David E. Grogan's Blog, page 4

February 15, 2023

LCDR Joe Dwigans, U.S. Navy – From an Iowa Dairy Farm to Flying Navy Helldivers

The naval aviator training pipeline is grueling. It takes months of study to learn the basics of flying. It takes strength of body and mind to withstand the physical and mental strains of landing a plane on the pitching deck of an aircraft carrier at sea. Most of all, it takes courage, to launch from a ship in the middle of the ocean in search of a target with the hope of accomplishing the mission and returning home safely. Few have what it takes to even try to meet naval aviation’s high standards and even fewer succeed. At the height of World War II, with the naval war against Japan raging in the Pacific, Lieutenant Commander Joe Dwigans, U.S. Navy (Retired), raised his hand and said I can do it. This is his story.

Joe was born in his parents’ farmhouse in Stuart, Iowa, in 1921, the oldest of three children. His father had been drafted into the Army near the end of World War I and was on his way to Europe in a troop ship when the war ended. The ship turned around and Joe’s father made his way back to Iowa where he married Joe’s mother and started a family. In 1927, he accepted a job at the Veterans Administration (VA) Hospital in Knoxville, Iowa, and moved Joe and the rest of the family there. They lived on a farm and after a while, a friend asked Joe’s father to keep a dairy cow for him so the friend’s family would have a supply of fresh milk. He took the opportunity and ran with it, eventually growing the herd to thirty dairy cows. The family’s dairy farm supplied fresh milk to lots of families in the Knoxville area.

The dairy farm kept the entire family busy, even during the lean years of the Great Depression. In addition to helping take care of the cows, Joe earned twenty-five cents a week from a paper route, which he kept all through high school. For that meager sum, Joe could attend a cowboy show at the movies on Saturday, pay for popcorn and a Snickers bar at the show, and still put five cents away so he could say he wasn’t broke.

Even more profitable was a rabbit business Joe and his dad ran in conjunction with Joe’s paper route. Joe’s father raised the rabbits on the farm and had them stacked in cages six high. As the rabbits got older, their cages worked their way up from ground level until they reached the top of the stack, indicating the rabbits were ready to sell. On his paper route during the week, Joe took orders from his customers for the rabbits. On Friday night, he delivered rabbit filets wrapped in wax paper to his waiting customers. Joe also hunted squirrels for his mother. She would tell him how many she needed, and Joe and his dog would bring them back in time for dinner.

Another aspect of Joe’s paper route had longer-term consequences. The newspaper operated an autogyro – a fixed wing propeller-driven plane with an overhead rotor like a helicopter – which it used to get around the state to cover stories. When the autogyro was in Knoxville, the newspaper boys went to see it. On one such occasion, the pilot offered Joe a ride. He took it and from that moment on, he set his eyes on flying.

Joe Dwigans sitting in the cockpit of a Commemorative Air Force SB2C Helldiver

Joe Dwigans sitting in the cockpit of a Commemorative Air Force SB2C HelldiverBesides his paper route and helping with the family dairy farm, Joe attended school, eventually going to Knoxville High School. Although he was in excellent shape from working on the farm, he was too small to play sports. Still, he wanted to letter, so he convinced the football coach to let him be the team manager. Although his title sounded fancy, what it really meant was he had to do all the dirty work for the team. And, as if that wasn’t enough, he worked as a clerk at J.C. Penney’s Department Store in Knoxville.

Joe graduated from Knoxville High School in May 1939 and enrolled at the University of Iowa in Iowa City in the fall. He took aptitude tests to see what he should study, but none came back with clear guidance, so he registered for general classes. To pay for his room and board, he worked at the university hospital, busing food to the polio wards. To earn spending money, he asked his former boss at the J.C. Penney store in Knoxville for a recommendation so he could apply for a job at the J.C. Penney store in Iowa City. The recommendation worked because when he went for an interview, the Iowa City store manager simply asked him when he could start. Thereafter, he worked at the Iowa City store whenever he had free time.

In September 1939, war broke out in Europe with the Nazi invasion of Poland. When Germany invaded France in May 1940, Joe’s father saw the writing on the wall. He told Joe to come home after finishing his freshman year to work on the dairy farm until he was drafted. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into the war in December 1941, but it wasn’t until November 1942 that Joe finally received his draft notice in the mail.

In December, Joe reported as directed to the community hall in Knoxville, together with the other local men who had received draft notices. Joe stood in line until they called his name. At the first desk, they asked him whether he wanted to go Army or Navy. Having spent far too much time toiling in the mud and dirt on the dairy farm, he chose Navy. He then walked to the Navy desk, where they offered him various service options. Recalling his ride on the newspaper’s autogyro, Joe said he would like to give flying a try. Thus began Joe’s journey to becoming a naval aviator.

Joe’s first stop was the Naval Flight Preparatory School at Cornell College in Mt. Vernon, Iowa, a small town about 125 miles northeast of Knoxville. The Navy directed him to report to the school in the spring of 1943, where he joined other officer candidates hoping to become naval aviators. The new arrivals lived in one of the college’s dorms and ate their meals together at Bowman Hall. The training, which lasted about three months, indoctrinated the men into the Navy and placed a heavy emphasis on physical fitness. The training was rigorous and designed to begin weeding out those who could not deal with the physical and mental stress associated with being a pilot in combat. Any candidates not meeting the requirements were dropped from the program and sent to boot camp to become enlisted sailors.

In addition to the physical training, Joe and the other candidates attended classes to learn the basics about being an officer and did lots of drills and marching. While Joe was in excellent physical shape, he found himself competing against many college athletes who wanted to be pilots, too. He roomed with three other men in a dormitory room, one of whom had attended a military school before being drafted. He drilled Joe and the other two roommates until they became experts. During a competition that pitted Joe and his roommates against teams from the other four-man rooms, they took first place. The recognition was fleeting, as the next day they were back to their normal routine of classroom training, drills, and physical fitness.

After successfully completing the Naval Flight Preparatory School at Cornell College, Joe and his fellow officer candidates transferred to a small college near Safford, Arizona, for initial flight training. They learned to fly in civilian aircraft like the Piper Cub, often flying twice each day. The training assessed the candidates’ aptitude for flying and, like the Naval Flight Preparatory School before, weeded out those not suited for the cockpit. The big cut occurred when it came time to solo, with the candidates flying without their instructors for the first time. Joe enjoyed flying and did well, allowing him to advance.

Joe next reported to Pre-Flight School at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, California, a small town in the San Francisco Bay area. This training emphasized physical fitness and teamwork. To develop these attributes, Joe and the other men participated in team sports, primarily football. The Navy chose football because it was a physical sport with lots of contact, helping build in all the candidates the toughness they needed to meet and defeat their enemies in combat. Again, Joe’s smaller build proved a disadvantage, particularly on the gridiron. Fortunately, the San Francisco Bay area fog proved an unwitting ally. During one morning football game, a dense fog rolled in over the field. The fog was so thick, the players could hardly see each other even though they were standing right next to one another. When Joe took his position on the line, he saw he stood opposite Bruce Smith, an All-American football player from the University of Minnesota. Knowing he was about to be crushed, Joe dropped to the ground as soon as the center snapped the ball. No one saw him because of the fog, and he lived to play another day.

The Pre-Flight Training swimming requirements proved another challenge for Joe. Coming from central Iowa, he never learned to swim. He was not alone, because about thirty percent of his fellow officer candidates couldn’t swim either. To avoid being washed out of the program, they had to learn to swim and survive in the water. As an added incentive, if they did not pass their swim requirements for the week, they could not go on weekend liberty in San Francisco. This forced Joe to stay on campus on more than one weekend doing remedial swimming until he could satisfy the requirements.

Although the swimming requirements kept Joe from going out on the town, he found another way to have fun. By coincidence, an old girlfriend of his from Knoxville High School had moved to San Francisco, so he gave her a call. He told her although he could not go off campus, she could visit him. And, if she brought a carload of girls for his friends, that would be even better. She obliged, and she and her friends came to St. Mary’s for dances with Joe and the other candidates unable to go on liberty. As a result, both Joe and his former girlfriend became very popular.

Another way to get off campus was the Glee Club, which periodically performed around the local area. Joe decided to give it a try and auditioned for a spot. The director allowed him to join provided he promise not to sing a word out loud. Joe readily agreed and got the opportunity to go with the club on one of its performances. The best part was, a family in Oakland hosted him for a home-cooked meal and he had an amazing view of San Francisco from their house.

