Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 42

February 1, 2019

Do This Every Day

It was 1990-something.

I was working in a small mom-and-pop publishing house just down I95 from Health Communications, the publisher of Chicken Soup for the Soul.

My boss wanted a series just like that.

Think of all the possibilities. Chicken Soup for the Cat Lover’s Soul. Chicken Soup for the 12 Year Old’s Soul. Chicken Soup for the Chicken Soup Hater’s Soul. Chicken Soup for everyone!

I can’t remember if my boss told me this or if I read it in a magazine or heard it on the radio, but around that time, either Jack Canfield or Mark Victor Hansen said something about doing an interview a day, or scheduling something every day—or just doing something every day. (Murky, I know . . . Getting old is a hateful business).

Point was: Do something every day.

Stuck with me.

Back to 2019. I watched Amanda Seales’ “I Be Knowin’” special on HBO last weekend.

Part of her routine hits on how hard it is to go out in the evenings when you’re older—especially when all you want to do is curl up in bed. It’s a funny bit.

Reminded me of authors.

Very few of the ones I’ve known have wanted to do interviews.

They want to write.

They want to eat in their own kitchen, not in restaurants on the road.

They want to sleep in their own beds, not in hotels, motels, or the Holiday Inn.

They aren’t interested in any of it, but they know they have to do it, and they have to get into the mood.

Back to Canfield and Hansen—or whichever one said do something every day.

Think about interviews, or networking or whatever it is that helps share your book just as you might think about losing weight or saving money.

You don’t have to do a lot every day, but you have to do something.

Something. Every day.

So what is that something?

This is where it gets frustrating—and where I get angry at sites that have all the answers for how to launch a bestseller.

There isn’t one plan that will yield the same results for two different people/books.

I can give you a long list of books that, at their core, were launched the same way (minus some tweaks here and there), and they didn’t all hit the bestseller list. Part of it is the author, part is the topic, part is just what’s going on in the world. I’ve known authors who were wonderful authors but awful speakers, authors who looked the part and had little to say and authors who weren’t “camera ready” and got little play because they were rough around the edges. I’ve had an author bumped because a plane was landing without all of its wheels and another author bumped because, yep, another plane story won out.

A few weeks back, I wrote about what does always works.

That’s where you have to start.

From there, look at what your favorite authors have done and make it work for you.

Adjust it a little every day, but do it every day.

I know. It’s not your thing. You want to write. Trust me. A little every day.

Here’s a small example:

Mary Doyle comments on almost all of our posts. I had no idea who she was years ago, but now . . . When Mary has a book ready to publish, I will buy a copy and let friends know about the book. Why? First, I expect it to be good and second, because Mary always shows up, is kind, and is a person I like. That didn’t come over night.

Don’t think this is just for authors you want to get to know. You’d be surprised to find that your neighbor runs the book club of 1,000 grandmothers at the local mega church, or that your kid’s teacher is a bestseller writer using a pen name. These connections are all around us.

You have to put yourself out there (or hire someone to do it for you).

In a worst-case scenario, that person might just save your life.

True story (though not 100% accurate because . . . memory and age):

A family friend survived the Bataan Death March all because of a cigarette.

He was an officer facing a Japanese soldier. He’d already been captured, but still handed a cigarette to the soldier. The soldier wasn’t high in his chain of command. A regular foot soldier. He couldn’t help the American officer and the American officer knew it. He just had a cigarette and offered it. The soldier took it. Later, during the march, the officer fell. The person who helped him? The soldier to whom he gave a cigarette.

What the officer did was no different from what he might have done on the streets of his North Carolina home, but this time? Saved his live.

Put yourself out there.

A little every day. Might help share your book. Might help save your life.

January 30, 2019

Introducing Shane

I love the movie Shane.

In my opinion it’s the greatest Western ever, surpassing even The Searchers and The Wild Bunch and High Noon, not to mention Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Unforgiven.

I’m aware that many reading this post have not seen Shane, or may not have even heard of it.

Alan Ladd as the title character in “Shane”

The film did come out in 1953, which is, I admit, a few years ago.

So I understand.

Nonetheless, if you’ll forgive me, let me make a pitch here and now for Shane, the classic Western starring Alan Ladd, Van Heflin, Jean Arthur, Brandon deWilde and Jack Palance, directed by George Stevens and written by A.B. Guthrie, Jr. and Jack Sher from Sher’s 1949 novel (that he wrote as Jack Schaefer.)

I took a class in Greek tragedy in college. I got a D both semesters.

That was the downside.

The upside was I was exposed to the following term/concept:

The coincidence of the anagnorisis and the peripateia.

(I’ve been waiting five decades to use that in a sentence.)

Here’s Merriam-Webster’s definition of anagnorisis.

the point in the plot especially of a tragedy at which the protagonist recognizes his or her or some other character’s true identity or discovers the true nature of his or her own situation.

Peripateia is a little simpler to define.

Reversal of fortune.

In tragedy, reversal of fortune almost always means the plunge from the penthouse to the outhouse. The hero’s great fall from grace. Catastrophe, in the true Greek-derived sense of the word (kata = down, strophe = stroke or movement).

“Coincidence” in the phrase above doesn’t mean a random coming-together, as we might conventionally define it. It means simply when two things happen at the same time, i.e. when they coincide.

The coincidence of the anagnorisis and the peripateia means simply that the moment when the hero realizes who he or she really is … is the moment when his or her world falls apart.

The defining characteristic of a tragedy (as opposed to a comedy or a conventional narrative) is the coincidence of the anagnorisis and the peripateia.

Oedipus, in the moment he is confronted with his true identity (“OMG, I’m the one in the prophecy who was fated to kill his father and marry his mother … and I did so!”), falls from the blessed king of Thebes to the human being most hated by the gods—and the cause of his country’s cataclysmic suffering.

Yikes!

No wonder he plunges spikes into both his eyes.

Shane is a tragedy too.

How do we know?

Because Shane, like Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, is defined by the coincidence of the anagnorisis and the peripateia.

Shane the gunfighter enters the valley believing/hoping that he can change his life.

His aim is to hang up his six-shooter and become a normal human being, a regular guy.

Shane goes to work as a ranch hand for brave, good-hearted sodbuster Joe Starrett (Van Heflin)—willingly taking on a role far beneath his station. He is befriended by (and secretly falls in love with) Starrett’s wife Marion (Jean Arthur.) This bond reinforces Shane’s hope that he can achieve a conventional life. Perhaps there is another woman like Marion, whom he might meet someday and with whom he could settle down, raise a family, etc.

