Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 56

October 6, 2017

Chum or Cream? Asinine or Aristotle?

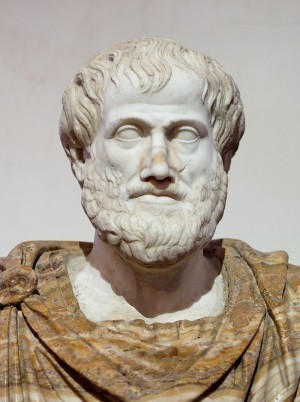

What was so great about what Aristotle had to say — or how he said it?

Congratulations Kazuo Ishiguro, on being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature–and thank you for your stories. Bringing this back from September 2, 2016.

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s book The Buried Giant, the dragon Querig is blamed for cursing the land with “a mist of forgetfulness.” With each breath, she exhales a mist with the power to shroud those within her range in amnesia.

The mist is an unforgiving thing, wiping out the good and the bad memories. Pain and Happiness exit stage left hand and hand, with Experience and Knowledge joining them.

Axl, an old man at the center of The Buried Giant, can’t understand why a young soldier is familiar to him because Axl has no memory of his own youth. And when Axl meets an old knight, the same occurs. Why is the knight familiar to Axl and Axl in turn familiar to the knight? How could Axl, just an old man, know anything of fighting and battles?

With the emotional and experience memories, the mist stole the memories of how the The Buried Giant’s many characters connected with each other. A strange woman asks Axl’s wife, “How will you and your husband prove your love for each other when you can’t remember the past you’ve shared?”

As the story continues, we find that Merlin was responsible for infusing Querig’s breath with amnesia. In the post-Arthurian period in which the story takes place, the previously warring Britons and Saxons live in peace because they can’t remember the genocide and other atrocities that occurred. Oblivion is Bliss.

The Internet reminds me of Querig’s breath, with Information playing the role of the mist.

Where cream used to rise, chum resides, fueling the top feeders.

All the information bombarding our in-boxes and Facebook walls and Twitter feeds, is “new” — and there’s so much of it to wade through.

Instead, ignore the now and look to the past. Think about how “they” did it before the Internet.

How did Aristotle get people to listen to him? He wasn’t the only philosopher on the block. Why him?

How did Christopher Columbus pull together a trip to the New World, without a Go Fund Me campaign to back him?

How did the Wright Brothers convince people to go for a ride when crashing was a reality?

Why VHS instead of Betamax? Or Coke or Pepsi? Or Apple or Samsung?

Slay the shit at the top and dive deep for how people “did it” before all the tech and info access and you’ll find personal relationships and hard work. You’ll find some assholes, too, but in general, you’ll find that everything you need to know today has existed for thousands of years. Instead of figuring out how to game Facebook and Amazon for success today, figure out what Aristotle did it to achieve longevity hundreds and hundreds of years later.

Find out what has always worked, rather than trying to sort out what works right now.

October 4, 2017

Tricks of the Trade, #11

The theme of the past months’ “Reports from the Trenches” has been

How can we resuscitate our story after it crashes?

This is no easy issue, as all of us know. It feels to me, being in the middle of the process right now, like I’m grabbing my story by the belt, turning it upside-down and shaking it till all the loose change tumbles out of its pockets.

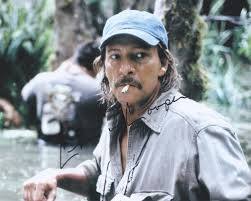

Jack Nicholson as J.J. Gittes in “Chinatown”

We’re trying to get our story to give up its secrets.

To spill its guts.

To sing like a canary.

Here’s a trick that sometimes works:

Bring the story back to where it started.

In other words, circle back at the end to a character from the beginning. Or a setting. Or a mood or a phrase or a thought.

Remember the opening of Chinatown? Jack Nicholson as private eye Jake Gittes is meeting in his office with a client named Curly (Burt Young), who happens to be a skipjack fisherman working out of San Pedro. Jake shows Curly surveillance photos of Curly’s wife, cheating with another man. Curly breaks down, clutching in tears at Jake’s window blinds.

CURLY

She’s just no good!

JAKE

Curly, go easy on the Venetian blinds, will ya?. I just had ’em

installed last week.

The scene ends with Curly apologizing to Jake for not being able to pay his bill. Curly exits. We think the scene’s purpose was just to introduce Jake and his world as an L.A. private detective.

Cut to the movie’s final reel. Jake is now trying to save another client, the glamorous but desperately troubled Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) and her daughter Katherine from the clutches of her dastardly father, Noah Cross (John Huston.)

To whom does Jake turn for help?

Curly.

(We have not seen Curly in the movie at all since that opening scene.)

To settle his arrears with Jake, Curly agrees to take Evelyn and Katherine aboard his fishing boat and help them flee by sea to Ensenada. The attempt ends in tragedy of course, but the circling back of the story from Curly-at-the-start to Curly-at-the-finish is a nice piece of (almost) closure.

And this doubling-back maintains the movie’s image system of water (the dam, the dry L.A. River, the Oak Pass Reservoir where Hollis Mulwray is drowned and Jake almost loses his nose, et cetera et cetera around the villain Noah Cross’s corrupt scheme of bringing irrigation water to Los Angeles toward the end of making it into a world-class city.)

In Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer (winner of the National Book Award for Fiction in 1962 and one of my all-time faves), the protagonist and narrator Binx Bolling describes this same doubling-back phenomenon from a different and very interesting perspective:

A repetition is the re-enactment of past experience toward the end of isolating the time segment which has lapsed in order that it, the lapsed time, can be savored of itself and without the usual adulteration of events that clog time like peanuts in brittle.

Binx loves movies. He observes than when he sees an old film, say, twenty years after he saw it in its original release, the interval of time between the viewings becomes unified and heightened.

