Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 49

June 1, 2018

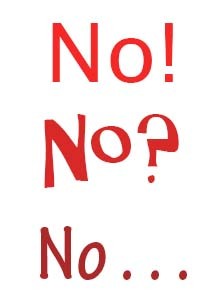

Getting Past No

(This post went up almost 4.5 years ago. Bringing it back for a rerun today.)

(This post went up almost 4.5 years ago. Bringing it back for a rerun today.)

I started this post Wednesday.

Thursday I read this from Seth Godin:

What “no” means

I’m too busy

I don’t trust you

This isn’t on my list

My boss won’t let me

I’m afraid of moving this forward

I’m not the person you think I am

I don’t have the resources you think I do

I’m not the kind of person that does things like this

I don’t want to open the door to a long-term engagement

Thinking about this will cause me to think about other things I just don’t want to deal with

What it doesn’t mean:

I see the world the way you do, I’ve carefully considered every element of this proposal and understand it as well as you do and I hate it and I hate you.

Thursday afternoon, Jonathan Fields’ “When No Means Go” arrived in my in box.

Seems a few of us have no on the mind this week.

As the third one in the ring . . . It’s the reaction to no that’s been on my mind.

A few years ago, a dying car sent me into a car dealership for a new set of wheels. While filling out the financial forms, the car salesman asked about my work.

“Publishing,” I replied.

“Oh, I have a manuscript. I’ll bring it in tomorrow when you pick up the car.”

I smiled politely and asked if I had signed all the right boxes.

Guess who drove her husband’s car to the dealership and then sped off after he went inside and picked up the new car. . . .

“Why didn’t you tell him no?” my husband asked.

“I didn’t want to hurt his feelings.”

“Isn’t it worse to lead him on and then not show up?”

“I didn’t lead him on. I didn’t say yes.”

“You didn’t say no, either.”

I’ve always had a hard time saying no.

1) I like helping friends, family, colleagues, causes . . .

2) I don’t like dealing with the response to no.

Jonathan’s piece does a great job of explaining his reasons for saying no, so I won’t go into them here. Read his post and know that bandwidth is in my vocabulary, too.

Instead . . . That reaction to no . . .

Earlier this year, I was told no in response to a project on which I’d been working. I’ve been told no before. Who hasn’t? However . . . The way this one arrived was a first.

My response ran like Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief, except without “bargaining” and repeat visits from “Denial” and “Anger.” I understand the no now, but at the time . . . I couldn’t get my head around the emotions. During the release of The Authentic Swing, when I responded with a few no’s myself, I got it.

With the release of The Authentic Swing, a number of readers assumed Steve was doing interviews. That’s what you do when you release a book, right? You do interviews. . . That’s not what the Black Irish team did, though. (read “Portrait of a Launch”)

And then Steve’s interview with Oprah followed, which buttressed the Steve’s-doing-interviews-now thinking—and I responded with more no’s and explained that the interview with Oprah wasn’t about launching a new book. The close timing for the launch of the book and the interview was a coincidence.

Around that time, Glenn Reynolds‘ producer contacted us about Glenn visiting Los Angeles. Would Steve have time to meet up? Glenn has interviewed Steve in the past, but they’ve never met in person. Yes, he replied and Glenn’s producer and I booked the interview.

Earlier in the year, Aubrey Marcus reached out to share his work with Joe Rogan and the possibility of scheduling an interview. Joe’s also located in the Los Angeles area, soo . . . If Steve was breaking for one interview. Would he do two, if we could book them close together? He did, a day apart, enjoying both, and then went back to work.

More requests came in—and I understood why. For the most part, those told no understood, but . . .

I read a post from someone who had been told no. He made a comment on his site, along the lines of (I’m paraphrasing here): “Pressfield’s booking person declined an interview with me a while back and, at the time, I bet that if Oprah called, he wouldn’t say no to her. Well . . Guess who did an interview with Oprah?” Then he went on to say he receives books from other authors every day who are interested in working with him and he’ll support them instead . . . (again, paraphrasing, based on my interpretation and memory . . . )

It was painful to read because I understood where he was coming from.

No feels like a personal rejection. He made the no about him. And then he made Steve’s yes to Oprah about him, too. Those answers weren’t about him. They were about Steve, his time, and his work.

Back to that post from Seth, which started this article, on what no doesn’t mean:

What it doesn’t mean:

I see the world the way you do, I’ve carefully considered every element of this proposal and understand it as well as you do and I hate it and I hate you.

It’s easier to write this than it is to put it into practice, but . . .

You have to move beyond no. If you don’t, it will devour you from the inside out.

For those saying no: You don’t owe anyone anything, but . . . be nice. Think about how you would want to be told no yourself.

In Steve’s case, he’s aware that people want him to say yes, which is one reason the “Ask Me Anything” audio series was launched. It’s an opportunity for Steve to connect with readers and answer their questions, but on his time. He’s done one hour-long session so far, with more to come. When I respond no on Steve’s behalf, or for other clients, or my own personal projects, I try to make the no’s shared as nicely as possible, thinking about how I’d want to receive them myself. I believe in the boomerang of Karma. What goes around comes around.

For those receiving a no: It hurts, yes, but . . . Back to that list above from Seth. More often than not, no is not about you. George Costanza might have used that old “It’s not you, it’s me” line to get out of things, but . . . In the real world, often no really isn’t about you. Move on with your art. Let it inspire you instead of being an anchor, weighing you down.

May 30, 2018

The Artist’s Journey, #16

Now, at this sixteenth installment of The Artist’s Journey, we’ve left the Apollonian mind behind and have entered the Dionysian. Way fun! To catch up on any posts you might have missed, use these links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11. Part 12. Part 13. Part 14. And Part 15.

76. WHAT IS THE ARTIST AFRAID OF?

The artist is afraid of the unknown.

She’s afraid of letting go. Afraid of finding out what’s “in there.” Or “out there.”