But trouble comes to the valley in the form of black-hatted gunslinger Wilson (Jack Palance), who has been brought in by the cattleman villain Rufe Ryker (Emile Meyer) to buffalo the sodbusters and drive them from their farming claims.

Jack Palance as the gunfighter Wilson in “Shane”

No one in the valley, not even valiant Joe Starrett, is capable of standing up to the threat of Wilson.

No one but Shane.

Out of love for Marion (and her son little Joe [Brandon deWilde]), Shane straps on his .44 and rides into town to face Wilson.

With Joey watching from the shadows, Shane outdraws Wilson and kills him—and Ryker and Ryker’s co-villain brother too, when they try to gun him down from hiding.

Shane does all this fair and square.

In the audience we dare to believe that a happy ending is moments away.

Shane has saved the day!

The town will honor his courage!

He can find a place of his own and make a life here in the valley, as he had hoped!

Instead Shane mounts up to ride on.

Little Joe reacts with shock and chagrin.

JOEY

But, Shane, we want you! Pa’s got things to do.

And Mother wants you, I know she does!

Shane understands what little Joe doesn’t.

This moment is his anagnorisis.

In the shootout with Wilson, Shane realizes his true identity.

He is a gunfighter.

Nothing and no one can alter that fact.

SHANE

A man has to be what he is, Joey. He can’t break the

mold. I tried, and it didn’t work for me.

The moment is Shane’s peripateia as well. His reversal of fortune.

SHANE

Joey, there’s no living with a killing. There’s no

going back from it. Right or wrong, it’s a brand. A brand that sticks.

No course remains for Shane but to ride on.

JOEY

Shane, come back! Shane!

This moment, to me, is one of the greatest in American cinema. What might have been an ordinary Western is elevated in this climax to the sphere of tragedy, which is to say a work of art expressing a far deeper understanding of life than Hollywood movies are noted for.

That’s why I put Shane above even the greatest of the other great American Westerns.

January 25, 2019

Glove Before Stick

From the archives, via September 16, 2011.

Fifteen years ago, I worked at St. Martin’s Press. It was (and still is) one of the big six publishing players. If ever there is a sitcom about book publishing, it should be set in the 1990s at St. Martin’s Press. What a cast of characters…

Anyway, the head of the company was a man named Thomas McCormack, a real autocrat with more than a few eccentricities. Every day, Tom would order a tuna fish sandwich and a small cup of Vanilla ice cream from the ancient delicatessen across the street (http://www.eisenbergsnyc.com/). He wasn’t a publishing lunch schmoozy kind of guy… Invariably, he’d not have time to finish the sandwich or even get near the ice cream, so when you went to his office for one thing or another, Tom would open up his mini-fridge and offer you one of the tens of little freezer burned ice creams stuffed inside.

Tom was the boss of bosses at St. Martin’s (actually started the whole thing years before) yet he also served as SMP’s Editor in Chief. He ran the editorial meeting every Wednesday morning at 9:30 a.m. sharp in the flatiron building’s seventeenth floor conference room. Imagine CBS’s Leslie Moonves meeting once a week for six hours with every in house producer and show runner to approve or reject his or her story ideas. Crazy for a CEO to get his hands that dirty, right? He should be riding his own elevator (like another famous publishing CEO at the time) and looking for strategic long term growth alliances…

Every Wednesday, all of SMPs editors would circle a very large conference table with Tom at the head, closest to the door. There was no way you could sneak out without him seeing you. We all tried at one point or another, but he’d always catch us. He’d squint his eyes like Clint Eastwood until we slinked back to our designated seat. There was another larger circle of chairs surrounding the table itself. Seniority gave you a spot at the big table, but every single editor and editorial assistant was required to attend. And Tom gave every single one in the room a chance to pitch. At many of the other houses I worked when I was on that side of the business, editorial assistants weren’t allowed to get near an editorial meeting. They had to “earn” it. But Tom actually had a second editorial meeting each week…just for editorial assistants…

The meeting began with Tom literally reading index cards. On each card was the name of a novel or proposal that had been submitted to the house the previous week.

“Coyne has in a proposal from Writers House purporting to be the lost diaries of Howard Hughes…Ehhh, an unlikely proposition.” And so on.

At around 11:00 a.m. the editors would begin whispering to one another…

“Is it Chinese today? Pizza?”

“Nah, (big sigh) it’s the big Sandwich…”

As the meeting was interminable, Tom ordered lunch for everyone in the room. He’d still get his tuna fish and ice cream. The rest of us would jockey for positions at a long card table that often held a nine foot long grinder/hoagie/submarine loaded with MSG and gritty oregano, hoping to avoid the soggiest sections.

After the reading of the cards, the moment arrived when the gastric juices of the room really got flowing. Tom would begin the interrogations. He’d start with the highest ranking editor and simply say…

“What do you got?”

The editor would either simply shake her head “no” to indicate she didn’t have anything to pitch or she’d launch into a spiel she’d spent the previous two days sketching out in her mind and rehearsing in front of her bathroom mirror. Woe be the person who failed to project her voice enough so that all in the room could hear…

“I have in a brilliant first novel about a marauding band of gypsies who have broken the space time continuum (silence). The leader of the band is a transvestite soothsayer whose backstory reminded me that of Magwitch in Dickens’ Great Expectations…”

Tom cut her off.

“Sounds like a dog’s breakfast to me!”

A newbie assistant would nudge a more grizzled twenty-something close by and whisper…What’s a dog’s breakfast?

Tom would then spin around on his thirty year old pair of black Florsheims. He’d stare down the whisperer as if the young man had just scratched his vintage Studebaker.

“A DOG’S BREAKFAST IS TURKEY, MEATLOAF, PASTA, SALAD (he’d tick off a finger on his left hand to emphasize each foodstuff) WHATEVER’S LEFT IN THE ICEBOX! THIS GODDAMN NOVEL SOUNDS JUST LIKE THAT…SCIENCE FICTION AND FAMILY DRAMA WITH THE PROMISE OF THROUGHLINE CRIME SLOSHING AROUND WITH A REDEMPTIVE MATURATION PLOT! CHOOSE ONE GENRE AND DO IT WELL. DON’T PUBLISH WRTERS WHO DON’T CHOOSE!”