That’s what happens to our readers, yours and mine, if we can pull off this trick in our stories.

At the risk of becoming long-winded, consider the following hypothetical:

You and I are writing a book about King Arthur.

Excalibur in the Stone. Is there some way we can circle back to this?

Early on, we have the scene of the young Arthur drawing the sword from the stone. Great scene. Destiny. The idea of “the chosen one,” etc.

Now, four hundred pages later, we’ve reached the part where Arthur’s kingship has turned sterile and empty. Lancelot has betrayed him. Guinevere has proved untrue. The Round Table has fallen apart.

Arthur, in despair, accompanied by only a handful of his last royal retainers, trudges through a dark wood in winter.

We’re stuck, you and I.

We’ve lost our story.

But wait …

Is there some way we can “double back?” Can we somehow return to some scene or moment or character that went before—and thereby re-energize our story?

Arthur and his men enter a clearing. The sun is setting. A cold wind rips through the forest. The prospect of an endless, bitterly cold night looms. Suddenly …

Arthur senses something familiar in the clearing.

OMG, this is the site of the Stone!

The stone from which Arthur drew the sword so many years ago.

The place looks terrible. Gone to seed, overgrown, neglected. But this is the place, all right.

Arthur dismounts, crosses expectantly to the Stone …

See what I mean? We can play this scene five different ways and every one of them works.

The doubling back of Stone Then to Stone Now creates a “repetition,” within whose spell the intervening years cohere, for good or ill. And from that cohesion can arise insight, a twist in the story, a fresh resolve.

Suppose, in our Arthur story, the despondent king steps to the Stone, hoping for some flash of magic.

But the Stone is silent.

Inert.

It’s just another ordinary rock.

We have reached our hero’s All Is Lost moment.

What epiphany can possibly follow?

Perhaps Arthur, from the depths of despair, senses that his challenge is to keep on struggling for the good and the true even in the absence of destiny, with no support except that which he can generate from his own resources.

That ain’t bad.

That’s a scene.

It works.

In fact it turns the whole story.

And we, the writers, got to it by using a trick.

We asked ourselves, “How can I double back and make the story circle around to some place or moment or character from which it began?”

[I tried this, by the way, in the book I’m wrestling with now. It didn’t work. I couldn’t find a ‘double-back’ that made sense.

[That’s okay too. Not every trick works every time.

[Perhaps my destiny is to struggle on, supported only by my own resources.

[Or perhaps the Stone retains its magic, subtly nudging me to that seemingly hard but actually liberating and empowering Epiphanal Moment.]

September 29, 2017

Everyone Is Nobody Sometime

Let’s go back twenty or so years and look at the world through the eyes of an ambitious journalist intent on creating something original. Again, this material is from a series of posts I wrote over at www.storygrid.com.

Let’s pretend you’re Malcolm Gladwell.

It’s midish-1998. Google won’t start up until September. Facebook is more than five years away. The Kindle launch is almost ten years away and not one publisher sees eBooks as a viable product. In August, Amazon.com publicly acknowledges that it plans to sell more than just books and CDs.

Everything that is tipping or will tip in the new century hasn’t happened yet. People are worried about Y2K and the Internet is for nerds. Remember that?

Your first book is due to Little Brown in nine months give or take and you have a huge pile of stuff covering your desk. You have reams of printout with hours and hours of transcribed interviews. You have coffee stained Moleskin notebooks packed with your chicken scrawl from the scores of research papers and books you’ve read. You’ve got post-it notes, backs of envelopes, tear sheets, and scraps of newspaper…all with some intellectual fragment that you’ll need to assemble your first draft.

What’s sits before you are the support materials you’ll use to convince readers of the veracity of your Big Idea. An idea that you’ve globally categorized as The Tipping Point—an often used phrase among physicists, epidemiologists, and sociologists in academia, but not yet well known in the civilian world.

You have deep-dived into the core principles of the phenomenon—small changes can add up all at once to an explosive effect…one far greater than the sum of its causes—and compiled evidence of its occurrence in the discipline that fascinates America’s most passionate strivers—the practical economics of entrepreneurial business.

You’re confident that the business book buyer will be intrigued. And if there are enough case studies about how Wendy’s hamburgers launched or how a mass market came to buy pet rocks or beanie babies or tulips, then all will be well.

Your book will perform inside of that niche and you’ll not have trouble getting a contract to write another one.

You could leave it at that.

Instead, you’ve boldly taken your Big Idea even further and propose that The Tipping Point is not just a cool thing in evidence across multiple academic disciplines, but in fact, it is a deeply ingrained phenomenon that can explain “unexplainable” human behavior. Like why crime in New York City plummeted in the 1990s, why toddlers find themselves addicted to the inane television show Blue’s Clues, and even why teenagers in Micronesia have been known to kill themselves in epidemic proportions.

Your ambitions are all well and good, but how exactly will you tell The Tipping Point story? How do you connect all of this diverse evidence in a way that will hold anyone’s interest? Not just the business book buyer, but also the firefighter or the stay at home mom who have limited downtime for reading.

This isn’t to say that you are convinced that anyone—beyond the very insular book and magazine publishing industry—will really care about what you’ve pieced together. Chances are few will. Over one hundred thousand books are published each year. How could your little riff (all in, you don’t see this book being longer than 75,000 words) on how you put together a dog’s breakfast of academic research and worked up a grand idea break through?

You have no idea. Right now, you’ve got a much bigger problem.

How do you write your book so that anyone, not just The New Yorker magazine reader, will find themselves compelled to finish it?

This is your mission. You’re hoping it won’t prove impossible.

