Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 46

September 14, 2018

Cheat Sheet

(From the archives: This one is brought to you straight from December 18, 2015)

Not that long ago I asked an acquaintance to cut an hour out of his day so that I could “run something by him.”

Franklin Leonard, Founder of The Black List, https://blcklst.com/

It’s important to point out that this acquaintance had a laundry list of accomplishments parallel to my own ambitions. He was a bestselling writer, a bestselling publisher, and a world-renowned speaker paid big bucks for the very hour I asked of him.

He is someone any of us would put in our top five of inwardly powerful people who’d figured out the secrets of how to live an authentic, generous life while also having a nice lifestyle too.

Hey, I wasn’t some slouch either. I had some serious successes and failures behind me as well. I wasn’t some amateur looking for an easy street. I had a fully fleshed out idea and just wanted to get his take on it.

At least that’s what I’d told myself.

You see I was so invested in my own world and my own desires that I couldn’t recognize the serious desperation underneath my ask.

I didn’t really want his “take” on my idea. I mean, “duh.”

What I wanted was for him to give me a cheat sheet. I wanted him to tell me how to attract an audience, and then manipulate that audience to do what I wanted them to do . . . buy my shit and come back for more.

What were the tricks to do that kind of thing? Obviously, this guy knew how to do that or I wouldn’t be traveling forty five minutes up the Saw Mill River Parkway . . .

He patiently listened to my idea, which I thought had great potential. Still do.

Hell, here it is. It’s no good sitting on my hard drive:

The Book Black List Pre-Origin Story

So after my thirty-minute spiel about my concept of a “Book Black List” and becoming the publisher dedicated to building one, the powerful acquaintance was quiet for about thirty seconds.

That doesn’t sound all that long a time, but just sit quietly for thirty seconds right now and you’ll see that it’s an eternity between two people.

When he finally spoke, here’s what he said:

“It’s a good idea. With dedication and enough time and money to buy a few breaks, it will work.”

That’s all? That’s it? That’s all this genius had to tell me?

I pushed him a bit… Well, if you were to start up something like that, how would you do it?

“How I would do it isn’t going to help you. I would not build that company because there are other projects in my life that I find more interesting. If this idea consumes you, I say plunge right in . . . but there is one question I’d ask of yourself before you jump . . . Why do you want to do it?”

I rattled off the usual “angry young man” responses (even though my youth had been spent tilting at a not too dissimilar windmill) . . .

To right injustices

To prove that the Gatekeepers are frauds

To expose the soullessness of corporate publishing

To make money in order to do “good”

He nodded and smiled and told me that unfortunately our time was up. As he walked me to the door, we shook hands and he said good luck and all the rest of the stuff you say.

As I stood uncomfortably waiting for the elevator, picking at a cuticle, he oddly stayed in the doorway leaning on the unhinged frame.

The arrival ding came and as I walked into the box I hear him say,

“What if you were given the permission not to have to right injustices or prove anyone wrong or build up a pile of money to do good? What would you do then?”

September 12, 2018

Lawrence of Arabia’s Motorcycle

We’ve been talking in this series about Ins and Outs—Opening and Closing Images in books and movies.

Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif in “Lawrence of Arabia”

We declared that the first rule of Ins and Outs Club is

The Opening and Closing Images of our story should resonate with each other. They should look as alike as reasonably possible.

An example we cited was the 1953 Western Shane, where the lone-rider hero (played by Alan Ladd) enters the Valley on the In and exits via the exact same path on the Out.

We said that the second rule of Ins and Outs Club is

At the same time, the Out should be as far away as we can make it in emotional and narrative terms from the In—to show the extent of the change that the hero has undergone.

Again citing Shane, we saw that our hero entered the Valley with hopes of changing his life and exited knowing those hopes would never come true.

Let’s assay a third rule of Ins and Outs Club:

Both the In and the Out must be on-theme.

Remember the opening and closing images from Lawrence of Arabia, starring Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif, directed by David Lean, screenplay by Robert Bolt and Michael Wilson?

The movie starts in the driveway of a cottage in Dorset. A youngish man (Peter O’Toole as Lawrence) readies his motorcycle—a 1935 Brough Superior SS100—and rides off down a narrow country lane. Fast. Faster. Recklessly fast. Suddenly the rider encounters bicyclists in the road. He swerves, loses control, the bike crashes.

Cut to St. Paul’s Cathedral. A major state funeral is in progress, apparently for the young motorcycle rider. Several dignitaries are approached for comment. They give contrasting statements, linked by the acknowledgment that the young rider was Someone Extraordinary.

That’s the In.

Here’s the Out.

Seventeen years earlier. The British and their Arab allies have defeated the Turks in the Middle East theater of WWI. Bedouin warriors, who under Lawrence and their tribal leaders have captured Damascus, have been superseded by regular British troops. They are leaving—going home to their tribal territories.

An open Rolls-Royce military car speeds along a desert road. The driver is a British sergeant. In back sits Lawrence. He is a colonel, in uniform.

The Rolls speeds past a detachment of withdrawing Bedouin fighters mounted on camels. The car’s passage drives the Bedouin momentarily off the road. We see Lawrence rise in his seat with concern. His eyes track the Arab warriors with obvious pain and regret, even heartbreak. “So,” says the sergeant-driver to Lawrence, “Going home!” He means that the prospect of returning to England must be filling his passenger with joy. But Lawrence makes no reply, only sinks into his seat in despair.