I’m not speaking here of unearthing within ourselves heretofore-unknown sordid, depraved, vile, degenerate urges. I don’t mean the fear of realizing that we’re all child molesters at heart or that we would have joined the Nazi Party if we’d lived in Germany in 1934.

The artist is afraid of finding out who she is.

This fear, I suspect, is more about finding we are greater than we think than discovering that we’re lesser.

What if, God help us, we actually have talent?

What if we truly do possess a gift?

What will we do then?

77. THINKING WITH YOUR OWN MIND

What exactly are we trying to accomplish on the artist’s journey?

We’re trying to think with our own minds, not with anyone else’s, and thus to speak in our own voice. On a deeper level, we are learning to bypass our front-mind, our ego-consciousness (and self-consciousness) and go directly to the next level, the unconscious, the superconscious, the Self, the Muse.

As in zazen the student is seeking to sit, i.e. meditate, without thinking. To empty her mind of all ego-spawned “thought”(which is really mindless chatter) until her consciousness becomes as clear as a glass of formerly-muddy water after the silty particles have settled to the bottom.

This is exactly what the artist does when she sets her brush to the canvas.

It’s what the musician does when he places his fingers on the keys.

The artist and the writer enter the Void with nothing and come back with something.

78. THE VOID

How does a writer write a scene, or a choreographer design a dance sequence?

They start with nothing. An intention only.

They reach into the void and they pull out a sentence, a first step.

They go back in, like James Spader reaching through the liquid-metallic membrane in the movie Stargate. They pull their arm back out with the next sentence or the next dance move.

Now they have momentum. A tiny bit anyway. They feel a glimmer of courage.

They reach through the membrane again, this time up to the elbow.

Next: the shoulder.

They step all the way through.

Their hearts are hammering.

It’s terrifying releasing one’s hold on the known.

79. THE OTHER SIDE

What’s on the far side of the Stargate?

We are.

The writer and the dancer and the filmmaker ourselves.

Our selves wait there, breathless, trembling, pulling on the ego-writer and ego-dancer and ego-filmmaker with all their strength.

“Come through! Hold out your hand! Here, take this!”

80. MY OWN EXPERIENCE

From the moment of turning pro (my “dishwashing moment” in New York City), it took me nearly twenty years of full-time trying before I could write in my own voice.

I was close in those two decades.

I had moments.

But I could never really do it.

I tried everything to break through. I tried trying super-hard. I tried giving up. I employed psychology. I used reverse psychology. I was like Nuke LaLoosh wearing women’s undergarments beneath my Durham Bulls uniform.

Anything to make myself STOP THINKING.

I watched thousands of movies, read hundreds of books. I literally copied pages from writers I loved, trying to find a voice, any voice.

Was there an Aha moment?

Yes, and it came in the way I least expected.

81. WRITING IN CHARACTER AS SOMEONE ELSE

I was fifty-one when I started writing The Legend of Bagger Vance. The narrator of the book was a physician in his mid-seventies. I realized right away that this character, whose voice I was going to write in, was smarter than I was.

How could I speak as him?

How could I know what he knows?

It seemed functionally impossible.

I stuck my hand through the stargate and it worked.

I found my voice by writing in somebody else’s.

I was absolutely amazed when it happened, and when it continued to happen, day after writing day.

In my second book I wrote as another character, completely different from the first.

In my third, I wrote in the voices of three characters, each one different from the others and from all others that had come before.

It worked.

It worked seamlessly and effortlessly.

All at once, I could do it.

82. THE AMAZON MIND

In Last of the Amazons, I tried to imagine on the page the ancient race of female warriors.

Here’s a description of the Amazon mode of thinking, offered by one of the characters in the book, a young Athenian who has traveled to the Amazon homeland near the Black Sea and lived for a time among this legendary all-female culture.

The Amazons have no word for “I.” The notion of the autonomous individual has no place in their conception of the universe. Their thinking, if one could call it that, is entirely instinctual and collective. They think like a herd of horses or a flock of swallows, which seem to apprehend and respond with one mind, acting intuitively and instantaneously in the moment.

When an Amazon speaks, she will pause frequently, often for long moments. She is seeking the right word. But she does not consciously search for this, as you or I might, rummaging within the catalog of our mind. Rather she is waiting, as a hunter might at the burrow of her quarry, until the correct word arises of itself as from some primal spring of consciousness. The process, it seems, is more akin to dreaming than to waking awareness.

To our Greek eyes, this habit of pausing and waiting makes the speaker appear dull-witted, even dense, and many among our compatriots have lost patience in the event or, concluding that these horsewomen of the plains are a race of savages, have given up entirely on attempting to communicate with them.

To the Amazons, of course, it is we Hellenes who are the witless ones, whose “civilized” consciousness has lost access to the well of wisdom and sense upon which the plainswoman readily draws, and who as a result are cut off from the immediate apprehension of the moment, immured within our own narrow, fearful, greedy, self-infatuated minds.

The Amazon mind as imagined in this passage is not far off from the artist’s mind when she is at work.

May 25, 2018

How An Agent Figures Out Her Pitch to Publishers

From www.storygrid.com…some things never change…

It’s 1996.

Tina Bennett is a junior literary agent at Janklow & Nesbit Associates, an Aston-Martin level New York literary agency. She’s finished her after-work beer with her colleague Eric Simonoff and heads home energized.

She now has a step-by-step mission.

Per Simonoff’s generous counsel, here is what she’ll need to do to best represent Malcolm Gladwell’s Tipping Point book project.

Target a short list of editors from the brand name publishing companies with the best reputations for publishing high-end Big Idea nonfiction. The publishers of books like The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (Simon & Schuster); Futureshock (Random House); Megatrends (Warner); Influence (William Morrow/HarperCollins); The Fifth Discipline (Doubleday) etc. She’ll use the agency’s Editor/Publisher directory to come up with the names and houses. She’s already run her list by Simonoff and he thinks it’s a good start.