When Joe was able to go on weekend liberty with his buddies, they usually had little money to spend and could not afford to pay for a hotel room. The Hotel Leamington in Oakland, California, came to the rescue by opening its second floor to the officer candidates at no cost. The downside was they didn’t get rooms – they had to sleep in their uniforms wherever they could find an open space. That was all they needed, and the Hotel Leamington became their base of operations whenever they went in town.

Although the pre-flight training at St. Mary’s focused on physical fitness and team building, there was also an important classroom segment. Joe and the other candidates learned the basics of naval aviation, seamanship, communications, and aircraft and ship recognition. At the conclusion of the program, they were finally ready to learn to fly military aircraft.

After Pre-Flight School, Joe transferred to Naval Air Station Livermore, California, for Intermediate Training. This fourteen-week course began at NAS Livermore and consisted of both ground school and flight training. Joe learned the basics of flying in the two-seat Stearman Model 75 biplane, which he and the other candidates dubbed the “yellow peril” because of its bright yellow paint job and the inexperience of the students flying it.

Joe Dwigans standing next to an open cockpit Ryan STA trainer

Joe Dwigans standing next to an open cockpit Ryan STA trainerOnce he’d mastered the Stearman, Joe moved on to the next phase of Intermediate Training at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. This phase involved more advanced training in the North American SNJ trainer, known as the “Texan” by Army-Air Corps pilot trainees. Joe spent many hours flying the SNJ around south Texas, including over the vast King’s Ranch. He practiced take-offs and landings at outlying fields around Naval Air Station Corpus Christi and learned to fly with instruments rather than just visual flight rules. This phase of the training had a thirty-percent attrition rate, as it was the final cut before the candidates earned their wings. For Joe’s final check ride, he was dismayed to see his evaluator was “Down-Check Charlie”, who was notorious for failing pilots on their final rides. Although Joe was sure he flew an acceptable ride, he became another of Down-Check Charlie’s victims and didn’t pass.

Disappointed with the result, Joe spoke to one of his instructor advisors. The instructor asked him what happened, and Joe said he thought he had done okay. While they were talking, the instructor noticed Joe wearing a Masonic ring and asked him about it. Joe said he had recently been inducted. After the conversation, Joe got a second check ride with another instructor and passed with flying colors.

Joe and his fellow aviation candidates finally earned their pilot’s wings and were commissioned ensigns (O-1) in the U.S. Naval Reserve upon completion of their fourteen-week Intermediate Training. When Joe and the other new ensigns returned to their barracks after the commissioning ceremony, they found a Navy Chief (E-7) waiting for them with a can of polish and a rag for each of them. He told them to go to their rooms and polish the doorknobs until they shined enough to pass inspection. It was a not-so-subtle reminder to keep the new naval aviators from becoming too full of themselves.

Joe Dwigans in uniform displaying his naval aviator’s wings

Joe Dwigans in uniform displaying his naval aviator’s wingsAfter spending the better part of the last year together, the new officers went their separate ways. Their next task was to learn to fly the Navy’s combat fighters, dive bombers, and torpedo planes in preparation for battle against the Japanese fleet in the Pacific war. When Joe and his friends were asked what type of aircraft they wanted to fly, their first choice was the scout and spotter planes launched from battleships to help pinpoint targets for the ships’ big guns. They thought being one of only two or three pilots on the battleship, they would be a big deal. No one received that assignment. Instead, Joe was designated to fly the Curtiss SB2C “Helldiver”, the next generation dive bomber after the Douglas SBD “Dauntless”, made famous during the Battle of Midway by sinking four Japanese aircraft carriers.

Joe transferred to Naval Air Station Jacksonville on the coast of northeast Florida to learn to fly the Helldiver. Since he would eventually take off and land his plane from aircraft carriers at sea, he had to learn to navigate over open ocean with no reference points to help him get his bearings. This meant being able to look at the wave tops to estimate windspeed and direction so he could take them into account when plotting his course on the plotting board in the cockpit. He also had to learn to fly a triangular course that would take him to his target and bring him back to his starting point where he could land safely. To make the calculations more difficult, if his starting point was an aircraft carrier and the destination was enemy ships, both would be moving, so a course had to be plotted to where he thought the ships would be in the future, not where they were at the start of the mission. If Joe made a mistake, the consequences could prove deadly, because arriving at the wrong place could leave him with little fuel and nowhere to land. As one pilot Joe knew said, “I got lost once and made damn sure I never did again.”

On one occasion, Joe flew his Helldiver out over the ocean with a foreign pilot flying another plane. They flew into a bank of fog so dense Joe could not see the other pilot’s aircraft. He was also unable to contact the pilot by radio. Joe completed the training flight and returned to the airfield, only to find the foreign pilot waiting for him. He had decided to return to base rather than fight the fog. The flight proved the importance of being able to fly on instruments, rather than relying on only what Joe could see. Without his instruments telling him where he was, he could have become disoriented and flown his plane into the sea.

On another occasion, Joe and his fellow pilots went to the officers’ mess to get some lunch before their afternoon flight. Joe didn’t like the looks of the chicken concoction the cooks had put together, so he passed on the meal. Once all the planes got into the air and started forming up, the pilots began vomiting in their cockpits and scrambled to land as they became deathly ill from food poisoning. When Joe landed and saw the condition of the other pilots and their planes, he was glad he had decided to fly hungry.

Joe was also given the opportunity to fly the SBD Dauntless dive bomber, some of which had been brought back to the United States after the Battle of Midway. The pilots were admonished not to dive the planes because they were war weary. Joe volunteered to give the Dauntless a try, and as soon as he reached altitude, he checked the dive flaps and nosed over into a dive – just what he had been told not to do. When he reached what he thought was an appropriate altitude, he started to pull out of his dive. What he didn’t know, though, was that the Dauntless had a “mush” when pulling out of a dive and it used up most of the altitude he had left. When he finally leveled off, he found himself low to the ground and with the mesquite trees passing very close by. It was a lesson he would never forget.

To teach the Helldiver pilots to land on the Navy’s fleet aircraft carriers, which had flight decks less than 850 feet long, the pilots practiced take offs and landings on runways painted with markers simulating the available space on a carrier’s flight deck. Once Joe and the other pilots became comfortable making short take offs and landings, they progressed to taking off and landing on the USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60), an escort carrier with an even shorter flight deck operating off the coast of Florida. To successfully land on the Guadalcanal, Joe had to approach the stern of the ship flying low and slow and then catch the plane’s tailhook on one of three arresting wires crossing the flight deck. Joe’s first landing was particularly unnerving, because when the Landing Signal Officer at the stern of the ship signaled him with his paddles to cut his engine’s power to land, he could no longer see the ship below him. On a leap of faith, he cut power as directed. When his Helldiver caught the arresting wire and it jolted to a safe stop, he knew what to expect going forward. After completing six carrier landings, Joe was designated carrier qualified.

Landing on aircraft carriers wasn’t the only skill Joe needed. To accomplish his mission, he also had to be able to put his plane into a steep dive and drop up to 2,000 pounds of bombs onto an enemy ship zigzagging below at high speed and firing anti-aircraft guns at his plane to destroy it. One of the places Joe practiced dive bombing was on target ships in Lake Michigan. To get there, Joe’s squadron flew their planes from Jacksonville to Naval Air Station Gross Ile, just outside of Detroit. From there, they navigated across the state of Michigan to attack targets on the lake.

During one such practice bombing, Joe’s squadron spotted a ship towing a yellow target vessel. They attacked it with dummy bombs and scored several direct hits, sinking the target. When they returned to the airfield, they were summoned to the tower and told the vessel they sank wasn’t a target – it was a pleasure craft under construction being towed through the target area. Aside from getting chewed out, no one got in trouble because the vessel was not supposed to be in the restricted zone in the first place.

Joe Dwigans standing in front of a Commemorative Air Force SB2C Helldiver

Joe Dwigans standing in front of a Commemorative Air Force SB2C HelldiverOnce their training was complete, Joe’s bombing squadron, VB-75, became operational. It was scheduled to deploy to the Pacific aboard the soon-to-be commissioned Midway-class fleet aircraft carrier USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CV-42); however, World War II ended with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945. As a result, Joe and his squadron never flew aboard the carrier or deployed.

