Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 58

July 28, 2017

The Hard Is What Makes It Great

I’m a few years and thousands of pages into a project—and am starting over.

I had an “all is lost moment.”

It hit around the time Steve published his first “From the Trenches” article.

I cried.

I sulked.

I said something shitty to my husband.

I thought my world was falling apart—that everything that could go wrong had, or did, or soon would.

I was wrong.

I’m alive.

I’m working.

I’m healthy.

Most important: My kids and husband are healthy and doing their amazing things.

What helped me hurdle the moment?

Steve #2.

In his “Resistance at the Ph.D. Level” article, Steve wrote about another version of himself, a 2.0 version who would tackle the the messy pieces Steve 1.0 created.

Steve #2 has certain advantages that Steve #1 doesn’t.

First, he starts with a clean slate.

It’s not his fault that this project is all bolloxed up.

He’s the surgeon.

He’s the Fix-it Man.

He’s the pro from Dover.

Steve #2 will come in, sew this mess up, and get it back on his feet.

I know this #2 person he spoke of, but it was reading his experience that helped get Callie #2’s ass back where her heart wanted to be.

Five days earlier I posted the piece “Every Battle Makes Me Stronger.”

Easier said than done.

I know the process Steve described.

I know the Kubler-Ross stages he shared in “Report from the Trenches, #1.”

But . . . The experience is easier identified on the other end, once you hit the acceptance stage.

I’m there now.

Callie #2 isn’t thinking about what she coulda, woulda, shoulda.

She’s looking toward the finish line.

She’s thankful that Steve and Shawn are sharing their experiences.

She knows it’s easy to forget that we all go through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, whether it is restarting or reviving a project, raising a child, or wrapping our heads around life period.

It’s hard.

Cue Jimmy Dugan:

It’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great.

July 26, 2017

Report from the Trenches, #4

What exactly am I doing as I reconceive/reconstruct/rewrite a project that I’m already eighteen months into, based on some pretty stark “do it over” notes from Shawn?

In the files I’m basically talking to myself. “What would happen if Manning didn’t know X in Chapter Seven, instead of the way I have it now where he does know? What would he do under these new circumstances?”

Then I’m writing scenes.

I’m spitballing sequences.

Ooh, a car chase! That might work. Manning chases Bad Guy X into New Environment Y and, in a twist at the end, the Bad Guy tells him “Q didn’t kill Z, H did.”

I like that.

That’s good.

Let’s keep going.

(In other words, I’m basically writing the whole damn thing over, twisting it this way and that in the hope that it’ll contort itself into what it really wants to be.)

When Shawn applies his Story Grid analysis to a completed manuscript that a writer has submitted to him, he goes scene-by-scene, like a movie or stage director. He asks of each scene, “What is the inciting incident? What are the progressive complications? What’s the climax?” He asks, like an actor, “What does Character X want in this scene? What obstacles stand in her way? What does Character Y want in this scene? Do X and Y clash? Do the scene’s stakes escalate? How has the story advanced, or twisted, from the beginning of this scene to the end?”

I was lazy the first time through this story.

I winged it too much.

I didn’t think hard enough.

I didn’t ask and answer all the questions I had to.

I settled for scenes and sequences that I felt in my bones weren’t working, or weren’t working well enough.

It’s hard to go back and do what you didn’t do the first time. It’s like you’re in a dark forest and you’ve just walked past the same tree for the third time.

Are we getting anywhere?

Or are we just getting more lost?

Nobody said this shit was easy.

July 21, 2017

Subjective Truth, Editors and Resistance, #2

In my last post I wrote about how editors’ primary jobs are to deliver objective truth to their writers.

If the writer hasn’t specifically outlined and delivered step-by-step instructions in his proposed How-To book, the editor tells the writer that their choice of Genre requires them to do so.

The editor then proposes changes to the work that’s On The Page in order to best comply with the writer’s stated intentions that are again already On The Page. If it’s a How-To Take Charge of Your Finances kind of book, the editor suggests that the writer move one piece of material and put it elsewhere.

Teach them how to literally balance their checkbook before you tell them about cash flow…

She suggests that the writer consider adding additional material, perhaps photographs or line drawings, to better instruct the potential reader.

Delivering objective truth is empowering.

The editor can’t help but feel smug when she’s able to point out all of the things that the writer failed to do. And giving the writer a clear suggestion about how to construct a better persuasive argument requires creative role-playing too. The editor has to think about the “reader,” the final arbiter of the project’s merit and direct the writer to best meet potential reader expectations.

Editors who do this work are invaluable.

Steve’s last post was about some of the very specific objective truths I laid out for him with his latest fiction project.

I have six core questions that I ask myself over and over again when I work on a project. And yes, I use these same questions for nonfiction too.

Whenever I get confused about what it is I’m trying to explain to the writer about their work, I go back to these questions. They tell me specifically where the writer went off track and help me put myself in the shoes of potential readers of the story. How can I help the writer meet the expectations of the reader, but also create something immensely personal and unique?

And because I’ve built an entire editing method around these fundamental story structure questions, they serve as a common language to use when I communicate with an exhausted writer.

Here they are:

What’s the Genre?

What are the Conventions and Obligatory Scenes of the Genre?

