David E. Grogan's Blog, page 2

December 19, 2024

BMC Frank Tyree – Twenty Years in the Navy: From Yankee Station to the Persian Gulf

Navy sailors serve in hotspots around the world. When tense situations develop, one of the first questions on the president’s mind is, “Where are the Navy’s aircraft carriers?” In 1972, when the president needed the Navy to help stop the North Vietnamese Easter Offensive during the Vietnam War, Boatswain’s Mate Chief Frank Tyree, U.S. Navy (Retired), answered the call onboard the aircraft carrier USS Midway (CV-41). He answered the call many more times over the course of his long career, going wherever and whenever the Navy needed him. Yet the Navy is only one aspect of Frank’s public service—he continues to help those in need even today.

Frank came into this world with the military in his blood. His father was a career Army soldier who served two tours of duty in Vietnam. Earlier in his career, he was assigned to the U.S. occupation forces in Japan after World War II, where he met and married a Japanese woman. Frank was born to the couple in February 1953 when his father was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. Frank and his parents moved each time his father transferred to a new duty station, but eventually they settled in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Frank attended Magna High in Salt Lake City until his family moved a little farther west, where he attended West High School. When he wasn’t studying, he tried his hand at creative writing and participated on the debate team, taking third place in the state during his junior year. He also managed a gas station at the age of sixteen and worked for another company cleaning buildings so he could earn enough money to purchase his first car, a 1955 Pontiac Chieftain. It all made for enjoyable high school years, but with the likelihood of being drafted on the horizon because of his upcoming graduation and low draft number, Frank knew what he had to do.

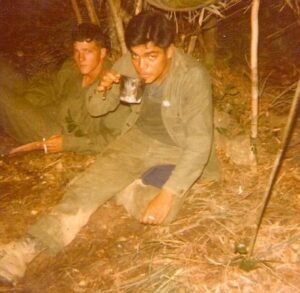

Frank Tyree during his senior year of high school

Frank Tyree during his senior year of high schoolTwo months before graduation, Frank went to a recruiter to enlist in the military. Although his father’s service influenced him to consider the Army, he often dreamed about sailing on a freighter to tropical islands in the South Pacific where warm ocean breezes and beautiful island girls awaited. His dreams won out, so he walked into a Navy recruiting office and told the recruiter he wanted to join the Navy. The recruiter said, “Sure, kid,” and asked Frank what kind of job he wanted. Frank told him he wanted to serve on submarines. Again, the recruiter said, “Sure, kid.” He then signed Frank up for the delayed entry program, which meant his enlistment would not begin until after he graduated from high school.

Frank graduated from West High School in May 1971 and reported for active duty on July 31. His parents saw him off at the Salt Lake City Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station, with his father rendering him a crisp salute as Frank prepared to depart on a bus for boot camp at Naval Training Center, San Diego. Frank instinctively returned the salute, boarded the bus, and began his Navy career.

Having come from an Army family, Frank found the initial transition to boot camp life easy. For example, he arrived in San Diego with a regulation military haircut, leaving the barbers little to cut off. He also knew he had to wake up early at reveille each morning and keep his gear in good order, so he was as ready as he could be for what lay ahead.

Despite Frank’s preparation, boot camp still posed challenges. Frank learned this firsthand when an instructor determined his rack (bed) was not made tight enough. To make a point, the instructor threw Frank’s mattress—bedding and all—out the window. He then told Frank to get it and bring it back on the double. Frank did as instructed, but when he returned with his mattress, the instructor told him to throw it out the window again. This drill repeated itself several times until the instructor was satisfied he had worn Frank out.

Firefighting training was an integral part of boot camp. During one training evolution, Frank stood on the deck of mockup of a ship with a fire burning below deck. As Frank prepared to extinguish the flames, an instructor yelled, “What’s the eighth general order?” With flames coming out of the hatch from the deck below, Frank’s mind went blank, and he didn’t respond. Again, the instructor yelled, “What’s the eighth general order?” Getting ready to panic as the fire grew larger, Frank remembered and responded, “Report fires—Fire, Fire, Fire!” Finally, the instructor permitted him to put out the blaze. Frank would never again forget the eighth general order.

Frank graduated from boot camp in October 1971 and reported to “A-School” for Personnelman (PN) training. There he learned the administrative skills he needed to process the mountains of paperwork required by Navy commands to account for their sailors and keep their service records up to date. He completed PN training in December and reported as a new seaman apprentice to the USS Midway (CV-41), a massive aircraft carrier commissioned during the final days of World War II. He arrived near the pier where the Midway was tied up late on a foggy night with near zero visibility. When he got close to the pier, he saw the gigantic ship’s bow breaking through the fog. The ship looked so big he was sure he’d get onboard and be lost forever. Still, he managed to check in and began learning the ropes in the ship’s personnel office the next day.

In April 1972, Frank and the other sailors working with him got to test their PN skills when the captain ordered an emergency recall to the ship of all personnel, including those on leave (vacation). North Vietnam had just launched a major offensive, known as the Easter Offensive, against South Vietnam, threatening the country’s survival. As part of the U.S. response, the USS Midway was ordered to deploy to Yankee Station, a location at sea off the coast of North Vietnam where U.S. aircraft carriers routinely operated during the Vietnam War. Its mission was to launch planes on bombing missions in support of Operation Linebacker, which was intended to bring an end to the Easter Offensive by stopping the flow of war supplies to the North Vietnamese forces in South Vietnam. Aircraft from USS Midway and other Navy aircraft carriers, as well as Air Force bombers, participated in the operation, which halted the North’s offensive and eventually helped force the North Vietnamese to negotiate seriously for peace in Paris.

The war proved both real and personal for Frank and his shipmates operating on Yankee Station. On the night of October 24, 1972, a Navy A-6 Intruder returning to the USS Midway crashed as it attempted to land on the carrier after completing a bombing mission over North Vietnam. The plane plowed into aircraft parked on the flight deck, killing four sailors and starting a large fire. The A-6’s bombardier/navigator also died after he ejected from the plane and was lost over the side of the ship. As general quarters sounded, Frank’s repair party reported to the hangar deck—the deck of the ship immediately below the flight deck—where bombs were positioned on dollies in preparation for being loaded onto aircraft. Now the bombs were at risk of exploding because jet fuel poured down from the flight deck onto the ship’s lowered aircraft elevator, which was used to transport aircraft between the flight deck and the hangar deck. One spark could set everything ablaze and detonate the bombs. To keep that from happening, Frank and the other sailors in his repair party pushed the bomb-laden dollies through a curtain of jet fuel raining down onto the lowered aircraft elevator and jettisoned the bombs over the side of the ship. They then walked back through the jet fuel and repeated the process until all the bombs were gone. When Frank finished, he was drenched in jet fuel and traumatized by the crash and the loss of his shipmates.

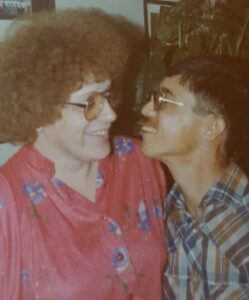

Frank and Sharon Tyree over the 1975 Christmas holiday

Frank and Sharon Tyree over the 1975 Christmas holidayLess than three months later, Frank took an offer to end his enlistment early. He received an honorable discharge in January 1973 and began attending classes at the University of Utah using his GI Bill. After a year, he decided college wasn’t working out and took a job as a truck driver. He also met and fell in love with a woman he met at a party, Sharon Lee Veatch, and they married thirty-nine days later, on November 4, 1975. When they were unable to have children themselves or adopt children because Frank didn’t earn enough money as a truck driver, they agreed Frank should join the Navy again so they could see the world together.

Reenlisting in the Navy proved harder than Frank expected. When he was honorably discharged early from his first enlistment in 1973, he had been given a reenlistment code that made it difficult to reenlist. This was intended to keep him from immediately reenlisting in return for bonuses or better assignments. Now, however, it was five years later, and those restrictions no longer applied. The Navy solved the issue by signing Frank to a two-year conditional enlistment and giving him orders to the USS Mobile (LKA-115), an amphibious cargo ship homeported in Seal Beach, California.

Another condition of Frank’s enlistment was that he was no longer a PN. Instead, he was an undesignated seaman apprentice who had to learn entirely new job skills. Accordingly, when he reported onboard USS Mobile, the ship assigned him to the Deck Division where he learned how to handle the rope lines used to launch and recover the ship’s boats. This was no small feat, as the two types of boats he worked with where fifty-six and seventy-four feet long, respectively.