Although the war was over, Joe’s flying days were not. His squadron participated in several victory parades, including one over Washington, D.C., where the planes flew in formation down Pennsylvania Avenue at an altitude of just 1500 feet. On another flight out of New York, Joe asked his gunner if he wanted to see anything. His gunner, an enlisted sailor from Tennessee, said it would be nice if they could see the Statue of Liberty. Joe did just that, circling the Statue of Liberty so close it seemed he could reach out and touch it.

When the parades stopped, it was time for Joe to go home. Because he’d been in the Navy since early 1943, he had sufficient demobilization points to be released before the end of 1945. To make his way back to Knoxville, he went in with a pilot friend from Iowa who bought a used car. Together, they made the trip from Jacksonville, Florida, to central Iowa, only to have the car break down an hour outside of town. They were so anxious to get home, they left all their belongings in the car and hitchhiked the rest of the way. They came back the next day and towed the car the remainder of the way, with Joe’s buddy driving the lead car and Joe steering the broken-down vehicle.

Once home, Joe transitioned to civilian life. While he was gone, his parents had sold the family dairy business and purchased an ice cream store in town. Joe cashed in his war bonds and outfitted a freezer truck and made ice cream deliveries to all the surrounding towns. He expanded the ice cream store’s customer base by providing an ice cream freezer free of charge to any store that stocked his family’s ice cream. He expanded even further by making the same deal to schools providing their students with lunches subsidized by the federal government.

The biggest change in Joe’s personal life came in 1948 when he married Betty Rae Grewell. Together, they decided it was time for Joe to finish college. First, Joe took Betty to the University of Iowa in Iowa City, but she was not impressed by the Quonset hut quarters and oil burning stoves. At the suggestion of a friend, they visited the University of Oklahoma in Norman, Oklahoma, and were instantly sold. Using his GI Bill benefits, Joe earned his bachelor’s degree in accounting and stayed an extra year to earn his master’s degree, as well.

Although the GI Bill made his degrees possible, it did not cover all the expenses of his new family. Some of his old flying buddies, who were also at the University of Oklahoma, suggested he fly for the Naval Reserve out of Naval Air Station Dallas. He went to visit and, given his Navy flying experience, was quickly accepted into the Reserves. He flew in a non-pay status for the first three months and thereafter received pay. His Reserve commitment required him to drill one weekend each month and two additional weeks each year. Not only did he make more money in one weekend than he could working all month at a local part-time job at school, but he also got to keep flying, which he loved.

Joe’s service in the Reserves gave him the opportunity to fly all sorts of Navy aircraft. That happened because whenever the active-duty squadrons retired aircraft or received new planes, they sent their excess aircraft to the Reserves. As a result, Joe flew over 500 hours in the venerable Vought F4U Corsair and got to fly the Navy’s first operational jet (the McDonnell FH-1 Phantom) and the Grumman F9F Panther jet fighter. Amazingly, he didn’t attend schools to learn to fly these airplanes. He was simply handed the flight manual and told when he felt ready, he could give the planes a try. Give them a try he did, eventually achieving the milestone of breaking the sound barrier in the F9F. Not only did he fly countless hours around the Dallas/Fort Worth area, but he also flew training missions all around the United States. One of the most memorable of those missions included loitering at a low altitude over San Francisco Bay and watching the city’s lights come on. He can still picture it to this day.

Although Joe loved flying, he decided it was time to stop after a close call in California in 1959. As he was getting ready to take off one morning, his F9F Panther’s engine died. A main fuel line leak caused the failure. The maintenance chief told Joe he was lucky because in every other main fuel line leak he’d seen, the jet had gone up in flames. Joe continued flying for the rest of the fiscal year and then looked for other opportunities in the Reserves.

As for his civilian life, after graduating from the University of Oklahoma, Joe took a job with the accounting firm Arthur Andersen & Company in Dallas, Texas. Now a certified public accountant, he primarily audited oil and gas companies, but found himself traveling a lot. To be able to stay at home with his family, he accepted a position with one of his accounting clients, the Champlin Refining Company in Enid, Oklahoma. After spending three years there, he took a new position with the Trunkline Gas Company out of Houston, Texas, and later shifted to a position with its parent company, the Panhandle Eastern Pipeline Company, in Kansas City, Missouri. After seventeen years with Panhandle Eastern, he worked seventeen more years with the Kansas City Power and Light Company, before finally retiring in 1989.

Joe’s decision to transition away from flying in the Reserves dovetailed with his move to Kansas City. He started drilling at Naval Air Station Olathe, located just twenty miles southwest of Kansas City. Together with men possessing a wide range of backgrounds and talents, he was assigned to a weapons training unit and visited testing sites across the United States. This included nuclear facilities in Illinois, test flight facilities in California, artillery ranges in Colorado, and experimental aircraft testing sites for the McDonald Aircraft Company. Joe stayed in the Reserves until 1971, when he retired as a Lieutenant Commander (O-4).

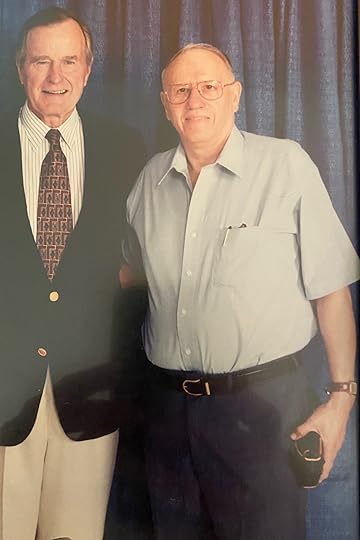

Joe and Betty Dwigans

Joe and Betty DwigansAlthough Joe retired from the Navy over fifty years ago, his Navy service remains a source of pride and accomplishment. He has been an active member of the Naval Reserve Association, helping sponsor University of Kansas Navy ROTC graduates as they embark on their Navy careers. He’s also been active in the Military Order of the World Wars, sponsoring high school students from the Kansas City area to attend leadership schools in Oklahoma City. He’s also the oldest living naval aviator in the Kansas City chapter of the Association of Naval Aviation.

As if that wasn’t enough, Joe has worked with local civic leaders to sponsor high school students to attend the christening of the USS Harry S Truman (CVN-75), and to ride the nuclear-powered submarine USS Jefferson City (SSN 759). During a Tiger Cruise from Hong Kong to Japan on board the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV-62) with his son, then-Lieutenant Commander Dean Dwigans, who was assigned as the ship’s judge advocate, Joe presented the ship’s commanding officer with a key to the city of Independence, Missouri. In return, the Commanding Officer presented him with a wooden model of the ship, which Joe gave to the City of Independence. Most recently, Joe participated in a Freedom Flight from Kansas City to Washington, DC, in recognition of his many years of military service to our nation.

Joe now lives with Betty in Kansas City. They have four children, Cathy, JoAnn, Cynthia, and Dean, and multiple grandchildren and great grandchildren spread across the United States.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Lieutenant Commander Joe Dwigans, U.S. Navy (Retired), for his many years of distinguished service in the Navy. From pilot training through his time as a carrier-qualified Helldiver pilot, he’s answered our nation’s call. He’s continued his service ever since, not only through the Navy Reserve, but also by introducing countless young adults to possible careers in the Navy. We sincerely thank him for his service and sacrifice, and wish him fair winds and following seas.

If you enjoyed Joe’s story, please sign up for the Voices to Veterans Spotlight monthly newsletter by clicking here. Once each month, you’ll receive a new written veteran’s story and a new podcast directly in your mailbox. Best of all, it’s free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

December 14, 2022

Sergeant Russell J. Wright, U.S. Army – Fighting with the Americal Division in Vietnam

Sometimes people are presented with options having life changing consequences. Such was the case with Sergeant Russell J. Wright, U.S. Army, when he received his draft notice in May of 1970. With the war in Vietnam winding down and protestors clamoring for draftees to flee to Canada, Russ could have evaded the draft and kept himself safe from a war that had already killed tens of thousands of Americans. Instead, he chose to do his duty and report for service because he knew it was the right thing to do. Now, looking back on his service in the jungles and rice paddies of South Vietnam over fifty years later, Russ is proud of his service and would do it all again. This is his story.