Wednesday whisperers would either be in tears at the end of the explanation, or their instinctive recoiling away from the screaming madman would alter their equilibrium in such a way that their chairs would rock back from a four legged purchase to two. Depending on the length of the tirade, their center of gravity could reach critical mass. The chairs would then tip backwards and deposit them with a thud onto the decades-old, wall to wall, shag carpeting. Pretty embarrassing.

Tom would then turn back to the veteran editor with his eyebrows raised and sweetly say “Anything else?”

Multiply this process by twenty five full editors, with 30 odd editorial assistants and you’re deep into the afternoon. Remember this was the era of no blackberries or IPhones, or even e-mail. The only “instant” communication device we used to conduct business was the telephone. Every editor at the company would blow a full day watching Tom excoriate his colleagues, if not himself too.

The best (worst) was when Tom was actually intrigued enough by a book idea that he asked the editor to run down the P&L for him. If the editor made the financial case, Tom would give her clearance to make an offer for the book. A profit/loss report is a crucial tool for any business. And for book publishing it’s essential to understand the risks involved in publishing any one particular book.

There are many variables to consider and Tom considered it mandatory that his editors converse in P/L-ese as well as his accounting department. To Tom, it was irresponsible to publish a book without knowing all the shit that could go wrong. He wouldn’t put up with the standard “I’m just no good with numbers” excuses that editors liked to hide behind. You had to field as well as you hit. Better in fact. Or you wouldn’t be allowed to get to the plate.

It was physically painful to watch a young editor choke on Tom’s P/L questioning. It was a machine gun gauntlet…What’s your price? What’s your trim? What’s your PPB? What’s your royalty? What’s your ship? What’s your net? What’s your ROI? I choked once. Every one of the other 25 editors had at one time too. With Tom, you didn’t get a chance to choke twice.

Like scores of other publishing professionals, I learned far more from Tom McCormack than I ever gave back to SMP. And as was Tom’s way, the day I left St. Martin’s to start a new job at a competing house with a superior title and double my SMP salary (he ran p/ls on his editors too and I’m sure he knew when an editor’s compensation would most likely exceed his contribution), he called me up to his 18th floor office at the triangle of the flatiron building to say goodbye.

And as I unwrapped a cheap wooden stick-spoon and began to chip away at a vanilla cup, Tom looked me straight in the eye and said, “After you learn all of their secrets, you come back here!”

January 23, 2019

The Villain Adapts, but Does Not Change

Consider the Alien.

It adapts but does not change.

It starts out (I’m thinking of the 1979 Alien, directed by Ridley Scott) as an egg.

OMG, it springs onto the visor of Kane’s (John Hurt) space helmet!

Wait … now it’s an ugly, tentacled blob attached to his face. Hold on—it just leapt out of his chest and scurried out of the room!

The Alien introduces itself to the crew of the Nostromo. The dude adapts but does not change.

It’s medium-sized …

It’s bleeding acid-blood!

It’s huge!

The villain adapts. It comes after the hero in protean forms, from all directions, using all kinds of ploys and stratagems.

The Thing.

Species.

Human villains too keep attacking from all angles. Bond villains. The mother and sisters in The Fighter. The cops in Thelma and Louise. The impis in Zulu.

But they don’t change.

They have one goal—to destroy the hero.

They cannot be reasoned with.

They are incapable of altering themselves on their own.

They are as fixed and immutable as the stars.

Do you remember the principle we cited in an earlier post from Stephen Cannell, the master of a thousand plotlines from The Rockford Files, The A-Team, and 21 Jump Street?

Keep the heavies in motion.

What Stephen meant was

Keep the villains coming at the hero from everywhere.

Have them pop out of the toaster, drop out of the sky, spring forth from the glove compartment. At any moment. In all forms and shapes and sizes.

The villain should not to stupid.

Walter Pidgeon as Dr. Edward Morbius in “Forbidden Planet”

Like the Predator or the Terminator, the Bad Guy should shape-shift like a chameleon. Make him cunning and ruthless and loaded with guile.

Even internal villains, like Dr. Morbius’ (Walter Pidgeon) possessiveness of his daughter Altaira (Anne Francis) in Forbidden Planet or Ethan Edwards’ (John Wayne) implacable hatred of Comanches in The Searchers, don’t change.

They may be overcome by the hero (in which case the hero is the one who changes) but they themselves never draw up and declare, “Gee, now that I think about it, maybe my desire to destroy the world/devour the protagonist’s brain/suck the heroine’s blood was really not such a good idea.”

The villain adapts but does not change.

The greatest villain of all, Satan, pulls out all the stops trying to break his arch-enemy, Jesus of Nazareth. He invokes the Sanhedrin, Pontius Pilate, the Roman legions. He causes Judas to betray his master. He undermines Peter’s love and loyalty; he cracks the resolve of all the Apostles.

But his goal never changes, and neither does he.

That’s why he’s the villain.

Remember our principle:

The hero is the one who changes.

The villain adapts, but does not change.

Or as my old boss Joan Stark expressed it,

If the villain changed, he’d be the hero.

January 18, 2019

Art and Polarity

From the archives, via June 20, 2012.

The other day I overhead this conversation:

Man #1: “I ran into Frank Smith (not his real name) at the beach yesterday…”

Man #2: “Isn’t that the guy who cheated on his wife, got a DWI, and said all of those nasty things about Jill’s daughter in law?”

Man #1: “…Well…yes…but I try not to judge.”

I run into this “I don’t judge” stuff a lot and it infuriates me on many levels. But as this is a blog about what it takes to create art, I’ll just address why this “moral position” is at best hypocritical and at worst a force as undermining and dark as Resistance.

If you want to create art, you need to make judgments about human behavior and take a side. How well you convey and support your point of view is a measure of your skill. On-the-nose judgments in art, like that hilarious statue of the founder of Faber College in Animal House with the epitaph “Knowledge is Good” are funny because they are so generic.

The epitaph tells the viewer that the setting of the story is a College founded by an idiot. What is really wonderful about that scene is that it appears in the opening credits, giving the viewer no doubts about the tenor of the art to come.

The scene in Woody Allen’s Manhattan where the Woody character is having cocktail conversation at the Museum of Modern Art is another one of my favorites…

Guest #1: “Has anybody read that Nazis are gonna march in New Jersey, you know?”

Woody character: “We should go there, get some guys together. Get some bricks and baseball bats and explain things to ’em.”

Guest #2: “There was this devastating satirical piece on that in the Times.”

Woody character: “Well, a satirical piece in the Times is one thing, but bricks get right to the point.”

Guest #2: “But biting satire is better that physical force.”

