Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 61

April 12, 2017

You, a Lion

You were born for adversity. It’s in your DNA as much as it’s in the DNA of a shark or an eagle or a lion.

Our hero

You were made for hard times. The species of Homo sapiens has survived and prevailed not because we are faster or stronger than all the competing creatures. Every one of them is better equipped by nature with fangs and claws and wings and fur. Every one is better adapted to hunt, to kill, to survive drought and heat and cold.

Yeah, our race has a better brain. And yes, we figured out the advantages of hanging together into a hunting band. But that’s not what got us to the top of the food chain, and it’s not what undergirds you and me thirty-six months into a 1200-page epic when Con Ed cuts off our power in January in Bensonhurst.

The central tenet of the Professional Mindset is the willing embrace of adversity.

Most people spend their lives avoiding adversity. The pro sees things differently. She understands the inevitability of opposition, of tribulation, of Resistance.

She knows that the gold is always guarded by a dragon.

The pro accepts adversity the way she accepts gravity and the changing of the seasons.

Adversity, she understands, is not just part of life. It is life.

You are a lion.

You are an eagle.

Coded into your genes is that strand of orneriness and mulishness that refuses to quit, that keeps coming back for more. That’s your birthright, sent down to you from those wily hominids who hunted and trekked across the African savannah back when humankind was little more than an appetizer for the dominant predators.

We were hors d’oeuvres.

We were finger food.

How easy must it have been for a saber-tooth tiger to run down a three-foot-six, seventy-pound homunculus who had nothing to protect herself with except a stick and a stone?

Where are those saber-tooths now?

Are you a novelist? A screenwriter? Are you a long-form nonfiction writer, a blogger, a dancer, an actor, a painter, a filmmaker, a video game creator? Then give thanks to that runty, naked, slow little proto-human who bequeathed to us something more valuable that fangs or claws or cheetah-like speed.

She gave us guts.

Forget brains.

Forget adaptability

Forget tribal cohesion or language or the capacity to cooperate.

Our stubby little ancestor left us not just the ability to endure adversity, but the capacity to thrive under conditions of adversity.

The famous Ernest Shackleton newspaper ad for the Antarctic expedition of 1913 has been cited a million times, I know. Still it stirs our grubby Neanderthal hearts:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in event of success.

To the professional, the field is adversity.

Inside and out, she looks and sees opposition. She sees difficulty, hardship, tribulation. She sees Resistance.

She accepts it.

Her mindset is not, How do I avoid adversity? Her mindset is, What is my plan to deal with adversity and overcome it? What’s my objective? What are my resources? What’s my attitude?

The professional faced with tribulation takes a deep breath and offers a prayer of thanks to her hairy, near-sighted, bow-legged foremother of the savanna for the gift of grit and tenacity and fortitude.

She is an artist.

She is a lion.

April 7, 2017

Big Idea Nonfiction

This is the third post in my Story Gridding Nonfiction series. To read the first, click here. To read the second, click here.

In the last post, I broke down all of nonfiction into four large categories, the big kahuna genres.

A good guy to follow…Marcus Aurelius points the way

They are:

Academic

How-To

Narrative Nonfiction

and

Big Idea

What I love about the fourth category, Big Idea, is that it combines elements of the three other big categories. It’s a Genre-meld of sorts akin to fiction’s Thriller genre, which combines elements of Action, Horror and Crime into its narrative gumbo.

The War of Art is a perfect example of a Big Idea Nonfiction book.

As we all know, it combines the Academic (Jungian psychology) with How-To (the second part of the book “Turning Pro” prescribes a course of action) and Narrative Nonfiction (in this case Steve’s backstory as struggling amateur transforming into blue collar professional).

So how did Steve pull this neat trick off?

Let’s Story Grid an answer.

We know that the fiction Genres manage audience expectations and that the ways Genres do that is by having conventions and obligatory scenes.

Can the same be said for Nonfiction Genres too?

Definitely.

So what are the conventions and obligatory scenes of Big Idea Nonfiction?

Here’s what I think:

The first convention is obvious.

There must be an overarching Big Idea that is both a surprising and audacious assertion and an inevitable conclusion by the story’s end.

Does that phrase ring a bell? It should because it is the same thing required of a great fiction Story. Remember David Mamet’s quote from Bambi vs. Godzilla on what makes a Story work?

“They start with a simple premise and proceed logically, and inevitably, toward a conclusion both surprising and inevitable.”

A Big Idea Book needs this kind of premise and payoff too.

Let’s check to see if The War of Art delivers this convention.

Steve puts forth at the beginning of the book that there is an enemy within all of us intent on destroying our creative actions. (Creative dreams are a-okay with this enemy, but actually doing something to bring them to fruition is a no-no.)

He names this enemy Resistance.

The payoff of the book is that the only way to create something is to engage this enemy every single day of our lives. That is, we must wage a moment by moment war with the creature within in order to release our inner gifts. Resistance is a thing that keeps on coming no matter if we have a Billion dollar bank account, an Oscar on the shelf or a Nobel prize.

It’s a war to the death to release our inner genius.

Surprising and audacious idea? Yes. To name and define the enemy within was a huge innovation in the “creative process” pantheon. Creativity is not soft and warm and safe as we’ve been led to believe. It’s a freaking war!

An inevitable conclusion based on the premise? Yes. The only way to release your creativity is to get in the ring with Resistance and refuse to quit.

The second convention of the Big Idea Book is that the writer uses all three of the classic forms of argument/persuasion to make his case. Those three forms come from Aristotle.

They are:

Ethos

Logos

Pathos

They are delivered through the writer’s choice of narrative technique, i.e. how he or she chooses to address the reader. His or her point of view/voice.

More on these in the next post.

The third convention of the Big Idea Book is to tease the reader with narrative cliffhangers. That is, the writer makes judicious use of the novelist’s tools to create narrative drive…mystery, suspense and dramatic irony. Without narrative drive a Big Idea Book will fizzle and the reader will abandon it.

The way a Big Idea writer can keep the reader glued to the page is by regulating the amount of information he gives the reader. Not too much and not too little. Just enough.