At that moment, a British dispatch rider overtakes the Rolls and speeds past, pulling swiftly ahead and racing into the distance. Lawrence’s eyes track the rider wistfully and, seemingly, significantly.

The rider is mounted on a motorcycle.

The theme of Lawrence of Arabia (among a number of others) is the burden of Being Extraordinary.

That’s what the movie is about, above and beyond Lawrence’s military achievements, the valor of the Arabs, the treachery of the Brits, etc.

The In and the Out of Lawrence of Arabia are absolutely on-theme. They work together like bookends.

Lawrence’s Brough Superior SS100

As Colonel Lawrence watches the motorcycle rider speed past him on the desert road and vanish into the distance, we in the audience cannot help but be called back to the opening image of the film. Did Lawrence kill himself deliberately seventeen years later on his Brough Superior? Was his reckless speed intentional, a consequence of no longer being a part of great events? Could Lawrence no longer endure having to live life as an Ordinary Man?

Again, as we said in previous posts of Shane and Alien and Good Will Hunting, the opening and the closing images alone convey a tremendous part of the story.

Each is on-theme, and each works with the other.

They are the movie in microcosm.

Together the In and the Out frame the narrative and contain its meaning.

September 7, 2018

One Leg at a Time

Early 2000s, a Big Five publisher bought an indie publisher.

I had a contract with the indie publisher. It was a large contract and I was less than a year into launching my business. I needed the work.

Unlike the indie publishing house, the Big Five publishing house had its own PR/Marketing team. It didn’t need me.

The contract was something I’d cobbled together when I launched my biz. (An opportunity popped up, I pivoted, and launched a company with little planning. A story for another day. . . .) It was void of language addressing the “what if’s.”

For example: What if my client cancelled the books in the contract?

Would I have the right to retain any of the fees, to cover the time I’d reserved to do the work?

Would I have to return any already paid fees?

I had to go to New York City to find out.

As was his way, Bob Danzig, my mentor of 20+ years (read “Thank You Bob Danzig“), opened his home and experiences to me the night before the meeting and then drove me to the train station the next morning.

I kept saying I was nervous.

Bob laughed. Actually, it was more of a chuckle. He did that a lot. I think it was something about the trajectory of his own life, of growing up in foster homes, experiencing hardships and seeing the true nature of people at an early age, and then becoming an office boy at The Albany Times-Union, then publisher of The Albany Times-Union two decades later, then CEO of the Hearst Newspaper Group and VP of the Hearst Corporation. He had met so many people along the way and had so many hardships at such a young age, that labels meant little to him. He didn’t equate greatness with a job title or location. He saw people for exactly what they were.

He smiled, and said, “Callie, they’re just like you. Pants go on one leg at a time.”

Of course I knew that. My father had been telling me that my entire life. They’re just people. They aren’t any better than you. They just happen to work in New York City.

Easier said than done.

I got wrapped up in the packaging.

Was I dressed okay? Did I look like a serious PR person, whatever that is? Or did I look country bumpkin? Was my hair okay? I don’t wear makeup, but maybe I should have?

And then I went into the meeting and it was fine.

The VP was a nice guy and honored the contract.

What was more important was that I knew my stuff.

Soon after, I hired a lawyer and had a contract developed.

One of the key clauses included?

Signing fees and cancellations.

There’s a non-returnable fee due on signing. This reserves time to do the upfront legwork. If the client cancels the project after signing, I don’t lose out on time spent.

If a client does cancel, there’s a clause related to prorated fees due up until the point of cancellation. This is similar to the doctor charging cancellation fees. If you cancel at a late date, I’m covered. I’m not left scrambling, trying to find work at the last minute to cover the loss of income.

I’m not offering legal advice here, but the cancellation clause is something I’ve mentioned to friends who work in other arenas. It’s saved me a number of times, when a last minute cancellation would have deep sixed my monthly inflow.

The other piece I’ve mentioned to friends is “one leg at a time.” New York City is a location, not a seal of approval. The staff at the Big Five publishers are the same. They’re just people.

What matters most is the work being done.

September 5, 2018

Self-doubt is Good

Last night for some reason I found myself thinking about my darkest hours as a writer.

The period lasted about ten years, more if I include a contiguous stretch where I was too paralyzed to write at all.

Was it Resistance? Was that the foe?

No.

The enemy was self-doubt.

Or put another way, lack of self-belief.

I may be wrong but I have a feeling that’s the Big Enemy for all of us.

In a way, Resistance is self-doubt. That’s the form it takes. That’s the weapon it uses against us.

But self-doubt somehow transcends Resistance. It stands alone. It was there before we ever thought of being writers or artists or entrepreneurs.

Self-doubt cripples us. It maims us. It renders us impotent. It cuts us off from our powers.

And yet, crazy as this sounds, self-doubt is good.

In The War of Art, I found myself writing this:

The counterfeit innovator is wildly self-confident. The real one is scared to death.

In other words, self-doubt is an indicator. It’s the proof of a hidden positive. It’s the flip side of our dream.

The more importance our dream holds for the evolution of our soul—that novel, that movie, that startup—the more Resistance we will feel to realizing it. The greater our level of aspiration (even if we’re unconscious of it), the greater will be our index of self-doubt.

A little over ten years ago I wrote a book called The Virtues of War. It was about Alexander the Great.