Woody character: “No, physical force is better with Nazis. It’s hard to satirize a guy with shiny boots.”

Today’s “let’s all get along, not judge or challenge anyone” groupthink also reminds me of a major scene sequence in Milos Forman’s adaptation of Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

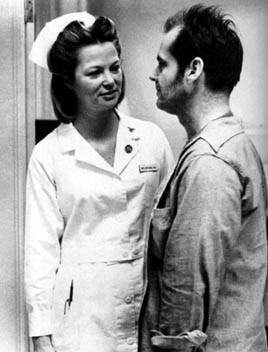

Polar Opposites: Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched and Jack Nicholson as R.P. McMurphy.

Jack Nicholson portrays R.P. McMurphy, a good time Charlie with authority figure issues. He’s playing crazy at a maximum-security insane asylum to get out of a work detail jail sentence. Years ago, they sentenced petty criminals to hard labor. I remember as a kid being in the backseat driving South and watching chain gangs cutting overgrown brush on the median of I95—Donn Pearce must have seen them too. He wrote Cool Hand Luke.

McMurphy’s Moriarty is Nurse Ratched, the head nurse in the asylum. Louise Fletcher played this role so brilliantly—all ice and pursed lips—she had difficulty finding work after winning the Oscar for it.

One afternoon, during an interminable group therapy session, McMurphy requests that the guys be allowed to watch the World Series that evening. Knowing that the last thing the other men would want to do is stand up and challenge the way she rules her kingdom, Ratched sees an opportunity to put McMurphy in his place.

She’ll put the request up to a vote.

McMurphy sticks his hand up to vote “yea” assuming that his fellow patients will come to the same conclusion that he has. By simply raising their arms, together the men can let this lady know that denying a simple pleasure like watching a ball game to a bunch of lunatics is absurd.

Which one of you nuts has any guts?

The needy fuser Cheswick is the only other one who has the courage to challenge Nurse Ratched’s command. Meeting adjourned. The men are then shuttled into the shower room for their evening cleaning. McMurphy is out of his mind with anger.

If you’re a writer, this scene is a perfect example of a set-up that dramatically portrays a character’s inner change. How does Ken Kesey pay it off?

From the first moment McMurphy lays eyes on Ratched, the reader/viewer knows he judges her as rotten to the core. McMurphy is not afraid to judge. His problem is that he acts on his judgments too quickly. That’s what got him in the clink in the first place.

In the nuthouse, though, he is forced to keep the judgment to himself. He’s supposed to be crazy! And to McMurphy, only crazy people don’t judge, so he shouldn’t either.

But when the evidence of Ratched’s evil is incontrovertible to him, he can’t help himself but act. He’s the novel’s protagonist. He’s the hero. If he doesn’t act on his judgments, there’s no story.

Kesey could have made any number of choices with this scene. He could have had McMurphy act selfishly, like a child, and physically attack a guard or an inmate or himself. Something the character has a reputation for doing earlier in his life.

Instead, for the first time (and the perfect time) Kesey has his character act beyond himself. He changes his behavior. McMurphy sees that these men have it within themselves to judge Ratched as a tyrant. If he can make them understand how important it is to make a judgment and to act on that judgment—even if it puts them in harm’s way—he will help them. And helping them will help him bring down tyranny. He’ll win.

McMurphy, already known as a consummate hustler, challenges all of the men to take a bet. He puts all of his money on his succeeding. He will pick up a thousand pound marble bathroom vanity, throw it through the barred window, walk to a nearby bar with his buddy Cheswick, wet his whistle and watch Mickey Mantle play in the World Series…Who wants some of this action?

He’s so convincing that only the most cynical among them take his bet.

Playing McMurphy as only he could play him, Jack Nicholson grabs the edges of the vanity, squats and surges into the plumbing. He turns blue from effort. He commits to the action, gives it his best shot. When he’s drenched with sweat, spent and defeated, he walks out of the room. But not before turning to the stunned assemblage and saying:

“At least I tried.”

As a child in the 60s and 70s, I was raised on stories like this. (I wish we had more of them today) And they’ve had a profound influence. This is why art is so important.

These stories taught me that to passively disengage for fear of reprisal is cowardly. Making a judgment, taking a stand and then acting against an injustice or acting to support excellence is the stuff of the everyman hero.

And yes, not saying anything, not “judging” the horrible or honorable behavior of other people is acting too. As deliberate an act as getting overly excited about an idea and shouting in a business meeting.

If you don’t call people on their shit, you’re placing yourself above them, as if their actions are so inconsequential to you that they need not be considered. You’re above it all, some kind of Ayn Randian ubermensch behaving only out of self-interest. The same goes for not giving a standing ovation for great work because others remain seated. If you admire a work, let the artist know. They can use all the attaboys they can get. It’s Hell in that studio.

Despite the initially convincing argument that to “not judge” is an expression of empathy—who knows, if I faced those same circumstances maybe I’d do something like that too? —It’s not. It’s an excuse for not standing up for what’s right.

Not saying something is uncaring. Not saying something means that you do not want to put your ass on the line and take the risk that you’ll be shunned for your opinion. It has everything to do with you. Nothing to do with the other person.

I’m aware that the world is not black and white. There are shades of gray between the two poles of every value. On the spectrum of “Truth and Deceit,” telling a white lie when your cousin asks if she looks good in her bathing suit is not the same as running a billion dollar Ponzi scheme. I get it.

And yes, most of the time, keeping our big mouths shut is the right thing to do. We’re all guilty of misdemeanors and don’t need Earnest Ernies pointing out our shortcomings. And when we do confront someone about their actions, we need to do it with tact and care. That’s empathy.

But this “non-judgment, I toe the middle line” attitude is dangerous. There is no middle line. Not judging is a judgment. And it pushes people away from each other—I best not make a mistake and judge anyone or no one will like me…best to keep quiet and be agreeable—instead of bringing them together—I thought I was the only one who thought Animal House was genius…

The man I overheard who doesn’t “judge” the adulterous, alcoholic driving, rumormonger sends a message to the world that destructive actions are excusable. It is what it is… There is no right and wrong. Nonsense.

But it is his passive aggressive dressing down of the other guy for “judging” someone guilty of antisocial behavior that is even worse. It masks his cowardice as virtue. And to not judge whether something is right or wrong is the furthest thing from a virtue.

You must choose a position in this world on innumerable moral questions and stand by your judgments. Woody Allen made this point in six lines of dialogue. Ken Kesey riffed on it for an entire novel. It’s important.