Frank’s initial assignment was as a line tender, working behind the line handler to make sure the ropes didn’t entangle or injure him. On one occasion when Frank and his line handler were working below the ship’s bridge, the line handler felt ill and went to sick bay, leaving Frank on his own. Frank took over the line handler’s responsibilities, unaware the ship’s captain was watching him work from the bridge. After Frank finished the evolution, a first class petty officer told him the captain wanted to see him on the bridge. Frank reported to the bridge as ordered, wondering what he had done wrong. The captain did not chew him out—quite the contrary. He told Frank he’d been watching him work and asked if he would be willing to serve as the bow hook for his gig. Frank said he would, so the captain directed him to report to the boat group. When he got there, he told the petty officer in charge what had happened and then asked, “What’s a bow hook and a gig?” He soon learned the gig was the captain’s boat, and, as bow hook, it would be his job to keep watch at the boat’s bow and jump ashore with the bow line to secure the boat to the pier.

Working in the boat group, Frank learned everything he could about operating and maintaining the Mobile’s small boats. He worked hard on earning his coxswain qualification, so he would be able to drive the boats himself. That occasion came sooner than expected when an ensign got knocked over the side of the ship in Vancouver and fell into thirty-eight degree water. Frank and another sailor were in the captain’s gig ready to be lowered into the water, but the coxswain had not yet come aboard. With no time to waste, the gig was launched, and Frank took over the controls. He and the other sailor quickly made it to the ensign, who had drifted away from the Mobile in the strong current, and pulled him aboard. They then returned him to the ship, where the ensign was treated for hypothermia but was otherwise unhurt.

After Frank promoted to boatswain’s mate third class, he found himself in charge of the ship’s Second Division and its thirty seamen. This happened on short notice when the petty officer in charge of the division transferred, turning over his responsibilities to Frank one day before the ship’s captain conducted a zone inspection of the Second Division’s spaces. After assessing the spaces himself, Frank divided his sailors into three teams and directed them to get their spaces shipshape before leaving for the day. They finished by 8:00 p.m. and returned early the next morning for the inspection.

Frank escorted the captain through the division’s spaces, and the captain was impressed. However, at the end of the inspection when he turned to leave, he saw someone had spray painted “FTN” on a door, which everyone knew stood for F*** the Navy. The captain turned to Frank and said, “What is this?” Without hesitating, Frank replied, “It means Frank Tyree’s Navy.” The captain smiled and said, “Okay,” and walked out of the space. Frank Tyree’s Navy soon became a common phrase, even adorning the license plates on Frank’s motorcycle and car.

Frank Tyree working over the side of a ship

Frank Tyree working over the side of a shipAs Frank’s tour onboard USS Mobile drew to a close, he received orders to report to the U.S. Navy base in Yokosuka, Japan, known as Fleet Activities, Yokosuka. Accordingly, he detached from the Mobile in September 1984 and moved with Sharon to Yokosuka in November. Frank was assigned as a patrolman with the base’s military police. He also trained and qualified as the base traffic accident investigator.

Frank took his patrolman responsibilities seriously. One traffic stop in particular illustrated his approach. On this occasion, he pulled over a taxi for a traffic violation near a construction site. The driver was a sailor moonlighting to earn some extra money, and he told Frank he would be transferring to the military police to work with Frank in about a month. He then asked Frank if he could give him a break and not issue him a ticket since they would soon be shipmates. Frank explained that was not possible because to a military policeman, integrity was everything. He said if he played favorites, everyone would find out and his reputation would be irreparably damaged. He then gave the driver his ticket. One month later, the driver reported to the military police and began briefing prospective drivers on Japanese traffic laws. He used the story of Frank issuing him a ticket to reinforce the need for safety with Americans getting ready to drive in Japan, promising they would be ticketed if they did not obey the law.

During his time at Yokosuka, Frank investigated over 450 traffic accidents, arrested 90 drunk drivers, and issued over 1,000 tickets. Ten of the traffic accidents he investigated involved fatalities. Since all those fatalities involved alcohol, Frank had zero tolerance for drunk driving and worked hard to keep motorists on the Navy base safe. In fact, his stops for drunk driving included senior officers and even his own boss. For that reason, he built a solid reputation for honesty and fairness.

As the end of his enlistment neared, Frank had to decide whether to stay Navy or return to civilian life. Since it looked like he would be heading back to the USS Midway (which was now homeported in Yokosuka) if he reenlisted, he decided to get out because he did not want to be apart from Sharon during another long deployment. Accordingly, in March 1988, he and Sharon packed their belongings and returned to Salt Lake City.

Once back in Salt Lake City and with no concrete civilian opportunities, Frank and Sharon decided to give the Navy one more try. As Frank had been a boatswain’s mate first class at the time of his discharge, he had the experience the Navy needed. However, to maintain his previous rank upon reenlisting, he first signed with the Navy Reserve and then with the active Navy the following Monday. He then reported for Navy Veteran (NAVET) training at Naval Training Center, San Diego, where he was put in charge of physical training for all the Navy veterans returning with him to active duty. When he found many of those returning had forgotten what it meant to be part of the Navy team, he required the group to run in formation, never outpacing the group’s slowest members. The result was the group began working together as a unit rather than racing to the finish line as a bunch of individual sailors.

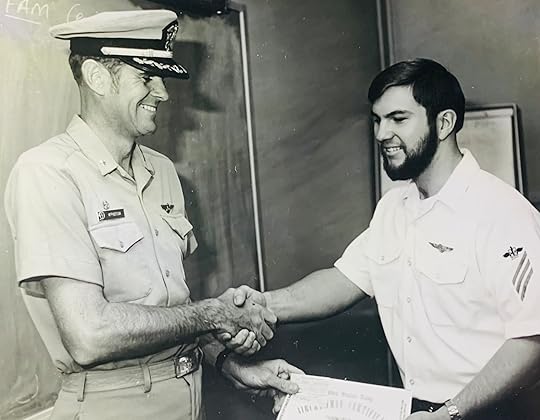

After completing NAVET training, Frank reported to the USS Proteus (AS-19), a submarine tender commissioned during World War II and homeported in Guam. Frank was assigned to the rigging locker, which meant he was responsible for properly rigging items to be hoisted by the ship’s massive cranes to and from nuclear-powered submarines. As at Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, he immersed himself in his work until he became the recognized rigging expert. Whenever the repair officer asked him if the rigging was acceptable and he said yes, the repair officer proceeded with the hoist without asking further questions. Similarly, if Frank said the hoist couldn’t be properly rigged for a safe lift, it wasn’t attempted. In recognition of his expertise and his years of Navy experience, Frank promoted to chief petty officer while onboard USS Proteus.

Frank’s expertise came in handy when the Gulf War loomed in January 1991. In anticipation of the start of hostilities, the nuclear-powered submarine USS Louisville (SSN 724) was given seventy-two hours’ notice to depart Guam to head to the Red Sea. The Proteus was charged with getting the Louisville ready to sail. Instead of taking seventy-two hours, Proteus completed the job in just twenty-four, allowing Louisville to reach her destination on time. Louisville then launched cruise missiles in the war against Iraq, becoming the first submarine to do so in combat.

Frank and Sharon lived in base housing on Guam until it came time for Frank to transfer in 1992. This time, Frank received orders for recruiting duty. After completing Recruiting School, he was put in charge of the Navy Recruiting Office in Ogden, Utah. When that office closed, he transferred to the Navy Recruiting Office in Salt Lake City. When it was announced that office would transition to officer recruiting, Frank was put in charge of preparing the office for the transition. During that time, Frank scored a major victory by recruiting a naval reactor engineer from Brigham Young University. Since naval reactor recruits often came from Ivy League schools in the northeast, this was a significant accomplishment for Frank and his office.

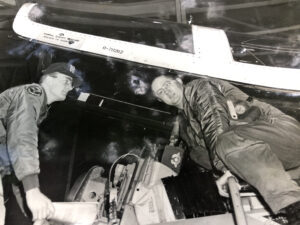

Photo taken by Frank Tyree of the USS Essex during its overhaul in 1997

Photo taken by Frank Tyree of the USS Essex during its overhaul in 1997When it came time for Frank to transfer again in 1994, he accepted orders to the USS Essex (LHD-2), homeported in San Diego. The Essex was a new amphibious assault ship commissioned in 1992 and designed to carry Marines, helicopters, and Harrier attack aircraft. Frank joined the ship in Hong Kong during its first deployment late in 1994. The highlights of the deployment involved rounding up a freighter trying to escape from the United Arab Emirates to Iran and, in January 1995, successfully covering the withdrawal of UN troops from Somalia.