As you sit with your coffee, you can’t help but wonder how in the hell you got yourself into this daunting mess? You consider if there is a graceful way out of it… But you’re like a woman at 42 weeks gestation on her way to the hospital… There’s no turning back.

For Gladwell staring down his first draft, and for all who find themselves driven to think and write down and share what they’ve contrived, how he got to that desk probably seemed like the result of some cruel accident.

It wasn’t.

By 1998, Gladwell was thirty-four, with a snowballing confluence of genetics and environment and what some would call magic directing him to write The Tipping Point. It’s obvious with the most cursory review of his story.

No one but he could have written it.

I’m convinced that all great art is personal. So deeply personal that it magically transforms into the universal, and if you’re Thucydides or Copernicus or Plath your work transcends time.

While it isn’t necessary to “know” the artist to appreciate the art, artists in training can learn indispensable lessons about the inner war and how to keep on keeping on by piecing together the life history’s of those who seemingly pulled genius out of thin air.

When I took on this project, Storygridding the Tipping Point, I decided not to request an interview with Malcolm Gladwell. If granted a sit down with him, I would have inevitably gotten lazy. I would asked him the same old variations of “What’s your process?” “How do you get your ideas?” “Do you panic under deadline?” “How do you deal with criticism?” While I’m sure he’d have some fascinating answers to these softballs, ultimately I wouldn’t get much out of the experience. God knows he wouldn’t either.

What floats my boat is being a bit of a Story detective. I love to read and analyze my favorite books and then investigate the circumstances in which they were written. As Gladwell would say, I want to know the “context” of the creation. No one sits down and has a great Story dictated to them by an otherworldly presence. They grind it out of themselves with the otherworldly presence standing by with critical inspiration when they hit the wall.

If you don’t grind…the Muse moves on to find someone else who does.

So for fun, the next few posts will be about that–pretending to be Malcolm Gladwell before he became “bestselling writer” Malcolm Gladwell.

September 27, 2017

Let There be Blood

I know I keep promising to finish with these “Reports from the Trenches.” But I’m still deeply in the muck and mire myself, and each week brings a fresh insight.

So …

This week’s flash is about blood ties.

Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen. How tightly can the writers bind these two characters?

I first learned this trick from a wonderful book called Writing the Blockbuster Novel by Albert Zuckerman. Mr. Zuckerman is Ken Follett’s literary agent and something of a legend in the business. Blockbuster can be heavy going because it presents its case in such detail, but I recommend it highly nonetheless.

Here’s one of the book’s brilliant insights:

Tie your characters as tightly together as possible.

What do Zuckerman/Follett mean by this?

They mean if one of your female characters is going to murder one of your male characters, make them husband and wife.

If Luke must duel Darth Vader to the death, make them scion and patriarch. And don’t forget Princess Leia. Throw her into the gene pool too.

Blood ties.

If you can’t bind your characters within the family web, make them lovers.

Make them intimate friends.

Laertes should be Hamlet’s best buddy, and Ophelia should be Laertes’ sister, and Polonius his father. If Hamlet’s mom, the queen, is gonna murder his dad and marry the usurper, let that dastard be Hamlet’s father’s brother.

Game of Thrones works this magic every week.

I’m not a geek for the show (I can’t really tell Daenerys from Cersei or Sansa Stark from Arya), but I know that 99% of GOT’s dramatic power comes from the fact that everybody is related to everybody else. Even the dragons were raised from eggs. They’re members of the family too.

When brother betrays brother, that’s drama.

Wife murders husband.

Best friend seduces best friend’s wife.

The Godfather gave us blood ties across three generations.

The Sopranos played like a family album.

Even Breaking Bad, whose central family was bound primarily by the secrets each member was keeping from every other, was about teacher-student bonds, fellow-criminal bonds, etc.

Which brings me back to this Report from the Trenches.

When our novel crashes and we’re desperately seeking to unearth the core story beneath, Albert Z’s trick can help us disinter that elusive sucker.

Three days ago I took a male and female character who had been unrelated and made them brother and sister.

Wow, did that help!

If you can’t make your characters related by blood, it can be almost as good to give them shared backstories.

Paul Manafort was a partner in Black, Manafort and Stone, powerful Washington lobbyists who represented numerous overseas clients. The Stone in that trio is Roger Stone, the agent provocateur and long-time pal of Donald Trump. Stone’s mentor was Roy Cohn, who was Joseph McCarthy’s chief counsel in the Army-McCarthy hearings. Cohn also mentored the young Donald Trump.

See what I mean?

Tie your characters together.

Give them intertwined roots.

For the reader, the fun of the story is unraveling these hidden links.

September 22, 2017

The Pool Is 12 Feet Profound

1+3+5+3+7+1+9+23+48+5 will always equal 105.

You can add the middle numbers last or add the second and fifth numbers first, and you’ll come up with the same answer.

However, it’s different with words.

Present the exact same words, in the exact same order, and the exact same format, to different individuals, and you’ll receive a different response every time.

That’s the beauty of words. As individuals, and when combined, words carry the experiences of their readers with them. Each individual will leave with a different interpretation.

Look to Lois Lowry’s introduction to the now-a-major-motion-picture edition of The Giver:

I had always received lots of letters from kids, frequently writing as a class assignment (one began, “This is a Friendly Letter”). Over the years, of course, they have more often become emails. But that didn’t compare to the mail about The Giver: first of all for the volume—the sheer number of them (even now, twenty years later, they still come, sometimes fifty to sixty in a day). But now the letter writers were different. Sure, many of them were still kids. But a startling number were much older. And the content was no longer the school assignment letter, the obligatory “I thought this was a pretty good book.” Instead the letters were passionate (“This book has changed my life”), occasionally angry (“Jesus would be ashamed of you,” one woman wrote), and sometimes startlingly personal.