What’s the Point of View/Narrative Device?

What are the global objects of desire?

What is the Controlling Idea/Theme?

What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff of the global story?

Seems pretty straightforward right?

Just ask these questions, write down the answers and share the results with the writer.

So what am I talking about when I talk about the role Resistance plays in the editorial life?

This is the realm of Subjective Truth.

This is the soft underbelly of an editor’s brain, the place where Resistance sinks his teeth into time and time again. These are the truths that Resistance will tell an editor to withhold. These are the things that could rub the writer the wrong way…the things that could really piss them off to the point where the relationship irreparably fractures.

Specifically, subjective truth concerns questions number four and number five: What are the global objects of desire? and What is the Controlling Idea/Theme?

Because the answers to these two questions are never literally expressed to the reader in a work of fiction (they are Off the Page) an editor who decides to explore potential answers to them and share those answers with the writer has to shed his smug “know it all” objective truth giving cloak and become vulnerable.

And no one likes to be vulnerable.

Here’s a little story from the Love Story Event that Tim Grahl and I ran last February about the difference between objective and subjective truth.

Steve came to the event and agreed to do a couple of hours at the end about the Inner War of writing/creating. He told our friend Seth Godin about it and Seth agreed to come too.

So one of the questions someone put forth to all of us was something about how we pick our projects.

When it was my turn to answer, I told a story about a day years ago when I was in a serious funk. Looking for something meaningful to do with my life, I came up with a pretty cool idea about starting a publishing house dedicated to spotlighting the “heartbreakers” that literary agents couldn’t find a home for. It was a concept akin to Franklin Leonard’s Black List in Hollywood…the best books that publishing houses didn’t “get” chosen by the best literary agents who desperately tried to place them.

I was excited about the idea but afraid it would fail. And if it failed, I would fail. So I asked Seth for a half hour of his time so I could pitch him the idea. He’d then tell me if it would be something that could work. Having his approval was important to me and I remember being very nervous about his response. If he didn’t like it, maybe he would think I was stupid.

I went through my big speech. Seth listened and thought about it for about 15 seconds (that’s a long time in a one on one meeting). He said he thought it could work. I’d have to get buy-in from literary agents and there’d be a challenge of re-positioning the stuff so it didn’t seem like warmed over dregs from the rejection pile, but that it was doable.

That’s it.

And then he said “what else?”

I didn’t have anything else. I’d booked a half hour and only had one idea to talk about.

And then as I told this story at the conference I talked about all of the things that ran through my head after that experience…very personal truths about my ego and my unquenchable thirst for third party validation etc. etc.

And then Seth piped in to lighten up the moment with something like “Geez Shawn…it wasn’t that dramatic.”

And that was objectively true. For Seth and anyone else who could have witnessed the exchange it was just another meeting between two guys drinking tea.

But the subjective truth of that meeting was, for me, extraordinary. The experience was akin to the bargaining stage in Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s Change Curve, you know the one right before depression and the all is lost moment? I had to reevaluate the way I looked at work and at projects in general. My whole book blacklist idea was a bargaining stage for me to avoid changing my worldview.

So telling someone else about subjective truth puts the storyteller in a very vulnerable position. It opens you up to “Geez it wasn’t that dramatic” rejoinders.

You have to do it anyway.

When editors personally extrapolate truths that come to them after reading a writer’s work and then decide to share those subjective truths with the writer, they have to beat Resistance to do so.

What if what I think isn’t the intention of the writer?

What if the writer thinks that I’m trying to tell them what to write?

What if he finds my ideas so stupid and ridiculous that he loses faith in my intellectual capabilities?

Instead, Resistance says to just tell the writer that you don’t have a clear understanding of the objects of desire and the controlling idea of the thing and leave it at that. Let them plumb the depths of subjective truth and figure it out. Why should you risk pissing them off? Keep on that smug “know it all” cloak and let the writer sort that shit out.

The reason why the editor has to push herself to reveal her subjective truths about what could be behind the words on the page for the writer is that it will make the work better.

And that’s why the editor is there in the first place. To serve the work.

The writer will undoubtedly disagree with the editor’s wild extrapolations about what his book is really about and what it serves in the grander scheme of humanity, but those ideas will loosen the writer’s inner muse. It will serve as a little icepick that chips away at the inner truths locked within the writer’s psyche. The ones that the work is there to express.

Remember that the editor is there to serve the work.

An editor’s objective truth tells the writer what to fix in their draft.

An editor’s subjective truth inspires the writer how to fix his draft.

Expressing subjective truth requires courage.

Why?

Because you have to intuit what the writer’s controlling idea is when it is not necessarily clear yet to the writer!

So you’re basically putting forth an idea that may or may not be obvious to the writer himself.

And you have to not only put forth what you think that idea is but also then explain why it’s not rising to the surface and how to remedy that failure.

Huh? How is that possible?

A writer, especially the professional writer, knows that they need to trust, for lack of a better term, his “muse.”

That is, they have to map out a story with very general destination points. They plan a cross-country trip from Portland Maine to Portland Oregon and simply figure out the states that they’ll consider driving through on the way. This is Steve’s Foolscap Method.