If you are an aspiring artist and you wish to avoid “judgments,” you’ll find that you have nothing to say.

January 16, 2019

Kurosawa on Villains

We were talking last week about how the villain never changes.

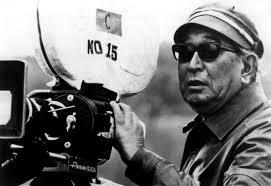

Akira Kurosawa, director of “Seven Samurai,” “Rashomon,” and many other classics

The hero does.

But never the Bad Guy.

Here’s Lawrence Kasdan (Body Heat, The Big Chill, The Accidental Tourist, not to mention Raiders of the Lost Ark, Return of the Jedi, etc.) quoted in a 1991 article in the L.A. Times:

“(Akira) Kurosawa, the greatest director who ever lived, said that villains have arrived at what they’re going to be . . . that’s their flaw, but that heroes evolve–they’re open to change and growth.”

Kasdan in this context was referring to his own aspirations as a moviemaker. He hoped, he said, to be a hero in his own career, by which he meant he intended to keep evolving as a writer and director, to never settle for doing something he had done before.

But let’s consider Kurosawa’s observation in its own right—as a principle of storytelling relating to antagonists.

Certainly the brigands in Seven Samurai don’t change.

The villain in Rashomon is humanity’s craven need to present itself in a positive light, even if it must perjure itself shamelessly to achieve this. That surely doesn’t change.

But Kurosawa gives the villain credit for possibly evolving into his or her state of stasis.

The villain has arrived at who he or she is going to be … that’s the villain’s flaw.

Kurosawa is augmenting our original statement

The villain doesn’t change

by declaring first, that

The villain has changed in the past but has now reached a state from which he or she no longer can or wishes to evolve

and further that

This state of completion/stasis/self-satisfaction is the villain’s weakness.

This is great grist for you and me as writers.

Let’s take the first part first.

Has the villain evolved prior to our meeting him or her in the narrative?

J.R.R. Tolkien may have thought so.

Nothing is evil in the beginning [says Elrond in The Lord of the Rings]. Even Sauron was not so.

I’m not sure if I believe this.

The character of “Dick Cheney” in Vice has certainly changed from his early Wyoming days. Or has he? Was he always who he was, though it took the passage of time to reveal this?

Christian Bale as Dick Cheney in “Vice”

Did Darth Vader evolve?

How about Hannibal Lecter?

Gordon Gekko?

Has the Terminator evolved?

The Alien?

The Predator?

I’m not sure it particularly matters.

The point for you and me as writers (and Kurosawa agrees) is that our villain cannot and does not evolve from the point when we meet him in the story.

Medea was a lover and valiant helpmeet to Jason before he abandoned her.

Clytemnestra was Agamemnon’s caring wife before he sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia.

Even Scrooge McDuck may have been a good guy at one time.

But by the time we meet them onstage or in the movies, these villains are bad to the bone.

Heroes evolve [says Kurosawa, cited by Kasdan]. They’re open to change and growth.

Villains aren’t.

Bad Guys do not change.

January 11, 2019

Brian Wilson, Warren Buffett, Albert Einstein, and Ruth Stone

From the archives, via May 5, 2017.

In the documentary Beach Boys: The Making of Pet Sounds, Al Jardine said Brian Wilson “sees things I don’t think the rest of us see and hears things, certainly, that we don’t hear. He has a special receiver going on in there, in his brain.”

What is that special, indefinable “it” about Brian Wilson? Is it really related to seeing, hearing, and receiving? And, if it is, what’s different about how he sees, hears, and receives? What of the rest of us? Why aren’t we all walking around composing “God Only Knows” or any other Wilson and Tony Asher masterpiece?

What Are You Hearing?

In his book The Brain’s Way of Healing: Remarkable Discoveries and Recoveries from the Frontiers of Neuroplasticity, Dr. Norman Doidge shared the work of Dr. Alfred Tomatis, whose groundbreaking work identified “the ear as a battery to the brain.”

From the chapter “A Bridge of Sound” in The Brain’s Way of Healing:

In the late 1940s Tomatis continued to attack the conventional wisdom that the larynx is the key organ for singing. He showed that contrary to conventional wisdom, singers with bass voices did not have larger larynxes than those with higher voices. Human beings aren’t constructed like pipe organs, in which larger tubes produce lower sounds. Powerful tenors sing at frequencies from 800Hz up to 4,000 Hz but so do baritones and basses; the only difference is that the baritones and basses can add lower notes, because they can hear lower notes. He summed it up by saying provocatively “One sings with one’s ear,” a statement that caused much laughter.

But when scientists at the Sorbonne presented their studies of his work to the National Academy of Medicine and the French Academy of Sciences, they concluded that “the voice can only contain the frequencies that the ear can hear.” The idea came to be called “the Tomatis effect.”

Tomatis didn’t stop there. He invented a device called the “Electronic Ear” to help struggling singers. The device blocked out different frequencies, which trained the singers’ ears to hear the frequencies with which they’d been struggling/missing. By exercising their ears, they strengthened their voices, just as they might engage in exercise to strengthen other parts of their bodies.

Among us non-singers, Tomatis found, too, that the frequencies we hear can be influenced by our countries of origin. For example, he found that the French “hear in two ranges, 100 to 300 Hz and 1,000 to 2,000 Hz. Speakers of British English hear in one higher range, from 2,000 to 12,000 Hz, which makes it hard for French people to learn English in England. But North American English involves frequencies from 800 to 3,000, a range closer to the French ear, making it easier for the French to learn.”

More from Doidge:

Arguably [Tomatis’] most important discovery was that the ear is not a passive organ but has the equivalent of a zoom lens that allows it to focus on particular noise and filter others out. He called it the auditory zoom. When people first walk into a party, they hear a jumble of noises, until they zoom in on particular conversations, each occurring at slightly different sound frequencies.

Jardine’s comment that Brian Wilson hears what others don’t hear, might be right. It’s possible that Wilson tunes into frequencies and zooms into sounds/rhythms/conversations that the rest of us aren’t accessing. Even more remarkable is that Wilson is deaf in his right ear, which is the dominant ear for the majority of us. By accessing sound through his left ear, he’s automatically processing sounds outside the norm.

What are You Seeing and Receiving?

In the same Beach Boys documentary, Wilson mentioned that he “copied The Four Freshman singer, the high singer,” when he wrote “Surfer Girl.” He tapped into a musical influence and merged it with interests of his peers. While he didn’t surf himself, he understood—he saw—the appeal of the surfing culture, just as he did the car culture, just as he did the raw fact that the lives of most of his peers revolved around school and dating.

