairs of glasses with him at all times, I’ll pass him.” Gene readily agreed. With the final hurdle out of the way, Gene raised his right hand with the other recruits being inducted that day and took the oath of enlistment.

The First Class Petty Officer who had saved Gene’s enlistment wasn’t finished yet. He told Gene it was his lucky day. Because he had scored so high in math, he had the choice of attending boot camp at the nearby Recruit Training Center at Naval Station Great Lakes where the winter temperatures were beginning to take hold, or he could attend boot camp at the Naval Training Center in sunny San Diego. Either way, after boot camp he would go to school at Naval Station Treasure Island in San Francisco to learn to be an Electronics Technician. Gene chose San Diego and soon found himself with other lucky Navy and Marine recruits on a plane departing Chicago’s O’Hare Airport en route to San Diego.

Gene and the other new recruits arrived in San Diego at 2:00 a.m. on the morning of November 20. As the service representatives weren’t ready to take charge of their newest recruits, they told the Marine recruits to file off the plane and line up on the right and had the Navy recruits file off the plane and line up on the left. As soon as the Marine representatives arrived, they started chewing out their recruits, just like Gene had seen in the movies. Watching that reinforced his decision to enlist in the Navy—he was glad he wasn’t one of those poor Marine recruits.

Two days after Gene started boot camp in San Diego, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Not knowing what would happen in the country or what the military might be called upon to do, Gene wondered what he had gotten himself into. Fortunately, his training company was strong and he was designated a platoon leader, so training went well. He learned to handle the M1 Garand rifle, which his company marched around with during the course of the day. The recruits also quickly learned the rifle had another purpose. If they messed up on something, they would have to run around the grinder with the heavy M1 rifle above their head. The sanction had the desired affect and everyone did their best to avoid it. Then, on December 13, 1963, Gene received a notification through the Red Cross that his grandmother, Dale Walker, had passed away. He was granted emergency leave and attended his grandmother’s funeral in Lewiston, Illinois, in his Navy dress blue uniform. The burial at the cemetery was bitter cold; the temperature was five degrees below zero.

After the funeral, Gene returned to San Diego to complete boot camp. His former company had continued training in his absence, so Gene was assigned to a new company to make up the training he had missed. Since he knew none of the men in the new company and they had already bonded prior to his arrival, Gene set his sights on just getting through the training.

As boot camp graduation drew near, a Chief Boatswain’s Mate approached Gene out of the blue and told him he had a friend that Gene knew and he wanted Gene to invite the friend to graduation. He told Gene to write the friend a letter and tell her it was okay to come. Gene did as instructed, which is how Gene’s mother was able to attend his graduation. This was just the third time in twenty years Gene had seen his mother.

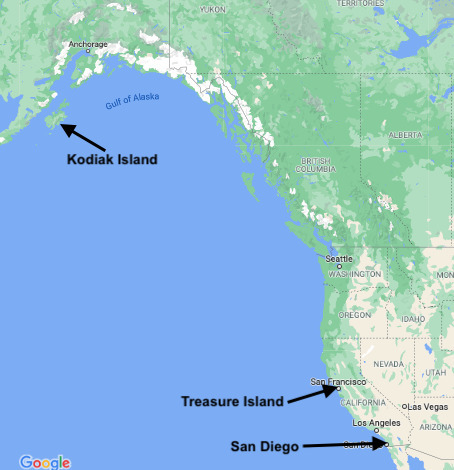

Gene’s initial assignments on the West Coast

Gene’s initial assignments on the West CoastGene graduated at the end of February 1964 as a full Seaman (E-3) because unlike most of the other recruits, he had completed two years of college. After graduation, he took two weeks leave in Illinois and then reported to Naval Station Treasure Island for Electronics Technician “A” school around the first of March. Life as a Seaman at Treasure Island was pretty good, although he did occasionally have to stand duty on weekends. One weekend he was assigned as the Battalion Runner, which meant he had to drive all around Treasure Island delivering messages to various commands. One of the messages he had to deliver was addressed to the Navy Brig. When the Duty Petty Officer handed him the letter to deliver, he told Gene to be sure he knew his general orders before delivering the letter because the brig was sure to ask Gene about them.

