David E. Grogan's Blog, page 6

April 20, 2021

Master Sergeant Jay Cyril Mastrud, U.S. Air Force – Navy First, Air Force Always

The road through life is never straight and rarely fair. Some begin their journey with a supportive family and an adequate income, giving them a head start along their way. Others are not so fortunate, facing seemingly insurmountable hurdles that conspire to keep them from continuing. Yet they drive on, navigating around the hurdles until they reach a place where they can look back with pride at what they have accomplished. Such is the case for Master Sergeant Jay Cyril Mastrud, U.S. Air Force. Despite the hurdles placed in his path, Jay never gave up. He went from his roots in the Navy to become a successful and respected leader in the Air National Guard. He is a strong advocate for not trying to go it alone, but for reaching out to others for help when the hurdles seem too high. This is his story.

Jay was born in 1969 and raised in Cicero, Illinois, just thirty blocks north of busy Midway Airport in Chicago. The town was part of Chicago’s industrial backbone and home to such companies as General Electric Hotpoint and Western Electric. Jay’s father drove a catering truck selling food to the many workers in the local area factories, and his route took him through some rough areas. His father was robbed on more than one occasion and even shot at on the job, making his work situation very stressful. Not knowing how to deal effectively with the danger, and having spent some time in jail and suffered trauma as a child, he brought his stress home and created a chaotic environment for Jay and his mother and siblings. Making matters worse, Jay’s mother, who immigrated from Europe, struggled with drug and alcohol abuse and unprocessed trauma of her own.

Jay’s family situation made him want to spend as little time at home as possible. Growing up, he did the kinds of things most kids in his neighborhood did, playing baseball and tackle football (without pads), watching trains go by on the nearby railroad tracks, and sneaking into the local racetrack with friends to watch the races. He had a tough time at school, not because he wasn’t smart enough, but because his home life made it difficult to stay focused or do homework. As a result, he took the vocational path through high school. This offered many advantages, particularly because his school, J. Sterling Morton High School East, was surrounded by factories in need of workers with a trade. When the school offered Jay the opportunity to learn about electronics, he found a hands-on subject he liked that could help him escape the chaos at home.

When it came time for graduation in June of 1987, Jay’s father gave him three choices. He could join the military, go to college, or get a job and pay rent. While Jay appreciated the clear choice his father offered, it was really no choice at all. College didn’t seem like a viable option at the time and there was no way he could continue to live at home – he had to get out of the house just like his older brother had done. That meant joining the military. Although his brother, Steven Grimes, had been a Marine, and Jay had a friend who wanted him to go Air Force, it was the Navy that caught Jay’s attention. So much so, that he remembers the recruiter’s name to this day, Petty Officer Second Class William Carmean, who worked out of the Berwyn, Illinois, recruiting office.

Jay’s only request was that he be assigned some place out west. Petty Officer Carmean said he could guarantee Jay a West Coast assignment, but could not guarantee the type of work Jay would be doing, known in the Navy as a “rate”. That would be up to the needs of the Navy wherever Jay was ultimately assigned. That was good enough for Jay and he signed his enlistment papers.

Jay reported to the Chicago Military Entrance Processing Station, or “MEPS”, in the summer of 1987 to begin his enlistment. After passing a physical exam and taking the oath of enlistment, he was officially a Navy recruit. Together with several other Navy recruits who reported the same day, Jay boarded a Chicago area Metra commuter train bound for boot camp at Naval Station Great Lakes, just of few miles north of Chicago. He remembers his assignment as if it were yesterday: Company 396, 13th Division, Compartment D1, Rack 1106. He also remembers boot camp was a tough transition for him as he went in a little overweight, which garnered him extra attention and lots of additional pushups. He managed to maintain a positive attitude throughout, which helped him successfully navigate the many challenges he faced.

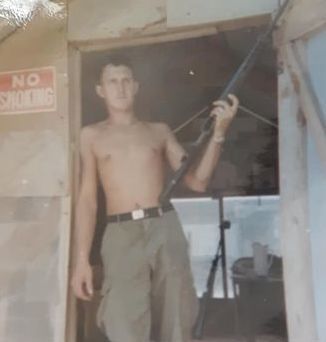

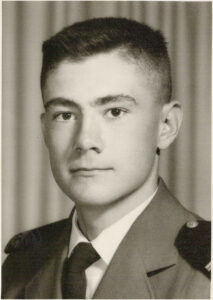

Jay Mastrud at Boot Camp

Jay Mastrud at Boot CampWhile at Great Lakes, Jay and the other recruits had the opportunity to meet with detailers, who were the Navy officials determining where the recruits would be sent for their first duty station. When it came Jay’s turn, the detailer told him his Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB) scores in the electronics field were off the chart. Suddenly, his vocational training in high school was paying off. The detailer gave him the choice of three electronics ratings to work in, and Jay chose the Aviation Fire Control Technician rate, abbreviated as “AQ”. This meant the Navy would train Jay to maintain and repair the advanced electronics weapons systems on aircraft deployed on ships around the world. He saw this as an exciting opportunity.

Before Jay could work on the equipment in the fleet, he had to go to another Navy school to learn his new trade. That happened after he graduated from boot camp on November 9, 1987. He left Naval Station Great Lakes and headed to O’Hare Airport in Chicago for his first flight in an airplane. He flew to Memphis, Tennessee, and then took a shuttle to the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Millington, Tennessee. There he attended an “A” school, learning the fundamentals of his new AQ rate. As he loved working on electronics, he did well and enjoyed his time there. One incident, however, had a lasting impression on him. When he was standing fire watch one night in the barracks, one of the sailors living there slit his wrists with music from Led Zeppelin blaring in the background. Jay roused the duty petty officer from his rack to see what was going on and found the sailor in his room with blood everywhere. Jay and the duty petty officer quickly got the injured sailor medical attention and he recovered, but the scene never faded from Jay’s memory and no one senior to him recognized that the event likely traumatized both Jay and the duty petty officer. Jay graduated from “A” school in July 1988.

Although Jay had enlisted in return for an assignment on the West Coast, he received orders to report to fighter squadron VF-32, which was located at Oceana Naval Air Station in Virginia Beach, Virginia. The squadron flew the F-14A “Tomcat”, which Jay had seen in the 1986 movie Top Gun starring Tom Cruise as Maverick. When he arrived at Oceana, the squadron already was at sea, deployed onboard the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67). That meant boarding another plane and flying to Naval Air Station Sigonella in Italy, where he stayed for almost a week. He then proceeded to Naples, Italy, to meet the ship and join his new squadron underway.

When Jay reported to his squadron, he did not start working on electronics equipment right away because he was just an Airman Apprentice (E-2) with no prior Navy experience under his belt. Instead, he had to pay his dues learning about life at sea. That meant doing an initial assignment with the ship’s 1st Lieutenant, cleaning “heads” (bathrooms) and berthing spaces and doing laundry for the thousands of sailors living onboard the ship. When he was finished with that assignment, he was sent on another temporary assignment “mess cranking”, which meant he was tasked with helping out in the ship’s galley feeding the same sailors he had just cleaned and done laundry for.

USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) in 1991. Source: U.S. Navy

USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) in 1991. Source: U.S. NavyGiven the size of the USS John F. Kennedy and the number of sailors onboard, the ship had several galleys. Jay was initially sent to work in the Air Wing galley where most of the enlisted members of his squadron ate, but it didn’t need people at that point, so he went to work in the ship’s main galley feeding the sailors assigned to the ship itself. Jay was fortunate to work for a Leading Petty Officer (LPO) and a Leading Chief Petty Officer (LCPO) who were both outstanding leaders. He credits them with setting him on the right path even though the work itself was not the most appealing. They wrote him excellent evaluations for the time he spent mess cranking and set him up for success with his squadron.

Jay and VF-32 returned to the United States onboard the USS John F. Kennedy in February 1987. Now an Airman (E-3), Jay was given the option to either work as a plane captain for another year at Oceana Naval Air Station or go directly to Integrated Weapons Team Work Center 280 to begin working on the equipment he had been trained to maintain and repair. Jay took the work center option, which allowed him to finally get back to doing what he really enjoyed and meet a great bunch of guys in the process. Although taking the option added two years to his enlistment, it allowed him to promote to Petty Officer Third Class (E-4) faster, making life in the Navy better all around.

Jay had one more deployment with VF-32 aboard the USS John F. Kennedy beginning in August 1990 in support of Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Operating from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea, the aircraft carrier launched planes on combat missions against Iraq after it invaded Kuwait. The difference between this deployment and the previous one was that Jay was now a seasoned electronics technician, so his skills were essential in keeping VF-32’s Tomcats flying. He remembers spending many nights on the ship’s flight deck near the two F-14 fighters on “Alert 5”, meaning the planes were ready to be catapulted into the air on five-minutes notice. He and other maintenance people were on hand in case a last-minute problem developed that had to be fixed. Since there were lots of times when nothing went wrong, it gave the maintenance people the opportunity to talk and get to know one another. Jay recalls those conversations as some of the best discussions of his life.