So if they want to get off the Pennsylvania Turnpike and head south for a while as they write, they allow for that possibility. They assume the muse is in the car with them and that if she tells them to take an exit, they will.

What often happens though, especially when the work is a serious internal exploration, is that the writer will be oblivious to why the muse made them go through Weirton, West Virginia when a straighter path would have taken them through Steubenville, Ohio.

The editor must have the courage to not just explain to them where they went off track, but why they did.

Now telling a writer that the manuscript that they’ve sent you is on the surface a story about pushing the devil back down in his hole, but is really about how each and every one of us struggles to find meaning in our lives, ain’t easy.

Resistance rears its ugly mug to the editor in these moments of reflection.

–What right do you have to tell a writer what they’re thinking subconsciously?

–Who made you such an expert? You’ve never written a novel yourself…

–What if they tell you to F-off?

–What are you going to do when you lose your business partner because of your ham-handed attempts to tell him what he means when he’s writing?

And on and on.

But again, I have to serve the work first and worry about what Steve thinks about me personally second.

Steve understands what it takes for me to put this stuff out there.

This is why we work so well together.

He knows my insides are ripping themselves apart the second I hit send on that email with the Edit Letter to Steve attached.

So what does he do with this knowledge?

Even though he’d love to punch me in the solar plexus and tell me I have no idea of what I’m talking about?

He sends me this email a few hours after I send him my letter.

Pard, I just read your notes and as usually happens, I’m kinda overwhelmed. As you suggest, I’ll have to re-read a bunch of times and chew this all over.

MAJOR, MAJOR THANKS for the effort and skill you put into that memo. Wow.

I’m gonna sit with this for a while.

How great is that?

July 19, 2017

Report from the Trenches, #3

The last two weeks’ posts have gotten a lot of positive response, so apparently they have struck a nerve. I confess though, as I sit down to write today’s Report #3, that I’m not really sure exactly WHAT is proving so helpful. Obviously I want to stay in that vein. So, spitballing a bit, here goes …

There are rules for working with this dude …

The specific question readers might be asking right about now is, What exactly did Shawn’s notes say? And, How exactly did you, Steve, respond?

The bulk of Shawn’s problem with the manuscript I gave him was that I had violated conventions of the genre I was working in.

The genre, as Shawn identified it, is Redemptive Horror Thriller. The parallel works he cited were The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby.

In other words, a story where the villain is the devil.

How had I violated the conventions of this genre? A lot of ways, but here’s one, verbatim from Shawn’s notes:

The trick of this sort of story, though, is to ride out the uncertainty about the true nature of the evil until “all Hell breaks loose.”

So the reader gets off on the “could this really be the devil?” element long enough for them to start to believe and then…you hit them with the irrational and green goo spew like that pivotal scene in THE EXORCIST.

This is what drives the suspense in supernatural horror stories like THE EXORCIST and ROSEMARY’S BABY. The protagonists in both of those stories were victims (Father Karras in THE EXORCIST and Rosemary in ROSEMARY’S BABY) and the promise from the positioning of the stories was:

“Yes…this is a supernatural Devil! Story!”

But…

The reader and the viewer of both of those stories needed evidence, a progressive narrative build to the revelation that the devil/supernatural is real and on stage.

Remember that in THE EXORCIST, the girl was taken to all kinds of doctors and had all kinds of tests and all possible explanations were eliminated before they brought in Max Van Sydow as the last resort to save her? That’s when the devil makes himself truly known…when the Exorcist arrives with Karras as his assistant.

Any of us as writers would KILL to get such incisive and helpful feedback, wouldn’t we?

It is GREAT to have a really smart editor.

Okay.

How did I respond? What did I take from this?

I could see that Shawn was right. So I read the manuscript over, re-outlining it scene-by-scene, with this objective in mind: How can I spool out the revelation of the villain’s identity, i.e. that he’s the devil, more slowly?

The protagonist of the story is a homicide detective.

Another of Shawn’s notes was that our detective wasn’t doing enough detecting. Clues were falling into his lap. It was too easy for him.

This was another issue I had to address.

I wrote two more fast outline-style passes of the story. One file I called Freewheelin’. The other I named Spitballin’. I wanted to keep loose. I wanted to throw a lot of stuff against the wall and see if anything stuck.

The allied character in the story (allied with the detective) is a female rabbi named Rachel. In the manuscript I sent to Shawn, Rachel knows all the occult backstory and she knows it from the start. She knows all about the devil and what nefarious scheme he is up to. Throughout Act One and Act Two she is trying to convince the detective of this, and he is resisting, refusing to believe.

I decided that that was 100% wrong.

I could respond to Shawn’s notes, I thought, by having the character of Rachel resist the detective. (The detective’s name is Manning.) That would force Manning to do more detective work. It would make him a stronger character, and it would involve the reader more because she could track along with Manning as he worked to unravel the mystery.

Pretty basic stuff, right? But I’ve only been doing this for fifty years, so I’ll give myself a pass on blowing this completely.

Anyway, here is part of the file I sent back to Shawn after having thrashed this stuff out for about four weeks:

Rethinking the character of Rachel. I’m going to change her character completely. This will be a HUGE CHANGE because its effects ripple through the whole story.