The book came to me like one of those tunes Liz Gilbert talks about in her great TED talk. The first two sentences just popped into my head. I had no idea who was speaking those sentences or what subject the book was about. It took months for me to be able to say, “Ah, this is about Alexander.”

The voice in those two sentences was his.

Meaning I was going to have to write this book in the first person, “as” Alexander.

If you’re a reader of this blog, you know that I don’t believe such epiphanies are accidents.

That book was coming to me for a reason.

My daimon was assigning it to me.

Why?

Because of all the individuals who ever advanced onto the field of aspiration (this was my conclusion a few years later), no one ever had LESS self-doubt than Alexander.

He was a king and the son of a king. His father Philip of Macedon was probably the greatest general who ever lived up to that time, until he was eclipsed by his son. Alexander’s tutor was Aristotle. Before he could walk, Alexander had internalized his father’s dream of conquering the Persian empire—the greatest in history. By twenty-five he had realized that dream.

In other words, the exercise of writing The Virtues of War was, I believe, my daimon’s way of helping me to overcome self-doubt. For two years I was like an actor immersed in a role. I had to internalize Alexander’s challenges and antagonists from his point of view. I had to narrate events not as I myself might have experienced them, but as Alexander did (or as close as my imagination could come to conceiving them.)

The artist’s daimon is a mighty ally.

It is working relentlessly, beneath the level of consciousness, to strengthen our resolve, to enlarge our self-belief.

What can we do to assist in this process?

We can keep working.

Keep studying.

Keep advancing our craft.

We can keep taking chances.

Keep stretching our boundaries.

Keep getting better.

Krishna told Arjuna, of the individual who faithfully follows a practice of meditation and devotion

Who walks his path beside me

Feels my hand upon him always.

No effort he makes is wasted,

Nor unseen, unguided by me.

Newton’s Third Law states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. That’s physics.

Here’s metaphysics:

For every measure of self-doubt we experience consciously, there is an equal and opposite measure of self-belief growing and enlarging itself unconsciously.

Our self-doubt is the inverse manifestation of our artistic dream.

The greater the one, the greater the other.

[I practically NEVER recommend books in these posts, but I’m making an exception for our friend Mark McGuinness’s “21 Insights for 21st Century Creatives.” It’s free at this link. It’s a real Swiss Army knife of all-around mental ammunition for those of us slugging it out in the trenches of this new century. Check it out!]

August 31, 2018

Getting to Your “Out”

I have a friend who is always the first to test new tech.

For example, when Google glasses were announced, she was tapped to give them a test run—and I got to hear the stories about strangers staring at her and random in-the-know techies asking if they could try on her glasses.

So, when she told me back in the 2006ish period that she was exploring alternative ways for colleagues around the world to meet, I wasn’t surprised to hear she was testing online conferencing.

The best bit of this story takes place after she chose the avatar to represent her, when the avatar was entering the conference room. Her mom chose that moment to walk by, glance over my friends shoulder, and then tell her, “Your avatar needs a better bra.”

Her mom’s a straight shooter, who has been in the tech world for decades, so what’s commonplace dialogue in their home, struck me as laugh-out-loud funny.

It’s also a story I was reminded of when I read Mark McGuinness’ new book 21 Insights for 21st Century Creatives (available for free via this link).

In the section titled “Stay Small, Go Global,” Mark tells the story of coming across an interview with Russell Davies.

He talked about launching a “global small business” with four partners, located in London, Amsterdam, Sydney, and New York. Every week, they held a weekly meeting inside World of Warcraft, where “we attack a castle or something, then chat about work.”

Mark thought that was “hilarious and inspiring in equal measure.” I thought the same, and wondered if my friend was hanging out in the same space—and if her mom was in there attacking castles, too.

The story also reminded me of why I like reading Mark’s work. He’s real. I relate to what he’s writing about. I take his words seriously, but find myself laughing and nodding my head in agreement, too.

If I was thinking in terms of the “ins and outs” Steve has been writing about these past three “Writing Wednesdays,” I’d say that Mark’s “out” is creating that connection with readers.

In his first “in and out” post, Steve wrote:

In the movie biz, there’s a question that studios and development companies often put to any screenplay they’re evaluating:

What’s the in? What’s the out?

What they mean is, “What is this script’s opening image and closing image? Do the two work together? Are they cohesive? Are they on-theme? Are they are far apart emotionally as possible?”

This is a really helpful series of questions for any creative person who’s trying to evaluate his or her own work. I use it all the time.

What’s the in? What’s the out?

These questions help if you’re designing a restaurant, writing a Ph.D. dissertation, crafting a speech for a corporate audience. They help for music, for dance, for art, for photography.

Toward the end of the same post, he wrote:

If you’re designing a restaurant, what’s the first impression people get when they enter? What’s the last thing they see when they leave?

What’s the first song on your album? What’s the last?

What’s the entry action in your videogame? What’s the exit?

In all of these examples, these “ins and outs” relate to one product—a movie, or a book, or a restaurant, or album, or videogame.

What if we apply that to a career?

Say Shane hasn’t been written yet, and I sit down and write the “ins and outs” Steve gave as examples in his first “ins and outs” post.

Well, okay, I have an extraordinary film, but . . . What if Shane was my first book or my first film, or whatever it is.

Why would anyone want to buy it?

What’s MY “in and out” in the bigger picture?

Maybe my “in” is writing a book and my “out” is becoming a New York Times Best-selling author.