Hone a verbal pitch, one that she would use to describe the project to those editors over the phone…the pitch that will induce them to ask to be included in the submission.

Get some face time with the heads of her agency, Mort Janklow and Lynn Nesbit, to run the pitch by them and then ask their advice about her plan.

The next day is a Friday, a good time to pop her head into J&N’s Park Avenue office doorways with a “do you have a minute” expression on her face. Bennett knows that any of that week’s submissions have already been messengered to their respective editorial prospects. For all intents and purposes, the work week has ended.

Fridays are paperwork and “blue sky” thinking days at literary agencies, the come down from the Monday through Thursday call logging for new projects and follow-up check ins for the previous week’s. Friday is the day to exhale and regroup. Take off the tie and wear the jeans.

This was the era of hard copy, when submissions were literally printed on paper and stuffed into agency boxes with pitch letters atop. Every agency had its own distinctive box. And Janklow & Nesbit’s were the perfect shade of Strathmore Ivory, elegant with an emanating air of detached excellence…as if one was privileged to have been chosen to cast one’s eye upon the brilliance that lay within. Whether you were capable of understanding and appreciating said brilliance of little matter. Someone would and they’d make it a bestseller. With or without you, the die had been cast.

At publishing houses, the boxes would arrive Friday afternoons. Just before the return of lunching editors soon to pull together their weekend reading. To have a foot’s worth of fresh manuscript chum from second tier chop shop agencies awaiting your push through the glass door after yet another sup at Cafe Un Deux Trois was one thing.

A J&N box with you name elegantly scribed upon it was something else entirely.

It meant you were a player.

Many editors would let those high end boxes sit on the receptionist’s desk all afternoon in the hopes that their publisher would walk by and see that they were getting in the good stuff. Better for the boss to discover your gravitas with their own eyes than to have to clumsily and loudly drop references to how “I’ve got a first novel in from Janklow” to no one in particular as you walked by the publisher’s private and ocupado facilities.

My first publisher was one of those with zero patience for small talk so the bathroom strategy was unfortunately one’s only option. She was not one for the schmooze. But without fail, she’d step into my elevator car at a quarter to five on a Tuesday with me holding a baseball mitt, wearing shorts and sunglasses. With no reading tote anywhere near my person.

“What do you know?” she’d ask.

I never really knew how to answer that question. Was it her way of saying, “what’s up?” “How you doing?” “Good day?” Or was she literally asking me what I knew?

I’d blurt out “Not much.” To which she’d shrug and lament, “we all have our problems.”

Seriously. Those are the sum total of words we exchanged for three years.

Ugh. Still get panicky thinking about it.

Let’s get back to Tina Bennett the night before she’s going to ask her bosses about her list of editors to send The Tipping Point proposal.

After readying a four-cup coffee drip to keep her sharp after the Hefeweizen with Simonoff, Bennett picks up the phone and calls Malcolm Gladwell to nail down the pitch.

Is there anything he left out of his New Yorker piece…what he thinks might make for a bigger treatment of the tipping point idea?

Before Gladwell can respond, she gives him the reason why his answer is so important.

What she is going to have to do is shoot down the Pavlovian “magazine article does not a book make” editor argument right from the start.

So why exactly is “the tipping point” a bigger idea than just a way to look at the controversial broken windows criminology theory and of how people get the flu?

Like what are its first principles?

What is the single simple thing about the tipping point that would appeal to the largest possible audience?

On the other end of the phone, Gladwell is practically having an out of body experience.

I mean he’s had this idea marinating in a sardine can in the back pantry of his mind for over ten years. By 1996, he’s seeing the tipping point pattern in everything. From what made the new Japanese restaurant down the block from his apartment successful to how Paul Revere was able to spread “The British Are Coming” message to start the American Revolution.

Gladwell charts his vision.

The first principle of the tipping point is that it is explains why and how ideas and products and movements and behaviors spread. Anyone interested in figuring out how things become incredibly popular, adopted almost magically/unconsciously by millions and millions of people will want to read a book length version of the tipping point.

He’s animated now, realizing that what he just said may actually be true. It took Bennett to get him to voice it, now that he has, he’s on a roll.

The tipping point explains not just the practicalities of engineering mass consent about an idea–all that Noam Chomsky stuff. But how to actually transform the adoption of an idea into a behavioral response. To know how to tip something is to know how to get someone to not just “think” something, but to actually “do” something.

Knowing about the tipping point, studying it, and putting the principles behind it into action can transform lives.

It’s lightning in a bottle.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but anyone baffled by how people like Jim Jones or David Koresh or Adolph Hitler for that matter were capable of getting legions of people to follow their every dictum will get something life changing out of a book length treatment of the tipping point.

Bennett interrupts to say that going down that very dark hole into the techniques of fascist brainwashing isn’t something many people would want to read about in their spare leisure time.

Gladwell agrees. Let’s go to the opposite pole then. To the positive.

The key thing to get someone excited about the big idea of this book, especially an editor at a publishing house, is probably in how the tipping point relates to commerce.

Like how do you create a marketing program for a product capable of mass adoption? From zero to millions sold?

This will be a global goal of the book…to tell readers how they can use the timeless principles of the tipping point to create positive change. From unknown to wildly popular. Be it a pair of brown suede shoes or even a mind-numbingly repetitive television show on basic cable.

So Gladwell tells Bennett that he will write more about good stuff than bad stuff. He’ll write about how products go from invisible to being de rigueur. How infections are contained. How crime is reduced. How educational television works.

So theoretically, someone who buys the book will feel like they’ll be able to practically put in place the things necessary to create an irresistible product or movement.

Bennett, now taking copious notes, asks, “So, how do you?”

Gladwell then tells her that he’s been thinking about that. He thinks you need three things in order to get something to tip. You need the right kind of information that is appealing enough or “sticky” to inspire others to share. You need the right kind of people to spread the information. And you need the right timing or context for the message and messengers to operate in.