Frank made one final deployment to the Persian Gulf onboard USS Essex commencing in October 1996. In addition to participating in several multinational exercises, the ship and its embarked Marines participated in Operation Southern Watch, enforcing the no-fly zone over Iraq. This meant the ship had to spend Christmas anchored off the coast of Kuwait in the Persian Gulf while the ship’s Marines were ashore. Since the ability to celebrate Christmas was limited ashore, the ship put on a big pageant telling the Christmas story. To make sure everyone could participate in the festivities, the ship’s Marines in Kuwait flew back to the ship in groups for a hot shower, a Christmas meal, and the opportunity to watch the pageant.

Frank had two sailors from the Deck Department participating in the pageant—both were playing the shepherds to whom an angel appeared announcing the birth of Christ. However, when the angel spoke to them, they both forgot their lines and had to improvise. The first sailor said, “Wow, did you see that?” The second, a young sailor with a thick Oklahoma accent and unique way of pronouncing words, responded, “Yeah man. That ‘war’ an angel!”

The two sailors’ unscripted dialogue had a profound impact on Frank. Their words, coming from the heart rather than the script, made the pageant seem even more real. So much so that Frank wrote about the story several years later to memorialize it forever. For him, it was the highlight of his second deployment on USS Essex.

The Essex returned to San Diego in April 1997. After a post-deployment standdown which allowed the returning sailors to spend time with their families, Frank, the leading chief in the Deck Department, helped coordinate a short overhaul. He then had a big decision to make. He had always told himself he would do his twenty years, retire, and spend the rest of his time with his beautiful wife. Although the chain of command tried to entice him with his likely promotion to senior chief petty officer, he decided to hold true to his plan and submit his retirement papers. In his final week, he also earned his Enlisted Surface Warfare Specialist pin, documenting the vast experience he’d gained over the course of his long career.

Frank officially retired in 1998. Although he and Sharon envisioned returning to Salt Lake City, his best friend onboard USS Proteus recommended they come to Springfield, Illinois, instead. This sounded good to Frank and Sharon because Sharon had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1980 and the Illinois climate seemed more agreeable to her condition. The move worked and Frank and Sharon have lived there ever since, although Sharon finally succumbed to MS and passed away in 2022 after fighting the disease for over forty years.

Despite retiring from the military over twenty-five years ago, Frank remains deeply connected to his Navy service. Part of his connection is rooted in the events surrounding the crash of the A-6 Intruder onboard the USS Midway in 1972. The loss of his shipmates and the bombs he had to carry through curtains of volatile jet fuel caused him to suffer from PTSD, which he deals with by writing poetry about his service experience. He also paid tribute to his lost shipmates in 2024 when he participated in an Honor Flight for veterans to Washington, D.C. When the Honor Flight veterans visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Frank located all five of his lost shipmates’ names on the wall. Frank is also an active Service Officer with his Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) post—first with Post 10302 and later with Post 755. In this role, he assists veterans, their families, and anyone else in need. For example, he’s helped homeless veterans get off the streets and into permanent housing and delivered free medical equipment to those who cannot afford to purchase it on their own. Frank makes himself available to anyone who needs a helping hand.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Boatswain’s Mate Chief Frank Tyree, U.S. Navy (Retired), for his years of dedicated service to our country. A proud Vietnam veteran, Frank answered our country’s call during both peacetime and time of war. His service took him to many far-off places around the globe, where he endured long deployments away from family and friends. We thank Frank for all he has sacrificed and for his continued service to his community. Most of all, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Frank’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

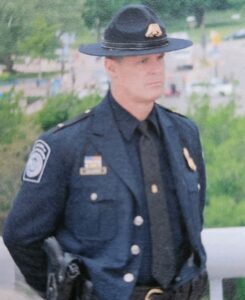

Boatswain’s Mate Chief Frank Tyree, U.S. Navy (Retired), rendering honors in 2024 for a World War II veteran who had passed away

Boatswain’s Mate Chief Frank Tyree, U.S. Navy (Retired), rendering honors in 2024 for a World War II veteran who had passed away The post BMC Frank Tyree – Twenty Years in the Navy: From Yankee Station to the Persian Gulf first appeared on David E. Grogan.

November 6, 2024

Chaplain, Colonel, Marion Reynolds, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) – Faithfully Serving Those Who Serve

Long deployments, work with nuclear weapons, the burden of killing or being killed, and a host of other factors combine to place unique pressures on military members. Fortunately, people like Chaplain, Colonel, Marion Reynolds, Chaplain Service, U.S. Air Force (Retired), feel called by their faith in God to help military members and their families cope with their stress. After serving five years as an enlisted airman, Marion served for twenty-three years as a chaplain, reaching out to airmen where they needed him most. He met with them at the alert facility as they waited for orders on what could be one-way missions. He spoke to them in silos with nuclear-equipped missiles standing at the ready just a few feet away. He consoled them at isolated duty stations around the world whenever they received bad news from home. And, most importantly, he walked in their shoes.

Marion was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in December 1937. His parents divorced when he was five, beginning a series of moves to multiple states he and his younger brother would make over the next ten years as they alternated living with their mother, their father, and other relatives. When Marion was nine, he went to live with his Great Aunt Nellie. She was a very religious person, and she had a profound effect on him. So much so that when Marion turned ten, he was baptized at the Carlisle Avenue Baptist Church in Louisville. He then went to live in Vincennes, Indiana, with his father, stepmother, and their two boys after they returned from working in Europe.

When Marion’s father took a job with the Wabash River Ordnance Works, the family moved to Dana, Indiana, a small town close to the Illinois border. Marion attended his first two years of high school at Dana High before his family moved to Joliet, Illinois, after his dad received a promotion. Marion spent his junior year at Lockport High School in Joliet and, after moving to Plainfield, Illinois, attended Plainfield High School his senior year. Given all the moves, Marion had no time to participate in organized high school activities, but he did manage to hold down a job at a local grocery store during his senior year.

One thing Marion did have time for was his love of aviation. Ever since he was a little boy, he was fascinated by airplanes. He built models with his dad, helping cement their bond. As Marion grew older, his love of aviation turned into a desire to enlist in the Air Force. By the time he graduated from Plainfield High in the spring of 1956, his desire to enlist had become his plan. He spent the summer with his mother and then signed up with the Air Force in October.

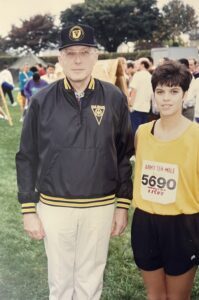

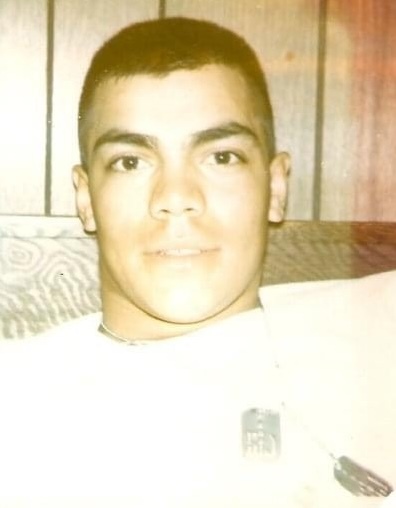

Marion Reynolds on leave in January 1957 after basic training

Marion Reynolds on leave in January 1957 after basic trainingMarion’s Air Force experience began at the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Chicago. After examinations proved he was physically and mentally qualified to serve and he took the oath of enlistment, he boarded a train for basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. Although he did well at the training, the aspect of his time at Lackland that affected him most was his interaction with the chaplains. The interaction began when he attended services at the base chapel on Sundays and expanded to other chapel-sponsored events as the weeks went on. The experience reinforced the interest his Great Aunt Nellie began when he was nine years old.

After graduating from basic training, Marion transferred to March Air Force Base outside of Riverside, California. Based on aptitude tests, he had been selected to work in a classified program with the Air Force intelligence community. He spent nine months at March learning his new trade, but, again, the most significant impact came from his participation in base chapel activities, including a single airman’s group. In fact, the impact was so strong, Marion felt called to become an Air Force chaplain.