There’s a difference in this sort of seeing, just as there is in hearing as researched by Tomatis. There were millions of other guys Wilson’s age seeing the same thing. Even Wilson’s own bandmates saw the cars and girls and surfing culture, but . . . They didn’t do what Wilson did.

Why?

In the documentary Becoming Warren Buffett, Buffett was asked the following question:

“What are the key indicators you look for in companies before making an investment?”

He replied by talking about Berkshire’s investment See’s Candies:

“If you give a box of See’s chocolates to your girlfriend on a first date and she kisses you . . . We own you. . . We could raise the price of the boxes tomorrow and you’ll buy the same box. You aren’t going to fool around with success. The key here is the response.”

Buffett is right. My godmother introduced me to See’s Candies’ boxes of chocolates over forty years ago. I loved them then—and now she’s gifting them to my kids today. That’s loyalty.

But why does Buffett think like that? Why did he see that potential in See’s Candies? Just like Brian Wilson’s peers could see the response to songs about surfing, cars, relationships, and school, Buffet’s peers could see the response to the gift of a box of chocolates. What’s the difference between Buffett, Wilson, and their peers?

Why do they find creative configurations for random puzzle pieces, when all anyone else sees are mismatched puzzle pieces?

Exposure and Experience

Wilson had to be exposed to The Four Freshman and Buffett to See’s Candies—and to what was going on in the world around them—in order to connect songs and products to cultures. In order to do this, they needed experiences that would allow them to connect the dots. This comes from constant exposure and experimentation—paying attention to what does/doesn’t work in the surrounding world, and learning from it.

This is reading everything you can read, listening, painting, practicing whatever it is you love over and over and over again.

For Buffett and Wilson every song composed and deal made can be filed under practice, which brings more experience.

Internal Engine

To do all the things mentioned above, there has to be an engine, a drive to capture it all.

In a TED talk, Elizabeth Gilbert told a story about how poet Ruth Stone described poems coming to her, on a “thunderous train of air”:

It would come barreling down at her over the landscape. And she felt it coming, because it would shake the earth under her feet.

She knew that she had only one thing to do at that point, and that was to, in her words, “run like hell.” And she would run like hell to the house and she would be getting chased by this poem, and the whole deal was that she had to get to a piece of paper and a pencil fast enough so that when it thundered through her, she could collect it and grab it on the page.

And other times she wouldn’t be fast enough, so she’d be running and running and running, and she wouldn’t get to the house and the poem would barrel through her and she would miss it and she said it would continue on across the landscape, looking, as she put it “for another poet.”

And then there were these times—this is the piece I never forgot—she said that there were moments where she would almost miss it, right? So, she’s running to the house and she’s looking for the paper and the poem passes through her, and she grabs a pencil just as it’s going through her, and then she said, it was like she would reach out with her other hand it and she would pull it backwards into her body as she was transcribing on the page. And in these instances, the poem would come up on the page perfect and intact but backwards, from the last word to the first.”

I love this story. It’s like capturing a dream. You have to write it down the second you wake or you risk it floating off to Never Happened Land.

What powers an engine like Stone’s or Buffett’s or Wilson’s?

I think it’s curiosity.

Have you watched the new National Geographic series, Genius? In the first episode, a young Albert Einstein is driven by a need to know. Curiosity is at the helm, pushing him for answers.

Why Does Any of this Matter to You?

Within the first few minutes of the Beach Boys documentary, David Marks said, “People think ah, I can do that, but they can’t. It’s only something Brian could do.”

Wilson, Buffet, Williams, and Stone had/have a gift for connecting the dots. Their ability to bring together all the information coming their way—whether in dreams, Muse-driven trains, or cocktails parties—is extraordinary.

Do I think we can all do what they do/did? No.

Do I think we can tap into what I’m guessing to be qualities existing within their creative process? Yes.

We talk about hard work on this blog all the time.

What we don’t talk about as much is what we see and hear. Sometime you have to lift your head from your work and process what’s going on around you. What do you really hear and see? And of what you’re receiving, is it the full experience or are you missing out on an entire cocktail party?

The other part of lifting your head is this:

Big ideas aren’t necessarily a sign of genius, but of someone with the capacity to make connections between all the dots swirling around them.

How often do you hear about those ideas happening after an all-nighter of working?

They arrive during a hot shower and in the seconds before you go to sleep. They float in on a song, or a well-crafted sentence—and come along just when we least expect them—sending us flying like Ruth Stone to capture them.

We can do all the work and practice in the world, but minus the mental gifts Wilson, Buffett, Einstein, and Stone were born with, I think the thing we need most is to really see and hear the world around us and within us. Just as Tomatis helped improve the voices of singers, I think his same methods of tapping into different frequencies can help guide our creative endeavors. And when I say frequencies, I’m not necessarily talking just about traditional “sound.” Remember, Beethoven composed even after losing most of his “hearing.” (Maybe he did this by relying on “bone conduction?” *Read Doidge’s book.)

Are you tuned into all the frequencies possible?

January 9, 2019

The Villain Doesn’t Change

The craziest working arrangement I ever had in the screenwriting biz was when I worked for a producer I’ll call Joan Stark.

Joan insisted that I write in her office. I had to come in every day. Joan gave me a little cubbyhole beside the photocopy machine. I’d work on pages all morning and half the afternoon. Then we’d meet and Joan would go over the day’s work and give me corrections.

Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis as the heroes in “Thelma and Louise”

Every day she had problems with the same character—the villain.

She kept making me rewrite his scenes. One day I asked why. What mistake was I making?

You’re having the villain change. The villain can’t change.

I didn’t get it. “Why not?”

Because if the villain changed, he’d be the hero.

I remember thinking, That is the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard. Don’t we want the Bad Guy to be interesting? Shouldn’t he evolve like the Hero?

Answer: No.

The Alien doesn’t change. The shark in Jaws doesn’t change. The Terminator in The Terminator doesn’t change. And when he does in the sequels … OMG, he becomes the hero (or co-hero)—and we have new Terminators (who don’t change) who now become the villains.

I realized I had to start thinking more deeply about this.

Indeed external villains don’t change. Every antagonist in a James Bond movie. Every super-villain lining up against Batman, Superman, Spiderman, Iron Man, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men. Every force-of-nature villain (volcanoes, tsunamis, Mayan-predicted worldwide destruction, asteroids-crashing-into-Earth, Tripods invading New Jersey, global climate catastrophes). None of these is capable of change.