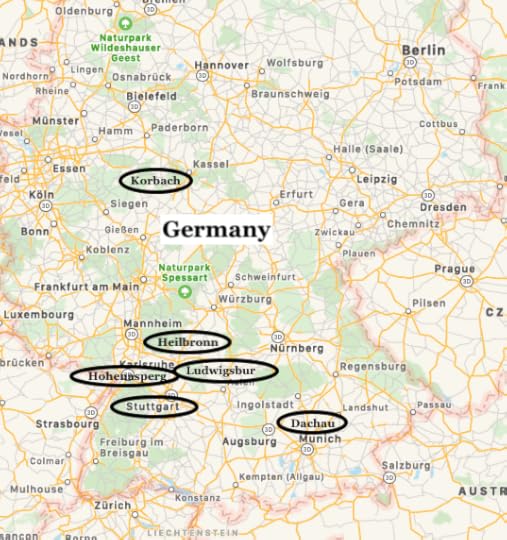

Jay’s port visits in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea

Jay’s port visits in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea and the Red SeaAlthough the deployment was deadly serious, the ship made a few port calls and Jay got to visit some amazing places. He went ashore in Izmir, Turkey (where he visited ancient Greek and Roman ruins and met Kurds in person for the first time); Hurghada, Egypt; Alexandria, Egypt; and Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. In Jeddah, he was assigned to shore patrol duty on liberty buses transporting crewmembers around the port. He befriended the Saudi driver of one of the buses. The driver took him to a café where, according to local custom, Jay used his hands to eat rather than with western utensils. This opportunity to enjoy a meal with the Saudi bus driver stands out as one of Jay’s more memorable deployment experiences.

With the Desert Storm mission accomplished, Jay returned with VF-32 and the USS John F. Kennedy to the United States in March 1991, completing an almost nine-month deployment. Jay stayed with VF-32 at Oceana Naval Air Station until September 1992, when he decided to go back to being a civilian. After his discharge from active duty, he spent time touring Europe and even attended school in Spain, but ultimately returned to the United States and settled in Houston, Texas. While he was in Houston, he affiliated with the Naval Reserve and drilled with VFA-204, a Navy Reserve strike fighter squadron of F-18 “Hornets” flying out of Naval Air Station New Orleans. In 1994 he shifted to VFA-201, which flew out of Naval Air Station Dallas. Drills at both squadrons consisted of spending one weekend each month and two weeks each year working on F-18 Hornet radar systems, electronic countermeasure systems, communications systems, weapons systems, and other aircraft avionics. Although he especially enjoyed his time at VFA-201, by the summer of 1995 he needed a change and moved back to Chicago to live with his parents.

Moving back with his parents rekindled painful memories from Jay’s childhood and brought back stress and chaos to his life. He tried to stay affiliated with the Navy Reserve, drilling at Naval Air Station Glenview, but after just two monthly drill weekends, the installation closed as a result of the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRACC). He then shifted to drilling at the Great Lakes Naval Reserve Center, but that lasted for only a few months, as well. Not only did the Reserve Center have little for him to do, but when also coupled with the college studies Jay had begun at Harold Washington College and the unresolved family trauma he continued to deal with, it was just too much for him to handle. Although he took a break from drilling, he continued to work a variety of odd jobs to cover his school costs and rent, including helping his father with his catering truck and working security at Soldier Field.

Eventually, Jay decided to pursue his Bachelor’s degree. After applying to a number of schools, he enrolled at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis-St. Paul. He saw this as an opportunity to both further his education and get out of his parents’ house. Once he arrived in the Twin Cities, he drilled with a Navy Reserve unit there, but they had nothing for him to do and he was bored. Not wanting to waste his time, he changed his status from a drilling reservist to the Individual Ready Reserve (IRR). This kept him on the Navy Reserve’s rolls in case he was needed, but he no longer needed to drill. When his IRR obligation expired in 1998, the Navy was officially in Jay’s past.

In looking back over this period of his life, Jay realizes he would have benefitted from counseling to help him address the nagging issues from his childhood. As a kid, he was often in the “flight” mode, trying to get away from the bad situation at home. Now that same instinct made it difficult for him to find direction and focus. The result was he struggled to find himself and couldn’t get across the finish line for either his Associate’s or his Bachelor’s degree.

Jay Mastrud having some fun while training with the Wyoming Air National Guard

Jay Mastrud having some fun while training with the Wyoming Air National GuardThere was one aspect of Jay’s life that did provide structure and direction—his service in the military. Jay recognized that and again sought it out, this time enlisting as a Staff Sergeant (E-5) in the Minnesota Air National Guard in December 2000. The Air National Guard was a perfect fit for Jay given his prior Navy experience as an electronics technician, and it promised meaningful work he could do while attending classes at the University of Minnesota. He was initially assigned to the 133rd Maintenance Squadron of the 133rd Airlift Wing, where he worked on the avionics for the C-130 “Hercules” transport plane. Since he already had extensive training in the Navy, he asked for and was told he would get a waiver from the Air Force’s basic electronics training school, but his command never obtained the waiver. Accordingly, in July of 2001, he transferred to the Iowa Air National Guard.

Although Jay’s transfer to the Iowa Air National Guard was significant, the most important event of the summer was his marriage to his wife, Heidi. As they began their lives together, Jay also began drilling with the 133rd Test Squadron in Fort Dodge, Iowa. The assignment entailed Jay going to school at Keesler Air Force Base on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi to learn to work on ground radars. Then, on September 11th, the world changed with the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia.

After the attacks, Jay was activated to full-time active status and deployed stateside in response to the national emergency. Not only did this make for a rough start for his marriage to Heidi, but it interrupted his studies at the University of Minnesota. Once his active duty period ended in 2003, he returned to Minnesota to pick up where he left off. He also returned to the Minnesota Air National Guard in September 2003, this time as part of the 210th Engineering & Installation Squadron, drilling at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport. This assignment was a good fit for Jay, and it complemented his new full-time civilian employment in 2007 with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). He even got to deploy with the unit to Alaska and was promoted to Technical Sergeant (E-6) in 2007. However, the assignment involved a lot of travel and was very tough on Jay’s family, which now included two young children who needed him at home. Although that would be sufficient reason in and of itself, Jay’s mother-in-law was battling cancer and her health was declining. Accordingly, in 2009, Jay decided it was time to hang up his boots and end his Air National Guard career.

By late 2009, lots of the pieces in Jay’s life were starting to fit together in a way that made Jay’s transition to a full-time civilian possible. He had a stable, good-paying job with the FAA. He’d finished his Associate’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harold Washington College in May of 2006, earned his Associate’s degree in Electronics Systems from the Community College of the Air Force in November of the same year, and earned his Bachelor’s degree in Classical Civilization from the University of Minnesota in May of 2008. He also had a wonderful family he loved very much. He still, however, had unresolved trauma from his childhood that kept him from experiencing the joy in life he knew he should be feeling.

Jay thought that perhaps connecting with other veterans through the American Legion or the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) would help him come to terms with his past. For some reason, he convinced himself he didn’t fit in, even though the veterans he met were very welcoming. Then around 2010, he found Veterans in the Arts. The program offered veterans a way to find healing from trauma experienced in the military through a wide range of art projects, including writing, theater, glass blowing, and pottery. Jay took a chance and tried it. The results were life changing. The program introduced him to a number of veterans with different military experiences—some not as positive as his—and helped him see things through their eyes. Being accepting of their experiences also helped him deal with his own trauma, and for the first time, he sought professional counseling to help him come to terms with his past. He even co-founded the Warrior Writers Twin Cities writing group with two other veterans and had an article published in November of 2016, The Pacifist Preacher & Quanah Parker. At the same time, he became involved with the Veterans Play Project produced by Wonderlust Productions, which had several performances at historic Ft. Snelling in Minnesota. This experience further broke down barriers for Jay by exposing him to people with differing backgrounds and views, all bonding together through the arts.

Jay Mastrud sightseeing in Gdansk, Poland

Jay Mastrud sightseeing in Gdansk, PolandOn the road to healing and with a better view of who he was in hand, Jay returned to the military in August 2012. He enlisted in the Air Force Reserves in Minneapolis, drilling with the 27th Aerial Port Squadron of the 934th Airlift Wing at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport, where he planned and organized air transportation activities. He did this until August 2014, and then transferred to the Wyoming Air National Guard in December of that year, where he drilled with the 243rd Air Traffic Control Squadron until May of 2019. In this assignment, he provided technical expertise in maintaining air traffic control equipment and deployed with the unit to maintain combat readiness.

