Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 52

February 16, 2018

Storygridding 4,000 words of Big Idea Nonfiction

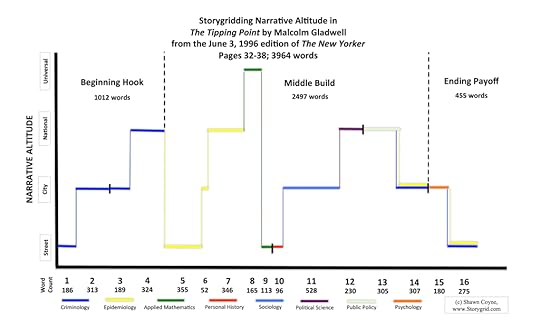

For fun, over at www.storygrid.com a while back, I storygridded Malcolm Gladwell’s seminal article from the June 3, 1996 edition of The New Yorker. I tracked the narrative altitude in the work that I described in my post from February 2, 2018.

The vertical axis moves from the “street” level perspective at the lowest elevation through the “city” vantage point up to the “national” level and then all the way to the highest “universal” level. Four specific lenses that he uses to progressively build dramatic tension.

The horizontal axis takes us through the piece word by word, beat by beat, and subject by subject.

To see how Gladwell tackled so many academic disciplines (including personal history) as he moved his narrative camera shows just how much craft goes into a single article.

I recommend reading the piece with this graph in front of you to observe the professional writer performing the literary equivalent of Red Gerard’s final run at the Olympics.

February 14, 2018

"This Might Not Work … "

Stealing a phrase (above) from Seth Godin, I’m going to try something a little different over the next few weeks and maybe more.

I’m gonna serialize a book I’ve been working on.

Consider the course and contour of this artist’s journey …

The book is about writing.

I don’t have a title yet but the premise is that there’s such a thing as “the artist’s journey.”

The artist’s journey is different from “the hero’s journey.”

The artist’s journey is the process we embark upon once we’ve found our calling, once we know we’re writers but we don’t know yet exactly what we’ll write or how we’ll write it.

These posts will be a bit longer than normal, just because that’s how chapters in a book fall. I don’t wanna post truncated versions that are so short they don’t make sense, just because that’s where chapters happen to break.

Please let me know if you hate this.

I’ll stop if it’s not worth our readers’ time or if our friends find the material boring.

That said, let’s kick it off.

Starting with the epigraph, here’s the beginning of this so-far-untitled book:

I found that what I had desired all my life was not to live—if what others are doing is called living—but to express myself. I realized that I had never had the least interest in living, but only in this which I am doing now, something which is parallel to life, of it at the same time, and beyond it. What is true interests me scarcely at all, nor even what is real; only that interests me which I imagine to be, that which I had stifled every day in order to live.

Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn

B O O K O N E

T H E H E R O’ S J O U R N E Y

A N D T H E A R T I S T’ S J O U R N E Y

THE SHAPE OF THE ARTIST’S JOURNEY

Consider the course and contour of this artist’s journey:

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

Born to Run

Darkness on the Edge of Town

The River

Nebraska

Born in the U.S.A.

Tunnel of Love

Human Touch

Lucky Town

The Ghost of Tom Joad

Working on a Dream

Wrecking Ball

High Hopes

Or this artist’s:

Goodbye, Columbus

Portnoy’s Complaint

The Great American Novel

My Life as a Man

The Professor of Desire

Zuckerman Unbound

The Anatomy Lesson

The Counterlife

Sabbath’s Theater

American Pastoral

The Human Stain

The Plot Against America

Indignation

Nemesis

Or this artist’s:

Clouds

Ladies of the Canyon

Blue

For the Roses

Court and Spark

The Hissing of Summer Lawns

Hejira

Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter

Wild Things Run Fast

Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm

Night Ride Home

Turbulent Indigo

Clearly there is a unity (of theme, of voice, of intention) to each of these writers’ bodies of work.

There’s a progression too, isn’t there? The works, considered in sequence, feel like a journey that is moving in a specific direction.

Bob Dylan

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

The Times They Are a-Changin’

Highway 61 Revisited

Blonde on Blonde

Bringing It All Back Home

Blood on the Tracks

Desire

John Wesley Harding

Street-legal

Nashville Skyline

Slow Train Coming

Hard Rain

Time Out of Mind

Tempest

Shadows in the Night

A strong case could be made that the bodies of work cited above (and those of every other artist on the planet) comprise a “hero’s journey,” in the classic Joseph Campbell/C.G. Jung sense.

I have a different interpretation.

I think they represent another journey.

I think they represent “the artist’s journey.”

“This Might Not Work … “

Stealing a phrase (above) from Seth Godin, I’m going to try something a little different over the next few weeks and maybe more.

I’m gonna serialize a book I’ve been working on.

Consider the course and contour of this artist’s journey …

The book is about writing.

I don’t have a title yet but the premise is that there’s such a thing as “the artist’s journey.”

The artist’s journey is different from “the hero’s journey.”

The artist’s journey is the process we embark upon once we’ve found our calling, once we know we’re writers but we don’t know yet exactly what we’ll write or how we’ll write it.

These posts will be a bit longer than normal, just because that’s how chapters in a book fall. I don’t wanna post truncated versions that are so short they don’t make sense, just because that’s where chapters happen to break.

Please let me know if you hate this.

I’ll stop if it’s not worth our readers’ time or if our friends find the material boring.

That said, let’s kick it off.

Starting with the epigraph, here’s the beginning of this so-far-untitled book:

I found that what I had desired all my life was not to live—if what others are doing is called living—but to express myself. I realized that I had never had the least interest in living, but only in this which I am doing now, something which is parallel to life, of it at the same time, and beyond it. What is true interests me scarcely at all, nor even what is real; only that interests me which I imagine to be, that which I had stifled every day in order to live.

Henry Miller, Tropic of Capricorn

B O O K O N E

T H E H E R O’ S J O U R N E Y

A N D T H E A R T I S T’ S J O U R N E Y

THE SHAPE OF THE ARTIST’S JOURNEY

Consider the course and contour of this artist’s journey:

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

Born to Run

Darkness on the Edge of Town

The River

Nebraska

Born in the U.S.A.