I’m gonna take your thought re Rachel’s attitude and actions and turn them on their head. Instead of being the person who already knows what’s happening and is trying in every scene to compel Manning to believe in it, we’ll have her FLEEING from Manning, clamming up (she still knows everything but in this new version refuses to tell it), doing everything in her power NOT to tell Manning anything. So he’ll have to do more detective work to find out. We’ll cut the scene where Rachel appears at DivSix and delivers all the goodies about “lamed vav” and “the victims are all Jews.” Manning will find these out on his own.

I spitballed a scene for Shawn. (“The Rebbe” is one of the murder victims. The devil’s human-form name is “Instancer.” “36RM” is short for Thirty-Six Righteous Men, a Jewish legend whose connotations include the End of Days, i.e. extinction of the human race.)

SCENE: Immediately after the murder of the Rebbe and the fleeing of Instancer (we’ll keep Manning conscious and still full of fight, even though he has tussled with Instancer), he spots Rachel, outside, lurking. As soon as she sees him, she bolts. A wild French Connection-type chase ensues across Brooklyn at night that takes Manning to an encampment of the dispossessed, into which Rachel flees deeper and deeper, finally diving into a derelict “van down by the river” (obviously hers) that she flees in further, before crashing into an abutment, where Manning and Dewey overtake her, guns drawn. Manning bursts into the van’s living compartment and finds it’s an Obsession Chamber, packed with Rachel’s computer, 36RM files, and, big as life on the wall, a blow-up photo of Instancer.

In other words, “Who the f**k are you? Who is Instancer? And how do you come to have all this shit?”

I realize that these notes and these scenes are project-specific and thus may be hard to make sense of, for the reader coming in cold. I’m featuring them in this post, however, in the hope that getting really specific will be the most helpful way to go, even if it’s a bit confusing.

To recap, Shawn’s notes to me made eight major points.

Today’s post touches on just one of them.

But it depicts clearly, I hope, the way an editor thinks, what he’s looking for when evaluating whether a story works or doesn’t (in this case, the writer—me—is guilty of violating the conventions of the genre he’s working in), and how he, the editor, articulates this to his writer.

Of course, you and I, if we don’t have a really good editor, have to do this evaluation on our own. Very hard to do.

The specifics in this post also, I hope, show how a writer responds to his editor’s notes. The big thing to keep in mind, I think, is HOW LONG it took me in this case—a full month.

This is the process.

I’ve gone through it, and so has Shawn, on just about every book we’ve worked on, with each other and with others.

It ain’t easy, and it ain’t pretty.

Next week: more specifics as we continue slogging through the jungle.

July 14, 2017

Every Battle Makes Me Stronger

I have no tears left to cry nor emotions to feel.

Instead of the heart keeping beat, the pounding in the gut plays metronome, a solid BOOM, BOOM, BOOM walloping the soul.

It doesn’t hurt, but Pain has numbed me.

I want to cry.

I want to scream.

I want to be back in my childhood room having a terrible two’s temper tantrum. I want to throw every stuffed animal, and book, and everything else I can get my hands on against the wall.

But I can’t.

I’m an adult.

I have kids.

I have a husband.

I have work.

And I have a choice to make.

Do I let Anger and Sadness and Rage overcome me?

Or do I let them go?

Or is there an in between?

Do I pick a few battles and let others go?

What to do?

My kids and my husband are my life.

If I have to sacrifice my work, I will.

But can I? Can I really let that piece of me go?

Or can I figure it out?

Can I really “have it all?”

Maybe I just need to “lean in” more.

Push harder.

Should I push harder?

And even if I push against that thing I’m fighting, it it really an opponent or just an immovable boulder?

In the past two weeks, Steve and Shawn have shared their raw truth.

The above is mine.

It is what my mind experiences as I struggle in all areas of my life.

Questions.

Doubt.

Confusion.

If you think that Resistance goes away when you reach a certain point in your career or your life, you’re mistaken.

The one thing I know for certain is that Resistance hunts all of us. He’s an equal-opportunity abuser.

Success is a magnet, not a shield when Resistance is lurking.

The other thing I know for certain is that the glorious feeling of slaying that bastard waits on the other side.

I don’t do Resistance.

I pound Resistance out of existence and then thank him for the workout.

And when he’s reincarnated (as he always is)? I pulverize him.

Every battle makes me stronger.

July 12, 2017

Resistance at the Ph.D. Level

Continuing our “reports from the trenches,” let me flash back briefly to last week’s post with the aim of setting today’s piece—Report #2—in a relatable time context.

General William Slim in Burma, 1943

The plot so far:

April 28, 2017. Shawn sends me his editorial notes on my new manuscript (my Draft #10.)

Same day: I go into shock.

Two weeks later: I summon the courage to read Shawn’s notes again. I succumb to shock a second time (though not quite as badly.)

Three days later: I read ’em one more time. Shock is receding.

Two days after that: I begin to actually grasp what Shawn is trying to communicate.

Fast-forward to today, July 10. I have outlined (new) Draft #11 in detailed, scene-by-scene form. I’m about halfway through the next pass of actually writing it.

Projection into future: Another five weeks to finish Draft #11. Will need at least two more drafts after that. Then send again to Shawn.