Bennett needs to wrap it up. Okay. Now there’s a general three-part structure to the book. The message, the messengers, and the environment in which they incubate are what give rise to tipping points. Beginning, middle and end. We’ll frame the book with a killer prologue and epilogue and we’ve got a global structure that any book editor will embrace. This goes far beyond the magazine piece. Is that it?

Pretty much, Gladwell confirms.

Great, I’ll boil this down and talk to Mort and Lynn tomorrow says Bennett. Anything else?

Oh, yeah, says Gladwell, there’s this…

May 23, 2018

The Artist’s Journey, #15

Here in our fifteenth week of this serialization of The Artist’s Journey, we’re finally getting into my favorite part—the airy-fairy part. I can make no scientific claim to anything put forward in “Book Six The Artist and the Unconscious.” It’s all personal and idiosyncratic, just stuff that I believe is true (though I can’t prove it) from my own experience. From this point to the end of the book, that’s what’s coming. To catch up on any prior posts, click these links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11. Part 12. Part 13. Part 14.

69. INDEX OF SKILLS, CONTINUED

The artist learns how to help others and how to be helped. She learns how to steal and how to give away.

She studies the marketplace and comes to understand it (as much as it can be understood.)

She acquires perspective on herself and her work and the place of her work within the field of her contemporaries and of those who have gone before.

She studies the work of the masters who have preceded her. She learns to appreciate them and to respect the gifts they have bequeathed to her.

She acquires humility and she gains self-belief.

She learns to self-motivate.

To self-validate.

To self-reinforce.

And to self-evaluate.

She has become a professional.

Now when someone asks her what she does, she answers without hesitation, “I’m an artist.”

70. THE ARTIST LEARNS TO COMMIT FOR A LIFETIME

It’s easy for Bob Dylan or Neil Young to say, “I’m never going back to work in the bean fields.”

What about you and me?

Can we say it and mean it?

71. “BUT WHERE’S THE MADNESS, ROSE?”

Now we come to the mystical level. The right brain. The Dionysian.

What are the stages of the artist’s journey on this plane?

B O O K S I X

T H E A R T I S T A N D T H E U N C O N S C I O U S

72. THE BLANK PAGE

We hear (and we know, ourselves) of the terror that writers experience when confronting the blank page.

Rather than face this, they will delay, dilate, demur, procrastinate, rationalize, cop out, self-justify, self-exonerate, not to mention become drunks and drug addicts, cheat on their spouses, lose themselves on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, and in general destroy not only their bodies and minds but their souls as well.

Why?

What’s so scary about an 8 1/2 X 11 sheet of uncoated bond?

73. ENCOUNTER WITH THE UNCONSCIOUS

What’s scary is that, in order to write (or paint or compose or shoot film), we have two choices:

We can work from our ego-minds, in which case we will burst blood vessels and suffer cerebral hernias, straining only to produce tedious, mediocre, derivative crap.

We can shift our platform of effort from our conscious mind to our unconscious.

Can you guess which one we’re most terrified of?

74. THE MISNOMER OF THE UNCONSCIOUS

The Unconscious (to use the term as Freud originally defined it) is unconscious only to us.

We are unconscious of its contents.

But the Unconscious mind is not unconscious to itself or of itself.

The Unconscious is wide awake.

It knows exactly what it’s doing.

(And it’s pretty pissed off at being called “the Unconscious.”

75. THE SUPERCONSCIOUS

Instead let’s call it the Superconscious. That’s what it is.

The superconscious is that part of our psyche that knows where we put our keys when our conscious mind is certain we’ve lost them.

It’s that part of our brain that divines, in .0001 second, that that very attractive, bewitching, charismatic new person we just met is big-time trouble.

It’s that part of our mind that wakes us at precisely the minute we set our mental alarm clocks to.

It’s that part of our consciousness, if we’re a wildebeest, that guides us infallibly from the Serengeti to the Maasai Mara, or, if we’re a Monarch butterfly (with a brain the size of the head of a pin), three thousand miles from eastern North America to the Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico, even though not a single butterfly in the migration has made the trip before.

The superconscious is that part of our psyche that dreams, that intuits. According to Jung, it’s that part that lies adjacent to and is linked with the “Divine Ground.”

The superconscious is the part of our mind that speaks in our true voice, knows our true subject, and makes decisions from our true point of view.

The superconscious is the part of our psyche that enabled Einstein to conceive the Special Theory of Relativity and Steph Curry to hit nineteen three-pointers in a row with an opponent’s hand in his face on every shot.

Tolstoy didn’t write War and Peace. His superconscious did.

Picasso didn’t paint Guernica. His superconscious did.

Trey Parker and Matt Stone didn’t create South Park, their superconsciouses did.

I’ve got a superconscious, and so do you.

Our problem, you and I, is that we don’t know how to access it or, if we do, we’re too terrified to take the chance.

The artist’s journey is about linking the conscious mind to the superconscious. It’s about learning to shuttle back and forth between the two.

May 18, 2018

Thank You Mr. Walsh

One of the best friends I’ve ever had lost his father this month.

Death proved itself a slingshot, pulling me back through the decades to think about the few times I met his father and then catapulting me forward to question what I’m doing today.

Jay and I met at Emerson College. I was climbing the stairs in front of him and tripped. He laughed at me. For a split second I thought he was an asshole—and then realized that I would have laughed at me, too. The friendship started there. Lots of talking and philosophizing and listening to Dave Matthews during the school year and then summers full of letter writing. I still have his letters. He’s that kind of friend. A deep soul. Honest. Kind. Smart. Funny. Creative. One of my biggest regrets is that I failed as a friend on numerous occasions and then after college did a crap job of keeping in touch.

Then his father died and I realized how many decades had passed.

I met Jay’s father, Bob, on Cape Cod, where he and the rest of the family lived. Getting there from Boston was just a cheap Peter Pan bus ride away, so I jumped at the chance the times I was invited out there.