In September of 2019, Jay transferred to the Wisconsin Air National Guard with the 128th Air Control Squadron, to drill closer to home. Jay is responsible for maintaining the unit’s transportable ground radar system and for training other unit members to do the same. He’s deployed to Poland augmenting an active duty unit from Italy and feels as though the assignment has really allowed him to blossom as a leader. In fact, in May of 2020, he promoted to Master Sergeant (E-7), validating his long commitment to military service and his years of searching for and finally finding his military identity. The assignment has also allowed him to connect with others in the command who Jay admires because they model what it is to be a true citizen-soldier.

Today, Jay and his family live in St. Paul, Minnesota. Having learned from his own experience the importance of positive relationships and personal accountability, he is a staunch advocate for seeking professional help to overcome trauma, PTSD, and any other of life’s hurdles. He sees doing so as a sign of strength and determination, and is living proof that it works. He urges others who may be struggling to seek out the help they need, and not suffer needlessly while trying to “fix things” on their own.

Voices to Veterans is proud to Salute Master Sergeant Jay C. Mastrud, U.S. Air Force, for his years of dedicated service in the Navy and the Air National Guard. Not only did he serve during a wartime deployment on board the USS John F. Kennedy during operation Desert Storm, but he has dedicated years of his life to the Air National Guard, keeping aircraft flying and radars protecting our skies. For his years of service, his personal sacrifices, and the leadership he continues to provide in both his military and civilian assignments, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

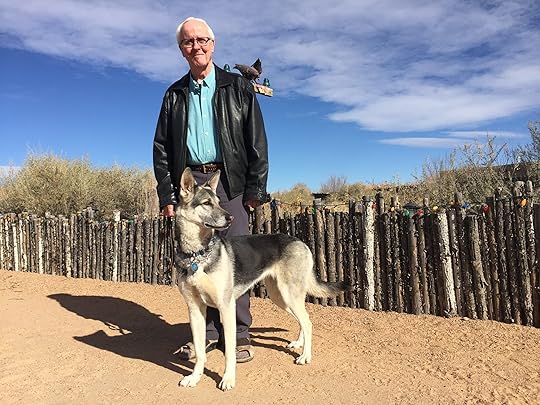

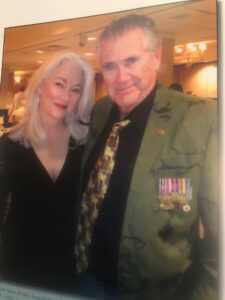

Jay and Heidi Mastrud

Jay and Heidi Mastrud

March 22, 2021

Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond, U.S. Army – Vietnam: Not Scared, Not There

There’s nothing like growing up in a small town. Close-knit families and neighborhoods, safety and security from the hustle and bustle of the city, and the freedom to roam and explore without fear. Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond grew up in such an environment, rarely venturing beyond his familiar Wisconsin surroundings. Yet even a trip to nearby big cities like Milwaukee or Chicago paled in comparison to what the U.S. Army had in store for him, shipping him off at just twenty-one to far off outposts in South Vietnam in the middle of a raging war. Although he returned to his small town after the war, his life was forever changed. This is his story.

Kenny was born in 1949 and grew up in Genoa City, Wisconsin, a small village just north of Wisconsin’s border with Illinois. At the time, the village had about 1,000 residents, so life there epitomized life in every small town in America. Kenny’s father, a World War II veteran, had a great job as a die caster for the Electric Autolight company in Woodstock, Illinois, making parts for cars like the famous hood ornament for the Ford Mustang. Kenny’s mother was a full-time stay-at-home mom, bearing the primary responsibility for raising Kenny and his younger sister. Kenny fondly remembers being allowed to play outside with all the other kids in the neighborhood, with his mother’s only instructions being to be home by 5:00 p.m. on school nights and by the time the streetlights came on in the summer. For a kid, it was small town living at its best.

High school was not as fun. Kenny did not enjoy his classwork at all—so much so that one day he walked out the door of Badger High School in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, and decided not to go back. Once out the door, he wasn’t sure what he was going to do. He didn’t have a driver’s license or a car—all he knew was that anything had to be better than wasting his time in school. An opportunity arose when an older cousin told him that a factory in nearby Richmond, Illinois, was hiring. Kenny applied, stating on the application he was eighteen, despite being not quite seventeen at the time. Much to Kenny’s surprise, he got the job and started working as a die caster, just like his father.

Kenny was a hard worker, so he did well at the factory. After a little over a year, though, he started having regrets for having quit high school. Still without a driver’s license, Kenny enlisted a friend to take him to Badger High School and he made his way to the principal’s office. The principal was surprised to see Kenny and even more surprised when Kenny asked if he could come back to school to earn his diploma. The principal told Kenny it would take three years, or two years if he worked really hard. Kenny replied that he was already eighteen, so the two-year option was his only real choice. Kenny went on to graduate from Badger High School on June 6, 1969, exactly one month after his twentieth birthday.

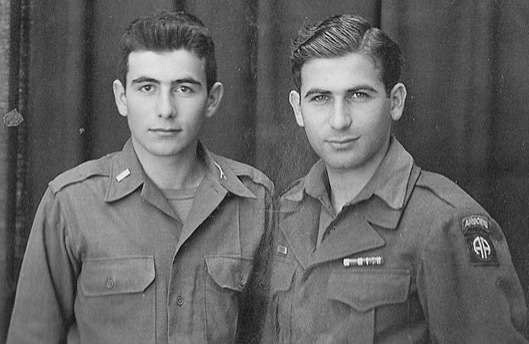

Kenny and another soldier in Vietnam

Kenny and another soldier in VietnamAt the end of 1969, the inevitable happened—Kenny was drafted. He reported to the Military Entrance Processing Station in Milwaukee, together with all of the other local draftees. He was given a physical exam, signed some paperwork, and was sworn-in on active duty. From there, he and the other draftees destined for the Army boarded a plane en route to Basic Training, or “boot camp”, at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Although they arrived in early December, their formal Basic Training was not scheduled to begin until the full complement of draftees reported in January. In the interim, they trained informally for the two or three weeks preceding the holidays. They were even permitted to take leave and go home for Christmas. Once they returned, the Army’s intense eight-week Basic Training program began.

Kenny liked boot camp because of the way the Army transformed his group of undisciplined draftees from around the country into a cohesive platoon of soldiers. The reason behind the transformation was Drill Sergeant West. Built like a fireplug and a veteran of the war in Vietnam, he wasn’t someone to mess with. Kenny considered him tough but fair, and he inspired Kenny’s platoon to excel. One memory that stands out for Kenny was standing in the front row during weapons inspections. When Drill Sergeant West walked down the row, each trainee presented their weapon to the sergeant, who would inspect it and throw it back to the recruit. Kenny said Sergeant West always gave him a little signal, like a slight nod or wink before he threw the weapon back so Kenny would be prepared to catch it. As a direct result of Drill Sergeant West’s leadership and example, Kenny’s platoon was selected as the Honor Platoon for the Basic Training graduation parade.

After completing Basic Training, Kenny wanted to attend “Jump School” to become an Army paratrooper. He instead received orders to attend supply clerk and warehouse management school at Fort Polk, Louisiana—the same place his father had trained during World War II. Kenny completed his training in April 1970 and received orders to report for duty in the Republic of South Vietnam. His orders did not assign him to a specific unit. Because he was a replacement soldier, he would not learn his specific assignment until he arrived in Vietnam. So, without knowing what the future had in store for him, Kenny took eighteen days of leave at home in Genoa City before reporting to the Oakland Army Terminal in California to wait for a flight to take him off to war.

Once at the Oakland Army Terminal, now Private Kenny Esmond had to wait along with all of the other soldiers for their names to appear on a roster indicating they had been manifested on a particular flight. When Kenny and the other men on his flight heard their names called, they picked up their gear and marched to a big metal building where they were locked down until it was time to board. The building remained lit twenty-four hours a day so the men could be closely monitored in case anyone attempted to leave. Other than calling home on the building’s phones to say goodbye to loved ones, there was nothing to do but wait.

Once Kenny finally boarded his flight, he began the twenty-two hour trek to South Vietnam. The plane made several refueling stops along the way, including Hawaii, Wake Island, and Japan, before it finally arrived in Vietnam on May 12, 1970. Kenny was initially assigned to the Headquarters Company of the 101st Airborne Division and was transferred to Camp Evans for training. At Camp Evans, which was located sixteen miles northwest of Hue City—the scene of intense fighting during the 1968 Tet Offensive and a North Vietnamese massacre of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians—Kenny learned to conduct jungle patrols, do river crossings, and defend positions in this new, hostile environment.