As Marion’s training drew to a close, it came time to see where the Air Force would send him to put his new skills to use. The program he trained for offered two alternatives: at a base in Germany or at Fort Meade, Maryland. Fort Meade had several advantages if Marion were to pursue becoming a chaplain. First, his uncle was a pastor at a church about seventy miles south of Fort Meade, so Marion could learn what being a pastor entailed by visiting on weekends. Second, he could take on-base evening classes at the University of Maryland to begin fulfilling the educational prerequisites he needed to become a chaplain.

Not knowing which assignment he would get, Marion told himself if his orders were for Fort Meade, that was a clear sign from God he should pursue his dream of becoming a chaplain. Several days before his scheduled departure, he received his orders—he was on his way to Germany. Initially wondering if this meant he was mistaken in his sense of calling, he gradually determined he was still being called to the chaplaincy but would need to satisfy the educational requirements some other way. Then, he and the other airmen heading to Europe boarded a bus to go to the base clinic to get the shots they needed for their assignments overseas. As the bus started rolling, a sergeant ran after the bus and got it to stop. He climbed aboard and announced orders had been changed for ten people, including Marion. He was now on his way to Fort Meade.

Marion arrived at Fort Meade in November 1957. He stayed there for almost four years working on the classified program he’d trained for and promoting to senior airman. He lived in the barracks and, as per his plan, completed two years of college at the University of Maryland. He also visited his uncle’s church on weekends. During one such visit, his uncle introduced him to a young woman they had seen walking across the parking lot while they were talking on the church’s front porch. The woman’s name was Nancy, and she and Marion were married two years later in June 1960.

Marion and Nancy Reynolds on their wedding day

Marion and Nancy Reynolds on their wedding dayReady to pursue his calling in earnest, Marion was discharged from active duty in June 1961. He and Nancy moved to Moline, Illinois, so Marion could complete his bachelor’s degree in history at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. Marion specifically picked Augustana because it was a Lutheran school and he wanted to diversify his religious background knowing that once he became a military chaplain, he would be responsible for ministering to servicemembers of all faiths. To keep food on the table, he sold life insurance and worked at the college’s power plant on the 5:00 p.m. to midnight shift. Nancy worked, too, as a certified practical nurse. She also gave birth to their first daughter, Leslie, while Marion was enrolled at Augustana.

After graduating from Augustana College in the spring of 1963, Marion and his family moved to Louisville so Marion could attend the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Being back in Louisville allowed him to spend time with Great Aunt Nellie, who was immensely proud her tutelage of nine-year-old Marion had helped turn him into a pastor. Nancy also gave birth to their second daughter, Lauren, during Marion’s time at the seminary.

Marion graduated from seminary in January 1967. He’d already been serving for a year as the pastor of Swallowfield Baptist Church, a small, rural church about sixty miles from Louisville. He worked there on weekends both before and after graduation until he had sufficient pastoral experience to apply to become a military chaplain. After graduation, he moved to Frankfurt to better serve the church. He also worked for the Kentucky Department of Public Assistance, providing him with a steady paycheck. Then, in August 1968, after receiving an endorsement from the Southern Baptist Convention Chaplain’s Commission, Marion got the news he’d been waiting for—he’d been accepted into the Air Force chaplain’s program. He commissioned as a 1st lieutenant that same month and promoted to captain when he came on active duty on November 12.

Although Marion hoped his first assignment would be in Florida near where his mother lived, the Air Force sent him in the opposite direction to Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota. After his previous service, Marion felt like he was coming home when he stepped foot on the base, which served bomber, fighter, tanker, helicopter, and missile squadrons. Others recognized his enlisted experience, too. On Marion’s second day on the base, a first sergeant asked him if he was prior enlisted. When Marion, now a captain, said yes, the first sergeant said, “I thought so when I saw you salute a 2nd lieutenant.”

Marion was one of six chaplains serving on the base. His responsibilities included conducting services at the chapel, counseling airmen and their families, and visiting people at the hospital and other units on base. He also routinely visited the flight line and the alert stations late at night, talking to the aircrews waiting to see if they would get a call to fly a mission in the event of an attack from the Soviet Union. When they were on alert, the aircrews were isolated from their families with nothing to do but think about the possibility of being involved in a nuclear war. Marion’s late-night visits provided a welcome respite from their isolation, boredom, and fear.

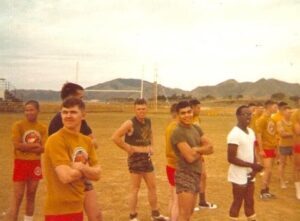

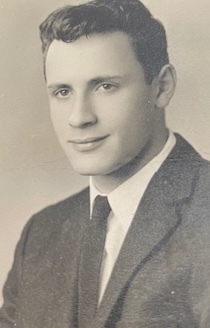

Chaplain Marion Reynolds at Grand Forks Air Force Base in 1968

Chaplain Marion Reynolds at Grand Forks Air Force Base in 1968Grand Forks’ winters were notoriously long and cold. During one of his conversations with an airman on alert, Marion asked what summers were like in Grand Forks. The airman replied, “I’m sorry, I can’t tell you. I slept in that day.” Despite living through two Grand Forks’ winters, Marion and his family had a wonderful time there. When it came time to transfer in the summer of 1970, Marion received orders to Kunsan Air Base, located about 110 miles south of Seoul, South Korea. Because the assignment would last only one year, the tour was unaccompanied. This meant Nancy and the girls would have to remain stateside. Although this was difficult for Marion, everyone assigned to Kunsan Air Base was in the same situation. Accordingly, Marion could relate to what they were experiencing. And, like everyone else at Kunsan, he also felt the constant stress of being so close to North Korea, which could invade its southern neighbor at any time without provocation or warning.

Marion served at the Kunsan Air Base chapel conducting services on Sundays and providing religious education to the base community. Since the chapel was at one end of the base and all the base offices were at the other end, the chaplains used a vehicle to meet with airmen in their workspaces. This worked well until an Inspector General (IG) team visited and needed vehicles, so the chapel had to give its up. To remedy the situation, the base commander let the chaplains go to the base’s junkyard and salvage an old van that had nothing in it but a driver’s seat and an open cargo space behind it. Marion and the other chaplains outfitted the van with two easy chairs. After collecting sandwiches and hot chocolate from the chow hall, they, together with the base security supervisor, drove it to the men standing watch at the guard posts around the base perimeter. At each post, the security supervisor relieved the sentry and his guard dog and stood their watch while the sentry sat in an easy chair enjoying a sandwich, hot chocolate, and friendly conversation. Once warmed in the van, both the sentry and his guard dog returned to their post.

The van proved an instant success until the IG departed and the chapel had to give it up. When the IG team heard about it after their departure, they recommended in their report that the chapel be given a new van, which it was. The only catch was the chapel had to share it with the commander of the 5th Air Force, who used the van to change uniforms in whenever he flew from his headquarters to Kunsan. Fortunately, the 5th Air Force commander only used the van once. The new van even had a sign on its sides, “Chaplain Mobile Office,” and a cross on the grill, both of which were removed when the 5th Air Force commander used the van. Working out of the Chaplain Mobile Office was one of the highlights of Marion’s tour.

Another highlight included the great relationships Marion forged with his fellow chaplains. This often played out in pranks, like the time Marion and a Catholic chaplain attached a Korean firecracker, which would detonate when strings at each end were pulled, to the toilet in their shared living facility. When the senior chaplain later raised the toilet seat, the firecracker exploded harmlessly but with a big boom. Later, when the Catholic chaplain went to take his shower in the same bathroom, he found the hot water knob missing and the bathroom window open, flooding the room with icy cold winter air. The pranks kept morale high and helped the men deal with the separation from their families.

The chaplains also helped others deal with being far from home. They always parked their Mobile Chaplain Office near the mail room after the mail plane arrived, knowing not a day would go by without someone receiving bad news. Marion and the other chaplains were there to listen and to console the recipient, hoping to make the hurt less painful.

Chaplain Marion Reynolds (right) climbing into an F-101B “Voodoo” for a ride in the jet fighter in 1970

Chaplain Marion Reynolds (right) climbing into an F-101B “Voodoo” for a ride in the jet fighter in 1970Marion’s tour at Kunsan Air Base ended in the summer of 1971. He transferred to Moody Air Force Base in Valdosta, Georgia, where Nancy and their two girls joined him. Marion was one of four chaplains serving at the chapel there. One of his duties—and for all chaplains worldwide wherever assigned—was to assist in making casualty notifications to deceased servicemembers’ families. One late, rainy night, Marion accompanied a unit commander to notify the elderly parents of an officer that their son’s plane had been shot down in Vietnam and that he had been killed. Although the commander conveyed the horrible news, Marion provided comfort and support, not only to the parents, but also to the commander on the way to and from the notification. Always gut-wrenching, casualty notifications such as this were an essential part of Marion’s duties throughout his career.