When I met Bob, I couldn’t stop smiling. He’s the guy who dressed up as Santa Claus at Christmas and could swing it without having to add a fake beard or redden his cheeks. He just had that natural happiness going for him. Endearing is the word that comes to mind as I type this.

The thing I remember most about him is that he lived out loud. He was a part of the world, not hiding from it. He loved his family and friends. He loved music. He loved to laugh. He was was there. He gave as good as he got.

The first time I met him, he and his wife were spending the weekend on the beach in their camper and Jay and I came along for the ride. Bonfires and laughter followed. At the time, I remember thinking, Life can’t get any better than this. This is what it’s all about.

And then I graduated and started working and got married and worked more and had kids and worked even more — and in the quest to do it all I lost a bit of myself. I lost that girl on the beach who could be made happy by little more than salt air and laughter.

I admire Bob even more now because I know that being happy and having friends and a close family isn’t something that comes easy, especially when you have a job and other responsibilities — yet it was evident how much he was loved and how much he loved those around him.

We talk about doing the work all the time on this site, in terms of writing books, opening businesses, being an entrepreneur, but there’s a piece that’s missing.

Doing the work involves connecting, loving, laughing, too. It involves living out loud. If you don’t know these things, how can you write about them or paint them or sing a song about them? Our greatest inspiration surrounds us.

I had a brief glimpse of Bob tapping into that world and saw the joy it brought him.

That girl on the beach is working on making a comeback. She has Bob as her North Star. What’s important isn’t the number of followers or fans. It’s what and who and how you create and love and live. It’s about living out loud.

May 16, 2018

The Artist’s Journey, #14

Continuing this serialization of The Artist’s Journey. For the past few weeks we’ve been talking about the professional skills the writer, the painter, the actor, the filmmaker develop on her journey. Pretty soon we’ll be getting into my favorite part, the deep stuff, the crazy stuff, the stuff you can’t prove but that you know is true. If you’ve missed any of the prior posts in this series, catch up here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11. Part 12. Part 13.

62. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO HANDLE PRAISE

Before, she would have been seduced by that rave in The New York Times. It would’ve gone to her head. She would have become insufferable.

The ordeal of her real-life hero’s journey, however, has taught her humility. “Yeah yeah,” she thinks as she assesses the critic’s over-the-moon adulation. “And what’ll you write next time?”

She accepts the plaudits with gratitude, then goes back to work.

63. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO HANDLE PANIC

I interviewed a test pilot once. He told me that over the course of his career he had put more than two hundred and fifty airplanes into deliberate tailspins to test the crafts’ physical limits.

“Of course you are scared,” he said. “But you understand what causes a tailspin. And you know how to pull out of it.”

The artist learns that panic strikes at that point in a project when a creative breakthrough is imminent. Panic is Resistance pulling out the stops to keep us from ascending to the next level.

The artist, like the test pilot, learns to stay cool and keep flying the plane.

64. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO GIVE UP

In Eugen Herrigel’s 1953 classic, Zen in the Art of Archery, the author, a deeply serious student of Zen Buddhism, travels to Japan and enrolls in an academy of archery.

In this school the physical act of drawing the bow and loosing the arrow (as also in other schools with meditation, martial arts, the study of calligraphy or flower arrangement or mastery of the tea ceremony) is not undertaken for its own sake but as a portal to insight, to enlightenment.

For Herrigel, the process came down to one challenge: the simple act of releasing the bowstring.

Herrigel could not get it right.

He would draw the bow with the fingers of his right hand (in Japan this act is performed with the thumb and forefinger) pulling the string back to its full stretch. Then he would release the string, shooting the arrow toward the target.

Hundreds, thousands of times Herrigel attempted to do this, but always his instructor found fault with his technique.

“The bowstring,” declared Herrigel’s teacher, “must release itself without your will or consciousness. You are thinking too much. You are trying too hard.”

Herrigel was instructed to hold the stretch until the string escaped from his fingers by itself, so that the release came to him as a surprise.

The setting for the student of an unsolvable riddle, a koan, is at the heart of the teaching of Zen.

The idea is to exhaust the aspirant’s will, to extinguish his ego, to break down his stubborn, prideful mind and his compulsion to control the event. The moment of breakdown is the moment of breakthrough.

But how do you do it?

How do you try and not-try?

How do you do and not-do?

How do you find your subject?

How do you find your voice?

How do you find your point of view?

65. THE ARTIST LEARNS TO GO BEYOND WHAT SHE KNOWS

The artist can feel it when she’s working beyond her limits. Her blood thrills. She loves it.

This is the rush of working in the arts. It’s why she came to this dance.

We can sense it, you and I, when we’re playing it safe. And we know, too, when we’ve stepped out beyond the light of the campfire.

Out there is where all good things happen.

66. THE ARTIST LEARNS TO BE BRAVE

Elite warriors are trained to “run toward the sound of the guns.”

The artist lives by that principle too.

What project terrifies her most? What work is she certain she can never pull off? What role will push her past her limits, take her into places she has never gone? What journey will carry her off the map entirely?

The artist hears the guns. She feels the battle lines inside her and she senses which quarter of the field terrifies her most.

She goes there.

She runs there.

67. THE ARTIST LEARNS TO KEEP THE PRESSURE ON

Every work resists you. It wrestles against you like an alligator. It kicks and bucks you like a bronc.

The artist learns to “sit chilly,” as the renowned equestrienne Sue Sally Hale used to say.

He answers the bell every round. He refuses to go down. He will keep the pressure on week after week, month after month, year after year.

He knows the oak will fall.

The enemy will tire.

The gator will roll over and quit.

68. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO KILL

The struggle between the artist and her work is a duel to the death.

One of them is going to surrender.

One of them will go belly up.

May 11, 2018

How Literary Agents Target Acquisitions Editors

To follow up from the last post from www.storygrid.com, here is a description of how literary agents think about who to send a particular project at a particular publishing house…

So a good agent understands how editors think…specifically, how they sort submissions.