This is an indispensable element of Narrative Nonfiction too.

The War of Art is built with a simple narrative engine fueled by three fundamental questions…

Why is it so hard to create?

How can I train myself to create?

Is creating really that important?

A must have obligatory scene/moment in a Big Idea book is what I call the “Big Reveal,” which is the moment in which the reader discovers that what he’s always believed about a particular phenomenon is spectacularly wrong.

This “Big Reveal” is akin to the global story climax in a novel.

Steve used his Big Reveal as the title for his book…The War of Art. So did Malcolm Gladwell…The Tipping Point. And then they both delivered impeccable arguments to support their audacious Big Ideas.

Other obligatory scenes deliver “evidence.” These are the case studies, data, etc. from reliable and respected sources to support the Big Idea. More on this too in the next post about ethos/logos/pathos.

These obligatory scenes are the fundamental element of Academic Nonfiction.

Also obligatory are prescriptive, how-to scenes/advice to apply the knowledge revealed from the Big Idea to everyday life.

This is the fundamental element of How-To Nonfiction.

Lastly, entertaining anecdotes have become obligatory in the Big Idea Book, what I like to think of as “cocktail conversation fodder.” These are little bits of Story that the reader can march out to enthrall strangers at social gatherings. These bits are sticky, easy to remember and spread to friend or acquaintance.

Why have I taken the time to put forth my ideas about conventions and obligatory scenes/moments for the Big Idea Nonfiction book?

There’s a very good chance that I’ve missed a few or perhaps given too much weight to one over the others.

That is, who’s to say that my interpretation is the be all and end all? I certainly wouldn’t.

But here’s the thing.

If you wish to improve as a writer, an editor, or a human being for that matter, you need to constantly challenge yourself with little puzzles. Why did that book sell so many copies? Why did that other book never hit a bestseller list but is the gold standard for its tribe? How many different kinds of my favorite Genre are there? What do I know that others find fascinating? And on and on.

You need to expose yourself to all sorts of phenomena and think about why it is what it is and where it fits into the universe. What is its substance and material?

What Marcus Aurelius called “causal nature.”

The way you do that is to make judgments.

You need to think deeply about the art you admire and ask yourself this simple question…

“If (insert the omnipotent power of your choice) were to descend from the heavens and demand that I create my masterpiece right this very moment or face a one way ticket to oblivion, how would I do that?”

The way I would do that is to think deeply about how the great works I admire work…and then apply the principles inherent in them to guide me.

We can learn a lot more from The War of Art and The Tipping Point than just the staggering Big Ideas they so brilliantly put forth.

With some analysis using storytelling structure as our methodology, we can learn how Pressfield and Gladwell put all of their book’s pieces together to form a seemingly effortless true story.

Next up is a deeper look at the ethos, logos, and pathos nonfiction trinity and how they are employed in the Big Idea Book.

April 5, 2017

Surviving in the Desert

A few years ago I wrote a book called Killing Rommel. Killing Rommel is a novel set during WWII in the North Africa campaign. Its heroes are the men of the Long Range Desert Group, a true historical British commando unit that fought behind the lines against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the German Afrika Korps.

Kiwis and Brits of the Long Range Desert Group

The first time I heard the name Long Range Desert Group, I fell in love with it. I said to myself, “I don’t know what this is, but I gotta write a book about it.”

“Long Range.” Way cooler that Short Range.

Even better: “Long Range Desert.” Somebody was going out into the Tall Sand a long, long way.

And “Long Range Desert Group?” It didn’t sound typically military to me. It sounded like a tech start-up.

The LRDG, it turned out, smacked more of a civilian outfit than an over-organized, rigorously-disciplined military team. The trucks they drove were Chevy “30-hundredweights,” bought from civvie dealerships in Cairo. Discipline was slack. Improvisation was the order of the day.

Why did I love this subject?

Because it reminded me of the writer’s life.

The men of the LRDG had a mission. Their charge was to leave civilization behind and advance alone into the unknown. Once out there, they could call on no one for aid or rescue. They were on their own, with nothing to assure their success except what they brought with them.

That’s you and me. That’s the writer’s life.

The desert is a metaphor for the creative sphere that you and I operate in. The desert is beautiful. It’s remote, it’s odd, it’s strange. Only a special few dare to enter.

The desert contains secrets. It’s mysterious; it seems barren but it’s actually teeming with life if you know where to look.

The “sand sea” of the Libyan desert

The desert is reality stripped to its essentials. It’s pure. It’s geometric. Its landscape of dunes and wadis (dry rivercourses) has been shaped by nothing but the elemental forces of wind, water, and time.

The desert is cruel. It will cook you, freeze you, drown you. Worse, the desert is indifferent. Its sand will drift over your corpse in minutes. It will forget you as if you never existed.

That’s our world, yours and mine. It’s the dimension we enter every day, seeking our Muse.

What about enemies?

The desert holds two—the external foe (in the case of the Long Range Desert Group, the enemy was the Afrika Korps) and the internal adversary, the men’s own fears and Resistance.

Think about it. Your truck breaks down five hundred miles from civilization. By noon, external temperature will hit 130 Fahrenheit. Can you keep your head? Can you improvise a fix for your cracked engine block? Can you stretch twenty gallons of fuel to carry you home?

That’s you and me at page 183 in our novel. That’s us in the middle at Act Two.

What I love too about the Long Range Desert Group (and why it fits into this series on the Professional Mindset) as that it was—and had to be, by the nature of its mission and the grounds over which it operated—self-contained.

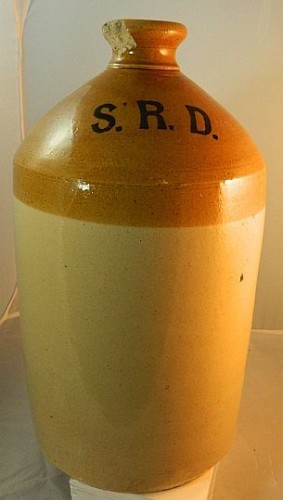

Into the beds of those Chevy trucks the men of the LRDG loaded fuel, water, rations, radio gear, weapons, ammunition, spare parts. Into nooks and crannies they wedged their bedding and clothing, their tea and tins of bully beef. Like sailors they brought rum, in porcelain demijohns jars labeled S.R.D. (for Service Reserve Depot) that they translated as “Seldom Reaches Destination.”