Marion spent three years at Moody before receiving orders to be the lone chaplain at Morón Air Base in southern Spain. The base, which had the third longest runway in Europe and served as an alternate space shuttle landing site, was inactive but in a caretaker status in case U.S. military dependents or civilians from other places Europe needed a safe haven to escape a natural or man-made disaster.

Marion and his chaplain’s assistant ministered to the roughly 260 people maintaining the base’s buildings and runways and to the sailors operating a Navy communications facility on Morón. Nancy and their two daughters were also there, as were the families of all the base employees. All went well until it came time for Marion and Nancy’s oldest daughter to leave the on-base grade school to go to middle school. The only available option was a boarding school many hours away in Zaragoza, which Marion and Nancy considered no option at all. Accordingly, Nancy started home schooling their daughter, and she was soon joined by other students studying in the chapel library. Although it worked out in the end, reaching the resolution was stressful.

In March 1976, when people in the United States were celebrating the bicentennial, Marion organized a bus trip from Morón to the Friary of La Rábida in Palos de la Frontera, Spain. Christopher Columbus stayed at the Friary during his efforts to convince King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella to finance his first expedition to the New World. The Friary had on display containers with soil and the flags from every country in the Americas. The U.S. flag, however, was stained and ragged, so after the trip, Marion contacted the U.S. consulate in Seville. The result was a second visit to the Friary, this time with a representative from the consulate, to present a new American flag for the display. Afterwards, Marion and the representative celebrated with a meal together with their Spanish hosts.

With Morón Air Base already in a caretaker status, it came as no surprise when the Air Force downgraded the manning at the base so that it no longer included a chaplain. As a result, Marion transferred in the summer of 1977 to Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, promoting to major enroute. Although the base’s main mission involved flight training for the A-10 “Warthog” attack aircraft, Marion worked primarily with the missile and spotter plane commands. He also visited the airmen manning the Titan II nuclear missile silos located on base because they worked twenty-four-hour shifts and were isolated underground behind massive blast doors. Marion’s talks with the airmen helped them deal with their isolation and their immense responsibility. Marion and his family loved living in Tucson and spent four years there.

In 1981, Marion reported to his next assignment as the base chaplain at Albrook Air Force Station, located in the Panama Canal Zone on the east side of the canal. As the base chaplain, he was responsible for all chapel operations, including all assigned personnel. He and his family enjoyed their time living in Panama’s tropical climate. Adding to the enjoyment, Marion promoted to lieutenant colonel while there.

After three years in Panama, Marion received orders to attend the prestigious Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. One of only two Air Force chaplains selected to attend, Marion participated in the course along with Air Force rising stars who would lead the service into the future. Working with them side-by-side for a year, Marion conveyed a realistic and positive view of how chaplains could help them accomplish their missions. Similarly, Marion learned about the other class members’ warfare areas and concerns, giving him a strategic view of his own responsibilities. The class also introduced Marion to civilian and military leaders at the national level during trips to Washington, D.C., where he visited the Pentagon, Supreme Court, and Congress. International class members with an entirely new set of experiences further broadened Marion’s perspective. In return, the class offered Marion the opportunity to minister to his classmates.

Marion graduated from the Air War College in the spring of 1985 and transferred to Norton Air Force Base in California to be part of the Air Force IG team of inspectors. His IG responsibilities took him to Air Force facilities around the world, where he helped evaluate and improve their religious programs by making recommendations based on regulatory requirements and his many years of personal experience. One of four chaplains on the IG team, Marion’s philosophy was to help the base religious programs solve problems and improve their effectiveness. Because those being inspected appreciated Marion’s attitude and help, he enjoyed his tour with the Air Force IG.

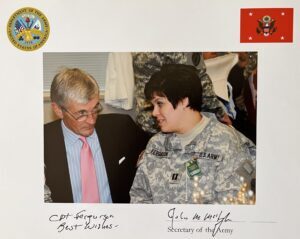

Chaplain Marion Reynolds (right) after Major General Richard E. Hawley (left) presented him with the Legion of Merit at his retirement ceremony. Nancy Reynolds is reviewing the award citation with the general.

Chaplain Marion Reynolds (right) after Major General Richard E. Hawley (left) presented him with the Legion of Merit at his retirement ceremony. Nancy Reynolds is reviewing the award citation with the general.In the summer of 1987, it came time to transfer again. This time Marion went to the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. He and Nancy, now empty-nesters, lived in a wonderful three-bedroom on-base house, fully immersing them in the academy experience. Now a full colonel, Marion was responsible for the Community Center Chapel, which provided religious support to everyone living or working at the academy except cadets. He still dealt with the cadets during their orientation program and when he and Nancy sponsored individual cadets to give them a substitute family away from home. He also conducted the Christmas Eve service at the Air Force Academy Chapel, which members of the local community were invited to attend.

Marion transferred to his final duty station, the 5th Air Force headquarters at Yokota Air Base in Japan, during the summer of 1989. His boss was the three-star general commanding all forward deployed Air Force units in Japan. Marion, in turn, was responsible for supporting all the chaplains assigned to Air Force bases in Japan. This required him to periodically travel to other Air Force installations to meet with the base chaplains and to ensure they had what they needed to get their jobs done. He also initiated quarterly meetings with civilian missionaries serving in the greater Tokyo area, recruiting and preparing them to assist with the response in the event the base ever suffered a mass casualty event.

While he was at Yokota, Marion required surgery on his nose. Doctors at the Naval Hospital in Yokosuka, Japan, performed the surgery. While he was recuperating, Marion met a Navy corpsman who told him his father had been an Air Force chaplain. Marion asked the sailor his name and he said it was King. As it turned out, Chaplain King had ministered to Marion when he was an enlisted recruit at basic training, influencing him to become a chaplain himself. Marion had also crossed paths with Chaplain King years before during a trip to Kadena Air Base in Okinawa. Meeting Chaplain King’s son was a full circle moment for Marion, connecting the beginning of his Air Force career with the end.

Another notable moment occurred when Marion and Nancy attended a Christmas party hosted by a command doing classified work like the program Marion was involved in when he was an enlisted airman. As part of the festivities, the unit held a drawing to present a five-foot stuffed teddy bear to the lucky winner. The unit’s commanding officer took advantage of Marion’s presence and announced, “To avoid any suspicion about the drawing process, we have asked Chaplain Reynolds to draw the winning name.” Marion did as instructed and, unbelievably, pulled Nancy’s name from the hat. For many years thereafter, the teddy bear lived with Marion and Nancy, guarding their spare bathroom.

Marion retired at Yokota Air Base in February 1992. The 5th Air Force Commander honored him with a formal parade and retirement ceremony. One of the officers making remarks at the ceremony was a chaplain who had been a B-52 navigator Marion visited in the alert shack at Grand Forks Air Force Base over twenty years before. In addition, the officer who served as the Commander of the Troops was the son of a master sergeant Marion served with at Kunsan Air Base. The events were a fitting salute to Marion’s distinguished twenty-eight-year career.

After retiring from the Air Force, Marion and Nancy returned to Arkansas to begin the next chapter of their lives. Two years later, Marion became the Chaplain Coordinator for the Arkansas Baptist State Convention. He was responsible for coordinating with the Convention’s 300 chaplains serving in active duty, reserve, and National Guard military units and throughout the state in such places as hospitals, prisons, fire departments, and police departments. He continued in the position until September 2012, when he began working weekends as a hospital chaplain in North Little Rock. He stayed in that position until it was eliminated and has been volunteering ever since in the hospital’s rehabilitation unit. The hospital badge he wears identifies him not only as a volunteer, but also as a retired military member. When veterans see that on his badge, it immediately breaks down barriers and allows Marion to better encourage them in their recovery.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Chaplain Marion Reynolds for his long and distinguished career in the Air Force. Often assigned to remote areas, he went out of his way to bring comfort and a touch of home to military members dealing with isolation and life’s many challenges. His service took him across the globe to three continents, ministering to others and helping them cope with their important military responsibilities. We thank him for all he has done, and for all he continues to do for those recovering from injury or illness, and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Marion’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chaplain, Colonel, Marion Reynolds, Chaplain Service, U.S. Air Force (Retired)

Chaplain, Colonel, Marion Reynolds, Chaplain Service, U.S. Air Force (Retired) The post Chaplain, Colonel, Marion Reynolds, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) – Faithfully Serving Those Who Serve first appeared on David E. Grogan.