Kenny with his rifle in Vietnam

Kenny with his rifle in VietnamAfter almost two weeks of jungle school, Kenny reported to his permanent assignment at the U.S. base at Phu Bai, located eight miles southeast of Hue City on Highway 1, a coastal highway that ran the entire length of South Vietnam. Kenny was assigned to the 1st Battalion of the 502nd Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. When he reported to his sergeant, the sergeant asked Kenny what he knew how to do. Kenny told him his military occupational specialty, or “MOS”, was supply clerk and warehouse management. The sergeant said he wanted Kenny to work in the battalion ammo dump, but he didn’t need people there now. In the interim, he sent Kenny to Fire Base Bastogne—named after the famed defense of the City of Bastogne, France, by the 101st Airborne Division during the Battle of the Bulge—to serve as part of the defensive force protecting the artillery batteries operating there.

Fire Base Bastogne was located about twenty miles southwest of Hue City and was home to several artillery batteries firing 105-millimeter, 155-millimeter, and 8-inch shells. Kenny’s job was to man the base’s defensive bunkers and repair any damaged concertina wire strung around the base to protect it from enemy attacks. One reason for the frequent repairs to the concertina wire was the nightly “mad minutes”, when the base defenders opened up with all of their weapons, firing into the dark all around the base to interrupt the enemy in the event they were assembling for an attack or trying to infiltrate the base perimeter. While the mad minutes were effective in disrupting any would be North Vietnamese attackers, they also often damaged the concertina wire defenses, so Kenny and others had to check and make repairs to the wire every day.

After a brief stint at Fire Base Bastogne, Kenny returned to Phu Bai where he continued on bunker and repair duty. Defensive bunkers were built at intervals around the entire perimeter of the base. Each bunker was about eight feet square with sandbag walls and a plywood and sandbag roof. The bunkers had an opening in the front facing the perimeter and an opening in the back allowing entry and exit while shielded from enemy fire. During the day, the bunkers were manned by a single soldier. At night, four soldiers stood guard at each bunker, two outside in fighting positions while the other two slept inside in two-hour shifts. Kenny had nighttime guard duty every other night, while during the day he worked his other military responsibilities.

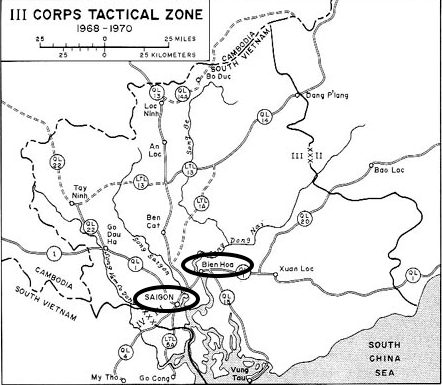

Hue City and Phu Bai in South Vietnam, Source: U.S. Government

Hue City and Phu Bai in South Vietnam, Source: U.S. GovernmentOn Kenny’s first night of guard duty at a bunker on the perimeter of Phu Bai, he was manning an M60 machine gun in a fighting position out in front of the bunker when he heard a sound he recognized from his training at Camp Evans. It was the sound of rocket-propelled grenades (“RPGs”) being launched from somewhere out in the darkness. It was common knowledge that the Viet Cong (“VC”) in the area knew the layout of the base’s perimeter defenses, so Kenny was sure they knew where he was. The first RPG hit behind the line of bunkers about one hundred yards to Kenny’s left. Sparks flew thirty-five to forty feet into the pitch black night. A second RPG passed directly over Kenny’s head, again landing behind the bunkers. The enemy continued to launch RPGs, walking them down the line of bunkers, each manned by young defenders like Kenny. Knowing what the results of a direct hit by an RPG would mean, Kenny was terrified. He describes his fear in simple terms: “If you weren’t scared, you weren’t there.”

On another evening when he was standing bunker guard duty, he heard small arms fire opening up further down the bunker line. The word came over the radio that the VC were probing the perimeter and that each bunker team needed to send one man to the area to assist in repulsing the attack. Kenny drew the short straw and started running down the line of bunkers toward the engagement. He was not completely out in the open in that outside the line of bunkers and firing positions, a dirt berm had been constructed to provide cover for those occupying the defensive perimeter. Still, as Kenny ran toward the sound of the gunfire, he remembers praying—not that he would live—but that Jesus would accept his soul. By the time Kenny arrived, the gunfire had subsided and the attack had been repulsed, but it had been a harrowing few minutes. To this day, whenever Kenny hears fireworks on the Fourth of July, it takes him back to Phu Bai, running along the base perimeter alone at night, not knowing what was waiting for him or if he would survive.

The North Vietnamese and the VC weren’t the only ones attacking the bunkers. One night when Kenny and three other soldiers were standing guard in a bunker on the perimeter of Fire Base Bastogne, a King Cobra slithered into the bunker while the men were inside. Kenny described the ensuing melee like a scene from the Three Stooges as they all scrambled to get out of the bunker. When everyone was clear, one of the soldiers killed the invader with his M16, prompting a radio call from the officer-of-the-day asking what was going on. When they told him about the King Cobra, the officer-of-the-day told them they should have killed it with a stick. That was one piece of advice they had no intention of following.

Kenny with the South Vietnamese countryside behind him.

Kenny with the South Vietnamese countryside behind him.Because Kenny was a supply clerk, his daytime duties at Phu Bai initially involved managing the supply records for the uniform inventory in support of the Property Book Officer. After two months, though, he was so bored that he went to the Property Book Officer and said he needed to do something else. Appreciating the initiative, the Property Book Officer sent Kenny across the street to the battalion ammunition (“ammo”) dump to talk to the sergeant in charge. When the sergeant heard Kenny wanted to work in the ammo dump, which supplied small arms ammunition to infantry companies in and around Phu Bai, the sergeant just shook his head and told Kenny to come in and get started.

Kenny’s duties working at the ammo dump were wide and varied. When the inventory of M-16 and 40-caliber ammunition and cratering charges grew low, he would requisition more and ride in a two-and-a-half ton (“deuce and a half”) truck to the main ammo dump on the other side of Phu Bai to pick it up. These trips were dangerous enough because Kenny was riding in a truck filled with ammunition, but on at least one occasion he was fired upon as he passed through a hamlet on this way to pick up the load.

As time passed and Kenny became familiar with all of the ammo dump’s procedures, both of the sergeants who were senior to him “went back to the world”, which meant they returned to the United States. This provided an opportunity for Kenny because he was promoted to sergeant and took over the ammo dump after the two sergeants left.

Once Kenny was in charge, one of his new responsibilities was to travel to the surrounding fire bases to restock their ammunition inventory. To tackle this mission, Kenny heloed out to the fire base, inventoried the ammunition on hand, and radioed back an order to bring the fire base’s ammunition back up to its base load. The next day, a helicopter would fly in with the ammunition. Kenny and other soldiers would unload the ammunition onto an open flatbed vehicle known as a “mule” and drive it to the fire base bunkers to restock their supplies. Kenny would then hitch a ride back to Phu Bai on a logistics helicopter later in the day. Similarly, if units were heading home to the United States as part of the U.S. troop drawdown, Kenny would visit the unit, collect its ammunition, and return it to the battalion ammo dump.

Kenny and his wife, Kathy

Kenny and his wife, KathyAs Kenny neared the end of this one-year tour in Vietnam, he decided to extend in country for two more months to figure out his future. On one hand, he was now a sergeant and had done very well, even having been awarded an Army Commendation Medal for his outstanding work and dedication to duty. That made a career in the Army a real option. On the other hand, he wanted to get home to his family and didn’t want a follow-on assignment in Germany, which was a real possibility. In the end, his family and Genoa City won out. Kenny departed South Vietnam on July 6, 1971. Upon his return to the states, he was honorably discharged at Fort Lewis, Washington. He then went back to Genoa City to pick up life where he had left off.

Once he got back, though, he felt like nobody cared what he had done. Even more hurtful, he felt like people avoided him because he had served in Vietnam. Although he was immensely proud of his wartime service, it wasn’t until a fellow Vietnam veteran shook his hand and told him “Welcome home, brother,” at a Memorial Day ceremony forty years later that he started to feel like he belonged again. At the ceremony, Kenny participated in a talking circle, where every veteran attending was given the microphone and an opportunity to talk. After Kenny spoke, the other veterans hugged him, letting him know his service was valued. The event finally let Kenny reconcile how his service in Vietnam had influenced his life.

Kenny is retired now, having worked in construction ever since his return from Vietnam. He is happily married to Kathy, his wife of thirty years, and living in Genoa City. He’s once again enjoying the benefits of living in small town America, just as he did as a kid.

In addition to the Army Commendation Medal, Kenny was awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star for his outstanding service in Vietnam. He also wanted to be sure the following special message was included in his story: “To all my sisters and brothers who served in the military—Ooorah!”

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Sergeant Kenny L. Esmond, U.S. Army, for his willingness to serve our country during time of war. At just twenty-one years old, he put his life on the line in far off South Vietnam because he believed in our nation and our democracy. We thank him for his dedication to duty and committed service, and wish him fair winds and following seas.