A ceramic or porcelain demijohn held one Imperial gallon (4.5 liters) of rum.

That’s you and me too. The essence of our artistic/entrepreneurial life is that it is and must be self-contained.

We and we alone must decide what we will work on, and how, for how long, under what conditions, with what ambitions and aspirations. We have to master the art of self-evaluation. Is our idea good? Good enough to give two years of our lives to?

When our vehicle founders in the Sand Sea, what resources can we call on within ourselves? The cavalry isn’t coming. It’s up to us and us alone.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Long Range Desert Group was the type of men it sought for its ranks. The LRDG never lacked for volunteers. Out of one application-round of 800 men, it selected twelve.

Most of the men in the Long Range Desert Group were Kiwis. New Zealanders. They were farmers and stockmen, mechanics and farm appraisers. Their age was roughly ten years older than regular line troops. Most were married and had children. No few owned and worked farms and ranches of considerable size.

They were mature men (alas, no women went into the desert in that era, though that almost certainly would be different today) whose primary emotional characteristics were resourcefulness, level-headedness, self-composure, patience, the ability to work in close quarters with others, the capacity to endure adversity and even to thrive on it, and, not least, the possession of a sense of humor.

In other words they weren’t blood-and-guts man-killers. (Okay, some were.) They were cool customers, possessed of grit and savvy, who could embark on a mission whose hazard was such that saner heads would call it absolutely nuts—and see that mission through, no matter what .

Isn’t it interesting that those are the same qualities you and I need, to survive in our own inner deserts?

March 31, 2017

Hemingway Did Not Non-Summit

A summit is the highest of the high. It is the top of a mountain. The apex. The peak. The zenith.

If it is a summit meeting, it is a meeting of individuals at the peak. Think Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin during WWII.

If you’ve been following this blog, you know my feelings about the trending use of the word summit to describe events, workshops, interviews, get-togethers, and a long list of other things that are not summits of either the mountain or meeting variety.

Another piece to add:

These non-summits are a form of procrastination.

When you’re at the base of an actual summit, don’t hold a meeting. Climb to the top instead.

One more piece:

These non-summits have the potential to steal your work’s soul—and your soul’s work.

Stick with me a bit here, for a short ramble.

In her Scientific American article “On writing, memory, and forgetting: Socrates and Hemingway take on Zeigarnik,” Maria Konnikova opened with the story of psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik.

In 1927, Gestalt psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed a funny thing: waiters in a Vienna restaurant could only remember orders that were in progress. As soon as the order was sent out and complete, they seemed to wipe it from memory.

Zeigarnik then did what any good psychologist would: she went back to the lab and designed a study. A group of adults and children was given anywhere between 18 and 22 tasks to perform (both physical ones, like making clay figures, and mental ones, like solving puzzles)—only, half of those tasks were interrupted so that they couldn’t be completed. At the end, the subjects remembered the interrupted tasks far better than the completed ones—over two times better, in fact.

Zeigarnik ascribed the finding to a state of tension, akin to a cliffhanger ending: your mind wants to know what comes next. It wants to finish. It wants to keep working – and it will keep working even if you tell it to stop. All through those other tasks, it will subconsciously be remembering the ones it never got to complete. Psychologist Arie Kruglanski calls this a Need for Closure, a desire of our minds to end states of uncertainty and resolve unfinished business.

I think this might be why the mornings are so magical for work. The mind just spent hours chewing over unfinished business. Yes, it brought up some family drama I wanted to avoid, but it did a ton of heavy lifting on unfinished work that is of importance. It made the connections between all the fragments clear, helped sew up the loose ends, fuse together the matching pieces. It made the struggle to understand—and view—the path ahead clearer. It’s why I try to wake before the kids and try to avoid talking, even of the e-mail chatter sort, in the early hours. There’s a magic there that’s gone by 9 AM, so I want to catch it within easy reach at 5 AM.

Maybe this is why counseling works, too. Once you talk it all through, you come closer to being able to let go, to find closure.

I just finished Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami and there’s a scene when one of the characters requests that a fellow traveler of the same world burn her manuscript. It isn’t for publication or reading. It is her life. She had to put it all down. Remember everything. Get it out. Once she added that final period, her body died and her soul—or whatever you want to call that “it” thing about her, that essence—moved to a different world.

Once she completed her story, she was able to move onto the next place.

But what if you talk through all of your work—all of your dreams—without actually doing them? You risk moving on, though that’s the last thing you really want.

Back to Konnikova’s article, this time with a quote from an interview Ernest Hemingway did with George Plimpton, for the Paris Review:

“… though there is one part of writing that is solid and you do it no harm by talking about it, the other is fragile, and if you talk about it, the structure cracks and you have nothing.”

Again, from Konnikova:

Hemingway’s words came from experience. When his wife lost a suitcase that contained all existing copies of his short stories, the work was, to his mind, gone for good. He had written himself out the first time around. He couldn’t recapture it—whatever it was—again. He even fictionalized the process in the short story, “The Strange Country”: the writer whose stories have been lost finds it impossible to remember. “It’s useless,” he tells his sympathetic landlady. “Writing [the stories] I had felt all the emotion I had to feel about those things and I had put it all in and all the knowledge of them that I could express and I had rewritten and rewritten until it was all in them and all gone out of me. Because I had worked on newspapers since I was very young, I could never remember anything once I had written it down; as each day you wiped your memory clear with writing as you might wipe a blackboard clear with a sponge or a wet rag.”

I have a friend who attended an event led by Tony Robbins recently. It wasn’t called a summit, but she left inspired. She didn’t talk through every bit of her life or her dreams. She listened and learned. I’m not opposed to these events, but the ones that continue to come into Steve are increasingly from individuals who are holding meetings at the base camp—who have talked about climbing to the summit for years, but have never given it a shot.