Ok. Sounds good. Why not, right? Unknown to household name is a valid goal.

But what’s that look like? And why should anyone care?

Before people can care about Shane, they have to care enough to read something with my name on it. And, if I’m being honest, not even my parents care if my goal is being a best-selling author. They’ll love me no matter what. So if I can’t get my parents to care whether I achieve such a goal, how can I get complete strangers to get on board and read something by an unknown? How does it happen?

It happens by creating value over a long period of time.

I found out about Mark’s new book Wednesday afternoon. I read it, wrote this post, and had the post lined up by Thursday night. Why? Because Mark created value. Now I don’t care about Mark the same way that some people cared about Shane, but I connected with his work and with him, and will drop what I’m doing to help anytime. Mark isn’t the author who shows up whenever he needs help and he isn’t the guy making a million requests when he does show up. He’s the individual who creates value in his work and who is the real deal as an individual, too—and who gives back.

So how’d he do that? Didn’t happen overnight.

Mark’s been coaching creatives for 21 years. In his book he talks about some of the pitfalls creatives fall into. You might recognize many of them yourself—and if you don’t . . . Watch out for them.

When I look back on the almost ten years of “Writing Wednesdays,” I remember the days before Steve had an email list or even a blog, and the stumbling that occurred when the blog was first launched, and then everything that’s happened since then.

I wish I could tell you that your “out” will be easy to achieve, but it won’t. I honestly don’t even know what my own “out” is. I thought I knew at one point, but then life happened, and . . . Mom? Wife? Author? Entrepreneur? All of the above?

The only thing I can think of is a much-told story about Picasso, which might or might not be true, and which many of you have already heard. Supposedly, someone asked Picasso to draw on a napkin. Picasso did so, and then asked the person for a large amount of money to pay for the work. The shocked individual balked, and stated that it had only taken Picasso a few minutes to draw on the napkin. Picasso corrected him. It took him decades.

He had an extraordinary “in and out,” to the point that I’m sitting here retelling a story that I want to be true about him because it’s a good story and it’s how I want to finish this post.

The “out” takes a long time.

Check out Mark’s new book. It’s two decades of helping artists get to their “out.”

August 29, 2018

Blake Snyder on Ins and Outs

Here’s a quick In and Out from Good Will Hunting, i.e. the opening and closing images from the film.

Matt Damon and Ben Affleck from “Good Will Hunting”

The In:

Chuckie (Ben Affleck) drives his beat-up sedan down a residential alley and pulls up behind the ramshackle South Boston house where his buddy Will Hunting (Matt Damon) lives. Chuckie is picking up Will to take him to work. Clearly Chuckie has made this trip every day for years and expects to do it for decades into the future. Chuckie trots up the steps to the back door, knocks, Will answers and off they go.

The Out:

Chuckie drives the same junker down the same alley at the same morning hour and stops behind the same house. Chuckie trots up the steps to the back door and knocks, but Will is no longer there.

Final cut to Will’s own equally-decrepit beater (with Will driving) accelerating down the highway toward California.

As we said over the past couple of weeks re the opening and closing images of Shane and Alien …

Even if you haven’t seen a frame of the movie except these Ins and Outs, you get a pretty good sense of what the story is about—and how the hero (Shane, Ripley, Will) has changed from the beginning of the tale to the end.

Here’s Blake Snyder from Save the Cat!:

The opening image is also an opportunity to give us the starting point of the hero. It gives us a moment to see a ‘before’ snapshot of the guy or gal or group of people we are about to follow on this adventure we’re all going to take. Presumably, if the screenwriter has done his job, there will also be an ‘after’ snapshot to show how things have changed … a matching beat: the final image. These are bookends. And because a good screenplay is about change, these two scenes are a way to make clear how that change takes place in your movie. The opening and final images should be opposites, a plus and a minus, showing change so dramatic it documents the emotional upheaval that the movie represents. Often actors will only read the first and last ten pages of a script to see if that drastic change is in there, and see if it’s intriguing. If you don’t show that change, the script is often tossed across the room into the ‘Reject’ file.

We’ve been using movies as examples so far in this series. But novels and plays and even non-fiction can and should follow the same storytelling principles when it comes to Opening Statements and Closing Statements. The difference is a literary work may not necessarily start and end with a visual image. A film, of course, has no choice.

A book can start with a mood, with a voice, with an interior monologue. It can start with a philosophical statement.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness ….

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

In the beginning God created the heavens and the Earth.

Nonetheless it behooves us, brothers and sisters, whether we’re screenwriters or novelists or entrepreneurs or doctoral candidates, to ask ourselves (and to answer) …

What’s my In? What’s my Out?

Does our Opening resonate with our Closing like Shane, like Alien, like Good Will Hunting? Has real change occurred (for our central character or for our argument or our thesis) from the one to the other? Is our Out as far away, emotionally and narratively, as it can possibly be from our In?

August 24, 2018

George Peper, Bill Murray and Broderick Crawford

[This is another one from the archives, this time from January 6, 2012. A classic story.]

For quite a while now (almost two years), Steve Pressfield and I have been tossing drafts of one of his manuscripts back and forth. It’s just about ready to share. I think we’re on draft nine or ten, not sure. I bet Steve knows how many we’ve burned through, but he doesn’t bitch about it. He’s a pro.