October 16, 2024

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt, U.S. Army – Treating Soldiers and Detainees – A Combat Medic’s Story

Military members sign up to serve in whatever capacity their talents allow. Specialist Stacy Breithaupt knew early on she had an aptitude for healthcare, so it was only natural she became a combat medic. Soon she found herself treating soldiers and their families both in the United States and abroad. Then, in 2005, she deployed to Iraq working with detainees at the mammoth insurgent detention center at Camp Bucca. Less than one year later, it would be Stacy on the receiving end of medical care.

Stacy was born in September 1979 in Burton, Michigan, and grew up in typical Midwestern fashion. She was the second oldest of four siblings, all girls. She played sports for Bendle High School and enjoyed roller speed skating. She also earned money by babysitting, working as a cashier at Marco’s Pizza, and serving as a hostess at an Olive Garden restaurant. At that point, Stacy’s life stopped being typical because she had a plan.

Bored with high school during her senior year, Stacy sat for the GED exam in March 1997 and graduated that same month. With her high school degree in hand and influenced by the positive Army experience of her Aunt Teri, she marched to the nearest Army recruiting station. She enlisted in the Delayed Entry Program with an active duty start date of May 1. She was just seventeen years old.

When May 1 arrived and Stacy’s high school friends were sitting in their classes counting down the days until graduation, Stacy’s Army recruiter picked her up at home and dropped her off at the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS) in Troy, Michigan. After passing a final physical, taking the oath of enlistment, and spending the night in Troy, she flew to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to begin her Army career.

Stacy Breithaupt pointing to Specialist Christopher T. Monroe’s name on an Iraq War memorial

Stacy Breithaupt pointing to Specialist Christopher T. Monroe’s name on an Iraq War memorialBasic training at Fort Jackson brought no surprises. Stacy expected it to be a long and tiring process, and it lived up to her expectations. Still, she did well because she wanted to be there. She already knew how to shoot and was in great physical shape due to her high school sports and speed skating conditioning, so those aspects of her training posed no problems. Her only stumbling block was using topographical maps, a skill she eventually acquired after sufficient practice.

Stacy graduated from basic training just before the Fourth of July. She then began Advanced Individual Training (AIT) as a combat medic at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. There she learned the basic life-saving skills she needed to provide emergency medical care to wounded soldiers on the battlefield. Her job was keep the soldiers alive until they could be transported to medical facilities for more advanced treatment by doctors and nurses. She learned to give IVs, draw blood, manage medical records, administer medications, and triage injured soldiers. To help put what she learned into practice, she worked at the Troop Medical Clinic (TMC) at Fort Sam Houston.

Although Stacy learned quickly and loved every aspect of her training, it did have its drawbacks. Early on, the instructors identified her as having small veins and used her as a training aid anytime they wanted to demonstrate how to perform a difficult blood draw or IV insertion. The hot Texas summer also proved harsh for Stacy since she’d grown up in much cooler Michigan. So much so that three weeks into the course, she had to be hospitalized for three days due to heat exhaustion. For the rest of the training, her instructors repeatedly reminded her to stay hydrated so it wouldn’t happen again.

Stacy graduated second in her class from the combat medic course in October 1997, just one month after her eighteenth birthday. Not only did she qualify as a combat medic, but she also earned her Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) certification. Her performance demonstrated just how much she wanted to be a combat medic.

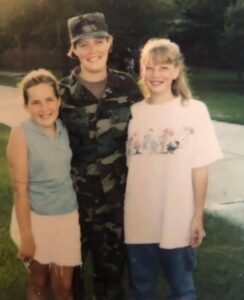

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt with her younger sisters

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt with her younger sistersAfter completing her training, Stacy reported to the 568th Ambulance Company at Camp Humphreys in South Korea. Located forty miles from Seoul and just sixty miles south of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea, the camp sits on one of the most potentially volatile flashpoints in the world. Adding to the political tension, Stacy initially felt stressed being so far from home and living in a completely different culture. Once she acclimated to her new environment, she settled in and had a great overseas experience.

The 568th Ambulance Company’s leadership played a significant role in Stacy’s successful transition. Not only did they put her to work using her newly acquired medical skills at the Camp Humphreys TMC, but they also gave her flight medical training and assigned her to fly with the “Dustoff” helicopters evacuating injured soldiers by air. The Dustoff work challenged Stacy and made her want to come into work every day, as did her promotion to private second class and eventually private first class. She also worked with Korean soldiers and learned to speak some Korean. She even visited the DMZ and took time to tour other sites in South Korea.

In October 1998, Stacy transferred to the 261st Area Support Medical Battalion (ASMB) at Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina. There she provided medical support for the 82nd Airborne Division’s parachute drop zones and the Air Assault School. She also worked at a local civilian hospital to maintain her EMT credentials. She stayed with the 261st ASMB until she transitioned to the Army Reserve in July 1999.

After leaving active duty, Stacy moved back to Michigan near her hometown. She immediately affiliated with the Army Reserve’s 431st Quartermaster Company in Lansing, just over sixty miles away. She drilled with the unit one weekend each month and an additional two weeks each year making sure the company’s soldiers were medically ready to deploy. This meant reviewing medical records to ensure soldiers had all their shots and were up to date on their dental checkups. She also followed-up with appropriate health resources for any soldiers with open medical needs. She did this until July 2003, when her original Army recruiter, now a reservist with the 785th Military Police Battalion, asked her to join his unit to help prepare it for an upcoming deployment to Iraq.

Stacy’s responsibilities at the 785th Military Police Battalion mirrored what she did for the quartermaster company. In addition, she taught the combat lifesaver course for the unit’s soldiers so they would be prepared to get a wounded comrade off the battlefield and to the medical treatment they needed. During these classes, Stacy taught the soldiers basic emergency tactical trauma techniques like administering IVs, applying pressure to wounds and bandaging them, and using tourniquets to stop bleeding.

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt (right) with two soldiers at Camp Bucca in Iraq

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt (right) with two soldiers at Camp Bucca in IraqAs the time for deployment drew closer, the 785th Military Police Battalion moved from its headquarters in Fraser, Michigan, to Fort McCoy in Minnesota to complete required readiness processing. At the individual soldier level, this involved things like signing powers of attorney, executing wills, and reviewing service records to ensure they were accurate and complete. After Fort McCoy, Stacy and her battalion moved to Fort Dix, New Jersey, to learn the specific skills necessary for their upcoming assignment as military police providing security for the Theater Internment Facility (TIF) at Camp Bucca in southern Iraq. The TIF held Iraqi insurgents detained during the Iraq War and was a dangerous place to work. In fact, while Stacy and the rest of the company were training at Fort Dix, the detainees at the camp took a soldier hostage and rioted. Eventually, U.S. forces brought the situation under control, but not before four detainees were killed and others injured.

The training at Fort Dix was intense. In addition to practicing riot control techniques, the company rehearsed providing security for convoys, safely handling and moving detainees, and managing and providing security for the camp’s Special Housing Unit (SHU). As the company’s medic, Stacy needed additional training to prepare her to provide medical care for detainees. Accordingly, the battalion sent her and the other medical staff for a three-week course at Camp Shelby in Mississippi, where she was the only woman participating in a class of men. That got the course off to an awkward start, as there were no separate accommodations for women and a guard had to be posted outside the restrooms anytime Stacy used them. After four days, the course administrators moved her to a hotel off base and life became easier for everyone. Stacy went on to recertify as an EMT by obtaining her EMT-Intermediate certification, and she earned her Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TC3) designation. After completing the course, she rejoined the battalion still training at Fort Dix.

In May 2005, the 785th Military Police Battalion departed Fort Dix and headed for Camp Bucca. Enroute, the company stopped at Camp Buehring in northwest Kuwait to acclimate to the harsh desert environment. Stacy, now a specialist, and the rest of the battalion finally arrived at Camp Bucca near Umm Qasr in southern Iraq in June 2005.

For the first three months of the deployment, Stacy worked at Camp Bucca’s TMC providing medical care for U.S. soldiers and civilian contractors working at the camp. After that initial period, she assisted the company’s medical officer providing medical care for the detainees in the TIF. This included providing basic emergency care to any detainees who might be injured as well as giving them their medications, conducting blood draws, and administering IVs. She worked across three open-air detainee compounds housing over one hundred detainees each, making tracking and sorting their medications a challenge. Because the detainees were unpredictable and could be dangerous, Stacy had to be alert and ready for anything whenever she worked within the facility.