One more thing from Konnikova’s article is this quote from Justin Taylor:

“Don’t take notes. This is counterintuitive, but bear with me. You only get one shot at a first draft, and if you write yourself a note to look at later then that’s what your first draft was—a shorthand, cryptic, half-baked fragment.”

Non-summits shouldn’t be drafts, but that’s what they are—and for some, a draft is an idea closed. It isn’t refined. It isn’t as good as it can be, but it is closed—and not reopened.

One small rant:

If you are early in your career, you don’t warrant your own summit. You just don’t.

The 18 year old who wants to be a life coach needs to go experience life first. Do something. You have something important to say? Go walk the talk. Get out of the house and away from all the screens. Go LIVE and CREATE.

Age, of course, isn’t a determining factor, but one used in the above because I’ve run into more teenage life-coach wanna-be’s.

*With age, the exceptions are related to individuals such as Malala Yousafzai, an extraordinary woman, who became the youngest Nobel Prize laureate at age 17. I’ll listen to her with every ounce of myself because her life experiences, her daily walk, are more than just talk. She’s lived her beliefs. She fought/continues to fight when others have hidden.

The 18 year old who has read a ton of Nietzsche but is still living off his parents? Not so much.

Climb the mountain. Don’t stop at the base. Your words are your oxygen, and if you use them all, you risk running out of breath within view of your goal, but without what you need to attain it.

March 29, 2017

What’s Your Culture?

One of our earlier posts in this series on the Professional Mindset was called “You, Inc.” It observed that many Hollywood screenwriters (including me) find it useful to incorporate themselves.

Steve Jobs established the culture at Apple

These writers don’t perform their labors as themselves but as “loan-outs” from their one-man or one-woman corporations. Their contracts are “f/s/o”—for services of—themselves.

I’m a big fan of this way of operating. Not so much for the financial or legal benefits, which really aren’t particularly significant, but for the mindset this style of working promotes.

If you and I are a corporation, we’ve gotta get our act together.

Amateur hour is over for us.

We’re competing now (in our minds at least) against Google and Apple and Twentieth-Century Fox.

We’ve got to be as focused and as organized as they are. We need a vision for our enterprise. We need discipline, we need dedication, we need tenacity.

In other words we need a culture.

Apple has a culture. Steve Jobs inculcated it.

The New England Patriots have a culture. It came from Bill Bellichick and Robert Kraft and Tom Brady.

What’s your culture?

Twyla Tharp’s got one. We know it from her book, The Creative Habit. We know that she gets up at five-thirty in the morning, catches a cab outside her Manhattan home, and heads to the Pumping Iron Gym on East 91st Street, where she stretches and works out for two hours. After that she heads to her dance studio, where she works all day on whatever show or piece of choreography she has been inspired with for that season.

That’s Twyla Tharp’s culture.

I don’t know what Stephen King’s culture is, but I know he works every day including Christmas and his birthday.

A few years ago the L.A. Times interviewed a sample of movie writers, asking them about their work habits and routines. The one thing I remember from the article is that three of the writers said they worked in their cars—and one said he worked while the car was moving.

I applaud the guy.

He’s got a culture.

A culture does a number of things for you and me.

First, it establishes a level of effort.

How hard do we imagine Steve Jobs worked?

A culture establishes a standard of quality below which we within the culture will not let ourselves fall.

What level does Toni Morrison operate at?

A culture lays out standards of ethics.

What level of chicanery will Seth Godin tolerate?

But most of all a culture gives us a vision for the future.

When a new coach is hired for an athletic team or a new CEO comes on board at a company, his or her first and most primary objective is to establish a winning mindset.

She banishes laziness and tentativeness. She elevates the level of commitment. She gets her players to buy in to a vision whose object is to produce victory (or success), if not immediately then over time.

A culture establishes a style—a way of working that most expresses our natural bent and gives us the best chance to be who we are and to produce the stuff that is most uniquely our own. At IBM in the fifties that meant white shirts and black ties. At Facebook today it’s T-shirts and sneakers (at least I think it is; I’ve never been inside Facebook).

What’s Rihanna’s style?

What’s yours?

I have my own personal culture. Some people think it’s a little crazy. I do myself sometimes. But I’ve evolved it over the years (or maybe I should say it has evolved me). It works. It works for me.

The difference between an amateur and a professional is an amateur has an amateur culture and a professional has a professional culture.

What’s yours?

March 24, 2017

Genre and Nonfiction

This is the second in my Storygridding Nonfiction series. To read the first, click here.

Who’s responsible for the mess in the kitchen?

“The Story Grid is interesting and all for fiction,” many say to me, “but I’m a journalist and I deal with facts and interview transcripts, you know ‘the truth’ … so it’s not going to be helpful to me.”

Au contraire, mes frères et soeurs.

The Story Grid is a way to clarify your writing intentions, especially for nonfiction writers. Once you know what kind/s of story you want to write, it then provides prescriptive advice to best realize it.

A pile of research with loads of facts, interviews and ephemera does not a compelling nonfiction book make. But that pile does hold the clues necessary for you the writer to organize those facts and interviews into a compelling argument that puts forth a well-conceived judgment of what exactly the data means.

For example, when my oldest son and I come home from a walk and we find a trail of bread crumbs from the mudroom to the kitchen (fact number one), and we discover a jar of peanut butter on the counter (fact number two), with a butter knife with a glob of peanut butter and raspberry jam soiling one of my finest linen napkins (fact number three) and after interviewing my wife and daughter about their whereabouts the previous hour (they were working through a violin lesson in my daughter’s bedroom), the story that I concoct based upon that information is not difficult to construct.

Nor do I have any worries about third party criticism of my deductive faculties. I know a mess when I see it and I’m confident in my conclusions about who was responsible.

Here’s what I tell myself.

My youngest son was hungry.

He made himself a peanut butter and raspberry jam sandwich and did not clean up after himself.

I then judge that behavior to be maladaptive to my requirement of having a clean kitchen.

And when I discover the poor lad sitting on our most expensive couch in the game room eating the hypothetical sandwich that I’d constructed in my mind based upon the evidence, the story in my head is confirmed.