Anyway, in a few months we’ll have a lot more to say about that book. For now I only bring it up because the concept of the book we’ve been working on reminded me of a story. And as Martha Stewart would say, “that’s a good thing.”

When I was at Doubleday, one of my responsibilities was to oversee the sports publishing program. The company had (and still does have) a leadership position in the arena. In addition to the usual sports fare that we’d acquire in proposal form from literary agents, we liked to be a bit pro-active and dream up projects that were unusual but potentially hugely commercial.

In the spring of 1998, I was on the phone with literary agent Scott Waxman. Scott represented and still does represent a terrific list of writers, many of whom I published back then. We were talking about one of his clients, the then editor-in-chief of Golf Magazine George Peper. George is as agile and entertaining a writer as Herbert Warren Wind but without the wind. The other thing I love about George is that he delivers what he promises, and usually on time to boot.

As just about all golf conversations eventually devolve into a quote off from the seminal work in the links-land oeuvre, Scott and I started talking about Caddyshack. Scott is an agent who is always closing. He’d be a great character in a David Mamet play. It was then that he one-upped my terrible “Gunga galunga, gunga—gunga galunga” Carl Spackler imitation and told me that George was friends with Bill Murray.

My heart skipped a beat. You have to understand that Bill Murray is impossible to reach. He doesn’t have an agent. He doesn’t have a manager. He doesn’t have a publicist. He doesn’t have an entourage.

But he’s not impossible. He walks around like a civilian, buys fruit on the street, and dresses exactly like a guy who grew up in Wilmette, Illinois would. Those who recognize him do so about ten beats after he’s passed them by.

“Was that Bill Murray?”

“Nah…couldn’t have been…you think Bill Murray would walk around in a Nyack tee ball T-shirt?”

I called George and asked him if he thought Bill would consider writing a book.

He didn’t say no.

Rather “it depends on what the book is about…he’s not going to write anything usual that’s for sure.” About five minutes into spit-balling an idea for Bill, George figured it out.

“You know, Bill’s brother Brian co-wrote the screenplay for Caddyshack. He and Doug Kenny (legendary National Lampoon founder) based it on the Murray brothers’ days as caddies in Illinois…Maybe Bill would want to write about that? We could call it CINDERELLA STORY…”

George pitched the notion to Bill in between grooving three irons at the Sleepy Hollow Country Club driving range… He didn’t say yes, but Bill agreed to have lunch to talk more about it.

After we ate—but not before I agreed to try the Zabaione Bill had ordered for his dessert—we worked out a deal.

Over the next several months, Bill faxed George and I bits and pieces of the book. Needless to say, the stories were formatted incorrectly. They were written single-spaced and every letter was uppercase. Somehow Bill had permanently locked the ALL CAPS button on his Pleistocene-age word processor. But, they were brilliantly Bill Murray…Inimitable and Proustian in their depth of observation. They were laugh out loud funny at first but had that hint of melancholia that has become Bill’s trademark.

The guy’s a natural writer.

George and I helped piece the scenes together with interstitial narrative tissue, but every word in the book was Bill’s. Trust me…we went over every word…again and again and again. I wake up some nights in a cold sweat thinking Doubleday’s managing editor is still waiting at the printer in Maryland for me to deliver the final manuscript.

I explained to Bill that we needed a photo insert to compliment the prose.

So he dumped what he found in his attic and collected photos that his brothers and sisters were kind enough to lend him into an old baseball bat bag. It was pretty full. He’s one of nine kids. He called me and George and told us to come over to 30 Rockefeller Center to look ‘em over. He was on Saturday Night Live that week and there was a couch in the host’s dressing room that we could use to sort ‘em out.

When I got there, Bill had a Lucinda Williams CD cranked up and was bobbing his head in rhythm to “I Lost it” while George sat a bit uncomfortably on the couch. George and I shook hands and Bill gave me a “what’s up” nod. Then he offered me the beverage of my choice as he handed me the bag of photos.

We never got to them.

Months later, we ended up laying out the insert sometime between 3:03 a.m. and 4:12 a.m. at a surprisingly comfortable suite at the Double Tree Hotel in Times Square. But that’s another story.

Cast member Tim Meadows came in to hang while he waited to be called to the stage for a hilarious The Ladies Man rehearsal. Bill made the introductions.

And then who walks in but Dan Aykroyd.

George and I nudged each other like a couple of nerds at a Star Trek convention. Soon Tim Meadows is asking the guys what it was like back at the beginning…when the show was just catching on. Who was the best host? Who was the worst? How did it work?

Murray and Aykroyd looked at each other probably like Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin used to…with a sort of “should we open the vault?” expression. Then they both said:

“Broderick Crawford.”

George, Tim Meadows and I settled in for the story. Bill and Dan share narration.

Midway into the second season of Saturday Night Live—1977—the creator of SNL, Lorne Michaels (just 32 at the time), hires Broderick Crawford as guest host for the March 19th show.

Which is weird.

Not crazy weird, but unexpected weird.

Crawford isn’t some schmoe of the street. With theatrical roots all the way back to a childhood career in Vaudeville, Broderick Crawford is an actor’s actor. He’s won a Best Actor Academy Award for his portrayal of Governor Willie Stark (based on Huey Long) in the film adaptation of Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. But by ’77, twenty-eight years of dust has collected on that Oscar.