Let’s take a look at Editorial Principle Number One from the last post, “Don’t Even Think About Reading Unsolicited Submissions.”

How does this knowledge translate into an effective sales approach?

To avoid being thrown into the slush pile and/or being immediately handed off to an assistant, the first thing effective agents understand is that they have to personally connect with the editors targeted for their pitch.

If she can’t get the editor on the phone or respond to an email…game over.

Wait a minute. Back up. How do agents target editors in the first place?

Here’s how. Every literary agency or independent agent has a file. They call it the Editor/Publisher file. This file contains an up to date listing of all the editors in the publishing house, plus their particular specialties.

When I was an editor, my entry probably read something like this,

Doubleday

Coyne, Shawn: Senior Editor

Fiction: Thriller, Mystery, Military, Historical, Sports

Nonfiction: Sports, Outdoor Adventure, Military, Public Affairs, Science

6-10 books a year.

When an agent has a project ready to go, the agency will hold an informal meeting (or the agent will just go from office to office and spitball ideas with his colleagues) and figure out which editor at each house would be best for the project.

This happens with every single submission.

Why?

Well, editors move around a lot. At least they did in my day. And editors’ adapt to what publishers’ want. If a great job becomes available that requires a passion for needlepoint, you’d be surprised at how many great editors with no track record publishing needlepoint books actually have a secret obsession with the craft… So just because an editor concentrates on Fiction at one house, he may be doing only Nonfiction at another.

In order to achieve a sizable raise, especially when you are a young editor, one has to be lured to another publishing company. What would happen is that a friend would hear about a job opening at a rival house and tell you about it. You’d speak to other friends and let it be known that you’d be open to making a move.

The publisher or editor-in-chief of the rival company looking for new blood would hear about you through the scout/insider information network and call you to arrange a clandestine meeting to see if you were a good “match” for them. This usually involved an early morning breakfast at a neutral venue (like a coffee shop in a cheesy tourist hotel) where no “publishing people” were known to frequent.

If your current boss found out you were interviewing, it was bad form. Thus the necessity to eat a bad bagel at the Radisson on 38th and Park at 7:30 a.m.

If you passed muster, the rival publisher made you an offer, usually in the afternoon after your breakfast meeting. But there’d be a time clock attached to it. That is, they’d want to know your decision by end of the next business day or the offer would be rescinded.

Only the upper echelons of editors are under contract, thus the little guys are free to move around as free agents. When you’re a young editor, you long for the security of a contract. When you’re an older editor with a string of hits locked into a salary that is a pittance to what you are bringing in to the company, you long for the freedom of youth.

What you want when you’re young is the very thing that you wish to be rid of when you’re older. C’est la vie.

The offer from the rival publisher would be a sizable increase in salary and a raise in job title. So the “associate editor” back then making $25,000 a year would be offered a job as “editor” at the rival house for $35,000 a year. The money for editors is terrible. Especially for young editors. It may be $35,000 to $45,000 today for the same move. Maybe.

Before accepting the offer, you would arrange a meeting with your current boss and give her your notice.

Now, if you were a valued part of the company and the editor-in-chief or publisher thought it would be a big loss to lose you, they’d “counter-offer” to keep you, which would usually mean they’d match the money and job title and make a bunch of promises for your future.

Few publishers increase the terms of a rival offer, especially for a young editor, because the last thing they’d want is to get into a bidding war for a baby editor.

[Years ago, I was the editorial prize in a bidding war between my two favorite houses, which was wonderfully exciting until I realized that wherever I went, the pressure for me to perform immediately would be extreme. It was worse than I could have imagined but that’s another story.]

The crisis question for an editor in this position, having two equal offers, is “do I start over somewhere else” or “do I stay here and feel good about letting my bosses know that another publisher thinks I’m good at what I do.” Obviously, it depends on the editor making the decision.

In my case, what I did was completely stupid.

When I was a baby editor, I bullheadedly walked into my editor in chief’s office and told her, with spreadsheets and slick rhetoric, that from my own private analysis, I was worthy of a promotion in title and a commensurate raise in salary.

She then asked me if I had an offer from another company. I earnestly told her I didn’t. That I thought the way people were promoted in the industry (sneaking around and getting offers to throw at their bosses) was inherently corrupt and that while I could have done that, I didn’t think it was “honorable.”

Barely stifling a laugh, she proceeded to detail why I wasn’t worth what I thought I was. But because I was so “honorable” and had potential, she agreed to promote my title and to award me an increase in salary that was $1,000 less than what I’d asked for. Which reminds me of that wonderful line in the movie version of Fast Food Nation delivered by Bruce Willis “There’s always been a little shit in the meat…you’ve probably been eating it your whole life.”

What I’d done was a huge triumph. I’d gotten everything I wanted but a lousy $1,000, which was a small price to pay for my editor-in-chief to maintain a compelling management Story to tell for herself. And better yet, a Story to dine out on with her boss the publisher.

What would that story be?

If challenged about why she promoted the angry young man who worked in the office that had previously been a coat closet, she would simply explain that she’d put him in his place by dumping a triple work load on him and giving him half of what it would have cost to get that work done by someone else. I would get what I want, and she would get what she needed (more work for less cost).

But being the Black Irishman that I was and continue to be, I “out of principle” stormed out of her office indignant that she refused to acknowledge my “true worth.”

I resigned. With absolutely zero leads on another publishing job. And now with a “hot-headed” reputation to boot.

Two days later, I wore my tattered high school graduation suit and made minimum wage as a receptionist at Estee Lauder Cosmetics. (Let’s see that smile Shawn!).

I’d stubbornly blown up a promising career because I didn’t understand the power of Story.

Served me right, too.

So editors move around a lot. An agent needs to have up to date information of who is doing what and where they are doing it. Or they end up calling on someone who isn’t there anymore.