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt on convoy duty in Iraq

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt on convoy duty in IraqIn addition to her responsibilities within the TIF, Stacy participated in convoys transporting detainees between Camp Bucca and the detention facility at Abu Ghraib, located approximately 350 miles away in the vicinity of Baghdad. During these convoys, she rode in an ambulance and had to be prepared to render any medical assistance required, including administering medications the detainees needed to take during the transport. The convoys were always at risk of attack, either by insurgent forces or by improvised explosive devices (IEDs) hidden along the route. To underline the danger, Apache attack helicopters flew above the convoys to ward off would-be attackers. Still, the convoys were vulnerable. In September, two servicemembers from Camp Bucca were killed when their vehicle struck an IED. One month later, on October 25, Stacy lost a good friend, Specialist Christopher T. Monroe, when he was killed during a convoy.

The danger continued even after the convoys reached their destinations. Once, after arriving at Abu Ghraib, Stacy was walking in the camp when a large explosion detonated near the front gate. The force was powerful enough to knock bricks off the wall near where Stacy stood. She also had to deal with a riot at Camp Bucca, where her parked vehicle was destroyed and a detainee escaped. Another time, three detainees managed to dig their way out of the compound. Although they were recaptured, the specter of detainees running loose around the camp kept Stacy on edge.

Stacy also participated in recovery operations when IEDs disabled or destroyed convoy vehicles. When this occurred, wreckers were dispatched to recover the damaged vehicles. If anyone was injured or killed in the attack, Stacy accompanied the recovery team in an ambulance to help treat the injured parties and bring them or any deceased persons back to the camp.

In November 2005, Stacy started feeling run down. She initially attributed her condition to working in the TIF eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, while wearing all the required protective gear in the oppressive Iraqi heat. Eventually, the company sent her to Camp Arifjan in Kuwait, where she was diagnosed with a bacterial infection in her stomach. While still foggy from the anesthetics used during the exam, she was returned to Camp Bucca with antibiotics and directed to go back to work because the battalion needed her.

The antibiotics did not work, and Stacy’s stomach condition worsened to the point where, by the beginning of January 2006, she could no longer eat. Major Grundy, the battalion medical officer she worked for, tried to help, but he didn’t have the necessary testing equipment and therefore had no idea what was causing her symptoms. Still, her command expected her to work although she struggled to make it through each day. When Stacy could take it no more, she told her commanding officer she could no longer work and that if he didn’t send her for treatment, she would be leaving Iraq in a body bag. The battalion finally medevacked her to the Army hospital in Langstuhl, Germany.

When Stacy arrived at the Army hospital, she weighed only eighty-nine pounds. The doctors spent the next week ensuring she was stable enough to transport back to the United States. At the end of January, she was medevacked on a C-130 to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. When she woke up, the command leadership team of the 18th Military Police Brigade was there by her bedside. They wanted to know her perspective on how her condition had been allowed to get to the point it had.

Although Stacy appreciated their willingness to hear her story, she was angry. She felt as though she had taken excellent care of the 785th Military Police Battalion’s soldiers, but when it came to her own health, the command had let her down. Now she just wanted to recuperate and get on with her life as a civilian. The healthcare team at Walter Reed helped make that possible by correctly diagnosing the cause of her condition as an intestinal parasite she had somehow acquired in Iraq. The good news was now that the problem had been identified, it could be treated. That bad news was the condition had been allowed to fester for so long, Stacy sustained permanent organ damage. She spent the next three months at Walter Reed and Fort Dix getting back on her feet. Eventually, she would undergo thirteen surgeries to repair the damage caused by the parasite.

Stacy did not wait for the surgeries before transitioning out of the Army. In fact, she was discharged from Walter Reed on April 1, 2006, and honorably discharged from the Army Reserve on the same day. She then returned to Michigan to continue her treatment through the Veterans Administration (VA).

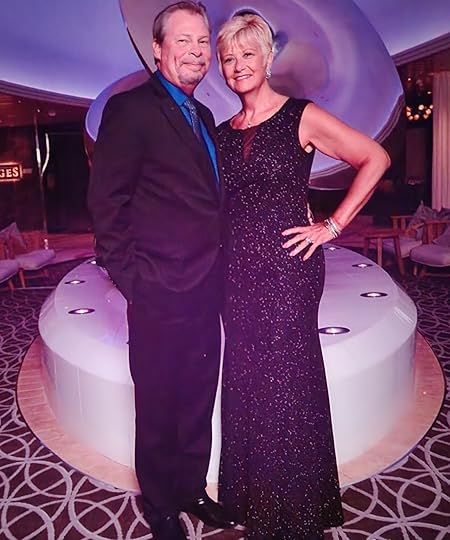

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt (left) with her husband, Sergeant David Breithaupt (in uniform), and their children

Specialist Stacy Breithaupt (left) with her husband, Sergeant David Breithaupt (in uniform), and their childrenAlthough Stacy no longer wore an Army uniform, her association with the Army continued through her husband, Sergeant David Breithaupt. He took active duty orders in June 2007, and Stacy moved with him to Fort Stewart, Georgia. In July 2008—the first time Stacy was healthy enough to work again—she accepted a civilian position as the 92nd Engineer Battalion Family Readiness Support Assistant helping Army family members understand the support programs available to them. She would take similar civilian positions with the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Infantry Regiment at Fort Stewart, the 321st Infantry Regiment at the Army Reserve Center in Winterville, North Carolina, and the 94th Training Division at Fort Lee, Virginia. Stacy finally retired from the Civil Service in 2021. At the time, she was working with the Greenville North Carolina VA. During her Civil Service employment she also earned her bachelor’s degree in business administration.

Stacy and David now live in Michigan. They raised four children together: Caleb, Melissa (who sadly passed away in November 2019), Maegen, and Anthony. Staff Sergeant Anthony Breithaupt followed in his parents’ footsteps and is a Ranger scout in the 101st Airborne Division. Stacy and David enjoy traveling and spending time with family. Wanting to continue her lifelong mission of supporting the military, veterans, and their families, Stacy is an active member of Blue Star Mothers of America.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Specialist Stacy Breithaupt for her dedicated years of service to the Army. At great personal cost to herself, she rendered medical care to soldiers and civilians in need both in peacetime and in war. She deployed to Iraq at a crucial time in the Iraq War, rendering medical assistance to friend and foe alike. She then defeated a debilitating illness, only to continue serving Army families in her civilian capacity. We thank her for all her sacrifices and wish her fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Stacy’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

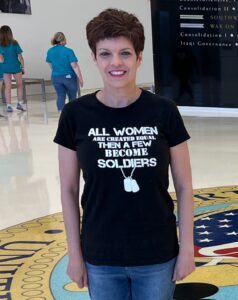

Stacy Breithaupt (center) with other members of the Blue Star Mothers of Michigan

Stacy Breithaupt (center) with other members of the Blue Star Mothers of Michigan The post Specialist Stacy Breithaupt, U.S. Army – Treating Soldiers and Detainees – A Combat Medic’s Story first appeared on David E. Grogan.

September 12, 2024

AW1 Thomas W. Hayes, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired) – Three Rescues in Two Days

Navy sailors train over and over so they are prepared to do their jobs under any circumstances. Be it peacetime or war, they must be ready to accomplish their missions even at the risk of their own lives. Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator 1st Class Thomas W. Hayes, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired), trained as a search and rescue swimmer and deployed aboard aircraft carriers in case he was needed to save downed aircrew from the ocean’s icy waters. Because of his efforts, three aviators lived to fly again another day. This is his story.

Tom was born in November 1953 in Highland Park, Michigan. His father settled there after his hitch in the Air Force during the Korean War, although the family eventually put down permanent roots in East Detroit. Tom and his two younger sisters attended East Detroit High School, a huge school enrolling 3600 students in the top three grades. Tom found his niche in the choir, which he sang with all three years and served as the choir president during his senior year. He also worked at Chatham’s grocery store to keep some spending money in his pockets, but the real headline from his time at high school was he started dating his future wife, Regina Marie Laesch, during his senior year.

Tom graduated from East Detroit High School during the spring of 1972 and began working full time at Chatham’s grocery store as part of the night crew stocking shelves. His mom wanted him to go to college, but Tom knew he wasn’t ready. What he was ready for was getting married, which he and Regina did in 1975. By the summer of 1976, Tom knew he needed more than a career at the grocery store. He discussed his thoughts with Regina and asked her if she would be okay with him joining the military. When she gave him the green light, he headed for the nearest Armed Forces Recruiting Station to see what the military had to offer.