Russ was born in November 1949 and raised in the small farming community of Bement, Illinois, located in Piatt County approximately 160 miles south of Chicago. His mom and dad operated a family farm, so Russ and his four sisters learned at an early age how to work hard. Russ was driving a tractor by the time he was eight and soon was operating other farming tools, as well. He helped with planting and harvesting corn, with milking dairy cows, and with tending to the pigs. He also learned to handle a rifle safely and loved to hunt pheasant with his grandad.

Although Russ continued to work on the farm throughout his years at Bement High School, he still found time for outside activities. He particularly enjoyed Future Farmers of America, serving as an officer of the school’s club for three years. He was also a manager for the football team for three years, helped with the basketball team in the winter, and played in the band. He graduated from Bement High School in May 1967.

After graduation, Russ enrolled at Parkland Community College in nearby Champaign, Illinois. To pay for school, he worked part-time at the Bement Post Office while continuing to help on his parents’ farm. He graduated with an Associate Degree in Agriculture from Parkland in May 1969 as part of the college’s very first graduating class and began working for the Kaiser Chemical Company at a local fertilizer plant. Then, in November 1969, he received a notice to report to Chicago for a pre-induction physical to see if he was physically qualified for service in the military. Being in excellent physical condition after working his entire life on the farm, Russ passed his physical and returned home, hoping he would not be drafted.

In December 1969, Russ married his high school sweetheart, Debby Tempel. Together with his new bride and a good job at Kaiser, his future looked bright. Then, in May 1970, he received his draft notice with instructions to report for in-processing in June. Although the war in Vietnam was beginning to wind down, the military still needed men and lots of them, and now it was Russ’s turn. Needless to say, Debby and Russ’s parents were shocked, especially with the war and protests against it playing out in the news every day on television, but Russ was committed to serving his country. He had high school friends who were still riding out deferments and he knew some young men who went to Canada to avoid serving, but neither of those options were for him. He considered it his patriotic duty to report as ordered.

On June 10, 1970, together with about five other young men from Piatt County, Russ boarded a chartered bus in Monticello, Illinois, for the trip to the induction site in Chicago. On the way, the bus stopped in DeWitt County, Illinois, to pick up additional draftees. When the bus arrived at the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Chicago, Russ and his fellow travelers were joined by hundreds of others from across the state being drafted into the military. After getting checked in, eating breakfast, and completing a short follow-on physical to make sure nothing had changed since their pre-induction physicals, the draftees were lined up and told to count off. Every third person was designated as a Marine; everyone else – including Russ – went Army.

After being sworn in, Russ and the other Army recruits were loaded onto buses and shuttled to O’Hare Airport. They were originally slated for Basic Training at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri, but due to an outbreak of meningitis at the installation, they were instead instructed to board two big charter aircraft en route to Fort Polk, Louisiana. They landed at England Air Force Base in Alexandria, Louisiana, and transferred to buses for the last fifty miles. They arrived at Fort Polk around 3:00 a.m. and were hurried into the transient barracks to sleep, only to be roused at 6:00 a.m. to begin their first full day in the Army.

Despite the lack of sleep and the early start to the day, Russ found the transition to Army life fairly relaxed. They began by marching to chow, followed by in-processing activities for the next week. Russ wasn’t assigned to his Basic Training unit until June 19, and Basic Training didn’t begin until June 22. Even then, Russ found the experience tolerable because the drill instructors were trying out new techniques with Russ’s training company that proved very effective. Instead of the “in your face” approach drill instructors were famous for, they took a firm but fair instruction driven approach. As a result, Russ’s company scored much higher on proficiency tests than most other units.

Something else that made Russ’s Basic Training experience tolerable was his company’s billeting at North Fort Polk due to overflow conditions at South Fort Polk, where most of the training facilities were located. Given the distance from North Fort Polk, Russ’s company trucked to the training facilities rather than march to them as their counterparts at South Fort Polk did. This proved to be a substantial benefit given Louisiana’s high summer temperatures and humidity. Still, Russ felt his instructors prepared him well for what lay ahead.

Russ’s training company consisted of four platoons, with eighty-five percent of the men coming from National Guard units in Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Texas. Everyone got along well, with a healthy competition evolving in many of the areas of physical training, or “PT”. Russ was particularly good at “low crawling”, which his platoon practiced every night after chow. The men crawled fast on their stomachs twenty-yards out and twenty-yards back, all the time staying as low to the ground as possible. While competitive and fun at Fort Polk, the men knew the skill could save their lives in combat. Overall, Russ scored 95% on his physical fitness test.

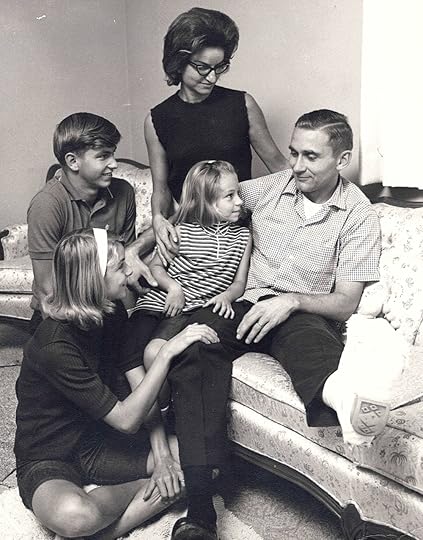

Debby and Russ Wright at Fort Polk, Louisiana

Debby and Russ Wright at Fort Polk, LouisianaBasic Training lasted eight weeks and Russ’s parents, his four sisters, and Debby came to his graduation. After graduation, the new National Guard soldiers returned to their units in their states, while draftees like Russ continued with Advanced Individual Training (AIT), although they were given the weekend off. As Russ’s AIT was also at Fort Polk, all he had to do was pick up his gear and move to the AIT barracks about three blocks away. Even nicer, Debby stayed in Louisiana to be close to Russ throughout AIT. Although she wasn’t permitted to stay on base, she lived about eight miles away in Leesville, Louisiana, visiting Russ in the evening and when he had off on weekends.

AIT for infantry soldiers at Fort Polk was conducted at Tiger Land, where they learned how to fight and survive in the unforgiving jungles and rice paddies of South Vietnam. They spent lots of time at the weapons ranges honing their skills, learned first aid, and practiced map reading. They also trained at night, learning how to conduct patrols and set ambushes. Russ notes the one thing they didn’t learn was how to embark and disembark the helicopters that would ferry them everywhere in Vietnam. All they had to practice on were some static mock-ups, but it wasn’t like the real thing, jumping off a hovering helicopter into tall elephant grass. That Russ had to learn on the job, watching what the other soldiers did and then following their lead.

Toward the end of AIT, Russ and the other soldiers took tests to determine what type of Army job they were best suited for, known as their military occupational specialty, or “MOS”. They were also asked where they would like to be assigned. The test results indicated Russ would do well as a truck driver or a clerk-typist and perhaps one other field. As for locations, Russ selected Germany, Alaska, and Hawaii. After considering his test results and preferences, the Army assigned Russ to the infantry and told all the soldiers they were going to Vietnam. At least for a moment, there had been hope.

Russ graduated from AIT in October 1970 after nine weeks of intense training. He had fifteen days leave before he had to depart for Vietnam, so he and Debby packed their car for the drive back to Illinois. They also found room in the car for two soldiers heading in the same direction, dropping one off in St. Louis and the other in Springfield, Illinois. At the end of his leave, Russ said goodbye to Debby and the rest of his family and boarded a plane in Champaign, Illinois, to start his trek to Vietnam via San Francisco.

Debby and Russ in Illinois on the night before Russ leaves for San Francisco en route to Vietnam

Debby and Russ in Illinois on the night before Russ leaves for San Francisco en route to VietnamWhen Russ arrived at the airport in San Francisco, one of the first things he witnessed was a bunch of people protesting servicemen returning to the States from Vietnam. He saw the soldiers quickly change into civilian clothes so the protestors would leave them alone. As this was going on, Russ and the other servicemen on their way to Vietnam took a shuttle flight to Oakland, followed by a bus to the Oakland Army Terminal, where they waited until it was their turn to leave. After three days, Russ’s number was called and he took a bus to Travis Air Force Base, where he boarded a chartered Flying Tiger Airlines flight for the final leg of his journey.