One couple wrote to me about their autistic, selectively mute teenager, who had recently spoken to them for the first time—about The Giver, urging them to read it. A teacher from South Carolina wrote that the most disruptive, difficult student in her eighth grade class had called her at home on a no-school day and begged her to read him the next chapter over the phone. A night watchman in an oil refinery wrote that he had happened on the book—it was lying on someone’s desk—while making his rounds (“I’m not a reader,” he wrote me, “but man, I’m glad I came to work tonight”). A Trappist monk wrote to me and said he considered the book a sacred text. A man who had, as an adult, fled the cult in which he had been raised, told me that his psychiatrist had recommended The Giver to him. Countless new parents have written to explain why their babies have been named Gabriel. A teacher in rural China sent me a photograph of beaming students holding up their copies of the book. The FBI took an interest in the two-hundred-page vaguely threatening letter sent by a man who insisted he was actually The Giver, and advised me not to go near the city where he lived. A teenage girl wrote that she had been considering suicide until she read The Giver. One young man wrote a proposal of marriage to his girlfriend inside the book and gave it to her (she said yes). But a woman told me in a letter that I was clearly a disturbed person and she hoped I would get some help.

Diverse interpretations arrive with books and films and paintings, because we each take what the artists create and make their works our own.

For me, their works double as keys.

I don’t read books, or listen to music, or watch films, or examine paintings for enjoyment. I access them because they unlock my imagination. When my mind gets interpretin’ things start unlockin’. I have a hard time reading F. Scott Fitzgerald, because whenever I get a few lines in, the lock opens and the ideas roll out, or they start clicking together, like the innards of an old fashioned watch. In these moments, I don’t want to know what the artists intended. All I want is to swim in my own mind, ride my own thought waves.

But, sometimes . . . Interpretations are bad. (Insert record scratch.)

Last week, the word profound arrived with my 4th grader’s homework. Her understanding was that it held the same meaning as the word deep. This understanding came from an example that used the word profound:

The ocean is profound.

Using the ocean sentence as guidance, she created her own sentence:

The pool is 12 feet profound.

She understood profound to mean deep, but her understanding of deep wasn’t quite there. She was dancing around the flat and sharp areas flanking that sweet tuned spot, hence the 12 feet profound pool.

She didn’t quite get it, and that’s ok. We talked about the 12 feet profound pool (and the prodigious bear) and how sometimes words don’t mean what you think they do, and how it’s good to think about the pairing and sequencing of words. We also talked about interpretation, and using the best words to say what you mean.

This led to me reading the 4th grader, and the 8th grader who was hovering, an e-mail to Steve. I’ve never done this before, but it was a teaching moment, and I didn’t share the person’s name, so . . .

Hi, I am XXXX, (A Follower). I’m 17 years old and I am from XXXXXX. In my school I must make a presentation of an American writer and talk about a book by the same person. I chose you because I get excited with your book “The virtues of war”. My teacher says that we must answer the following questions: “Why do you write this?”, “When he wrote this?” and finally “What does the work represent for him?”, I need to finish this in three weeks. Could you answer the questions, please? I would be very greateful .. I’ll be attentive for your Answer

The 4th grader gave me a blank stare and left the room. (A shame she hasn’t perfected the one cocked eyebrow she’s been practicing. Would have fit well here.)

The 8th grader told me he thought it made sense. The student needed answers that only Steve could provide, so he did the right thing.

I asked my son what happens when his own teachers ask about the writings of someone like Abraham Lincoln, who you can’t contact for answers. What does he do?

Pause.

I explained that what the teacher likely wanted was for the student to do his own research first. Steve’s done interviews and has an entire site on which he discusses the craft of writing and why he’s made certain decisions in the past. There’s a lot “out there” already to help the student get started. Instead, he took a short cut. My interpretation of the student’s letter was that he didn’t want to do any heavy lifting.

I pointed to the 8th grader’s copy of The Giver and asked if he’d read the introduction.

No.

I sent him to the page on which Lowry wrote about the student who once e-mailed the request, “Please list all the similes and metaphors in The Giver.”

The 8th grader knows of similes and metaphors and what a pain it is when you have a teacher who wants you to guess the exact meaning, without discussing the meaning she has in her head, so . . . He got it. However, he was still on the fence because he is 13 and heavy lifting isn’t what 13 year olds identify with best, so… I picked up the hammer and drove my point home. The student wanted an answer in three weeks. He asked a complete stranger to put down his life’s work to do someone else’s homework.

Would you do someone else’s homework?

The 8th grader doesn’t enjoy doing his own homework, so he jumped off the fence and landed on solid ground next to me.

This led to the 8th grader going down the rabbit hole of disbelief. How could anyone do that to Steve? Does this happen a lot? What’s wrong with that guy?

The 4th grader came back to hold up my door frame and share that she thought the student was lazy. (The 4th grader’s super power is hearing. She’s both the holder and sharer of secrets in our house.)

I stepped back because it felt like we were heading into trolling territory.

I’m the one who stated that I didn’t think the student wanted to do heavy lifting. I still believe that, but lazy? Is it the same thing? And per my son’s comments, did the student understand the mistake he was making?

So we talked about how to write letters and our intentions, and a few other things related to words and writing.

The 4th grader slipped out again.

The 8th grader talked through his negative comments.

We agreed the student was on the clueless side and that maybe the work was overwhelming, which is why he asked for help. We also agreed that it’s best to do as much as you can on your own before asking others for help—and work on using the best words.

In addition to being unexpected, the conversation was enjoyable, and even . . . profound. Not 12 feet profound, but . . . yeah . . . profound.

September 20, 2017

Macro Resistance and Micro Resistance

I was having dinner a few nights ago with a young screenwriter and a big-time Hollywood literary agent. The writer was joking that her career had stalled on the “C” list.