Tunnel of Love

Human Touch

Lucky Town

The Ghost of Tom Joad

Working on a Dream

Wrecking Ball

High Hopes

Or this artist’s:

Goodbye, Columbus

Portnoy’s Complaint

The Great American Novel

My Life as a Man

The Professor of Desire

Zuckerman Unbound

The Anatomy Lesson

The Counterlife

Sabbath’s Theater

American Pastoral

The Human Stain

The Plot Against America

Indignation

Nemesis

Or this artist’s:

Clouds

Ladies of the Canyon

Blue

For the Roses

Court and Spark

The Hissing of Summer Lawns

Hejira

Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter

Wild Things Run Fast

Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm

Night Ride Home

Turbulent Indigo

Clearly there is a unity (of theme, of voice, of intention) to each of these writers’ bodies of work.

There’s a progression too, isn’t there? The works, considered in sequence, feel like a journey that is moving in a specific direction.

Bob Dylan

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

The Times They Are a-Changin’

Highway 61 Revisited

Blonde on Blonde

Bringing It All Back Home

Blood on the Tracks

Desire

John Wesley Harding

Street-legal

Nashville Skyline

Slow Train Coming

Hard Rain

Time Out of Mind

Tempest

Shadows in the Night

A strong case could be made that the bodies of work cited above (and those of every other artist on the planet) comprise a “hero’s journey,” in the classic Joseph Campbell/C.G. Jung sense.

I have a different interpretation.

I think they represent another journey.

I think they represent “the artist’s journey.”

February 9, 2018

Don't Major in the Minor

(Past is present. With a December 6, 2013 date, this post is a little over four years old. The drones haven’t replaced humans yet, but Amazon is still pushing distribution, with its announcement that Amazon is going to enter UPS’ and FedEx’s space. O’Reilly has continued to change things up since this writing, but is still leading the way. More cultivated subscription models, too.)

“Don’t major in the minor.”

Mellody Hobson said it, but I’ve thought it these last few days, since watching Jeff Bezos on 60 Minutes this past Sunday.

In case you haven’t heard, Bezos unveiled a prototype for package-delivering drones at the end of the interview. Without missing a beat, the character-bashing, Jeff-Bezos hating, Amazon-vilifying tribes descended, with articles and comments from one site to the next.

They majored in the minor.

I’m not saying that the drones weren’t newsworthy. They were—and I saw mentions pop up in everything from Outside Magazine’s site to Waterstones’ blog. And I’m not saying that Amazon isn’t above criticism, but . . .

There was much more to that interview than the last few minutes of drones. And if you are going to go down the drone rabbit hole, there’s a much bigger discussion that needs to take place, outside whether Amazon will or won’t ever be able to use them.

Instead of responding to the bigger ideas, they went for the jugular and the jocular, playing guessing games about why 60 Minutes ran the interview, why the secretive Bezos shared the drones.

Why does knowing why Bezos shared the drones matter? Why is anyone surprised that 60 Minutes would feature Amazon in a story about Cyber Monday? What is the point of all the guessing games?

The drones may have made headlines, but the rest of the interview held the story I clung to these past few days.

1) Complaining is not a strategy

When Charlie Rose asked Bezos about worries of small book publishers and traditional retailers, and whether Amazon is ruthless in its pursuit of market share, Bezos replied:

“The internet is disrupting every media industry, Charlie. You know, people can complain about that, but complaining is not a strategy. Amazon is not happening to bookselling. The future is happening to bookselling.” (about the 9:15 mark of the interview)

He’s right. And the future isn’t just happening to booksellers. Look at how the rise of e-mail played into the decline of the U.S. Postal Service’s revenues. After years of struggling, a plan was sent to Congress for approval, to end Saturday delivery. Congress nixed the plan. A few months later, Amazon stepped in with a different plan—to add Sunday service. Via this partnership, the USPS will deliver Amazon’s packages on the one day of the week that no one else delivers them, thus increasing delivery options for Amazon customers and bringing in revenue to the USPS. A win-win.

The examples of industries sideswiped by the future is long, as is the list of industries that have risen, offering much needed innovation and efficiency.

But . . .

It’s easier to bash Bezos and Amazon than it is to look in the mirror and ask, Why didn’t my publishing house lead the charge to sell books online? Why did we focus on the chains as the future when we saw the indy stores struggling to stay afloat? Why didn’t we recognize the potential for the future?

It’s easier to hate Bezos and Amazon than it is to ask, Why didn’t my bookstore stock backlist, long-tail titles, and books from indy publishers in addition to all those big publisher frontlist titles? Why didn’t my bookstore create a model that could be tapped by indy publishers and authors, instead of requiring top co-op dollars that only the big guys could pay for prime placement?

It’s easier to vilify Bezos and Amazon than it is to ask, Why didn’t I keep spending dollars with indy stores instead of spending them at the big chains, which then caused the indys I love to die?

It’s easier to major in the minor.

Here’s the thing: No one in the publishing equation is innocent.

Bezos didn’t kill publishing. The Future didn’t kill publishing. Publishing’s inability to adapt killed publishing…. Same thing with the USPS, the music industry, and businesses in so many other sectors.

2) It’s all about fulfillment

Neither the chains or the publishers or the indy’s of yesterday thought about fulfillment the way Amazon has, which was one of the most fascinating portions of the interview. And when I talk publishers, I’m talking in terms of movies and newspapers and albums, too.

It’s popular to say content is king. I’d give joint reign to content and fulfillment instead.

Content doesn’t matter if you can’t get it out in today’s I-want-it-and-I-want-it-now on-demand climate. Amazon figured out how to do it. I’ve been in a few warehouses and I’ve never seen anything like what was shown during the interview.

The fulfillment part is another reason why the drones didn’t faze me as much. Do I question them? Yes. I immediately saw the kids in my neighborhood tagging them with Nerf bullets. But that was it. Fulfillment is what Amazon does well. It’s where I expect them to continue as innovators. So the drones? Surprised by the how, but not the why.

3) Greenlighting is changing.

For a long time the traditional publishers were the only game in town – whether the big sixish or the mid-sized or indy. Want to get something published or recorded? You went to them or did it on your own or gave up.

Amazon announced its own publishing program a while back, so it shouldn’t have been such a shock when Netflix left studios in its dust, after adding award-winning original programming to its menu. Where they were both sellers, they’re now producers, too, offering alternatives to traditional publishing outlets.

In Amazon’s case . . .

“We’re changing the greenlighting process,” said Bezos of Alpha House, an original series from Gary Trudeau, which Amazon is producing. “Instead of a few studio executives deciding what gets greenlighted . . . we’re using what some people would call crowdsourcing to help figure that out.” Yep. He went to the customers.

So if I was a publisher and/or a bookseller, how would I compete with Amazon?