After refueling stops in Anchorage, Alaska, and Yokota Air Base in Japan, Russ’s flight landed at Bien Hoa Air Base, located twenty-two miles northeast of Saigon, on November 15, 1970 – just five months after Russ took his enlistment oath in Chicago. As the plane made its approach to Bien Hoa, Russ could see bomb craters in the surrounding countryside, driving home he was arriving in a war zone. When the plane opened its doors, Vietnam’s 100-degree heat and the smell of aviation gas hit Russ and the rest of the passengers all at once. They disembarked the plane and loaded onto buses with wire mesh covering the windows to prevent grenades from being thrown inside – another not-so-subtle reminder of where they were.

Because Russ came to Vietnam as an individual replacement soldier and not as part of a unit, his bus transported him to the 90th Replacement Battalion at Long Binh, located four miles southeast of Bien Hoa. While he waited there to find out what his assignment would be, he ran into some buddies from AIT who were on their way to the 101st Airborne Division. Finally, his assignment was posted – he was on his way to the 23rd Infantry Division (Americal Division), which was headquartered in Chu Lai in the I Corps area of responsibility, in the northern portion of South Vietnam.

Since Chu Lai was almost 350 miles north of Saigon, Russ had to take a C-130 flight to get to his unit. After a two-day layover in Da Nang due to weather, he and another soldier heading to Chu Lai boarded a C-130 for the final sixty-miles of the trip. As the plane descended to land, a fog filled the fuselage. Russ began to panic, thinking it must be smoke and that the aircraft was on fire. The crew chief assured him it was nothing more than fog caused by the hot, moist outside air mingling with the cooler air inside the aircraft as it made its final approach. The crew chief turned out to be right and the plane landed without incident.

Once in Chu Lai, Russ was met by members of his unit and taken to the Americal Division Headquarters, where he checked in. He was then sent to two weeks of combat refresher training to prepare him to join his unit in the field. When he returned from the combat training facility, he bivouacked in a church, together with about fifty other soldiers waiting for barracks rooms. Russ, now a private first class (E-3), celebrated his twenty-first birthday while staying in the church.

Russ was eventually assigned to Charlie Company of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 196th Infantry Brigade. As Charlie Company operated out of Firebase Hawk Hill further north on coastal Highway 1, Russ had to catch a ride on a two-and-half-ton truck (known as a “deuce and a half”) to get to the outpost. Once there, he was assigned to the company’s 3rd platoon, 2nd squad. His job as part of the squad was rifleman, his primary weapon being his M16 rifle.

Russ found the squad immediately welcoming. The squad leader, 1st Lieutenant Rodney Shortell, was squared away and really looked out for his men, as did the company’s 1st Sergeant, Gene Secrist. Everyone in the unit, whether black or white, career Army or draftee, helped each other. Everyone knew that out in the field, they would have each other’s back.

The platoon’s missions followed a pattern. The platoon would go into the field on patrol for up to fourteen days, then return to Firebase Hawk Hill for three days to re-arm, load up with rations, clean their weapons, and relax. Relaxation might involve spending time at the Enlisted Man’s Club, watching an occasional Korean band, or just sleeping. After three days, the platoon would head back into the field and start the cycle over again.

When Russ went into the field, he carried his M16 and a rucksack with 100 rounds of ammunition, canteens filled with water, C-rations, and a bandolier of M60 machine gun ammunition. He also carried a camera in his ammunition belt and a poncho – a critical piece of gear during Vietnam’s rainy season. At night, he could fasten his poncho together with that of a buddy and form a two-man pup tent, which at least theoretically would keep them dry in the rain. When fully loaded, Russ’s gear weighed eighty pounds, quite a load given Russ weighed only 140 pounds at the time. He and the other men often sat down to strap on their rucksacks, but then needed the assistance of another man to pull them to their feet under the heavy load.

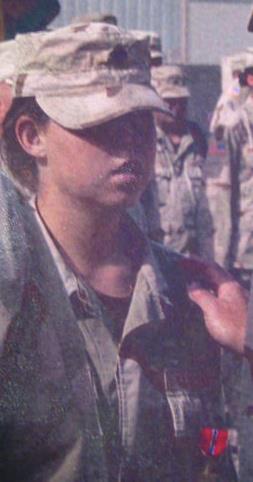

Russ with his M16 rifle equipped with an M203 grenade launcher

Russ with his M16 rifle equipped with an M203 grenade launcherWhen it was time to go on patrol, Russ’s platoon loaded onto helicopters, which ferried them to their jump-off point. Once out of the helicopters, the platoon formed up, with a point man taking the lead and keeping a watchful eye out for booby traps. Although Russ was never the point man, he was often the second man in line, known as the “slack man”. The slack man’s job was to protect the point man and direct him where to go, since he could not do so for himself because he was focused on looking for booby traps. After Russ gained enough experience, he was authorized to carry one of the squad’s two M16s equipped with the M203 grenade launcher. While this gave him considerably more firepower, it also meant he had to wear a grenade launcher vest stuffed with 40-millimeter high-explosive grenades, phosphorous rounds, and fragmentation rounds. Not only did that make his load heavier, but it also made it more dangerous if the ordnance he was carrying detonated.

On one patrol through an area of rice paddies, helicopters could not extract Russ’s squad at the completion of their mission because of incessant rain. The men’s boots became so waterlogged from the rain and trudging through the rice paddies that the skin on their feet started to split open. When it became clear they weren’t going to get picked up anytime soon, the patrol moved to higher ground until the weather cleared. After a while, they started to run out of food, so a soldier from Kentucky killed a wild pig. Although the fire they used to cook the pig might have given away their position, they were so hungry, they were willing to take the chance. After five days, helicopters were eventually able to make it to their position and return them to Firebase Hawk Hill.

Just before Christmas 1970, Russ and five or six other men from his platoon volunteered for a mission at another forward firebase. The week before Christmas and all the week after, they manned a listening post on a hill overlooking the surrounding area. At night, they used starlight scopes to watch for enemy troop movements. When they saw something, they radioed in an artillery strike to eliminate the target. At the completion of their rotation, Russ and the other volunteers from his unit returned to Firebase Hawk Hill and another group of volunteers filled in behind them.

By January 10, 1971, Russ was back in the rice paddies on patrol. As his platoon crossed the paddies, someone started sniping at them and Russ could see the bullets whizzing by. The platoon took cover in a grove of banana trees and pitched camp for the night. When it came time to depart the next morning, Russ’s squad was at the rear, so it was designated the last to pull out. When the lead squad started to move, Russ heard a big boom as the enemy detonated mines, killing two of the lead squad’s soldiers. The two bodies were evacuated by helicopter and the patrol went on.

Later in January, Russ’s squad was resting on a hillside while out on patrol. Russ was playing spades under a poncho when he looked down the hillside and saw two men standing in the creek bed at the bottom of the hill. When Russ pointed them out to the lieutenant, they were identified as Viet Cong and taken under fire. Both men were shot as they ran from the area. The squad recovered AK-47s and a radio from the two men killed. Two more men were also seen running from the area. The squad called in artillery to deal with them.

In February, Russ’s platoon was on patrol in the Central Highlands. As Russ was walking on a narrow mountain trail, he slipped and tumbled 100 feet down the mountainside. The fall injured his ankle and he couldn’t walk, so he had to be evacuated by helicopter and returned to the firebase for treatment. Fortunately, his ankle wasn’t broken, but he had to be put on light duty until he was cleared to go back into the field. When 1st Sergeant Secrist saw Russ was on light duty, he asked Russ if he could type. When Russ told him yes, Russ found himself typing the company’s morning reports until he was taken off light duty.

In late February, Russ and the rest of Charlie Company moved to Firebase Alpha 2 in Quang Tri Province, just south of the demilitarized zone, or “DMZ”, between South and North Vietnam. Their mission was to provide security for the outpost after South Vietnamese Army forces departed to participate in an incursion into Laos, code named Lam Son 719, to disrupt the flow of North Vietnamese supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Russ’s platoon could see a North Vietnamese camp just across the Ben Hai River with the North Vietnamese flag flying high on a pole over the camp. The sight of the flag so irked some of the men at the firebase that one night they fired a quad-mounted 40-millimeter gun at the flagpole to take it out. The North Vietnamese retaliated with a rocket attack on the firebase. The next morning, the rising sun revealed the pole had been hit and was bent over and damaged, so the unit considered the episode an American victory.

One event near the DMZ that did not turn out well was when Russ’s platoon was called upon to rescue two pilots from a downed helicopter. Although Russ’s platoon raced to the crash site as fast as they could, the North Vietnamese arrived there first and took both pilots prisoner. Russ does not know what became of the captured pilots.