A moment from “THEM,” 1954. Maybe mutated ants would be better than spiders.

“If I had you for a year,” the agent said, “I’d get you high on the ‘A’ list.”

The agent was serious, and a serious discussion followed. Most of the talk centered on the politics of career advancement. When I got home, though, I found my thoughts migrating to the craft aspects.

How would a true, knowledgeable mentor elevate a talented writer’s career? How would he advance it one level or two levels higher? What aspects of craft would he accentuate? What changes would he insist upon?

Step One, I think, would be to really hold the writer’s feet to the fire.

The mentor would make the writer truly accountable to her own talent.

Conception of project.

The young writer comes in with an idea for a movie or a book.

Is the idea good enough?

Is it big enough?

Is it truly original?

Will it attract “A”-level talent? Director? Actors?

The agent/mentor would insist that the writer consider alternatives and variations on the idea. Is Version One the absolute best way to do this? “Okay, the story is about giant spiders invading from Mars. Would crustaceans be better? How about if they came from Venus?”

Execution of story.

In my own days as a screenwriter, my agents (and they were all good) would, with only minor tweaks, pretty much accept the draft I gave them. That was the version they took out and tried to sell.

Looking back, they should have pushed me harder.

I have another friend, a literary agent who runs her own boutique agency, a really good one. She does exactly that with her clients. She sends them back to the drawing board over and over.

Our theoretical mentor should be just as hard on his young, talented writer.

“You’ve told the story as an action adventure from the female scientist’s point of view. Is this the best way? What alternatives have you considered? Why did you reject those?”

Maximization of character drama.

“Have we plumbed the detective’s dilemma deeply enough? He’s in love with the lady scientist but he’s conflicted because he has a pet tarantula at home and he finds himself relating sympathetically to the spiders. How can we deepen this issue and make it play most dramatically in the climax?”

Why, in today’s post, am I asking these questions?

Because they apply 100% to our ongoing (sorry, I can’t stop) series, “Reports from the Trenches.”

In other words, they’re the same questions you and I have to ask ourselves when the first draft of our novel or screenplay goes south.

We need to be our own mentors, our own agents, our own editors.

We have to hold our own feet to the fire.

Have we settled (we must ask ourselves) for the First Level version of our story, of our execution, of our characters? Did we grab the first idea and run with it?

Our mentor/agent/editor would force us to be accountable. He or she would demand that we push on to Level Two and Level Three and beyond.

Which brings me to subject of Resistance.

If I were writing The War of Art again today, I’d add a section on the subject of Micro Resistance.

Macro Resistance is the global kind. It’s the self-sabotage that stops us from doing our work, period.

But many of us have beaten that monster. We can sit down. We can bang out the pages.

But Micro Resistance is sabotaging those pages.

Micro Resistance strikes inside the book or screenplay. We’re working, but we’re not working deeply enough. We’re settling. We’re not pushing the action, we’re not considering enough alternatives, we’re not demanding that scenes and sequences and dramatic relationships extract the last bit of juice from their potential.

Micro Resistance is what’s been kicking my butt on this re-do I’m working on.

Why have I not pushed deeply enough?

Because it’s hard work.

It’s painful.

It’s risky.

I’ve avoided the effort out of fear of failure.

I’ve accepted stuff that a more mentally-tough writer would have rejected.

Resistance, you and I must never forget, is constant and unrelenting.

It fights us in every phrase and every sentence.

It always wants us to settle for the easy, the shallow, the first level.

Do you have that agent, that mentor, that editor who will force you to be true to your talent?

If you do, you’re incredibly lucky.

But you and I need to cultivate that mentor inside our own heads.

We’re the writers. Accountability for our work lies with us.

We have to be that agent/mentor/editor ourselves.

September 15, 2017

The Six Word GPS

This is the next post in my series about Big Idea Nonfiction…and it’s a good one for fiction writers too. When we hit a wall in our work (and we will) we need to settle ourselves so that we can outflank Resistance’s insistence that we’re wasting our time…that we’ll never finish…that we’re idiots for trying… This post from www.storygrid.com a while back is a tool to get you back in the fight to complete your creation.

What actually happens when we take on a project and work it until completion? Is there a universal experience of sorts that anyone who strikes out to solve a problem faces?

I think there is.

As Steve Pressfield writes about in Do the Work, at first, we have a big rush of energy. We bang out page after page of copy or lay out a killer plan to start a new business…

And invariably there comes a time when we reach an “all is lost” moment. We stumble on a problem that seems unsolvable. We wish we’d never started the damn thing in the first place. We hit a wall.

And just when we find ourselves starting to recover, we discover that our stupor has slowed us down enough for a whole field of weeds to take root and grow around us. We may have a lead on getting over the big problem (the wall), but a whole slew of ancillary problems arise around it.

Should you hack down the weeds on a retreat back to safer ground? Or somehow claw your way over the wall? Or beam yourself out of that predicament entirely?

When you hit this moment in your work (and I’ll admit right now that I have) it’s time to pull out your project’s map and get your bearings again.

This is exactly what I need to do with my Storygridding The Tipping Point project. Right now. I can literally feel Resistance coming at me from a whole slew of directions. Things that I’d shrug off only weeks ago have me stymied.

For a nonfiction writer (and fiction too), the way to fight Resistance in this time of panic is by using six wonderful words (Who, What, Where, When, Why and How). These six words will serve you as an infallible global positioning system.

If you are seriously out of your element, answering these six questions will tell you to retreat, hack down some smallish problems and resume. Ninety-nine percent of the time, though, answering them will tell you how to climb over the wall and keep moving. But most importantly, they will keep you from pulling the pin on the whole thing. They are your own private Obi Wan Kenobis.