I don’t fear judging the evidence nor do I shy away from condemning the accused. At no point does third party criticism for my jumping to conclusions enter my mind. I collected the evidence and did the appropriate interviews. Then I wrote the story in my head about what had happened.

And as any ethical journalist would do, I then ask my youngest son to confirm or deny my story.

Even though he claims innocence, his arguments ring false to me as he’s literally sitting with the sandwich in his hands, so I run the story in my head as truthful and have him clean up the mess in the kitchen. Case closed.

If I had to categorize that peanut butter and jam investigation, is there a story genre I could drop it into?

Of course!

It’s a nonfiction crime story that turns on the global justice/injustice value. And I’m playing the journalist/master detective solving the “someone has messed up the kitchen” crime.

Or more broadly, it’s Narrative Nonfiction, which is the process whereby the writer analyzes her data, decides which one (or more) of the global fiction content genres fits the evidence, and then organizes her material to tell a compelling tale using fictional narrative structure.

She doesn’t make anything up. Instead she judges the facts/evidence/data and determines if it fits the bill as an element for a particular global story. And after much deliberation she settles on one or more genres to best represent the underlying meaning of the evidence.

Obviously, we all do this stuff without thinking. Storytelling is deeply ingrained in every single human being and we don’t actually subjectively collect data, analyze it etc. before jumping to conclusions.

Something happens…it triggers a quick reaction in our brain and then a familiar story runs in our heads to explain the phenomena. We either act immediately on that story…or we set it aside while we mull the evidence at a deeper level using some sort of methodology to guide us.

A methodology that can serve as a useful guide to sorting out nonfiction data is The Story Grid.

So Narrative Nonfiction is one of the big broad genres of Nonfiction. What are the others?

Remember that Genres are those things that tell the audience what to expect.

Here’s mine own personal break down of Nonfiction. I’ve cobbled my Nonfiction thinking in much the same way I did with my Five Leaf Genre Clover theory for fiction, reading and incorporating other theorists’ thoughts about nonfiction along the way. My goal was to have a “go-to” system to evaluate and make quick decisions when I was an acquisitions editor at the Big Five publishing houses. And these broad categories serve me well to this day.

I think there are four major forms of nonfiction. What I mean is that these are the big silos that divide the primary grains of nonfiction…the wheat, the rice, the corn, the oats.

So here are my big silos of nonfiction.

Academic:

These are essays/books that are written for and read by a very focused readership.

These groups of readers are clearly defined, but small in number. As Seth Godin would say, these are Tribal readers dedicated to very specific passions/professions.

The narrative form of the writing is far more about “presenting the findings” than it is about entertaining the reader. The assumption of the writer of academic work is that her readership is absolutely engrossed by the subject matter itself and so really just wants to get the skinny on what it is the writer discovered or what the writer’s particular argument is. These readers don’t need to be spoon-fed the previous data or history of the art. They just want to know the innovative stuff.

An example of Academic writing at a very high level would be Thomas S. Kuhn’s indispensable History of Science, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. The audience for the book is narrowly defined, aspiring historians of Science or someone trying to fulfill a science requirement at a liberal arts College.

And the prose, while certainly accomplished, uses a lot of words like “henceforth” and has less than captivating chapter titles like Anomaly and the Emergence of Scientific Discoveries. But if you are into this kind of stuff, it doesn’t really matter. The meat on the bone in that book is enough to feed the History of Science nerd for a lifetime. Can you tell it’s one of my favorites?

But because there is a limited market for these sorts of works, the price point is usually quite high. Think about what you paid for your Calculus textbook in College. But some of these books, like Kuhn’s, do break out of the Academic world and go on to reach a wide trade (everyday people) audience. And when they do, the price point falls to pull in that larger crowd.

Wouldn’t you know it? Kuhn’s book, while absolutely all about Science and the scientific method has applications in other worlds…

How-To:

These are generally prescriptive books “for the trade audience.” What that means is that these books are written for the general Joe who wants to learn the best way to plant his garden, without having to enroll at Penn State’s Agricultural school. Or a general Jane who wants to learn how to change the oil in her old Volkswagen Beetle without going to a mechanic’s trade school.

But nowadays, How-To titles are migrating more and more to online courses and/or eBooks offered by straightforward experts in the particular arenas. Laser focused How-to is a great way to build a business today. No need to get Putnam to publish your Knitting Guide just to access the marketplace. If you build your own crowd of followers, they’ll pay you directly for your work. Just as long as the content is exceptional and well laid out and explained, a How-to book is a license to print money.

Examples are the Idiot Guides… and one of my personal favorites Mel Bartholomew’s Square Foot Gardening books.

Narrative Non-Fiction:

This category has exploded in the past half century. If someone threatened to turn off my Wi-Fi if I didn’t hazard a guess about how this category evolved, I’d say that the movement that gave it its vigor was New Journalism.

Writers like Gay Talese, Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin, Nora Ephron, Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, Hunter Thompson, Gloria Steinem and Tom Wolfe sit on the Mount Rushmore of New Journalism. And of course the monster book that really set the whole thing over the top was Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.

What is Narrative Non-Fiction?

It’s completely Story based. That is, it uses the narrative techniques of fiction in order to contextualize reportage. Huh?

In other words, the writer/journalist collects the usual data involved in reporting a story. But instead of just presenting the traditional Who, What, Where, When and How? out of the old-school reporter’s toolbox, New Journalists focused on the Why? something happened.

And the way they did that was to judge the evidence from their reporting and then make a case for their subjective interpretation of the truth behind the event. They clearly answered the question “Why.”

But they didn’t just come right out with a thesis statement of their findings like an academic work. Something like “our culture is so obsessed by celebrity that we’ve artificially alienated ourselves.” Instead, they engaged the reader with their Storytelling skills and layered the theme/controlling idea inside their stories.

Gay Talese’s seminal piece in the April 1966 Esquire “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” is a pitch perfect example of New Journalism.

Narrative Nonfiction done well is the best of two worlds—data (science) and story (humanities).