February 10, 2021

Senior Airman Robert Johnson, U.S. Air Force – Duty Above the Arctic Circle

When you enlist in the military, you never know what Uncle Sam has in store for you. In essence, you are giving the military a blank check to write your future for the term of your enlistment and often beyond. Such was the case for Senior Airman Robert Johnson, who joined the Air Force in 1966. Little did he know that a few months later, he would be stationed at the United States’ northernmost military base, just 950 miles from the North Pole. This is Bob’s story.

Bob was raised in upstate New York in the small town of Oakfield, located about forty miles east of Buffalo. His father drove a tanker truck delivering heating oil to homes – a booming business given the harsh Buffalo winters and the heavy snowfalls blowing in from Lake Erie. His father worked his way up from driving a truck to operating several trucks of his own, while Bob’s mother worked at Sylvania in addition to taking care of Bob and his older brother and younger sister. Bob’s father taught Bob and his older brother to love the outdoors and they were avid hunters. Bob got his first shotgun when he was fourteen and one of his fondest memories of growing up was when his father would come home from work and take Bob and his brother hunting in the nearby woods.

Bob spent all of his school years in Oakfield and was active in sports. He took up weight-lifting in high school, ran cross-country, and joined the rifle team. He graduated in the spring of 1963 and enrolled in the University of Louisville in Kentucky in the fall. At the end of three years, though, he’d had enough, realizing college just wasn’t working for him, so he returned home and told his parents he wasn’t going back to school.

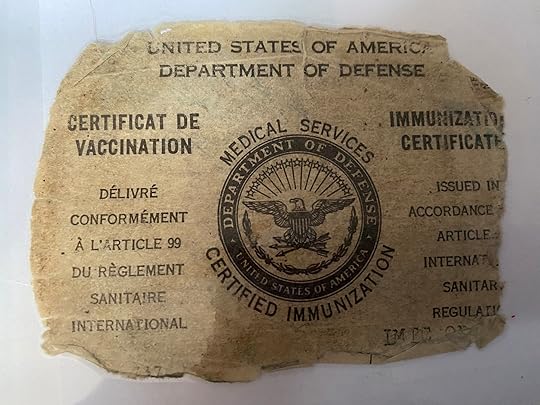

Bob’s original Air Force immunization card

Bob’s original Air Force immunization cardBy now it was the middle of 1966 and President Lyndon B. Johnson was escalating U.S. participation in the Vietnam War. Rather than wait for the draft where his options would be limited, Bob enlisted in the Air Force. After saying goodbye to his parents, he boarded a plane for the first time in his life and flew to San Antonio, Texas, for basic training at Lackland Air Force Base. After eight weeks of basic training, then-Airman Johnson boarded another airplane, this time headed to his technical school at Keesler Air Force Base near Biloxi, Mississippi.

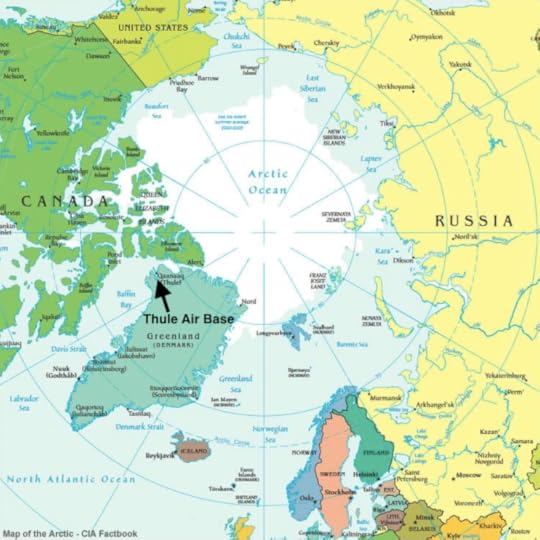

At Keesler, Bob trained to become a radio communicator, which he enjoyed. He spent much of his time in class learning what to do and what not to do while talking on the radio and practiced communications procedures through mock radio transmissions. He also enjoyed being assigned so near the Gulf Coast, with miles of sandy beaches just a short drive away. He spent time at the beach whenever his liberty schedule allowed, as well as in the city of Biloxi. His time in the sun-drenched Gulf of Mexico was short-lived, because near the time of graduation he learned that his first assignment would be at Thule Air Base, doing “radio communications at the top of the world.”

After graduation in 1967, Bob started on the long flight to Thule. His plane stopped in Canada to refuel and then continued to the U.S. air base located 750 miles above the Arctic Circle on the Danish island of Greenland. The strategically located base, just hours from the Soviet Union’s arctic coast, played a significant air defense role during the Cold War, at times hosting strategic bombers poised to attack the Soviet Union and fighter-interceptors whose mission was to prevent Soviet bombers from reaching the United States and Canada. Just as important, the base’s sophisticated radars were intended to provide the United States and its NATO allies an early warning if the Soviet Union were to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads towards the western alliance. Not that there was anything that could be done to stop the missiles once inbound, but Thule’s early warning was essential in making sure the Soviets knew there would be a response in kind.

After graduation in 1967, Bob started on the long flight to Thule. His plane stopped in Canada to refuel and then continued to the U.S. air base located 750 miles above the Arctic Circle on the Danish island of Greenland. The strategically located base, just hours from the Soviet Union’s arctic coast, played a significant air defense role during the Cold War, at times hosting strategic bombers poised to attack the Soviet Union and fighter-interceptors whose mission was to prevent Soviet bombers from reaching the United States and Canada. Just as important, the base’s sophisticated radars were intended to provide the United States and its NATO allies an early warning if the Soviet Union were to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads towards the western alliance. Not that there was anything that could be done to stop the missiles once inbound, but Thule’s early warning was essential in making sure the Soviets knew there would be a response in kind.

It was in this Cold War setting that Bob found himself. He was welcomed by members of his unit as soon as he disembarked the plane, and they began immediately briefing him on what he needed to do to survive in the harsh arctic environment. They issued him cold weather clothing and warned him that during the winter it would be nothing for the temperature to drop to -40 degrees Fahrenheit, with the average winter temperature hovering at a frigid -20 degrees. On top of that, when storms would blow through, wind speeds could exceed 100 miles per hour, making the wind chill unbearable. As if that wasn’t enough, as far north of the Arctic Circle as they were, it remained dark 24 hours a day from November through February. Bob understood quickly that not taking the warnings seriously could prove deadly.

As a radio operator at Thule, Bob communicated with inbound and outbound military aircraft. He passed weather information to the aircrews and let them know what the landing conditions were. He also found a way to “patch” the radio broadcast of the 1967 World Series between the St. Louis Cardinals and the Boston Red Sox through to the U.S. planes flying for hours on end above the Arctic. One plane’s aircrew even called in and asked Bob to send them the World Series, too, once they heard it was something he could do. Unfortunately, Bob’s superiors didn’t like the idea and they shut down Bob’s baseball broadcasts once they became aware of them.

An aerial view of Thule Air Base.

An aerial view of Thule Air Base.Although the landscape surrounding Thule was desolate, Bob found it strangely beautiful. In fact, he describes his time there as one of those rare, wonderful experiences when you get to meet Mother Nature. During the summer months when the temperature would rise to about 40 degrees Fahrenheit and it would be light 24 hours a day, Bob and his friends would explore the area around the base on hiking trails, or just sit outside with a good book and enjoy the sun. Sometimes they would even see a ship pull into the harbor to drop off supplies, although much of what they needed came in by air.

Year round, when they weren’t on duty, they worked out at the barracks gym or visited their friends and talked in their rooms. Bob kept snacks and non-alcoholic drinks in his room all the time, so it was common for friends to stop by and chat. In the evening, they could go to the enlisted club for a meal or some entertainment and a drink or two, before hunkering down in their barracks for the night. Not even their barracks were safe enough when big storms hit the base and they had to evacuate to more secure buildings designed to withstand the strong winds and bone-chilling cold.

On one occasion when a severe storm set in, everyone was restricted to quarters and the barracks staff began taking a roll call. Bob was missing. They began to search the barracks and were getting ready to call for a search outside when they found him visiting with African American Airmen he had become friends with. Amid the racial tensions of the 1960’s, this demonstrated in a simple way Bob and his friends’ commitment to treat each other with dignity and respect and to help break down societal barriers. Of all of the Air Force stories Bob has told his children and grandchildren over the years, this one had the greatest impact because of the life lesson it taught. In fact, Bob’s children and grandchildren felt so strongly about it that they specifically asked him to include it as part of his Air Force story.

Although Bob loved his assignment at Thule, when he got the chance to take leave, he went to the opposite weather extreme. Taking advantage of discount air fares available to military members and the money he’d saved in Greenland, he visited both Hawaii and Florida in an effort to thaw out from his deep freeze in the arctic. These vacations also helped break his assignment into more tolerable segments.