Russ and his company were relieved from Firebase Alpha 2 by the South Vietnamese Army on March 28, 1971. This was the same day that a bloody Viet Cong sapper attack killed thirty-three Americans and wounded eighty-three more at Firebase Mary Ann, another firebase in Quang Tri Province. Consequently, all American units in the area were on high alert.

Charlie Company departed Firebase Alpha 2 and moved to Firebase Rawhide in the vicinity of Khe Sanh, the site of the storied Marine Corps defense against the determined onslaught of the North Vietnamese Army in 1968. The company remained there for a few months, while Russ returned to Firebase Hawk Hill to become the company clerk and mail clerk. Sadly, on May 4, 1971, a member of Charlie Company was killed and two more wounded during a rocket attack by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) at Firebase Rawhide. Russ had to report these casualties in the company’s morning report, as well as send the deceased soldier’s personal belongings to his next of kin.

At the end of May, both Russ and and the rest of Charlie Company moved to Camp Perdue, a former Marine Corps base southwest of Da Nang. Then in June, Russ was assigned to the Americal Division’s Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) in Chu Lai, where he was responsible for typing the morning reports for various companies in the division. He started out with eight reports, but that number continued to grow until he was doing at least fifteen reports every morning. With the exception of a week of leave he took in July to visit Debby back in Illinois, the morning reports were his primary responsibility through November 1971.

Finally, on November 10, 1971, Russ boarded a blue chartered Braniff Airlines jet in Da Nang to head home. The plane taxied onto the runway, only to stop to allow two battle damaged F-4 fighter aircraft to land. Concern quickly spread among the passengers that they had survived the war only to be exposed to a rocket attack as their plane waited to take off. Finally, the plane was permitted to depart. After the plane took off, the pilot announced when they cleared South Vietnamese airspace. Everyone erupted in cheers.

After a brief stop at Yokota Air Base in Japan, Russ’s plane flew nonstop to McChord Air Force Base, just outside of Tacoma, Washington. Russ proceeded to Fort Lewis, the Army base collocated with McChord, for out-processing from Vietnam. There he received a complementary steak dinner for his service in Vietnam, as well as follow-on orders to Fort Hood, Texas, because he still had time left on his original two-year Army obligation.

Before heading to Fort Hood, Russ flew home to Illinois on thirty-days leave to visit Debby and the rest of his family. Then he and Debby packed their car and drove to Fort Hood to start Russ’s new assignment. They arrived in December and rented a hotel room by the week, having gotten a good deal from the hotel owner, who happened to be from Illinois.

When Russ reported for duty, he learned that although he was a specialist (E-4), he had been selected for promotion while in Vietnam and was immediately eligible to wear the stripes of a sergeant. This not only meant more money for him and Debby, but it also meant he would have greater authority in his new role. Unfortunately, his new role was leading a squad of new recruits learning to work on tanks, which Russ knew nothing about. All he could do was march them to the motor pool, watch them work on the tanks, and then march them back to the barracks at the end of the workday.

This didn’t last long because in January 1972, Russ was offered an early out, which he readily accepted. In his last official act as a squad leader, he took his soldiers out on an exercise where they were the aggressors against a helicopter squadron closing in on their position. As the helicopters drew near, one of Russ’s men fired his weapon equipped with a flash suppressor and the pressure from the blank round firing launched the suppressor toward an oncoming helicopter, breaking its window. Russ’s unit was jokingly credited with shooting down the helicopter. Fortunately, no one in the helicopter was injured and the only damage it sustained was the broken window.

Russ was honorably discharged from the Army on January 21, 1972, having earned two Bronze Stars, two Army Commendation Medals, a Good Conduct Medal, and the Combat Infantry Badge. He and Debby drove back to Bement, Illinois, where Russ returned to work at the Kaiser Chemical Company. Then, in August 1972, he took a job with the Bement Grain Elevator (which later became the Topflight Grain Cooperative), driving an eighteen-wheel truck for twenty-four years and then transitioning to an office position for twenty more. He retired on November 21, 2016, after forty-four years with the company.

Russ (top row on the far left) and Debby (front row on the far left) at the reunion in 2008 in New Orleans

Russ (top row on the far left) and Debby (front row on the far left) at the reunion in 2008 in New OrleansNot quite forty years after the incident where Russ spotted the two men in the creek bed, he started feeling guilty about causing their death even though they were clearly Viet Cong guerrilla fighters and legitimate enemy targets. What bothered him most was at the time, he had no remorse for their deaths because it was his job to kill enemy soldiers. Debby did her best to help Russ work through it, but it was getting back together with the men of his platoon starting in 2008 that really helped him deal with what he now realizes was post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The group first met in New Orleans, and it was like they hadn’t skipped a beat since they last saw each other in 1971. They subsequently met in North Dakota in 2009 and at Arlington National Cemetery in 2010, where they tried to locate where the two men in their unit killed by the mines on January 11, 1971, were buried.

After learning that one of the men killed, Specialist Allen Gray, was from Belleville, Illinois, Russ returned home and contacted the Belleville newspaper and obtained a copy of Allen’s obituary. This led him to Allen’s brother in Texas and to Allen’s gravesite at the Valhalla Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. The men in Russ’s unit and Allen’s family, who did not know how Allen died, arranged to meet at Allen’s gravesite for a memorial service. Soldiers from Kentucky, Michigan, Wisconsin, Texas, and Illinois attended, as did an honor guard from Scott Air Force Base, located in Illinois outside St. Louis. Meeting everyone helped Russ deal with his PTSD and provided a degree of closure for Allen’s family. Russ stays in contact with Allen’s family to this day.

Russ is now retired and lives in east central Illinois, where he has lived since his discharge from the Army in 1972. Sadly, Debby passed away in 2020, but Russ’s and Debby’s four children (Matt, Marcus, Sarah, and Paul), seven grandchildren, and three great grandchildren still live nearby, so Russ has plenty of love and support from his family. He also remains active in both the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), serves in the Honor Guard for veterans’ funerals, and went on an Honor Flight for Illinois military veterans in 2017. He is incredibly proud of his military service and the men he served with, and if called upon to do so, would willingly do it all again.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Russel J. Wright, U.S. Army, for his dedicated service under fire during the Vietnam War. When the country called, he served willingly, putting himself in harm’s way to protect our freedom and that of our allies. He then returned to civilian life and together with his wife, Debby, raised a fine and loving family. Even while retired, he continues to serve his fellow veterans through the American Legion and the VFW. We sincerely thank him for all he has done and wish him fair winds and following seas.

Sergeant Russell J. Wright, U.S. Army

Sergeant Russell J. Wright, U.S. Army

November 9, 2022

Master Chief Petty Officer Donald Gohman, U.S. Navy (Retired) – Keeping the Navy Flying During Three Wars

Master Chief Petty Officer Donald Gohman, U.S. Navy (Retired), is a humble man. When we began to talk, he told me his career was routine and he didn’t think he’d done anything special. Then he told me about how he helped keep planes flying from Henderson Field during the six-month long battle for Guadalcanal during World War II and kept carrier aircraft in fighting shape for missions over Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Needless to say, I was spellbound. Weaving in and out of peacetime and war, Don’s career is a thirty-year American history lesson taught at the individual level. I could not get enough of it, and I think you will share the same view. This is his story.

Three-year-old Don riding Maude, one of the farm’s workhorses

Three-year-old Don riding Maude, one of the farm’s workhorsesDon was born in March 1924 and raised in Clear Lake, Minnesota. His parents owned a 240-acre farm, raising cattle, hogs, and poultry, and growing the grain to feed them. As Don was the only child, he learned to carry his weight on the farm at an early age. He drove his first team of horses when he was only five years old. He attended school in a one-room schoolhouse, progressing through the eighth grade. At that point, many children stopped attending school so they could work full time on their families’ farms. Don, however, asked his father if he could attend high school. Don’s father agreed, provided Don continued to do his work on the farm, which he did.

Getting to high school proved to be a challenge, especially in the harsh Minnesota winters. When the roads weren’t covered with snow and ice, Don rode his bike the three-and-a-half miles to St. Cloud Technical High School. When he couldn’t ride his bike, he rode a horse. On one particularly cold morning when the thermometer registered thirty-two degrees below zero, Don asked his dad if he had to go to school. His dad simply asked, “Can the horse make it?” Knowing the answer was yes, Don saddled the horse and headed to school.