I’d bring back the indy.

While Amazon offers so much, it doesn’t offer the touch of a specialized store, with employees that breathe books. There’s no one to chat with, to ask for a specific holiday book suggestion for a father who likes the military, medicine and gardening, or a sister who likes to read arts and crafts guides, and legal briefs.

The indy store reboot wouldn’t be the old school bricks and mortar store. It would exist online, cultivating very specific genres, building equally specific communities. And, it would most likely be a collaboration project—perhaps booksellers or authors or even publishers could develop a shared place online to sell those titles and grow a community. Instead of everyone trying to create their own wheel and grow a community around that wheel, thus competing for the community, they’d build one wheel together. Instead of everyone operating all for one, they’d operate one for all.

The closest example? O’Reilly Media is the only one I can think of . . . O’Reilly has been cultivating a very specific community for years, selling very specific genres of books and growing a specific audience, with an unwavering—yes, specific—focus.

When O’Reilly launched Safari Books Online, in July 2000, it offered its audience a new way to tap into books, but with the indy approach you might get in one of the old mom and pop stores. That was over ten years ago, when Amazon was just losing its baby teeth.

While there are some publishers, such as Praeger, which launched PSI a few years back, that have found ways to fulfill books and other content online, they’ve taken the institutional approach, which most book buyers can’t afford. The individual books aren’t for sale and the pricing is based on universities and other organizations making purchases. There isn’t a genre-specific indy that I can think of, other than O’Reilly, that nailed the genre in terms of options and community building – AND – in terms of price point, offering readers a model they can afford.

And, O’Reilly is collaborating with other publishers, too. It built Safari, but you’ll find books from publishers such as Microsoft and Wiley featured within Safari, too.

O’Reilly is indy in style, majoring in everything BUT the minor.

It’s an amazing model and one that Amazon doesn’t have going for it.

So…

Look to the indy. Look to collaboration/partnerships. Look to other options. Look to the future.

And, stop majoring in the minor.

Amazon and Bezos aren’t above criticism, but they aren’t the problem either. Complaining about them will get the publishing industry nowhere.

Don’t Major in the Minor

(Past is present. With a December 6, 2013 date, this post is a little over four years old. The drones haven’t replaced humans yet, but Amazon is still pushing distribution, with its announcement that Amazon is going to enter UPS’ and FedEx’s space. O’Reilly has continued to change things up since this writing, but is still leading the way. More cultivated subscription models, too.)

“Don’t major in the minor.”

Mellody Hobson said it, but I’ve thought it these last few days, since watching Jeff Bezos on 60 Minutes this past Sunday.

In case you haven’t heard, Bezos unveiled a prototype for package-delivering drones at the end of the interview. Without missing a beat, the character-bashing, Jeff-Bezos hating, Amazon-vilifying tribes descended, with articles and comments from one site to the next.

They majored in the minor.

I’m not saying that the drones weren’t newsworthy. They were—and I saw mentions pop up in everything from Outside Magazine’s site to Waterstones’ blog. And I’m not saying that Amazon isn’t above criticism, but . . .

There was much more to that interview than the last few minutes of drones. And if you are going to go down the drone rabbit hole, there’s a much bigger discussion that needs to take place, outside whether Amazon will or won’t ever be able to use them.

Instead of responding to the bigger ideas, they went for the jugular and the jocular, playing guessing games about why 60 Minutes ran the interview, why the secretive Bezos shared the drones.

Why does knowing why Bezos shared the drones matter? Why is anyone surprised that 60 Minutes would feature Amazon in a story about Cyber Monday? What is the point of all the guessing games?

The drones may have made headlines, but the rest of the interview held the story I clung to these past few days.

1) Complaining is not a strategy

When Charlie Rose asked Bezos about worries of small book publishers and traditional retailers, and whether Amazon is ruthless in its pursuit of market share, Bezos replied:

“The internet is disrupting every media industry, Charlie. You know, people can complain about that, but complaining is not a strategy. Amazon is not happening to bookselling. The future is happening to bookselling.” (about the 9:15 mark of the interview)

He’s right. And the future isn’t just happening to booksellers. Look at how the rise of e-mail played into the decline of the U.S. Postal Service’s revenues. After years of struggling, a plan was sent to Congress for approval, to end Saturday delivery. Congress nixed the plan. A few months later, Amazon stepped in with a different plan—to add Sunday service. Via this partnership, the USPS will deliver Amazon’s packages on the one day of the week that no one else delivers them, thus increasing delivery options for Amazon customers and bringing in revenue to the USPS. A win-win.

The examples of industries sideswiped by the future is long, as is the list of industries that have risen, offering much needed innovation and efficiency.

But . . .

It’s easier to bash Bezos and Amazon than it is to look in the mirror and ask, Why didn’t my publishing house lead the charge to sell books online? Why did we focus on the chains as the future when we saw the indy stores struggling to stay afloat? Why didn’t we recognize the potential for the future?

It’s easier to hate Bezos and Amazon than it is to ask, Why didn’t my bookstore stock backlist, long-tail titles, and books from indy publishers in addition to all those big publisher frontlist titles? Why didn’t my bookstore create a model that could be tapped by indy publishers and authors, instead of requiring top co-op dollars that only the big guys could pay for prime placement?

It’s easier to vilify Bezos and Amazon than it is to ask, Why didn’t I keep spending dollars with indy stores instead of spending them at the big chains, which then caused the indys I love to die?

It’s easier to major in the minor.

Here’s the thing: No one in the publishing equation is innocent.

Bezos didn’t kill publishing. The Future didn’t kill publishing. Publishing’s inability to adapt killed publishing…. Same thing with the USPS, the music industry, and businesses in so many other sectors.

2) It’s all about fulfillment

Neither the chains or the publishers or the indy’s of yesterday thought about fulfillment the way Amazon has, which was one of the most fascinating portions of the interview. And when I talk publishers, I’m talking in terms of movies and newspapers and albums, too.

It’s popular to say content is king. I’d give joint reign to content and fulfillment instead.

Content doesn’t matter if you can’t get it out in today’s I-want-it-and-I-want-it-now on-demand climate. Amazon figured out how to do it. I’ve been in a few warehouses and I’ve never seen anything like what was shown during the interview.

The fulfillment part is another reason why the drones didn’t faze me as much. Do I question them? Yes. I immediately saw the kids in my neighborhood tagging them with Nerf bullets. But that was it. Fulfillment is what Amazon does well. It’s where I expect them to continue as innovators. So the drones? Surprised by the how, but not the why.