I think it’s obvious to everyone today that there is no such thing as an “objective” journalist. There are no unimpeachable Columbia University Masters of Journalism grads out there. Every writer has a subjective point of view and hiding behind a byline no longer remains a credible cloak for our media saturated populace. We all know the POV of The New York Times versus TMZ. Writing for one or the other tells us a lot about the tenor of the words before we read a single one.

What Narrative Nonfiction allows is for that subjective point of view (the writer/journalist) to argue his case. But the journalist can’t just “make things up.” He has to present the “evidence,” the details of the reporting in support of his particular point of view. But more importantly, he can’t just make declarative statements like an academic.

He has to tell a Story…like a novelist or short story writer would.

Gay Talese did not write about what he thought of celebrity. He told the story of trying to interview a celebrity. Big difference. I don’t really care what Gay Talese, the person thinks about celebrity. Nor does anyone else.

But I was enthralled by “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold”. By the end of the piece/story, I understood exactly what it was Gay Talese was getting at. He used the truthful details of his experience in a way to convey a theme/controlling idea.

Here are some popular examples of Narrative Nonfiction: Seabiscuit, The Boys on the Boat, The Devil in the White City, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, The Lion’s Gate, What it Takes…

The Big Idea Book:

The Big Idea Book draws from all three of the nonfiction categories above and when one succeeds, it’s capable of satisfying readers of all three too. Academics appreciate the research cited to support the Big Idea. How-To readers take away actionable steps that they believe can better their lives. And Narrative Nonfiction readers are captivated by the storytelling.

This is why publishers love the Big Idea Book…it can become a blockbuster bestseller.

It is Academic in its rigor. There is a crystal clear argument being made in a Big Idea book that the author builds and supports in much the same manner that an academic writer/researcher would. That is, he is making a case for demystifying a particular natural phenomenon and will support his conclusions with the applicable data etc.

It is prescriptive for the layman like a How-To book. The writer of the Big Idea book writes for the non-expert, not the specialist. He also contends that there are real world applications of his Big Idea that can change the lives of his readers. So the implied promise is that after you’ve read the Big Idea book, you will have the tools to apply the knowledge imparted in much the same was as you would be able to apply the principles of square foot gardening.

With varying degrees of success, it uses Narrative Nonfiction storytelling to impart a deeper theme/controlling idea into the work than just “how to use this knowledge and get a great tomato harvest.”

Examples of Big Idea Books are Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point, Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message, Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock, James Gleick’s Chaos, Thomas L. Friedman’s The World is Flat, Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s The Black Swan.

But what about Biography/Autobiography; History; Science; Business? Etc.? Aren’t those nonfiction genres?

Yes, of course. But I think all of those additional and familiar genres can be categorized into one of the four principle nonfiction genres I’ve discussed above.

You can have the Academic Autobiography or the How-To Science book or the Narrative Nonfiction Business book or the Big Idea History book.

The big broad nonfiction categories are useful because they give the writer an inherent structure and a specific audience to consider before they write 100,000 words with little appeal.

So for all of you nonfiction writers out there, think about which of these big four categories your work would best fit. And then start reading the masterworks for that particular global category.

March 22, 2017

Working on Two Tracks

When we finish any work of art or commerce and expose it to judgment in the real world, three things can happen:

Everybody loves it.

Everybody hates it.

Nobody notices that it even exists.

The value of Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” went from zero in 1889 to $39.9 million in 1987, the equivalent of $74M today.

[Continuing our exploration of the Professional Mindset, let me repurpose this post that first ran about four years ago.]

All three present you and me as writers and artists with major emotional challenges, and all three drive deep into the most profound questions of life and work.

It will not surprise you, I suspect, if I say that all three responses are impostors. None of them is real, and none should be taken to heart by a writer or artist working from the Professional Mindset.

When we labor in any field that combines art and commerce, we’re working on two tracks.

Track One, the Muse Track, represents our work in its most authentic, true-to-itself and true-to-our-own-heart expression.

Track Two, the Commercial Track, represents the response our work gets in the marketplace. In other words, points 1-2-3 above.

Track Two counts for putting bread on the table and getting our kids through college.

Track One counts for our artistic soul.

The problem with Track Two is it also represents the siren song of riches and fame, or at least applause and recognition in the real world.

Two weeks ago my friend Paul finished writing a TV pilot. It was the first time he had completed a project from FADE IN to THE END. He turned it in to a friend who is a serious producer and who was anxious to see it. Almost immediately Paul’s spirits went over a cliff.

He became depressed, anxious, irritable. He couldn’t sleep. He stopped working. He was waiting to hear his producer friend’s response.

In other words, Paul let himself get sucked over onto Track Number Two, the Commercial Track.

Hollywood (or any big-buzz field like music, publishing, games, software) is a Rorschach test for the soul.

Can we keep our focus where it should be? Can we find our real self and stand up for it? The dream of success/glamour/megabucks is like dark matter. It exerts a gravitational pull that’s so strong it can haul even the best us down into a black hole.

What’s the antidote?

The antidote is remaining grounded on Track Number One. There’s nothing wrong with success. I hold no beef with cashing a check or getting a parking place with your name on it. But don’t confuse Track #1 with Track #2.

While Paul was pacing his living room wondering if he could really kill himself by leaping out a second-story window, the real truth of his situation was this:

He had completed his first serious full-length piece of work.

He had shipped.

He had delivered.

His creative momentum was high.

The Muse was with him.

On Track #1, Paul was rolling!

My advice to Paul (which he did not heed, by the way) was to start another project immediately. In fact Paul was already working on Project #2. But he had stopped.

Why is it so important to keep working?

Because when we finish a project and wait around breathlessly to learn the world’s response to it, we have planted our butts squarely on Track #2. Track #2 means evaluating our work and defining our artistic selves by the opinion of others. (What Shawn calls 3PV, Third Party Validation.)

Nothing good ever came from 3PV. Even success can be bad, viewed through the prism of 3PV. How many people have won Oscars in one year, only to vanish into rehab the next? And failure? Ask Van Gogh how that worked out for him.

And yet: how was Vincent doing on Track #1? He was red-hot. True, a century ahead of his time, but still smokin’ hot.

The ideal position for an artist of authenticity is when Track #1 and Track #2 coincide. When he is working his real stuff—and that stuff finds a welcome in the wider world.