Tragedy struck in the summer of 1940 when Don’s father passed away. His mother knew she and Don could no longer maintain the farm, so she sold the farm and took a housekeeping job with a family in St. Cloud where Don continued school. He finished his junior year in 1941, earning money during the spring and summer by working on local farms. The experience made him realize farming wasn’t the life he was looking for. Then he walked past the St. Cloud post office and saw his way out—a recruiting poster with a sharp looking Marine in his dress uniform. Since Don was only seventeen, he spoke to his mother and asked for her permission to enlist, which she gave. Then he headed to the recruiting office to join the Marines.

At the recruiting office, Don found a smartly dressed Marine looking every bit as good as the recruiting poster. Don told him he wanted to be a Marine, but the recruiter quickly dashed his plans. Although Don was in excellent physical shape and could outrun and outwork everyone he knew, the recruiter told Don that at 5’7” and 135 pounds, he was too small to be a Marine. Not to be deterred, Don walked down the hall to the Navy recruiter. There, in stark contrast to the spiffy Marine he’d just left, he found a Navy Chief Petty Officer with his feet up on his desk and his uniform jacket unbuttoned. The Chief asked Don, “Well son, what can I do for you?” Don told him he wanted to enlist, so the Chief asked him what he did. When Don said he worked on a farm, the Chief asked him if he worked with machinery. Don said yes and the Chief told him he had just the job for Don—aircraft mechanic. That was all Don needed to hear. He was ready to join the Navy.

On August 19, 1941, Don and one other recruit from the area boarded a bus and drove to the entrance processing station in Minneapolis. There he took his oath of enlistment and boarded another bus headed for boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Training Station north of Chicago, Illinois. They arrived at Great Lakes early on Wednesday morning, August 20, and immediately marched to the mess hall still wearing their “civvies” (civilian clothes). Breakfast consisted of baked beans, which the mess attendant piled onto Don’s metal tray. After he wolfed them down, a second class seaman (E-2) noticed Don wasn’t drinking his milk and told him to drink it. Don said he couldn’t drink milk and if he did, there would be a problem. The seaman told him to drink it anyway, so Don did as directed. He then threw up the milk and beans he had just consumed all over the table. His reward for being right was he had to clean up the mess, even though it wasn’t his fault. Needless to say, his enlistment was not off to a good start.

After breakfast, the new recruits marched to their barracks. Although some recruits were assigned bunks (called “racks” in the Navy), Don’s company had to sleep in hammocks like the ones found on older ships. All their possessions had to be stowed in their canvas duffel bags, known as seabags. To make their uniforms fit in their seabags, they had to neatly fold them and then tightly roll them into the smallest bundle possible. They then tied them with clothes stops so they wouldn’t unroll in the bag.

After breakfast, the new recruits marched to their barracks. Although some recruits were assigned bunks (called “racks” in the Navy), Don’s company had to sleep in hammocks like the ones found on older ships. All their possessions had to be stowed in their canvas duffel bags, known as seabags. To make their uniforms fit in their seabags, they had to neatly fold them and then tightly roll them into the smallest bundle possible. They then tied them with clothes stops so they wouldn’t unroll in the bag.

To test their packing skill, every week there was a seabag inspection, where the recruits had to lay all their clothing out on the floor. A lieutenant would then come by with a stick to test whether each recruit’s clothes were rolled tightly enough. During one such inspection, when the lieutenant arrived at the recruit next to Don, he didn’t like the way the recruit’s clothes were rolled, so he picked them up and tossed them out the window. The recruit then had to retrieve his clothes and re-wash them all by hand, which was the only way the recruits had to clean their clothes. Although Don’s clothes passed inspection, the incident motivated him and the other recruits to make sure their seabags were always ready for inspection. To this day, Don folds his socks the way he was taught at boot camp.

Because Don was in good shape when he arrived at boot camp, he had no problem with the physical training. He could run fast and do pushups and pullups, and unlike many of the recruits, he could swim well having grown up swimming and diving in Minnesota’s many lakes. He also played the accordion, which came in handy when his company Chief asked if anyone had any talent they could share with the other trainees. Don’s mother sent him his accordion, which he used to warm up a crowd of 5,000 waiting to watch an exhibition bout involving heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis. After Don finished playing, Joe Louis entered the ring and shook Don’s hand.

Don’s biggest disappointment came on payday. As a Seaman Recruit (the lowest Navy enlisted rank, or E-1), he expected to receive his full pay of $21/month. Instead, his first pay was just $12.67. When Don asked his Chief why the amount was so small, the Chief told him he had been charged for things like the bucket and soap he used to wash his clothes. Don was pretty sure someone was skimming something off the top of his pay, but there was nothing he could do about it. Aside from that, he thought his Chief trained his company well.

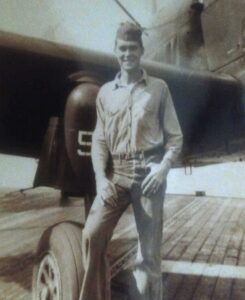

Don and his mom

Don and his momAfter graduating from boot camp in early October 1941, Don took leave to visit his mother and his buddies back in St. Cloud, Minnesota. Much to his chagrin, his mother wanted him to go with her to visit her mother in Centerville, Iowa. Don could think of nothing more boring and was upset he would not get to spend any time with his friends. Once he got there, though, he noticed a pretty fifteen-year-old girl named Darlene living across the street. On his last day in Centerville, he summoned the courage to speak to her and they ended up talking for a couple of hours. Then it was time for Don to go and he boarded a train for his next duty station in Jacksonville, Florida.

In mid-October 1941, Don reported to Naval Air Station Jacksonville for Aviation Machinist Mate school. He specialized in aircraft engine and propeller mechanics, becoming proficient in both areas. He also volunteered for combat aircrew training, which meant he learned how to be a gunner on aircraft that would operate from the Navy’s aircraft carriers. He proved to be an expert shot because of his experience hunting ducks in Minnesota.

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Don returned to the barracks after church and lunch and learned Pearl Harbor had been attacked by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The news had an Orson Wells-like feeling, with no one believing it could be true. Once reality set in, the atmosphere was subdued, at least until the next morning when Don and the other sailors in his training section were mustered in their summer white uniforms for combat training. They soon found themselves crawling through the grass in their whites, none of them with weapons or any sense of the purpose for the training. From that point on, Don and the rest of the Navy were on a wartime footing.

In February 1942, Don departed Naval Air Station Jacksonville and reported to Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia, to continue his training. This advanced-level training included attending two six-week courses at the Curtiss-Wright Engine School and the Curtiss Electric Propeller School. Finally, by the summer of 1942, Don was ready for his first assignment. Initially, that was Marine Corps Air Station, Cherry Point, North Carolina, doing maintenance on aircraft hunting for German submarines off the East Coast of the United States. Then he and the men he was with, about 120 in total, departed Cherry Point by train on a non-stop trip to Naval Station Treasure Island, located all the way across the country on San Francisco Bay. They had no idea what their mission or ultimate destination was. All they knew was they were on a secret wartime mission.

Once at Treasure Island, Don and the other men of his unit loaded onto two rusty Dutch merchant ships. Thirty-two days later, they arrived in Noumea, New Caledonia, a French controlled island located approximately 750 miles off the east coast of Australia. More important, Noumea was located approximately 850 miles south of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, which was about to become the focal point of the Pacific War. Don’s team, now part of a composite unit identified as Acorn Red One and consisting of his aircraft mechanics and a battalion of Navy Seabees, loaded onto Navy transports and headed toward one of the most pivotal battles of World War II.

On August 7, 1942, the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal and quickly captured and secured the main airstrip, renamed Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, the first Marine aviator killed in the Battle of Midway. Two days later, Don and the other aircraft mechanics went ashore, waiting for the Seabees to finish work on Henderson Field and for the arrival of the U.S. aircraft that would operate from the airstrip when complete. By August 18, the field was ready and the first Marine squadrons flew in two days later. Don’s job was to keep the aircraft, dubbed the “Cactus Air Force”, flying so the pilots could attack Japanese Army forces on the island and Japanese Navy forces menacing the waters around Guadalcanal.