So let’s pretend it’s 1996 and we’re the newbie literary agent Tina Bennett.

She works at the powerful agency Janklow & Nesbit. And she’s been developing a book proposal with Malcolm Gladwell based on his 4,000-word piece The Tipping Point.

Because she’s new, she’ll ask her colleague’s advice about who to target.

The first person she’ll probably talk to is another younger agent, someone who has more experience than her, but who is still a little wet behind the ears.

Let’s say she decided to talk to Eric Simonoff about what houses and what editors to approach about The Tipping Point. Simonoff, like Bennett today, is now a big agent at William Morris Endeavor but back then he was just another up and comer at Janklow & Nesbit hoping to one day make a living wage.

They probably went out to lunch or had coffee or a quick beer and came up with a list of possible publishers for a guy like Gladwell (New Yorker writer exploring a big nonfiction idea). Simonoff was an editorial assistant for industry legend Gerald Howard at Norton before he became an agent. So he was familiar with each of the house “brands.”

And in 1996, in no particular order, these were the major publishing houses that had reputations for publishing “high-end” big-think nonfiction.

Random House

Viking

Knopf

William Morrow

Henry Holt

Harcourt

Houghton Mifflin

Norton

Putnam

Little Brown

Doubleday

Simon & Schuster

Farrar Straus & Giroux

St. Martin’s Press

Grove Atlantic

HarperCollins

Crown

Scribner

With the long list in hand, Simonoff then told Bennett what they’d need to do next would be to pare the list down to say five houses for the first round of submission and then hone a pitch.

Bennett caught on…

Bennett: Then I use the list of editors on the agency info sheet, find the ones who do big idea nonfiction and then cold call?

Simonoff: No! Then we’ll go talk to Mort and Lynn…pitch them the project and the five houses you want to send it to…and ask them which editor you should call.

Bennett: Why bother them with this?

Simonoff: Who do you think Harry Evans or Roger Straus calls when they need to fill a big hole in their list? Mort and Lynn know what publishers and what editors want right now…not when the temp who takes notes at our meetings typed up that list.

If your pitch is good, not only will they tell you what houses are right for it, but who is desperate for a project like it. They may even make an early call to the publisher to tell them that you “may” be calling one of their editors about a big book project. Or they’ll mention it at off-hand to a scout at lunch.

So you won’t actually have to cold call. The editor may even call you!

Bennett: Why don’t we just go ask them now?

Simonoff: You need to have a damn good pitch for them to get involved. If you go in their offices without a plan and a great pitch, you’ll make an ass of yourself.

Bennett: Really?

Simonoff: What do you think I did on my first big submission?

So how did Bennett come up with a pitch for The Tipping Point as a book project?

That’s up next.

May 9, 2018

The Artist’s Journey, #13

We’re now well past halfway in The Artist’s Journey. The finished book (which Shawn and I have been putting together over the past month) has altered quite a bit from this serialization. Shawn found some chapters in a file that we’d been working on, preparing for a live seminar. Those went into the book. He tweaked and added other stuff and reordered a bunch of chapters. And as always, he took my eight “acts” and consolidated them into three. Why didn’t I think of that? If you’ve missed any of the prior posts, you can catch up here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11. And Part 12.

57. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO LET GO

I was visiting my friend Robert Bidner at his studio in Brooklyn. As Bob was showing me the paintings he was currently working on—about half a dozen on easels in varying stages of completion—I noticed another sheaf of canvases stacked against a wall in back.

“Those are my clinkers,” Bob said.

In the days when homes were heated by coal, he explained, every load inevitably contained one or two lumps that refused to burn.

Those were called clinkers.

I couldn’t stop my eye from returning to those abandoned paintings. I asked Bob if he ever hauled any back out and tried again to make them work.

I used to, he said.

Then he shook his head.

“You gotta know when to let go.”

58. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO BE ALONE

She trains herself to find emotional and spiritual sustenance in the work.

Her need for third-party validation attenuates. She may still ask you of her work, “What do you think?” But she evaluates your response within the framework of her own self-grounded assessment of her gifts and aspirations—and of how well or poorly she herself believes she has used the one in the service of the other.

59. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO WORK WITH OTHERS

She lets go of the need to plaster her name over everything.

It’s fun to jam, she decides. And even more fun when the finished product is better than any of the constituents could have produced on their own. She sees the beauty now in “Rodgers & Hammerstein” and “Jagger & Richards.”

Note please, as we delineate these skills, that their absence is the sign of the amateur.

An amateur can’t start, can’t keep going, can’t finish, can’t work alone, can’t work with others.

We ourselves were amateurs before our hero’s journey. That ordeal has chastened us. We have peered into the abyss and it has bitch-slapped us into reality. We might not, now, want to start, want to keep going, want to finish, want to work alone, want to collaborate—but we have confronted the alternative and it has scared us straight.

60. THE ARTIST LEARNS EMOTIONAL DISTANCE

I used to write novels that read like personal journals. To slog through them was excruciating, even for me.

The artist learns to detach himself from his expectations. He learns to separate his personal identity from his work.

No, he is not Holden Caulfield.

No, he is not Luke Skywalker.

Nor is she the book itself.

She is not Beloved.

She is not To Kill A Mockingbird.

The artist learns to interpose an emotional distance between herself and her work.

She acquires the capacity to zoom out, to see her material not through her own hope- or dread-freighted eyes, but through the lens of the impartial, impatient (and, yes, sympathetic) reader.

She stops looking at her stuff like an amateur and starts viewing it like a pro.

61. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO HANDLE REJECTION

Can you see the theme running through these chapters?

The theme is maturity.

The theme is professionalism.

The theme is mental toughness.

Every one of these skills (and the ones in chapters to follow) requires of the artist a profound shift in perspective and a quantum breakthrough in emotional self-possession. This work is hard. It hurts. We are beating our heads into a wall, hoping to teach ourselves to stop.