When an artist’s voice is true enough to his own heart and authentic enough to his own vision, Track #1 pulls Track #2 over to it. Bruce Springsteen. Bob Dylan. Hunter S. Thompson.

But we lose our way when we overvalue Track #2 at the expense of Track #1. “Sunflowers” was just as great in 1889, when Van Gogh couldn’t give it away, as it was in 1987 when it sold for $39.9 million.

Whatever Track #2 fate awaits Paul’s pilot, he knocked it out of the park on Track #1.

March 17, 2017

The Bar, the Blonde, and You

There’s a scene in the movie A Beautiful Mind, when the John Nash character explains the best way for he and his colleagues to get laid.

A blonde walks into the bar with a group of brunette friends. Nash’s colleagues start ogling her and making stupid comments.

HANSEN

Have you remembered nothing?

Recall the lessons of Adam Smith,

father of modern economics.

ALL

In competition, individual ambition

serves the common good.

AINSLEY

Every man for himself gentleman.

BENDER

Those who strike out

are stuck with her friends.

Nash stares at the blonde and Hollywood jumps in with voiceovers and special effects as Nash makes a breakthrough and starts monologuing.

NASH

Adam Smith needs revision.

If we all go for the blonde . . .

We block each other.

Not a single one of us is going to get her.

So then we go for her friends,

but they will all give us the cold

shoulder, because nobody likes to be

second choice.

What if none of us go for the blonde?

We don’t get in each other’s way

and we don’t insult the other girls.

That’s the only way we win. That’s

the only way we all get laid.

Adam Smith said the best result

comes from everyone in the group

doing what’s best for himself.

Incomplete . . . Incomplete . . .

The best result will come from

everyone in the group doing what’s

best for himself and the group.

However, this only applies to Nash’s colleagues. There are four of them and four brunettes. If their goal is to get laid they can’t help other men in the bar, because they’d lower the odds, with a greater man to woman ratio (all off this living under the assumption that the women even give a crap about men whose maturity levels are as low as their IQ’s are high).

We see this outside the bar, too. There are certain circles in which I often see the same authors endorse each other. By supporting each other’s work, the idea is that they help grow the success of each individual and the group.

This true?

Yes and no.

This can help grow an audience if that’s the goal. If the goal is selling a book or anything else that requires monetary transaction, then it isn’t as simple.

Let’s go back to Nash’s bar.

Instead of pulling apart the women, let’s look at the men.

Maybe one of the men is egotistical, another is lazy, another a slob, and yet another a bully—and all are disrespectful.

The four men make comments that get other men in the bar laughing and joking.

Now our four guys helped each other out, and in doing so helped garner a larger following of the group. The other guys at the bar love them and can’t wait for them to come back. But the women… They’ve moved on to more mature pastures.

So have our guys really succeeded?

No. It’s a false positive.

They think they’ve found success, but it isn’t really success. It becomes what they accept instead of what they need. They can hang with the same like-minded group all day, but what they need is to expand. Unfortunately for them, that audience isn’t interested in buying their B.S. They’re investing in short-term followers instead of long-term buyers.

Now let’s look at all the extras in the bar—and let’s assume they are viewing the movie example, when the guys get the girls.

If they’re paying attention, they can see what the main group has going on, and they want in on it. In their eyes, if they are in with the in crowd, they’ll “go where the in crowd goes” and “know what the in crowd knows.”

But . . . Can (and/or should) the group hold the extra weight? If the group is 20 instead of four men, and the number of women hits 20 as well, the problem then becomes time.

Each member of the group now has 19 instead of three others to help.

Let’s get out of the bar and back to the office.

If you’re an author, helping three people as needed is sometimes doable. Guaranteeing help to 19 is not. What do you do? You start saying no because you’re an author first and if you are helping 19 people every time they call, you aren’t doing your work, which is the one thing you have to do above all else. You also consider your circles because even though you can’t help all 19 all of the time, working with a few at a time might be doable. You start thinking in Venn Diagrams instead, because working with others is a good move and if all those circles are moving, different people will circulate through that sweet overlap.

If you’re one of the extras wanting to get into the group, you learn about the group first. You do your own work and get yourself to their level before you try to stick your foot in their door. You respect their time and you don’t behave poorly if they say no to you. You keep doing your work. You keep improving. You develop your own network.

The Nash-through-the-lens-of-Hollywood theory stands on solid ground. You have to take care of yourself first, but there are great opportunities available when you collaborate with others. Just make sure to avoid the false positive barflies. They’re good for laughs, but you need more than laughs.

March 15, 2017

427 Minus 1 = Zero

My first agent was a gentleman named Barthold Fles. He was seventy years old. When I fictionalized him in The Knowledge, I made him ninety-six. But he was really seventy.

427 is everything

I was twenty-nine at the time, so Bart had me by forty-one years. He was Swiss. He had represented Bertolt Brecht and even Carl Jung. He had seen and done everything.

One day Bart said to me, “How much is 427 minus one?”

I gave the obvious answer: 426.

“No,” said Bart. “It’s zero.”

He was speaking about pages in a novel.

If the full book is 427 and you’ve written 426, you haven’t got 426/427ths.

You’ve got nothing.

The work isn’t ready to be shipped till it’s 427.

I’m working on a new piece of fiction right now and I’m smack up against the finish line. It’s the eighth draft actually, but that’s the big one on this project. When I get this one done, I can say I’m over the hump.

Resistance, of course, is monumental.

So I’m thinking about Bart.

I quit 99.9% of the way through the first novel I tried to write, when I was twenty-four. Everything in my life imploded after that. It took me years to recover.

Like I said, I’m thinking about Bart.

Resistance ratchets itself to fever pitch as we approach the finish of any project. Only one response is possible. We have to assume the full Professional Mindset. Dig deep. Whatever it takes. We have to summon our resources of will and determination and push through.

No matter what, we MUST finish.

When I was interviewing Israeli fighter pilots for The Lion’s Gate, they told me of a concept they called “operational finality.”

The phrase in Hebrew is Dvekut BaMesima.

Mesima is “mission.”