When Gene arrived at the brig, a brig Petty Officer brought him inside. In front of him were two lines on the floor—one blue and one red. Gene also saw two sailors, each holding up a five-inch shell with outstretched arms. Both were sweating profusely and struggling to hold the heavy shells at arms-length. The brig Petty Officer barked an order at Gene not to cross the blue line without permission, which Gene had no intention of doing anyway. The Petty Officer then asked Gene to recite the seven general orders, which he did. At that point, the situation relaxed and Gene asked the Petty Officer why the two sailors were holding the shells. The Petty Officer responded, “They didn’t listen. You’re dismissed.” That was all Gene needed to hear and he quickly departed. He was glad to never step foot in a Navy brig again.

On another weekend in March 1964, Gene felt like his hair was getting a little shaggy, so he went to the base barber shop to get a haircut. Apparently, there were lots of other sailors who felt the same way because the waiting line for a haircut ran all the way out the barber shop’s door. Gene dutifully went to the end of the line to wait his turn. While he was standing there, one of the two barbers reserved for cutting officers’ hair (so officers wouldn’t have to wait long to get haircuts) came out of the shop and walked up to Gene at the end of the line. He said he wasn’t cutting any officer’s hair just now and he could cut Gene’s hair on the condition that Gene not say anything to anybody about it. Gene agreed and walked into the shop with the barber, taking his seat in the officer’s chair.

After the barber started cutting Gene’s hair, a Marine Sergeant Major “dressed to the nines” in his meticulous Marine uniform rushed into the shop and approached Gene’s barber and the other barber reserved for cutting officers’ hair (his chair was empty). “Sirs, the Admiral wishes to get his hair cut,” the Sergeant Major announced. Gene was mortified. The one time he’d bent the rules and now he, a Seaman only a month out of boot camp, was going to be caught getting his hair cut in the officers’ chair by an admiral. Before he could get out of the chair, a gray-haired older gentleman walked into the shop and approached him. “Hello, sailor,” he said. “Where are you from?” Gene responded, “Ipava, Illinois, sir.” The man answered, “We’ll, I must admit I don’t know where that is. What’s your name?” Now standing, Gene responded, “Walker, sir. Eugene.” “Well, I guess you don’t know who I am,” the man continued. Gene admitted he did not. The man replied, “Chester Nimitz”. Gene could not believe it. He was actually speaking to Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the legendary U.S. Admiral and architect of the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s victorious naval campaign in World War II. Gene shook the Admiral’s hand and then the Admiral got his hair cut in the other chair. This was an experience Gene would never forget—he had been at the right place at the right time. Admiral Nimitz would pass away two years later and be buried next to his wife at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. The cemetery would later prove to be significant for Gene and his family, as well.

The Buskin Lake transmitter site on Kodiak Island

The Buskin Lake transmitter site on Kodiak IslandGene completed Electronics Technician “A” school in approximately six months. He was now ready for his first assignment, which was the Buskin Lake Transmitter Site on Kodiak Island, Alaska. As soon as he received his orders, he had to check an atlas to see where Kodiak Island was. He took leave in Illinois, then boarded a plane at O’Hare Airport in Chicago and flew to Anchorage, Alaska, via Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. In Anchorage, he boarded a Navy Albatross seaplane for the final leg of the journey to Kodiak Island, located in the Gulf of Alaska 30 miles off Alaska’s southern coast and 250 miles southwest of Anchorage.

Gene’s tour of duty at the Buskin Lake Transmitter Site began in September 1964. The site was a major communications facility supporting the Navy’s communications throughout the Pacific. As Gene’s rate (the Navy term for a sailor’s occupational specialty) was Electronics Technician Communications, the assignment was tailor-made for him. He worked on transmitter equipment, ran jumpers, did troubleshooting, repaired or replaced anything that broke, and used test equipment to make sure Navy communications in the Pacific flowed uninterrupted. This was a challenge because the equipment was old analog equipment, but also exciting because the Navy was beginning to move to more sophisticated electronics. The result was Gene gained valuable experience during his time on the island.

Given Buskin Lake’s remote location, there was little to do outside of work. The weather was surprisingly mild and Gene found it similar in many respects to the temperatures he had grown accustomed to growing up in Central Illinois. In the summer, he was able to go on hikes with his friends into the surrounding countryside, which was largely untouched by civilization. However, they had to carry weapons with them to fend off any bears they might encounter. In fact, it was not uncommon to see bears on the installation rummaging through trash dumpsters in search of food. They also had a pool table and ping pong tables to pass the time, and the installation would show movies. The radio station at nearby Naval Air Station Kodiak added music to the entertainment mix.