Crawford is most famous for playing a character named Chief Dan Matthews in a 1950’s television series called Highway Patrol. Michaels was taking a calculated risk, betting that the old thespian would bring something fresh to SNL. Crawford wasn’t “with it” like Buck Henry or Robert Klein or George Carlin. And he definitely wasn’t Candice Bergan.

Rather Michaels gambled that Crawford would push the writers and the cast out of their comfort zones. And when a live comedy troupe was forced to play it fast and loose, something interesting usually happened.

In 1977, twenty-four-year old Dan Aykroyd and twenty-six-year old Bill Murray aren’t at the show to see if something interesting will happen. They need Saturday Night Live to succeed. This was way before Meatballs or The Blues Brothers or Stripes or Trading Places. These guys are two paychecks away from couch surfing their way back home to a job at the local lumberyard.

If the show is cancelled, there’s little chance that the two struggling comedic writer/actors will ever get another shot to appear in front of millions of people every week. They’d just be two more unemployed actors in New York. Worse than that, they’d be two ice-cold actors right off a failed TV show, not exactly the leading men movie studios vie to invest millions of dollars in.

In fact, Murray has already lost a big job. He was in the original cast of ABC’s quickly cancelled variety show, Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell. Now, he’s the “new guy” at SNL, fighting for survival…in search of camera time. He’d been hired to take the place of the one bona fide star the show had produced, Chevy Chase. He hasn’t come close to filling Chase’s shoes.

So in March 1977, Murray is struggling to find his voice. He isn’t making it on the show. But maybe Crawford as host will open up some sketch time… The big guy isn’t going to be able to play in every scene…

Could Bill write something that would best spotlight his skill set? Now was his chance to actually get it on the air.

Meanwhile Dan Aykroyd is pumped. With an encyclopedic knowledge of pop culture, especially cheesy 50s television shows, he’s thrilled that Broderick Crawford is hosting. As a kid in Canada, he loved Highway Patrol and he’s already sketched out a skit that puts him alongside the burly legend. Aykroyd thinks that with decades of experience under his belt in radio, stage, film and TV, Crawford is going to be great live from New York on Saturday Night.

But there’s just one problem. Broderick Crawford has a reputation as a drinker. Most on the cast and crew like to drink too (among other things) so they think he’ll fit right in. But drinking isn’t just a hobby for Crawford; it has become his vocation. To top it off, he’s scheduled to host the Saturday just after St. Patrick’s Day. Can you say “bender?”

Crawford misses the table readings. He misses rehearsals. He rarely even makes it to Studio 8H.

He spends most of his time holding court at a bar/restaurant called Barrymore’s (named after stage uber legend John Barrymore). It’s about thirty steps from Crawford’s favorite Broadway stage, The Music Box Theater and like any Irishman, Crawford’s feeling sentimental about the old days.

Production assistants are sent to coral him, but they never made it back. Crawford’s magnetism and “just one more” Irish charm are too much for them. He even gets SNL’s resident short-filmmaker Gary Weis to walk with him around town. They shoot a running monologue of Crawford serving up Blarney about the good old days when bartenders served booze in teakettles after last call.

Aykroyd finally corners Crawford and tactfully explained his concerns. If he isn’t in the studio, how will he learn his blocking? How will he remember his lines?

Crawford mumbles, “Don’t worry about it Kid. I’ll manage.”

Murray has even more at stake. He has finally written something that he thinks could get him out of playing supporting bit parts in other people’s skits. It could potentially establish him as a unique presence in the “Not Ready for Prime Time Players.” He was going to look the audience right in the eye and admit that he didn’t think he was being funny enough to stay on the show. But his bit isn’t scheduled to go up until halfway into the program.

If Crawford slurs his words and rocks like a drunk during his monologue, people will turn off their TVs. No matter how well Aykroyd or Murray perform, without a steady host at the helm, no one will see their work. Not good for them, not good for Saturday Night Live.

Saturday rolls around.

Crawford and Weis have put together a very compelling short film…a Vaudeville-era King Lear character (named Broderick Crawford) walks around a crumbling New York City contending with an unknowable future in an indecipherable present longing for a simpler past.

It’s funny, but melancholy, unique. It will fill critical minutes in the first half hour, enough to get to musical guests’ Dr. John, Levon Helm and Paul Butterfield’s all-star band’s first song. All they have to do is get Crawford through the monologue.

The show starts. Gilda Radner, Jane Curtin, Lorraine Newman and surprise guest Linda Ronstadt nail the cold opening. The rush from the band ensues.

But moments before his cue, Crawford is bobbing and weaving from drink, dazed. He’s so unstable, Michaels has agreed to place a high backed leather chair on stage to steady him and to have him skip the climb down the sets’ “loft” like steps. He just needs to wait underneath the staircase and walk the nineteen steps from backstage to center state, sit down, and then tell a short story about NBC in its radio days.

But the guy is pissed drunk. Aykroyd and Murray watch in horror.

But then, just as Don Pardo announces “Ladies and Gentleman…Broderick Crawford…” like a prizefighter with an ammonia capsule popped beneath his nose, just before the bell ring of a new round, the thousands of hours on the boards, on the sound stages and in the TV studios that Crawford has offered up for his craft in his fifty year career rally him.

The boys at Barrymore’s cheer as they watch their friend deftly navigate the bar’s television screen to tell a charming old story about being fired years ago by the very network giving him airtime now. Crawford is wonderful in the Highway Patrol skit and hits every mark.