Future/future: possibly begin process all over again.

I wrote half-jokingly in last week’s post that this experience has had a heavy Kubler-Ross feel to it.

Alas, it’s true.

For sure I’ve been going through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression. The objective has been to get to the final stage—acceptance.

Acceptance meaning the ability to read Shawn’s notes objectively (or as objectively as possible) and respond to them like a professional, i.e. without ego, without defensiveness, without laziness or short-cut-itis.

The Big, Big Question:

How can I decide which of Shawn’s eight points I agree with and which I don’t?

This is Resistance at the Ph.D. level.

In other words, my ego/self-protectiveness/laziness/pride etc. is rejecting EVERYTHING Shawn is suggesting or proposing. Reading his notes for the first, and even the second time, I literally could not understand them. Not because Shawn hadn’t expressed himself with absolute clarity. He had. But just because the blow was too severe. It was a Mike Tyson shot to the solar plexus.

Yet I knew, in some hazy part of my brain, that Shawn’s notes were right. I trust him absolutely. I’ve seen him be right, over and over. He knows his shit, and he knows my shit.

Shawn’s notes are on the money, I’m certain. At least some of them. Probably most of them.

Problem: How do I come back from the fetal position and shake off that defensive armor of self-protection?

Because Resistance, bank on it, is loving every minute of this.

Resistance wants me to crumble.

Resistance wants me to deny, to dissent, to defend.

How do I defeat this diabolical entity?

Here are two things I did:

I recalled to mind the multiple horror stores that Shawn and other editors have told me over the years about writers self-destructing at precisely this moment in their process. In other words at the moment of semi-completion but not real completion. The moment of I-think-I’ve-nailed-it-but-I-really-haven’t-but-I-can’t-face-the-nightmare-of-having-to-regroup-and-start-again.

These stories will turn your hair white. The poor writer (and I can empathize completely, believe me) goes into shock/denial/defiance/rationalization. He fights back. He scorns his editor’s input. He stomps his feet, he digs in his heels. He refuses to make the changes.

Climax of tale: writer’s book dies, writer is never heard from again.

Okay.

I’m telling myself this. I’m scaring myself straight.

Rally, Steve. Suck it up, baby. Read Shawn’s notes again. Focus. Move back to the 30,000 foot view. Gain perspective.

Which of Shawn’s points do you agree with? Don’t just be tough on yourself, be tough on him. He’s human. He’s fallible. He can be wrong.

Trust your instincts, Steve. This is your book. Only you and your Muse can carry it to completion.

What do you think?

Which points do you agree with?

The second thing I did to help me through this moment was I reminded myself of how it works for novelists and screenwriters in Hollywood.

The system is

If Writer #1 can’t lick this script, fire him and bring in Writer #2.

I said to myself, “Steve, you’re fired.”

Thanks a lot, buddy, you took the story as far as you could. Now step aside. We’re bringing in Steve #2.

I told myself, “Steve, you’re hired.”

Welcome aboard, Big Guy. Here, read this piece of crap we just got in from Steve #1. Tear it apart if you have to. Just make it work.

I became Steve #2. (There may be a Steve #3 and #4 lurking to replace me when I screw the pooch too, but for now let’s put that out of our minds.)

Steve #2 has certain advantages that Steve #1 doesn’t.

First, he starts with a clean slate.

It’s not his fault that this project is all bolloxed up.

He’s the surgeon.

He’s the Fix-it Man.

He’s the pro from Dover.

Steve #2 will come in, sew this mess up, and get it back on his feet.

Sometimes you and I as writers have to play mind games with ourselves. We have to find a way to gain perspective, to seed ourselves with patience. I’m reading a terrific book now called Defeat Into Victory by Field Marshall Viscount William Slim. It’s a true memoir of the war in Burma, 1942-45, against the Japanese. The part of the book I’m reading now is the Defeat part. General Slim and the allies are getting their butts kicked.

The story is fall back, fall back, fall back. Rally, regroup, counterattack, get beaten again.

This is warfare at the Ph.D. level, as my friend Major Jim Gant says. It’s a dead ringer for our struggles as writers, yours and mine, when we receive and must absorb brave, insightful, constructive (but devastating) feedback on our work.

Next week we’ll get into specifics on this process of rallying back. I’m making it up as I go along. I’ll keep reporting to you, as long you think it’s helpful. Lemme know, please. It helps.

P.S. General Slim and his soldiers did stop the bleeding (after first losing all of Burma) and did, eventually, fight back and turn defeat into victory.

July 7, 2017

Editors and Resistance, #1

I’m going to take a break from my wonky analysis of Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point and give you my take on Steve’s post from Wednesday, “Report from the Trenches, #1.”

The central question I want to explore is “What form of Resistance do Editors face?”

Well, like the hedgehog, Resistance knows one important thing about the editorial process…

An Editor is a midwife. The only one who truly knows her value is the birther.

The Big R lies in wait inside this truth.

As Steve wrote, about 18 months ago, he sent me a global idea for a new novel.

And I ABSOLUTELY LOVED IT.

Why?