3) Greenlighting is changing.

For a long time the traditional publishers were the only game in town – whether the big sixish or the mid-sized or indy. Want to get something published or recorded? You went to them or did it on your own or gave up.

Amazon announced its own publishing program a while back, so it shouldn’t have been such a shock when Netflix left studios in its dust, after adding award-winning original programming to its menu. Where they were both sellers, they’re now producers, too, offering alternatives to traditional publishing outlets.

In Amazon’s case . . .

“We’re changing the greenlighting process,” said Bezos of Alpha House, an original series from Gary Trudeau, which Amazon is producing. “Instead of a few studio executives deciding what gets greenlighted . . . we’re using what some people would call crowdsourcing to help figure that out.” Yep. He went to the customers.

So if I was a publisher and/or a bookseller, how would I compete with Amazon?

I’d bring back the indy.

While Amazon offers so much, it doesn’t offer the touch of a specialized store, with employees that breathe books. There’s no one to chat with, to ask for a specific holiday book suggestion for a father who likes the military, medicine and gardening, or a sister who likes to read arts and crafts guides, and legal briefs.

The indy store reboot wouldn’t be the old school bricks and mortar store. It would exist online, cultivating very specific genres, building equally specific communities. And, it would most likely be a collaboration project—perhaps booksellers or authors or even publishers could develop a shared place online to sell those titles and grow a community. Instead of everyone trying to create their own wheel and grow a community around that wheel, thus competing for the community, they’d build one wheel together. Instead of everyone operating all for one, they’d operate one for all.

The closest example? O’Reilly Media is the only one I can think of . . . O’Reilly has been cultivating a very specific community for years, selling very specific genres of books and growing a specific audience, with an unwavering—yes, specific—focus.

When O’Reilly launched Safari Books Online, in July 2000, it offered its audience a new way to tap into books, but with the indy approach you might get in one of the old mom and pop stores. That was over ten years ago, when Amazon was just losing its baby teeth.

While there are some publishers, such as Praeger, which launched PSI a few years back, that have found ways to fulfill books and other content online, they’ve taken the institutional approach, which most book buyers can’t afford. The individual books aren’t for sale and the pricing is based on universities and other organizations making purchases. There isn’t a genre-specific indy that I can think of, other than O’Reilly, that nailed the genre in terms of options and community building – AND – in terms of price point, offering readers a model they can afford.

And, O’Reilly is collaborating with other publishers, too. It built Safari, but you’ll find books from publishers such as Microsoft and Wiley featured within Safari, too.

O’Reilly is indy in style, majoring in everything BUT the minor.

It’s an amazing model and one that Amazon doesn’t have going for it.

So…

Look to the indy. Look to collaboration/partnerships. Look to other options. Look to the future.

And, stop majoring in the minor.

Amazon and Bezos aren’t above criticism, but they aren’t the problem either. Complaining about them will get the publishing industry nowhere.

February 7, 2018

How Steven Spielberg Handles his Villains

Steven Spielberg loves to tease us with his villains.

It’s twice as scary when you DON’T see the shark

He shows them only indirectly.

In the audience we see the effects of the Bad Guys’ actions, but we rarely see the malefactors themselves.

This is tremendously powerful because it makes us imagine what the forces of evil look like, and that’s always scarier than actually seeing them in blinding daylight.

Remember the scene in Jaws with the three yellow barrels? Our heroes in their boat (Richard Dreyfuss, Roy Scheider, and Robert Shaw) harpoon the shark with cables linked to three huge yellow air-tank-like barrels. The barrels float on the ocean surface, enabling our hunters (and us) to see the shark’s movements from the boat even when the finned menace is submerged.

The great cinematic moment is when the three barrels go churning across the surface at high speed toward the boat, then dive under and come up on the other side.

We never see the shark.

But wow, how we imagine him.

That dude, we can’t help but say to ourselves, must be HUGE!

Likewise Spielberg doesn’t really show us the Meanies pursuing E.T. We see only their flashlight beams searching for the little guy, or their keys jangling on their work belts as they close in on him.

The giant spaceship wasn’t really the villain in Close Encounters but it felt like at least an ominous, unknown force at the start. Again, Spielberg withheld for most of the movie all direct sight of this entity.

We saw headlights and amber lights behind Richard Dreyfuss’s pickup truck. We saw screws mysteriously jiggling out of their sockets on Melinda Dillon’s floor and crazy lights flashing under her door jamb. The whole house shook. Electric toy cars began scooting across the floor. Melinda’s little son became mesmerized by the lights appearing outside.

Melinda Dillon as the mom in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”

But we never saw the space ship.

Ridley Scott worked the same magic in the original Alien. We saw the nasty little bugger (the Alien, not Mr. Scott) burst out of John Hurt’s chest and flee into the darkness of the huge space vessel. But after that, the scares all came from shadows and images on search screens, mixed with the odd Holy Crap pop-up of the monster, followed by an instantaneous cut-away.

You and I could profit by stealing this trick from these great scare-meisters.

Keep the villain present and aggressive in the effects he produces, but show him overtly as little as possible.

February 2, 2018

Narrative Altitude

From www.storygrid.com, here is the next piece in my exploration of Malcolm Gladwell’s seminal work, The Tipping Point.

For over a decade, Malcolm Gladwell understood the opportunity and potential of the tipping point idea. And by the time he arrived at The New Yorker in 1996, chances are he’d explored many of its intellectual trails—GRODZINS ’57; SCHELLING ’69, ’71, ’78; GRANOVETTER ’78, ’83; MORLEY ’84; CRANE ’89.

If only in his own head, while waiting in line for take-out coffee at The Red Flame Diner on 44th Street, he’d cleared substantial tipping point terrain of his own. But his goal was not just to add an offshoot to one of his predecessors’ efforts, but instead to pull them all together and carve a freeway into what he felt was the unexplored heart of the idea.

That tipping points are not just useful as predictors of social polarization, but consciously engineered, they can serve as positive behavioral modification systems for entire communities.

That’s great, but how is he going to make a story out of that mess of theory?

How is he going to make the tipping point relevant to readers of The New Yorker in June 1996?

That is, how is he going to do his job?

Don’t forget that Gladwell’s just a newbie staff writer at perhaps the most prestigious literary magazine in the world. He’s got a one-year contract. And he’s only written three pieces, which were solid hits, but they certainly aren’t anywhere near the heavy lifting Big Idea throw-down inherent in this piece.