Let’s break those six one-word questions down.

I always start with Why.

1. Why am I storygridding The Tipping Point?

I know that The Tipping Point is the contemporary category killer of Big Idea Nonfiction. A visual Story Grid that shows the ways in which Malcolm Gladwell masterfully holds the reader’s attention while satisfying the reader’s “want” from the book (prescriptive application of the idea) and the reader’s subconscious “need” from the book (wisdom) will prove that the Story Grid methodology can serve as valuable a tool for nonfiction writers as it does for fiction writers.

That is why I’m doing it. To help Nonfiction Big Idea writers do their work.

2. What the hell are Story Grids for anyway?

Infographic Story Grids are editorial and inspirational tools to show writers how classic works abide millennia old Story principles. By seeing how master storytellers solve story problems, writers can better identify and fix their own story problems.

Literally showing Big Idea Nonfiction writers how Malcolm Gladwell solved the very problems they face will inspire them and give them the tools necessary to find their problems and fix them. And to find their strengths and make them even better.

3. Who do Story Grids benefit?

Story Grids benefit writers, readers, actors, directors, producers, advertising executives, entrepreneurs, CEOs, politicians, stay at home moms, teachers, bartenders, customer service reps, fast food franchise managers…anyone who recognizes that understanding and mastering Story is an essential skill in our ever-expanding global village.

It is the skill that will drive one’s ability to make a living in the not too distant future.

4. How will it change the way we see the Big Idea work of Nonfiction?

A Story Grid for The Tipping Point will show nonfiction writers how to build a convincing argument that has nuance and ambiguity, all the while telling a global action adventure story akin to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. It will show writers how to create a longform work of art out of a single simple idea.

5. Where will I go from here?

In order to create a Story Grid for The Tipping Point, I must complete two documents—a MACRO analysis of the book (The Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point) and a MICRO analysis of the book (The Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point). Once I have those two documents, I can combine them to form the data points and curves of the final infographic.

6. When will I be finished?

Right now, I have the top quarter of the MACRO complete (Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point) and I am half way through the MICRO (The Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point. I cannot complete The Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point until I’ve completed my Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point.

The Macro needs a Micro analysis to support it, just as the Micro needs the Macro analysis to support it. It makes sense that I’ve hit a wall in the middle of working on both. Once the Micro is complete, the Macro will come into clear focus. And vice versa.

So what should I do now?

I need to focus on the MICRO Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point. Once I’ve completed that document, I’ll be able to fill in the rest of my Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point. And then I can create the Story Grid for The Tipping Point.

And so back to the MIRCRO I go.

September 13, 2017

“Trenches #1,” Redux

[Not sure why, but my instinct tells me to re-run this post (the first in our “Reports from the Trenches” series) today, rather than posting a new one. Sometimes things need to be seen twice. I think this might be one of those times. So … here goes, in its entirety:]

I’m gonna take a break in this series on Villains and instead open up my skull and share what’s going on in my own work right now.

It ain’t pretty.

Joe and Willy, from two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Bill Mauldin

I’m offering this post in the hope that an account of my specific struggles at this moment will be helpful to other writers and artists who are dealing with the same mishegoss, i.e. craziness, or have in the past, or will in the future.

Here’s the story:

Eighteen months ago I had an idea for a new fiction piece. I did what I always do at such moments: I put it together in abbreviated (Foolscap) form—theme, concept, hero and villain, Act One/Act Two/Act Three, climax—and sent it to Shawn.

He loved it.

I plunged in.

Cut to fifteen months later. I sent the finished manuscript (Draft #10) to Shawn.

He hated it.

I’m overstating, but not by much.

Shawn sent me back a 15-page, single-spaced file titled “Edit letter to Steve.” That was April 28, about ten weeks ago.

Every writer who is reading this, I feel certain, has had this identical experience. Myself, I’ve been through it probably fifty times over the years, for novels, for screenplays, for everything.

Here was my emotional experience upon reading Shawn’s notes:

I went into shock.

It was a Kubler-Ross experience. Shawn’s notes started out positively. He told me the things he liked about the manuscript. I knew what was coming, though.

When I hit the “bad part,” my brain went into full vapor lock. It was like the scene in the pilot of Breaking Bad when the doctor tells Bryan Cranston he’s got inoperable lung cancer. The physician’s lips are moving but no sound is coming through.

Here’s the e-mail I sent back to Shawn:

Pard, I just read your notes and as usually happens, I’m kinda overwhelmed. As you suggest, I’ll have to re-read a bunch of times and chew this all over.

MAJOR, MAJOR THANKS for the effort and skill you put into that memo. Wow.

I’m gonna sit with this for a while.

Can you read between the lines of that note? That is major shell shock.

I put Shawn’s notes away and didn’t look at them for two weeks.

In some corner of my psyche I knew Shawn was right. I knew the manuscript was a trainwreck and I would have to rethink it from Square One and start again.

I couldn’t face that possibility.

The only response I could muster in the moment was to put Shawn’s notes aside and let my unconscious deal with them.

Meanwhile I put myself to work on other projects, including a bunch of Writing Wednesdays posts. But a part of me was thinking, How dare I write anything ‘instructional’ when, after fifty years of doing this stuff, I still can’t get it right myself?

There’s a name for that kind of thinking.

It’s called Resistance.

I knew it. I knew that this was a serious gut-check moment. I had screwed up. I had failed to do all the things I’d been preaching to others.

After two weeks I took Shawn’s notes out and sat down with them. I told myself, Read them through one time, looking only for stuff you can agree with.

I did.

If Shawn’s notes made eight points, I found I could accept two.

Okay.

That’s a start.