I’ll skip the commercial considerations…why it could be a huge hit! Suffice it to say that for someone like me who loves to think about the current cultural gestalt (the general “State of Story” we’re living in today) and the underlying need for our collective anxieties to find relief through compelling, but meaningful, story, Steve’s idea struck me as uniquely familiar. That phrase “uniquely familiar” is my favorite way of saying that a particular story innovates a primal genre.

That is, we go on a Story carpet ride because it’s familiar (we expect to have certain emotions stoked and they are) and then just as we start to think we know what’s coming next, it pulls the rug from under us and gives us the thrill of uncertainty…with the cathartic finish line leaving us exhausted but relieved. I’m not alone. There’s meaning in this world after all! Whew!

That’s nice, but here is the personal reason why I loved Steve’s idea. It’s perfect for him at this time in his creative pilgrimage. He’s confronting some big internal monsters in a unique way for him…in a genre he loves.

How do I know that?

My relationship with Steve is the second longest in my life. Yep, the only other person that I’ve had a longer partnership with is my wife.

Steve has seen me at my best and more importantly, he’s been with me at my rock bottom, when I’d lost faith not only in my profession but in myself. Mine own private all is lost moments. And vice versa.

No, we don’t give each other pep talks. We’ve never have Movie of the Week heart to hearts. Don’t forget that Steve’s a Marine and my finishing school involved retrieving ring pull cans of Iron City Beer for unemployed Steelworkers who kicked each other’s asses just to pass the time.

We just keep working together. We laugh about the darkness we both dive into again and again and again, knowing we have another guy in the foxhole with us even though we’re three thousand miles apart. He knows that I know what he’s going through and I know that he knows what I’m going through. Who cares if we ever have a hit…that’s enough.

So what is this writer/editor thing? What is the foundation of this relationship? What is the secret sauce that accounts for twenty odd years of working together?

I want to highlight that last sentence.

Long term collaborations in book publishing are rare…Perkins and Fitzgerald/Hemingway, Robbins and Didion, Gottlieb and Caro, Howard and Palahniuk… The reasons why they’re rare are innumerable. The business is just not built to encourage this sort of relationship. That’s because there is no amount of money or appearances on bestseller lists that compare to them. Which is dangerous for a corporation.

Here’s a clue about one of the ingredients of the secret writer/editor sauce from Steve’s post on Wednesday:

Shawn’s notes started out positively. He told me the things he liked about the manuscript. I knew what was coming, though.

So what was coming that Steve knew?

What was coming was the thing that tore me up to write…the proving ground where I had to battle Resistance every inch of the way.

SUBJECTIVE TRUTH

What does that mean?

Let’s start with the first thing I had to give Steve.

OBJECTIVE TRUTH.

Objective truth uses universal laws as its operating system. It works the facts, just the facts. It’s hard to debate the truth of gravity or rain or simple harmonic motion. Although there are always those who will.

The Story equivalent of objective truths are all of those Story Grid things…genres, conventions, obligatory scenes, value shifts, inciting incidents, progressive complications, crises, climaxes, resolutions, points of no return, hero’s journeys, etc.

I didn’t invent that stuff. I pulled it from years and years of research of story structure from the brilliant thinkers who came before me. Sorry if you’re not convinced about them. I hope you find peace living in your magical story land where all efforts are precious and beautiful and perfect.

And sorry for all of you who think that there is an audience for a book just because a writer put a lot of hard work into it… If the book does not abide millennia old story structure principles, it will not last. No chance.

Remember, as Steve so wisely wrote, “Nobody Wants to Read Your Shit.” No matter how hard you worked on it. No matter how much you hope that your art is sublime the way it is, if it doesn’t tap into the thousands of years of Story structure while at the same time adding its own innovations, it will not live a long life.

Could it become a bestseller? Sure, but you have a better shot at winning the lottery. Why not just play the lottery?

Great art is immortal.

If that’s not what you dream of creating…something alive after you’re dead…I don’t want to work with you.

The best editors identify and delineate all of a draft’s flaws by citing objective story truths. There’s really no debating when a writer doesn’t deliver a scene that is required for a particular genre.

Again, please spare me the amateur dilettante arguments. I don’t care about the book that broke the rule and was a bestseller. I guarantee you it will not be read or thought about by your children.

Citing OBJECTIVE TRUTH is the way an editor tells the writer WHAT IS WRONG WITH HIS STORY.

These criticisms are the things that a writer will first accept as truth. Editors providing this fundamental service to a writer are priceless. They’re not enough of them. We need more. A lot more.

Telling a writer what is wrong with his story is the editor’s craft. It’s an indispensable skill. It can be learned. Like shooting free throws or doing knee replacement surgeries or dovetailing.

Back to Steve’s post,

If Shawn’s notes made eight points, I found I could accept two.

Those first two points Steve is referring to are the “Objective Truths” about his draft that I laid out for him.

It’s where most editors sign off. And that is absolutely fine. The value delivered doing just that is worth years of a writer’s life, simply because they’ll learn not to make the same mistakes over and over again.

So what about the other six points that I put in my editorial letter Steve found difficult to accept?

These are the Subjective Truths.

That’s the secret ingredient that keeps a writer and editor in the same trench year after year.

Giving a writer his Subjective Truth about the writer’s work is the editor’s art. It’s why I show up every day. To do more of it, better than the last time I did it, to push the envelop a wee bit further out with each new project.