Bob’s tour at Thule lasted one year, meaning he still owed the Air Force another eighteen months after leaving Thule. He was assigned to follow-on duty at Chanute Air Force Base in east-central Illinois. There he spent the rest of his enlistment typing base communications and performing other administrative functions for the Chanute military community.

After completing his three-year commitment to the Air Force, Bob was honorably discharged as a Senior Airman in 1969. His first order of business was to find a job, which he did in the nearby community of Champaign, Illinois, working for Kraft Foods. He also met the love of his life, Linda, and they were married in 1978, bought a home, and raised four children. Bob stayed at Kraft until he retired in 2000, having worked his way up from an entry-level position to an Assistant Supervisor, but his work career was not quite over just yet.

It turns out that Linda loved to ski and she got Bob hooked. So much so that Bob took a leadership role in the local ski club, which chartered buses to go on ski trips to Northern Michigan, West Virginia, and the Rocky Mountains. On one such trip to Snowshoe Mountain after Bob retired from Kraft, Bob was hired to take charge of Guest Services, so he and Linda moved to West Virginia.

It turns out that Linda loved to ski and she got Bob hooked. So much so that Bob took a leadership role in the local ski club, which chartered buses to go on ski trips to Northern Michigan, West Virginia, and the Rocky Mountains. On one such trip to Snowshoe Mountain after Bob retired from Kraft, Bob was hired to take charge of Guest Services, so he and Linda moved to West Virginia.

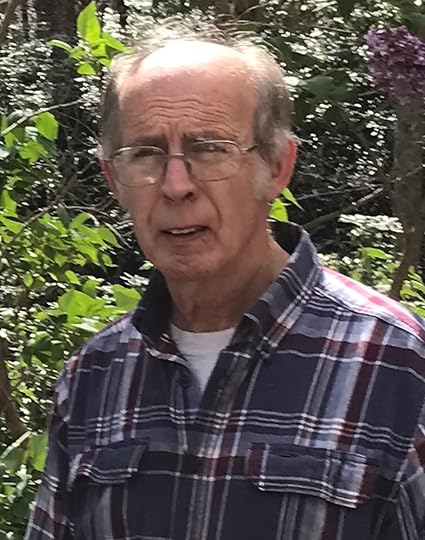

Bob and Linda are now fully retired and living in North Carolina, where they are closer to their seven grandchildren and four great grandchildren. As Bob looks back over his time in the Air Force, he is proud of his service and believes it gave him opportunities and training he never would have had without serving. His experience also gave him the confidence to succeed in his follow-on jobs, as well as to work in a technical field.

Voices to Veterans salutes Bob for his service and his willingness to go to the ends of the earth to defend our freedom during the height of the Cold War. He saw his assignment to the isolated American air base not only as his duty, but also as an opportunity he had to be thankful for. We, too, are thankful for Bob’s service, and wish him fair winds and following seas.

January 20, 2021

Master Chief Legalman David S. Leafer, U.S. Navy (Retired) – The Recruiting Posters Were Right

Everyone has heard the old Navy recruiting slogan “Join the Navy – See the world.” It takes a special person, though, to follow through and visit a recruiter’s office, sign an enlistment contract, and put the slogan to the test. Master Chief Legalman David S. Leafer, U.S. Navy (Retired), did just that and found the Navy to be true to its word. Although it meant working long days at sea for months on end, a wartime deployment to the Red Sea onboard an aircraft carrier launching strikes deep into Iraq, and countless hours working on legal issues for the fleet, the opportunities Dave’s Navy career brought him exceeded his wildest dreams. He even got to meet the President and First Lady because he’d proven himself to be a bold and effective leader. This is his story.

Dave was born in 1961 and raised in Peabody, Massachusetts, a small town located twelve miles north of Boston. His dad was an electrical engineer and Korean War veteran, having served in the Air Force as a radar operator. His mom was an accountant for various businesses in the Boston area. Dave and his younger sister, Jodi, went through all levels of the Peabody school system, with Dave graduating from Peabody Veterans Memorial High School in May 1979.

Although Dave was a good athlete, at 135 pounds, he found greater success working after school rather than playing a sport but rarely getting into a game. A job he particularly enjoyed was working as a “lot boy” for a local Dodge dealership. On nights when it might snow, the dealership let him take a truck home from work even though he was a relatively new driver. The next morning, he would get up at 4:00 a.m., drive the truck to the dealership and plow the lot before heading off to school. He also worked at Kmart and between the two jobs, made pretty good money. So good, in fact, that after he graduated from high school, he continued to work for a year at the dealership, hauling in $12/hour, which wasn’t bad for an eighteen-year-old kid in those days.

Master Chief Leafer in Bahrain

Master Chief Leafer in BahrainBy December 1980, Dave was bored. He had some friends who’d joined the military and wrote him from Hawaii and Japan, so he decided he needed to travel, too. He and a friend visited the local Armed Forces Recruiting Center, which had recruiters from all four services. He knew he didn’t want to be a Marine, but was otherwise open to the other services. His dad had been Air Force, but the Air Force recruiter was out for lunch, taking them off the table. Next up was the Navy recruiter, who gave Dave his full spiel. Dave was so impressed, he came back the next day and enlisted in the Navy.

The program Dave enlisted in was called the Delayed Entry Program. That meant he had to report to the Armed Forces Examining & Entrance Station, or AFEES, to begin his enlistment in February 1981. However, his report date was further delayed until June 8, 1981. When he and others with the same report date arrived, everyone was very nice to them. They were asked if they still wanted to enlist in the Navy and, after they said they did, they were sworn in as official U.S. Navy recruits. Dave then had one last opportunity to say goodbye to his parents, his grandparents, and his girlfriend, who had all come to see him off. Dave and the other Navy recruits were then transported to Boston’s Logan International Airport for the two-hour flight to Chicago and Basic Training at Naval Station Great Lakes.

The recruits arrived in Chicago around midnight and that’s when everyone stopped being nice. The Navy sailors that met the new recruits at the airport started yelling at them and never stopped. Dave, who hadn’t been yelled at before by anyone other than his parents, thought “what have I gotten myself into?”

Once at Great Lakes, each recruit was issued a blanket and told to get some sleep on the bunk beds in their assigned berthing areas. The next morning began bright and early and the yelling continued. Dave wanted to tell them to “go to hell”, but wisely held back. Others who failed to show the same restraint were separated from the group and not seen again.

The Chief Petty Officer responsible for Dave’s company of recruits was a Gunner’s Mate from the fleet who was “mean as hell.” He had a beard and Dave and the other recruits were afraid of him, but he taught them a lot about how to survive and succeed in the Navy. Years later, Dave ran across the Chief and learned he wasn’t mean at all—it was the role he played for the new recruits. Life on a ship could be unforgiving, so the new recruits had to learn to respect authority, follow orders, and function as a team. In that regard, Dave believed the Chief prepared him well.

Dave liked boot camp, except for peeling potatoes and scrubbing pots and pans. His duties and daily routine taught him discipline. Even the little things like folding clothes in the required way or making his bed gained him unexpected confidence in his abilities. He loved learning about Navy history and memorizing the plethora of acronyms the Navy uses. He also enjoyed the challenges and was appointed as an Assistant Recruit Chief Petty Officer (ARPOC), one of the Recruit Division Commander’s (RDC) primary recruit assistants, responsible for maintaining the division in good order. When the RDC assigned him an errand like getting the mail or running to pick up documents or other miscellaneous items, Dave seized the opportunity and used it to occasionally grab a cup of coffee, escape his recruit duties, and be stress free for a while.

Dave graduated from boot camp as a Seaman Recruit (E-1) in September 1981 with orders to report to the USS Sierra (AD 18), a World War II era destroyer tender commissioned in March 1944 and homeported in Charleston, South Carolina. The Sierra was essentially a floating machine shop that deployed with Navy battle groups and provided repair services for the battle group ships so they could continue their missions instead of having to return to shipyards to allow the work to be done. On one occasion, after assisting engine room personnel fix the periscope of the nuclear powered submarine USS Jacksonville, which was operating in the vicinity of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, the submarine’s skipper allowed some of the working party to get underway with the sub to make sure the sub’s systems were in order. Dave was excited and all was going well until he learned the submarine was submerged. For some reason he does not understand even now, Dave did not move from the area where he was sitting for what seemed like an eternity. Although he had offers to do so again during his career, he never took another ride on a submarine.

During a leave period in 1983 while Dave was assigned to Sierra, he drove home to visit his parents in Peabody. As he was talking to his parents and his girlfriend at his parent’s house just prior to heading back to Charleston, he heard screams outside and saw smoke. He ran through snow covered back yards to his neighbor’s house and saw a car engulfed in flames with a man still inside. Without thinking about what he was doing, he ran to the car, pulled the man out, and dragged him to safety. The flames were so hot, the man’s glasses were melted to his head and ears. Just after Dave got the man to safety, the car was engulfed by fire and exploded.