I wrote this to Shawn:

Pard, gimme another two weeks to convince myself that your ideas are really mine. Then I’ll get back to you and we can talk.

Three days later, I read Shawn’s notes again.

This time I found four things to agree with.

That was progress. For the first time I spied a glimmer of daylight.

Two days later I began thinking of one of Shawn’s ideas as if I had come up with it myself.

Yeah, it’s my idea. Let’s rock it!

(I knew of course that the idea was Shawn’s. But at last, forward motion was occurring. I had passed beyond the Denial Stage.)

I’ll continue this Report From the Trenches next week. I don’t want this post to run too long and get boring.

The two Big Takeaways from today:

First, how lucky any of us is if we have a friend or editor or fellow writer (or even a spouse) who has the talent and the guts to give us true, objective feedback.

I’d be absolutely lost without Shawn.

And second, what a thermonuclear dose of Resistance we experience when faced with the hard truth about something we’ve written that truly sucks.

Our response to this moment, I believe, is what separates the pros from the amateurs. An amateur at this juncture will fold. She’ll balk, she’ll become defensive, she’ll dig in her heels and refuse to alter her work. I can’t tell you how close I came to doing exactly that.

The pro somehow finds the strength to bite the bullet. The process is not photogenic. It’s a bloodbath.

For me, the struggle is far from over. I’ve got weeks and weeks to go before I’m out of the woods and, even then, I may have to repeat this regrouping yet again.

[NOTE TO READER: Shall I continue these “reports from the trenches?” I worry that this stuff is too personal, too specific. Is it boring? Write in, friends, and tell me to stop if this isn’t helpful.

I’ll listen.]

September 8, 2017

Hemingway Did Not Non-Summit

This post returns today with high hopes of deep sixing the non-summit. However, it knows it can’t go it alone. Please help. Instead of pushing procrastination, let’s make sure that the only thing non-summits are pushing is daisies.

A summit is the highest of the high. It is the top of a mountain. The apex. The peak. The zenith.

If it is a summit meeting, it is a meeting of individuals at the peak. Think Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin during WWII.

If you’ve been following this blog, you know my feelings about the trending use of the word summit to describe events, workshops, interviews, get-togethers, and a long list of other things that are not summits of either the mountain or meeting variety.

Another piece to add:

These non-summits are a form of procrastination.

When you’re at the base of an actual summit, don’t hold a meeting. Climb to the top instead.

One more piece:

These non-summits have the potential to steal your work’s soul—and your soul’s work.

Stick with me a bit here, for a short ramble.

In her Scientific American article “On writing, memory, and forgetting: Socrates and Hemingway take on Zeigarnik,” Maria Konnikova opened with the story of psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik.

In 1927, Gestalt psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed a funny thing: waiters in a Vienna restaurant could only remember orders that were in progress. As soon as the order was sent out and complete, they seemed to wipe it from memory.

Zeigarnik then did what any good psychologist would: she went back to the lab and designed a study. A group of adults and children was given anywhere between 18 and 22 tasks to perform (both physical ones, like making clay figures, and mental ones, like solving puzzles)—only, half of those tasks were interrupted so that they couldn’t be completed. At the end, the subjects remembered the interrupted tasks far better than the completed ones—over two times better, in fact.

Zeigarnik ascribed the finding to a state of tension, akin to a cliffhanger ending: your mind wants to know what comes next. It wants to finish. It wants to keep working – and it will keep working even if you tell it to stop. All through those other tasks, it will subconsciously be remembering the ones it never got to complete. Psychologist Arie Kruglanski calls this a Need for Closure, a desire of our minds to end states of uncertainty and resolve unfinished business.

I think this might be why the mornings are so magical for work. The mind just spent hours chewing over unfinished business. Yes, it brought up some family drama I wanted to avoid, but it did a ton of heavy lifting on unfinished work that is of importance. It made the connections between all the fragments clear, helped sew up the loose ends, fuse together the matching pieces. It made the struggle to understand—and view—the path ahead clearer. It’s why I try to wake before the kids and try to avoid talking, even of the e-mail chatter sort, in the early hours. There’s a magic there that’s gone by 9 AM, so I want to catch it within easy reach at 5 AM.

Maybe this is why counseling works, too. Once you talk it all through, you come closer to being able to let go, to find closure.

I just finished Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami and there’s a scene when one of the characters requests that a fellow traveler of the same world burn her manuscript. It isn’t for publication or reading. It is her life. She had to put it all down. Remember everything. Get it out. Once she added that final period, her body died and her soul—or whatever you want to call that “it” thing about her, that essence—moved to a different world.

Once she completed her story, she was able to move onto the next place.

But what if you talk through all of your work—all of your dreams—without actually doing them? You risk moving on, though that’s the last thing you really want.

Back to Konnikova’s article, this time with a quote from an interview Ernest Hemingway did with George Plimpton, for the Paris Review:

“… though there is one part of writing that is solid and you do it no harm by talking about it, the other is fragile, and if you talk about it, the structure cracks and you have nothing.”

Again, from Konnikova:

Hemingway’s words came from experience. When his wife lost a suitcase that contained all existing copies of his short stories, the work was, to his mind, gone for good. He had written himself out the first time around. He couldn’t recapture it—whatever it was—again. He even fictionalized the process in the short story, “The Strange Country”: the writer whose stories have been lost finds it impossible to remember. “It’s useless,” he tells his sympathetic landlady. “Writing [the stories] I had felt all the emotion I had to feel about those things and I had put it all in and all the knowledge of them that I could express and I had rewritten and rewritten until it was all in them and all gone out of me. Because I had worked on newspapers since I was very young, I could never remember anything once I had written it down; as each day you wiped your memory clear with writing as you might wipe a blackboard clear with a sponge or a wet rag.”