And it’s art just as hard to deliver as a writer’s. I’d argue it’s more difficult because of that thing Resistance knows…

An Editor is a midwife. The only one who truly knows her value is the birther.

July 5, 2017

Report from the Trenches, #1

I’m gonna take a break in this series on Villains and instead open up my skull and share what’s going on in my own work right now.

It ain’t pretty.

Joe and Willy, from two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Bill Mauldin

I’m offering this post in the hope that an account of my specific struggles at this moment will be helpful to other writers and artists who are dealing with the same mishegoss, i.e. craziness, or have in the past, or will in the future.

Here’s the story:

Eighteen months ago I had an idea for a new fiction piece. I did what I always do at such moments: I put it together in abbreviated (Foolscap) form—theme, concept, hero and villain, Act One/Act Two/Act Three, climax—and sent it to Shawn.

He loved it.

I plunged in.

Cut to fifteen months later. I sent the finished manuscript (Draft #10) to Shawn.

He hated it.

I’m overstating, but not by much.

Shawn sent me back a 15-page, single-spaced file titled “Edit letter to Steve.” That was April 28, about ten weeks ago.

Every writer who is reading this, I feel certain, has had this identical experience. Myself, I’ve been through it probably fifty times over the years, for novels, for screenplays, for everything.

Here was my emotional experience upon reading Shawn’s notes:

I went into shock.

It was a Kubler-Ross experience. Shawn’s notes started out positively. He told me the things he liked about the manuscript. I knew what was coming, though.

When I hit the “bad part,” my brain went into full vapor lock. It was like the scene in the pilot of Breaking Bad when the doctor tells Bryan Cranston he’s got inoperable lung cancer. The physician’s lips are moving but no sound is coming through.

Here’s the e-mail I sent back to Shawn:

Pard, I just read your notes and as usually happens, I’m kinda overwhelmed. As you suggest, I’ll have to re-read a bunch of times and chew this all over.

MAJOR, MAJOR THANKS for the effort and skill you put into that memo. Wow.

I’m gonna sit with this for a while.

Can you read between the lines of that note? That is major shell shock.

I put Shawn’s notes away and didn’t look at them for two weeks.

In some corner of my psyche I knew Shawn was right. I knew the manuscript was a trainwreck and I would have to rethink it from Square One and start again.

I couldn’t face that possibility.

The only response I could muster in the moment was to put Shawn’s notes aside and let my unconscious deal with them.

Meanwhile I put myself to work on other projects, including a bunch of Writing Wednesdays posts. But a part of me was thinking, How dare I write anything ‘instructional’ when, after fifty years of doing this stuff, I still can’t get it right myself?

There’s a name for that kind of thinking.

It’s called Resistance.

I knew it. I knew that this was a serious gut-check moment. I had screwed up. I had failed to do all the things I’d been preaching to others.

After two weeks I took Shawn’s notes out and sat down with them. I told myself, Read them through one time, looking only for stuff you can agree with.

I did.

If Shawn’s notes made eight points, I found I could accept two.

Okay.

That’s a start.

I wrote this to Shawn:

Pard, gimme another two weeks to convince myself that your ideas are really mine. Then I’ll get back to you and we can talk.

Three days later, I read Shawn’s notes again.

This time I found four things to agree with.

That was progress. For the first time I spied a glimmer of daylight.

Two days later I began thinking of one of Shawn’s ideas as if I had come up with it myself.

Yeah, it’s my idea. Let’s rock it!

(I knew of course that the idea was Shawn’s. But at last, forward motion was occurring. I had passed beyond the Denial Stage.)

I’ll continue this Report From the Trenches next week. I don’t want this post to run too long and get boring.

The two Big Takeaways from today:

First, how lucky any of us is if we have a friend or editor or fellow writer (or even a spouse) who has the talent and the guts to give us true, objective feedback.

I’d be absolutely lost without Shawn.

And second, what a thermonuclear dose of Resistance we experience when faced with the hard truth about something we’ve written that truly sucks.

Our response to this moment, I believe, is what separates the pros from the amateurs. An amateur at this juncture will fold. She’ll balk, she’ll become defensive, she’ll dig in her heels and refuse to alter her work. I can’t tell you how close I came to doing exactly that.

The pro somehow finds the strength to bite the bullet. The process is not photogenic. It’s a bloodbath.

For me, the struggle is far from over. I’ve got weeks and weeks to go before I’m out of the woods and, even then, I may have to repeat this regrouping yet again.

[NOTE TO READER: Shall I continue these “reports from the trenches?” I worry that this stuff is too personal, too specific. Is it boring? Write in, friends, and tell me to stop if this isn’t helpful.

I’ll listen.]

June 30, 2017

The Professor, The Artist, The Writer, And The Dots

Have you ever experienced a lightning strike when reading a book, listening to a song, or staring at a painting?

Have you ever experienced a lightning strike when reading a book, listening to a song, or staring at a painting?

That thing that’s been hanging in the background emerges with a clear path ahead of it. You know what to do—how to paint that portrait, how to sing that song, how to frame that book. It’s as if all the ideas in the universe came together at that moment to clear the way for one big idea—an idea that relied on you being in that exact place and time.