Zombies don’t change.

Vampires don’t change.

The Thing doesn’t change.

All these Bad Guys have one single-minded desire.

To eat your brain.

To suck your blood.

To destroy (or dominate) the world.

To give birth to baby Bad Guys.

Societal villains (as opposed to external villains) don’t change.

Racism in To Kill a Mockingbird, The Help, BlacKkKlansman.

Homophobia in Philadelphia, Dallas Buyers’ Club, Moonlight.

The societal villain in Thelma and Louise, written by Callie Khouri, (who won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay) is male contempt for and domination of women.

The film depicts men as loutish husbands, leering truck drivers, sneak-thieving hitch-hikers, trigger-happy cops and FBI agents, and the arch-villain Harlan Puckett (Timothy Carhart) who commits the initial sexual assault on Thelma (Geena Davis) as a brutish, contemptuous, would-be rapist.

None of these Bad Guys changes.

What’s interesting about Callie Khouri’s character construction is that she does give us one decent man—Arkansas State Police investigator Hal Slocomb (Harvey Keitel). Hal is the only one among the cohort of law enforcement lummoxes pursuing Thelma and Louise who actually has sympathy for the women’s predicament and wants to help them. Hal even strikes up a bit of a telephonic friendship with Louise (Susan Sarandon) as he seeks to keep the police chase from getting out of control and devolving into a bloodbath.

Does this make Hal a villain-who-changes and thus an exception to my producer boss Joan Stark’s rule?

In the movie’s climax, when Thelma and Louise flee from the cops toward Grand Canyon thin air in their ’66 Thunderbird convertible, it’s Hal who rushes forward on foot into the path of all-out police gunfire to try to stop (and save) the ladies.

Does Hal’s act make him a villain who changes?

Yes.

But our employer Joan Stark comes out right in the end.

If the villain changed, he’d be the hero.

Hal becomes by his actions not a villain but the protagonist of the “C” or “D” story—the Police Chase Subplot.

He becomes a hero.

The villain never changes.

January 4, 2019

A Correction: Nothing Always Works With Everyone

Last Friday I wrote that the list of things below always work.

Hard work has always worked.

Being honest has always worked.

Doing the right thing has always worked.

Keeping promises has always worked.

Being transparent has always worked.

Creating something of value has always worked.

Starting small has always worked.

Communicating in more than 140 characters has always worked.

Picking up the phone or meeting in person, instead of only texting or emailing has always worked.

A correction:

These always work with the first audience, they often work with the second and fourth audiences, and rarely work with the third audience.

Here are the four audiences:

1. People with You

2. People on the Fence

3. People Against You

4. People Who Don’t Know You

People with You

This group is in your corner. If you have a new release, they’ll buy it.

Because we all create duds from time to time, this group is essential when you make a mistake and/or create something not so wonderful. They won’t turn their backs on you. This is your home team. An example? Imagine post-Babe Ruth and pre-2004 Boston Red Sox fans. They kept buying tickets and showing up to games. Yes, they complained, too, but they stayed with the team.

People on the Fence

This is the group that knows your work but only buys it after reviews are released. They might know you’re an extraordinary chef, but that new restaurant you opened? They won’t show up until someone else confirms its worth, whereas People with You are there opening night.

Best way to get this group off the fence is to run through that list above. Will it get all the fence straddlers on board? No, but it’ll get some of them there, which means you’re growing the People with You category.

Example: Earlier this year I bought flowers from www.FiftyFlowers.com. I was in the market for cherry blossoms to send to my godmother, who always misses the cherry blossoms during her visits to Washington, D.C. I ran into a wall finding live blossoms for sale. Lots of the fake silk variety. Fifty Flowers, which I ran across during my search, had the real deal. I bought the flowers and then received an email from my godmother, with a picture of a plastic trashcan full of cherry blossom branches. She wasn’t throwing them away. She simply lacked something large enough to contain all of the cherry tree branches, so she cleaned out the bin, added water, and then waited for them to bloom—and then, since there were so many, she shared them with friends and at the school where she volunteers in Los Angeles, where cherry trees aren’t something the kids had seen in person either. She even tried transplanting one at the school. Didn’t work, but the kids got behind the effort, so this one gift to her just kept on giving. The customer service was extraordinary, which led me to buy lilies for my aunt this past week. Once they arrived, she couldn’t stop talking about them. Beautiful. Fresh. Gorgeous packaging. AND: A human called her to share how to care for the flowers, so they would last a long time. Will I buy from them again? Yes. I was on the fence, but the quality and kindness and personal care made me decide to step into their corner.

People Against You

Doesn’t matter what you do with this group.

They don’t like you and they don’t want to like you. It’s personal. There’s something about you that gets under their skin.

Around the time the first Harry Potter book was released as a movie, I was on a listserv for writers. One of the writers spoke out about J.K. Rowling. She said that Rowling had created unrealistic expectations for other children’s book writers. Rowling’s success was a fluke and she was bad for all other writers in that genre because she raised expectations, so that if your book didn’t have movie potential, it wouldn’t be published. She didn’t say it, but she was jealous and instead of seeing Rowling as someone who energized the children’s/young adult genre, she saw her as a negative. I don’t think Rowling could have done anything to change this writer’s mind.

However, my friend and mentor Bob Danzig once shared a story with me about kindness flipping a volatile situation on its head. At the time, Bob was the publisher of the Albany Times Union. One of the paper’s employees, who was also head of one of the printers unions, was a vocal critic of management and tensions were high. At an annual event for the paper, Bob was introduced to this man’s wife. A few weeks later, Bob and the wife ran into each other at the local grocery store and she burst into tears when she saw him. Her husband injured his back and feared that he’d never return to work. She told Bob that her husband could use a special chair, which made sitting up a few hours a day doable, but he couldn’t work full time. Bob called the man’s doctor and arranged to have one of the chairs installed in the newspaper’s composing room, where the employee could work as a copy editor a few hours a day. However, there was still the issue of the union. The union president didn’t want to change the agreement to allow for an individual—even an individual who had been on his side—to work non-approved union hours, and said he’d call for a strike if the employee did less than a full shift. Bob called the employee’s wife and arranged with her for her husband to arrive at work and meet Bob. When he arrived in his wheelchair, Bob pushed him up to the front of doors, where the other union members could see them. Instead of walking off, they clapped—and Bob and the once-critical employee became friends.