I have a friend who attended an event led by Tony Robbins recently. It wasn’t called a summit, but she left inspired. She didn’t talk through every bit of her life or her dreams. She listened and learned. I’m not opposed to these events, but the ones that continue to come into Steve are increasingly from individuals who are holding meetings at the base camp—who have talked about climbing to the summit for years, but have never given it a shot.

One more thing from Konnikova’s article is this quote from Justin Taylor:

“Don’t take notes. This is counterintuitive, but bear with me. You only get one shot at a first draft, and if you write yourself a note to look at later then that’s what your first draft was—a shorthand, cryptic, half-baked fragment.”

Non-summits shouldn’t be drafts, but that’s what they are—and for some, a draft is an idea closed. It isn’t refined. It isn’t as good as it can be, but it is closed—and not reopened.

One small rant:

If you are early in your career, you don’t warrant your own summit. You just don’t.

The 18 year old who wants to be a life coach needs to go experience life first. Do something. You have something important to say? Go walk the talk. Get out of the house and away from all the screens. Go LIVE and CREATE.

Age, of course, isn’t a determining factor, but one used in the above because I’ve run into more teenage life-coach wanna-be’s.

*With age, the exceptions are related to individuals such as Malala Yousafzai, an extraordinary woman, who became the youngest Nobel Prize laureate at age 17. I’ll listen to her with every ounce of myself because her life experiences, her daily walk, are more than just talk. She’s lived her beliefs. She fought/continues to fight when others have hidden.

The 18 year old who has read a ton of Nietzsche but is still living off his parents? Not so much.

Climb the mountain. Don’t stop at the base. Your words are your oxygen, and if you use them all, you risk running out of breath within view of your goal, but without what you need to attain it.

September 6, 2017

How Writers Screw Up, Part One

For part of my time in Hollywood, I worked with a partner. I called him “Stanley” in Nobody Wants To Read Your Sh*t so I’ll continue that protocol here.

Chris Cooper won the Oscar as Best Supporting Actor for his role in Charlie Kaufman’s “Adaptation”

Stanley was an established writer. He had been the force behind two big hits. I was the junior member of the team.

Stanley was also a major sci-fi enthusiast. He had read all the magazines, the short stories, the novels, the collections. One of the ways Stanley developed movie projects (he was a producer too) was to option a short story or novella by, say, Philip K. Dick and then adapt the piece as a screenplay.

Sci-fi short stories and novels [Stanley used to say] almost never work in the form in which we find them and acquire them. They’re part-stories. They’re half-stories.

This reality was a giant plus in Stanley’s eyes, because it meant he could option these pieces for peanuts, whip them into shape, and sell them as movies.

Stanley made me read a raft of these sci-fi works.

See how they all stop halfway through? The writer will have come up with a brilliant premise, like the idea of “replicants” and “blade runners” or the concept of erasing or implanting memories. But they almost never take the idea to a dramatic conclusion. They stop at Act One.

Or they’ll come up with fantastic heroes but without the right villains. There’s no theme. There’s no climax. There’s no third act.

Stanley didn’t fault these sci-fi writers. He was in awe of them just for their gift for coming up with such wild-and-crazy premises.

In Stanley’s view it was our job—the screenwriters who would adapt these novellas and short stories—to finish the work that the original writer had started.

Our job was to save her.

To make her stuff work

Have you seen Adaptation, written by the great screenwriter Charlie Kaufman? The movie is not science fiction but the problem its writing presents is exactly what we’re talking about here. The adapting screenwriter, “Charlie Kaufman,” accepts an assignment to write a script based on a Susan Orlean article in the New Yorker. The piece is about orchids.

In other words, there’s no readily apparent movie there.

The adapting writer, “Charlie Kaufman,” has to come up with a hero, a villain, an Act One, Act Two, Act Three.

If you haven’t seen the movie, Netflix it. It’s hysterical, with great performances by Nicolas Cage, Meryl Streep, and Chris Cooper.

But back to what we were talking about.

Why am I bringing this subject up?

What’s the point of exploring half-stories and part-stories?

Because that is exactly the problem you and I have when we write a novel and it crashes halfway through.

[Sorry, you guys. I promised last week I would stop writing these “Reports From The Trenches,” but I’ve had a few more ideas since then so I’m gonna keep going for another week or two.]

What I’m trying to say is that when you and I write a draft of a novel and the damn thing DOESN’T WORK, we find ourselves in the same position as Stanley after he options a Philip K. Dick short story or Charlie Kaufman when he signs a contract to adapt a magazine piece about flowers.

Nicolas Cage as Charlie Kaufman and Meryl Streep as Susan Orlean

We are stuck with a half-story.

The only difference is we did it ourselves.

We didn’t have to acquire the half-story from another writer; we banged the sucker out all by ourselves.

Again, why am I beating this nearly-extinct horse?

Because before you and I can chart our course for Tahiti, we have to know WHERE WE ARE EMBARKING FROM.

This challenge is, as I observed earlier in this series, “writing at the Ph.D. level” and “overcoming Resistance at the Ph.D. level.”

Our assignment, yours and mine as we stand over the smoldering wreckage of our half-story/half-novel, is to

Acquire objectivity about the material

Detach ourselves emotionally from our own prior work

Mentally regroup, so that we can summon our courage

Open our minds to every new and fresh story possibility

Start again from Square One.

Can we do it?

Will we fold?

Is the challenge too daunting?

Are we too attached to our original (half) story to let it go?

Lemme rephrase what I said about Ph.D.s.

This isn’t about a distinction between academic levels.

This is about the difference between being a professional and being an amateur.

We may have thought, you and I, when we started out in this business (I use that word deliberately, in contrast to “art”) that it was easy.

It ain’t.