The recruiting station had recruiters from all four services, so Tom decided to talk to the Marines first. He asked the sharp-looking Marine gunnery sergeant (“gunny”) what the Marines could do for him. The gunny stood up and told him he would get to wear the Marine uniform. Tom was looking for more than that, so he made his way to the Navy. Admittedly, the Navy had a leg up on the other services before Tom even walked into the recruiting station. That’s because when Tom was a boy, his family visited a Navy ship tied up along the Detroit River. When the ship got underway for family day, Tom went along because one of the ship’s petty officers was a family friend and they let Tom steer the ship. As if that experience wasn’t enough, the Navy recruiter was a high school classmate of Tom’s. He had joined the Navy right after graduation and was now back in Detroit on recruiting duty.

Tom Hayes at his radar station on board a P-3 Orion while assigned to VP-93

Tom Hayes at his radar station on board a P-3 Orion while assigned to VP-93The recruiter asked Tom what he wanted to do if he joined and Tom said he would love to fly. The recruiter told him the Navy had just the job for him – an Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator or “AW”. He told Tom if he became an AW, he could serve on the big four-engine anti-submarine aircraft known as the P-3 “Orion” and he would never have to serve on a ship. That was music to Tom’s ears because avoiding long periods away from home while deployed on a ship would work best for him and Regina. He told the recruiter if he could make him an AW, he was in.

To seal the deal, Tom passed the initial physical exam and took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), a prerequisite to enlisting. After processing the results, the recruiter informed Tom he could not get him the AW job they had discussed, but he could make him an Operations Specialist (OS). Knowing that meant extended time at sea on ships, Tom told the recruiter since he could not make Tom an AW, he was no longer interested in enlisting. The recruiter told Tom to give him fifteen minutes and he disappeared. He returned at the end of the time period and told Tom he’d gotten him the AW job after all. That was all Tom needed to hear and he enlisted in the Delayed Entry Program with an active duty report date of September 22, 1976.

When September 22 arrived, Tom and approximately thirty other new recruits reported as ordered. They were escorted to the train station for the trip to boot camp. As they waited for the train, a Navy petty officer handed Tom a folder with everyone’s name in it. He told Tom since he was the oldest recruit, he was in charge and responsible for making sure everyone arrived safely at Naval Station Great Lakes for boot camp. His Navy career had officially begun.

Tom succeeded at his first tasking as everyone was accounted for when the train arrived at Union Station in Chicago late in the evening. Then they were all herded onto a bus for the final leg of the journey to Naval Station Great Lakes, located about an hour north of Chicago. They arrived early on the morning on September 23 and “hell broke out right away” as the transition from civilian to sailor began.

Tom felt prepared for the ordeal because his father had given him an idea of what to expect upon arrival. Above all else, he told Tom never to volunteer for anything. This rang true when the company commander asked for volunteers to drive his Cadillac. Hands shot up and the company commander selected his volunteers. The chosen few were all smiles until they learned the company commander’s Cadillac was a bucket of water on wheels with a mop for swabbing floors.

Although Tom dodged that bullet, he could not avoid being designated as the Recruit Chief Petty Officer, or “RPOC”, after the recruit in the position before him lost the job for being a jerk. As the RPOC, Tom called the cadence when the company marched around the base between training events and to chow. He also served as the Recruit Division Commander’s primary assistant, responsible for keeping everyone in the company in line. As for Tom’s predecessor, he got what he deserved for being a jerk. As the company marched to the chow hall one afternoon, the jerk and his friend were both targeted by a seagull. With pinpoint accuracy, the seagull dropped a bomb that splattered on both recruits at the same time. Tom describes the event as karma in action.

After graduating from boot camp two weeks before Christmas in 1976, Tom reported to Naval Air Station Memphis for AW “A” school. There he learned the basics of being an Aviation Anti-Submarine Warfare Operator. He also had to pass the Class II swim test. Tom did well in the classroom part of the training, but he especially excelled at swimming because he’d been a swimmer all his life and was already a certified lifeguard and diver. A Navy SEAL chief petty officer administered the swim test and, after he saw Tom swim, took him aside and said, “Son, you’re going to the fleet. They really need swimmers.”

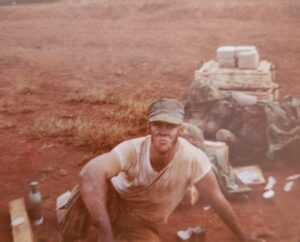

Tom Hayes wearing a wetsuit while flying plane guard on an SH-3 Sea King helicopter

Tom Hayes wearing a wetsuit while flying plane guard on an SH-3 Sea King helicopterThe SEAL chief’s evaluation completely changed Tom’s trajectory. Instead of heading to P-3 ASW patrol aircraft operating only from Navy airfields ashore, now he would be an aircrewman on the SH-3 Sea King helicopter getting underway on ships for long periods away from home. It also meant he would train to be a rescue swimmer, ready to jump from helicopters into the ocean to pluck downed pilots from the water before they drowned.

Tom’s training as an SH-3 helicopter aircrewman began immediately after AW “A” school. First, he spent five weeks attending Search and Rescue (SAR) swimmer school in Jacksonville, Florida. There he learned basic first aid, practiced treading water for long periods, and built his endurance through constant physical training. He also learned skills like getting someone out of a parachute while in the water and rescuing a combative swimmer. For his final exam, he had to jump into a disaster situation where five or six people needed to be rescued. He had to assess each person’s situation, prioritize their rescue, and then use the appropriate technique to successfully rescue each person. The final test kept him working in the water for a full forty-five minutes, but when he emerged, he was a qualified SAR swimmer.

Tom next reported to Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) school at Naval Air Station Brunswick, Maine. He spent a week and a half there learning what to do in the event he was ever captured by enemy forces. Although Tom was an experienced outdoorsman because he had gone camping with his father growing up, the entire experience proved a challenge. He was glad when it was over.

After SERE school, Tom reported to HS-1, the SH-3 Sea King helicopter Readiness Air Group (RAG), onboard Naval Air Station Jacksonville. All newly arriving SH-3 enlisted aircrew and officer pilots on the East Coast received their final training there before reporting to a fleet SH-3 helicopter squadron. At HS-1, Tom got his first taste of flying as an aircrewman in a helicopter, accumulating twenty-five hours of flying time. He obtained additional training hours in an SH-3 simulator, but by the time it came time to transfer to an operational squadron in the fleet, he had yet to jump out of a helicopter to conduct a practice rescue.

The reason Tom did not get to conduct a practice jump was because the fleet really needed rescue swimmers. To meet the demand, HS-1 condensed Tom’s training timeline and sent him off to his first permanent duty assignment at HS-15, a fleet SH-3 squadron also located onboard Naval Air Station Jacksonville. This worked out well because he had previously moved Regina to Jacksonville while he was in SAR school. They purchased a mobile home near the base and prepared to welcome their first child in early 1978. Before that, though, the HS-15 “Red Lions” had plans for Tom that would take him far from home.

Those plans involved the squadron and all its personnel, including Tom, deploying on the aircraft carrier USS America (CV-66) on September 29, 1977. Once the ship got underway on the cruise, Tom took his turn working in the ship’s main galley “mess cranking”, doing duties necessary to help feed the America’s 5,000 crewmembers, but the usual six-week assignment for new sailors was reduced to two weeks because the ship needed his skills as a SAR swimmer more than it needed him to wash dishes.

The America put Tom’s skills to the test one night in November 1977 when the ship was conducting flight operations in the Mediterranean Sea. While Tom was flying on an SH-3 conducting a night ASW mission in the vicinity of the aircraft carrier, an F-14 “Tomcat” jet fighter, made famous in the 1986 film Top Gun starring Tom Cruise, tried to land on the ship’s flight deck. The plane’s tailhook caught the arresting wire but the wire failed. Both the pilot and the radar intercept officer (RIO) ejected from the plane before it went over the side, with both men landing in the calm but pitch-black water.

Immediately, the ship put out the call “two men in the water.” Without waiting for direction, Tom took off his helmet and put on his wet suit as the helicopter’s pilot maneuvered the SH-3 to the area where the two men might be. Soon they saw a pencil flair launched from one of the downed crewmembers and the SH-3’s pilot positioned the helicopter for the rescue.