Dave’s hands were burned and he went into what he can only describe as shock. When the police and the fire department arrived, he saw someone point to him and say, “he’s the one who saved the man’s life.” After that, Dave only remembers walking back to his parent’s house while his parents were outside watching what was going on and, without saying goodbye, jumping into his car to drive back to Charleston. He stopped at a Sunoco station to get some wiper fluid and gas and suddenly found himself surrounded by State Troopers. He was taken to Bethesda Naval Hospital just outside Washington, DC, where he was admitted and treated for burns on his hands, smoke inhalation, and fragments in his eyes from when the car exploded. He was subsequently awarded the Navy Commendation medal for saving the man’s life.

Dave returned to work and deployed with USS Sierra to the Indian Ocean. He also made other shorter deployments, allowing him to tour some amazing countries in the Mediterranean. Travel like this was what he had signed up for. He detached from USS Sierra in June 1984 and reported to Cruiser-Destroyer Group TWO, a multi-ship battle group commanded by an admiral whose flagship was the aircraft carrier USS Independence (CV 62). Dave enjoyed his time on the aircraft carrier so much that he really wanted to stay in the Navy. The assignment also led to a decision that changed the direction of his Navy career.

Dave reported to his next assignment at Naval Station Newport, Rhode Island, in June 1985. Newport was an ideal location because it was close to his parents and friends in case the Navy did not work out. While at Naval Station Newport, Dave was selected for promotion to Third Class Petty Officer (E-4). He was also sent to the Naval Justice School, located on the Naval Station, to assist with a legal investigation. At the school, where Navy attorneys known as Judge Advocates or “JAGs” and Navy paralegals, known as Legalmen, trained, Dave was introduced to the Navy’s legal system. He was immediately drawn to the Legalman’s responsibilities, working military justice issues and investigations and assisting JAGs handle courts-martial and a myriad of other legal responsibilities. He completed a conversion package to apply to become a Legalman and was selected to attend the Naval Justice School in 1987. He graduated from the Legalman course in December 1987 and was promoted to Legalman Second Class (E-5).

Dave’s first assignment as a new Legalman was at the prestigious Naval War College, which was also located in Newport. There he worked in an office with two senior people – a JAG Captain (equivalent to an Army Colonel) and a civilian professor of international law – supporting their efforts as instructors of courses for senior U.S. and international Navy and Marine Corps officers. Because the military justice workload at the War College was low, Dave seized on the opportunity to observe war games and listen in on strategy discussions. The insight he gained into Navy operations served him well throughout the rest of his Navy career.

While at the Naval War College, Dave passed the exam for promotion to Petty Officer First Class (E-6) and was “frocked”, which meant he was allowed to wear his new rank but would not receive the increased pay until it came his time to officially promote. The frocking ceremony was a big deal – hundreds of people came, including his parents. And now that he wore the uniform of a Petty Officer First Class, he was entitled to the rank’s privileges, including going to the head of the line at the galley for chow and at medical for sick call. He was also assigned a reserved front row parking spot. Needless to say, promotion to First Class is a significant milestone in a Sailor’s career.

Seven months later, the Admiral commanding the War College summoned Dave to his office. The Admiral told Dave the Bureau of Naval Personnel had made a mistake and that through no fault of Dave’s, he had not been eligible to take the First Class Petty Officer exam and therefore the Bureau was taking away his eligibility for promotion. In practical terms, that meant Dave had to remove his First Class Petty Officer stripe and revert to a Petty Officer Second Class. Moreover, he would have to take the exam again, even though he had passed it before. The Admiral weighed in personally with the Bureau to prevent it from happening, but the Bureau was adamant – Dave had to revert to Second Class.

The situation angered Dave, but he was humbled by how the Admiral went to bat for him. He also got good advice from a Senior Chief Legalman (E-8) who told him he’d been through a similar situation. He told Dave the best way to deal with it was to buckle down and show everyone he deserved to be a First Class. Dave did just that. He worked hard, took the next exam and passed it, and officially promoted to Petty Officer First Class at his next duty station in March 1991.

USS Saratoga (Source: U.S. Navy)

USS Saratoga (Source: U.S. Navy)Dave detached from the Naval War College in March 1990 and reported in April to the legal office onboard the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV 60), which was homeported in Mayport, Florida. Just four months later, he was underway with the ship on a wartime deployment to the Red Sea in support of Operation Desert Storm after Iraq invaded Kuwait. The ship’s squadrons delivered tons of ordnance to targets in Iraq and Kuwait but lost three aircraft in the process. Before participating in Desert Storm, the ship also lost 21 enlisted sailors just three days before Christmas when a liberty boat returning crewmembers to the ship capsized in rough seas in the port of Haifa, Israel. Dave still commemorates the loss of his shipmates every year on the anniversary of the accident.

One high point of Dave’s tour on Saratoga was talking to then-Captain Joseph S. Mobley, the captain of the ship. Because Dave put together the disciplinary cases to be adjudicated by Captain Mobley, he got the chance to interact with him regularly on the bridge, something most enlisted sailors on board would never get to do. What made this particularly interesting was Captain Mobley had flown combat missions as a bombardier-navigator on A6A Intruders during the Vietnam War, was shot down in 1968, and was held as a prisoner of war until his release on March 14, 1973. Anytime Dave felt like he was having a bad day, he thought of what Captain Mobley had gone through at the hands of the North Vietnamese and suddenly his troubles didn’t seem so bad after all. One other high point of the tour was Dave earned his Enlisted Aviation Warfare pin, which meant he had demonstrated sufficient knowledge and skills with naval aviation operations to wear the insignia. Earning a warfare pin was essential to Dave’s career and continued advancement.

After returning to Saratoga’s homeport in Mayport, Dave transferred to the Navy Legal Service Office in Mayport in August 1992. There he assisted JAGs prosecute and defend courts-martial and helped provide legal assistance to Sailors assigned to the many ships and helicopter squadrons calling Mayport home. Just seven months later, he was selected to report to the Admiral commanding the multi-ship USS George Washington (CVN 73) Battle Group. Dave was a member of the Admiral’s staff and worked directly for the Battle Group JAG, who was the attorney responsible for advising the Admiral on international law, the law relating to naval operations, the rules of engagement for the use of military force, and military justice issues. The JAGs Dave worked for, then-Lieutenant Commander Gregg Cervi and Lieutenant Commander George Reilly, treated Dave as a teammate and gave him work to do that had historically been reserved for JAGs. Dave loved the work and excelled. He was able to assist and observe the JAGs briefing the Battle Group on the rules of engagement, as well as provide direct support on investigations and special events.

The most memorable event occurred during the Battle Group’s deployment in 1994, when the USS George Washington participated in the 50th anniversary commemoration of the D-Day landing at Normandy. Numerous dignitaries visited the ship, including President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton, the Vice President, and the Secretary of Defense. One late afternoon when the President was on board, a Marine came down the passageway telling everyone to clear the way for the President’s party. Dave and a group of other sailors were in their office and stood with the door open to watch the President walk by. As the party approached, Dave got up his nerve and asked White House Press Secretary Dee Dee Myers if they could get a picture with the President. Ms. Myers said no because they were on their way to dinner, but First Lady Hillary Clinton heard Dave’s request and said it was a great idea. The result was everyone in the office had their picture taken with the President and First Lady.

After the dignitaries left, the Admiral held an award ceremony recognizing all of the work everyone had done in helping coordinate the visits by the many dignitaries. He was all smiles until he called out Dave’s name. Dave, recalling the last time an Admiral looked somber and gave him bad news, feared he was about to be chewed out for asking the President’s party for pictures. Instead, the Admiral praised him for all he had done and said his action to get his shipmates a picture with the President and Mrs. Clinton epitomized what it means to be a Navy leader.

Dave’s efforts coordinating with the Secret Service and the White House Communications staff earned him the trust of the Admiral and the Battle Group JAG, and a plum temporary assignment in New York City after the Battle Group returned to Norfolk in November 1994. Each year in the spring, New York City opens its doors to the Navy during Fleet Week, when ships and Sailors visit the City to promote the Navy and its mission. In early 1995, Dave was sent to New York City as the Officer-in-Charge of an advanced party, arranging things like transportation and catering and planning for a wide range of events. He worked closely with the Mayor’s personal assistant during his entire time in New York. During one such event, Dave was wearing his summer white uniform sitting on a couch at the Mayor’s mansion talking to people when actor Kevin Kline dropped a Swedish meatball that landed on Dave’s uniform. The Mayor’s personal assistant quickly ushered Dave into a bedroom and told him to take off his uniform so it could be cleaned. While Dave was sitting on the bed in his skivvies waiting for his uniform, the Mayor and his wife walked in and wanted to know what was going on. Dave and the Mayor’s personal assistant explained the situation and a few minutes later, his uniform re-appeared, cleaned and pressed and inspection ready. Then it was back to the event as if the incident had never happened.