What Gladwell has been looking for all of these years to make his tipping point notion engaging—at a story level—is a high profile “connector” idea. A bit of something relevant to contemporary society. Writing about white flight ain’t that.

What phenomenon he discovers in 1996 is beautifully organic to the original piece that caught his attention back in 1984—Jefferson Morley’s “Double Reverse Discrimination” in The New Republic. It’s in fact shockingly poetic on a story level too.

The connector idea that Gladwell uses to explore his theory about the tipping point—that it can be engineered to effect positive social change—is the one credited with dropping crime in New York City off a cliff. It is George Kelling and James Q. Wilson’s extension of Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s 1969 “broken window experiments” in their article Broken Windows from the March 1982 edition of yet another wonky magazine, The Atlantic.

So how does Gladwell make this crime falls because of a theory into a story?

Well, he starts his June 3, 1996 New Yorker piece, The Tipping Point, like any great novelist would. He introduces a killer beginning hook.

This in a nutshell:

New York City, which is most peoples’ minds since the late 1960s is the land of mayhem, muggings and indiscriminate murder, is not what you think it is. It is now about as dangerous as Boise, Idaho. By June 3, 1996, it ranks 136th on the FBI’s violent crime rate among major American cities.

What happened?

Obviously, this is the underlying question that will drive the narrative into the middle build of the piece…and ultimately pay off with a very satisfying answer. How did a place often associated with the dark desire of the fictional character Travis Bickle in Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver for a real rain to come “and wash all this scum off the streets” actually turn safe?

It’s a very good hook.

But here’s the thing. If Gladwell just flies his narrative in altitude above the city…that is he doesn’t takes us “on the ground” to a real place within the city and what it’s like there…then we won’t really care. We’ll do what we’ve done with innumerable New Yorker pieces before…we’ll skim it and forget it.

What he needs to do to keep us reading about this strange fall in crime phenomenon is to make it human. He needs to give us low altitude reporting with commentary from eyewitnesses to let us “experience” it. We need to hear from a cop in a specific neighborhood tell us what it was like before the change and what it’s like after the change.

After we get a sense of how one particular neighborhood in the big city has changed, then Gladwell can fly a little higher with a larger point of view. He can interview the New York City Police Commissioner, William J. Bratton, who will tell the reader why he thinks the change has occurred in the first place.

And then back to the low altitude, back to the Seven-Five Precinct to hear how Bratton’s big talk actually is put into practice on the street.

Gladwell finishes the beginning hook of his piece with a transition that will allow him to fly above the city entirely. After listing all of the little things that Bratton talks about being instrumental in the plummeting of New York City Crime, Gladwell suggests that it’s pretty hard to believe that stopping guys from hanging out on street corners sipping beer is responsible for a crazy decline in crime. He does what good storytellers do to keep a reader engaged. He states what the reader is probably thinking to themselves.

Maybe we need to think differently about this whole thing? Maybe we should consider what the academic world has been saying about social problems? Which transitions the story into the progressive complications for the Middle Build for his piece—that crime can be better understood in epidemiological terms.

The first sequence in Gladwell’s Middle Build is introducing the reader to the world of epidemics. Not the pejorative use of the word like “there’s an epidemic of Axe Deodorant wearing teenage boys on the loose,” but the actual math behind the literal definition of an epidemic.

This is yet another shift in narrative altitude for the piece…one that Gladwell mastered back in his science beat days at The Washington Post. This altitude is “the easy to understand hypothetical scenario that explains a complex idea in a very simple way” vantage point. In this case, Gladwell walks us through an outbreak of Canadian flu brought to Manhattan at Christmas time. You’ll notice that he didn’t choose to base his hypothetical germ fest in London or Zurich. No, he’s keeping the reader still thinking about New York City even though it’s a made up scenario.

He finishes up the ground level hypothetical flu contagion with the epidemiologist’s definition of the “tipping point.” It is a specific number—“the point at which an ordinary and stable phenomenon—a low-level flu outbreak—can turn into a public-health crisis.”

Even though he’s been noodling the idea for years, this is the first time Gladwell writes publicly about the “tipping point.”

Wasn’t it a brilliant decision to define it so specifically?

What I mean by that is Gladwell could have spoken of tipping points as sort of amorphous moments in time when something goes from unpopular to popular—like he’ll do in his book in a few years when he describes sales of Hush Puppies shoes.

But instead, he chose to define a tipping point with a very definitive number…in the case of his hypothetical outbreak of flu, it’s the number 50. Is there anything more convincing and solid than a number? When someone answers a question with a number, we can’t help but think of it as a fact. We think differently about someone who clearly says “I’m 52 years old” versus someone who says “How old do you think I am?” One is telling the truth and the other one is just playing games. Right?

So associating “tipping point” with a number is a way for Gladwell to subconsciously say to the reader that tipping points aren’t “theories” or some intellectual bullshit game playing. They’re facts. So in other words, pay attention!

And then Gladwell progressively complicates his story further. He escalates the stakes of tipping points from a hypothetical bunch of New Yorkers getting an inconvenient flu at Christmas time, to the very real deaths of forty thousand people in the United States contracting and dying of AIDS every year.

The narrative altitude has risen even higher. We’re not just having some intellectual fun looking at what may or may not have caused crime to drop in New York City or how a flu gets spread, we’re grappling with thousands of lives. We’re above the city now, looking at the state of global public health.

There is no way to go higher in narrative altitude than that. Is there? We’re dealing with the global material world—life and death stuff. That’s got to be the ceiling, right?

Well, like a narrative nonfiction answer to Emeril Lagesse, in the very next beat in his piece, Gladwell kicks it up yet another notch.

He takes the narrative altitude above the city and the state and enters the heavens to explain that the way we think the world works can often be wildly incorrect. The world is not always linear. It’s often a geometric progression where big efforts have little effects and little efforts have big effects (the controlling idea of his first piece for The New Yorker, “Blowup.”).

Sometimes big efforts have small effects—like moving ten tons of dirt on a perfectly level field. And sometimes small efforts—like shoveling ten pounds of dirt beneath a precipice—can have huge effects, an avalanche. Simple to understand with the right analogy, but try and remember that when you’ve worked for a week and a half on a post that no one reads…

Just as quickly as his transitions from the upper reaches of public health to the heavens, Gladwell brings his narrative altitude back to the ground. He explains the concept of non-linearity by examining the risks to an unborn child of a pregnant women having a single glass of wine, which amount to negligible.