Gene (right) and friend trying on officers’ covers

Gene (right) and friend trying on officers’ coversOne thing the Buskin Lake Transmitter Site did have was outstanding food. The Buskin River was packed full of King Salmon, and Alaskan King Crab were also readily available. With those fresh catches at his disposal, the cook at the galley made sure the men ate well. So well, that when officers from Naval Air Station Kodiak visited the Buskin Lake facility, the lieutenant in charge always took them to the galley to eat. During one such visit while the officers were eating, Gene and two of his friends saw the officers’ covers (the Navy term for hats) in the galley’s outer area. They took turns trying them on and one of them took a picture. They were glad they didn’t get caught as they were sure the lieutenant would have “had their asses.”

Gene’s one-year tour on Kodiak Island came to an end in September 1965. He requested to extend but it was disallowed because it was his turn for sea duty. He received orders to report to USS Chevalier (DD-805), a World War II era Gearing class destroyer currently in drydock at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco. Before reporting to his new ship, he again took leave in Illinois. Then, with all of his possessions loaded into his green canvas sea bag, he flew from St. Louis to San Francisco and joined his ship at the end of September 1965.

Gene really enjoyed his time on USS Chevalier. Because he was an experienced Electronics Technician, he didn’t have to work in the ship’s galley like the other junior enlisted sailors did upon first reporting to the ship. Instead, he jumped right into working on the ship’s communications gear, making sure the ship could communicate reliably with the rest of the fleet. He also helped work on the ship’s radar antennas, not because of any special training he had, but because he’d told some of his new shipmates about his life growing up on his grandfather’s farm. One day, Radarman Second Class Jim Lorenz approached him and said “I hear you used to work on barn roofs and aren’t afraid of heights. When work needs to be done on the radar antennas on the ship’s mast, I need someone to go with me and the other guys are scared.” From then on, Gene climbed the ship’s mast with Petty Officer Lorenz to work on the antennas. It was perilous work when the ship was at sea, especially when the ship rocked from side to side. When the ship rolled to port (left) and Gene looked down, all he could see was water. When the ship righted and he looked down, all he could see was the center of the ship. When the ship rolled to starboard (right) and he looked down, again all he saw was water. The work was not for the fainthearted.

USS Chevalier (DD 805) Source: U.S. Navy

USS Chevalier (DD 805) Source: U.S. NavyOn May 12, 1966, USS Chevalier departed San Diego for a deployment to the Western Pacific. On the way there, they stopped at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, before making the long voyage to the Yokosuka, Japan, as part of the aircraft carrier USS Constellation (CV 64) task group. Throughout the six-month deployment with USS Constellation, USS Chevalier would often serve as “plane guard” for the giant aircraft carrier when it conducted flight operations. This meant USS Chevalier would take station near the carrier and be ready to rescue any aircrew in the event one of USS Constellation’s aircraft made a water landing. USS Chevalier had a diver onboard who would jump into the water near the downed aircraft and attempt to rescue any survivors before the aircraft sank. Gene only remembers a one occasion where a rescue was attempted but the pilot did not survive.

After a brief stay in Yokosuka from June 1-7, the Chevalier got underway again with the other ships in the Constellation’s task group heading for Vietnam via Subic Bay in the Philippines. When the Chevalier arrived off the coast of South Vietnam, it detached from the task group and sailed up the Saigon River. Because Chevalier’s draft was only fourteen feet, four inches, it could navigate in the river’s shallow water. Once it sailed past Saigon, it provided fire support the troops ashore by bombarding enemy targets. To ensure Chevalier’s guns hit their targets, spotter planes radioed coordinates to the ship and the ship then blasted those areas with its six five-inch guns. The Chevalier wasn’t the only asset being called upon to assist the troops in the vicinity. On one occasion during the ship’s Saigon River mission, Gene watched as an AC-47 “Puff the Magic Dragon” gunship rained down machine gun fire, accented by thousands of tracer rounds, on the enemy ashore. During the period from June 15-21, USS Chevalier expended all of its five-inch ammunition in support of allied forces on the ground.

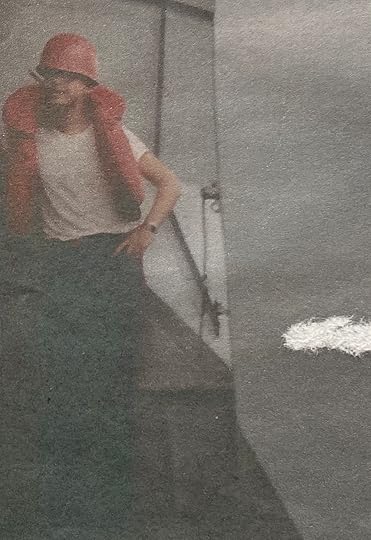

Gene onboard USS Chevalier (DD 805)

Gene onboard USS Chevalier (DD 805)After its gunnery support mission, USS Chevalier rejoined USS Constellation and resumed plane guard duties. Gene worked on equipment, but also spent time on the bridge in case any of the communications equipment went down and needed a quick repair. When the ship needed to resupply, it would sail close alongside a supply ship. While maintaining a steady course and speed, the ship would refuel and resupply from hoses and lines connected between the two ships. The evolution was dangerous, so the crew was placed at a heightened state of readiness. Gene’s replenishment position was amidships, where he could clearly see how well the replenishment was proceeding.