This line from F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon fueled a “What It Takes” article last year:

“I can always tell people are nice,” the stewardess said approvingly, “if they wrap their gum in paper before they put it in there.”

This week I’ve been going back and forth between Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood and Jeff Goin’s Real Artists Don’t Starve.

Toward the beginning of Norwegian Wood lives a spin on that old “you are what you eat” saying:

Toward the beginning of Norwegian Wood lives a spin on that old “you are what you eat” saying:

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

I typed it into my file of lines—those strands of words that double as defibrillators for my brain. When I stall, a read of those lines gets the noggin’ pumping again.

So it was with that line in my head that I started reading Real Artists Don’t Starve.

The back cover says the book debunks the myth of the starving artist.

While that might be what it is about, the book itself is an example of connecting the dots, which is what Greats do best.

The book starts with a story about Professor Rab Hatfield. Hatfield was in Florence researching Michelangelo. Next thing he knew . . . yada yada yada . . . Hatfield shattered what we thought we knew about the famed artist. Turns out he was a fat cat, full of dough. Hatfield tracked down 500 year old bank records that challenged the myth.

Jeff’s point in this story is that Michelangelo wasn’t broke—and artists today don’t have to be broke either. I agree. I hate the starving artist narrative. Everytime I meet art students, I beg them to take at least one course on contracts and basic accounting. This is the same advice you might give to someone buying a car or a house. You don’t have to be an expert, but you do need to know enough to identify when you’re getting screwed—or on the other hand, when a good deal is staring you in the face.

What got me thinking in the Michaelangelo story, though, wasn’t related to the artist, but to the professor instead.

The information was out there.

The professor wasn’t the first to dig around in the files.

And yet . . . That bit of magic occurred when he was traveling one track and then . . . BOOM! Lightning strikes and operates like a train switch. New track.

From Real Artists Don’t Starve:

“I was really looking for something else!” the professor yelled into the phone from his office in Italy, decades later. “Every time I run across something, it’s because I was looking for something else, which I consider real discovery. It’s when you don’t expect it that you really discover something.”

Instead of staying on track he flung open the door and on the other side made a discovery. Had he kept his blinders on, there’s a good chance Jeff wouldn’t be writing about him, nor would I.

But he did go off track and he did connect the dots.

Many of the articles and books and interviews Jeff cited are new to me. Thus, had I sat down to write this book it would have been completely different. He was a specific person in a specific time with specific background and specific experiences. The result? He connected the dots for the rest of us.

What does this mean for the rest of us, trying to write our own books?

We can’t predict the best time and place for the magic to take place, but . . .

We can open the door.

In order to connect the dots, Professor Hatfield had to open the door. When he started straying off track, which will happen with research, he kept going.

While reading the resource list at the back of Real Artists Don’t Starve, I imagined Jeff doing the same, going down the rabbit hole of research, without getting lost—with the ability to distinguish a door from a dead end.

This is what great artists do. But in order to connect the magnificent great big idea dots, they have to have boatloads of smaller idea dots.

Back to Haruki Murakami’s quote again:

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

If you limit your intake, you’ll limit your output.

The more ideas entering your noggin’ the more it’ll have to chew on—and the more likely it is that you’ll be a recipient of a bit of magic.

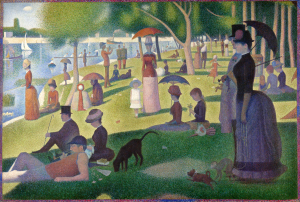

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat

Imagine Georges Seurat sitting in front of his canvas, one dot at a time until “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” emerged. Had he combined the wrong colors . . . Used fewer “dots” . . . Instead, he put the dots together and . . .

Lightning Strike.

Voila!

A masterpiece was born.

June 28, 2017

Every Villain is a Metaphor for Resistance

Darth Vader.

Compared to Resistance, this dude is a pussycat

The Gorgon.

Medusa.

They and every other villain in myth and literature (and real life) are metaphors for Resistance.

Resistance is the universal and ultimate villain.

Consider how this monster was described in The War of Art.

1. Resistance is Internal.

It is self-generated and self-perpetuated.

Resistance is Insidious.

Resistance has no conscience. [It] is always lying and always full of shit.

Resistance is Implacable.

It cannot be reasoned with. It is an engine of destruction … implacable, intractable, indefatigable. Reduce it to a single cell and that cell will continue to attack.

Resistance is Impersonal

It doesn’t know who you are and it doesn’t care. Resistance is a force of nature.

Resistance plays for keeps.

Resistance’s goal is not to wound or disable. It aims to kill. Its target is the epicenter of our being, our genius, our soul. When we fight Resistance, we are in a war to the death.

The reader or moviegoer doesn’t have to be aware of the concept of Resistance to feel its echoes in Freddy Krueger and Leatherface and the Zombie Apocalypse, not to mention our friends the Alien, the shark in Jaws, and the Terminator.

The human heart looks in Hannibal Lecter’s eyes and recognizes the ultimate nemesis within its own chambers.

Write a villain that is as evil as Resistance (and shares as many of its specific qualities as possible) and you will be more than halfway to penning something spectacular.