And then he uses his own life experience as interstitial tissue to lighten the narrative and bring the idea of hitting a threshold home. He remembers life as a child pounding on a bottle of ketchup and quotes his British father at the dinner table:

Tomato ketchup in a bottle—

None will come and then the lot’ll.

From a fictional Xmas Flu to AIDS to Geometric Progression to a Pregnant woman having a glass of wine to a kid pounding ketchup… The narrative altitude, like moving up and down small dips and then medium bumps and then large free falls on a roller coaster—keeps the readers minds engaged. Not knowing what will happen next even though they know where their final destination will be is what keeps a reader reading.

After the ketchup, Gladwell transitions into the Ending Payoff of his piece with a technique I adore. He anticipates a reader’s confusion and addresses it directly with a rhetorical question—“What does this have to do with the murder rate in Brooklyn?”

Now that we’re used to the different levels of narrative altitude, Gladwell will put all of the pieces together for us in a way that will explain exactly why the crime rate in New York City declined so rapidly from 1994 to 1996.

With the fluent storytelling in evidence from his Beginning Hook through his Middle Build of this piece, the reader now trusts that Gladwell knows this stuff cold. They’ll take him now at his word.

So now Gladwell can act as expert and maintain a comfortable omniscient altitude. That is, he doesn’t have to do as many stunt pilot maneuvers to keep the reader glued to the page. He’s reached the ending payoff so now it’s time to lay his argument out in as clear and engaging way as possible, without going off on hypotheticals or tangents. He’s reached the punch line. He just has to deliver it clearly and quickly to close.

So he walks the reader through the academic work that supports his conclusions. We get:

A bit about Thomas Schelling’s work on white flight,

George Galster at the Urban Institute in Washington backing up Schelling,

David Rowe at the University of Arizona on teen sexual behavior tipping points

Jonathan Crane at the University of Illinois,

Mark L. Rosenberg at the Centers for Disease Control

Range Hutson and his paper “The Epidemic of Gang-Related Homocides in Los Angeles Country from 1979 through 1994.”

And at last we reach the payoff…which is Stanford University professor Philip Zimbardo’s “broken window” experiments.

Zimbardo parked tow cars in two neighborhoods—one in Palo Alto and one in a comparable neighborhood in the Bronx in New York. For the car in New York, he took off the license plates and popped the hood of the trunk. A day later, it was stripped to the bone.

The Palo Alto car was untouched until Zimbardo smashed one of the windows. In a couple of hours that car was destroyed too.

Gladwell draws this conclusion:

“Zimbardo’s point was that disorder invites even more disorder—that a small deviation from the norm can set into motion a cascade of vandalism and criminality. The broken window was the tipping point.”

He concludes the piece with the report that William Bratton reverse engineered Zimbardo’s work—he cracked down on graffiti and turnstile jumpers when he was head of the New York City Transit police and when he became Police Commissioner extended those “quality of life” crime crack downs.

All of those little efforts made New York City tip from a dangerous concrete jungle into a town as threatening as Boise, Idaho.

January 31, 2018

Give Your Villain a Great Villain Speech

I’m a huge fan of Villain Speeches. There’s nothing better in a book or a movie than the moment when the stage is cleared and Satan gets to say his piece.

Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko in Oliver Stone’s “Wall Street”

GORDON GEKKO

I am not a destroyer of companies. I am a liberator of them! The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind. And greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the U.S.A.

A great Villain Speech should ring true. It should masterfully articulate a valid point of view. Here’s cattleman Rufe Ryker (played by the great character actor Emile Meyer) in Shane:

RUFE RYKER

Right? You in the right! Look, Starrett. When I come to this country, you weren’t much older than your boy there. We had rough times, me and other men that are mostly dead now. I got a bad shoulder yet from a Cheyenne arrowhead. We made this country. Found it and we made it. We worked with blood and empty bellies. The cattle we brought in were hazed off by Indians and rustlers. They don’t bother you much anymore because we handled ’em. We made a safe range out of this. Some of us died doin’ it but we made it. And then people move in who’ve never had to rawhide it through the old days. They fence off my range, and fence me off from water. Some of ’em like you plow ditches, take out irrigation water. And so the creek runs dry sometimes and I’ve got to move my stock because of it. And you say we have no right to the range. The men that did the work and ran the risks have no rights?

Emile Meyer as Ryker in “Shane”

A great villain speech possesses three attributes.

First, it displays no repentance. The devil makes his case with full slash and swagger. His cause is just and he knows it.

Second, eloquence. A great villain speech possesses wit and style.

Third, impeccable logic. A villain speech must be convincing and compelling. Its foundation in rationality must be unimpeachable. When we hear a great villain speech, we should think, despite ourselves, “I gotta say: the dude makes sense.”

Here’s Wall Street CEO John Tuld (Jeremy Irons at his unrepentant best) after laying waste to the life savings of thousands in Margin Call.

Jeremy Irons as John Tuld in “Margin Call”

JOHN TULD

So you think we might have put a few people out of business today? That it’s all for naught? You’ve been doing that everyday for almost forty years, Sam. And if this is all for naught, then so is everything out there. It’s just money; it’s made up. Pieces of paper with pictures on them, so we don’t have to kill each other just to get something to eat. It’s not wrong. And it’s certainly no different today than it’s ever been. 1637, 1797, 1819, ’37, ’57, ’84, 1901, ’07, ’29, 1937, 1974, 1987—Jesus, didn’t that one fuck me up good—’92, ’97, 2000, and whatever we want to call this. It’s all just the same thing over and over; we can’t help ourselves. And you and I can’t control it, or stop it, or even slow it. Or even ever-so-slightly alter it. We just react. And we make a lot of money if we get it right. And we get left by the side of the road if we get it wrong. And there have always been and there always will be the same percentage of winners and losers, happy foxes and sad sacks, fat cats and starving dogs in this world. Yeah, there may be more of us today than there’s ever been. But the percentages, they stay exactly the same.

How will we know your character is the villain if you don’t give him (or her) a great villain speech?

[Hats off to the writers of the above gems: J.C. Chandor for Margin Call; A.B. Guthrie, Jr. from a novel by Jack Schaefer for Shane; Stanley Weiser and Oliver Stone for Wall Street.]

January 26, 2018

The Key to It All

Sherlock Holmes pays attention. His big details are the ones ignored as little. His knowledge of crimes and human nature come from his own experiences and from books and reports. He reads of wrongdoings, scandals, atrocities and the like, in reports from other countries, and he is a devoted reader of The Times’ “Agony” column.