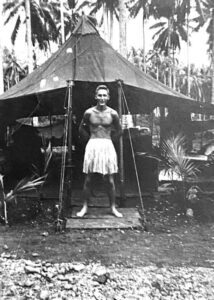

Don in a lighter moment on Guadalcanal

Don in a lighter moment on GuadalcanalThe conditions on Guadalcanal were horrendous. Henderson Field was under constant attack from Japanese ground forces, naval forces, and air forces, especially at night. Powerful Japanese battleships and cruisers periodically shelled Henderson Field from off the coast while every night Japanese bombers dropped bombs on the U.S. defenders below. The nighttime attacks by high-flying Japanese “Betty” bombers became so routine that Don and his friends reacted nonchalantly when the air raid siren wailed. Instead of heading immediately to their shelters, they posted a lookout to watch the searchlights sweeping the sky for Japanese airplanes. Only when the lights appeared directly above them would they take cover; otherwise, they would remain in their tents and try to get some sleep.

During one such attack, the assigned lookout yelled the searchlights were right above them and everyone scrambled out of their tents. Two Japanese bombs exploded nearby, hurling shrapnel everywhere. Fortunately, two big coconut trees that had been made into tables shielded Don from the blast. Otherwise, he is certain he would have been injured or killed by the bombs.

Don and his fellow mechanics did everything they could to keep the planes of the Cactus Air Force flying. Sometimes this meant overhauling engines or replacing propellers, while other times it meant scavenging parts from disabled aircraft or patching bullet holes with tape and painting over it. Don even helped resolve a problem with Major “Pappy” Boyington’s F4U Corsair’s supercharged engine and got to meet the Medal of Honor recipient in person.

Although Don worked on lots of aircraft, he was specifically assigned to maintain a particular Douglass SBD “Dauntless” dive bomber, which meant he also occasionally flew as a gunner on the plane. The theory was if he knew he was going to fly in the plane, he would be especially careful in maintaining it. He and the other maintenance personnel had to sleep under their assigned aircraft in case they were needed on short notice. This was terrifying because individual Japanese soldiers occasionally infiltrated the Marine perimeter around Henderson Field and slit the throats of the sleeping sailors. This memory is particularly difficult for Don even after the passage of eighty years.

When word circulated that the Japanese were going to make a concerted attack to retake Henderson Field, Don’s situation became precarious. Bulldozers pushed a protective berm of dirt around the airfield and Don and other members of his unit were issued M55 Reising guns, which looked like .45 caliber pistols with a rifle stock. Don was shown the defensive perimeter around the airfield and told when the first line of sailors was gone, his job was to fill in behind them and hold the line. Fortunately, the Marines held the perimeter against the Japanese attacks and Don never had to take a place in the line.

As if the constant attacks weren’t enough, tropical rains turned the ground into a deep, thick mud. Bugs and snakes were everywhere, and malaria and dysentery were rampant. Don took Atabrine to fight off malaria, but it turned his skin and urine bright yellow. Occasionally, he used the conditions to break the monotony and play jokes on his fellow sailors. One sailor, in particular, was afraid of snakes. Don found a length of rope on the dock, tied a string around it, and put it under the covers of his friend’s cot. When the friend fell asleep, Don pulled the string and the friend, thinking there was a snake in his rack, came flying off the rack to get away.

Once the situation on Guadalcanal stabilized, beer started to arrive on the island and it became a much sought after commodity. When some of Don’s friends learned a cargo ship had arrived with a shipment of beer, Don and his buddies took a small vessel known as a lighter out to the ship to commandeer their share of the beer. Just after the cargo ship deposited the first load of beer in the lighter, an Australian patrol boat came by blaring that a Japanese submarine was in the area and that the cargo ship should get underway immediately. Before the lighter could clear the area, the Australian patrol boat dropped depth charges on the suspected target. When they detonated, the lighter bounced up, tossing the beer in the water. Disappointed, Don and his friends made their way back to shore empty handed.

Although Don lost the beer, there were other ways to get alcohol. Some of the maintenance team noticed that on their way out to the aircraft on the flight line, they had to walk past a field where flares were stored. The flares were attached to small silk parachutes so that when the flare was fired from an artillery piece, it would slowly descend to the ground, lighting up the night sky as it did. Some of the men cut off these parachutes, painted the Rising Sun on them, and sold them to new arrivals on the island telling them they were captured Japanese flags. The men then used the money they made to buy whatever alcoholic beverage might be available.

Don had to be medically evacuated from Guadalcanal in June 1943 after coming down with malaria. He’d been on the island for ten months, surviving everything the Japanese had thrown at Henderson Field and the Cactus Air Force. Although barely nineteen and a Second Class Petty Officer (E-5), he’d already seen a lifetime of war. Yet for him, the war was just beginning.

Don in New Zealand

Don in New ZealandDon spent the rest of June and all of July 1943 recuperating in a hospital in New Zealand. The winter weather was a welcome change from the tropical heat of Guadalcanal and his stay was uneventful. At the end of July, he returned to Noumea to find a way back to the States for his next assignment. He managed to get orders to hitch a ride on the USNS Rappahannock, a fleet oiler returning to Naval Base San Diego. On the way back, the ship stopped in Bora Bora, which Don describes as the most beautiful island in the world. Don arrived safely back in San Diego in August 1943.

Once back in the States, Don reported to Naval Air Station Alameda near San Francisco to await orders. While there, he had a second bout with malaria even worse than the first. After he was back on his feet, he made his way to Hawaii, where malaria hit him a third time. This time it was so bad he nearly died. Again, he recovered and caught up with his aircraft maintenance unit on the island of Roi-Namur in the Marshall Islands, which the Marines had already wrestled from the Japanese. From there they went to Tarawa, going ashore in November 1943, just after the Marines stormed ashore in what was to be one of the bloodiest battles in the Pacific War.

Before Don’s unit could begin its work maintaining aircraft on the atoll’s airfield, it had to assist burying over 5,000 of the Japanese defenders killed during the assault. The job got even worse when the smell of death started seeping from a Japanese bunker next to Don’s maintenance tent. Rather than cleaning out the bunker after it had been disabled, the Seabees simply bulldozed dirt over the top of it. Now it had to be opened and Don and the other members of his unit had to go inside and remove the human remains. The odor permeated their bodies. Even after showering and putting on new clothes, they smelled like death. So much so that when the unit entered the chow hall, everyone else left.

In early 1944 and after a brief ordeal with bed bugs on Kwajalein Island, Don and his unit moved to Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands, which had been captured by the Marines in January 1944. The atoll soon became a major forward staging area. The Navy prepositioned about sixty replacement carrier aircraft at the airfield as part of its theater-wide aircraft pooling strategy. U.S. Navy pilots flew their old or damaged aircraft to the airfield on Eniwetok and returned to their aircraft carriers flying the newer model replacement aircraft. Don and his team either fixed or jettisoned the old or damaged aircraft, making room for more new replacements. As a result, Don became an expert working on all types of Navy aircraft, including the SBD “Dauntless” dive bomber, the TBM “Avenger” torpedo plane, the SB2C “Helldiver” dive bomber, the F4F “Wildcat” fighter, and the F6F “Hellcat” fighter.

When Don first arrived on Eniwetok, though, his group, now numbering about twelve Second Class Petty Officers, had nothing to do because no planes requiring work had yet arrived. Accordingly, they set up their tent near a bakery and found a lieutenant who needed help unloading lighters bringing supplies ashore. In return, the lieutenant allowed them to “borrow” some of the supplies, including real potatoes, ice cream mix, and beer. They then traded some of their supplies to the bakery in return for even better goodies.

The arrangement worked great until one night when the group of twelve was cooking French fries and drinking beer kept on ice in empty ammo cans, they saw a man wearing a khaki uniform approach. This meant he had to be a Chief or an officer. It turned out to be even worse than that—he was the base Commanding Officer (CO). He asked the men how they were doing and one of the men, loosened up by the alcohol, said they were doing just fine and offered the CO a beer. He politely declined and when he learned the group had nothing to do, he put them to work on the airstrip fire crew.

Even though Don arrived on Eniwetok after the fighting was over, there were still grim reminders of the war. One evening, a bomb-laden Navy PB4Y (the Navy’s version of the four-engine B-24 “Liberator” bomber) roared down the runway for takeoff when two of the engines failed. The bomber tore through the pool of parked carrier planes, destroying around twenty-five aircraft and killing everyone on board the PB4Y. A Seabee used a bulldozer to roll the unexploded bombs from the plane away from the burning aircraft, which came to a stop only fifty to sixty feet from Don’s maintenance tent.