Murray and Aykroyd finish the story.

“Pro…the guy was a Pro.”

August 22, 2018

Ins and Outs, Part Two

The first rule of Ins and Outs Club is

The Opening and Closing Images of our story should look as alike as reasonably possible.

The second rule of Ins and Outs Club is

At the same time, the Out should be as far away as we can make it, in emotional and narrative terms, from the In.

Sigourney Weaver in the original “Alien”

Last week we cited the opening and closing images from the 1953 Western Shane.

In the In, our hero, the gunfighter Shane (Alan Ladd), enters the Valley carrying aspirations for a better life. He hopes that in this new place he will be able to hang up his six-shooter and start afresh, be a normal person, maybe even find a wife and raise a family.

In the Out, Shane departs the valley by exactly the same route he entered. Only now he knows that that dream will not come true for him—not now, not ever.

In other words, this is exactly how an In and an Out should work.

The closing image resonates powerfully with the opening image—they are bookends really—but in emotional and narrative terms they are as far apart as they can possibly be.

Let’s consider another story, this time a tale of science fiction.

Remember the original Alien from 1979, starring Sigourney Weaver and Tom Skerritt, directed by Ridley Scott, screenplay by Dan O’Bannon, story by Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett?

Alien begins in deep space. Its opening image is that of a huge, black, industrial-looking spacecraft. A crawl identifies the vessel:

commercial towing vehicle “The Nostromo”

crew: seven

cargo: refinery processing 20,000,000 tons of mineral ore

course: returning to Earth

The camera now takes us inside the ship. The command bridge is dimly lit and eerily empty. We see the crew’s helmets meticulously in place at their duty stations, but the crew itself is nowhere to be seen. Apparently the ship’s computers are flying the vessel on auto-pilot.

Suddenly a comm terminal comes to life. A message of some kind rattles in from an external source.

Now the human crew comes into view. We meet them in a separate compartment of the ship, snugged into their hypersleep pods in suspended animation for the long voyage home. Apparently the incoming message contained an order to wake them up, as we now see the compartment’s lights come on and the transparent hatches of the sleep pods elevate open. One by one, the crew members emerge, stretch their limbs, and return to consciousness.

That’s the In.

The Out is a lone crew member (Sigourney Weaver as “Ripley”), accompanied only by the ship’s cat, “Jones,” settling in to a one-person hypersleep pod, about to set the controls that will put her back into suspended animation for the long voyage home.

Ripley is no longer aboard the Nostromo. The Nostromo is gone. Ripley is in “the shuttle,” the equivalent of a lifeboat for the lost ship. As Ripley programs the sleep chamber to take her under, she sends a final message to Earth Control:

RIPLEY

This is Ripley, last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off.

Exactly as with Shane, if we see only the In and Out and nothing more, we get a pretty good idea of what the full movie is about.

They key point is that, though Alien’s opening and closing images resonate and reflect each other—both involve a vessel in deep space, a human in a sleep chamber, and a message received or sent—they are light-years apart emotionally and narratively.

At the start of Alien the crew members, including Ripley, were unconscious literally and figuratively. By the end the others are dead and Ripley herself has woken up completely.

To what has she awoken?

First, she knows now that “the Company”—the unseen executive force that owns and controls the Nostromo—was willing to sacrifice the lives of the entire crew to get their hands on the Alien so they could study it for their Weapons Division. In other words, the world is corrupt and Ripley can count on no one but herself.

Second, Ripley has learned that she is far more capable than she believed herself to be. At the movie’s start, Ripley was second in command to Dallas (Tom Skerritt). She deferred to him. She was deferential as well to Ash (Ian Holm), the ship’s science officer, and even a little cowed by the maintenance dudes, Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton).

By the end of the film, Ripley has come into her own. She has survived, and even prevailed, when every other crew member has perished. Like Alan Ladd in Shane, she is not the person at the finish that she was at the start.

The In and Out of both films reflect the first rule of storytelling:

The hero must change as much as possible from the story’s beginning to the story’s end.

That’s the In.

That’s the Out.

August 17, 2018

Stories Are About Change

(Today’s post is pulled from the archives, from August 9, 2013, just about this time five years ago.)

In his wonderful book The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves, psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz tells the story of Marissa Panigrosso, who worked on the 98th floor of the South Tower of the World Trade Center. She recalled that when the first plane hit the North Tower on September 11, 2001, a wave of hot air came through her glass windows as intense as opening a pizza oven.

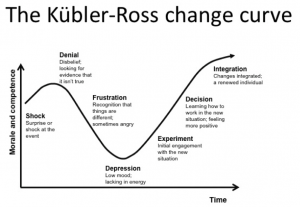

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s Seminal Change Curve is Story-Driven

She did not hesitate. She didn’t even pick up her purse, make a phone call or turn off her computer. She walked quickly to the nearest emergency exit, pushed through the door and began the ninety-eight-stairway decent to the ground. What she found curious is that far more people chose to stay right where they were. They made outside calls and even an entire group of colleagues went into their previously scheduled meeting.

Why would they choose to stay in such a vulnerable place in such an extreme circumstance?

Because they were human beings and human beings find change to be extremely difficult, practically impossible. To leave without being instructed to leave was a risk. What were the chances of another plane hitting their tower, really? And if they did leave, wouldn’t their colleagues think that they were over-reacting, running in fear? They should stay calm and wait for help, maintain an even keel. And that’s what they did. I probably would have too.