Holmes is fiction, but what he observes is not—nor are his sources.

The Times did have an “Agony” column. It’s an aged rabbit hole worth diving into. The personal advertisements that ran in it aren’t so far from what’s found in this online world of ours. (Read a compilation of selected ads in the 1881 book The Agony Column of the “Times” 1800-1870 via Archive.org)

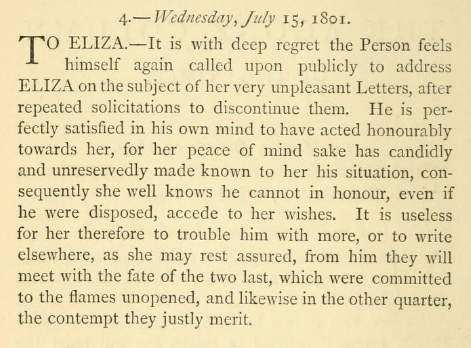

Here’s a clip of one ad, dated Wednesday, July 15, 1801:

From The Agony Column of the “Times” 1800-1870

Go deeper into the “Agony” column’s ads and you’ll find more of what was on the minds of Holmes’ clients, and neighbors, and the random passersby. You’ll find themes. The same story played out over and over—and on and on into this century. Two hundred and some years later, the ads of the “Agony” column sit well with online posts of today.

They speak to experiences and plotlines that outlast all of us.

At the end of the world, it will be the cockroaches and these plotlines hanging together.

Arthur Conan Doyle was observant himself. He had to be in order to gift Holmes with such powers of perception. They see what’s in plain site.

At the beginning of A Bohemian Scandal, John Watson visits Sherlock Holmes. Holmes states that Watson has been getting himself “very wet lately,” that “he has a most clumsy and careless servant girl,” and that he didn’t know Watson had gone into “practice again.”

Watson asks Holmes how he knows this.

Holmes shares the observations that led him to the facts:

“It is simplicity itself,” said he; “my eyes tell me that on the inside of your left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. Hence, you see, my double deduction that you had been out in vile weather, and that you had a particularly malignant boot-slitting specimen of the London slavey. As to your practice, if a gentleman walks into my rooms smelling of iodoform, with a black mark of nitrate of silver upon his right forefinger, and a bulge on the right side of his top-hat to show where he has secreted his stethoscope, I must be dull, indeed, if I do not pronounce him to be an active member of the medical profession.”

In The Man with the Twisted Lip, a client presents Holmes with a letter from her husband—a husband who has been missing and is believed to be murdered. Upon a look at the letter, Holmes observes that, though the letter might have been written by the husband, it was addressed and mailed by someone who was decidedly not the husband.

The client asks Holmes how he can be so sure. Holmes describes the facts in plain view on the envelope.

“The name, you see, is in perfectly black ink, which has dried itself. The rest is of the greyish colour, which shows that blotting-paper has been used. If it had been written straight off, and then blotted, none would be of a deep black shade. This man has written the name, and there has then been a pause before he wrote the address, which can only mean that he was not familiar with it.”

While investigating a murder in The Boscombe Valley Mystery, Holmes needs only to investigate the murder site in order to locate the murder weapon and to identify the physical characteristics of the murderer. As is his way, Watson reports on everything that occurrs:

The Boscombe Pool, which is a little reed-girt sheet of water some fifty yards across, is situated at the boundary between the Hatherley Farm and the private park of the wealthy Mr. Turner. Above the woods which lined it upon the farther side we could see the red, jutting pinnacles which marked the site of the rich landowner’s dwelling. On the Hatherley side of the pool the woods grew very thick, and there was a narrow belt of sodden grass twenty paces across between the edge of the trees and the reeds which lined the lake. Lestrade showed us the exact spot at which the body had been found, and, indeed, so moist was the ground, that I could plainly see the traces which had been left by the fall of the stricken man. To Holmes, as I could see by his eager face and peering eyes, very many other things were to be read upon the trampled grass. He ran round, like a dog who is picking up a scent, and then turned upon my companion.

“What did you go into the pool for?” he asked.

“I fished about with a rake. I thought there might be some weapon or other trace. But how on earth–”

“Oh, tut, tut! I have no time! That left foot of yours with its inward twist is all over the place. A mole could trace it, and there it vanishes among the reeds. Oh, how simple it would all have been had I been here before they came like a herd of buffalo and wallowed all over it. Here is where the party with the lodge-keeper came, and they have covered all tracks for six or eight feet round the body. But here are three separate tracks of the same feet.” He drew out a lens and lay down upon his waterproof to have a better view, talking all the time rather to himself than to us. “These are young McCarthy’s feet. Twice he was walking, and once he ran swiftly, so that the soles are deeply marked and the heels hardly visible. That bears out his story. He ran when he saw his father on the ground. Then here are the father’s feet as he paced up and down. What is this, then? It is the butt-end of the gun as the son stood listening. And this? Ha, ha! What have we here? Tiptoes! tiptoes! Square, too, quite unusual boots! They come, they go, they come again–of course that was for the cloak. Now where did they come from?” He ran up and down, sometimes losing, sometimes finding the track until we were well within the edge of the wood and under the shadow of a great beech, the largest tree in the neighbourhood. Holmes traced his way to the farther side of this and lay down once more upon his face with a little cry of satisfaction. For a long time he remained there, turning over the leaves and dried sticks, gathering up what seemed to me to be dust into an envelope and examining with his lens not only the ground but even the bark of the tree as far as he could reach. A jagged stone was lying among the moss, and this also he carefully examined and retained. Then he followed a pathway through the wood until he came to the highroad, where all traces were lost.

“It has been a case of considerable interest,” he remarked, returning to his natural manner. “I fancy that this grey house on the right must be the lodge. I think that I will go in and have a word with Moran, and perhaps write a little note. Having done that, we may drive back to our luncheon. You may walk to the cab, and I shall be with you presently.”

It was about ten minutes before we regained our cab and drove back into Ross, Holmes still carrying with him the stone which he had picked up in the wood.

“This may interest you, Lestrade,” he remarked, holding it out.

“The murder was done with it.”

“I see no marks.”

“There are none.”

“How do you know, then?”

“The grass was growing under it. It had only lain there a few days. There was no sign of a place whence it had been taken. It corresponds with the injuries. There is no sign of any other weapon.”

“And the murderer?”