In addition to earning his Enlisted Surface Warfare pin while on board George Washington, Dave earned many accolades for his Battle Group tour, including Battle Group Sailor of the Year and the Navy Judge Advocate (the three-star JAG Admiral responsible for the Navy JAG Corps and all Legalmen) Sailor of the Quarter. But by January 1996, it was time to move on to Dave’s next assignment at the Trial Service Office in Mayport, Florida, where he helped Navy JAGs prosecute courts-martial and assisted Navy commands with their military justice needs. During this tour, Dave was selected for Chief Petty Officer (E-7), the most prestigious promotion for an enlisted sailor during the course of a Navy career.

At the Trial Service Office, Dave learned about leadership and taking care of sailors firsthand, and was selected as a Command Chief. He also attended a Heisman Trophy event at the Sawgrass Country Club in nearby Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, where he received a football autographed by numerous Heisman Trophy winners. While there, he met and spoke with legendary Yankees player and coach Yogi Berra, who added his autograph to the football despite learning Dave was a die-hard Red Sox fan.

Dave transferred to the legal office at Naval Air Station Jacksonville in September 2000. He was selected for promotion to Senior Chief Petty Officer (E-8), the second highest enlisted rank in the Navy, in September 2002. He then transferred to the Region Legal Service Office, Yokosuka, located on a U.S. Navy base about thirty miles south of Tokyo. The Region Legal Service Office prosecuted courts-martial and advised the forward deployed ships and squadrons of the U.S. Seventh Fleet on a broad range of legal matters. In addition to supporting those efforts and assisting his Commanding Officer, and as the senior Legalman in the Western Pacific, Dave traveled to wherever Legalmen were assigned – Guam, Hawaii, Thailand, the Philippines, and other bases in Japan – to ensure they had the support they needed to serve the legal needs of their commands. Dave’s area of responsibility included 45 regional Legalmen. During the visits, he listened to his sailors’ issues, helped address their requirements, and mentored them professionally.

Dave transferred to the legal office at Naval Air Station Jacksonville in September 2000. He was selected for promotion to Senior Chief Petty Officer (E-8), the second highest enlisted rank in the Navy, in September 2002. He then transferred to the Region Legal Service Office, Yokosuka, located on a U.S. Navy base about thirty miles south of Tokyo. The Region Legal Service Office prosecuted courts-martial and advised the forward deployed ships and squadrons of the U.S. Seventh Fleet on a broad range of legal matters. In addition to supporting those efforts and assisting his Commanding Officer, and as the senior Legalman in the Western Pacific, Dave traveled to wherever Legalmen were assigned – Guam, Hawaii, Thailand, the Philippines, and other bases in Japan – to ensure they had the support they needed to serve the legal needs of their commands. Dave’s area of responsibility included 45 regional Legalmen. During the visits, he listened to his sailors’ issues, helped address their requirements, and mentored them professionally.

On one such trip when he was traveling to Sasebo, Japan, with his commanding officer, the commercial jet they were flying in started zooming down the runway to take off when it struck a flock of birds. Dave heard a BAM and the plane skidded to a stop at the end of the runway. When he and the other passengers evacuated the aircraft, they saw the plane’s nose and front wheel hanging over the break wall at the end of the runway. Had the jet gone just a few more feet, it would have plunged into the water. Once inside the airport, Dave and his boss downed a few drinks and discussed their close call. Seven hours later, the same plane – now with a new engine – was back at the gate and ready to board. Had it not been for the drinks, Dave wasn’t sure he would have boarded the plane.

In April 2005, Dave was selected for Master Chief Petty Officer (E-9), the Navy’s highest enlisted rank. One month later, he left Japan and headed for Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, the largest Navy base in the world. There he was assigned to a detachment of the Naval Justice School, but he actually served as the Command Master Chief for the entire Naval Justice School. This meant he had to travel routinely to the Justice School in Newport, Rhode Island, to work on programs designed to improve the proficiency and versatility of Legalmen. One of the initiatives he is most proud of his contributions to involved Legalmen training at the Naval Justice School and enrolling concurrently at Roger Williams University to earn an Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree in paralegal studies. Dave also taught at career development courses for senior enlisted leaders in Norfolk and around the fleet, focusing on leadership, good order and discipline, and taking care of the legal needs of sailors. He attained his Master Training Specialist certification during this tour.

Dave and Charlena Leafer

Dave and Charlena LeaferIn May of 2008, Dave transferred one last time to serve as the Command Master Chief for Region Legal Service Office, Norfolk, the largest legal office in the Navy. He served as a trusted advisor to the commanding officer and provided leadership and mentoring for the command’s and the region’s ninety plus enlisted sailors. Dave retired from the Navy out of this position in June 2011, capping off a stellar thirty-year Navy career.

Dave has continued to serve the Navy as the civilian legal officer for the Navy Computer and Telecommunications Master Station in Norfolk, Virginia. His position allows him to stay in touch with the people he served with over his long career, as many of his best friends have similarly continued their association with the Navy after retiring.

With his travel significantly reduced since leaving active duty, Dave spends his free time enjoying life with his wife, Charlena, his three children, and his grandson. Although he’s battled some serious health challenges, he’s not let them slow him down or curb his enthusiasm. When he meets young people looking for adventure, travel, a way to pay for education, or just trying to find direction and discipline in their lives, he tells them to give the Navy a try and promises they won’t be disappointed. He adds with a smile, if he can make it, anyone can.

Voices to Veterans is proud to salute Master Chief Legalman David S. Leafer, U.S. Navy (Retired), for his many years of outstanding service to our nation, including during a wartime deployment on board USS Saratoga in Operation Desert Storm. Throughout his career, he not only provided outstanding legal services to sailors and the many commands he served in the fleet, but he also led and mentored countless Legalmen to help them be successful. For all he has done, we wish him fair winds and following seas.

November 11, 2020

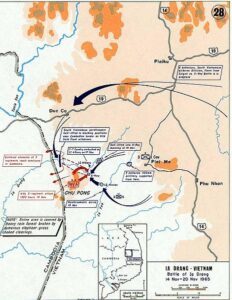

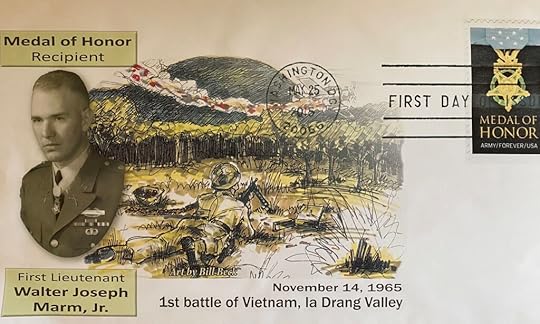

Colonel Walter Joseph Marm, Jr., U.S. Army (Retired) – Battle of Ia Drang Medal of Honor Recipient

Every Soldier, Sailor, Airman and Marine wonders when the time comes, will they have the strength and courage to do their duty, even if it might cost them their life. Colonel Walter “Joe” Marm came face-to-face with that question as a young Army second lieutenant on November 14, 1965, in the elephant grass of the Ia Drang Valley in South Vietnam. For his answer, Joe Marm was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, America’s highest military decoration for valor in combat. This is his story.

Joe was born and raised in Washington County, Pennsylvania, about twenty-five miles southwest of Pittsburgh. His dad was a Pennsylvania State Policeman who spent his career in Washington County, while his mom stayed at home taking care of the family. Joe started school in a two-room schoolhouse where one teacher taught grades one through three while a second teacher taught grades four through six. After finishing second grade, Joe transferred to the Immaculate Conception parochial school in Washington County. There, the Irish nuns of the Mercy Order laid the foundation of a solid education that would carry Joe into college.

During his high school years, Joe was a member of the Frazier-Simplex Rifle Club. Shooting was a penchant he learned from his father, who was an expert pistol marksman competing for the Pennsylvania State Police. Joe used to help his father load cartridges for his father’s pistol. To participate in competitions with the club, Joe purchased a Winchester Model 52 target rifle and became quite proficient. He was also active in Boy Scouts until his troop disbanded, but not before he earned the rank of Life Scout and became a member of the Order of the Arrow. He credits the skills he learned in Boy Scouts and on the rifle team with preparing him well for the military.

Joe graduated from high school in 1959 and enrolled at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh to study pharmacy. His dad helped him get a construction job so he could earn money for school. He worked for bricklayers, loading up to twenty bricks on a “hod carrier”, which he hoisted onto his shoulder and then carried the bricks to the bricklayers who needed them. This was grueling work, as a fully-loaded hod carrier weighed about one-hundred pounds – even more when Joe carried mortar instead of bricks. One summer, they had Joe dig ditches for underground pipes feeding into the construction sites. His construction job paid $2.00/hour, a huge sum in the early 1960s. He earned even more one year working for the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company, sweeping floors and picking up trash in a steel mill.