There’s a lot more to the story, and I know I didn’t nail every detail, but that’s the gist of it.

I’m guessing that the employee and others in the union saw Bob as a fat cat management type, which made it easier to be critical of him—easier to create an us against them scenario. However, once he got to know Bob, he learned that Bob grew up in the foster care system and was in his fifth foster home by the time he was 12, and that Bob graduated high school at age 16 (during a transfer from one home to another, they made a mistake about the grade he was in, so he was placed in a grade higher, and Bob just went along with it, since his focus was on survival and not school), and then after he graduated, he worked every day to support himself and then eventually a family. Nothing was ever given to him. He earned his role as publisher the hard way. He worked for it. Started as office boy and then spent two more decades rising. No nepotism or anything of the like. He knew Pain and knew the power of Kindness and Communication. Life changing.

This personal touch is often the only thing that will change the minds of those against you. There’s usually a personal reason behind their opinion of you. Has nothing to do with you, but with their perception of you.

People Who Don’t Know You

This group is just as they sound. They don’t know you exist—or they’ve heard of you, but don’t know anything other than your name. Once they’re turned onto your work, they love you or they hate you or they land on the fence.

For years I heard the names Haruki Murakami and Kazuo Ishiguro. Did’t take action—not even when Chris Guillebeau personally recommended Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running to me. Then I picked up Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and Remains of the Day and found myself hooked on both. Didn’t read anything from any other authors for a long time.

Did they reach out to me? No. Any personal kindness? No.

I liked their work and then I researched them and enjoyed reading interviews with them.

Go back to the Fifty Flowers example above for an example of personal contact with an unknown. I took a chance on buying the first time—and then they provided extraordinary service and I returned. And, I’ll go back again—and I’ll recommend them—all because 1) they provided something of value and 2) extraordinary customer service. They made it personal. There was no pre-printed card presented with the flowers. They picked up the phone and spoke with my aunt. Told her who the flowers were from and how to care for them, and, knowing my aunt, I imagine they were on the phone answering a few other questions, too.

Kindness. Personal contact.

How to Reach Your Audiences

You don’t need an expensive marketing campaign to do this. No need to purchase the next big platform or program or anything else.

Go to CVS or Staples or Michaels or the Dollar Store and pick up some stationary.

All you need is some thank you cards and/or a phone—and time. Lots of time. This won’t happen overnight, but the connections you make have the potential to be with you forever.

Get personal.

It won’t work with everyone, but it will always work with a specific group of everyones.

And those people it won’t work with? Why are you focusing on them anyway?

Think about history.

Civil Rights changes, as one example, didn’t occur because all the opponents’ minds were changed. They happened because the people for Civil Rights and the people on the fence came together, and pulled in people who weren’t previously in the know. They suffocated the fire of the opponents. Didn’t change their minds, but they were able to create change.

Focus on the people who love/like you. Let them be the evangelists. Reach out to those on the fence and work on connecting with those who aren’t familiar with you. Those groups alone should keep you busy for the rest of your career.

So, no, there isn’t anything that works 100% with every single person on Earth.

However . . .

There are truths that work 100% of the time with the audiences who should be your focus.

January 2, 2019

The “B” Story Rides to the Rescue of the “A” Story

We touched briefly in last week’s post upon the idea that the “B” story “rides to the rescue” of the “A” story, usually at the start of Act Three.

Let’s examine this principle in more detail.

Faye Dunaway and Robert Redford in “Three Days of the Condor”

If the “A” story is the primary tale, i.e., the narrative in the foreground, then the “B” story is often the love story—that is, a secondary narrative that runs parallel to the primary story and intertwines with it as the greater tale unfolds.

In Three Days of the Condor for example (and its latter-day clone, The Bourne Identity), the “A” story is the tale of the man on the run—Robert Redford in Condor, Matt Damon in Bourne. The big narrative question is “Will the hero unravel the mystery and save himself before the Secret Nefarious Forces pursuing him catch up and kill him?”

That’s the “A” story.

The “B” story is the romance that develops along the way as each protagonist (Redford in New York City and Damon all over Europe) kidnaps or recruits a woman off the street and, despite or perhaps because of his other troubles, becomes romantically involved with her.

In both movies, “A” and “B” stories intertwine as the female lead (Faye Dunaway in Condor, Franka Potente in Bourne) becomes swept up in the male hero’s drama and not only comes to care for him emotionally, but becomes an active partner and accomplice in his flight/adventure.

In both stories, there’s an early scene where the female comes emotionally unpeeled when the hero is violently attacked out of nowhere by a mysterious and obviously highly-trained antagonist who’s trying to murder him—and the protagonist, after successfully defending himself, compels his shaken female abductee/recruit to “snap out of it” and “get it together.” Both ladies do.

Not long after, in both films, hero and love interest literally become lovers.

Right after that, again in both movies, a scene unspools in which the female, now acting as the hero’s willing partner, enters the environment of the villain (in Bourne, a hotel in Paris; in Condor, the New York WTC offices of the CIA) to “recon the area” in preparation for the hero entering on his own.

We’re coming now to the All Is Lost moment.

Matt Damon and Franka Potente in “The Bourne Identity”

This is the point in the story, usually just before the Act Two curtain, when the hero finds himself ultimately alone. He has learned enough of the story’s secrets to know he must now enter the lair of the villain and face this devil down or die.

At this point, in both Condor and Bourne, the hero sends the female away, to protect her. (I can think of other stories—The Terminator, Avatar—where the love interest stays and fights alongside the hero.)

The key point, however, is that the love interest, whether male or female, has by his or her love, assistance, wise counsel, and belief in the hero, armed him or her with confidence and prepared him or her for the ultimate clash with the villain in the climax.

The classic fusion of A and B [writes Blake Snyder in Save the Cat!] is the hero getting the clue from “the girl” that makes him realize how to solve both—beating the bad guys andwinning the heart of his beloved.

In both Condor and Bourne, the hero wishes he could stay with the “B” story love interest. Both Redford and Damon send their lovers away reluctantly. The lovers, for their part, don’t particularly want to go either. They resist. In both stories, we sense, the lovers will never forget these men in whose company they have shared such dangers and with whom they have grown so close.

At the same time each hero knows (though he may not articulate this overtly) that he has been strengthened and prepared by the passage he has undergone with his unexpected lover in the “B” story and by her equally unexpected faith in him and belief in him. He now has the strength to “do what must be done” in the climax of the “A” story.

The “B” story has ridden to the rescue of the “A” story.