Dvekut means “glued to.”

You and I may not be diving into a swarm of surface-to-air missiles or a barrage of anti-aircraft fire. But we still have to finish page 427. We have to put our bombs on target.

If you’re having trouble crossing that finish line, here are two pieces of good news:

One, you’re not alone. Everybody faces massive Resistance toward the end. It’s the nature of the beast. Like “hitting the wall” in a marathon, that moment of horror always rears its ugly head.

Two, if you can beat that monster one time (I can attest to this absolutely), it will never have the same power over you.

It’ll have power, yeah. But not at the same level.

Beat it once and you can beat it after that every time.

426 = zero.

427 is everything.

March 10, 2017

Nonfiction Stories

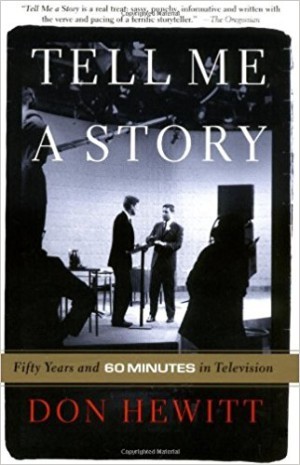

The late Don Hewitt was a master nonfiction story editor.

My next series of posts will concern the relationship between storytelling and nonfiction. In order to boil down my nonfiction editorial philosophy into a digestible 10,000 word-ish series for the www.sp.com crowd, I’ll be adapting voluminous material that I’ve previously released at www.storygrid.com

Bottom line is that you die-hard fans may discover material that I’ve written and published before. My intention is not to pass off old writing as original and new, rather to reuse sturdy prose that I stand by in my efforts to streamline my nonfiction editorial philosophy. So let’s get started.

The title of this post is an oxymoron right?

Nonfiction is supposed to be factual and “real,” while Stories are made up of flights of fancy, decidedly unreal. That’s what I was told in the classroom when I was just a wee boy and even later on in college.

It wasn’t until I was in my 30s, with years in book publishing’s trenches on my curriculum vitae, that I realized that those lessons were absolutely ridiculous.

Anyone who reads for a living soon learns that slogging through a purely factual work of nonfiction is an excruciatingly painful experience. The best cure for insomnia.

That’s because nonfiction without any contextual narrative is simply data.

Data is great and everything, but without someone analyzing it, judging it, and then explaining what she or he believes it means with a formulated and conclusive overarching controlling idea conveyed inside a story, it’s just a bunch of numbers or boringly objective description.

It’s important to note that I’ve worked on as many nonfiction titles in my career as I’ve worked on fiction…hundreds of books in all sorts of arenas.

Business, Instructional How-To, Investigative Journalism, Inspiration, Paranormal Memoir, Autobiography, History, Biography, True Crime, Academic, Military, Celebrity Memoir, Humor…just about every single nonfiction category you can think of…I’ve edited.

Why?

Beyond the fact that I was interested in each and every title I acquired, I used nonfiction to counterbalance the bets I was placing on the fiction I edited.

You see book editors are like heads of hedge funds. Without the big money.

You spread your bets across a slew of categories in order to secure a stable return on investment for your employer…so that you earn your salary and benefits while the corporation gets a multiple return on its investment in you.

When you’re young and buying a lot of penny stocks, you learn the trade. The early days for young editors back in the day were about getting to be in charge of “list building programs.” These programs allowed the publisher’s young Turks to acquire and publish up and coming writers with little financial exposure for the company. These are the programs that grew writers like Michael Connelly, Janet Evanovich, Robert Crais, and Mary Higgins Clark etc. into blockbuster bestselling writers.

As you gain more and more experience as an editor though, your days spending small money cease. You then end up limited to buying just blue chip stocks (luring a big name writer away from a rival for a lot of guaranteed money) and big potential IPOs (big idea projects from agents written by first time writers that seem to have huge upside). Successfully transitioning from publishing 30 to 50 books a year (no editor does that anymore unless they’re working for an independent eBook outfit) to 8 to 12 “big books” required the attainment of some editorial craft. Not that anyone offered lessons in editing. It was a self-taught, don’t let anyone else know your “system,” kind of craft.

So simply as a matter of survival, book editors (especially the senior, executive, and higher management ranking ones) become “generalists.” That means that their interests are wide and their expertise adaptable. They have a system that can fix a self-help book as well as a biography of Winston Churchill.

Knowing how to fix a nonfiction book as well as knowing how to massage a novel is a very marketable skill. And yes there are still at least one or two of those kinds of editors at each of the major publishing imprints. They’re the sanest people in the asylums. I know who they are because I grew up in the business with them or witnessed from afar when it was obvious they made something marginal work in a way no one expected.

A fiction editor who does not buy nonfiction today, though, is a rarity.

These last of the Mohicans are either at a relatively safe place in the career having resigned themselves to being satisfied with a solid if not extravagant salary and a nice office (nothing wrong with that if you get to work with writers you love on books you adore) or they are one of the up and coming younglings who just doesn’t know what’s good for them. Yet.

But, there are plenty of Nonfiction-Only Editors.

Why?

Because fiction is impossible to predict…why take on the agita of killing yourself to bring a novel to its finest possible expression without having any idea if anyone will read it? It’s just not rational.

Nonfiction, though, is much easier to assess in terms of its potential market. We can find the people who love fly fishing.

There are a gazillion diet books published every year…and it’s guaranteed that one of them will become the next new thing that sells a million copies and gives birth to a franchise. Many editors acquire their own diet book and throw it into the annual publishing lottery. As long as they don’t go crazy overpaying for it and edit it with some flair, their book will have as good a chance as anyone else’s to make #1 at Amazon.com on January 1. And certainly they won’t get blamed if it doesn’t work.

Okay so that’s the global science of being a “generalist” editor. You hedge your list with fiction and nonfiction to the best of your ability.

What about the art?

What about craft?

What about some good old fashioned, earnest, doing it for the love of books motivation?

What about that “system” editors use to pick their projects and edit them to the best possible effect?

That’s what’s next. How using storytelling techniques can make nonfiction as compelling as a Stephen King novel…