You may scoff at what I’m about to say, but we are becoming Zen masters.

We’re training ourselves to be Jedi knights.

I know, I know. “Every writer and artist I know,” you say, “is a lush, a sex addict, an emotional infant, simultaneously a tyrant and a coward, an egomaniac, a depressive and a flaming, incurable asshole.”

That may indeed be true.

But that’s not us.

That’s not you and me.

We are not going to be beaten by a pile of rejection slips (or even that excruciating close call that put us within inches of our material and artistic dream and then was snatched away at the fatal instant for reasons that were inane, arbitrary, or nonexistent altogether.)

No one said the artist’s journey was easy or without pain.

May 4, 2018

Mistakes are Opportunities

I made a mistake this week.

I was introduced to a few dozen new people.

I attempted to correct the mistake.

I was introduced to more new people.

This mistake was a springboard instead of an anchor.

When you make a mistake, you learn who is listening.

You learn who is invested.

You learn what they want.

The positive ones want to help you and are in for the long haul.

The negative ones were never going to stick around anyway. No matter what you say or do, they’ll find fault.

Specific example: On Wednesday I e-mailed the wrong link to Steve’s e-mail list. The heads up emails started arriving immediately. I sent a correction e-mail. E-mails from almost a completely set of individuals arrived.

They provided feedback, what they like/don’t like, their experiences with Steve’s work, the impact it has had on their own work, and so on. They provided value.

Whether you’re launching a book or a business, establishing a relationship with readers, customers, fans, etc., is important.

Of those relationships established with Steve and Black Irish Books, some of the greatest have come on the wings of mistakes.

I wouldn’t fake a mistake, but if one occurs, step up and address it, and then enjoy what follows. It’s extraordinary.

May 2, 2018

The Artist’s Journey, #12

I’ve spent part of the past couple of weeks recording the audio version of The Artist’s Journey, as well as copy-editing the eBook and the paperback. Sometime in July, we’ll have all of them ready to go. As Black Irish Books we can’t compete with Amazon or B&N on shipping prices but one thing we can do is offer discounts on bundles (paperback, eBook, and audiobook together at one low price) and on bulk purchases (55% discount on orders of 10+ copies of the same book). We will do the same for The Artist’s Journey. And now back to the ongoing serialization of The Artist’s Journey. If you missed any of the prior posts, you can get to them here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8. Part 9. Part 10. Part 11.

51. A QUICK NOTE RE RESISTANCE

The stages of the artist’s journey share one aspect in common.

They are all battles against Resistance.

Resistance meaning fear.

Resistance meaning distraction.

Resistance meaning temptation.

Resistance meaning the aggressive self-perpetuation of the ego.

Resistance meaning the terror the psyche experiences at the prospect of encountering the Self, i.e. the soul, the unconscious, the superconscious.

On the artist’s journey we develop skills. Skills we did not have before.

We teach ourselves these skills.

We apprentice ourselves to others wiser than we are.

We are fortifying ourselves, training ourselves against fear, boredom, laziness, arrogance, self-inflation, complacency.

Our aim is to make ourselves masters, not just of our craft, but also of ourselves.

When we underwent our original hero’s journey we were neophytes. We had no idea what we were doing.

Now we are different.

We return to the fire determined to do it better this time.

52. AN INDEX OF BASIC SKILLS

What follows is my own idiosyncratic inventory of the fundamental (mandatory) skills that the artist acquires on his or her artist’s journey.

53. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO START

This sounds so obvious, so self-evident. And yet …

Not one aspirant in a hundred, in my experience, is capable of pulling the trigger, jumping out of the airplane, diving head-first into the icy pool.

54. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO KEEP GOING

The phrase “Act Two problems” has become a cliche. Why? Because the winnowing scythe of Resistance cuts down so many aspiring artists right here, in mid-odyssey. Here’s David Mamet from Three Uses of the Knife.

In his analysis of world myth, Joseph Campbell calls this period in the belly of the beast—-the time which is not the beginning and not the end, the time in which the artist and the protagonist doubt themselves and wish the journey had never begun.

… How many times have we heard (and said): Yes, I know that I was cautioned, that the way would become difficult and I would want to quit, that such was inevitable, and that at exactly this point the battle would be lost or won. Yes, I know all that, but those who cautioned me could not have foreseen the magnitude of the specific difficulties I am experiencing at this point—difficulties which must, sadly, but I have no choice, force me to resign the struggle (and have a drink, a cigarette, an affair, a rest), in short, to declare failure.

55. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO FINISH

Notice please that these first three skills exist in relation to Resistance. They are about overcoming Resistance.

Before our hero’s journey, we had never even started a project. (We had fabricated some excuse to put it off.) Or if we had started, we bailed in the middle or choked at the end.

But now we are different. We have been toughened by our real-life hero’s journey. We will not yield this time. We will find our way over, under, around, or through the obstacles, no matter what.

Note too that these first three skills are aspects of professionalism. They are the same skills that are mastered by the professional athlete, the professional businessperson, or anyone (including Moms and Dads and their own kids in school) who is committed to an aspiration or a calling.

These skills and others we’ll delineate in subsequent chapters constitute the infrastructure of the artist’s power. They are the tracks along which his locomotive rolls and the foundation upon which the edifices of his city rise.

56. THE ARTIST LEARNS HOW TO HANG ON

I worked on a movie that took seventeen years to get made. When the Writers Guild opened the arbitration process for screen credit, more than thirty screenwriters filed.

One writer, the originator of the project, had been on the picture from the beginning. Even when he was fired and other writers or other teams of writers were brought in, he stayed attached as a producer. (He made half a dozen other movies in the interim, by the way.)

He was brought back four different times as a writer. He was there at the finish. He got the credit. He saw the movie made.

Was he crazy?

Maybe.

But this writer over his career has been the originator of three big-time artistic and box office hits (an incredible feat), including one film that’s a legitimate Top Fifty classic.

The artist learns how to hang on.