Grosz suggests that the reason every single person in the South Tower didn’t immediately leave the building is that they did not have a familiar story in their minds to guide them.

We are vehemently faithful to our own view of the world, our story. We want to know what new story we’re stepping into before we exit the old one. We don’t want an exit if we don’t know exactly where it is going to take us, even—or perhaps especially—in an emergency. This is so, I hasten to add, whether we are patients or psychoanalysts.

Even among those people who chose to leave, there were some who went back to the floor to retrieve personal belongings they couldn’t bear to part with. One woman was walking down alongside Marissa Panigrosso when she stopped herself and went back upstairs to get the baby pictures of her children left on her desk. To lose them was too much for her to accept. The decision was fatal.

When human beings are faced with chaotic circumstances, our impulse is to stay safe by doing what we’ve always done before. To change our course of action seems far riskier than to keep on keeping on. To change anything about our lives, even our choice of toothpaste, causes great anxiety.

How we are convinced finally to change is by hearing stories of other people who risked and triumphed. Not some easy triumph, either. But a hard fought one that takes every ounce of the protagonist’s inner fortitude. Because that’s what it takes in real life to leave a dysfunctional relationship, move to a new city, or quit your job. It just does.

I think it is because change requires loss. And the prospect of loss is far more powerful than potential gain. It’s difficult to imagine what a change will do to us. This is why we need stories so desperately.

Stories give us scripts to follow. It’s no different than young boys hearing the story of how an orphan in Baltimore dedicated himself to the love of a game and ended up the greatest baseball player of all time. If George Herman Ruth could find his life’s work and succeed from such humble origins, then maybe they could became big league ball players too.

We need stories to temper our anxieties, either as supporting messages to stay as we are or inspiring road maps to get us to take a chance. Experiencing stories that tell the tale of protagonists for whom we can empathize gives us the courage to examine our own lives and change them.

So if your story doesn’t change your lead character irrevocably from beginning to end, no one will really care about it. It may entertain them, but it will have little effect on them. It will be forgotten. We want characters in stories that take on the myriad challenges of changing their lives and somehow make it through, with invaluable experience. Stories give us the courage to act when we face confusing circumstances that require decisiveness. These circumstances are called CONFLICTS. What we do or don’t do when we face conflict is the engine of storytelling.

August 15, 2018

What’s the In? What’s the Out?

In the movie biz, there’s a question that studios and development companies often put to any screenplay they’re evaluating:

What’s the in? What’s the out?

What they mean is, “What is this script’s opening image and closing image? Do the two work together? Are they cohesive? Are they on-theme? Are they are far apart emotionally as possible?”

Brandon deWilde and Alan Ladd in “Shane”

This is a really helpful series of questions for any creative person who’s trying to evaluate his or her own work. I use it all the time.

What’s the in? What’s the out?

These questions help if you’re designing a restaurant, writing a Ph.D. dissertation, crafting a speech for a corporate audience. They help for music, for dance, for art, for photography.

And they help for fiction and nonfiction.

The classic Hollywood example of a great “in” and an even greater “out” comes from the 1953 Western, Shane, starring Alan Ladd, Van Heflin, Jean Arthur, Brandon deWilde and Jack Palance, directed by George Stevens and written by A.B. Guthrie, Jr. and Jack Sher from Sher’s 1949 novel (that he wrote as Jack Schaefer.)

Here’s the in:

A lone rider (Alan Ladd) descends from a mountain pass into a gorgeous Wyoming valley, circa 1870. In the audience we can tell from the rider’s fringed buckskin jacket, from his horse’s silver trimmed bridle, and from the six-gun on his hip that he is not your ordinary cowpuncher.

The camera cuts ahead to a small ranch-a-building (apparently a sodbuster’s claim), where a tow-headed boy of six named Joey (Brandon deWilde), looks up and sees the rider approaching. Even at a distance the horseman cuts a figure of romance—and the boy responds to it.

JOEY

Somebody’s coming, Pa!

Van Heflin plays Joe Starrett. It’s his little ranch that Alan Ladd is approaching.

JOE STARRETT

Well, let him come.

Now the out:

The same lone rider now exits the valley. It’s night. He’s been wounded, shot in the side after gunning down the three prime Bad Guys (including Jack Palance as the archetypal black-hatted gunslinger, Wilson), who were “putting the run on” the honest, hard-working sodbusters.

Shane clearly doesn’t want to leave. He is compelled by his own fate.

SHANE

Joey, there’s no living with a killing. There’s no going back from it. Right or wrong, it’s a brand. A brand sticks.

JOEY

But, Shane, we want you! Mother wants you, I know she does!

Shane tousles Joey’s hair in farewell. He rides out of the valley, the exact way he came.

JOEY

Shane, come back! Shane!

Even if we know nothing of what came between these two scenes (by which I mean the entire body of the movie), we get a pretty good sense of the narrative just from this “in” and this “out.”

What’s yours?

If you’re designing a restaurant, what’s the first impression people get when they enter? What’s the last thing they see when they leave?

What’s the first song on your album? What’s the last?

What’s the entry action in your videogame? What’s the exit?

[We’ll get into this subject of “ins” and “outs” a little deeper over the next few weeks.]

BTW, Shane was picked by the American Film Institute as the #3 US Western of all time, behind The Searchers and High Noon.

Myself, I would put it at Number One.