“Is a tall man, left-handed, limps with the right leg, wears thick-soled shooting-boots and a grey cloak, smokes Indian cigars, uses a cigar-holder, and carries a blunt pen-knife in his pocket. There are several other indications, but these may be enough to aid us in our search.”

Lestrade laughed. “I am afraid that I am still a sceptic,” he said. “Theories are all very well, but we have to deal with a hard-headed British jury.”

“Nous verrons,” answered Holmes calmly. “You work your own method, and I shall work mine. I shall be busy this afternoon, and shall probably return to London by the evening train.”

“And leave your case unfinished?”

“No, finished.”

“But the mystery?”

“It is solved.”

“Who was the criminal, then?”

“The gentleman I describe.”

“But who is he?”

“Surely it would not be difficult to find out. This is not such a populous neighbourhood.”

Lestrade shrugged his shoulders. “I am a practical man,” he said, “and I really cannot undertake to go about the country looking for a left-handed gentleman with a game leg. I should become the laughing-stock of Scotland Yard.”

“All right,” said Holmes quietly. “I have given you the chance. Here are your lodgings. Good-bye. I shall drop you a line before I leave.”

Having left Lestrade at his rooms, we drove to our hotel, where we found lunch upon the table. Holmes was silent and buried in thought with a pained expression upon his face, as one who finds himself in a perplexing position.

“Look here, Watson,” he said when the cloth was cleared “just sit down in this chair and let me preach to you for a little. I don’t know quite what to do, and I should value your advice. Light a cigar and let me expound.”

“Pray do so.”

“Well, now, in considering this case there are two points about young McCarthy’s narrative which struck us both instantly, although they impressed me in his favour and you against him. One was the fact that his father should, according to his account, cry ‘Cooee!’ before seeing him. The other was his singular dying reference to a rat. He mumbled several words, you understand, but that was all that caught the son’s ear. Now from this double point our research must commence, and we will begin it by presuming that what the lad says is absolutely true.”

“What of this ‘Cooee!’ then?”

“Well, obviously it could not have been meant for the son. The son, as far as he knew, was in Bristol. It was mere chance that he was within earshot. The ‘Cooee!’ was meant to attract the attention of whoever it was that he had the appointment with. But ‘Cooee’ is a distinctly Australian cry, and one which is used between Australians. There is a strong presumption that the person whom McCarthy expected to meet him at Boscombe Pool was someone who had been in Australia.”

“What of the rat, then?”

Sherlock Holmes took a folded paper from his pocket and flattened it out on the table. “This is a map of the Colony of Victoria,” he said. “I wired to Bristol for it last night.” He put his hand over part of the map. “What do you read?”

“ARAT,” I read.

“And now?” He raised his hand.

“BALLARAT.”

“Quite so. That was the word the man uttered, and of which his son only caught the last two syllables. He was trying to utter the name of his murderer. So and so, of Ballarat.”

“It is wonderful!” I exclaimed.

“It is obvious. And now, you see, I had narrowed the field down considerably. The possession of a grey garment was a third point which, granting the son’s statement to be correct, was a certainty. We have come now out of mere vagueness to the definite conception of an Australian from Ballarat with a grey cloak.”

“Certainly.”

“And one who was at home in the district, for the pool can only be approached by the farm or by the estate, where strangers could hardly wander.”

“Quite so.”

“Then comes our expedition of to-day. By an examination of the ground I gained the trifling details which I gave to that imbecile Lestrade, as to the personality of the criminal.”

“But how did you gain them?”

“You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles.”

“His height I know that you might roughly judge from the length of his stride. His boots, too, might be told from their traces.”

“Yes, they were peculiar boots.”

“But his lameness?”

“The impression of his right foot was always less distinct than his left. He put less weight upon it. Why? Because he limped–he was lame.”

“But his left-handedness.”

“You were yourself struck by the nature of the injury as recorded by the surgeon at the inquest. The blow was struck from immediately behind, and yet was upon the left side. Now, how can that be unless it were by a left-handed man? He had stood behind that tree during the interview between the father and son. He had even smoked there. I found the ash of a cigar, which my special knowledge of tobacco ashes enables me to pronounce as an Indian cigar. I have, as you know, devoted some attention to this, and written a little monograph on the ashes of 140 different varieties of pipe, cigar, and cigarette tobacco. Having found the ash, I then looked round and discovered the stump among the moss where he had tossed it. It was an Indian cigar, of the variety which are rolled in Rotterdam.”

“And the cigar-holder?”

“I could see that the end had not been in his mouth. Therefore he used a holder. The tip had been cut off, not bitten off, but the cut was not a clean one, so I deduced a blunt pen-knife.”

Sherlock Holmes pays attention to what’s going on around him.

The key to building relationships and contacts, to pitching, to writing—to pretty much everything—is to pay attention.

Every mistake is a lesson.

Every success is a building block.

Every person met is a mentor.

Every location visited is a scene.

Get out AND get lost in every story you can find.

They will inform every part of your work, from your creation to your marketing. Just take a look at Doyle’s work for proof.

(If you do choose to get lost in stories, Gutenberg.org’s collection of Arthur Conan Doyle’s works is a good place to visit. For audiobook fans, Stephen Fry’s narration of Holmes’ adventures is wonderful. It’s been my companion for some time.)

January 24, 2018

Ask Yourself, "What Does the Villain Want?"

For James Bond villains, the answer is easy: world domination.

The Night King and the Army of the Dead. When we know what these suckers want, we can write the next season of “Game of Thrones”

That’s a pretty good want.

Here are a few others:

To eat your brain.

To eat your liver.

To eat you, period.

Or even better:

To destroy your soul.

To destroy your soul and laugh about it.

If you’re keeping score, the answers to the above (among others) are 1. All zombie stories, 2. Hannibal Lecter, 3. The shark, the Alien, the Thing, etc., 4. the Body Snatchers, 5. the devil in The Exorcist.

Why is Hillary Clinton such an inexhaustible object of hate to the Right? Because she, in their view, wants all five of the above.

(For the same notion from the Left, see Donald Trump.)

The hero’s “want” often changes over the course of the story. She may start out in Act One wanting her marriage to succeed, only to evolve by the end of Act Three into wanting to come into her own as an individual.

But the villain’s “want” remains the same from start to finish.

Identify it.

Be able to articulate it in one sentence or less.

Then build your story around it.

If we know what the Army of the Dead want, we know what our heroes in Game of Thrones’ next season are up against and what they have to do to combat it.