For one such replenishment, a new Lieutenant Junior Grade had the conn of USS Chevalier as she pulled alongside the resupply ship, USS Mars (AFS-1). Gene and the other crewmembers at his station thought the Chevalier was getting too close to the Mars until a First Class Boatswain’s Mate couldn’t take it any longer. He radioed to the bridge that they were so close he could reach out and touch the Mars from where he was standing. The Chevalier’s captain intervened and a safe distance was restored between the two ships.

After its duty in Vietnam, USS Chevalier headed home, retracing the steps it took on the way over. One difference, though, was the ship stopped in Singapore, which meant the ship crossed into the southern hemisphere. To mark the occasion, the ship’s crew held the traditional crossing the line ceremony, where sailors like Gene who had never done so before transitioned from uninitiated “pollywogs” to trusty “shellbacks”. The raucous ceremony is usually memorialized by a certificate issued by the Court of King Neptune and becomes a cherished part of a sailor’s memorabilia.

USS Chevalier returned to San Diego in October 1966. Gene would go out with the ship one more time on a trip to Acapulco, Mexico, which he thoroughly enjoyed. The ship then went into a maintenance and workup period as it prepared to deploy again to the Western Pacific in 1967. However, because Gene’s enlistment would expire while the ship was deployed, he transferred in May to the USS Hamner (DD 718), another Gearing Class destroyer homeported in San Diego.

Private Medford Adarine Chrysler, USMC

Private Medford Adarine Chrysler, USMCOn July 2, 1967, Gene’s mother called him with some very bad news. His brother, Medford Adarine Chrysler, had been killed in Vietnam. His mother asked him to attend the funeral, which was to be at the Golden Gate National Cemetery, the same place Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was buried. She also asked him to go to the morgue to identify the body, which Gene was able to do based upon a tattoo Medford had on his right forearm. Medford, a Marine who died fighting the North Vietnamese in Quang Tri Province near the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam, was buried with full military honors. This was the second funeral Gene attended in his dress Navy uniform.

Gene remained onboard USS Hamner until he accepted an early discharge in August 1967 to attend Southern Illinois University. At the time of his discharge, he was a Petty Officer Third Class. He attended Southern Illinois University as planned, but it wasn’t what he was looking for, so he returned to Ipava to work at his grandfather’s gas station. In 1972, he was ready to move on from that, too, and applied for a job with AT&T in Peoria, Illinois. While the clerk at the AT&T office told him they weren’t hiring, he submitted his application anyway. When he returned home, there was a message waiting for him from a Mrs. Dahl at AT&T.

Gene returned the call and Mrs. Dahl said she had seen his application. She asked him why he thought he would be a good fit for AT&T. When he told her he had been an Electronics Technician in the Navy specializing in communications, she asked him if he could start in two weeks. So began Gene’s thirty-four-year career with AT&T. His job took him from Illinois to California and back again, and he loved the work. He retired from AT&T in 2005.

Gene now lives in Springfield, Illinois, where he is active in VFW Post 755. Since joining the Post, he’s reached out to veterans in need by helping coordinate assistance through the Illinois Department of Veterans Affairs. When veterans pass away, he serves on the burial detail at Camp Butler National Cemetery and has performed countless burial ceremonies honoring veterans as they are laid to their final rest. He also is a Civil War reenactor, playing the role of Major John Aaron Rawlins, General Ulysses S. Grant’s Chief of Staff.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Electronics Technician Communications Third Class Eugene Walker for his dedicated service in the U.S. Navy. His service took him to two extremes, from a remote island off the coast of Alaska to the war in Southeast Asia. Wherever he was, he served with distinction, ably representing the United States. We thank him for all he has done for our country and wish him fair winds and following seas.

Gene portraying Major John Aaron Rawlins

Gene portraying Major John Aaron Rawlins

September 11, 2021

Command Chief Master Sergeant Dave Himmer, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) – Coming of Age in Vietnam